ABSTRACT

This article critically analyses the history of the Ethiopian sugar industry, with emphasis on drivers, decision-making and processes of incorporation and exclusion aiming to transform lowlands. We argue that the government has used a state-led modernization and expansion of the sugar industry to consolidate the power of central governments. Through the creation of sugar-based agribusinesses, the changing regimes have sought to extend their control over natural resources, increase the movement of labour, and stimulate economic growth. This has led to deepened state structures and considerable transformation of power relations, causing marginalization of the affected communities. In Ethiopia’s post-2018 political and economic transition, this modernist and expansionist programme found itself in a set of deep economic and financial crises, leading to government initiatives to privatize the sugar industry. In response to the privatization initiatives, local elites articulate and contest the historical process of marginalization and compete in demanding redress for the adverse incorporation of the communities. They do so to expand the community space for agency and enforce their interests in gaining from, and perhaps dominating a privatization process through takeover strategies. The past modernist development approach that caused marginalization is likely to affect a new stage of lowland transformation.

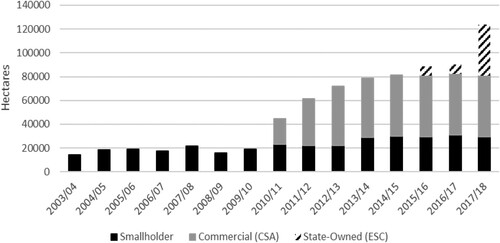

The establishment and expansion of the sugar industry have been one of the largest and most significant modernization projects in the Ethiopian lowlands. While it expanded rapidly during the past 20 years, the industry also has a deeper history that goes back to when a centre of sugarcane production was established in the Awash Valley during the Italian occupation in the 1930s.Footnote1 After the Imperial government had retaken control of the country, it authorized a Dutch company first to activate the sugar manufacturing industry at Wonji in the 1950s, and then to expand it to Shoa and Metahara in the late 1960s. During the rule of the military government, the Derg (1974-1991), the state nationalized and expanded the sugar industry into the Fincha Valley, a development that was completed during the late 1990s. During the period of the EPRDF government (1991–2019), several expansions and new factories were made, particularly after 2004. Government’s developmentalist narrative has justified massive investments in the establishment of a state-led and rapidly expanding sugar industry, which by 2020 earmarked more than 300,000 hectares of land in Lower Awash, Fincha, Beles and Omo Valleys, as well as in the West and Northwest (see ).

Table 1. ESC data of sugarcane plantation and inclusive development packages.

With three successive governments investing in the sugar industry, the question about why sugar has continuously remained a strategic political and economic tool of the state is critical. This question is particularly pertinent since, despite decades of aspiration and effort, the governments have not succeeded in making sugar become a major export, but rather meeting growing domestic demand of sugar, and exploiting economic advantages of its by-products including ethanol and electricity. Academic literature is also critical of the development approach taken by successive Ethiopian governments in promoting large-scale commercial agriculture. Scholars have characterized state-led agricultural development programmes as efforts in social and environmental re-engineering,Footnote2 exploitation of the margins,Footnote3 attempts of managing ‘land and labour’,Footnote4 utilizing development as a means of ‘assimilation and integration’,Footnote5 ‘territorial annexation’,Footnote6 and a thickening of the state authority and control over peoples and resources in the lowlands.Footnote7 These scholars view the programmes as part of the longstanding centre-periphery relations and processes of Ethiopian state formation, centralizing power and marginalizing lowland communities. They see development policies as a modernization project aimed to create development corridors, ‘extract resources’ from river basins and irrigable lowlands, in order to generate economic opportunities for a young and growing population and achieve a structural transformation of the economy.

Following the 2018 political transition, the government launched an economic reform, including plans for the privatization of (part of) the sugar industry. In the process, local communities articulated their concern about the marginalization they have experienced and local business elites entered into the competition about acquiring control of the most productive factories by establishing a company.Footnote8 The company also involves local communities and political actors, who raised the question of ‘who is the buyer’, ‘which factories’ and ‘whose land’.Footnote9 In the process of these critical engagements, the local actors articulated their issues of power and agency. The company strategically presented the historical relationships and marginalization of its majority shareholders in order to claim an equitable consideration of the company in the privatization process.Footnote10 The strategy emphasizes redressing the adverse incorporation of the affected communities but may also reflect a hostile attempt to dominate the local involvement in the privatization process. Therefore, in the post-2018 developments, how to balance the economic objectives of the sugar industry with the economic, social and political issues of the affected communities remains critical.

This article reviews the history of the Ethiopian sugar industry with the aim of analysing the modernist political and economic model of the industry, the policy justifications, crises and issues of power and agency inherent in the development model and their implications for the post-2018 privatization process. We interrogate why a commodity vulnerable to boom-and-bust was prioritized and what crises and issues of power and agency arose due to the development approach of the industry. Based on the concept of agency as ‘power to’ and ‘power over’,Footnote11 it also analyses how communities articulated their agency and power in response to the creation of the sugar industry and its estates, including in the post-2018 developments. Of primary sources, we rely mainly on government policy documents and reports as well as the plans, reports, announcements and fact sheets of the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation (ESC). To assess the production by sugar factories and smallholder suppliers, we use several data sources including Central Statistics Agency (CSA) reports for smallholder and private-sector production, ESC reports for state-owned plantations, and the National Bank of Ethiopia for export trends. Limited data presents a challenge in assessing government objectives and a number of other factors, and hence we use the literature to fill these gaps. The limited data also affects the process of validating the quality of data, including policy trends and developments.

We argue that a modernist political and economic approach has informed the sugar industry and nation-building project of shifting governments of Ethiopia. The modernist political and economical approach has been prone to economic, political and social crises that produces and reproduces issues of marginalization and shapes the ways actors of the lowlands communities articulate their agency and power in the post-2018 privatization process of the industry. With this intent, the following section presents the history of the sugar industry in Ethiopia, period by period, noting the main features of its context and growth. Next, we discuss the modernist political and economic strategies and its crises, and we take this up to the post-2018 privatization developments and discuss how the local actors participate in process. Finally, we analyse the implication of modernism with the question of power and agency in the lowland transformation process.

The creation of an industry: the early days of the sugar buzz

Sugar cane plantations in Ethiopia date back to the Italian occupation of the Awash River Valley. After its return to power, in 1950, the Imperial Regime entered into a concession with HVA, a Dutch company, with the aim of producing sugar for import substitution.Footnote12 The concession’s attractive foreign investment conditions included lease rights on 5000 hectares of land, a monopoly of sugar production within a radius of 100 miles, a tax holiday, and duty-free import of capital goods.Footnote13 The Wonji plantation and factory began operations in 1954. In 1962 it expanded by annexing 1600 hectares of additional land and creating the Shoa Sugar Factory, which together formed the Wonji–Shoa Sugar Factory.Footnote14 Increasing domestic sugar demand, and the suitability of the land and climate for sugarcane cultivation, spurred a further expansion of the sugar industry to the Metahara plains of the middle Awash Valley, where the Imperial Regime granted a concession to HVA to acquire another 11,000 hectares of land in 1965 and the Metahara Sugar Factory began operations in 1969.Footnote15

In 1975, the socialist Derg regime nationalized all the Ethiopian sugar factories and their plantations. Three years later, by Legal Notice No. 58/1978, the then Ministry of Industry established the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation (ESC), which would manage the Wonji–Shoa and Metahara Sugar Factories. The ESC pursued the further expansion of the sugar industry in Fincha Valley by conducting a comprehensive study in collaboration with a British consultancy firm in 1978. However, due to financial and political crises, the construction of a factory did not begin until 1988 and production not until 1998.Footnote16 Fincha Sugar Factory had 12,170 hectares of plantation and was the first ethanol-producing plant in the country.Footnote17 Following the regime change in 1991, the transitional government dissolved the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation, thereafter creating the Metahara Sugar Factory (Regulation No. 88/1992), the Wonji–Shoa Sugar Factory (Regulation No. 89/1992) and the Fincha Sugar Factory (Regulation No. 199/1994) as distinct state development enterprises.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the industry made use of outgrower schemes and various other employment opportunities in order to counter local resistance by incorporating agro-pastoralists in the sugarcane agribusiness. The Wonji–Shoa sugarcane factory offered cane-cutting employment opportunity for the lowland people of Jille–Oromo.Footnote18 In the 1960s and 1970s, the Sultan of Awssa resisted displacement by the expanding Wonji–Shoa and Metahara sugar factories. In Afar, resistance by the powerful elite forced the Imperial Regime to recognize their land interests.Footnote19 In 1975/1976, a mandatory scheme with seven outgrower associations was established, giving some Afar people access to irrigation, machinery and household support.Footnote20 However, Bahiru Zewde criticized these initiatives as failures from the beginning due to the unsuitability of the schemes and drastic alteration of pastoral livelihoods.Footnote21 The factory had unrealistic expectations about the skills of the people involved as outgrowers and provided no substantial training or skill development. The pastoralists had neither the inclination nor a sufficient number of free hands for the laborious task of cane-cutting; consequently, the company ended up bringing young labourers from densely populated areas such as Kambata and Wolaita, with far-reaching consequences for social relations.Footnote22

The post-2004/2005 sugar industry revolution

Expanding the existing factories

An expansion of the existing sugar factories began with the establishment of the Ethiopian Sugar Industry Support Centre in 1998. It was a share-company established by the state-owned financial institutions Ethiopian Development Bank and the Ethiopian Insurance Company to provide technical support for the development and expansion of all sugar factories, thereby safeguarding their shareholding investments. In 2005, the government Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP) included a sugar development master plan to expand the Wonji–Shoa, Metahara and Fincha sugar factories, with the aim of producing 1.2 million tons of sugar, 143 million litres of ethanol, 86 MW electric power per year as well as to ‘increase the export share of the country in the international sugar market by 2.5%’ by the end of 2009/2010.Footnote23

In 2006, the Government of Ethiopia obtained a loan of 640 million USD from the Government of India with the objective of expanding sugar factories, first to meet domestic demand and then to export sugar and ethanol.Footnote24 In the same year, a contract was awarded to an Indian firm for the redevelopment and expansion of the Wonji–Shoa Factory, which had been operational for more than half a century and required renovation work that was completed in 2013.Footnote25 This sugarcane plantation expansion over three phases (in 2008, 2011 and 2013) covered more than 9500 hectares of land and involved new outgrowers, the number of associations increasing from 7 to 31.Footnote26 In Metahara, an additional 10,000 hectares sugarcane plantation was added and an ethanol-producing plant was completed in 2010 at the site. At Fincha, a project expanding the sugarcane plantation to 21,000 hectares was also awarded to an Indian firm.Footnote27

Constructing new factories

PASDEP also included an ambitious plan to construct new factories with high production capacities. In 2006, the Ministry of Council established Tendaho Sugar Factory through Regulation No. 122/2006. After several delays, the factory started production in 2014, and in 2019 it was reported to have 10,000 hectares of sugar cane,Footnote28 with plans to expand to 25,000.Footnote29 To promote the development of the sugar industry, state firm support services were reorganized from the Ethiopian Sugar Industry Support Centre to the Ethiopian Sugar Development Agency, a state development enterprise (proclamation 405/2006 on 27 July 2006). The proclamation expanded the Agency’s mandate to include planning and developing new sugar development projects and providing training and marketing support.Footnote30 In 2009 the Agency launched the Kesem Sugar Development Project as an expansion of the Metahara sugar factory, with the aim of putting 10,000 hectares of sugar cane under irrigation by the Kesem River.Footnote31 Due to its distance from Metahara, an autonomous factory was constructed and commenced operations in 2015. The Kesem Factory is in the process of expanding its total sugarcane plantation to 20,000 hectares of land and involves five outgrower associations in supplying additional sugarcane.Footnote32

The big push

After 2010, a big push for the development of new sugar factories was institutionalized by dissolving the Ethiopian Sugar Development Agency and establishing the Ethiopian Sugar Corporation (ESC) with a name and operational structure similar to the agency once created by the Derg government. The ESC took over the rights and obligations of the Ethiopian Sugar Development Agency and centralized the sugar factories mandates.Footnote33 The ESC launched a massive and ambitious plan to construct ten sugarcane factories during the period of the first Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP I, 2010/112014/15). This included seven new factories, four in Omo Valley, two in Beles Valley and one in Welkait, in addition to the two, then on-going factory constructions of Tendaho and Kesem, as well as the Arjo Dedesa sugar factory bought from a private foreign company.Footnote34 Through these expansions and new factories, the ESC planned to produce 2.25 million tonnes of sugar annually, meet domestic demand by the end of 2013, increase the annual production of ethanol to 181,604 kilolitres, generate 101 MW of electricity, and export 1.25 million tonnes of surplus sugar to the international market.Footnote35

The Arjo Dedesa Sugar Factory had been established in 2009 by a Pakistani investor, Al-Habasha Sugar Mills. Before it started producing, it was sold to the ESC in 2012 and began operations in 2015 with 3000 hectares of sugar cane, and it is expanding to 13,000 hectares.Footnote36 The Omo River Basin was selected for the development of four sugar factories under the Omo Kuraz Sugar Development Project (OKSDP), the largest agricultural development scheme ever implemented in Ethiopia.Footnote37 The initial plan was to construct five factories, which would cover 245,000 hectares of land.Footnote38 Later, the planned area was reduced to 125,000 hectares by cancelling Factory 4.Footnote39 Each factory was planned to cover 20,000 hectares of land, except Factory 5, which would cover 40,000 hectares. As of early 2019, 96% of the construction of Factory 2 had been completed, Factory 3 had reached 94% and Factory 5 remained at about 25%.Footnote40 A 2019 government report claimed that Factory 1 was 80% completed,Footnote41 but it has been in an indeterminate state since 2016, when it was reported to the House of Peoples Representatives that the contractor METEC, a military-run corporation, had failed and the contract cancelled.Footnote42 By 2019, reports indicate the plans for other factories on about 36,000 hectares of sugarcane in Beles Valley, and the first factory construction had reached more than 67% and the second closer to 25%.Footnote43 In addition, the Tigray Region hosts Welkait Sugar Factory, which was planning to grow sugarcane on 39,500 hectares with irrigation from the Tekeze, Kalema and Zarema Rivers. As of 2019, reports claimed that 88% of the first phase and 50% of the second phase had been completed.Footnote44 These post-2010 developments amounted to a state-led revolution of the sugar industry and a push for a massive expansion in the lowlands of Ethiopia.

Investing in sugar: modernist political and economic strategy

The sugar industry has been characterized as a modernist political and economic strategy throughout its development. In the days of the Imperial Government, the industry had represented sugar as an ‘exotic’ and ‘modern’ commodity that fitted with the regime’s determination to ‘modernise’ and ‘accustom’ Ethiopians to modern tastes. The Imperial Government’s second five-year development plan (1962–1967) invoked agro-industrial projects, including the sugarcane industry, with the goal to ‘modernise’ the ‘traditional’ livelihoods through the introduction of large-scale mechanized commercial farming.Footnote45 Even though the ethno-political discourse of the EPRDF challenged some of these modern centre-periphery relations, from 2000 to 2010 the EPDRF piloted new sugar development projects following a similar modality, pursuing a centralized expansion and establishment of factories with the justification of an ‘antipoverty struggle’, ‘utilising natural resources’ and facilitating ‘equitable development in the relatively underdeveloped regional states’.Footnote46

Post 2010, the government re-oriented itself from a decentralized ethnic-based federalism to a more centrist and explicitly modernist developmental state model.Footnote47 The Growth and Transformation Plans (GTP) envisaged the sugar industry as a strategic sector for development in the country by exploiting the resources of irrigable lowlands and river basins and fostering a structural transformation of the economy. The lowlands were defined as ‘sparsely inhabited’ areas with only ‘15% of the total population’ characterized as ‘structurally weak’, or ‘unused’ but comprising ‘60 to 65% of the total landmass’ or ‘80% of the arable land’ of the country.Footnote48 The dominant government narratives defined the sugar developments as a key tool to modernization through irrigation of river basins in the extensive lowlandsFootnote49 in order to provide employment, extract resources, generate revenues and advance a social, economic and political transformation of the pastoral frontier.Footnote50

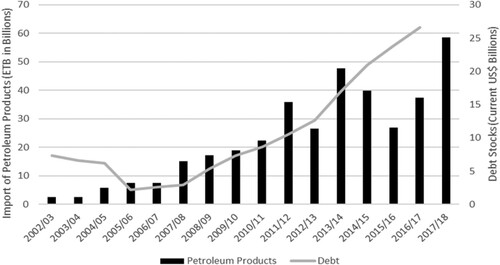

One may question why, within this modernist discourse, sugar production has continued to be envisioned as a key to developing the nation. The continued expansion of the industry is partly justified by a macro-economic narrative of growing domestic demand for sugar, ethanol and electricity that presents import substitution as the appropriate aim of the government. However, investments in the sugar industry took place at certain points in time that generally correlate with high international commodity prices. There was a sugar price spike in 1963, and two years later, Metahara was established; the highest prices of the last half-century were seen in 1974, after which the first assessment for Fincha was undertaken; prices rallied from 1985 to 1990, the period when investments in Fincha took place (). In this economic perspective, expansion could serve both the aims of domestic supply via import substitution while also envisioning goals of high future export revenues. Despite the massive investments made, Ethiopia still relies on imports of sugar to the amount of 275,000 tons in 2015, 300,000 tons in 2016, 170,000 tons in 2017, 300,000 tons in 2018 and 200,000 in 2019.Footnote51

The post-2010 investments manifested the largest sugar adventure so far and coincided with good access to an international market with high prices. While the timing of investments indicate export revenue generation a major goal, this is not the only motivation, as demonstrated by the on-going commitment to past and new projects amidst price crashes. In 2006/2007, the EU Agricultural Minister introduced a reform to reduce the sugar output of EU member states through a voluntary restructuring scheme.Footnote52 This reform permitted the global south to compete in the EU market, stimulating increased sugar production.Footnote53 In particular, the EU’s Everything But Arms (EBA) economic partnership initiative for ‘least developed countries’ offered duty-free and quota-free market access. Under this policy, Ethiopia exported between 14,000 and 24,000 tonnes of sugar per year in the period 2001–2009.Footnote54 Following these experiences with duty-free export markets, the first GTP considered the potential of the sector to ‘contribute to export diversification and foreign exchange earnings’.Footnote55 Similarly, the second GTP envisaged earning 586.2 million USD by the end of the plan year through exporting sugar to the global market. Moreover, the Sugar Technology Roadmap set a vision to make the country among the top 10 most competitive and technologically advanced sugar-producing countries, with a goal of holding a 2% share of the global market by 2016. In addition, the USA tariff-rate quota options permitted several countries to access the US sugar market. Coupled with these global market opportunities, the global price of sugar saw a record-high increment in 2010 ().

Increasing the production of ethanol and bagasse – a renewable fuel that is burnt to produce electricity – is another motivation behind the big push to increase the production of sugar. Ethiopia has no significant oil reserves and relies on imports to meet its demand, making petroleum products the largest category of imports by value in recent years.Footnote56 The production of ethanol has been used to reduce import demand by blending locally produced ethanol with imported fuels as the demands for fuel imports become pressing. Studies have found that ethanol production in Ethiopia is viable and a way to reduce spending on imports.Footnote57 Fincha was the first ethanol-producing plant and ethanol has been exported since 2005, largely to Europe.Footnote58 Due to rising oil prices, ethanol blending with fuel commenced within Ethiopia in 2009. Since then, domestic energy consumption has increased, and the last two GTPs aimed to increase the production of ethanol. However, the production of ethanol is not solely for domestic consumption, as development plans and the Sugar Technology Roadmap also aim to increase exports to generate foreign currency.

Apart from these economic factors, a critical analysis of the modernist political and economic approach and history of the Ethiopian sugar industry displays its embedded social and political rationale, which includes extending control over natural resources, managing settlement patterns, and deepening state power over the lowlands communities. The modernist policy discourses employed by the industry is centred on new economic, social and political opportunities for these communities through employment, agribusiness and the development of social services and infrastructure. It portrays a future of mass employment and opportunities for local people who benefit from improving labour market, transfer of skills, and ultimately being enabled to modernize their way of life.Footnote59 The government expressed similar goals of balancing ‘land and labour’,Footnote60 in the way PASDEP and the two GTPs frame the sugar factories as development corridors that create employment and new settlement opportunities for the young and growing population of the central highlands.

Policy narratives present outgrower schemes as a way of linking the private sector with smallholders.Footnote61 The ESC frames the outgrower schemes – implemented through 67 outgrower associations with 15,011 household members in Wonji–Shoa, Fincha, Tendaho, Kesem and Omo Kuraz areas – as a collaborative strategy with lowland people.Footnote62 However, the observed history suggests that the industry employed outgrower schemes rather as an instrument to counter resistance against the displacement created by the expansion of Wonji–Shoa and Metahara sugar factories.Footnote63 Materially, the purported measures to compensate agro-pastoralists for the dispossession of landholdings appear more like facilitative instruments for the smooth entry of the sugar industry than real and inclusive agribusiness strategies. The participation of affected communities in the outgrower schemes is no more than 6% of the affected households ( and ).

Figure 2. Total hectares earmarked for sugar cane plantation. Source: Central Statistics Agency (CSA) for commercial data; ESC reports for state-run projects.

The top-down, industrial power hierarchies establishedFootnote64 enabled the industry and the central government to significantly expand its control over land and natural resources. This critical assessment of the modernist model of political and economic development is consistent with the concept of pastoral frontier dynamics, seeing the industry’s modernist, discursive approach as a social and environmental re-engineering programmeFootnote65 aimed to increase the control over natural resources and population,Footnote66 thickening state powerFootnote67 and enhancing its capacity to exploit the lowlands.Footnote68 The industry’s modernist policy discourse of ‘social mobilisation’, ‘awareness’, ‘development army’ and ‘social service delivery’ () expounds on government penetration and control over communities based on the reinforced agency of the state.Footnote69 However, the ‘resettlement’ and ‘service delivery’ programme actually ‘relocates’ agro-pastoralists and ‘disposes’ them of their communal landholdings;Footnote70 so that the attempts at ‘re-skilling’ rather facilitate ‘de-skilling’ from their long-established ‘metis’.Footnote71 Thus, ‘social mobilization’ and the creation of ‘development army’ structures appear rather like regime practices to dominate local institutions and actors through expanding state structures and bureaucratic power.

Crisis and new directions of the sugar industry

Social and political crisis of the sugar industry

Even if the sugar industry presents itself as an inclusive development partner with lowland communities, reports show that the modernist trajectory of resource extraction and management of the population in re-located settlements fostered social crises of displacement and marginalization, which have occurred since the early days of the sugar buzz. The Wonji sugarcane plantation and the expansion of Shoa Sugar Factory intensified the competition over land by annexing close to 7000 hectares of pastoral land.Footnote72 Dispossession became a serious phenomenon during the EPRDF period, in which the total ESC estate increased to more than 280,000 hectares of land ( and ). The modernist trajectory involved land dispossession and forced resettlement and villagizationFootnote73 and triggered severe contestation from below.

As argued above, the pastoralists observed that the outgrower schemes were incompatible with their livelihoods and some of them contested and left the scheme in the wake of the contestation by the Sultan of Awssa.Footnote74 More than 50 years later, the participation of communities in this scheme is insignificant and fails to increase the local communities’ participation and their economic gains. Chiefly, the scheme is criticized for failing to consider communities’ freedom to enter into and influence contractual agreements. The outgrowers’ contractual relations, land rights, modes of production, market chains, payment for labour, and access to technology and irrigation, are all centrally determined by the industry.Footnote75

Private sector participation in outgrower scheme remained insignificant. The ESC estate covers more than 280,000 hectares and its actual sugarcane plantation area is more than 120,000 hectares of land ( and ). However, private sector involvement affects less than 12,000 hectares, of which Hiber Sugar Company farms 6200 hectares of formerly uncultivated land in Amhara Region.Footnote76 In 2014, Amibara agreed with Kesem Sugarcane factory to produce sugarcane on its 6000 hectares cotton farm in Afar region.Footnote77 By 1991 communities cultivated only 1020 hectares of land in outgrower schemes,Footnote78 which after the expansion and big push had increased to only 17,250 hectares in 2019 (). Therefore, as Weis argued, the ‘vanguard capitalism’ of the state and ruling political party (EPRDF) dominates developmental investments, fuses state and market, and weaken private investments.Footnote79

Above all, the communities had neither the inclination nor a sufficient number of free hands for the laborious task of cane cutting, and hence it created new settlements that changed the forms of social interaction as well as competing social relations. In the early days, the industry brought young labourers from Kambata and Wolaita, which had lasting consequences for social relations, including becoming associated with the eviction and marginalization of the lowland people of Jille–Oromo.Footnote80 Similarly, the large movement of labourers during the EPRDF’s big push caused new settlement patterns, which intensified social competition and exclusion in and between communities.

Economic crises of the industry

Apart from these issues of exclusion, during the period of the EPRDF regime, the sugar industry endured multiple crises with regard to meeting its economic goals. During the PASDEP period, the industry encountered a series of delays and experienced poor performance in expansions and new projects. The GTP I assessed the progress of the sugar master plan as meeting only 15% (177,120 tons) of the sugar production planned for 2009/2010.Footnote81 A similar crisis emerged following the award of contracts for the ten factories, with concerns raised regarding the feasibility studies, planning, technical capacity, and prior experience of the contractor (mainly METEC), as well as regarding funding sources, and the social, political, economic and environmental costs of the projects. In 2013, the Ethiopian Industrial Development Strategic Plan (2013–2025) assessed the situation and acknowledged that the unreasonable delays and poor performance of the sugar factories were due to poor leadership, financial constraints, and infrastructural limitations.Footnote82

The ESC’s self-assessment of the performance of the sugar industry plan at the end of the GTP I period (2010/11-2014/15) showed that only 18% of the sugar, 14% of the ethanol, and 30% of the electricity production targets were met.Footnote83 The plan was to export surplus sugar, but instead, the government banned the export of sugar and continued to rely upon imported sugar.Footnote84 In comparison, two stimulants, coffee and khat,Footnote85 have remained Ethiopia’s most important export crops. Moreover, the plan to increase the production of ethanol to blend it with fuel was below the target set and therefore did not have the desired impact on the steadily increasing fuel import and debt crisis of the country (). The Growth and Transformation Plan II (GTP II, 2015/16-2019/20) did not fully capture the depth of these crises, yet it acknowledged the delays in the expansion and construction of new factories and their impacts. GTP II associated these delays with poor ‘project planning and management’,Footnote86 and overlooked the complex social, political, economic, and environmental factors of the crisis. Instead, it distinguished the massive sugar development plans of GTP I as the grand cornerstone of the government’s developmental discourse.Footnote87 Moreover, it opted for an ambitious plan to increase sugar production to 4.9 million tons, to generate 586.2 million USD in foreign currency from exports, to produce 474 MW of electricity, and produce 442 million litres of ethanol by the end of 2020.Footnote88 However, the crises that began during the PASDEP period continued into the GTP II period and became a key source of the national debt in the post-2018 Ethiopia period. By the end of December 2019, without the interest rate, the ESC owed a debt of 81.64 billion Birr [US$2.6 billion] for local banks and US$ 2.1 billion for foreign banks; and yet, the estimated asset of the sugar factories [88 billion Birr; US$2.85] could cover less than half of the total interest of the total 144 billion Birr debt.Footnote89 Therefore, as Kamski assesses the southwestern developments,Footnote90 the industry is a failed development intervention.

Post-2018 reforms – privatization

Following nationwide protests from 2016 to 2018, the new government led by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed from April 2018 presented a different direction for the sugar industry by proposing to liberalize the state-dominated economy and grant a greater role to the private sector. The ESC was experiencing a set of deep economic, social and political crises. As a result, the large, state-owned sugar investments were being put up for potential sale – with the alternatives of full or partial privatization options.Footnote91 The government justified privatization of the industries mainly by referring to the goals of reducing external debt, improving credit to the private sector and creating jobs, thus putting the economy on a sustainable path.Footnote92 Therefore, the privatization reform has largely focused on generating foreign currency and managing the debt crisis of the sector. The medemer, or synergy, political and economic discourse and the 10-years indigenous economic policy of the Prosperity Party (the successor of EPRDF since 2019), promised open, transparent and competitive process of privatization, including 5–6 sugar factories.

In April 2019, the Ministry of Finance dispatched a Request for Information (RFI) to potentially interested buyers, and the long-standing and still operational factories of Wonji–Shoa, Metahara, and Fincha attracted the interest of domestic and international companies.Footnote93 The government has prepared draft legislation to regulate the privatization and future course of the sugar industry, which aims to enhance productivity by strengthening private sector participation, supporting outgrowers, and establishing a regulatory agency called the Ethiopian Sugar Board.Footnote94 Via these changes, the proclamation aspires to meet domestic demand, generate exports, create jobs, and attract investors. Later, according to a Roadmap for Privatization, the government decided to retain the most productive and economically strategic sugar industries but to transfer in different phases only the sugar factories Kuraz 1, 2 and 3, Beles 1 and 2, Arjo Dedessa, Kesem, Wolqaite, and Tendaho.Footnote95

However, this plan remains controversial. A member of the House of People’s Representatives commented that, ‘the construction of the sugar plants is financed by billions of dollars of foreign debt while some of them are stagnated and have lagged behind their official timetable’; and asked ‘how are we going to transfer them just because we only have the desire to do so?’Footnote96 The Minister of Finance and Economic Ministry, Ahmed Shide, replied that ‘the government has decided to privatize the companies in their prevailing status’.Footnote97 The reply appears to play down the complex socio-economic and political crises of the sector. Most importantly, the prerequisites to privatize sugar factories implicate the embedded complex economic, social and political concerns among the lowland communities’ in the privatization. The wealth estimation report of Booker Tate Limited, a British company hired to consult the privatization process, recommends prerequisites to improve market value of the sugar factories; and the Privatization Roadmap of ESC acknowledged these conditions, including the rule of law around sugar factories and proof of land ownership of sugarcane plantations.Footnote98

The Roadmap for Privatization claims that a problem of lawlessness exists in communities living around the factories; stresses the difficulty of maintaining the regular operation of the factories; and prescribes a concerted effort of the federal and regional government to ensure the rule of law. Pointing in a similar direction, the Tendaho plant was compelled to suspend its production in April 2019.Footnote99 Of course, during the post-2018 period, unprecedented lawlessness and unrest in most parts of the country, threatens the reform measures. Report also confirms that repeated attacks by rebel Oromo Liberation Army forced Fincha sugar factory to halt production in February 2022.Footnote100 Besides, the Roadmap acknowledges the challenge of proving the land use rights of the factories and sugarcane plantations, and the serious difficulties of acquiring land certificates. After all the years of development, only Wonji-Shoa and Fincha sugar factories have title deeds for their projects; the remaining 11 factories, including Metehara, lack land certificates.Footnote101 The Roadmap accuses the regional governments and local administrations of refusing to comply with the repeated requests for land certificates by the ESC and sugar factories. For instance, when requested to issue a land certificate for Tendaho and Kesem sugar factories, the Afar region replied that ‘we cannot give the land, because it belongs to the clans’.Footnote102 Several factory development maps contradict local realities by encroaching on communities’ residence, farm and pastureland. Hence, the Roadmap calls for the direct intervention of the Office of the Prime Minister in securing title deeds.

With the privatization reform agenda, a company named Ethio Sugar Manufacturing Industry emerged and vigorously joined the race to acquire the most productive sugar plants, namely Wonji–Shoa and Metehara. The company was formed and dominated by local business elites (primarily from the Oromia region), who entered into negotiations with the ESC and the Office of the Prime Minister and offered to purchase both industries.Footnote103 They claimed an inclusive business strategy by associating themselves with the wider communities who has an economic, social and political tie with these factories as major shareholders of the ompany. However, the ESC and the federal government expressed concern about the company’s business strategy; and in the process, controversies were observed.

Initially, the ESC opposed an advertisement for the subscriptions of the company shares. It asked the Broadcasting Authority to ban the company’s advertisement, alleging it to be an illegal use of the image of the ESC and the trademark of Wonji-Shoa Sugar Factory. This caused pressures that included the proliferation of domestic and international phone calls and in-person inquiries into speculations and politicization of the privatization of Wonji-Shoa and Metehara sugar factories.Footnote104 The association of the sugarcane outgrower farmers, factory workers, and local civil servants with the speculations and politicization of the privatization created tensions among the sector management and affected the regular operations of the factories. As a result, in September 2019, the Broadcasting Authority temporarily terminated the company advertisement.

On top of this, the federal government’s decision to retain the most productive industries and privatize only the remaining encountered competing interests, narratives, and reactions from the Company. In a press statement in July 2019, the company opposed the federal government’s decision, sought an inclusive business and raised the problem of marginalization and its strong social base with the communities affected by the factories.Footnote105 In the statement, the Company claims the mobilization of more than 60,000 local communities including sugar factories outgrower associations, farmers, factory workers and local government employees as the majority shareholders of the company; and based on personal loan agreement, it arranged access to finance from Awash, Oromia Cooperative and United Banks.Footnote106 By stressing shareholders strong historical, social, economic and political ties with the factories, the press statement asked the government to give the company an equitable space in the privatization process.Footnote107 This strategy aims to create pressure by promoting and politicizing its shareholders and the communities in the negotiations taking place in the privatization process.

Conclusion

This article argues that the modernist development approach of the sugar sector has been a political and economic strategy of the last three successive central governments of Ethiopia. They have envisioned the industry as a strategic tool to modernize land, environment and society, and claimed to pursue economic goals of increasing sugar production, expanding market access, generating foreign currency and increasing economic growth. Furthermore, their modernist social, environmental and political ambitions are embedded in these economic goals of the state-industrial complex. Promoting the economic goals of the sugar industrial complex, the state marginalized, and in some cases suspended, communities’ power to make and exercise choices about their resources and livelihoods. The policy discourses prioritized the transformation of pastoralists and agro-pastoralist habitation and livelihood strategies into those of settled outgrower farmers and labourers. Consequently, the discourse, resources and processes of the industrial sugar expansion have caused significant marginalization of the power and agency of affected people.

Advancing these modernist policy discourses, the sugar industry has been a discursive and material instrument to enter into the social and environmental settings of the local communities, redefine, and constrain the agency of actors. It particularly affected the distribution of resources and power by converting the property regime underpinning communal land use and management to state-controlled property regime, although it was only partially formalized. The land policy, which assumes state ownership of land and appropriation of land and land-use rights for smallholder,Footnote108 facilitated the state-led land identification, resettlement of the pastoralists and transfer of the land to the ESC estate without proper consultations.Footnote109 Besides, its modernist labour market is inconsistent with the community’s livelihood and intensified social conflict and contestation of power relations. The poorly functioning and centralized outgrower agribusinesses provide limited protection of the land rights of the affected communities, and significantly diminishing their ‘bundle of rights’.Footnote110 The industry’s ‘social mobilisation’ and ‘awareness’ programmes reinforced the agency of the state at the expense of community institutions and processes of decision-making. The modernist political and economic approach of the industry has demonstrated its deficient commitment to meeting the constitutional obligation ‘to enhance the capacity of citizens for development and to meet their basic needs’.Footnote111 Accordingly, the sugar project reiterates a state programme of a discursive and material ‘territorial annexation’,Footnote112 thickening the authority and control over peoples and resources,Footnote113 and amounting to a problematic social and environmental re-engineeringFootnote114 that increasingly shaped socio-economic and political relations between centre and periphery.

The post-2018 reforms of the industry overlook this historical trajectory of marginalization caused by the modernist political and economic approach of the industry. The privatization reform was partly launched to address economic crises of the central government by enhancing the participation of the private sector, reducing the burden of public debt, improving the financial and project management capacity of the ESC. Local business and political elites are now using the claims about past marginalization as moral and political weapons to challenge the industry strategies and political reforms and seek to be included in the privatization process. The prevalence of lawlessness in the contexts of the sugar estates implies deeply embedded uncertainties and social, economic and political concerns of the communities that were affected, and often displaced, by the state-led construction of a sugar industry in pastoral lowlands. The contestation over the central state demands to issue land title deeds to 11 factories and plantations displays the resistance of regional and local political actors against the historical trajectory of exclusion and dispossession of land. In this context, the company and its business elite use a strategy and discourses of equitable inclusion to try to advance their interest in retaining or expanding their dominant positions in the economically strategic industries.

Accordingly, the contestations by communities and political and business actors are interpreted here as responses to the embedded historical issues of marginalization and as articulations of agency and demands for more power in the post-2018 privatization process of the industry. The claim about past adverse incorporation of communities in the sugar industrial projects, and the presentation of the affected communities as major shareholders of the emerging company articulate a more inclusive business strategy. Such articulation of agency establishes a ground for the communities to gain and exercise power to and power over in radically changed ways. It highlights the interest in rectifying the historical injustice and exploit an advantage in the renewed competition over control of the companies. At the same time, however, the desire of local business elites to dominate the privatization process and concentrate power through a hostile takeover strategy seems highly probable. The reported lawlessness, contestation over the issuing of land certificates for the sugarcane plantations, and the business strategy of the local actors are evidences of the smear collaboration of local business and political elites in playing for power over the reform process. However, a just and sustainable development of the sugar industry in Ethiopia requires revisiting and reforming the development model of the sector, recognizing its negative impact on the power and agency of the affected actors, and finding ways to balance the competing interests and reduce harm.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Zewde, “Environment and Capital.”

2 Scott, Seeing Like a State.

3 Pankhurst and Johnson, “The Great Drought and Famine of 1888-92.”

4 Lavers, “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia.”

5 Markakis, Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers.

6 Ibid.

7 Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Rransformations.”

8 Birhanu Fikade, “Local Company Eyes Wonji, Metehara.” The Reporter, May 18, 2019. https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/7998/.

9 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector; and Fikade, “Local Company.”

10 Birhanu Fikade, “ወንጂና መተሐራ ስኳር ፋብሪካዎችን ለመግዛት የተነሳው ኩባንያ መንግሥት የእኩል ተወዳዳሪነት ዕድል እንዲሰጠው ጠየቀ.” The Reporter, July 7, 2019. https://www.ethiopianreporter.com/64923/.

11 Kabeer, “Resources, Agency, Achievements.”

12 Zewde, “Environment and Capital.”

13 Ibid.

14 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

15 Girma and Seleshi, “Irrigation pPactices in Ethiopia.”

16 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

17 Ibid.

18 Zewde, “Environment and Capital.”

19 Rahmato, Customs in Conflict.

20 Wendimu et al., “Sugarcane Outgrowers in Ethiopia.”

21 Kassa, “Resource Conflicts Among the Afar of North-East Ethiopia.”

22 Zewde, “Environment and Capital.”

23 Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, PASDEP, 153.

24 Kumar, “India’s Development Cooperation with Ethiopia in Sugar Production.”

25 Ibid.

26 Wendimu et al., “Sugarcane Outgrowers in Ethiopia.”

27 Kumar, “India’s Development Cooperation with Ethiopia in Sugar Production.”

28 Ministry of Finance, Investment Opportunities in Ethiopian Sugar Industry.

29 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

30 FDRE House of People’s Representatives, Proclamation no. 504/2006.

31 Ethiopian Sugar Development Agency, New and Expansion Project Plan.

32 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

33 Council of Ministeres, Regulation no. 192/2010.

34 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry Sub-sector GTP 2 Period Fiscal Plan.

35 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Development Plan (2010/2011 to 2014/2015).

36 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

37 Kamski, “The Kuraz Sugar Development Project (KSDP) in Ethiopia.”

38 Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise, Omo Kuraz Sugar Development Project.

39 Ministry of Finance, Investment Opportunities in Ethiopian Sugar Industry.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Fantini et al., “Big Projects, Strong States?”

43 Ministry of Finance, Investment Opportunities in Ethiopian Sugar Industry.

44 Ibid.

45 Mohammed, “Ethiopia’s Second Five-Year Development Plan.”

46 Berhe, “A Delicate Balance.”

47 Dejene and Cochrane, “Ethiopia’s Developmental State.”

48 Daniel, “Transfer of Land Rights in Ethiopia.”

49 Ministry of Water Resources, Integrated Development of Abay River Basin Master Plan.

50 Asebe, Hizekiel and Korf, “‘Civilizing’ the Pastoral Frontier”; and Lavers, “Patterns of agrarian transformation in Ethiopia.”

51 US Department of Agriculture, Ethiopia Buy Sugar.

52 Thelle et al., “Assessment of the EU Trade Regimes Towards Developing Countries.”

53 Jolly, “Sugar Reforms, Ethanol Demand and Market.”

54 Ibid., 199.

55 Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, GTP I.

56 Cochrane and Bekele, “Contextualizing Narratives of Economic Growth.”

57 Gebreegziabher et al., “Profitability of Bioethanol Production.”

58 Heckett and Aklilu, “Agrofuel Development in Ethiopia.”

59 Science and Technology Minister, Sugar Technology Roadmap.

60 Lavers, “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia.”

61 Dametie et al., Proceeding of Ethiopian sugar industry.

62 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry Sub-sector GTP 2 Period Fiscal Plan.

63 Rahmato, Customs in Conflict.

64 El Mamoun et al., Structural Changes in Sugar Market; and Wendimu et al., “Sugarcane Outgrowers in Ethiopia.”

65 Scott, Seeing Like a State.

66 Lavers, “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia”; and Markakis, Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers.

67 Asebe and Korf, “Post-imperial Statecraft”; and Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations.”

68 Pankhurst and Johnson, “The Great Drought and Famine of 1888-92.”

69 Gebresenbet and Kamski, “The Paradox of the Ethiopian Developmental State.”

70 Fratkin, “Ethiopia's Pastoralist Policies.”

71 Gabbert et al., Lands of the Future.

72 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia

73 Gabbert et al., Lands of the Future.

74 Rahmato, Customs in Conflict; and Kassa, “Resource Conflicts Among the Afar of North-East Ethiopia.”

75 Wendimu et al., “Sugarcane Outgrowers in Ethiopia.”

76 Muluken Yewondwossen, “Upstart, Local Sugar Company in Privatization Push.” Capital, July 8, 2019. https://www.capitalethiopia.com/2019/07/08/upstart-local-sugar-company-in-privatization-push/.

77 Mikias Merhatsidk, “Amibara Rotates Crop Focus from Cotton to Cane.” Addis Fortune, April 6, 2014. https://addisfortune.net/articles/amibara-rotates-crop-focus-from-cotton-to-cane/.

78 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry in Ethiopia.

79 Weis, Vanguard Capitalism.

80 Zewde, “Environment and Capital.”

81 Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, GTP I.

82 Ministry of Industry, Ethiopian Industrial Development Strategic Plan.

83 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Sugar Industry Sub-sector GTP 2 Period Fiscal Plan.

84 US Department of Agriculture, Ethiopia Buy Sugar.

85 Cochrane and Bekele, “Contextualizing Narratives of Economic Growth.”

86 National Planning Commission, GTP II.

87 Ibid., 72.

88 Ibid., 140.

89 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector; and Fikade, “Local Company.”

90 Kamski, “Water, Sugar, and Growth.”

91 Ministry of Finance, Investment Opportunities in Ethiopian Sugar Industry.

92 Dawit Endeshaw, “Economic Reform Targets Five Key Areas.” The Reporter, June 15, 2019. https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/8139/.

93 Yewondwossen, “Upstart, Local Sugar Company in Privatization Push.”

94 FDRE House of People’s Representatives, Sugar Industry Administration Proclamation (draft).

95 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector; and Fikade, “Local Company.”

96 Yonas Abiye, “Law Makers Push Gov’t to Speed Up Privatization.” The Reporter, May 11, 2019. https://www.thereporterethiopia.com/7960/.

97 Ibid.

98 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector; and Fikade, “Local Company.”

99 Elshaday Tilahun, “Tendaho Stops Making Sugar.” Capital, December 16, 2019. https://www.capitalethiopia.com/2019/12/16/tendaho-stops-making-sugar/

100 Fasika Tadesse, “Ethiopian Sugar Plant Stops Work After Attack by Rebel Army.” Bloomberg, February 14, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-14/one-of-ethiopia-s-biggest-sugar-plants-stops-work-after-attack

101 Ethiopia Sugar Corporation, Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector.

102 Ibid., 21.

103 Fikade, “Local Company.”

104 Ibid.

105 Ibid.

106 Ibid.

107 Fikade, “ወንጂና መተሐራ ስኳር ፋብሪካዎችን.”

108 Makki and Geisler, “Development by Dispossession.”

109 Yidneckachew, “Policies and Practices of Consultation.”

110 Lavers, “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia.”

111 FDRE Constitution, article 43 and 44.

112 Lavers, “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia.”

113 Mosley and Watson, “Frontier transformations.”

114 Scott, Seeing Like a State.

Bibliography

- Asebe, R., and B. Korf. “Post-Imperial Statecraft: High Modernism and the Politics of Land Dispossession in Ethiopia’s Pastoral Frontier.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018): 613–631.

- Asebe, Regassa, Hizekiel Yetebarek, and Benedikt Korf. “‘Civilizing’ the Pastoral Frontier: Land Grabbing, Dispossession and Coercive Agrarian Development in Ethiopia.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46, no. 5 (2018): 935–955.

- Bergius, M., T. A. Benjaminsen, and M. Widgren. “Green Economy, Scandinavian Investments and Agricultural Modernization in Tanzania.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 45, no. 4 (2018): 825–852.

- Berhe, M. G. A Delicate Balance: Land Use, Minority Rights and Social Stability in the Horn of Africa. Addis Ababa: Institute for Peace and Security Studies, Addis Ababa University, 2014.

- Cochrane, L., and Y. Bekele. “Contextualizing Narratives of Economic Growth and Navigating Problematic Data: Economic Trends in Ethiopia (1999–2017).” Journal of Economies 6, no. 4 (2018): 1–16.

- Central Statistics Agency. Agricultural Sample Survey 2003/04-2017/18: Area and Production of Major Crops. Addis Ababa: CSA, 2004–2008.

- Central Statistics Agency. Large and Medium Scale Commercial Farms Sample Survey 2010/11 (2003 E.C.) to 2014/15(2007 E.C.). Addis Ababa: CSA, 2011.

- Dametie, A., T. Negi, and F. Yirefu. Proceeding of Ethiopian Sugar Industry Biennial Conference. Vol. 1, Addis Ababa, Birhan Ena Selam 2009.

- Daniel, B. G. Transfer of Land Rights in Ethiopia: Towards a Sustainable Policy Framework. The Hague: Eleven International Publishing, 2015.

- Dejene, M., and L. Cochrane. “Ethiopia's Developmental State: A Building Stability Framework Assessment.” Development Policy Review 37, no. 2 (2019): 161–178.

- Easterly, W. R. The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. New York: Basic Books, 2013.

- El Mamoun, A., A. R. Manitra, and K. Chang. Structural Changes in Sugar Market and Implications for Sugarcane Smallholders in Developing Countries, FAO Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper No. 37, 2013.

- Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. Sugar Development Plan (2010/2011 to 2014/2015). Addis Ababa: ESC, 2010.

- Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. Sugar Industry in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: ESC, 2019.

- Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. Sugar Industry Sub-Sector GTP 2 Period Fiscal Plan. Addis Ababa: ESC, 2016.

- Ethiopian Sugar Corporation. Roadmap to Implement Privatization of the Sugar Sector. Addis Ababa: ESC, 2020.

- Ethiopian Sugar Development Agency. New and Expansion Project Plan. Addis Ababa, 2008.

- Fantini, E., Muluneh, T., and Smit, H. “Big Projects, Strong States? Large Scale Investments in Irrigation and State Formation in the Beles Valley, Ethiopia.” In Water, Technology and the Nation-State, edited by Filippo Menga, and Erik Swyngedouw, 65–80. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Gabbert, E. C., F. Gebresenbet, J. G. Galaty, and Schlee, G. Lands of the Future: Anthropological Perspectives on Pastoralism, Land Deals and Tropes of Modernity in Eastern Africa. New York: 1st ed., Vol. 23, Berghahn Books, 2021.

- Gebreegziabher, Z., Mekonnen, A., Ferede, T., and Kohlin, G. “Profitability of Bioethanol Production: The Case of Ethiopia.” Ethiopian Journal of Economics 26, no. 1 (2017): 101–122.

- Gebresenbet, F., and B. Kamski. “The Paradox of the Ethiopian Developmental State: Bureaucrats and Politicians in the Sugar Industry.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 37, no. 4 (2019): 335–350.

- Girma, M. M. A., and B. Seleshi. Irrigation Practices in Ethiopia: Characteristics of Selected Irrigation Schemes. International Water Management Institute, Working Paper No. 124, Colombo, 2007.

- Heckett, T., and N. Aklilu. Agrofuel Development in Ethiopia: Rhetoric, Reality and Recommendations. Forum for Environment, Addis Ababa, 2008.

- Jolly, L. “Sugar Reforms, Ethanol Demand and Market Restructuring.” In Bioenergy for Sustainable Development and International Competitiveness: The Role of Sugar Cane in Africa, edited by F.X. Johnson, and V. Seebaluck, 183–211. New York, NY: Routledge, 2013.

- Kamski, B. The Kuraz Sugar Development Project. Omo-Turkana Basin Research Network, Briefing Note, 2016.

- Kamski, B. “Water, Sugar, and Growth: The Practical Effects of a ‘Failed’development Intervention in the Southwestern Lowlands of Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 13, no. 4 (2019): 621–641.

- Kumar, S. “India’s Development Cooperation with Ethiopia in Sugar Production: An Assessment.” International Studies 53, no. 1 (2017): 59–79.

- Kassa, G. “Resource Conflicts among the Afar of North-East Ethiopia.” In African Pastoralism: Conflict, Institutions and Government, edited by M.A.M. Salih, T. Dietz, and A.G.M. Ahmed, 145–167. OSSREA, 2001.

- Lavers, T. “Patterns of Agrarian Transformation in Ethiopia: State-Mediated Commercialisation and the ‘Land Grab’.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 3-4 (2012): 795–822.

- Makki, F., and C. Geisler. “Development by Dispossession: Land Grabbing as New Enclosures in Contemporary Ethiopia.” In International Conference on Global Land Grabbing. Sussex: Future Agricultures, 2011.

- Markakis, J. Ethiopia: The Last two Frontiers. Oxford, James Currey: Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 2011.

- Ministry of Industry. Ethiopian Industrial Development Strategic Plan (2013-2025). Addis Ababa: FDRE Ministry of Industry, 2013.

- Ministry of Finance. Investment Opportunities in Ethiopian Sugar Industry. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Finance, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia & Sugar Corporation, 2019.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. A Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to End Poverty (PASDEP) (2005/06-2009/10). Addis Ababa, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, 2006.

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. Growth and Transformation Plan One (GTP I) 2010/11-2014/15. Addis Ababa, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, 2010.

- Mohammed, Duri. “Ethiopia's Second Five-Year Development Plan 1963–1967.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 1, no. 4 (1963): 552–553.

- Mosley, J., and E. E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475.

- Ministry of Water Resources. Integrated Development of Abay River Basin Master Plan. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Water Resources, 1998.

- National Planning Commission. Growth and Transformation Plan Two (GTP II) of 2015/16 to 2019/20. Addis Ababa, National Planning Commission, 2015.

- Pankhurst, R., and D. H. Johnson. “The Great Drought and Famine of 1888-92 in Northeast Africa.” In The Ecology of Survival: Case Studies from Northeast African History, edited by D. H. Johnson, and D. M. Anderson, 47–72, 1988.

- Rahmato, D. Customs in Conflict: Land Tenure Issues Among Pastoralists in Ethiopia. New York: Routledge, Forum for Social Studies. Addis Ababa, 2007.

- Science and Technology Minister. Sugar Technology Roadmap. Addis Ababa, Science and Technology Minister, 2017.

- Scott, J. C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale Agrarian Studies, Yale University Press, 1998.

- Thelle, M. H., Jeppesen, T., Gjødesen-Lund, C., and Biesebroeck, J. V. Assessment of Economic Benefits Generated by the EU Trade Regimes Towards Developing Countries. Brussels: European Union, 2015.

- Water Works Design and Supervision Enterprise. Omo Kuraz Sugar Development Project Feasibility Study and Detail Design. Addis Ababa: FDRE Sugar Development Corporation, 2011.

- Wendimu, M. A., A. Henningsen, and P. Gibbon. “Sugarcane Outgrowers in Ethiopia: ‘Forced’ to Remain Poor?” World Development 83 (2016): 84–97.

- Weis, T. “Vanguard Capitalism: Party, State, and Market in the EPRDF's Ethiopia.” PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2016.

- Yidneckachew, A. Z. “Policies and Practices of Consultation with Pastoralist Communities in Ethiopia: The Case of Omo-Kuraz Sugar Development Project.” In The Intricate Road To Development: Government Development Strategies in the Pastoral Areas of the Horn of Africa, edited by Y. Aberra, and M. Abdulahi, 274–298. Addis Ababa: IPSS, 2015.

- Zewde, B. “Environment and Capital: Notes for a History of the Wonji-Shoa Sugar Estate (1951-1974).” In Society, State and History: Selected Essays, edited by B. Zewde, 120–146. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Press, 2008.