ABSTRACT

This article examines the issuance of ‘certificates of stock’ in return for financial donations towards missionary chapels and schoolhouses in the late nineteenth-century American Presbyterian home missionary enterprise. No dividend or interest payment was made by the missionary agency. Instead, fundraisers explained that the ‘dividends’ on these ‘investments’ were spiritual, promising donors an improvement in their spiritual lives now, and potentially even greater ‘returns’ in the hereafter. The emergence of this method of raising funds is an example of how American religious organisations have used the methods of the commercial world in their fundraising strategies. However, as this article shows, it also sheds light on the mutual entanglement of religion and economy, values, and finance in the spheres of both the market and the church. At a time when many American Protestants were morally ambiguous about investor capitalism, the emergence and development of this mode of fundraising represented one of the ways investor capitalism was legitimised as a necessary, and respectable, economic activity for Protestant believers in a modern capitalist economy. At the same time, it also reflected a broader reframing of financial donations as worship within the Presbyterian Church.

Beginning in the late 1870s a new form of Christian missionary fundraising emerged in the United States of America: the issuance of ‘certificates of stock’ for donations towards missionary chapels and related buildings. The practice of issuing certificates of stock holdings was common in financial markets, but in missionary fundraising, it represented a new and rather different phenomenon. Unlike commercial stocks, missionary ‘stocks’ were not for financial profit. No financial return was expected by the purchasers. No dividend or interest payment would be made by the missionary agency. Instead, missionary fundraisers explained that the dividends on these ‘investments’ were spiritual, helping to usher in the ‘Kingdom of God’. This was not the first foray of American religious institutions into using commercial and business strategies. The rich historiography on American religion highlights the various ways religious organisations have utilised strategies and models from commercial business for their own purposes (Moore Citation1995; Nord Citation2002; Lee and Sinitiere Citation2009). Throughout US history they ‘drew explicitly upon financing models and organisational blueprints arising from the development of business,’ as historians Amanda Porterfield, John Corrigan, and Darren E. Grem highlight in their recent work (Citation2017, 6).

Much of the focus of existing scholarship, however, is on religious beliefs and values, tending to emphasise the ways religious leaders and organisations have ‘marketed’ their beliefs in the pluralist religious landscape of the United States. This ‘economics of religion’ approach, though useful, overlooks the way religious leaders and institutions raised and managed their own financial resources (McCleary Citation2011). As Sarah Koenig (Citation2016, 91–92) notes, the relationship between ‘Almighty God’ and the ‘Almighty Dollar’ in the financing and fundraising of American religion is a theme in need of further exploration. By focusing upon how religious organisations raised their own financial resources we gain an understanding of the different ways American Protestants responded to developments in the market economy (see Noll Citation2002; Hudnut-Beumler Citation2007).

This article explores this theme by examining how the Presbyterian Church in the USA (hereafter PCUSA) drew on the rhetoric, style, and strategies of investor capitalism to raise funds for its home missionary enterprise. After introducing the PCUSA and its home missionary enterprise, I go on to examine how Protestant ministers helped to legitimise investor capitalism as a respectable vocation for church members, despite the negative perception of the world of Wall Street in the late-nineteenth century. I then analyse the beginning and development of the use of certificates of stock in home missionary fundraising, analysing some specific examples, before situating this mode of fundraising within a broader change in attitude toward religious donations within the Presbyterian Church, which increasingly framed financial donations as worship, with regular financial donations to the church becoming an integral part of a Christian spiritual life.

By the phrase ‘investor capitalism’ I refer to individuals with financial capital participating in financial markets, placing their fiscal resources in commercial stocks and bonds in the expectation of future returns, whether in the form of a dividend or interest payment, or by the growth in the stock market value of their shares and investments. Other phrases have been used by scholars, such as ‘financial capitalism’ or ‘investment economy’, which similarly encapsulate this economic activity. However, the phrase investor capitalism emphasises the role and agency of the investor in this activity, as opposed to other practices of financial capitalism that scholars have highlighted, such ‘managerial capitalism’ whereby decisions about financial investments are made by fund managers, on the behalf of investors (Bryer Citation1993). By emphasising the individual investor in this economic behaviour, the phrase best encapsulates the individual’s felt experience of being an investor, with a vested interest in the prospects in a business or an endeavour, and the sense of value that it derived. A sentiment that home missionary fundraisers sought to capitalise on by adopting this mode of fundraising. Furthermore, the phrase investor capitalism conveys the sense of moral culpability and responsibility investing in financial markets had for American Protestants in the late-nineteenth century. Indeed, financial markets were popularly understood by Gilded Age Americans as driven by the actions of individuals, whether collectively or singularly, as such economic recessions were often attributed to the morally questionable decisions of individuals, especially the infamous ‘Robber Barons’ (Geisst Citation1999, 68). Engaging in financial capitalism was not a morally neutral venture for an investor, but one with ethical implications for the individuals that participated in it.

The home missionary enterprise of the presbyterian church in the USA

Though usually not the most numerous among Protestants, Presbyterians have ‘often had an influence in society that exceeded their numbers because of their generally high levels of education, wealth, and status’ (Smith and Kemeney Citation2019, 2). The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America of the late-nineteenth century was little different from this general characteristic. Although not the largest denomination in country, it was one of the wealthiest and its membership was typically middle-class, from the states of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Ohio, where the majority of its churches and members resided (Balmer and Fitzmier Citation1993; Hart and Muether Citation2007; Longfield Citation2013). The focus upon this specific denomination is principally for continuity, to maintain the focus on the developments in one missionary organisation, as opposed to skipping across different denominations and missionary societies without sufficient context. However, this research does not seek to be narrowed by the focus upon the PCUSA, but rather uses it as a representative of like-minded organisations. The Presbyterian Church stood alongside similar denominations as part of a broad evangelical Protestant culture, which though they had particular differences, shared similar practices, beliefs, and importantly, the need to raise sufficient fiscal resources to sustain their churches, congregations, ministers and home missions.

The home missionary enterprise of the PCUSA was orchestrated by two centralised organisations, the Board of Home Missions and the Woman’s Executive Committee of Home Missions (hereafter WECHM). These were professional missionary organisations with salaried officers and administrators, and a committee of lay and clerical members, based in the Board’s central offices in Manhattan, New York City. By the 1880s, these two organisations had oversight of over 1,500 missionaries, 200 missionary teachers and 86 schools. They annually fundraised roughly $650,000 dollars (an estimated $17,500,000 in current U.S. dollars) and published a monthly periodical with a circulation of 30,000 (PCUSA Board Citation1885).Footnote1 In the late-nineteenth century the evangelistic focus of the Presbyterian missionary enterprise was on the American West and its diverse populations of Mormon, Mexican and Native American peoples. Therefore, much of the resources and activities of Presbyterian home missionaries were centred on founding churches, mission schools, and institutions of higher education in the territories of New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona (Banker Citation1993).

The mainstay of home missionary fundraising was the voluntary donation made by members at their local church. This mode of fundraising, repeated year after year in numerous places and by various peoples, was not due to a lack of imagination, relying on an inconspicuous mode of fundraising. Rather, it played to the Board’s key strength that it was part of a national denominational network. This meant that both the Board and the WECHM had a constituency upon which to base their fundraising appeals, as well as an extensive network of local church institutions, church ministers, deacons, elders, Sabbath School teachers and Superintendents to raise and collect funds. It also meant that these funds could be reliably transferred upwards to the Board of Home Missions – from churches to Presbyteries, Presbyteries to Synods, and finally from Synods to the General Assembly. A dollar donated by a congregant in a Presbyterian Church in rural Iowa would reliably make its way to the Board of Home Mission’s coffers in New York City.

Presbyterian home missionary fundraising also relied upon local Women’s (or Ladies’) Missionary Societies within Presbyterian congregations. Their name may conjure up images of parochial do-gooders, yet these were serious and sophisticated organisations, undertaking most of the groundwork of promoting and fundraising for Presbyterian home missions, as well as providing opportunities for female activism within the church (Yohn Citation1995). Orchestrated from the WECHM in New York each ‘auxiliary’ missionary society was organised ‘in strict and systematic conformity’ (WECHM Citation1886), adhering to a constitution, a set plan of action, and instructions to hold church and public meetings for home missions. By the late 1880s, there were nearly four thousand local societies affiliated to the WECHM, with each required to submit an annual report detailing its membership, the number of meetings held, and the amount of money raised during the year.

Nevertheless, the home missionary enterprise did not depend solely upon a sense of duty and obligation among church members to donate. Nineteenth-century charity and religious fundraising was a crowded marketplace, with hundreds of venerable organisations each with a noble cause that tugged at the faith, hope, and charity of believers. Donors could decide to give their financial contribution to foreign missions or missions to freedmen, or to the myriad of other religious organisations such as the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society. Though congregational donations remained important in financing home missions, home missionary fundraisers increasingly employed a diverse array of strategies and methods to secure donations in this competitive environment. These went beyond appealing to the duty and obligation of believers, with fundraisers offering a variety of experiences and material objects to donors in return for financial donations such as missionary socials, mite boxes, birthday boxes, certificates representing a ‘brick’ in a missionary chapel, photos of missionary sites, and pieces of Puebloan pottery. For a $25 contribution missions in the Pueblos, donors would receive a ‘a photograph of one of the Pueblos,’ whilst for a $50 donation a piece of Puebloan pottery would be dispatched (Jackson Citation1878). Or if a Sabbath School or missionary society raised $250 a year for home missions they were ‘entitled to a missionary of their own, from whom they may receive quarterly reports’ (PCUSA Citation1881).

The importance of this ‘material exchange’ between fundraisers and donors in religious and charitable organisations is recognised in broader scholarship. In the charity market in late-nineteenth century Britain, for example, fundraisers increasingly appealed to supporters’ habits of consumption through material objects, charity ‘bazaars,’ and charitable purchases (Roddy, Strange, and Taithe Citation2019). Underlining the different modes and strategies used by the Board of Home Missions was the desire to substantiate the connection between donors and home missions. Through these material objects missionary fundraisers hoped to narrow the divide between missionaries in the ‘mission-field’ and supporters at home, evoking a strong emotive and personal relationship between the donor and the mission. Missionary leaders discussed how these fundraising strategies could encourage ‘a personal interest in the man [i.e. the missionary] and his work,’ and hoped that they would make congregations, donors and churches ‘consider that missionary its own’ (PCUSA Citation1887, 9). They recognised that the routinised model of monthly schedules could dint the lustre and the ‘romance’ of missions, with supporters distant from the work with little sense of autonomy over their donation, where it went, who it supported or its impact. With these various pieces of missionary material, they sought to inform supporters about the impact of their donation and to awaken a personal interest in the endeavour, which they hoped would be continually renewed by further financial donations. Though the Presbyterian home missionary enterprise was financed through a system of professionalised accounting and administration, in soliciting funds from church members, missionary fundraisers sought to appeal to the hearts and emotions of supporters. Beginning in October 1878, Presbyterian home missionary fundraisers added to this repertoire of material objects by offering certificates of stock for donations towards missionary chapels and schoolhouses in the American West. However, before examining the emergence and development of this fundraising modality, I consider the broader social and religious attitudes towards investor capitalism in Gilded Age America, and the clear sense of moral ambiguity many American Protestants felt towards investor capitalism.

‘Our most liberal and honorable christian men’: making investor capitalism respectable in the late-Nineteenth century

The marketing of certificates of stock in home missionary fundraising represented the budding fascination with investor capitalism in the late-nineteenth century. The era saw a change in societal norms that popularised the market in everyday economic life. ‘You do not sell your cheese without knowing the latest quotations from the New York and Liverpool markets,’ as Rev. Henry Kendall, the Secretary of the Board of Home Missions, wryly remarked in one sermon (Kendall Citation1881, 18). Many ordinary Americans gained a familiarity with stock and bond holding through the American Civil War. During the conflict, the U.S Treasury orchestrated two major bond drives that mass-marketed over $1.2 billion dollars’ worth of U.S. Government bonds (Thomson Citation2016). After the conflict, the interest in financial markets and bond holding continued. Newspapers devoted columns to the latest trades and trends, and reported stories of the ‘bulls and bears’ of Wall Street, whilst popular guides and explainers sought to offer the tricks of the trade to aspiring investors. The famed financiers of the Gilded Age were household names, and their lives provided plot twists and villainy that would animate any novel. Americans were increasingly ‘emotionally invested’ in these financial developments (Knight Citation2016, 5). As historian Julia Ott (Citation2011, 17) explains, though the ‘financial securities markets’ may not have elicited ‘mass participation’ in the late-nineteenth century, they ‘certainly fanned mass fascination.’

Ambiguity characterised popular Protestant attitudes towards investor capitalism, as they weighed the growing ubiquity of investor capitalism in the lives and purses of church donors against its unflattering association with financial scandals and gambling. Though acknowledging its potential to be manipulated for fraud and embezzlement, Presbyterian leaders helped to legitimise investor capitalism as a respectable vocation for American Protestants. This was evident in the philanthropy and generous donations given by financiers, traders and stockbrokers who used their wealth to help fund church enterprises.

Historians have claimed that American Protestants said little about ‘the morality or wisdom of investments’ (Smith Citation2000), however there is bountiful evidence in published sermons and commentary in religious newspapers and periodicals to suggest otherwise. Investor capitalism was, in fact, one of the recurring victims of pulpit harangues as newspapers regularly featured ‘whole columns of sermons and tirades preached against Wall Street by minsters and moralists,’ as one paper complained (Omaha Daily Citation1890). The lax regulation of nineteenth-century investor markets provided ample opportunity for fraud, speculation and dubious investment schemes for the sake of profit, and hence abundant examples for ‘ministers and moralists’ to condemn. Repeated stock market panics and crashes in 1869, 1873 and 1893, which resulted in economic downturns, price rises, factory closures and job losses soured public attitudes towards the financial world of Wall Street (White Citation2017, 260–273, 791; Cashdollar Citation1972, 229–233). ‘[M]any men and women,’ as the Baptist The Examiner and Chronicle admitted, simply regard Wall Street ‘as an assemblage of unmitigated swindlers, who live by preying upon each other and upon the community’ (Examiner and Chronicle Citation1872, 1). Many Protestant ministers thus added their bluster to an already unpopular subject.

Repeated stories of financial scandals soured attitudes towards investors. The finances of banks, saving companies, insurance firms, trust funds, charities and churches were not immune from embezzlement, often victims of devious investment schemes. Such was the prevalence of these cases that the popular Presbyterian minister, Rev. Thomas DeWitt Talmage described the era as the ‘Age of Swindle’ (Atlanta Constitution Citation1888). Even the funds of home missionary societies were tarnished by the financial scandals of investor capitalism. Members of the Reformed Church in the United States were shocked when it was revealed that the treasurer of the denomination’s Board of Domestic Missions had embezzled $25,000 of donations (New-York Tribune Citation1886). It transpired that the treasurer, an otherwise ‘sharp and shrewd business man,’ had regularly been using the funds of the missionary board as capital for speculative investments, quietly returning the funds with no-one the wiser (New York Times Citation1886). But on one occasion the investment went sour and he could not repay the estimated $25,000 he had ‘borrowed’ from the Boards’ coffers. The Methodist Church was similarly embarrassed when a wealthy ‘wizard’ of Wall Street and noted church benefactor, Daniel Drew, had to declare bankruptcy, voiding his generous endowment of over $250,000 to a Methodist Seminary in Madison, New Jersey, named after himself. In a complex financial scheme, Drew had retained full control of the fund and paid the Drew Seminary a yearly interest sum (New York Observer and Chronicle Citation1876). To some Drew ‘was a genius,’ who for over thirty years played the market, employing every trick and trade under the sun, and ‘accumulated an immense fortune’ (Sun Citation1879). But to others his high-risk investment strategy was nothing short of gambling (New York Times Citation1879). With the Panic of 1873, the values of his stock holdings plummeted, his debts soared, and he declared bankruptcy in 1876. The Drew Seminary endowment was not protected from his losses and was ‘scattered among his creditors or hopelessly lost in speculation’ (Sun Citation1879). Such financial scandals and embarrassments reflected badly on the Protestant churches. ‘All sects have contributed to swell the ranks of the dishonest,’ explained an editorial in the New York Times: ‘ … the preachers of morals and the preachers of faith – have each and all furnished recruits to the ignoble army of forgers, [s]peculators, violators of trust funds, and all those whose frauds have cursed and disgraced the country for some years past’ (New York Times Citation1877). This public moral discourse created an ethical dilemma for Christians who aspired to seek their fortunes on the stock exchange.

Protestant leaders were aware of the devious behaviour that the media and public associated with investor capitalism, and occasionally raised strong critiques from their pulpits. A common theme was that the value of stocks, shares and bonds was illusionary. Critics pointed to the Book of Genesis, and the decree that it was by ‘the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread,’ not in trading stocks and shares in Stock Exchanges (Thompson Citation1873, 1). The Rev. Charles L. Thompson, minister of Fifth Presbyterian Church of Chicago, and in later years Secretary of the Board of Home Missions, voiced this complaint in the wake of the Panic of 1873:

To-day many hundreds will gather, not only in the Stock Exchange, but in all our great cities, to make fortunes out [of] other people’s losses, to trade in fictitious values, and to buy and sell pieces of paper that have no real value and never will have. (Thompson Citation1873, 1)

However, though often the subject of pulpit ‘tirades’, many American Protestants shared in the popular fascination with investor capitalism and it received an equal amount of good press as bad in the late-nineteenth century. The religious weekly paper the New York Evangelist disseminated market news and updates in its regular column dedicated to ‘Money and Business,’ along with advertisements from banking houses and brokerage firms (see e.g. New-York Evangelist Citation1870, Citation1872), as did the Chicago-based paper, The Interior, which regularly provided readers with the latest updates on stock market trends (The Interior Citation1872, 8). Popular preachers solicited for their opinions on investor capitalism responded in the affirmative. The Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, for example, was an outspoken advocate of ‘the legitimacy and commercial righteousness’ of investor capitalism (New York Tribune Citation1882). In response to calls for regulation of investor markets, he advocated that Wall Street ‘should regulate itself,’ as high-risk speculative traders would inevitably run out of good fortune and cautious conservative investors would prevail. Rev. Theodore Cuyler, minister of the prominent Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn, assured his congregants that ‘[t]here are brokers who are solid, healthy, consistent Christians’ (New York Evangelist Citation1869).

Protestant supporters of investor capitalism maintained that it had a respectable and virtuous form, despite its sometime odious association with fraud. Some ministers went into specific details about the mechanisms and workings of the stock market. Rev. Talmage, for example, explained to his congregation that investment, speculation and high finance was essential to the modern economy; to rid the economy of all form of speculation would bring it to a standstill (New York Herald Citation1877). Just as the farmer sows his seed in the expectation of a harvest in the future, so too does an investor place their money in the stock-market on the expectation of a future return. However, this kind of rationale was rare. Most often, ministers (Talmage included) emphasised that investors and brokers were respected church members and generous supporters of church causes. Though critics pointed to the financial scandals and declared those engaging in investor capitalism guilty by association, to supporters the respectability of investors was proved by their association with the church and the large sum of their donations. The line separating a respectable investor and a gambler was drawn by philanthropy and good works. When the Rev. William M. Taylor, minister of the Congregationalist Broadway Tabernacle in New York, launched ‘a severe attack on the gentlemen who do business in Wall street’ as ‘stockjobbers,’ many were quick to defend the slighted traders (New-York Evangelist Citation1873). The Baptist denominational paper, The Examiner and Chronicle, cautioned ministers to refrain from such harsh denunciations of brokers and investors:

These men, scandalized as stockjobbers, are amongst the most honorable and liberal men of the world. They make the largest donations to theological and collegiate education; they build costly churches, and pay the heaviest portion of the expenses. They are the elders, deacons and trustees of religious society. (New-York Evangelist Citation1873)

But what was it about church membership that so afforded investors such respectability? It is clear that Protestant ministers did not want to alienate the stockbrokers and investors who were members of their churches. The comment by the Evangelist about ‘our most liberal and honorable Christian men’ was descriptive of a reality of church membership in places like New York City, Philadelphia and Chicago. Men such as Robert Lenox Kennedy, John Stewart Kennedy and Jacob D. Vermilye were not just active church members, but generous donors in both life and death. Furthermore, churches, seminaries and missionary societies were themselves active in investment capitalism, often holding financial reserves in a portfolio of diverse investments. The Board of Home Missions established its own ‘Permanent Fund’ with a bequest of $6,000 in U.S. Government Bonds in 1868 (PCUSA Citation1871, 35). By the turn of the century the Fund amounted to nearly $400,000 dollars with a diverse portfolio of commercial investments and government bonds (PCUSA Citation1899, 66–67).

‘In the printers best style’: missionary certificates of stock

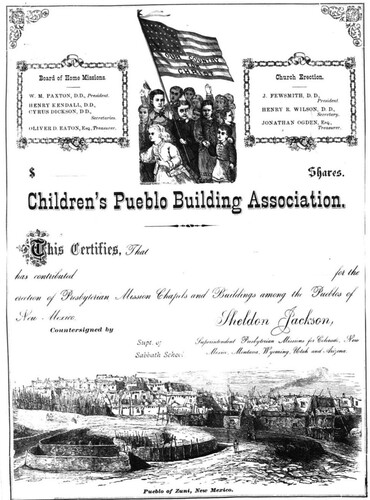

In the October 1878 edition of the Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, a monthly home missionary magazine, a brief notice appeared heralding the founding of ‘The Children's Church Building Stock Company’ (Jackson Citation1878). This new venture proposed to form ‘a great stock company of all the Presbyterian children to build mission premises so that the Indian and Mexican and Mormon children can have Christian teachers who will tell them about the Savior.’ Noting that this strategy of forming ‘joint-stock companies’ was used by ‘[w]ealthy men … to build railways and manufactories,’ the notice announced that this new stock company would democratise stock holding by offering certificates of stock in missionary premises at the more affordable price of ‘ten cents a share.’ Marketed to children, these certificates of stock utilised the existing institutional structures of Sunday Schools in Presbyterian Churches (which had an estimated 600,000 children on their rolls) to promote and administer this new fundraising endeavour. ‘Parents, [Sunday School] teachers and superintendents should keep a record of names of those subscribing to the stock,’ the article instructed (Jackson Citation1878). The certificates of stock issued in return for these 10c donations were simply decorated, utilising existing motifs and illustrations from the Rocky Mountain Presbyterian (see ).

Figure 1. Certificate of the Children’s Pueblo Building Association, Sheldon Jackson Scrapbook, Vol. 64, 119. Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The notice in the Rocky Mountain Presbyterian marked the advent of a new mode of home missionary fundraising: the issuance of certificates of stock in return for donations to fund missionary premises in the American West. Ministers were not simply using the rhetoric of investor capitalism (discussed further below) – missionary fundraisers were actually issuing ‘shares’ to fund specific building projects. The use of this mode of home missionary fundraising within the Presbyterian Church was the idea of Rev. Sheldon Jackson, Superintendent of Presbyterian Home Missions in the American West and editor of the Rocky Mountain Presbyterian. It proved popular: letters soon arrived from Presbyterian Churches across the country requesting certificates of stock. $5.17 was promptly donated from the Sabbath School of Shenandoah Presbyterian Church in Pennsylvania in return for 46 certificates (Kolb Citation1878). For a $15 donation from the Sabbath School of the Presbyterian Church of Canton, Ohio, eighty certificates were requested ‘to supply these little contributers [sic],’ as the minister wrote (Park Citation1878). Even for small donations of a dollar or less, certificates were issued (Cairns Citation1878). By the beginning of January 1879, after less than four months, Rev. Jackson’s new fundraising scheme had raised an estimated $575 dollars for Presbyterian mission sites, the equivalent of $14,600 in today’s money, all through Sunday School groups (Reigart Citation1879).

After the success of Rev. Jackson’s fundraising campaign, fellow Presbyterian missionary, John McCutcheon Coyner, sought to replicate this through issuing certificates of stock to fund further construction in Salt Lake City, Utah. Coyner was the Principal of the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute, a higher educational college run and supported by the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions. As he explained in the Rocky Mountain Presbyterian:

It is thought best, in raising the $8,000 needed for our work in Salt Lake City, to issue stock, each share being ten cents. The certificates of stock are gotten up in a neat, business-like style, and any one can take a certificate for as many shares as he wishes. (Coyner Citation1880a, 76)

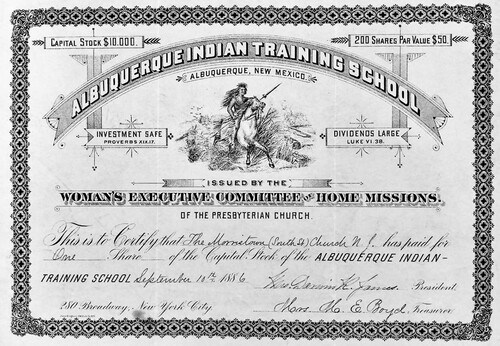

Not only were these certificates of stock in a ‘business-like style’, they also materialised a spiritual commitment of donors, acting as reminders ‘in golden characters’ for donors to pray for this ‘most important enterprise,’ alongside the financial and other ‘effort’ needed in home missionary work. What was inscribed in these ‘golden characters’ we do not know, but they might have been Biblical verses as were used in later certificates of stock in the Albuquerque Indian Training School from 1886 (). What is clear is that they were different from Rev. Jackson’s certificates of stock fundraising campaign. Rev. Jackson’s certificates made no references to prayer and were not marketed as having any lasting significance as reminders to support the mission. Instead, the adverts emphasised immediacy to interest (and occupy) Sunday School children. Nevertheless, both fundraising campaigns focused upon children and youth as their target audience, as the small fiscal amounts of 10c and 25c signify.

The certificate of stock substantiated the relationship between the donor and the cause of home missions. The donor was now a stakeholder, with a vested interest in a particular missionary building and project. The ‘investors’ in these missionary premises were likely never to see or visit the building they held shares in, but they would receive updates through missionary periodicals. If the donors were members of a Ladies’ Missionary Society that sponsored a missionary, they could even receive personal updates on their investment. Mary Lewis, a missionary teacher of the WECHM in Utah Territory, who was sponsored by the Ladies’ Missionary Society of Phelps, a small town in upstate New York, wrote to her sponsors about her visit to the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute:

This morning she [a fellow Presbyterian missionary] took us to her room and over the [Salt Lake Collegiate] building, in which I am so glad you have ‘shares’. … I know that the money … has been well invested and that our Presbyterian Society has been privileged in being permitted to aid in this, dear ones in Phelps, and I am sure you will be glad to continue this blessed mission. (Lewis Citation1881)

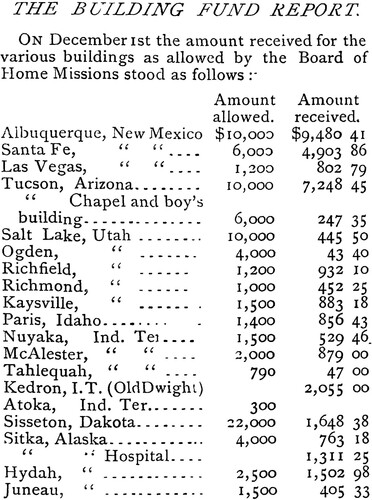

The use and significance attributed to these certificates of stock developed further with the Woman’s Executive Committee of Home Missions (WECHM), when they began using this method to fund numerous building projects from the mid-1880s. In July 1886 the WECHM established a new building fund to raise money to build missionary schools and chapels, mostly in the American West (PCUSA Citation1886). Each of these building projects had a set fundraising target and were presented as an opportunity for donors to ‘invest’ in. Each certificate of stock issued in return for a donation was tied to a particular missionary premises, whether that be, for example, the Albuquerque Indian Training School, the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute in Utah Territory, or the Sitka Industrial Training School in Alaska Territory. The certificates were printed by John Bingham, a respected stationer in New York City, whose shop and business premises were located on 84 Wall Street, Manhattan – just four blocks down the road from the New York Stock Exchange (American Stationer Citation1888). Donors were kept up to date on the fundraising targets and amounts received through a building fund report published in the WECHM periodical, Home Missions Monthly ().

Figure 2. ‘The Building Fund Report,’ Home Missions Monthly, 2:3 (January Citation1888), 64.

The fiscal amounts of the WECHM certificates of stock were considerably higher than the 10 cents per share in Rev. Jackson’s scheme and the 25 cents per certificate for the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute. A ‘whole’ share in a mission building could be received for a donation of $50 dollars or $25 for a ‘half.’ If those amounts were too great a ‘brick certificate,’ corresponding to one brick in the missionary premises, could be secured for a 10c donation. Without access to a financial ledger that recorded donations to the Building Fund, it is impossible to judge who made these ‘investments.’ The certificates of stock distributed by the WECHM may have been issued to individual donors, or collectively to churches or missionary societies who had raised the required sum. is an example of a share certificate in Albuquerque Indian Training School issued to the Presbyterian Church in Morristown, New Jersey. Given that the fiscal amount for a whole certificate of stock was $50, which roughly equates to $1,340 in today’s money, it is likely that these certificates of stock were held collectively by missionary societies as well as individual supporters. By marketing these certificates for these larger sums, the missionary fundraisers of the WECHM were seeking to expand the pool of supporters they could appeal to. The certificates from the earlier campaign by Jackson were squarely targeted at children, young people and Sunday School groups. Though Jackson was successful with that target audience there was a clear limit to the amount of money that could be raised from financially dependent children and young people. The WECHM certificates of stock campaign sought to retain the interest of the young with the 10c ‘brick certificates’ but also directly targeted adults for larger donations of $25 and $50, both collectively within missionary societies and individually.

Figure 3. Certificate of Stock for Albuquerque Indian Training School, issued by the Women’s Executive Committee of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church. RG305 Woman's Executive Committee of Home Missions, Box 2, Folder 80, Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The WECHM certificates of stock were also designed in a way that more emphatically materialised the donor’s sense of involvement in a wider missionary movement and hopes for an improved spiritual life. Drawing on Vivian Zelizer’s influential work on the multiple meanings of money, scholars have focussed upon the rich and complex meanings of money, challenging the notion that ‘a dollar is a dollar is a dollar’ (Morduch Citation2017). As Zelizer (Citation2017) demonstrates, individuals ‘earmark’ their financial resources, attributing diverse values, uses and significance to it. Money and its usage are embedded in a web of social relationships, emotions, obligations and commitments. The ‘missionary stocks’ are exemplars of this rich meaning of money in the lives of ordinary people.

The certificate of stock was an object to be received, owned and displayed, materialising the donor’s participation in the broader missionary movement. As Hillary Kaell (Citation2017, 118) explains in her study on the use of mite boxes in missionary fundraising, these kind of fundraising objects ‘materialised relationships that were meant to be present, but were not tangible,’ functioning as ‘physical points of contact between people at home and abroad, the living and the dead, and humans and God.’ In the same way, these certificates of stock materialised donors’ relationship and sense of commitment and devotion to the cause of Christian missions. Supporters of nineteenth century missionary societies believed themselves to be part of a global movement that transcended national boundaries – and even those between heaven and earth – and was ushering in the ‘Kingdom of Christ’ on earth. By displaying and representing a donors’ financial contribution, these certificates materialised that sense of participation in this broader movement, connecting the members of the Presbyterian Church in Morristown, New Jersey who had ‘invested’ in the Albuquerque Indian Training School (), or the ‘Ladies of Phelps’ in Upstate New York who had ‘invested’ in Salt Lake Collegiate Institute, to a global missionary phenomenon of which supporters believed themselves to be a part.

In their production, the certificates issued by the WECHM consciously alluded to a deeper spiritual significance of the donation. At face value the imagery of the WECHM certificates of stock imitated commercial counterparts. The central motif of the Albuquerque Indian Training School certificate, a representation of a Native American on horseback, was comparable to the motifs of business and commercial stock certificates, such as the Oregon and Transcontinental Certificate shown in . The WECHM certificate also used the language of commercial stocks, employing the term ‘Capital Stock’ to represent the total $10,000 fundraising target for the Albuquerque Indian Training School, and the phrase ‘200 Shares Par Value’ to represent the total number of shares available. Yet there is an obvious hint in the WECHM certificate that the investment was not for a financial return in the references it makes to the Biblical verses Proverbs 19:17 and Luke 6:38. Unlike so many other investment options in the late-nineteenth century, the certificate assured stakeholders that their ‘Investment [was] Safe.’ Why could the WECHM promise such security? Because the money donated was ‘lendeth unto the Lord,’ as Proverbs 19:17 reads, reassuring supporters, ‘that which he hath given will he [the Lord] pay him again.’Footnote2 Though the donor would receive no financial dividend on their investment in the Albuquerque Indian Training School, their ‘Dividend [would be] large.’ Their generosity in supporting the ‘cause of Christ’ would not be forgotten. As Luke 6:38 reads: ‘Give, and it shall be given unto you.’Footnote3

‘Give, and it shall be given unto you’: donations as an investment and as worship

The WECHM was not alone in using the language of investor capitalism to raise money. This rhetoric of ‘return’ and ‘investment’ was part of a broader rhetorical shift in how religious fundraisers framed financial donations within the Presbyterian Church of the late nineteenth century. Behind this rhetoric was a more meaningful change in how financial donations were understood. Increasingly, religious fundraisers framed financial donation as part of a devoted spiritual life and integral to the worship of their God. In donating their monies to the missionary enterprise, supporters were assured of an – often elusive – spiritual ‘return’ on their ‘investment.’ As the WECHM certificate of stock in the Albuquerque Indian School alluded to, ‘Give, and it shall be given unto you.’

In a series of lectures on The Religious Use of Property, the President of the Board of Home Missions, Rev. John Hall, reflected on religious fundraising in an ‘age [that] magnifies material success’ (Hall Citation1883). He described how the late nineteenth century provided ‘unexampled’ opportunities for the activities of religious organisations, but also how this was matched by ever growing financial need (Hall Citation1883, 3–4). ‘No Tract Society, or Bible Society, or mission enterprise can be maintained without money,’ he noted; securing a regular source of revenue was vital. To encourage donations, fundraisers should highlight the ‘moral and spiritual benefits’ of donating to religious causes. To explain his point the Rev. Hall used an interesting analogy:

Men often buy and lay aside stocks that are cheap now, because paying no dividend, but of which they believe ‘that they will come up.’ They are not certain when, but they are willing to wait. Faith in Jesus Christ when it gives does not look for dividends now, but they will come, and often sooner than from earthly investments. It is not laying out but laying up. The christian [sic] [in donating] is making – if in the right spirit – an investment in a new world which is sure to pay him a hundred fold. (Hall Citation1883, 30)

The framing of donation as an ‘investment’ was not just a peculiar analogy used by the President of the Board of Home Missions. It was symptomatic of how home missionary fundraisers used the rhetoric of investor capitalism – ‘investments’, ‘dividends’, ‘stocks’ and ‘shares’ – in Presbyterian missionary periodicals and related papers to solicit donations to home missions. Religious fundraisers portrayed the United States in the late nineteenth century as awash with money. This money, however, was stored in the wrong place. Just as keeping money in a savings bank starves the economy of capital to fund commercial investments, so too the ‘rust of hoarded wealth’ was starving the home missionary enterprise (James Citation1887, 199). ‘Bank vaults are said to be groaning with the weight of treasure,’ wrote one home missionary in the Presbyterian Home Missionary, ‘which is thought to be safer where it is unproductive than sent forth in the peril of its life’ (Cleland Citation1885, 30). Those individuals that sought to invest their capital faced slim pickings. ‘Government bonds yield but moderate returns,’ the missionary continued; ‘railroad stocks, owing to sharp competition, are less productive.’ The answer to this dilemma was ‘an investment’ that has ‘yielded the largest premiums’ – Presbyterian home missions. As one Presbyterian minister characterised it, the Christian God was calling on people to:

Put your money into My bonds. I have different classes of them – education bonds, hospital bonds, orphan asylum bonds, missionary bonds. I have different denominations, from one dollar up to millions. All the bonds issue[d] in my name I indorse and become responsible for. (Highland Weekly Citation1885, 4)

This ambiguity was a conscious decision of the PCUSA’s missionary fundraisers. It was not unheard of for American Protestant ministers to promise material blessing to donors in the here and now. The famed Brooklyn Pastor, Rev. Thomas DeWitt Talmage, advocated an early incantation of the ‘prosperity gospel’ (see Bowler Citation2013). He encouraged supporters to donate funds to ‘the cause of Christ’ as a remedy for their own personal and financial problems (Talmage and Post Van Norstrand Citation1888, 418): ‘You tell me that Christian generosity pays in the world to come, I tell you it pays now, pays in hard cash, pays in government securities.’ Though this kind of rhetoric was an option for Presbyterian home missionary fundraisers, they shied away from promises of ‘hard cash’ and ‘government securities’ in return for ‘investments’ in church causes. The only return the home missionary fundraisers could promise was that which was beyond price.

The religious value attributed to these ‘investments’ was part of a broader change in how late-nineteenth century Protestants understood financial donations to church and religious organisations. During the 1870s, clergy and laymen debated how the Presbyterian Church could improve the fundraising for its benevolent and missionary activities. Presbyterian newspapers and journals regularly featured debates and proposals between proponents of new financial and fundraising practices (Irving Citation1872, 351; Ellinwood Citation1873, 1). These debates were broad in scope and precise in detail, but their most significant outcome was the reframing of financial donations to the church and missionary enterprises as worship.

Participants in this debate agreed that the church’s fundraising could not be dependent upon the occasional stirs of conscience of congregants but needed to be based upon a consistent and regular strategy for fundraising. The generally agreed solution was to institute weekly collection of funds during Sunday services at Presbyterian Churches, integrating financial donations as part of the ritual of worship. Though a feature of worship services in Roman Catholic churches, in American Protestant churches, the collection of funds during a service was not a practice widely adhered to. Protestant churches typically received their income from rents of pews, financial support from wealthy Trustees, and occasional fundraising events (Hudnut-Beumler Citation2007, 54–56). In the late-nineteenth century, the practice of a ‘Weekly Offering’ during a religious service became an increasingly widespread feature in American Protestant services. The Secretary of the Board of Home Missions, Rev. Henry Kendall, described with wonder how this practice was ‘a movement which has sprung up almost simultaneously among all denominations in this country, and even in other countries’ (Kendall Citation1873, 6.).

This development may seem quite inconspicuous, but it represented a significant shift in thinking about religious fundraising. Creating a space during a church service for the purpose of appealing for and collecting financial donations from congregants – typically begun by a prayer – transformed the practice of financial donation into worship. As one editorial put it, it ‘Christianizes giving’ (New-York Evangelist Citation1875). No longer were financial contributions to the church and its missionary enterprise part of the formalities of church membership; regular financial giving was now an integral part of the Christian life. As one Presbyterian minister explained, ‘[g]iving to the Lord with a devout spirit is worship, as distinctly required of the believer, in its time and place, as prayer or praise, or reading the word’ (Hand Citation1872, 341).Footnote4 In framing financial donations as worship, as an offering to God, religious fundraisers gave the financial donation a spiritual significance. Though the material utility of the donation was limited by its fiscal amount, it had a significance that could not be quantified in dollars and dimes.

Conclusion

More than just paper ephemera, the increasing use of stock certificates and financialised language by American Presbyterians demonstrates not just how much religious organisations have adapted to the prevailing economies that surround them in order to survive and flourish, but also the extent to which in doing so, they have in turn impact the perceived morality of those economies. The Presbyterian home missionary enterprise was actively engaged in investor capitalism, from the portfolio of commercial investments of the Board of Home Missions to the explicit language of ‘investments’, ‘dividends’, ‘stocks’ and ‘bonds’ used in fundraising appeals. By emphasising the spiritual returns donors would receive by ‘investing’ their donations, home missionary fundraising endowed the fiscal transaction with spiritual significance, something that resonated with the broader reframing of financial donations as worship within the Presbyterian Church. The emergence and development of this mode of fundraising came at a time when investor capitalism had a morally ambiguous reputation among many American Protestants, with its connotations of gambling and its association with financial fraud in the Gilded Age. The development of certificates of stock in home missionary fundraising represented one of the ways attitudes towards investor capitalism changed, becoming increasingly accepted as a respectable economic practice for American Protestants in the late nineteenth century.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrew Short

Andrew Short recently completed his PhD at University College London (UCL).

Notes

1 All estimated equivalents are taken from Williamson Citation2018.

2 The full verse of Proverbs 19:17 (KJV) reads, ‘He that hath pity upon the poor lendeth unto the LORD; and that which he hath given will he pay him again.’

3 The full verse of Luke 6:38 (KJV) reads, ‘Give, and it shall be given unto you; good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over, shall men give into your bosom. For with the same measure that ye mete withal it shall be measured to you again.’

4 The practise of the ‘Weekly Offering’ or ‘Sabbath Offerings’ was formally standardised in 1886, when the General Assembly of the PCUSA agreed to a revision in the denomination's Directory of Worship to include a new section entitled ‘Of the Worship of God by Offerings.’ See PCUSA Citation1896, Directory for Worship, Chapter VI, 76–77.

References

- American Stationer, 1888. New York’s Retail Trade. The American Stationer, 14 (20), 1119.

- Atlanta Constitution, 1888. “Talmage’s Sermon.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 12, 3.

- Balmer, R. H., and Fitzmier, J. R., 1993. The Presbyterians. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Banker, M. T, 1993. Presbyterian Missions and Cultural Interaction in the Far Southwest, 1850–1950. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Bowler, K, 2013. Blessed: A History of the American Prosperity Gospel. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bryer, R.A., 1993. The Late Nineteenth-Century Revolution in Financial Reporting: Accounting for the Rise of Investor or Managerial Capitalism? Accounting, Organizations and Society, 18 (7-8), 649–690.

- Cairns, S. H, 1878. “Cairns to John M. Reigart, 11 October 1878.” [Letter]. Sheldon Jackson Correspondence Collection Volume 8. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- Cashdollar, C. D, 1972. Ruin and Revival: The Attitude of the Presbyterian Churches Toward the Panic of 1873. Journal of Presbyterian History, 50 (3), 229–244.

- Cleland, H T. Jr, 1885. Where to Invest. Presbyterian Home Missionary, 14 (2), 30.

- Coyner, J. M, 1880b. “The Utah Column.” Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, June, 92.

- Coyner, J. M., 1880a. “The Utah Column.” Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, May, 76.

- Ellinwood, F. F, 1873. “The Question of Systematic Giving.” New York Evangelist, February 6.

- Engelbourg, S., and Bushkoff, L, 1996. The Man Who Found the Money: John Stewart Kennedy and the Financing of the Western Railroads. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press.

- Examiner and Chronicle, 1872. “The A B C of a “Corner”” Examiner and Chronicle (1865–1881), September 26, 1.

- Geisst, Charles R., 1999. Wall Street: A History. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goede, M. de, 2005. Virtue, Fortune, and Faith: A Genealogy of Finance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hall, J, 1883. Four Lectures on the Religious Use of Property. Cleveland: Leader Printing Co.

- Hand, Rev. H A., 1872. The Mode of Raising Funds for Church Work. The Princeton Review, 1 (2), 341.

- Hart, D. G., and Muether, J. R, 2007. Seeking a Better Country: 300 Years of American Presbyterianism. Phillipsburg: P&R Pub.

- Highland Weekly, 1885. “Lending to the Lord.” The Highland Weekly News, May 20.

- Hudnut-Beumler, J, 2007. In Pursuit of the Almighty's Dollar: A History of Money and American Protestantism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Irving, D, 1872. Systematic Beneficence in the Presbyterian Church. Princeton Review, 1 (2), 351–370.

- Jackson, Rev. S, 1878. “The Children’s Church Building Stock Company.” Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, October 1, 2.

- James, Mrs. D. R, 1887. Address of the President at Omaha. Home Mission Monthly, 1 (9), 199.

- Kaell, H, 2017. Evangelist of Fragments: Doing Mite-Box Capitalism in the Late Nineteenth Century. Church History, 86 (1), 86–119.

- Kendall, Rev. H, 1873. “Systematic Beneficence.” The New-York Evangelist, April 3, 6.

- Kendall, Rev. H, 1881. A Semi-Centennial and Memorial Discourse. New York: Wm. C. Martin.

- Knight, P, 2016. Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalism in Gilded Age America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Koenig, S, 2016. Almighty God and the Almighty Dollar: The Study of Religion and Market Economies in the United States. Religion Compass, 10 (4), 83–97.

- Kolb, F, 1878. “‘Kolb to John M. Reigart, 10 October 1878.’ [Letter].” Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. Sheldon Jackson Correspondence Collection Volume 8.

- Lee, S., and Sinitiere, P. L, 2009. Holy mavericks: evangelical innovators and the spiritual marketplace. New York: New York University Press.

- Lewis, M, 1881. “‘Lewis to the Ladies Missionary Society of Phelps.’” [Letter]. Held at Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. RG305.

- Longfield, B. J, 2013. Presbyterians and American Culture: A History. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- McCleary, R. M, 2011. The Economics of Religion as a Field of Inquiry. In: R. M. McCleary, ed. The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 3–36.

- Moore, R. L, 1995. Selling God: American Religion in the Marketplace of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morduch, J, 2017. Economics and the Social Meaning of Money. In: N. Bandelj, F. F. Wherry, and V. A. Zelizer, eds. Money Talks: Explaining How Money Really Works. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 25–38.

- New York Observer and Chronicle, 1876. “Fictitious Donations.” New York Observer and Chronicle. March 23, 90.

- New York Times, 1877. “Fraud and the Churches.” The New York Times, October 14, 6.

- New York Times, 1879. “Death of Daniel Drew.” The New York Times. September 19, 5.

- New York Times, 1886. “His Trust Betrayed.” The New York Times, May 22, 5.

- New York Tribune, 1882. “Three Clergymen Heard.” New York Tribune, December 17, 10a.

- New-York Evangelist, 1869. “Gambling in Gold and Stocks.” The New-York Evangelist, October 7, 1.

- New-York Evangelist, 1870. “Money and Business.” The New-York Evangelist, June 16, 8.

- New-York Evangelist, 1872. “Money and Business.” The New-York Evangelist, February 29, 8.

- New-York Evangelist, 1873. “The religious Press.” The New-York Evangelist, January 9.

- New-York Evangelist, 1875. “The weekly Offering.” The New-York Evangelist, May 6.

- New-York Evangelist, 1877. “Brooklyn Tabernacle: Wall Street from a Christian Standpoint.” The New York Herald, April 9, 8.

- New-York Tribune, 1886. “Mission Funds Misused.” New-York Tribune, May 22, 1.

- Noll, M. A, 2002. Introduction. In: M. A. Noll, ed. God and Mammon: Protestants, Money, and the Market, 1790–1860. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–29.

- Nord, D. P, 2002. Benevolent Capital: Financing Evangelical Book Publishing in Early Nineteenth-Century America. In: M. A. Noll, ed. God and Mammon: Protestants, money, and the Market, 1790-1860. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 147–170.

- Omaha Daily, 1890. “Wall Street.” Omaha Daily Bee, September 8, 5.

- Ott, J. C, 2011. When Wall Street Met Main Street. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Park, Rev. J W, 1878. “‘Park to John M. Reigart, 21 October 1878.’” [Letter]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. Sheldon Jackson Correspondence Collection Volume 8.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1871. “First Annual Report of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church USA.” [Report]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1880. “Salt Lake institute”, Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, June, 86.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1881. Sabbath School. Presbyterian Home Missions, 10 (11), 394.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1885. “Fifteenth Annual Report of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church USA.” [Report]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1886. Our Building Fund. Presbyterian Home Missionary, 15 (7), 159.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1887. “Seventeenth Annual Report of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church USA.” [Report]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- PCUSA Board of Home Missions, 1899. “Ninety Seventh Annual Report of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church USA.” [Report]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society.

- PCUSA, 1896. The Form of Government, the Discipline, and the Directory for Worship, of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Church in the USA.

- Porterfield, A., Corrigan, J., and Grem, D. E, 2017. Introduction: The Business Turn in American Religious History. In: A. Porterfield, J. Corrigan, and D. E. Grem, eds. The Business Turn in American Religious History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–19.

- Reigart, J. M, 1879. “Reigart to Sheldon Jackson.” [Letter]. Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. Sheldon Jackson Correspondence Collection Volume 9.

- Roddy, S., Strange, J., and Taithe, B, 2019. The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, 1870–1912. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Salk Lake Herald, 1880. “New Mining Companies.” Salt Lake Herald, April 6.

- Smith, G. S, 2000. Evangelicals Confront Corporate Capitalism: Advertising, Consumerism, Stewardship, and Spirituality, 1880–1930. In: L. Eskridge, and M. A. Noll, eds. More Money, More Ministry: Money and Evangelicals in Recent North American History. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 39–80.

- Smith, G. S., and Kemeney, P.C, 2019. Introduction. In: Gary Scott Smith, and P.C. Kemeney, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Presbyterianism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1–7.

- Sun, 1879. “Stocks and Christianity.” The Sun, September 24, 2.

- Talmage, T. D. W., and Post Van Norstrand, F, 1888. Social Dynamite; or, the Wickedness of Modern Society, from the Discourses of T. De Witt Talmage. Newark, OH: S. Allison.

- The Interior, 1872. “Markets.” The Interior, August 1, 8.

- Thompson, Rev. C. L., 1873. “Chicago Correspondence.” Rocky Mountain Presbyterian, November 1, 1.

- Thomson, D. K, 2016. Like a Cord Through the Whole Country’: Union Bonds and Financial Mobilization for Victory. Journal of the Civil War Era, 6 (3), 347–375.

- WECHM, 1886. “‘Circular.’ [Pamphlet].” Held at: Philadelphia: Presbyterian Historical Society. RG305.

- WECHM, 1887. Golden Opportunities. Home Mission Monthly, 1 (12), 270.

- WECHM, 1888. The Building Fund Report. Home Mission Monthly, 2 (3), 164.

- WECHM, 1890. Grand Opportunities for Investment. Home Mission Monthly, 4 (3), 56.

- White, R, 2017. The Republic for Which it Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865–1896. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, S. H., 2018. “Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to present.” MeasuringWorth [online]. Accessed 29 November, 2018. https://www.measuringworth.com/uscompare/.

- Yohn, S. M, 1995. A Contest of Faiths: Missionary Women and Pluralism in the American Southwest. London: Cornell University Press.

- Zelizer, V. A, 2017. The Social Meaning of Money. New Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press.