ABSTRACT

This work analyses the politics of anticipation and ensuing fears, tensions and conflicts in relation to Kenya’s Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor which is to pass through several previously marginalized counties in the north of the country. Isiolo county, in the centre of Kenya is home to several different ethnic groups of whom some are perceived to be better informed about LAPSSET than others, or have certain advantages in terms of claims to indigeneity, ethno-political dominance, land tenure security or access to markets, which help them to position themselves accordingly. This anticipatory positioning – actions people take in anticipation of the future – is raising fears and heightening the claiming of land and ethnic boundary-making, leading to heightened tensions and exacerbating existing conflicts of which three specific cases are considered. We show how ethno-political divides on a national and regional level become effective at the local and county level, but at the same time, how the positioning of actors in anticipation of future investments impacts on ethnic boundary-making, as division lines are re-enacted and redrawn.

I see a change in the future, in 20 years to come. New development, education, long-lasting solutions for peace. I also see the increase in the use of violence due to the implementation of LAPSSET project as communities might use force to get their rights, […] displacement of pastoralists as they are not aware of the project and their land rights […] There will also be increase in gun use due to loss of land to the elites […] This thing called LAPSSET will divide us more than uniting us.Footnote1

Since independence Kenya has had an intermittent focus upon infrastructural development as a key to driving growth.Footnote3 Kenya’s Vision 2030, announced in 2008 again prioritized infrastructural development to connect parts of the country through roads, railways, ports, airports, waterways and telecommunications and investment.Footnote4 And, while previous development plans favoured the former “White Highlands” and their environs in southern Kenya, this time, the focus was laid on the country’s marginalized north: the government claimed that ‘by 2030 it will become impossible to refer to any region of our country as remote.’Footnote5

This article contributes to the increasing body of knowledge concerning the ways the future is implicated in the present rolling-out of developmental megaprojects, and in particular the politics of anticipation as visions are translated on the ground and local actors attempt to position themselves to benefit from the expected developments. It is interested in the social fissures which may be deepened by these processes, in particular those which run along ethno-political lines, a common paradigm in Kenya for accessing resource wealth and opportunity.

It is our contention that the “high-modernist” Footnote6 infrastructural plans like LAPSSET do not just dissolve into localized practice but are performative by spanning a field of future opportunities and constraints in which actors position themselves, enhancing contestations and conflicts.Footnote7 The role of expectations towards mega-projects in enhancing conflicts is increasingly recognized,Footnote8 heightening tensions that are often framed along ethno-political lines.Footnote9 “Knowledge controversies,” the struggle over what should and should not be known about the planned developmentsFootnote10 and who is able to access information about future developments, are central to such politics of anticipation. Some actors have the economic or knowledge capital or political advantage to “buy-in” to the big vision, while others don’t.

In Isiolo, a semi-arid cosmopolitan county in the centre of Kenya, where several infrastructure projects are located, some ethnic groups are perceived to be better positioned to be informed about LAPSSET than others, or have certain advantages in terms of claims to indigeneity, ethno-political dominance, land tenure security or access to markets, which help them to position themselves accordingly. The county has a history of inter-communal and ethno-political conflict, and is also a regional hub for the illegal small-arms trade. Pastoralists risk being dispossessed of grazing land, as the majority pastoralist population has very low literacy rates and the communally held rangelands are not yet protected by community titles, although the possibility is foreseen in a new Community Land Act.Footnote11

Against this volatile background, the paper lays out a distinctive contribution: that anticipatory practices can be enacted via ethnic competition and conflict. Cormack observed how the heritage of rangeland management is mobilized and ethnicized in Isiolo in response to LAPSSET plans,Footnote12 while in the town, Elliot notes that between 2014 and 2015, the anticipation of LAPSSET and the increased demand for plots that accompanied it was amplifying the politics of land, settlement and ethnic identity.Footnote13 This article contributes to the emerging work on the LAPSSET Corridor, focusing on other parts of Isiolo county. It is based on several phases of qualitative social science research in Isiolo county from 2016 to date, drawing on more than 50 individual interviews and 20 focus group discussions with respondents occupying various tiers and sectors of society including pastoralist men and women, farmers, elders, business people, NGOs, religious leaders, politicians, administrators and state and non-state security personnel. After briefly elaborating our perspective on ethnic politics, ethnic territorialization and anticipation in Kenya and the north, we provide some background on LAPSSET and Isiolo county. We then bring to the fore the expectations, hopes, fears, positions, and positioning of different actors with regard to the anticipated benefits of LAPSSET, relating them to present conflicts that are unfolding in areas along the LAPSSET Corridor in Isiolo county before even the infrastructure is materially present.

Ethnic politics and territorialization in Kenya

A brief history of ethnic politics and territorialization is necessary to contextualize the ethnicized claim-making occurring in the anticipation of the LAPSSET project. While ethnic territories existed to some extent in the pre-colonial period as historians record,Footnote14 these were more fluid and dynamic than the rigid and regulated boundaries that followed under the colonial administration.Footnote15 The colonial strategy was pursued partly for the ease of administration, effected through the appointment of village headmen and location chiefs (who would need the trust and understanding of their subjects).Footnote16 In the post-colonial period, ethnic territorialization was further strengthened and politicized through the advent of votes for all citizens, and later through multi-party politics in 1992 with its geographically located constituencies. More recently since 2013, the enactment of devolution, as provided for in the 2010 Constitution has created new centres of power in counties and raised the stakes for control of the budgets and resources therein. While this has had the effect of reducing the country’s previous “winner take all” polarization,Footnote17 at the same time, it is has had the effect in some places of intensifying ethnic territorialization and inter-county boundary conflicts.Footnote18

Jenkins also notes that ethnic identification and territorialization has remained strong in the post-colonial period, particularly in the arena of politics, where the “immigrant-guest” metaphor plays out; meaning while non-indigenous people may be welcomed, they are expected to abide by the rules, that is, to align themselves with the political preferences of their neighbours.Footnote19 However, Lynch also notes, observing politics in parts of western Kenya (Mt Elgon and Baringo), that there is fluidity in ethnic identification; ethnic groups and their boundaries may be constructed and deconstructed – even if not completely “invented” – in a pragmatic manner in order to stake claims on resources. Lonsdale similarly notes that land is ‘as much a political asset as a social and economic resource,’Footnote20 and claims of autochthony are used as strategy for claiming it.Footnote21 Other claims on land besides autochthony, he notes, include claims of being able to effectively control, manage or work the land – a strategy often used by “immigrants” or “guests,” as opposed to the original inhabitants who may be perceived not to have fully exploited it.

In the northern rangelands specifically, colonial government policy also determined the limits of territory for ethnic pastoralist groups, making some contested directives which continue to feed into conflict today. As Lynch has shown for other regions in Kenya, Schlee and Shongolo explain relationships between the Oromo – which the Borana nowadays consider themselves to form part of – and Somali pastoralist groups in the Kenya-Ethiopia border area are fluid and their ancestry intertwined, which contributed to a situation of shifting narratives of ethnic affiliation and political alliances.Footnote22

Key to the dynamics of ethnic territorialization is a scramble for land, which in northern counties is still mostly communally owned. The Land Act (2012) and Community Land Act (2016) were enacted to provide for pastoralist land rights by recognizing their rights over communally owned land and allowing for group registration and compensation. However, the law also has the unintended consequence of formalizing previously more fluid and negotiable boundaries, which may contribute to ethnic territorialization. Further internal and external factors increase ethnicized scrambles for land, as Greiner identifies in his work on East Pokot, Baringo, Kenya, an equally semi-arid, pastoralist area situated to the southwest of Isiolo county. He argues that in addition to political devolution and internal dynamics of increasing trends of sedentarization and agro-pastoralist livelihoods,Footnote23 investment projects and their anticipation impact on ethnic territorialization. In the following, this work will further elaborate on this dynamic for the case of Isiolo.

Ethnic politics in Isiolo county

Isiolo county, like much of northern Kenya is politically and socio-economically marginalized as a result of its remote geographical location, aridity and colonial and post-colonial political history. Relevant here is Isiolo’s involvement in the irredentist “Shifta War” from 1963 to 1967 (in which inhabitants of the northeast agitated to join a Greater Somalia) and an ensuing prolonged emergency period in which the state response was characterized by collective punishment and marginalization.Footnote24 The economy of Isiolo is mostly anchored in pastoralism and to a lesser extent, wildlife conservation and tourism; agricultural development is very limited and confined to areas along the sole major source of water in the county, the Ewaso Nyiro river.Footnote25

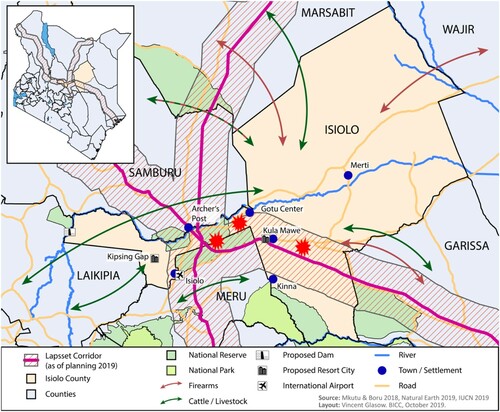

The main ethnic groups include the pastoralist Borana, Somali,Footnote26 Samburu and Turkana and the agriculturalist Meru. It is generally agreed that Borana are politically dominant in the county, and physically occupy the largest part of the land. Borana claims to Isiolo are generally made on the basis that the colonial government gave them exclusive rights to all of Isiolo county east of Ngaremara (the ward that lies in the panhandle-shaped part of Isiolo as shown in ) as Boye and Kaarhus explain.Footnote27 With regard to the other ethnic groups, these authors note that the Samburu who claim to have been there previous to the Borana were forced westwards and north of the Ewaso Nyiro into what is now Samburu county, and into parts of what is now Oldonyiro ward in Isiolo county. Some Somali clans came as traders in the colonial era and have claims in and around Isiolo town, while Turkana were brought as workers into the same area at that time. Meru, and other Somali clans were later immigrants into Isiolo town and Garbatulla and Kinna respectively, taking advantage of Borana displacements and losses during the Shifta War. Somali clans from Wajir and Garissa have historically claimed only access and user rights in dry seasons.Footnote28

Figure 1. LAPSSET Corridor in Isiolo county (Flash symbols denote sites of tension and conflict and described in this article).

There is a general mutual acknowledgement of the various claims, but perennial resource-based conflicts between Borana and Samburu along the county borders, and Borana and Somali groups along the borders of Wajir and Garissa at times take ethnopolitical and territorial dimensions.Footnote29 There is also frequent conflict over resource access between pastoralists and the agriculturalist Meru of Meru county along a contested inter-county border, which similarly has strong political overtones.Footnote30 The recent past has seen violent clashes in Isiolo in the 2007 pre-election periodFootnote31 and again in 2009–2012 in which up to 300 people died, related to territorial and political dominance in Isiolo North constituency.Footnote32

The politics of anticipating infrastructure projects

Such ethno-political conflict is also related to infrastructural projects planned in the region. Arguably, the anticipation of future displacement and political disenfranchisement as well as future benefits pushes land claims in Isiolo. Recent research interest has focused upon ‘the economy of anticipation’ in economic zones or corridors where developments are largely ‘not yet.’Footnote33 In the words of Cross, ‘To speak of an economy of anticipation is to focus our attention on the diverse ways in which people orient themselves toward the future and the ways that expected or promised futures conflict or converge.’ Describing large-scale infrastructure project plans in India, he elaborates on many kinds of ‘anticipatory practices’ of envisioning, planning and preparation which take place there.Footnote34

In an economy of anticipation, the official vision of planners is just one – even if the most powerful – among a range of diverging visions and fears of the future as espoused by different sections of society. The idea, therefore, differs from a frontier perspective, which assumes that, similar to the colonial governments which went before, Footnote35 official planners are often ignorant of local land-use practices and perceive the spaces before them as unoccupied, unutilizedFootnote36 or backward and in need of transformation.Footnote37 The concept of a ‘politics of anticipation’ that scholars of environmental studies have proposed alerts us to the variegated practices and logics of future-making, highlighting that explicit imaginaries such as developmental visions are just one dimension of future-making. Practices constitute another dimension, where future-making may also be unconscious and implicit.Footnote38 Referring to such variegated dimensions and practices of anticipation, we conceptualize the actions of various groups reacting to official developmental visions as ‘anticipatory positioning.’

Cross also draws attention to the emotions attached to anticipation, noting that these are ‘deeply affective spaces in which the future is felt, encountered and inhabited.’Footnote39 Similarly, Haines in her study on a planned highway in Belize notes that ‘applying the lens of anticipation reveals how expectations and fears can affectively animate social and political patterns, emphasising particular versions of history and visions of the future in processes of shaping resources and negotiating access and rights.’Footnote40 Greiner equally evokes an economy of anticipation in his work on East Pokot, examining increasing practices of individual fencing of land plots among agro-pastoralists in East Pokot, who expect future investments in the region from renewable energy development (geothermal)Footnote41 and the LAPSSET Corridor. He refers to an economy of anticipation ‘primarily to grasp the anxiety, motivation, and agency involved with respect to people’s expectations of future material benefits.’Footnote42

The planned LAPSSET corridor signifies enormous socio-economic and ecological transformation for the northern counties and yet, at present, there is very little of the actual project on the ground. Plans consist of a road, railway and oil pipeline, traversing seven counties from Turkana to Lamu Port. The corridor is to be 500 m wide, flanked by 25 km wide special economic zones on each side, and a resort city whose water needs would be served by a twin dam complex on the Ewaso Nyiro river in IsioloFootnote43 thereby threatening downstream communities. Progress has been slower than planned, and at the time of writing, the only completed infrastructural projects associated with LAPSSET are three berths of the Lamu port, the renovation of Isiolo airport, an abattoir (yet to be operationalized) and the Isiolo-Moyale highway.Footnote44 Although the latest LAPSSET route has been made public in 2019,Footnote45 participation has been rather uneven.Footnote46

Another important development deserves a mention: a donor-funded highway from Isiolo through Mandera in the far northeast of the county heralds profitable trade links with Somalia and better services for the northeast.Footnote47 Likewise, the Isiolo-Moyale highway has led to improved trade links with Ethiopia, a reduction in travel times and reduced opportunity for banditry.Footnote48 However, the new airport brought problems of displacement from community land, irregular and disorderly compensation and resettlement processes; land grabbing by political elites in the wake of the administrative chaos following devolution Footnote49 and restrictions of pastoral mobility.Footnote50 An estimated 1,000 people remain displaced and uncompensated.Footnote51

Although little of the infrastructure foreseen in LAPSSET plans in Isiolo county is implemented as of yet, recent research has shown that the anticipation of future benefits and dispossession is already driving present changes. Lind et al. note that the ‘new emphasis on developing pastoralist areas through investment in resources, land, infrastructure and small towns is resulting in new forms of territorialization, contentious politics and social difference.’Footnote52 This is illustrated by Elliot who describes ethnic politics in Isiolo county relating to land, as embodied in the anticipatory actions of ordinary people. In Isiolo town these include fencing, building, occupying, purchasing and acquiring legal documents. Although there is a desire for economic inclusion, this is also about political inclusion by ‘staking a claim on the future city.’ Laying exclusive claims to land, both individual and collective, is how people ensure their political inclusion.Footnote53 Elliot’s work identifies a process of ‘town-making’ that is, inviting one’s kin to settle to achieve political representation.Footnote54 She specifically mentions the politics of anticipation in the smaller settlement of Gotu town discussed below. In Gotu, Garre people have settled in historically Borana ancestral lands and gained some political favours through their support of the former Isiolo governor’s campaign, so that some Borana fear that Garre would claim Gotu as ‘theirs’.Footnote55 Thus LAPSSET is speculated to threaten Borana land ownership and hence political dominance through the economic gains of other ethnic groups which may later translate into political gains. Below we present our own empirical findings relating to such dynamics.

Findings

Positions and positioning

The anticipated LAPSSET project has led various actors to position themselves to benefit from economic opportunities or compensation for land. There are high levels of land speculation by people who would appear to have inside knowledge and political connections.Footnote56 At the time of writing a social media post was circulating about five pieces of grabbed community land in Ngaremara ward near Isiolo town (see ). Such grabbing can involve members of the communities local to Isiolo, or outsiders, and be facilitated by leaders at various levels, from local informal leaders, and civil society leaders to county and national government. A LAPPSET Corridor Development Authority Official confirmed:

You see […] with the resort city, people are jumping all over for land, even killing each other […]. As an authority, we were never prepared for such large-scale land grabbing and land speculation by elites that we have seen interested in the LAPSSET corridor […].Footnote57

On the other hand, some Turkana and others have welcomed the titling of land in Ngaremara and around Isiolo town. These views seem to relate to the likelihood of benefit through compensation or saleable land, or the viability of that land for alternative uses to pastoralism. An official in the land adjudication office said: ‘They have been pressuring us … The wananchi [citizens] ask for titles all the time.’Footnote61 A local peace worker of Borana ethnicity developed a vision of individual titling that sounded like paradise on earth:

And we will be very proud actually as citizens of this country because some of us have never seen a title deed […] And we don’t know how it looks like. It’s a small document but very precious […] In fact if I own it, my sons and daughters will not work. I will just sink a borehole and they will work in their farms (…) And we will be very happy … So in fact when the mega-projects will start […], we can also embark on growing tomatoes and onions. One day I got 2.8 million Kenya Shillings ($ US 28,000) from onions … only in four acres of land. As a pastoralist, I will not look after livestock now, I’m not ready because it is hardship.Footnote62

[…] these big mega projects were all targeted in Isiolo, I think the government has an aim of actually displacing, displacing the local people in Isiolo […] A lot of immigrants from elsewhere will come to Isiolo and majority of us from Isiolo will be displaced.Footnote64

Tensions in Gotu location

Gotu location lies to the north of the proposed LAPSSET route and falls within the proposed special economic zone. It is also about 10 km north of the Isiolo-Madogashe road to be renovated by the World Bank. The north of Gotu location abuts the Ewaso-Nyiro river for a stretch of over 60 km and the small cluster of mabati (corrugated iron) houses known as Gotu town is located there. Gotu is a water source, hence a dry-season grazing zone for the Borana pastoralist community and the settlement sprang up less than two decades ago.Footnote66 The area is attractive for several reasons including planned developments and potentials for ranching, agriculture and mineral exploitation.

Although Gotu location is mainly inhabited by Borana pastoralists, there are around 60 Garre Somali households living in and around Gotu town.Footnote67 They carry out pastoralism, farming and trade and are well-placed to benefit from LAPPSET development. Amongst other trades, Garre sell camel milk which is claimed to have various health benefits; this is transported daily to Isiolo town and processed for sale. The Garre also occupy some positions on the board on the Gotu side of the Nakuprat-Gotu wildlife conservancy in the Ngaremara area and some Borana suspect them of using the conservancy concept to increase Garre claims on land in the area.Footnote68 Garre traders have also gained from the newly refurbished Isiolo Moyale Road, dominating trade in Isiolo town and up to Moyale on the Ethiopia border, as one county administrator noted:

The Garre and the Somali are wealthy while the Turkana have no money and they live the furthest [from Isiolo town]. Traditionally, the Turkana have been forced to sell their lands to the powerful and monied Garre and Somali, but with the LAPSSET and more knowledge, Turkana have opened their eyes.Footnote69

People have a lot, so many camels, too much camels that are commercial. (…) You know, if it doesn't rain they go back to the same place again, graze and graze until it becomes overgrazed. Overgrazing means they degrade it.Footnote72

Another response to the growing dominance of the Garre was a public notice that was given by the Borana Council of Elders over local radio in March 2019.Footnote75 Although the Council is not made up of politicians, they wield significant political power. The Council notice said:

Many have forgotten they are our guests … We remind all that the owners of Isiolo county are, and have always historically been Borana … We have … allowed grazing rights to the Garre for a long period but they have not appreciated our kind gesture, rather, they have been both abusive and quarrelsome including dishonoring the community by refusing to attend the meetings called by the Borana Council of Elders. In view of this we demand that the Garre communities move out of our grazing lands with immediate effect.Footnote76

It is important to highlight the political context of these issues that reach up to the regional level. The Garre-Oromo/ Borana competition operates in both Isiolo and Marsabit and the Council of Elders is closely linked with the overarching traditional authority for all Borana, based in Ethiopia. There has been long-standing ethnicized conflict in Moyale town on the Ethiopia side of the border, between Garre and Oromo, so these statements are likely to have political motivationsFootnote78 but LAPSSET is also a factor in inflaming tensions.

Isiolo-Meru boundary conflict

The Isiolo-Meru county boundary (previously the district boundary) is a source of bitter contention, both at the political level and the community level between Meru farmers and Isiolo-based (Borana and Turkana) pastoralists who clash over land. The conflict was severe in 2015 due to political incitement and tensions over which communities would benefit from the proposed LAPSSET project.Footnote79 The conflict takes the form of livestock theft, killings, displacements and looting between the warring communities.Footnote80 The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project captures seven distinct conflicts or incidents from 2015 to 2019 in which there were a total of 33 deaths. This reached a peak in July 2017 with three days of fighting in which 1,000 people were displaced and 13 killed in Igembe Central, Meru.Footnote81 In October of the same year, two people were killed in a massive cattle raid in Tigania East, Meru. Disputed areas along the border include Kiwanji, Gambela, Epiding and Kachuru among others and the newly constructed airport that is situated in both counties.Footnote82 They lie within the approximately 10 by 50 km rectangular area between the mapped Isiolo-Meru boundary and the Isiolo-Madogashe road which runs parallel to it (shaded pale green in ).

Meru representatives have consistently appealed to the colonial boundary demarcation which originated in 1924, but their Isiolo counterparts argue that this itself was erroneously marked and that Isiolo district representatives did not attend the deliberations of a Boundary Commission in 1962 because of a protest related to the Shifta War.Footnote83 The 2013 Nanyuki Accord attended by elected leaders and community leaders of Isiolo and Meru counties sought to calm tensionsFootnote84 and foresaw that the dispute would be resolved through institutional mechanisms.Footnote85 However, agreements were broken and conflict continued. A taskforce under the Ministry of Interior in 2015 surveyed and demarcated boundaries, but was denounced by Isiolo county government as being unrepresentative, tribal and carried out by the wrong office.Footnote86 Then in June 2017, a High Court ruled in Isiolo’s favour, that an independent commission be set up to resolve the dispute, until which point the status quo should remain.Footnote87 However, the ruling was not heeded in practice.

The dispute has been exacerbated by devolution,Footnote88 which has raised the stakes for political control of land, resources and in particular, the planned large-scale developments and airport that lies in both counties.Footnote89 Since 2018, contrary to the court ruling above, the Meru county government has been carrying out land adjudication and giving title deeds in disputed areas. Alliances between local Turkana in favour of titling and Meru have been forged in this way.Footnote90 Although these disputed areas have historically been administered by Isiolo, Meru has now created a ‘special’ ward in Tigania East subcounty of Meru, extending its services to this area with developmental investments like boreholes. In another bold move in 2015, Meru began establishing Nyambene conservancy in the disputed areaFootnote91 and in 2018, stationed armed rangers there as a means of boosting security for some time.Footnote92

Borana elders interviewed voiced anger and fear:

Meru now claim up to Gotu, Ngaremara is their own. They think they will just take. Borana, we are in trouble … The Meru have woken up because of the road; all the jobs, benefits will go to Meru … They want to snatch our land; blood will be poured if they want to take our resources.Footnote93

Territorialized Borana-Somali pastoralist conflict

In addition to the farmers described above, pastoralist groups from neighbouring counties are also perceived by Isiolo residents to be making claims on Isiolo county to get benefits and compensation. Garbatula sub-county (which is made up of Kinna, Garbatula and Sericho wards), has experienced conflicts in recent years connected to both LAPPSET and the Isiolo-Madogashe road plans. Although seasonal migration by Somali pastoralists from Garissa county has been normal, upon negotiation with local Borana pastoralist leaders, there is an expectation that they return to their own lands when rains begin.Footnote97 An administrator in Kinna noted that new settlements have been created on the Isiolo-Modagashe road and these groups have been naming boreholes with their own names, suggesting possible claiming of that land. ‘They are grazing in the area without the opinion leader’s permission. If you complain and speak, they point a gun at you.’Footnote98 Elders in Kulamawe, Kinna ward confirmed this, ‘We have guns from Garissa, guns even they pass here on the road and no one asks. We see we are in danger.’Footnote99

According to ACLED data, the Isiolo-Garissa border area and Garbatulla subcounty has been a site of conflict with many displacements and several deaths since 2016. Hotspots include Madogashe, Mata Bofu, Uchana, and El Dera, Duse and Korbesa in Kinna ward.Footnote100 Some of these are as far as 80 km from the border. The conflict has intensified in 2021 and explosives were being used by Aulihan Somali to launch attacks on Borana settlements in Korbesa at the time of writing in July 2021.Footnote101 These conflicts are not only about pasture and water resources but also about territorial claims which have only recently emerged relating to the anticipation of benefits from the planned improvements to the Isiolo-Madogashe Road.Footnote102 According to government communications, the Borana say that they have been displaced from their villages by their neighbours from Garissa, who have taken over their houses, shops and businesses. Moreover, in one site of conflict known as Escot, Somalis are now attempting to claim compensation for property sacrificed to the road, though they had only recently forced the Borana out of it.Footnote103

Discussion

Anticipatory positioning and the capacity to envision

This research has documented the anticipatory practices, hopes, fears and conflicts of local actors living along the planned LAPSSET Corridor. The Kenyan state expresses a vision of modernity, connectivity, tapping of economic potential, at the same time hoping to remedy the marginalization of the north.Footnote104 The visions by some local entrepreneurs are in line with the official developmental vision, namely visions of business opportunities, effortless earnings from agricultural land that is secured by titles, together with irrigation and farming to supply goods to a growing population, tourism potentials and new markets through the airport.

Arguably, the existing visions span a field of possibilities, in which actors position themselves by anticipating the future. In the short term, some are anticipating compensation payments and jobs relating to LAPSSET construction and tenders. In the long term, visions of the future have important spatial dimensions concerning rural and urban landscapes, and land tenure is a key issue around which divergent visions are framed. Land in pastoralist areas is shifting in significance from being a communal resource to being a commodity to be bought, developed or sold and the subdivision of land opens the way for elites to emerge and grow in economic power while other people are dispossessed.

The abounding hope and grabbing of opportunities was matched by fears and suspicions, of physical, social and economic displacement and cultural estrangement of pastoralists by land grabbing, private land tenure, modernization, and open violent conflicts.Footnote105 The suspicion is captured vividly by a commentator from Northern Kenya: ‘How is the metaphor of negation now the glitzy developmental jewel?[…] hidden in the folds of this grand development vision of LAPSSET is exploitation, oppression and dismissal of the North.’Footnote106 In addition, there are century-old prophecies among the Borana, one by ‘prophet’ Arero Bosaro about a ‘black road [tarmac] that would come from the South, … and when that is complete, there will be problems in the area; there will be a war and the people will be decimated.’Footnote107 Dismissal of these concerns could be felt in some of the interviews with LAPSSET officials:

LAPSSET is a game changer; it’s the biggest project under Vision 2030, and those people in Isiolo resisting the project are stupid […]. They claim they have been marginalized and neglected and when you bring development they complain […] very stupid people.Footnote108

As anticipatory positioning is happening in the present, it follows existing social fissures,Footnote112 often along ethno-political dividing lines.Footnote113 However, social class is another dividing line which may be independent of ethnicity, a finding which is echoed in Cross’s study of an economic zone in India.Footnote114 Thus class and political influence are influential factors in determining both the capacity to envision – in the sense of participating in vision formulation and dissemination – and the capacity to position oneself in anticipation of future economic investments.

From anticipatory positioning to ethnicized conflict

The fear of violence in the county is strong because the history of conflict in Isiolo county similarly played out along intercommunal and ethno-political lines, together with a high presence of firearms among individuals and groups due to a weak state security presence.

In terms of ethnicity, conflicts centre around who is anticipated or feared to gain economically and politically from the new developments, and this also relates to land-tenure differences. LAPSSET and other projects exacerbate pre-existing ethno-political tensions over boundaries, land claims, business opportunities and voting blocks. The Meru-Isiolo county boundary conflict illustrates how actors position themselves in anticipation of LAPSSET – the actions are not guided by positive (yet diverging) visions but by the aim to secure one’s own position and reap the most material benefits for oneself and one’s own camp.Footnote115 The county government has emerged as a major player in the LAPSSET vision as it is the implementing agency of the national government and the new middle agency to negotiate for the local communities. Both county governments clash over which should benefit, and locals clash on an inter-ethnic level over territory.

Interestingly, Borana elites simultaneously oppose land privatization and enclosures as members of parliament who protest against land titling, and pursue ethnicized, exclusive claims via the Borana Council of elders’ statements. In public, leaders of the predominantly pastoralist Borana community tend to take a stance protective of pastoralist mobility across communally managed rangelands, e.g. with regard to the issue of individual titling vs. community land. By publicly affirming their indigeneity and authority over the Isiolo rangelands (practically the Merti rangelands) through the customary system of grazing management, they speak for the silent, uneducated majority and seek to affirm control over the ‘old’ pastoralist order. At the same time, hidden from public scrutiny, some try to acquire land exclusively for themselves as in the case of Gotu. As elites are able to foresee business opportunities and have enough financial clout, they are also tempted to act upon those. All these strategies arguably represent different ways of anticipatory positioning, i.e. attempts to benefit from future investments and to avoid being left behind by other groups seemingly more able to benefit.

Other research in the Isiolo area showed that similar dynamics are happening along the Isiolo-Mandera road, whereby Borana elders are encouraging people to migrate and form group ranches along the road to prevent the occupation by Somali groups previously mentioned. As with other group ranches in the country, there is a danger that this is beginning of the slippery slope to privatization.Footnote116

This implies that while the narrative of ethnicity is used to mobilize people for collective benefits and control over land, it may also be used to further the individual economic and political interests of those in the higher social classes to the exclusion of the larger ethnic group. As elites are more favourably positioned as regards knowledge about future economic developments, suspicions by some local people about who drives those ethnicized conflicts are also directed towards the elites: Traditional cattle-raiding is re-interpreted in the light of the planned LAPSSET corridor with local people asking themselves, ‘Do elites want to displace us through insecurity, to benefit from LAPSSET?’

Conclusion

This article has analysed how people in Isiolo county position themselves in an arising field of opportunities and constraints, a zone of “not yet,” a future that is opened up by Vision 2030 to transform northern Kenya through an infrastructure corridor. This anticipatory positioning is raising fears and heightening the claiming of land and ethnic boundary-making, leading to heightened tensions and exacerbating existing conflicts.

We argue that anticipatory action is informed by different capacities of envisioning. The Kenyan state expresses a vision of modernity, connectivity, tapping of economic potential, at the same time hoping to remedy the marginalization of the north. On the ground some actors share this vision and are enthusiastic for the benefits and opportunities that may be brought by private titling, compensation, markets and industries. However, especially those actors on the ground who did not participate in the vision-making process, mostly express fears for the demise of pastoralism.

Beyond suspicion against the central state, anticipatory action in Isiolo county is informed by existing ethno-political divides and boundaries. Ethno-political divides on a national and regional level become effective at the local and county level, as seen in territorial disputes around Gotu location and the Meru vs Isiolo county and Isiolo vs Garissa boundary conflicts. But at the same time, the actions people take in anticipation of future investments impact on ethnic boundary-making, as division lines are re-enacted (Borana – Somali), contested and redrawn (county boundaries). Conflicts occur on a backdrop of inter-communal and ethnopolitical conflict and are armed and sometimes deadly. Actors are pitted against each other along lines of ethnicity, county and class, implying differentiated political and economic clout and access to information. Lastly, this work shows that while the dynamics of ethnic politics and territorialization are very active surrounding the LAPSSET corridor area, social class, in which the ethnic card may be played, also has an important role in who gains and loses from LAPSSET.

Acknowledgments

This work was first presented in 2019 at the European Conference on African Studies in Edinburgh, UK. Thanks to our research assistants, participants and helpful officials and to the several reviewers for their very useful comments. Thanks also to our driver Laban who got us safely through difficult conditions with a smile, and to Tessa Mkutu for her editing expertise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview, a peace ambassador, Isiolo Town, 6 September 2018.

2 LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, “Brief on LAPSSET” and Browne, LAPSSET.

3 Zelezer, “Economic Policy and Performance.”

4 Government of Kenya, “Vision 2030.”

5 LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, “Investment prospectus,” 5.

6 Scott, “Seeing Like a State.”

7 Bovensiepen and Meitzner Yoder, “Introduction: The Political Dynamics”; Filer and Le Meur “Large-Scale Mines”; and Unruh et al., “Linkages.”

8 Behrends, “Fighting for Oil”; Greiner, “Land-Use Change”; and Kinyera and Doevenspeck, “Imagined Futures.”

9 Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging”; Chome et al., “Demonstration Fields”; and Greiner “Land-Use Change.”

10 Barry, “Material Politics,” 7; Behrends, “Fighting for Oil”; and Kinyera and Doevenspeck, “Imagined Futures.”

11 Mkutu and Mboru, Rapid Assessment.

12 Cormack, “Pastoralist Heritage.”

13 Elliot, “Planning, Property and Plots”; and Elliot, “Anticipating Plots.”

14 Pavitt, Kenya: The First Explorers.

15 Jenkins, “Ethnicity.”

16 Lynch, “Negotiating Ethnicity.”

17 Mkutu et al., Securing the Counties.

18 Carrier and Kochore, “Navigating Ethnicity”; Schlee and Shongolo, Pastoralism and Politics; and Greiner “Land-Use Change.”

19 Jenkins “Ethnicity.”

20 Lonsdale “Soil,” 308.

21 Ibid., 311.

22 Boye and Kaarhus, “Competing Claims”; Schlee and Shongolo, Pastoralism and Politics; and Arero, “Coming to Kenya,” 295–8.

23 Greiner, “Land-Use Change,” 539–40.

24 Whittaker, “The Socioeconomic Dynamics”; and Whittaker, “Legacies of Empire.”

25 Isiolo County Government, “County Integrated Development Plan.”

26 Some Somali clans were earlier considered Boran or self-identified as Boran. Schlee, “Brothers of Boran,”; cf. Schlee “Changing Alliances.”

27 Boye and Kaarhus, “Competing Claims”; and Arero, “Coming to Kenya,” 293.

28 Boye and Kaarhus, “Competing Claims.”

29 Mkutu and Mboru, Rapid Assessment.

30 Mkutu, “Pastoralists, Politics.”

31 Ruto et al., “Conflict Dynamics in Isiolo.”

32 Ibid.; Cox, “Ethnic Violence”; and Sharamo, “The Politics.”

33 Tsing, “Natural Resources and Capitalist Frontiers,” 5100.

34 Cross, “Dream Zones,” 9.

35 Enns and Bersaglio, “On the Coloniality.”

36 Schetter, “Ungoverned Territories.”

37 Harrison and Mdee, “Entrepreneurs”; Mosley and Watson “Frontier Transformations.”

38 Anderson, “Preemption”; Groves, “Emptying the Future”; and Granjou et al., “Politics of Anticipation.”

39 Cross, “Dream Zones,” 9.

40 Haines, “Imagining the Highway,” 406.

41 Hughes and Rogei, “Feeling the Heat.”

42 Greiner, “Land-Use Change,” 541.

43 Government of Kenya, Sessional Paper No. 8.

44 On the different local perspectives on the Isiolo-Moyale road see Kochore, “The Road to Kenya.”

45 See Natural Justice, “LAPSSET Land Acquisition Map.” https://naturaljustice.org/natural-justice-lapsset-land-acquisition-map/

46 Mkutu, “LAPSSET Corridor Developments.”

47 Gitonga Marete, “Building Plans for Sh85bn Isiolo-Mandera Road on the Home Stretch.” Business Daily, February 5, 2020. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/corporate/shipping/Building-plans-for-Sh85bn-Isiolo-Mandera-road-/4003122-5443978-85r75wz/index.html

48 Owino, “The Implications.”

49 Kanyinga, “Devolution.”

50 Owino, “The Implications.”

51 Group interview with journalists, Isiolo Town, 11 May 2017.

52 Lind et al., “The Politics of Land,” 3.

53 Elliot, “Town Making.”

54 Ibid.; and Elliot, Anticipating Plots.

55 Elliot, Anticipating Plots; and Elliot “Town Making,” 51.

56 Peace Committee Member, Isiolo, 10 May 2017.

57 Interview, LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority official 19 February 2019.

59 Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 1, 10 January 2020 “The Land Adjudication Act” (Application)(Amendment) Order

60 Waweru Wairimu, “Turkana Community in Isiolo Wants Land Adjudication Halted.” Daily Nation, January 7, 2020. https://www.nation.co.ke/counties/isiolo/Locals-oppose-Isiolo-land-adjudication/1183266-5409246-d0y894/index.html; Environment and Land Court at Meru. Petition No 5 of 2019; and High Court of Kenya at Meru. Petition No. 7 of 2018.

61 Interview, land adjudication office, 17 June 2019.

62 Interview, Borana Peace Activist, Isiolo, 22 March 2019.

63 Focus group discussion with Interfaith leaders Isiolo town, 8 May 2018.

64 Interview, Borana Peace Activist, Isiolo 22 March 2019.

65 Interview, local administrator in Gotu, 8 September 2018.

66 Interview, Borana Council of Elders, 18 June 2019; Interview, Local administrators, 9 May 2020.

67 Phone interview, a senior county administrator, 16 May 2020.

68 Interview, Borana Council of Elders, 18 June 2019.

69 Interview, county administrator, Isiolo town, 17 October 2018; Interview, Borana Peace Activist, Isiolo 22 March 2019.

70 Interview, an administrator in Gotu, Gotu, 8 September 2018: This was supported by an interview with a senior administrator in Isiolo, 5 May 2020.

71 Phone interview, officer for Parliamentary Service Commission, Isiolo North Constituency office, Isiolo, 23 April 2020.

72 Interview, Borana Council of Elders, 18 June 2019.

73 Phone Interview, Group ranch leader, June 2019.

74 Interview, board member of Nakuprat-Gotu conservancy 8 September 2018.

75 Interview, Borana Council of Elders, 18 June 2019; The Borana Council of Elders was created in 2006 to have a national political organ that brings together all different Borana clans and their traditional institutions that manage all aspects of Borana society.

76 Borana Council of Elders, “Resolution of the Borana Council of Elders.” Slides shared on 12 March 2019 in Isiolo Town. This was broadcast on local radio. https://www.slideshare.net/oskare10/borana-council-of-elders (Accessed 11 May 2020).

77 Phone interview, a senior county administrator, 16 May 2020.

78 Phone interview, a senior county administrator, 16 May 2020; see also Vivian Jebet, “Somali Elders Back Senator Kuti’s Bid for Isiolo Governor.” Daily Nation, April 7, 2017. https://www.nation.co.ke/counties/isiolo/Somali-elders-back-Kuti-Isiolo/1183266-3880822-phrfqnz/index.html

79 F. Ngige and A. Abdi, “Is LAPSSET Cause of the Bloody Conflict Along Meru/Isiolo Border?” The Standard, November 1, 2015. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2000181277/is-lapsset-cause-of-the-bloody-conflict-along-meru-isiolo-border; and Owino “The Implications.”

80 Mugo, “Gov’t Challenged.”

81 Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED.”

82 Interview, an official in the office of, Coordination Civic Education, County Cohesion Department, Isiolo, 17 October 2018.

83 High Court of Kenya, Constitutional Petition No. 551

84 Ibid.

85 Resolutions of the Meru/Isiolo leaders meeting held at Sportsman Arms Hotel, Nanyuki, 20 December 2013.

86 High Court of Kenya, Constitutional Petition No. 551.

87 Ali Abdi, “Land Row Rocks Isiolo and Meru as Residents Blame Rift on Lapsset, Army.” The Standard, August 18, 2018. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001292364/land-row-rocks-isiolo-and-meru-as-residents-blame-rift-on-lapsset-army (Accessed 14 November 2018)

88 Kanyinga, “Devolution.”

89 Ibid.

90 Phone interview, Community leader in Ngaremara, 16 May 2020.

91 Kimanthi and Mwiti, “Leaders Clash.”

92 Interview, an administrator for civic education, County Cohesion Department, Isiolo, 17 October 2018.

93 Focus Group Discussion with Borana elders in Kula Mawe, 18 October 2018.

94 Interview, Somali businessman in Isiolo Town, 2019; a county administrator in Ngaremara suggested something similar.

95 Senior County Administrator, Isiolo Town, 17 October 2018.

96 Meru County Government, “County Integrated Development Plan.” See also Hillary Megaka, “Stop claiming our electoral boundaries, Isiolo MPs tell Meru Governor.” People Daily, November 13, 2019. https://www.pd.co.ke/news/politics-analysis/stop-claiming-our-electoral-boundaries-isiolo-mps-tell-meru-governor-13199/

97 Phone interview, peace activist, 10 July 2020.

98 Interview, sub-county administrator in Kinna, 18 October 2018

99 Focus Group Discussion with elders in Kula Mawe, 15 October 2018.

100 Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED.”

101 Interviews and observations of burned ground, 9 July 2021.

102 Interview, officer in Parliamentary Service Commission, Isiolo North Constituency office, Isiolo, 20 October 2018.

103 See Letter dated 12 June 2021 from Peace Chairman for Garbatulla to Deputy County Commissioner for Garbatulla “Protest on land owenership at Kambi Samaki (Uchana)” and Letter LND.16/1/VOL.1/102 dated 21 June 2021, from Deputy County Commissioner for Garbatulla to the County Commissioner for Isiolo county. “Protest over NLC compensation on Isiolo-Modogashe rd”.

104 Hesse and MacGregor, “Pastoralism: Drylands Invisible Asset?”

105 Cf. Enns and Bersaglio, “The Coloniality.”

106 Dalle Abraham, “The New Frontier for Development and the Politics of Negation in Northern Kenya.” The Elephant, November 15, 2019. https://www.theelephant.info/features/2019/11/15/the-new-frontier-for-development-and-the-politics-of-negation-in-northern-kenya/

107 Kochore, “Road to Kenya,” 505.

108 Interview, LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority official 19 February 2019.

109 Elliot, “Planning, Property and Plots”; Cf. Li, “Indigeneity, Capitalism, Dispossession.”

110 Li, “Centering Labour”; and “Ethnic Cleansing.”

111 Elliot, “Town Making.”

112 Cf. Szpunar et al., “Neural Envisioning”: Results from neuroscience suggest that humans appear to place their future scenarios in well-known visual–spatial contexts.

113 Cf. Chome, “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging.”

114 Cf. Cross, “Dream Zones.”

115 Cf. Odhiambo’s distinction between two different attitudes to politics among the new Kenyan political elite following independence, with former President Kenyatta representing the mentality to enjoy the fruits of independence by accumulation of personal wealth vs. the faction led by Tom Mboya, who were interested in developing a political vision by reflecting on the purpose of independence and strategies for achieving this. Odhiambo, “The Ideology of Order,” 195.

116 Mkutu, “Anticipation, Participation, and Contestation.”

Bibliography

- Anderson, Ben. “Preemption, Precaution, Preparedness: Anticipatory Action and Future Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 34, no. 6 (2010): 777–798. doi:10.1177/0309132510362600.

- Arero, Hassan Wario. “Coming to Kenya: Imagining and Perceiving a Nation among the Borana of Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 1, no. 2 (2007): 292–304. doi:10.1080/17531050701452598.

- Barry, Andrew. Material Politics: Disputes Along the Pipeline. Oxford: Wiley, 2013.

- Behrends, Andrea. “Fighting for Oil When There is No Oil Yet: The Darfur-Chad Border.” In Crude Domination: An Anthropology of Oil, edited by Andrea Behrends, Stephen Reyna, and Günther Schlee, 81–106. New York: Berghahn, 2011.

- Bovensiepen, Judith, and Laura S. Meitzner Yoder. “Introduction: The Political Dynamics and Social Effects of Megaproject Development.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 19, no. 5 (2018): 381–394. doi:10.1080/14442213.2018.1513553.

- Boye, Saafo Roba, and Randi Kaarhus. “Competing Claims and Contested Boundaries: Legitimating Land Rights in Isiolo District, Northern Kenya.” Africa Spectrum 46, no. 2 (2011): 99–124. doi:10.1177/000203971104600204.

- Browne, Adrian J. LAPSSET: The History and Politics of an Eastern African Megaproject. Rift Valley Forum. Nairobi: Rift Valley Institute, 2015.

- Bruun Jensen, Casper, and Atsuro Morita. “Infrastructures as Ontological Experiments.” Ethnos 82, no. 4 (2016): 615–626. doi:10.1080/00141844.2015.1107607.

- Carrier, Neil, and Hassan H. Kochore. “Navigating Ethnicity and Electoral Politics in Northern Kenya: The Case of the 2013 Election.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8, no. 1 (2014): 135–152. doi:10.1080/17531055.2013.871181.

- Chome, Ngala, Euclides Gonçalves, Ian Scoones, and Emmanuel Sulle. “‘Demonstration Fields’, Anticipation, and Contestation: Agrarian Change and the Political Economy of Development Corridors in Eastern Africa.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14 2 (2020): 291–309. doi:10.1080/17531055.2020.1743067.

- Chome, Ngala. “Land, Livelihoods and Belonging: Negotiating Change and Anticipating LAPSSET in Kenya’s Lamu County.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 14, no. 2 (2020): 310–331. doi:10.1080/17531055.2020.1743068.

- Cormack, Zoe. “The Promotion of Pastoralist Heritage and Alternative ‘Visions’ for the Future of Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 548–567.

- Cox, Fletcher D. “Ethnic Violence on Kenya’s Periphery: Informal Institutions & Local Resilience in Conflict Affected Communities.” PhD diss., University of Denver, 2015.

- Cross, Jamie. “The Economy of Anticipation: Hope, Infrastructure, and Economic Zones in South India.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35, no. 3 (2015): 424–437. doi:10.1215/1089201X-3426277.

- Cross, Jamie. Dream Zones: Anticipating Capitalism and Development in India. London: Pluto Press, 2014.

- Elliot, Hannah. “Anticipating Plots: (Re)Making Property, Futures and Town at the Gateway to Kenya’s ‘New Frontier’.” PhD thesis, Centre of African Studies, University of Copenhagen, 2018.

- Elliott, Hannah. “Planning, Property and Plots at the Gateway to Kenya’s New Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 511–529. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266196.

- Elliot, Hannah. “Town Making at the Gateway to Kenya’s ‘New Frontier’.” In Land, Investment and Politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands, edited by Jeremy Lind, Doris Okenwa, and Ian Scoones, 43–54. Woodbridge: James Currey, 2020.

- Enns, Charis, and Brock Bersaglio. “On the Coloniality of ‘New’ Mega-Infrastructure Projects in East Africa.” Antipode 52, no. 1 (2019): 101–123. doi:10.1111/anti.12582.

- Filer, Colin, and Pierre-Yves Le Meur, eds. Large-Scale Mines and Local-Level Politics: Between New Caledonia and Papua New Guinea. Acton: Australian National University Press, 2017.

- Government of Kenya. “National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Northern Kenya and Other Arid Lands.” Sessional Paper No. 8 (2012). Nairobi: Government Printers, 2020.

- Government of Kenya. “Vision 2030 First Medium Term Plan (2008–2012).” Nairobi: Government Printers, 2008. http://vision2030.go.ke/inc/uploads/2018/06/kenya_medium_term_plan_2008-2012-1.pdf.

- Greiner, Clemens. “Land-Use Change, Territorial Restructuring, and Economies of Anticipation in Dryland Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 530–547. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266197.

- Haines, Sophie. “Imagining the Highway: Anticipating Infrastructural and Environmental Change in Belize.” Ethnos 82, no. 2 (2018): 392–413. doi:10.1080/00141844.2017.1282974.

- Harrison, Elizabeth, and Anna Mdee. “Entrepreneurs, Investors and the State: The Public and the Private in Sub-Saharan African Irrigation Development.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 11 (2018): 2126–2141. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1458299.

- Hesse, Ced, and James MacGregor. “Pastoralism: Drylands’ Invisible Asset? Developing a Framework for Assessing the Value of Pastoralism in East Africa.” Issue Paper 142. London: IIED, 2006. https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/12534IIED.pdf.

- High Court of Kenya. “Constitutional Petition No. 551 of 2015: County Government of Isiolo & 10 others v Cabinet Secretary, Ministry of Interior and Coordination of National Government & 3 others [2017] eKLR.” High Court of Kenya. Accessed November 14, 2018. http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/137183/.

- Hughes, Lotte, and Daniel Rogei. “Feeling the Heat: Responses to Geothermal Development in Kenya’s Rift Valley.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 2 (2020): 165–184. doi:10.1080/17531055.2020.1716292.

- Isiolo County Government. “Isiolo County Integrated Development Plan Isiolo, CIDP 2018–2022. Making Isiolo Great.” Isiolo: Isiolo County Government, 2018.

- Jenkins, Sarah. “Ethnicity, Violence, and the Immigrant-Guest Metaphor in Kenya.” African Affairs 111, no. 445 (2012): 576–596.

- Kanyinga, Karuti. “Devolution and the New Politics of Development in Kenya.” African Studies Review 59, no. 3 (2016): 155–167. doi:10.1017/asr.2016.85.

- Kimanthi, Kennedy, and Dickson Mwiti. “Kenya: Leaders Clash Over Meru Conservancy.” Daily Nation, July 13, 2015. Accessed October 4, 2021. allafrica.com/stories/201507132616.html.

- Kinyera, Paddy, and Martin Doevenspeck. “Imagined Futures, Mobility and the Making of Oil Conflicts in Uganda.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 13, no. 3 (2019): 389–408. doi:10.1080/17531055.2019.1579432.

- Kochore, Hassan H. “The Road to Kenya?: Visions, Expectations and Anxieties Around New Infrastructure Development in Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 494–510. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266198.

- LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority. “Brief on LAPSSET Corridor Project.” Nairobi: LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, 2016. http://vision2030.go.ke/inc/uploads/2018/05/LAPSSET-Project-Report-July-2016.pdf.

- LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority. “Investment Prospectus.” Nairobi: The Presidency and LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, 2015. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7w3900K6lYnNl8xZ1VidWM2NVE/view.

- Li, Tania M. “Centering Labor in the Land Grab Debate.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 38, no. 2 (2011): 281–298. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.559009.

- Li, Tania M. “Ethnic Cleansing, Recursive Knowledge, and the Dilemmas of Sedentarism.” International Social Science Journal 54, no. 173 (2002): 361–371. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00388.

- Li, Tania M. “Indigeneity, Capitalism, and the Management of Dispossession.” Current Anthropology 51, no. 3 (2010): 385–414. doi:10.1086/651942.

- Lind, Jeremy, Doris Okenwa, and Ian Scoones. “The Politics of Land, Resources & Investment in Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands.” In Land Investment & Politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands, edited by J. Lind, D. Okenwa and I. Scoones, 1–32. Suffolk: James Currey, 2020.

- Lonsdale, John. “Soil, Work, Civilisation, and Citizenship in Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 2, no. 2 (2008): 305–314. doi:10.1080/17531050802058450.

- Lynch, Gabrielle. “Negotiating Ethnicity: Identity Politics in Contemporary Kenya.” Review of African Political Economy 33, no. 107 (2006): 49–65.

- Meru County Government. “Meru County Integrated Development Plan 2018–2022.” Meru: Meru County Government, 2018. http://meru.go.ke/lib.php?com=6&com2=33&&res_id=885.

- Mkutu, Kennedy, and Abdullahi Halakhe Mboru. Rapid Assessment of the Institutional Architecture for Conflict Resolution in Isiolo County, Kenya. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2019.

- Mkutu, Kennedy. “Anticipation, Participation, and Contestation along the LAPSSET Infrastructure Corridor in Kenya” Working Paper. Bonn: Bonn International Center for Conversion, 2021.

- Mkutu, Kennedy. “LAPSSET Corridor Developments and Conservation Areas in Samburu County.” Bonn: Bonn International Center for Conversion, 2020. Unpublished.

- Mkutu, Kennedy. “Pastoralists, Politics and Development Projects: Understanding the Layers of Armed Conflict in Isiolo, Kenya.” Working Paper 7. Bonn: Bonn International Center for Conversion, 2019.

- Mkutu, Kennedy, Martin Marani, and Mutuma Ruteere. Securing the Counties: Options for Kenya After Devolution. Nairobi: Centre for Human Rights and Policy Studies, 2014.

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199.

- Owino, Evelyne A. “The Implications of Large-Scale Infrastructure Projects to the Communities in Isiolo County: The Case of Lamu Port South Sudan Ethiopia Transport Corridor.” MA thesis, United States International University-Africa, 2019.

- Pavitt, Nigel. Kenya: The First Explorers. London: Aurum Press, 1989.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED: Armed Conflict Location Event Data.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–660.

- Rasmussen, Mattias B., and Christian Lund. “Reconfiguring Frontier Spaces: The Territorialization of Resource Control.” World Development 101 (2018): 388–399. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.018.

- Ruto, Dominic, Kyalo Musoi, Irene Tule, and Benard Kirui. “Conflict Dynamics in Isiolo, Samburu East and Marsabit South Districts of Kenya.” Amani Papers 1, no. 3. Nairobi: UNDP Kenya, 2010. https://www.ke.undp.org/content/dam/kenya/docs/Amani%20Papers/AP_Volume1_n.7.pdf.

- Schetter, Conrad. “Ungoverned Territories – The Construction of Spaces of Risk in the ‘War on Terrorism’.” In Spatial Dimension of Risk, edited by Detlef Müller-Mahn, 97–108. London: Earthscan, 2012.

- Schlee, G., and A. Shongolo. Pastoralism and Politics in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia. Woodbridge: James Currey, 2012.

- Schlee, Günther. “Brothers of the Boran Once Again: On the Fading Popularity of Certain Somali Identities in Northern Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 1, no. 3 (2007): 417–435. doi:10.1080/17531050701625524.

- Scott, James. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Binghamton, NY: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Sharamo, Roba. “The Politics of Pastoral Violence: A Case Study of Isiolo County, Northern Kenya.” Working Paper 095. Brighton, UK: Future Agricultures Consortium, 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a089c4ed915d3cfd000408/FAC_Working_Paper_095.pdf.

- Tsing, Anna L. “Natural Resources and Capitalist Frontiers.” Economic and Political Weekly 38, no. 48 (2003): 5100–5106. doi:10.2307/4414348.

- Unruh, Jon, Matthew Pritchard, Emily Savage, Chris Wade, Priya Nair, Ammar Adenwala, Lowan Lee, Max Malloy, Irmak Taner, and Mads Frilander. “Linkages Between Large-Scale Infrastructure Development and Conflict Dynamics in East Africa.” Journal of Infrastructure Development 11, no. 1-2 (2019): 1–13. doi:10.1177/0974930619872082.

- Whittaker, Hannah. “Legacies of Empire: State Violence and Collective Punishment in Kenya’s North Eastern Province, c. 1963-Present.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43, no. 4 (2015): 641–657. doi:10.1080/03086534.2015.1083232.

- Whittaker, Hannah. “The Socioeconomic Dynamics of the Shifta Conflict in Kenya, c. 1963–8.” Journal of African History 53, no. 3 (2012): 391–408. doi:10.1017/S0021853712000448.