ABSTRACT

By means of two case studies, this paper demonstrates how customary chiefs in Northeast Congo crafted their power position under colonial indirect rule. The first case discusses chiefs’ role in anioto or leopard-men killings to secure their authority over people, land and resources whilst circumventing colonial control. The second case concerns nebeli, a collective therapy characterised by the distribution of a medicine or charm used to protect, heal and harm in Northeast Congo and South Sudan. These case studies show that indirect rule designed customary chieftaincy too one-sidedly, based on patrilineal succession and land rights. It tried to cut chiefs off from spiritual and coercive power bases such as anioto and nebeli, which were part of local political culture. While colonial authorities framed institutions such as anioto and nebeli as subversive, and expected government-appointed chiefs to renounce them, they were clandestinely used by chiefs to retain their grip on local society whilst fulfilling their state-imposed duties. However, these institutions were not simply used to resist or by-pass colonial control, but also to support it. These historical cases help to gain insight in contemporary chiefs and militia leaders’ continued use of similar coercive, spiritual and remedial means to boast their power.

This paper deals with the discrepancy between on the one hand, the theoretical idea of customary authority under Belgian colonial indirect rule, instilled in the position of the ‘customary chief’, and on the other hand, customary-authority-in-practice.Footnote1 Administrators implementing indirect rule officially ascribed customary authority to one centralised institution embodied by an appointed chief, thereby disregarding other ‘powers that are customary’.Footnote2 Thus, the administration generated an incomplete, biased understanding of local political culture that lasts until today. I argue that while colonial authorities framed certain institutions as subversive, and expected government-appointed chiefs to renounce and fight them, chiefs continued to clandestinely use these institutions for their own agendas. How customary chiefs engaged with such institutions constitutes a potent domain of African agency, telling us how chiefs negotiated their position, straddling different power fields in the colonial state. Revisiting customary authority as multifaceted and negotiable is important to rectify colonial misunderstandings of local political cultures, and to understand their legacy until today, including land and succession conflicts. Improved knowledge of the past further helps prevent that development and peacebuilding agencies base their interventions on inherited misunderstandings of local political cultures which compromise their effects.Footnote3

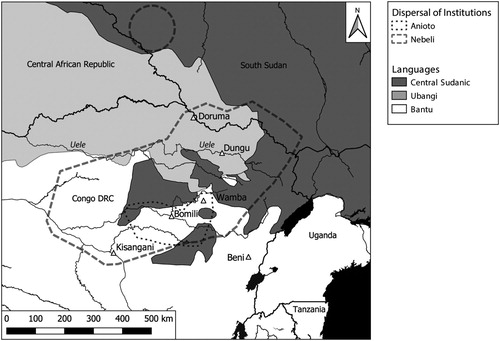

The first case discusses anioto or leopard-men gangs who operated on behalf of various Bali and Budu powerbrokers to secure control over people, land and resources whilst circumventing colonial control. Leopard-men gangs constituted ritually-empowered militias which played a role in political competition in segmentary rainforest societies. The second case discusses nebeli, a ‘collective therapy’ which spread over northeast Congo and South Sudan manifested itself in different forms. The term ‘collective therapy’, introduced by Janzen, denominates institutions characterised by the distribution of magico-medicinal substances or charms which are used to protect, heal and harm, and played a pivotal role in mobilisation for warfare or insurgencies. While collective therapies had an important counter-hegemonic potential, authorities in place commonly appropriated such institutions to secure their positions. Nebeli plays this versatile role until today, though its impact has probably shrunken.

Nebeli and anioto were not only instrumentalised to resist or by-pass the colonial government, but also in support of it, even if this government considered them a criminal offence. How customary chiefs used or fought these institutions gives insight in the conflicting relation between customary chieftaincy as a colonial concept and customary authority in practice. Even if institutions such as anioto and nebeli were framed as anti-colonial, they continued to be part of a complex domain of customary authority which was not limited to approved and state-coopted customary chiefs. Informal, outlawed and hidden institutions remained an integral part of the local political field, and presented a potent domain of African agency under colonial rule. To study this past helps to understand customary chieftaincy in later history, and how it continues to be caught in between formal structures of governance and their informal, covert or criminalised counterparts.

To start, the colonial dichotomisation between state-approved institutions and those labelled as inappropriate or anti-colonial, needs reconsideration. The absorption of local institutions into the colonial system for the purpose of indirect rule affected how the colonial government morally judged, categorised and documented them. Knowledge production regarding local institutions was driven by a desire to control them and maintain order, and was strongly shaped by Euro-Christian moral standards purging colonial society from practices regarded as uncivilised.Footnote4 Besides colonial administrators, missionaries seeking to convert the population had a strong hand in this, as the nebeli cases demonstrate. Colonial and missionary categorisations recast a part of customary powers as barbaric or hostile.Footnote5 This process tied in with suspicions of esoteric practices, which were difficult to monitor.Footnote6 From this perspective, institutions such as anioto and nebeli were easily labelled as anti-colonial, although this constitutes an inaccurate essentialisation. These phenomena were not always deliberately subversive, and they disturbed the colonial order in indirect ways.

By criminalising institutions, thereby pushing them underground, a blind spot was created in colonial historiography, which caused such institutions as well as customary chiefs’ participation in them to escape scholarly attention up to present. Moreover, in Belgian colonial archives, early twentieth-century documents on nebeli and anioto were long protected as judicial or confidential documents, so that they remained difficult to access and poorly known. Initially, I needed a special advice of the Belgian federal privacy commission to consult them, but recent policies permit better access.Footnote7 Through the study of early colonial documents, nebeli appears as a larger network than known so far, spread out over northeast Congo and South Sudan, and an important factor in regional politics. Despite colonial repression, such institutions often continued to exist, and remained an essential part of local political culture, sometimes until today.

In addition to moral categorisation and criminalisation, the concentration of customary authority into the chief under colonial rule, representing one institution that is equated with one ethnicity, constitutes another impediment to understanding local political cultures. Several studies scrutinise Mamdani’s dichotomous institutionalist model of the bifurcated state, which portrays the chief as a decentralised despot; they argue that this model reflects an ideational blueprint of the (post)colonial state rather than actual practices and resulting realities.Footnote8 Leonardi’s longue durée perspective on South Sudanese successions demonstrates that a chief’s legitimacy is negotiated. During violent episodes in (post)colonial history, the population preferred another kind of chief than the traditional, patrimonial chief whose position was based on inheritance and seniority – namely, a skilful mediator protecting them from successive colonial or rebel governments’ violence. The descendants of both kinds of chiefs remained competitors for chieftaincy up to present.Footnote9 Further testifying to the versatility and flexibility of actual chiefship, Komuniji and Büscher show in this issue how Ugandan Acholi chiefs in contemporary aid and post-aid contexts seek acknowledgement and assistance from local and foreign actors to maintain their position and privileges as brokers, and to boast their legitimacy.Footnote10 These cases show that reality does not correspond to clear-cut ideational blueprints of governance institutions, and chiefly successions and positions are nearly always negotiated with supporters and contenders, drawing on diverse resources.

In Congo, customary authority was and still is multi-faceted, and seldom the monopoly of chiefs.Footnote11 Advisory networks have been part of chiefly courts throughout time, and how these networks controlled or were controlled by chiefs depended on the circumstances. Preferences for chiefs also shifted and candidates negotiated their position with constituents, drawing on different power resources, including metaphysical, therapeutic or violent ones. These ongoing negotiations and related competition for power already were significant drivers of institutional innovation in the pre-colonial era. Cultural borrowing of institutions (or institutional elements) from neighbouring or subjected populations played an important role in this process.Footnote12 The resulting cultural diffusion and adaptations gave way to complex networks of enmeshed institutions, which conflicted with the colonial practice of singling out one institution for rule over one ethnic entity. Vansina stated that the continuation of the equatorial tradition in the pre-colonial era consisted precisely in innovations.Footnote13 Even if inhibited, this process did not stop with colonialism. Rather, the underlying cultural logic strongly determined the way African agents co-opted the colonial state, including its drive for progress. The imprint of existing institutions and cultural logics on innovation ties in with Thomas Spear’s idea that there are limits to the colonial invention of traditions and customary authority – in order for people to accept innovation, it needs to entail something familiar. As Spear noted, colonial rule, which encompassed customary chieftaincy, should not solely be looked upon as a working misunderstanding, but rather as a position resulting from what mutually attracted the colonial government and local populations.Footnote14 This observation urges us to consider the emic cultural logics and dynamics shaping leadership positions, wherein metaphysical and coercive practices vested in institutions such as nebeli and anioto played an intrinsic part. This article will demonstrate that such institutions did not simply evaporate when inhibited by colonial jurisdiction; chiefs really needed to count with them or control them to be successful. Therefore, customary authority must be looked upon as a composite entailing also other customary forces than the chief, which were at best condoned by the colonial authorities, but often outlawed.

The domain of institutional history calls for a dynamic structuration model in which power institutions as well as other social formations are enmeshed in a complex network and shaped in interaction. Most of the knowledge production on Congolese customary authorities inherited from the colonial era focuses on centralised political systems and hegemonic institutions, ignoring segmentary societies and institutions criminalised as subversive. Furthermore societies used to be studied as isolated ethnicities rather than interconnected or amalgamated, and constituted in interaction with the colonial state. A few exceptions aside, how societies responded to the colonial interventions has rarely been discussed.Footnote15 Offering a macro-perspective on the region’s precolonial political history, Vansina sketched a network of interconnected institutions, which rather gives a systemic and abstract outlook on institutional history, and needs to be fleshed out for a more concrete understanding.Footnote16 In this article, the focus is on micro-historical cases demonstrating how customary chiefs dealt with criminalised institutions. By comparing and contextualising diverse micro-historical cases, a detailed understanding is achieved of the colonial situation in practice, rendering it from something abstract to something more concrete.Footnote17 The comparison also enables a reconsideration of macro-historical dynamics. Overall, the institutions discussed are reconsidered as part of a dynamic political network in which micro- and macro-level politics, segmentary and centralised societies, hegemonic and counter-hegemonic institutions and the past and present are interconnected.

The sources this article draws upon include archival documents, which mostly reflect colonial administrators’ subjective observations of a lived reality, giving insight into tensions between individual actors and constituent groups from a colonial perspective.Footnote18 A few documents, such as court hearings, do at times provide unique local testimonies. Field research was conducted to investigate memories and contemporary remnants of the institutions studied. My methodology further included the contextual study of ethnographic objects, which contributed to insights in the practices of the institutions studied, such as the use of chiefly power objects, of nebeli’s protective-aggressive whistles and charms, and the arms and costumes of anioto.

The article is structured as follows. The next section explains the background of customary rule, focusing on biased understandings of anioto and nebeli under colonial indirect rule. Then the case studies are laid out demonstrating the ways in which customary chiefs resorted to forbidden institutions. The subsequent discussion section assesses how and why customary rulers turned to anioto and nebeli to maintain their positions, and draws a comparison with contemporary customary chiefs’ use of various power bases.

Moral categorisations of institutions under colonial rule

This background section explains how the colonial government instilled power in intermediary chiefs, and how this affected societies in Northeast Congo. It offers a more complex understanding of customary authority attenuating the idea of the despotic chief as the key figure of indirect rule. In addition, it outlines correlations between the implementation of indirect rule and the moral categorisation and criminalisation of institutions.

The implementation of indirect rule did not happen overnight, and preferences for intermediaries changed over time, giving rise to a multiplicity of powerbrokers. Under the Congo Free State (1885–1908), the most pragmatic way to administer Northeast Congo had been to adopt the trader-chiefs and infrastructure of the slave and ivory trade. After subjecting the trader-chiefs, they were annexed as middlemen to collect taxes and suppress rebellions.Footnote19 From the 1920s onwards, preferences shifted to earlier customary leaders, who were identified based on local rules of succession, and colonial ethnographic research established their legitimacy. In practice, the actual chiefs often pushed strawmen to occupy this position, and discretely controlled them in the background. In the end, however, many strawmen became more powerful and reluctant to act as subordinates to the real chiefs.Footnote20 If in theory, locally–rooted ‘customary’ leaders came to be favoured as chiefs from the 1920s onwards, in practice they competed with descendants from the fore-mentioned strawmen or trader-chiefs.

The preparation and implementation of indirect rule gave rise to many colonial ethnographic documents describing migratory traditions, populations’ ethnic origins, socio-political institutions and rules of succession underlying diverse forms of leadership. Based on such administrative ethnographic reports, territorial divisions were made and revised, populations regrouped and relocated, and customary chiefs promoted and deposed. The process was geared towards administrative centralisation to the detriment of smaller-scale and segmentary groups, which were regrouped and relocated to fit into arbitrarily constituted territorial units.Footnote21 In search of a basis for indirect rule, colonial administrators tried to disentangle institutions that were historically interwoven.Footnote22 They were often confused and disagreed with one another, creating ‘hierarchies of credibility’, yet aspired to a certain level of social consensus centred on European moral and political preferences about the suitability of institutions for indirect rule.Footnote23 The pictures colonial agents painted of local rulers also alternated over time along with newly-set goals and difficulties encountered in administering their territory, either idealising or demonising them in line with the measures they needed taking.Footnote24 The fact that customary chiefs were easily deposed and replaced, depending on the success and docility with which they performed their duties, created an opening for other powerbrokers to make their move. In a context in which administrative divisions and indirect leadership were regularly reassessed, institutions such as nebeli and anioto became important instruments to manipulate the outcome of power struggles.

Customary chieftaincy as defined by indirect rule was also purged from all practices which the colonial government thought inappropriate. It was one-sidedly based on formal patrimonial authority, characterised by patrilineal succession and inheritance of lands and shrines. Additionally, chiefs became responsible for organising tax collection, plantation work, and road construction. These activities did not necessarily improve the life of their subjects, perhaps even on the contrary. This created further discrepancies between chiefs’ tasks as civil servants and emic notions of leadership. The latter favoured big-man-like talents, of which metaphysical power, often distrusted by the government, was an intrinsic part. Vansina first referred to the Melanesian model of the big man to define the prototype of leadership in Bantu cultures. Originally, leadership was not hereditary but based on the merit of a charismatic, awe-inspiring person, who could mobilise people, attract and redistribute wealth, attract women, safeguard the community’s wellbeing, and be brave and successful in warfare.Footnote25 Even when evolving into hereditary systems, leadership in Central Africa still retained this big-man component. Moreover, big-man-like personal skills were not only valued in leaders among the Bantu, but also among Sudanic speakers such as the Mangbetu and the Azande discussed in this paper.Footnote26

Both in Melanesia and Central Africa, big-man-like talents are equated with supernatural qualities, or at least with the leader’s ability to attract and steward ritual institutions such as oracles and charms procuring him or her, with metaphysical support.Footnote27 For instance, chiefs consulted oracles to make important decisions in warfare or in order to judge witchcraft accusations.Footnote28 The colonial government did not always approve of such means as instruments in support of customary rule, and at least partly neglected the big-man-like factor in leadership by officially favouring hereditary succession. If hereditary succession of a chief by the eldest son in line was the rule, chiefs or their advisors regularly preferred another successor. This occurred for instance when consulting an oracle to assess the leadership qualities of a candidate, who could then be designated as successor in the chief’s testament.Footnote29 Aside from fixing rules of succession, the colonial authorities forced customary chiefs to renounce many of the metaphysical, coercive and remedial practices they actually needed to sustain their legitimacy and keep people in check. As a result, chiefs often found themselves in a catch-22 situation: either they obeyed the colonial authorities with the risk of losing power in the eyes of local people, or they continued practices that colonial law forbade, risking detention, relocation and even death sentence. The cases of anioto and nebeli will illustrate how chiefs resorted to the last option to hold on to their position.

The populations discussed in this article derive from several language families. They met during migrations and settled on the border between rainforest and savannah, giving rise to a variety of societies. Given the differences between them, colonial agents appreciated these populations and their institutions differently in the implementation of indirect rule. The Mangbetu and Azande societies had a more or less centralised political organisation, whereas the Bantu-speaking Bali and Budu to their south had a rather loose, egalitarian socio-political organisation in which leadership of the village was shared between titled persons.Footnote30 If in the centralised systems, colonial and other foreign interferences stirred up violent succession struggles, colonial indirect rule and appointments of customary chiefs were even more complicated in less centralised societies. An organisation into chiefdoms was imposed where none had existed before. Nowadays the first chiefs who are remembered among the Bali, from whose lines the current chiefs still descend, were the ones first installed under indirect rule. Their principal token of rule was the medal. This is different among the Mangbetu and Azande where genealogies of leadership date back much longer.Footnote31 The differences in historical depth of chiefdoms’ genealogies, wherein the first Bali and Budu chiefs are associated with the colonial government’s medal, points to uneven levels of invention of customary authority.

The colonial assessment of the segmentary political institutions of the Bali and their neighbours parallels that of the Lega and Bembe further south. Daniel Biebuyck, who studied the bwami boys’ initiation as the basis of the segmentary organisation of the Lega and Bembe in Belgian Congo in the 1950s, wrote:

My initial introduction to these associations was rapidly cut short because the colonial administration considered most of them as ‘subversive,’ as centers of resistance and political rebellion, contrary to law, order, and the civilising mission of the Belgian government. Hence, most were forbidden and apparently dissolved by law or by local administrative decrees and decisions.[…], but the practices certainly continued ‘secretly’ and on a reduced scale,Footnote32

The categorisation of institutions as immoral and anti-colonial was not limited to segmentary societies. In contexts where centralised hegemonic political institutions co-existed with others, those institutions with a counter-hegemonic potential were outlawed. This happened with nebeli among the Azande in Northeast Congo and South Sudan.Footnote35 Membership of initiation societies such as bwami, the regular boys’ initiation, and nebeli, another kind of initiation society, was not necessarily secret in itself. However, members were obliged to keep the secrets of the initiation and the esoteric knowledge acquired. That ‘secrecy’ was a thorn in the eyes of the colonial administration and inspired rumours about indecent practices. The category of ‘secret societies’ became a taxonomical device lumping together a diversity of institutions considered threatening to the colonial order. The term was mostly attributed to initiation societies such as bwami or nebeli, in which a vow of secrecy and absolute loyalty was demanded from the members. However, new religious movements, for instance African churches, were equally designated as secret societies or sects, although they were not esoteric. Ironically, colonial repression rendered them more secretive and elusive than they previously were.Footnote36 Even if such phenomena did often entail elements of critique vis-à-vis the colonial government, their deliberate rebellious and immoral character was often exaggerated, and propagated as a reason to outlaw and repress them.Footnote37 Sometimes the only pretext for considering them as rebellious was the fact that initiations hindered people to fulfil their duties, such as plantation labour and the maintenance of roads, as was the case for bwami. Comparatively speaking, nebeli still gained some sympathy among a few colonial administrators, whereas anioto never did – if hemp-smoking and sexual liaisons were seen as relatively minor forms of misbehaviour according to Euro-Christian moral standards, the seemingly arbitrary anioto killings were highly repulsive ().

Anioto among the northern Bali chiefdoms

The colonial assessment of local institutions created biases in perception, casting into oblivion many institutions which played an active role in local political culture. This section discusses how customary chiefs engaged with such institutions, contrary to what the government expected, to maintain their positions in competition with other powerbrokers. The cluster of cases outlined here centers on chief Mabilanga of the Babamba, a subgroup of the northern Bali. Other protagonists are his neighbours, chief Abopia and ex-chief Mbako, who respectively got convicted in the first and last of Congolese leopard-men trials in 1920 and 1936. After Abopia’s death penalty in 1920, Mabilanga claimed control over the former’s chiefdom (Badi), and asked Mbako to provide him with leopard-men to settle his authority there. The intersecting activities of these men provide insight in the power dynamics underlying leopard-men killings and how these became an effective strategy in the context of indirect rule, equally used by appointed customary chiefs.

Mabilanga’s case demonstrates that the concept of ‘customary’ leadership under indirect rule was a relative one, since Mabilanga was not the legitimate successor in line, nor had his father been. Mabilanga’s father Adudu had roots in the neighbouring Badi chiefdom of Abopia, yet moved to the Babamba due to a conflict, and married the daughter of the latter’s chief. Adudu then became the first intermediary chief in 1898, because the real Babamba chief – his father-in-law – did not dare to present himself to the colonial administration, represented by two former slave-traders. Years after Mabilanga retired as a railroad worker (from 1902 to 1910), he followed in his father’s footsteps and became the Babamba chief in 1918. When his neighbour Abopia got convicted in 1920, Mabilanga became the chief of a new ‘secteur’ that joined Abopia’s Badi chiefdom with his own. A series of killings in the Badi territory in 1921–22 was meant to subject the population to his authority. For this purpose, Mabilanga ordered anioto from Mbako, who initiated Mabilanga’s uncle Odini and brother Zene, who thus founded their own gang. Mbako, once a government-appointed chief, had been deposed because of his involvement in leopard-men killings since 1909, but had repeatedly escaped convictions. Until the 1930s, Mbako secretly facilitated the formation of leopard-men gangs and the exchange of gangs between his associates, including Mabilanga, thus initiating numerous killings over several decades.

Since the precolonial era, leaders of mambela had controlled anioto activities as part of retributions in local jurisdictions and to resolve community problems. Leopard-men actions principally required the approval of a committee of mambela notables, particularly the tata ka mambela, the leader of the initiation, and the ishumu, the customary guardians of clan sections in the village. The latter selected and initiated anioto, building on the mambela initiation.Footnote38 In later investigations, which led to his hanging, Mbako admitted he had challenged the mambela officials by not requesting their consent in the use of leopard-men killings and even casting suspicion on them.Footnote39 The same occurred in other cases at the time, demonstrating that the older mambela-controlled order was crumbling under the imposition of chieftaincy under indirect rule. However, Mbako’s and other cases show that mambela leaders remained principal suspects for leopard-men killings in the eyes of colonial administrators, and easy scapegoats to their contenders. As explained above, contact history had brought forth various powerbrokers who continued to try their luck in the competition for chiefly titles, which gave access to land, resources and people, leading to succession struggles. Colonial interferences in local power structures, including successive territorial reorganisations, as well as arbitrary installations and depositions of chiefs where none had existed, created frictions and contributed to a proliferation of cyclical, retaliatory leopard-men violence in the 1920s and 1930s. Sources suggest that towards the 1930s, every self-respecting Bali man relied on leopard-men. Leopard-men killings gained momentum as an efficient covert strategy to scare off rivals and to retain a grip over populations, while evading colonial control. Customary chiefs faced the problem of having to fulfil their (unpopular) duties for the colonial government, while mambela authorities tried to keep the chiefs under control, and rivals challenged them.Footnote40 To stand a chance, customary chiefs equally resorted to anioto strategies, even if they risked detention or death penalty.

Mabilanga and his contemporaries, including appointed customary chiefs, adopted anioto for the same purposes and used similar strategies. However, Mabilanga’s case is also unique because few customary chiefs were as successful in balancing the divergent expectations linked to their position. Most chiefs suspected of leopard-men killings were at the least deposed or relegated, but they were hung when their complicity was sufficiently proven, as were several of Mabilanga’s neighbours.Footnote41 Mabilanga’s motives tied in with extracting vengeance in his father’s name, who had left the Badi in conflict, but Mabilanga also wanted to extend his power over this group. Inherited conflicts and extraction of vengeance were common reasons for leopard-men killings under colonialism. Initially, Mabilanga sent his anioto to the Badi’s hegemonic lineages, but he subsequently changed his strategy, and sent them to their ‘adoptive clans’ (‘Babalisés’) who had been administratively incorporated into the Badi chiefdom against their will. These clans (Bavombo and Baveyzu) were Mbuti minorities who spoke different languages. The formerly convicted chief Abopia had been using anioto to keep these clans under control. Mabilanga now equally started attacking them to raise suspicions against the Badi, who suffered from a bad reputation as leopard-men since Abopia’s trial. In leopard-men cases, such divide-and-rule strategies were common – they consisted in attacking the enemy of one’s enemy, thereby casting suspicion on the latter, or to sow chaos in an enemy’s chiefdom, to make the administration doubt the chief’s ability to keep order. While a few colonial administrators came to understand Mabilanga’s strategies, others conveniently ignored the violent exploits of this prolific chief, who seemed a reliable indirect ruler. Mabilanga kept his subjects under control, made sure roads were in order and plantations thriving. The administrative documents discussing Mabilanga’s complicity reveal the ‘hierarchies of credibility’ at work among the administrators.Footnote42

One of the investigating officers, Leon Brandt, was well aware of the testimonies against Mabilanga, yet refrained from arresting him: ‘The name of chief Abianga [Mabilanga] was often cited during the investigation: I do not think I could send him to you for the moment, deeming his presence necessary to maintain order in his chieftaincy (Babamba).’Footnote43 Brandt also chose not to investigate injuries and deaths suffered by the gang members. A girl whose parents were killed testified that her father hit Mabilanga’s brother Zene with a spear in his foot, while Zene maintained he was bitten by a snake. Brandt did not investigate such matters, and Mabilanga’s gang continued to threaten and punish witnesses for testifying against them. In 1924 District Commissioner Laurent’s report did point out Mabilanga’s involvement that led to his arrest, but Brandt and his associates criticised the report as imprecise and exaggerated, and the blame was put once again on the Badi. Upon Mabilanga’s return from detention, the killings among the Badi’s adoptive clans continued. In investigations against Mbako in the 1930s, older unresolved leopard-men cases were revisited, including Mabilanga’s, and Laurent’s contested report of 1924 was reinstated. Zene’s ex-wife for instance stated that Zene’s foot injury was indeed caused by a spear instead of a snakebite, confirming the old testimonies against Mabilanga.Footnote44

These intersecting cases demonstrate the institutional dynamics underlying the adoption and spreading of anioto among diverse powerbrokers, including government-appointed chiefs, to survive in a competitive atmosphere. Indirect rule contributed to frictions between different contenders for chieftaincy, where such a position had never existed. This situation mobilised those seeking to boost their power as well as those desiring to protect their autonomy. People such as Mbako who had once been a government-appointed chief, and had probably profited from this position to escape mambela control, took the liberty to distribute leopard-men to all who desired them. In doing so, he placed himself at the heart of a powerful-yet-covert exchange network that supplied government-appointed chiefs as well as others. The colonial government, indirectly complicit in creating this situation, opportunistically turned a blind eye if anioto attacks turned out in its favour. This highlights the contrast between the fake certainty of institutional categorisations, informed by the theoretical and moral blueprints of indirect rule, and the fluidity of practices.

Nebeli, a collective therapy in political history

Nebeli was one of several initiation societies in Northeast Congo and South Sudan centreing on the distribution and use of magico-medicinal substances and charms, generically called dawa in historical sources (Kiswahili for medicine). Nebeli has existed longest among the Mangbetu, from approximately the 1850s until today.Footnote45 It was mentioned by Evans-Pritchard as one of several ‘closed associations’ existing among the Azande in South Sudan in the 1920s, most of which also existed on the Congolese side of the border until today. In this region, nebeli and other closed associations spread widely among Bantu, Sudanese and Nilotic language speakers. In essence these associations strongly resemble ‘collective therapies’ of Bantu populations described by Janzen.Footnote46 These therapies centre on curing social ills and guaranteeing the wellbeing of the community, but also challenge and attack those threatening that wellbeing. The ritual authority emanating from them was a significant catalyst in the development of political institutions in history, since they could consolidate or contest authorities in place, modulating between hegemonic and counter-hegemonic roles in society.Footnote47 As a consequence, they display great institutional variety, and resist categorisation. Historically, one of the best known forms of collective therapies were therapeutic insurgencies, which contested failing authorities and remedied social ills, whereby medicines and charms were used to attack and render people invincible in battle.Footnote48 Janzen’s description of Bantu collective therapies fits very well with nebeli and other societies in the same region.

Leadership in nebeli, and other collective therapies, was based on esoteric knowledge of magico-medicinal plants and recipes, connected to metaphysical forces, and obtained in expensive initiations.Footnote49 In the earliest phases of spreading, these phenomena often developed from below, but when successful, their leaders could become very wealthy and powerful people, and even overrule chiefly authorities. Therefore, if chiefs could not beat these associations, they often joined them to reinvigorate their authority, forcing their subordinates and populations to become members. Mangbetu rulers commonly assimilated cultural elements of conquered populations, and thus adopted nebeli ritual specialists at their courts. The word ‘nebeli’ was often regarded as a Mangbetu term, of which the prefix ‘ne-’ was dropped when adopted by Bantu or Ubangi speakers, but it more likely originates from the Bantu term libeli associated with water spirits.Footnote50 Nebeli gained momentum as a Mangbetu war charm and a substance to empower royal bodies and objects, such as the double bell nengbongbo. The Mangbetu’s successes in warfare, also against colonial armies, caused nebeli to spread.Footnote51 Among the Azande, nebeli appeared just before 1900 as a power protecting commoners against the arbitrariness of their rulers and the colonial government. Both the latter strongly opposed nebeli, yet could not suppress it. In later decades, Azande chiefs would commonly adopt it.Footnote52

The fact that collective therapies could mobilise people for battle explains why both the British and Belgian colonial governments feared them, framed them as ‘secret societies’ and rendered them unlawful. In the era of colonial conquest nebeli had a particularly negative reputation among colonisers and notably Norbertine missionaries in Congo.Footnote53 The missionaries claimed that people were initiated against their will, and represented nebeli as a devilish, immoral association. They associated it with sexual promiscuity, hemp smoking and criminal activities such as extortion and murder. The nebeli lodges named lubasa, situated in isolated places in the forest, gave shelter to those fleeing forced labour, rubber tax, army services, and missionary influence. Nebeli charms, particularly the whistles, were used as war charms and to kill people who threatened the community’s wellbeing, specifically whites. However, as the following case shows, nebeli’s main purpose was protection rather than anti-colonial subversion.Footnote54

Around 1910 in Stanleyville (Kisangani), a number of colonial administrators were initiated into nebeli, including the Provincial Governor Charles Delhaise, who founded the first Freemason’s lodge in Congo.Footnote55 Delhaise and his peers acknowledged nebeli as a candidate institution for indirect rule, which was not to the liking of missionaries and other Catholic-minded figures.Footnote56 Delhaise almost lost his position when the death of a white subordinate, who had pursued initiation, was falsely attributed to nebeli. In court, the victim’s white fellow-initiate was pressured into revealing the oath he had sworn:

I promised the initiates of nebili [sic] not to hit them with the chicotte, to give them everything they ask, to intercede with their chiefs to help them, to recognise the Big Chief [of nebeli] as my leader and to rank myself as a junior initiate among them, since I was the last to be initiated; not to wage war against them and inform them if this were to happen, to offer support at any time and any place; to recruit new members, to assist them in their vengeance, to provide them with weapons, to give shelter to nebeli members who would seek refuge with me if they were pursued by law.Footnote57

In the 1920s and 1930s, nebeli seems to have vanished but people continued to adhere to it in a hidden way, most notably chiefs. In the wider region, chiefs had learnt to use nebeli as an instrument to control their subordinate chiefs and populations, forcing the latter to be initiated and obey its rules.Footnote58 In the 1940s and 1950s, nebeli revived among the eastern Azande in two neighbouring chiefdoms, Ndolomo (Doruma) and Wando (Dungu), where nebeli constituted a larger network under the direction of a supreme leader Emboli.Footnote59 The British and Belgian governments closely watched nebeli’s developments alongside those of kitawala, a syncretic movement combining elements of collective therapies and Watchtower Christianity.Footnote60 They merely saw nebeli’s tendency to criticise and disturb colonial rule, and ignored its complex and nuanced societal role, as appears from the following case.

In 1943, the colonial government deposed chief Basia of the Azande chiefdom Ndolomo (Doruma) and replaced him with the young chief Ukwatutu. Several nebeli leaders in Northeast Congo and South Sudan had resorted to nebeli ritual to keep Basia in function but to no avail. The colonial authorities had bypassed another senior member of the reigning family to replace Basia, Komboyega. Komboyega had been banished earlier for spreading nebeli, and upon his release instigated a revival among the eastern Azande, which shows that he was an ambitious and influential man. Komboyega used nebeli to manipulate Ukwatutu’s subjects, which meant he blocked them from doing their labour tasks or paying their taxes to the chief. An administrator wanted to sanction Komboyega for harassing Ukwatutu:

On 21 December 1949, I was approaching Komboyega’s village at 7am, but he only showed up around noon, after performing magic incantations the whole morning, accompanied by multiple gunshots to ward off the sanctions I was going to impose. If he would have gotten absolution, this would have demonstrated his magic power to Doruma’s inhabitants and attract many new followers to the sect [nebeli]. The young chef Ukwatutu will never have his chiefdom in hand as long as Komboyega remains in the territory.Footnote61

These eastern Azande cases demonstrate that the nebeli network’s political impact transcends its categorisation as anti-colonial resistance, revealing itself in the power play at the heart of the big chiefly houses in the region. It had a more profound metaphysical role beyond mere political struggle, as illustrated by its divinatory role in discovering the cause of a chief’s illness, and offering protection against colonial arbitrariness. Nebeli’s role in succession struggles also forces us to see the latter as negotiations of metaphysically legitimate leadership.

Revisiting local debates of leadership in the past and today

A comparison of anioto and nebeli helps uncover patterns which advance our understanding of chiefly authority under colonial rule as multifaceted and negotiated. By comparing these cases, we go beyond their micro-historical scope and contemplate institutional dynamics and underlying cultural logics on a larger scale. In addition, these historical cases help improve understandings of Congolese political cultures today, which display similar logics, dynamics and debates of leadership.

Comparatively speaking, anioto and nebeli are different institutions, rooted in other cultural contexts and distributed over different but partly overlapping geographic areas, with nebeli covering a larger region. Nebeli was a beneficial, healing power, and anioto a ritual kind of violence used by village leaders for judicial purposes and punishments, to maintain order. Despite differences, anioto and nebeli converge in how and for what purposes leading figures used these institutions, either in favour of or in opposition to colonial powers. In the competitive atmosphere under indirect rule, both were instruments of coercion that inspired fear. Powerbrokers used them to keep one’s own people and one’s rivals in check. They sent anioto and nebeli to sow disorder in their rivals’ territories or communities to make the latter appear inefficient leaders or troublemakers. They falsely accused rivals of using anioto and nebeli to shift attention away from their own involvements. Other convergences are their metaphysical and esoteric nature, requiring the member’s vow of secrecy upon initiation, but discretion was equally expected from the whole community. Indiscretion was punished, which rendered such phenomena difficult to monitor by outsiders, notably the colonial government. Anioto and nebeli often played a role in succession and land conflicts, but also in the extraction of vengeance for deaths of family members, run-away wives and thefts. Colonial justice failed to adequately address such matters, which made locals appeal to their leaders for providing justice and protection by other means.

The historical cases teach us that government-appointed chiefs and other powerbrokers tried to bring diverse power bases, including forbidden ones, under their control, to be successful and legitimate leaders. Anioto and nebeli spread, adapted to different circumstances, and actually merged among the Bali in such processes. The resulting syncretic institution, named basa or ambodima, promoted the spread of leopard-men skills to resolve community problems, yet under the cover of a public travelling dance performance.Footnote63 Institutional dynamism is constituted par excellence in such bricolage but also in the modulating, adaptive nature of anioto and nebeli being used pro and contra the colonial government. Anioto and nebeli converged in the logic – intrinsic to Central African leadership – that the coercive, violent side of power is necessary to purge society from undesired governance and restore order.Footnote64 The institutional dynamism of the historical cases and its legacy and logic still permeates the contemporary political landscape. The following paragraphs demonstrate that firstly, contemporary chieftaincy is still negotiable with constituents, most clearly so in succession struggles; secondly, that collective therapies and ritually-empowered militias are still relevant to negotiations of leadership, entailing metaphysical and moral debates of governance wherein violence assumes a therapeutic role; and thirdly, that hegemonic and counter-hegemonic phenomena cannot be strictly separated in a binary opposition, but are interdependent and subject to the same logic within dynamic institutional networks.

Institutional dynamism accounts for customary chieftaincy’s resilience in the face of repeated post-colonial ruptures. The anti-imperialist Simba rebellion, which permeated the region in 1964, targeted European and African elites deemed complicit with the colonial regime – and particularly customary chiefs. Yet this did not permanently undermine chieftaincy. Mobutu’s effort to suppress customary chieftaincies in the early 1970s also proved unsuccessful. Few studies explored the recovery of customary chiefs during and after such periods of upheaval, including the Congo Wars. Kristof Titeca recently argued that, between 2007 and 2011, violent Ugandan Lord’s Resistance Army attacks had a mixed impact on chiefs’ positions. As in other Congolese regions, the post-colonial survival of chiefly authority resulted from the limited presence of the state – chiefs were the nearest, most legitimate and only authority to rely on for security and justice provision, even when limited and not accessible to all.Footnote65 The LRA conflict increased spatial splintering of authority, wherein chiefs shortly boasted their position, especially when protecting their community with ritually-empowered self-defense forces. In the end, the chiefs proved incapable to stop the LRA, were killed or fled, which eroded their legitimacy. New actors attracted by the conflict further challenged the chiefs, such as the national army and international organisations, mostly MONUSCO, providing alternatives for justice and security, but from whose help the region had previously been deprived. The national army pursued the chiefs’ self-defense groups, as the government perceived them as a threat. International organisations criticised chiefs’ human rights violations, but largely withdrew again after 2012. Titeca points out that chiefs engaged in forum-shopping, a term borrowed from Benda-Beckman, to renegotiate their position with these actors, but that their legitimacy depended mostly on local constituents’ approval.Footnote66

Contemporary chiefs’ actions resemble colonial-era leaders’ bricolage in composing power from whatever means accessible, including practices frowned upon by government. Contemporary political and development science’s concepts such as forum-shopping, influence-peddling, extraversion and militarisation have been analytically valuable for analysing contemporary leaders’ political agency. These terms and their discursive backgrounds are not generally geared towards studying metaphysical and ritual aspects of local governance, particularly the esoteric and hidden ones, which still play a role. This article does not seek to assess the relevance of these contemporary concepts, but rather seeks to use the historical cases to verify the continued relevance of their institutional dynamism and cultural logic in contemporary practices, for instance in successions. Succession struggles remain common, often rooted in previous generations, and reveal similar logics and dynamics than in the past.Footnote67

Chiefly positions are still encapsulated in state structures, officially destined for the eldest heir in line. Like under colonial rule, the choice for a candidate remains contingent upon the chief’s testament and the approval of his advisors.Footnote68 Such advisors participate in the chiefdom’s council and are selected among the categories of elders (vieux sages), whose authority is based on life experience, ‘guardians of custom’ or ritual specialists, and the reigning family. Similar to the colonial era, the chiefdom’s council is organised, supervised and reported on by state officials, but the latter’s administrative reports do not reflect underlying dynamics and longer-term processes.Footnote69 One young informant explained that his father, a Bangba chief, consulted the oracle at the birth of each of his children to verify who was suitable for chieftaincy. The informant, approved by the oracle, underwent preparatory rituals together with his brother, of whom the oracle had similarly approved. Upon the chief’s death, the reigning family preferred the informant’s brother, because he was better educated.Footnote70

Chiefs’ advisors thus use their influence to manipulate successions, to coerce chiefs, side with their contenders, and suspend them.Footnote71 In this issue, Hoffman et al. examine a contemporary succession conflict in eastern Congo, demonstrating its complexities. The discourses still center on the candidate’s ability to promote well-being, which depends on several factors such as education and political and economic leverage, but also particularly on respect for customary conditions and procedures.Footnote72 That chiefs neglect their chiefdoms and customs is often cited as the root-cause of society’s poor state in contemporary Northeast Congo. Contrary to expectations, chiefs seldom are physically present in their chiefdoms, as they travel to attend to their businesses, connected to artisanal gold or diamond mining, or reside in the city.Footnote73 Coercion is required to appoint the right chief and to keep the latter in check for the chiefdom to prosper. One Azande chief explained how the reigning family pressured him into succeeding the deceased chief, in accordance with the latter’s testament, and threatened him when he declined, since he was regarded as the most suitable candidate to face the chiefdom’s challenges.Footnote74 Such threats can come in the form of ‘poison’, as in the nebeli cases, referring to the use of magico-medicinal substances, charms and spells to harm and coerce a person. Today, chiefs are reluctant to publically announce the name of their desired successor, for he might be ‘poisoned’ if members of the reigning family would not agree.Footnote75 Such practices require the help of so-called ‘sorcerers’ or féticheurs.

A common regional saying is that ‘the chief knows all the sorcerers, since he is the biggest sorcerer of all,’ yet ‘sorcerers’ also control the chief. The guardians of custom are in fact ‘sorcerers’ tied to the chief’s court, providing guidance and protection in the chief’s exercise of power, for instance through oracle divination. In Haut- and Bas-Uele Provinces the collective therapies once mentioned by Evans-Pritchard, mani, nebeli, kpira and sahula, are still salient in different domains of life, but most notably in politics, even if Christian authorities and new elites eschew them.Footnote76 The triangular use of protecting, harming and healing remains intact. Kpira is widely used to block enemies or rivals, and one chiefdom relied on it for stopping LRA from crossing the Uele River, which did not happen since 2011.Footnote77 As in the past, chiefs ‘jealously’ maintain their monopoly over such means, while the guardians control the chiefs, yet independent practitioners break loose from chiefly control. The specific operations are still esoteric and subject to discretion, but the community is distantly aware and considers them as its strength, relying on them for protection, as in the example of kpira. In eastern Congo similar attitudes exist toward MaiMai militias, bringing us to discuss the relevance of therapeutic violence today.Footnote78

Metaphysically-inspired violence is still mostly associated with rebel or informal actors defying state authority, such as Simba and MaiMai.Footnote79 In Western popular media and trials, activities of such militias are still perceived as incomprehensible and irrationally violent.Footnote80 Such biased understandings determined colonial perceptions of leopard-men, and reappeared for Simba, MaiMai, and the LRA, who – although coming from Uganda – have similar features.Footnote81 However, the logic of therapeutic violence also applies to institutions coopted and sanitised by the government, despite the latter’s control. Azande chiefs’ self-defense groups in the LRA conflict also operated according to this logic to protect the community as they had done during the Simba rebellion and the Congo Wars.Footnote82 Even when such militias are not born out of chiefs’ initiatives, local populations – and their chiefs – have a tendency to embrace them as a ‘necessary evil’ to protect themselves, as is the case for MaiMai in east Congo.Footnote83 Both historical leopard-men and contemporary MaiMai are associated with the concept of bolosi (bulogi), a Bantu term that refers to retaliatory magic or witchcraft which is socially approved if used for protection, particularly by a leader.Footnote84 Hoffman et al. discuss how chiefs liaise with MaiMai for armed protection, with both parties propping up each other’s claims that their power is legitimately rooted in custom.Footnote85 An informant said that contemporary chiefs have lost power compared to the past – they used to be mean to people, but nowadays they cannot be mean anymore or they will be deposed.Footnote86 This ties in with the logic that powerful chiefs are traditionally mean, but now they have to reckon with human rights advocacy, as in the LRA context. Discourses on chiefs’ power often entail critiques of their failure to deal with social ills and witchcraft appropriately due to the loss of spiritual power. Still there also are powerful chiefs who are feared for their spiritual forces, who amass wealth and liaise with MaiMai groups.Footnote87 A chiefs’ ability to control ritual, spiritual and coercive means appears as necessary today as in the past, regardless of their disapproval by the state or peacebuilding agencies.

Conclusion

By studying anioto and nebeli, one recognises that the colonial recasting of customary powers in an oppositional framework created blind spots and biases, and tells us more about colonial discursive approaches to local systems of rule than about local power practices.Footnote88 Through the excavation of archival and judicial records, the study of chiefly power objects, therapeutic charms and oral histories, this article pierced through some of these biases and blind spots, examining customary chiefs’ appropriation of anioto and nebeli in their power struggles under indirect rule. This approach uncovers a potent domain of African agency where chiefs negotiate their position by rising up to different expectations and challenges. Their behaviour points to processes of trial and error and gives insights in micro-historical dynamics that help to diversify macro-historical insights in the region’s political and institutional history. This further presses us to draw upon a comprehensive understanding of local institutions as enmeshed in networks, as resisting categorisations in either political or religious, hegemonic or counter-hegemonic terms, and as historically-grown and adaptable to various circumstances. The study of such networks, using micro-historical case studies to diversify insights on a macro-historical level, proves important to understand the neglected composite and flexible nature of customary power. To understand the legacy and logic of such networks is, in turn, crucial to unravel complicated contemporary problems such as the roots and dynamics of conflicts over successions, land and resources, and the ways in which these are fought out, including with violent means.Footnote89 Such insights can help minimise the risk of instrumentalising local authorities based on inherited colonial assumptions, and thereby generally improve developmental and peacebuilding interventions.

Acknowledgements

Research presented in this article was conducted as part of the network project CongoConnect funded by the BRAIN-program of the Belgian Ministry of Science coordinated by Ghent University. It has further been supported by ESRC GCRF grant number ES/P008038/1 and FWO, Flanders. Field research was conducted in collaboration with Prof. Charles Kumbatulu, University of Kisangani, and Prof. Roger Gaise, the University of Uele, DRCongo. A research fellowship at the American Museum for Natural History contributed to the findings underlying this article. Thank you to Dirk Seidensticker for the map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Lemarchand, Political Awakening, 45; Young, Politics, 128–33.

2 Eggers, “Mukombozi”; Feierman, “Colonizers”.

3 Kyed and Buur, “Introduction”.

4 Feierman, “Colonizers”; Johnston, “Criminal Secrecy”.

5 Pottier, “Representations”; Maxwell, “The Soul of the Luba”.

6 Feierman, “Colonizers”; De Jonghe, “Formations”, 56–63. Comhaire, “Sociétés secrètes”, 54–59.

8 Mamdani, Citizen and subject, 53. Schneider, “Colonial Legacies”; Leonardi, “Violence”; Loffman, “An interesting experiment”.

9 Leonardi, “Violence”, 535–58.

10 Komuniji and Büscher, “In Search of Chiefly Authority”.

11 This is discussed at length in the introduction to this issue. See Verweijen and Van Bockhaven, “Revisiting colonial legacies”.

12 Van Bockhaven, “Anioto”.

13 Vansina, Paths, 89.

14 Spear, “Neo-traditionalism”.

15 Biebuyck, Lega. Newbury, Kings. Delpechin, “From Pre-capitalism”.

16 Vansina, Paths, 167–91.

17 See Hunt’s concept of “nearness”. Hunt, A Nervous State, 9.

18 Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 181–236.

19 Czekanowski, Forschungen, 247; Massmann, An den Ufern des Ituri, 69–75; Salmon, Les Carnets, 68.

20 Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), Archives Indigènes et Main d’Oeuvre (AIMO), Winckelmans (1933: 3); Schebesta, Vollblutneger, 64–6, 69–71.

21 RMCA AIMO Hackars (1919), Strubbe (1920); Hulstaert, “Une Lecture Critique”, 33–5, 37; Muchukiwa, “Territoire Etniques”.

22 F.ex. Moeller, Les Grandes Lignes, 482–3.

23 Stoler, Along the Archival Grain, 181–236.

24 Ivanov, “Cannibals”, 189–93.

25 Vansina, Paths, 71–7. Sahlins, “Poor Man”, 285–303.

26 Schildkrout and Keim, African Reflections, 175.

27 Sahlins, “Poor Man”, 294–5.

28 Schildkrout and Keim, African Reflections, 185–6.

29 Interview, Niangara, November 2018.

30 Vansina, Paths, 167–91.

31 Interviews,Niangara, Dungu, November–December, 2017.

32 Biebuyck, Lega; https://danielbiebuyck.com/

33 RMCA AIMO, EA.0.0.224, 1933. Procès-verbal en vue de la suppression des cérémonies du "Mambela".

34 Schildkrout and Keim, African Reflections, 39.

35 Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, 511–24; Johnson, “Criminal Secrecy”, 170–200.

36 De Jonghe, “Formations”, 56–63. Comhaire, “Sociétés secrètes”, 54–59.

37 Johnson, “Criminal Secrecy”.

38 Bouccin, “Crimes ”, 185–92 ; Belgian Foreign Office (BFO), Africa Archives (AA), JUST GG 3043 (5574), Public hearing, Wamba, 19 June 1934.

39 Van Bockhaven, “Anioto”.

40 Ibid.

41 Marrevée, “Die Anyotos”; Joset, Les Sociétés secrètes, 64; RMCA AIMO De Bock (1932).

42 BFO AA GG 21419, Report by the District Commisioner Laurent, “Meurtres d’anioto dans le secteur Babamba-Agissements du chef Abianga et Consorts”, 26 November, 1924.

43 AA GG 21419, Letter and Reports by Police Investigator L. Brandt, 12 May 1922–24 July 1922; RMCA AIMO Brandt (1923).

44 BFO AA AIMO 13611. Report on chief Mabilanga of the Bekeni by Bouccin, Kondolole, 29/10/34.

45 Schildkrout and Keim, African Reflections, 190–1; Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, 511–24; Mbali, “La Société Secrète Nebheli”

46 Johnson, Nuer Prophets; Middleton, “The Yakan or Allah Water Cult”.

47 Janzen, Ngoma.

48 Hunt, A Nervous State, 11–2; I consider “therapeutic insurgencies” as a manifestation of “collective therapies”.

49 Evans-Pritchard, Witchraft, 511–3. Lagae, Les Azande.

50 Hunt, A Colonial Lexicon, 38; Vansina, The Tio, 75–6.

51 Keim, Precolonial Mangbetu Rule; Schildkrout and Keim, African Reflections, 191.

52 Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, 511–24.

53 Bauwens, “De Apostolische Prefectuur”, 261–7.

54 Ibid.

55 Delathuy, Missie en Staat, 291, 301–2, 337; Documentation Center, Masonic Grand Lodge of Belgium, file L’Ere Nouvelle.

56 de Calonne-Beaufaict, “La Pénétration”.

57 BFO AA GG 4769 (S. 2433)

58 RMCA, Archives of Father B. Costermans, files on Sects.

59 BFO AA GG 12229; Salmon, “Sectes Secrètes Zande”.

60 Salmon, “Sectes Secrètes Zande”; BFO AA GG 11849.

61 BFO AA GG 10987, Letter “Proposition relegation Notable Komboyega, Chefferie Doruma” by Territorial Administrator Liégeois, 28 December 1949; “Réunion du Conseil de Chefferie tenue à Doruma”, by Territorial Administrator Liégeois, 20 December 1949.

62 BFO AA GG 12229, PV de la Réunion du conseil de chefferie Renzi tenu au village Gilima, 15 September 1949.

63 Delathuy, Missie en Staat, 271–6; British National Archives, Congo papers, FO 367 69 006; RMCA AIMO, A. Boucin, “Note sur l’ambodima” (1933).

64 MacGaffey, Kongo, 220; Eggers, “Mukombozi”; Loffman, “An Interesting Experiment”.

65 Titeca, “Haut-Uele”. See also Flaam and Vlassenroot, “Quête de Justice” for justice provisions in this region.

66 Titeca, “Haut-Uele”.

67 Kyed and Buur, “Introduction”; Hoffman et al., “‘Courses au pouvoir’”.

68 Hoffman et al., “‘Courses au pouvoir’”; Administrative Archives, Haut Uele Province, Isiro.

69 Several documents in the Administrative Archives, Haut Uele Province.

70 Interview, Niangara, November 2017.

71 Administrative Archives, Haut Uele Province, Isiro; Interviews, Isiro, December, 2017.

72 Hoffman et al., “‘Courses au pouvoir’”.

73 Interviews in Haut-Uele, November–December, 2017.

74 Interview, Dungu, December 2017.

75 Interviews in Haut-Uele, November–December, 2017.

76 Interviews, Nangazizi, Niangara, November 2017.

77 Interview, Niangara, November 2017.

78 Verweijen, “The Disconcerting Popularity”.

79 Verweijen and Van Bockhaven, “Revisiting Colonial Legacies”.

80 Titeca, I testified at a Trial of Joseph Kony’s commander. Here’s what the jury did not understand. Washington post, 24 January 2019.

81 Allen and Vlassenroot, The Lord’s Resistance Army.

82 Titeca, “Haut-Uele”.

83 Wild-Wood, “Is it Witchcraft?”.

84 Van Bockhaven, “Anioto”.

85 Hoffman et al., “‘Courses au pouvoir’”.

86 Interviews, Isiro, December, 2017.

87 Verweijen, A Microcosm of Militarisation.

88 Feierman, “Colonizers”.

89 Mathys, “Bringing History Back in”.

Bibliography

- Allen, Tim, and Koen Vlassenroot. The Lord's Resistance Army: Myth and Reality. London: Zed Books, 2010.

- Bauwens, J. “De Apostolische Prefektuur van Uele.” Onze Kongo 4 (1913–14): 126–161.

- Biebuyck, Daniel P. Lega Culture; Art, Initiation, and Moral Philosophy among a Central African People. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973.

- Bouccin, A. “Crimes et superstitions indigènes.” Bulletin des Juridictions Indigènes et du Droit Coutumier Congolais 4, no. 8 (1936): 185–192.

- Comhaire, Jean. “Sociétés secrètes et mouvements prophétiques au Congo Belge.” Africa 25, no. 1 (1955): 54–59. doi: 10.2307/1156896

- Czekanowski, Jan. Ethnographie; Uele, Ituri, Nil-Länder, Vol. 2 in Forschungen im Nil-Kongo-Zwischengebiet. Leipzig: Klinkhardt, 1924.

- de Calonne-Beaufaict. “La Pénétration de la Civilisation au Congo belge et les bases d’une politique colonial.” Bulletin de la Société Belge d’Etudes coloniales 19, no. 9-10 (1912): 697–697.

- De Jonghe, Édouard. “Formations récentes de sociétés secrètes au Congo belge.” Africa 9, no. 1 (1936): 56–63. doi: 10.2307/1155240

- Delathuy, A. M. Redemptoristen, Trappisten, Priesters van het H. Hart, Paters van Mill Hill, Vol. 2 in Missie en Staat in Oud-Kongo (1880-1914). Berchem: EPO, 1994.

- Eggers, Nicole. “Mukombozi and the Monganga: The Violence of Healing in the 1944 Kitawalist Uprising.” Africa 85, no. 3 (2015): 417–436. doi: 10.1017/S000197201500025X

- Evans-Pritchard, Edward E. Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande. Vol. 12. London: Oxford, 1937.

- Feierman, Steven. “Colonizers, Scholars, and the Creation of Invisible Histories.” In: Beyond the Cultural Turn: new Directions in the Study of Society and Culture, edited by L. A. Hunt and V. E. Bonnell, 182–216. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Flaam, H., and K. Vlassenroot. “Quête de justice: conflit, déplacement et justice dans le Haut-Uele.” CAHIER DU CERPRU 25, no. 24 (2017): 115–127.

- Gaise N’Gazi, R, ed. La Rébellion de 1964 en RDCongo: Cinquante ans après. La Situation dans la Province de l”Uele. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2015.

- Hoffman, Kaspar, Koen Vlassenroot, and Emery Mudinga. “‘Courses au pouvoir’: The Struggle over Customary Capital in the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 1 (2020).

- Hulstaert, G. “Une lecture critique de L’Ethnie Mongo de G. Van der Kerken.” Études D’histoire Africaine 3 (1972): 27–60.

- Hunt, N. R. A Colonial Lexicon: Of Birth Ritual, Medicalization, and Mobility in the Congo. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Hunt, N. R. A Nervous State: Violence, Remedies, and Reverie in Colonial Congo. Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2015.

- Ivanov, Paola. “Cannibals, Warriors, Conquerors, and Colonizers: Western Perceptions and Azande Historiography.” History in Africa 29 (2002): 89–217. doi: 10.2307/3172160

- Janzen, J. M. Ngoma: Discourses of Healing in Central and Southern Africa, Vol. 34. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992.

- Johnson, D. H. Nuer Prophets: A History of Prophecy from the Upper Nile in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Johnson, Douglas H. “Criminal Secrecy: The Case of the Zande Secret Societies.” Past & Present 130 (1991): 170–200. doi: 10.1093/past/130.1.170

- Joset, P. E. Les sociétés secrètes des hommes-léopards en Afrique Noire. Paris: Payot, 1955.

- Keim, Curtis. “Precolonial Mangbetu rule: Political and Economic Factors in Nineteenth-Century Mangbetu History (Northeast Zaire).” PhD. Diss., Michigan: University Micro Films International, 1979.

- Komuniji, Sophie, and Karen Büscher. “In Search of Chiefly Authority in ‘Post-Aid’ Acholiland: Transformations of Customary Authorities in Northern Uganda.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 1 (2020).

- Kyed, H. M., and L. Buur. “Introduction: Traditional Authority and Democratisation in Africa.” In State Recognition and Democratisation in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by L. Buur and H. M. Kyed, 1–28. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- Lagae, C. R. Les Azande ou Niam-Niam: l”organisation zande, croyances religieuses et magiques, coutumes familiales. Brussels: Vromant, 1926.

- Lemarchand, René. Political Awakening in the Belgian Congo. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1963.

- Leonardi, Cherry. “Violence, Sacrifice and Chiefship in Central Equatoria, Southern Sudan.” Africa 77, no. 4 (2007): 535–558. doi: 10.3366/afr.2007.77.4.535

- Loffman, Reuben. “‘An Interesting Experiment’: Kibangile and the Quest for Chiefly Legitimacy in Kongolo, Northern Katanga, 1923–1934.” International Journal of African Historical Studies 50, no. 3 (2018): 461–476.

- MacGaffey, W. Kongo Political Culture: The Conceptual Challenge of the Particular. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Marrevée, A. “Die Anyotos.” Heimat und Missionen 6 (1928): 169–173; 7 (1928): 206–8; 8 (1928): 239–242; 9 (1928): 272–277; 10 (1928): 309–11.

- Massmann, Paul. An Den Ufern Des Ituri, Vol. V in Bereitet Den Weg. Aachen: Xaverius Verlag, 1920.

- Mathys, G. “Bringing History Back in: Past, Present, and Conflict in Rwanda and the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.” The Journal of African History 58, no. 3 (2017): 465–487. doi: 10.1017/S0021853717000391

- Maxwell, D. “The Soul of the Luba: WFP Burton, Missionary Ethnography and Belgian Colonial Science.” History and Anthropology 19, no. 4 (2008): 325–351. doi: 10.1080/02757200802517216

- Mbali, M. “La Société Secrète Nebheli et le pouvoir politique coutumier Mangbetu.” Cahiers d’Etudes et de Recherche Interdisciplinaire de l’Uele 4, no. 2 (2012).

- Middleton, J. “The Yakan or Allah Water Cult among the Lugbara.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 93, no. 1 (1963): 80–108. doi: 10.2307/2844335

- Moeller, Alfred. Les Grandes lignes des migrations des Bantous de la province orientale du Congo belge. Brussels: G. Van Campenhout, 1936.

- Muchukiwa, B. Territoires ethniques et territoires étatiques: pouvoirs locaux et conflits interethniques au Sud-Kivu (RDCongo). Paris: Editions L’Harmattan, 2006.

- Newbury, David S. Kings and Clans: Ijwi Island and the Lake Kivu Rift, 1780-1840. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

- Pottier, Johan. “Representations of Ethnicity in the Search for Peace: Ituri, Democratic Republic of Congo.” African Affairs 109, no. 434 (2010): 23–50. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adp071

- Sahlins, Marshall D. “Poor man, Rich man, big-man, Chief: Political Types in Melanesia and Polynesia.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 5, no. 3 (1963): 285–303. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500001729

- Salmon, P. “Sectes secrètes Zande.” In Etudes de geographie tropicale offertes a Pierre Gourou, 427–440. Paris- La Haye: Mouton, 1972.

- Salmon, P. “Les carnets de campagne de Louis Leclercq: Etude de mentalité d'un colonial belge.” Revue de l'Université de Bruxelles 22, no. 3 (1970): 1–70.

- Schebesta, Paul. Vollblutneger und Halbzwerge. Salzburg: Pustet, 1934.

- Schildkrout, E., and C. Keim, eds. African Reflections: Art from Northeastern Zaire. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

- Schneider, L. “Colonial Legacies and Postcolonial Authoritarianism in Tanzania: Connects and Disconnects.” African Studies Review 49, no. 1 (2006): 93–118. doi: 10.1353/arw.2006.0091

- Spear, Thomas. “Neo-traditionalism and the Limits of Invention in British Colonial Africa.” The Journal of African History 44, no. 1 (2003): 3–27. doi: 10.1017/S0021853702008320

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Titeca, Kristof. “Haut-Uele: Justice and Security Mechanisms in Times of Conflict and Isolation.” JSRP Paper 32 (2016): 1–26.

- Van Bockhaven, Vicky. “Anioto: Leopard-men Killings and Institutional Dynamism in Northeast Congo, c. 1890–1940.” The Journal of African History 59, no. 1 (2018): 21–44. doi: 10.1017/S002185371700072X

- Vansina, J. The Tio Kingdom of the Middle Congo, 1880-1892. London, New York: Oxford University Press for the International African Institute, 1973.

- Vansina, Jan M. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Pres, 1990.

- Verweijen, Judith, and Vicky Van Bockhaven. “Revisiting Colonial Legacies in Knowledge on Customary Authority in Central and East Africa in Past and Present.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 1 (2020): 1–22. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2019.1710366

- Verweijen, Judith. “The Disconcerting Popularity of Popular in/Justice in the Fizi/Uvira Region, Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.” International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 22, no. 3 (2015): 335–359. doi: 10.1163/15718115-02203003

- Verweijen, Judith. A Microcosm of Militarisation: Conflict, Governance and Armed Mobilisation in Uvira, South Kivu. In Usalama Project. Nairobi: Rift Valley Institute, 2016.

- Wild, Emma. “'Is It Witchcraft? Is It Satan? It Is a Miracle.’ Mai-Mai Soldiers and Christian Concepts of Evil in North-East Congo.” Journal of Religion in Africa 28, no. Fasc. 4 (1998): 450–467. doi: 10.1163/157006698X00242

- Young, Crawford. Politics in Congo: Decolonisation and Independence. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.