ABSTRACT

In the past decade, the Mozambican government has been mobilizing international capital to build and renovate transport infrastructure in the central and northern areas of the country, with the aim of creating agricultural corridors. Based on field research conducted in two districts along the Beira and Nacala corridors, I examine those occasions when international capital and national agricultural policy meet smallholders in the implementation of agricultural projects. This article offers a performative analysis of the constitution of agricultural corridors. I argue that agricultural corridors emerge on those occasions when international funders and investors, national elites, local bureaucrats and smallholders overstate the success of agricultural projects and constitute what I have termed ‘demonstration fields’. Regardless of the implementation of blueprints, agricultural corridors gain spatial and temporal materiality from the performance of presenting agricultural projects as successful, such as at the unveiling of agro-related infrastructure, at agricultural fairs and on occasions involving smallholders’ associations.

In Nhamatanda, a district along the Beira corridor of Mozambique, Bernardo Augusto, a public extension officer, explained to me why there was a concentration of agricultural projects in his district – and therefore more visits by a host of governmental and non-governmental agencies – by asserting that ‘here, we have a lot of visits because we are at the corridor.’Footnote1 Augusto continued: ‘Our bosses do not like to go to areas of difficult access … […] The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development wants projects close to the road.’Footnote2 Augusto also explained that a host of private and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as PANNAR Seed, and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (known as CIMMYT), ‘also wanted to be close to the corridor’, and that ‘people who live in the interior, further away from the corridor, often do not have fields to show even if there is a great agricultural potential there.’Footnote3 Augusto’s observations are based on over a decade of field experience as an extension officer for government and donor-promoted agricultural projects in Nhamatanda – a district along the Beira corridor. They capture the views and experiences of local technicians and officers who work in the implementation of agricultural projects in Nhamatanda, but also in Ribáuè district along the Nacala corridor. In addition, the remarks illustrate the important link in Mozambique between the presence of transport and agro-based infrastructure and the exhibition of agricultural productivity, where agricultural projects are concentrated in areas closer to major road or rail networks (such as in Nhamatanda and Ribáuè). These areas are favoured because they are easily accessible to visiting ‘bosses’, i.e. investors, government officials and officers representing non-governmental organisations, most of whom are based mainly in Maputo, the country’s capital city, or in provincial capital cities such as Beira and Nampula.

A body of recent scholarship has highlighted the contentious, messy and erratic nature of agricultural corridors.Footnote4 Analysis of the planning, implementation and effects of the agricultural corridors suggest that they often generate anxiety over land, and potential environmental impacts, and reconfigure power dynamics between international capital, local elites, bureaucrats and smallholders.Footnote5

This article offers an analysis that recognizes the dramaturgical dimension of seemingly disparate agro-related events. It builds on a body of literature that highlights the importance of the performance of success in development projects. By focusing on the practices of international investors, national elites, local bureaucrats and project beneficiaries, researchers have suggested that, in order to attract capital, selected regions for development projects ‘must dramatize their potential as places for investment,’Footnote6 carefully selecting project participants who will make compromises so as to avert ‘failure, virtually guaranteeing that the programme will be declared a success when the time comes for evaluation.’Footnote7 These performances of success, at times, ‘undermine the project’s stated objectives’,Footnote8 but always require the participation of beneficiaries in order to be effective.Footnote9

In this paper I focus on the unveiling of agro-related infrastructures, fairs and smallholders’ associations to examine those occasions when international funders and investors, national elites, local bureaucrats and smallholders overstate the success of agricultural projects and constitute what I have termed ‘demonstration fields’. I give examples of how the performance of an agricultural project’s success is key to the spatial and temporal materialization of agricultural corridors, regardless of the implementation of the respective blueprints.

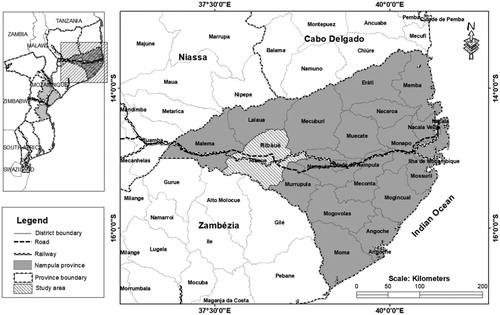

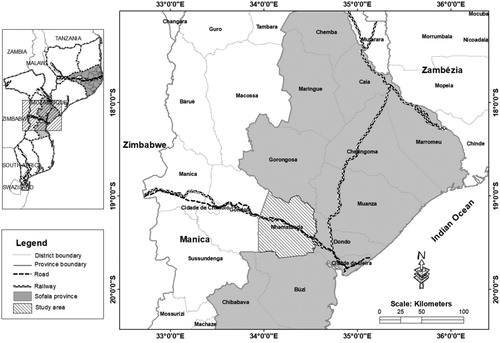

The data presented here is based on three periods of field research conducted in the Nhamatanda and Ribáuè districts, located along the Beira and Nacala corridors, respectively ( and ). These districts are crossed by national road and rail infrastructures that link areas in the hinterland to the sea, facilitating the import and export of goods. Nhamatanda and Ribáuè are also considered to have great agricultural potential and have been granted the status of ‘breadbasket’ districts within the provinces where they are located. During the months of March, July and August of 2018, I conducted field observations and 58 interviews with members of smallholder associations, extension officers, activists, and government representatives at provincial and district level.

The article begins by outlining the Beira and Nacala corridors with a view to foregrounding the entanglements of infrastructure development and agricultural projects that have historically constituted the corridors of Beira and Nacala. It then turns to three cases drawn from the districts of Nhamatanda and Ribáuè to highlight those moments when the unveiling of agro-infrastructure becomes a special occasion for the performance of project success. In the following section, the article similarly draws on two cases of smallholder associations along both corridors, to discuss how smallholder entrepreneurial models are used to project an image of increased agricultural productivity and commercialization. Before concluding, I put in perspective the discussions of the two sets of cases to highlight how ‘demonstration fields’ are constituted on those occasions when multiple actors who have individual and group interests participate in the performance of project success.

Corridor logics in Beira and Nacala

The Beira and Nacala corridors were built during the colonial periodFootnote10 to transport goods from the sea to the hinterland countries, namely present-day Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe.Footnote11 Driven by comparisons (and similarities) between the regions traversed by the Beira and Nacala corridors and the Brazilian Cerrado – a vast tropical savannah ecoregion of Brazil – the past two decades have seen government prioritizing investments in the Beira and Nacala corridors with the aim of boosting agricultural production.Footnote12 This interest in corridor development is also a result of an emerging paradigm in which international capital has partnered with African governments to pursue a number of spatial development initiatives.Footnote13 Around the cities of Beira and Nacala, ‘Special Economic Zones’ have been established, and the Mozambican government is planning to create further such zones dedicated to agriculture along both corridors.Footnote14 At the same time, international capital is building cash-oriented agricultural production on the basis of the former colonial economy in the region.Footnote15 For example, in the Nacala corridor, commercial agriculture has relied on foreign capital through large companies such as Mozambique Leaf Tobacco and Olam Mozambique, but also through medium-scale farming companies such as Agribusiness in Ribáuè, Matanuska in Monapo, alongside Zimbabwean, South African, Indian and Chinese investors.Footnote16

Agricultural production has been organized on the basis of agricultural zoning, under which value chains of certain products such as soya and cassava are to be developed.Footnote17 Taking into account the existing agricultural research infrastructure, the Mozambican Strategic Plan for Agricultural Development lists in its aims the ‘promotion and development of value chains for agricultural products in the corridors of Pemba-Lichinga, Nacala, Beira, Limpopo, Maputo and Zambeze Vale.’Footnote18 Investment in mechanization is identified as helping to improve productivity, while the construction of grain storage silos and storehouses is seen to help establish a commercialization network. Along the corridors, this approach to agricultural development is materialized in a number of national and international agricultural development projects some of which are connected to the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor (BAGC), in the Beira Corridor, and ProSAVANA in the Nacala Corridor.

Set up in 2010, BAGC was conceived with the objective of catalyzing ‘private sector investment, integrate smallholder farmers into commercial value chains and increase economies of scale.’Footnote19 The initiative is based on a public-private partnership model, with a coordinating secretariat tasked with developing 190,000 ha for commercial production in the provinces of Tete, Sofala and Manica, through irrigation and restructuring into livestock ranches. The model is based on a distinction between smallholder farmers on irrigated plots (5–50 ha), medium-sized farms (300–3,000 ha) and large estates (over 10,000 ha) for livestock and rice, field crops and horticulture.Footnote20

BAGC is a partnership between the government of Mozambique, private investors, farmer organizations and international agencies.Footnote21 Its overall aim is to provide a focus for increased commercial investment in agribusiness along the entire value chain in agro-based infrastructure, farming and processing, input supply chains (fertiliser, seeds etc.) and access to markets (storage, wholesale markets etc.). ‘Clustering’ of agribusinesses within the corridor should reduce costs, improve access to inputs and markets and therefore create a competitive, profitable and rapidly growing agricultural sector.Footnote22

The recent history of the Nacala Corridor dates back to the mid-2000s, with the planned rehabilitation of the Moatize-Nacala railway line passing through the Republic of Malawi, and additional gains to come from the transportation of imports, in particular fuel and medicine, coming from Europe and Asia into the landlocked country.Footnote23 The main attraction however, was the very deep waters of the port of Nacala, which could simultaneously provide a shorter and cheaper alternative to the transportation of coal from Tete province to the Beira harbour. As in the Beira corridor, the Mozambican government sought to maximize the transport services with the agricultural potential of the area, and develop agricultural value chains in the area associated with agricultural research.Footnote24 For this, it developed ProSAVANA, a Mozambique-Brazil-Japan Cooperation Programme for the Agricultural Development of the Savannah of Mozambique. This, and the officially published version of the Master Plan consists of three components: ‘Extension and models’, a component for smallholder inclusion and engagement; ‘Research and technology transfer’; and Support for the Agricultural Development Master Plan, which is aimed at engaging private investors in the Nacala Corridor Region.Footnote25

While the government tentatively began the implementation of the research component of ProSAVANA, a draft version of the ProSAVANA Master Plan projecting the use of a total of 14 million ha of land across 19 districts in the provinces of Nampula, Niassa and Zambezia in Northern Mozambique was leaked in 2013 and subsequently the programme fell under the scrutiny of a coalition of national and international civil society organizations.Footnote26 The declared intention of focusing on market-oriented agriculture through regional clusters and value chains to produce commodities for domestic consumption and export to markets in Africa and Asia generated so much anxiety over land in a short period that a ‘No to ProSAVANA’ campaign soon developed.Footnote27

Key actors in the Nacala corridor include the Brazilian mining company Vale S.A and the Mozambican public enterprise Portos e Caminhos de Ferro, or CFM. In early 2017, the Japanese conglomerate Mitsui bought 50% of the corridor shares from Vale S.A.Footnote28 Additional Japanese investments in the corridor came through the Japan International Cooperation Agency, which invested about US$530 million in rehabilitation of the Nampula-Cuamba road.Footnote29 Smalley notes that ‘a large number of companies and joint ventures have acquired thousands of hectares of land in the Nacala region,’Footnote30 turning them into key actors in the corridor, whether or not they are formally connected to ProSAVANA.Footnote31

While agricultural corridors are by nature long-term development plans, both corridors have faced significant challenges in the initial stages. The blueprint-designed vision of interlinked corridor agricultural activities, to stretch from the cities of Beira and Nacala on the Indian Ocean ports, covering a series of districts up to the countries of the hinterland (Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi), are yet to be materialized. For example, in relation to the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor, Kaarhus noted that

after Yara’s withdrawal as a lead partner in BAGC, the geographical centre of the initiative shifted from the port of Beira to the upland province of Manica and its capital Chimoio. Most of the ‘pilots’ that received funding from the Catalytic Fund were also located in Manica province. They were small- and medium-scale agribusinesses, with BAGC entering as one among several sources of funding and support. The pilots were involved in various forms of agricultural production, including seed multiplication and wild honey collection, and small-scale soya, goats and pig-meat processing. Only four of the agribusinesses would eventually operate in the value chains identified in the BAGC blueprint.Footnote32

We still lack infrastructure, roads, storehouses and we need to organize smallholders into associations … the truth is that the EN6 road has little impact for smallholders. We need tertiary roads. Seventy percent of the cost of some products is due to transport costs in the poor road conditions we have.Footnote33

Additional challenges to the implementation of agricultural corridors are related to national and local politics. On the one hand, the armed confrontation between government forces and the armed branch of the major political party in the opposition Renamo, that affected parts of Sofala and Nampula provinces between 2013 and 2016, led to a reduction of investments, disrupting the flows of existing businesses. On the other hand, the corridors, in particular the Nacala corridor, tend to generate anxiety over land, leading to continuous debates and campaigns over ‘land grabbing’ and land titling.Footnote35

Over time, agricultural development plans for the Beira and Nacala corridors have intersected with other regional plans and a range of different projects. For example, in 2010 the Mozambican government established the Zambezi Valley Development Agency with the aim of promoting economic and sustainable development and boosting investment in four central region provinces – Tete, Manica, Sofala e Zambézia. A significant part of the agency’s work targets agricultural development with projects supporting technical training, agribusiness and infrastructures. In 2016 the Ministry of Economy and Finance launched the $106 million, World Bank-funded Integrated Growth Poles Project with the objective of improving rural employment and economies around the Zambezi Valley and Nacala Corridor in northern and central Mozambique, covering the provinces Nampula, Niassa, Cabo Delgado, Zambezia, Tete, Manica and Sofala – practically covering all of both the Beira and the Nacala corridors.Footnote36

In 2017 the government also launched SUSTENTA – an integrated and inclusive rural development project that aims to stimulate the rural economy, through integrating rural households into the development of sustainable agricultural and forestry value chains in 10 districts of Nampula and Zambeze provinces. In addition to these projects, there are various projects promoted by donors and NGOs – for example in land titling, rural extension, agricultural commercialization, and agribusiness promotion – that intersect with the wider plans.

As a result, agricultural growth corridors in Mozambique have produced complex entanglements of projects implemented at different times and speeds, intersecting with local political contexts, and influenced by international financial dynamics such as the crash of global commodity prices in 2015. Ultimately, both corridors have continued a long history of externally oriented projects which do little to capitalize on the high agricultural potential and rail and road networks in these areas.Footnote37

In the next section, the discussion shifts to these entanglements, specifically by focusing on three selected cases that exemplify the everyday work of international funders and investors, national elites, local bureaucrats, and smallholders, as they perform project success on different occasions.

Infrastructures and fairs

Here, I use the examples of a tomato processing plant, an irrigation scheme, a recently inaugurated silo, and an agribusiness fair to exemplify performances of project success that give visibility to Beira and Nacala agricultural corridors. Firstly, I look at a long-awaited, and short-lived, tomato processing plant, in the administrative post of Tica located in Nhamatanda district, along the Beira corridor, to discuss how media coverage and public statements by government officials overstated the material effects of the tomato processing plant in Tica. Second, I use the description of an agribusiness fair held in Ribáuè district, along the Nacala corridor to show the extent to which investors, smallholders, NGOs, government officials and politicians use agricultural fairs as occasions to overstate agricultural potential and success of the visited districts and provinces. Third, I discuss of a silo complex in the Beira corridor to show how hopes and visions of agricultural development can be demonstrated in infrastructures such as silos, even if they are far from fulfilling the objectives of boosting smallholder agricultural production and commercialization.

A promised tomato processing plant

The administrative post of Tica in Nhamatanda district, which is known for its abundant production of tomatoes that are often left to rot when smallholders are not able to sell all of their produce, saw the construction of its first vegetable processing plant in 2014, a project that was taken up by the provincial administration after the local government failed to mobilize the required funds. The plan of the provincial government was that once operational, the plant was going to process products from the neighbouring districts of Gorongosa and Dondo, and some vegetables from the neighbouring province of Manica.Footnote38 Unable to fit the infrastructure with the required equipment, the provincial government agreed that the building would be managed by the district government. An official at the District Services for Economic Activities explained:

We constructed the building and did not manage to equip it. There are 100ha around the building for the production of tomato but all has come to a halt because we have not been able to raise funds to buy the equipment.Footnote39

In the media, talk of building a tomato processing plant in Tica dates back to 2009, when a local entrepreneur received a reported sum of about $33,000 from the District Development Fund to build a tomato processing plant in order to capitalize on the district’s agricultural potential. Footnote41 In some of the media accounts, the processing plant was presented as if it existed already, running and fulfilling its promise to absorb the horticultural produce of smallholders along the Beira corridor. In 2013 the daily newspaper Notícias published a news piece with the title, ‘Processing plant created in Nhamatanda.’Footnote42 The content of the news was based on an interview with the then district administrator, Sérgio Moiane, who said that ‘a plot had been located for the building of the processing plant’ and that ‘a public tender for constructors had been announced and they were waiting for bids … and expected the building to be completed by December 2013 and the equipment to be installed by February 2014.’Footnote43

In April 2015, another headline by Voice of America read, ‘Tomato processing plant changes the lives of producers in Tica’: the news report proceeded to narrate the story of two women who made their living for over 12 years selling tomato at the small agricultural market by the EN6 [corridor road].Footnote44 Often these women were not able to sell all their produce, thus running into losses. This time the district administrator Sérgio Moiane, announced that the building was going to be completed by May 2015.Footnote45 In February 2018 another headline announced, ‘This year Nhamatanda is going to process tomato’, in an article where the new District Administrator, Boavida Manuel, boasted of the 200,000-tonnes capacity of the future processing plant, and advised smallholders to get ready to ‘produce a lot’ since there was going to be a company to buy their produce.Footnote46

When I visited the factory in March 2018, the building was not equipped, and Agridev operations were limited to the selling of agricultural inputs, provision of extension services and supporting the legalization of smallholders’ associations. A representative of Agridev reiterated:

At the moment, we only have the infrastructure and nothing related to processing. We are still looking for financial resources to acquire the necessary equipment. We offer services to smallholders such as trainings, technical assistance and we are looking into offering access to microfinance services via the Letshego bank. We are dealers for Casa do Agricultor -a Maputo-based national supplier of agricultural productsFootnote47

Interviews with district officials and a synthesis of media reports project a different image, far removed from what is actually taking place on the ground. Ideas such as the introduction of financial services or provision of technical assistance and tillage services are attractive to smallholders, but at the time of writing most of them were yet to materialize. The fire did indeed put an abrupt end to the brief lifespan of the plant – Agridev had been operating the plant for less than six months – but the expectation of agricultural commercialization that the plant had generated in the region long before it began operating exemplified the extent in which the media and local officials can create a narrative of success around a project in anticipation of, or as a way of attracting, the much needed, but seriously lacking, investment capital.

The fact that Agridev, a newly constituted agricultural company, was running the processing plant had in and of itself constituted a story that many considered worth publishing widely, within the wider Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor, where such ‘success stories’ of agricultural potential and productivity were limited. It is also important to note that the advertisement of agricultural potential, which attracted Agridev to Tica to run the processing plant in the first place, illuminated the extent to which such narratives can bring together different and seemingly unrelated projects, such as the Zambezi Valley Development Agency incubator, from where Agridev emerged, and plans by local government officials for agricultural commercialization in the district of Nhamatanda, in this case through the establishment of a tomato processing plant.

Silos in need of grain

Along the corridors of Beira and Nacala, the Mozambique Commodities Exchange built silo complexes with the aim of boosting agricultural commercialization.Footnote49 These were three silos of up to 1,000 tonnes capacity, and two 300-tonne transitory silos for the storage of maize, beans, soy and sesame, all of which were officially unveiled in a high-profile ceremony in 2015 that was attended by President Filipe Jacinto Nyusi.Footnote50 In addition to the silo, there are two warehouses that formerly belonged to the Mozambique Grain Institute – a public marketing and grain storage facility.Footnote51 According to the Mozambique Commodities Exchange, ‘the main beneficiaries of the silos are smallholders, smallholders’ associations, cooperatives, traders, agro-processing companies and stock exchange operators.’Footnote52 This is aligned with the President’s speech during the official opening of the silos in Nhamatanda, where he exhorted Mozambicans to take advantage of the new facilities so as to ‘increase agricultural production.’Footnote53

Despite the above, the response from smallholders has been minimal, as storage costs, and a requirement of a minimum deposit of 5 tonnes has discouraged smallholders from making use of the silos.Footnote54 Instead, smallholders have continued to rely on alternatives that better suit their needs, such as using a number of existing storehouses built through NGO projects, and which are large enough to effectively cater for smallholders’ needs.Footnote55 In addition, there are a number of village granaries that are built near homesteads, and where no fumigation occurs.Footnote56 Perhaps, as a result of this, the silo complex in Nhamatanda is mainly used by a handful of large commercial farms and companies, namely, the Mozambique Fertilizer Company – a Mozambique-based international fertilizer supplier – which in 2018, was their largest client.Footnote57 As noted by the technical staff at the silo in Nhamatanda:

The silos are not yet serving smallholders. Here at the Beira corridor, the market is not a problem for smallholders. For that reason, smallholders do not see the need to store … With few exceptions, smallholders prefer to sell to trucks that go buy from them at the markets or to use storehouses built on the basis of unconventional material. The truth is that smallholders do not have real surplus - one that can last them until the following season - and their expectation was that the Mozambique Commodities Exchange was going to buy their crops. They are not interested in the silo as a storage facility. There are a number of smallholder associations that have storehouses here. Some of these have a capacity for 300 tonnes which is more than what they produce, that is why they do not need our storehouses.Footnote58

After two years in operation, public silos in Nhamatanda are yet to be used by smallholders, as was the expectation. Instead, it is medium and large-scale farmers, and wholesalers and dealers, who use the silos.Footnote60

Like the tomato processing plant in Tica, the silos were presented in the media as ‘the missing infrastructure to boost commercialization’Footnote61 but in the absence of conditions that are attractive to smallholders, such as affordable storage prices and flexible access to stored produce, the silos are far from fulfilling their promise and the government is considering the transfer of their management to private companies.Footnote62 Nevertheless, the silos are contributing to the construction of an image of an agro-based infrastructural setup ready to serve the increasing agricultural production and commercialization.

An agribusiness fair along the Nacala corridor

Between July 7 and 8 of 2018, an agribusiness fair took place at the municipal soccer field of Ribáuè in Nampula province. The fair was entitled ‘Nakosso agribusiness fair: facilitating access to markets,’ and was the first of a series of five fairs to be organized in northern Mozambique by a private company named Market Access Limitada in partnership with the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, through a project entitled Innovation for Agribusiness (InovAgro).Footnote63 Other sponsors included the provincial and district governments, and the multinational Export Marketing Group (ETG).Footnote64

According to respondents, the fair was an important event in the calendar, and it was a follow-up to recommendations made by a business forum that was held in the capital of Nampula province in the previous year.Footnote65 The provincial governor opened the fair, in a ceremony that was also attended by the Ministers of Agriculture and Rural Development, and by the Minister of Industry and Commerce.Footnote66 The fair had stands showing various products by local smallholders’ associations, whose work is often done with the support of district extension officers, and through a number of NGO-supported projects.Footnote67 In addition, private agribusinesses were also exhibiting fresh agricultural products, processed and packaged goods, including agricultural inputs.Footnote68 A local NGO called OLIPA-ODES (Organisation for Sustainable Development) working under commission from the Nacala Logistics Corridor and the Northern Development Corridor, showcased vegetables produced by communities resettled during the construction and operation of the Nacala corridor railway, which still transports mainly coal.Footnote69

As the visiting dignitaries went from one exhibition stand to another, the interaction with exhibitors was punctuated by questions, compliments and suggestions for ‘improvement.’ As the production process of each good was explained, the Minister of Industry and Commerce, Ragendra de Sousa, asked if the exhibitors needed the government to fix prices for agricultural products, to which exhibitors and part of the audience composed of smallholders and local agro-dealers responded in the negative.Footnote70 It appeared that the response aligned with the Minister’s own views, that an indication of reference prices was enough.Footnote71 The opening ceremony ended with the provincial governor’s speech, where he congratulated the exhibitors and encouraged them to continue the ‘good work’. During his speech, the provincial governor overstated what he had witnessed in the exhibition and shared his expectations:

We have seen production, processing, links to the market and those who supply inputs and finance the production [process]. Our expectation is that the yields that we are obtaining in crops like maize, cassava, peanuts and sesame continue to grow even more. We have heard that we can go way beyond two tonnes of maize per ha and also in other crops. I prefer to not speak more about numbers now. We have seen the processing of maize and we have just seen that in addition of processing maize for beer we are processing it for corn starch. Our processing is so well done to the point that in the last economic fair held in Cabo Delgado province, one of the processing companies headed by a woman from Nampula took the first-place prize for processed products. So, small, medium, large producers and the government as well as the civil society we should all work together. We have also seen recipes that can help fight chronic malnutrition using local products. This is the goal of this fair. To show what we do, the path we want to take in the fight for food and nutrition security and the wellbeing of all of us.Footnote72

The example of the fair illustrates how such events can provide occasions for the demonstration of success, and the creation of an ideal vision for the agricultural corridor. The significance of agricultural fairs is perhaps best exemplified by the fact that they form a distinctive feature in the agenda of visiting high-level dignitaries, from the President of the Republic, to provincial governors and ministers.Footnote77 Despite the fact that on some occasions visiting dignitaries have questioned the blatant exhibition of produce brought in from other areas, the fair is presented as a sample of agricultural developments already taking place in other areas of the District covered by the corridor, especially given the efforts local officials put into achieving some kind of geographical representation of exhibitors. Finally, the fair also provides an opportunity for a pedagogy, through the celebration of cases of success that should be seen as models to follow by other actors, in particular smallholders. Next, I use two cases to show how ‘demonstration fields’ are also good occasions for the dissemination of models and ideas.

Exemplary associations

While state officials and NGOs working along the corridor are often eager to perform project successes, the organization of smallholders into associations and production groups is often presented as the basis for materialization of agricultural production along the corridors. The general principle is that technical assistance and commercial success can be best achieved when smallholders are in groups.Footnote78 However, the discussion of the cases in this section highlight how examples of successful associations are overstated, even if these enjoy little support among the local communities.

As a first example, discussion of the unveiling of an irrigation scheme along the Beira corridor that was acquired by a notable smallholder association illustrates how, for this particular irrigation scheme to be successfully run by a smallholder association, external intervention of different actors over a 6-year period was required. Yet, the scheme is presented as a model worthy of replication despite its unique trajectory to organizational and commercial success.

Secondly, I discuss the constitution of a women’s only association in order to benefit from a different irrigation scheme. Differently from the first case, the association was presented as a model of success and a go-to site for visitors – often donors and researchers – despite the fact that it was yet to have its first harvest. Together, the cases highlight the importance of the representation of success for the constitution of the corridor, but also for the various actors and organizations along the corridor, whose work is justified by the successful advancement of ideas such as the smallholder association as the foundation for the realization of the agricultural potential along the corridors.

A successful irrigation scheme

Located in Tica, 15 km from Nhamatanda, the district headquarter, the 39-member (17 women) smallholder association Muda Massequece was established in 2005, with initial support from KULIMA, a Mozambican rural development NGO and later Gapi, a financial services institution.Footnote79

Widely cited (by government officials, civil society organizations, donors and private investors) as the best example of a successful outgrowers scheme, the association focused on horticulture farming that was dependent on traditional farming implements. It was in 2007–08 that the association received its first irrigation scheme project, which covered 35 ha of its land, land whose tenure was secured through the support of the Community Land Initiative (ITC).Footnote80 In particular, ITC gave support in the process of acquiring the related DUAT, an official document that ensures the right to use and benefit from the land.

One of the association’s earliest credit opportunities came through a mobile bank project through which the association’s members made their contributions in cash. But it was not until 2009 that BAGC, together with PROIRRI and ITC, sponsored the process of formalization of the association, which began operating in October 2012.Footnote81 Through such networks, the association developed closer ties with local government institutions, which enabled the association to secure access to the market at the much-sought-after Mafambisse mill, owned by Tongaat Hulett.Footnote82

On 26 March 2016, the then provincial governor of Sofala province, Maria Helena Taípo, unveiled the irrigation scheme in a high-profile ceremony that was attended by the deputy national director of agriculture and forestry, the provincial director of agriculture, representatives from provincial and district governments, development partners, civil society organizations and representatives of local smallholder associations.Footnote83 PROIRI granted 70% of the funds to cover the cost of the irrigation scheme, and Tongaat Hulett advanced the association the remaining 30% and sugar cane seeds for the first crop.Footnote84 Since then, the association has grown three agricultural crops with positive results, and in 2018 was expecting to harvest its fourth campaign.Footnote85 Tongaat Hulett also encouraged the association to expand its farming area and – at the time of writing – the association was considering buying additional farming land from other smallholders in the vicinity of the association’s holdings.Footnote86

The case of Muda Massequece attests to the success of the outgrower scheme in the highly profitable sugar sector in Mozambique. The returns for Muda Massequece are so high that nearly all the founding members of the association no longer work in the farms, or live in the communities next to their association’s fields.Footnote87 Some of the members moved into improved houses bought or built at the local business district.Footnote88

The success of Muda Massequece and its irrigation scheme has been presented as an agricultural ‘success story’ along the Beira corridor, in accounts that rarely consider the financial capital, institutional support and, social and political networks made available to them. In final analysis, Muda Massequece is presented as evidence that the associational model of smallholder organization can thrive in the Beira corridor.

A promising women’s only association

On July 13, 2018 I visited a recently-formed women’s smallholder association in Malema district along the Nacala corridor. At the time of the visit the association, which consists of 23 members (all women), had just cleared and tilled a 1.5 ha plot to plant vegetables. The women were required to have their own farmland close to a water source, and constitute their women-only association, to be eligible for financial and technical support from OXFAM and its Program for Women’s Agricultural Income – Agri-Mulher. Agri-Mulher has a grant of US$ 4,159,961.88 from the Belgian government, and is implemented in Nampula by a consortium of two NGOs: the Rural Extension Association (AENA), which assists smallholders with extension work; and OLIPA (Sustainable Development Organization), which has the responsibility of advising on strategies for market access. Other project partners include (i) the Provincial Peasants Union, and (ii) Observatório do Meio Rural and Women and Law in Southern Africa – Mozambique, two research institutions respectively dedicated to research in rural contexts and women.Footnote89

On the day of my visit, the association members planted onions for the first time, and started using the water pump they had just received from the Agri-Mulher programme. The AENA extension officer supporting the project later explained to me that the project had been delayed for about a year for bureaucratic reasons and that the association was ‘still in the learning phase’ in the cycle of their project.Footnote90 After the interview with the association’s president, I was invited to leave a note on the association’s guest book as, according to her, it was ‘going to help them write their annual report.’Footnote91 She said that other people from outside the province had also visited their association, including researchers and representatives of the Belgium government.Footnote92

The fact that half a dozen people from outside the province had visited and signed the association’s guest book even before they had green fields to show for their effort is a good indicator of the importance of the ‘economy of appearances’Footnote93 in the construction of agricultural corridors. Unlike Muda Massequece, in the previous case, the women’s smallholder association did not need to show success in agricultural production and commercialization. Its existence exemplified the adoption of a widely promoted agricultural production and commercialization model, while at the same time serving as a site where the promise of pro-smallholder agricultural development is expected to become a reality. In the next section, I discuss the implications of the ‘performance of success’ in the cases presented above.

Agricultural corridors as ‘demonstration fields’

For the performances of project success to be effective they need to count on the participation of various actors – local government, NGOs, private investors, financial institutions and smallholders – who are all involved in specific components of the projects and often with distinct individual or group interests. For example, in the case of Muda Massequece, the intervention of the technicians of the district headquarters was instrumental in assuring the credibility of the association to funders, but also in providing technical support when it came to designing an accounting system for the association.

In the absence of resources to implement annual plans fully, public extension officers often work within donor-funded projects or supervise the work of local NGOs providing agricultural extension support to smallholders. This is how local NGOs such as AENA and OLIPA emerge as key local state partners in the implementation of agricultural projects along the corridors.Footnote94 But donor funding also provided an opportunity for collaboration between local NGOs such as AENA and OLIPA.

At the provincial level, smallholders represented by their provincial association, local NGOs and government are organized in agricultural platforms, even if these do not always produce consensus on the subjects discussed.Footnote95 Other projects implemented via provincial and district governments such as SUSTENTA (an integrated and inclusive rural development project), PROIRRI (Sustainable Irrigation Development Project) or PROMER (Program for the Promotion of Rural Markets), all of which run mostly on the basis of international funding operate within districts of the corridor concurrently with Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor and ProSAVANA projects.

Smallholders have long been aware of how the networks of power and capital operate, and their efforts to constitute and name associations according with the requirements of each new project have been incorporated in their livelihood strategies. The women’s association under the Agri-Mulher project in Nampula is a case in point. This association already existed as a mixed group since 2016, farming in fields far from water sources, but to meet the eligibility criteria for the project they rebranded themselves as a women-only organization, and found a plot that met the project requirements. Given their knowledge of the project’s short life, members of the association indicated that they remained committed to their respective family plots.Footnote96

Although in pursuit of different interests, this participation of different actors in the performance of project success constitute on each occasion a ‘demonstration field’. Taken in isolation, ‘demonstration fields’ may reveal no more than a site-specific success story. But taken together, these ‘demonstration fields’ produce an image of interrelated projects that capitalize on road and railway infrastructures.

In arguing that agricultural corridors in Mozambique can be better assessed as ‘demonstration fields,’ where agricultural projects’ success is performed, I do not ignore that there are roads and railways connecting districts in the Mozambican hinterland to specific harbours. I also acknowledge that there are various agricultural projects in districts traversed by or near these transport infrastructures. However, what can be verified empirically is far from what is promised in the projects’ blueprints or what has dominated academic discussion on the materialization of agricultural corridors.

Conclusion

In times when the agricultural potential of districts along the Beira and Nacala corridors is increasingly getting national and international recognition, it seems that implementing a spatial development initiative for agricultural development would provide an ideal solution for a country in need of increasing agricultural production for internal and global markets, consumption and exportation. Like elsewhere, agricultural development corridors have been found to be complicated realities, often distinct from the official rhetoric and projects blueprints.Footnote97

In this article, I have suggested that corridors can be understood as ‘demonstration fields’– sites where agricultural projects are celebrated as cases of success. These performances of success depend on the active participation of various actors – local government, NGOs, private investors, financial institutions and smallholders – all of whom seek to advance their individual and collective agendas.

Rather than the realization of plans and blueprints, I have shown that, it is through the performances of success that agricultural corridors gain materiality on the ground by connecting a set of often temporally and spatially unrelated projects distributed in areas that only have in common the proximity to a road or railway connecting the hinterland to harbours on the Indian Ocean.

Moving our attention to how agricultural corridors are constituted through performances of project success makes it possible for us to consider how corridors can be materialized beyond conventional evaluations of the implementation of agricultural projects and the effectiveness of transport and commercialization infrastructure. Just as in demonstration plots, which are so dear to extension officers, the performance of project success can simultaneously constitute the reality and promise of agricultural corridors.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to colleagues Ian Scoones, Ngala Chome, Emmanuel Sulle and Jeremy Lind for their insights and comments in earlier drafts of this paper. I have also benefited from Anésio Manhiça, Ramah Mckay and Emídio Gune's comments and discussions with Lídia Cabral, with whom I conducted a stint of field research for this paper. This research was made possible through the DFID-funded Agricultural Policy Research in Africa programme of the Future Agricultures Consortium (https://www.future-agricultures.org/apra/).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Interview, Bernardo Augusto, public extension officer (Tica), Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 See for example Mosley and Watson, “Frontier transformations”; Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors;” Hartmann, “The Quest to Find SAGCOT”; and Stein and Kalina, “Becoming an Agricultural Growth Corridor”.

5 See for example Kaarhus, “Land, Investments and Public-Private Partnerships”; Selemane, A Economia Política do Corredor de Nacala; Elliott “Planning, property and plots”; Enns, “Infrastructure Projects and Rural Politics”; Kochore “The road to Kenya?”; Shankland and Gonçalves, “Imagining Agricultural Development”; Monjane and Bruna “Confronting agrarian authoritarism”. See also Chome, “Land, livelihoods and belonging” and Sulle, “Bureaucrats, investors and smallholders” (in this volume).

6 Tsing, “Inside the Economy of Appearances,” 118.

7 Li, “Compromising Power,” 309.

8 Baviskar, “Between Micro-Politics and Administrative Imperatives,” 38.

9 These insights were informed by conversations with Ramah McKay (October 2018), Anésio Manhiça (February 2019) and Jesse Ribot (June 2019).

10 Isaacman, “Cotton is the Mother of Poverty”; Adalima, “Changing Livelihoods in Micaúne”; Vail, “Mozambique’s Chartered Companies”; Chilundo, Os camponeses e os caminhos de ferro.

11 Fonseca, “Os Corredores de Desenvolvimento”.

12 AgDevCO, “Beira Agricultural Growth”; Funada-Classen, “Fukushima, ProSAVNA e Ruth First”.

13 Paul and Steinbrecher, African Agricultural Growth Corridors; Rasagam et al., “Mozambique’s Development Corridors”.

14 See World Bank, “Prospects for Growth Poles”; Jornal Notícias, “ZEE’s para 24 distritos com potencial agrícola” (http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/main/10-economia/41999-zee-s-para-24-distritos-com-potencial-agricola.html) (accessed 9 September 2018).

15 Benfica et al, “The Economics of Smallholder Households”; Burr, Mondlane and Baloi, “Strategic Privatization”; Niño, “Class Dynamics in Contract Farming”.

16 Interview, representatives of SDAE, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018; Gastão da Silva, Director, SDAE, Ribáuè, Nampula, 12 July 2018.

17 MINAG, Zoneamento Agrário de Moçambique.

18 MINAG. “Plano Estratégico”, 43.

19 ACB, Agricultural Investment Activities, 8.

20 Ibid, 27.

21 The list of institutions included: Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (MASA), the Centre for the Promotion of Agriculture (CEPAGRI); Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), The Department for International Development (DFID), SNV Netherlands Development Organization, The World Bank; Standard Bank, Tongaat Hulett, Yara International, National Peasants Union (UNAC), Manica Provincial Farmers’ Union (UCAMA), General Union of Cooperatives (UGC) and number of banks and mining multinationals.

22 AgDevCo, “Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor”, 7.

23 Selemane, A Economia Política do Corredor de Nacala.

24 MINAG, “Plano Estratégico”.

25 Smaley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors.”

26 Shankland, Gonçalves and Favareto, “Social Movements, Agrarian Change”.

27 See Funada-Classen, “Fukushima, ProSAVANA e Ruth First”; Shankland and Gonçalves, “Imagining Agricultural Development”; Chichava, “A Socieda Civil”; Selemane, “A Economia Política”.

28 See Jornal Notícias, “Entre Vale e a MITSUI: Negócio de acções concluído em Setembro”, 31 July 2016. http://jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/economia/52261-entre-a-vale-e-a-mitsui-negocio-de-accoes-concluido-em-setembro.html (Accessed 22 November 2018).

29 Homma, “JICA’s Industrial Cooperation in Africa”.

30 Smalley, “Agricultural Growth Corridors”.

31 These companies include: Grupo Pinesso, a Brazilian agribusiness firm; Mozaco (Mozambique Agricultural Corporation), established in 2013 by Rioforte Investments (Portuguese holding company for Grupo Espírito Santo) and JFS Holding (Portuguese cotton company); and AgroMoz (a partnership involving the richest man in Portugal, the former president of Mozambique and one of the largest land holders in Brazil). See also Okada, “Role of Japan”.

32 Kaarhus, “Land, Investments and Public Private Partnerships”, 102.

33 Interview representative of BAGC, Beira, Sofala 22 August 2018.

34 Interview with representative of APIEX, Nampula, Nampula city 16 July 2018.

35 See for example Clements and Fernandes “Land Grabbing, Agribusiness and Peasantry”; UNAC and GRAIN, The Land Grabbers of the Nacala Corridor; and Selemane, A Economia Política do Corredor de Nacala.

36 Jornal Notícias, “Projecto Polos Integrados já consumiu 70 por cento dos 100 milhões de dólares”, 15 July 2019 https://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/economia/91675-projecto-polos-integrados-ja-consumiu-70-por-cento-dos-100-milhoes-de-dolares [Accessed 20 July 2019].

37 Historically the development of both corridors was affected by the civil war and more recently Beira Corridor has been affected by a proto-war which has affected the circulation of people and goods. For details see Brück, “War and Reconstruction in Northern Mozambique” and Morier-Genoud, “Proto-guerre et négociations”.

38 Interview with representatives of SDAE, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018.

39 Idem.

40 Interview with representative of Agricultural Development (Agridev), Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018.

41 See “Mutuário do fundo distrital a contas com a justiça”, 1 June 2011. http://www.verdade.co.mz/nacional/19916-mutuario-do-fundo-distrital-a-contas-com-a-justica [Accessed 17 August 2018].

42 Jornal Notícias, “Para processamento de hortículas: Fábrica de hortícolas criada em Nhamatanda”, 10 September 2013. http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/sociedade/2543-para-processamento-fabrica-de-horticolas-criada-em-nhamatanda.html (Accessed 11 November 2018).

43 Idem.

44 See VOA, “Fábrica de processamento de tomates muda a vida de produtores em Tica”, 22 April 2015. https://www.voaportugues.com/a/fabrica-de-processamento-de-tomates-muda-a-vida-de-produtores-em-tica/2730542.html (Accessed 11 November 2018).

45 Idem.

46 Sapo Notícias “Nhamatanda vai processar tomate ainda este ano”, 22 February 2018. https://noticias.sapo.mz/economia/artigos/nhamatanda-vai-processar-tomate-ainda-este-ano (Accessed 12 November 2018).

47 Interview with representative of Agricultural Development (Agridev) Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018

48 Interview with SDAE technicians, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018; Interview, representative of Agricultural Development (Agridev) Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018; Field observation and informal interviews, Nhamatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018.

49 See Jornal Notícias, “Silos: a infra-estrutura que faltava para dinamizar a comercialização”, 5 December 2014. http://jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/caderno-de-economia-e-negocios/27880-silos-a-infra-estrutura-que-faltava-para-dinamizar-a-comercializacao (Accessed 10 October 2018).

50 See Jornal Notícias “Silos para Nhamatanda”, 12 May 2015. http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/economia/36321-silos-para-nhamatanda (Accessed 10 October 2018).

51 Interview, representative of Nhamtanda Silo, Nhatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018.

52 See Sapo Notícias, “Presidente inaugura silos orçados em 2,6 ME no centro do país”, 12 May 2015. https://noticias.sapo.mz/actualidade/artigos/presidente-inaugura-silos-orcados-em-26-me-no-centro-do-pais (Accessed 10 October 2018).

53 See Jornal Notícias “Silos para Nhamatanda”, op. cit.

54 Interview, representative of Associação Agro-Pecuária Camponeses do 3ro Bairro, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 06 July 2018; Field observations, Nhamatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018; Interview, representative of Nhamtanda Silo, Nhatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018.

55 Idem.

56 Field observation and informal interviews, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 06 July 2018.Interview, representative of Nhamtanda Silo, Nhatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018.

57 Field observation and informal interviews, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 06 July 2018.

58 Interview, representative of Nhamtanda Silo, Nhatanda, Sofala 24 August 2018.

59 Idem.

60 Idem. For a broader discussion on the recently built silos and agricultural commercialization see Dadá, Nova and Mussá “Silos da Bolsa de Mercadorias”.

61 See Jornal Notícias “Silos: a infra-estrutura que faltava”, op. cit.

62 Zitamar News, “Planned grain silo privatisation threatens Mozambique's small-scale farmers”, 11 January 2018. https://zitamar.com/planned-grain-silo-privatisation-threatens-mozambiques-small-scale-farmers/ (Accessed 14 October 2018).

63 Interview with SDAE extension officer, Ribáuè, Nampula, 12 July 2018.

64 Idem.

65 Field Observation, Nakosso: Feira de agronegócios – facilitando o acesso aos mercados, Ribáuè’s Municipal Soccer, Ribáuè, Nampula, 7 and 8 July 2018; See also Jornal Notícias, “Nampula realiza fórum de investimentos e negócios”, 5 December 2017 http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/breves/74029-nampula-realiza-forum-de-investimentos-e-negocios.html (Accessed 25 October 2018).

66 Field Observation, Nakosso: Feira de agronegócios – facilitando o acesso aos mercados, Ribáuè’s Municipal Soccer, Ribáuè, Nampula, 07 and 08 July 2018

67 Ibid.

68 Ibid.

69 Ibid

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Nampula’s governor Victor Borges’s speech at the opening of the Nakosso agribusiness fair: facilitating access to markets, Ribáuè, July 7. Field Observation, Nakosso: Feira de agronegócios – facilitando o acesso aos mercados, Ribáuè’s Municipal Soccer, Ribáuè, Nampula, 7 July 2018.

73 Rádio Comunitária de Ribáuè, “Notas de Reportagem” (07:00 pm), 7 July 2018; Field observation, Ribáuè, Nampula, 07 July 2018.

74 Exhibitors at the fair included Matharia Empreediments, GAPI – a finance services institutions, Nacala Logistics Corridor, Regua Chipangue – an agro-processing small company, WISSA – an agro-processing small company, DADTCO Mandioca Mocambique, OLIPA, AENA, Peasants District Union, SDAE – the District Services for Economic Activities.

75 Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, Balanço Das Actividades Realizadas Durante Os Primeiros Nove Meses - 2016; Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, Balanço Das Actividades Realizadas Durante o Primeiro Trimestre; Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, Plano Económico e Social e Orçamento Do Distrito - 2018.

76 State spectacles as a way of enacting success have a long history in Mozambique and have been taken up by recent governments. See for example Gonçalves, E. “Chronopolitics.”

77 It is a generalized practice among Mozambican politicians to visit agricultural fairs and demonstration plots whenever they tour rural districts.

78 MINAG, “Plano Estratégico.”

79 See GAPI (ww.gapi.co.mz) (Accessed 12/10/18).

80 Interview with member of smallholder Muda Massequece Association, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018.

81 Ibid.

82 Ibid.

83 Jornal Notícias, “Novo regadio para Nhamatanda”, 27 March 2016. http://www.jornalnoticias.co.mz/index.php/internacional/52001-luta-contra-pobreza-em-mulheres-jovens-celebridades-pedem-accao-dos-lideres-mundiais (Accessed 12 October 2018); ITC, “Associação Muda-Macequece: Efeitos de registo de terras comunitárias na promoção de sinergias com investidores privados: exemplo da associação Muda-Macequesse na promoção de agricultura comercial”, http://www.itc.co.mz/portfolio-items/estudo-de-caso-associacao-muda-macequece/ (Accessed 12 October 2018).

84 Interview with SDAE technicians, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018.

85 Idem.

86 Interview with member of smallholder Muda Massequece Association, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 28 March 2018; Interview with SDAE technicians, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018.

87 Idem.

88 Case built on the basis of site visit (March 2018) interviews at the Associação Muda Macequesse, officers from the de district department of economic activities and CSOs based in Beira city.

89 Field observation, Associação de Namimbava Sede, Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018; Interview, Florinda Felizmina, Associação de Namimbava Sede, Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018; See also OXFAM, https://www.facebook.com/oxfam.moz/posts/programa-para-o-aumento-do-rendimento-agr%C3%ADcola-das-mulheres-agri-mulher-2017-202/1862583107346502/ (Accessed 16 December 2018). Olipa – Nossos projectos, http://olipa-odes.org/index.php/nossos-projectos (Accessed 16 December 2018).

90 Interview, Gaspar Extension Officer (AENA), Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018; Field observation, Associação de Namimbava Sede, Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018;

91 Interview member of Associação de Namimbava Sede, Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018.

92 Idem.

93 See Tsing, “Inside the Economy”.

94 During interviews in both districts the District Directors of Economic Activities proudly informed that their districts had public extension workers in the totality of administrative subdivisions but they also recognized that representation did not mean full coverage. Interview, Caetano Benedito and André Pita, SDAE, Nhamatanda, Sofala, 27 March 2018; Interview, Gastão da Silva, Director, SDAE, Ribáuè, Nampula, 12 July 2018

95 See Chichava, “A Sociedade Civil”.

96 Interview, Florinda Felizmina, Associação de Namimbava Sede, Malema, Nampula, 13 July 2018. During other interviews with extension officers one of the complains was that smallholders are often sceptical of external and collective projects preferring to always maintain individual plots where they usually farm using tradition seeds without agricultural inputs. For this point see also Feijó and Agy, “Do Modo de Vida Camponês à Pluractividade.”

97 See for example Mosley and Watson “Frontier transformations”; Hartmann, “The Quest to Find SAGCOT”; Elliott “Planning, property and plots”; Enns, “Infrastructure Projects and Rural Politics”; and Kochore “The road to Kenya?”

Bibliography

- ACB. Agricultural Investment Activities in the Beira Corridor, Mozambique: Threats and Opportunities for Small-Scale Farmers. Johannesburg: African Centre for Biodiversity, Kaleidoscopio and União Nacional dos Camponeses, 2015.

- Adalima, José. “Changing Livelihoods in Micaúne, Central Mozambique: From Coconut to Land.” 2016.

- AgDevCo. “Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor: Delivering the Potential,” 2010.

- Baviskar, Amita. “Between Micro-Politics and Administrative Imperatives: Decentralisation and the Watershed Mission in Madhya Pradesh, India.” European Journal of Development Research 16, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 26–40. doi: 10.1080/09578810410001688716

- Benfica, Rui M. S., Julieta Zandamela, Arlindo Miguel, and Natercia de Sousa. “The Economics of Smallholder Households in Tobacco and Cotton Growing Areas of the Zambezi Valley of Mozambique,” 2005.

- Brück, Tilman. “War and Reconstruction in Northern Mozambique.” The Economics of Peace and Security Journal 1, no. 1 (2006): 30–39. doi: 10.15355/epsj.1.1.30

- Buur, Lars, Carlota Mondlane Tembe, and Obede Baloi. “The White Gold: The Role of Government and State in Rehabilitating the Sugar Industry in Mozambique.” The Journal of Development Studies 48, no. 3 (March 1, 2012): 349–362. doi:10.1080/00220388.2011.635200.

- Buur, Lars, Carlota Mondlane, and Obede Baloi. “Strategic Privatisation: Rehabilitating the Mozambican Sugar Industry.” Review of African Political Economy 38, no. 128 (June 1, 2011): 235–256. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2011.582762

- Chichava, Sérgio. “A Sociedade Civil e o ProSAVANA Em Moçambique.” In Desafios Para Moçambique 2016, edited by Luís de Brito, Carlos Nuno Castel-Branco, Sérgio Chichava, and António Francisco, 375–384. Maputo: IESE, 2017.

- Chilundo, Arlindo. Os Camponeses e os Caminhos de Ferro e Estradas em Nampula (1900-1961). Maputo: Promedia, 2001.

- Chome, Ngala. “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging: Negotiating Change and Anticipating LAPSSET in Kenya’s Lamu County.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020).

- Clements, Elizabeth, and Bernardo Fernandes. “Land Grabbing, Agribusiness and the Peasantry in Brazil and Mozambique.” Nova York, 2012.

- Elliott, Hannah. “Planning, Property and Plots at the Gateway to Kenya’s ‘New Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 511–529. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266196

- Enns, Charis. “Infrastructure Projects and Rural Politics in Northern Kenya: The Use of Divergent Expertise to Negotiate the Terms of Land Deals for Transport Infrastructure.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 0, no. 0 (October 26, 2017): 1–19.

- Fair, Denis. “Mozambique: The Beira, Maputo and Nacala Corridors.” Africa Insight 19, no. 1 (1989): 21–27.

- Feijó, João, and Aleia Agy. “Do Modo de Vida Camponês à Pluractividade: Impacto Do Assalariamento Urbano Na Economia Familiar Rural.” In Observador Rural. Maputo: OMR, 2015.

- Fonseca, Madelena Pires da. “Os Corredores de Desenvolvimento Em Moçambique.” Africana Studia: Revista Internacional de Estudos Africanos 6 (2003): 201–230.

- Funada-Classen, Sayaka. “Fukushima, ProSAVANA e Ruth First: Análise de ‘Mitos Por Trás Do ProSAVANA’ de Natália Fingermann.” Treatises on Studies of International Relation 2, no. 2 (2013): 85–114.

- Gonçalves, Euclides. “Chronopolitics: Public events and the temporalities of state power in Mozambique.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Witwatersrand, 2012.

- Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda. Balanço Das Actividades Realizadas Durante o Primeiro Trimestre. Nhamatanda: Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, 2017.

- Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda. Balanço Das Actividades Realizadas Durante Os Primeiros Nove Meses - 2016. Nhamatanda: Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, 2016.

- Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda. Plano Económico e Social e Orçamento Do Distrito - 2018. Nhamatanda: Governo do Distrito de Nhamatanda, 2017.

- Hartmann, Gideon. “The Quest to Find SAGCOT: Erratic Space(s) and Fragments of Interpretation.” Accessed February 20, 2019. https://www.crc228.de/2019/01/17/the-quest-to-find-sagcot-erratic-spaces-and-fragments-of-interpretation/.

- Homma, Toru. “JICA’s Industrial Cooperation in Africa.” Tokyo, 2014.

- Isaacman, Allen. Cotton Is the Mother of Poverty: Peasants, Work and Rural Struggle in Colonial Mozambique, 1938-61. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1996.

- Kaarhus, Randi. “Land, Investments and Public-Private Partnerships: What Happened to the Beira Agricultural Growth Corridor in Mozambique?” The Journal of Modern African Studies 56, no. 1 (March 2018): 87–112. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X17000489

- Kochore, Hassan. “The Road to Kenya?: Visions, Expectations and Anxieties Around new Infrastructure Development in Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 494–510. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266198

- Li, Tania. “Compromising Power: Development, Culture, and Rule in Indonesia.” Cultural Anthropology 14 3 (August 1999): 295–322. doi: 10.1525/can.1999.14.3.295

- MEF, and JICA. “O Projecto Das Estratégias de Desenvolvimento Económico Do Corredor de Nacala Na República de Moçambique - PEDEC-NACALA (Relatório Final de Estudo),” 2015.

- MINAG. “Plano Estratégico Para o Desenvolvimento Do Sector Agrário (PEDSA), 2011-2020,” 2011.

- MINAG. Zoneamento Agrário de Moçambique. Maputo: MINAG, 2007.

- Monjane, Boaventura, and Natacha Bruna. “Confronting Agrarian Authoritarianism: Dynamics of Resistance to PROSAVANA in Mozambique.” Journal of Peasant Studies 47, no. 1 (January 2020): 69–94. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2019.1671357

- Morier-Genoud, Éric. “Proto-guerre et Négociations: Le Mozambique en Crise, 2013-2016.” Politique Africaine 145, no. 1 (2017): 153–175. doi: 10.3917/polaf.145.0153

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199

- Okada, Kana. “Role of Japan in Offshore Agricultural Investment: Case of ProSAVANA Project in Mozambique.” MA diss., Institute of Social Studies, 2014.

- Paul, Helena, and Ricarda Steinbrecher. African Agricultural Growth Corridors and the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition: Who Benefits, Who Loses? Oxford: EcoNexus, 2013.

- Pérez Niño, Helena. “Class Dynamics in Contract Farming: The Case of Tobacco Production in Mozambique.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 10 (October 2, 2016): 1787–1808. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1180956

- Pérez Niño, Helena. “Post-Conflict Agrarian Change in Angónia: Land, Labour and the Organization of Production in the Mozambique-Malawi Borderland.” PhD, University of London, 2014.

- Rasagam, Ganesh, Michael Engman, Gurcanlar Tugba, and Eneida Fernandes. “Mozambique’s Development Corridors: Platforms for Shared Prosperity.” In Mozambique Rising: Building a New Tomorrow, edited by Doris C. Ross, 87–96. Washington, DC: IMF, 2014.

- Selemane, Thomas. A Economia Política Do Corredor de Nacala: Consolidação Do Padrão de Economia Extrovertida Em Moçambique. Maputo: Observatório do Meio Rural, 2017.

- Shankland, Alex, and Euclides Gonçalves. “Imagining Agricultural Development in South–South Cooperation: The Contestation and Transformation of ProSAVANA.” World Development, China and Brazil in African Agriculture 81 (May 1, 2016): 35–46.

- Shankland, Alex, Euclides Gonçalves, and Arilson Favareto. “Social Movements, Agrarian Change and the Contestation of ProSAVANA in Mozambique and Brazil.” CBAA Working Paper. Brighton: IDS, 2016.

- Smalley, Rebecca. “Agricultural Growth Corridors on the Eastern Seaboard of Africa: An Overview.” Working Paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 2017.

- Stein, Serena, and Marc Kalina. “Becoming an Agricultural Growth Corridor: African Megaprojects at a Situated Scale.” Environment and Society: Advances in Research 10 (2019): 83–100. doi: 10.3167/ares.2019.100106

- Sulle, Emmanuel. “Bureaucrats, Investors and Smallholders: Contesting Land Rights and Agro-Commercialisation in the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT).” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020).

- Topsoe-Jensen, Bente, Padil Salimo, Paula Monjane, Sandra Manuel, and Pennarz Pennarz. Joint Evaluation of Support to Civil Society Engagement in Policy Dialogue: Mozambique Country Report. Maputo: ITAD-COWI, 2012.

- Tsing, Anna. “Inside the Economy of Appearances.” Public Culture 12, no. 1 (January 1, 2000): 115–144. doi: 10.1215/08992363-12-1-115

- UNAC and GRAIN. The Land Grabbers of the Nacala Corridor: A New Era of Struggle against Colonial Plantations in Northern Mozambique. Barcelona: UNAC and GRAIN, 2015.

- Vail, Leroy. “Mozambique’s Chartered Companies: The Rule of the Feeble.” The Journal of African History 17, no. 3 (July 1976): 389–416. doi: 10.1017/S0021853700000505

- World Bank. “Prospects for Growth Poles in Mozambique,” 2010.