?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

There are few questions of greater significance in African international relations than China's actions in and engagement with other states. Chinese infrastructure, businesses, and people have blanketed the continent and revolutionized lifestyles, transportation, and political economies. The advantages and detractions of such developments, in turn, have shaped local attitudes. African attitudes towards China, nevertheless, remain largely the subject of conjecture. This article explores the contemporary attitudes of Kenyan university students to China through surveys and contributes empirical data to the literature. Combined with a comparative textual analysis of the main Kenyan newspaper, the article sheds light on largely unknown—but generally assumed—attitudes of Kenyans towards China. The findings question a stereotype of China in Kenya and, by extension, the actions and reactions of other Africans and African states towards it. They also uncover nuanced attitudes that confound the mostly negative Western narrative about China in Africa. Accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as debt, perceived racism and unfair labour practices, Kenyan university students' attitudes and discourse in the elite media have become less positive. There is, in addition, the broad perception that it is Kenya's leadership that benefits from the relationship and not so much its ordinary citizens.

There can be few questions of greater import in contemporary international relations than the actions of the People's Republic of China's (hereafter ‘China’) and its engagement with other states. China's meteoric rise and rollout of economic, political, and social capital have the potential to upend existing global orders (Pax Americana, for example) and even refashion the state system.Footnote1 Much of China's growing influence across the globe has less to do with its hard power resources and capabilities and more to do with the political economy of its roadbuilding, ports construction, and land, air, and sea connectivity across the Indo-Pacific.Footnote2 China's money, expertise, citizens, and culture are increasingly evident across the six populated continents, and attitudes towards China and the Chinese have developed and grown through such types of exposure.

Multiple studies have attempted to catalogue and analyse perceptions of China – from Kazakhstan to Indonesia.Footnote3 And while survey data has begun to form a snapshot of local or regional attitudes towards the country as an economic and security partner, the cataloguing of the opinions and perceptions of Sub-Saharan Africans remains a small, but growing body of literature.Footnote4 Analyses of the political economy of China's engagement with African states also represent a burgeoning and important field of study and can offer prescient insights into the shaping of African perceptions of China.Footnote5 The growing politicisation of China's political-economic engagement with African states, however, coupled with the lack of empirical data mean that the perceptions and attitudes of Kenyans, Angolans or Senegalese are often bandied about, but rarely substantiated.Footnote6 Accordingly, although they are engaged with China via its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and information campaigns, there is little that is known or understood about the attitudes of peoples geographically distant from China. (China's One Belt One Road – commonly known as the Belt and Road Initiative – is composed of a variety of foreign and economic policies. It aims to strengthen Beijing's economic leadership through a vast programme of infrastructure building throughout China's neighbouring regions.Footnote7)

This article attempts to address this paucity by collecting data from Kenya, and while our choice of this country is by no means random, as explicated below, we assess that collecting Kenyan data is nonetheless important for several reasons. First, by possessing Africa's sixth largest economy as well as East Africa's most vibrant economy and democracy, what Kenya does and how it acts vis-à-vis China may have a major bearing on the political economy of Beijing's continued engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa.Footnote8 Second, not knowing or understanding the attitudes of a sample of their population means that Kenyan political elites are making decisions without reference to or an understanding of their domestic constituencies. Third, Kenya's strategic posture towards China may have considerable influence on how the US, Japan, India, and a variety of middle powers, such as Turkey, operationalise their policies and attempt to maintain or gain influence and power in East Africa and across the continent.Footnote9 Ignorance about what Kenyans and others think may also result in major miscalculations by states that feel threatened by a perceived loss of power, at least to some degree, to a would-be hegemon like China. Thucydides noted that the policies of great powers reflect their fears for their security, and the preservation and enhancement of their interests. Of equal concern, he noted, is their honour, i.e. their status and prestige. As importantly, external states such as the US or the UK may attempt to ‘minimise’ the role of Kenyan political and business elites in encouraging Chinese involvement to further their own interests. In doing so, China's actions in Kenya become a zero-sum game in which Kenya is simply the playing field. There are already indications that this is happening with Western states in particular, as they fail to fully grasp the role played by China on the continent.Footnote10 Importantly, they appear to ignore the robust sovereignty over the interests-driven decision-making of African state leaders and how this drives their engagement with China. Lastly, a stronger political and security relationship between Kenya and China in particular, has implications for Kenyan domestic politics where a history of anti-colonialism and the importance of sovereignty may lead some to oppose such moves, particularly given a reported worry about debt to China.Footnote11

Given the importance of the topic, the article's goal is to capture a snapshot of Kenyans’ attitudes towards China in 2020. To do so, we explore the contemporary attitudes of a small population subset: Kenyan university students of politics and international relations. We then combine the survey results with comparative textual analyses collected from Kenya's elite media. The article proceeds as follows. First, the survey data and the literature of African attitudes, writ large, are explored, paying special attention to work done by scholars in Kenya. The second section explains the article's research design and methodology. The third section maps, analyses, and explains Kenyan university students’ attitudes towards China based on the results of our survey, as combined with text mining and sentiment analyses. The final section concludes the article.

Kenyan views of China: what we think we know

As far back as 2006, a former US Ambassador to Ethiopia and Burkina Faso questioned ‘how much [do] we really know about African publics’ perception of China?’Footnote12 Multiple studies have been carried out attempt to answer that question by measuring the attitudes of Africans towards China—and vice versa. Bailard, for example, used Pew Global Attitudes Project data to explore correlations between African attitudes towards China and the extent of the Chinese media presence across six African nations in 2013.Footnote13 She found that concerted and coordinated Chinese efforts undertaken to expand the reach and relevance of Chinese media across the continent moved African public opinion to generally view Beijing favourably.

Using survey data, Sautman and Hairong conducted their own survey work, in 2009, at universities in nine African countries, and found that African attitudes were generally favourable towards China because of a combination of factors. China was perceived to be cheaply and efficiently building much of Africa's infrastructure, for example, and a boom in primary product exports to China was occurring from some African states. Chinese aid was also viewed as apolitical – unlike Western aid.Footnote14 Another study found that China desperately needed Africa as an export market to fuel its own domestic growth. At the same time, Africa needed China for loans, development, and infrastructure. Yet, while this may have been a symbiotic relationship, it was one that seemed to be benefiting China more – both in perception and reality.Footnote15

The sheer growth, volume, and size of China's involvement on the continent has alarmed traditional Western donors and Japan, which have been quick to accuse China of stalling democratic growth in the continent due to its unwillingness to tie its loans to watchwords of the liberal international order such as rule-of-law.Footnote16 In the same vein, this aspect of China's non-interference in the internal politics of African countries has been attractive to African leaders, who have been looking ‘East’ for nearly two decades in order to counter Western aid conditions.Footnote17

However, this narrative of China's development in Africa has been undone, in part, by the perception that China is crowding out jobs in Africa and rendering its local manufacturing capacity uncompetitive. ‘Trade imbalances … , the exportation of substandard goods to Africa from China, China's neglect of issues of governance and human rights, and China's contribution to deindustrialization make the relations between the two regions unsustainable in the long term.’Footnote18 Accordingly, scholars have begun to focus on the economic ramifications of China's relationship with African states, particularly vis-à-vis its effects on local industries.Footnote19 One such study found that the number of Chinese workers in Africa is disproportionately high when compared to the amount of financing that China has provided and when compared to migrants from other states, regions and continents.Footnote20 From these studies, some have concluded that while Chinese ‘development’ may be popular with the political leadership in Africa, in general, it is rather less popular with the general public. However, the survey results showing reportedly negative attitudes among the latter offer an unclear snapshot. For instance, a survey conducted by Ipsos Synovate in 2018 found out that 38% of Kenyans felt their main reason for perceiving China as a threat to Kenya's development was on account of possible job losses. A total of 26% of respondents saw China as the country that constituted the biggest threat to Kenya's economic and political development outside of East Africa.Footnote21

When compared to much of the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, basic data regarding Kenya and Kenyan opinions of China is relatively well-known. This is largely because Kenya, along with Nigeria and South Africa, figures in many of the studies conducted by the Pew Research Center, Ipsos, and others that attempt to measure African attitudes. However, little has been done, to date, beyond limited, mostly one-question surveys aimed at measuring Kenyans’ general attitudes towards China.Footnote22 Alternatively, several studies have been conducted that view aspects or facets of Kenyans’ changing relationship with China. Gallup, for example, conducted surveys in 11 African countries, including Kenya, in 2014, that measured Africans’ approval of American or Chinese leadership. Kamoche and Siebers explored Chinese management practices in Kenya through a critical post-colonial lens; they conducted interviews across sectors ranging from engineering to mining and construction to travel.Footnote23 Similarly, Rounds and Huang interviewed managers at Chinese and American firms in Kenya in order to understand the extent to which labour conditions at Chinese firms in Kenya are a function of firm nationality, as opposed to other characteristics like industry, firm size or length of time operating abroad.Footnote24 They found similar attitudes towards the qualities and limitations of their Kenyan employees – although Chinese expressed their attitudes differently from Americans. In another study, a discourse analysis of articles from The Daily Nation – the same Kenyan elite media source used for this article – was employed to analyse Kenyans’ reception of the Chinese narrative towards Africa, ‘which stresses a win-win cooperation based on the “business-as-usual” approach, with no political interference and no strings attached.’Footnote25 Sanghi and Johnson, nevertheless, found few instances where Chinese firms and businesses had effectively transferred technology and skills to Kenyan workers or firms.Footnote26

The above-referenced studies largely originate from non-Kenyan sources, but surveys conducted by Kenyan scholars and institutions also reveal interesting results about Kenyans and their attitudes to China and the Chinese. One area of development cooperation that has irked several Kenyans is its growing national debt. One Kenyan scholar has argued that China has tightened its grip on Kenya's economy by becoming the country's largest bilateral lender, with its debt stock increasing by 52.8% to Sh478.6 billion in 2017, from Sh313.1 billion in 2016. This implies that Beijing now controls 66% of Kenya's total bilateral debt, which stood at Sh722.6 billion in June 2017.Footnote27 Another study concluded that China's aid and foreign direct investment (FDI) have a significant positive effect on Kenya's economic growth. Its loans, however, have a detrimental effect and thus the two cancel each other out.Footnote28

The economic implications of China's actions have led to concern among Kenyans about the effect of Chinese goods flooding the market, suffocating local manufacturing and causing job losses in the process. A study confirmed that these fears were based on the collapse of a number of local Kenyan firms after their inability to compete with Chinese businesspeople and Chinese goods in Kenya.Footnote29 Adding to the problem, scholars in Nairobi found that ‘African states do not have a common ground that they can use as a bargaining chip to their advantage from this partnership [with China].’Footnote30

The result of national debt owed to Beijing, the crowding out of local firms, producers, and jobs because of Chinese goods and businesses, as well as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have all conspired to influence Kenyans attitudes towards China and Chinese people. The questions this article attempts to answer are, therefore, how and in what way?

Methodology

The methodology employed for this study is both quantitative and qualitative in that we complement quantitative findings using Jaccard similarity indices (JSI) and sentiment analyses from Kenya's leading daily newspaper with survey and interview results. For the purpose of this article, the focus is on the attitudes of students of politics and international relations at Kenyan universities towards China, Chinese projects, and Kenya's current and future economic and security relationships with that country. Whether Kenyan political elites are sensitive to the attitudes of their constituents or whether Kenyan political elites have been promoting their country's relationship with China are beyond the scope of this article. This is because the current attitudes of Kenyans – both in general and as population subsets - towards China remain largely unknown. As such, it seems advisable to identify and analyse them perhaps prior to examining any influence they may have on policy.

Text mining and Jaccard similarity indices

Leveraging a methodology of text-mining of key terms associated with the terms ‘China’ and ‘Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)’ and employing Jaccard similarity indices (JSI), this study compares the content of survey results with elite media commentary, to include news articles and opinion pieces. This comparative methodology, as we explain below, supplements our survey data, thereby offering a comparison between the results of the survey and the prevailing media discourse in Kenya in relation to China and its signature foreign aid programme, the BRI.Footnote31 In analysing elite media, we are not concerned with the extent to which the Kenyan media may shape foreign policy decision-making – in this case towards China. Rather, we define elite media as media such as newspapers and TV channels that shape the political agenda of other mass media within Kenya. We thus seek to use the elite media to provide an additional portal into the contours of policy discourse in order to compare it with the attitudes of the survey's study group. Though the methodology has shortcomings, it is, nonetheless, a means of elucidating what China, Chinese projects and Kenya's burgeoning relationship with that country mean to a sub-set of Kenyans in 2020.

Our choice of Kenya was based on the relative ease of compiling data there, our level of access, our familiarity with the country, and thus our list of contacts, particularly in academia. This was important in that it allowed us to perform survey work among the population subset identified for this study. In addition, the readily available online data of one of the two major Kenyan daily newspapers, as discussed below, made it possible to perform sentiment analyses as well as JSIs, thus allowing comparisons with the collected survey data.

Given these abovementioned dynamics, analysing the content of Kenyan elite media alongside survey results appears a fruitful avenue for gaining a better understanding of a subset of the Kenyan polity, its attitudes towards China as well as the policy landscape related to China and its BRI and Kenya's future posture vis-à-vis China. Our choice of what media content to use on China and the BRI is, admittedly, highly selective. A few newspapers and periodicals occupy a particularly important position in Kenya. Most of the national newspaper market share is controlled by ‘the big two’: The Daily Nation (including the Saturday Nation and Sunday Nation) and The Standard (including the Saturday Standard and Sunday Standard).Footnote32 We selected one of the two newspapers, The Daily Nation, because it offered robust online data and search possibilities in a way that its competitor, The Standard, did not.Footnote33

The text mining results of The Daily Nation offered an added level of comparative analysis to the survey results in that they showed changes to the sentiment or tone in two different years: 2017 and 2019. The rationale for using the year 2017 was straightforward: articles using the combination of terms ‘BRI and China’ were non-existent in reporting in the Daily Nation prior to 2017. In addition, the Mombasa–Nairobi standard gauge railway (SGR) was inaugurated in May 2017 for passengers. Thus, 2017 was selected because it possibly represented a ‘high time’ for the people of Kenya to appreciate China's infrastructure development in the country. By 2019, reports had surfaced of the Chinese-built SGR costing up to three times more than the global average, combined with reports of Kenya's staggering debt to China as well as backroom deals potentially involving the handover of Kenya's main port at Mombasa to China in case of loan repayment default.Footnote34 It was hypothesized, therefore, that text mining of 2019 data may indicate shifts in the tone of news reportage and editorials in the elite media towards China. In addition, 2019 was the last full year of data available when the survey was conducted.

The Jaccard similarity index (JSI), also known as Intersection over Union and the Jaccard similarity coefficient, is a statistic used for gauging the similarity and diversity of sample sets.Footnote35 Jaccard similarity indices measure similarity between finite sample sets, and are defined as the size of the intersection divided by the size of the union of the sample sets:

(If A and B are both empty, we define J(A, B) = 1.)

This index has been widely used in a variety of disciplines including political science in order to examine the latent similarity between observation objects that were represented in the relevant documents. For example, one study investigated the textual similarity between multiple trade agreements by means of the JSI.Footnote36 In this case, scholars assessed that the JSIs could be used as a tool for evaluating the impact of trade agreements; that is, those which resembled each other being considered to have similar effects on trade. Another recent study focused on the JSIs of political manifestos from 27 European countries since 1945.Footnote37 The authors advocated that the output data of JSIs could be utilised to compare how political parties presented themselves through their electoral platforms. Rich utilised JSIs to try and uncover patterns within North Korean official news channels related to potentially common themes (such as the military and economy) to see whether they were more closely associated with either Kim Il-sung, the ‘Great Leader’ or his son and successor, Kim Jong-il, the ‘Dear Leader.’Footnote38

For the sake of our methodology incorporating the JSIs, this study utilized KH Coder as the text mining software.Footnote39 This software was developed based on the following underlying software: Stanford POS Tagger to extract words from English data, R for statistical analysis, and MySQL to organize and retrieve the data. The data sets to be analysed with the word count (China and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)) and percentage are shown in below.

Table 1. Data sets from articles in The Daily Nation, 2017 and 2019, showing number, in words, of articles and sentences as well as percentages.

Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis, broadly speaking, is the interpretation and classification of emotions (positive, negative and neutral) within text data using text analysis techniques. Sentiment analysis, for example, allows businesses to identify customer sentiment towards products, brands, or services in online conversations and feedback. Sentiment analysis is considered a sub-field of neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) and has become an increasingly popular research method across disciplines during the past 20 years.Footnote40 An increasing number of studies in political communication and international relations, for example, focus on the ‘sentiment’ or ‘tone’ of news content, political speeches, or advertisements.

The phenomenal growth in internet usage and penetration, including in many Sub Saharan African countries, has enabled researchers in different fields to conduct research in order to discover people's opinions and sentiments from publicly available data sources.Footnote41 For example, Kaya, Fidan and Toroslu performed a sentiment analysis on various columns in different Turkish news sites.Footnote42 Mihelcea and Strapparava, for their part, attempted to classify newspaper titles according to their emotion.Footnote43 However, these studies focused more on the advantages or limitations of specific text mining tools. Huang and Wang, on the other hand, used sentiment analysis and emotion analysis to explore how China used ‘panda diplomacy’ to enhance the cognitive influence of its national treasure and to soften its national image.Footnote44 Agarwal, Singh, and Toshniwal analysed Twitter tweets about ‘Brexit’ geospatially to shed light on which locations had positive or negative views about Britain's leaving the European Union.Footnote45 This further demonstrates how sentiment analysis of certain texts can reveal a great deal about how people feel about an event or object.

Surveys

A survey was chosen as the method of data collection because this is commonly used to measure the attitudes and behaviours of people.Footnote46 By ‘attitude’ we mean a settled way of thinking or feeling about something. Attitudes are by no means fixed, but survey data will indicate the state of one's attitude about an issue or object at the time the survey was taken.

The use of survey data as a way to measure attitudes and behaviours is common across multiple academic disciplines. In terms of political science and international relations literature, survey data, particularly time-series datasets, have proved useful, often offering empirically sound explanatory power. Johnston's usage of original datasets for the Beijing Area Study (BAS), for example, allowed him to conduct five studies and associated analyses related to a rise (or not) in Chinese nationalism.Footnote47 In doing so, Johnston discredited the popular meme of ‘rising’ Chinese nationalism, finding that Beijing's coercive diplomacy is more likely the result of elite opinions, security dilemma dynamics and so forth.

We developed a nine-question survey and utilized an online questionnaire development and cloud-based software, SurveyMonkey. The design of this paid close attention to content, criterion, and construct validity, considering – as much as possible in a short online series of questions – the full range of the concept of China's and Kenya's relationship and how well our survey relates to (and goes beyond) previous surveys on the topic. It also considered other theoretically relevant factors, such as the possible disconnect between the attitudes of Kenya's political elite towards China as opposed to those of Kenyan university students of politics and international relations. This population subset could include either graduate or postgraduate students majoring or minoring in such disciplines. But it could also include university students taking classes related to these disciplines sometime during the survey period (see below). We recruited from this specific population subset for a few reasons. First, most respondents likely share urban and middle-class socio-economic backgrounds. Second, we can expect other similarities such as their daily use of information technology, the internet, access to information, and their ability to analyse and critically assess such data. This, in turn, means they may adopt informed and critical stances towards different political issues related to Kenya's international relations.

We tested question order and wording effects with Kenyan colleagues who understand survey methods and methodology and/or the complexity of the survey's subject. Based on the results, we changed the wording of some of the questions to ensure all terms were unambiguous, specific, and non-presumptive. Given the survey's topic, the target population was Kenyan university students of international relations and politics. Nevertheless, a form of snowball sampling was used. This involved finding respondents who met the above-listed criteria of interest and then asking them to forward the survey to other Kenyans who are part of the same target population. The survey sample was collected as follows:

The SurveyMonkey survey link was sent via email to Kenyan university teachers who were asked to forward it to their Kenyan university students of international relations and political science. In this way, anonymity was maintained. In addition, we informed the teachers that students studying related social science subjects (sociology and economics, for example) would also be welcome to take the survey. We also suggested that the teachers send the survey to their colleagues in order for them to forward it to their students. The teachers who sent the survey to their students were located at various Kenyan universities. However, most teachers and respondents were located in the capital, Nairobi.

The SurveyMonkey survey link was sent via WhatsApp Messenger to Kenyan colleagues in academia who then forwarded it to their Kenyan university students of international relations and political science and colleagues. Their colleagues were then asked to send it to their Kenyan university students of international relations and political science. The Kenyan university students of international relations and political science were also asked by their teachers to forward the survey to their cohort who may have an interest in such topics.

We instructed those distributing the survey that only current university students of international relations and political science who were Kenyan citizens should take the survey. As such, diaspora Kenyan students who had renounced their Kenyan citizenship were technically barred from taking it. However, Kenyan students, diaspora or not, holding dual citizenship were welcome to take the survey. The survey, taking on average of 1 min and 46 s, was conducted from late February to early July 2020. We admit the randomness of this timeframe, but it allowed us to gather survey responses of more than 150 (total 169).

Limitations include the sample size, which reduces the explanatory power of the survey results and increases the margin of error but does not render the study meaningless. In terms of validity, for example, the anonymity of the survey takers was maintained. The only identifying data collected was internet protocol (IP) address information, which provided a general geographic location for the individual survey taker. Reliability, or the repeatability or consistency of the findings, is less assured. The research methods employed would not consistently yield the same results over time. As such, the survey results may perhaps better be described as a snapshot in time. In addition, using data collected from a small subset who share similar characteristics that may be at odds with the rest of the population means that our findings may be distorted in terms of demonstrating Kenyans’ views of China. Snowball sampling presents another limitation to the study because not just Kenyan students of politics and international relations at Kenyan universities took the survey. Nonetheless, a random review of 30% of the IP addresses collected during the survey showed that 90% were from Nairobi, with one IP address each in Thika, Mombasa and Kampala, Uganda. There were also two outlier IP addresses from the US. Therefore, the authors assess that the ‘snapshot’ is suitably instructive in that it empirically shows the attitudes of certain Kenyans towards China, tracking with other recent, post COVID-19 onset, academic studies.Footnote48

Mapping, analysing and explaining Kenyan attitudes toward China

This section explains the results of text mining, sentiment analysis and JSIs from the content of news articles in Kenya's The Daily Nation newspaper about China and China's BRI. The mechanisms employed to analyse this media content are a combination of text mining and cataloguing that result in a series of JSIs to display the relationship and importance of association between various words and/or concepts and the term ‘China and BRI.’

Sentiment analysis results

The ‘sentimentr’ package developed for R software environment for statistical computing was used for this sentiment analysis.Footnote49 shows Kenyans’ sentiment towards China and China's BRI in 2017 and 2019. A positive (more than zero) number implies that the ‘tone’ or ‘atmosphere’ of the articles is positive, while a negative (less than zero) number suggests that the ‘tone’ or ‘atmosphere’ of the articles is negative. A larger positive number indicates that the ‘tone’ or ‘atmosphere’ of the articles is highly positive as compared with the articles with a smaller positive number or negative number. The decrease in numbers from a high across all sentences of 0.184 in 2017–0.085 in 2019 demonstrates evidence of a fading positive tone or sentiment in the Kenyan media towards China and its BRI. These findings are nuanced, however. Sentiment analysis strikes a less positive tone in sentences with China than with China's BRI. We assess a possible reason is that journalists and/or analysts may see the fulfilment of the country's infrastructure needs – via BRI-linked funding and building from China – as beneficial, whereas China, as a political entity, is viewed as a less altruistic partner for Kenya.

Table 2. Sentiment analysis of sentences containing the words “China” and/or “BRI” from articles in The Daily Nation, 2017 and 2019.

JSI results

An analysis with JSIs was carried out to illustrate in what contexts the term BRI appeared in the newspaper in 2017 and 2019. For example, shows that the Jaccard Index for ‘BRI’ and ‘opportunity’ is 0.135. It implies that the ratio of A/B is 0.135, where:

Number of sentences which include both ‘BRI’ and ‘opportunity’

Number of sentences which include only ‘BRI’ + number of sentences which include only ‘opportunity’ + number of sentences which include both ‘BRI’ and ‘opportunity’

Table 3. Jaccard similarity index results of “BRI” as keyword from articles in The Daily Nation, 2017.

The Jaccard Index becomes zero (0) in case no sentence includes both ‘BRI’ and ‘opportunity.’ The Jaccard Index becomes one (1) in case all sentences include both ‘BRI’ and ‘opportunity.’ The same word – ‘opportunity’ – does not appear in the ‘top 20’ list of words in 2019 (). Such an observation suggests that the BRI may have been more strongly regarded as an opportunity in Kenya in 2017, while such language associated with China and the BRI had been eschewed by 2019. Similarly, the term ‘cooperation’ fell from being the fifth most used term with a JSI score of 0.089 in 2017 to being eighteenth (out of 20), with a JSI of 0.058. In addition, terms such as ‘port’ (a reference to either Mombasa Port or the Chinese-built Lamu Port, which is currently under construction) and ‘loan’ (a reference to the loans from China's Exim Bank for the SGR) figure in the 2019 list of terms, but not in 2017. Nonetheless, the positive tone assigned to ‘infrastructure’ showed a steady increase from 0.055 in 2017–0.108 in 2019, again possibly reflecting the importance attached by the media to furthering Kenya's infrastructure needs – roads, railroads, and ports expansion.

Table 4. Jaccard similarity index results of “BRI” as keyword from articles in The Daily Nation, 2019.

Analysis with JSIs was also carried out to illustrate in what contexts the term ‘China’ appeared in The Daily Nation in 2017 and 2019 (see and ). In 2017 and 2019, the term most associated with China was ‘Kenya’ with JSI scores of 0.192 and 0.132, respectively. Indeed, most of the terms were ‘value-neutral’ and demonstrate reporting about China-Kenya relations, agreements, trade, and development. The term ‘trade,’ for example, had a JSI of 0.049 in 2017 but rose to 0.069 in 2019. However, this may not demonstrate a more positive sentiment towards China and Chinese businesses. Rather, the Kenyan dailies have featured a rather steady drumbeat of exposés since the opening of the BRI detailing Chinese discrimination, racism, and unfair labour practices.Footnote50 In 2019, for example, three terms figured that were non-existent in 2017: ‘loan,’ ‘phase,’ and debt.’ This may demonstrate growing concerns about the debt owed to China, as well as China's unwillingness to fund, and therefore complete, the next phase of the SGR running from Naivasha to the Kenya-Uganda border.Footnote51

Table 5. Jaccard similarity index results of “China” as keyword from articles in The Daily Nation, 2017.

Table 6. Jaccard similarity index results of “China” as keyword from articles in The Daily Nation, 2019.

In sum, text mining and related JSI analysis point to tonal shifts in the media reportage that possibly influenced and/or corresponded to the reading public's own attitudes towards Kenya's complex relationship with China. For instance, in the case of China and the BRI, we may infer from the results that they offer partial confirmation of the different attitudes of Kenyan university students towards China's BRI as development and economic projects, and China as political entity with increasing visibility within Kenya and globally.

Survey results

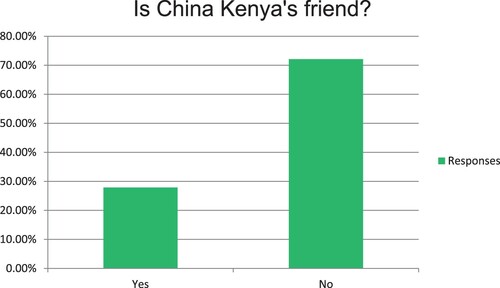

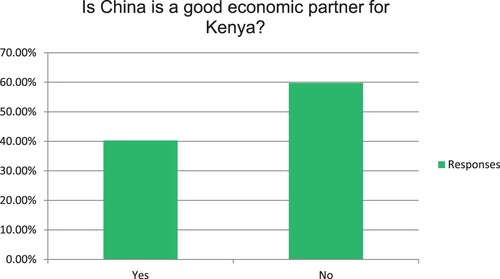

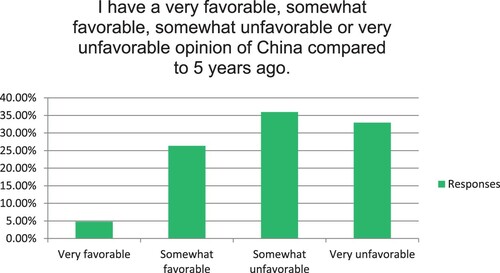

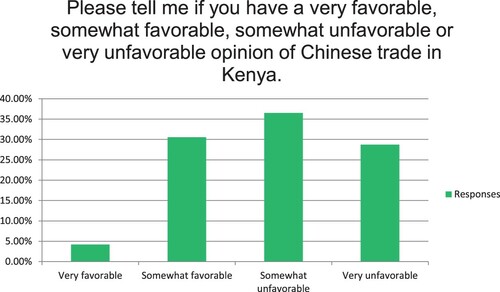

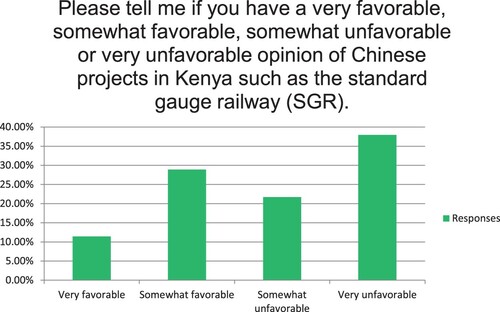

The answers to the survey questions generated several important findings. First, nearly 65% of the Kenyan university students surveyed self-reported that their attitudes were less favourable towards China in 2020 than they were in 2015 (see ). In relation to Chinese trade and Chinese infrastructure and development projects in Kenya (see and ), over 30% reported holding somewhat unfavourable opinions, and almost 40% reported very unfavourable views.

Figure 1. Answer results to survey question 1: I have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of China compared to 5 years ago.

Figure 2. Answer results to survey question 2: Please tell me if you have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of Chinese trade in Kenya.

Figure 3. Answer results to survey question 3: Please tell me if you have a very favourable, somewhat favourable, somewhat unfavourable or very unfavourable opinion of Chinese projects in Kenya such as the standard gauge railway (SGR).

The fact that over 60% of the targeted population surveyed had a very unfavourable or somewhat unfavourable opinion of BRI-linked projects is noteworthy and perhaps goes far in explaining the reported negative views held by Kenyans, in general, towards China in 2020.Footnote52 It was not always this way. When the SGR opened for business in mid-2017, tourist travel between Nairobi and the Kenyan coast skyrocketed. Affordable tickets created a tourism boom as many Kenyans found the trip not only relatively cheap but quick.Footnote53 Yet, the volume of freight traffic on the SGR has never come close to reaching the levels forecast, and even prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, positive feelings about the convenience and cost of train travel seem to have dissipated as a result of the amount of debt owed to China. There were also concerns about the combination of unfair labour practices and overt racism on the part of the Chinese in Kenya (see ). In addition, as of late 2020, Beijing had clearly indicated that it was no longer interested in funding the second, planned leg of the SGR from Nairobi to the Uganda border. This was due, in part, to China's own economic slowdown, according to Chinese officials. However, the fact that the SGR incurred a loss of $200 million during its first three years of operation likely played a role in Beijing's decision.Footnote54

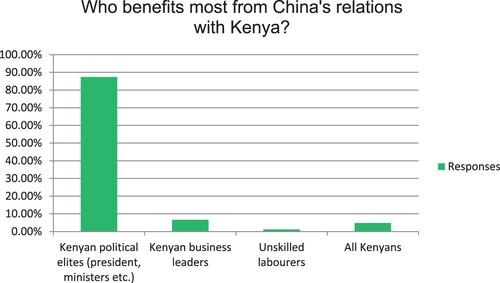

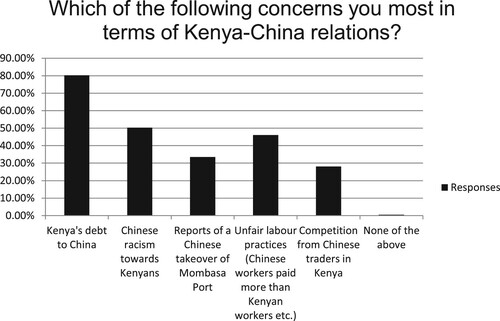

Second, China was not viewed as a friend of Kenya by over 70% of survey respondents (see ), with a majority expressing an unfavourable view of China as an economic partner (see ). Expressions of friendship between states is certainly not a sine qua non for better economic relations. States (and people) are motivated for a variety of reasons to utilize outside parties to pursue interests. Thus, the fact that China is not necessarily viewed as friendly towards Kenya does not mean Kenyans, writ large, do not wish to partake of Chinese-funded BRI development projects, particularly big-ticket infrastructure items like the SGR. Nonetheless, a plurality of survey respondents voiced ‘no’ when asked whether China was a good economic partner for their country. Again, the answers provided to question 8 (see ) highlighting Kenya's growing debt to China, racism, and competition for jobs are worth noting.

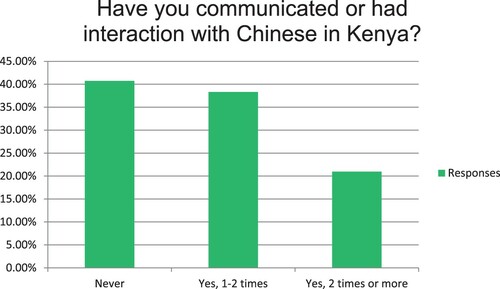

Third, perceptions of Chinese friendship (or lack thereof) may have been motivated by the scarce interaction between Kenyans and Chinese (see ). Even though some respondents reported they had met Chinese on at least one or two occasions, the survey results indicate that contact between the Kenyan students surveyed and Chinese, in general, remained extremely low. Additionally, reports exposing Chinese business practices and establishments that discriminated against, or outright barred, Kenyans may have contributed to this perception.Footnote55

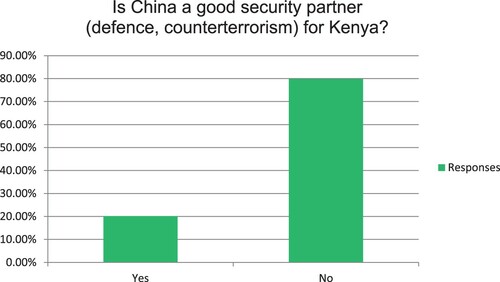

Fourth, nearly 80% of surveyed university students answered ‘no’ to question 6 (see ) about whether China would make a good security (military, counterterrorism) partner for Kenya. This result may indicate a distinct lack of trust in Beijing as a security partner as well as a corresponding desire to engage with other security providers and partners. It certainly may have implications in terms of China's geopolitical ambitions on the continent. China has become an increasingly important arms supplier across the African continent. Its relatively inexpensive drones, fighter jets, and armoured vehicles have been sold from Zimbabwe to Sudan to Nigeria.Footnote56 Kenya, while dabbling in the purchase of Chinese arms, has nonetheless preferred to purchase arms from Western states as well as some former Warsaw Bloc countries. Increasingly negative attitudes towards China, particularly as a potential security threat, coupled with previous bad experiences with Chinese military equipment may see Kenya largely exclude and China in the security realm.Footnote57

Figure 6. Answer results to survey question 8: Which of the following concerns you most in terms of Kenya-China relations?

Figure 7. Answer results to survey question 7: Have you communicated or interacted with Chinese in Kenya?

Figure 8. Answer results to survey question 6: Is China a good security partner (defence, counterterrorism) for Kenya?

Lastly, almost 90% of respondents viewed Chinese projects and China's relationship with Kenya as benefitting only Kenya's political elite and their Chinese partners (). That is, they saw little benefit for the average Kenyan emanating from this partnership. This finding may have major implications in the way Kenya engages with China on future projects. While Kenyan politicians are often said to ignore the wishes of their constituents, populism in Kenya – defined as a political programme or movement that champions, or claims to champion, the common person, usually by favourable contrast with a real or perceived elite or establishment – has played a powerful force in the 2007, 2013, and 2017 elections.Footnote58 With elections scheduled for August 2022 that feature the absence of an incumbent president seeking re-election, some of Kenya's politicians have already chosen to incorporate language that reflects the opinions of at least some of their constituents towards Kenya's massive debt owed to China. Deputy President William Ruto, a candidate for Kenya's next president, criticized the outgoing administration's heavy borrowing from external lenders. ‘We will not resort to lenders like China to extend loans to us,’ Ruto said.Footnote59 Amani National Congress (ANC) party leader and presidential candidate Musalia Mudavadi also called for a renegotiation of Kenya's bilateral and multilateral debts with its external lenders. He singled out China, stating: ‘Let us have a round table with our creditors like China and others and negotiate on how to get out of the multi-trillion debt shackles as we plan to rebuild the already ailing economy.’Footnote60 As such, Kenya's politicians may find that parroting what their voters – or at least a subset of voters - may think about China, particularly given the strong narrative of China's ‘debt trap diplomacy,’ could pay big dividends at the polls. Railing against the Kenyan politicians who have reportedly benefited from Chinese projects in Kenya at the expense of the average Kenyan, for example, may prove an emotive vote mobilizer.

Conclusion

Media reports as well as government statements, particularly in the West, have often characterized China's engagement with Africa in negative terms. In doing so they have tended to downplay some of the reported benefits of Chinese-built infrastructure and development. On the other hand, some scholars as well as the Chinese media have painted a rosier picture of China's interactions with Africa and Africans. The fundamental deficiency with both sides of the China-in-Africa ‘coin’ is that we simply do not possess the body of knowledge that would allow empirically grounded representations of African attitudes. Thus, much of the existing narrative is based on assumption.

This article has attempted to empirically collect, catalogue, and analyse the attitudes towards China of Kenyan university students of politics and international relations in 2020 in order to address this deficiency. The survey results showed that this sub-set of the population self-reported holding largely unfavourable attitudes towards China. This finding was compared with text mining and sentiment analyses from the Kenyan media. The snapshot that emerged indicates that China may no longer be viewed as the silver bullet for Kenya's infrastructure and development needs. Tonal shifts in the reportage and opinion pieces in The Daily Nation from 2017 to 2019 tracked with the less favourable attitudes towards China as an economic, political, and security partner reported in the survey. In addition, the disconnect between the wananchi, or ‘average Kenyans,’ and the Kenyan political and business elite who benefit from Chinese business and development projects was laid bare. While China may remain the partner of choice in Kenya for the foreseeable future, perhaps the most prescient question in Kenya today is not ‘What will China build next?’ but ‘Who else besides China will build it?’

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Layne, “The US-Chinese power shift;” Chin and Thakur, “Will China change?”

2 Hakata and Cannon, “The Indo-Pacific”

3 Syroezhkin, “Social Perceptions of China”; Fitriani, “Indonesian perceptions” O'Trakoun, “China's belt and road.”

4 Manji and Marks, African perspectives; Wang and Elliott, “China in Africa”; Nassanga and Makara, “Perceptions of Chinese.” While not measuring attitudes per se, interesting insights into the views held by Kenya's jua kali casual labourers vis-à-vis China and Chinese businesses by Gadzala, "Survival of the fittest?.”

5 Taylor, China's New Role”; Brautigam, “The Dragon's Gift”; Mohan and Power, “New African choices”; Obi, “Enter the dragon?”; Dobler, “China and Namibia”; Parker and Fourie, “Sino-Angolan agricultural cooperation.”

6 For more on the growing politicization of China's actions in Africa, particularly by the US, Japan and other states associated with the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “Quad”, see Slayton, “Africa: The First U.S. Casualty”; and Cannon, “Influence and Power.”

7 Cai, “Understanding China's Belt.”

8 Signé, The potential of manufacturing; LaGarde, “Kenya at the Economic Frontier”; Akamanzi et al. “Silicon Savannah.”

9 Barton, Political trust; Liu and Tang, "US and China aid”; Cannon, “Grand Strategies.”

10 Cannon, “Influence and Power.”

11 Onjala, “China's development loans”; Alden & Jiang, "Brave new world.”

12 Sautman and Hairong, "African perspectives on China-Africa,” 730

13 Bailard, "China in Africa: An analysis.”

14 Sautman and Hairong "African perspectives on China-Africa.”

15 Mlambo, Kushamba, and Simawu, "China-Africa relations: What lies.”

16 Brown and Raddatz, “Dire consequences.”

17 Eisenman, “China-Africa trade”

18 Ibid., 272.

19 Gadzala, “Survival of the fittest”; Mosley and Watson, “Frontier transformations.”

20 Dollar, China's Engagement with Africa.

21 IPSOS, “SPEC Barometer”

22 Pew Research Center, Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2015; Pew Research Center, Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2018; Pew Research Center, Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2019.

23 Kamoche and Siebers, "Chinese management practices.”

24 Rounds and Huang, "We are not so different.”

25 Řehák, “China-Kenya Relations,” 85.

26 Sanghi and Johnson, Deal or No Deal.

27 Siringi, “Kenya-China Trade Relations.”

28 Wanjiku, “Effect of Kenya's Bilateral.”

29 Farooq et al., “Kenya and the 21st Century.”

30 Omolo, Jairo, and Wanja. Comparative Study of Kenya, 30

31 Mahima Duggal, “China's shifting global strategy on foreign aid,” 9Dashline, 28 January 2021. https://www.9dashline.com/article/chinas-shifting-global-strategy-on-foreign-aid.

32 The print edition of the newspaper continues to go by the name, The Daily Nation. The website, however, is simply Nation. https://nation.africa/kenya/.

33 Free media content along with a robust Twitter feed, among other social media sites, mean Kenyan university students may be more prone to access its contents than those of its competitors.

34 While President Uhuru Kenyatta had dissembled on the topic, more recent reporting indicates that a Chinese takeover of port operations is highly unlikely. See N. Musungu, “Forget it: State House makes U-turn on releasing SGR contract,” Nairobi News, 29 April 2019. https://nairobinews.nation.co.ke/forget-it-state-house-makes-u-turn-on-releasing-sgr-contract/. See also N. Muchira, “Kenya: China Cannot Seize Port of Mombasa if Debt Default Occurs,” The Maritime Executive, 16 March 2021. https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/kenya-china-cannot-seize-port-of-mombasa-if-debt-default-occurs.

35 Niwattanakul et al., "Using of Jaccard coefficient.”

36 Alschner, Seiermann, and Skougarevskiy, The impact of the TPP.

37 Sanger and Warin, "Dataset of Jaccard similarity.”

38 Rich, "Like father like son?;” For more examples see Bursztyn, Nunes and Figueiredo, “How congressmen connect.;” Garcia et al., “Ideological and temporal components.”

39 Higuchi, “A Two-Step Approach (Part 1)”; Higuchi, “A Two-Step Approach (Part II).”

40 Pang and Lee, “Opinion mining and sentiment.”

41 Farhadloo and Rolland, "Fundamentals of sentiment analysis.”

42 Kaya, Fidan and Toroslu, "Sentiment analysis of Turkish.”

43 Mihelcea and Strapparava, “Semeval-2007 task 14.”

44 Huang and Wang, “The New ‘Cat.’”

45 Agarwal, Singh and Toshniwal, “Geospatial sentiment analysis.”

46 Halperin and Heath, Political research, 263.

47 Johnston, “Is Chinese Nationalism Rising?.”.

48 A soon-to-be-published study, which was made available to the authors, on the COVID-19 pandemic found that the pandemic accelerated feelings of anger or ill-will, even hatred against Chinese nationals who have been present in Kenya for years. Institute for Strategic Dialogue. COVID-19 Hate and Extremism Content Action Research: Kenya, forthcoming.

49 Rinker, Package “sentiment.”

50 Paul Wafula, “Exclusive: Behind the SGR walls,” The Standard, 8 July 2018. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001287119/exclusive-behind-the-sgr-walls; Ibrahim Oruko, “Senators now probe SGR racism claims,” The Daily Nation, 10 August 2018. https://www.nation.co.ke/news/Senators-now-probe-SGR-racism-claims/1056-4706062-f9vl3n/index.html.

51 Allan Olingo, “Kenya fails to secure $3.6b from China for third phase of SGR line to Kisumu,” The East African, 27 April 2019. https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/business/kenya-fails-to-secure-3-6b-from-china-for-third-phase-of-sgr-line-to-kisumu-1416820

52 Muhkwana, “Attitudes towards China;” BBC, “Letter from Africa: Kenya's love-hate relationship with Chinese traders,” 24 June 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48743876

53 Adult single tickets cost Ksh3000 (1st Class) and Ksh1000 (2nd Class) as of late 2020. The travel time between Mombasa-Nairobi and vice-versa takes four and a half hours. Prior to the opening of the SGR, the trip took over eight hours and could be much longer depending on traffic and road conditions.

54 Jevans Nyabiage and Keegan Elmer, “African railways feel pinch of China's belt and road funding squeeze,” South China Morning Post, 19 December 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3114551/african-railways-feel-pinch-chinas-belt-and-road-funding

55 Njoki Chege, “Only ‘loyal’ African patrons are allowed in Chinese restaurant after sunset,” Nation, 23 March 2015. https://nation.africa/kenya/counties/nairobi/only-loyal-african-patrons-are-allowed-in-chinese-restaurant-after-sunset-1078450

56 Conteh-Morgan and Weeks, “Is China playing?,” 88-91.

57 George Tubei, “30 Chinese-made armoured vehicles Kenya bought are useless against rocket-propelled grenade attacks as US swoops to the rescue,” Pulse Live Kenya, 18 September 2019. https://www.pulselive.co.ke/bi/politics/a-look-at-chinese-made-armoured-carriers-kenya-bought-which-are-useless-against-rpgs/ehyyfr1

58 Kagwanja, Kenya's 2017 Elections. See also Nyadera, Agwanda, and Maulani, “Evolution of Kenya's Political System.” See also Cannon and Ali, “Devolution in Kenya.”

59 Julius Otieno, “Ruto now turns against Uhuru, criticises ballooning public debt.” The Star, 23 February 2021. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2021-02-23-ruto-now-turns-against-uhuru-criticises-ballooning-public-debt/.

60 Eric Matara, “Kenya Should Renegotiate Its Foreign Debts, Says Mudavadi,” Daily Nation, 18 May 2020. https://allafrica.com/stories/202005190150.html

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Amit, Ritu Singh, and Durga Toshniwal. “Geospatial Sentiment Analysis Using Twitter Data for UK-EU Referendum.” Journal of Information and Optimization Sciences 39, no. 1 (2018): 303–317.

- Akamanzi, Clare, Peter Deutscher, Bernhard Guerich, Amandine Lobelle, and Amandla Ooko-Ombaka. Silicon Savannah: The Kenya ICT Services Cluster. Nairobi: Microeconomics of Competitiveness, 2016.

- Alden, Chris, and Lu Jiang. “Brave new World: Debt, Industrialization and Security in China–Africa Relations.” International Affairs 95, no. 3 (2019): 641–657. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz083.

- Alschner, Wolfgang, Julia Seiermann, and Dmitriy Skougarevskiy. The impact of the TPP on trade between member countries: A text-as-data approach. ADBI Working Paper 745, 2017.

- Bailard, Catie Snow. “China in Africa.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21, no. 4 (2016): 446–471.

- Barton, Benjamin. Political trust and the politics of security engagement: China and the European Union in Africa. Routledge, 2017.

- Brautigam, Deborah. The Dragon’s Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Brown, Stephen, and Rosalind Raddatz. “Dire Consequences or Empty Threats? Western Pressure for Peace, Justice and Democracy in Kenya.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 8, no. 1 (2014): 43–62.

- Bursztyn, Victor S., Marcelo Granja Nunes, and Daniel R. Figueiredo. “How Congressmen Connect: Analyzing Voting and Donation Networks in the Brazilian Congress.” In Anais do V Brazilian Workshop on Social Network Analysis and Mining. SBC, 2016.

- Cai, Peter. Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative [Analysis]. Lowy Institute, March 22. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/understanding-belt-and-road-initiative, 2017.

- Cannon, Brendon J. “Grand Strategies in Contested Zones: Japan’s Indo-Pacific, China’s BRI and Eastern Africa.” Rising Powers Quarterly 3, no. 2 (2018): 195–221.

- Cannon, Brendon J. “Influence and Power in the Western Indo-Pacific: Lessons from Eastern Africa.” In Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, edited by Brendon J. Cannon, and Kei Hakata, 216–232. Routledge, 2021.

- Cannon, Brendon J., and Jacob Haji Ali. “Devolution in Kenya Four Years on: A Review of Implementation and Effects in Mandera County.” African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review 8, no. 1 (2018): 1–28.

- Chin, Gregory, and Ramesh Thakur. “Will China Change the Rules of Global Order?” The Washington Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2010): 119–138.

- Conteh-Morgan, Earl, and Patti Weeks. “Is China Playing a Contradictory Role in Africa? Security Implications of its Arms Sales and Peacekeeping.” Global Security and Intelligence Studies 2, no. 1 (2016): 81–102.

- Dobler, Gregor. “China and Namibia, 1990 to 2015: How a new Actor Changes the Dynamics of Political Economy.” Review of African Political Economy 44, no. 153 (2017): 449–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2016.1273828.

- Dollar, David. China’s Engagement with Africa: From Natural Resources to Human Resources. Washington, DC: The John L. Thornton China Center at Brookings, 2016.

- Eisenman, Joshua. “China–Africa Trade Patterns: Causes and Consequences.” Journal of Contemporary China 21, no. 77 (2012): 793–810.

- Farhadloo, Mohsen, and Erik Rolland. “Fundamentals of Sentiment Analysis and its Applications.” In Sentiment Analysis and Ontology Engineering, edited by Witold Pedrycz, and Shyi-Ming Chen, 1–24. Springer, 2016.

- Farooq, Muhammad Sabil, Yuan Tongkai, Zhu Jiangang, and Nazia Feroze. “Kenya and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: Implications for China-Africa Relations.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 4, no. 3 (2018): 401–441. doi: https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740018500136.

- Fitriani, Evi. “Indonesian Perceptions of the Rise of China: Dare you, Dare you not.” The Pacific Review 31, no. 3 (2018): 391–405.

- Gadzala, Aleksandra. “Survival of the Fittest? Kenya'sjua Kaliand Chinese Businesses.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 3, no. 2 (2009): 202–220.

- Garcia, David, Adiya Abisheva, Simon Schweighofer, Uwe Serdült, and Frank Schweitzer. “Ideological and Temporal Components of Network Polarization in Online Political Participatory Media.” Policy & Internet 7, no. 1 (2015): 46–79.

- Hakata, Kei, and Brendon J. Cannon. “The Indo-Pacific as an Emerging Geography of Strategies.” In Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age, edited by Brendon J. Cannon, and Kei Hakata, 3–21. Routledge, 2021.

- Halperin, Sandra, and Oliver Heath. Political Research: Methods and Practical Skills. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Higuchi, Koichi. “A Two-Step Approach to Quantitative Content Analysis: Kh Coder Tutorial Using Anne of Green Gables (Part I).” Ritsumeikan Social Sciences Review 52, no. 3 (2016): 77–91.

- Higuchi, Koichi. “A Two-Step Approach to Quantitative Content Analysis: Kh Coder Tutorial Using Anne of Green Gables (Part II).” Ritsumeikan Social Sciences Review 53, no. 1 (2017): 137–147.

- Huang, Zhao Alexandre, and Rui Wang. “Advances in Public Relations and Communication Management.” Big Ideas in Public Relations Research and Practice (Advances in Public Relations and Communication Management) 4 (2019): 69–85.

- IPSOS. SPEC Barometer, 2nd QTR 2018. Nairobi: IPSOS, 2018.

- Johnston, Alastair Iain. “Is Chinese Nationalism Rising? Evidence from Beijing.” International Security 41, no. 3 (2017): 7–43.

- Kagwanja, Peter. Kenya’s 2017 Elections: Populism and Institutional Capture: A Threat to Stability. Nairobi: African Policy Institute (API), 2017.

- Kamoche, Ken, and Lisa Qixun Siebers. “Chinese Management Practices in Kenya: Toward a Post-Colonial Critique.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26, no. 21 (2015): 2718–2743. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.968185.

- Kaya, Mesut, Güven Fidan, and Ismail H. Toroslu. “Sentiment Analysis of Turkish Political News. “ 2012 ieee/WIC/ACM international conferences on Web Intelligence and intelligent agent technology, 2012, 174-180.

- Lagarde, Christine. “Kenya at the Economic Frontier: Challenges and Opportunities.” International Monetary Fund, January 6. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/sp010614, 2014.

- Layne, Christopher. “The US–Chinese Power Shift and the end of the Pax Americana.” International Affairs 94, no. 1 (2018): 89–111.

- Liu, Ailan, and Bo Tang. “US and China aid to Africa: Impact on the Donor-Recipient Trade Relations.” China Economic Review 48, no. April (2018): 46–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.10.008.

- Manji, Firoze, and Stephen Marks. African Perspectives on China in Africa. Fahamu: Pambazuka, 2007.

- Miriam, Omolo, Stephen Jairo, and Ruth Wanja. Comparative Study of Kenya, US, EU and China Trade and Investment Relations. Nairobi: Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), 2016, 1-32.

- Mlambo, Courage, Audrey Kushamba, and More Blessing Simawu. “China-Africa Relations: What Lies Beneath?” The Chinese Economy 49, no. 4 (2016): 257–276. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2016.1179023.

- Mohan, Giles, and Marcus Power. “New African Choices? The Politics of Chinese Engagement.” Review of African Political Economy 35, no. 115 (2008): 23–42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240802011394.

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199.

- Mukhwana, Ayub. “Attitudes Towards Chinese in Kenya and the Future of Chinese in Africa.” International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science 5, no. 2 (2017): 17–26. ISSN: 2307-924X.

- Nassanga, Goretti L., and Sabiti Makara. “Perceptions of Chinese Presence in Africa as Reflected in the African Media: Case Study of Uganda.” Chinese Journal of Communication 9, no. 1 (2016): 21–37.

- Niwattanakul, Suphakit, Jatsada Singthongchai, Ekkachai Naenudorn, and Supachanun Wanapu. “Using of Jaccard Coefficient for Keywords Similarity.” Proceedings of the International Multiconference of Engineers and Computer Scientists 1, no. 6 (2013): 380–384. 2013.

- Nyadera, Israel Nyaburi, Billy Agwanda, and Noah Maulani. “Evolution of Kenya’s Political System and Challenges to Democracy.” In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by Ali Farazmand. Springer, 2020.

- Obi, Cyril I. “Enter the Dragon? Chinese oil Companies & Resistance in the Niger Delta.” Review of African Political Economy 35, no. 117 (2008): 417–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056240802411073.

- Onjala, Joseph. “China’s Development Loans and the Threat of Debt Crisis in Kenya.” Development Policy Review 36, no. 52 (2018): O710–O728. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12328.

- O’Trakoun, John. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Regional Perceptions of China.” Business Economics 53, no. 1 (2018): 17–24.

- Pang, Bo, and Lillian Lee. “Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis.” Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2, no. 1-2 (2008): 1–135.

- Parker, Leon, and Elsje Fourie. “Sino-Angolan Agricultural Cooperation: Still not Reaping Rewards for the Angolan Agricultural Sector.” Review of African Political Economy 45, no. 157 (2018): 491–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2018.1500359.

- Pew Research Center. Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/09/16/key-findings-about-africans-views-on-economy-challenges/.

- Pew Research Center. Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2018/10/01/international-publics-divided-on-china/.

- Pew Research Center. Global Attitudes Survey, Spring 2019. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/12/05/attitudes-toward-china-2019/.

- Rich, Timothy S. “Like Father Like son? Correlates of Leadership in North Korea’s English Language News.” Korea Observer 43, no. 4 (2012): 649–674.

- Rinker, Tyler. Package “sentimentr”: Calculate Text Polarity Sentiment (R package version 2.7.1). 59. https://github.com/trinker/sentimentr, 2019.

- Rounds, Zander, and Hongxiang Huang. “We are not so Different: A Comparative Study of Employment Relations at Chinese and American Firms in Kenya.” China-Africa Research Initiative Working Paper Series 10 (2017): 1–32.

- Řehák, V. “China-Kenya Relations: Analysis of the Kenyan News Discourse.” Modern Africa: Politics, History and Society 4, no. 2 (2016): 85–115.

- Sanger, William, and Thierry Warin. “Dataset of Jaccard Similarity Indices from 1,597 European Political Manifestos Across 27 Countries (1945–2017).” Data in Brief 24, no. 103907 (2019): 103907–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2019.103907.

- Sanghi, Apurva, and Dylan Johnson. Deal or No Deal: Strictly Business for China in Kenya?: Policy Research Working Paper 7614. Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2016.

- Sautman, Barry, and Yan Hairong. “African Perspectives on China-Africa Links.” The China Quarterly 199 (2009): 728–759.

- Signé, Landry. The Potential of Manufacturing and Industrialization in Africa: Trends, Opportunities, and Strategies. Brookings Institute: Africa Growth Initiative, 2018.

- Siringi, Elijah M. “Kenya-China Trade Relations: A Nexus of ‘Trade not Aid’ Investment Opportunities for Sustainable Development.” Journal of Economics and Development Studies 6, no. 2 (2018): 1–10.

- Slayton, Caleb. “Africa: The First U.S. Casualty of the New Information Warfare against China.” War on the Rocks, February 3. https://warontherocks.com/2020/02/africa-the-first-u-s-casualty-of-the-new-information-warfare-against-china/, 2020.

- Strapparava, Carlo, and Rada Mihalcea. “Semeval-2007 Task 14: Affective Text.” In Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Semantic Evaluations (SemEval-2007), 70–74, 2007.

- Syroezhkin, Konstantin. “Social Perceptions of China and the Chinese: A View from Kazakhstan.” China & Eurasia Forum Quarterly 7, no. 1 (2009): 29–46.

- Taylor, Ian. China’s new Role in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2009.

- Wang, Fei-Ling, and Esi A. Elliot. “China in Africa: Presence, Perceptions and Prospects.” Journal of Contemporary China 23, no. 90 (2014): 1012–1032.

- Wanjiku, Sylvia, 2018. Effect of Kenya’s Bilateral Relations with China on Economic Growth of Kenya (2000-2015). Ph.D. dissertation. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenyatta University