ABSTRACT

Digital markets are regularly equated with digital capitalism. However, markets are also central features of longstanding other economic systems, such as the bush markets of Malaita, Solomon Islands, where saltwater and bush people have traded with each other for at least seven hundred years, if not longer. This article interrogates the digitization of this bush market system based on classically-conceived long-term ethnographic fieldwork that aims to develop a better empirical understanding of possibilities for diverse economic systems and markets in the digital age. We identify continuities between Solomon Islands-centric Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups and bush markets and demonstrate how these continuities strengthen other economic systems and values in the country. Despite their avid use of Facebook, Solomon Islanders are able to resist the industrial-capitalism embedded in platform design and to reaffirm social networks and a broader reciprocal moral economy.

Introduction

In urban and rural Solomon Islands, approximately 700,000 people are navigating rapid and radical digital transformations in their everyday lives that continue to be shaped significantly by longstanding economic systems centered on horticulture, fishing, hunting and gathering and culturally particular modes of social reproduction and reciprocal values. During long-term ethnographic research combining classic offline with online methods, we encountered digitizing economic practices that showcase new and shifting entanglements between these longstanding economic systems and globally dominant industrial-capitalism. For example, we asked when, why and how Solomon Islanders use Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups and we found that Solomon Islanders integrated the platform, above all, into a longstanding ‘moral economy’ that echoes Thompson’s (Citation1971) classic conceptualization of the term as an antithesis to industrial-capitalist ‘utility maximization’ and profiteering for individual gains. Solomon Islanders essentially use, and adapt, Facebook to accumulate wealth in a predominantly relational sense, to ‘[reproduce] relationships in which the transactors have become obligated to each other because of their past transactions’ (Carrier Citation2018, 30).

This article draws on our broader research (cf Hobbis Citation2021a; Hobbis and Hobbis Citation2022a; Citation2022b) on ‘the social expectations, emotional investments, and cultural transactions that create a shared understanding between [Solomon Islander] participants within an economic exchange’ (Green and Jenkins Citation2009, 214), to develop a better understanding of the continuities between Solomon Islands-centric Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups and longstanding bush markets. By exploring the presence of diverse digital and non-digital markets in Solomon Islands, we show how continuities between ‘buy and sell’ groups and bush markets challenge not only the industrial-capitalism of Facebook but also the presence of ‘brick-and-mortar’ style industrial-capitalist retail businesses. In other words, we demonstrate how Solomon Islanders’ everyday Facebook practices have given rise to new ‘digital bush markets’ that effectively push back against the broader, not just digital, presence of industrial-capitalism, as legacy and continued realization of colonialism, in the country.

Our Solomon Islands research accordingly contributes to a growing body of literature that identifies diverse means by which users of digital platforms may be able to resist ‘platform capitalism’ (Srnicek Citation2017) – the notion that platforms such as Facebook ‘commodify all social relations’ (de Kloet et al. Citation2019, 249) by virtue of their design – and the various forms of exploitation and intensified forms of exclusion that often accompany these digital transformations. Mark Kear, for example, detailed the emergence of what he calls ‘a moral economy of the serial crowd—a form of “crowd” in which individual acts are imagined to “scale up,” and together constitute collective acts of “self-protection”’ (Citation2022, 468; emphasis removed) against, among others, a new algorithmic ordering of individuals based on digital credit scores. Similar to Thompson’s (Citation1971) research on the bread riots in impoverished eighteenth century England, Kear (Citation2022) and others (e.g. Ettlinger Citation2018; Lynch Citation2020) have shown that possibilities for resistance exist within systems dominated by industrial-capitalism; and that these possibilities for ‘[disciplining] the market’ (Kear Citation2022, 474) are rooted in moral economic reasoning and practices that address inequalities in exchange systems based on collective values and assessments of what constitutes, for instance, fair pricing of particular goods and services.

We elaborate on these findings through a substantive empirical expansion: as suggested earlier, our research in Solomon Islands does not take place within a context dominated by industrial-capitalism. On the contrary, here industrial-capitalism has, despite the best efforts of, first, colonial officials (cf Cooper Citation1979) and more recently international development experts (cf Hobbis Citation2021b), remained at the margins of day-to-day economic life for a vast majority of the population, especially the approximately 80% of Solomon Islanders living in rural areas on communally and customarily-owned land. An empirical focus on Solomon Islands allows us to extend the existing debate to consider economic diversity beyond rather than within capitalism even when digital platforms are being used that have been designed and are operated, ‘for profit.’

Simultaneously, our detailed ethnographic case study of Solomon Islands digitizing markets facilitates the incorporation of extant other media histories into multidisciplinary debates on digital economic transformations that ‘may not have entered—at least in any comprehensive way—our narration of media history in the (Western) academy’ (Shome Citation2019, 2) despite the significance of these places for much critical economic theory. From the perspective of European-style farming and industrial-capitalism, places such as Solomon Islands are often dismissed as inconsequential ‘savage, untouched wilderness’ (Graeber and Wengrow Citation2021, 150). However, as essentially other from dominant political economic systems, these places have been key settings for social thought experiments in the past half millennia of Western thought. In-depth, classically conceived ethnographic research with, from a dominant perspective, other economies has long been a cornerstone for critical interventions in economic debates. They have often been considered through larger ethnological comparisons such as Polanyi’s (Citation[1944] 2001) critical processing of Malinowski’s work on the Kula Ring, Island Melanesia’s perhaps most famous exchange network; or Dave Elder-Vass’ (Citation2016) reading of Marcel Mauss’ ethnological treatment of ethnographic work to explore the role of the ‘gift’ in settings dominated by industrial-capitalism.

We contend that similar interventions, beyond just the reading of ‘old’ ethnographic and ethnological texts as ‘metaphors of political and cultural economy to social media’ (Dourish and Satchell Citation2009, 24), are urgently needed in debates on digital economic transformations (cf Hobbis and Hobbis Citation2022a). Doing so allows for developing better empirical understanding of possibilities for diverse economic systems and markets as more than subaltern forms of resistance against industrial-capitalism. Accordingly, we speak to digital economic studies provocatively. We insist on the inclusion of voices and experiences of people from the extreme margins of capitalism when digital scholars theorize what it means to be a digitizing human in a digitizing economy. In the context of this article, we specifically call for a more comprehensive engagement with digitizing markets, given, to echo David Hesmondhalgh’s observations, the relatively scarce attention paid to markets by scholars interested in the connection between media and communication and ‘the moral values informing particular economic arrangements and institutions’ (Citation2017, 206).

Digitizing (industrial-capitalist) markets

What is a market in the first place? Even though the concept is ‘inherently ambiguous’ (Bestor Citation2001, 9227; cf Herzog Citation2013), critical social scientists, from anthropologists to media scholars, have often drawn two fundamental distinctions (cf Appelbaum Citation2012). First, there are ‘empirical’ markets that can be found in physical spaces (Slater Citation1993) and that are contextually embedded in ‘social institutions … which encompass specific social, legal, and political processes that enable economic transactions but also extend far beyond them’ (Bestor Citation2001, 9227). In other words, there are marketplaces where participants’ activity is ‘focused on trade’ (Busse and Sharp Citation2019, 126). Such physical markets include Solomon Islands bush markets, ‘brick-and-mortar’ retail stores and digital, often platform-based marketplaces such as the aforementioned ‘buy and sell’ groups on Facebook or app stores like Google Play.

Second, there is the idea of the market principle, which does not need to be ‘localized in a marketplace’ (Plattner Citation1989, 171). This definition of markets covers ‘abstract ideas about a mode of exchange involving money and organized in accordance with supply, demand and price’ (Busse and Sharp Citation2019, 126); and it is, essentially, about the conceptual underpinnings of industrial capitalism. Exemplary in the digital age is Bill Gates’ vision for digital markets. Already in the 1990s, he envisioned a ‘new (digital) world of low-friction, low-overhead capitalism, in which market information will be plentiful and transaction costs low’ (Gates et al. Citation1995, 158) with moments of exchange and consumption being ubiquitous, invisible and practically, without place, everywhere (Watson et al. Citation2002). In this context of ‘ubiquitous commerce,’ the industrial-capitalist market principle is envisioned as dominant, subsuming all cultural differences in a world defined no longer by markets but by marketing (Watson et al. Citation2002).

Social scientists have regularly worked within the distinction between empirical and abstract (digital) markets. However, anthropologists and proponents of moral economy approaches more broadly have challenged its simplicity. Instead they have shown how ‘the “economy” reaches beyond commercial exchange to encompass a wider social framework of collective engagement with acts of production, consumption and regulation’ (Dourish and Satchell Citation2009, 23) including ‘a wide variety of social, political, ritual, and other cultural behaviors, institutions, and beliefs’ (Bestor Citation2001, 9227; cf Busse and Sharp Citation2019; Carrier Citation2018; Hardenberg Citation2017; Hesmondhalgh Citation2017).

Discussions surrounding ‘platform capitalism’ (Srnicek Citation2017) recognize this entanglement explicitly. By demonstrating how platforms perform ‘the structure of the venture capital investment which also backs it’ (Langley and Leyshon Citation2017, 3), platform scholars acknowledge the embedding of platforms in the sociocultural, industrial-capitalist, milieus of their designers. For example, by situating platform capitalism in broader industrial, managerial and organizational histories, Marc Steinberg (Citation2022) uncovers continuities between the assembly lines of automotive industries and the operational logic of digital platforms while establishing respective contextual embedding in the diverging and entangled encounters between automobile and platform theories in the US (Fordism) and Japan (Toyotism). Based on these contextual specificities, Steinberg rejects an analysis of economic behavior ‘as an autonomous sphere of human activity’ (Bestor Citation2001, 9227). Instead he underscores the socio-historical embeddedness of intrinsic complex connections between both, or, as we contend, perhaps better, all types of digitizing economies and markets.

Despite recognition of this entanglement, research on empirical digital markets has, consciously or not, often prioritized industrial-capitalist frames of markets, usually by taking for granted abstract capitalist definitions of what markets are in the first place. For example, David Hesmondhalgh describes the moral economy approach as requiring interrogation of ‘the effects of markets on media and culture’s capacity to contribute to human well-being or quality of life’ (2017, 204) without any discussion of markets as existing beyond and outside of industrial-capitalism. Instead, he introduces markets as a conceptual focus due to their perceived inherent entanglement with capitalism. Similarly, Robert Prey’s (Citation2020) examination of how Spotify operates as a platform-based marketplace inside of broader economic relations focuses exclusively on other capitalist markets, in his case, music, advertisement and finance markets.

An exception to an a priori correlation between markets and capitalism in digital studies is Anne Mette Thorhauge’s (Citation2022) research on Steam as a dominant gaming platform. Thorhauge provides intriguing insights into how the platform has flourished by providing multiple forms of marketplaces on the platform. These marketplaces include not only a ‘classic’ retail component (the sale and purchase of games) but also a seemingly not-so capitalist marketplace for trading items and a workshop-based market for creating and exchanging items for specific games. Yet, in the end Thorhauge (Citation2022) finds that these marketplaces are essentially capitalist as also all of Steams marketplaces fuel the monetarizing goals of the platform. In other words, her work seems to further affirm the embedding of platform marketplaces in the dominant, industrial-capitalist market principle.

By too often focusing on markets as deeply embedded in capitalist dynamics, we suggest that current debates on digitizing markets, including their colonizing tendencies (cf Couldry and Mejias Citation2019), are trapped in a ‘capitalist realism’ (Fisher Citation2009). To a large degree missing is research on the digital transformations of, primarily, longstanding other economies and their variously entangled empirical and abstract markets. We aim to push the debate on digital markets further by addressing this shortcoming. By empirically grounding our research in a focus on Solomon Islands bush markets, we explore to what extent, if at all, longstanding other, non-capitalist-industrialist marketplaces and principles exist and potentially even flourish on digital platforms that are, in principle and by design, industrial-capitalist. As Don Slater and Fran Tonkiss note, ‘imagining alternatives can be difficult given the density and obviousness of an apparently endless [industrial-capitalist] market “present”’ (Citation2001, 4). Still, a lot can be gained from stepping outside this obviousness as

taking account of the variety of market histories, of the different ways in which markets have been instituted and analyzed, brings into question the inevitability of market “imperatives”, the specific forms in which markets currently operate, and the role of market values within political rhetoric and economic ideology (Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001, 4).

A classically conceived ethnography of digitizing other markets

To uncover how platforms transform, or are transformed by, other or bush markets, our approach is essentially Malinowskian, both in its methodological perspective and its critique of economic universalisms. In Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Bronislaw Malinowski ([Citation1922] Citation1984) confronted deterministic stereotypes of economic actors in Western academic discourse, providing the necessary ‘concepts for considering the cultural specificity of the market model’ (Appelbaum Citation2012, 265). He did this through immersive, long-term fieldwork amongst a group of people who were, to him and his primary European and Euromerican audience, radically other in their engagements with everyday, and exceptional, life. Simultaneously, the people he worked with also offered ‘an allegory of the world economy’, with ‘a civilization spread across many small islands, each incapable of providing a decent livelihood by itself, that relied on an international trade mediated by the exchange of precious ornaments’ (Hart Citation2012, 169).

The critical difference, the big headline here, is that Malinowski argued that the people he studied did not engage in long-distance trade for the sake of commerce, for ‘buying cheap and selling dear’ (Hart Citation2012, 169). They might not even have been participating in trade at all, at least not as commonly defined in industrial capitalism. No more than Catholics would conceive of the exchange of communion for tithe as being commercial. Instead, Malinowski found that the islanders move objects between each other to maintain and strengthen an essentially highly complex sociocultural system. This system is based on obligations derived from the giving and receiving of gifts (cf Strathern and Stewart Citation2012) within a context of what Durkheim may call the collective effervescence of sensational social interaction.

Based on his longitudinal ethnographic research in Island Melanesia, Malinowski provided empirical evidence to refute the notion of ‘homo economicus’ or ‘Economic Man’ and a ‘rationalistic conception of self-interest’ ([Citation1922] Citation1984, 60) as the driving factor for exchange. In other words, Malinowski established empirical foundations for the critical, substantivist tradition in economic anthropology, sociology and related fields that, spearheaded by Karl Polanyi, challenged the universal applicability of Western economic theories while advocating for a socially-embedded understanding of economic values and practices (cf Dale Citation2010; Hann Citation2021).

Our agenda is to bring this tradition into the digital age by situating the adoption and adaptation of digital materials and technologies in their broader political, social and economic networks and to do so, explicitly, in a globally non-dominant other economic setting. By so doing, we build on existing ethnographies of the digital such as Jeffrey Lane’s (Citation2018) ethnographic research on the offline and online social life of the street in Harlem, New York, or the Why We Post Project’s (Miller et al. Citation2016) ethnographic investigation of globally diverse engagements with social media. However, unlike these ethnographies of the digital, we, similar to Malinowski, move beyond contexts dominated by industrial-capitalism. We take the ‘other’ seriously by more carefully examining the lived reality of digital markets in an economy where other horticultural, hunter/gatherer, relational or more broadly ‘bush’ principles rather than capitalist, individualist ones dominate; and we do so based on a comparable methodological approach adjusted based on nearly a century of methodological refinements including the aforementioned ethnographers of the digital and others (cf Gray Citation2009) who have recognized the value of ethnographic perspectives for challenging deterministic perspectives on digital transformations.

We spent one year, largely in a village, where we lived as similarly as possible as the local people.Footnote1 We studied the local language, Lau, spoken by approximately 15,000. We slept in a house that was sided and roofed with dried pandanus leaves. We gardened and fished and occasionally bought tin meats and tuna from one of the few local ‘canteens’ described in detail below. We went to church and watched soccer and volleyball on the beach. The only electricity was small solar powered bulbs which made for intimate evening social gatherings. We attended weddings and funerals. We also followed the social networks as villagers moved across the island and the archipelago, from the Lau Lagoon to the provincial capital of Malaita, Auki, to the only urban area, the capital Honiara on the neighboring island of Guadalcanal; and we occasionally found ourselves accessing Facebook and, to a much lesser degree, other parts of the Internet, that have become relevant to Lau daily lives. In other words, in as much as possible we participated in, and observed, all aspects of digital and non-digital everyday and exceptional life which we documented in field notes and also used as the context for a semi-structured, object centric interview schedule covering one hundred mobile phones and the villagers who used them.

Based on this research, we demonstrate the role these relational principles play in the digitizing markets in the particular context of Solomon Islands. We consider emerging digital bush markets as they cut across physical and abstract markets, small-scale and large-scale ones, and, thus, contribute to a broader anthropological effort aimed at problematizing and exploring the tensions and continuum between the two types (cf Hart Citation2012). We do so by grounding our analysis, first and foremost, in a study of the small-scale physical marketplaces that are central to Solomon Islanders’ day-to-day life and that allows for empirically situating the entanglements of concrete and abstract markets.

Solomon Islands small-scale marketplaces

Solomon Islands is home to two basic types of small-scale marketplaces located, variously, at the two extremes of the continuum that connects other and industrial-capitalist markets in Island Melanesia. The first extreme of small-scale marketplaces are predominantly industrial-capitalist retail businesses. In their concrete architecture, these brick-and-mortar sites of commerce are instantly recognizable. They sell a range of largely imported goods, are codified through business licenses, often visibly displayed at the cashier’s counter, and are characterized by sole reliance on government-issued money to facilitate exchange. Some are specialized, e.g. by focusing on the sale of foreign-produced movies or even cars. However, most of these businesses sell a mix of basic goods ranging from staple foods such as rice to tools such as bush knives, solar batteries or mobile phones. These retail businesses provide those basic, imported and industrially-produced goods that are in comparatively high demand and for which Solomon Islanders are willing to spend the limited cash resources to which they have access. In addition, most of these businesses can be found in urban, peri-urban or even peri-peri urban areas, that is to say in Honiara, in one of the provincial capitals, that would be Auki for Malaita, or in more regional ‘stations’ such as Malu’u, where regional government services are located alongside an often much smaller number of retail markets. At the same time, they are rarely indigenous owned and operated. Instead, Asian and especially Chinese immigrants hold most of these shops and have dominated Solomon Islands retail trade since the 1950s (cf Moore Citation2008).

Longstanding ‘bush markets’ are the second type of markets. These markets exist predominantly in rural areas. They pre-date colonization and are, especially in northern Malaita, central to the exchange of goods, largely garden produce and hunted fish, between saltwater and bush people (Ivens Citation1930; Maranda Citation2002; Ross Citation1978).Footnote2 Some things have changed. Before so-called ‘pacification’ (cf Cooper Citation1979), men used to stay at the perimeter while women did the trading. Men can now participate but few do. There are also new, industrially-produced goods: popcorn and popsicles, for example. There are new services, like ‘top-up’ stores for mobile data and talk and text credits. And there are the smartphones that store and use that data. Otherwise, much remains immediately comparable. The vast majority of available goods continues to be primarily sourced from the islands and surrounding waters and acquired through hunting, gathering, gardening and small-scale animal husbandry. In addition, they are places to acquire ritually significant objects such as dolphin teeth. Goods are also open to different modes of acquisition. Payments are increasingly made using state-issued currencies (cash), but at times also using longstanding non-state currencies such as shell money (cf Robbins and Akin Citation1999). Goods are exchanged through barter as well. These markets are also today, unlike the (peri-)urban retail businesses, dominated by indigenous Solomon Islander traders.

By serving as the primary location for the exchange of bush and saltwater goods, bush markets continue to play ‘an analogous structural role’ (Ross Citation1978, 119) to the exchange system that Malinowski explored in the neighboring Trobriand Islands. At a basic level, bush markets serve the exchange of livelihood produce. Still, at a larger societal level, they are not about the acquisition of profit but, first and foremost, about maintaining and strengthening connections across geographic, linguistic and sociocultural divides. In other words, they create the foundation for ‘sociocultural integration’ (Ross Citation1978, 119; emphasis added). As Walter Ivens already observed during fieldwork in the Lau Lagoon back in the 1920s, ‘the fishmarkets … have necessarily brought “shore” and “hill” into regular contact, and, where boundaries meet, distinctions tend to become obliterated, and people move to and fro more readily’ (Citation1930, 28).

Hybrid small-scale marketplaces

The aforementioned two types of markets exist on a complex continuum rooted, in this particular case, in early (pre-)colonial encounters between Solomon Islanders and Europeans. From first contact, Europeans essentially sought and violently enforced connections with Solomon Islands residents due to their potentials for industrial-capitalist resource extraction and exploitation. Europeans went after Solomon Islands lands and its products, such as the desired sandalwood (cf Shineberg Citation1967) and even after Solomon Islanders themselves. The latter were often forcefully recruited into indentured labor on Queensland plantations (cf Moore Citation2007). Colonization and subsequent pacification deepened these entanglements as ‘a non-economic means whereby the (economic) forms of articulation between expanding capitalism and local modes of production are strengthened and made more secure’ (Cooper Citation1979, 26).

Since colonization, capitalist encroachment has only intensified. Like many other Pacific Islands states, Solomon Islands is heavily dependent on international aid (cf Dornan and Pryke Citation2017), with most aid programs explicitly aiming to solidify Solomon Islands integration into the global capitalist and industrial political economy, be it through the construction of new hydropower dams or industrial tuna canneries. Simultaneously, Solomon Islanders increasingly depend on access to the cash economy to purchase various industrially-produced items such as mobile phones, or to address immediate food needs, for example, through imported staple foods such as rice.

In today’s small-scale marketplaces, these industrial-capitalist entanglements are most visible in those instances where the two primary types of marketplaces meet most explicitly. For instance, bush-style fresh food and ritual artifact markets have been formalized according to industrial-capitalist logic in places such as Honiara Central Market. There are also retail-style markets, locally known as ‘canteens,’ largely run by indigenous Solomon Islanders, that often do not have any business licenses and that are found in rural areas and the settlements surrounding urban cores.

Industrial-capitalist tendencies can be found across these hybrid markets. For instance, rural canteens provide the same kind of basic imported goods as urban retail markets (usually just on a smaller scale), including rice and petrol or kerosene to power generators or outboard motor engines. Because they sell largely imported goods they depend on cash income for their survival, and they may subsequently limit their transactions to the use of government currencies. They even extend lines of credit when customers do not have the necessary cash reserves to purchase particular goods. Similarly, the traders at urban bush-style markets often demand cash for their produce to meet running costs such as business licenses and stall fees. In addition, unlike rural marketplaces where traders are usually producers, traders at urban markets tend to rely on brokers to obtain the goods they sell,Footnote3 and these brokers largely operate on cash-based buy-and-sell systems.

At the same time, these industrial-capitalist presences in Solomon Islander-dominated small-scale markets do not mean that industrial-capitalism has triumphed over the bush markets and the other economic systems and values that they represent. On the contrary, ‘many local exchange systems appear to have flourished’ (Robbins and Akin Citation1999, 1) and, at least in the context of physical marketplaces, regularly subsume industrial-capitalist ventures into Solomon Islands moral economy and its prioritization of communal social reproduction. Hybrid markets, and most marketplaces dominated by indigenous Solomon Islanders, continue to be organized around the demands of Solomon Islands reciprocal bush economy and its moral reasoning – ‘a social act, wherein people reason about how to act toward each other so that their interpersonal relationships may flourish’ (Sykes Citation2012, 176). For example, rural canteens regularly struggle to survive because people tend to ‘shop along clan lines, ignoring prices of goods’ (Meltzoff and LiPuma Citation1986, 56) and because any credit that has been extended is often not repaid, or it is repaid in other ways, for example, through contributions to ritually significant events such as funerals or baptisms. Simultaneously, canteens that do survive and even flourish generally do so because they succeed at integrating their shopkeeping activities with the reciprocal ‘bush’ economy that is locally dominant, e.g. by sharing their profits in various ways with the villages they operate in (Scheyvens et al. Citation2020; Spann Citation2022).

Even formal retail businesses – those largely dominated by Asian immigrants and most clearly fitting the description of an industrial-capitalist small-scale marketplace – are, to some degree and occasionally quite literally, forced to operate within the bush economy that dominates economic activities in Solomon Islands at large. During moments of political unrest, Asian-operated retail businesses have been common targets, with Honiara’s Chinatown going up in flames in 2008 and most recently in November 2021. The reasons for the attacks specifically on Asian-operated businesses (rarely residential units) are complex and linked to broader uncertainties surrounding Solomon Islands development, politics and geopolitical embedding and the role of foreign-indigenous relations therein (cf Aqorau Citation2021; Moore Citation2008). Nonetheless, when discussing violence against retail businesses, foreign-operated but even locally-owned ones, we found that Solomon Islanders regularly mention that when businesses go up in flames it is not the result of a general dislike of e.g. the local Chinese community. Instead, they emphasize that particular businesses are targeted because of how they do ‘business,’ which, as David Welchman Gegeo and Karen Ann Watson-Gegeo argue, is conceptualized as ‘dead’ in its ‘[concern] only with material possessions’ (Citation2002, 389). Islanders explain that only those businesses that prioritize profit for owners over the well-being of staff and the communities they are meant to serve become a target of violence. Businesses that are community focused, irrespective of who owns and/or operates them, are not only spared but often actively protected during moments of unrest.

The digital transformations of Solomon Islands marketplaces needs to be considered in this context, where bush market practices and values continue to dominate and actively subvert industrial-capitalist practices. We do so in the following, emphasizing Facebook-based ‘buy and sell’ groups as a critical iteration of small-scale digital marketplaces in the country.

Digitizing small-scale marketplaces

For many Solomon Islanders going ‘online’ is synonymous with accessing Facebook through its smartphone app.Footnote4 Urban elites, those employed in the formal sector and those with backgrounds in higher education, often use the Internet more broadly. They send/receive emails, read the news, or use an array of social media platforms such as Instagram, Tiktok or Youtube. However, the vast majority of the population, urban non-elites and the approximately 80% of Solomon Islanders living in rural areas, primarily, if not solely, rely on Facebook to participate in the world wide web. Accordingly, it is not surprising that new, digital small-scale marketplaces have emerged on Facebook. Using Facebook’s ‘group’ function (sometimes but often not linked to Facebook’s official marketplace), Solomon Islanders have created various ‘buy and sell’ pages such as ‘Buy and Sell in Honiara (Solomon Islands)’ (87.2k members)Footnote5 or ‘Buy and Sell in Honiara’ (37.8k members) or ‘BUY AND SELL IN Solomon Islands -GIZO, NORO, Auki,MUNDA -Honiara’ (16.6k members).

We found that these ‘buy and sell’ pages are by no means a digital iteration of ‘brick and mortar’ retail businesses. On the contrary, they have emerged as a new type of hybrid marketplace that operates in many ways, and first and foremost, as digital extensions to Solomon Islands bush markets. Thus, ‘buy and sell’ pages, further solidify the dominance of bush market practices and values in Solomon Islands economic system. This holds on three key levels: First, most sellers on Solomon Islands ‘buy and sell’ pages are indigenous Solomon Islanders. Second, cash is not necessarily required, even though most transactions rely on cash. Barter or exchange for non-government currencies is possible and occasionally realized. Third, like bush market participation, participation in this digital marketplace is highly flexible. Products are bought and sold as they become available or if a particular need is to be met, but rarely as part of an industrial-capitalist ‘business venture’ that requires regular, steady supply of any given product or service and that follows idealist capitalist principles, where the ‘enhancement of the self and its enterprises without regard for the other is what ideally motivates economic action’ (Robbins Citation2008, 48).

Simultaneously, ‘buy and sell’ pages operate like bush markets and amplify the potential for bush markets to compete with or circumvent industrial-capitalist retail business. This capacity is evidenced in the products that are traded on these digital Facebook markets. Buy and sell pages offer nearly any kind of product, those usually available at bush markets – fresh, locally grown foods and ritually significant items – and those usually found at Asian-dominated, urban retail businesses, from clothing to smartphones to even cars. In other words, Facebook ‘buy and sell’ places expand the scope of bush markets and allow Solomon Islanders to purchase industrially produced goods from other Solomon Islanders; and in so doing Facebook ‘buy and sell’ places are realizing several key bush market principles – fairness, reliability, affordability and reciprocity.

Bush market fairness

Solomon Islanders prefer buying from other Solomon Islanders for various reasons, but a key one concerns limited trust in Asian-run retail businesses. Because retail businesses are believed to operate, primarily, to fulfill their own selfish interests for financial, industrial-capitalist gain many are suspicious of the fairness of the charged prices. In comparison, Solomon Islander traders are thought of as more trustworthy. They are deemed more likely to operate under bush market principles. At bush markets traders are believed to offer fair prices reflecting the time and effort that went into producing and obtaining the products for sale (cf Ross Citation1978).

This is not to say that Solomon Islander sellers are never viewed with suspicion. For example, buyers are particularly skeptical when items are being sold for a comparatively very low price. At least in town, it is hard to find someone who has not had their phone or other goods stolen at one time or another. Indeed, one of the first things people cautioned us upon arrival in Honiara was that thieves take razors to the seams of backpacks, purses and bags to steal the contents when walking through town; and ‘buy and sell’ groups are popular locations for reselling any loot. However, cheap goods are not necessarily the result of theft. We heard many stories of a cousin or foolish brother who got so drunk that they sold their handsets for low prices to buy a little bit more beer. Buyers were often not concerned about the immorality of these transactions. After all, the gains – a cheap new phone – were not ill-gotten but lost due to the seller’s immoral behavior.

While Solomon Islander sellers might sell goods acquired through immoral acts (theft), this is just one possible operational principle of the market seller. Two alternatives are, if not even more likely, especially in contexts of flexible market participation as longstanding and digital bush markets allow: that the seller is offering a fair price or that they are essentially getting punished for their immoral deeds (by losing a phone for beer). This then stands in stark contrast to retail businesses, even Solomon Islander run ones, that are much more explicitly embedded in industrial-capitalist practices, for example, because they have to figure out how to maintain an inventory and generate enough profit to restock even if it means, e.g. not to extend lines of credit to relatives or share their goods as part of ritual exchanges.

Bush market reliability

Just like products sold by Solomon Islanders are seen as more fairly priced they are also considered more likely to function as promised. Especially industrially produced electronic products tend to break down quickly because of the complex tropical environment they have to operate in (Hobbis and Hobbis Citation2021) and because of a perceived lack of quality checks during imports (Hobbis Citation2021b). Many Solomon Islanders we talked to are confident that retail businesses regularly sell products they know are faulty (with no reliable return policies). In comparison, as is the case with price setting, Solomon Islanders are more likely to be trusted to be fair in their quality assessments of the goods they sell. Their primary motivation is not deemed selfish and is oriented towards optimized profit margins by virtue of the shared reciprocal moral framework but also, more pragmatically, because of the longstanding, non-state accountability mechanisms in which Solomon Islanders are embedded.

Even when they happen online, product sales are rarely anonymous. There is no functioning mailing or other impersonalized delivery system. Products bought or sold are necessarily transferred by someone familiar with the seller, if not the seller themselves. Simultaneously, few Solomon Islanders have bank accounts and when do they, they are not used to transfer money digitally but to withdraw cash from Automated Teller Machines (ATMs). Sellers and buyers may not even agree on prices online. Often they exchange phone numbers, publicly on particular posts or through private messages to later on discuss when, where and for what (not even simply for how much) particular items will be exchanged.

In other words, and combined with the possibility of ‘paying’ for Facebook goods with non-state currencies, the exchange of goods for ‘payment’ nearly always happens in person, and not online. Accordingly, it is often not difficult to identify the seller and their families. If in one way or another cheated, the buyer (and their relatives) can demand compensation from the seller (and their relatives) following customary prescriptions (cf Allen et al. Citation2013). In comparison, if a customer considers themselves cheated by a formal retail business, they have few, not immediately violent, options as especially foreigner-run retail businesses reject customary compensation systems and instead demand issues to be solved through the formal legal system and the police. However, as Stephanie detailed elsewhere (Hobbis Citation2021b), the police are deemed more likely to support store operators than their customers. There are few ‘formal’ legal means that Solomon Islanders consider reliable enough to fall back on.

Accordingly, the products sold outside of often foreign run brick and mortar businesses are deemed to be less risky. Solomon Islanders trading with Solomon Islanders regularly do so within the checks and balances provided by the broader, longstanding sociocultural system. Formal retail businesses are by what makes them ‘formal’, more likely to be immoral in their engagements with customers as they are protected by ‘formal’ regulations and their enforcement systems, with a prioritization of the industrial-capitalist needs of the sellers above all else.

Bush market affordability

In this context of fair and reliable (digital) trading practices, Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups are also popular because they allow not only for circumventing retail businesses but also at least some of the cash-based brokers that have emerged as facilitators of trade relations between rural communities (and bush markets) and urban marketplaces. These brokers have contributed to better domestic circulation of goods but also their commodification and high cash-based price tags, making especially rural, ritually significant produce difficult for the majority of those urban dwellers without reliable salaried employment.

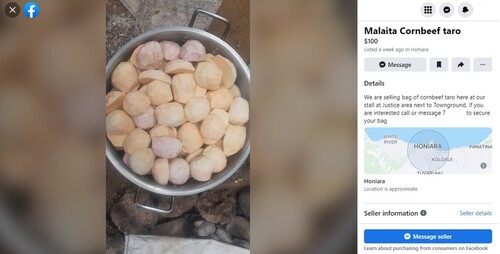

Assume you are based in Honiara and are looking to obtain taro, as depicted in . Taro is highly desirable. It has health benefits, but perhaps most importantly it is, also elsewhere in the Pacific, of particular cultural ritual significance. For example, in a detailed analysis of taro(plant)-human relations in neighboring Papua New Guinea, Porer Nombo and colleagues found that taro and taro gardens are, among others, recognized as ‘source of connection between what people did in the past and what they (continue to) do now’ (Citation2021, 357). Yet, growing taro is complicated and lengthy, taking about 200 days from planting to harvest. Taro also require particular soil conditions, and many areas, especially those with substantive saline intrusion, cannot grow them. Finding any garden plot is difficult in Honiara. One that is suitable for taro is nearly impossible. In other words, urbanites who want taro nearly always have to acquire them from rural areas.

Before the emergence of Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups, there were two primary options for finding taro in town: asking rural relatives to send some or buying some from one of Honiara’s hybrid fresh food marketplaces. Both options have their limitations. Rural relatives may not have any taro when needed or are unable to bring them to town; while taro offered at urban, hybrid fresh food marketplaces tend to be expensive. Often these taro arrive in town via multiple brokers and, exchanged various times for cash along the way, their end price in town can be unaffordable, at least for the many urban dwellers with temporary employment. ‘Buy and sell’ pages open up a third potential. They allow for finding, in essence, someone else’s relative who has taro but no relative in immediate need of it; the same kind of ‘seller’ who could also be located at rural bush markets but who is difficult, if not impossible, to find in town. Facebook, thus, allows rural visitors to trade local produce, however small, quickly and efficiently, if not otherwise required or desired by their urban kin. Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups can reduce prices for urban buyers while increasing their access to desired, rural goods. These actions contribute to a urban-rural synergy that is comparable to that between bush and saltwater people (cf Maranda Citation2002). The context is key: a longstanding, non-digital bush markets, serving as a place ‘where boundaries meet, distinctions tend to become obliterated, and people move to and fro more readily’ (Ivens Citation1930, 28).

Bush market reciprocity

The urban-rural digital bush market synergy is further realized by improving the circulation of goods from urban to rural areas. Just like digital markets make it easier for urban dwellers to find taro, these markets allow rural residents to find urban, often industrially-produced and imported products at prices deemed fairer and more affordable and in a quality that is considered more reliable. It is not easy to access Facebook from rural areas. Sometimes the network is simply not available, or the signal strength is weak. Sometimes, or rather often, rural residents do not have the resources to pay for data costs to go online and check Facebook ‘buy and sell’ pages. However, this does not make these pages inaccessible. There are various options to locate desired goods on these pages still, for example, by sharing access to Facebook on one phone with a temporary data plan, perhaps because an urban relative gifted (and remotely transferred) some phone credits to a rural relative. Another option is to call an urban relative, who is much more likely to be regularly online, to check if a particular item is available (for the right price) on a given ‘buy and sell’ page.

Urban relatives are nearly always involved in rural acquisitions of items from ‘buy and sell’ pages in either case. Most industrially-produced items on ‘buy and sell’ pages are sold from Honiara or another urban/peri-urban area. Rural residents thus have to rely on urban-based relatives to arrange the transaction and obtain the desired goods. Then, they must arrange for them to be brought to a respective village, often by involving an additional relative who is, anyways, traveling between the two sites. In other words, brokers are central to rural-urban trade on Facebook. However, these brokers are not paid in cash for their services. On the contrary, they operate primarily within the context of reciprocal exchanges where support with the circulation of objects essentially ‘defines what makes a “good” person and how “good” social relations are maintained’ (Hobbis and Hobbis Citation2022b, 867).

Urban residents, even second or even later generations of urbanites (Petrou and Connell Citation2017), are frequently concerned about losing their rights to return to their rural homes if they do not maintain close relationships with relatives living there based on their participation in exchange networks. Accordingly, urbanites are actively looking for opportunities to participate in reciprocal exchanges (cf Hobbis Citation2021b). Helping rural relatives acquire goods from ‘buy and sell’ pages is a relatively simple, highly valued option for rural relatives with few alternatives.Footnote6

Accordingly, Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups facilitate urban residents’ access to rural, often ritually significant, produce and facilitate urban residents’ ability to return the ‘favor’ to rural relatives, echoing a key operational sequence of rural non-digital bush markets. Rural residents rarely attend bush markets to cover individual or nuclear household needs. When they go to sell produce, they usually take along produce from others, selling it on their behalf given the amount of time and energy involved in reaching many of the bush markets (often an at least two hour, one way, dugout canoe ride) and the time that it takes away from other socioeconomic activities, be it housekeeping or work in gardens. Sellers also acquire goods for their village networks. In other words, rural bush market attendees operate similarly to urban users of Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups: they are brokers for an extended social network with their contributions being embedded in a system of reciprocal exchange of goods but also services, with the primary goal being the strengthening and maintenance of social relations.

Digitizing bush markets

Solomon Islanders use Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups as primary platform-enabled digital small-scale markets. These groups can facilitate trade following industrial-capitalist values and priorities as digital marketplaces. Their design allows for using buy and sell functions to make a profit in the capitalist sense of the ‘economic man’ for ‘rationalistic conception of self-interest’ (Malinowski [Citation1922] Citation1984, 60) and ‘without regard for the other’ (Robbins Citation2008, 48). However, our findings reveal a counterpoint to Thorhauge’s (Citation2022) research on the capitalist dominance of even non-capitalist marketplaces on Steam as digital platform. In Solomon Islands, Facebook as a digital marketplace does not necessitate industrial-capitalist trading on ‘buy and sell’ groups. We even observed the opposite, where Facebook, despite its capitalist design, is used for ‘[disciplining] the market’ (Kear Citation2022, 474).

Despite Facebook’s capitalist design – which unavoidably brings some form of industrial-capitalism to the country – Solomon Islanders’ use of Facebook markets has strengthened the viability of non-industrial-capitalist marketing also beyond the platform itself. Facebook has enabled a geographic expansion of longstanding, largely rural, bush markets. Solomon Islanders’ use of ‘buy and sell’ groups has created a new urban-rural synergy that increases urban residents’ access to rural (bush market) produce and rural residents’ access to urban (industrial-capitalist) products, all while being rooted in bush market characteristics and principles: they are highly flexible in when and how they are used, what is sold and what is bought; they are dominated by Solomon Islanders who other Solomon Islanders consider more trustworthy in their pricing policies and the quality of the products they sell; they do not depend on the use of government-issued currencies to operate and instead draw on broader, longstanding, non-state ‘monetary networks’ (Dodd Citation1994) that lie outside the control of not only the state but also digital platforms. Discussions about the ‘price’ of goods often take place via mobile phone rather than on Facebook, limiting the platform’s ability to even develop a sense of the value of particular goods. Similarly, the actual exchange of ‘payment,’ be it in the form of cash, non-state currencies or barter, necessarily takes place offline and outside the purview of any social institution other than Solomon Islands other socio-economic system.

In other words, Solomon Islands Facebook-based ‘buy and sell’ groups replicate largely the relationship-focused practices and values of bush markets, despite their hybrid dimensions and embedding in an, by design, industrial-capitalist platform: they operate, above all, by maintaining and strengthening connections across geographic, linguistic, sociocultural and, in this case, especially urban-rural divides; and, if something does go wrong, for example, if a buyer is cheated and receives a faulty product, buyers can rely on customary conflict resolution mechanisms (compensation requests facilitated by and between kin groups) to rectify the situation. At the same time, further affirming the dominance of bush market practices and values on ‘buy and sell’ groups, Solomon Islands Facebook markets escape any explicit form of control from the state and from other actors, such as the foreign business community that dominates brick and mortar retail businesses, that operate, above all, within industrial-capitalist values. Indeed, they even actively circumvent and, when possible, replace industrial-capitalist business ventures, including some of their hybrid iterations like the urban bush-style markets that are increasingly reliant on cash-only, and thus, state-mediated, transactions and the use of cash-based intermediaries. Hence, like canteens as offline, hybrid marketplaces, Solomon Islands digital bush market participants bear ‘little resemblance to the idealized notions of the economically rational, utility maximizing individual’ (Curry Citation2003, 406).

This being said, the argument could also be made that Solomon Islands ‘buy and sell' pages actually represent a realization of Bill Gates’ (and others’) vision for the ideal, abstract, digital, capitalist market. After all, by making prices fairer and advancing the affordability of goods, while decreasing the role of brokers, Solomon Islands ‘buy and sell’ groups essentially achieve ‘low-friction’ and ‘low-overhead’ with ‘market information [being] plentiful and transaction costs low’ (Gates et al. Citation1995, 158). However, a desire for fairness, affordability and accessibility is not what distinguishes industrial-capitalism from other economies such as the bush market economy of Solomon Islands. Instead, the most central distinguishing factors are the values that underlie exchange, what motivates those who offer goods to others and those who obtain goods from others (cf Malinowski [Citation1922] Citation1984; Polanyi Citation[1944] 2001): social reproduction vis-a-vis individual gain. While social reproduction may be a feature of industrial-capitalist economies (cf Götz Citation2015) and individual interest similarly plays a role in Melanesian other economies (cf Robbins Citation2008), what matters is the value system that dominates. In the case of Solomon Islands other economy, as it is also realized on Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups, what dominates is an emphasis on social reproduction, exchange ‘to foster mutual recognition’ (Robbins Citation2008, 48) and a vilification of self-interested behavior, including the accumulation rather than sharing of any form of monetary or good-based wealth, as a threat to societal well-being.

Hence, in Solomon Islands we find inter-economic struggles play out on Facebook ‘buy and sell’ groups, but, despite its global dominance, it is not industrial-capitalism that is winning.Footnote7 On the contrary, embedded in a context where bush markets and their values have long resisted the globally dominant industrial-capitalist economy, Facebook as a platform is being absorbed into the priorities of its Solomon Islands users. Solomon Islanders’ digital markets thus truly ‘[bring] into question the inevitability of [industrial-capitalist] market “imperatives,” the specific forms in which markets currently operate’ (Slater and Tonkiss Citation2001, 4) and how these imperatives are supposedly strengthened if not permanently cemented through digitization.

Conclusions

Too often, even the most critical digital market research is stuck in what Fisher (Citation2009) calls ‘capitalist realism,’ the perception that capitalism is inevitable and has been so successful in its global campaign of domination that there no options left. Critical digital scholars have increasingly challenged this linear understanding of digital-capitalist entanglements, highlighting possibilities for resistance from within industrial-capitalist systems (cf Ettlinger Citation2018; Kear Citation2022; Lynch Citation2020). Our findings suggest that possibilities for resistance are even more substantive than that. We approached the world of digitizing and digitized market activity with the broadest possible scope. This approach shifts beyond an equation of markets with capitalism, focuses, empirically, on places where other, non-capitalist economic systems flourish and recognizes the analytical value of economies that are in many ways unquantifiable, however, large or small their actual numbers. By so doing, we identified an instance in which user not only resist a digital, capitalist platform but effectively use it to strengthen other economic systems and their moral values.

Accordingly, we argue that it is necessary to further provincialize platform studies by going beyond what Payal Arora (Citation2019) calls ‘the next billion users’ to consider, in population terms, the opposite: the next ten thousand users. While Arora’s model accounts for groups such as the about one billion members of the dominate Hindu majority of India, ours looks beyond to other economic activities and values as they can be found not only in Solomon Islands (cf Hobbis Citation2021a). They can, for example, also be located among the tribal peoples of highland Odisha in southern India, who live in enclaves where they resist the industrialism of the majority with longstanding sustainable non-industrial modes of socioeconomic reproduction and who are, also by the Hindu majority, regularly associated with ‘“backwardness” within the dominant ideology of development’ (Berger Citation2014, 23).

The next ten thousand users may not be impressive in their numeric value, perhaps one of the reasons why Facebook is also not that much concerned about the unquantifiable Solomon Islands user (cf Hobbis and Hobbis Citation2022a). However, they matter substantively for our ability to understand how digital platforms do, or do not, necessarily, by virtue of their design, make resistance to industrial-capitalism futile. The next ten thousand are users who have resisted the longest to absorption into dominant world orders. They are not new to industrial-capitalism. On the contrary, they often live in places that have long been and continue to be colonized, especially for the extraction of natural resources for industrial-capitalist actors and their goals. The first Europeans – a Spanish expedition led by Alvarao de Mendaña, – to land on the shores of Solomon Islands belonged to the same generation of genocidal Spanish conquistadors that first colonized South America. The resume of one of the crew, Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, includes the capture of Tupac Amaru, the last Sapa Inca of the Inca state and thus ‘the instrument of perhaps the foulest judicial murder in the whole of the Spanish annals’ (Hackney and Thomson Citation[1850] 2010, xvi).

Despite half a millennium of violence, exploitation and chicanery, these next ten thousand users have not abandoned their other economic systems and values, whatever their particular iteration and entanglements with industrial-capitalism. We argue that it is these next ten thousand users that can offer invaluable insights into not just ‘economic man’ but ‘digitizing economic man’ and digitizing lives more broadly while also providing urgently needed insights in the particular remote, rural dynamics of digital transformations (cf CitationHobbis et al. 2023).

In short, our story here is not just about Solomon Islanders; it is about other economic practitioners found the world over, as their mini hegemons, as is the case of the Lau. Longstanding other economies are not anachronisms; they are not living dinosaurs. Instead, they are highly intentional, incredibly sustainable modes of reproducing socio-material life. But you would never know that looking out at the world from within industrialism. Accordingly, we need to engage with digitizing other markets, markets beyond those dominated by industrial-capitalism. Markets are shifty things and so are digitizing markets. For research on digital platforms and digital markets to even attempt to uncover more generalizable perspectives on digitization, then this research must, necessarily, also be about other actual and possible worlds, about testing the boundaries of digital economic and digital market research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

We thank the organizers and participants of two workshops on platform economies at the University of Copenhagen for insightful feedback to earlier drafts, in particular, Morten Axel Pedersen and Anne Mette Thorhauge.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For our fieldwork, we received certification of ethical acceptability for research involving human subjects from Concordia University (Certificate Numbers: 30002275; 30002385).

2 These types of ‘bush markets’ are not found across Melanesia, reflecting the cultural diversity of its many islands and peoples (cf Sharp Citation2021).

3 As Sharp (Citation2021) details, brokers, or as he calls them, intermediaries, were largely absent from pre-contact Melanesian trade and exchange systems and have only recently emerged alongside industrial-capitalist marketplaces and activities.

4 This synonymity does not necessitate a (perceived) dependency on Facebook. For example, when Solomon Islands Government debated a Facebook ban in November 2020, Solomon Islander commentators on Facebook itself regularly expressed confidence in possibilities for alternative platforms, be they foreign or possibly even locally designed, similar to Solomon Islands music platform, MJAMS, which serves as alternative to Spotify (cf Watson et al. Citation2020).

5 All group member counts were collected in October 2022.

6 For an outline of other, also digital, not-too-cash dependent alternatives see Hobbis and Hobbis (Citation2022b) on the rural-urban circulation of multimedia files.

7 See Hobbis and Hobbis (Citation2022a) for a discussion of how Facebook fails to extract any noteworthy commodifiable data from Solomon Islanders’ activities on the platform, thus, further limiting the platform’s ability to shape Solomon Islanders’ economic worlds.

References

- Allen, Matthew, Sinnen Dinnen, Daniel Evans, and Rebecca Monson. 2013. Justice Delivered Locally: Systems, Challenges and Innovations in Solomon Islands, The World Bank, August 2013, Research Report. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/16678.

- Appelbaum, Kalman. 2012. “Markets: Places, Principles and Integration.” In A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition, edited by James G. Carrier, 257–274. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Aqorau, Transform. 2021. “Solomon Islands’ Foreign Policy Dilemma and the Switch from Taiwan to China.” In The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands, edited by Graeme Smith, and Terence Wesley-Smith, 319–348. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Arora, Payal. 2019. The Next Billion Users: Digital Life Beyond the West. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Berger, Peter. 2014. “Dimensions of Indigeneity in Highland Odisha, India.” Asian Ethnology 73 (1-2): 19–37.

- Bestor, Theodore C. 2001. “Markets: Anthropological Aspects.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, edited by Neil J. Smelser, and Paul B. Baltes, 9227–9231. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Busse, Mark, and Timothy L.M. Sharp. 2019. “Marketplaces and Morality in Papua New Guinea: Place, Personhood and Exchange.” Oceania 89 (2): 126–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/ocea.5218.

- Carrier, James. G. 2018. “Moral Economy: What’s in a Name.” Anthropological Theory 18 (1): 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499617735259.

- Cooper, Matthew. 1979. “On the Beginnings of Colonialism in Melanesia.” In The Pacification of Melanesia, edited by Margaret Rodman, and Matthew Cooper, 25–42. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Couldry, Nick, and Ulises A. Mejias. 2019. The Cost of Connection: How Data is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating it for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Curry, George N. 2003. “Moving Beyond Postdevelopment: Facilitating Indigenous Alternatives for “Development”.” Economic Geography 79 (4): 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00221.x.

- Dale, Gareth. 2010. Karl Polanyi: The Limits of the Market. Cambridge: Polity.

- de Kloet, Jeroen, Thomas Poell, Guohua Zeng, and Yiu Fai Chow. 2019. “The Platformization of Chinese Society: Infrastructure, Governance, and Practice.” Chinese Journal of Communication 12 (3): 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1644008.

- Dourish, Paul, and Christine Satchell 2009. “The Moral Economy of Social Media.” In From Social Butterfly to Engaged Citizen: Urban Informatics, Social Media, Ubiquitous Computing, and Mobile Technology to Support Citizen Engagement, edited by Marcus Foth, Laura Forlano, Christine Satchell, and Martin Gibbs, 21–37. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Dodd, Nigel. 1994. The Sociology of Money: Economics, Reason and Contemporary Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Dornan, Matthew, and Jonathan Pryke. 2017. “Foreign Aid to the Pacific: Trends and Developments in the Twenty-First Century.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 4 (3): 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/app5.185.

- Elder-Vass, Dave. 2016. Profit and Gift in the Digital Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ettlinger, Nancy. 2018. “Algorithmic Affordances for Productive Resistance.” Big Data & Society 5 (1): 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718771399.

- Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is there no Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

- Gates, Bill with Norton Myhrvold, and Peter Rinearson 1995. The Road Ahead. New York: Viking.

- Gegeo, David Welchman, and Karen Ann Watson-Gegeo. 2002. “Whose Knowledge? Epistemological Collisions in Solomon Islands Community Development.” The Contemporary Pacific 14 (2): 377–409. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2002.0046.

- Götz, Norbert. 2015. “‘Moral Economy’: Its Conceptual History and Analytical Prospects.” Journal of Global Ethics 11 (2): 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2015.1054556.

- Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. 2021. The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Milton Keynes: Allen Lane.

- Green, Joshua, and Henry Jenkins. 2009. “The Moral Economy of Web 2.0: Audience Research and Convergence Culture.” In Media Industries: History, Theory, and Method, edited by Jennifer Holt, and Alisa Perren, 213–226. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Gray, Mary L. 2009. Out in the Country: Youth, Media, and Queer Visibility in Rural America. New York: New York University Press.

- Hackney, Lord Amherst of, and Basil Thomson [1850] 2010. The Discovery of the Solomon Islands by Alvaro de Mendaña in 1568. Translated from the Original Spanish Manuscripts Volume I. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Hann, Chris. 2021. “One Hundred Years of Substantivist Economic Anthropology.” Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Working Papers, No. 205. https://www.eth.mpg.de/pubs/wps/pdf/mpi-eth-working-paper-0205.

- Hardenberg, Roland. 2017. “Introduction.” In Approaching Ritual Economy: Socio-Cosmic Fields in Globalized Contexts, edited by Roland Hardenberg, 7–36. Tübingen: Tübingen University Press.

- Hart, Keith. 2012. “Money in Twentieth Century Anthropology.” In A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second Edition, edited by James G. Carrier, 166–182. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Hesmondhalgh, David. 2017. “Capitalism and the Media: Moral Economy, Well-being, and Capabilities.” Media, Culture & Society 39: 202–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716643153.

- Herzog, Lisa 2013. Markets. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E.N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/markets/

- Hobbis, Geoffrey. 2020. The Digitizing Family: An Ethnography of Melanesian Smartphones. London: Palgrave.

- Hobbis, Geoffrey. 2021a. “Digitizing Other Economies: A Critical Review.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 126: 306–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.08.006.

- Hobbis, Geoffrey, and Stephanie K. Hobbis. 2021. “An Ethnography of Deletion: Materializing Transience in Solomon Islands Digital Cultures.” New Media & Society 23 (4): 750–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820954195.

- Hobbis, Geoffrey, and Stephanie K. Hobbis. 2022a. “Beyond Platform Capitalism: Critical Perspectives on Facebook Markets from Melanesia.” Media, Culture & Society 44 (1): 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211022714.

- Hobbis, Geoffrey, Esteve-Del-Valle, Marc, and Rashid Gabdulhakov. 2023. “Rural Media Studies: Making the Case for a New Subfield.” Media, Culture & Society (online first): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437231179348

- Hobbis, Stephanie K. 2021b. “Beyond Electrification for Development: Solar Home Systems and Social Reproduction in Rural Solomon Islands.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 62 (2): 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12296.

- Hobbis, Stephanie K., and Geoffrey Hobbis. 2022b. “Non-/human Infrastructures and Digital Gifts: The Cables, Waves and Brokers of Solomon Islands Internet.” Ethnos 87 (5): 851–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2020.1828969.

- Ivens, Walter G. 1930. The Island Builders of the Pacific: How and Why the People of Mala Construct Their Artificial Islands: The Antiquity and Doubtful Origin of the Practice, with a Description of the Social Organization, Magic and Religion of Their Inhabitants. London: Seeley, Service & Company Limited.

- Kear, Mark. 2022. “The Moral Economy of the Algorithmic Crowd: Possessive Collectivisim and Techno-Economic Rentiership.” Competition & Change 26 (3-4): 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529421990496.

- Lane, Jeffrey. 2018. The Digital Street. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Langley, Paul, and Andrew Leyshon. 2017. “Platform Capitalism: The Intermediation and Capitalization of Digital Economic Circulation.” Finance and Society 3 (1): 11–31. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1936.

- Lynch, Casey R. 2020. “Contesting Digital Futures: Urban Politics, Alternative Economies, and the Movement for Technological Sovereignty in Barcelona.” Antipode 52 (3): 660–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12522

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. (1922) 1984. Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Longrove: Waveland Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12522.

- Maranda, Pierre. 2002. “Mythe, Métaphore, Métamorphose et Marches : L’igname Chez les Lau de Malaita, îles Salomon.” Journal de la Société des Océanistes 114–115: 91–114. https://doi.org/10.4000/jso.1418.

- Meltzoff, Sarah Keene, and Edward LiPuma. 1986. “Hunting for Tuna and Cash in the Solomons: A Rebirth of Artisanal Fishing in Malaita.” Human Organization 45 (1): 53–62. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.45.1.k244727u6952p88n.

- Miller, Daniel, Elisabetta Costa, Nell Haynes, Tom McDonald, Razvan Nicolescu, Jolynna Sinanan, Juliano Spyer, Shriram Venkatraman, and Xinyuan Wang. 2016. How the World Changed Social Media. London: UCL Press.

- Moore, Clive. 2007. “The Misappropriation of Malaita Labour: Historical Origins of the recent Solomon Islands Crisis.” The Journal of Pacific History 42 (2): 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223340701461668.

- Moore, Clive. 2008. “No More Walkabout Long Chinatown: Asian Involvement in the Economic and Political Process.” In Politics and State Building in Solomon Islands, edited by Sinclair Dinnen, and Stewart Firth, 64–95. Canberra: ANU E Press.

- Nombo, Porer, James Leach, and Urufaf Anip. 2021. “Drawing on Human and Plant Correspondences on the Rai Coast of Papua New Guinea.” Anthropological Forum 31 (4): 352–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2021.1990012.

- Petrou, Kirstie, and John Connell. 2017. “Food, Morality and Identity: Mobility, Remittances and the Translocal Community in Paama, Vanuatu.” Australian Geographer 48 (2): 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2016.1204671.

- Plattner, S. 1989. Economic Anthropology. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Polanyi, Karl. (1944) 2001. The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Prey, Robert. 2020. “Locating Power in Platformization: Music Streaming Playlists and Curatorial Power.” Social Media + Society 6 (2): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933291

- Robbins, Joel. 2008. “Rethinking Gifts and Commodities: Reciprocity, Recognition, and the Morality of Exchange.” In Economics and Morality: Anthropological Approaches, edited by Katherine E. Browne, and B. Lynne Milgram, 43–58. Lanham: Altamira Press.

- Robbins, Joel, and David Akin. 1999. “An Introduction to Melanesian Currencies: Agency, Identity, and Social Reproduction.” In Money and Modernity: State and Local Currencies in Melanesia, edited by David Akin, and Joel Robbins, 1–40. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Ross, Harold M. 1978. “Baegu Markets, Areal Integration, and Economic Efficiency in Malaita, Solomon Islands.” Ethnology 17 (2): 119–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3773139.

- Scheyvens, Regina, Glenn Banks, Suliasi Vunibola, Hennah Steven, and Litea Meo-Sewabu. 2020. “Business Serves Society: Successful Locally-Driven Development on Customary Land in the South Pacific.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 112: 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.03.012.

- Sharp, Timothy L.M. 2021. “Intermediary Trading and the Transformation of Marketplaces in Papua New Guinea.” Journal of Agrarian Change 21: 522–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/joac.12407.

- Shineberg, Dorothy. 1967. They Came for Sandalwood: A Study of the Sandalwood Trade in the South-West Pacific, 1830–1865. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Shome, Raka. 2019. “When Postcolonial Studies Interrupts Media Studies.” Communication, Culture and Critique 12 (3): 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcz020

- Slater, Don. 1993. “Going Shopping: Markets, Crows and Consumption.” In Cultural Reproduction, edited by Chris Jenks, 188–209. London: Routledge.

- Slater, Don, and Fran Tonkiss. 2001. Market Society: Markets and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity.

- Spann, Michael. 2022. “‘It’s How You Live’ – Understanding Culturally Embedded Entrepreneurship: An Example from Solomon Islands.” Development in Practice 32 (6): 781–792. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2021.1944988

- Srnicek, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Steinberg, Marc. 2022. “From Automobile Capitalism to Platform Capitalism: Toyotism as a Prehistory of Digital Platforms.” Organization Studies 43 (7): 1069–1090. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840621103068

- Strathern, Andrew, and Pamela. Stewart. 2012. “Ceremonial Exchange: Debates and Comparisons.” In A Handbook of Economic Anthropology, Second edition, edited by James G. Carrier, 239–256. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Sykes, Karen M. 2012. “Moral Reasoning.” In A Companion to Moral Anthropology, edited by Didier Fassin, 169–185. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Thompson, E. P. 1971. “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century.” Past and Present 50: 76–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/50.1.76.

- Thorhauge, Anne Mette. 2022. “The Steam Platform Economy: From Retail to Player-driven Economies.” New Media & Society (online first): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444822108140

- Watson, Amanda H. A., Denis Crowdy, Cameron Jackson, and Heather Horst. 2020. Local Music Sharing via Mobile Phones in Melanesia. In Brief 2020/7, Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/202686/1/dpa_in_brief_watson_et_al._20207.pdf.

- Watson, Richard T., Leyland F. Pitt, Pierre Berthon, and George M. Zinkhan. 2002. “U-Commerce: Expanding the Universe of Marketing.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30 (4): 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207002236909