ABSTRACT

The widely discussed transition to a circular economy (CE) combines a large number of approaches that imply varying degrees of change and affect institutions and actor groups. Despite this variety, the basic premise of CE is that production and consumption are connected to each other in new ways. Consumers are integral to any attempt to gear the economy toward circularity. In this article, implications for consumption work in CEs are explored based on a qualitative, experimental approach using a handbook as a cultural probe. The case is Norwegian domestic dwellers enacting activities related to CE principles. The study reveals two interconnected findings that question and raise attention to broader social dimensions of circular economic activities in households. First, the participants envisioned and enacted activities of a specific CE alternative, in which a local, community-based, and self-sufficiency vision was central. Here, resources were utilised and cascaded domestically, reducing the link to economic exchanges that reach beyond the household to reduce and close environmental resource loops. Second, the enactment of circular activities required more time and work, leading to discussions in which standard wage labour was presented as problematic because it did not leave enough time to engage in circular consumption work.

Introduction

With the crises of environmental degradation and resource depletion unfolding around the globe, it can be no doubt that the patterns of consumption in the global North are entangled in capitalist arrangements of economic and social organisations’ relationship with the natural world (Jackson Citation2006, Evans Citation2019). This has triggered critiques of consumerism (Meissner Citation2019), and those high levels of consumption have led to calls for domestic sustainability transitions (Davies et al. Citation2014), including a further critique of the economic system underpinning these realities (Hickel Citation2020). Still, the remedies for consumerism’s inherent ills are many and divergent. This article starts with understanding the economy as deeply embedded in societal structures, and not as a disconnected, autonomous realm (Polanyi Citation1944, Block Citation2007). Based on the concept of consumption work (Wheeler and Glucksmann Citation2015), this study reports empirically on changes introduced by a desire to move from domestic consumption in a linear economy to more circular forms of consumption. How resources and things circulate (Braun et al. Citation2021) becomes important for understanding this potential change.

In the literature on circular economies (CEs), the move away from so-called ‘linear’ production and consumption patterns and systems to those of ‘circular’ nature entails activities like repairing, reusing, and recycling (e.g. European Commission Citation2015, Citation2020, Ellen MacArthur Foundation Citation2013). For example, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) holds that CE is key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) (Andersen Citation2021). In a CE context, consumption is expected to be radically different from today (Ellen MacArthur Foundation Citation2013, Welch et al. Citation2017). Fuelled by oil and gas exports, a well-functioning welfare state and low social polarisation, Norway is characterised by a large middle class that is very well-off. In this context, the Norwegian answer to environmental concerns is a so-called ‘green shift’ agenda. As part of this, recently the Norwegian CE policy was outlined in a government white paper (Office of the Prime Minister Citation2019, Ministry of Climate and Environment Citation2020, Citation2021 Office of the Prime Minister Citation2019) that aims at sustaining the current paradigm of consumerism through more environmentally friendly and novel product substitution rather than shifting to different modes of consumption. Considering Norway’s high levels of consumption with an annual material consumption per capita of 44.3 tons (Circularity Gap Report Citation2020), such a restricted approach to circularity appears as deeply problematic.

The European Commission’s (Citation2015, Citation2020) efforts at transitioning to a CE say that the millions of choices made by consumers can impair or support it. Such a framing transforms consumers into policy targets (Wheeler and Glucksmann Citation2015), which implies that sustainable consumption requires a comprehensive approach that includes individual, collective, and systemic dimensions. Where the Norwegian CE strategy targets mainly businesses and industry actors to steer the transition, a more extensive approach necessarily includes individual acts of consumption and how they are embedded in broader social, economic, and cultural contexts.

In those approaches to CE transitions, which go beyond simple product substitution, citizens are encouraged to lead more resource-efficient lives with an emphasis on prolonging the lifetime of products. This comes with far-reaching consequences for all economic activity as the current ‘take-make-use-dispose’ economy, as popularised by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (Citation2013), means that the consumption of goods is cheap, accessible, and easy to discard – making space for new purchases. Such a CE is framed to move away from this rationale toward caring for and reducing environmental impacts through means of reuse, repairs, refurbishment, renting, and re-selling. Following the argument of the embeddedness of economic activity, this starts with the assumption that the choices of millions of consumers are never solely guided by price, information, or accessibility – as, for example, the EU Commission hints at in its CE action plan – but encapsulates cultural heritage, histories, social norms and values, desires, relations to others, and work-life balance. Everyday life decisions are deliberate and rational, unintentional and illogical, and they result from negotiations with individually and collectively held norms. In that way, this paper is based on the assumption that a transition to a CE can only unfold its full potential when it is about much more than sustainable innovations in the sphere of production, as it transforms the very relation between consumption and production.

Switching to a different mode of consumption demands effort and persistence from the consumer, but it also requires the right economic and systemic conditions. In this article, it is asked what happens when households commit to more circular ways of consuming, what are motivations, barriers, experiences, and potential effects on the larger economy when individual acts of consumption become more circular. Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015), who studied how consumers performed what they call consumption work, i.e., unpaid domestic work related to consumption activities, when sorting waste in their homes, showed how these acts of consumption were embedded in the organisation of labour and the overall economic system. This approach both invites the complexity of everyday life settings and maintains a perspective of embeddedness in the larger economy. Extending the scope of their work, in this article, the consequences of a circular transition of household consumption are explored. In the next part, I present the theoretical lens of the paper before introducing the methods and results, followed by the discussion and conclusion.

CE and consumption work

If CE is seen as more than mere substitution of more sustainable products or services, then consumers are expected to consume differently in a CE. After a period in which business models, systems, and services were described as central to a CE transition as companies’ inner business logic changed toward keeping value instead of discarding it, calls for empirical studies focusing on consumption in a CE context have become more frequent recently (Hobson and Lynch Citation2016, Mylan et al. Citation2016, Camacho-Otero et al. Citation2018, Camacho-Otero et al. Citation2020). Camacho-Otero et al. (Citation2020), for example, write that when developing circular products and systems, it is pivotal to consider the effort the use of such offerings requires for the consumer. Tunn (Citation2019) states that consumers compare the efforts required to consume and manage goods and services of standard offerings with the perceived efforts of the new, circular offerings.

Kathryn Wheeler and Miriam Glucksmann (Citation2015) provide the analytical point of departure for this paper with the framework of ‘consumption work.’ This research framework brings consumers into societal understandings of the division of labour (Evans Citation2017) and where consumption work means ‘all work necessary for the purchase, use, re-use, and disposal of consumption goods and services’ (Glucksmann Citation2016, p. 881). This framework resonates with a perspective in which the economic and the social are deeply embedded together. Consumption work is a precondition of use and distinct from consumption itself. Since everyday life is situated within a broader, complex sociotechnical system that influence each other – from the politics configuring work and labour organisation to imaginaries shaping political, technological, and social trajectories–and all play a role how people consume the way they do. The consumption work framework looks to make the connection between domestic consumption work, consumption, and economic organisation clearer.

This paper takes inspiration from a research agenda for consumption work in a CE (Welch Citation2019) in which the authors argue that CE visions and circular business models’ successfulness strongly depend on reconfigurations of consumption work. As Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) note, consumption work reframes the economic process on the assumption that consumers undertake work to consume, making it appropriate for interpreting dynamics of CE (Welch Citation2019). Consumption work in a CE can be returning parts to manufacturers for maintenance, or it can involve more intricate activities like acquiring the skills and knowledge necessary to complete repairs oneself (Wieser Citation2019).

Empirical and theoretical studies of consumption argue that a large amount of work is needed to be able to consume (Glucksmann Citation2009, Wheeler and Glucksmann Citation2015, Glucksmann Citation2016). The background for viewing consumption as a two folded process of working and consuming stems from sociological traditions studying the division of labour to understand large-scale transformations of the nineteenth century. A central piece within the sociology of work has, according to Glucksmann (Citation2009), not been critically re-evaluated. However, with developments within employment and work, Glucksmann writes that the increasing complexity of supply chains and restructuring of market and non-market relations change work and reshape links between workers and non-workers, i.e. consumers. Munro (Citation2021) similarly discusses the links between the household, the economy, and the state, with emphasis on recycling, in which the unwaged work of households’ waste sorting advances capitalism’s crisis-prone dynamic of overaccumulation, as well as waste sorting as an instance of work transfer from industry to households. O’Neill (Citation2019) writes that the rise of the global waste economy derives from economic growth and industrialisation in the twentieth century, which transformed the relationship between waste and resources in the industrialised world. But as Max Liboiron (Citation2021) notes, resources flow from the South and into the North, where waste accumulates and is later returned, thus polluting communities and the environment in the South. This is according to Liboiron colonialism. This point may tie into how large resource and waste loops are thought of. Should resources and waste be kept in local or global loops?

Bauman (Citation1998) wrote that in the global North, there was a shift from work as the source of identity toward greater preoccupations with consumption and lifestyles instead. In classical understandings of the division of labour, all work is completed prior to reaching the end-user, in which emphasis was on the technical skills, tasks, and competencies related to paid employment (Wheeler and Glucksmann Citation2015). They exemplify this by describing that furniture used to be produced and assembled in the production process, while the rise of ‘Ikea-isation’ shows that an important aspect of the production of furniture shifts across socio-economic boundaries and into the domestic to be undertaken by diligent citizens. In this way, consumption can be defined as the result of various types of consumption work.

The main point in consumption work is that work does not cease to exist despite its movement across such boundaries, but continues with different sets of skills, tasks, and competencies. As I shall argue in the coming chapters, work is also kept within the domestic and is not in all instances transferred beyond the household. The difference is that this shift of labour to the consumer is unpaid. Both of Wheeler and Glucksmann’s work (2009, Citation2013, Wheeler and Glucksmann Citation2013) aim to reconceptualise the division of labour to be able to understand recent and current transformations taking place in not just the global North, but the South, too. Their framework is about acknowledging the unconscious and taken-for-granted work people do, and that these are economically crucial to the wider economic system. Glucksmann (Citation2013) reflects that daily activities may be presumed unimportant and not experienced as work, but could be classified as such when reviewing their significance for economic activity.

Connecting this to the moral economies of households, Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) draw on a comparative, empirical case of waste sorting in Sweden and England, which follows a newer tradition of transferring tasks from producers and retailers to consumers and users. Their cases show that cutting production and labour costs is important in this regard, which affects the level of labour needed from the consumer to be able to consume. This theoretical lens offers a way to study not only how people consume, but it offers a vocabulary to analyse how consumption and consumption work relates to a broader sociotechnical system of production, provision, use, and post-use. With this framework and study of domestic consumption transitions, the following sections outline the methods used and the results.

Methods

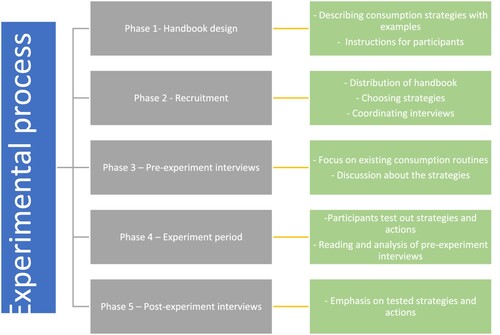

With the domestic brought into focus in relation to the public, both are subjected to more frequent inquiries, experimentations, and tests (Marres and Stark Citation2020). The data presented in this paper derives from an action-research oriented study in which the aim was to study three sustainable consumption strategies described by Vittersø and Strandbakken (Citation2016) – product substitution, reorganizing consumption, and consumption reduction – and their relation to more circular forms of household consumption. The focus was to research the challenges, opportunities, and level of work needed to consume in Trøndelag’s largest city, Trondheim, and the rural, cultural hub of Røros. The empirical study at its core consisted of a one-month long experiment in which households tested acts of sustainable consumption. The study can be described as consisting of five phases (see ). In phase one, various consumption strategies were used as a template for designing a handbookFootnote1 for the participants. The handbook found inspiration from the ‘cultural probes’ of Gaver et al. (Citation1999), which are ‘collections of evocative tasks meant to elicit inspirational responses from people – not so much comprehensive information about them, but fragmentary clues about their lives and thoughts’ (Gaver Citation2004, p. 53). The handbook included an outline of the strategies, selected examples relating to each strategy, and a set of appendices of additional information and suggestions for actions. The participants chose freely among the strategies, and in that way the handbook was used as a probe to trigger reflections about their own consumption pertaining to resource use and management.

Recruitment comprised phase two (see ). The handbook was distributed to colleagues who forwarded it to their networks on Facebook. Those interested contacted me by e-mail by writing about their motivation for participation and general information, such as age and location. They indicated very briefly which changes they were interested in. The first round of semi-structured interviews took place in their homes. I inquired about their consumption habits and routines, and their consumption related to resource use in the production and consumption of everyday commodities. The goal was to establish a connection with the participants, gain insights into their thinking, and establish a point of reference for the final round of interviews. This first round was moreover a relaxed conversation about the handbook, what they wanted to test out, and practicalities like documenting the experiment with pictures and making notes. They were asked to reflect on the handbook’s content and summarise what they aimed to test out. In phase four, the participants partook in the experiment and no contact was made except for scheduling the follow-up interviews for phase five. These took place shortly after the experiment ended and was a reflective discussion of their experiences.

Table 1. Participant overview.

The participants are given fictive, Norse names to ensure privacy protection. The experimental process resulted in 14 semi-structured interviews (seven pre and seven post interviews). In analysing the transcriptions of the pre-experiment interviews, I took notes and summarised their insights by focusing closely on their descriptions of their consumption, thoughts about the environment and resource use, as well as captured their thoughts on the probe. Furthermore, it was relevant in getting an overview of their consumption related to their every day- and work-life relations. In the second reading of the transcripts, I identified themes related to consumption, everyday life, and work, which ended in a thematic description looking at sections of interview transcriptions relating to these themes. Categories such as reuse, repairs, reduce, food, waste management, time management, work, Covid-19, organisation, leisure, environment, knowledge, learning, practices, children, family, and sharing were identified.

For the post-experiment interviews, I took a similar approach where I collected examples of what they tested out, how this was experienced, and elements relating to the feasibility of establishing CE activities as a default in the future. I grouped occurring topics in a table and linked the relevant quotes to them. I emphasised capturing descriptions of processes leading to consumption, such as sorting waste fractions, acquiring knowledge to choose products, and whether things would need to be repaired.

The overall impression was that the handbook, or probe, served more as an inspirational guide to narrow the focus of the experiment for the participants. Their choices seemed to be internally motivated by different topics they engage with on a daily basis, as well as by what is feasible to follow through with time-wise through hectic everyday lives. With that said, in Norway and elsewhere there is a larger focus on product-life extension activities such as repairs, recycling, and reuse that cannot be ignored. People are more frequently exposed to such ideas of circularity and issues pertaining to global warming through the media landscape, but the actual performance of elements of CE in everyday life is rarely tested or studied. This experimental approach does this by considering the increased political push and societal awareness of CE, coupled with a handbook that is operationalised based on elements of CE and types of sustainable consumption strategies. The suggestions in the handbook align partly with this increased CE focus in the media, but its specific contribution is the overview of services and suggestions that households can implement that are part of a local and national turn toward more sustainable services and activities. The experiment, then, served as a final push for people to try out changes they had contemplated for a long time. Whether these activities would have been undertaken without my influence is difficult to discern.

Limitations and COVID-19

The experiments took place during a global and local pandemic situation. I expected from the beginning of designing the experiment that I likely would meet resistance in the recruitment phase. I had 10 respondents, of which seven committed. The fear of infection may have limited willingness to participate. The qualitative nature of the study and the sample size is not reflective of the population of this region. A survey study could potentially reach broader, but the detailed discussions of each participant's consumption would be insufficient. Due to the temporal dimension of the study, it would be more difficult to coordinate the testing of the strategies through before-after surveys. My position as a researcher is actively involved in creating the contents of the handbook as a cultural probe, but also through conducting the interviews and discussions. A central tenet in action research is the co-production with the participants where ideas are exchanged which prompt unplanned topics. In such a study, it is challenging to be a neutral observer. Despite this, I hold that a mutual discussion about the topics addressed here creates better knowledge than without this joint involvement.

Results

The following presentation and analysis of the data topically relates to Wheeler and Glucksmann’s (Citation2015) recycling and household sorting consumption work but extends it to involve so-called ‘circular’ activities of repairing, sharing, and creating shorter and more localised waste loops. With these circular activities brings the acquisition of centralized knowledge. Together, the cases aim to describe the work needed to engage with sustainable consumption, including reflections of the informants around this work. The participants in this study were prior to, during, and after the experiment mentally and physically involved with the idea and performance of sorting household wastes. Wheeler and Glucksmann’s (Citation2015) detailed descriptions of the significant labour of sorting waste fragments post-purchase where individuals function as ‘suppliers,’ their homes as ‘warehouses,’ and the waste fragments are ‘distributed’ beyond the confines of the domestic sphere. This is very much the case for the participants in the experiment as well. The participants could choose changes that were relevant for them. Although some chose one main strategy, all participants engaged in a broad variety of new activities.

As this study focuses on change, the pre-interviews provided a starting point for understanding how they consume. Each household shared similarities such as being interested in environmental and climate aspects of consumption, they practiced repairs, reuse, and redesign from time to time, and they sorted their waste fractions diligently. They also chose products that were time saving due to the busy schedules of daily life. They enacted predominantly what CE proponents describe as a linear management of resources, in which products were acquired, used, and discarded as waste. In most cases, the discarded products were transferred out of the household. Waste is a central topic in CE literature and policy and it is especially relevant for domestic consumption (work). The findings show that even prior to the experiment, but much more during and after the experiment, there were activities of using particularly food waste for domestic use, like composting and gardening. In the next section (4.1), excerpts of the participants’ experiences of changing their consumption and descriptions of how resources flow both beyond and within the domestic economy are presented. Observations regarding circular consumption activities that go beyond the focus on waste management – particularly repairs – are collected in the second part of the empirical observations (4.2).

Composting and gardening as circular activities

The participants organise their waste, as most Norwegians do, under the sink in the kitchen or in a cupboard, which they later distribute to larger rubbish bins outside the house. Glass and metal fractions must often be brought further away to designated areas where there are collection stations. There is a great variety of how waste is organised depending on the neighbourhood, municipality, and available infrastructure. Residents pay a renovation tax which varies from where and how one lives as well as how big the waste collection bins are. The sorted household waste is then collected by the local waste management operators, which is municipally owned, and brought in for further sorting and management. The citizens of Trondheim and Røros, where the participants of this study live, are bound to sort their waste fractions according to the local, administrative regulations (Renovation regulation Citation2019, Citation2020). Despite this official technicality, there is a long-standing tradition and culture for sorting out household waste, which is not necessarily due to such regulations per se, but warranted by institutionalised practices and skills transferred from generation to generation. A generally high level of trust toward public institutions coupled with the cultural embeddedness of waste sorting makes this activity a social norm. There is thus a public expectation to sort waste at the household level, but there is also a type of cultural memory informing this activity.

Food waste is not sorted separately in Trondheim municipality yet, but it has been since 2020 in the Røros municipality. There are alternative ways of utilising this waste fraction. The households of Astrid, Birk, Ulf, and Sigrid used warm and cold composting prior to the experiment, which is placed in their gardens. Not all waste fractions were transferred out to other socio-economic processes but were kept for personal use. Astrid, for instance, spurred by a long-standing desire to make her garden produce more succulent vegetables, took advantage of the experiment and got herself a bokashi (fermented organic material)Footnote2 set. ‘I am looking forward to the spring so I can use better soil. My neighbour told me that she had used bokashi.’ She realised during a conversation with her neighbour that: ‘oh dear, that is why you have such large kale. Mine were so thin.’ Her introduction of bokashi, with an economic stimulus up to 1000 NOK from the local government as a waste-reducing measure, meant expanding the waste system by adding two new waste containers. She throws fresh food waste in one and then into a second one, which is where the actual fermentation process takes place. The contents of the first bin are transferred manually to the second bin, where the former sits in a cupboard under the kitchen and the latter in the entryway, a place that is not a traditional space to store waste. For Astrid, this meant, ‘a mental readjustment that I need to look out for every time I opened the cupboard. I am awfully close to throwing it (the food waste) in the old (residual waste) bin,’ which is how it was organised pre-experiment. As the bokashi bin ideally should not be frequently opened, she had to temporarily store the waste elsewhere.

Here, the ‘warehouse’ metaphor of Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) comes into play, as the secondary container becomes an intermediary warehouse between two processes of cooking and fermentation. Old habits collide with new in finding the ideal way to manage food waste but also in satisfying the biological aspect of the fermentation process. The result is less residual waste and more nutritious gardening soil, but it has also led her to ‘become more conscious about my own consumption.’ The new process of sorting out food waste serves a very concrete purpose of enabling the to growth of more luscious vegetables in the future, which means that she must spend more time organising food waste to become raw ingredients in another process – a CE cornerstone. Optimal fermentation does not happen on its own, but demands inputs of knowledge, effort, time, space, energy, and composting sprinkle for activating fermentation. Despite that, the new system brings a certain script into play. It meets a personal preference of how to use and place it in her home. This way of organising food waste resonates with her history of farming when she was younger at her Dad’s farm: ‘My brother and I come from and grew up on a farm. Our parents first grew vegetables and then flowers, so we probably have it in our genes, in our fingers, to be self-sufficient.’ She wishes to be self-sufficient in creating soil instead of buying it, which may later ensure greater food independence. This example points to a personal desire to reduce the need to buy food at the store, which also reduces the generation and accumulation of residual and plastic waste. Being self-sufficient is something that resonates with her.

Astrid: It means a lot. I think more of us must go in that direction – to grow more oneself.

Interviewer: Can you explain a bit further why you think being self-sufficient is important?

Astrid: Firstly, it is that you have more control over the products and the content. I also think that everything is uncertain going forward that it is probably smart to have a certain level of self-sufficiency.

Astrid, Frida and Harald, Birk, Hilda, Ulf, and Sigrid have all tried to grow fruits and/or vegetables with varying luck, and the idea of self-sufficiency seems to be strongly grounded in especially Birk and Ulf’s descriptions, which also have different motivational roots. Birk describes elements of self-sufficiency in relation to personal experiences:

I have made a vegetable garden which we will begin with next summer, so there’s expectations for something. I also get some potatoes from my father […] I could, of course, extend this to pick strawberries and cowberries, but it’s about time – it takes a long time.

The sustainability issue is explicated further in Birk’s following reflection:

I believe that [allotments] must be part of the sustainable solution in countries that have space for it. Think of Norway, how many square kilometres of lawns we have, which we only mow, really, and don’t use. To put it bluntly, this [space] should be regulated by law so all must use a certain share of their lawn to cultivate, and then we could have public gardeners coming to help people get started. That would be part of a national voluntary communal work for local production of food. […] However, it opposes this efficiency society which has been the main deal since the Second World War. […] It demands a “slower” mindset to make things more sustainable. […] It is an idealised thought, this, but to strive for it will do good for the future of food production. […] The “think globally act locally” thing … it is actually a lot of things you can do locally which actually is moved away because it is cheaper to do things in China or other countries.

Keeping labour and resources within local communities is understood to be important for future sustainability, where partial self-sufficiency is key. Ulf shares an interest in cultivating and producing home-grown food. He is also the one with the largest garden and greatest harvest of the participants. Warm and cold composting has become routine, and the nutritious soil is laid upon the land where he reaps the rewards. Ulf, as Birk and Astrid, is likewise affected by familiar relations and histories informing current actions.

I have home composting, so all food waste goes into a container under the sink here, and once in a while I need to empty it […] It is a warm compost behind the garage […] Principally, food waste goes out to the compost, meaning that it creates rather small amounts of residual waste. […] We grow potatoes ourselves […] and I put the compost onto the soil. Then the nutrients go back into the potato. […] Last year, I harvested 25 kg of potatoes. […] My father made (the compost) […] He liked garden work and it gives better soil. Also, he saved parts of the renovation tax.

Here, we see an example of how Ulf acts as a distributor and manager of waste, and how the cupboard under the sink and compost areas in the garden are temporary ‘warehouses’ for the resources. When food waste and/or garden wastes are moved from the domestic warehouses, like containers for fermentation or composting to the soil, these are examples of how domestic waste flows are used to advance self-reliance and circular activities. The cases of Astrid and Ulf highlight especially all the work needed to complete the circle from waste to resource to food. In other words, instead of shifting these resources to external entities, such as the waste management company, they are kept within the domestic economy of internal feedback loops. The activity of cultivating, growing, and harvesting means engaging in activities considered to be circular, where prior knowledge coupled with learning by doing make up these activities.

Repair and reflections on time and critiques of growth

Many participants were already practising repairs, but the cultural probe made this a more central activity. The following excerpts focus on various experiences with repair activities and the time and knowledge needed to prolong product lifetimes. They also tie into temporal reflections and interpretations of contemporary society. The first example highlights a mundane dishwasher issue:

[…] the lower trail [rack of the dishwasher] has wheels, but the majority got worn out, some were falling off and the trail would not be held and will touch the bottom of the dishwasher, causing it not to work properly. Also, the basket holding cutlery had big holes, the cutlery went through, and it will make the trail not be able to slide open or closed. This was a pain. It is an IKEA dishwasher, and we did not find spare parts in IKEA, so we thought we were lost here and doomed to change the dishwasher. We got the option to replace it with another dishwasher (a rather new one from relatives), but I thought it was stupid to change the whole dishwasher because of some plastic wheels and a plastic basket with holes. The trick was to google the serial number and it happened to be an Electrolux machine, probably a brand for IKEA since it does not say Electrolux anywhere. Anyway, I bought the spare parts from Electrolux.no. (They were delivered at the post office) and now everything is working perfectly. To think we were considering changing the dishwasher due to a few missing parts feels a bit unnecessary, but of course it helped to find the parts. (Frida and Harald)

In retrospect, this process started with them almost giving up: ‘[…] in the beginning we kind of gave up, because it’s an IKEA thing, and we couldn’t find the repair parts. […] It takes a little bit more time, but it’s not any ambivalence there, I think.’ This reflection of repairing their dishwasher contains many elements. A first point is the issue of it hindering daily cleaning chores. It shows that the use of the dishwasher and undertaking related tasks are not solely confined to the domestic, but extends beyond to the technical design of the dishwasher, its manufacturer, provider, product information, and the postal service for delivery. Thus, a complex interdependency between domestic and external actors ultimately consumes energy and water for completing trivial tasks in the home. The family considered substituting it, but after consideration they felt that ‘would be so stupid.’ In repairing the dishwasher, they realised the following:

Harald: […] the dishwasher has several programs. And I think, I’m not sure, but I think some people use the one that makes the dishes cleanest, and that is the one with the warmest and longer duration. And then I looked into the user manual.

Frida: We’ve never used that before.

Harald: And it actually explained how much water and energy the different programs consumes. And it happens to be the one we were using uses like 27 litres of water.

Frida: I think also now we think that we should do that with more things. Maybe the washing machine. We should not just press the default button.

Harald: Exactly. It would be interesting to see how much it’s possible to save in all these things. That was very nice. […] I think with a little bit of effort you realize you can save much more. I think that was a nice [lesson].

Frida: I find it very important to show the kids it’s possible to repair.

Astrid described a situation where she looked to outsource the repair service needed for her phone – a sound issue. She first went to a well-known telephone operator store but was told that this would be difficult to repair. Then, she went to a repair shop nearby where she recalled seeing ‘a nerd with long hair’ and thought to herself humorously that ‘this is the right chap.' He understood straight away what was wrong, and he fixed the phone in 20 minutes cheaply. Understanding where to go and knowing that the process is transparent is important for choosing repairs over buying new. For Inga, repairing something is not always a clear-cut option. She described a hesitance toward repairing electronics because of the unknown price and where to repair such items.

Harald noted the difficulty in on finding time to do circular activities: ‘I think time is where we are more pressed […] Instead of doing it in the store, I’m doing it here, and in the end, it takes more time than I thought.’ When asked how they could organise everyday life differently to create more time, they responded with ‘I’m sure that one option would be to actually work less, I think […] I don’t think I can take extra hours from the duties at home, because that is not something you can avoid.’ Birk echoed this by describing that ‘we have such economic freedom that you must create frameworks and demands, so to have a six-hour workday must be maximum if you are to have time [for repair work].’ To be able to consume differently and put in more work to consume indicates a different organisation of the labour force and how it organises workers’ time. The participants say that such activities like prioritizing time to compost, cultivate, and repair, ought to be meaningful. If not, those activities would be difficult to implement.

During the post-experiment interview, Birk took the position against the race for green growth, as popularised in policies and industries. He said: ‘I don’t believe much in green growth as it is a greenwashing of the same efficiency society, we’ve had all along, or been striving for the last 50 years.’ That stuff is supposed to move quicker and to call it green growth […] I don’t believe this is a solution to anything.’ Instead, to reach a society of circularity ‘you must be very conscious about it […] and there is also this slow mindset that you must have time to invest in what is sustainable.’ Time is something other participants mentioned was lacking in their being able to reduce their material intensity. Frida and Harald noted that ‘time is where we are more pressed […] Instead of doing it in the store, I’m doing it here, and in the end, it takes more time than I thought.’ When asked how they could organise to free up more time, they responded with ‘one option would be to actually work less […] I don’t think I can take extra hours from the duties at home, because that is not something you can avoid.’ Birk reflected further on the social organisation of food production and interrelated topics on contemporary developments:

it should be regulated by law that all must allocate part of their garden for cultivation, and then public gardeners would help to get started, which would be part of a national, voluntary communal work, and also other forms of allotment gardens. […] You can cut out much of the industrialised and imported agriculture that demands fertilisers, pesticides, and monocultures, and favour local production instead. […] However, it opposes the efficiency society […], so it demands a different mindset to do things more sustainably. […] This is an idealised thought, but to strive toward this would do good for the future of food production. […] The repair and maintenance mindset to be able to produce products that last and can be repaired. Imagine, it demands that you maintain traditional professions, and this isn’t romanticising. Carpenters make furniture by hand, which is quality of life in its own right, and then people get quality products, which can be repaired.

Discussion

This section fleshes out the implications of the foregoing activities performed by the households against overarching trends in sustainability and economic discourses.

An alternative CE

The presented cases relate thematically to the CE discourses of wastes as resources and product lifetime in the EU and Norway (EU Commission Citation2015, Citation2020, Ministry of Climate and Environment Citation2017, Trondheim municipality Citation2017, Citation2019). Today, food waste is not separately sorted, but discarded with residual waste, which the local waste company collects and manages for further transport, recovery, and/or incineration. The division of labour related to the economic process of waste management takes on large amounts of household residual wastes, but with joint economic support from the local government and the waste management company, citizens have the non-obvious option of reducing food waste fractions in the residual waste bins, thus reducing the workload of the technical division despite food waste not being sorted out here.

The examples of food waste sorting, composting, transporting, and gardening relate to CE discourses of utilising resources better, where waste fragments shift between the domestic and external resource loops as well as the division of labour. They also require several instances of work. Here, we see how food and garden waste fragments move from various storages in the form of bins and different composting and fermentation systems, which is again returned to the soil as nutrients. This process continues in loops between human, biological, and infrastructural actors. Waste fractions are redistributed for personal means with the global in mind. Where Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) describe how waste fractions move beyond the household, in this study we see the opposite regarding food waste. Astrid, Birk, and Ulf use waste for higher quality cultivation and food production, with the aim of being more self-reliant. In cascading such resource loops domestically, work shifts from the public/private management to the domestic realm undertaken by its dwellers. As Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) reveal in their waste management cases in Sweden and England, the bokashi case highlights a similar aspect in which the local government and waste company seek to shift labour to the citizens to reach EU waste goals. It even shows that a product-substituting alternative means more work to be able to live more circularly, and environmentally friendlier. Organising it this way demands more space and time to do so, but it leads to fulfilling the participants’ long-term goals of being more self-sufficient, which tightly links to ideas of global and local sustainability.

These insights point to the domestic composting and food production, however small the quantity currently may be, over time reducing the purchase frequency which minimises the acquisition of plastic packaging that must be managed and distributed to external value chains that are high-energy demanding. The idea extrapolated here is to slow and narrow the resource loops and confine them as much as possible to the domestic economy. Wastes and their value shift between different socio-spatial realms in traditional waste management (O’Neill Citation2019), but in the cases described here, we see that some participants want to maintain that value domestically. By retaining the value like this, the workload increases for the consumer, despite that it is not necessarily experienced as such. But in mainstream CE discourses, waste is a critical input, thus relying on continuous waste streams to feed into new products or processes that could ensure that growth paradigms are upheld.

As we have seen, this move toward self-reliance is not accidental. Birk emphasises in his descriptions an idealistic future organisation of a domestic/local variant of food production to reduce the need for energy and resource intensive industrialised systems and transportation. Astrid and Ulf support this idea of localising either individually and/or in a cooperative to reduce consumption of energy and resources. Together, they perform parts of an envisioned future which is rooted in their personal past and perceptions of what sustainability is. Here, circular activities are performed in a synergy of global policies of waste reduction, personal histories, values, interests, and perceptions of future sustainability. Such envisioning reveals a reliance on past reservoirs of knowledge and experience in informing the sustainable choices in this experiment, which is also informed by how the future is perceived in relation to the environment (Korsunova et al. Citation2020). This also resonates with a particular vision of circularity that takes inspiration from how people consumed in the aftermath of the Second World War (Boye Citation2019). Wallenborn and Wilhite (Citation2014, p. 58) capture what several of the participants in this experiment described – that past experiences and histories inform and shape how they perceive an ideal way of living in which the body is a ‘repository of past experiences, both individual and collective, and as such, affected by social relations and cultural learning. The body is thus not only the site of action, but also of dispositions for future actions.'

The food waste sorting, composting, and gardening activities are part of an envisioning and enactment of a more specific CE alternative that breaks with mainstream CE discourses like that of the performance economy (Stahel Citation2010) in which activities, such as extending product lifetime, is outsourced and performed by services. In contrast, the ideas of a local community-based and self-sufficient production and consumption are central values where resources are utilised and cascaded domestically rather than beyond the household to reduce and close environmental resource loops. Astrid’s memory of her father’s farm is in this respect informative, as it points to a very different way of organising the economy. It is more self-sufficient and localised than the average household, which relies on products from external sources. Although the participants did not perform any circular activities as a group, they shared similar ideas of what sustainability is and how it can be achieved through creating a community feeling where resources are managed locally. In Wheeler and Glucksmann’s (Citation2015) study, consumption work in waste sorting is performed individually, as do the participants of this study. However, their common views of circularity point to the fact that consumption work may be shared for a collective good. This means that they envision a rather different future that breaks with green growth agendas and technology development as the main driver for change. In a way, the participants question the sincerity of such agendas and reveal scepticism towards them by envisioning their own. The next main point ties into this particular CE vision and related consumption work.

Time as a resource for sustainable consumption

The alternative CE discussed above connects the amount of work needed to consume and produce in more circular ways. The cases of repair activities, where participants reflect about reducing their work hours to be able free up time to implement further circular activities, resonates with previous literature on work, time, and consumption. For example, Pullinger (Citation2014) states that under the correct circumstances, a reduction of working hours may play an important part in a sustainable economy. Despite the fact that more empirical studies on the effects of work hours reduction are needed and under-researched (Rau et al. Citation2014), Schor (Citation2005) raises the larger question of whether a competitive market economy and scientific and technological breakthroughs are sufficient to achieve sustainability. Already in the current market-based organisation of work, more and more service tasks are transferred to the consumer, e.g. in-home banking, thus changing the dynamics of consumption. Similarly, implementing circular activities like repairing and keeping food waste domestically requires even more time to complete. This does not mean that this additional time is experienced as negative, it is rather welcomed by my informants. What is described, however, is that important economic parameters, such as the standard amount of working hours, would have to change to be able to lead a truly sustainable lifestyle.

The findings from this study reveal how the participants in many instances break with concurrent political aims of continued economic expansion through green growth and product substitution. The consumption and organisation of the economy envisioned by the participants link to a perspective in which the social and economic are more deeply embedded, and where reciprocity and care are fundamental values in creating a sustainable society. Frida said that it is important to show their children that it is possible to repair. This sense of responsibility in prolonging product lifetime (e.g. Evans Citation2005) shows a desire to make the younger generations care for their possessions. Responsibility is not solely in contexts of CE afforded the citizen-consumer of a service or good, but producers are increasingly mentioned in relation to producer-responsibility schemes. This follows a line of reasoning that a polluter pays as well as takes responsibility for the waste generation. Offering spare parts to ensure product longevity is thus a way to share the responsibility of a product with its user. Wieser (Citation2019) writes that such examples of provisioning require significant coordination work on the consumer's part. This shows that reorganising consumption entails a compromising path where consumers put in more work to prolong product lifetime, but that it does not happen separately. The work highlighted in this case points to a sharing of responsibility between the domestic and manufacturer to ensure lifetime extension of electrical appliances.

The CE framework highlights that a prerequisite for consumption is work. In traditional waste systems, wastes are transferred beyond the household into a large market and industry. It requires coordination between domestic and external actors to make this transfer. In this study, this is also still the case, but circular activities like composting and bokashi fermentation require an internal reorganisation of practices that entails more work on the part of the citizen-consumer. Based on the findings of this study, a turn to a more circular consumption pattern is likely to mean that the average time spent on preparing for consumption will increase. This will then happen either through increased outsourcing of services like repairs from the household, or through retaining responsibility at the individual level. Either way, this increase will have further implications for the organisation of consumption and everyday life.

Conclusion

Connected to their efforts to turn deeply ingrained consumption patterns into a more circular direction, the participants revealed that they engaged in envisioning and enacting a more specific and alternative CE that links to ideas of a local, community-based, and self-sufficient mindset that – if fully realised – represent a different way of organising labour. Building on the consumption work framework, the activities and reflections of the participants in this study link to the economy in ways that move performing work within the domestic sphere. The participants take more responsibility to manage their own waste and their appliances themselves. In this way, artifacts and particularly food waste remain for longer periods of time within the household.

The findings reveal how the abstract opposition between linear and CE is performed by the participants in this study as an opposition between dependence on (often global) flows of goods on the one side and self-reliance on the other, and between work performed outside the home to earn a living and inside the home to engage in sustainable activities – making this connection to larger systems that govern and shape consumption. In experimenting with their everyday lives, the participants show how their experiences with circular activities affect perceptions of spaces and times of production and consumption and the management of these resources. It taps into how the economy is geared: the current efficiency and science and technology-centred emphasis of the neo-liberal market economy, and how working hours play more important roles in the decisions informing consumption. The households embody and enact repositories of knowledge and histories of the past in constant negotiation with the present and the future. In these temporal connections, it becomes visible that they also link directly with international political goals of circularity, local socio-technical- and economic systems of production, provisioning, and post-use.

On the background of the discussion and the findings, it would be instructive to widen consumption debates to include how work life and working hours affect different types of consumption. This paper contributes to and extends the original scope of Wheeler and Glucksmann (Citation2015) by including specific CE activities of repairing and the narrower focus on food waste management. In addition, the paper brings into focus that social and cultural aspects, like people’s histories, play an important role in shaping visions of desired consumption. These aspects are for the most part missing in much of current policies regarding CEs, most notably in the Norwegian national strategy for a CE where consumers do not even appear to have a role in circular transitions, but also in EU policies in which still the image of rational consumers dominates. Against this background, it is advisable for practitioners and policy makers to connect environmental consumption choices with how people understand their work-life and local opportunities of action. The study shows that if time is to be made available to shift consumption, governments must consider how work is organised. If people do not have opportunities to alter their consumption, large sustainability potentials of circular transitions remain untapped. Making further connections between everyday life, work-life, and policies by focusing on time management would be an important avenue for future consumption research based on this paper’s findings, particularly in the context of CE transitions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Edward Sutcliffe

Thomas Edward Sutcliffe is a PhD candidate at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). His current research is on the topic of circular economy with particular emphasis on domestic consumption and policy implementation, and activities related to the circular economy.

Notes

1 Available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6384495

2 ‘Bokashi’, of Japanese meaning ‘fermented organic material’ is a composting system for changing food waste into a soil additive.

References

- Andersen, I., 2021. Circularity to advance sustainable development. United Nations Environment Programme. Available at: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/circularity-advance-sustainable-development[Accessed 31 August 2021].

- Bauman, Z., 1998. Work, consumerism and the new poor. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Block, F, 2007. Understanding the diverging trajectories of the United States and Western Europe: A neo-polanyian analysis. Politics & Society, 35 (1), 3–33.

- Boye, E. (2019). Sirkulær framtid – om skiftet fra lineær til sirkulær økonomi. Oslo: Framtiden i våre hender (FIVH).

- Braun, V., et al., 2021. The mutability of economic things. Journal of Cultural Economy, 14 (3), 271–279. doi:10.1080/17530350.2021.1911829.

- Camacho-Otero, J., Boks, C., and Pettersen, I. N, 2018. Consumption in the circular economy: A literature review. Sustainability, 10 (8), 1–25. Article no. 2758. doi:10.3390/su10082758.

- Camacho-Otero, J., et al., 2020. Consumers in the circular economy. In: M. Brandão, D. Lazarevic, and G. Finnveden, eds. Handbook of the circular economy. Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, 74–87.

- Circularity Gap Report, 2020. The Circularity Gap Report Norway. Closing the Circularity Gap in Norway. Available at: https://www.circularnorway.no/gap-report[Accessed 20 January 2021].

- Davies, A. R., Fahy, F., and Rau, H., 2014. Challenging consumption: Pathways to a more sustainable future. London: Routledge.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Available at: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen- MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf[Accessed 29 January 2021].

- European Commission, 2015. Closing the Loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0614[Accessed 20 January 2021].

- European Commission, 2020. A new Circular Economy Action Plan. For a cleaner and more competitive Europe. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0098[Accessed 20 January 2021].

- Evans, D., 2017. Household recycling and consumption work: social and moral economies, by Kathryn Wheeler and Miriam Glucksmann. Journal of Cultural Economy, 10 (4), 415–417. doi:10.1080/17530350.2017.1323314.

- Evans, D., 2019. What is consumption, where has it been going, and does it still matter? The Sociological Review, 67 (3), 499–517. doi:10.1177/2F0038026118764028.

- Evans, S., 2005. Consumer Influence on Product Life: An Exploratory Study (PhD thesis). Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield.

- Gaver, B., Dunne, T., and Pacenti, E., 1999. Design: cultural probes. Interactions, 6 (1), 21–29. doi:10.1145/291224.291235.

- Gaver, W. W., et al., 2004. Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. Interactions, 11 (5), 53–56. https://interactions.acm.org/archive/view/september-october-2004/cultural-probes-and-the-value-of-uncertainty1.

- Glucksmann, M. A., 2009. Formations, connections and divisions of labour. Sociology, 43 (5), 878–895. doi:10.1177/0038038509340727.

- Glucksmann, M., 2013. Working to consume: consumers as the missing link in the division of labour. Cresi working paper. Essex University. http://repository.essex.ac.uk/7538/1/CWP-2013-03.pdf.

- Glucksmann, M., 2016. Completing and complementing: The work of consumers in the division of labour. Sociology, 50 (5), 878–895. doi:10.1177/0038038516649553.

- Hickel, J., 2020. Less is more. How degrowth will save the world. London: Windmill Books.

- Hobson, K., and Lynch, N., 2016. Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures, 82, 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.012.

- Jackson, T., 2006. Consuming paradise? towards a social and cultural psychology of sustainable consumption. In: T Jackson, ed. The Earthscan reader in sustainable consumption. London: Earthscan, 367–395.

- Korsunova, A., Horn, S., and Vainio, A., 2020. Understanding circular economy in everyday life: perceptions of young adults in the Finnish context. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 26, 759–769. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2020.12.038.

- Liboiron, M., 2021. Pollution is colonialism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Marres, N., and Stark, D., 2020. Put to the test: For a new sociology of testing. The British Journal of Sociology, 71 (3), 423–443. doi:10.1111/1468-4446.12746.

- Meissner, M., 2019. Against accumulation: lifestyle minimalism, de-growth and the present post-ecological condition. Journal of Cultural Economy, 12 (3), 185–200. doi:10.1080/17530350.2019.1570962.

- Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2017. Avfall som ressurs– avfallspolitikk og sirkulær økonomi (Meld. St. 45 2016-2017). (Waste as resource – waste politics and circular economy (White paper)). Ministry of Climate and Environment. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-45-20162017/id2558274/[Accessed 20 January 2021].

- Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020. Det grønne skiftet i Norge. Ministry of Climate and Environment. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/klima- og-miljo/klima/innsiktsartikler-klima/gront-skifte/id2076832/[Accessed 25 January 2021].

- Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021. Nasjonal strategi for en grønn, sirkulær økonomi. (National strategy for a green, circular economy). Ministry of Climate and Environment. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nasjonal-strategi-for-ein-gron-sirkular-okonomi/id2861253/ [Accessed 15 December 2021].

- Munro, K., 2021. Overaccumulation, Crisis, and the contradictions of household waste sorting. Capital & Class, 36 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1177/2F03098168211029004.

- Mylan, J., Holmes, H., and Paddock, J., 2016. Re-introducing consumption to the ‘circular economy’: A sociotechnical analysis of domestic food provisioning. Sustainability, 8, 1–14. doi:10.3390/su8080794.

- Office of the Prime Minister, 2019. Granavolden political platform for the Norwegian Government, formed by the Conservative Party, the Progress Party, the Liberal Party and the Christian Democratic Party. Office of the Prime Minister. Granavolden, 17th January 2019. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/politisk-plattform/id2626036/[Accessed 24 January 2021].

- O’Neill, K., 2019. Waste. Cambridge: Polity.

- Polanyi, K., 1944. The great transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Pullinger, M., 2014. Working time reduction policy in a sustainable economy: criteria and options for its design. Ecological Economics, 103, 11–19, doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.04.009.

- Rau, H., Davies, A., and Fahy, F., 2014. Conclusion: moving on-promising pathways to more sustainable futures. In: A.R. Davies, F. Fahy, and H. Rau, eds. Challenging consumption: Pathways to a more sustainable future. London: Routledge, 199–217.

- Renovation regulation, 2019. Renovation regulation, Røros. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/LF/forskrift/1999-02-25-315?q=røros[Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Renovation regulation, 2020. Regulation on renovation in Trondheim (LOV-1981-03-13-6- §34). Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/LF/forskrift/1999-02-25- 315?q=røros[Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Schor, J. B., 2005. Sustainable consumption and worktime reduction. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 9 (1-2), 37–50.

- Stahel, W. R., 2010. The performance economy (2nd edition). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Trondheim municipality, 2017. Energy and climate plan for 2017-2030. Available at: https://www.trondheim.kommune.no/globalassets/10-bilder-og- filer/10-byutvikling/miljoenheten/klima-og-energi/kommunedelplan-energi-og- klima130618.pdf[Accessed 28 January 2021].

- Trondheim municipality, 2019. Waste plan for Trondheim municipality 2018-2030. Available at: https://www.trondheim.kommune.no/globalassets/10-bilder-og- filer/10- byutvikling/kommunalteknikk/avfall/avfallsplan-for-trondheim- kommune-2018- 2030.pdf[Accessed 28 January 2021].

- Tunn, V. S. C., et al., 2019. Business models for sustainable consumption in the circular economy: An expert study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 212, 324–333. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.290.

- Vittersø, G., and Strandbakken, P., 2016. Forbruk og det grønne skiftet. In: G. Vittersø, A. Borch, K. Laitala, and P. Strandbakken, eds. Forbruk og det grønne skiftet. Oslo: Novus forlag, Forbruksforskningsinstituttet SIFO, 9–24.

- Wallenborn, G., and Wilhite, H., 2014. Rethinking embodied knowledge and household consumption. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.009.

- Welch, D., Keller, M., and Mandich, G., 2017. Imagined futures of everyday life in the circular economy. Interactions, 24, 46–51. doi:10.1145/3047415.

- Welch, D., et al., 2019. Consumption work in the circular economy: A research agenda. Discover Society, Issue 75. Available at: https://discoversociety.org/2019/12/04/consumption-work-in-the-circular-economy- a-research-agenda/[Accessed 19 January 2021].

- Wheeler, K., and Glucksmann, M., 2013. Economies of recycling,‘consumption work’and divisions of labour in Sweden and England. Sociological Research Online, 18 (1), 114–127. doi:10.5153/2Fsro.2841.

- Wheeler, K., and Glucksmann, M., 2015. Household recycling and consumption work: social and moral economies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wieser, H., 2019. Consumption Work in the Circular and Sharing Economy: A Literature Review. Available at: https://www.sci.manchester.ac.uk/research/projects/consumption-work/[Accessed 27 January 2021].