ABSTRACT

While the literature on musical employment is growing, little research has been conducted on how concert fees are calculated, discussed, or contested. This article aims to explore these questions by drawing on the in-depth study of one new actor within the live music business: Sofar Sounds. Since 2009, Sofar Sounds has been organizing ‘secret concerts’ in ‘unconventional spaces.’ Between 2017 and 2019, the company has been publicly criticized on several occasions for its fee policy. I analyze these controversies over musicians’ remuneration as a critical site to understand the kind of economization performed within music industries. I argue that taking fees seriously allows for considering calculation of musical remuneration as a world-making operation. I identify three different and competing ways to calculate musicians’ fee: ‘appointment-fee,’ ‘co-production-fee,’ and ‘compensation-fee.’ I show that these calculations are performative achievements that contribute to the defining of what a musical performance is and of the actors who take part in it. In conclusion, I argue that the controversies about Sofar Sounds’ musicians’ fee policy cannot be understood only from a market and commodity point of view. The company uses ‘exposure’ to attach musicians and to strengthen its own (financial) value.

Introduction

Since the emergence of peer-to-peer file-sharing networks and the ‘CD crisis,’ artist remuneration has regularly agitated both the specialized and mainstream press (Marshall Citation2015; Citation2019; Arditi Citation2018; Negus Citation2019; Hesmondhalgh Citation2020; Watson and Leyshon Citation2022). These controversies concern the amount paid by consumers and the distribution between the different actors involved (music distribution services, labels, artists).Footnote1 However, while there exists an extensive literature on the ‘digitalization’ of music industries (Rogers Citation2013; Wikström Citation2013; Leyshon Citation2014; Hesmondhalgh and Meier Citation2018) as well as on the emergence of streaming platforms (Arditi Citation2014; Morris Citation2015b; Prey Citation2018; Eriksson et al. Citation2019; Heuguet Citation2021; Seaver Citation2022), as pointed out by several authors (Haynes and Marshall Citation2018; Hesmondhalgh Citation2020; Bataille and Perrenoud Citation2021; Everts, Hitters, and Berkers Citation2021), little research has been conducted on how musicians are paid in this new ecosystem. Moreover, remuneration and how it is calculated remain largely unexplored by the academic literature. I suggest that this issue extends beyond questions of employment. It invites investigation of the broader apparatus involved in being a musician in this emergent music platform economy.

This article aims to contribute to this question drawing from the case of Sofar Sounds. Sofar Sounds is an event company that organizes ‘secret concerts’ in ‘unconventional spaces.’ On several occasions between 2017 and 2019, the company was criticized for the payment fees offered to artists. Following these controversies, I argue that the calculation of remuneration is a crucial site of music economization. Using a pragmatist approach (Muniesa Citation2007; Citation2014), I examine the qualifications and calculations produced by the actors involved to explore different competing fees. I describe how these fees shape not only the possible ways for musicians to make a living from their music, but the quality of music itself. I conclude by arguing that fee calculation is performative in the sense that it actively contributes to realizing musical performances.

The music platform economy and musicians’ remunerations

Over the past two decades, several studies have attempted to analyze the changes introduced to the music business by digital technologies (Rogers Citation2013; Wikström Citation2013; Leyshon Citation2014; Morris Citation2015b; Arditi Citation2018). In this literature, a large part of the debate focuses on the emergence of ‘music platforms’ – from YouTube to Spotify – and their effect on music industries (e.g. Hracs and Jansson Citation2017; Hesmondhalgh, Jones, and Rauh Citation2019; Eriksson et al. Citation2019; Eriksson Citation2020; Morris Citation2020; Prey Citation2020; Heuguet Citation2021; Siles et al. Citation2022). These works mainly discuss the contours of new forms of (digital) commodities and/or markets or their consequences on musicians’ work and production. For instance, Prey (Citation2016; Citation2020) argues that the increased dependence of musicians on streaming platforms contributes to commodifying their music through data production and advertising. Azzellini, Greer, and Umney (Citation2021) examine the possible ‘platformisation’ of the live music labor market. They defend that organizational complexity – especially to attest to the quality of the service – creates barriers to the growth of labor-based online platforms.

Meanwhile, several authors describe how musicians’ work has changed within this new music platform economy (Arditi Citation2020; Hracs Citation2012; Haynes and Marshall Citation2018). On the one hand, with the decline in recorded music sales, concerts have become a primary market. However, the large number of actors operating within this market makes it highly competitive (Hracs Citation2012; Hracs, Jakob, and Hauge Citation2013; Holt Citation2020), contributing to a concentration of revenues on the most famous artists and making it more difficult for lesser-known musicians to earn money (Hracs Citation2015; Zhang and Negus Citation2021). On the other hand, Hracs, Jakob, and Hauge (Citation2013, 1144) point out that the work of musicians has ‘shifted from production to promotion and developing strategies to ‘stand out in the crowd‘ has become a top priority.’ To address this challenge, artists engage notably in promotion and relational work on social networks (Hracs and Leslie Citation2014; Baym Citation2018; Haynes and Marshall Citation2018).

This paper aims to contribute to both areas of the literature through the question of musicians’ remuneration. Indeed, such discussions have been primarily addressed from the point of view of music distribution and market (Leyshon Citation2014; Morris Citation2015b; Nieborg and Poell Citation2018; Eriksson et al. Citation2019), and little investigation has been conducted on artists’ remuneration. Furthermore, literature on musicians’ work usually focuses on annual revenues and sales (Leyshon Citation2014; Bataille and Perrenoud Citation2021; Watson, Watson, and Tompkins Citation2022), working conditions (Stahl Citation2001; Umney and Kretsos Citation2015; Umney Citation2016; Hracs Citation2015; Vachet Citation2022; Barna Citation2022), contracts (Stahl and Meier Citation2012; Arditi Citation2020; Klein Citation2020; Stahl Citation2021), or careers (Menger Citation2001; Faulkner Citation2013; Hracs and Leslie Citation2014; Perrenoud and Bataille Citation2017; Everts, Berkers, and Hitters Citation2022). Even though these studies highlight the heterogeneity of musicians’ incomes as well as the scarcity of fixed jobs, they rarely address precisely how much a musician is paid for a particular ‘gig’ (e.g. for a recording contract or a concert fee), and above all how such remuneration is calculated. I argue that such approach may allow for renewing our understanding of music platforms.

Fees as a vehicle to investigate the music platform economy

Several authors have pointed out the difficulties of opening the ‘black box’ of music platforms (Eriksson et al. Citation2019; Bonini and Gandini Citation2020; O’Dair and Fry Citation2020). This issue has been addressed mainly in two ways. First, platforms are considered as technical systems. The challenge is, then, to describe how they work, on which infrastructure they rely, and what kinds of data they produce and circulate (Eriksson et al. Citation2019; Prey Citation2018; Seaver Citation2022; Morris Citation2015a). Secondly, platforms are described as markets, and more precisely as two-sided or multi-sided markets, that give shape to new forms of music commodification through data brokerage and advertising (Morris Citation2015b; Fleischer Citation2017; Eriksson et al. Citation2019). From this point of view, the platform acts as gatekeeper between artists and audiences (Bonini and Gandini Citation2019).

However, several authors have recently attempted to develop an alternative approach to our understanding of platforms. Stark and Pais (Citation2020, 49) argue that platforms cannot be described as markets, hierarchies, or networks. Rather, such companies typically adopt a ‘Möbius organizational form’ (Watkins and Stark Citation2018), which resists defining what is the inside or outside of the organization. Platforms ‘co-opt assets that are not part of the firm and create value in a social and economic space that is neither inside nor outside of the platform’ (Stark and Pais Citation2020, 48). In this regard, several authors have shown how platforms enroll, activate, and manage their users through different devices (e.g. Van Doorn and Velthuis Citation2018; Bruni and Esposito Citation2019; Bosma Citation2022; Perrig Citation2022). Çalışkan (Citation2020) suggests that platforms can be understood as stack economization. According to Çalışkan, such businesses do not follow a classic marketization process. Stack is used here to account for platform work as a way to produce different modes of economization, mutually supporting and enabling each other within a single coherent framework. From this point of view, a platform is not only a market or a technical system, but both at the same time, as well as perhaps serving many other functions, including creation of money or assets. In a similar manner, Langley and Leyshon (Citation2017, 5) invite one to investigate what they call ‘platform capitalism’:

Performing the structure of the venture capital investment which also backs it, the platform business model prescribes a novel enterprise form that is crucial to the valuation and ‘capitalization’ processes which leverage debt against future revenue prospects from digital economic circulation.

Such considerations are useful to warn us that the music platform economy might be something more than merely a matter of commodification and/or marketization. I argue that analyzing music a priori as a commodity exchanged on a market may contribute to underestimating other dynamics at work within the contemporary music economy. Moreover, these claims are useful to underline that these companies transform not only the markets in which they operate, but also the identities of the actors involved. From this perspective, the way in which remuneration is calculated is not the product of a market, but rather constitutes what Keith Negus (Citation2013, 14) has called a ‘culture of musical production.’ In other words, if we wish to understand the emergence of such new businesses and the kind of attachment that binds artists to these companies, an analysis solely in terms of revenues, market organization, or working conditions may be insufficient.

For this purpose, I rely on authors who have been interested in calculation practices (Callon and Muniesa Citation2005; Muniesa Citation2007; Çalışkan Citation2009). Çalışkan and Callon (Citation2009; Citation2010) emphasize that an essential part of economization involves calculation. Such operation requires various material and cognitive devices: texts, techniques, metrological systems, logistical infrastructure, and rules (see Callon and Muniesa Citation2005; Muniesa, Millo, and Callon Citation2007; Beunza and Garud Citation2007; Doganova Citation2015; Doganova and Muniesa Citation2015; Muniesa et al. Citation2017). As Callon and Muniesa (Citation2005, 1231) point out:

Calculating does not necessarily mean performing mathematical or even numerical operations (Lave Citation1988). Calculation starts by establishing distinctions between things or states of the world, and by imagining and estimating courses of action associated with those things or with those states as well as their consequences.

Following these authors, I suggest taking how actors themselves produce different and competing ways of calculating remuneration for music seriously. The question is therefore to grasp how such calculations define what a musical performance is and who takes part in it. Therefore, I follow ‘valuation networks,’ which mobilize different entities to calculate musicians’ remuneration. Fee is a sufficiently vague term to be a good enough vehicle. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a fee is ‘an amount of money paid for a particular piece of work or for a particular right or service.’Footnote3 Therefore, it is not a price (of a commodity) or a wage (for a job).Footnote4 It reflects the ambiguity around the remuneration of musicians as well as the action of platforms, illustrated in the expression ‘gigFootnote5’ (see above). It raises the question of the kind of economization process at stake here. I examine how fee calculation is a world-making operation that engages, affects, and governs practices as well as frames actions (Abdelghafour Citation2020).

In the remainder of this paper, I start by introducing Sofar Sounds as well as my own research. I thereby describe how the company’s payment policy has been criticized on several occasions. Then, by analyzing the reaction of Sofar Sounds, I show how the company contributes to transforming the experience of being a musician and defines an alternative music economy. To conclude, I discuss some possible directions for further understanding the music platform economy.

Fieldwork

Since 2009, Sofar Sounds has been organizing ‘secret concerts’ in ‘unconventional spaces’: apartments, offices, shops, and similar places. According to the company, its events are designed to put ‘music at the center.’ Spectators are asked to leave their phones aside and to refrain from talking during the concerts to be able to focus on the live performances. Each event features three artists, and each performs for about twenty minutes, without a headliner. The line-up tends to be a mix of genres, bringing together artists from different musical worlds. More importantly, the spectators do not know in advance the names of the artists who will perform.

Before the 2020 lockdown, Sofar Sounds organized about 500 events a month. While the company is now present in 80 countries, its activity is mainly concentrated in the United Kingdom and the United States. In cities with few events (one to four every two months, called ‘hat-cities’), shows are run by volunteers and donations are collected by ‘passing a hat.’ In the cities where Sofar Sounds is most active (‘full-time cities’), audience members pay between $10 and $30, depending on the city and the day of the week. If ticketing is the main source of income for Sofar Sounds, the company also organizes sponsored events in partnership with brands (recently Firestone, Xfinity, Century Fox, Jameson). According to most of my informers, the special atmosphere of Sofar Sounds’ events is a key feature of its branding (Janotti and Pires Citation2018).

The Music and Tech press describes Sofar Sounds as a start-up ‘redefining the live music scene’ (CBS News Citation2017) and one of the MusicTech companies to watch. Sofar Sounds Limited was registered in the United Kingdom in 2011, two years after the first event. The first business angels arrived in 2013. In 2014, the company raised its first round of funding backed by venture capital funds. This funding was mainly used to develop the website. This first round was followed by a Series A in 2015. One year later, Virgin and its iconic CEO Richard Branson entered in the company capital. In 2019, Sofar Sounds announced a Series B of $25 million to pursue its development and, in 2021, acquired Seated, a ‘ticketing service including direct-to-fan presale and VIP ticketing.’ (Rendon Citation2021)

This paper is based on my PhD research (Riom Citation2021a). Between October 2017 and March 2020, I conducted a multi-sited ethnography of Sofar Sounds. I attended eighteen Sofar Sounds events in Paris, London, Lausanne, and Geneva. I have also interviewed musicians, Sofar Sounds teams (volunteers and paid staff), and spectators based in Switzerland, France, Turkey, Brazil, the United States, and the United Kingdom (59 interviews in total). In addition to this fieldwork, I carried out an extensive documentary analysis of both Sofar Sounds’ documents and sites, as well as press articles. The data were processed in a logic of continuous analysis of my materials (Glaser and Strauss Citation2017).

In this article, I analyze the controversy over artist remuneration offered by Sofar Sounds. Drawing on a methodology inspired by science and technology studies, my aim is to describe the nodes of these discussions over fees and how they act as sites of problematization, ‘places where actors define problems and possible solutions’ (Laurent Citation2011, 498). These discussions, which mainly took place on social networks and online media, are not only about opinions, but about the nature of the problem, the means to respond to this problem, and the identities of the different actors involved. As Çalışkan (Citation2007, 24) argues, ‘prices [but also wages or fees] are never set by a mere coming together of supply and demand. They are made, produced, and challenged by a multiplicity of actors.’ In other words, this controversy participates in making explicit not only what a fair fee is or how to calculate it, but also what a concert, an artist, and even Sofar Sounds are. Therefore, following fees allows for examining as closely as possible actors’ concerns and attachments as well as how they engage with them (Gomart and Hennion Citation1999; Hennion Citation2017).

#Boycottsofarsounds: two different fee calculations

In this section, I describe the criticisms that have been addressed to the Sofar Sounds musician fee policy between 2017 and 2019. The first press articles criticizing Sofar Sounds’ fee policy were published in webzines and blogs related to US West Coast music scenes (mainly from the Bay Area), after the company’s decision to introduce in some cities a ticketing system. Prior to 2016, admissions to concerts were donation-based. Artists could then choose either a $50 flat fee or the production of a video to be posted on the Sofar Sounds YouTube channel.

In the logic behind these criticisms, two types of fee calculations can be distinguished: ‘appointment-fee’ and ‘co-production-fee.’ The first one relies on musicians’ earnings in relation to the costs associated with the performance. The second one is based on receipt distribution between the artists and the organizers. In both cases, these two calculations construct two very different valuation networks distinguishing different entities and combining them to produce a new reality: a result.

The first and perhaps simplest model consists of calculating the difference between what artists receive and costs related to the performance. As Nolan points out, Footnote6 there are certain costs associated with performing: transportation (e.g. gas for the car), instruments, and possibly payment to musicians if, for example, a singer is accompanied. If we subtract these amounts from the $50 offered by Sofar Sounds, the conclusion is clear: the concert is ‘a net loss for the artists.’ Moreover, each act receives $50 regardless of the number of musicians involved. A ‘solo’ artist earns $50, but for a band of five musicians, each of them only gets $10. Nolan adds that to understand how low this payment is, it must be compared to the time required to perform. He calculates that if he takes into account not only the event itself, but also travel and rehearsing,Footnote7 the amount that a ‘solo’ artist receives is about $3–5 per hour, ‘definitely way below the minimum wage.’Footnote8

Nolan explains that Sofar Sounds’ fee policy goes against his efforts to ensure a minimum income. His quality of being a working musician is at stake:

The only way I’m making my living is by playing music. And I practice three or four hours a day. I took on a loan and bought a $15,000 cello. You know there are a lot of costs associated with being a musician. I have probably practiced ten thousand hours in my life like, longer than a doctor practices to be a doctor.

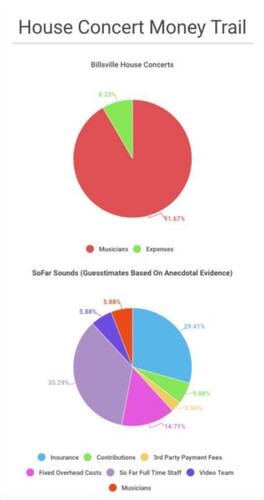

The second calculation mobilized by Sofar Sounds’ critics is a bit more complicated, but perhaps also more powerful. Unlike the first one, it does not focus on what the musicians earn, but rather on the distribution of ticketing incomes between the concert producers and the artists. Mia points out:Footnote9 ‘What they [Sofar Sounds] were doing, which was giving each band less than 10% of the door at a given show, was predatory and unethical.’ But how does she come to this conclusion? What leads her to argue that Sofar Sounds’ fees are ‘predatory’ and ‘unethical’?

The first step in her calculation is to estimate the ‘doors,’ meaning ticketing revenues, by multiplying the number of ‘guests’ by the price of a ticket.Footnote10 Based on her research, Mia estimates that Sofar Sounds events gather about 100 spectators, with an average admission price of $15. Thus, revenues reach about $1,500 for each event. She then calculates that the artists receive only 10% of the total ticket sales ($150 or $50 for three acts), meaning a little more than 3% per artist. This is well below what she considers standard remuneration for a house concert:

My bar is basically 60% of what is taken at the door or more should go to the artists. So, if you have three different artists, that’s 20% of the door per artist, and based on my calculation about the size of their shows and the general ticket price they were doing, that should be at least 150 dollars per artist, if there are three artists playing the show.

Mia’s calculation produces a different articulation than the ‘appointment-fee.’ The artist agrees to receive not a fixed amount, but a share of the event’s proceeds. He becomes a co-producer of the event (Guibert and Sagot-Duvauroux Citation2013). Here, the artist partly participates in the risk, but also in the profit of the event’s organization.

Such ‘co-production fee’ relates directly to the way in which the event’s revenue is calculated and then distributed among the various stakeholders. As François (Citation2004) has described in the case of the early-music market,Footnote12 the challenge is to break down the costs to calculate the remuneration of the different actors. This system is based on accounting practices that distinguish different actors, but also their responsibilities and their share of the revenues (Miller and Rose Citation1990). Calculating the budget of a Sofar Sounds event allows Mia to say that the fees offered are ‘a kind of scam.’

Mia’s calculation directly raises the question of the kind of business that is Sofar Sounds. A kind of showcase? A concert promoter? A tech start-up backed by venture capitalist firms? A predatory company that attempts aggressively to enter the house concert market? Moreover, Mia doubts that the well-known artists who performed at Sofar Sounds agreed to do it at this rate. She notes that this situation makes it hard for artists to understand all the financial issues they are involved in and gives the impression of being ‘taken advantage of,’ because the accounts of Sofar Sounds remain ‘damn opaque’ in her eyes.

In this section, I have described two ways to calculate an artist’s remuneration. Each of these two fee calculations qualifies differently the role of the protagonists (artists are for example alternatively described as workers or as co-producers). Fee calculation enacts a particular form management of labor force as well as a distribution of responsibilities and risks. It also affects the people who carry out such operations. As with Nolan, Mia’s calculations transformed her understanding of Sofar Sounds and moved her to act. In the next section, I examine how Sofar Sounds reacted to these criticisms.

‘How Money Works at Sofar Sounds’: The Transformation of the Sofar Sounds Fee Policy

In this section, I examine how Sofar Sounds responded to the critique addressed at its fee policy. I show that the company answers by defending a third way of calculating a musicians’ fee: ‘compensation-fee.’

Following the publication of these articles and their echo on social media, Mia published on her Facebook page a message she received from Sofar Sounds. The same message was sent to several people suggesting that Sofar sounds was considering revising its fee policy in response to criticism. The message acknowledged that the issue is ‘complicated’ and that there is a form of misunderstanding around it. It recognized that $50 is inadequate and announced that the fee would be raised to $75 (it was later increased to $100). It then attempted to provide some explanation. First, it accounted that the $50 fee is based on the length of the set – 20/25 minutes – and not on the entire event and travel. It added that artists’ remuneration goes beyond the $50 offered and includes ‘non-monetary’ elements: a video (of ‘high quality’ made available to the artists for free), promotion on social media, as well as the possibility of organizing tours through Sofar Sounds’ ‘global community.’ Finally, the response noted that the artists could supplement the fee by selling merchandise, on which Sofar Sounds does not take any commission, unlike many music venues. Footnote13

In addition to these explanations, the message also acknowledged the legitimacy of questions: Where does the ‘rest’ of the money go? And why aren’t artists paid more? Here, like Mia, Sofar Sounds focused on organizational costs: ‘There are extra costs that are not always obvious to our guests or artists’ related to the ‘complicated nature of the company’. Therefore, the budget of an event accounts not only for how the money circulates, but also how Sofar Sounds works.

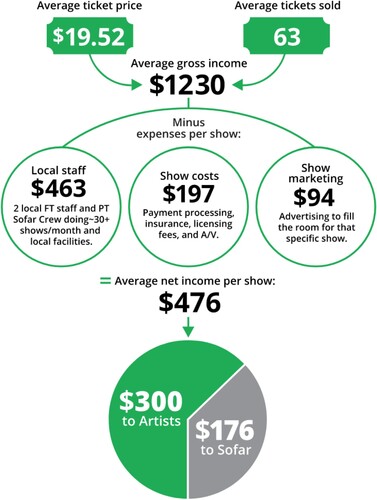

Since 2017, the company attempted to explain these costs on several occasions. The latest one followed a Series B fundraising of 25 million dollars in May 2019. Sofar Sounds again faced criticism regarding its fee policy.Footnote14 On this occasion, the freshly appointed CEO, Jim Lucchese,Footnote15 himself took up the defense of the Sofar Sounds policy in a statement titled How Money Works at a Sofar Show: A Closer Look at Our Expenses and Evolving Artist Compensation (Sofar Sounds Citation2019a). His argument was very similar to the June 2017 statement but gave more detailed numbers. It aimed to demonstrate that the artists receive most of the profits of each event:

The average net income split between artists and Sofar is currently 63/37, with 63% of the net show income going to the artists. Our goal is to move from today’s 63/37 average profit split for our standard show format (3 artists and 20–25-minute sets) to 70/30 across Sofar-operated cities, in favor of the artist.

This calculation outlines a new fee: a ‘compensation-fee.’ The focus here is not revenue distribution between the stakeholders, but profit-sharing. By transforming the calculation, Sofar Sounds shifts the subject of the discussion, but also its relationship with the artists. The costs related to ‘local teams’ are separated from the ‘global’ activities. The artists and Sofar Sounds are not presented as ‘co-producers’ of the event, but instead, as both beneficiaries of the work of the local team. Moreover, what is offered to artists is not a proper remuneration, but a ‘compensation.’

Furthermore, the calculation introduces a new entity: the ‘average event.’ The policy is not relying on a particular show, as in Mia’s calculations, but generalizes the same fee for all events. However, the statement recognizes that the indexation of remuneration to the number of tickets sold may be examined:

Another question that has come up in our conversations with artists that we’ve been thinking about a lot: can Sofar pay more when we sell more tickets? Shows where we sell more tickets than average do help us offset the cost of shows where we sell less than average, but we’re figuring out how we can pay more for larger shows.

Following this statement, Sofar Sounds announced another change in fee policy in January 2020. Artists will receive $100 for events up to 70 people, $125 for events of 71 to 100 people, and $150 for events of more than 100 people. The press release specified that this change only affects ‘full-time cities’ with ticketing systems. In ‘hat-cities,’ where donations are collected, Sofar Sounds will still offer a flat fee or a video. The press release justified this difference by explaining that in those cities, Sofar Global does not take a ‘cut’ and all the money collected is used to run the local team.

The clearly stated aim of this new fee system is both to make sure that the artists know how much they will be paid and to account for the financial functioning of Sofar Sounds. In addition, the announcement also emphasized how the new fundraising will improve the services provided to artists. The blog post detailed the tools the company is developing:

We see this as a small step in a series of improvements to how Sofar works for artists. A few others that we’re working on:

Improved artist website, online application and booking.

Streamlined booking request system for touring artists.

More ways to turn audience members into fans through merch sales and social follows.

Making it easier for artists and photographers to connect, and for show photos and videos to reach more people. (Sofar Sounds Citation2019a)

Through these announcements, Sofar Sounds reaffirmed its aim to be a ‘platform’ to help artists to connect with other artists while ‘turning more listeners into fans.’ (Sofar Sounds Citation2020) Making explicit the ‘non-monetary’ payment offered to artists demonstrates not only the interest of artists to come and play at Sofar Sounds, but also the necessity of its financial sustainability. In other words, Lucchese argued that, by asking for too-high remuneration, artists may compromise a service that brings them ‘exposure’ and a way to develop their career. Sofar Sounds’ ‘compensation-fee,’ through the associations that its calculation produces, signifies this mutual dependency. It seals the alliance between the artists and Sofar Sounds and ties them together.

What is the price of the exposure? Developing your audience, investing in your career

In this section, I investigate how Sofar Sounds’ fee policy not only contributes to shaping musicians’ careers, but also attaches them in a very particular way to the company and its value as a service to build their audience.

Sofar Sounds’ statements put ‘exposure’ as a key element of fee calculation. The main remuneration is not monetary, but a chance to develop an audience. In other words, engaging new fans should be the prior motivation for artists to perform at Sofar Sounds. ‘Four to five songs is plenty of time to win someone over and create a super fan for life. […] No matter how big or small the audience, you never know who is listening, and every potential fan counts towards the bigger picture,’ (Sofar Sounds Citation2019b) argues an article published on the Sofar Sounds website. Lizard, an English singer-songwriter who played multiple times at Sofar Sounds, agrees:

Every city you’re playing, you’re gaining new people to see you, and so how I do it is I do that and then I do my own tour where some of those people are coming, and then money is much better. So, it’s a sort of promotional thing but with a little bit of money, so you’re not losing money.

Matt, a London-based musician, explains:

To start your career, it’s perfect. Before, when you wanted to start your career, you had to have a label and now thanks to Sofar, Facebook and all that, you don’t have to. For me it’s been perfect to find what I like, what I like to do. It is easier now. I am a bit more marketable now. I already have a fan base. Labels don’t take risks anymore, but now that I have made a lot of the work myself, I would be in a better position to negotiate a better deal.

Several authors showed that musicians’ career organization can follow different rationales. For instance, Hennion (Citation1981) described magnificently the way in which the CD shapes the careers of pop stars and how their careers are very different from the work of cabaret singers. The paths and the trials of these two careers are not the same. In the same vein, other authors have emphasized the specificity of the careers of artists in independent labels compared to those in the major labels. Hesmondhalgh (Citation1997; Citation1999) gives a great account of the creation of ‘indie’ labels as a reproblematization of the means to make a career and the definition of success.

Therefore, how does Sofar Sounds shape a form of rationality to pursue a musical career? And how is it different from other career paths? Rafe Offer, Sofar Sounds co-founder and chairman, explains:

So Sofar is all about people who want to discover music and have a close relationship with that artist as they grow because this is something that tends to happen nowadays is an artist will get snapped up by a label and carefully constructed for 18 months and then released onto the world and everyone is like, who’s this person? That’s not how to create music and create art works.

The ‘value’ of this exposure is also part of the critiques addressed to Sofar Sounds. Celia, a Paris-based artist, asserts: ‘I think the fees could be better. We must stop telling artists that we will give them exposure.’ As Wade Sutton sums up in an episode of his podcast devoted to the Sofar Sounds controversy:Footnote17 what’s at stake is the dependence of artists on Sofar Sounds. According to this music industries commentator, the issue goes far beyond Sofar Sounds: it links to a wider ecosystem where platforms benefit from ‘content creators’ without providing financial sustainability.

What these criticisms point out is that ‘exposure’ attaches Sofar Sounds and artists in a very particular way. In other words, exposure – or more precisely the very particular kind of exposure Sofar Sounds provides to artistsFootnote18 – contributes to establishing Sofar Sounds as an ‘obligatory point of passage’ (Callon Citation1984) between the artists and their future success. By positioning itself as a ‘platform,’ Sofar Sounds produces not only a particular relation with the musicians – these have ‘interest’ in the existence of Sofar Sounds – but also its own value as a service. The artist is not a provider or a co-producer of the event anymore, but a beneficiary. The roles between Sofar Sounds and the artists are somehow reversed, and it is no longer quite certain who is the client and who is the seller.Footnote19 However, this shift is not only a rhetorical effect. It is enacted in the way the Sofar Sounds events are organized: from the spatial ordering of ‘unexpected’ and ‘intimate’ venues to the eclectic booking and the way the artists think and adapt their songs (Riom Citation2020; Citation2021b; Citation2023). This new ‘service’ depicts a very particular way of being a musician: a creator, an independent entrepreneur of his/her own career and looking towards a future success. Moreover, Sofar Sounds’ ‘compensation-fee’ produces a particular idea of what a live performance is: something like a showcase to build an audience and to provide ‘exposure.’ Finally, Sofar Sounds detaches musicians from immediate profit and attaches them to potential future revenues. The ‘compensation-fee’ produces a different temporality from the one of markets, the one needed for a possible return on investment for the musicians, but also for the development of Sofar Sounds.

Conclusion

In this article, I have aimed to contribute to the study of musicians’ remuneration in the emerging music platform economy. Using a pragmatic approach, I have followed controversies on Sofar Sounds’ fee policy. I described how involved actors calculate and construct arguments to establish different fees. First, I distinguished two fee calculations that are used to criticize Sofar Sounds. The first one is based on the costs of the artists and establishes an hourly remuneration. It draws the idea of the musician as a worker and as a service provider who must be able to make a living from his/her activity. The second fee calculation focuses on the event’s organization. It estimates the income and examines its distribution between the organizers and the artists. Here, the artists are described as co-producers of the event.

Then, I show that Sofar Sounds outlines a third fee calculation to answer its critics. This ‘compensation-fee’ is not a salary, but rather a compensation. It aims to preserve the company’s financial sustainability and puts ‘exposure’ offered to artists when performing at Sofar Sounds as the main payment. ‘Exposure’ allows Sofar Sounds to present itself as a platform that allows musicians to be discovered. It serves as a device to bond artists to Sofar Sounds and its events. Therefore, the company appears as a service provider on which artists rely. Somehow, the client-seller relationship is partly reversed. In short, Sofar Sounds’ ‘compensation-fee’ enacts a culture of music performance based on the idea of short and stripped-back sets that aim to promote artists and possibly create new revenues through streaming platforms and social media.

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize three possible contributions. First, fees are not a mere conversion of artistic value into economic values, but instead a central element in the constitution of music qualities. Major analytic frameworks within the sociology of arts and culture consider musicians’ remuneration as some sort of intermediary between cultural values (talent, reputation) and economic factors (Moulin Citation1995; Hutter and Throsby Citation2007). On the contrary, I have shown throughout this article that music is reassembled through fee calculation processes. Concerts do not preexist their budget calculation. Fees define what is ‘doable’ as a performance. Thus, these are not mere artifacts, but key sites where musical production is at stake and constitutive of music’s very existence.

Moreover, fee calculation participates in qualifying the different actors involved. To Simon Frith’s (Citation2017) question ‘are musicians workers?,’ each of the three fee calculations described gives a different answer. Musicians are successively workers, co-producers, and emerging artists who invest in their future career. Simultaneously, fee calculation redefined those who carried them out. One the one hand, Mia and Nolan became activists denouncing what they see to be a predatory business practice. On the other hand, Sofar Sounds attempted to be perceived not as an event company but a service provider for artists by calculating and revising its fees policy. In other words, fee calculation is more than a simple mathematical operation. It transforms the involved actors and contributes to an ethno-theory of what music is and how it should be performed.

Secondly, fee calculation needs to be understood as a process of realization, as the provocation of a new reality (Muniesa Citation2014). In that sense, it is performative, but not in the Callonian sense that ‘economists perform the economy’ (Callon Citation1998). It has rather something to do with what McKenzie (Citation2002) calls ‘performance management’ or Ervin Goffman’s (Citation1978) understanding of the notion of performance: an activity that engages individuals in particular forms of collective action. Saying that fee calculation is performative means that it shapes this collective action (see also, Hennion Citation2014). First, it gives form to music by enacting an economy around live performing (way of touring, bundling audiences, generating new revenues). Then, it is also performative because fees define a form of efficiency by maximizing costs to (monetary and non-monetary) revenues and distinguish what is a ‘good gig’ from a ‘scam.’ Finally, in the case of this controversy, fee calculation is performative because it gives a public account of a form of economic organization. Here, further research could provide additional insight into how fee, wage, and price calculations are crucial to understanding the kind of economization performed within music industries.

Thirdly, while the consequences of platform-based businesses on cultural production have mainly been studied as a new form of commodification or market gatekeeping, the case of Sofar Sounds raises an interesting question. What if those companies might not necessarily be commodifying music? Rather, I would suggest that there is a different form of economization at stake here. Sofar Sounds finds its existence as a company through its successive rounds of funding.Footnote20 With Tellmann (Citation2021), we could consider Sofar Sounds’ venture as the creation of an attachment necessary for the capitalization and the stabilization of the value of the company itself. The events, the audience, and the musicians are not so much a market but rather the value of the company. I have shown how ‘exposure’ contributes to bonding them to Sofar Sounds. This might suggest that contemporary debates around musicians’ remuneration, the ‘creator economy,’ and perhaps more broadly around what is now called ‘digital labor’ cannot be understood without considering that these forms of business-making are less engaged in building a market than in producing their own financial value (Muniesa et al. Citation2017; Langley and Leyshon Citation2017; Birch and Muniesa Citation2020; Muniesa and Doganova Citation2020). Economization here consists in carefully attaching ‘users’ (whether they are producers, consumers, or any generified entities) and activating different forms of economic processes to strengthen the company’s brand equity and to attract new investors.

Acknowledgements

Early versions of this paper were presented at the 2019 SSA Congress in Neuchâtel, at the 2021 I3 Doctorials in Paris and at the 2021 Interdisciplinary Market Studies Workshop in Grenoble. In addition to the feedback I received during these presentations, the paper benefited from comments from Fabian Muniesa, who helped me put my argument on the right track, Luca Perring, Ben Morgan, Benjamin Alexander, and Solène Gouilhers. I am also grateful to Koray Çalişkan for his generous guidance as well as to the three anonymous reviewers for their very thoughtful feedback on a previous version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Loïc Riom

Loïc Riom is a junior lecturer at the STS Lab of the University of Lausanne in Switzerland. His research interests lie at the intersection of the sociology of music and science and technology studies. Specifically, he focuses on the live music markets, concert promotion, and music industries’ financing. He received his PhD from the Centre de Sociologie de l'Innovation de l'Ecole Supérieure des Mines de Paris, where he studied the economization of intimate and secret concert formats. Currently, he is working on MusicTech.

Notes

1 For instance, many commentators aim to calculate how much a stream on a platform such as YouTube or Spotify is worth to artists. E.g. https://freeyourmusic.com/blog/how-much-does-spotify-pay-per-stream.

2 Capitalization here refers to ‘a process through which something becomes an object of investment and, therefore, an object that is considered primarily from the angle of capitalization, that is, as a vehicle for return on investment’ (Doganova and Muniesa Citation2015, 120).

3 Cambridge Dictionary, ‘fee,’ https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/fee.

4 Franssen and Velthuis (Citation2016, 264) point out that research on cultural industries is divided dichotomously between, on the one hand, the study of mass products and, on the other hand, the study of unique goods: ‘scholars of markets for, for instance, books, theatre or music have typically not been interested in prices and have instead studied (determinants of) sales and revenues […], while scholars of art markets have left sales aside and have instead focused on prices.’

5 Karl Marx himself noted such ambiguities when it comes to the question whether a signer is a worker or not (see Stahl Citation2021). The term ‘gig’ has been used since the beginning of the twentieth century in popular music to designate an engagement in exchange for a fee (see Cloonan and Williamson Citation2017).

6 A cellist based in the Bay area who called for a boycott of Sofar Sounds in an open letter published online. I interviewed Nolan two years later. All names are pseudonyms.

7 Because Sofar Sounds’ setting is different from traditional music venues, certain artists spend a lot of time practicing adapting their music (Riom Citation2023).

8 In California, the minimum wage is $12 per hour.

9 A country singer based in Nashville who criticized Sofar Sounds several times on social media. I interviewed Mia in 2018.

10 H. Stith Bennett (Citation2017) also shows that the distribution of ticketing revenue is an important criterion in evaluating a ‘good gig.’

11 The same thing occurs in the DIY and hardcore scenes, where most of the revenue goes to touring bands to cover their traveling costs (Verbuč Citation2021).

12 Early-music refers to musical repertoires from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

13 For many of my informers, ‘merch’ is an important source of income as well as a way to connect with their audience and make their music circulate (on this topic see Müller and Riom Citation2019).

14 E.g. Constine Citation2019; Doctorow Citation2019; Jacca-Routenote Citation2019.

15 Jim Lucchese is known to be the former CEO of the music data company The Echo Nest. After the company was acquired in 2014 by Spotify, Lucchese served as Global Head of Creator for the Swedish streaming platform.

16 Such democratic claims were also identified in the narratives of Spotify (Hodgson Citation2021) and YouTube (Heuguet Citation2021). In some respects, it may echo TV talent shows (Arditi Citation2020).

17 Sutton, Wade. 2019. ‘Should Musicians Use Sofar Sounds?’ The Six Minute Music Business Podcast, March 1. https://player.fm/series/the-six-minute-music-business-podcast/should-musicians-use-sofar-sounds.

18 For more details on how Sofar Sounds theories and shape the artist-fan relationship, see Riom, Citation2020; Citation2021b.

19 See Morgan (Citation2019) or Leyshon and Watson (Citation2021) for a similar argument on streaming platform and playlist.

20 For more details on Sofar Sounds’ funding history see Riom Citation2021a (chapter 7).

References

- Abdelghafour, Nassima. 2020. “Micropolitics of Poverty: How Randomized Controlled Trials Address Global Poverty Through the Epistemic and Political Fragmentation of the World.” (PhD diss.). CSI Mines-ParisTech, PSL University.

- Arditi, David. 2014. iTake-over: The Recording Industry in the Digital Era. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Arditi, David. 2018. “Digital Subscriptions: The Unending Consumption of Music in the Digital Era.” Popular Music and Society 41 (3): 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1264101

- Arditi, David. 2020. Getting Signed: Record Contracts, Musicians, and Power in Society. Berlin: Springer Nature.

- Azzellini, Dario, Ian Greer, and Charles Umney. 2021. “Why Isn’t There an Uber for Live Music? The Digitalisation of Intermediaries and the Limits of the Platform Economy.” New Technology, Work and Employment 37: 1. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12213.

- Barna, Emília. 2022. “Between Cultural Policies, Industry Structures, and the Household: A Feminist Perspective on Digitalization and Musical Careers in Hungary.” Popular Music and Society 45 (1): 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2021.1984022

- Bataille, Pierre, and Marc Perrenoud. 2021. “‘One for the Money’? The Impact of the ‘Disk Crisis’ on ‘Ordinary Musicians’ Income: The Case of French Speaking Switzerland.” Poetics 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101552.101552.

- Baym, Nancy K. 2018. Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection. New York: NYU Press.

- Bennett, H. Stith. 2017. On Becoming a Rock Musician. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Beunza, Daniel, and Raghu Garud. 2007. “Calculators, Lemmings or Frame-Makers? The Intermediary Role of Securities Analysts.” The Sociological Review 55 (2_suppl): 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00728.x.

- Birch, Kean. 2022. “Reflexive Expectations in Innovation Financing: An Analysis of Venture Capital as a Mode of Valuation.” Social Studies of Science, https://doi.org/10.1177/03063127221118372.

- Birch, Kean, and Fabian Muniesa, eds. 2020. Assetization: Turning Things Into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bonini, Tiziano, and Alessandro Gandini. 2019. “‘First Week Is Editorial, Second Week Is Algorithmic’: Platform Gatekeepers and the Platformization of Music Curation.” Social Media + Society 5 (4), https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051198800.

- Bonini, Tiziano, and Alessandro Gandini. 2020. “Know Her Name: Open Dialogue on Social Media as a Form of Innovative Justice.” Social Media + Society 7 (4), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984447.

- Bosma, Jelke R. 2022. “Platformed Professionalization: Labor, Assets, and Earning a Livelihood Through Airbnb.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54 (4): 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211063492

- Bruni, Attila, and Fabio Maria Esposito. 2019. “It Obliges You to Do Things You Normally Wouldn’t: Organizing and Consuming Private Life in the Age of Airbnb.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 12 (3): 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20356609v12i3p665

- Callon, Michel. 1984. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay.” The Sociological Review 32 (1_suppl): 196–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1984.tb00113.x

- Callon, Michel. 1998. The Laws of the Markets. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Callon, Michel. 2021. Markets in the Making: Rethinking Competition, Goods, and Innovation. New York: Zone Books.

- Callon, Michel, and Fabian Muniesa. 2005. “Peripheral Vision: Economic Markets as Calculative Collective Devices.” Organization Studies 26 (8): 1229–1250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605056393

- CBS News. 2017. “How Sofar Sounds Is Redefining the Live Music Scene around the Globe.” CBS News, January 24. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/sofar-sounds-songs-from-a-room-live-music/.

- Cloonan, Martin, and John Williamson. 2017. “Introduction.” Popular Music and Society 40 (5): 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1351117

- Constine, Josh. 2019. “Sofar Sounds House Concerts Raises $25M, but Bands Get Just $100.” TechCrunch, May 25. https://social.techcrunch.com/2019/05/21/how-sofar-sounds-works/.

- Cooiman, Franziska. 2022. “Imprinting the Economy: The Structural Power of Venture Capital.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221136559.

- Çalışkan, Koray. 2007. “Price as a Market Device: Cotton Trading in Izmir Mercantile Exchange.” The Sociological Review 55 (2_suppl): 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00738.x

- Çalışkan, Koray. 2009. “The Meaning of Price in World Markets.” Journal of Cultural Economy 2 (3): 239–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350903345462

- Çalışkan, Koray. 2020. “Platform Works as Stack Economization: Cryptocurrency Markets and Exchanges in Perspective.” Sociologica 14 (3): 115–142. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/11746

- Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. 2009. “Economization, Part 1: Shifting Attention from the Economy Towards Processes of Economization.” Economy and Society 38 (3): 369–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903020580

- Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. 2010. “Economization, Part 2: A Research Programme for the Study of Markets.” Economy and Society 39 (1): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903424519

- Doctorow, Cory. 2019. “The ‘Uber of Live Music’ Will Charge You $1100–1600 to Book a House Show, Pay Musicians $100.” Boing Boing, May 22. https://boingboing.net/2019/05/22/dont-pay-the-piper.html.

- Doganova, Liliana. 2015. “Que vaut une molécule? Formulation de la valeur dans les projets de développement de nouveaux médicaments.” Revue d’anthropologie des connaissances 9 (9–1): 17–38. https://doi.org/10.3917/rac.026.0017

- Doganova, Liliana, and Fabian Muniesa. 2015. “Capitalization Devices: Business Models and the Renewal of Markets.” In Making Things Valuable, edited by Martin Kornberger, Lise Justesen, Anders Koed Madsen, and Jan Mouritsen, 109–125. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eriksson, Maria. 2020. “The Editorial Playlist as Container Technology: On Spotify and the Logistical Role of Digital Music Packages.” Journal of Cultural Economy 13 (4): 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2019.1708780

- Eriksson, Maria, Rasmus Fleischer, Anna Johansson, Pelle Snickars, and Patrick Vonderau. 2019. Spotify Teardown: Inside the Black Box of Streaming Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Everts, Rick, Pauwke Berkers, and Erik Hitters. 2022. “Milestones in Music: Reputations in the Career Building of Musicians in the Changing Dutch Music Industry.” Poetics, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2022.101647.

- Everts, Rick, Erik Hitters, and Pauwke Berkers. 2021. “The Working Life of Musicians.” Creative Industries Journal 5 (1): 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2021.1899499

- Faulkner, Robert R. 2013. Hollywood Studio Musicians: Their Work and Careers in the Recording Industry. London: Routledge.

- Fleischer, Rasmus. 2017. “If the Song has No Price, is it Still a Commodity? : Rethinking the Commodification of Digital Music.” Culture Unbound 9 (2): 146–162. https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.1792146

- François, Pierre. 2004. “La maladie des coûts est-elle contagieuse? Le cas des ensembles de musique ancienne.” Sociologie Du Travail 46 (4): 477–495. https://doi.org/10.4000/sdt.29732

- Franssen, Thomas, and Olav Velthuis. 2016. “Making Materiality Matter: A Sociological Analysis of Prices on the Dutch Fiction Book Market, 1980–2009.” Socio-Economic Review 14 (2): 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu025

- Frith, Simon. 2017. “Are Workers Musicians?” Popular Music 36 (1): 111–115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143016000714

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 2017. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Routledge.

- Goffman, Erving. 1978. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Harmondsworth.

- Gomart, Emilie, and Antoine Hennion. 1999. “A Sociology of Attachment: Music Amateurs, Drug Users.” The Sociological Review 47 (1_suppl): 220–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03490.x

- Guibert, Gérôme, and Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. 2013. Musiques actuelles: Ça part en live. Paris: IRMA.

- Haynes, Jo, and Lee Marshall. 2018. “Reluctant Entrepreneurs: Musicians and Entrepreneurship in the ‘New’ Music Industry.” The British Journal of Sociology 69 (2): 459–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12286

- Hennion, Antoine. 1981. Les professionnels du disque: Une sociologie des variétés. Paris: Editions Métailié.

- Hennion, Antoine. 2014. “Playing, Performing, Listening: Making Music–or Making Music Act?” In Popular Music Matters. Essays in Honour of Simon Frith, edited by Lee Marshall and Dave Laing, 165–180. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Hennion, Antoine. 2017. “Attachments, you say? … How a Concept Collectively Emerges in one Research Group.” Journal of Cultural Economy 10 (1): 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2016.1260629

- Hesmondhalgh, David. 1997. “Post-Punk’s Attempt to Democratise the Music Industry: The Success and Failure of Rough Trade.” Popular Music 16 (3): 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000008400

- Hesmondhalgh, David. 1999. “Indie: The Institutional Politics and Aesthetics of a Popular Music Genre.” Cultural Studies 13 (1): 34–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/095023899335365

- Hesmondhalgh, David. 2020. “Is Music Streaming Bad for Musicians? Problems of Evidence and Argument.” New Media & Society 23: 3593. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820953541.

- Hesmondhalgh, David, Ellis Jones, and Andreas Rauh. 2019. “SoundCloud and Bandcamp as Alternative Music Platforms.” Social Media + Society 5 (4), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119883429.

- Hesmondhalgh, David, and Leslie Meier. 2018. “What the Digitalisation of Music Tells Us About Capitalism, Culture and the Power of the Information Technology Sector.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (11): 1555–1570. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1340498

- Heuguet, Guillaume. 2021. YouTube et les métamorphoses de la musique. Paris: INA.

- Hodgson, Thomas. 2021. “Spotify and the Democratisation of Music.” Popular Music 40 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143021000064

- Holt, Fabian. 2020. Everyone Loves Live Music: A Theory of Performance Institutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hracs, Brian J. 2012. “A Creative Industry in Transition: The Rise of Digitally Driven Independent Music Production.” Growth and Change 43 (3): 442–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2257.2012.00593.x

- Hracs, Brian J. 2015. “Cultural Intermediaries in the Digital Age: The Case of Independent Musicians and Managers in Toronto.” Regional Studies 49 (3): 461–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.750425

- Hracs, Brian J., Doreen Jakob, and Atle Hauge. 2013. “Standing Out in the Crowd: The Rise of Exclusivity-Based Strategies to Compete in the Contemporary Marketplace for Music and Fashion.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45 (5): 1144–1161. https://doi.org/10.1068/a45229

- Hracs, Brian J., and Johan Jansson. 2017. “Death by Streaming or Vinyl Revival? Exploring the Spatial Dynamics and Value-Creating Strategies of Independent Record Shops in Stockholm.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20 (4): 478–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517745703

- Hracs, Brian J., and Deborah Leslie. 2014. “Aesthetic Labour in Creative Industries: The Case of Independent Musicians in Toronto, Canada.” Area 46 (1): 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12062

- Hutter, Michael, and David Throsby. 2007. “Value and Valuation in Art and Culture: Introduction and Overview.” In Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts, edited by Michael Hutter, and David Throsby, 1–20. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jacca-Routenote. 2019. “Sofar Sounds Raise $25 m, but Will Artists See Any of That?” RouteNote Blog, May 22. https://routenote.com/blog/sofar-sounds-raise-25m-but-will-artists-see-any-of-that/.

- Janotti, Jr., Jeder Silveira, and Victor de Almeida Nobre Pires. 2018. “So Far, Yet So Near: The Brazilian DIY Politics of Sofar Sounds – a Collaborative Network for Live Music Audiences.” In DIY Cultures and Underground Music Scenes, edited by Andy Bennett, and Paula Guerra, 139–149. London: Routledge.

- Klein, Bethany. 2020. Selling Out: Culture, Commerce and Popular Music. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Langley, Paul, and Andrew Leyshon. 2017. “Platform Capitalism: The Intermediation and Capitalization of Digital Economic Circulation.” Finance and Society 3 (1): 11–31. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1936

- Laurent, Brice. 2011. “Democracies on Trial: Assembling Nanotechnology and Its Problems.” (PhD diss.). CSI Mines-ParisTech, PSL University.

- Lave, Jean. 1988. Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics and Culture in Everyday Life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Leyshon, Andrew. 2014. Reformatted: Code, Networks, and the Transformation of the Music Industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leyshon, Andrew, and Allan Watson. 2021. “User as Asset, Music as Liability: The Moral Economy of the ‘Value Gap’ in a Platform Musical Economy.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Industries, edited by Paul McDonald, 267–280. London: Routledge.

- Marshall, Lee. 2015. “‘Let’s Keep Music Special. F—Spotify’: On-Demand Streaming and the Controversy Over Artist Royalties.” Creative Industries Journal 8 (2): 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2015.1096618

- Marshall, Lee. 2019. “Do People Value Recorded Music?” Cultural Sociology 13 (2): 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975519839524

- McKenzie, Jon. 2002. Perform or Else: From Discipline to Performance. London: Routledge.

- Menger, Pierre-Michel. 2001. “Artists as Workers: Theoretical and Methodological Challenges.” Poetics 28 (4): 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(01)80002-4

- Miller, Peter, and Nikolas Rose. 1990. “Governing Economic Life.” Economy and Society 19 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085149000000001

- Morgan, Benjamin A. 2019. “Revenue, Access, and Engagement via the in-House Curated Spotify Playlist in Australia.” Popular Communication 18 (1): 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2019.1649678

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. 2015a. “Curation by Code: Infomediaries and the Data Mining of Taste.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 18 (4–5): 446–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415577387

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. 2015b. Selling Digital Music, Formatting Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Morris, Jeremy Wade. 2020. “Music Platforms and the Optimization of Culture.” Social Media + Society 6 (3), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120940690.

- Müller, Alain, and Loïc Riom. 2019. “À La Poursuite Des Objets Prescripteurs: Modes de Circulation de La Musique Dans Les Mondes Du Hardcore Punk et de l’indie Rock.” Territoires Contemporains 11. http://tristan.u-bourgogne.fr/CGC/publications/prescription-culturelle-question/Alain-Muller-Loic-Riom.html

- Moulin, Raymonde. 1995. De La Valeur de l’Art: Recueil d’Articles. Paris: Flammarion.

- Muniesa, Fabian. 2007. “Market Technologies and the Pragmatics of Prices.” Economy and Society 36 (3): 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140701428340

- Muniesa, Fabian. 2014. The Provoked Economy: Economic Reality and the Performative Turn. London: Routledge.

- Muniesa, Fabian, and Michel Callon. 2007. “Economic Experiments and the Construction of Markets.” In Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, edited by Donald MacKenzie, Fabian Muniesa, and Lucia Siu, 163–189. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Muniesa, Fabian, and Liliana Doganova. 2020. “The Time That Money Requires: Use of the Future and Critique of the Present in Financial Valuation.” Finance and Society 6 (2): 95–113. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v6i2.5269

- Muniesa, Fabian, Liliana Doganova, Horacio Ortiz, Álvaro Pina-Stranger, Florence Paterson, Alaric Bourgoin, Véra Ehrenstein, Pierre-André Juven, David Pontille, and Basak Saraç-Lesavre. 2017. Capitalization: A Cultural Guide. Paris: Presses des Mines.

- Muniesa, Fabian, Yuval Millo, and Michel Callon. 2007. “An Introduction to Market Devices.” The Sociological Review 55 (2_suppl): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00727.x

- Negus, Keith. 2013. Music Genres and Corporate Cultures. London: Routledge.

- Negus, Keith. 2019. “From Creator to Data: The Post-Record Music Industry and the Digital Conglomerates.” Media, Culture & Society 41 (3): 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718799395

- Nieborg, David B., and Thomas Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4275–4292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818769694

- O’Dair, Marcus, and Andrew Fry. 2020. “Beyond the Black Box in Music Streaming: The Impact of Recommendation Systems upon Artists.” Popular Communication 18 (1): 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2019.1627548

- Perrenoud, Marc, and Pierre Bataille. 2017. “Artist, Craftsman, Teacher: “being a Musician” in France and Switzerland.” Popular Music and Society 40 (5): 592–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1348666

- Perrig, Luca. 2022. “Les outils de l’intermédiation sur les marchés du travail de plateforme: Ethnographie des marchés de livraison de repas en Suisse Romande.” (PhD diss.). University of Geneva.

- Prey, Robert. 2016. “Musica Analytica: The Datafication of Listening.” In Networked Music Cultures: Contemporary Approaches, Emerging Issues, edited by Raphaël Nowak, and Andrew Whelan, 31–48. Cham: Springer.

- Prey, Robert. 2018. “Nothing Personal: Algorithmic Individuation on Music Streaming Platforms.” Media, Culture & Society 40 (7): 1086–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717745147

- Prey, Robert. 2020. “Locating Power in Platformization: Music Streaming Playlists and Curatorial Power.” Social Media + Society 6 (2), https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933291.

- Rendon, Francisco. 2021. “Sofar Sounds Acquires Ticketing Company Seated: Exclusive,” Pollstar, December 2, https://news.pollstar.com/2021/02/12/sofar-sounds-acquires-ticketing-company-seated-exclusive/.

- Riom, Loïc. 2020. “Discovering Music at Sofar Sounds: Surprise, Attachment, and the Fan–Artist Relationship.” In Popular Music, Technology, and the Changing Media Ecosystem, edited by Tamas Tofalvy and Emília Barna, 201–16. Cham: Springer.

- Riom, Loïc. 2021a. “Faire Compter La Musique. Comment Recomposer Le Live à Travers Le Numérique (Sofar Sounds 2017-2020).” Thèse de Doctorat, Paris: CSI Mines-Paristech, Université PSL.

- Riom, Loïc. 2021b. “Making Music Public: What Would a Sociology of Live Music Promotion Look Like?” In Researching Live Music: Gigs, Tours, Concerts and Festival, edited by Chris Anderson and Sergio Pisfil, 143–55. Waltham: Focal Press.

- Riom, Loïc. 2023. “(Un)Playing Music at Sofar Sounds: Some Elements of an Ethno(Musico)Methodology of Live Performances.” Ethnomusicology Review 24. https://ethnomusicologyreview.ucla.edu/journal/volume/24/piece/1098

- Rogers, Jim. 2013. The Death and Life of the Music Industry in the Digital Age. London: Bloomsbury.

- Seaver, Nick. 2022. Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Siles, Ignacio, Amy Ross Arguedas, Mónica Sancho, and Ricardo Solís-Quesada. 2022. “Playing Spotify’s Game: Artists’ Approaches to Playlisting in Latin America.” Journal of Cultural Economy, https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2022.2058061.

- Smith, Neil Thomas, and Rachel Thwaites. 2019. “The Composition of Precarity: ‘Emerging’ Composers’ Experiences of Opportunity Culture in Contemporary Classical Music.” The British Journal of Sociology 70 (2): 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12359

- Sofar Sounds. 2019a. “How Much Are Sofar Sounds Artists Paid?” Sofar Sounds, December 19. https://www.sofarsounds.com/blog/articles/how-money-works-at-a-sofar-show.

- Sofar Sounds. 2019b. “How to Make the Most of Your Sofar Sounds Set.” Sofar Sounds, August 28. https://www.sofarsounds.com/blog/articles/how-to-make-the-most-of-your-sofar-sounds-set.

- Sofar Sounds. 2020. “New Artist Improvements, Changes to Compensation and More.” Sofar Sounds, February 18. https://www.sofarsounds.com/blog/articles/new-artist-dashboard.

- Stahl, Geoff. 2001. “Tracing Out an Anglo-Bohemia: Musicmaking and Myth in Montreal.” Public 22–23: 99–121.

- Stahl, Matt. 2021. “Are Workers Musicians? Kesha Sebert, Johanna Wagner and the Gendered Commodification of Star Singers, 1853–2014.” Popular Music 40 (2): 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143021000301

- Stahl, Matt, and Leslie Meier. 2012. “The Firm Foundation of Organizational Flexibility: The 360 Contract in the Digitalizing Music Industry.” Canadian Journal of Communication 37 (3): 443–458. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2012v37n3a2544

- Stark, David, and Ivana Pais. 2020. “Algorithmic Management in the Platform Economy.” Sociologica 14 (3): 47–72. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/12221

- Tellmann, Ute. 2021. “The Politics of Assetization: From Devices of Calculation to Devices of Obligation.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 23 (1): 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2021.1991419

- Umney, Charles. 2016. “The Labour Market for Jazz Musicians in Paris and London: Formal Regulation and Informal Norms.” Human Relations 69 (3): 711–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715596803

- Umney, Charles, and Lefteris Kretsos. 2015. “‘That’s the Experience’: Passion, Work Precarity, and Life Transitions among London Jazz Musicians.” Work and Occupations 42 (3): 313–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888415573634

- Vachet, Jérémy. 2022. Fantasy, Neoliberalism and Precariousness: Coping Strategies in the Cultural Industries. Emerald: Bingley.

- Van Doorn, Niels, and Olav Velthuis. 2018. “A Good Hustle: The Moral Economy of Market Competition in Adult Webcam Modeling.” Journal of Cultural Economy 11 (3): 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1446183

- Verbuč, David. 2021. DIY House Shows and Music Venues in the US: Ethnographic Explorations of Place and Community. London: Routledge.

- Watkins, Elizabeth Anne, and David Stark. 2018. “The Möbius Organizational Form: Make, Buy, Cooperate, or Co-Opt?” Sociologica 12 (1): 65–80. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/8364

- Watson, Allan, and Andrew Leyshon. 2022. “Negotiating Platformisation: MusicTech, Intellectual Property Rights and Third Wave Platform Reintermediation in the Music Industry.” Journal of Cultural Economy 15 (3): 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2022.2028653

- Watson, Allan, Joseph B. Watson, and Lou Tompkins. 2022. “Does Social Media Pay for Music Artists? Quantitative Evidence on the Co-Evolution of Social Media, Streaming and Live Music.” Journal of Cultural Economy, https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2022.2087720.

- Wikström, Patrik. 2013. The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. Oxford: Polity.

- Zhang, Qian, and Keith Negus. 2021. “Stages, Platforms, Streams: The Economies and Industries of Live Music After Digitalization.” Popular Music and Society 44 (5): 539–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2021.1921909