At the start of this year, we raised the question of whether the global rise of populist nationalist sentiment, including the shock of Brexit/Trump to staid liberalisms around the world, meant we should think harder about the role of culture in how political and economic events unfold (Cooper and McFall Citation2017). As the year ends, Trump is still President, Marine le Pen is not, whatever Brexit means remains opaque – and we are witnessing culture (or what, at certain moments, to certain ends, gets called ‘culture’) being drawn into a proliferating range of brutalities. As we write, the headlines tell us about the thousands drowned in the Mediterranean every year amid the ongoing global refugee crisis; the genocidal treatment of Muslim Rohingya people in Myanmar; the announcement of an extended and indefinite, patently xenophobic United States travel ban, buried within an escalating exchange of nuclear taunts between the leaders of the US and North Korea; the entire island of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated US territory – oh let us just call it what it is, colony – has been left without power following Hurricane Maria, while the US President is preoccupied spinning professional athletes’ protests of police violence into nativist offense.

Ifit is true that culture has succumbed to the ‘derivative logic’ of contemporary economies of circulation, deprived of essential attributes and working to scramble and undermine the very premise of culture as essence, the word nevertheless continues to be used to explain things that are politically difficult, intractable, and yes, undeniably brutal. Throughout 2017, alt-right white supremacists have doubled down on the idea of culture as a foundational value, a unique heritage that has the right not only to be displayed, but celebrated and protected – sheltered. In the US, the rumbling controversy over Trump's failure to condemn white supremacist violence at Charlottesville in August has played out as bizarre semiotic algebra. The President's attribution of responsibility to ‘many sides’ was soon elaborated into a Twitter defence of the protests against the removal of a statue of the Confederate General Robert E. Lee, on the grounds that the monument recorded an immutable history ().

Figure 1. Monumentalist history, parodied by @libshipwreck. Editorial and full thread available at Loeb (Citation2017).

This semiotic equivalencing where statues=history=truth is a form of cultural foundationalism that would be as comical as this Twitter correspondent makes it, if only its consequences were not so real and so bloody. Cultural foundationalism seems to be thriving dangerously even amidst an economy of cultural derivatives and a derivative culture.

But perhaps that is to miss the point about the motility of ‘the cultural’. Hall (Citation1960, p. 1) argued that the experience of culture in all its forms was ‘directly relevant to the imaginative resistance of people who have to live within capitalism – the growing points of social discontent, the projections of deeply felt needs’. But it was not the pact struck between anti-capitalist critique and cultural nationalism he had in mind, even if, arriving in Oxford from Jamaica in 1951, he well knew the history of such allegiances. Equally, in the UK and EU, the determination by left-leaning leavers and progressive populists to find ways of talking about ‘peoples’ and ‘nations’ while maintaining a distance from openly regressive positions illustrates just how many ends cultural foundationalism can serve.Footnote1 If culture has been deprived of its true essence, faux foundations can easily be claimed. Let us not forget that Alain de Benoist, the intellectual figurehead of the New European (Far) Right, drew perverse inspiration from Gramsci's cultural populism to forge a philosophy of essential civilizational difference (GRECE Citation1982). For de Benoist and his followers, the discredited legacy of biological racism could only be redeemed through the recuperation and reinvention of Europe's ‘indigenous’ cultures. But then, what foundations are not ‘faux’ – or, at least, invented: fictions fabricated from historical narrative, political praxis, economic interest, and, often enough, concrete?

This is not an enquiry that will be exhausted any time soon. In this, our 10th anniversary year, acting partly out of an instinct for psychic self-preservation, we decided to adopt a local and playful approach to it by exploring how ideas about culture, identity, and capital are working out in a place that happens also to be the original, foundational home of this journal: the post-war British new town of Milton Keynes.Footnote2

On concrete culture

I always thought eternity would look like Milton Keynes. (JG Ballard)

There are two things that Milton Keynes is best known for: its roundabouts and its cows. Or rather, its Concrete Cows ().

Figure 2. Concrete Cows in commercial situ. Image credit: Own work, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19782408.

Together, these two have become a cultural shorthand for the new city. The roundabouts are a function of UK master planners’ switch away from using lights to manage traffic flows at the intersections of the network of grid roads that run between – rather than through – residential and commercial districts. To the average observer, the grid appears as anonymous tarmac thoroughfares; set into green landscaped corridors that divide and connect every corner of the city, the roads have none of the usual urban landmarks people use to navigate around an unfamiliar place. In Milton Keynes, as in other examples from Crawley in Sussex to Glenrothes in Fife, these corridors have become symbolic of the circuitry of loss and loathing that new towns seem to provoke. New towns are derided as settlements without history, without community, in some ways lacking the ‘profound emotional legitimacy’ of ‘nation-ness’ (Anderson Citation2016, p. xx). Yet to focus on the roundabouts in terms of the kinds of culture they funnel away also misses all the green, the way the ‘lazy grid’, as planner David Lock once put it, ‘follow[ed] the flow of land, its valleys, its ebbs and flows’ (in Kitchen and Hill Citation2007).

Sitting alongside the black surface of one of those roads that, we are told, so brutally paved over a rural Buckinghamshire paradise, are the black and white Freisian patterns of bovine concrete. A small herd of three cows and two calves, created in the late 1970s by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation's first community artist-in-residence Liz Leyh, for and with some of the first, mainly school-age citizens of the town. The cows became the symbol for everything that was wrong with Milton Keynes and with the whole idea of building new towns in old countries. They were fabricated models of the real thing, half-sized and made from scrap, a pale bloodless imitation. Instead of a ‘real’ place with ‘real’ history – one hears the echoes of the satirical weight of historicity in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle (Citation1962, itself a mid-century product) – Milton Keynes ends up an inferior simulation, strangely and inhumanely contoured, lashed together with cheaply reinforced concrete.

The irony of this critique is (at least) twofold. First, the cows were the project of a community artist, at some remove from the high altars of studio and gallery. The community artist is, at least in principle, a democratized rendering of cultural activity – one that by definition requires, well, a community, as well as an artist. Leyh herself has since found that her cows’ faces – vandalized and repaired many times, like the concrete facades of much mid-century architecture – are not as charming as they once were. Yet irrespective of aesthetic judgement, this small herd represents more than just an Aunt Sally for the metropolitan literati. As with Wall Street's Charging Bull and the March 2017 addition of Fearless Girl – the former a piece of guerrilla art, now enshrined in popular imaginations and elite self-conceptions of high finance; the latter celebrated as a grassroots challenge, yet actually commissioned as part of an index fund's marketing campaign – the politics of intent and reception get mixed up over time. Milton Keynes’ Concrete Cows are a legacy of the efforts undertaken by the Development Corporation to take the possibility of cultural deficit seriously, to build a place that would develop a mind of its own. Community drama, community centres, community workshops, and community artists were not an afterthought. They were an integral, infrastructural element of the place from the start. The cows are indicative of this infrastructure, they surface it, and in doing so they demonstrate the underlying tensions of its creation.

A second irony is that the raw material of the cows, the concrete from which they are formed and for which they are named – for all of its connotations of unsympathetic 1960s town planning and overbearing architecture – is largely absent from the city itself. ‘Brutalism’, with its now-ubiquitous negative implications of the impersonal and the fortress-like, is a misplaced and overused term, a stand-in for the late-twentieth-century deterioration of post-war public promises. And in any case, the architecture of Milton Keynes is less grandiose, less bellicose in its ambitions than the work that inspired Banham (Citation1966) to coin the name – repurposing Le Corbusier's term for unfinished concrete (béton brut) and in the process collapsing the ethical and aesthetic aspirations of architects and planners, from Le Corbusier to Alison and Peter Smithson, who sought to materialize political, even utopian commitments to civic transparency, community development, and social inclusion. Banham intended ‘brutalism’ to convey memorability of image, expression of structure, and honesty to materials. But that did not stop it from becoming code for 1960s ugly or even, by the 1980s and 1990s – as water stains spread, rust leached from steel reinforcing bars, and concrete crumbled – of the deficiencies of centralized planning or the welfare state more generally. So much of brutalism's poor reputation is, frankly, a symptom of poor maintenance.

The architecture of Milton Keynes is different. The grand projects commissioned in London by Sydney Cook, the Chief Architect of the Borough of Camden, were a quick-build, high-density, low-rise public housing response to post-war necessity. They were designed, just like Milton Keynes’ early social housing, by high-flying young architects with big ideas and free reins. But while Cook championed the concrete streets of Neave Brown's Alexandra Road and the art deco complexities of the architectural partnership Benson and Forsyth's Maiden Lane, his Milton Keynes counterpart Derek Walker, worked along different lines. Wayland Tunley, Norman Foster, Ralph Erskine, and the ‘Grunt Group’ of Christopher Cross, Jeremy Dixon, Michael Gold, and Edward Jones were all ‘starchitects’, and all modernists of one variety or another. Yet the local areas they built in and around Milton Keynes – Fullers Slade, Beanhill, Eaglestone, and Netherfield – are an eclectic mix of typology, build, and finish ().

Figure 3. Midsummer Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes. Image credit: Drone MK, www.dronemk.co.uk.

Milton Keynes’ central shopping centre was described by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as the best looking in the British Isles – high praise in a nation of shopkeepers. It has none of the stark lines and finish of its Arndale-era predecessors. Clad in over a half-kilometre of mirrored glass, it is bordered to the south by Midsummer Boulevard, a street that follows the summer solstice line. Sat at the top of the ridge, around which the grid roads shift and curve, the glass and steel shopping centre, opened by Margaret Thatcher in 1979, is a magnet both for high street brands and cheaply parked shoppers, whose cars are reflected in the mirrors and whose bags egress through the silent yielding of automatic doors. Inside the mall, there is Italian travertine marble lit by clerestories. Outside, under the porte-cochères designed to protect shoppers from the elements and guide them into the place, camped in the underpasses designed to separate pedestrians from drivers, are people busking, begging, eking out. There is a brutality in the consumerism displayed here. But there is little concrete.

A chronology of cultural epochs maps loosely onto the historical palimpsest of the new city. At its utopian outset, and evidenced through the production of The Plan for Milton Keynes (Citation1970), there was the culture of the planner. This mid-1960s-to-early-1970s layer is infused with the post-war consensus of the democratic process, equality or at least a striving for equilibrium, a faith both in the capabilities of scientific methods to predict how and where the place would need to evolve and in the abilities of municipal agents to chart a course to get it there. A subsequent stage introduces a culture of pioneers, which collates the early settlers, the professionals and academics, the builders and workers, who were employed by and in the city and who moved into its early housing schemes, the yellow residential areas mapped out in the strategic plan. These pioneers are identified and valorized through the imagery of muddy roads, muddy gardens, and a spirit of engaging with and conquering the unknown. Such pioneering spirit, like its wild Western colonial predecessors, often overlooks and overwhelms that which it encounters on the way, indigenous populations and environments alike – and indeed, part of the legacy of modernism, and the modernist city, is its persistent disregard for the particularities of place.

As the city became established, reflecting a more developed infrastructure and increased private investment, another temporal layer can be seen in the culture of commercial capital. The city was always intended to serve as host to capital, and it was actively sold in a global marketplace of corporate clients who might be enticed to relocate there, in order to provide jobs for the pioneers and subsequent waves of settlers and populate the purple employment areas of the strategic plan with iconic buildings and brands. As this commercial imperative became better established, more firmly embedded in the material infrastructures of the city, there also developed a culture of memorialization, which, driven by retired pioneers or enthused newcomers, seeks to preserve both the essence and legacy of the plan. This recognizes the unique cultural values that the city's planners had evoked and seeks to staunch the slow dilution of its identity in the face of a perceived deliberate decline of public service and public spirit.

A final layer, the cultural topsoil of the city, is its emerging culture of culture – out of which the decision to bid for the 2023 European Capital of Culture (ECoC) is growing. This process catalyses the earlier layers into a cohesive and compelling argument for another wave of cultural and capital investment into the city that would acknowledge the uniqueness of the city's past, the challenges of the present, and the potential of its future.

On European capitals of culture

Cultural identity […] is a matter of ‘becoming’ as well as of ‘being’. It belongs to the future as much as to the past. It is not something which already exists, transcending place, time, history, and culture. Cultural identities come from somewhere, have histories. But, like everything which is historical, they undergo constant transformation. Far from being eternally fixed in some essentialized past, they are subject to the continuous ‘play’ of history, culture, and power. Far from being grounded in mere ‘recovery’ of the past, which is waiting to be found, and which, when found, will secure our sense of ourselves into eternity, identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past. (Hall Citation2003, p. 236)

At the heart of Milton Keynes’ branding strategy is its bid to be a ECoC in 2023. There is, of course, a major tension at the heart of this approach, a contradiction that is glib and obvious, but also accurate in a way that punctures pretensions: A ‘pro-Brexit’ city based on the voting patterns in the 2016 referendum on EU membership, Milton Keynes has placed a key plank of European cultural policy at the centre of its place-branding strategy. In the shadow of that contradiction, we might want to raise questions about the distance of local policy elites from the voting public. For we know how important cultural interests – embedded in particular places with particular people who identify themselves and their attitudes and values with their particular histories – are in cleaving leave and remain voters (McAndrew Citation2016).

The pursuit of the ECoC designation in Milton Keynes also tells a story about the imagination of the urban – and its distance from the rural – in British public policy. In both Liverpool and Glasgow, previous holders of the ECoC designation in the UK, the European elements were secondary to interventions focused on physical infrastructure or social development. This approach is likely to continue as the opportunity to engage in the actual cultural tensions of contemporary urban Britain is missed. Instead, there will be a branding strategy that is dependent on ignoring the divisions between those consuming and engaging in state-supported culture – those who are, broadly speaking, the pro-EU constituency – and those who may be least likely to identify ‘culture’ with the formal settings of the gallery or the museum, who reject the integrative pan-European project represented by the EU as a cosmopolitan or even ‘globalist’ imposition. (The echoes here of race and imperial history are not incidental.) In the act of using a cultural festival as brand, the complexity of a city as a set of cultural practices, and thus as a rich resource for narrative and design, is flattened in the urban policy imagination.

This flattening is perhaps intensified by a ‘culture’ of audit and transparency that has gradually, as elsewhere, seeped into the practice of staging cultural events in the twenty-first century (Selwood Citation2006). This approach, with its associated modes of measurement and evaluation, is in some ways the ambivalent price exacted by the culture of commercial capital in the chase for modernity that seems ever out of reach. Indeed, the audit has become a technology of capital, and a target of cultural critique, even as it echoes its past life as an ostensibly progressive technology of civic governance. We might even note how the very form-follows-function philosophy that turned ‘brutalist’ city halls inside out in order to display their social and political purpose on their public-facing surface was itself a manifestation of a drive to transparency as a vehicle of participation and pillar of progress. The ambivalence of the audit, and of transparency more generally, is dependent on a set of research methods that, in themselves, have a ‘social life’ (Campbell et al. Citation2017). And these histories have shaped the faith shown by policy-makers in the transformative power of the cultural intervention. It is a faith, in keeping with modern ambivalence, dependent on social scientific numbers that are often de- or re-contextualized away from the narrow, and technically cautious, settings of their initial conception.

The social life of methods – quantitative, qualitative, and those somewhere in-between – has been a core concern of this journal since its founding. Yet methods weigh heavily on culture and the ways culture is objectified and made to circulate. Despite continuing attempts to square the circle, the specifically cultural effects of self-explicitly ‘cultural’ activity may remain resistant to measurement (Crossick and Kaszynska Citation2016). What can be measured becomes valued. But measures and evaluations are often limited in what they can tell us about the specifics of place or culture, or they rely on some knowledge of those specifics – the ‘priors’ of Bayesian probability – before they can work. More to the point, the methods themselves tell us something ‘cultural’, even – especially – in what they leave to one side. The number of events staged, level of audience attended, amount of pounds spent: these and related measures will likely be reported wherever the ECoC ends up being staged. But how were the events received? Did people identify with them, and if they did, to what effect? Were they the same events that one would have encountered had the ECoC been located in a different city? Who was not invited to the party, and who decided on their own not to come?

The ‘flattening out’ of measurement is thus potentially matched by a ‘flattening out’ of practice. In a ‘fast policy’ environment (Van Heur Citation2010, Peck and Theodore Citation2015), we may well find a reliance on tried-and-true models of staging festivities, both literal and more metaphorical. Given its concrete cows, it is probably no surprise that Milton Keynes has succumbed to the ‘cow parade’ that has become a go-to cultural model for many festival cities around the world, and which has seen an entire menagerie on parade: bears, penguins, giraffes, elephants, lambananas, Gromits, and so on. The festival city is also likely to see the street theatre popularized elsewhere, the spectacle of giant puppets, the celebration of past glories – all familiar expectations for planners and attendees alike. These may well provide high estimated audience figures, high estimated economic impact, but how does the embrace of such forms of measurement – the methods of valuing cultural identity and cultural impact themselves – shape active and unfolding forms of belonging, identity, and difference? Where does this leave the culture of the city? Is our stock of capital accumulating or diminishing? Speaking of the ‘cultural apparatus’ in 1959, the words of C. Wright Mills seem prescient:

You of England, I think, are living off a capital you are not replenishing. The form toward which your establishment now drifts may of course be seen in a more pronounced, even flamboyant way in the United States of America. (Mills Citation2008, p. 212)

On capital as culture

Milton Keynes makes visible the way all cities, all places, are the outcomes of cultural practice. It was, just like the Open University that is also based there, part of a post-war social democratic political settlement. To survive, the town and the university have both had to ‘pivot’ – to the neoliberal economics of Thatcherism and, more recently, to the new fundamentalisms of ‘smart’ governance. Yet the task is not simply to interrogate the culture that ‘takes place’ in a city – unfolds through it and becomes rooted in it – but to understand the city itself as source material for production, circulation, and consumption of culture, as well as for cultural critique. Milton Keynes is different by design and that history makes it a powerful object lesson in the ways capital is always cultural and the ways culture is always capitalized. If a city has to become a capital of culture, it is first and foremost with the purpose of attracting capital – cultural and otherwise. Finding ways of displaying and describing the capacity of being and becoming an asset is the key to the cultures of ‘value creation’ and ‘value-added’ that inform these kinds of incentives policies.

And yet, what is capital, anyway (Muniesa et al. Citation2017)? We might define it as a sum of money that can be accounted for from different calculative angles. This would certainly be the kind of answer an accountant or an economist might give, and it opens up a variety of ways to consider capital – to measure it, to assess it – and the same applies to ‘value’ more generally. But we might also take a step to one side to think about capital as a way of seeing things: that is, as a semiotic engine, a worldview, a performative prism, and finally – yes – as itself culture, even a brutal culture. The doubling of culture and capital, capital and culture, is a reminder of how – economically, politically, socially, geographically – cities, centres, and capitals come about. Just as we have asked with regard to states (Scott Citation1998) and markets (Fourcade and Healy Citation2017), we should ask: What does it mean to see like a capital, to see like capital? Let us be brief: To see like (a) capital means, in part, to open up a particular sort of future, and a particular sort of value. To see Milton Keynes as capital (of European culture, or of future value) means to see, to speculate, in terms of the ‘return’, that which is (re)valued through the creation of an expectation of future yield.

The return, a financial category par excellence, the heart of capital, is also useful as an analytical manoeuvre, for it identifies a point of intersection between culture as object of value and culture as practice of valuation. What kind of ‘return’ is hoped for, aspired to, in the new–old embrace of culture by the Milton Keynes city government? The question opens up others. What about the embrace of culture by proponents of Brexit? Or by those seeking to explain the ‘values’ of voters – leavers in the UK or Trump supporters in the US – through appeals to region, to class, or to the solidarity promised by whiteness? Culture and economy, economy and culture: for readers and contributors to the Journal of Cultural Economy (JCE), these have always been both object and analytic, and the richness of this double life will continue to offer compelling returns.

Future returns

What is old is new again: new identity politics and new class conflicts, new nationalisms and new nativisms, new populisms, new authoritarianisms, new thuggeries – all operating under the sign of culture, or said to be one of its avatars. In this context, JCE occupies a unique position, with the potential to offer a unique perspective and intervention. Since the journal's founding, we have tracked the many ways all things ‘economic’ are made and remade. In this inquiry, we have learned well the utility of paying attention to the contingent connections and disconnections of material and immaterial infrastructures, technical and popular discourses, social and political practice. We have learned how to pay attention to, in short, the concrete. After all, as a composite building material, concrete only appears so solid and stone-like retroactively; the fluid slurry must first be helped along until it hardens, held in place by wooden frames and reinforced by steel rebar. With this history and the way it has shaped the identity of our own community in mind, but with the exigencies of the present and future very much unavoidable, we thus return to the other half of our name, to interrogate the making and unmaking of culture.

At the end of our first decade, two pillars of the journal's editorial leadership – Michael Pryke and Paul du Gay – are stepping down to join the wider editorial board. Michael and Paul are cornerstones of the cultural economy project. They were both doctoral students at the Open University when John Allen, Tony Bennett, Vivienne Brown, John Clarke, Allan Cochrane, Stuart Hall, Doreen Massey, Graham Thompson, Margie Wetherell – among many others – were thinking through the problem posed by culture and its others, especially with regard to space, society, identity, gender, cities, the state, organizations, crime, finance, and so on. Back then, faculty might be locked in a room together for years to come up with answers. (We exaggerate but not as much as you might think.) They had to produce answers in a form that could be taught at a distance, to students who, for a modest fee, registered on courses with no formal entrance requirements. The University of the Air, as it was originally to be called, was to offer students who had not had the opportunity to study at a ‘concrete, brick, or stone’ university the best that academics of its generation collectively had to think and say. It was by playing their parts in this collective experiment that Michael and Paul developed their thinking about what a ‘cultural economy’ might be (see, e.g. Allen and Pryke Citation1994, du Gay Citation1997, du Gay et al. Citation1997, du Gay and Pryke Citation2002). It is hard today to imagine all that intellectual heft being orchestrated for students first. That cultural economy thinking became part of a major institutional research programme and a fully autonomous journal – with the support of Karel Williams, Michael Savage, and especially, of course, JCE's founding editor Tony Bennett, with the ESRC-funded Centre for Research into Socio-Cultural Change (CRESC) behind us – mirrors the chronologies of cultural, social, and economic change we set out here.Footnote4

Paul du Gay, whose publications going back more than two decades helped carve out the field, has been on the Editorial Board throughout the last decade and returned to take on an editorial role in 2014. Michael Pryke, meanwhile, worked, alongside Tony Bennett and Liz McFall, as founding editor of JCE beginning in 2006. He became Editor in Chief, overseeing production, in 2012, as the journal grew from three then to four and to now six issues per year. This happened at a time when universities across the world found themselves locked in a paradox of new-found importance and crippling self-doubt, in which so much time is spent counting that it is becoming harder and harder to get anything else done. That we are still here, still growing, and now have our own vital audit measure – our first impact factor – under our belt is in no small part due to his efforts. Both Paul and Michael will stay on as members of the JCE Editorial Board and will remain integral contributors to the future of the journal. We list our thanks above – to the many people and institutions, as well the contexts that fostered them, who have helped impel this project forward – as an encomium to them and their accomplishments.

This bit of history is also a reminder that cultural economy is, and always has been, a collective project. It will remain so, for we are also welcoming several new members to the editorial team. We are pleased that Fabian Muniesa has jumped wholeheartedly into his new role as Chair of the Editorial Board, which also has four new members: Ismail Erturk, Liz Moor, Nick Seaver, and Dave O’Brien. Carolyn Hardin is also joining the team as our new Reviews and Commentaries Editor, and Lauren Tooker is now one of our Associate Editors. Melinda Cooper, Joe Deville, Bill Maurer, and Managing Editor Josh Clark will continue on in their current roles as Associate Editors. Finally, we are excited that Taylor Nelms will join Liz McFall as Co-Editor in Chief.

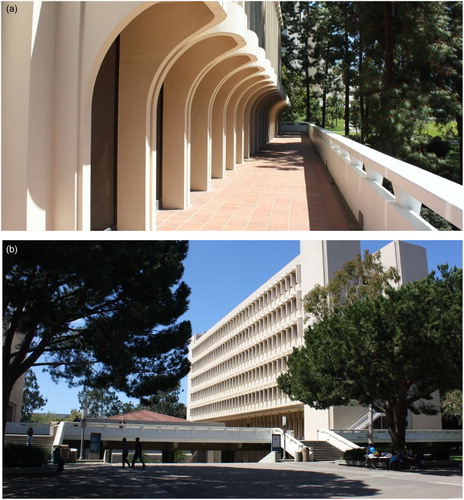

As a collective endeavour, JCE has also always been both profoundly interdisciplinary and profoundly international, with satellite homes on the West Coast of the United States, in continental Europe, and in Australia, as well as in Milton Keynes. With these changes to JCE's editorial leadership, we are becoming even more so. The production offices of the journal are now shared between the Open University in Milton Keynes and the University of California, Irvine (UCI). We feel this relationship is an apropos one. Irvine is the largest privately master-planned community in the United States, and so, like Milton Keynes, it is a product of mid-century modern urban planning (Forsyth Citation2005). Both the town and the university are embedded in the contradictory histories of Cold War development, the Southern Californian military-industrial complex, and late-twentieth-century real estate financialization. UCI was founded in 1964 in the midst of social and political upheaval on a plot of land purchased for one dollar from the Irvine Ranch, incorporated as the Irvine Company. The university's founding constituted the first step in the laying out of the new town, and the two shared an ambitious master plan by architect William Pereira, who designed, among other famous works of mid-century architecture, the original Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Geisel Library at UC San Diego, and San Francisco's Transamerica Pyramid.

Irvine and Orange County are widely seen as icons of car-centric sprawl, dull commercialism, and conservative politics: beige homes interspersed with garish strip malls and evangelical megachurches. If Milton Keynes is the butt of jokes about the proliferation of Nandos, in Irvine, folks laugh that they can measure distances in Targets. Once marketed as ‘a city for all tomorrow’, Irvine is now, received wisdom has it, the quintessential suburbia, and one of the Sunbelt shelters of Reagan Republicanism (McGirr Citation2015). And also like Milton Keynes, concrete plays an outsized role in shaping the popular imagination of the place. Unlike Milton Keynes, however, to a certain extent, the perception of Irvine's concrete countenance is an accurate one. The core of UCI's campus remains marked by Pereira's modernist vision: original buildings in the California brutalist style – elevated platforms, bright and sculptural, that appear to float among groves of shade trees, with distinctive concrete features that cast dynamic patterns of sun and shadow – spaced around a set of concentric rings, at the centre of which is a hilly circular park. In photographs of the campus taken by Ansel Adams in the mid-1960s, these buildings appear monumental and futuristic, like spaceships had landed on the newly cleared ranchland. Yet the design was not purely aesthetic; it was intended to serve as the environmental and material support for an epistemological project of interdisciplinary knowledge production (UCI was founded without departments) and, again like the Open University in Milton Keynes, a political project of public education ().

Figure 4. California brutalism on the campus of UC Irvine. Top: Langson Library. Bottom: Social Science Tower. Image credit: Tony Hoffarth, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/hoffarth/4433330505/ and https://www.flickr.com/photos/hoffarth/4434112486/.

When then-President Lyndon B. Johnson stepped out of a helicopter to dedicate the UCI campus in June 1964, he was just over a month removed from his first invocation of the so-called Great Society, which sought to set a New Deal-like agenda of public investment in infrastructure and education. He was less than a month from signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and he was already inextricably implicated in the escalation of ongoing violence in Vietnam. Johnson's dedication of UCI was also less than a decade removed from the passage of the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act. Public highway transportation and public higher education: two projects of national integration, with ramifying and often unintended effects, which stretched the limits of concrete and of the imagination of a collective future.

Within a decade or two, the modernist project that shaped Irvine's founding had begun to be associated not with its inclusive, democratic aspirations, but with the disintegration and corruption of that dream and its replacement by other ‘capitalist utopias […], from asset-based welfare to shareholder capitalism and the ownership society’ (Cooper and Konings Citation2016, p. 3). Brutalism came to feel more dystopian than utopian, a quick cut on prominent display in – just for example – the fourth Planet of the Apes movie, in which the concrete towers of UCI's School of Social Sciences featured prominently as the prison of a totalitarian state. Perhaps this cultural shift was a predictable one: the progressive projects of mid-century Euro-America fell into disrepair and disregard not simply because they fell short of their own standards of evaluation, but because – like the project of liberalism generally – their visions of equality, inclusion, and development were always defined by, and continue to be haunted by, their constitutive exclusions.

This is the deeply hopeful and deeply compromised legacy that entangles both Irvine and Milton Keynes. It is there in the architecture itself, and in efforts to trace out the architectures and infrastructures of culture and capital. While ‘concrete’, those architectures and infrastructures are far from monolithic. Indeed, as Kett and Kryzka (Citation2014) write of UCI, the institution's ‘unique situation on the Southern California “frontier” afforded exceptional possibilities for academic and institutional experimentation’. Mindful of this layered legacy, we remain nonetheless hopeful that JCE can build on the public-facing experimental and interdisciplinary histories of its two homes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Darren Umney is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Open University.

Taylor C. Nelms is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of California, Irvine and the Co-Editor in Chief of the Journal of Cultural Economy.

Dave O’Brien is The Chancellor’s Fellow in Cultural and Creative Industries at the University of Edinburgh and a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Cultural Economy. His most recent book is The Routledge Companion to Global Cultural Policy.

Fabian Muniesa, a researcher at the Centre de Sociologie de l''Innovation (Mines ParisTech), is the author of The Provoked Economy (Routledge, 2014) and the co-author of Capitalization: A Cultural Guide (Presses des Mines, 2017). He is the Chair of the Journal of Cultural Economy editorial board.

Liz Moor is a Senior Lecturer in Media and Communications at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Cultural Economy.

Liz McFall is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the Open University and Co-Editor in Chief of the Journal of Cultural Economy.

Melinda Cooper is Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Sydney and Associate Editor of the Journal of Cultural Economy.

Peter Campbell is Lecturer in Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Liverpool.

Notes

1. Of distinctively symptomatic (if not epochal) proportions is the recent confrontation between Adam Tooze and Wolfgang Streeck in the pages of the London Review of Books. For a presentation and assessment, see Muniesa (Citation2017).

2. Specifically, this commentary grows out of events held in June 2017, sponsored by JCE in partnership with the Open University Citizenship and Governance Strategic Research Area and inspired by the 50th anniversary of Milton Keynes. The main event MK of the Mind was a midsummery day of presentations, discussions, and derive, convened around Milton Keynes’ central shopping and cultural quarter. The day mapped out a broad landscape of cultural engagement between the city, the Open University, and JCE. It would not have been possible without the support of Milton Keynes Council, Milton Keynes Gallery, the Open University's Open Learn team and everybody who contributed to the proceedings: Sas Amoah, Allan Cochrane, Agnes Czaika, Joe Deville, Umut Erel, James Kneale, Simon Lee, David Moats, Gill Perry, Stephen Potter, Gillian Rose, Eva Sajovic, Anthony Spira, Katy Wheeler, and Olly Zanetti. The first circulable incarnation of this conversation was as an online essay (McFall and Umney Citation2017); its next will be as a film by London video artist Sapphire Goss.

3. See the Destination MK webpage: http://www.destinationmiltonkeynes.co.uk/About-us/UnexpectedMK.

4. CRESC had major ESRC funding between 2004 and 2014. It remains active; see https://www.cresc.ac.uk.

References

- Allen, J. and Pryke, M., 1994. The production of service space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12 (4), 453–475. doi: 10.1068/d120453

- Anderson, B., 2016. Imagined communities: reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism. Rev. ed. London: Verso.

- Banham, R., 1966. The new brutalism: ethic or aesthetic. New York: Reinhold.

- Campbell, P., Cox, T., and O’Brien, D., 2017. The social life of measurement: how methods have shaped the idea of culture in urban regeneration. Journal of Cultural Economy, 10 (1), 49–62. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2016.1248474

- Cooper, M. and Konings, M., 2016. Pragmatics of money and finance: beyond performativity and fundamental value. Journal of Cultural Economy, 9 (1), 1–4. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2015.1117516

- Cooper, M. and McFall, L., 2017. Ten years after: it’s the economy and culture, stupid! Journal of Cultural Economy, 10 (1), 1–7. doi: 10.1080/17530350.2016.1267026

- Crossick, G. and Kaszynska, P., 2016. Understanding the value of arts & culture. Swindon: AHRC.

- Dick, P.K., 1962. The man in the high castle. New York: GP Putnam and Sons.

- du Gay, P., ed., 1997. Production of culture/cultures of production. London: Sage.

- du Gay, P., et al., 1997. Doing cultural studies: The story of the Sony Walkman. London: Sage.

- du Gay, P. and Pryke, M., 2002. Introduction. In: P. du Gay and M. Pryke, eds. Cultural economy: cultural analysis and commercial life. London: Sage, 1–20.

- Forsyth, A., 2005. Reforming suburbia: The planned communities of Irvine, Columbia, and the Woodlands. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fourcade, M. and Healy, K., 2017. Seeing like a market. Socio-Economic Review, 15 (1), 9–29.

- GRECE, 1982. Pour un ‘gramscisme de droite’: actes du XVIème Colloque national du G.R.E.C.E., Palais des congrès de Versailles, 29 novembre 1981. Paris: Labyrinthe.

- Hall, S., 1960. Introducing New Left Review. New Left Review, 1 (1), 1–3.

- Hall, S., 2003. Cultural identity and diaspora. In: J.E. Braziel and A. Mannur, eds. Theorizing diaspora. Malden: Blackwell, 233–246.

- Kett, R.J. and Kryczka, A., 2014. Learning by doing at the farm: craft, science, and counterculture in modern California. Chicago, IL: Soberscove Press.

- Kitchen, R. and Hill, M., 2007. The story of the original CMK. Milton Keynes: The Living Archive.

- Loeb, Z., 2017. Statues or it didn''t happen. LibrarianShipwreck, 5 Oct. Available from: https://librarianshipwreck.wordpress.com/2017/10/05/statues-or-it-didnt-happen/ [Accessed 11 Oct 2017].

- Milton Keynes Development Corporation, 1970. The plan for Milton Keynes: volumes one and two. Wavendon: MKDC.

- McAndrew, S., 2016. The EU referendum, religion, and identity: analysing the British election study. Religion and the Public Sphere, the London School of Economics and Political Science. Available from: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/religionpublicsphere/2016/07/the-eu-referendum-religion-and-identity-analysing-the-british-election-study/ [Accessed 29 September 2017].

- McFall, L. and Umney, D., 2017. Milton Keynes is bidding to be 2023 capital of culture – it should be taken seriously. The Conversation, 31 Aug. Available from: https://theconversation.com/milton-keynes-is-bidding-to-be-2023-capital-of-culture-it-should-be-taken-seriously-81190 [Accessed 27 September].

- McGirr, L., 2015. Suburban warriors: the origins of the new American Right. Updated edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mills, C.W., 2008. The cultural apparatus. In: J.H. Summers, ed. The politics of truth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 203–212.

- Muniesa, F., 2017. Banks, nations, and vocabulary. PERCblog, 18 Apr. Available from: http://www.perc.org.uk/project_posts/banks-nations-vocabulary/ [Accessed 27 September 2017].

- Muniesa, F., et al., 2017. Capitalization: a cultural guide. Paris: Presses des Mines.

- Peck, J. and Theodore, N., 2015. Fast policy: experimental statecraft at the thresholds of neoliberalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Scott, J., 1998. Seeing like a state. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Selwood, S., 2006. A part to play? The academic contribution to the development of cultural policy in England. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 12 (1), 35–53. doi: 10.1080/10286630600613200

- Van Heur, B., 2010. Small cities and the geographical bias of creative industries research and policy. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 2 (2), 189–192. doi: 10.1080/19407963.2010.482281