ABSTRACT

Contemporary craft presents a conceptual difficulty for many Marshall Islanders, who struggle to construct definitions that rely on a clear-cut separation between culture and economy, in which craft is perceived to serve either cultural or commercial purposes. However, this article ethnographically illustrates that craft is an ambiguous construction. Its ambiguity stems from conflicting notions of culture and commerce, which is tied to valuations along the commodity – non-commodity spectrum. Marshallese craft was initially conceptualized locally and externally as something akin to tourist art aimed at an external other – that is, as commercial craft – but has since turned inwards to become culturally meaningful. Yet, despite this conceptual separation between commercial and cultural crafts, Marshall Islanders make, use, and circulate craft in ways that muddles such clear-cut categories. Instead, people see themselves and others as catering to economic and cultural needs at different moments using the same artifacts – a contextual alteration that contributes to a gradual shift in valuation. The ambiguity of craft therefore illuminates the continuous conceptual work of keeping culture and economy separated, a work that itself should be understood as a process of cultural production.

In June 2014, the women’s church group from Epoon (Ebon) was finally ready for their big performance in the United Church of Christ (UCC) at Laura in Mājro (Majuro), the main atoll of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). A large delegation had left Epoon a week earlier, and were now congregating with relatives living in Mājro for an evening of festivities. Over the preceding months, the group had raised money for the trip by organizing several refurnishing projects on private enclosures on Epoon. They had also collected cowrie shells on the ocean side reef, prepared clams that their husbands had foraged for them, and made mats, hand fans, mobiles, and various oils, all of which were to play a prominent part of their performance at Laura.

At the night of the performance, the women all wore similar patterned pink dresses, and they were all adorned with handcrafted jewelry, head leis, and perfumed balm. They all had hand fans that they used as props in their performance. After dancing their way into the church, the women sang a few songs before their grand finale. This was designed to imitate a traditional fishing method from Epoon in which the fisherfolk trap schools of fish in a circle of rocks on the lagoon reef. To mimic this scene, they placed their mats in a circle before ‘luring’ all the other gifts into the ring. This séance lasted a long time because of the vast amount of goods they had brought.

When it ended, the women started moving around in a circle, placing dollar bills on a chair before turning the chair towards the audience for them to donate their money as well. The audience partook, not only by donating money, but by dancing around themselves. This prompted some of the women to engage in over-exaggerated sexualized dancing, swinging their butts from side to side. The entire church erupted in laughter. While this went on, some of the women distributed goods from the fish trap among the crowd. Some of it, though, like the cowrie shells used in the amiṃōņo industry, were later sold and the money spent on communal purposes, the community in this case being defined as affiliates of the church.

This episode speaks to the multidimensional character of locally produced crafts (amiṃōņo) in terms of valuation, use, and purpose. Amiṃōņo consists of a range of plaited products (hand fans, handbags, jewelry, mats, wall hangings) made mainly from pandanus leaves, coconut fronds and leaves, and cowrie shells. These can be used to meet a range of different aims, whether economical, aesthetic, or social. Even when made with a specific ritual in mind as its ultimate purpose, it is never given whether it will meet that purpose best as a cultural artifact used in the ritual or as a commodity sold to cover expenses associated with the ritual.

A given object intended for personal use or as a ritual presentation can be gifted to someone else or sold at the market, to Marshall Islanders and tourists alike, if the particular circumstances call for money to be spent. Other times, as with the cowrie shells mentioned above, an item can feature in a ritual before being sold to raise money for the community, however defined. Craft therefore muddles the local models that construe culture and economy as conceptually separated realms or entities (both are reified in local discourse). This means that craft is an ambiguous construction for Marshall Islanders – as well as foreign observers – who struggle to construct clear-cut definitions of cultural and commercial craft. By taking the conceptual separation between culture and economy as an ethnographic vantage point, this article will analyze what this conceptual work does for Marshall Islanders in their quest for a meaningful life where self-reliance and cultural autonomy is the ultimate goal.

Methods and mission statement

The ethnographic material analyzed in this article, stems from a total of twelve months of fieldwork in the Marshall Islands and in a diaspora community on Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi. This includes a five-month stay on Epoon in 2014 – an outer atoll where the market economy is limited and from where I observed and documented material flows to and from Mājro – and five months of working with shopkeepers, weavers, and suppliers in Mājro in 2018. During that period, I conducted interviews with shopkeepers and suppliers, observed, learned from and engaged in numerous informal and semi-formal conversations with employed weavers, and documented the everyday workings of a craft shop, including the purchasing and selling of craft. I complement this material with a historical analysis of craft based upon a series of archival stints at the Pacific Collection at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Together, these approaches provide a unique vantage point for the study of value and cultural production in the Marshall Islands over the past century.

My main aim here is to analyze the ambiguous and multifaceted character of amiṃōņo by looking at how it is conceptualized, made, used, and circulated within a transnational field comprising the Marshall Islands and its overseas diaspora populations. I will show that amiṃōņo holds cultural significance for Marshall Islanders themselves, both as a unifying symbol, mediator of social relationships, and cultural practice. This perspective has been largely overlooked in the Marshall Islands context. The reason, I suggest, is that, owing to its initial introduction as a commercial enterprise, foreign observers and cultural conservatists often deem amiṃōņo inauthentic and something that compares negatively to so-called traditional craft. Amiṃōņo’s ambiguity therefore illuminates the continuous conceptual work of keeping culture and economy separated. This work should itself be understood as a process of cultural production, since grappling with tensions and internal contradictions like these allows conscious formulations and reformulations of what culture is (and does) and should be (and do).

My approach is centered on the relations between and mutual constructions of cultural practices and economic organization. My concern is with how culture and value are produced as outcomes of humans grappling with how to define and understand specific objects and their relations to them. That is, I am concerned with the conscious articulations of human actors. My approach also centers on the culture side of cultural economy, since the main emphasis in cultural economy studies has been on unpacking economy (Richardson Citation2019). I do this through an extended analysis not only of what culture means in research on economy (Cooper and McFall Citation2017), but in relation to economy. The point here is not only to show that objects move between different categories of valuation as they move in time and space, but that their valuation depends on the continuously shifting human uses of and perspectives on them. That is, an object’s valuation is not only an outcome of its biography (or its circulation history), but of conscious and unconscious attempts to grapple with individuals’ internal ambiguity stemming from shifting and contradictory perspectives.

For example, during an interview with a shopkeeper where I inquired about the contemporary role of craft, she first asserted that craft was solely a means to secure an income. She stressed that craft used to have utility purposes, but that it did not anymore. She elaborated her point by noting that ‘they’ (historical Marshall Islanders) used to make jaki (mats) because they needed clothes or flooring. That was not the case anymore, she claimed, saying something to the effect of ‘Now we [contemporary Marshall Islanders] have tiles where they used to have mats’. However, upon further reflection, she recognized that the only reason why there was a vibrant craft market in a place with so few tourists was that Marshall Islanders themselves were eager customers. This surely hints at a wider perspective than the purely economical, but she still hesitated to elevate contemporary amiṃōņo to the same cultural status as traditional craft.

Yet, she noted that contemporary Marshall Islanders indeed use jewelry, head leis, handbags, and hand fans, a realization she followed by suggesting that, ‘Maybe they want to promote culture’. What this shopkeeper was struggling with, was squaring the idea that a recent innovation with commercial gains can also represent authentic culture (see Theodossopoulos Citation2013). Her gut feeling told her that only the traditional craft has an internal meaning that justifies a classification as cultural objects. Yet, upon reflection, she was willing to grant contemporary amiṃōņo a partial cultural significance, at least as a means for ‘promoting’ culture. More important, she also opened the possibility that similar items can be interpreted differently by different actors, or even by the same person acting in different capacities, pointing out that while amiṃōņo might be predominantly economical for the person who sells it, it can serve other purposes for those who consume and wear it.

Herein lies the crux of what I analyze as a localized conceptual separation between economy and culture: People see themselves and others as catering to economic and cultural needs at different moments using the same artifacts – a contextual alteration that contributes to a gradual shift in valuation. That is, the ways in which people use, interpret, and define amiṃōņo differently in different situations means that specific items, designs, and craft types move back and forth between a predominantly cultural or a predominantly commercial frame of interpretations over time. In following these conceptual shifts, I analyze the ambiguity of amiṃōņo as a concrete expression of how culture is conceptualized differently in different contexts. As I will show, both Marshall Islanders build their definition of amiṃōņo around a conceptual separation between culture and economy in ways that resist the ‘total influence’ of a commodity logic by framing economic activities as being embedded in social relations.

Culture and commodities: a necessary background

At the heart of the culture/economy separation is what E. P. Thompson (Citation1961, 33) has called ‘the dialectical interaction between culture and something that is not culture’. That is, calling something culture – like the act of making and gifting a piece of craft – means that one is simultaneously calling something else by another name, for example economy – like the act of selling one’s craft at a craft shop – so as to separate them into two different realms. As Thompson elaborates, the act of distinguishing something as culture vis-à-vis something else deemed not-culture is an active process through which people are making history and, I add, producing culture. It is, moreover, an act of meaning-making, as defining something as culture is often the same as defining it as meaningful.

That culture is separated from economy means that Marshall Islanders tend to conceptualize it in a way that excludes acts of moneymaking so that the buying and selling of goods, for instance, is talked about as a purely economic endeavor and therefore something other than culture. This separation has many levels of expression, the mildest of which simply being a negation of all things economical when discussing culture. Other times, though, moneymaking, and its related notion of money dependency, is explicitly framed as the antithesis of culture (Berta Citation2022; Rudiak-Gould Citation2013). That is, money is commonly placed in a root-to-all-evil narrative where it is thought to encourage moral corruption, leading people to become selfish, stingy, and to abandon their families in pursuit of personal wealth. This stands in direct opposition to cultural ideals of sharing, generosity, and togetherness (Berman Citation2020; Carucci Citation1997; Rudiak-Gould Citation2013). From this viewpoint, the major issue with money is that it challenges subsistence living by pushing people away from a reliance on locally grown or caught foods, a form of self-sufficient sustenance seen to maintain communal togetherness by encouraging inter-household cooperation and a shared exploitation of local resources (Berta Citation2022).

It is important to stress that these are ideal representations. Elise Berman (Citation2020), for example, has expanded our understanding of ideals of sharing and generosity (jouj) by showing how people continuously help each other to avoid sharing, thereby bringing ethnographic nuance to ideal representations of cultural values. Yet, we also need to investigate what such ideal representations aim to do and what sort of social situation they address. This is where the friction between culture and not-culture becomes important. Such contestations over culture, what it entails and where it should lead, provide a multi-layered perspective on how people produce culture and construct a concept of the morally good, a construction that shifts according to the dialogic context and discursive aim.

Thus, when Marshall Islanders define certain phenomena, practices, and objects as cultural, they are not only making a statement about what culture is (and is not). They are also, more tacitly, saying something about what culture does. What culture does in relation to questions of craftwork as culture or commerce is to help in the pursuit of a meaningful life by constructing a sense of perseverance when faced with potentially disrupting changes. That is, (the idea of) culture becomes a framework for thinking about and dealing with contemporary social issues tied to migration, dislocated communities, and economic hardship. This concern is essentially Polanyian in the sense that it could be read as a worry over the extent to which their economic pursuits, like the buying and selling of craftwork, are embedded in social relations (Polanyi Citation2001, 60). Contestations over whether craft is culture or commerce are not concerned with commodity exchange in itself, since that has always been part of social life in the Marshall Islands, but with the extent its ‘structural consequences [are] able to influence the total outer and inner life of society’, as Georg Lukács (Citation1967, 66) put it.

Craft is important because it allows Marshall Islanders to resist the ‘total influence’ of commodity exchange. They do so not by engaging in something that can be theoretically framed as something other than ‘economy’ but by calling their economic pursuits by another name, culture. That is, even when trading with money and selling their craftwork at the market, Marshall Islanders are resisting commodity fetishism while embracing a fetishization of culture. This is not a complete refusal of everything economical, but an assertion of control over one’s economic relations – a ‘double movement’ safeguarding of an embedded economy (Polanyi Citation2001, 136). Craft is crucial because it provides an opportunity for people to engage in moneymaking on their own terms while also fueling the idea that they are preserving culture.

Framing the ambiguity

The discussion over whether amiṃōņo should be understood as commercial or cultural objects is intimately connected to notions of authenticity, to which only objects and goods deemed ‘cultural’ are ascribed. This is a dominating local perspective that relies on a distinction between the indigenous and the introduced, a distinction that is often reproduced in the regionally specific literature (Taafaki and Fowler Citation2019; Udui Citation1964; Wavell Citation2010; Citation2016). The premise underlying this distinction seems to be that the so-called traditional crafts are thought to provide an unambiguous representation of authentic culture, whereas commercial crafts are deemed inauthentic (see Cohen Citation1988, 375; Myers Citation2001, 19). This is a problematic distinction because it ascribes objective meanings to objects, as if they embody eternal meanings irrespective of context, which they not always do (Graeber Citation2001, 163; Thomas Citation1991; Citation2015).

When pointing out this problematic I am aware of the ‘trap of authenticity’ lurking in the background. As Dimitrios Theodossopoulos (Citation2013, 344) has described it, the trap of authenticity appears when scholars are (unwittingly) reproducing the authentic/inauthentic distinction in an attempt to explain local meanings and uses of authenticity. The idea is that, in their haste to deconstruct romanticized views of authenticity grounded in the past (often in relation to culture and cultural expressions), scholars end up defending contemporary expressions and practices as no less authentic than their historical counterparts. The result is the reproduction of the idea that there really is such a thing as an authentic cultural expression. It is therefore important to stress that when I dismiss the distinction between indigenous and introduced and its connection to ideas of in/authenticity, I am not defending (nor rejecting) the status of contemporary amiṃōņo as authentic. Rather, I am calling attention to authenticity’s conceptual ambiguity by pointing to the contradictory ways in which Marshall Islanders conceptualize amiṃōņo in relation to real or authentic culture (lukkuun ṃanit). Such context-specific conceptualizations are important to understand authentication as a process directly related to cultural production.

The term amiṃōņo is commonly translated and spoken of as handicraft. This is partly due to its relatively recent inception, which was encouraged by encounters with foreign others and ultimately institutionalized by the Japanese colonial administration (1914–1944). The 1920s and 30s saw the introduction of new raw materials, new designs, and ultimately new artistic expressions. Many therefore see this period as one characterized by a shift in orientation from cultural to commercial crafts. The implication is that craft made for and sold at the market cannot have cultural significance. Indeed, a report on the craft industry and resource use casts amiṃōņo as ‘arts of acculturation’, pointing out that ‘The majority of handicraft produced today are, with some exceptions, no longer an integral part of the traditional culture’ (Vitarelli Citation1986, 2; see also Udui Citation1964; Wavell Citation2010).

Despite its contemporary commercialization, amiṃōņo is usually considered with pride among Marshall Islanders, who also make up the bulk of the customer base. There is, though, a meaningful distinction to make between rural, urban, and diaspora Marshallese in this respect. Outer islanders make, sell, and use (wear, display, gift, etc.) amiṃōņo, but they do not generally purchase it for money. Urbanites, too, make, sell, and use amiṃōņo, but many also buy it for their own consumption or to use as gifts. The three major reasons for this are limited access to raw materials, time constraints, and lack of skills. Finally, amiṃōņo is in high demand in diaspora communities, where it serves as material expressions of cultural belonging more conspicuously than in the RMI itself (see also Hess, Nero, and Burton Citation2001). Diaspora Marshallese also use it in different ways and for different purposes, for example as Christmas presents and home decor.

More than mere souvenirs made for an external consumer, then, amiṃōņo is central to a range of practices among Marshall Islanders themselves, such as interpersonal gift exchange, ceremonial tributes, personal adornment, home displays, economic survival, a means of payment, and symbolic performances of cultural belonging. That is, Marshall Islanders use amiṃōņo to make money by trading it in the shops, but they also use it to mediate social relationships within and beyond their home reefs. Crucial in this respect is that the same class of artifact can be used for all intended purposes. There is no separation between the type of amiṃōņo used for market trade or interpersonal gifts and no distinction between amiṃōņo aimed at an internal and an external audience.

This refusal of established categories tied to audience, consumers, and purpose makes amiṃōņo a peculiar construct within the craft literature, serving as a clear example of what Erik Cohen (Citation1988, 379–80) has called ‘emergent authenticity’ (see also DeBlock Citation2018). This is a process in which what starts out as a purely commercial endeavor, for example as souvenirs made to satisfy a colonial administration, can come to be seen as authentic cultural expressions over time. However, I argue that this process is never fully complete and that its local appropriation does not entail a restriction from the commercial realm.

Unlike most other forms of ethnic craft, Marshallese amiṃōņo made for internal and external purposes are materially, ritually, and aesthetically the same. Rather than using different types of artifacts for different purposes, a particular item’s use and valuation change with the situation in ways that highlight the interdependent relation between craft and context. Amiṃōņo can be defined by its context of valuation, but it can also help to define or redefine contexts (see also Cant Citation2019, 37; Myers Citation2001, 17–20). For example, the contemporary commercialization of craft could potentially serve to define amiṃōņo in solely economic terms, which could hinder its claim to cultural authenticity.

Yet, the conspicuous display of craft by Marshall Islanders in town can help people redefine their urban situation from one characterized by cultural decline to one characterized by cultural vitality. The importance of this was confirmed publicly through a range of campaigns, cultural events, craft expositions, and in public speeches celebrating the cultural perseverance (Berta Citation2022). Amiṃōņo was omnipresent in these arenas. Several of the storeowners I worked with claimed that their businesses were important for cultural preservation because it kept traditional knowledge alive, a sentiment echoed by many of their customers. For example, events like One Island One Product, a combined cultural exposition and market fair that I witnessed in Mājro in 2018, were widely praised, by government officials as well as ‘ordinary’ Marshall Islanders, for the way in which it brought Marshallese culture to urbanites. Indeed, my experience from Mājro confirms what others have shown from the U.S. diaspora (Hess, Nero, and Burton Citation2001, 91), that access to amiṃōņo and other cultural goods (food, oils, etc.) provides a form of social capital because it shows a maintenance of ties to one’s home atoll.

The tendency to link contemporary use of amiṃōņo to cultural preservation could be understood as what Hugo DeBlock (Citation2018, 100–101) calls an authenticating process, a process in which artifacts are made authentic by being used, made, and displayed in what people recognize as culturally appropriate ways. The conceptual work put into such constructions also helps Marshall Islanders to take ownership of amiṃōņo as an internally meaningful artistic expression, framed as a key part of female creativity, kōrā im an kōl. The fact that these products are handmade makes the conceptual work of framing craft as cultural easier. Yet, as I will show below, the material-labor configuration motivating the authenticating process owes more to the uses of and organization of labor put into making amiṃōņo than the handmade quality of the products.

Contemporary crafts are therefore entangled objects subjected to a wide range of social transformations in which the outcome can mean differing valuations (Myers Citation2001, 54; Thomas Citation1991, 28). On the one hand, amiṃōņo holds what Arjun Appadurai (Citation1986, 13) has called a ‘commodity potential’ in the simple sense that they can potentially be exchanged for some socially acceptable equivalent. On the other hand, it also holds a potential to be something other than a commodity, as defined by the social relations that mark specific moments in an artifact’s social biography and from which its valuation is a result (Graeber Citation2001, 32; Gregory Citation1997, 47; Thomas Citation1991, 29). This inherent capacity for both commodity and non-commodity forms goes to the heart of the separation between culture and economy and is an important part of what makes amiṃōņo an ambiguous construction.

The issue here is that even if amiṃōņo sometimes appear to circulate according to an abstract commodity logic, a point that underscores its particular classification as commercial, it does not always follow that same logic. It is therefore analytically uninteresting to note that craft has a ‘commodity potential’ in the sense that it can be exchanged for money or goods of equal value. What matters are the social consequences of craft potentially becoming subject to commodity exchange, that is, whether buying and selling craft at the market contributes to notions of an economy disembedded from social relations.

Therefore, I am less interested in analyzing moments of transaction than I am in analyzing how amiṃōņo is made, circulated, and used. This is crucial because it is not necessarily the case that things have social histories, even if we can trace their movement in time. Sometimes, the thing itself can be forgotten while the act of presentation lingers in permanently established relationships. This is true of the ritual exchanges that begins this article: The volume and quality of the things presented were important in the moment, but it was the act of being together, of playing out the fishing scene and redistributing the catch while making hysterically animated sexualized jokes that reconstituted the relationships that comprised the church community. Indeed, many of the items given were later sold to the amiṃōņo shops without posing a threat to the perceived unity of the community.

Conceptual disagreements

Amiṃōņo’s ambiguity stems from conflicting notions of culture and commerce, which, in turn, is tied to valuations along the commodity – non-commodity spectrum. Amiṃōņo was initially conceptualized among both Marshall Islanders and their visitors as something akin to tourist art aimed at an external other, but has since turned inwards to become culturally meaningful. Having served as a symbol that reifies cultural and ethnic differences between Marshall Islanders and various cultural others, amiṃōņo has become a material symbol of an internally shared cultural identity. However, to be economically sustainable, contemporary life on outer atolls relies on the continuous manufacture of amiṃōņo (and other cultural goods) for the market. This makes amiṃōņo conceptually difficult since market sales are typically conceptualized as something other than culture.

A discussion I once had with a group of employed weavers is particularly illuminating. One day I was sitting with them in their workspace, an older lady came into the shop. She looked around for a bit before one of the weavers asked her if she had any amiṃōņo to sell. She did not, she said, but revealed that she had a sleeping mat (jaki) to sell. The mat was nicely adorned with colorful patterns, but not exceptional. Yet, the old lady had operated with a clear distinction between amiṃōņo and jaki. I had never heard it made so concretely before (most items are called by their names and jaki is always part of larger amiṃōņo displays), and as far as I knew mats had always been an article of exchange, internally and externally (Kotzebue Citation1821, II:9, 57; Lévesque Citation1992a, 517; Citation1992b, 84, 185). More important, this was a jaki made in the contemporary style, and therefore not visibly similar to the clothing mats made in the 1800s, a style that had been recently revived as jaki-ed (see below).

When I asked the weavers about it, it sparked a discussion in the group. Kajak agreed with the distinction made by the visitor: jaki was not amiṃōņo, she said. The shopkeeper agreed. None of them could explain why, though. Kajak begun to say something about how jaki is made from pandanus whereas amiṃōņo is made from coconut fronds, but quickly realized that this was an insufficient explanation. Most of that day, we had been occupied making head leis from pandanus leaves as part of a large overseas order for a Pacific festival, an order that definitely fit the amiṃōņo description. Still, she maintained her position. One of the other weavers, Leea, disagreed with her, saying that jaki was obviously also amiṃōņo. Neither she could explain why. Nobody ever elaborated their respective arguments, but I see their disagreement in relation to a larger disagreement over the relationship between amiṃōņo and culture. For example, Kajak was firm in her assertion that amiṃōņo was all about economic survival and not about culture, whereas Leea was more hesitant.

Kajak seemed to be wrestling with an implicit distinction between cultural and commercial craft, a distinction that makes amiṃōņo intrinsically ambiguous. Like the shopkeeper mentioned earlier, Kajak’s gut feeling seemed to cast amiṃōņo as commercial craft and therefore too far removed from historical crafts to be authentically cultural. Yet, she surely does not understand it as ethno-kitsch either. Articles like jaki therefore pose a conceptual problem.

On the one hand, they use the same materials as traditional craft (as Kajak herself noted) while remaining in widespread use among both rural and urban Marshall Islanders. On the other hand, they are clearly also made and sold for commercial purposes in ways indistinguishable from other kinds of craft. It is easier to see objects like wall hangings and ornaments as pure commercial craft – even if they, too, are in widespread local use – than is the case with objects like mats or hand fans even if their contemporary expression looks distinctly different from their historical counterparts. Even so, there is a tension between creativity and authenticity that comes to light through conceptual disagreements over craft as culture or commerce.

My argument is that there are three key sources for this tension. One concerns a perceived difference between historical and contemporary craft and how these relate to commercialization. The other concerns the ways amiṃōņo is used and valued among Marshall Islanders. The third concerns the craftwork itself, that is, the labor process involved in craft manufacture. While many still grapple with a clear-cut distinction between cultural and commercial craft, these factors have helped to blur the boundary between craft made for local use and appreciation and those made for commercial purposes. For the past 150 years or so, Marshall Islanders have commodified previous utility or status objects while appropriating and making internally meaningful new innovations initially aimed to please a foreign other. In the following, I will analyze these three sources for ambiguity before discussing how they affect the conceptual separation between culture and economy.

Ambiguity stemming from varying use and ideas about authenticity

When foreign visitors began to take an interest in local crafts, Marshall Islanders saw an opportunity for trade. In addition to trading in traditional exchange goods like mats, necklaces, and belts, they began to develop new things aimed to meet foreign preferences like Panama-style hats and tobacco bags, items made explicitly for trade. However, it is also clear that Marshall Islanders quickly adopted these innovations themselves (e.g. Erdland Citation1914, 28). As new trends developed and new materials came to dominate, old and familiar items, too, changed in accordance with the new style. The result is that contemporary jaki, jewelry, and hand fans are made in a completely different style today than in the late 1800s. This in itself is not surprising, of course, given that aesthetic expressions change over time, but it is worth mentioning because their affiliation with historical equivalents tend to grant them a cultural significance unmatched by things like the contemporary wine holders and wall hangings.

Yet, contemporary crafts with a strong claim to cultural continuity is also questioned when compared directly with their historical equivalents. When sharing photos from the Brandeis collection in Freiburg of craft collected at the turn of the nineteenth century with a shopkeeper in Mājro over e-mail in 2021 (see ), she compared it to the contemporary kind by referring to the latter as a ‘ru$h, ru$h job’. Her implication was that contemporary artisans are guided by monetary rather than aesthetic incentives and that this was visible in the high level of craftmanship in the old artifacts. However, many of the photos showed what was then new innovations developed for a booming market (Krämer and Nevermann Citation1938, 228). That is, their innovation was stimulated by the prospect of monetary income by meeting the needs of foreign customers. But these market conditions also gave people an incentive to repurpose and therefore keep making products that was fast disappearing from everyday use, such as clothing mats (nieded).

Figure 1. Two tobacco bags collected by Antonie Brandeis in the early 1900s while her husband Eugen Brandeis served as Imperial Governor in Jālwōj for the German administration. The bags are part of the Brandeis collection at the Museum Natur und Mensch in Freiburg, Germany. Inventory numbers II/1329 and II/1327. Photo: Author.

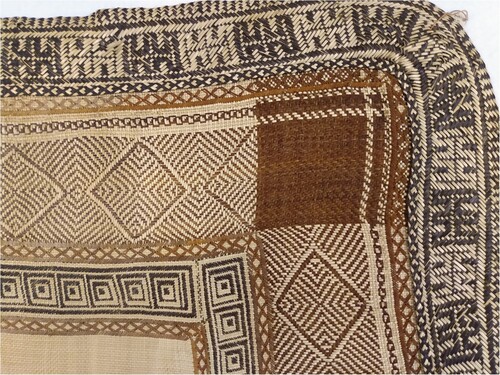

Mats provide a particularly telling example of an entangled object (Thomas Citation1991). Most mats described or kept from the nineteenth century, whether for clothing, sleeping, or sitting, were squared with rounded corners with intricately plaited borders and bands of varying width moving inwards towards the center, all colorfully adorned with different geometrical patterns (see ). Those made for clothing were roughly 90 times 90 cm (they were worn in pairs, one wrapped from the front and one from the back) while those made for sitting and sleeping were often approaching 200 times 200 cm. Even after clothing mats fell out of style, they remained an important commodity in the tourist and museum collection trades (Erdland Citation1914, 108), and weavers kept incorporating new design patterns like the German Iron Cross (Erdland Citation1914, plate 7).

Figure 2. Details of a nieded in the Brandeis collection of the Freiburg Museum Natur und Mensch. Inventory number II/1254. Photo: Author.

Photos from the German era reveal that settled traders, missionaries, and administrators used former clothing mats as tablecloths in their homes and offices (e.g. Mückler Citation2016). Such use prompted the development of a smaller, more rectangular mat marketed as tablecloth and made explicitly for the export market. These have persisted in the commercial market until today (see ). To the degree that the squared mat remained in local use, it was as sleeping mats for infants (Spoehr Citation1949, 146). However, it seems to have all but disappeared around the 1950s, to the point that none remained in circulation and its technique was lost to a younger generation of weavers.

Table 1. Development of commercial amiṃōņo items over time. 1946 from Mason (Citation1947, 139), 1947 from Spoehr (Citation1949), 1982 from Wells (Citation1982), 2004 from Lanwi (Citation2004, 211–112), 2006 from Mulford (Citation2006), and 2018 from the author’s fieldnotes.

Meanwhile, a different kind of rectangular sleeping mat developed for both local use and commercial purposes. In the beginning, weavers took creative inspiration from the earlier clothing mats, with intricately patterned borders (e.g. Spoehr Citation1949, 147), but they eventually created new styles and color schemes adorning the entire mat. These newer designs are known as jañiñi and sometimes jejaki (Taafaki and Fowler Citation2019, 51, 53), but are more commonly called by the general term jaki. Though skillfully made, they are undeniably coarser than the earlier clothing mats, nieded. It seems that the commercial market played an important role in this artistic shift. The demand for nieded had decreased during the Japanese era and there was a growing dissatisfaction among weavers about the price it fetched. This was also true in the early days of U.S. naval rule, when mats were among the most underpriced items, resulting in a general reluctance to produce them among weavers (Mason Citation1947, 132, 140). Considering that it was its commoditization that had kept it alive in the first half of the 1900s, it is not surprising that it eventually disappeared once market conditions changed.

In the early 2000s, a cultural revival program organized by the University of the South Pacific (USP) campus in Mājro set its aim at the old mats, now generally known as jaki-ed (Taafaki and Fowler Citation2019). The weavers in the program studied photos of nineteenth century mats held in various overseas museum collections from which they reinterpreted designs and aesthetic expression. The contemporary jaki-ed is therefore a reappropriation of older nieded even if it is clearly its own thing. One of the most striking differences between the contemporary jaki-ed and its historical counterpart is the ways in which the jaki-ed has been removed from the popular craft market into something more akin to ethnic high art (see Chibnik et al. Citation2004). That is, it is made as art by intention (Errington Citation1998, 83), sold only at annual auctions and meant to be framed and hung on a wall. Of course, something similar happened to the historical nieded in ethnographic museums as well, but that is best thought of as art by appropriation (Errington Citation1998, 84), a process in which utility objects become art by being removed from its original use and context to serve as display objects in museums and galleries.

These forms of shifting valuation, when certain objects become commoditized and even metamorphosed into art, play into peoples’ conception of culture and its artifacts. The revival of the jaki-ed has helped to elevate the cultural significance of weaving in general. At the same time, it has made the category amiṃōņo more ambiguous because it has made the distinction between cultural and commercial craft more pressing. One outcome is exemplified in Kajak and Leea’s disagreement over how to classify the regular sleeping mat. Such conceptual disagreements are, ultimately, disagreements over conceptualizations of culture.

Both Kajak and the shopkeeper mentioned above were prone to conceptualize amiṃōņo in its restricted, commercialized sense, as something other than culture. However, they both experienced trouble defending their position once they were asked to elaborate their argument or explain their reasoning behind it. A key reason for that is the fact that Marshall Islanders have engaged in elaborate commercial craft sale for more than a century. During this period, various items have appeared and disappeared (), and some have been appropriated locally while some have catered mainly to foreigners. Whether understood as culture or not, amiṃōņo has been a vital part of life in the Marshall Islands for at least four generations.

When the Japanese initiated a formal craft industry in the 1920s, more items were developed such as wall hangings, pocketbooks, and cigarette cases. These were likely the types of artifacts that the Japanese economist Yanaihara Tadao (Yanaihara Citation1940, 150) was referring to when he commented that the amiṃōņo made in the Marshall Islands were ‘little used by the islanders themselves’, that the weavers did it ‘as a duty owed to the Government’, and that ‘the art has no vocational value’. With that, he pinpointed a sentiment that would continue to color foreign observers’ view of amiṃōņo for decades to come.

Yet, the industry kept increasing in terms of turnover and variety of items produced. As captured in , there has been a steady increase in design innovations since the Second World War. What it does not capture, though, is the variety of designs hidden within each category listed. I have separated the Likiep fan from other hand fans and the Kōle bag from other handbags because of their fame, but recent years have seen the development of items that might reach similar appreciation with time, like the Lae fly and the Utrōk bukwekwe jewelry sets. These are both included in the category ‘jewelry’ in the same way that numerous different designs are included under ‘turtle decorations’ or ‘handbags’. The point is that the amiṃōņo pool is expanding and that it mainly does so to accommodate the needs and aesthetic preferences of Marshall Islanders living in urban centers or overseas.

It is clear that the continuation of the amiṃōņo industry relied on a number of administrational incentives from the Japanese and American colonial governments. This necessarily included establishing a pricing system that weavers deemed fair, lest they abandoned the trade. Yet, it is equally clear that the production of craftwork, whether its design was new or old, was always important in ritual contexts. However, the type of items made for things like ceremonial gift-giving, internally as well as externally, were replaceable. This means that the border between different forms of craft have long been fluid.

Alexander Spoehr’s (Citation1949, 234) work lends support to the idea that amiṃōņo needed external stimuli. He noted that, in 1944, a group of fifty-nine women from Mājro had formed a weaving cooperation in a successful attempt to ‘getting the women interested in handicraft again and in stimulating production’. But he also observed that what he called ‘women’s handicraft’ was either used by the maker’s household, sold to the U.S. Commercial Company, or given to visitors, particularly U.S. officials (Citation1949, 139–40). Craft was also an integral part of first birthday celebrations (keemem), as close relatives of the baby brought gifts of craft that more distant relatives would bring home when leaving (Citation1949, 209). It is therefore reasonable to assume that Spoehr’s remarks about getting women interested in handicraft again means getting them interested in commercial trade of craft and not craft-making itself.

By the 1940s, amiṃōņo was an important means for mediating a range of different relationships, internally as well as externally. For example, in May 1945, after Lieutenant Burton B. Bales was killed by enemy fire during the evacuation of Jālwōj (Jaluit), Marshall Islanders responded by sending gifts of amiṃōņo to his widow (Richard Citation1957, 358). The month before, in commemoration of the one-year-anniversary of U.S. occupation of Utrōk (Utrik), the islanders presented so much amiṃōņo to the Navy personnel that their income had been cut in half. This forced them to violate military regulations and take up credit extensions in the local shops (Richard Citation1957, 413). Finally, a navy lieutenant leaving Kuwajleen (Kwajalein) was ‘unexpectedly presented with a score of handicraft articles’ from his Marshallese hosts. When he expressed his surprise, he was met with the words, ‘This is an old Marshall custom, to give presents to our friends when they leave; it's a habit which is hard to break’ (Mason Citation1947, 105). Together, these examples illustrate that, since the Second World War at least, Marshall Islanders have used craft in ways that refuses reductive categorizations as either culture or commerce.

More than merely a medium to secure cash, craft has served as a medium to fulfil social obligations. The attempts made by both foreign observers and Marshall Islanders to draw a sharp distinction between commercial and cultural craft have their roots in prevailing ideas about culture as separated from economy. These ideas are particularly conspicuous among those who are aware that contemporary amiṃōņo was first introduced to meet commercial purposes. By extension, this has led to an ideal separation between historical and contemporary craft in which the latter is more strongly associated with commercial than cultural production. Yet, these distinctions break down when considering how traditional crafts, too, have been commercialized for centuries and how recently developed crafts have been incorporated into ritual presentations with long historical roots. Even if its techniques and artistic expressions are relatively new, its uses are old. This makes it difficult to dismiss it as something properly cultural – a dismissal that becomes all the more difficult when considering the labor process put into its manufacture.

Ambiguity stemming from labor and positionality

Cultural commodities in the Marshall Islands gain much of their cultural content through its labor process, from the collection of raw materials to their manufacture. The relevant form of labor organization – where work is governed by moral obligations of mutual aid, most often in the form of inter-household cooperation – allows outer atoll dwellers to claim a strong affiliation with culture (Berta Citation2022; but see also deBrum Citation2004). Whether conducted with monetary compensation in mind or not, craftwork resembles cooperative community projects, fishing, cooking, and other kinds of subsistence work in that it remains embedded in social relations. This form of work can be favorably contrasted to wage labor and other kinds of moneymaking that individuals can (or must) engage in outside of their wider network of relational obligation, as is usually the case in town or overseas.

Most Marshall Islanders know and appreciate the different kinds of labor and knowledge transition that each piece of amiṃōņo embodies. Craftwork typically utilizes a range of labor constellations across generations, genders, and kin groups. Children often gather pandanus leaves or collect small cowrie shells in the lagoon, while men dive for larger shells and other sea products used. Even if most weavers could plan and execute every single step of the work process on her own, craftwork is usually not a solitary work, as weavers will often team up to work together, side by side. This makes the task more tolerable and ensures a positive feel to the otherwise tedious work. It might be that only one woman is weaving, but she nevertheless enjoys the company of others, whether they are cooking, doing laundry, or entertaining them with joyful stories. Accordingly, the creation of amiṃōņo is no different from other kinds of household work in that the women who engage in it seldom work alone, but within a social environment that turns chores into more pleasant activities.

While women of all atolls make a range amiṃōņo such as mats, fans, necklaces, and handbags for everyday and festive usage, not everyone weaves for the commercial market. Even if the quality and aesthetic expression of what they make equals that found in the Mājro craft shops, their creations have a purpose more akin to utility craft in the sense that they are made for personal consumption rather than sale. Indeed, the widespread production and use of non-commoditized amiṃōņo articles refutes the claims put forth by the shopkeeper discussed above. Rather than merely promoting culture, as she put it, women who use and adorn themselves with contemporary crafts are performing culture in the same way as their ancestors were when they used their jaki as clothing or flooring.

It is important to stress that, for outer atoll weavers, the products made and the labor processes involved are indistinguishable whether they are producing for the market or for their own consumption. Indeed, much of the amiṃōņo that is in circulation never pass through a shop but is made for and presented in interpersonal gift-giving or ritual celebrations. Amiṃōņo feature as gifts or tributes in most ceremonial gatherings (keemem, Christmas, large church events, etc.), like the church event that opens this article. In all such cases, crafts have been prepared in advance and ritually distributed among a predominantly Marshallese audience.

Together with the everyday usage of amiṃōņo adornments, such ritual performances and celebrations are important for understanding the multidimensional valuations of craft in particular and the commodities that comprise the economies of culture in general. Again, most Marshall Islanders, whether rural or urban, at home or abroad, know and appreciate these multiple uses and purposes. The link between amiṃōņo and culture is not about the thing itself, but about the types of labor and social relations it embodies – relations that come to life through the act of giving, since very few people buy or make amiṃōņo for themselves. Such evocations do not hinge on whether the piece at hand was bought in a craft shop or made by a relative. What matters is the act of giving and the sense of tradition and belonging that the items evoke in its audience. It is worthwhile to take a step back to reflect on the different types of localities that Marshall Islanders inhabit because these become contexts through which they approach the valuation of craft.

On outer atolls, craft and craftwork are more mundane and ever-present than in in town or overseas. Though important and highly valued, it is also taken for granted, as people have ready access to raw materials and ample time to weave. While craft is undeniably commercialized in the sense that people center much of their economic endeavors around it, outer atolls do not provide contexts in which craft is directly transacted for money. Instead, it is either traded for food in local shops or sent to town where relatives typically use the cash collected to purchase imported goods that they ship back. Moreover, craftwork remains socially embedded in ties of relational obligation. This is not the case in either of the other localities.

Though weaving remains an important economic activity in town, its labor relations shift to become more restricted and individualistic. A key reason for this, is that raw materials are scarce and therefore mostly imported from outer atolls, or even purchased in craft shops, which means the elimination of key elements of its labor process. In diaspora communities, this elimination is further extended to include weaving itself. Instead, their engagement with crafts is largely restricted to complete pieces. For both urbanites and diaspora people, then, the labor relations that amiṃōņo embodies have to be consciously invoked and articulated rather than experienced on an everyday basis. The storeowners I worked with in Oʻahu made this point clear when they explained that their aim when setting up shop was to build a tangible community around their store by providing a secular space for people to congregate, something they hoped would help people struggling with homesickness (oñ). This included providing the diaspora community with desirable goods from the Marshall Islands.

Even if urbanites living within RMI waters are more intimately connected to the craft trade than their diaspora counterparts, they too consume craft in a setting where it is dislocated from its labor process and the mishmash of relational obligation that includes. Yet, urbanites can construe their consumption as a source for cultural preservation because they know that it helps to make outer atoll life economically sustainable and because it allows them access to culturally meaningful objects in a context where those are generally thought to be lacking. That was a point frequently brought home by people questioning why I was in Mājro if my aim was to study culture, pointing out that ‘true culture’ resides in the outer atolls. However, those same people often expressed their appreciation for the ways in which local craft stores contributed to cultural preservation. Naturally, this was a narrative that the craft stores could get behind, and most of them explicitly marketed themselves in a similar vein, claiming that their commercialization of craftwork kept the art and knowledge alive.

Different contexts for valuation

The commercialization of amiṃōņo is more conspicuous in town than overseas on account of the prominence of craft shops and the role these play in the circulation of craft. While much of the amiṃōņo circulating in diaspora communities have been filtered through these shops before crossing international borders, it is meaningfully removed from this commercial context. This means that, even if it is true that the diaspora context is furthest removed from the labor relations involved in the creation of craft, this is somewhat overshadowed by its removal from commercialization since such a removal allows people to emphasize the social relations involved in circulation rather than creation.

Through concrete transactions, amiṃōņo embody relations that bind diaspora people to their extended families and, more generally, to what many still perceive as a homeland. Such transactions are vital for maintaining lasting relationships across a transnational social field, from outer atolls through transit centers in town to the diaspora.

Together, these different localities, classified roughly as rural, urban, and diaspora, provide three different contexts for valuation of craft. All these valuations are ambiguous in their attempts to delineate amiṃōņo clearly within a framework that rests on an opposition between culture and commerce. Each locality presents different conceptual problems to tackle by emphasizing varying degrees of culturally appropriate ways for making and using craft, ways that help people to downplay the commercial side of craft-making.

Outer atoll dwellers therefore stress the ways in which craftwork fit into larger patterns of subsistence work and self-reliance, urbanites engage in conspicuous consumption in everyday life as well as public events and expositions (and are therefore engaged in ‘promoting culture’), while diaspora islanders emphasize the social relations and cultural traditions that amiṃōņo represents for them (Hess, Nero, and Burton Citation2001, 91). Again, it is important to stress that these are not clear-cut strategies that only hold relevance in their given localities. Labor, use, and symbolic representations are important aspects of valuation throughout this trans-local landscape. I am merely pointing to the most relevant or powerful one in each locality.

Together or alone, labor, use, and symbolism present a conceptual framework for construing craft as culture. Without them, such understandings are difficult to uphold. I argue that this is exactly why shopkeepers and employed weavers display so much ambivalence towards amiṃōņo. For them, weaving is just like any other kind of wage labor, with minimum wage regulations, taxes to pay (stand-alone weavers sell their crafts tax-free), set working-hours (having to physically punch in and out), and orders to fill (which could mean long periods of tedious and unfulfilling work). Those who manage to find time to weave at home often sell what they make at work. This means that they seldom make craft for non-commercial purposes, which further restricts its symbolic and relational force.

In other words, craft shop employees are steeped in commercial craft production in a way others are not. This may be part of the reason why Kajak was so firm in her assertion that amiṃōņo was all about moneymaking and that its most important feature was that it provided a means to make a living for outer atoll women. To her, craftwork was separated (or disembedded) from a wider set of social relations, which made it difficult for her to conceptualize it as anything other than commercial. Yet, as the example of the jaki shows, some items are more ambiguous than others.

From the contemporary vantage point, it is easy to be caught up in the increased commercialization coupled with material and aesthetic shifts that have happened to the craft over the past century. Even those who construe contemporary amiṃōņo as a cultural rather than economic endeavor deem today’s amiṃōņo as somehow less authentic than its 1890s counterpart. What I have showed here, though, is that much of the historical craft preserved in European museums is indeed commercial craft of their day. Even if craft and commerce (including pre-colonial internal trade) have always been interdependent, amiṃōņo is tied up with discourses that conceptually separate culture and economy.

The conceptual difficulties that arise are linked to concrete practices in which commercial craft is used in internally meaningful ways, that is, in ways commonly deemed cultural. Consequently, people use crafts in ways that encourages ongoing dialogues about how to define and understand amiṃōņo. These varying uses and the dialogues they incite are key parts of the production of value and, by extension, the production of culture. However, so long as cash is seen as the antithesis of culture, amiṃōņo will remain an ambiguous concept, not only for Marshall Islanders but for foreign observers as well.

Conclusion

Amiṃōņo is conceptually difficult because it taps into a larger issue of how to conceptualize culture. The key question is whether commercial activities can also be designated as culture or whether culture and commerce are incompatible. Despite searching for clear-cut definitions, it is clear that amiṃōņo owes its existence to both economic and cultural incentives. I have established that, without an economic incentive to weave, amiṃōņo would look nothing like it does today. The most extreme example comes from the development project that saw the creation of the Kōle bag. Developed exclusively to secure monetary income to a displaced Pikinni (Bikini) population, it was abandoned by its originators as soon as other means of income materialized (Lanwi Citation2004, 211). Yet, the design lives on in the hands of what are today mostly Arņo weavers and is widely recognized as a piece of material culture.

Indeed, even the newly developed amiṃōņo has played a part in local rituals to the degree that its presentation has had negative economic consequences, as explained from Utrōk above where craft-giving resulted in debts from store-credit. Even in less extreme examples, it is clear that craftwork has not been driven by economic maximization. For example, the Micronesian Reporter (Citation1963, 20) noted that, in 1962, the women from Maloeļap had sent two boxes of amiṃōņo to Mājro, one as a gift to friends, the other for sale, attesting to the some of the multiple needs craft can meet.

Although recognizing that amiṃōņo is made to please different audiences at once, Marshall Islanders, too, struggle with their definition of amiṃōņo because of a pervasive separation of culture and economy. On the one hand, there is the idea about authentic culture and how things made for the market fail to meet those standards, the same idea that made the shopkeeper presented at the beginning of this article claim that people do not use craft anymore. On the other hand, there is the idea about female creativity embodied in individual artifacts and how sporting those artifacts ‘promotes culture’. Indeed, people are inclined to refuse the category ‘culture’ when discussing amiṃōņo exchanged in a craft shop while simultaneously asserting that it is fitting when discussing its making and use.

What I have showed here, though, is that this ambiguity occurs precisely because of the mutual formation, inseparability perhaps, of something we can distinguish analytically as culture and something we can distinguish analytically as economy. At its most basic, this is visible in the ways in which Marshall Islanders explicitly define the two categories in opposition to each other, so that what is perceived to be cultural cannot be bought at the market while what is sold at the market cannot be perceived to gain status as cultural. However, what is more important for my argument, is that this ideal distinction breaks down in lived life. Indeed, craft needs the market in order to flourish, a market that, in turn, needs a steady supply of craft and other so-called cultural goods to be operative. These interrelations are sources for conceptual ambiguity, but also sources to sustain culturally meaningful livelihoods.

My aim here has not been to sort out this ambiguity, or to explain it, but to show its social effects in terms of resisting capitalist relations. While illustrating how given objects move between different statuses and valuations as they move in space and time have been important to explain the ambiguous character of amiṃōņo, the shifting valuations is not my main point. Rather, the point is that this ambiguity is a vital part of cultural production in the Marshall Islands because it allows a continuous negotiation and reformulation of what Marshallese culture is and should be in the face of potentially disrupting social circumstances. The need to conceptualize amiṃōņo as culture rather than commerce is therefore not a refusal of ‘the commodity’, but of the total influence of commodity fetishism. Therefore, the separation of culture and economy is important to maintain the sense of cultural autonomy that frames economic activities as embedded in social relations.

Acknowledgements

I thank Keir Martin, Sylvia Yanagisako, Theodoros Rakopoulos, and Godwin Kornes for valuable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback. Finally, I am grateful to all weavers and shopkeepers that made my research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ola Gunhildrud Berta

Ola Gunhildrud Berta is an associate professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway. He holds a PhD in social anthropology. He has done ethnographic fieldwork with Marshall Islanders living in the Marshall Islands and Honolulu.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, edited by Arjun Appadurai, 3–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berman, Elise. 2020. “Avoiding Sharing: How People Help Each Other Get out of Giving.” Current Anthropology 61 (2): 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1086/708068

- Berta, Ola Gunhildrud. 2022. ‘Separating Culture and Capital: Economies of Culture and the Pursuit of Self-Reliance in the Marshall Islands’. Ph.D. dissertation, Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo.

- Cant, Alanna. 2019. The Value of Aesthetics: Oaxacan Woodcarvers in Global Economies of Culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Carucci, Laurence Marshall. 1997. Nuclear Nativity: Rituals of Renewal and Empowerment in the Marshall Islands. Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Chibnik, Michael, Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, Molly Lee, B. Lynne Milgram, Victoria Rovine, and Jim Weil. 2004. “Artists and Aesthetics: Case Studies of Creativity in the Ethnic Arts Market.” Anthropology of Work Review 25 (1-2): 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1525/awr.2004.25.1-2.3.

- Cohen, Erik. 1988. “Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 15 (3): 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X.

- Cooper, Melinda, and Liz McFall. 2017. “Ten Years After: It’s the Economy and Culture, Stupid!.” Journal of Cultural Economy 10 (1): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2016.1267026.

- DeBlock, Hugo. 2018. Artifak: Cultural Revival, Tourism, and the Recrafting of History in Vanuatu. New York: Berghahn Books.

- deBrum, Ione Heine. 2004. “Mokwaņ Ak Jāānkun, Preserved Pandanus Paste.” In Life in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, edited by Anono Lieom Loeak, Veronica C. Kiluwe, and Linda Crowl, 41–50. Majuro: University of the South Pacific.

- Erdland, August. 1914. Die Marshall-Insulaner: Leben Und Sitte, Sinn Und Religion Eines Sudsee-Volkes. Münster: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- Errington, Shelly. 1998. The Death of Authentic Primitive Art and Other Tales of Progress. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Graeber, David. 2001. Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gregory, Chris A. 1997. Savage Money: The Anthropology and Politics of Commodity Exchange. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers.

- ‘Handicraft from Maloelap’. 1963. Micronesian Reporter XI (1): 20.

- Hess, Jim, Karen L. Nero, and Michael L. Burton. 2001. “Creating Options: Forming a Marshallese Community in Orange County, California.” The Contemporary Pacific 13 (1): 89–121. https://doi.org/10.1353/cp.2001.0012

- Kotzebue, Otto von. 1821. A Voyage of Discovery Into the South Sea and Beering’s Straits, for the Purpose of Exploring a North-East Passage: Undertaken in the Years 1815-1818. Vol. II. London: Longman and Brown.

- Krämer, Augustin, and Hans Nevermann. 1938. Ralik-Ratak (Marshall-Inseln) [Ralik-Ratak: Marshall Islands]. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Hamilton Library Hawaiian and Pacific Collection.

- Lanwi, Mary Heine. 2004. “Mission School to National Mission: Creating the Handicraft Industry.” In Life in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, edited by Anono Lieom Loeak, Veronica C. Kiluwe, and Linda Crowl, 101–116. Majuro: University of the South Pacific.

- Lévesque, Rodrigue. ed. 1992a. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vol. 1 — European Discovery 1521–1560. Québec: Lévesque Publications.

- Lévesque, Rodrigue. ed. 1992b. History of Micronesia: A Collection of Source Documents. Vol. 2 — Prelude to Conquest 1561–1595. Québec: Lévesque Publications.

- Lukács, Georg. 1967. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. London: Merlin Press.

- Mason, Leonard. 1947. The Economic Organization of the Marshall Islanders. Honolulu: U.S. Commercial Company.

- Mulford, Judy. 2006. Handicrafts of the Marshall Islands. Majuro: Ministry of Resources and Development.

- Mückler, Hermann. 2016. Die Marshall-Inseln Und Nauru in Deutscher Kolonialzeit: Südsee-Insulaner, Händler Und Kolonialbeamte in Alten Fotografien. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

- Myers, Fred R. 2001. “Introduction: The Empire of Things.” In The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture, edited by Fred R. Myers, 3–64. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

- Polanyi, Karl. 2001. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Richard, Dorothy Elisabeth. 1957. United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. Vol. 1: The Wartime Military Government Period, 1942-1945. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations.

- Richardson, Lizzie. 2019. “Culturalisation and Devices: What Is Culture in Cultural Economy?” Journal of Cultural Economy 12 (3): 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1542608.

- Rudiak-Gould, Peter. 2013. Climate Change and Tradition in a Small Island State: The Rising Tide. New York: Routledge.

- Spoehr, Alexander. 1949. Majuro: A Village in the Marshall Islands. Chicago: Natural History Museum.

- Taafaki, Irene, and Maria Kabua Fowler. 2019. Clothing Mats of the Marshall Islands: The History, the Culture, and the Weavers. Majuro: Self published.

- Theodossopoulos, Dimitrios. 2013. “Introduction: Laying Claim to Authenticity: Five Anthropological Dilemmas.” Anthropological Quarterly 86 (2): 337–360. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2013.0032

- Thomas, Nicholas. 1991. Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific. London: Harvard University Press.

- Thomas, Nicholas. 2015. “A Critique of the Natural Artefact: Anthropology, Art & Museology.” Art History Lecture Series 13: 1–50.

- Thompson, Edward Palmer. 1961. “The Long Revolution (Part I).” New Left Review 1/9: 24–33.

- Udui, Elizabeth. 1964. The Handicraft Industry in the Trust Territory. 1. Occasional Papers and Reports. Saipan, Mariana Islands.

- Vitarelli, Margo. 1986. Handicrafts Industry Development and Renewable Resource Management for U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands. Haiku: Office of Technology Assessment, Congress of the United States.

- Wavell, Barbara. 2010. Arts and Crafts of Micronesia: Trading with Tradition. Honolulu: Bess Press.

- Wavell, Barbara. 2016. Woven Hand Fans of Micronesia. Winter Park, FL: Legacy Book Publishing.

- Wells, Marjorie D. 1982. Micronesian Handicraft Book of the Trust Territory of the Marshall Islands. New York, NY: Carlton Press, Inc.

- Yanaihara, Tadao. 1940. Pacific Islands under Japanese Mandate. London: Oxford University Press.