ABSTRACT

In this article, we attempt to understand the persistence of the ‘great tradition’ in describing what the state means to Ethiopians. We do this by examining stories about history, told by and about Ethiopia’s architecture. Within these stories we find two ideas in apparent tension. One is an attachment to state history as exceptional, unified and ordained by God. This is told through architectural continuities reaching back to the pre-Christian Aksumite aesthetic that continuously underwrites the notion of a teleological progression of the state; and in current nostalgia for the assertive certainty of exceptionalism expressed in ancient architecture. The other is an acknowledgement of hybridity and disruption. This is expressed in innovative architectural aesthetics and techniques; and in the ways that state buildings have been made to carry the marks of dramatically different types of regime, particularly in the last 50 years. Drawing on the sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ or ‘wax and gold’) tradition we show how these stories-in-tension describe ambiguities within the great tradition, a story of confidence and exceptionalism, but also one that is disturbed and shaped by rupture and compromise.

This article joins an important debate about Ethiopia’s ‘great tradition’,Footnote1 a problematic approach to history that nevertheless remains pervasive. The great tradition can be traced back to the thirteenth century holy book, Kabra Negast (ክብረ ነገሥት or Book of the Glory of the Kings), but became a dominant Ethiopian historiographic narrative in the nineteenth century.Footnote2 It employs archaeological and material representations such as fossil remains, material inscriptions and architecture to reproduce ideas of a teleological state history. It has been criticised for creating a ‘common-sense’, top-down account of modernisation that overlooks geographical and cultural differences, explaining history as an Amhara-highland-driven state project.Footnote3 It is further criticised for reading a nationalist history backwards, with an ‘emphasis on concepts of continuity, indigeneity, and unity’.Footnote4 As Sorenson puts it, Ethiopia’s nationalist history tends ‘toward a process of retrospective projection that defines the existing national self not as a created product of historical change but as the enduring and constant subject of history … Antiquity confers authenticity’.Footnote5 Radical scholars have critiqued the great tradition as elite-centredFootnote6 and scholars who stress non-hegemonic ethnic perspectives have taken issue with its contribution to ethnic marginalisation and regional dissent.Footnote7 Even the dramatic ruptures of recent history itself – including Italian occupation, the overthrow of the monarchy, and then of the Marxist regime that replaced it, as well as regional conflicts, ethnic tension and recent civil war – have apparently failed to substantially undermine it: the great tradition has ‘remained quite astonishingly immune to upheavals’.Footnote8

We are not interested in deciding here whether the great tradition provides a ‘reliable’ version of history. Instead, we attempt to understand how and why it endures in the face of academic challenge and political upheaval; and from there, to better understand the story it tells of the state.

In order to do this, we examine one of its most dramatic expressions: Ethiopian architecture.Footnote9 Ethiopia’s monumental political and religious structures are regularly used to trace the country’s history, serving as material markers of the movement and evolution of the Ethiopian state, establishing a chronological sequence that has tended to stress continuity. The buildings are used to map and represent key moments in Ethiopian history, from the repurposing of ancient stelae during the embrace of Christianity at Aksum in the fourth century CE,Footnote10 through the enshrinement of a particular church-state relationship in the remarkable stone churches at Lalibela in the twelfth century,Footnote11 the settlement of political authority in the seventeenth-century castles of Gondar,Footnote12 the birth of Addis Ababa as capital city around Menelik’s nineteenth-century palaces,Footnote13 to Haile Selassie’s twentieth-century architecturally innovative buildings,Footnote14 their appropriation during the Marxist revolution from 1974,Footnote15 and the modernist architecture projects of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EDPRF) and current regime of Prime Minister Abiy AhmedFootnote16 – with a sprinkling of Italian imperial architecture thrown in along the way.Footnote17 The latest example of architectural history mapping lies in Unity Park, opened in late 2019, which describes the evolution of the modern state through Addis Ababa’s imperial palaces which were once home to emperors, later adapted for military rule, and now used to showcase Ethiopia’s ethnic diversity.

In this article, we make the buildings the object of attention, rather than taking them as mere illustrations of the historical story of Ethiopian statehood.Footnote18 We focus on state-meaning rather than state history per se: we want to understand how meanings of the state are built on top of readings of its history. We do this through an examination of the buildings’ stories about the history of the state, exploring stories from two sources. First are the stories ancient buildings tell themselves – we examine their aesthetics (materials, designs, cultural and historical references) to find out what they say about the progress and shape of the Ethiopian state. We do this to explore their role in the construction of the great tradition. Second are the stories that Ethiopians tell about their state buildings – how they describe them and understand them as representations of the Ethiopian state.

Within both sets of stories, we find two ideas in apparent tension. One is an attachment to exceptionalism, continuity and teleological state progress. This is told through architectural continuities reaching back to the Aksumite aesthetic; and in nostalgia for the assertive certainty of exceptionalism apparently expressed by ancient architecture. Such stories emphasise the spiritual origins of the country and the close ties between God and state.Footnote19 The other is an acknowledgement of disruption and ambiguity. This is found in stories of innovation, the adoption of foreign techniques, the disturbing aesthetic differences created by Ethiopia’s ethnic groups and the ways that state buildings carry the marks of dramatically different regimes. These stories have more to say about human agency and the ways in which it has shaped the country’s history and the nature of the state. In other words, attachment to the great tradition appears to sit alongside a profound questioning of it.

In order to explain these stories-in-tension, we employ what Mohammed Girma describes as the ‘dualism’ found in Ethiopia’s historiography, and explore it in terms of the sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) – ‘wax and gold’ – poetic form.Footnote20 Sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) lays bare tensions between earthy ephemera and spiritual truth. Some readings describe it as an approach to distilling truth,Footnote21 but others use it as a way to understand the power of ambiguity.Footnote22 Here, counter-narratives make space for human agency, contingency and missteps in shaping Ethiopian history. Our stories about buildings trace ambiguity throughout the great tradition, showing in particular the role of materiality in giving a shape to this history. The state itself emerges as far more contingent and susceptible to historical events and ideas – to human agency – than more rigid versions of Ethiopian history.

The rest of the article is in three parts. The first concentrates on the stories told by ancient buildings, set within the conceptual framing of the ‘wax and gold’ tradition. We describe the aesthetics of some of Ethiopia’s most iconic historical architecture: the Aksum stelae, the Lalibela churches and the Gondar castles, gathered on a fieldtrip to the sites in 2020 and drawing on architectural plans of some of the buildings. We explore their forms and defined spaces, tracing the signs of continuity and disruption between them, to establish ideas of a complex great tradition. In the second part, we explore the work that these stories accomplish, how they are complicated by new buildings, and how they enable people to constitute and question the state. We focus on stories about buildings told by Ethiopian citizens, gathered in a series of 16 focus group discussions (FGDs) held in Addis Ababa in February 2020. These discussions of state buildings are used to explain the shape and idea of the Ethiopian state through descriptions, stories, emotional reactions and analogy.Footnote23 Finally, we conclude with reflections on the role of the great tradition in Ethiopia’s state meaning.

Ambiguities in the built great tradition

Material relics are often used in stories about the evolution of civilisations and the construction of historically shared identity, mobilised to ‘invent traditions’.Footnote24 Ethiopia follows this tradition – in style. Its historical range reputedly includes the remains of the earliest known ancestor of human kind, Dinkinesh or Lucy (the basis of its claim to call itself the place of the ‘birth of humanity’), and ownership of the Ark of the Covenant, brought to Aksum by Menelik, son of the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (the basis of claims of the Ethiopian monarchy’s direct descent from God).Footnote25 Buildings play a prominent role in describing this evolution, articulating a diachronic progression and unity of the state. Three sites are particularly important in this account. At Aksum, a set of funerary stelae mark the beginning of a highly organised state polity.Footnote26 At Roha (now Lalibela), the capital of the Zagwe dynasty, a group of churches hewn out of rock and erected as a ‘new Jerusalem’ cement a profound relationship between state and church. And at Gondar, a series of castles monumentalise the medieval state. This material construction of a ‘great tradition’ has enabled the idea of the state as a cultural monolith unfolding over time. It has deep cultural resonance in its ability to articulate and reify popular perceptions of the past; representations of these buildings are distributed as souvenirs, posters, postcards, in school textbooks, and imagery from them has been used to lend legitimacy to modern state institutions, including high-modernist structures built by Italian, imperial and EPRDF regimes in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.Footnote27 These visual and textual forms represent a crucial source of symbolic power, implicit in which is an idealised construction of state power.Footnote28

Yet the buildings themselves, while supporting this narrative, contain a more complex and ambiguous set of stories. In order to understand them, we begin with what Mohammed Girma calls the ‘dualism’ found in Ethiopia’s historiography which he describes in terms of the sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) – ‘wax and gold’ – poetic form. This complex analogy, derived from various historical influences and texts, was originally used in Ethiopic Geez qine (ቅኔ), poems with double meanings, and lives on in religious teaching (in Geez)Footnote29 and in modern Amharic and Tigrinya.Footnote30 It is, according to Mohammed, ‘more than just a literary system; it is an expression of a way of thinking’.Footnote31 Writing about Amharic poetry, Levine explains that sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) is ‘built of two semantic layers. The apparent, figurative meaning of the words is called “wax”; their more or less hidden actual significance is the “gold”.’Footnote32 Mohammed writes that ‘wax is a natural secretion of gold, produced during the process of purification. Wax, is an element that covers gold. In order to get the purest gold, it needs to be melted in fire’.Footnote33 This means, that:

As a knowledge system, this tradition made society understand reality as a divine ordination surrounded by mystery. It sees the material dimension of reality as an obstruction to understanding reality in its truest sense … it is a paradigm in which the spiritual and hidden meaning has an upper hand over the manifest meaning. The role of a philosopher, therefore, is to peel off, as it were, the ‘wax’ (the manifest meaning) in order that the ‘gold’ (the hidden and true meaning) be discovered.Footnote34

The first characteristic stems from its Platonic influence. Plato posits two realms of human experience – the false world of shadows where most people live and the world of truth available to philosophers.Footnote35 Sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) echoes this elevation of the spiritual over the material world. The ‘gold’ describes the spiritual world, the hidden truth. However, the manifest, physical world – the ‘wax’ – deceitfully assumes the ‘transcendent and boundless power of God’, giving it ‘pretension to self-sufficiency’ which then distorts ‘the thinking of human beings’.Footnote36 As a result, Mohammed argues, materiality and labour have traditionally been seen in Ethiopia as debased, ‘discouraged in preference to a reliance on the covenantal promise to deliver social and economic betterment without human effort’.Footnote37

The second characteristic emphasises the transient nature of the material-wax compared to the spiritual-gold. According to Messay Kebede, normal conceptions of time are ‘cyclical’ and essentially trivial, like ‘wax’. More important is ‘teleological time’ which is related to God and represented by the underlying ‘gold’.Footnote38 As Messay puts it, there is a clear difference between ‘the deep sense of the fleeting nature of things, of a reversal of fortunes and positions [and] of the absolute dependence of all things on God’.Footnote39

The dichotomies represented by sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) – material-spiritual and transient-eternal – tend therefore to deny the importance of human agency and creativity in shaping history in a meaningful way. This presents us with an immediate problem: how are – how can – material buildings made by humans be co-opted into the service of the great tradition? This question leads us to a final characteristic of the ‘wax and gold’: ambiguity.

Donald Levine focuses on the linguistic ambiguities in sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) poems that tell two stories, apparent and hidden. Ambiguity is the hallmark of literary excellence, but more broadly ‘patterns the speech and outlook of every Amhara. When he talks his words often carry double-entendre as a matter of course; when he listens, he is ever on the lookout for latent meanings and hidden motives’.Footnote40 It becomes a way to safely poke fun at, and holes in, official narratives – because meaning is ambiguous, its subversiveness can be overlooked or excused because of its cleverness.Footnote41

There are different responses to Levine’s focus on ambiguity. Messay is dismissive: ‘on the subject of who rules, who has authority, no attenuation or ambiguity of whatever kind is customary … the frankness, firmness, and ostentation of power are appreciated’.Footnote42 But Mohammed’s is a more nuanced reading. He writes that ambiguity is useful ‘to take the incoming (foreign) ideas … to legitimize the popular grand story, rather than scrutinizing it … beliefs, literature and ideologies are adapted, modified, added and subtracted to fit the philosophical status quo’.Footnote43 New ideas can only be rationalised and domesticated within the great tradition if there is some flexibility in it. However, in Mohammed’s final analysis, the great tradition remains dichotomous because the ‘wax and gold’ paradigm does not leave new ideas unaccounted for but deals with them through domestication or excommunication.Footnote44

We attempt to delve deeper into ambiguity, building on Sara Marzagora’s suggestion that the great tradition contains a counter-narrative ‘based on anti-triumphalist ideas of failure’.Footnote45 In other words, subversive ideas might not be ‘domesticated’ or ‘excommunicated’ in the way Mohammed suggests but create tension within the great tradition itself. The buildings’ centrality to the great tradition – a material telling of a spiritually-guided story – seems like a good place to begin.

Aksum to Lalibela: laying down the ‘gold’

Archaeological evidence shows that Aksum long predates Christianity, but the city is held to be the place of Ethiopia’s church-state origin.Footnote46 Its enduring influence is underpinned by its role as keeper of the True Ark of the Covenant, a sacred object that confers on Ethiopia the status of the ‘chosen people’.Footnote47 Although Lalibela and Gondar were later established as rival centres of power, both deferred to Aksum’s dominion over religious affairs (emperors travelled to Aksum to be crowned into the Gondarian era and the practice was briefly revived by Yohannes IV in 1872).

Little is known about the sophisticated technology that was used to quarry, shape, transport and erect the Aksumite stelae, monolithic granite pillars believed to date from 5000 to 2000 BCE. The stelae facade decorations appear to represent contemporary construction techniques, depicting layers of geometrical, stylised features including false doors, windows and monkey-head details ().Footnote48 They boast of the existence of multi-storey dwellings, the height of which could not have been more than two storeys, amplified to some 24 storeys in a display of high ambition and technical skill.Footnote49

Aksum, with its direct link to God, represents the spiritual foundation for Ethiopia’s state-journey. The stelae’s materiality is mysterious: no one knows how or why they were made, a factor that helps remove ideas of human labour from their creation. Their power lies in their role as witness to, and repurposing on the arrival of Christianity, implying a pivotal place in teleological time.

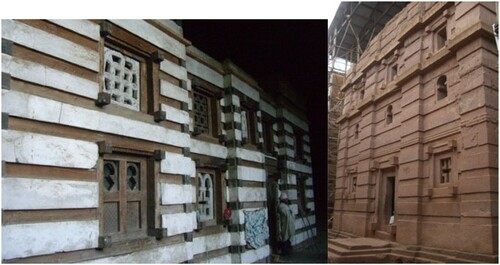

Although Lalibela’s development was arguably an attempt to rival Aksum’s importance as the religious centre, it deferred to its predecessor architecturally. Its submerged rock-hewn churches employ different methods, but create visual similarities of surface undulations, door and window patterns in an extension of Aksumite ideas, esatablishing an ‘ongoing Ethiopian Architectural Tradition’.Footnote50 For example, the Bete-Amanuel Church appears like a rock-hewn copy of a typical two-story Aksumite temple or palace, with visual connections through the use of horizontal divisions and door and window details. The Church of Yimrahana Kiristos, 19km from the Lalibela churches, was built in the Aksumite style inside a cave and has horizontal wooden beam elements that create undulating surfaces, door and window details (). A further illustration of continuity is the use of the projecting beams known as monkey-heads found throughout Lalibela. In Aksumite architecture wooden beams cross the top of buildings and project from the outer surfaces of walls, exposing their heads. In the Lalibela churches, monkey-heads are carved from the rock and are skeuomorphic – they signal a deliberate reference to older technologies rather than their continued functional use.

Figure 2. The Churches of Bete-Amanuel and Yimrahana Kiristos. Photographs by Atnatewos Melake-Selam.

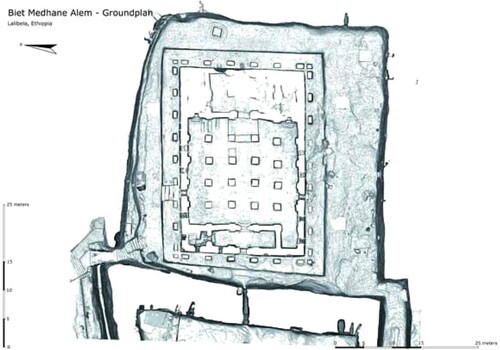

In addition to the obvious visual connections, internal spaces accommodate specialised religious functions that can be traced back to the ruins of Aksumite churches.Footnote51 According to Salvo, the tripartite plan, shared by the whole of the Paleo-Christian enclave, also characterises the Temple of Jerusalem according to descriptions in the Book of Kings.Footnote52 The spaces are hierarchical, organised around the Qene-Mahlet (ቅኔ ማኅሌት or chant of praise), reserved for the congregation; Qeddest (ቅድስት or saint), designated to non-officiating clergy and used for giving the eucharist to the congregation; and Meqdes (መቅደስ or sanctuary), reserved for priests, where the liturgy is celebrated and where the tabots are kept in line with biblical order. A plan of Medhani-Alem, believed to be a copy of the Old Church of St Mary of Tsion at Aksum,Footnote53 illustrates arrangements for specialisation of function with a nave, four aisles and four rows of seven pillars ().

Figure 3. Plan of the Church Medhani-Alem – Created by the Zamani Heritage Documentation Research Project, University of Cape Town, and used with their permission (www.zamaniproject.org).

Great importance is attached to the unbroken lineage of these spaces and their accompanying rituals which are carried out in much the same ways as they were originally in Christian Aksum. They thus appear to embody the unfolding of the spiritual state-story building on authority from Aksum’s Christian origins.

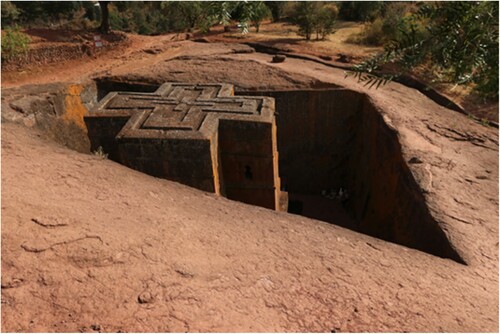

However, the Lalibela churches also contain variations in style and structure. For example, there is a sense of harmonic discontinuity in the case of the most famous church, Bet-Giyorgis, which is centrally planned, forming the Greek Cross (). Not only is it different in form, but it has a ‘flowering’Footnote54 ornamentation window decoration which is different from the geometrical shaping or structural detailing employed in most other windows at Lalibela. With suggestions that King Lalibela visited Jerusalem, it is unsurprising that some historians trace architectural connections to Constantine’s church, Anastasis (Holy Sepulchre)Footnote55 which, according to Ethiopian tradition, is also the church where Aksum’s King Kaleb sent his crown when he abdicated.Footnote56

Borrowings from Jerusalem thus draw on extended sources to consolidate the spiritual and thereby political power of the state. The churches are anchored in cosmological conceptions that emanate from the spatial significance of Jerusalem as a ‘navel of the earth’ connecting it to heaven. The churches imagine Jerusalem in Ethiopia, and Christianity as a cosmic organising principle of the Ethiopian state. Thus, innovations are folded into the story begun at Aksum; as Mohammed suggests, ambiguity is absorbed and resolved within the overarching narrative of the Christian state’s progress.

On top of this careful placement within the teleological unfolding of the holy-state story, the Lalibela churches embody ‘gold’ through their transcendence of materiality. They do this physically and through legend. Physically the churches are the antithesis of monumentalism, buried in the ground. Their relative invisibility emphasises the importance of spiritual over worldly expressions of power, a reflection of the cosmological scheme of sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ). This theme continues inside with spaces arranged into interrelated layers of outwardly visible spaces that are readily accessible to everyone and subterranean, unseen and forbidden domains – the Holy of Holies.Footnote57

In legend, the Lalibela churches’ materiality is challenged by royal chronicles that relate an elaborate story of how angels were active partners in their inspiration, design and construction.Footnote58 This narrative side-lines human agency and the work of designers, craftsmen and labourers. Instead, the churches become an expression of the devolution of spiritual and temporal power from heaven to the kings who were representatives of God on earth. The buildings of Lalibela construct an absolutist state power through a complex juxtaposition of religious, cosmological and biblical allusions, supporting the idea of the unfolding teleology of the God-shaped state. They are a (non)-physical representation of the spiritual world.

Gondar: a more ‘waxy’ affair

The castles at Gondar appear to represent a secular shift. They offer an overt expression of political power: monumental, obviously human-made and centred on temporal concerns. They were built after a period where the power of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church had been significantly undermined by the declaration of Roman Catholicism as state religion. Their construction drew on the skills of outsiders: Portuguese missionaries, builders from the then Portuguese colony of India near Goa, Armenian emissaries and Jewish craftsmen. New technologies of construction were adopted, like burring lime, the structural use of masonry arches and mortar,Footnote59 used to make bridges, enclosures, churches and spaces for religious practice that linked references to older Ethiopian styles with modern imports (). Architectural innovation was accompanied by new forms of artistic expression, a notable example being the wall and ceiling paintings of Debre-Birhan Selassie Church in Gondar. Today, the paintings of winged angel heads that look down on worshippers at Debre Birhan Selassie endow Gondar with its distinctly Ethiopian artistic and architectural identity; and are ubiquitous in popular culture.Footnote60

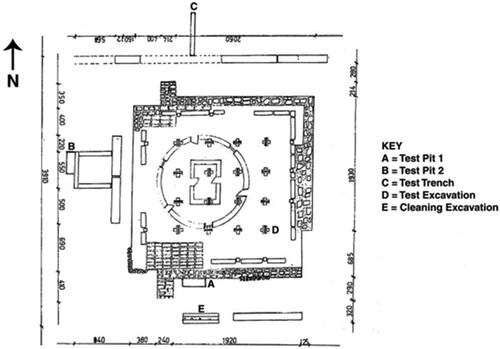

One distinct innovation at Gondar was the introduction of the masonry arch over doors and windows as a structural system. When combined with mortar this enabled the builders to create different types of arch and led to a much simpler construction system compared to the monkey-head detailing. Innovations like these show how practicality and human ingenuity shaped the buildings. In another secular borrowing, many new religious buildings were circular: indeed, the extension of circular plans of the tukuls or round traditional houses to churches seems to have gained popularity, leading to concentric and centralised functional arrangements stemming more from worldly rather than Godly concerns ().

Figure 6. A circular church plan drawing by Ashenafi Girma Zena, reproduced with permission of the author.Footnote112

Yet while the architectural forms of the Godardian castles reveal aesthetic links with European and Indian castles, the details of their form, decorative features and motifs clearly echo recognisable Ethiopian idioms. For example, the sequence and arrangements of the long beam-woods and the small towers at each comer of the palaces echo those found on Askumite buildings (). There is visual consistency in structures from the early period like the palace of Guzara (1570), the Church of Mary Tsion at Aksum (1611–1620) and the imperial compound (1640–1750).

Figure 7. Comparisons between a church window at Lalibela, showing door detail and monkey heads and Emperor Fasilidas’ Castle, Gondar. Photographs by Julia Gallagher.

This hybridity of the castles’ design and ornamentation reflects Ethiopia’s ability to absorb and adapt innovations, what Levine calls its tradition of ‘creative incorporation’,Footnote61 a process of localisation through which external ideas in arts, literature and architecture are adopted and integrated into national culture. But at Gondar, the story of incorporation ends rather differently to Lalibela’s consolidation as the ‘golden’ basis for the state.

Gondar was the first settled capital of Ethiopia in 900 years. Centred around a mobile imperial court, the medieval state had been despotic and focused on warfare. It lacked what Mann terms ‘infrastructural power’Footnote62 such as roads and bureaucracy to establish centralised control over taxation and security. The state had to be continually on the move in order to quell whatever and wherever centrifugal forces became a threat.Footnote63 Perched on an elevated platform, Gondar’s castles correspond to the ‘wandering capitals’ of the medieval royal camps.Footnote64 Gondar’s oval-shaped royal enclosure, composed of emperors’ castles (staffed by personal servants and advisors along with priests, scribes, and political functionaries) formed the spatial nucleus of the city. The numerous commanders and nobility, according to rank and prestige, were settled around the castle, looking inwards in concentric circles, with artisans and traders on the periphery, and peasants beyond the confines of the city.Footnote65 With settlement in Gondar, wrapped in the seclusion of their castles, the monarchs kept themselves busy with court intrigues rather than the business of governing. Unable to ensure loyalty across their territory, they were barely able to assert state power beyond the city and immediate vicinities. The ‘coup d’etat and the killing or imprisoning of monarchs became the rule’.Footnote66 The castles were the sites of power struggle that saw the deposition of more than 25 emperors, and the onset of what scholars have called the period of Zemene Mesafint or the ‘era of the princes’.Footnote67

While once such political arrangements were transient, at Gondar they were made into solid material form. Today they are empty and in ruins. These ruined castles represent a profound departure from a long tradition of state power. Their ostentatious materiality looks like an attempt to turn spiritual power into an earthly form. The spectacular castles, on the surface all potency and might, appear now to describe the transience of vain, secular concerns.

Gondar’s is thus an ambivalent legacy. An example of the creative incorporation of new ideas from abroad, its ruins also attest to the transience of what became a power separated from both religious foundations and from the wider population. It appears, like wax, to have melted away. The palaces express the remnants of extruded, material power, the antithesis of Lalibela’s unobtrusive – and living – buried churches. Like all ruins, they illustrate the cyclical nature of power, and a lingering idea that rejections of tradition set the scene for state failure; all surface ‘wax’, they lack connection to the all-important ‘gold’.

This is the architectural basis of the great tradition. Ethiopia’s iconic architectural treasures tell a story of continuity and disruption that speaks to sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) dichotomies of spirituality vs materiality and teleology vs transience; and the ambiguities created by innovation. The references to an architectural lineage play on the idea of teleological time and the idea of a permanent, solid core that underwrites state authority with spirituality. However, the state also borrows architectural references and techniques from the outside world, sometimes in ways that contribute to religious authority (as at Lalibela) and sometimes in ways that detract from it (as at Gondar). It appears that ambiguities introduced through innovation follow Mohammed’s logic of absorption or rejection.Footnote68 Lalibela, a permanent, apparently unchanging image of spirituality, implies a clear representation of immutable ‘gold’, while Gondar, shaped by outsiders and presenting ideas of change, offers a story of how ‘wax’ is washed away.

Citizens, buildings and state

This architectural version of the great tradition forms a background to how Ethiopians think about their modern architecture and what it tells them about their state. However, as we now discuss, there are more layers of unresolved ambiguity in people’s stories of the state than we have found so far. These, we suggest, demonstrate both support for and questioning of the ‘great tradition’ narrative. We will argue that internal ambiguity within the great tradition allows for an unsolvable but sustaining critique.Footnote69

This section draws on work with 16 FGDs undertaken with citizens who lived and worked in Addis Ababa in February 2020.Footnote70 Addis citizens have closest proximity to the state, surrounded by its current architectural manifestations. They are the most diverse, cosmopolitan section of the population. Thus, they might be expected to have relatively intense and complex relationship with the state.Footnote71 Discussions focused on identifying Ethiopia’s ‘most important state buildings’, in describing these and discussing the ways in which they represent Ethiopian history, politics and culture. Our interlocutors were drawn from a range of groups, including people working in various sectors, students and members of religious organisations. Half were women, and ages ranged from 16 to 80. Each group comprised between five and ten people. We attempted to include representation from across Ethiopia’s ethnic groups, although this was a struggle, partly because sensitivity on the issue made direct questioning on identity difficult. Some of this sensitivity was reflected in the discussions, as explored below. Discussions were conducted in Amharic and English.

Addis is a relatively modern city (founded during the reign of Menelik II, 1889–1913), with 130 years of political upheaval condensed within its state buildings which include structures from the imperial era, Italian occupation, military rule, the EPRDF and the urban mega-projects of Abiy’s regime. Biruk argues that, despite dramatic shifts in regime type and ideology, Addis’s building projects have continuously illustrated top-down, modernising ambitions.Footnote72 The city’s buildings, therefore, sit within a background story of the architectural telling of the great tradition; some deliberately reference this legacy, and most are read by locals within or against it.

Many of our interlocutors used state buildings in Addis to navigate Ethiopia’s history and to explain its present: the buildings ‘represent the changes that have taken place in Ethiopia’Footnote73 and ‘reflect different facets of our history and also our current condition’.Footnote74 Their thoughts on how buildings illustrate history were complicated and we organise them into three sets of reflections. The first is found in connections between Ethiopian history and what people described as ‘authentic’ culture, contrasted with often suspect modern or foreign influences. Here, we suggest, architecture is used to show how the Ethiopian ‘gold’ – a pure, autochthonous historical record – is being overwritten by a layer of foreign ‘wax’. The second begins to unpick this process and is more troubled, reflecting modern preoccupations with ethnic and cultural diversity. Discussion turns here to an inherent ambiguity in Ethiopia’s culture – a local ‘waxiness’ – that is impossible to represent architecturally and which is imperfectly resolved by importing supposedly neutral foreign methods and aesthetics. Here, the great tradition is under threat from internal division, suggesting an anxiety about the security of its legacy that stems not from imported ideas but from internal instabilities. Finally, our interlocutors turn their thoughts to a more nuanced reading of the state, finding evidence of historical rupture and incoherence stamped on their state buildings. This reading describes the coming and going of a procession of regimes – a cyclical tradition of ambiguity and compromise. Here is where the spiritual strand of the great tradition is most challenged, with people outlining a material Ethiopian past – ‘waxy’ contingency, compromise and ambiguity. These three areas of discussion suggest that the great tradition is a thread by which to navigate complex ideas of identity, but also they also complicate it. The FGDs highlight a layered history that Ethiopians can read in and through their architecture, one that juxtaposes ideas of an underlying continuity overlaid with persistent and intrusive ideas of rupture that cannot be dismissed or neatly incorporated, but live troublingly alongside an essentialist perspective.

Authentic culture vs modern vacuity

We found implicit references to the great tradition most often when interlocutors compared modern architecture projects and ancient buildings, couching them in terms of ‘Ethiopianness’. Modern buildings were often found to be lacking due to the break they represented with the past – the failure to continue the historical traditions found in places such as Aksum, Lalibela and Gondar. This was often connected with ideas of the glory and majesty of the past (and an implicit sense that the modern was altogether less acceptable by comparison).

Addis Ababa’s modern buildings in general were described as ‘rectangular and of similar design … [they] do not reflect history and culture. They focus on technology and functionality’.Footnote75 Modern state buildings were said to ‘reflect alien symbols or culture’,Footnote76 because ‘almost all of the buildings in Addis … are outside of the country’s historical, economic, political, social and cultural background’.Footnote77 The adoption of foreign technologies and aesthetics was ascribed to the lack now of a ‘general grand narrative or value that holds the parts together’.Footnote78 One government employee said: ‘I think that is one of our limitations: we don’t have our architecture … In other countries, you can tell by seeing the buildings which country they belong to … Russian, British architecture.’Footnote79 These flat-surfaced, alien buildings were ‘fragile’,Footnote80 and ‘look as if they are going to collapse soon’.Footnote81

In contrast, older buildings, no matter which period they came from, seemed to display a confident and explicit ideology – represented in ‘artefacts that tell about our history and heroism such as the shield, the spade’Footnote82 – and physical and ideational strength – ‘the old buildings are much superior in terms of both aesthetics and strength’.Footnote83 A student summed up the difference between old and new:

Historical buildings were constructed with high commitment. They have lasting values. They show patriotic feeling of our forefathers and mothers. We today are self-centred, making money out of architectural works.Footnote84

One reason for this decline was a loss of expertise. A student noted that despite modern techniques ‘the architectural productions today are not based on traditional knowledge because architects are not able to repeat what St. Lalibela and the Aksum kings did in the country’.Footnote85 This sense of rupture with the skills of the past, combined with the failure of the present to live up to historic standards, was similarly felt by another to be reflected in the quality of buildings constructed: ‘[h]istorical buildings are irreplaceable … [in] previous periods long-lasting building materials were used. The quality of the materials these days is very low’.Footnote86 The modern buildings appeared wanting due to their discontinuities with the values, techniques and standards of the past, pursuing instead short-term and materialistic objectives. Reflecting on the loss this evoked one student noted: ‘I have visited Unity Park at Menelik II palace recently. I have seen fantastic architectural designs and buildings which we might not repeat again in their structure and form.’Footnote87 Such comments hinted at a degeneration in the ideals and capacities of the Ethiopian state.

This account suggests a familiar dichotomy centred on ideas of endurance vs ephemera with different values assigned to the long- and short-term. However, materiality was not dismissed, but evaluated, with ancient skills and materials valued highly over modern ones which were ‘materialistic’. Particularly interesting, judgements on good and bad types of materiality drew on buildings’ capacity to reflect and create shared social meanings. One discussant summarised this as follows: ‘the [modern] buildings do not reflect the cultural dimension of our country. For me buildings are more than the artefacts and wisdom of the modern architectural profession. I think they must have the social meanings shared by members of the communities’.Footnote88 The normative view that buildings should be reflective of indigenous cultural practices and symbolisms was summed up particularly clearly by a student:

[A]rchitectural designs, for example Ethiopia’s famous rock-hewn churches, which are based on one’s cultural knowledge, communicate the social, political, economic and religious aspects of a given society. We Ethiopians have historical buildings which somehow show the social and political lives of people in the past. They tell us about Ethiopia’s magnificent history in architectural development. Modern buildings … however, say nothing about the people’s culture, value[s], norm[s] and beliefs.Footnote89

In this first set of stories about buildings, new imported aesthetics and techniques appeared to constitute the ‘wax’ – materialistic, vacuous, inauthentic – while older aesthetics represented the ‘gold’ – durable, meaningful and properly Ethiopian. However, this version of the great tradition is not about a detached spiritual realm but clearly rooted in ideas about popularly-owned, human-created ‘culture, values, norms and beliefs’. The state represented by such buildings was strong because it had cultural resonance; its ‘gold’ appeared to be a more human affair.

Troubled cultures ‘rescued’ by foreign neutrality

However, this reading of an essentialised culture became more troubled as discussions continued. Questions – and tensions – emerged over precisely whose culture was being discussed. When some talked about culture in terms of ‘the people’s culture’, others joined with references to ‘members of the communities’ or to historical buildings with ‘cultural interpretations which symbolise the lives of the societies’.Footnote92 It became clear that a single culture, even if it could ever have been said to reflect Ethiopia’s history, was inadequate for its present. One government employee noted that the country was one of ‘diversified cultural practices’Footnote93 and another called it ‘ethnolinguistic and multiethnic’.Footnote94 The result, some acknowledged, was ‘growing ethnic polarisation in Ethiopia’,Footnote95 creating uncertainty that arose from local rather than foreign ambiguity. As a result, people argued it was impossible currently for new state buildings to represent Ethiopia’s diversity: it could not be expressed by a coherent narrative. For many interlocutors this was a cause of concern.

What could be done? Many argued that the state should reassert itself as a firm and single source of authority. Some argued that a more open state – tolerant of a wider range of ideas – looks uncertain and weak. Here, the relationship between a diverse society and a monolithic state was seen as in some ways necessary; where the state begins to absorb diversity, it loses its ability to stand above and control it. Ethiopia’s current inter-ethnic tensions were a worrying result of this state-weakness. One interviewee said: ‘The reason why ethnic tension has increased in recent years is because people are enjoying freedom now. But unfortunately, they are ignoring their duties.’Footnote96

On one hand, foreign influences were further diluting state certainty. The state’s weakness was illustrated in its statements of intent, its purpose, which appeared far more reactive and contingent, dependent on ‘foreign culture … [or] capitalism’,Footnote97 the epitome of transient materialism. The effects were seen in architectural neutrality that, by aiming for inclusiveness, achieved only vacuity.Footnote98

But on the other hand, there appeared to be little option. When considering the possibility of a new Ethiopian architecture to define the era, a government worker said:

I am afraid that is impossible. There are so many groups in Ethiopia. How are we going to show all these cultures and their symbols in state buildings? That is just not practical. Let us simply focus on functionality; we should not bother about these kinds of questions.Footnote99

A history of disjuncture and compromise

Finally, almost as though this local challenge to the great tradition could help people reevaluate their history, discussions turned back to the past in a closer examination of Addis Ababa’s older state buildings, and discussions began to explore Ethiopia’s history of disruption. Now a tradition of difference and change emerged; navigation through history became a way in which old buildings were read as the story of political transition. An Addis Ababa University student explained that buildings ‘contain the legacies of the different governments that have ruled Ethiopia. If you take this university for instance, you find the legacies of at least three governments starting from Emperor Haile Selassie through the military rule and EPRDF’.Footnote100 Buildings often reflect the politics of their era and, as a teacher pointed out, ‘it is better to see them in their own historical context. Each shows the level of civilisation of their time’.Footnote101 But also, many discussions focused on how buildings are reoriented to serve successive regimes, being repurposed, renamed and redecorated to reflect the regimes that occupied them. In this way, each building is marked by a procession of ideas. For example, the newly opened Unity Park is home to ‘different buildings, old but beautiful buildings, built by Menelik II including the dining hall and the palace grounds where the higher officials of Haile Selassie’s government were imprisoned.’Footnote102 The Park explicitly describes Ethiopia’s dramatic recent history as an evolution of imperial dynastic rule, its abrupt replacement at the 1974 revolution by Military Rule, and now its reflection of a more pluralist ideology.

Several discussions centred on the ideological symbols which were sometimes attached to buildings as a mark of each era. The imperial regime, for example, used ‘lions carved on palaces and other state buildings including gates … to convey a message that the Solomonic dynasty was as strong and powerful as a lion’ and ‘gates and churches’ to ‘symbolise relations between the Emperor and church’.Footnote103 This example – given in a discussion amongst university students – was joined by another from the Derg period, when the Addis Ababa Municipality Building was decorated with ‘symbols that reflected the time … [for example] the torch that is associated with socialism’.Footnote104 A similar point was made in another discussion:

Those buildings erected during the monarchies, we find more religious expressions on them. That started to fade during the military rule due to its embracing of the socialist ideology: buildings became more secular. During the EPRDF time most of the buildings focused on reflecting the symbols of the different ethnic groups.Footnote105

Ownership and functions were likewise changed by successive regimes. For example, ‘most buildings were owned by the nobility until the military rule nationalised them after the popular revolution of 1974’Footnote106 and ‘the Central Prison which after Abiy came to power was changed into a museum to show the public the injustices and torture that were committed by the previous government in the prison.’Footnote107 Names were another ideological marker, as ‘schools and hospitals built during past systems were named after heroes and patriots’Footnote108 but ‘during the Military rule, most hospitals and schools were renamed. For instance, the famous high school in Addis Ababa known as Addis Ketema [after an area of the capital] was once known by the name Prince Mekonnen School [after one of Hailie Selassie’s sons]’.Footnote109 And in another example, ‘the hospital Yekatit 12 [was named] to commemorate the victims of Italian retaliation for the killing of their Marshal Graziani … I heard that it was built by the then Yugoslav government’.Footnote110

These descriptions of political change that are read in Addis Ababa’s state buildings are strikingly different from conventional accounts of historical continuity and the dismissal of materiality and human agency. The historical record that is most accessible appears to have been marked and shaped by changing political ideas, materialised in structures, decorations and names.

However, even while finding ambiguity in the past, our interlocutors appeared also to see something solid and reassuring in the way the buildings describe – and to an extent explain – this history of rupture. It was notable within group discussions that people insisted that buildings served a vital role in preserving the historical record, in part because each regime was so determined to stamp its personality on them such that the buildings remain as rare reliable witnesses to a political history that has often appeared in danger of being erased. One university lecturer explained this point of view:

I think destroying our past and denying it will not do us any good as a nation. Yes, there are many groups in Ethiopia that feel the past systems especially those that predate the military rule subjugated them culturally, economically and politically. But that … is part and parcel of the nation-building process. I think what we are doing now, including the buildings we erect, should reflect that diversity. But we should accept our past; our history.Footnote111

Historical comparison was valued for helping our interlocutors’ understand their state. Using buildings as a way into state-meaning revealed both an attachment to the great tradition and an ability to question it, as something that partly sustains the modern state, and perhaps as something that never explained it effectively. It was this ambiguity – the attachment to and suspicion of it – that helped explain the great tradition’s endurance as a marker of Ethiopian history. It works, like sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ), to differentiate the monolithic state from ephemeral political change, but also to explain the relationship between the two.

Conclusion: stories of stories of stories

Through the buildings themselves, and through Ethiopians’ stories about them, we have seen how the great tradition endures as a way to explain Ethiopia’s political exceptionalism and longevity and its roots into local meaning and culture. It is used by Ethiopians when they try to make sense of their current anxieties over the challenges to state authority and certainty that are being stirred up by diversity and conflict. At times there was a feeling of the end of Ethiopian history here – that buildings which represent the country’s great past have become impossible to replicate or recover in the modern era. This provides a description of people’s anxiety about the continuing progress of their great state-tradition.

At the same time these modern anxieties are played out within reflections on a history that is not viewed as certain and clear cut. The great tradition has always been underwritten – as opposed to merely overwritten – by ‘waxy’ adaptation and compromise. This was seen in the buildings themselves, their designs, materials and construction techniques, and in how they are used and viewed today. It is also acknowledged in citizens’ reflections on the way in which their dramatic history has been written into the buildings – and by extension, the state – piecing together and making sense of imported ideas, local hybridity and ideological change. The sem-ena-werq (ሰም እና ወርቅ) that helped us unpick the dichotomies of the great tradition allows us to see the creative importance of ambiguity within the great tradition and the Ethiopian state.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dawit Yekoyesew and Addisu Meseret Tadesse for their support with fieldwork; and Antara Datta, the reviewers and editors at JEAS for many helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Such readings are carried explicitly or implicitly in most historical accounts of Ethiopia. For example: Markakis, Ethiopia; Bahru, History of Modern Ethiopia; Marcus, History of Ethiopia; Henze, Layers of Time.

2 Budge, The Queen of Sheba; Marzagora, “History in Twentieth-Century Ethiopia”.

3 Vaughn, Ethnicity and Power; Abbink, “Ethnic-based Federalism”; Clapham, “Rewriting Ethiopian History”; Toggia, “History Writing”. There are over 80 ethnic groups in Ethiopia; three-quarters of Ethiopians belong to the Oromo, Amhara, Somali or Tigrayan groups. The Amhara, although not the largest group, has been historically dominant.

4 Ibid., 426.

5 Sorenson, Imagining Ethiopia, 38–40.

6 Marzagora, “History in Twentieth-Century Ethiopia”.

7 Triulzi, “Battling with the Past”.

8 Clapham, “Rewriting Ethiopian History”: 37.

9 As David Milne argues: “Because of this intimate connection between architecture and the state's order architects have themselves argued that in the buildings of past ages we have the most reliable guides to the ‘life’ of each civilisation.” Milne, “Architecture”, 131.

10 Phillipson, Ancient Ethiopia; Henze, Layers of Time.

11 Phillipson, Ancient Ethiopia; Finneran, “Built by Angels?”.

12 Marcus, History of Ethiopia; McClellan, “Articulating Economic Modernization”.

13 Pankhust, “Menelik”; Ashenafi, “Archaeology, Politics and Nationalism”.

14 Levin, “Haile Selassie’s Imperial Modernity”; Markakis and Beyene, “Representative Institutions in Ethiopia”.

15 Donham, Marxist Modern.

16 Biruk, “Urban Layers”.

17 Fuller, “Building Power”; Rifkind, “Architecture and Urbanism”.

18 This approach takes up Yusuf’s approach to history and storymaking, Yusuf, “Politics and Historying”. It contributes to an emerging literature on politics and architecture in Africa: Tomkinson et al., “Architecture and Politics”; Daniel, “Pan-Africanism”; Gallagher et al., “State Aesthetics”; Batsani-Ncube, “Whose Building?”.

19 Shenk, “Church and State”.

20 Mohammed, Understanding; Mohammed, “Whose Meaning?”.

21 Triulzi, “Battling with the Past”.

22 Levine, Wax and Gold.

23 Daniel, “Pan-Africanism”.

24 Hobsbawm and Ranger, Invention of Tradition.

25 Dinkinesh is the name given to a 3.2 million-year-old female Australopithecus afarensis hominid found in the Afar region in 1974. Bahru, History of Modern Ethiopia; Marcus, History of Ethiopia.

26 Cartwright, “Kingdom of Axum”.

27 Atnatewos et al., “State-Building in Ethiopia”.

28 Clapham, “Rewriting Ethiopian History”; Toggia, “History Writing”. Bahru writes that history has emerged within a ‘restrictive culture … delineated by Solomonic legitimacy and Shawan hegemony, cultural as well as political … Ethiopian history could only be the story of the Semitic north, with the peoples of the south as objects rather than subjects of history’. Bahru, Society and State, 37.

29 Daniel and Tekletsadik, “Ethiopian Qine”.

30 Bloom, “The Ethiopic Writing System”, 30.

31 Mohammed, Understanding, 3.

32 Levine, Wax and Gold, 5. The analogy does not draw on the ‘lost-wax’ method used by metal workers where wax is used to create a mould for making golden objects.

33 Mohammed, Understanding: 1.

34 Ibid., 3.

35 Messay, Survival and Modernization; Mohammed, Understanding.

36 Messay, Survival and Modernization, 183.

37 Mohammed, Understanding, 37.

38 Messay, Survival and Modernization, 118–82.

39 Ibid., 183.

40 Levine, Wax and Gold., 8–9.

41 Ibid., 9.

42 Messay, Survival and Modernization, 181.

43 Mohammed, Understanding, 180.

44 Ibid.

45 Marzagora, “History”, 428.

46 Doresse, Ancient Cities and Temples, 30–31.

47 Marcus History of Ethiopia, 18.

48 Lyons, “Power in Rural Hinterlands”.

49 Henze, Layers of Time, 35.

50 Pankhurst, “Foundation of Addis Ababa”, 46.

51 Salvo, Churches of Ethiopia, 59.

52 Salvo, Churches of Ethiopia.

53 Pankhurst, “Foundation of Addis Ababa”, 50.

54 Lindahl, Architectural History of Ethiopia, 54.

55 Salvo, Churches of Ethiopia, 73.

56 Henze, Layers of Time: 41.

57 Heldman, “Architectural Symbolism”.

58 Finneran, “Built by Angels?”; Bidder, “Lalibela”.

59 Lindahl, Architectural History of Ethiopia, 68–80.

60 One example is the use of the images on the tops of Ethiopia’s Habesha beer.

61 Levine, The Greater Ethiopia.

62 Mann, “Autonomous power”.

63 Horvath, “Wandering Capitals”.

64 Ibid.

65 Marcus, History of Ethiopia; McClellan, “Articulating Economic Modernization”.

66 Trimingham, “Islam in Ethiopia”, 104.

67 Bahru, History of Modern Ethiopia.

68 Mohammed, Understanding.

69 This follows Bartelson’s argument about the state itself: Bartelson, The Critique.

70 The research was done before ethnic tension gave way to violent conflict in Ethiopia.

71 Although Daniel writes about how the Ethiopian state is perceived differently – but as intensely – from peripheral rural parts of the country: Daniel, The Everyday State.

72 Biruk, “Urban Layers”, 4.

73 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

74 FGD senior high school students, 27 February 2020.

75 FGD schoolteachers, 19 February 2020.

76 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

77 FGD students, 4 February 2020.

78 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

79 FGD government employees, 21 February 2020.

80 FGD construction workers, 25 February 2020.

81 FGD elders, 16 February 2020.

82 FGD people out of work, 17 February 2020.

83 FGD construction workers, 25 February 2020.

84 FGD students, 4 February 2020.

85 Ibid.

86 FGD religious followers, 10 February 2020.

87 FGD students, 4 February 2020.

88 FGD government employees, 12 February 2020.

89 FGD students, 4 February 2020.

90 Ibid.

91 Ibid.

92 FGD government employees, 12 February 2020.

93 Ibid.

94 FGD youth association, 16 February 2020.

95 FGD religious followers, 10 February 2020.

96 FGD people out of work, 17 February 2020.

97 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

98 Not all new buildings are dreary and shoddy. For example, the new Bole Airport was admired (Tomkinson and Dawit, “Africa’s International Relations”). More broadly many people pointed out the difference between public and private buildings, the latter were thought to be superior in quality (FGD construction workers, 25 February 2020).

99 FGD government employees, 21 February 2020.

100 FGD university students, 24 February 2020. The campus is built on the site of Haile Selassie’s original palace and includes buildings gifted to successive regimes by their respective Cold War sponsors (the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library by the US to Haile Selassie; and its neighbouring Social Sciences Building by the GDR to the Derg).

101 FGD schoolteachers, 19 February 2020.

102 FGD government employees, 21 February 2020.

103 FGD university students, 24 February 2020.

104 Ibid.

105 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

106 FGD elders, 16 February 2020.

107 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

108 FGD university students, 24 February 2020.

109 FGD elders, 16 February 2020.

110 FGD government employees, 21 February 2020.

111 FGD university professors, 20 February 2020.

112 Ashenafi, “Archaeology, Politics and Nationalism”.

Bibliography

- Abbink, Jon. “Ethnic-Based Federalism and Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Reassessing the Experiment After 20 Years.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5, no. 4 (2011): 596–618.

- Assefa, Daniel, and Tekletsadik Belachew. “Ethiopian Qene (Traditional and Living Oral Poetry) as a Medium for Biblical Hermeneutics.” International Bulletin of Mission Research (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2396939320972690.

- Bartelson, Jens. The Critique of the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Bidder, I. Lalibela. The Monolithic Churches of Ethiopia. Cologne: DuMont, 1959.

- Bloom, Thomas. “The Ethiopic Writing System: A Profile.” Journal of Simplified Spelling Society 19, no. 2 (1995): 30–36.

- Budge, Ernest Alfred Wallis, ed. The Queen of Sheba and Her Only Son Menyelek (I): Being the “Book of the Glory of Kings”(Kebra Nagast). Abingdon: Routledge, 2001.

- Cartwright, M. “Kingdom of Axum.” Ancient History Encyclopedia (2019). Accessed October 15, 2020. https://www.ancient.eu/Kingdom of Axum.

- Clapham, Christopher. “Rewriting Ethiopian History.” Annales d’Ethiopie XVI, no. II (2002): 37–54.

- Donham, Donald. Marxist Modern: An Ethnographic History of the Ethiopian Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

- Doresse, J. Ethiopia Ancient Cities and Temples. London: Elek Books Limited, 1959.

- Finneran, Niall. “Built by Angels? Towards a Buildings Archaeology Context for the Rockhewn Medieval Churches of Ethiopia.” World Archaeology 41, no. 3 (2009): 415–429.

- Fuller, Mia. “Building Power: Italy’s Colonial Architecture and Urbanism, 1923–1940.” Cultural Anthropology 3, no. 4 (1988): 455–487.

- Gallagher, Julia, Dennis Larbi Mpere, and Yah Ariane N’djoré. “State Aesthetics and State Meanings: Political Architecture in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire”. African Affairs 120, no. 480 (2021): 333–364.

- Girma, Mohammed. “Whose Meaning? The Wax and Gold Tradition as a Philosophical Foundation for an Ethiopian Hermeneutic.” SOPHIA 50 (2011): 175–187.

- Girma, Mohammed. Understanding Religion and Social Change in Ethiopia: Toward a Hermeneutic of Covenant. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Hein, E., and B. Kliedt. Ethiopia-Christian Africa (Arts, Churches and Culture). Ratingen: Melina-Verlag, 1999.

- Henze, Paul B. Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia. London: Hurst, 2000.

- Hildman, M. E. “Architectural Symbolism, Sacred Geography and the Ethiopian Church.” Journal of Religion in Africa 22 (1992): 222–241.

- Hobwbawm, E., and T. Ranger. The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Horvath, R. “The Wandering Capitals of Ethiopia.” Journal of African History 10 (1969): 205–219.

- Kebede, Messay. Survival and Modernization: Ethiopia”s Enigmatic Present: A Philosophical Discourse. Asmara: The Red Sea Press, 1999.

- Kebede, Messay. “The Ethiopian Conception of Time and Modernity.” Philosophy Faculty Publications 111 (2013). Accessed February 6, 2022. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/phl_fac_pub/111.

- Levin, Ayala. “Haile Selassie’s Imperial Modernity: Expatriate Architects and the Shaping of Addis Ababa”. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 447–468.

- Levine, Donald. Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

- Levine, Donald. The Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of Multi-Ethnic Society. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1974.

- Lindahl, B. Architectural History of Ethiopia in Pictures. Addis Ababa: The EthioSwedish Institute of Building Technology, 1970.

- Lyons, Diane E. “Building Power in Rural Hinterlands: An Ethnoarchaeological Study of Vernacular Architecture in Tigray, Ethiopia.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 14, no. 2 (2007): 179–207.

- Mann, Michael. “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins Mechanisms and Results.” Archives Europeennes de Sociologie 26, no. 2 (1984): 185–213.

- Marcus, Harold. A History of Ethiopia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Markakis, John. Ethiopia: The Last two Frontiers. Woodbridge: James Currey, 2011.

- Markakis, J., and A. Beyene. “Representative Institutions in Ethiopia.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 5, no. 2 (1967): 193–217.

- Marzagora, Sara. “History in Twentieth-Century Ethiopia: The ‘Great Tradition’ and the Counter-Histories of National Failure.” Journal of African History 58, no. 3 (2017): 425–444.

- McClellan, C. W. “Articulating Economic Modernization and National Integration at the Periphery: Addis Ababa and Sidamo’s Provincial Centers.” African Studies Review 33, no. 1 (1990): 29–54.

- Melake-Selam, Atnatewos, Daniel Mulugeta, Joanne Tomkinson, and Julia Gallagher. “State-building in Ethiopia: Tracing the State Through Architectural Continuity and Disruption.” African State Architecture (2020. Accessed September 7, 2020. https://www.africanstatearchitecture.co.uk/post/state-building-in-ethiopia-tracing-the-state-through-architectural-continuity-and-disrution.

- Mulugeta, Daniel. The Everyday State in Africa: Governance Practices and State Ideas in Ethiopia. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

- Mulugeta, Daniel. “Pan-Africanism and the Affective Charges of the African Union Building in Addis Ababa.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 33, no. 4 (2021): 521–537.

- Milne, David. “Architecture, Politics and the Public Realm.” Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory 5, no. 1-2 (1981): 131–146.

- Pankhurst, Richard. “Menelik and the Foundation of Addis Ababa.” The Journal of African History 2, no. 1 (1961): 103–117.

- Pankhurst, Richard. Historic Images of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Shama Books, 2005.

- Phillipson, David. “From Yeha to Lalibela: An Essay in Cultural Continuity.” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 40, no. 1-2 (2007): 1–19.

- Phillipson, David. Aksum: Its Antecedents and Successors. London: Museum Press, 1998.

- Rifkind, David. ‘Architecture and Urbanism for Italy’s Fascist Empire”.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 70, no. 4 (2011): 492–511.

- Salvo, M. D. Churches of Ethiopia: The Monastery of Narga Sellase. Milan: Skira Editore S.p.A, 1999.

- Schulz, C. N. Existence, Space and Architecture. New York: Praeger, 1971.

- Shenk, Calvin E. “Church and State in Ethiopia: From Monarchy to Marxism.” Mission Studies 11, no. 1 (1994): 203–226.

- Sorenson, John. Imagining Ethiopia: Struggles for History and Identity in the Horn of Africa. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1993.

- Terrefe, Biruk. “Urban Layers of Political Rupture: The ‘new’ Politics of Addis Ababa”s Megaprojects”. Journal of Eastern African Studies (2020). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2020.l774705.

- Toggia, Pietro. “History Writing as a State Ideological Project in Ethiopia.” African Identities 6, no. 4 (2008): 319–343.

- Tomkinson, Joanne, Daniel Mulugeta and Julia Gallagher, eds. Architecture and Politics in Africa: Making, Living and Imagining Identities Through Buildings. Oxford: James Currey, 2022.

- Tomkinson, Joanne, and Dawit Yekoyesew. “Global Ambitions and National Identity in Ethiopia’s Airport Expansion.” In Architecture and Politics in Africa: Making, Living and Imagining Identities Through Buildings, edited by Joanne Tomkinson, Daniel Mulugeta and Julia Gallagher. Oxford: James Currey, 2022.

- Trimingham, S. Islam in Ethiopia. London: Oxford University Press, 1952.

- Triulzi, Alessandro, et al. “Battling with the Past: New Frameworks for Ethiopia Historiography.” In Remapping Ethiopia: Socialism and After, edited by Wendy James, 276–288. Oxford: James Currey, 2002.

- Vaughn, Sarah. “Ethnicity and Power in Ethiopia.” PhD thesis. Accessed February 15, 2022. http://hdl.handle.net/1842/605.

- Yusuf, S. “The Politics of Historying: A Postmodern Commentary on Bahru Zewde’s History of Modern Ethiopia.” African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 3, no. 9 (2009): 378–383.

- Zena, Ashenafi Girma. “Archaeology, Politics and Nationalism in Nineteenth- and Early Twentiety-Century Ethiopia: The use of Archaeology to Consolidate Monarchical Power.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 53, no. 3 (2018): 398–416.

- Zewde, Bahru. A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855-1991. Oxford: James Currey, 1991.

- Zewde, Bahru. Society and State in Ethiopian History: Selected Essays. Los Angeles: Tsehai, 2012.