ABSTRACT

Steve Woolgar has argued that science and technology studies is a prime place for studying the relationship between children and consumption [2012 “Ontological Child Consumption.” In Situating Child Consumption: Rethinking Values and Notions of Children, Childhood and Consumption, edited by B. Sandin, A. Sparrman, and J. Sjöberg, 33–51. Lund: Nordic Academic Press]. Yet this project remains largely unfulfilled, mirroring the broader absence of children as a serious object of study in the discipline. This extends to the analysis of childhood eating. So-called ‘picky’ eating, which I refer to as ‘avoidant’ eating, involves varying degrees of food refusal, often experienced by carers as highly distressing. In response, many parents are turning to digital platforms for support. This paper analyses how parents’ encounters with avoidant eating become entangled with digital platforms, centring on a digital autoethnography of the author’s own information seeking practices via Google search. Not only does the paper respond to the neglect of parent–child relations as a site for research within STS, it also demonstrates that the so-called ‘new social studies of childhood’ could benefit from further analysing the way in which parent–child relations are entangled with relations between people and things, including digital platforms.

Introduction

The occasions of providing, and sometimes cooking, food for children is, for many families, a central part of the shorter – and longer-term rhythms of household life. The weekday routine – here in the UK perhaps including the rushed pre-school breakfast; the cramming of food into packed lunch boxes; the individualised or communal evening meal – interacts with the patterning of weekends, potentially with its opportunities for increased negotiations over food, for more food engaged with out of the house, on the move, for interactions with other feeding practices and traditions in visits to other households. And then there’s the annual feeding rhythms, marked out by the culturally diverse food-infused markers and traditions of a typical year – birthdays, gatherings of family and friends, cultural and religious celebrations, for example.

The willing, ideally enthusiastic, participation of children in these various feeding and eating occasions has, for many families, considerable symbolic importance. As Allison James, Penny Curtis, and Katie Ellis make clear, it is seen as a key sign ‘of a child’s engagement with what ‘the family’ is and does’ (Citation2009, 45). However, as many readers will know all too well, it is common for this ideal to confront the messy reality of family life, with children often not engaging with food as their parents and carers hope they will. Even children who generally eat diverse foods will on occasion reject food for various reasons, perhaps because it is unfamiliar, perhaps because it is experienced as unpleasant. For some children, these moments of rejection are far more common, with each and every feeding occasion being a moment at which a child might make clear their discomfort about eating, or outright refusal to eat, in the way parents hope or expect they will. In due course, these children will likely be assigned a label, whether by their carers or others: in many English-speaking contexts, they become the so-called ‘picky eaters,’ with their eating practices potentially taking on the status of a particular kind of personhood, especially in and around eating occasions. As I will explore further in due course, for many families, ‘picky’ eating practices are a major site of family conflict. This is not surprising – if enthusiastic participation in family eating occasions marks a positive engagement with culturally constructed understandings of the family, then children’s lack of participation can constitute ‘a metaphoric refusal to participate in family life’ (James, Curtis, and Ellis Citation2009, 46). Indeed, as John Coveney argues, it is around the meal table that the ethics of parenthood is routinely constructed and around which children are constructed ‘as subjects who have to be trained, disciplined and watched over’ (Coveney Citation2006, 126).

One of the paper’s aims is to explore how ‘picky’ eating is enacted, not just socially and culturally but also socio-technically, with a focus on the role of digital online resources, including search interfaces and support forums used by parents. In so doing, I am keen to bring to the study of such contexts an understanding of agency as co-constituted by humans and non-humans. The paper thus sits in dialogue with the long history of discussion into such issues, including within Science and Technology Studies (STS). On the one hand, the claim that agency is constituted relationally in and through diverse types of entity will hardly be surprising to readers of this journal. On the other, however, this has the potential to contribute to underexplored questions around the interactions between digital platforms, food, and feeding. This informs two of the paper’s further aims: first, very much like other papers in this special issue, it seeks to shed light on the question of how non-human things, including digital things, contribute to how food, feeding and eating is enacted and understood, in the context of a broader literature on such topics in which the non-human is largely underarticulated. And second, it aims to open up the question of how STS and related fields might consider the role children play in the co-constitution of agencies, in the context of a somewhat relatively absence of children in such discussions.

For both ethical and practical reasons, I focus on children primarily via an analysis of practices of parenting, even as these are of course shaped by dynamic interaction with the distributed agencies of children. A note on terminology is also required. Throughout the rest of this paper, I will use the term ‘avoidant’ rather than ‘picky’ (or other alternatives, for example, ‘fussy,’ or ‘faddy’) in my own discussions of such childhood eating practices, even while using ‘picky eating’ when referring to how such eating practices tend to be understood by many adults. The term ‘avoidant’ (alongside alternatives such as ‘restrictive’ eating) is often used within clinical practices, often drawing from psychological perspectives (Cooney Citation2018; Dovey Citation2019; Norris, Spettigue, and Katzman Citation2016). I follow Joanna Cormack in defining avoidant eating as ‘the consumption of a limited variety of familiar foods and the rejection of unfamiliar foods’ (Citation2021, 13). This is a definition which recognises that part of the very constitution of avoidant eating is the way it is understood by carers; for example, what constitutes a ‘limited’ variety of may vary hugely between one parent and another, as long recognised in clinical practice (e.g. Lumeng Citation2004). It also has the advantage of avoiding both the framing of avoidant eating behaviour as straightforwardly associated with ‘choice’ (i.e. the rational ‘picking’ of one food option over another) and the value-based connotations that have become associated with the term (i.e. the picky eater as lacking attributes of childhood identity as desired by the person or people assigning this label). It is also worth being clear that there is a wide spectrum of avoidant eating practices, which can in some cases extend to avoidant eating practices that are extreme enough to have potentially severe consequences, including significant health concerns and/or child distress around food. In such cases, children can become clinically diagnosed as having Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), even if in many contexts (including in the UK), understanding of, and diagnosis of, ARFID is low (see Cormack Citation2021, 31).

Also, even though childcare is clearly often performed by diverse individuals, with different relationships to the feeding of children, located in formal and informal networks of family, friends and professions, for the sake of simplicity I will generally refer to the responses and understandings of the ‘parents’ of avoidant eaters. In part this is because in the online resources I will proceed to discuss, the prevailing assumption is that it is parents and, particularly, mothers who are those reading and engaging with its content.Footnote1 In noting this, I acknowledge that, as a father, I cannot speak meaningfully to gendered experiences of how ‘motherhood’ is often implicitly or explicitly evoked in online discussions around avoidant eating. I also recognise that inevitably my focus on parents is in part a result of my own positionality.

In analysing how avoidant eating is socio-technically enacted, I will be drawing on a digital autoethnography of my experiences responding to one of my own children’s avoidant eating. This centres on the search terms I entered in an early phase of their avoidant childhood eating, as a way to introduce the ways in which digital platforms can co-construct knowledge around avoidant eating. I will also touch on my experience of online help groups for parents, as present in particular on Facebook, as well as engagement with books aimed at parents and carers. In my analysis, I also examine how particular features and functionalities of digital platforms can act as affordances, building on existing work in this area (Bucher and Helmond Citation2018; Madsen Citation2015), with affordances understood as relating not just to the technical features of specific platforms, but relational capacities constructed between platforms, users and contexts (Willems Citation2021). A final aim of the paper, therefore, is to make a methodological contribution, by highlighting the analytical opportunities that search archives can provide as autoethnographic resources.

The mediation of childhood eating

In order to provide some context to the subsequent analysis of how avoidant eating might be mediated by select digital platforms, it is worth pulling out some of the broader discussions around how childhood eating might be socially, culturally and, to a lesser extent, digitally mediated. As such, the focus is not on the broader literatures on avoidant eating in, for instance, psychology and as related to clinical practice.

As such, the paper also sits in critical dialogue with broad discussions on the sociological and historical construction of childhood. The literatures on these questions are too voluminous to give full justice to here, but particularly relevant are the ‘new social studies of childhood’ – a field which can trace its now not so new origins to the early 1990sFootnote2 (James and Prout Citation1990; Mayall Citation1994; Qvortrup Citation1994a; Citation1994b). At its heart, this work sees childhood as a social construction, shaped by the diverse circulation of images and other forms of representation. Such approaches would also reject any assumptions about the automatic primacy of biology in determining the outcomes of particular childhoods.

Particularly germane to the present paper are discussions of how children relate to the contexts in which they are located. Increasing efforts have been made to better understand the ways in which, rather than responding to their contexts passively, children have agency in how they contribute to and shape the worlds around them, with an emphasis on ‘children as participants in, as well as outcomes of, social relations’ (Alanen and Mayall Citation2001, xi). The assumption in such work, therefore, is that ‘child’ is a not a determining category, but a relational concept, used at once to separate non-adults from adults, to organise and structure children’s lives, and at the heart of diverse relationships, including in the family (Alanen Citation2001, 114). Moreover, while there are obvious imbalances in power relations between adults and children, neither adults nor children are wholly independent from one another – thereby complicating understandings of children as necessarily ‘dependent’ – with adults’ power over children ‘not absolute and … subject to resistance’ (Punch Citation2001).

At the same time, a range of social architectures are designed explicitly to direct children’s worlds, habits and practices along trajectories desired by adults. This includes the biopolitical management of childhood eating. John Coveney’s (Citation2006; Citation2008) work, including with colleagues (Middleton Citation2022), on the way in which the family meal becomes a site of disciplinary work, alluded to above, would be one prominent example. Within the wider academic discussions, a significant focus has been on how this plays out in relation to concerns around obesity – Jan Wright extends Foucault’s work on biopower to explore the specific ‘biopedagogies’ that circulate around healthy eating, including in the school-based and public health messaging around childhood eating (Burrows and Wright Citation2020; Wright and Halse Citation2014). An alternative potential site for the enactment of biopedagogy is the school meal: Truninger and Teixeira (Citation2015), in a study of schools in Portugal, explore how the school meal becomes seen as a core site for the management of childhood eating – for example in attempting to counter what are perceived to be children’s ‘unhealthy’ eating practices outside of school boundaries. They document how efforts to engage with childhood eating via logics of ‘care’ (see Abbots, Lavis, and Attala Citation2015; Mol Citation2008b) by various key actors can flounder in the face of dominant disciplinary apparatuses. However, they also open up children’s capacity for resistance in the face of biopedagogy: hiding leftovers, swapping foods, or refusing to eat certain foods or even meals in their entirety.

I have already noted how central the ways in which children eat within family contexts are to shaping family and parental imaginaries. The family meal is often central to that (indeed, children too can readily reproduce normative, ideal visions of the role of family meals (Persson Osowski and Mattsson Sydner Citation2019). It has been argued that in many societies, the family meal is a central in the socialisation of children, including a key space where various social positionings – gender, for example, or generation – play out and become stabilised, with instances of food refusal potentially being ‘cultural sites for socializing children into conflict’ (Ochs and Shohet Citation2006). And conflict around food during family meals can become a central site for struggles around agency – many will have had experience of parenting that uses different strategies to ensure that certain food types are eaten, sometimes in certain orders (an anticipated dessert becoming contingent on the consumption of vegetables, for example) – the delicate interplay of agency and resistance that can accompany such practices becoming a metaphorical ‘battle’ for some parents (Cook Citation2009; Paugh and Izquierdo Citation2009). Gender has long been central to the events of family feeding, with mothers often taking on the emotional and embodied labour of delivering meals that are most likely to be eaten by all, including children (DeVault Citation1991). This reflects the persistent gendered division of household labour, including food preparation (Cairns and Johnston Citation2015; Elliott and Bowen Citation2018), even as some scholars argue for the need to attend to the nuanced power relations and subjectivities performed around nurturing and care work (Meah Citation2014). With food, very much a hybrid entity, at the centre of such discussions, the absence of contributions that integrate an attention to materiality and the non-human into the analysis of childhood eating is striking. This is despite leading scholars in STS touching on both eating practices and childhood agency in their work. Annemarie Mol (Citation2008a), for example, observes that eating provides a prime site for studying where and how subjectivity is distributed. Steve Woolgar, meanwhile, argues that disciplines such as STS can offer a range of potentially helpful resources for studying the relationship between children and consumption (by which Woolgar is referring largely to economic forms of consumption), partly because of its ability to shed new light on essentialisms such as ‘children,’ or ‘decision,’ or, he notes, ‘healthy food’ (Citation2012, 37).

However, a few scholars have begun to conceptualise childhood in ways that look beyond the role of purely human relations. Michael Gallagher argues for considering the ‘different kinds of agency’ involved in these situations, arguing for styles of analysis that explore the relations between the ‘organic’ and the ‘inorganic,’ understood via Jane Bennet and Elizabeth Grosz not as determinate categories but ‘related tendencies’ (Gallagher Citation2019, 196).Footnote3 This is echoed by David Oswell (Citation2013; Citation2016), who sees STS-aligned analyses of childhood to be well placed to analyse ‘how children’s agency might be assembled and infrastructured within and across a range of devices, materialities, technologies, and other sentient bodies’ (Oswell Citation2016, 25). From such perspectives, what in some of the aforementioned discussions could be understood as ‘resistance’ might instead be framed as examples of ‘inventive agency’ (Gallagher Citation2019, 195). This complements work such as Alan Prout’s examination of how childhood is ‘formed as assemblages of related materials’ (Citation2005, 141) – potentially including, for example, digital technologies, biological tendencies, or medications – or Peter Kraft’s analysis of the ‘more-than-social’ qualities of children’s emotions (Kraftl Citation2013). This burgeoning interest in considering childhood as composed in relations not just between people but also people, unruly bodies and things leads Spyros Spyrou (Citation2019) to ask: does this mark the beginnings of an ‘ontological turn’ in studies of childhood?

This interest in ontological explorations of childhood reveals an important way in which STS is being brought to childhood studies. A focus on understanding such forms of ontological composition and specification marks a shift to examining how enactment occurs through a variety of practices and intermediaries, many of them utterly mundane (Woolgar and Lezaun Citation2013). This is an attention, as Sergio Sismondo puts it, to ‘how the many things with which we interact are made the ways that they are’ (Citation2015, 446).

Some STS scholars have also begun to explore the relations children have to food and eating. I want to highlight two. The first is in work by Florian Eßer, who draws on STS to examine the enactment of children’s overweight bodies in a residential care setting. In one section, for instance, he focuses on the role of the food diary which, despite being a non-human actor, ‘collaborates in a construction’ of one particular resident’s body within a biopedagogical framework designed to make this child ‘as a rationally acting subject, aware of how many calories she is consuming so that she can limit her food intake accordingly’ (Citation2017, 294). Eßer examines how food itself becomes a mediator, with the same resident using food to establish a range of subtle relationships with some of the humans and non-humans that compose her surroundings. The second is Emilia Zotevska and Anna Martín-Bylund’s (Citation2022) work, who also explore the mediating potential of foods, via a precise analysis of how the inventive agencies of different foodstuffs in household meals – including the textures, viscosity, elasticity and spillability of different foods engaged with by children – play a role in the enactment of family moralities. In so doing, they shed light on how the non-human qualities of food can contribute to the enactment of how food and eating should be done within family settings.

The paper also seeks to respond to the recognised paucity of research on how parents engage with issues around child feeding via social media and other digital platforms (Doub, Small, and Birch Citation2016; Fraser Citation2021). Exceptions include contributions by Supthanasup and colleagues (Supthanasup Citation2021; Supthanasup, Banwell, and Kelly Citation2022), who have analysed how Thai mothers use social media resources to support their feeding practices, including revealing how they offer vital forms of emotional support as well as peer validation. Another is work by Fraser (Citation2021), who explored the specific role of such resources for parents of avoidant eaters by analysing Reddit posts, highlighting parents’ concerns about nutrition and the deep levels of frustration they feel.

As I hope I have shown, childhood eating is a site with rich potential to open up questions for STS and related disciplines, as well as such work having much to contribute to the study of the place of children in our contemporary worlds. In the rest of this paper, I will look at the role of the digital as a quite specific non-human domain and its potential to become involved in the enactment of childhood eating. For it is increasingly self-evident that, for children as much as for adults, ‘[l]earning what and how to eat is now a thoroughly digital affair’ (Goodman Citation2018, xiii). In so doing, I am keen to engage with work that has sought to explore the ways in which the digital shapes the politics of eating in a variety of settings (Schneider Citation2018), including examining the way in which foods and food products increasingly become ‘digitally “informed materials”’ (Schneider Citation2018, 11; citing Barry Citation2005), co-constituted by the platforms through which they – and their eaters, buyers, preparers and providers – circulate.

Engaging a digital archive

As I have already mentioned, this paper – and much of its data – is closely connected to my own experiences with one of my children: my oldest daughter. I’ll refer to her as F. (this letter has no significance). As I will describe shortly, F. has been an avoidant eater from an early age and it will be this early stage of her avoidant eating, and my own responses to it that will be my predominant focus. I want to use my own experience as a parent as a jumping off point for an exploration of some of the ways in which avoidant eating can encounter digital platforms.

I will begin with a diverse set of resources that I have encountered over the years in my search for resources: the online support forum. The size of some of these groups gives an indication of their potential influence. The two most popular forums by far – both public pages – are ‘Kids Eat in Colour,’ with 442,000Footnote4 followers, and ‘My Fussy Eater’ with 364,000 followers. Both address avoidant eating, but do so somewhat indirectly. Much of the content on both pages errs towards more general feeding advice, including for example around baby led weaning, health foods, and recipes. Both sites do, though, promote particular resources for parents of avoidant eaters specifically. In the case of My Fussy Eater this is an eponymously named cookbook, while Kids Eat in Colour promotes an online course to parents struggling with avoidant eating. The course – ‘BetterBites’ – is run in part via a private Facebook group (with 9000 members).

Beyond such sites, are a range of forums that address avoidant eating more directly. The most popular is ‘Parenting Picky Eaters,’ a private group with 115,000 members. It was set up by a group of practitioners working, in different ways, with avoidant eaters (including Jo Cormack, cited above; I will return to Cormack later). Some others are similarly connected to the work of particular practitioners. For example, there is Real Help for Picky Eaters,’ a private group with 18,000 members, run by Alisha Grogan, a US-based Paediatric Occupational Therapist, as well as ‘Extreme Picky Eating Help,’ a public group with 11,000 followers run by Katja Rowell & Jenny McGloughlin (again, the former is cited above; again, I will return to them later, for reasons that will become clear). In each case, in different ways, the groups offer peer support mixed with specialist guidance. There are also groups aimed at parents of children with more severe instances of avoidant eating, particularly ARFID or SED (Selective Eating Disorder) as it has at times been termed. This includes for example ‘Mealtime Hostage’ (private; 18,000 members), ‘ARFID: Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder’ (private; 20,000 members), ‘ARFID support for parents & carers in the UK/Ireland’ (private, 16,000 members).

I have been part of some of these forums over the years, in my efforts to support F.. Indeed, as I will return to, one in particular proved quite transformative for me. The private groups are often the most active, yet also the most difficult to directly represent in research – by, for example, focusing on specific conversations. This is because they are private, safe spaces for parents. However, they have some similarities to other forums used by parents, being highly engaged communities of parental and, specifically, maternal feeling (Pedersen and Lupton Citation2018). They capture routine and highly affecting testimony of despair and the feeling of being defeated by the responses of avoidant eating children, with parents – and mothers in particular – routinely articulating the utter frustration that comes with the repeated refusals of their child or children to eat in the way they hope they will. Within such groups I have repeatedly witnessed micro controversies: the posting of advice or products that go against forum rules; the application of the term ‘picky’ to a child followed by a list of accepted foods that leads other forum participants to bristle. But weighing against this are the routine articulation of moments of real triumph – a new foodstuff eaten or engaged with, for example, drawing appreciation and support from many, while potentially for others standing as distressing comparisons to their own child’s practices and/or lack of progress. Despite their inevitable messiness, my overriding impression as a parent is that these are spaces that provide genuine support, that provide a space of communality – often across large geographic and cultural spans – in ways that make the parenting of avoidant eating a less isolating experience, with the emergence of platform-mediated shared affective sensibilities (see: Deville Citation2016). That said, I will confess that I have over the years muted such groups for some periods, finding the sheer volume of hurt they bear witness to personally difficult, bringing to the surface my own feelings of emotional distress, inadequacy and self-judgement that are utterly commonplace for parents of avoidant eaters (Harris Citation2018, p. e.g.; Cormack Citation2021, 152–172; Cunliffe, Coulthard, and Williamson Citation2022).

In the remainder of this paper, I want to focus on a different form of parental engagement with avoidant eating. Specifically, drawing on my own experiences as a case study, I want to focus on the activities of searching that can come to surround a parent’s evolving engagement with the resources, practices, and forms of expertise around avoidant eating.

I will focus in particular on a period around 2016, at which point F. was a toddler, although I will also explore a period – from late 2018 to early 2020 – during which we shifted to an approach to childhood feeding that we now use. I will also supplement this historical data by material gathered in 2023. In the period from 2016 to 2020, analysing what we were experiencing through a scholarly lens could not have been further from my mind. I was not, therefore, collecting data, in any formal way. However, data was being collected. Despite having in the past written about digital surveillance (Deville Citation2019; Deville and van der Velden Citation2016), and regularly teaching around the topic, there is much more that I could do to stop my own personal data being collected by third parties. The data that I will be drawing on in this section is an archive of my own search times stored by Google, whose search engine I was using at the time. Specifically, using Google’s ‘Takeout’ function, I downloaded my entire search and browsing history, which extended back to well before the birth of my daughter and then, using a combination of searching and browsing, explored this data. The resulting html file for the years spanning the period from her birth to early 2020 was around 70 MB in size – so around 70 million characters.

This is an approach inspired by the growing interest in so-called ‘digital methods,’ in which there is an effort to foreground, as Noortje Marres puts it, ‘the computational dimension of social enquiry as well as social life’ (Citation2017, 39). In the spirit of digital methods, I aim in part to ‘test the methodological capacities of digital devices’ (Citation2017, 107). I do not rely on digital data alone, however. Rather I combine my own personal search archive with a description of the contexts and logics informing the particular terms I entered into Google’s search platform. In this sense, my approach involves at least some digital autoethnography. Ahmet Atay argues that digital autoethnographies are at least in part a response to the way in which ‘new media technologies simultaneously disembody and reembody our experiences’ (Atay Citation2020). Similar dynamics are noted by Christine Hine (Citation2015, 83), who argues that digital autoethnographies that emphasise ‘the embodied and emotional experience of engagement with diverse media’ can help add vital context to disembodied data logs – my personal Google archive would be an example. As she also notes, neither logs nor autoethnographic approaches offer perfect representations of events, however ‘[e]ach reveals a different facet of the phenomenon’ (Citation2015, 84).

This combination of autoethnographic reflection with the stark record of a data log is inevitably somewhat ‘messy’ (Law Citation2004). I fully recognise the challenges and controversies that have surrounded autoethnography, including accusations of self-indulgence and lack of rigour (Forber-Pratt Citation2015; Sparkes Citation2002). However, it is, I would suggest, a method which is likely to become ever more required in the context of the ever-deepening quantification of our daily lives (Lupton Citation2016). In response, recent years have seen an increasing range of STS-inflected research embracing autoethnographic approaches, for example using personal experiences of intersections between disability and medical devices to ask questions about questions ‘about data, infrastructure, and the multiple human experiences of time’ (Forlano Citation2017), or using autoethnography as one part of a ‘methodological assemblage’ to explore experiences of disengagement from digital technologies (Senabre Hidalgo and Greshake Tzovaras Citation2023).

The potential of autoethnography is to provide access to dimensions of experience that otherwise will remain opaque. In the case of the data used in this paper, it is as far as I am aware, unique in the analysis of the interaction between avoidant eaters and their parents (perhaps in other contexts too – I wasn’t able to find similar work on other subjects). Indeed, I cannot see how such data could be accessed from other participants in any systematic way, given the ethical and practical barriers standing in the way of a researcher being granted access to – then exporting and publishing data collected via – a participant’s own account with, say, Google. However, it is important to recognise the ethical questions that arise given I implicate F. herself in the research. This was discussed during the process of ethical review at Lancaster and seems pertinent given the paper itself has an interest in questions of childhood agency. The committee approved an approach in which F. was given the opportunity to consent after having the nature of the research and what I planned to do explained to her, in a language appropriate to her age, and with no attempt to influence her decision. This approach was judged appropriate given I and my partner judged F. to have sufficient competencies to consent (sometimes referred to as being ‘Gillick competent’), despite being a child under the age of 16.Footnote5 I proceeded accordingly and carefully and confirm that F. has consented to being a participant in this research.

Platforming pickiness

I want to begin by focusing on a specific time period: August 2016. This was a point which the archive shows my attempts to find answers to questions I had regarding my daughter’s eating practices peaking. My partner and I had, however, been grappling with the ways in which my daughter would eat for at least a year beforehand, a period coinciding with F. attending a local nursery. As the months passed, we would get used to receiving reports from nursery workers that F. had eaten very little during the day, to the extent that we got into the routine of usually feeding her in the nursery car park before dropping her off in the morning and then immediately upon collecting her in the afternoon. At home, the pattern was similar. At age 2, here is a list of the main foods that F. would eat: pasta (with butter), rice (sometimes), sliced white bread, two types of cheese, boiled broccoli, boiled carrots, boiled sweetcorn, Cheerios (a breakfast cereal), boiled egg (egg white only), oat bars (one brand only), fruit smoothie pouches (a few only), apples, pears (sometimes), kiwi slices (sometimes), some sweets.Footnote6

I am acutely aware that there may be parents of avoidant eaters (including with diagnosed conditions such as ARFID) reading this whose own list of accepted foods may be much shorter (or even near non-existent – for some children, the near total absence of accepted foods means they have to be fed via a nasogastric tube). I have already mentioned how the labelling of a child as ‘picky’ is highly contextual and will relate perhaps as much to a parent’s expectations of what should be eaten by a child as what is actually being eaten. However, for my partner and me, this list represented a considerable challenge. As is common with avoidant eaters, many of the foods are either plain or sweet, with an almost total absence of any ‘complex’ foods, by which I mean foods containing visible mixtures of ingredients – for example, a soup, a sauce that includes vegetables, an oven bake. With a few exceptions, this meant that almost all the main meals served at F.’s nursery were, at the age of 2, routinely rejected.

This is the context in which my partner and I started looking more intensively for support, although not, initially, digitally. Before I started searching online, we had had at least three visits to a doctor (a GP – General Practitioner – as they are referred to in the UK). In each case, we found the experience almost wholly negative. Not only were we one on occasion reprimanded for feeding F. a branded fruit smoothie due to its sugar content (we brought F. with us, and she happened to have one in her hand; this particular kind has a plastic spout attached which the child sucks), we were also told that part of the issue was us giving in to F. too readily and that she would eat when she was hungry. Neither claim matched our experience with F. It was this encounter above all else that prompted me to search online for support (and points to the fact that, for many, the lack of expertise within the medical profession around avoidant eating will likely be a major driver of online information seeking by parents). In the early evening on the 16th August 2016, over a roughly half an hour period, I entered the following search queries:

children's nutrition specialist [city name]

children's nutrition specialist [city name] toddler

paediatric dietitian [city name]

[2 specialist’s names] + other terms [e.g. dietician, name of city]

“paediatric dietitian” [city name]

how much protein in an egg

toddler protein per day

how much protein cup of milk

how much protein in 100 ml milk

how much protein per day for 2 year old

toddler won't try new food

In terms of the form of expertise I am looking for, with the correct role title apparently confirmed by my search, it is institutional legitimation that I increasingly seek: my search records show me trying to search deeper in Google’s Search’s database for evidence that the expertise proclaimed by the specialists I had found online was not just codified (e.g. via qualifications) but was also institutionally legitimated, particularly by the NHS (the UK's National Health Service). Looking not only at my search terms but also my search history, I can see that I visited the webpages of individuals offering their services, a register compiled by ‘freelancedieticians.org,’ guidance from the NHS about how to ‘find a registered dietitian or nutritionist,’ a discussion on the vastly popular support/discussion forum MumsNet, in which the original poster asks the community to recommend a nutritionist, not to support the feeding of 2 years old, but to speak to teenagers at a charity event, after which other users post a series of names. I visit a similar range of pages a few days later (24th August) in which, after a range of searches about toddler weight (including calculating a child’s Body Mass Index (BMI), both on NHS pages and others), I search for ‘paediatric dietitian nhs training’ and ‘paediatric dietitian [city name] hospital.’ Throughout, a plenitude of relevant results – incorporating both institutionally authorised content and more messy expertise – convinced me that my search practices were on the right lines. The question for me was simply: based on the terms I had specified – registered, dietician, paediatric, NHS – who was the person who could best support us with F..

But searching will never only involve narrowing down. At the end of a sequence of five nutrition-focused searches, as shown above, we see the focus turn from nutrition to childhood neophobia – ‘toddler won't try new food.’ This marks a shift in emphasis from what is being eaten to how food is, or isn’t, being eaten. Some years later, a developing understanding of avoidant eating would lead me to focus far more on the latter, and towards the more responsive approach we now adopt. For now, I just want to note that searching always holds open the possibility, the promise, the imaginary, of ‘invention’ – of finally uncovering a novel, perhaps even revelatory answer to the challenge the searcher brings to the search platform.

In my case, the imaginary of platform mediated invention can be seen as existing in dialogue with forms of invention prompted by F. herself. Given the timing of these searches it is likely they were prompted by difficult experiences we had had feeding F. her evening meal. Irrespective, they – and our visit to the GP – evidence the way in which F. was exercising forms of ‘inventive agency,’ in Gallagher’s terms, in her relations with us, as parents (and also with other institutions – nursery, most prominently, although evidence of this would only come to us third hand, through the reports from nursery staff at the end of the day). Gallagher writes that instances of inventive agency by children are ‘unexpected eruptions that disturb the status quo, usually in situations where there is something at stake or an element of risk’ (Gallagher Citation2019, 195). Specifically, in our case, F.’s inventive agency centred on the persistence of her avoidant eating, with little to no perceptible change in how and what she would eat, in a context where my partner and I felt that her development/growth was at stake, with real risks for her future.

In this particular phase of our parenting, the end result of the entanglements between searching and the interactions between parents and child was a consultation with a particular paediatric dietician I found, who both worked in local hospitals as well as having her own business offering services to parents. In the lead up to our first meeting, my focus on nutrition intensified, with searches on the 27th August including for example ‘b1 vitamin 2 year old per day,’ ‘toddler omega 3 per day’ and ‘kiwi vitamins.’

If my framing of avoidant eating around questions of nutrition had been at least partially authorised by the results provided to me by Google, then meeting the paediatric dietician did so further. We visited her in September of that year and would go on to her see irregularly over a four-month period. In our meetings, she focused heavily on the details of what F. was eating, as might be expected given her profession. However, she did also introduce a new way of understanding F.’s eating: as linked to ‘behaviour.’ In the same letter, she wrote for example how she.

advised [F.’s] dad to continue our current plan of using behavioural feeding strategies to help encourage [F.] to try new foods, becoming more comfortable around these. They could choose a new food of the week and see if [F.] will become more comfortable around this food such as watch it, touch it, smell it, lick it, put it in her mouth, eat it. This should all be done at [F.’s] pace and stickers can be used for rewards.

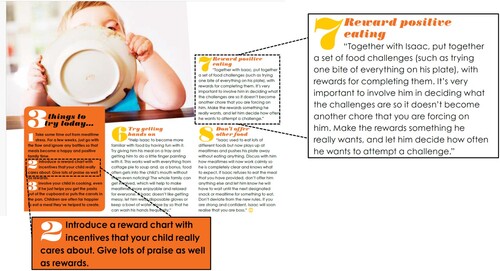

My partner and I stopped seeing the paediatric dietician at the end of 2016. This was less as a result of internet searching and more because we didn’t feel comfortable with approach being advocated, especially the heavy emphasis she placed on supplements and on so closely tracking F.’s weight and height. However, almost two years later, on the 2nd November 2018, my search records do find me still searching using the very framework the paediatric dietician had introduced: ‘fussy eater reward chart,’ I enter first, then ‘fussy eater reward chart dietician.’ I distinctly recall attempting to find a reward chart used in clinical/professional settings, in the face of dubious commercial alternatives, which likely explains the additional search term at the end of the second query. One of the pages I looked at, according to my records, was a post on Made For Mums, titled ‘Using a star chart with your fussy eater,’ which advised that ‘Once your child is around three years old, a reward chart can be a good way to encourage the behaviour that you want’ (Quick Citationn.d.). Another, on The London Nutritionist titled ‘Fight the Fussy Eating’ (The London Nutritionist Citation2012), used similar language ().Footnote8 As this shows, I continued to pursue using Google to provide incentive-based reward resources as a response to my daughter’s avoidant eating.

Figure 1. Details from ‘Fight the Fussy Eating’ (The London Nutritionist Citation2012).

This is not, however, the approach we settled one. Instead, eventually I discovered what is sometimes referred to as a ‘responsive’ (Black and Aboud Citation2011; Cormack, Rowell, and Postăvaru Citation2020) approach to child feeding. This approach is widely recommended within clinical practice (Engle and Pelto Citation2011) and is an approach rooted in the principles of a ‘Division of Responsibility’ (Satter Citation1986) between parents and children. In this approach the parent’s role is to determine when, where and what food is served, and the child is given agency over what they eat from the food provided, even if little or nothing is eaten at all (although the recommendation is usually to include at least one ‘safe’ food in the mix, to reduce anxiety about non safe options).

What, then, does my own digital archive show about how I came to this approach? The key phase in fact occurred shortly after my searching for reward charts in 2018. Suddenly, my practice shifts from looking for online resources, to looking for books.Footnote9 On the 9th of December I search for ‘fussy eating book child.’ My browsing history shows me being lead me to the Amazon page for a book titled The Gentle Eating Book (Ockwell-Smith Citation2018). While I did not settle on this specific title, nine days later I did buy the book that would eventually change how we approached engaging with my daughter’s eating: Helping Your Child With Extreme Picky Eating, by Rowell, McGlothlin, and Morris (Citation2015). As I described earlier, Rowell and McGlothlin also set up a Facebook forum with a similar title.

The record does not show how, precisely, I came to this text. Perhaps I searched further on a different device or browser, not logged into Google. But one possibility is that I was led to the title via an Amazon recommender algorithm (see Seaver Citation2019): even now, the title appears as one of the books that ‘Customers who viewed this item also viewed’ (). There is therefore at least the possibility of my path to a different approach to childhood feeding resulting from an intersection with a further proprietary algorithm.

It would take a further year before we embraced some of the approaches covered in Rowell and McGlothlin’s book. In many ways, as alluded to in the title, it is a text aimed at parents of children whose avoidant eating is far more challenging than F.’s was, which made me hesitate about its relevance. In fact, my digital archive shows that this hesitation lasted over a year, until January 2019. The timescales involved give some sense of how powerful the agency of avoidant eating children can be – it is often not, as parents are frequently told, ‘a phase,’ but a persistent mode of being, a form of inventive agency that rarely simply resolves itself, continually promoting parents for response in one form or another.

The key date is January 6th. Just after midnight, I search for ‘“Jenny Mcglothlin [sic]”’ and ‘helping extreme picky eating,’ perhaps after having browsed the book in the evening. And then a new term, allied to McGlothlin’s approach: ‘emotionally aware feeding,’ which led me to the website of the UK-based feeding specialist and academic Jo Cormack.

Cormack’s site in many ways represents, for me, the symbolic culmination of a searching journey that had started almost three years earlier. By 1 pm that day, I had paid just under £100 for access to support service that was then run by Cormack and colleagues: Your Feeding Team.Footnote10 The resources provided by Cormack and colleagues – particularly the documents and videos they have created – changed the way I thought about how I would engage with F. in and around mealtimes. This is reflected in my search terms – while a concern with nutrition remains (2019 would continue to see searches around the nutritional properties of certain foods – nuts, berries, cereals, for example), added to this are now searches connected to feeding practice: ‘division of responsibility,’ ‘food chaining,’ ‘“learning bowl” picky eating,’ for example. Each of these three terms are associated with the approaches advocated for by Cormack and colleagues.

The politics of platforms therefore of course still remains, inflecting relations and plays of agency around the meal table. But they also extend into digital space. One benefit that subscribers to this support service received in exchange is access to a private Facebook group – one tiny by comparison to those described earlier in the paper (the group currently has just over 100 members), including by comparison to the much larger ‘Parenting Picky Eaters,’ which Cormack and colleagues also set up. One distinction is that the Your Feeding Team Facebook group is a far calmer space, with moderators responding quickly to comments as they come in, including offering direct advice based on their own professional practice. This is clearly a paid for privilege. In addition, there is an irony here: as while it was a non-digital item – a book written for parents of avoidant eaters – that ultimately pointed me towards a different way of engaging with avoidant eating, it was its ability to act as an affordance for a new round of online searching that was perhaps its most enduring legacy.

Conclusion

A key aim of this paper was to example how avoidant is socially and culturally enacted, including by digital online resources. In this context, I hope that one contribution is to show the way in which not just foods but also feeding, in this case as related to the feeding of children, can become subject to processes of ‘ontological respecification’ (Schneider Citation2018), in the entanglements between digital platforms, childhood forms of inventive agency, and external expertise. In the context of the ‘ontological turn’ in childhood studies, mentioned earlier, and the broader exploration of interest in matters of ontology within STS, we can see how both the food served to children and the surrounding activities of feeding change. The support group on Facebook stands as an example of this: the promise, and sometimes the practice, of such spaces is to turn feeding from a solitary struggle into a collective issue, while simultaneously providing a space for not just the practicalities of feeding children to be held up as a collective problem, but also the emotional lows and, occasionally, highs that can characterise the experience of being the parent of an avoidant eater. Search platforms do something different. The searcher is caught in an apparent dialogue, with the platform as both interlocutor and affordance to the searcher’s respecification of foods and the inventive agency of children. In my case, this was performed by increasingly granular quantifications of nutritional value, with my search intensity becoming directly related to key stress points: the unsuccessful evening meal, the visit to the specialist. I also hope to have shown how the archives of search platforms at least have potential as resources for research, including autoethnographic research, into the politics of platforms. I have no illusions about this. There are ethical and practical obstacles that could stand in the way of scaling up such an approach.

A broader contribution is to show how digital platforms and their attendant materialities can become a part of child–parent assemblages and, indeed, child–parent-food assemblages, including the agencies of parents, children and digital platforms. One of the defining features of many parents’ engagement with a child’s avoidant eating will be the sense of utter powerlessness in the face of childhood agency, to the extent that this agency becomes inventive of new relations: not eating, or at least not eating in the way a parent wants, is very likely to become a prompt to parental response. In eating situations, this can readily range from coercion, to subterfuge (the grated vegetable, hidden in a sauce, for example), to entreaty, to reward, to anger, to despair. But it can also prompt a parent to look online for a solution to the challenge of avoidant eating, with support forums and/or search platforms potentially becoming bound up in the daily relations between parent and child in and around food and feeding.

The article shows some of the specific ‘patterning’ of relations around avoidant eating. Parental understandings of relevant expertise as related to food and feeding are pushed along specific trajectories, in my case from children’s nutrition specialist to paediatric dietician. What I still struggle to understand is how I never, in this phase at least, came across the responsive approach to feeding that we now use. I have found this approach transformative – less because of a radical effect on F. (she is still an avoidant eater, but less so) and more because it has provided a framework for engaging with her that I find far more productive and empathetic. It provides precisely the expertise I was grasping after in 2016, and yet at this point in time, I and Google search were unable to co-deliver the information that I now know was hidden from me somewhere in Google’s unimaginable vast databases. Perhaps in-between me adding to these databases and Google serving me its answers, we were co-creating a ‘trap’ similar to the recommender systems discussed by Nick Seaver (Citation2019). Perhaps Google search’s propensity to serve searchers with culturally dominant perspectives played into this, that in other contexts amplifies various forms of algorithmic inequality (Noble Citation2018). At the same time, I do not want to feed too much into the myth of the algorithm (Ziewitz Citation2016): perhaps, it was partly because Google search simply provided me with an answer. The revelatory effect of a new potential solution to an issue that is experienced as so distressing is, in its own right, a powerful affordance, with the potential to push aside critical reflection into the answers provided and the questions posed. This perhaps explains my search for – and using resources related to – behaviouralist approaches that, even at the time, I had concerns about, both as an academic and as a parent observing their seeming utter incompatibility with how my child engaged with her food.

Through these kinds of digital engagements, avoidant eating – and hence childhood more widely – becomes not simply socially and culturally constructed, but socio-technically enacted. If the ethics and roles of both parents and children are routinely being made around the meal table, to return to the work of John Coveney, then this paper shows how for many an additional unseen actor at the table are parent-initiated rhythms of search query and algorithmically mediated search response. As such, I hope the paper has responded to the broadscale neglect of parent–child relations as a site for research within and around STS, while also demonstrating that the new social studies of childhood and childhood studies more widely could benefit from further analysing the way in which parent–child relations are entangled with relations between people and things, including digital platforms. The socio-material relations that cluster around avoidant eating are further evidence of just how diverse the entities are that are involved in the co-construction of childhood agency. Not only does this further underscore the limitations of narrowly developmentalist understandings of childhood, it also highlights the importance of attending to the contribution of infrastructures – including digital infrastructures – to the enactment of childhood agency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Of course, such resources are likely consulted by a range of people, with diverse roles, from parents to carers to medical professionals. However, it is parents, and often mothers, who are particularly commonly evoked, whether by forum participants beginning their posts with addresses to other ‘mommas’, or by articles that reference ‘your child,’ as in the case in each of the first three results from a Google search using the terms ‘fussy eating child’ in the UK.

2 How ‘new’ these early 1990s claims actually were has been disputed (Ryan Citation2008).

3 With the organic possessing ‘a drive towards movement, activity, change, surprise’ (Bennett Citation2010, 78), while the inorganic performs ‘habitual actions with a measure of some guarantee of efficacy’ (Grosz Citation2010, 151).

4 All member/follower figures rounded to the nearest 1000. Numbers as of 23rd January 2024.

5 As I wrote in the application, F. ‘does, in the view of my partner and I, pass the test of Gillick competence. That is to say, she bright and able to engage well with discussions about risk and consequences of diverse actions including her own. She is capable of explaining the rationale and reasoning of her decision making’. See Driscoll (Citation2012) for a nuanced discussion of the applicability of tests of Gillick competency in social research settings. The research has been approved by the Lancaster University FASS-LUMS Research Ethics Committee, reference FASSLUMS-2023-3968.

6 This list is reconstructed partially from a list I sent a nutritionist in 2016, which I will discuss shortly, to which I have added a few foods I now realise I left off that list.

7 This is an approach directly challenged by a responsive approach to avoidant eating, in which the very aim is to reduce pressure to eat, in a context where pressure is seen to potentially come as much from encouragement as coercive efforts from parents.

8 I should be clear that both the dietician we visited and many of the more behaviouralist resources that can be readily found online do combine reward systems with advice on changing the dynamics of feeding and eating – such as encouraging play with food, involving children in shopping and meal preparation, and making mealtimes ‘fun’ by preparing food in inventive, playful ways. One feature distinguishing this from a more responsive approach to engaging with avoidant eaters is that the latter advises removing all pressure – both positive and negative – around childhood eating.

9 This does beg the question, especially given that I am an academic: why did you not do this before?! I can only assume that I had concluded that the information I would find online was likely to be similar to that I found in books on the topic. I recognise that this might seem embarrassingly naïve!

10 The service was made unavailable to new subscribers in late 2023, following a change of approach by its founders.

References

- Abbots, E.-J., A. Lavis, and L. Attala, eds. 2015. Careful Eating: Bodies, Food and Care. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Alanen, L. 2001. “Understanding Childhoods: A London Study.” In Conceptualizing Child-Adult Relations, edited by L. Alanen, and B. Mayall, 114–128. London: Routledge/Falmer.

- Alanen, L., and B. Mayall. 2001. “Preface.” In Conceptualizing Child-Adult Relations, edited by L. Alanen and B. Mayall, xi–xii. London & New York: Routledge/Falmer.

- Atay, A. 2020. “What is Cyber or Digital Autoethnography?” International Review of Qualitative Research 13 (3): 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940844720934373.

- Barry, A. 2005. “Pharmaceutical Matters: The Invention of Informed Materials.” Theory, Culture & Society 21 (1): 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276405048433.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Black, M. M., and F. E. Aboud. 2011. “Responsive Feeding Is Embedded in a Theoretical Framework of Responsive Parenting.” The Journal of Nutrition 141 (3): 490–494. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.129973.

- Bucher, T., and A. Helmond. 2018. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” In The Sage Handbook of Social Media, edited by J. Burgess, A. E. Marwick, and T. Poell, 233–253. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Burrows, L., and J. Wright. 2020. Biopedagogies and Family Life: A Social Class Perspective’, in Social Theory and Health Education. London: Routledge.

- Cairns, K., and J. Johnston. 2015. Food and Femininity. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Cook, D. T. 2009. “Negotiating Family, Negotiating Food: Children as Family Participants?” In Children, Food and Identity in Everyday Life, edited by A. James, A.-T. Kjørholt, and V. Tingstad, 112–129. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cooney, M., M. Lieberman, T. Guimond, and D. K. Katzman. 2018. “Clinical and Psychological Features of Children and Adolescents Diagnosed with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in a Pediatric Tertiary Care Eating Disorder Program: A Descriptive Study.” Journal of Eating Disorders 6 (1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0193-3.

- Cormack, J.L. 2021. “Wading through Sludge”: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Parental Experiences of Child Feeding in the Context of Avoidant Eating. University of Leicester, Bishop Grosseteste University. Accessed 5 March 2023. https://leicester.figshare.com/articles/thesis/_Wading_Through_Sludge_An_Interpretative_Phenomenological_Analysis_of_Parental_Experiences_of_Child_Feeding_in_the_Context_of_Avoidant_Eating/19193279.

- Cormack, J., K. Rowell, and G.-I. Postăvaru. 2020. “Self-Determination Theory as a Theoretical Framework for a Responsive Approach to Child Feeding.” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 52 (6): 646–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2020.02.005.

- Coveney, J. 2006. Food, Morals and Meaning. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Coveney, J. 2008. “The Government of the Table: Nutrition Expertise and the Social Organisation of Family Food Habits.” In A Sociology of Food & Nutrition: The Social Appetite, 3rd ed., edited by J. Germov, and L. Williams, 224–241. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Cunliffe, L., H. Coulthard, and I. R. Williamson. 2022. “The Lived Experience of Parenting a Child with Sensory Sensitivity and Picky Eating.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 18 (3): e13330. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13330.

- DeVault, M. 1991. Feeding the Family: The Social Organization of Caring as Gendered Work. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Deville, J. 2016. “Debtor Publics: Tracking the Participatory Politics of Consumer Credit.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19 (1): 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2015.1068169.

- Deville, J. 2019. “Digital Subprime: Tracking the Credit Trackers.” In The Sociology of Debt, edited by M. Featherstone, 145–173. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Deville, J., and L. van der Velden. 2016. “Seeing the Invisible Algorithm: The Practical Politics of Tracking the Credit Trackers.” In Algorithmic Life: Calculative Devices in the Age of Big Data, edited by L. Amoore, and V. Piotukh, 90–109. London: Routledge.

- Doub, A. E., M. Small, and L. L. Birch. 2016. “A Call for Research Exploring Social Media Influences on Mothers’ Child Feeding Practices and Childhood Obesity Risk.” Appetite 99: 298–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.003.

- Dovey, T. M., et al. 2019. “Eating Behaviour, Behavioural Problems and Sensory Profiles of Children with Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), Autistic Spectrum Disorders or Picky Eating: Same or Different?” European Psychiatry 61: 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.06.008.

- Driscoll, J. 2012. “Children’s Rights and Participation in Social Research: Balancing Young People’s Autonomy Rights and Their Protection.” Child and Family Law Quarterly 24 (4): 452–474.

- Elliott, S., and S. Bowen. 2018. “Defending Motherhood: Morality, Responsibility, and Double Binds in Feeding Children.” Journal of Marriage and Family 80 (2): 499–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12465.

- Engle, P. L., and G. H. Pelto. 2011. “Responsive Feeding: Implications for Policy and Program Implementation.” The Journal of Nutrition 141 (3): 508–511. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.130039.

- Eßer, F. 2017. “Enacting the Overweight Body in Residential Child Care: Eating and Agency Beyond the Nature–Culture Divide.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 24 (3): 286–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568216688245.

- Forber-Pratt, A. J. 2015. ““You’re Going to Do What?” Challenges of Autoethnography in the Academy.” Qualitative Inquiry 21 (9): 821–835. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415574908.

- Forlano, L. 2017. “Data Rituals in Intimate Infrastructures: Crip Time and the Disabled Cyborg Body as an Epistemic Site of Feminist Science.” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 3 (2): 1–28. https://doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v3i2.28843.

- Fraser, K., et al. 2021. “Fussy Eating in Toddlers: A Content Analysis of Parents’ Online Support Seeking.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 17 (3): e13171. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13171.

- Gallagher, M. 2019. “Rethinking Children’s Agency: Power, Assemblages, Freedom and Materiality.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (3): 188–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619860993.

- Gillespie, T. 2010. “The Politics of “Platforms”.” New Media & Society 12 (3): 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809342738.

- Gillespie, T. 2014. “The Relevance of Algorithms.” In Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society, edited by K. A. Foot, P. J. Boczkowski, and T. Gillespie, 167–194. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Goodman, M., et al. 2018. “Preface: The Politics of Eating Bits and Bytes.” In Digital Food Activism, edited by T. Schneider, xiii–xxvi. Abingdon: Routledge (Critical Food Studies).

- Grosz, E. 2010. “Feminism, Materialism, Freedom.” In New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, edited by D. H. Coole, and S. Frost, 139–158. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Harris, H. A., et al. 2018. “What’s the Fuss About? Parent Presentations of Fussy Eating to a Parenting Support Helpline.” Public Health Nutrition 21 (8): 1520–1528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017004049.

- Hine, C. 2015. Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- James, A., P. Curtis, and K. Ellis. 2009. “Negotiating Family, Negotiating Food: Children as Family Participants?” In Children, Food and Identity in Everyday Life, edited by A. James, A.-T. Kjørholt, and V. Tingstad, 35–51. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (Studies in childhood and youth).

- James, A., and A. Prout. 1990. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood. London: Falmer Press.

- Kraftl, P. 2013. “Beyond “Voice”, Beyond “Agency”, Beyond “Politics”? Hybrid Childhoods and Some Critical Reflections on Children’s Emotional Geographies.” Emotion, Space and Society 9: 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2013.01.004.

- Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. Oxon; New York: Routledge.

- The London Nutritionist. 2012. Fight the Fussy Eating. Accessed 14 August 2020. https://www.thelondonnutritionist.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Fussy-Eaters.pdf.

- Lumeng, J. 2004. “Picky Eating.” In Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: A Handbook for Primary Care, 2nd ed, edited by S. Parker, B. Zuckerman, and M. Augustyn,. 265–267. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

- Lupton, D. 2016. “The Diverse Domains of Quantified Selves: Self-Tracking Modes and Dataveillance.” Economy and Society 45 (1): 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2016.1143726.

- Madsen, A. K. 2015. “Between Technical Features and Analytic Capabilities: Charting a Relational Affordance Space for Digital Social Analytics.” Big Data & Society 2 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951714568727.

- Marres, N. 2017. Digital Sociology: The Reinvention of Social Research. Cambridge: Polity.

- Mayall, B. 1994. Children’s Childhoods: Observed and Experienced. London: Falmer Press.

- Meah, A. 2014. “Reconceptualizing Power and Gendered Subjectivities in Domestic Cooking Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (5): 671–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513501404.

- Middleton, G., et al. 2022. “The Family Meal Framework: A Grounded Theory Study Conceptualising the Work That Underpins the Family Meal.” Appetite 175: 106071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106071.

- Mol, A. 2008a. “I Eat an Apple. On Theorizing Subjectivities.” Subjectivity 22 (1): 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1057/sub.2008.2.

- Mol, A. 2008b. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. London: Routledge.

- Noble, S. U. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.

- Norris, M. L., W. J. Spettigue, and D. K. Katzman. 2016. “Update on Eating Disorders: Current Perspectives on Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in Children and Youth.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 12: 213–218. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S82538.

- Ochs, E., and M. Shohet. 2006. “The Cultural Structuring of Mealtime Socialization.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2006(111): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.154.

- Ockwell-Smith, S. 2018. The Gentle Eating Book: The Easier, Calmer Approach to Feeding Your Child and Solving Common Eating Problems. London: Piatkus.

- Oswell, D. 2013. The Agency of Children: From Family to Global Human Rights. New York: Cambridge University Press. Accessed 23 January 2024. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139033312.

- Oswell, D., et al. 2016. “Re-aligning Children’s Agency and re-Socialising Children in Childhood Studies.” In Reconceptualising Agency and Childhood: New Perspectives in Childhood Studies, edited by F. Esser, 19–33. London: Routledge.

- Paugh, A., and C. Izquierdo. 2009. “Why is This a Battle Every Night?: Negotiating Food and Eating in American Dinnertime Interaction.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 19 (2): 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1395.2009.01030.x.

- Pedersen, S., and D. Lupton. 2018. ““What are you Feeling Right now?” Communities of Maternal Feeling on Mumsnet.” Emotion, Space and Society 26: 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.05.001.

- Persson Osowski, C., and Y. Mattsson Sydner. 2019. “The Family Meal as an Ideal: Children’s Perceptions of Foodwork and Commensality in Everyday Life and Feasts.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 43 (2): 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12495.

- Prout, A. 2005. The Future of Childhood: Towards the Interdisciplinary Study of Children. London, New York: Routledge.

- Punch, S. 2001. “Negotiating Autonomy: Childhoods in Rural Bolivia.” In Conceptualizing Child-Adult Relations, edited by L. Alanen, and B. Mayall, 23–36. London, New York: Routledge/Falmer.

- Quick, L. n.d. Using a Star Chart With Your Fussy Eater, MadeForMums. Accessed 14 August 2020. https://www.madeformums.com/toddler-and-preschool/using-a-star-chart-with-your-fussy-eater/.

- Qvortrup, J., et al. 1994a. “Childhood Matters: An Introduction.” In Childhood Matters: Social Theory, Practice and Politics, edited by J. Qvortrup, 1–23. Aldershot: Avebury (Public policy and social welfare).

- Qvortrup, J. 1994b. Childhood Matters: Social Theory, Practice and Politics. Aldershot: Avebury.

- Rowell, K., J. McGlothlin, and S. E. Morris. 2015. Helping Your Child with Extreme Picky Eating: A Step-by-Step Guide for Overcoming Selective Eating, Food Aversion, and Feeding Disorders. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc. Accessed 22 March 2023. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy1605/2015458526-b.html

- Ryan, P. J. 2008. “How new is the “new” Social Study of Childhood? The Myth of a Paradigm Shift.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 38 (4): 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1162/jinh.2008.38.4.553.

- Satter, E. M. 1986. “The Feeding Relationship.” Journal of the American Dietetic Association 86 (3): 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(21)03940-7.

- Schneider, T., et al. 2018. “Introduction: Digital Food Activism – Food Transparency One Byte/Bite at a Time.” In Digital Food Activism, edited by T. Schneider, et al. 1–24. Abingdon: Routledge (Critical Food Studies).

- Seaver, N. 2019. “Captivating Algorithms: Recommender Systems as Traps.” Journal of Material Culture 24 (4): 421–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518820366.

- Senabre Hidalgo, E., and B. Greshake Tzovaras. 2023. ““One Button in My Pocket Instead of the Smartphone”: A Methodological Assemblage Connecting Self-Research and Autoethnography in a Digital Disengagement Study.” Methodological Innovations 16 (2): 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991231161093.

- Sismondo, S. 2015. “Ontological Turns, Turnoffs and Roundabouts.” Social Studies of Science 45 (3): 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715574681.

- Sparkes, A. C. 2002. “Autoethnography: Self-Indulgence or Something More?” In Ethnographically Speaking: Autoethnography, Literature, and Aesthetic, edited by A. P. Bochner, and C. Ellis, 209–232. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

- Spyrou, S. 2019. “An Ontological Turn for Childhood Studies?” Children & Society 33 (4): 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12292.

- Supthanasup, A., et al. 2021. “Child Feeding Practices and Concerns: Thematic Content Analysis of Thai Virtual Communities.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 17 (2): e13095. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13095.

- Supthanasup, A., C. Banwell, and M. Kelly. 2022. “Facebook Feeds and Child Feeding: A Qualitative Study of Thai Mothers in Online Child Feeding Support Groups.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (10): 5882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105882.

- Truninger, M., and J. Teixeira. 2015. “Children’s Engagements with Food: An Embodied Politics of Care Through School Meals.” In Careful Eating: Bodies, Food and Care, edited by in E.-J. Abbots, A. Lavis, and L. Attala, 195–212. Farnham: Ashgate (Critical food studies).

- Willems, W. 2021. “Beyond Platform-Centrism and Digital Universalism: The Relational Affordances of Mobile Social Media Publics.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (12): 1677–1693. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1718177.

- Woolgar, S. 2012. “Ontological Child Consumption.” In Situating Child Consumption: Rethinking Values and Notions of Children, Childhood and Consumption, edited by B. Sandin, A. Sparrman, and J. Sjöberg, 33–51. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Woolgar, S., and J. Lezaun. 2013. “The Wrong Bin Bag: A Turn to Ontology in Science and Technology Studies?” Social Studies of Science 43 (3): 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312713488820.

- Wright, J., and C. Halse. 2014. “The Healthy Child Citizen: Biopedagogies and Web-Based Health Promotion.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 35 (6): 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2013.800446.

- Ziewitz, M. 2016. “Governing Algorithms: Myth, Mess, and Methods.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 41 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915608948.

- Zotevska, E., and A. Martín-Bylund. 2022. “How to do Things with Food: The Rules and Roles of Mealtime “Things” in Everyday Family Dinners.” Children & Society 36 (5): 857–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12543.