ABSTRACT

In the last 30 years global investment in Indian real estate has transformed cities like Delhi. Construction firms attract investors by presenting construction as transparently manifesting vetted architectural plans and agreed upon budgets. This article examines the politics of such performed transparency by focusing on the communicational genres which accompany these urban buildings. The architectural drawing and the contract supported the authority of project managers, and engineers. Yet such genres were only efficacious on the construction site when supported by other genres such as notes and sketches. These genres translated architectural schematics and budgets into the mundane work activities of the site. Produced by subcontractors, these genres shaped the activities of workers – from bending rebar to laying bricks – by framing them as acts of service within relations of patronage. Yet they also supported the authoritative account books filled out by engineers. The genres of the subcontractors translated official forms in ways that enabled the work of construction, while also laying the foundation for their own erasure in the official genres of the measurement and account books. In this way, I argue that techniques of rendering construction transparent actually reproduce the very forms of labor that they seem to supplant.

Introduction

During my fieldwork on the Indian construction industry, I would often accompany Arvind, an assistant executive engineer with the Central Public Works Department (CPWD) on his regular tours of the construction site.Footnote1 While it would one day be a ‘state-of-the-art’ lecture hall complex for a prestigious university in Delhi, the site as we saw it on our tours was a dirty and chaotic place. Carefully picking his way across bits of construction debris, Arvind inspected the progress of the building. We were met by Sandeep, an engineer with Prakash Limited a private construction firm with a track record of completing large projects. The CPWD had contracted with Prakash Limited to oversee everyday work on the site. As Arvind toured the site, he interrogated Sandeep with a string of questions. ‘You’ve only done this much? Why is the plaster so thick here? These stone tiles shouldn’t be stored like this.’ Sandeep offered explanations for each critique, none of which seemed to meet with Arvind’s approval. Finally, Arvind finished his tour and with a look of relief Sandeep left us. As we walked back to the CPWD site office, I asked Arvind about his combative technique. By way of explanation Arvind told me that it was the job of CPWD engineers to ‘check’ all the work on the site in order to ensure that their clients received the best product, ‘everything should be zero zero.’

Most narrowly the phrase ‘zero zero’ referred to fact that the built environment should match the architectural plan with elements neither a millimeter too high nor too low. As it was used by CPWD engineers and accountants, the phrase had a much wider significance, capturing a general ethos of precision, high quality standards, and transparency. Indeed, while the pursuit of ‘zero zero’ motivated Arvind’s critiques of work on the site, it also motivated the work of CPWD employees themselves which consisted primarily of creating, checking, and circulating documents. As we entered the site office of the CPWD, the din of construction noise was replaced by the low hum of air conditioners as employees sat in offices organized by rank amongst piles of paperwork. Here too precision was demanded. Official reports and accounts were checked and rechecked as they moved across the office ensuring that calculations were accurate and that they matched the contract. As one accountant described it, the process was ‘very strict’ and that ‘everything has to be zero zero.’ The documents that the CPWD generated had to correspond to each other. What emerged from this tightly calibrated set of documents was an image of construction as the orderly and transparent execution of the architectural design as specified in the contract.

Of course, the account of construction provided in these documents is only part of the story. As Arvind’s complaints suggest, the work of construction on the ground was often far from orderly and transparent. The relations of production on the site were complex. Sandeep, and Prakash Limited, were not directly responsible for the excessive plaster or the improperly stored stone tiles. This work, like much of the work on the site, had been handled by subcontractors called thekedar. Thekedar recruit workers through networks of kinship, caste, and village residence. Additionally, they attract workers by offering them advances or loans against their wages which often traps them in cycles of debt (Picherit Citation2012, DeNeve Citation2014, Fernandes Citation1986). These relationships of patronage bind workers to thekedar allowing them to supply construction sites with large amounts of cheap labor. More than supplying cheap labor, thekedar also directed this labor on the site, translating genres like the architectural plan into slips (or parchi), sketches, and commands that mobilized labor within relationships of patronage.

While thekedar were a necessary part of the industry they were also a sign of corruption and exploitation. In many media (Basu Citation2012, Burke Citation2011) and some scholarly (Vaid Citation2003) accounts of the Indian construction industry, thekedar are framed as a traditional holdover, marking the underdevelopment of the industry. Thekedar are also figured as corrupt, overbilling their clients by fabricating labor reports and pocketing the extra payment (Lehne et al. Citation2018, Tabish and Jha Citation2012). These assessments are not wrong in the sense that subcontracting to thekedar allows construction sites to skirt legal requirements around minimum wages, worker safety, and the provision of sanitary conditions (Lerche et al. Citation2017). Yet in framing thekedar as a traditional holdover, these accounts cast the ongoing use of thekedar as a result of the partial implementation of scrupulous standards of transparency like those encapsulated in the ethos of ‘zero zero.’ A closer look at the organization and representation of work on the site makes it clear that thekedar are not opposed to ‘zero zero’ construction but rather are crucial, if unacknowledged, players in its operation.

This tension between construction firms’ reliance on and attempts to distance themselves from thekedar was mediated through the documents that actors on the site used to organize and account for work. While the reports and bills of the CPWD produced an authoritative image of construction, they were only efficacious on the site through a host of other communicative forms from commands to sketches, to slips. I treat each of these communicative forms as genres to draw attention to the ‘constellation of systematically related, co-occurrent formal features and structures that serves as a conventionalized orienting framework for the production and reception’ of particular plans, account entries, commands, sketches or notes (Bauman Citation2000, p. 84). This understanding of genre moves beyond a narrow focus on the formal properties of an utterance or text to focus on how such formal properties relate to the social contexts from which genres emerge (Dickel Dunn Citation2014, Winsor Citation2000). Producing texts and utterances in the correct genres is not secondary to organizations but rather helps to shape organizations and their activities into recognizable forms, as for example when the contract presumes two unified entities linked through the exchange of materials and money.

While genres help to make particular texts or utterances recognizable as this or that type, they are not equally recognized themselves. Genres such as ‘the contract’ are internationally recognized and their formal properties are elaborated in legal texts. Yet analysts from Bakhtin (Citation1986, Bauman and Briggs Citation1992) onward have also noted genres that emerge in the everyday speech practices of different groups from trade workers to generational cohorts. Genres such as the ‘slip’ or parchi analyzed below were generally not recognized outside the context of construction while architectural plans and account ledgers could, and did, circulate far outside construction sites. Work on the construction site proceeded as actors translated back and forth between more explicitly regimented and public genres like the architectural plan or the contract, and those that were less formal and more closely tied to the construction site, like the slip or the sketch. Thekedar were crucial here as they translated general requirements for construction found in plans into specific commands for work to be done in genres like slips. Yet as work on the construction was recorded and managed, the interventions of the thekedar were occluded under the transparent accounting of amounts of transformed material provided in the reports and accounts of the CPWD.

The stakes of this occlusion have to do with shifts in the political economy of construction and real estate in India. The last thirty years have seen a massive influx of global capital as Indian real estate has become a lucrative investment. As Llerena Searle (Citation2016) has demonstrated, international investors evaluate local actors in terms of transparency, comparing them to global standards of business practice. As local firms vie for global capital, they strive to make themselves legible to investors, often taking up the language of transparency to describe their own and their competitors’ business practices. Local commentators – from journalists to construction industry experts – have taken up the discourse of transparency as well, making distinctions between the transparent practices of publicly traded construction firms and more secretive family-run firms. Documents become key in such presentations as companies open their account books as part of public valuations or furnish their contracts and reports as part of legal inquiries. While the CPWD’s practice of ‘zero zero’ construction was not explicitly for international investors, officials were acutely aware of distinguishing themselves from popular images of construction.

A chief executive engineer of the CPWD pointed to this tension when he described the site to me as ‘more modern.’ He noted that they were very careful to check all work on the site but also that the building itself had a number of innovative features including the use of environmentally friendly building materials such as fly-ash cement and bricks as well as the inclusion of a rainwater harvesting system. An international group of researchers had visited the site as an example of the increasing move toward green building practices in India. By calling the site ‘more modern’ the chief executive engineer compared the site favorably with others in India. Sites that did not present such standards of precision, use innovative technologies, or transparently document their work, were often referred to as ‘thekedari’ or ‘subcontractorish’ sites. This had little to do with whether thekedar were actually used on a site and more with the visibility of thekedar and the patronage relations through which they organized labor.

Attending to the organization of, and translation between, genres of paperwork on the site draws attention to the work that goes in to creating and maintaining the image of construction as transparent and orderly. Such an analysis is significant not because it demonstrates that claims to transparency are partial because they rely on genre translations produced by thekedar. Indeed, organizations like the CPWD were regularly critiqued in the press for failing to live up to their own claims to transparency, quality, and precision (PTI Citation2019). An analysis of the production and maintenance of transparent genres demonstrates not only how genres, and the social processes they organize, are entangled but also how they come to appear as separate. Even accounts that are critical of the construction industry suggest more transparency measures as the solution, recently focusing on digital documentation as a solution (PTI Citation2018, see also Strathern Citation2003). What emerges from the genre translations that enact zero zero construction is a separation between the practices of organizations like the CPWD and those of the thekedar on whom they rely. The system of accounting and paperwork that the CPWD uses is widely recognized as a best practice in the industry. Yet this system relies on and mobilizes thekedar and the patronage-based forms of labor that it purports to supersede.

Genres, transparency, markets

Recent work on global capitalism has begun to focus on the ways that capitalist markets and projects of value accumulation are generated out of heterogenous labors and relations (Yanagisako Citation2002, Bear Citation2013). Such a focus marks a shift from earlier accounts that demonstrated that what might appear at first glance as homogenizing capitalist practice emanating from global centers and transforming local lifeways is often much more complicated where the production and accumulation of value is always shot through with cultural specificity (Sahlins Citation1988, Taussig Citation1980, Ong Citation2010). This work brought attention to diverse ‘cultures of capitalism,’ to mark the ways that capitalist accumulation was shaped by the contexts in which it was carried out. Exploring particular cultures of capitalism draws our attention to the ways that economic relations are lived, reproduced, and transformed in the mundane livelihood practices of working people. In doing so, these accounts supplant a narrative of a unified capitalism with a panoply of capitalist, quasi-capitalist, and non-capitalist practices that give lie to images of uniformity and frictionless exchange (Gibson-Graham Citation2006).

While such interventions are crucial, these accounts have a tendency to leave fictions of global capitalism like frictionless market exchange unaccounted for. Rather than a vision of distinct varieties or cultures of capitalism, more recent work has begun to focus on how universalizing capitalist relations are generated in practice (Bear et al. Citation2015, Appel Citation2019). Images of a unified capitalist market spreading across the globe and standardizing economic practices in its wake may be fictions, but as Hannah Appel notes these fictions ‘are not merely ‘wrong’ in any narrow sense. On the contrary, they are performative in that they generate durable material and semiotic effects in the world’ (Citation2019, p. 3). The aim of analysis then is not to deconstruct such images but to account for how they are produced in the first place. To do this, scholars have turned their attention to the role of ‘conversion devices’ (Bear et al. Citation2015), technologies and procedures, that harness human and non-human capacities, to projects of value accumulation. These devices, from material infrastructures (Appel Citation2019) to techniques of audit (Bear Citation2013), convert people’s heterogenous and complex livelihood practices into forms that are tractable to projects of capitalist value accumulation (Bear et al. Citation2015, Tsing Citation2015, Narotzky and Besnier Citation2014). Analyzing the ethnographic production of images of smooth market exchange necessitates a focus on how the heterogeneity of lived economic practice is actively linked to particular images of that practice and with what effects.

Genres operate as a crucial conversion device, at once engaging heterogenous practices and enacting the appearance of frictionless market exchange. This does not happen within a single genre but rather across genres and their interrelations. Scholars have analyzed the systems (Bazerman Citation1994), ecologies (Spinuzzi Citation2003), and repertoires (Orlikowski and Yates Citation1994) of communicational genres that structure collaborative work across various organizational settings. Here communication and collaboration are structured through recognized genre forms from memos, to reports, to meetings, with each of these forms offering certain affordances to and constraints on actors. Converting the patronage relations of work on the site into the orderly exchange of built materials required the coordination of multiple genres. The slips, sketches, and commands that directed labor had to be calibrated with the contracts, architectural plans, reports, and account books of the CPWD. In the case of the CPWD, the genres were enshrined in manuals that explained how each genre should be created, checked, and related to the other genres in the repertoire (Central Public Works Department Citation2003). Beyond this highly regimented repertoire, it was the full assemblage of genres on the site that mediated the conversion of heterogenous forms of labor into the appearance of a smooth market exchange.

While work on genre repertoires demonstrates the communicational practices that coordinate work within firms, it also tends to treat genres as stable objects within clearly delimited institutional contexts. Winsor’s (Citation2000) analysis of work orders in an engineering firm expands this focus somewhat by demonstrating that which forms of communication are recognized as genres is political, reflecting the hierarchies of organizations. Engineers created work orders while technicians could only read them. This division reflected a notion that technicians merely executed the plans of engineers. As Winsor notes, such a view erases the complex forms of writing that technicians engaged in as they interpreted, checked, and sometimes fixed work orders. The notes and sketches that technicians made were not recognized as genres within the organization. Similarly, the genres produced by thekedar were not generally recognized as genres outside of the workgroup. Yet the genre assemblage of which they were a part was not bounded by an organization. Rather the production and circulation of genres occurred across groups brought together on the site. Indeed, the site itself was constituted by associations of people and paperwork.

The scholarship on transparency in South Asia (Hull Citation2012, Mathur Citation2016, Mazzarella Citation2006, Gupta Citation2012) and elsewhere (Ballestero Citation2012, Hetherington Citation2011) offers key insights in articulating the relationships between more and less formal genres. Scholars have pointed to the tendency of regimes of transparency to focus attention on the internal aesthetics of their own genre repertoires. Such a focus allows for documents to stand apart from, and overwhelm, the realities that they represent (Gupta Citation2012, Tidey Citation2013). This divergence between ground realities and ‘paper truths’ (Tarlo Citation2001) is a crucial affordance of formal genres. Yet regimes of transparency also transform practices on the ground simply by virtue of inserting documentary practices into processes of production (Hull Citation2008, p. 504). Indeed, the paperwork of the CPWD was embedded into the very processes that were misrepresented in its forms. Account books and reports were not simply separate representations but the end products of concerted genre work by subcontractors, supervisors, and engineers.

Approaching documents as embedded in the procedures that they direct draws attention to the material production of transparency. In Mathur’s account of a national employment campaign in India, she tracks the material production of transparency through the creation of ‘transparency-making documents’ (Citation2016, p. 90). These documents attested to the transparency of the processes they were part of but, as Mathur notes, they often required new and strenuous forms of work to create and maintain. In the case of the campaign, the nature of the requirements of these documents made it nearly unimplementable. The new scheme dictated that formal muster rolls of those employed be kept from the start of each project. By contrast, in older schemes contractors kept kachcha, or raw rolls, which were then converted into official forms. These kachcha rolls were made in notebooks and, so the framers of the new scheme argued, allowed for corruption as workers’ names could be easily added or subtracted from the form allowing contractors to claim scheme money for work that was never completed. Yet, as Mathur points out, these kachcha rolls enabled scheme money to be distributed much more efficiently.

The less formal genres of slips (parchi), sketches, and notebook entries can be thought of as kachcha genres in that their very malleability allowed for the enactment of formal genres of transparency. Thekedar and supervisors on the site used kachcha genres to frame completed tasks as so many units of transformed material, conflating complex negotiations of labor into numbers that could be easily taken up in the formal genres of the CPWD. Crucial here is not the system of genres itself but the material-semiotic work of translating across these different types of genres. This work took place across the relations of subcontracting on the site. Indeed, the genre work of producing and calibrating the relationship between different documents maintained these relations of subcontracting. It both connected the CPWD, Prakash Limited, and the subcontractors, by coordinating their efforts while also separating them as distinct entities. Following acts of work and their representation in plans, commands, reports, and accounts highlights the work that genres do in both coordinating heterogeneous forms of labor while simultaneously erasing the signs of such coordination.

The supply chain

To understand construction sites in Delhi, one must realize that every site is a nest of firms and contracts. All work on the site was coordinated across a wide variety of organizations that were linked together by contracts and subcontracts. Contracts and subcontracts presented each organization as a firm engaged in an exchange. On the site, other genres – from slips, to commands, to sketches – structured the coordination of contractors, subcontractors, and their workers. It was not that genres circulated within predetermined organizations, although some did, but that one of the key features of genres and genre work was creating and maintaining associations of people and things across organizations.

This structure of production had many features of a spatially condensed supply chain (Tsing Citation2009). While supply chains are usually conceived of as moving objects across spatially distinct producers to create a finished product, on construction sites distinct producers interact with an object, adding various components to produce one complex object. The image of the supply chain draws attention to the type of relationship that these different producers have with the coordinating firm and one another. As Anna Tsing notes, a key feature of supply chains is their focus on ‘inventory’ (ibid.). Lead firms are not concerned with the methods used to produce the components that they need, but whether the inventory meets agreed-upon standards and is delivered in the necessary time frames. As such, producers have a high degree of autonomy in how they organize labor as long as they provide the required inventory within the bounds of the contract. Unlike the ideal of a factory in which production is regularized by standardizing worker behaviors, the supply chain incorporates diverse labor relations seeking only to standardize the product. Genres such as contracts, reports, and account books are crucial because they articulate the relationships of inventory provision between firms, but they also create a space in which the heterogeneous forms of labor involved in the supply chain can appear as standardized and orderly exchanges.

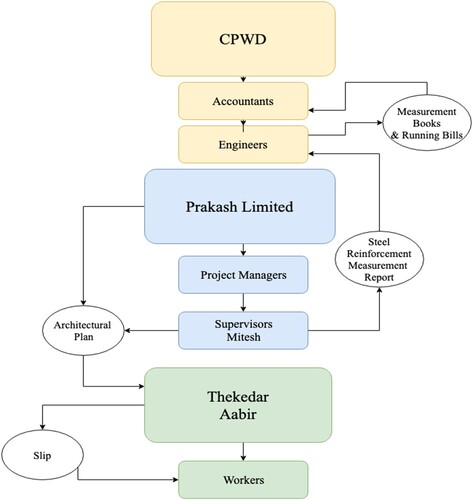

The supply chain of the site I deal with here () was overseen by the CPWD, which represented the interests of the building owners, a reputable Delhi university. The CPWD played similar roles for other public institutions in the national capital region and for federal projects. In the private sector, this role is referred to as being ‘client-side’ meaning that the firm is responsible for representing the interests of the building owner in the construction process. Client-side firms may, and the CPWD did, coordinate all construction authorizations, vetted architects, organized the bidding process to select a lead contracting firm for construction, approved the choice of subcontractors, checked the progress and quality of construction, and made payments to the lead contracting firm. I do not deal with the bidding process here as construction had already begun during my fieldwork which spanned twenty-six months from 2011 to 2015.

Figure 1. Organizational chart showing the contracting company (in blue), and subcontractors (in green). Genres of documentation and their circulation are noted on the sides.

In this case, the CPWD had signed a composite item rate contract with Prakash Limited a publicly traded construction firm that had completed a number of high-profile projects. Copies of the contract, a bound volume of about 800 pages, were kept in the CPWD and Prakash Limited site offices. When I first explained my research to Arvind, the CPWD engineer in the opening vignette, he immediately directed me to the contract, saying that it would tell me everything I needed to know. The composite item rate contract specifies per unit rates for all the different types of materials used in the building. In the composite item rate contract, construction appeared as the supply of built materials from a cubic meter of laid bricks, to a metric ton of bent reinforcement steel. The CPWD did not seek to discipline labor practices, rather it controlled the transfer of materials that included labor in the sense that they had been assembled and installed.

Prakash Limited, for its part, relied on numerous subcontractors (thekedar) to provide and direct trade-specific construction labor. The terms of these contracts varied widely depending on the subcontractor, with some including materials and labor while others only specified labor. The terms of remuneration in these contracts also varied although most specified a per unit rate of remuneration (for example, 3000 rupees per metric ton of steel reinforcement). These contracts were not as detailed as the composite item rate contract between the CPWD and Prakash Limited and in many cases, subcontractors seemed to rely more on their ongoing relationships with Prakash Limited engineers and project managers than on the legal dictates of the contract.

While subcontractors provided labor to Prakash Limited on a piece-rate basis, they remunerated their workers with day wages. This wage was verbally agreed to by workers before beginning work and was augmented by advances for buying food, chewing tobacco, and other necessities. Subcontractors also provided interest-free loans for large expenses that they counted against a workers’ future earnings (see [author redacted] for more detail). These credit and debt relations were enabled by the fact that subcontractors recruited workers that were ‘familiar’ (jān-pahchān) to them. Subcontractors recruited workers through networks of kin, caste, and village residence, bringing workers from specific districts. For example, the subcontractor in charge of steel reinforcements or bar bending recruited workers from his home district of Purnea in Bihar. This subcontractor’s foreman who was in charge of supervising workers on the site, a man I call Aabir, was the contractor’s brother-in-law. While the subcontractor made regular visits to the site and had signed a contract with Prakash Limited, Aabir was in charge of paying workers’ wages, giving advances, and directing their daily work on the site. The networks of social connection and patronage that subcontractors mobilized allowed them to recruit, retain, and control large numbers of workers. Such accumulation of workers allowed subcontractors to present labor to Prakash Limited as a flexible resource to be accounted for in units of built material.

From plan to parchi

Transparent construction began and ended with the architectural plan. It was the correspondence between structure and plan that was the core of ‘zero zero’ yet for the plan to be enacted it had to be converted into a host of other documents and conversations that were capable of mobilizing workers. In this process, thekedar translated the general terms of inter-firm exchange set out in the architectural plan into specific exhortations to work shaped by worker-subcontractor relationships. Here the transparent genres of the plan and the contract became entangled with kaccha genres as plans were annotated, instructions were written, and commands given. Here too there were conventionalized forms but ones that were often only recognizable within the worker-subcontractor relationships in which they operated. Indeed, much of the genre work that subcontractors engaged in involved not only converting the plan into actionable genres but also involved rendering this conversion invisible.

This process began in the offices of Prakash Limited, located on the opposite side of the site from the CPWD site office. Decisions about which parts of the building should take priority were made in nightly meetings overseen by the most senior Prakash Limited project manager on the site, Prajit. From behind his large desk, Prajit would listen as Prakash Limited engineers reported on the progress of the day. On the wall behind him was a large blow-up of a top-down architectural plan for the entire project. Framed by this image of the building, Prajit seemed to speak for the project itself as he interrogated engineers, foremen, and supervisors about why more progress hadn’t been made, or delivered directives on which parts of the building should take priority. In one such meeting, Prajit decided that the steel reinforcements of the floor beams on the second floor of the central wing of the building should be the priority for the following day. In the meeting this area was referred to in the terms of the architectural plan which divided the wings of the building into blocks, the central wing being A-block. Thus, the decision was that the reinforcements for ‘A2’ or A-block level two should be built.

Prajit’s decision was delivered to Mitesh, the Prakash Limited foreman in charge of bar-bending (see ). At the beginning of the next day, Mitesh went to talk to Aabir, the bar-bending foreman. Mitesh explained the new priority to Aabir saying that the rebar reinforcements for the second floor of A-block needed to be done. Aabir began by creating an inter-genre translation, rewriting a section of the architectural plan as a work order or a parchi (slip) as the bar-benders called it. To make the slip, Aabir had to read across different parts of the architectural plan (see below). Specifically, he coordinated between a top-down drawing of the second floor of A-block and a document called a ‘bar-bending schedule’ that specified the dimensions of all the reinforcements in the building. Using these documents, Aabir was able to determine the number, type, and dimensions of each piece of rebar needed to make the reinforcements. Aabir wrote down the relevant information on a notepad. The resulting slip (see below) specified the diameter (left column), number, and dimensions of each piece of rebar that Aabir’s men would have to make. The circled numbers indicate different sections of beams (thus the two ones are two different sections of the same beam). The slip, was meant to direct the activities of his workers, guiding them to cut, bend and install different pieces of rebar into place.

In making the slip, Aabir translated the plan, a description of a possible built structure, into an instructional list. As Cornelia Visman notes, the list is a form of writing that aims to ‘control transfer operations … The individual items are not put down in writing for the sake of memorizing spoken words, but in order to regulate goods, things, or people’ (Citation2008, p. 6). Made to be slipped into shirt pockets, folded, crumpled, read and re-read, Aabir’s slips were indeed kaccha (or raw) genres, almost always destroyed before the construction process was complete. Indeed, the slips that another bar-bender thekedar made were scribbled on scrap pieces of cardboard. The form of these lists also confirmed their transient and context-bound nature. Nowhere on the slip was the area of the building referenced, in order to read such a slip, one would have to have been privy to the conversation where Aabir informed his men of work to be done on a given day. The slip only worked in the context of the thekedar-worker relationship. Indeed, the slip worked in conjunction with verbal commands, social connections, and credit to enact (Mol Citation2002) the labor of the bar-benders as service given to a patron.

While slips and similar genres enacted subcontractor-worker relations of production the specifics of this were particular to the subcontractor and his group of workers. This is visible in the content of Aabir’s slips. The list of items does not necessarily reflect all of the beams on the second floor of A-block. That is, the slip does not cover the same amount of work specified in Prajit’s decision. Instead, the work depicted in the slip reflected daily negotiations that Aabir engaged in with his workers in which he assigned particular groups of workers to certain tasks. If the workers deemed the task to be especially difficult, they could, and did, negotiate with Aabir for increased pay, additional workers, or a reduction in the amount of work to be done in the day (see [author redacted]). The ability of workers to negotiate in this way was a central reason that subcontractors such as the one Aabir represented were able to attract and retain large numbers of workers. Once the group and the terms of the work had been set, Aabir would make the slip and give it to the most senior worker in the group. This man would then direct the others on how to cut, bend, and arrange the pieces of rebar for the beam. As noted above the slip was not explicit about where pieces were to be located. Aabir and the group leader would determine this as they walked around the area where the rebar was to be installed. But it was also the case that experienced bar-benders could tell how rebar pieces should be positioned based on their shapes. An L-shaped piece of rebar of a high dimension, for example, would likely form the outside edge of a beam.

The form of the slip then was uniquely shaped to the organizational relationship between Aabir and his workers. It responded both to the negotiations of work tasks and to the expertise of skilled bar-benders. As a genre, the slip was synonymous with the role of a bar-bending thekedar or his foreman. While slips varied somewhat across bar-bending thekedar they bore formal similarities in the information communicated (number, shape, and diameter of rebar pieces). Moreover, the ability to create a slip by reading the architectural plan was mentioned again and again by workers as a skill that typified the thekedar or foreman and separated them from regular workers. Yet the slip rarely circulated beyond the bar-benders, indeed lacking any written references to the area of the building, the slip was virtually useless outside the work of installing a particular section of rebar. As a kachcha genre, the slip was useful within the sphere of rebar installation but would need to be revised and formalized to circulate beyond it.

The movement from plan to parchi demonstrates how generalized calls to complete a particular section of the building were translated into the patronage relations through which workers could be mobilized. As a translation, the slip and the plan seem to represent the same thing – specific elements of a built structure – in different forms. Yet, as scholars of translation have long noted (Gal Citation2015, Sakai Citation1997), these shifts in form are far from neutral. It is true that Aabir’s slip converts information from the plan into a form that is legible to his workers but, it does so in a way that partakes in the enactment of patronage relations. The slip exhorts bar-benders to complete a negotiated amount of work determined between a patron and his workers, rather than the completion of a section of the building deemed important by Prajit. The authoritative genres of the plan and the contract then could not mobilize labor on their own. They relied on genres like Aabir’s slip to translate their directives into forms capable of catalyzing action.

The slip also allowed Aabir to encompass his workers, or to enfold their labor into his own. In this regard, the slip functioned much like the work orders that Winsor (Citation2000) discusses. Winsor describes how engineers directed the work of technicians through the genre of the work order. Yet, like Aabir’s slips, the genre of the work order took interpretive effort to discern. These genres rely on and presume the skill and experience of workers, a feature reflected in their forms which often lack explicit references to the work being ordered. The writers presume that the documents will function within ongoing conversations or longer work experience. At the same time, Winsor notes, that work orders can be ‘read retroactively’ (ibid.) to give the impression that the work of the technicians was simple execution of a pre-formed plan. In a similar way, Aabir’s slips were part of the thekedar-worker relationship in which the bar-benders were not working for Prakash Limited or the CPWD in any direct sense, rather they were carrying out their end of a patronage relationship with the bar-bending thekedar. The slips, along with the other commands, remunerations, and loans given to workers, reinforced Aabir’s role as the catalyst of work. This relationship was widely recognized on the site with Prakash Limited supervisors and engineers referring to the complex activity of building rebar reinforcements as ‘Aabir’s work,’ as in ‘has Aabir’s work been done?’. Aabir’s slip particularized production by rendering calls for completing parts of the building into imperatives for specific kinds of action delivered to specific people. But it also separated these interactions from Prakash Limited and the CPWD by encapsulating them in the figure of the thekedar.

From parchi to plan

In translating across genres thekedar, and others, not only particularized the plan so that it could be enacted on the ground, but they also set the foundations for producing genres of transparent construction. The measurement book, the running bill, the contract, and the plan rely on genres like Aabir’s slips not only because these kachcha or raw genres were part of getting work done but also because they frame this work in ways that become tractable to the genres of transparent construction. This dynamic becomes particularly visible when examining the kachcha genres through which completed work was measured and accounted for.

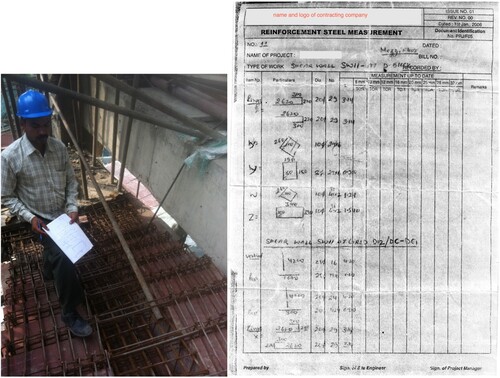

Once the rebar for the beams had been completed, Mitesh, the Prakash Limited supervisor, returned to the area on the second floor of A-block to take measurements of all the rebar that had been installed. With pen, notebook, and measuring tape in hand, he set about recording the dimensions and number of each piece of rebar in the beams. The result was a set of sketches that Mitesh would use to fill out an official ‘Reinforcement Steel Measurement’ report (see below) which had two carbon copies. Unlike the slip, the report explicitly linked the work completed to the architectural plan through references to the architectural grid. This is evident in Figure 3 which is for a different part of the building namely a shear wall designated as SW11 at D-Block. By aggregating the measurements for all the rebar pieces in a given area, Prakash Limited foremen and engineers were able to calculate the weight of rebar installed. This allowed Prakash Limited to bill the CPWD in accordance with the contract which specified a per metric ton rate for rebar. Similar reports were completed for each type of work on the site.

Completed reports were checked jointly by the CPWD and Prakash Limited. In the case of the beams of the second floor of A-Block, Mitesh completed the report and brought it to a Prakash Limited engineer. The two of them then went to meet Arvind, the CPWD engineer, on the second floor of A-Block. Moving methodically through each line of the report, Arvind asked ‘where is this?’ and Mitesh would point to the pieces of rebar noted on that line of the form. After working his way through the entire report, Arvind, the Prakash Limited engineer, and Mitesh signed the report in a designated area. Mitesh then tore out one copy for Arvind and retained the original and third copy for Prakash Limited’s files. When I first observed this process, the Prakash Limited engineer told me that the reason there were so many signature lines was to eliminate ‘corruption’ (brashtachar). He explained that the measurement of work was a stage where unscrupulous engineers could collude with contractors to inflate the amount of material in the report, thus charging the client extra. This would mean both that Prakash Limited received extra money and that the contractor would eventually receive extra money, which he would eventually split with the crooked engineer. By requiring multiple parties to attest to the veracity of the report, Prakash Limited ensured that corruption would become prohibitively expensive and that inconsistencies could be traced back to corrupt individuals. In this way, the engineer framed the report as part and parcel of transparent construction.

Astute readers will have noted that the insistence on multiple signatures and even Arvind’s checking of the report did not actually seem to be oriented toward the referential capacities of the document. In all the interactions that I witnessed, I never saw a CPWD engineer check the measurements. This is made all the more critical by the fact that Mitesh often copied the measurements for the report from Aabir’s own slips. The multiple signatures on the report and careful checking of each line of the report were both designed to ensure the internal consistency and validity of the form itself but such procedures leave open the question of how the document relates to the material processes it purports to regulate and account for.

This divergence between form and practice is a common feature of bureaucracies in places like South Asia, where scholars have long commented upon the political effects of proceduralism (Gupta Citation2012, Hull Citation2012, Mathur Citation2016). This gap between the transparent and carefully checked formal genres of the construction site and the scribbled slips and sketches is crucial because it demonstrates how formal procedure is entangled with everyday practices. On the one hand, the actions of workers become invisible. On the other, kachcha genres like the slip or the sketch work as the building blocks for the formal genres of transparent construction, providing the amounts and measurements for reports and account book entries. In translating across genres actors on the site at once occluded the labor of construction and grounded a very different image of construction in everyday practice.

This dynamic was at work in the generation of the Reinforcement Steel Measurement report, but it is perhaps most explicit in the other kachcha genres of measurement that Prakash Limited engineers created. For example, one Prakash Limited engineer, Sivamani, was put in charge of recording the work done by one of the many stone tile thekedar on the site. The thekedar, Rajesh, ran a group of masons from Rajasthan and had won a contract for affixing large sandstone tiles to the exterior of the building. To measure the work done, Sivamani and Rajesh walked out to the exterior wall of one of the wings of the building. One of Rajesh’s workers stood on the roof of the building and held one end of a long tape measure that he tossed to another worker leaning out of a window below. In this fashion, the team of workers collected measurements for the whole wall that they yelled down to Rajesh and Sivamani who took them down in a notebook. Sivamani went on to calculate the total surface area of the windows and subtracted this from the total. Yet before Sivamani could finish, Rajesh reminded him that they also had to add in extra for ‘that spot’ pointing to the top left corner of the wall. It turned out that Rajesh and his men had started installing tiles only to find out that the CPWD had changed its mind about how it wanted the tiles to be installed. Rajesh’s men had been forced to take down the tiles and start the wall over again. Rajesh was alerting Sivamani to the fact that this extra work needed to be accounted for in the bill.

Sivamani did not protest against Rajesh’s claim, nor did he attempt to measure the area that had been tiled twice. Instead, he looked at the number he had already come up with, rounded it out and came back at Rajesh with an inflated total. To this, Rajesh complained that the work had been very difficult, and it had taken a long time to detach the large and heavy stone tiles. Sivamani and Rajesh proceeded to haggle over a reasonable price, but they did so in the medium of the wall’s measurement. Here a number of factors – the difficulty of the work, the stress of a last-minute change, the possible damage to materials – were conflated into the number of square meters that Sivamani would claim had been tiled. This haggling provided thekedar an opportunity to ensure their profits against unforeseen expenses due to the difficulty or the work or last-minute changes. Engaging in these negotiations was expected by thekedar and was an important way in which firms like Prakash Limited attracted and retained thekedar. On the other hand, such adjustments could not be directly entered into the documentary accounts of work on the site without puncturing the image of transparent construction. Sivamani’s solution is a creative act of genre translation where the complexities of his relationship to the thekedar are translated into the numerical forms of his notebook calculations. Sketches that are themselves converted into formal reports and ultimately checked and rechecked for internal coherence as they entered the genre repertoire of the CPWD.

It is only after the kachcha genres like Aabir’s slip or Sivamani’s sketches are converted into reports and delivered to CPWD engineers that the official genres of CPWD can create a ‘zero zero’ account of construction. Once reports like the Reinforcement Steel Measurement Report were checked, the CPWD engineer took his copy to the site office and used the information to fill out a measurement book entry. The measurement book entry copied the information in the report but added the payment rate for the particular task from the item rate contract. It also included an estimation of the total value of the piece of work.Footnote2 Once noted in the measurement book the work could be smoothly integrated into the CPWD’s genre repertoire. The entries were used by CPWD accountants to create a ‘running bill’ which represented the task in question as a portion of the total amount estimated for that type of work in the composite item rate contract. The measurement book and the running bill figured the work of construction as the transparent exchange of amounts of built material for amounts of money in accordance with the norms set out in the contract.

The conventions for these genres are highly regimented in office manuals that elaborate how entries should look, whether pen should be used for the entries, and how mistakes should be amended (Central Public Works Department Citation2016). These specifications are linked to transparency. The CPWD works manual notes that measurement book entries ‘should be so written that transactions are readily traceable’ (Central Public Works Department Citation2003, p. 46). The goal of this genre repertoire is to provide a transparent account of the construction process, one that is designed for and can stand up to public scrutiny. These accounts were to be ‘maintained very carefully and accurately as these may have to be produced as evidence in a court of law, if and when required’ (ibid.). Unlike slips and sketches, measurement books and running bills were meant to circulate widely outside the construction site, forming the basis of the Central Public Works Department’s claims to transparency and modern construction practice.

Given the importance of these genres, it is perhaps unsurprising that they were checked and rechecked as they moved between assistant engineers, accountants, and the chief executive engineer. As accountants made the running bill, they checked and rechecked the calculations in the measurement book and confirmed that the rate quoted matched that given in the contract. Likewise, when running bills were sent to the chief executive engineer, the calculations were again checked and confirmed against the contract. It was only after these steps that the bills were sent to the central office and checks for the completed work issued. It was this work of ensuring the internal coherence of the genre repertoire that is being pointed to when engineers and others speak of ‘zero zero’ construction or ‘modern’ construction sites.

Despite this strict focus on the coherence of the genre repertoire, there is relatively less concern with confirming that the measurements in the measurement book entries accurately reflect what was installed in the building. Indeed, the genre repertoire of the CPWD relies on the reports made by Prakash Limited engineers to supply the measurements that it uses. Here Mary Poovey’s distinction between ‘precision’ and ‘accuracy’ is helpful (Citation1998, p. 31). She notes that one of the effects of double-entry bookkeeping was to make the formal precision of the arithmetic seem as if it guaranteed that the items recorded accurately reflected the transactions made. In a similar way, the genre repertoire of the CPWD provides an incredibly precise account of transactions but one that does not necessarily accurately reflect the work done on the site. The negotiations between Aabir and his men or between Sivamani and Rajesh disappear into the precise exchanges of materials for money. What emerges is a picture of orderly exchange transparently manifesting the architectural plan in line with the agreement made in the contract. Here the genre repertoire of the CPWD draws on caste-based hierarchies that are entangled with engineering practice in India which distinguished the planning and theoretical knowledge of high-caste engineers from the practical knowledge of artisanal castes (Subramanian Citation2019).

Conclusion

The genre translations of transparent construction are significant not only for understanding the production of images of transparent construction but also as a key communicative mechanism of capitalism. What is significant in this regard is not genre repertoires themselves but rather the ways that genre work mediates different forms of labor. What appears as opposed to the genre repertoire is as important as what is explicitly presented. Images of transparent construction like the ones that emerge from the genre repertoire of the CPWD have become common among reputable construction companies in India. This is not, however, to say that the image of transparent production is widely persuasive. Popular critiques of construction in India reveal the corrupt practices of even the most reputable firms, including the CPWD. Yet these critiques frame the problem as a lack of transparency, calling for further efforts at transparent accounting in construction (van der Loop Citation1996). Here the techniques of enacting transparency seem to be opposed to supposedly traditional relations of labor recruitment and control typified in the figure of the subcontractor (thekedar) (cf. DeNeve Citation2014).

Attending to the cross-genre translations through which transparent construction operates highlights not only the entanglement of reputable construction firms and ‘traditional’ subcontractors, but it also demonstrates how these two realms come to appear separate. Kaccha genres like Aabir’s slip or Sivamani’s sketches are doubly important here. Aabir’s slip offered a conventionalized way of ordering his workers to work by converting a general directive (‘finish the steel reinforcements for the second floor of A-block’) into a particular request for service within an ongoing relationship of patronage. Sivamani’s note converted the ongoing social obligations of subcontractor and contractor into the standardized form of measured materials. These kaccha genres reproduce the relations of labor and patronage associated with subcontractors in India. But they also form the building blocks of the genre repertoire by which the CPWD enacts transparency. Far from opposing the patronage relations of subcontractors then, transparent construction relies on subcontractors not only to supply labor to sites but to frame this labor in ways that can be worked into ‘zero zero’ accounts. In such accounts this entanglement is erased with the result that the chief engineer of the CPWD was able to describe the site as ‘more modern’ despite knowing that, like all sites in India, it relied on labor contractors and their patronage networks of kin, caste, and village residence.

Attending to genre work highlights this double movement of entanglement and erasure and the value that emerges from this process. The genre work that underlies transparent construction enacts a form of ‘modularity’ (Appel Citation2012, p. 698) in which heterogenous forms of labor are framed into the components of a smooth exchange. Unlike Taylorist factories, modularity aims not to regiment behavior but rather to convert diverse behaviors into standardized capitalist forms (Bear et al. Citation2015). Bringing these insights together with linguistic anthropologica and organization studies accounts of communicative genres allows us to situate processes of conversion in the mundane acts of communication that structure production. Here it is not the genres themselves but rather the translational work that actors do in alligning and connecting genres that generates an image of smooth market exchange out of the complex patronage relations that catalyze work activities on the site.

Attending to the translations across communicative genres expands our analyses of the organizational work that genres do. This is not only limited to structuring activities within an organization but rather in articulating and negotiating complex relations of subcontracting that increasingly characterize contemporary capitalism. Rather than tracing a stable set of communicative genres within an organization, focusing on the work of translation provides a nuanced account of how different organizations and labor relations are sutured together. This process is particularly significant in India where the genre work of transparent production enables construction firms to rely on the exploitative labor practices of subcontractors even as they purport to depart from or even correct them. Tracking genre translations offers a framework for analyzing the ways that heterogenous forms of labor often located in the informal economy are harnessed to projects of value accumulation. This mundane genre work forms a crucial communicative infrastructure of global capitalism not only by linking diverse organizations and relations of labor together on the ground, but also by occluding these links under the modular forms of market exchange.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the engineers, subcontractors and workers on the construction site for generously giving me their time and entertaining my questions. I would also like to thank the editors of special issue, Ilana Gershon and Michael Prentice, for insightful feedback on an earlier draft of this piece and for their help in ushering this project through publication. My thanks also to Ella Butler, Anna Jabloner, Matthew Hull, Martha Lampland, Erin Moore, Malavika Reddy, Jay Sosa, Malini Sur, and participants at the ‘Genres in the New Economy’ workshop held at University of Indiana for very helpful comments on previous versions of this paper. All mistakes are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adam Sargent

Adam Sargent is a writing advisor in the Social Sciences Collegiate Division of The University of Chicago. He completed his PhD in sociocultural anthropology at The University of Chicago. His research focuses on questions of labor, technology and capitalist development. He pursues these questions through ethnographic research on construction workers in India and, with collaborators, on engineers in the US.

Notes

1 With the exception of the Central Public Works Department, all personal and organization names are pseudonyms.

2 While the measurement book entries and running bills were meant to circulate publicly if needed, I was not allowed to photograph or copy any examples from the site.

References

- Appel, H, 2012. Offshore work: Oil, modularity, and the how of capitalism in Equatorial Guinea. American Ethnologist, 39 (4), 692–709.

- Appel, H, 2019. The licit life of capitalism: US oil in equatorial Guinea. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bakhtin, M.M, 1986. Speech genres and other late essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Ballestero, A, 2012. Transparency in triads. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 35 (2), 160–166.

- Basu, M, 2012. India has no room for its wandering builders. The Hindu, 1 May. Available at http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/india-has-no-room-for-its-wandering-builders/article3371330.ece.

- Bauman, R, 2000. Genre. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 9 (1–2), 84–87.

- Bazerman, C, 1994. Systems of genre and the enactment of social intentions. In: A. Freedman, and P. Medway, eds. Genre in the New rhetoric. London: Taylor and Francis, 79–101.

- Bear, Laura, 2013. ‘This body is our body’: Vishwakarma Puja, the social debts of kinship, and theologies of materiality in a neoliberal shipyard. In: S McKinnon, and F Cannell, eds. Vital relations: modernity and the persistent Life of kinship. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 155–178.

- Bear, L., et al., 2015. Gens: A feminist manifesto for the study of capitalism. Theorizing the contemporary, Fieldsights, March 30. Available at https://culanth.org/fieldsights/gens-a-feminist-manifesto-for-the-study-of-capitalism.

- Briggs, C. L., and Bauman, R., 1992. Genre, intertextuality, and social power. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 2 (2), 131–172.

- Burke, J, 2011. Indian Grand Prix: Workers on F1 Circuit “Living in Destitution.” The Guardian, 28 February. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/oct/28/indian-grand-prix-f1-workers.

- Central Public Works Department, 2003. CPWD Works manual. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Central Public Works Department, 2016. CPWD compilation book of forms: As referred to in central public works account code. New Delhi: Nabhi Publications.

- DeNeve, G, 2014. Entrapped entrepreneurship: labour contractors in the South Indian garment industry. Modern Asian Studies, 48 (05), 1302–1333.

- Dickel Dunn, C., 2014. ‘Then I learned about positive thinking’: The genre structuring of narratives of self-transformation. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 24 (2), 133–150.

- Fernandes, W, 1986. Construction workers, powerlessness and bondage. Social Action, 36 (3), 264–291.

- Gal, S, 2015. Politics of translation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 44, 225–240.

- Gibson-Graham, J.K, 2006. The end of capitalism (as we knew it): A feminist critique of political economy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gupta, A, 2012. Red tape: bureaucracy, structural violence, and poverty in India. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hetherington, K, 2011. Guerrilla Auditors. Guerrilla Auditors. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Hull, M, 2008. Ruled by records: The expropriation of land and the misappropriation of lists in Islamabad. American Ethnologist, 35 (4), 501–518.

- Hull, M, 2012. Government of paper: The materiality of bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lehne, J., Shapiro, J. N., and Eynde, O. V., 2018. Building connections: Political corruption and road construction in India. Journal of Development Economics, 131, 62–78.

- Lerche, J., et al., 2017. The triple absence of labour rights: Labour standards and the working poor in China and India. Centre for Development Policy and Research, SOAS, University London Working Paper 32/17: 1-30.

- Mathur, N, 2016. Paper tiger: Law, bureaucracy and the developmental state in Himalayan India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mazzarella, W, 2006. Internet X-Ray: E-governance, transparency, and the Politics of imediation in India. Public Culture, 18 (3), 473–505.

- Mol, A, 2002. The body multiple, ontology in medical practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Narotzky, S, and Besnier, N., 2014. Crisis, value, and hope: Rethinking the economy. Current Anthropology, 55 (S9), S4–S16.

- Ong, A, 2010. Spirits of resistance and capitalist discipline: factory women in Malaysia. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Orlikowski, W. J., and Yates, J., 1994. Genre repertoire: The structuring of communicative practices in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39 (4), 541–574.

- Picherit, D, 2012. Migrant labourers’ struggles between village and urban migration sites: Labour standards, rural development and politics in south India. Global Labour Journal, 3 (1), 143–162.

- Poovey, M, 1998. A history of the modern fact: problems of knowledge in the sciences of wealth and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Press Trust of India (PTI), 2018. CPWD to monitor projects, works through web-based software. Business Standard India. 22 April. Available at https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/cpwd-to-monitor-projects-works-through-web-based-software-118042200253_1.html.

- Press Trust of India (PTI), 2019. BJP member raises in RS issue of alleged corruption in CPWD works. Business Standard India. 3 July. Available at https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/bjp-member-raises-in-rs-issue-of-alleged-corruption-in-cpwd-works-119070301292_1.html.

- Sahlins, M., 1988. Cosmologies of capitalism: The trans-pacific sector of ‘the world system.’ Proceedings of the British Academy LXXIV: 1–51.

- Sakai, N, 1997. Translation and subjectivity: On Japan and cultural nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Searle, L, 2016. Landscapes of accumulation: real estate and the neoliberal imagination in contemporary India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Spinuzzi, C., 2003. Compound mediation in software development: using genre ecologies to study textual artifacts. In: C. Bazerman, and D. R. Russell, eds. Writing selves/writing societies: research from activity perspectives. Denver: The WAC Clearinghouse, 98–125.

- Strathern, M, 2003. Audit cultures: anthropological studies in accountability, ethics and the academy. London: Routledge.

- Subramanian, A, 2019. The caste of merit: engineering education in India. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Tabish, S.Z.S., and Jha, K. N., 2012. The impact of anti-corruption strategies on corruption Free performance in Public construction projects. Construction Management and Economics, 30 (1), 21–35.

- Tarlo, E, 2001. Paper truths: The emergency and slum clearance through forgotten files. In: C.J. Fuller, and V. Benei, eds. The everyday state in modern India. London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 68–90.

- Taussig, M. T, 1980. The devil and commodity fetishism in South America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Tidey, S, 2013. Corruption and adherence to rules in the construction sector: reading the ‘bidding books.’. American Anthropologist, 115 (2), 188–202.

- Tsing, A, 2009. Supply chains and the human condition. Rethinking Marxism, 21 (2), 148–176.

- Tsing, A, 2015. The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Vaid, K.N, 2003. Management and labour in the construction industry in India. Mumbai: National Institute of Construction Management and Research.

- van der Loop, T, 1996. Industrial dynamics and fragmented labour markets: construction firms and labourers in India. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Vismann, C, 2008. Files: Law and media technology. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Winsor, D, 2000. Ordering work: blue collar literacy and the political nature of genre. Written Communication, 17 (2), 155–184.

- Yanagisako, S, 2002. Producing culture and capital. Princeton: Princeton University Press.