ABSTRACT

In much of Eastern Africa, the last decade has seen a renewed interest in spatial development plans that link mineral exploitation, transport infrastructure and agricultural commercialisation. While these development corridors have yielded complex results – even in cases where significant investments are yet to happen – much of the existing analysis continues to focus on economic and implementation questions, where failures are attributed to inappropriate incentives or lack of ‘political will’. Taking a different – political economy – approach, this article examines what actually happens when corridors ‘hit the ground’, with a specific interest to the diverse agricultural commercialisation pathways that they induce. Specifically, the article introduces and analyses four corridors – LAPSSET in Kenya, Beira and Nacala in Mozambique, and SAGCOT in Tanzania – which are generating ‘demonstration fields’, economies of anticipation and fields of political contestations respectively, and as a result, creating – or promising to create – diverse pathways for agricultural commercialisation, accumulation and differentiation. In sum, the article shows how top-down grand-modernist plans are shaped by local dynamics, in a process that results in the transformation of corridors, from exclusivist ‘tunnel’ visions, to more networked corridors embedded in local economies, and shaped by the realities of rural Eastern Africa.

A new wave of agricultural commercialisation is being promoted across Africa’s eastern seaboard.Footnote1 Development corridors, linking infrastructure development, mining and agriculture for export, are central to this. As a result, new spatial politics are being generated by such interventions, as formerly remote borders and hinterlands are expected to be transformed through foreign investment and aid projects.Footnote2 Ports, roads, mines and plantations are all linked in grand modernist visions. Many powerful actors are involved, from international corporates to states and domestic elites. But what actually happens on the ground? Do the grand visions play out as expected? Who gets involved and who loses out?

This paper introduces a special section including three articles – on Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania – that aim to go beyond the rhetoric and hype and delve into the realities as they play on the ground. As with the ‘land rush’ that followed the food and financial crises of the mid-2000s, the outcomes are not as expected, complicating the discourses of either those supporting or opposing large-scale land investments.Footnote3 However, wider state- and capital-promoted visions of modernist development linked to investment corridors do have material effects, we argue, creating new networks and practices, and fostering new processes of change.

Much discussion of growth and investment corridors has focused on economic development potential, and the multiple implementation challenges. Existing literature has focused on, for example, investment promotion and foreign investment flows; infrastructure as a growth and development constraint; the mechanics of spatial planning and spatial development initiatives; cost/benefit analysis and investment return appraisal, as well as the sequencing of interventions in corridor development.Footnote4 In this literature, corridor developments, as regional planning efforts, are presented as encouraging investment in infrastructure, minerals and agriculture.Footnote5 Proponents argue that linking transport infrastructure development with agriculture and mining means that key constraints, particularly of landlocked countries and regions, can be released, and growth potentials enhanced, with poverty reduction resulting in the longer term.Footnote6

Much of this commentary ignores the complex political dynamics behind such corridor developments, and very little attention has been focused on the political economy of corridors as they reshape landscapes, livelihoods and economies.Footnote7 While hyped as generators of economic growth and drivers of modernity in otherwise ‘backward’ and remote places, there are other implications.Footnote8 As demonstrations of state power in such borderland, frontier areas, corridors potentially bring control and order, suppressing alternative cross-border, often illicit, economies and quashing secessionist and opposition groups, as central states assert their power.Footnote9 As sites of potential accumulation, alliances between domestic elites, both local and national, with international corporate capital, finance institutions and international aid donors is much in evidence, suggesting new circuits of power and influence in such regions.Footnote10 With major investments in infrastructure – roads, sea and air ports, as well as mines, markets and large farms – the landscape is imagined to be fundamentally refashioned. Such plans may challenge previous livelihood systems, potentially undermining the mobility of pastoralists or the local production patterns and economic relations of smallholders, and altering the environment in the process.Footnote11

In this article – and the trio of special section articles by Chome, Gonçalves, and Sulle, all of which adopt different perspectives on political economyFootnote12 – we explore the political dimension of corridors, focusing in particular on the implications for commercial agricultural development as a core component. Taking a political economy lens to the revival of spatial planning and corridor development – particularly focusing on agricultural development dimensions – we explore the way corridor development is framed, the actors involved, the way power is exerted and reconfigured, and the winners and losers from such major developments. In sum, we examine the material consequences of such plans on the ground – and through which diverse patterns of accumulation, differentiation, negotiation and agricultural commercialisation emerge – as people anticipate, demonstrate or contest these high-modernist visions.

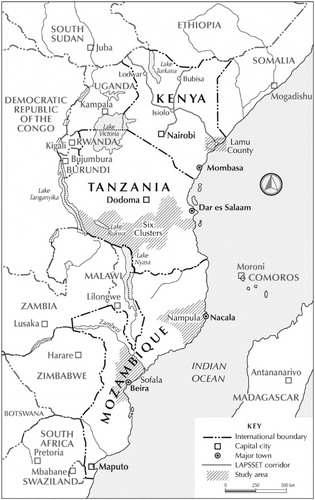

The rest of the article is organised as follows. Firstly, we briefly discuss the emergence of ‘corridors’ in development debates and their historical precursors on the African continent. Secondly, we introduce the cases from Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania (). Thirdly, we explore how agricultural development corridors are framed. In the latter, we contrast two visions of corridors, a linear, extractivist ‘tunnel’ model, involving a limited set of actors usually involved in enclave-based export production, with a more informal ‘network’ model that allows a wider range of actors to be included, and that emerges in a more haphazard way as a result of the existing of a corridor plan, even in the absence of significant investments. Fourthly, and in reflecting on some of the findings discussed in depth in the three case study articles in this special section, we then explore some of the outcomes, first in relation to patterns of accumulation and differentiation, and around the diverse pathways of agricultural commercialisation that potentially result from corridor development. We conclude with some reflections on the implications of our findings for debates about the development of commercial agriculture in eastern Africa.

The return of large-scale investments

Such high-profile interventions, aimed at transforming backward areas with a particular vision of ‘development’, are of course not new.Footnote13 From the colonial era onwards, major infrastructure developments have been central to state-building in Africa, and the assertion of state power over places and people, particularly in marginal border areas. The history of development in the continent is littered with such examples, including in the field of agriculture.Footnote14 Many have failed, and existed as expensive white elephants; others have continued with on-going state subsidy, while others have been reimagined, and repurposed through smallholder investments and other local capital interests.Footnote15 Across each of three cases presented in this special section, the precursors of these recent corridor developments are important to understand, as they provide the layered histories of development intervention on top of which new efforts are imposed.

An important question is why such large-scale investments have returned to dominate the agricultural development scene today? In debates about African agriculture, a long-term consensus that a smallholder-led green revolution was the best solution has been recently challenged.Footnote16 In this way, the conventional wisdom – for several decades, and with plenty of evidence to back it up – was that top-down, technocentric forms of commercialisation in agriculture (of crops or livestock) are unlikely to succeed, and instead efforts must be expended in supporting smallholder development.Footnote17 But today, in the context of an increasingly globalised agriculture, and consumer demands for cheap food, large-scale commercial agriculture, in the form of estates or plantations (sometimes with smallholder outgrower schemes) has been revived as a model for the first time in decades.Footnote18 Growth corridors are perhaps the most prominent example of this new trend. Why is this, given the long history of failure of large-scale commercial agricultural projects in Africa in achieving their stated objectives?

Across Africa, growth corridors are featured prominently as part of current donor-led plans, receiving significant attention and financial support.Footnote19 For example, they are promoted through the New Alliance for food security and nutrition launched at the 2012 G8 Summit at Camp David, the World Economic Forum, the African Development Bank, the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, among others. Additional donors from BRICS countries, often with stronger links to state-owned enterprises and domestic private companies, are also involved, with Brazil having interests in commercial agricultural development, especially in Mozambique, and China, particularly in infrastructure development across Africa.Footnote20

Projects are often conceived so as to deliver more than one type of infrastructure, and for more than one sector, providing additional business incentives to investors.Footnote21 This is because it has proven difficult to persuade investors to fund infrastructure purely for agriculture owing to the risks involved. For this reason, minerals extraction and agricultural development become tied together as part of corridor development, with an export-led mineral/agricultural commodity boom expected to follow. The latter is, for example, a prominent feature of the Lamu Port-South-Sudan Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor that begins in Kenya, and of the Beira and Nacala corridors in Mozambique, all of which seek to leverage physical transport infrastructure and mineral extraction so as to create value-chains that will bring smallholders (and pastoralists) in these previously marginalised regions closer to external markets.Footnote22 Following in this precedent, a strong narrative of comparative advantage in export growth, and competition in a globalised economy, frames the debate, with roads and ports opening up opportunities – and reducing costs – essential to making the once uneconomic enterprises competitive.Footnote23

Thus, large agro-business and food processing multinational companies, such as Vale, Oderbrecht, Mitsui, Cargill, Bunge and Archers Daniels Midland, amongst others, become involved, often with combined interests in infrastructure, mining and agriculture.Footnote24 They in turn see state-supported corridors as a route to reduce costs and risks of investment. A spatially-concentrated approach is also attractive for those companies seeking to aggregate supply and sell inputs. Thus, SABMiller, a major brewing company, sees corridor investments as a route to gain stable supplies of products from organised smallholders. In the same way, major input suppliers, such as Yara, identify corridors as areas for new markets for fertiliser, crop protection products, seeds and machinery.Footnote25

The modalities for delivering agricultural development, meanwhile, typically include the use of public–private partnerships, catalytic funding and support for value-chain and market development. For example, TransFarm Africa talk of the need to ‘tie smallholders into the stream of commerce’.Footnote26 On the other hand, the Seas of Change (a long-term applied research, innovation and exchange programme) value-chains initiative looked for ‘commercially viable’ farmers to support.Footnote27 While there is much rhetoric about ‘inclusive’ business models, public, private, even community ‘partnerships’, and ‘win-win’ outcomes for economic growth,Footnote28 these claims must be interrogated, asking, for example, who is central to the partnership, what power dynamics are at play, and what processes of exclusion result.

As a melting pot for alliances and interactions, corridor developments therefore become sites for intense discursive and political contests about development trajectories. These may be, for example, over the framing of the projects, between those who see opportunities for local economic regeneration, as clusters or hubs of economic activity, and those who emphasise the export dimension and an extractivist logic. Imaginaries of development, between high modernist framings and more locally-driven networked alternatives are played out, across actors, with multiple variants in different sites, reflecting particular positions, histories and on-going local struggles. Contests also occur over opportunities for accumulation, as alliances between external and domestic capital are forged with local and national political and business elites. For national politicians – from presidents downwards – such mega-projects are opportunities to demonstrate power and benevolence, asserting control; very useful political resource during election periods and when trying to quash rebellion and opposition in such areas.Footnote29 For donors and NGOs equally, having visible, flagship projects, demonstrating images of success, is always appealing,Footnote30 and of course, existing patterns and practices of livelihoods and economy may come into conflict with these grand, transformative visions, resulting in contestations by different actors, including anticipations of the promised, prosperous futures, as the cases discussed in this special section demonstrate.

A view of four corridors on Africa’s eastern seaboard

The cases that this article introduces and analyses are the LAPSSET Corridor; the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor in Tanzania, simply known as SAGCOT, and the Beira and Nacala Corridors in Mozambique. There are notable variations in the designs and outcomes of these corridors, as will be shown below, but the general trend is towards more informal ‘network’ models, even when the initial design, such as in the case of LAPSSET and Nacala corridors, envisioned a linear, extractivist ‘tunnel’ model. SAGCOT and Beira, on the other hand, started out as ‘network’ models – in SAGCOT, this happened by default, as it was not a single corridor designed at one moment, but a historically-layered set of interventions, while in Beira, the ‘network’ was a result of donor-funded outgrower and smallholder schemes. In addition, while corridors are seen as driving development in otherwise relatively underdeveloped areas in Kenya and Mozambique, SAGCOT in Tanzania was centred on a long-settled agricultural region, and seen as a route to boosting commercial agricultural development on the back of long-term investments in sugar and other agro-industries.

During the time of research and writing, the corridors were at different stages of development, and all had varying financial arrangements. As mentioned above, while the public-private partnership model is prominent across all the corridors, in practice, the sources of private capital and the nature of state engagement (of local and central governments) significantly varies. In LAPSSET, the central government is the main financier of the supporting transport infrastructure components, such as the new port at Lamu, whose continued construction has been supported almost entirely by Chinese loans. Also, the main economic rationale behind LAPSSET continues to be transportation of crude oil from the Turkana basin in Northern Kenya. While aid from the United Kingdom and capital from Western agribusinesses provide the main source of funding in Beira, Brazilian and Chinese capital is more important on the Nacala corridor, where mining is providing the main economic rationale. SAGCOT, which was designed and promoted by the regime of former President Jakaya Kikwete, brought together a host of global agribusiness capital linked together through the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition in Africa, with support from Western states through the G8. However, the development of SAGCOT since early 2019 has been complicated by the change of priorities by a new administration, headed by President John Magufuli, which has withdrawn its support of SAGCOT altogether (Sulle, this issue).

Despite these variations, the narratives that frame these corridor investments are all focused on ‘growth’, and in respect of agriculture, a discourse centred on generating a missed African ‘green revolution’. This is linked to boosting food production, creating ‘breadbasket’ regions, but also with agricultural export crops or livestock as central products.Footnote31

As mentioned above, in Mozambique and Kenya in particular, the anchor project – the investment that drives the economic incentives to invest, particularly in core transport infrastructure – is not agriculture, but mining or oil/gas extraction. In Tanzania, by contrast, commercial agriculture has been more central from the start. This is significant in the political economy of such investments, as alliances between international extractive industries and the state are often at the heart of corridor politics. International aid donors are involved too and, as shows above, a wide range of donors have been engaged.Footnote32 Their focus is usually more on the agricultural dimensions, often downplaying the extractivist origins of the corridor; although often with major companies from the donor country involved. The focus for aid donors is more on regional development, and trickle-down economic benefits for ‘the poor’, and involvement of smallholders through contract farming and other initiatives linked to ‘public-private partnerships’. In sum, across the three cases, there are a range of historical origins, different agroecological and social-political contexts and different mixes of investments and associated actors. Corridors are far from uniform even in their constructions as grand visions; and, as the cases show, the outcomes are extremely diverse too.

Table 1. Brief profiles of four corridors. Adapted from Rebecca Smalley. 2017. “Agricultural Growth Corridors on the Eastern Seaboard of Africa: An Overview.” APRA Working Paper 1.

Corridors: the panacea for agricultural growth and development?

Corridors are therefore very high-profile and expensive interventions, often central to state development plans, and requiring partnerships with private capital and finance, often with international origins. As they are sometimes envisaged as cross-border initiatives, they confront not only domestic politics, but regional, cross-national politics too. Plans for such corridors are often quintessentially ‘high modernist’ projects, with standardised, grid-like plan, framed by a ‘will to improve’ – to employ Tanya Li’s terms – by development donors and states, in line with a particular vision of progress.Footnote33 These styles of development in turn generate a style of ‘techno-politics’, where certain types of expertise and technological intervention are privileged, each with exclusionary characteristics.Footnote34 However, as James Ferguson has argued, this model of ‘seeing like a state’ is upset in the neoliberal world where ‘developmental states’ in Africa have less reach and traction and where companies establish territorialised enclaves.Footnote35 These have their own security and state-like features, as capital ‘hops’ between disparate sites where rule, order and capitalist accumulation can be assured.Footnote36

Yet, as the cases presented elsewhere in this special section show, in practice, neither a state-driven modernist plan nor enclave capitalism results. In Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania, local anticipations of the promised prosperous future; ‘demonstration fields’ that are turned into capital for future government and donor supported projects; and local contestations of the grand-vision for the commercialisation of agriculture; all promise to generate many hybrid forms, as different visions compete and converge. In this way, state plans for agricultural commercialisation within the imagined corridors – often presented as a vision of an extractivist ‘tunnel’, with limited connections to wider economies – frequently fall apart. The realities of rural Africa on the margins impinge, transforming economic prospects and forcing projects to morph into a new project more closely aligned with the interests of local capital. Enclaves in the form of large-scale farm investments can never fully isolate themselves and must articulate with other forms of local capitalism, politics and negotiation on the ground. Large estates thus very often seek to engage with outgrowers (smallholder farmers) as well as medium-scale farmers, accommodating local producers in the wider enterprises.Footnote37 As Sulle (this special section) shows for the case of sugar production in Tanzania, the challenges of reliance solely on an estate model has meant an increasing reliance on smallholder outgrowers, increasing the reach of the company on to outgrowers’ land indirectly, while also incorporating a great diversity of people into the dynamic of agricultural commercialisation promoted by the SAGCOT corridor.Footnote38

Corridors thus have elements of both state-led imposition, supported by grand plans, public finance, private capital and donor funding, and privatised corporate-led enclave developments, largely outside state influence, but yet are still contingent on local contexts and political negotiations.Footnote39 In particular, corridors must always articulate with endogenous processes of capital accumulation, and local elite interests may help transform a simple plan into something more complex, embedding externally-driven processes into local contexts.Footnote40 This more hybrid networked reality offers an interesting window for understanding agrarian change, the changing nature of rural investment and governance patterns in Africa. States, through alliances with private domestic and international capital, attempt to extend their developmental reach, and private companies, including those classically involved in enclave extractivism, aim to ensure ‘local content’, ‘social license’ and ‘linkages’ as part of business plans.Footnote41

A political economy of corridors is therefore about how contests over the framing of development intervention – influenced by a range of social and technical ‘imaginaries’ – results in diverse outcomes dependent on the configurations of local interests, as they unfold over time.Footnote42 It is not a simplistic story of state or corporate imposition that results in local dispossession and resistance.Footnote43 On the contrary, and as Chome (this section) shows, the ways in which capital and state power are deployed reconfigure processes of production of bureaucratic authority and citizen participation. Across all the cases, different actors are seen to benefit, including rural farmers, government bureaucrats, politicians and local business interests. The logics of capital, as commercialisation extend into the margins, results in the creation of new opportunities.

There are of course losers too. Speculative land enclosures, changing employment opportunities and project imposed restrictions emerge too. As Chome (this section) shows, the resulting competition for land and resources, as individuals and local groups compete to secure a place within LAPSSET’s promised future, has not only engendered an understanding of ethnic others as ‘immigrants’ or ‘guests’ within the corridor, but has fuelled what Borras and Franco have termed as ‘broad types of political conflicts’ within and between the state and social forces.Footnote44 The conflicts, as Chome shows, have created a complex social and political tapestry of inclusion and exclusion.Footnote45 Moreover, as Sulle (this section) illustrates, due to difficulties in accessing village lands in Tanzania, large-scale land-based investments, previously envisioned within SAGCOT’s plans, have not materialised, and those that exist have been linked with smallholder outgrowing schemes.Footnote46

Patronage, accumulation and social differentiation

The penetration of the state and capital into previously remote and marginalised areas inevitably results in significant reconfigurations in local political economies.Footnote47 But the processes of change are neither predictable nor inevitable. The interactions of capital with the state, and its intersections with local politics are always complex, and subject to contestation. The core questions for our study are central to any agrarian political economy analysis: who does what, who owns what, who gets what and what do they do with it?Footnote48 It is the intersection of these processes of accumulation, reproduction and differentiation with local politics and livelihoods that we are centrally interested in.

While corridors are promoted around a narrative of development, and trickle-down impacts of growth to the poor, past experiences have shown that these benefits have often not been forthcoming. Equally, such corridors are often assumed to be intervening on a blank slate, one where only backward, deprived and marginalised people exist, and so benefits are inevitable.Footnote49 Despite the narrative of transforming ‘idle’, ‘underutilised’ land into ‘modern’, ‘productive’ agriculture or mining enterprises, of course all these areas in the hinterlands of the new corridor transport infrastructure are already occupied and used.Footnote50 In all cases, vibrant local economies, with their own dynamics pre-exist such interventions, and in many cases, have been growing and prospering independently, as in the case of the growth of commercial livestock production in the pastoral hinterlands of the LAPSSET project in Kenya.Footnote51 As external capital confronts endogenous enterprise and associated interests, conflicts inevitably arise.

Not surprisingly, contests over land and resources become central, with disputes often fanning out into the wider national, sometimes international, politics. The high-profile nature of such investments also means that they sometimes become focal points for insurgent groups, militias and terrorist organisations, influencing the dynamics of conflict in the region. Equally, for the state, opening up frontier areas affords the ability to extend state control in such areas, undermining the economic and political base of opposition forces. Whether as part of confronting ‘terrorism’, as in Kenya’s struggle with Somalia-based violent Islamist organisation, Al-Shabaab, or quashing a regionally-associated, but powerful opposition as in Renamo in Mozambique, the economic transformation of such areas, and their incorporation under state control is a central part of the securitisation politics of corridors, sometimes giving rise to violence and the militarisation of these areas.Footnote52

How can we understand these complex dynamics across cases? As already discussed, there is a broad network of actors that comes together around corridors. These include corporate players, government officials (national and local), international/national capital and local (endogenous capital), other local elites and often relatively asset-rich, often male, farmers and livestock owners/traders able to engage in such markets. Corridors are spaces of social and political control, rooted in complex ethnic and political histories. They also have become sites for the exercise of power by state agencies in marginal areas – whether Mozambique Ports and Railways, or CFM and Agência Vale do Zambeze, or departments of the overly-centralised national administration in Kenya, and the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority (LCDA).

Regardless of the exact motivations in each case, the extension of capital into marginal areas is not straightforward. Despite the grand plans, in many cases the realisation on the ground has been limited. While building a road or rail line often initiates the corridor development, what happens next is less clear. Without feeder roads, the benefits of a major highway may be limited. An emphasis on freight trains for extracting minerals, for example, may exclude local passengers and their produce. And the type of follow-on land based investments – large farms and estates for example – often face problems of markets, labour, logistics and finance.Footnote53 Economic activity in the early phases therefore often emerge from ‘economies of anticipation’, whereby future benefits from land and investment are betted on through, for example, the appropriation and enclosure of land, the speculative investment in business ventures – a processing plant, a silo or a warehouse – and the assertion of rights, based on claims of indigeneity and ethnic territoriality. The latter, as mentioned above, has vividly intersected in Lamu along the proposed LAPSSET corridor, as illustrated by Chome (this section) as well as Gonçalves (this section) on the Beira and Nampula corridors of Mozambique, where the creation of NGO-supported projects, framed around women’s empowerment and involvement in commercial agriculture, has contributed to the active participation of a limited number of smallholders in ‘demonstration fields’ in anticipation of future government and donor supported projects.Footnote54

Based on both real economies and speculative anticipation therefore, corridors become spaces for the playing out of elite politics – between central government and party elites, business players of different sorts and local leaders, including traditional chiefs or government officials with control over land.Footnote55 With investor and aid money in the mix, the opportunities for patronage arrangements, corruption and deal-making are rife. Patterns of accumulation ‘from above’ are thus conditioned by these political relationships, with speculation on land and resources being made possible, as they become revalued through investment. In Lamu and Isiolo, both considered as important ‘nodes’ of the proposed LAPSSET corridor, public and communal land is being reconceptualised as private property through various (speculative) land buying and enclosure practices, coupled with rising demands for the formalisation of individual land claims, based on expectations of future returns from anticipated investments along the corridor.Footnote56 In this complex milieu, who benefits and who loses from corridor developments? Much depends on the terms of inclusion into new investments, the actors involved and the networks and alliances that emerge – and the politics of all this. Processes of incorporation are frequently mediated by long-run, historical antecedents, as previous conflicts over land and resources are replayed in a new setting. Ethnic politics is often central, as claims over resources are contested between ‘autochthones’ and a state promoting a national development project.Footnote57

As Sulle (this section) shows for Tanzania, the benefits of large investments may be spread thinly and captured by only certain groups. Those able to benefit, say from outgrower contracting arrangements for new sugar investments in the SAGCOT area, are often those with larger farm areas, where they can guarantee food production.Footnote58 Those without, must commute between sugar plots and other areas, undermining livelihood opportunities.Footnote59 Employment generated by such investments may benefit women, but may be increasingly insecure.Footnote60 Equally, in the pastoral areas of Kenya, those able to benefit from market and infrastructure developments are often male, larger herd owners (usually of large stock), and intermediary traders.Footnote61 ‘Making markets work for the poor’ is a neat slogan, but is often undermined by the realities of capital concentration, limits of access and control, with multiple gender, ethnic, age and class implications.

While the critique of corridors – and ‘land grabs’ more generally – has focused on the role of foreign investors, the role of local endogenous capital, with business and political elites, in facilitating such processes of enclosure and extraction has often been underplayed.Footnote62 For example, in pastoral areas, ‘indigenous agricultural commercialisation’ results in similar patterns of exclusion and small-scale grabs of land and resources, as part of a process of commodification and social differentiation in pastoral societies, interwoven and co-produced with state territorialisation and sedentarisation.Footnote63 These processes are more often than not, facilitated by grand-developmental schemes such as corridors.Footnote64

It is the coincidence of diverse logics of capital, emanating from different quarters, that is significant, and where these coincide to benefit certain groups, the prospects for ‘pro-poor’ outcomes diminish. Many development efforts are explicit about focusing on ‘emerging’ farmers, and those already connected to markets, allowing them to ‘step up’ in their livelihood trajectories.Footnote65 This accepts the dynamic of social differentiation, and selective accumulation, although rarely explicitly. This has consequences for who is able to benefit, with implications for class formation (as some step up, others may drop out, or move to become labourers rather than producers), gender dynamics (very often the terms of incorporation are skewed towards those who have existing power and assets, invariably men to the exclusion of women) and generational relations (as such dynamics often consolidate the power and control of an older generation, as they grow herds, increase land areas and so on).

As already discussed, the business configurations of investments can also have major impacts. Thus, large enclave investments in agriculture in the form of centrally-managed estates or plantations may offer limited opportunity for positive ‘spill-over’ or ‘linkage’ effects in the wider economy, especially if labour is hired from outside the region, as is often the case.Footnote66 By contrast, investments that explicitly include an outgrower element, whereby smallholder farmers produce on contract for a core estate or processing plant, then different production relations can emerge, even though the terms of incorporation and benefits will be differentiated.Footnote67 Similarly, in livestock systems, the siting of markets, their scale and links to abattoirs or live export facilities, makes a big difference to how producers engage with such commercialisation ventures.Footnote68

Understanding how capital, labour, land and social relations are configured in an investment is thus essential to understand what outcomes are possible. Across the cases we present and examine, we expect these to be quite different, and even different across particular agricultural investments within the broad spatial areas defined as a single corridor. Comparing and contrasting these will help elaborate how corridor and business model designs influence outcomes, and how tensions are played out between corridors as linear routes for the extraction of commodities for the exploitation of local economies, and as part of global value chains, or corridors as focal points – clusters, hubs, poles – for growth and local economic development and empowerment. With different logics of accumulation and different intersections of interests, across the cases we see contrasting alliances – between for example national/international capital and local endogenous capital or between the central and local state – and different forms of conflict and opposition emerging.

Pathways to agricultural commercialisation: diverse outcomes

As our studies across eastern Africa have shown, despite the hype and the considerable sums of money deployed, the grand visions of growth corridors are often not realised; or at least not in ways imagined by their architects. Inevitably, all have changed over time through diverse local, national and international political and economic contestations.

Most corridors envisage trans-national connections, and so planning and implementation processes become embroiled in regional politics, sometimes upsetting the visions of economic integration and regional development. Grand plans on maps may not be realised as politics intervenes. The oil pipeline route from Uganda has moved several times, as the highly anticipated one from South Sudan remains a distant reality, changing the economic drivers of the LAPSSET project as a result.Footnote69 The vision for the Beira corridor stretching from Mozambique into Zimbabwe has changed, as the Zimbabwe economy collapsed and the opposition group, Renamo, have returned to violence in parts of Mozambique.Footnote70 The Nacala corridor in Mozambique equally has shifted scope and direction many times, as different interests have been accommodated, changes in commodity prices affected the economics of agricultural enterprises, and protests against the ProSAVANA project – a joint Japan-Brazil-Mozambique initiative in the savannah zone of the Nacala corridor – increased.Footnote71

As Hagmann and Stepputat point out, despite their proposed function as facilitating trade, corridors also very often ‘concentrate friction’.Footnote72 This friction materialises in the form of checkpoints, borders, taxation and bureaucratic procedures, transport congestion, and political and sometimes violent conflicts.Footnote73 This means that the performance of authority, by the state and other hybrid constellations, is focused in such areas, resulting in multiple sources of tension, negotiation and competition.Footnote74

Forms of resistance, and the alliances that are generated both for and against such corridors, therefore potentially offer important insights into the political economy of agricultural investment and development. Contentious local politics intersect with the wider politics of corridor development, resulting in frictions between national alliances and local demands.Footnote75 State- and capital-led visions come up against ‘vernacular securities’ rooted in local authority structures and local histories and tensions around the role of the state in the rural margins. By looking both at local mobilisations and resistances, as well as the national political dynamics that drive such investments, the everyday politics of corridors can be exposed.

This is less neat than the grand plans suggest, or even what the opposition narratives against corridors propose. Thus, for example, in the Nacala corridor in Mozambique, the site of the much contested ProSAVANA project, protests against the scheme have resulted in significant changes in plans, even before implementation got properly underway.Footnote76 In the proposed LAPSSET corridor, Chome (this section) shows how increased competition over land and resources, and other related forms of conflict, has preceded the laying down of the formal infrastructure.Footnote77 Cases are reported where beacons demarcating routes and plots have been moved or disappeared, where people have started establishing rights over land along the corridor, where old territorial, and ethnically-defined institutions have been revived to assert claims, and where pastoralist raiding has intensified as different groups jostle for position in the expectation of benefits, or to protect themselves from the effects of enclosure and potential marginalisation.Footnote78

Despite changes in plans and implementation in each case, the corridor investments are nevertheless having significant impacts on patterns of agricultural investment and pathways of commercialisation across eastern Africa. This may occur through investments in particular agricultural initiatives, ranging from the establishment of estates/plantations, the creation of block farms and cooperative groups, to contract farming arrangements, with or without nucleus estates, or through infrastructure development, including roads and rail that change market opportunities and relations. Yet, as the articles in this special section show, these results are not necessarily as planned; new actors get involved, new networks are created, older ones entrenched or dismantled, and new opportunities arise. The terms of inclusion in the corridor – and its construction by people and artefacts – are always contested.

Conclusion

A political economy approach to corridors, we argue, is essential if we are to get beyond the standard, and limited, emphasis on economic and implementation questions, where failures are attributed to inappropriate incentives or lack of ‘political will’. As competing interests interact in a particular area, defined as a corridor, the resulting outcomes for different groups of people is inevitably complex, and context-specific. Yet a study of corridors – and their agricultural dimensions in particular – does offer, we argue, the potential to challenge assumptions about the linearity and predictability of agricultural commercialisation in Africa.

A number of questions emerge for exploring the political economy of agricultural growth corridors along the eastern seaboard of Africa. These go beyond the standard focus on the economics of the investments, and the practicalities of corridor implementation. Instead, a political economy lens allows us to explore how such investments are imagined, and are co-constituted with states and elite politics at multiple levels. It allows us to examine how spatial imaginaries are imposed but also re-envisioned within lived-in landscapes and economies. It also allows us to see what happens when such visions collide with local realities, and what new practices and resistances – overt and hidden – emerge to contest pathways of development.

In the articles of this section we take different approaches to political economy. Each article asks what happens when the grand visions of corridors ‘hit the ground’, often in situations when there are not many tangible features of ‘a corridor’. Corridor discourses and imaginaries though do have material effects as new networks emerge, which disrupt and challenge a simple linear, tunnel model. What these different forms take is illustrated through examples from all three countries. The article on SAGCOT in Tanzania focuses on contestations – especially over land and market opportunities – and the types of resistances and accommodations that are reached between interest groups including state-capital alliances and diverse groups of local people on the ground, with different opportunities for accumulation resulting. The article on LAPSSET in Kenya focuses more on what happens as the promises of corridor development unfold in a particular place, and the diverse ‘economies of anticipation’ that are articulated by different groups – from farmers to civil society groups to politicians – as the terms of inclusion are negotiated even in advance of any big investments. The article on Nacala and Beira corridors in Mozambique looks at the political economies of often mundane, ordinary everyday practice, focusing on the ‘demonstration fields’ as corridors are performed through alliances, projects, infrastructure investments and agricultural fairs. Through these processes, corridors are constructed and enacted, mediated by project officers from NGOs, state extension agents and others, leading to very different results to the grand plans and visions.

Emphasising the diverse politics and practices of corridor-making – and the complex articulations with states, capital and local communities, all articles focus attention on the classic questions of political economy – who owns what, who gains what and what they do with it. Through different lenses, the focuses remain on the processes of differentiation that result, outlining of unexpected winners and losers. This, in turn points to a new dynamic of accumulation resulting from corridors, and their imaginaries, as new forms of capital intervene (or are expected to) in previously marginal agrarian and pastoral settings.

As we have discussed, in all cases, the grand modernist visions are disrupted, and instead diverse, contingent and uncertain outcomes result. This analysis reveals much about how capital, states and local political and economic processes intersect in previously marginal areas and in processes of agricultural commercialisation in an era and context where both state capacity and global capital and finance have their limits.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lídia Cabral and Jeremy Lind for insightful initial reviews, and Rebecca Smalley for her substantial background work for the project which this paper draws on. Thanks also to the excellent comments from the anonymous journal reviewers. We acknowledge funding from Department for International Development (DfID) through the Agricultural Policy Research in Africa (APRA), our field research assistants, and John Hall for preparing the map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See, Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

2 See, Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations.”

3 Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata, Africa’s Land Rush.

4 See for example, ASI (Adam Smith International), “Integrated Resource Corridors Initiative: Scoping & Business Plan.” http://www.adamsmithinternational.com/documents/resource-uploads/IRCI_Scoping_Report_Business_Plan.pdf; AfDB, “Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA).” http://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/programme-for-infrastructure-development-in-africa-pida/; ACB (African Centre for Biodiversity), “Agricultural Investment Activities in Beira Corridor, Mozambique: Threats and Opportunities for Small-Scale Farmers.” http://acbio.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Mozambique-2015-report-full.pdf; AgDevCo, “BAGC Investment Blueprint.” http://www.agdevco.com/uploads/reports/BAGC_Investment_Blueprint_rpt19.pdf.

5 Weng et al., “Mineral Industries”; Hansen et al., “The Economics and Politics of Local Content”; Byiers, Molina, and Engel, “Agricultural Growth Corridors: Mapping Potential Research Gaps on Impact, Implementation and Institutions.” http://ispc.cgiar.org/sites/default/files/ISPC_StrategyTrends_DevelopmentCorridors.pdf.

6 Gollin and Rogerson, “Productivity”; Dorosh et al., “Crop Production”.

7 Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

8 See for example, Regassa and Korf, “Post-Imperial Statecraft”.

9 See for example, Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations”; Little et al., “Formal or Informal, Legal or Illegal”.

10 See, Hagmann and Stepputat, “Corridors of Trade and Power”; Bergius, “Expanding the Corporate Food Regime”; Ouma, “From Financialization to Operations”.

11 Laurance et al., “Estimating the Environmental Costs”; Sulle, “Land Grabbing”.

12 See, Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”; Gonçalves, “Agricultural Corridors”; Sulle, “Bureaucrats, Investors, and Smallholders”.

13 Fergusson, The Anti-Politics Machine; Scott, Seeing Like a State.

14 Fergusson, The Anti-Politics Machine.

15 See for example, Robinson and Torvik, “White Elephants”.

16 Collier and Dercon, “African Agriculture”.

17 Hazell et al., “The Future of Small Farms”.

18 Hall, , Scoones, and Tsikata, “Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming”; Smalley, Plantations, Contract Farming and Commercial Farming Areas in Africa.

19 Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

20 See for example, Amanor and Chichava, “South-South Cooperation”; Scoones et al., “A New Politics of Development Cooperation?”

21 Warner, Kahan, and Lehel, “Market-Oriented”.

22 See, Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”; Gonçalves, “Agricultural Corridors”.

23 Gollin and Rogerson, “Productivity”; Wood and Mayer, “Africa’s Export Structure”.

24 Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

25 Bergius, “Expanding the Corporate Food Regime”; Ouma, “From Financialization to Operations”.

26 Kuhlmann, Sechler, and Guinan, Africa’s Development Corridors as Pathways.

27 See for example, Woodhill, J., J. Guijt, L. Wegner, and M. Sopov. “From Islands of Success to Seas of Change: A Report on Scaling Inclusive Agri-Food Markets.” http://www.inclusivebusinesshub.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/05/SOC2012report.pdf.

28 See for example, International Food Policy Research Institute. “Innovation for Inclusive Value-Chain Development: Successes and Challenges.” http://www.ifpri.org/publication/innovation-inclusive-value-chain-development-successes-and-challenges.

29 See, Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”.

30 See, Gonçalves, “Agricultural Corridors”.

31 Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

32 Ibid.

33 See, Scott, Seeing Like a State; Li, The Will to Improve.

34 Mitchell, Rule of Experts; Fergusson, The Anti-Politics Machine.

35 Fergusson, Seeing Like an Oil Company.

36 Ibid.

37 See for example, Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata, “Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming”.

38 Sulle, “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders”.

39 Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations”.

40 Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger, “Re-Spacing African Drylands”.

41 Buur, “The Development of Natural Resource Linkages”; Hansen et al., “The Economics and Politics of Local Content”.

42 For the social and technical imaginaries that influence the framing of development, see, Hanse and Stepputat, States of Imagination; Taylor, Modern Social; Jasanoff, States of Knowledge.

43 For an overview analysis on dispossession and resistance, see for example, Araghi and Karides, “Land Dispossession”; Oliver-Smith, Defying Displacement.

44 See, Borras and Franco, “Global Land Grabbing”.

45 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”.

46 Sulle, “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders”.

47 Das and Poole, Anthropology in the Margins.

48 See, Bernstein, Class Dynamics.

49 See, Ragassa and Korf, “Post-Imperial Statecraft”.

50 See for example, Enns, “Infrastructure Projects”; Buffavand, “The Land Does Not Like Them”.

51 See for example, Catley, Lind, and Scoones, “The Futures of Pastoralism”.

52 See for example, Watkins, “LAPSSET”.

53 See, West and Haug, “The Vulnerability”.

54 Gonçalves, “Agricultural Corridors”.

55 Sulle, “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders”.

56 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”; Elliot, “Planning”.

57 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging.”

58 Sulle, “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders”.

59 Ibid.

60 See for example, Dancer and Sulle, Gender Implications.

61 Catley, Lind, and Scoones, Pastoralism and Development.

62 See for example, White et al., “The New Enclosures”; Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata, Africa’s Land Rush; Pedersen and Buur, “Beyond the Grabbing”.

63 Korf, Hagmann, and Emmenegger, “Re-Spacing African Drylands”.

64 See for example, Greiner, “Land-Use Change”.

65 Dorward, A., S. Anderson, Y. Nava, J. Pattison, R. Paz, J. Rushton, and E. Sanchez Vera, “Hanging In, Stepping Up and Stepping Out: Livelihood Aspirations and Strategies of the Poor.” https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/6163/1/HangingInDIP.pdf.

66 Smalley, Plantations, Contract Farming and Commercial Farming Areas in Africa.

67 Hall, Scoones, and Tsikata, “Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming”.

68 See, Catley, Lind, and Scoones, “The Futures of Pastoralism”.

69 See, Browne, “LAPSSET”.

70 Morier-Genoud, “Proto-guerre et négociations”.

71 Shankland and Gonçalves, “Imagining Agricultural Development”.

72 Hagmann and Stepputat, “Corridors of Trade and Power”, 32.

73 See for example, Tsing, Friction.

74 Das and Poole, Anthropology in the Margins.

75 See for example, Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”.

76 Shankland and Gonçalves, “Imagining Agricultural Development”.

77 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”.

78 Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations”; Greiner, “Land-Use Change”; Elliot, “Planning”.

Bibliography

- Amanor, Kojo, and Sergio Chichava. “South-South Cooperation, Agribusiness, and African Agricultural Development: Brazil and China in Ghana and Mozambique.” World Development. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.021.

- Araghi, Farshad, and Marina Karides. “Land Dispossession and Global Crisis: Introduction to the Special Section of Land Rights in the World System.” Journal of World-Systems Research 18, no. 1 (2012): 1–5. doi: 10.5195/jwsr.2012.487

- Bergius, Mikael. “Expanding the Corporate Food Regime in Africa Through Agricultural Growth Corridors: The Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania. Current and Potential Implications for Rural Households.” Master’s thesis., Norwegian University of Life Sciences, 2014.

- Bernstein, Henry. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change. Boulder, CO: Lynne Publishers, 2010.

- Borras, Saturnino M. Jr., and Jennifer Franco. “Global Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below’.” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 9 (2013): 1723–1747. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2013.843845

- Browne, Adrian. LAPSSET: The History and Politics of an Eastern African Megaproject. London: Rift Valley Institute, 2015.

- Buffavand, Lucie. “‘The Land Does Not Like Them’: Contesting Dispossession in Cosmological Terms in Mela, South-West Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 476–493. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266194

- Buur, L. “The Development of Natural Resource Linkages in Mozambique: The Ruling Elite Capture of New Economic Opportunities.” Danish Institute for International Studies Working Paper 3 (2014): 1–24.

- Catley, Andy, Jeremy Lind, and Ian Scoones. “The Futures of Pastoralism in the Horn of Africa: Pathways of Growth and Change.” Revue scientifique et technique 35, no. 2 (2016): 389–403. doi: 10.20506/rst.35.2.2524

- Catley, Andy, Jeremy Lind, and Ian Scoones. Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Chome, Ngala. “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging: Negotiating Change and Anticipating LAPSSET in Kenya’s Lamu County.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020).

- Collier, Paul, and Stefan Dercon. “African Agriculture in 50 Years: Smallholders in a Rapidly Changing World?” World Development 63 (2014): 92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.001

- Das, Veena, and Deborah Poole. Anthropology in the Margins of the State. Oxford: James Currey, 2004.

- Dorosh, Paul, Hyoung-Gun Wang, Liang You, and Emily Schmidt. “Crop Production and Road Connectivity in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Spatial Analysis.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no 5358 (2010): 1–34.

- Elliott, Hannah. “Planning, Property and Plots at the Gateway to Kenya’s ‘New Frontier’.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 511–529. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266196

- Enns, Charis. “Infrastructure Projects and Rural Politics in Northern Kenya: The Use of Divergent Expertise to Negotiate the Terms of Land Deals for Transport Infrastructure.” Journal of Peasant Studies. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1377185.

- Ferguson, James. The Anti-Politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho, Minneapolis. London: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

- Ferguson, James. “Seeing Like an Oil Company: Space, Security, and Global Capital in Neoliberal Africa.” American Anthropologist 107, no. 3 (2005): 377–382. doi: 10.1525/aa.2005.107.3.377

- Gollin, Douglas, and Richard Rogerson. “Productivity, Transport Costs and Subsistence Agriculture.” Journal of Development Economics 107, no. C (2014): 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.10.007

- Gonçalves, Euclides. “Agricultural corridors as ‘demonstration fields’: infrastructure, fairs and associations along the Beira and Nacala corridors of Mozambique.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020).

- Greiner, Clemens. “Land-Use Change, Territorial Restructuring, and Economies of Anticipation in Dryland Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 530–547. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266197

- Hagmann, Tobias, and Finn Stepputat. “Corridors of Trade and Power: Economy and State Formation in Somali East Africa.” Danish Institute for International Studies Working Paper 8 (2016): 1–37.

- Hall, Ruth, Ian Scoones, and Dzodzi Tsikata. Africa’s Land Rush: Rural Livelihoods and Agrarian Change. London: James Currey, 2015.

- Hall, Ruth, Ian Scoones, and Dzodzi Tsikata. “Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming in Africa: Agricultural Commercialisation and Implications for Agrarian Change.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44, no. 3 (2017): 515–537. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2016.1263187

- Hansen, Michael W., Lars Buur, Anne M. Kjær, and Ole Therkildsen. “The Economics and Politics of Local Content in African Extractives: Lessons from Tanzania, Uganda and Mozambique.” Forum for Development Studies 43, no. 2 (2016): 201–228. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2015.1089319

- Hansen, Thomas B., and Finn Stepputat. States of Imagination: Ethnographic Explorations of the Postcolonial State. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.

- Hazell, Peter B. R., Colin Poulton, Steve Wiggins, and Andrew Dorward. “The Future of Small Farms for Poverty Reduction and Growth.” International Food Policy Research Institute Policy Brief 75 (2007): 1–2.

- Hildyard, Nicholas. Licensed Larceny: Infrastructure, Financial Extraction and the Global South. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Korf, Benedict, Tobias Hagmann, and Rony Emmenegger. “Re-Spacing African Drylands: Territorialisation, Sedentarization and Indigenous Commodification in the Ethiopian Pastoral Frontier.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42, no. 5 (2015): 881–901. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2015.1006628

- Kuhlmann, Katrin, Susan Sechler, and Joe Guinan. Africa’s Development Corridors as Pathways to Agricultural Development: Regional Economic Integration and Food Security in Africa. Washington, DC: TransFarm Africa, Aspen Institute, 2011.

- Laurance, William F., S. Sloan, Lingfei Weng, and Jeffrey Sayer. “Estimating the Environmental Costs of Africa’s Massive “Development Corridors”.” Current Biology 25, no. 24 (2015): 3202–3208. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.046

- Li, Tanya M. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development and the Practice of Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007.

- Little, Peter D., Waktole Tiki, and Negassa Debsu. “Formal or Informal, Legal or Illegal: The Ambiguous Nature of Cross-Border Livestock Trade in the Horn of Africa.” Journal of Borderlands Studies 30, no. 3 (2015): 405–421. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2015.1068206

- Mitchell, Timothy. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-Politics, Modernity. Berkley: University of California Press, 2002.

- Morier-Genoud, Eric. “Proto-guerre et négociations: Le Mozambique en crise, 2013–2016.” Politique Africaine 145, no. 1 (2017): 153–175. doi: 10.3917/polaf.145.0153

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199

- Oliver-Smith, Antony. Defying Displacement: Grassroots Resistance and the Critique of Development. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010.

- Ouma, Stefan. “From Financialization to Operations of Capital: Historicizing and Disentangling the Finance-Farmland Nexus.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 72 (2016): 82–93.

- Pedersen, Rasmus, and Lars Buur. “Beyond Land Grabbing: Old Morals and New Perspectives on Contemporary Investments.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 72 (2016): 77–81.

- Regassa, Asebe, and Benedikt Korf. “Post-Imperial Statecraft: High-Modernism and the Politics of Land Dispossession in Ethiopia’s Pastoral Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018): 613–631. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2018.1517854

- Robinson, James, and Ragna Torvik. “White Elephants.” Journal of Public Economics 89, no. 2 (2005): 197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.05.004

- Scoones, Ian, Kojo Amanor, Arilson Favareto, and Qi Gubo. “A New Politics of Development Cooperation? Chinese and Brazilian Engagements in African Agriculture.” World Development 81 (2016): 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.11.020

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Shankland, Alex, and Euclides Gonçalves. “Imagining Agricultural Development in South–South Cooperation: the Contestation and Transformation of ProSAVANA.” World Development 81 (2016): 35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.002

- Smalley, Rebecca. “Agricultural Growth Corridors on the Eastern Seaboard of Africa: An Overview.” Agricultural Policy Research in Africa Working Paper 1 (2017): 1–34.

- Sulle, Emmanuel. “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders: Contesting Land Rights and Agro-Commercialisation in the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020).

- Sulle, Emmanuel. “Land Grabbing and Commercialization Duality: Insights from Tanzania’s Agricultural Transformation Agenda.” Italian Journal on African and Middle Eastern Studies 17, no. 3 (2016): 109–128.

- Sulle, Emmanuel. “Social Differentiation and the Politics of Land: Sugar Cane Outgrowing in Kilombero, Tanzania.” Journal of Southern African Studies 43, no. 3 (2017): 517–533. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2016.1215171

- Taylor, Charles. Modern Social Imaginaries. London: Duke University Press, 2004.

- Tsing, Anna L. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Warner, Michael, David Kahan, and Szilvia Lehel. “Market-Oriented Agricultural Infrastructure: Appraisal of Public-Private Partnerships.” Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Occasional Paper 23 (2008): 1–151.

- Watkins, Eric. “LAPSSET: Terrorism in the Pipeline.” Counter-Terrorist Trends and Analyses 7, no. 8 (2015): 4–9.

- Weng, Lingfei, Agni K. Boedhihartono, Paul H. G. M. Dirks, John Dixon, Mohamed I. Lubis, and Jeffrey A. Sayer. “Mineral Industries, Growth Corridors and Agricultural Development in Africa.” Global Food Security 2, no. 3 (2013): 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2013.07.003

- West, Jennifer, and Ruth Haug. “The Vulnerability and Resilience of Smallholder-Inclusive Agricultural Investments in Tanzania.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 11, no. 4 (2017): 670–691. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2017.1367994

- White, Ben, Saturino M. Borras, Jr., Ruth Hall, Ian Scoones, and Wendy Wolford. “The New Enclosures: Critical Perspectives on Corporate Land Deals.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3-4 (2012): 619–647. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2012.691879

- Whitfield, Lindsay, and Lars Buur. “The Politics of Industrial Policy: Ruling Elites and Their Alliances.” Third World Quarterly 35, no. 1 (2014): 126–144. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2014.868991

- Wood, Adrian, and Jorg Mayer. “Africa’s Export Structure in a Comparative Perspective.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 25, no. 3 (2001): 369–394. doi: 10.1093/cje/25.3.369