Abstract

This article analyses the ways in which the memory of transnational traumatic events of war and conflict of the past have been represented at Wellington's waterfront and whether the site, with its multitude of memorial plaques, can be read as a lieu de mémoire. The study focuses on three commemorative plaques: the memorial plaque to those New Zealanders who took part in the Spanish Civil War (2011); the commemorative plaque to the Polish children of Pahīatua (2004); and the memorial plaque commemorating the arrival of the United States Marine Corps to New Zealand (1951/2000). It, first, examines the memory entrepreneurs behind the commemoration of the events the plaques depict and analyse whether these agents engaged in bottom-up or top-down mnemonic practices and activities (or a mixture of these). Second, it analyses the significance of these memorials in the collective memory of contemporary Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Introduction

The commemoration of traumatic events of the twentieth century in Western society, often referred to as ‘memory boom,’ gained significant momentum from the second half of that century. The impact of historical events, and therefore also cultural practices of commemoration, increasingly goes beyond national borders and transforms the ways in which memories of conflicts, diaspora and historical violence are represented in a transnational memory-scape. More recently, heated discussions about memorials to a country's colonial past have erupted in regions with a history of colonial rule in the wake of the 2017 Charlottesville riots. These have also gathered momentum in Aotearoa/New Zealand. A statue of colonial governor Sir George Grey was splattered with red paint in June 2020, ‘evidently representing the blood of his victims, and the words ‘stop’ and ‘racist’ painted on his figure,’ and a memorial to Captain Hamilton was removed from the city named after him, following a call for its removal by a local Māori kaumātua (elder) (Kidman and O’Malley, Citation2022: 7–8). In late 2023, following a petition by former Māori Party co-leader Dame Tariana Turia, it was decided to remove the oldest New Zealand colonial war memorial – dating from 1865 – due to ‘on-going racist stereotyping;’ Turia posed the question why these stereotypes were still allowed to ‘be a representation of us [Māori] as a community’ (Ellis, Citation2023).Footnote1 The ongoing debates about collective memory often centre on the ways in which the representation of a community – whether through public monuments, historical narratives, or cultural symbols – shapes and influences the understanding of experiences and identities. These discussions about collective memory offer an opportunity for critical reflection on whose version of the past is remembered and whose memories are forgotten. Moreover, looking at the actors behind and the reasons for commemorative initiatives raise complex issues about the ways in which the legacies of the past impact the present. These debates demonstrate that the significance of historical events and historical figures to be commemorated is in a constant state of flux that can either lead to the contestation of memory, or conversely, to indifference, resulting in the ‘invisibility’ of monuments, memorials, and statues.

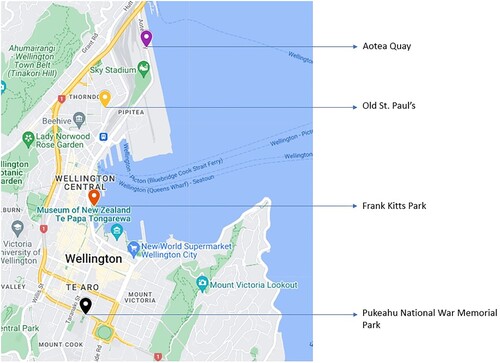

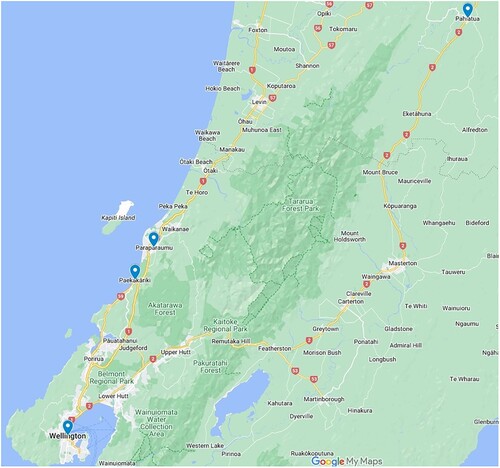

This study focuses on the ways in which twentieth-century events with transnational impact, such as the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) with its involvement of the International Brigades and events of the Second World War (1939–1945) are commemorated in and related to Aotearoa/New Zealand. The field of transnational memory provides an opportunity to investigate the ways in which historical events transcend geographical boundaries. By analysing the interrelation of memories across antipodal regions of the world, the study advances a nuanced insight into the different ways in which shared historical events affect the collective memory of diverse communities. The case vignettes chosen for this discussion consist of three commemorative plaques located at Frank Kitts Park on the waterfront in New Zealand's capital city, Wellington (see Map 1). The development of Wellington's waterfront for recreational activity, with an emphasis on historical and contemporary culture, was a major project of the 1990s (Wellington Waterfront Framework, Citation2001: 7–11). The waterfront became the city's sole substantial walkable public space, making it an ideal location for memorials to capture public attention.

Map 1. Map of the waterfront in Wellington, New Zealand. Google Inc, 2023. Waterfront in Wellington. Google My Maps. https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=yo82rhZA3nT_-59EtbymfQXbhBjHFnY&hl=en&ll=-41.284131241617864%2C174.78195965&z=14Screenshot by A. Hepworth.

The three vignettes discussed in this study consist of the memorial plaque to those New Zealanders who took part in the Spanish Civil War (2011); the plaque commemorating the arrival of the United States Marine Corps to New Zealand (1955/2000) and the commemorative plaque to the Polish children of Pahīatua (2004). The period from 2014 to 2018 marked the centenary of the First World War. The dedication of the memorial plaques in the first decade of the twenty-first century coincided with greatly increased public interest in Anzac Day commemorations in Aotearoa/New Zealand, focused both on the First and Second World War.Footnote2 Indeed, the centenary led to a heightened focus on commemorative activities globally. Despite the proximity of the plaques to each other on a designated section of wall reserved for commemorations, the cases of these three memorials exhibit crucial distinctions from one another. The article discusses the memorials in chronological order of the events to be commemorated, not in order of the dedication of the plaques. It, first, examines the ‘memory entrepreneurs’ behind the commemoration of the events the plaques depict.Footnote3 The study then analyses whether these agents engaged in bottom-up or top-down mnemonic practices and activities (or a mixture of these) to determine the power dynamics involved. Second, it investigates whether the commemoration of events in New Zealand that had their roots in historical and political developments in Europe represents what Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider call a ‘global’ or ‘cosmopolitan memory,’ that is, the mutual interaction between global and local memories (Citation2006: 131) and analyses the significance of these memorials in the collective memory of contemporary Aotearoa/New Zealand.Footnote4

Methodology: collective memory and lieux de mémoire

The article draws on the concept of lieux de mémoire, or sites of memory, developed by Pierre Nora, to analyse the memorials discussed in this study. Originally used by Nora to examine the construction of the French past, the concept has since been adopted by scholars world-wide. Nora argues that lieux de mémoire, sites where ‘memory crystallizes and secretes itself,’ are necessary ‘because there are no longer milieux de mémoire, real environments of memory,’ and because memory no longer comes about by natural means (Citation1989: 7, 12). For sites of memory to exist, he contends, ‘there must be a will to remember,’ and he considers the purpose of them ‘to stop time, to block the work of forgetting’ (Citation1989: 19). In this context, the article examines Wellington's waterfront as a memory-scape, that is, the spatial representation of collective memory by different groups.

Maurice Halbwachs’ concept of collective memory, defined as memory that is created and conveyed by social groups, further informs this article. Halbwachs emphasizes that memory functions within a collective context and is constructed with narratives and traditions that are created to give its members a sense of community (Citation1992: 79–102). Hence different social groups will have distinct collective memories, as will be discussed in the context of the different case vignettes throughout the article. The study further mobilizes two sub-categories of collective memory: cultural and communicative memory. Communicative memory, according to Egyptologist and memory studies scholar Jan Assmann, is an ‘everyday’ memory that is situated in the present and is ‘based exclusively on everyday communications’ (Citation1995: 126). Its primary characteristic is its ‘limited temporal horizon,’ which does not stretch beyond three or four generations. Communicative memory ‘offers no fixed point which would bind it to the ever expanding past in the passing of time;’ such stability can solely be attained ‘through a cultural formation and therefore lies outside of informal everyday memory’ (Assmann, Citation1995: 127). Cultural memory, on the other hand, includes the archaeological and written heritage of humankind; it is anchored to fixed points in the past by rites, monuments, texts, and commemorations. In the context of Aotearoa/New Zealand, also Māori oral tradition conveying tribal knowledge and history ‘by narrative, by song (waiata), by proverb (whakatauki), and by genealogy (whakapapa)’ (Binney, Citation1987: 16) constitutes cultural memory.Footnote5 Cultural memory transforms history into founding stories which are narrated to inform the identity of a group (2007: 50–52). Moreover, cultural memory is a means to reconstruct the past in the present and is hence adapted to present-day situations.

The article further mobilizes the concept of ‘institutional’ (Lebow Citation2006), or ‘political’ memory to analyse top-down approaches in shaping collective memory. ‘Political memory’ is a top-down memory created by institutions such as states and nations in the service of desired identity construction. Political memory influences society from above, as opposed to communicative memory, which grows from below (Assmann, Citation2006: 35–37). Lastly, following Michael Rothberg, the article considers memory as multidirectional, ‘as subject to ongoing negotiation, cross-referencing, and borrowing; as productive and not privative’ (Citation2009: 3) and suggests that the public sphere in which collective memories are articulated, such as Wellington's waterfront, is a discursive, non-competitive space. Namely, a space in which different narratives and memories can coexist, be communicated, and interact without being marked by intense competition or a zero-sum dynamic.

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the International Brigades

The first case vignette to be discussed is the commemorative plaque to all New Zealanders who fought in the Spanish Civil War. Hence a brief overview of the historical context of the conflict is essential. The military uprising in Spain in July 1936 led to a three-year civil war fought between the fascist Nationalists and the democratic Republicans. Both sides of the conflict had international allies: while Britain and France adhered to the principles of non-intervention, the Nationalists were aided by the fascist governments of Italy and Germany; New Zealand did not officially participate in the war.Footnote6 Republicans were assisted by the Soviet Union, as well as by the International Brigades, who were recruited and directed by the Comintern (Communist International). The Brigades were made up of volunteers from some fifty countries, among these also about twenty New Zealanders of whom many were trade unionists or came from other left-wing or humanitarian groups (Derby, Citation2009: 270–271). In late 1938, the International Brigades were formally withdrawn from Spain as part of an attempt by the Republican Prime Minister Juan Negrín to ‘shame’ liberal democracies into supporting the Republic, which, however, did not eventuate (Tremlett, Citation2021: 502). The Civil War ended in April 1939 upon the unconditional surrender of the Republican army. The total deaths from all causes on both sides are estimated to be around 500,000 (Preston, Citation2012: xi). Of the estimated 35,000 volunteers who fought in the International Brigades, a fifth died, at least six of whom were New Zealanders (Tremlett, Citation2021: 7; New Zealanders in the Spanish Civil War, Citation2012).

Contested memory in Spain

In Spain, more than forty-five years after the end of the Franco dictatorship (1939–1975), public debates about what in Spain is referred to as ‘historical memory,’ that is, the recuperation of the past and how to deal with the legacies of the Spanish Civil, the Franco regime and the transition to democracy, are still ongoing and the memory of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) is still a divisive topic. Only from the late 1990s onwards did the historical memory movement – an activist grassroots movement with the aim of recovering the previously silenced memories of Republican victims, and, from 2000, on the recovery of remains of the estimated 112,000 disappeared from unmarked mass graves throughout Spain – begin to gain traction.Footnote7 Consequently, in 2007 the controversial Law of Historical Memory (LHM) was passed to deal with the legacy of the Spanish Civil War and the Franco regime. Significantly, the law linked the struggle for justice for the victims of Francoism with the need to accord justice to the veterans of the International Brigades, which included offering Spanish citizenship to surviving members (Marco and Anderson, Citation2016: 407). In October 2022, an extension to the LHM, the Democratic Memory Law, came into effect, which extends Spanish citizenship also to descendants of International Brigadiers (El senado aprueba, Citation2022). Granting Spanish citizenship to the volunteers and their descendants – something Negrín had promised in 1938 but was unable to accomplish – is of significant symbolic value. Some of the Brigadiers, such as the Belgian, Dutch and Polish volunteers, had lost their citizenship in their home countries due to serving in a foreign army, others experienced a range of repercussions upon their return (Różycki, Citation2015: 149–150).

Likewise in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the Labour government did not support those who fought in the Spanish Civil War. The Catholic Church had recognized Franco's Nationalist regime as early as 1937 (Catholicism, the military and the ideological Falangist-fascist base formed the three pillars of the Nationalists), and the government did not want to alienate its Catholic Labour voters. However, the New Zealand Spanish Medical Aid Committee (SMAC), the Communist Party, and trade unions had raised enough money through public meetings, radio appeals and film screenings to send three nurses (René Shadbolt, Isobel Dodds and Millicent Sharples) to Spain, and to fund a field laundry truck, medical supplies, and an ambulance to help the Republican cause (Skudder, Citation1986: 466). This left-wing grassroots organization also organized the – only – memorial service for all New Zealanders ‘who died fighting in Spain’ in May 1939 in Auckland (Spanish Civil War Memorial Poster, Citation2013). Cultural studies scholar Jean Baudrillard points out that violent deaths become the ‘business of the group, demanding a collective and symbolic response’ (Citation1993: 165); hence the memorial service constitutes this symbolic response. The public mourning represented an immaterial, grassroots-initiated lieu de mémoire that contributed to the constitution of a left-wing community in support of the Spanish Republicans in New Zealand. The commemoration, in conjunction with memory work by returned Civil War veterans and those who had worked with medical units in Spain, ‘contributed to pro-Republican propaganda in New Zealand’ and had a significant impact on the public perception and remembrance of the Spanish Civil War (Skudder, Citation1986: 466). Returned New Zealand International Brigaders Tom Spiller, Bert Bryan and Dr Douglas Waddell Jolly – who had served as a surgeon with the International Brigade medical service – embarked on a nationwide speaking tour in 1938 to bring attention to the situation of Republican refugees and International Brigades prisoners (Skudder, Citation1986: 235; Derby, Citation2022).Footnote8 In March 2018, a commemorative ceremony was held in Cromwell, New Zealand, to unveil a memorial plaque in honour of Jolly's pioneering war surgery and humanitarian contributions in his hometown of Cromwell, New Zealand (McKenzie-McLean, Citation2018).Footnote9

Memorials to the volunteers of the International Brigades

Due to the transnational dimension of the conflict, memorials to the International Brigades exist in many countries. In Europe, there are memorials in, for example, France, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Germany, Croatia, Hungary, and Poland; they further exist in Canada and the United States. In Spain, memorials to the International Brigades are scattered across the country; some are dedicated to specific volunteers, brigades, or national groups (none to New Zealanders), others to the International Brigades in general (Gil-Higuchi, Citation2014; Spanish Civil War Memorials, Citation2021). Several new memorials were inaugurated in 2011, which marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the official creation of the International Brigades. Commemorative days and anniversaries represent the ‘ultimate embodiments of a memorial consciousness’ (Nora, Citation1989: 12) on which celebrations and ceremonies invest older memorials with life and new ones are often being inaugurated. This happened in 2011 in Madrid with the unveiling of a memorial to the International Brigades at the site of a decisive 1936 battle during the siege of Madrid, in which the International Brigades helped defeat Nationalist forces. Among those killed in the defence of the city were also two New Zealanders who fought in the Commune de Paris Battalion of the International Brigades (New Zealanders march, Citation2021). However, the memorial proved contentious and placed the International Brigades at the centre of Spain's recent memory battles between left and right. For the left, it offered the opportunity to shape the collective memory of the Brigadiers as ‘volunteers for liberty’ and ‘agents of democracy’ and to steer away from the association with Communism, which had also been an issue in New Zealand at the time of the conflict. For the right (which had emerged from Francoist circles), it provided the means to emphasize the connection of the Brigades with ‘history's largest genocidal killer, Joseph Stalin’ (Marco and Anderson, Citation2016: 391–393). Memorials can act as a conduit for reconciliation or for contention, as in the case in Madrid. The historical division between left and right that lead to the Civil War and the involvement of the International Brigades is still topical in the twenty-first century, demonstrating that the memory of the past clearly impacts contemporary society in the present.

Commemorations in New Zealand

In New Zealand, the only memorial to a New Zealander involved in the Spanish Civil War prior to 2011 consisted of the naming of a local reserve in 1942 in Auckland. It honoured one of the nurses, René Shadbolt, who had provided medical support during the conflict. A memorial to American nurses and hospital doctors engaged in the conflict was likewise erected in Belalcázar, Spain, in 2016 (Spanish Civil War Memorials, Citation2021). The naming of public spaces is a strategy for constructing lieux de mémoire, and hence functions as a carrier to bring the past into the present. Moreover – following social theorist Pierre Bourdieu – scholars suggest that toponyms represent ‘symbolic capital’ (Citation1991: 238–239), that is, they function as ‘a means of creating social distinction and status for both elite and marginalized groups,’ such as, for example, women and migrants (Rose-Redwood et. al, Citation2010: 457). Worldwide, there exists a gender imbalance in official names for public places. It is hence significant that – as early as the 1940s – a gender-inclusive approach was taken in the memorialization of heroic acts during wartime by naming a reserve after Shadbolt. However, the fact that medical staff and not those who participated in the fighting in the war were commemorated shows that New Zealand's first Labour government still shied away from aggravating Catholic and anti-communist voters. Hence even within a left-leaning government, there remained a need to address and consider the concerns of the Catholic community and those with centre-right perspectives, which has had an impact in Aotearoa/New Zealand on the commemoration of events that took place during the Spanish Civil War. Moreover, no signs acknowledged the reason for the naming of ‘Shadbolt Park;’ after the oral dissemination of the history associated with its naming had ceased, that is, it had stopped being part of communicative memory, its meaning was lost over time. Only in 2011, during the seventy-fifth anniversary of the International Brigades, a commemorative bronze plaque, accompanied by a ceramic portrait of Shadbolt clad in a nurse's uniform, was unveiled at the site in the presence of the Spanish Honorary Consul. The recent re-dedication of the reserve not only raised public consciousness of the historical events behind the name of the reserve, but it also reflects an increased awareness of a lack of diversity in urban space. In addition to commemorating the significance of the historical event, the act functioned as a tool to reshape collective memory and augment the representation, visibility, and recognition of women in New Zealand society.

Commemorative plaque to all New Zealanders who contributed to the defence of freedom in Spain (1936–1939)

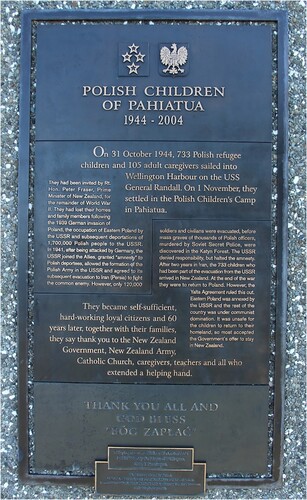

In the same year, a bronze memorial plaque to ‘all New Zealanders who contributed to the defence of freedom in Spain (1936–1939) – For Spain and Humanity’ was unveiled by Wellington's Mayor and the Spanish Ambassador to New Zealand (Derby, Citation2011: 18) (see ). The plaque was installed on the wall of Frank Kitts Park along Wellington's waterfront two months later (see Map 1). Not unintentionally, the wording of the plaque is similar to the wording used in the 1939 memorial service. In addition, the expression ‘For Spain and Humanity’ had a particular connection to both Spanish and New Zealand history: it firstly, formed part of the Andalusian regional anthem which had been performed for the first time a week prior to the military uprising in Spain in 1936; it was forbidden under Franco and only reinstated as the official anthem of Andalusia some forty years later. ‘For Spain and Humanity’ was, moreover, the motto of SMAC, the grassroots organization set up in 1936 in Dunedin responsible for raising funds to send medical staff and supplies to Spain to aid the Republican cause. Hence the wording of the plaque reflects the symbolic aspect of cultural memory and the use of cultural narratives as powerful enablers in connecting our past to the present.

Figure 1. Commemorative Plaque to all New Zealanders who fought in the Spanish Civil War, Wellington, New Zealand. Photo credit: Andrea Hepworth.

What were the reasons for the inauguration of this memorial some seventy-two years after the end of the Spanish Civil War? How does the memory of the Spanish Civil War play a role in Aotearoa/New Zealand? And who were the memory entrepreneurs behind its installation at Wellington's waterfront? Memory and memorialization have been focal points by a vast number of community groups, victims/survivors and non-governmental organizations in post-conflict times, in particular regarding conflicts of which there are few, if any, eyewitnesses left, such as former participants in the Spanish Civil War or the Second World War. This can be attributed to the fact that the passing away of the ‘witness generations’ leads to changes in the representation of the recent past, with a shift from communicative to cultural memory, as well as an increasing presence in the media. The inauguration of the plaque and the official commemoration decades after the event can be attributed to this shift, caused by the perishing of the survivor generation, here the participants of the Spanish Civil War. At that time, as discussed earlier, communicative memory – due to its limited temporal horizon – is superseded by a new type of memory, cultural memory. Cultural memory is not only embodied in repeated performative acts, but it is also linked to places. These sites could be ‘authentic’ places where an event has taken place, or a site where an event is staged, for example the site of a memorial. The inauguration of the Spanish Civil War Memorial plaque was clearly enacting cultural memory.

Local interest in the Spanish Civil War in New Zealand

Local interest in the history of New Zealand participation in the Spanish Civil War manifested itself in a 2006 seminar on the topic by the New Zealand Trade Union History Project. Organized by local historians, the seminar examined the role of local trade unions in aiding the Republican cause and focused on the presence of New Zealanders not only in the International Brigades but also on the involvement of medical staff. The event was sparked by newly accessible documents on New Zealanders in the Spanish Civil War obtained from formerly classified archives opened after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The seminar culminated in the reissue of a 1937 New Zealand eyewitness account of the conflict (Derby, Citation2011: 17; New Zealand, Citation2012). This was followed by the publication of the first book solely focused on the involvement of New Zealanders in the Spanish Civil War, in which the erection of a ‘physical memorial to New Zealand's Spanish Civil War veterans’ was envisioned (Derby, Citation2011: 17). The strengthening of ties with Spain – cemented by the opening of a Spanish Embassy in Wellington in 2009 and the signing of a new reciprocal working holiday scheme – ultimately made this possible. Even though International Brigades volunteers are widely honoured in many of their countries of origin, and in Spain, in New Zealand they were almost forgotten. After the successful lobbying of historian Mark Derby to rectify this (Citation2023), the plaque was provided and unveiled by the Spanish Embassy. The promotion of collective memory is often aided by actors within state institutions – such as, for example, the Spanish Ambassador – in conjunction with local memory entrepreneurs who act from below to convey ideas and narratives about the past. Moreover, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), in power since 2004, had been the driving force behind the passing of the LHM in 2007 to honour ‘all those who suffered injustices and grievances’ during the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship (Ley Citation52/Citation2007, Citation2007), hence the proposal for a memorial plaque for those who assisted the Republican cause in New Zealand was in line with the Spanish government's objectives. Thus here, the bottom-up mnemonic initiatives by local historians and unions, eliciting support from state actors, such as the Spanish Embassy – Ambassador Gómez also wrote the foreword to Kiwi Compañeros – resulted in the conjoint memorial project at the waterfront.

The placement of the memorial plaque at the waterfront can be linked to a mixture of historical and cultural-political reasons: One of the strongest supporters of the Spanish Republican government in New Zealand were unions – one of them the Waterside Workers and Seamen's Union (Chaudron, Citation2012: 130) – and some of the New Zealanders who participated in the conflict had worked on the wharves; there was hence a strong local connection. Furthermore, the Wellington Waterfront Redevelopment guidelines called for the inclusion of components of historical and contemporary culture along the waterfront (Wellington Waterfront Framework, Citation2001: 6). Consequently, some other plaques recording significant events, such as the arrival of the Polish refugee children in 1944, and the memorial plaque to the arrival of the United States Marine Corps to New Zealand, had already been displayed at Frank Kitts’ waterfront. The area was becoming a ‘commemorative mile’ for Wellington; by 2023, there were twenty memorial plaques located at the waterfront at Frank Kitts Park.

Global memory discourse

As shown above, there is clearly a cultural and social connection of local life histories with a particular space, here the Wellington waterfront, and historical events. However, the memory of the Spanish Civil War, the International Brigades and their fight against fascism certainly also form part of a global memory discourse. Global memory refers to the world-wide emergence of concerns with the past and its codification in contemporary political, social, legal, and cultural discourses. It further comprises the process and experience through which global matters of interest become localized and part of collective memory. With their notion of ‘cosmopolitan memory,’ Levy and Sznaider set new parameters for collective memory by placing it within a global context. Cosmopolitan, or global, memory encompasses the generally mutually exclusive categories of universalism and particularism. When formulating their concept, the scholars analyzed the ways in which the Holocaust has been remembered in various countries and argued that the ‘abstract nature of ‘good and evil’ that symbolizes the Holocaust . . . contributes to the extra-terrestrial quality of cosmopolitan memory’ (Levy and Sznaider, Citation2002: 97, 106). Other narratives with a global, universal scope, although not comparable to the Holocaust in any way, is the Spanish Civil War. The ‘fighting against evil’ was foregrounded in the International Brigades’ employment to Spain and memorials to them exist, as discussed above, in more than fifty countries; their memory is therefore truly a cosmopolitan memory. Public annual commemorative ceremonies at International Brigades memorials take place worldwide to remember this corps of volunteers; the commemorative plaque at Wellington's waterfront is embedded and integrated in this global memory. The commemoration of war dead constitutes an important part of the collective memory and identity of a country, hence the remembrance of New Zealanders who participated in the Spanish Civil War – although low in number – forms part of the collective memory of New Zealand.

Second World War and the US marines in New Zealand

This section focuses on the ‘transnational memory’ of Second World War events in New Zealand, following Jenny Wüstenberg's understanding of transnational remembrance as the ‘relationship between multiple localities of memory’ (Citation2019: 374) which does not imply the existence of one homogenous mnemonic narrative or perspective of an historical event, but rather acknowledges its impact across different cultural and national borders. New Zealand was one of the first countries to enter the Second World War in September 1939 after the expiration of Britain's ultimatum to Nazi Germany to withdraw its troops from Poland. About 140,000 New Zealand men and women fought overseas, of whom an estimated 12,000 died. Of the around 16,000 Māori who served, around 3,600 were deployed in the twenty-eighth (Māori) Battalion (Sheffield and Riseman, Citation2018: 142). The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1941, which sparked the United States’ involvement in the Second World War, and the fall of Singapore to Japanese forces in 1942 highlighted that New Zealand needed a powerful Pacific ally. Consequently, in mid-1942, American troops were sent to New Zealand to strengthen its defences, as well as for training before heading into battle in the Pacific. Before the US Marines’ arrival, there was a ‘distinct feeling of aloneness in New Zealand against the threat of invasion’ (Banning, Citation1988: 38). The more than 48,000 US Marines that were in Aotearoa/New Zealand by July 1943 certainly bolstered its defence, and also had a crucial impact on the cultural practices of New Zealanders.Footnote10

Between 1942 and 1944, New Zealand operated as ‘one of the main locations for U.S. Forces in the South Pacific Command,’ with about 100,000 American troops garrisoned in the country. Army camps were placed around Auckland, and US Marines were stationed in the wider Wellington region (Wanhalla, Citation2021: 79, 87). Social relations between the troops and the local population developed, and their stay became known as the ‘friendly invasion.’ The residing of thousands of well-remunerated Americans had a decisive economic, social, and cultural effect on Aotearoa/New Zealand, in particular in the areas surrounding the camps (Carlyon and Morrow, Citation2013: 138–139). The American Red Cross compiled lists of New Zealanders willing to host Americans for the weekend, the New Zealand-America Friendship Group organized meetings, and US Marines in Wellington attended church services alongside New Zealanders at Old St. Paul's (see Map 1). Moreover, enclaves of American cultural outlets developed around the camps; the Majestic Cabaret, in which the US Navy's Marine Band often played swing and jazz, became Wellington's most popular dance hall. Consequently, almost 1500 New Zealand women married American servicemen during these years (Brookes, Citation2013: 299–300).Footnote11 However, the American military's racial attitudes and the sexual and social relations between them and the local population also resulted in cultural clashes.Footnote12 Most United States personnel left New Zealand by mid-1944.

Commemorative plaque to the 1942 arrival of the United States Marine Corps

The commemorative plaque to the 1942 arrival of the United States Marine Corps was the first memorial to the US Marines in Aotearoa/New Zealand (see ). Although the erection of a statue of liberty at Wellington harbour was suggested in 1945, it was only in 1951 that the New Zealand government decided to install a memorial plaque at Aotea Quay.Footnote13 It consists of three parts: a plaque dating from 1951, signed by the Second Marine Division Association, dedicated to ‘[t]he People of New Zealand,’ inscribed with the sentence ‘[i]f you ever need a friend, you have one,’ adorned with the Marines’ motto ‘semper fidelis;’ a second, larger plaque, enclosed with the names of the major Pacific battles in which the Division participated, stating that ‘[t]he United States Marine Corps arrived at this Quay in May 1942 and left from here to serve in the Pacific theatre of war;’ and a third tablet clarifying that the memorial was initially inaugurated in 1955, and re-dedicated in March 2000, when it was moved to its current location at Frank Kitts Park amid the reshaping of Wellington's waterfront. The Second Marine Division had arrived in June 1942 at Aotea Quay, where the plaque was originally located. Aotea Quay is about 3 km away from the publicly accessible site at the waterfront (see Map 1). It is unknown why May is given as the arrival month, as the first Marines arrived on 12 June in Auckland and on 14 June in Wellington (US Marine Corps Memorial, Citation2012). The catalyst for the creation of the plaque was the 1951 collective security agreement, the ANZUS treaty, which bound Australia and New Zealand – and, separately, Australia and the United States – to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area. The ANZUS treaty between New Zealand and the United States fell apart in 1984 due to a dispute over visiting rights in New Zealand for American ships and submarines capable of carrying nuclear arms (Phillips and Maclean, Citation1990: 153). The inscription on the plaque evoked the memory of the past allied connections between New Zealand and the US to use it for its current political objectives in the 1950s and formed part of official state discourse. Political elites, suggests Richard Lebow, construct institutional memory narratives that are ‘self-justifying and supportive of their domestic–and foreign–policy goals’ (Citation2006: 6). The US Marine memorial plaque is clearly connected to political events important to the New Zealand and American governments but, as will be discussed below, seems to lack a local memory discourse to complement the official remembrance. Although there undoubtedly exists a local connection with this part of New Zealand history, this memorial, I argue, is clearly shaped by institutional, or political memory.

Figure 2. U.S. Marine Corps Memorial Plaque, Wellington, New Zealand. Photo credit: Adelaide Archivist.

Between 2008 and 2017, New Zealand was governed by a centre-right government with an emphasis on the revitalization of connections with the United States. Consequently, the New Zealand government developed robust policies in defence, trade, and tourism. This focus was evident during the seventieth anniversary of the arrival of the US Marines in 2012, which included official ceremonies by the New Zealand government and the US Marines at both the National War Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Wellington. Moreover, a replica of the commemorative plaque was installed in the Semper Fidelis Memorial Park at the National Museum of Marines in Quantico, Virginia (US Marine Corps, Citation2012). Although official commemorations in Aotearoa/New Zealand incorporated the original plaque at the waterfront, the main focus of the official mnemonic discourse were the ‘70 years of formal bilateral relations’ between the two countries, and the recently signed ‘Wellington Declaration’ (US Marines return, Citation2012). The Declaration envisioned cooperation in the Pacific region to address ‘broader regional and global challenges,’ an expansion of ‘commercial and trade relations’ between New Zealand and the US and broader ‘political-military discussions’ (Wellington Declaration, Citation2014). Hence in line with the original objectives behind the installation of the commemorative plaque in the 1950s, also the seventieth anniversary celebrations served mainly to reinforce political – and commercial – interests.

During the eightieth anniversary celebrations in June 2022, the plaque was not included in the official celebrations. These took place at the Pukeahu National War Memorial Park in Wellington, which is about 3 km from Frank Kitts Park (see Map 1). The Memorial Park was inaugurated in 2015 – matching the upsurge in performative memorialization in Aotearoa – and designed as the national mnemonic space to remember Aotearoa/New Zealand's experience of war and conflict and the ways in which these shape its national identity (Pukeahu, 2022). There is also a United States Memorial located at the site since 2019, albeit somewhat offset (Woodward, Citation2021: 45). Is the reason for the exclusion the relocation of the plaque, the fact that it is not marking the authentic, historical landing space of the Marines? This does not seem to be the case: during its original placement at Aotea Quay from 1955 to 2000, the plaque was already largely forgotten, which substantiates James Young's observation that memory invested in the traditional monument, rather than the audience, fosters forgetting. Without repeated commemorative events, ceremonies or oral histories which cement a narrative into collective memory, forgetting and the invisibility of monuments is inevitable (Citation1993: 5–13). Moreover, the exclusive focus of the eightieth anniversary commemorations on the newly inaugurated site of national memory confirms that an institutionalized form of memory is utilized by the official state actors to further political objectives.

Narrating local history? The establishment of the Kāpiti US Marines Trust

Only since the establishment of the Kāpiti US Marines Trust in 2009, which incorporated several local, regional and national groups focused on the preservation and promotion of the US Marines’ history in the region, have commemorative activities with a focus on ‘local history-telling’ increased (Memorial Day, Citation2010).Footnote14 After the Marines’ arrival on board the USS Wakefield, the troops were brought by train to Paekākāriki, along the Kāpiti Coast, to be housed in three camps (Camp Paekākāriki, Camp Russell and Camp McKay) (see Map 2). These camps, where the Marines lived and interacted with the locals, in particular Camp Russell, have become the main focus of mnemonic activity in the region. Camp Russell is incorporated into Queen Elizabeth Park where, in May 2012 – spurred by the Trust – a memorial to ten US seamen who had drowned in 1943 during a training exercise at the Kāpiti Coast was inaugurated, in addition to informative panels installed at the site in 1992.Footnote15

Map 2. Map of Wellington to Pahīatua and the Kapiti Coast, New Zealand. Google Inc, 2023. Wellington to Pahıā tua. Google My Maps. https://www.google.co.nz/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1UC_tlc-4uDC1l9Ww2G8s3MdBsrjWPg&ll=-40.894523941482355%2C175.52085461640627&z=10. Screenshot by A. Hepworth.

Here, the transnational memory of the Second World War, in particular the involvement of the US Marines in New Zealand, representing ‘historical events and experiences that transcend national boundaries’ (Wüstenberg, Citation2019: 371), is explored through the grounding in the concrete locations of their stay, the lieux de mémoire of the camps. It is, however, striking that most of the commemorative events do not take place on the anniversary of the Marines’ landing in June, but on the last Monday in May, Memorial Day, a federal holiday in the United States for honouring and mourning US military personnel. This was not only the case with the inauguration of the US Marines Memorial at Queen Elizabeth Park and the annual commemorations held there since, but also with the annual service in honour of the Marines at the church of Old St. Paul's in Wellington. The fact that these official commemorations are neither held on the local anniversary of the Marines’ landing in New Zealand, nor on Anzac Day, Aotearoa/New Zealand's most important day of national commemoration of those who have served in wars, begs the question whether the commemorations do represent cosmopolitan memory.Footnote16 That is, does a mutual interaction between global and local memories take place in these commemorations, or is the mnemonic narrative manipulated and reconfigured to suit one-sided memory politics?[open-strick]

[close-strick]What does this mean for the significance of the commemorative plaque on Wellington's waterfront? The lack of mnemonic activity at the site on the anniversaries the plaque marks, in conjunction with the focus of the Kāpiti Trust on increasing regional tourism at the Kāpiti Coast (Memorial Day, Citation2010), has diminished its significance and visibility in central Wellington. During research for this article, no evidence came to light indicating that the memorial plaque has played a part in either official or unofficial celebrations of commemorative events before or after 2012. Commemorative ceremonies as well as modifications of memorials can be seen as both official expressions of and an appeal to collective memory. Hence the increased emphasis on American memory culture through its focus on Memorial Day and the emphasis on the enhancement of official New Zealand–American relationships through the promotion of ‘World War II US Armed Forces history from 1942–1944 in the Kapiti district’ (About the Trust, Citation2010) are a further sign of institutional memory, ‘discourses issued by elites’ in the service of ‘hidden agendas’ (Ryan, Citation2014: 502). These agendas have changed from political defence policies in the 1950s to commercialization processes in the twenty-first century in which ‘local memories are translated into global discourses that are comprehensible and recognizable by a global audience’ (Björkdahl and Kappler, Citation2019: 383). However, this appropriation of memory to construct imaginaries about people and places is not uncommon to construct cultural and political relations between countries. Moreover, there certainly is local interest and a local connection to the memory of the US Marines in New Zealand, however, this does not seem to involve the memorial plaque at the waterfront, which now constitutes an ‘invisible memorial’ that has receded into the background of public attention (Musil, Citation1978: 508). It remains to be seen if future local engagement and immaterial cultural practices performed at the plaque at Wellington's waterfront re-invests it with relevance and meaning and reverses its invisibility.

Displacement in the Second World War: the Polish children of Pahīatua

The third and last plaque to be discussed also relates to events of the Second World; it is a memorial plaque to more than 700 Polish children who arrived in Wellington in October 1944. These children constitute New Zealand's first invited refugee group. Their journey had started in 1939 with the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, resulting in the deportation of about 1.7 million Polish citizens from Eastern Poland to the USSR and into Siberian prisons and labour camps between 1939 and 1941 (Lebedeva, Citation2000: 28–31, 43). In 1942, over 40,000 Polish soldiers and 70,000 Polish civilian citizens, including many children, were given permission to leave the Soviet Union and subsequently made their way to Iran, and from there to refugee settlements in India, the Middle East, Africa, Mexico, and New Zealand (Stańczyk, Citation2018: 137–138). Aotearoa/New Zealand agreed to accept a limited number of Polish refugee orphans and half-orphans in 1944, and in November, these 733 children and their caregivers were settled at the Polish children's camp at Pahīatua (Manterys et. al, Citation2015: 12–13). Pahīatua is a small rural township in the southern North Island, around 160 km north of Wellington (see Map 2); its name is derived from the Māori words for resting place, pahi, and spirit, atua (Mc-Cardle, Citation1943). In 1945, Pahīatua had a population of 1749, up from 1668 in 1936 (Campbell, Citation1960: 252).

Previously, the camp had been an internment camp for alien civilian internees of the Second World War. To transform the camp into a temporary home for the refugee children, dormitories, dining rooms, a library, a school, and recreation halls were added. For the children, who were traumatized by their experiences of flight and war, it represented ‘a haven of kindliness, peace and benevolence’ with ‘an absence of threat and terror’ (Coates Citation2015: 85). Upon arrival, the children were transported from the harbour to the camp by train, completing the last leg of the journey on army trucks. To make them feel welcome, they were greeted by hundreds of Wellington school children waving New Zealand and Polish flags (Mitchell Citation2019). At first intended as a temporary measure, permanent citizenship was extended to the refugees after the end of the Second World War, when Poland was placed under Communist rule.Footnote17 After the demobilization of the Polish army, some Polish ex-servicemen and other relatives arrived from Africa, India, and Britain, joining some of the children in Aotearoa/New Zealand; only a small number of children returned to Poland or emigrated to other countries (Manterys et. al, Citation2015: 25; Scrivens, Citation2023). Most of the refugees chose to settle in New Zealand after the war.Footnote18 The children and their relatives were instrumental in forming the Polish Association in New Zealand in 1948 in Wellington, around which New Zealand's vibrant Polish post-war community developed. A permanent monument at the remains of the camp site, replacing an earlier ephemeral memorial erected by the children, was inaugurated in 1975 after successful lobbying by a group of former Pahīatua children since 1971 (Manterys et. al, Citation2015: 24). The inscription on the memorial states it was ‘erected by the Polish community in appreciation of the shelter given by the people of New Zealand’ (Scrivens, Citation2019); this first memorial was hence conceived through the bottom-up practices of a local grassroot organization.

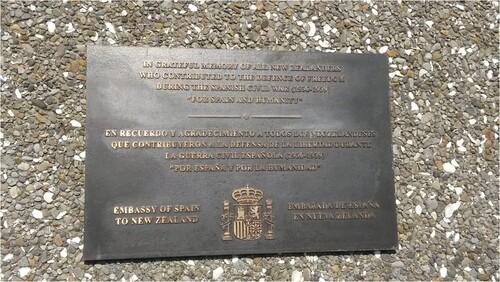

Commemorative plaque to the Polish children of Pahīatua

The memorial plaque at Wellington's waterfront was unveiled in October 2004 by the mayor of Wellington, in the presence of the New Zealand Prime Minister and the Honorary Consul for Poland, who provided the plaque (see ). The message on the plaque reads: ‘Polish Children of Pahīatua 1944–2004. On 31 October 1944, 733 Polish refugee children and 105 adult caregivers sailed into Wellington Harbour on the USS General Randall. On 1 November, they settled in the Polish Children's Camp in Pahīatua.’ Hence similar to the Spanish Civil War memorial plaque, the plaque was furnished by actors in state institutions, here the Polish representative body in New Zealand. However, in contrast to the former, other celebratory events and memorials had been initiated by the Polish survivor community itself, thus their continuous commemorative efforts represent communicative memory from below. It constitutes collective memory that is influenced both from the bottom up, and by state actors from the top down, inscribing the historical event of the arrival of the children into the collective memory of Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Collective identity of the children of Pahīatua

The collective memory of displaced persons is performed, recreated, and renegotiated on an everyday basis. Moreover, forced displacement fundamentally reshapes identity and the outcome ranges from successful hybridization to the perception of enduring misplacement (Halilovich, Citation2013: 231). In the case of the children of Pahīatua, their Polish collective identity was fostered during the first two years of their arrival in New Zealand by carriers of memory – street names in the camp were in Polish and their Polish culture was maintained through language education and celebrations, to prepare them for their intended return to Poland after the war. These initial years laid a foundation for the thriving Polish community and their collective identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand, consisting of what ethnographic historian James Clifford refers to as a blending of ‘both roots and routes’ (Citation1994: 308). The refugees formed a community of belonging through the shared experiences of exile and of arrival in Pahīatua; their Polish language and culture acted as a continuing link to Poland. These experiences are ‘remembered, (re)constructed and enacted in diasporic spaces’ (Halilovich, Citation2013: 1); the collective memory of the former refugee children is reflected in annual local celebrations, such as the Polish festival in Wellington, and mnemonic events surrounding the camp.

The ‘imagined community’ of the children of Pahīatua is hence also clearly connected to New Zealand, the ‘diasporic space’ where they found refuge and most of them stayed. Their collective identity is one of a hybrid nature, like that of many migrants. Eric Lepionka, one of the former Pahīatua Polish children, remarked that there was integration ‘into New Zealand life,’ but also a retention of Polishness (McKee, Citation2014). Postcolonial theorist Homi Bhabha conceptualizes hybridity as a ‘third space’ (Citation2004: 55–57). Even though Bhabha stresses the colonial and postcolonial provenance of this third space, the diaspora likewise functions as a metaphorical space in which the local, the national and the transnational are linked. Exile often induces a specific kind of remembrance that links communal and national histories, as can be observed in the community of the children of Pahīatua.

For most of the children, Pahīatua was, as Lepionka stated, their ‘first family home, it was like [we were] 733 brothers and sisters’ (McKee, Citation2014). The community thus served as a replacement for the family nucleus. The President of the Republic of Poland met with the former refugees in New Zealand in 2018 during his first state visit to Aotearoa/New Zealand. He thanked them for ‘keeping Poland in the[ir] hearts ever since childhood’ and passing ‘Poland and Polishness’ on to their descendants (President meets, Citation2018), hence acknowledging the ‘continuing relationships with the homeland’ that offers its ‘ongoing support’ (Clifford, Citation1994: 304–305); factors decisive to diasporic identities. This was the first time a Polish president had met the former refugees; the visit accompanied a new partnership agreement in which Pahīatua became a sister town with Kazimierz Dolny, a small town in eastern Poland. Moreover, an area near Lublin's city had been renamed Skwer Dzieci z Pahiatua (Children of Pahiatua Square) in May 2006, and in 2018, a square in central Wellington was likewise marked by a memorial plaque and renamed Polskie Dzieci Square (Polish Children's Square). Place names forge ‘emotional attachments to places, even in the face of physical alienation,’ they are interconnected with ‘larger cultural narratives and stories’ (Rose-Redwood et al, Citation2010: 458); the cultural narrative of displacement and arrival of the Pahīatua refugees was (re)constructed in both countries and created a mnemonic space between ‘here (‘where I live’) and there (‘where I come from’) (Halilovich, Citation2013: 1). By the linking of these two lieux de mémoire, one in the diasporic space of Aotearoa/New Zealand, the other in the original homeland, a transnational memory space, an ‘immaterial, ideational space’ (Björkdahl and Kappler, Citation2019: 383) was formed for the collective memory of the Pahīatua refugees. The Polskie Dzieci Square plaque was inaugurated by the Polish President, who also laid flowers at the memorial to the children at Wellington's waterfront (Woolf, Citation2018), hence the plaque marking the children's arrival is integrated into the mnemonic narrative of the refugees.

Re-enactment: commemorative anniversary celebrations

The largest commemorative event before the global Covid-19 pandemic reached New Zealand consisted of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the refugees’ arrival in 2019; forty-one of the Pahīatua children attended the event, down from just under two hundred who had attended five years earlier (McKnight, Citation2023). The event in 2019 was jointly conducted by Polish and New Zealand organizations in Wellington and Pahīatua and included a re-enactment of the children's arrival in 1944. One of the army trucks originally involved in the transport of the refugees led the procession, and, as in 1944, cheering Wellington schoolchildren lined the road with Polish and New Zealand flags, in addition to ‘college pupils dressed in period army, navy and police uniforms’ (Mitchell, Citation2019). Re-enactments such as these are what Paul Connerton terms ‘performative:’ they involve repetition and bodily memory to re-enact the group narrative and hence secure it into collective memory (Citation1989: 40–42).

Both in 2019 for the seventy-fifth and in 2014 for the seventieth anniversary celebrations, there was a private reunion for the remaining Polish children, which also included a wreath-laying ceremony at the former camp and at the memorial plaque at Frank Kitts Park. Just under two hundred of the Pahīatua children attended the seventieth anniversary celebrations, forty-one the seventy-fifth (McKnight, Citation2023).Footnote19 In 2014, there were also week-long exhibitions staged at the Museum of Wellington City and Sea. A documentary was created about the children by a Polish director and commemorations were also undertaken in Poland, where the story of these children was banned until the fall of communism in 1989.Footnote20 Remarkably, the journey of the Pahīatua children now forms part of the Polish school curriculum (Uszpolewicz, Citation2015) and commemorations of their journey take place in Poland, as well as in the countries that provided refugee settlements for these children. Mnemonic activities and events in Aotearoa/New Zealand are jointly conducted by civil society actors, such as the Polish Association in New Zealand, and state actors, such as the New Zealand and Polish governments. Hence there is a combination of bottom-up and top-down mnemonic practices that have resulted in ‘transcultural’ memories, which Barbara Törnquist-Plewa describes as a hybridization of memories that not only crosses borders but also enable the ‘imagining of new communities and new types of belonging’ (Citation2018: 302). The memory of the Polish children of Pahīatua, part of the global memory of the forced Polish displacements during the Second World War, has become part of collective memory in both Aotearoa/New Zealand and Poland.

Conclusion

Hence which function do these memorials to transnational events that have impacted Aotearoa/New Zealand perform in its contemporary collective memory? As was shown in the case of the Spanish Civil War plaque, there is a distinct connection between local identity, memory, and the placement of the commemorative plaque at Wellington's waterfront. The global memory of the Spanish Civil War and the International Brigades is clearly annexed to local life histories of trade unionists and waterfront workers, thus the placement of the plaque at Wellington's waterfront creates a symbolic space, a lieu de mémoire, for these memories. However, since only a small number of New Zealanders was involved in the conflict, public knowledge in parts of the country without a local connection to the veterans is limited.

The Polish children of Pahīatua have made the biggest impact on New Zealand's collective memory. The global memory of Polish displacement as a result of the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War is mediated through the local memories of community of the former Pahīatua children, which are dispersed throughout New Zealand. They have created a vibrant, hybrid Polish/New Zealand community through local memory and heritage discourses, which has incorporated these transnational events into the collective memory of New Zealand.

Both civil society and governmental organizations are key actors in the process of memory formation, however, the memory of the presence of the US Marine Corps in New Zealand in the 1940s is mainly kept alive by top-down mnemonic actors in the service of an authorized collective imagination. Even though former US Marines have come back to New Zealand for commemorative events and there does exist a small community of New Zealanders with a local connection to them, the mnemonic actors behind the commemorations are mostly state actors or other officials with commercial or political interests and are not supported by bottom-up mnemonic activities. Consequently, the memorial to the US Marine Corps on the waterfront does not form part of Aotearoa/New Zealand's collective memory.

In all three cases, the events commemorated at Wellington's waterfront are likewise remembered in other countries that were involved in the event. Hence do the analyzed memorial plaques differ from the function and perception of post-conflict memorials in Europe, for example the memorials to the International Brigades in Spain, as discussed in the first section? They certainly do; the memory of the Spanish Civil War and hence also that of the International Brigades constitute a locally rooted, historically contested terrain where tensions and conflicts emerge in constructing and reinterpreting the past. In New Zealand, on the other hand, no local memory battles or memory contestations concerning the historical events discussed above exist at present. However, Aotearoa/New Zealand has its own problematic relationship with the memory of and issues resulting from colonization, which is, however, beyond the scope of this article.

In conclusion, although all three of the memorial plaques at Wellington's waterfront have been dedicated to the memories of different wars and conflicts, I argue that these memories are not competing. The commemoration of conflicts, diasporas and historical violence discussed in this study expose the intricate interweaving of collective memory and identity. Not only are these memories linked to different facets of New Zealand's history, but the uniform, traditional appearance of the memorial plaques – they are all cast in bronze and of a similar shape and size – and their proximity to each other give the impression of a contextualized narrative, in which even the US Marine Corps memorial has a place. Local interest is piqued by wreaths located in front of some of these plaques at different times of the year, which sparks interest by the public to pay attention to other plaques in the vicinity. In considering these plaques as part of the same memorial landscape, I suggest that these memories have a strengthening impact on each other in line with Rothberg's concept of multidirectional memory.

Caption Text for Images with author detals_31DEC23.docx

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Hepworth

Andrea Hepworth, Department of Languages and Cultures, Victoria University of Wellington–Te Herenga Waka, New Zealand. Her research focuses on post-conflict societies, analysing the lasting impact of traumatic historical events on present-day society. She investigates the marginalisation of specific social groups and their endeavours to secure recognition for their voices and narratives. Her research employs an interdisciplinary approach at the crossroads of history, memory studies, and social movement studies. Her research has been published both in scholarly edited volumes and high-impact academic journals, such as the International Journal of Transitional Justice, the Journal of Contemporary History Journal, the Bulletin of Spanish Studies and the Journal of Genocide Research.

Notes

1 Aotearoa/New Zealand is constitutionally bicultural as a result of the 1840 Te Tiriti o Waitangi/Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document, which ‘enacted a national partnership between all Māori and the British Crown’ (Passey and Burns, Citation2023: 988). Biculturalism in Aotearoa/New Zealand refers to the indigenous Māori culture and that of the settler population of New Zealanders of European descent (Pākehā) and is a source of ongoing debate and contestation ‘in the context of a settler society with a history of colonization’ (Terruhn, Citation2020: 868). The historical events discussed in this article have impacted both the Māori and Pākehā population of Aotearoa/New Zealand, and some examples are given in the study. It is, however, beyond the scope of this article to discuss in depth the ways in which Māori and Pākehā culture differs. For a thorough discussion on the national political imaginary that characterises settler-indigenous relations in Aotearoa/New Zealand, see Terruhn (Citation2020); for an analysis of the changing understandings of place and heritage in Aotearoa/New Zealand, from a Western-centric to a bicultural outlook that increasingly includes Indigenous Māori perspectives, see Passey and Burns (Citation2023); for Māori concepts of memory and history, see Binney (Citation2010); for a discussion on the difference between the transmission of history through Māori oral narratives and through written texts according to Western European tradition, see Binney (Citation1987); for a discussion on examples of memorials to Māori individuals or groups and the relationship of Māori to the European tradition of creating monuments in public places, see Morris (Citation2015).

2 Anzac Day marks the anniversary of the Gallipoli landings by New Zealand and Australian troops in the First World War. In New Zealand, it is a major National Day of Remembrance and has, over time, been extended to remember all New Zealand casualties of war.

3 ‘Memory entrepreneurs’ are actors who seek ‘social recognition’ and legitimacy of their ‘interpretation or narrative of the past’ and who are ‘promoting active and visible social and political attention on their enterprise’ (Jelin, Citation2003: 33–34).

4 The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

5 For Māori oral traditions in a modern context involving practices of oral memory and transmission alongside an understanding of traditional oral practices, see Mahuika (Citation2012).

6 For a comprehensive discussion of New Zealand's response to the Spanish Civil War in the League of Nations, see Chaudron (Citation2012: 129–144).

7 For more on the historical memory movement in Spain, see Jerez-Farran and Amago (Citation2010); for recent scholarship on the impact of historical memory activism in Spain, see Hepworth (Citation2023).

8 See Skudder (Citation1986) for a detailed discussion on New Zealand responses to the Spanish Civil War; also see McNeish (Citation2003), 95–175, for intellectual and journalistic interest in the Spanish Civil War among New Zealanders in the 1930s.

9 The memorial plaque was conceived by the Central Otago Heritage Trust and historian Derby, who, together with descendants of Jolly, the Spanish Ambassador, and the district's mayor, attended the ceremony (McKenzie-McLean, Citation2018).

10 See Coates and Morrison (Citation1991) for a comprehensive discussion on the impact of United States troops in allied countries during the Second World War.

11 For the social, cultural and economic impact of the stationing of US troops in New Zealand on Māori women in particular, see Wanhalla (Citation2021). For the impact of the Second Word War at home on ordinary families and communities, and on Māori society more broadly, see ‘Te Hau Kāinga: The Māori homefront,’ a project that began in 2019 and was still running at the time of writing this article in Citation2023.

12 There was conflict and fights between New Zealand and American servicemen; the most infamous of these was the ‘battle of Manners Street,’ which took place in 1943 outside the Allied Services Club in Manners Street, Wellington (Sheffield and Riseman Citation2018: 182). A later incident in front of the Mayfair Cabaret in Cuba Street in 1945 was sparked by racist attitudes of a group of US marines against Māori soldiers (Pacey Citation2023: 37).

13 The plaque was badly damaged by a truck in 1985. It was only re-dedicated in 1988 (Phillips and Maclean, Citation1990: 152–153).

14 The Kapiti U.S. Marines Trust was established in 2009 by the former mayor of Kapiti, Jenny Rowan.

15 In November 2022, to coincide with the eightieth anniversary of the US Marine's arrival, a new Camp Paekākāriki interpretation site was opened at Queen Elizabeth Park (Camp Paekākāriki, Citation2022).

16 For lucid discussions on the controversies surrounding the cultural politics of national commemoration regarding Anzac Day in the bicultural context of Aotearoa/New Zealand, see McConville et al (Citation2017), Smits (Citation2018), McConville et al (Citation2020), and Gunn et al (Citation2022).

17 Another reason for this was the Katyń massacre in March 1940, in which thousands of Polish army officers had been killed by USSR soldiers. Many of those killed at Katyń were related to the Polish children in New Zealand (Adamczyk, Citation2006: 245–250).

18 The exact number of children who stayed after 1945 could not be ascertained during research for this article. However, all records, and the Secretary of the Polish Association in New Zealand, confirm that most children stayed and very few returned to Poland (Hanson, Citation2023). A statistic from 2017 relating to both the children and former Polish staff of Pahīatua compiled by Józef Zawada – one of the former refugees – shows that of the 394 still alive in March 2017, 283 lived in New Zealand, fifty-nine in Australia, twenty-nine in Poland, nine in the United States, seven in the United Kingdom, four in Canada, one in France, one in Norway, and one in Argentina (McKnight, Citation2023).

19 As part of the commemoration of the sixtieth anniversary of the children's arrival in New Zealand, New Zealand's first refugees: Pahiatua's Polish children (2004) was published. It was written and published by the former children and their descendants and contains over one hundred testimonies.

20 The documentary is entitled ‘Overcoming Fate’ and describes the history of the Polish Children from Pahīatua; it is shot both in Poland and New Zealand. The director of the film, Marek Lechowicz, is a screenwriter from Łomża, who visited New Zealand in 2013 and gathered materials for the production (‘Human Fate,’ Citation2013; AmbasadaRP, Citation2015).

References

- About the Trust, 2010. Kāpiti US Marines Trust. Available from: https://marinenz.com/about?src=nav [Accessed 17 November 2022].

- Adamczyk, W., 2006. When God looked the other way: an odyssey of war, exile, and redemption. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Ambasada RP Wellington (Polish Embassy of Wellington), 2015. Polish Children of Pahiatua – 70th Reunion. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VhwFfFvASsQ [Accessed 21 November 2022].

- Assmann, J., 1995. Collective memory and cultural identity. Translated by John Czaplicka. New German Critique, 65 (1), 125–133.

- Assmann, A., 2006. Der lange Schatten der Vergangenheit: Erinnerungskultur und Geschichtspolitik. Munich: Beck, 2006.

- Banning, W., 1988. A paradise down under: The US Second Marine Division in New Zealand. In: W. Banning, ed. Heritage years: Second Marine Division commemorative anthology, 1940–1949. Nashville, TN: Turner, 38–43.

- Baudrillard, J., 1993. Symbolic exchange and death. London: Sage.

- Bhabha, H.K., 2004. The location of culture. London: Routledge.

- Binney, J., 1987. Māori oral narratives, Pakeha written texts: Two forms of telling history. New Zealand Journal of History, 21 (1), 16–28.

- Binney, J., 2010. Stories without end: Essays 1975–2010. Wellington: Williams.

- Björkdahl, A. and Kappler, S., 2019. The creation of transnational memory spaces: Professionalization and commercialization. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 32 (4), 383–401.

- Bourdieu, P., 1991. Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brookes, B.., 2013. A history of New Zealand women. Wellington: Williams.

- Campbell, E.M., 1960. A survey of New Zealand population: An analysis of past trends and an estimate of future growth. Wellington: Town and planning branch. Ministry of Works.

- Camp Paekākāriki Interpretation Site, 2022. United States Embassy in New Zealand, 21 October. Available from: https://nz.usembassy.gov/memorial-day-2022/ [Accessed 16 November 2022].

- Carlyon, J. and Morrow, D., 2013. Changing times: New Zealand since 1945. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- Chaudron, G., 2012. New Zealand in the League of Nations: The beginnings of an independent foreign policy, 1919–1939. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

- Clifford, J., 1994. Diasporas. Cultural Anthropology, 9 (3), 302–338.

- Coates, I., 2015. This hospitable country. In: A. Manterys, S. Zawada, and S. Manterys, eds. New Zealand‘s first refugees: Pahiatua‘s Polish children. Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee, 85–88.

- Coates, K. and Morrison, W.R., 1991. The American rampant: Reflections on the impact of United States troops in allied countries during World War II. Journal of World History, 2 (2), 201–221.

- Connerton, P., 1989. How societies remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Derby, M., 2009. Kiwi Compañeros: New Zealand and the Spanish Civil War. Christchurch: Canterbury University Press.

- Derby, M., 2011. For Spain and humanity. Labour History Project, 52 (August), 17–20.

- Derby, M., 2022. Douglas Jolly – Biography. New Zealand History, 21 April. Available from: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/people/douglas-jolly [Accessed 24 December 2023].

- Derby, M., 2023. Interview with A. Hepworth. 5 December, Wellington.

- Ellis, M., 2023. Whanganui war memorial, Weeping Woman, to be removed after complaints of ‘racist stereotyping.’ New Zealand Herald, 23 December. Available from: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/whanganui-war-memorial-weeping-woman-to-be-removed-after-complaints-of-racist-stereotyping/GCUKCKOHEZFHXD7EZO7MR7H4S4/ [Accessed 31 December 2023].

- El Senado aprueba de forma definitiva la Ley de Memoria Democrática, 2022. La Moncloa, 5 October. Available from: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/serviciosdeprensa/notasprensa/mpresidencia14/Paginas/2022/051022-bolanos-ley-memoria-democratica.aspx#:~:text=El%20Senado%20ha%20aprobado%20la,inolvidable%20para%20la%20democracia%20espa%C3%B1ola [Accessed 12 October 2022].

- Gil-Higuchi, X., 2014. Interactive map of IB Monuments across Spain. The Volunteer, 9 July. Available from: https://albavolunteer.org/2014/07/aabi-developing-interactive-map-of-international-brigade-monuments-across-spain/ [Accessed 28 October 2022].

- Gunn, T.R., Barnes, H.M., and McCreanor, T., 2022. Wairua in memories and responses to Anzac Day. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 18 (1), 122–131.

- Halbwachs, M., 1992. On collective memory. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Halilovich, H., 2013. Places of pain: Forced displacement, popular memory and trans-local identities in Bosnian war-torn communities. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Hanson, B. ([email protected]), 14 Dec 2023. RE: The Polish Children of Pahiatua. Email to A. Hepworth ([email protected]).

- Hepworth, A., 2023. Memory activism as advocacy for transitional justice: Memory laws, mass graves and impunity in Spain. International Journal of Transitional Justice, 17 (2), 268–285.

- ‘Human Fate’ of Lomzynian exiles, 2013. Podlaski Regional Film Foundation, 1 December. Available from: https://prff.pl/?p=162&lang=en [Accessed 21 November 2022].

- Jelin, E., 2003. State repression and the labors of lemory. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Jerez-Farran, C. and Amago, S., eds., 2010. Unearthing Franco‘s legacy: Mass graves and the recovery of historical memory in Spain. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Kidman, J. and O’Malley, V., 2022. Introduction. In: J. Kidman, V. O’Malley, L. MacDonald, T. Roa, and K. Wallis, eds. Fragments from a contested past: Remembrance, denial and New Zealand history. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 7–18.

- Lebedeva, N.S., 2000. The deportation of the Polish population to the USSR, 1939–41. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 16 (1), 28–45.

- Lebow, R.N., 2006. The memory of politics in postwar Europe. In: R.N. Lebow, W. Kansteiner, and C. Fogu, eds. The politics of memory in postwar Europe. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1–39.

- Levy, D. and Sznaider, N., 2002. Memory unbound: The Holocaust and the formation of cosmopolitan memory. European Journal of Social Theory, 5 (1), 87–106.

- Levy, D. and Sznaider, N., 2006. The Holocaust and memory in the global age. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Ley 52/2007, 2007. Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado, 27 December. Available from: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/26/52/con [Accessed 1 November 2022].

- Mahuika, N., 2012. ‘Kōrero Tuku Iho’: Reconfiguring oral history and oral tradition. Thesis (PhD). University of Waikato.

- Manterys, A., Zawada, S., and Manterys, S., 2015. Background. In: A. Manterys, S. Zawada, and S. Manterys, eds. New Zealand‘s first refugees: Pahiatua‘s Polish children. Wellington: Polish Children’s Reunion Committee, 12–27.

- Marco, J. and Anderson, P., 2016. Legitimacy by proxy: Searching for a usable past through the International Brigades in Spain’s post-Franco democracy, 1975–2015. Journal of Modern European History, 14 (3), 391–410.

- Mc-Cardle, J., 1943. Meaning of Pahiatua: Maori place name. Pahiatua Herald, 10 April, p. 3. Available from: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/PAHH19430410.2.18. [Accessed 7 December 2023].

- McConville, A., et al., 2017. Imagining an emotional nation: The print media and Anzac Day commemorations in Aotearoa New Zealand. Media, Culture & Society, 39 (1), 94–110.

- McConville, A., et al., 2020. ‘Pissed off and confused’/’grateful and (re)moved’: Affect, privilege and national commemoration in Aotearoa New Zealand. Political Psychology, 41 (1), 129–144.

- McKee, H., 2014. Across the world, from Poland to Pahīatua. Stuff, 20 October. Available from: http://www.stuff.co.nz/dominion-post/capital-life/capital-day/10636699/Across-the-world-from-Poland-to-Pahīatua [Accessed 30 October 2022].

- McKenzie-McLean, J., 2018. Forgotten Cromwell war surgeon’s legacy restored. Stuff, 27 March. Available from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/102587854/forgotten-cromwell-war-surgeons-legacy-restored [Accessed 18 December 2023].

- McKnight, G. ([email protected]), 15 Dec 2023. RE: The Polish Children of Pahiatua. Email to A. Hepworth ([email protected]).

- McNeish, J., 2003. Dance of the peacocks: New Zealanders in exile in the time of Hitler and Mao Tse-Tung. Auckland: Random House New Zealand.

- Memorial Day to be celebrated in Queen Elizabeth Park, 2010. Kāpiti US Marines Trust, 30 May. Available from: https://marinenz.com/memorial+day+to+be+celebrated+in+queen+elizabeth+park [Accessed 14 November 2022].

- Mitchell, P., 2019. Pahīatua reenacts arrival of the ‘Polish Children’ to celebrate the event’s 75th anniversary. Stuff, 1 November. Available from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/117078512/pahatua-reenacts-arrival-of-the-polish-children-to-celebrate-the-events-75th-anniversary [Accessed 2 November 2022].

- Morris, E., 2015. Māori monument or Pākehā propaganda? The memorial to Keepa Te Rangihiwinui, Whanganui. In: A. Cooper, L. Paterson, and A. Wanhalla, eds. The Lives of Colonial Objects. Dunedin: Otago University, 230–235.

- Musil, R., 1978. Denkmäler. In: A. Frisé, ed. Gesammelte Werke, vol. 3. Reinbek: Rowohlt, 506–509.

- New Zealand and the Spanish Civil War: A seminar in Wellington, NZ, 4–5 November 2006, 2012. Social History Portal. Available from: https://socialhistoryportal.org/news/articles/109251 [Accessed 22 November 2022].

- New Zealanders March into besieged Madrid, 2021. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Available from: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/page/new-zealanders-march-beseiged-madrid [Accessed 30 October 2022].

- Nora, P., 1989. Between memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire. Representations, 26 (1), 7–24.

- Pacey, M.S., 2023. Our New Zealand home: The USMC in Wairarapa. Masterton: Gosson Publishing.

- Passey, E. and Burns, E.A., 2023. The contested shift to a bicultural understanding of place heritage in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 29 (9), 988–1003.

- Phillips, J. and Maclean, C., 1990. The Sorrow and the pride: New Zealand war memorials. Wellington: Historical Branch with GP Books.

- President meets Polish WWII refugees in New Zealand, 2018. Official Website of the President of the Republic of Poland, 23 August. Available from: https://www.president.pl/news/president-meets-polish-wwii-refugees-in-new-zealand,36787) [Accessed 21 November 2022].