ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the financial collapse of and the subsequent interplay between material deterioration and maintenance on a flower farm in Naivasha that was placed under receivership in 2014. Our research is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted by the three authors before, during, and after the farm’s collapse. We examine how laid-off workers, current employees, owners, and new management engage in a process we call ‘suspending ruination’, in which the farm is neither left to collapse nor fully restored to its original state. Maintaining the farm’s infrastructure creates a state of suspension characterised by opaque messages of potential – a process reinforced by both the receivers’ intent to resell the property, as well as the former employees’ anticipation of receiving outstanding compensations. Examining how their practices of caring for what appears to be a ‘ruin’ uphold the farm as an ambiguous object of capitalist potential, our article complements ongoing research on ruinations, instigated by capitalism's future-making agendas.

Within the last 50 years, Naivasha has been transformed from a sleepy provincial locale into one of the leading centres of global cut flower production.Footnote1 Kenya supplies more than 35% of the flowers sold in the European UnionFootnote2, with around 70% of these coming from Naivasha.Footnote3 The livelihoods of many of Naivasha’s residents – low-wage farm workers (many of whom migrate to Naivasha from elsewhere in Kenya), middle class professionals, activists, and European expatriates alike – revolve around growing, caring for, harvesting, packing, and transporting cut flowers, which are sold in European supermarkets only a few days after harvest. In Naivasha, human actors, natural resources, materials, and machines are organised into an efficient and effective capitalist production system that, if everything goes as planned, creates enough profit for all actors involved.Footnote4

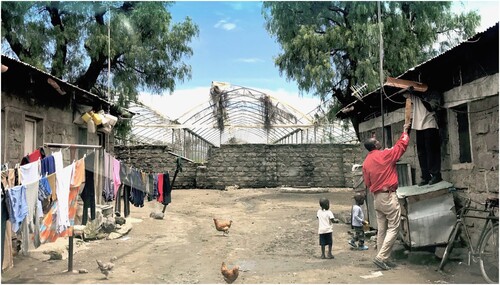

In practice, however, cut flower farming has transformed Naivasha into a ‘landscape of boom and bust, speculation and abandonment’.Footnote5 While some flower farms continue to thrive, the last decade has seen the collapse of many smaller start-up ventures and one of Naivasha’s three largest flower farms, Sher Karuturi, which was put under receivership in 2014 and remains in an ambiguous state. It no longer produces roses for export, but a small number of workers still tend the plants, safeguard farm equipment, and maintain critical infrastructure while the farm’s fate remains tied-up in the Kenyan courts. This article explores the collapse of this large farm from the point of view of those whose livelihoods still depend upon it – especially current and former employees who still occupy the farm’s housing complex. These actors engage in a process we call ‘suspending ruination.’ Their actions indefinitely delay the failure of this farm and preserve the possibility (or at least the outward appearance) that it may remain a viable venture. As they care for what appears to be a ‘ruin,’ they maintain its status as an object of potential capitalist profit-making and, simultaneously, as a potential future employer.

The remains of this once-successful farm stand in startling contrast to the many successful flower farms that line Naivasha’s South Lake Road. Sher Karuturi has been reduced to what locals call the ‘skeleton,’ the massive metal structure that used to keep the greenhouse plastic in place. In contrast to other farms where polythene plastic obstructs a direct view, nothing inhibits one from looking into this farm’s inner life: rows of overgrown rose bushes trimmed intermittently by a handful of workers employed by the receiver .

This ‘ruin’ inspires many questions. What led to this farm’s demise? Does its ruined state reflect the future of other Kenyan flower farms? Is this evidence of ‘the relentless, increasingly global, capitalist quest for profit maximisation, where less profitable nodes in production networks are apt to be dropped, as production moves to other parts of the world’Footnote6? Or was the farm’s collapse caused by the personal failure of its owners? What has happened to the thousands of workers who were once employed here? What has happened to the plans, hopes, visions, and dreams of the flower farm workers? Where did all the material objects used on this farm – polythene plastic, containers, and bicycles – end up?

Giving Morten Nielsen’s work on ‘anticipatory action’Footnote7 a capitalistic twist, our article analyses how the practices and imaginaries of flower farm workers, company owners, and receivers ‘connect otherwise detached temporal moments and potentially establish a meaningful relationship between the present and the future’Footnote8 fuelled with hope and expectations of future economic profit. Although the circulation of capital (manifest in the farm’s bankruptcy and subsequent receivership) has eroded the livelihoods of the majority of workers employed at the height of the farm’s success, many of these workers still inhabit the farm and are part of the network of actors whose affective and physical labour suspends the ruination of this farm, maintaining its status as an object around which ‘anticipatory actions’ of economic hope revolve. Understanding how these floral ruins ‘were created and how they are treated in the aftermath’ will ‘give us a clearer picture of the tensions that undergird local political economies than do the first impulses toward planning and construction’.Footnote9 We explore these tensions and the ways that these workers articulate their ‘right to the remainder’Footnote10 and build futures for themselves (and the farm itself) amidst the infrastructure, services, and social relationships still present in this ruin.

What may look like an abandoned ruin is actually a carefully maintained and deeply contested place. Capitalist hope, it seemed, had not yet run out of steam. However feral and left-to-waste these massive greenhouse structures appeared at first sight, entering the gates revealed not a simple story of collapse and decay, but a more complex story that includes processes of ordering and maintenance that effectively suspend it from falling completely into ruin. Since the company was put under receivership in February 2014, the owner has been entangled in multiple court cases involving unpaid suppliers, the workers’ union, and the Kenyan government, which accuses the owner of tax evasion.Footnote11 Despite this protracted legal battle, the farm has not been completely abandoned. Although operating with reduced personnel, its offices and several restaurants catering to employees and managers are still functioning. A small number of employees complete a number of daily tasks: some protect office equipment and chase away hippos and roaming wildlife encroaching on the farm; others ensure that the irrigation pipes are frequently used so that they do not burst; others weed the beds and make sure the rose bushes are not withering away. Their activities disrupt the process of ruination, creating the possibility that the farm could once again produce roses for global markets.

The plans and dreams of laid-off workers have also been put on hold – suspended for the time being, but not necessarily ruined. The majority of them never left Naivasha for good and still wait for outstanding payments, such as unpaid salaries, benefits, and other pension obligations. Some used these expected future pay-outs as collateral to get loans, and others still plan to use these assets to become ‘self-employed’ (e.g. by opening a small shop). They actively engage in activities that suspend the process of ruination in the hope that they will one day see these payments.

These ex-workers still inhabit the former company housing complex, located not far from the skeletal greenhouse frames. They have organised a neighbourhood security group and buy their daily goods at the ‘shopping centre’ along the road, which consists of a bustling row of shops, small restaurants, and stalls offering diverse services. By staying in Naivasha, these former workers have tied their own fates to that of the farm and those representing it. As Stephen, who worked as a carpenter and was the chief shop steward of the workers’ union, phrased it:

And I pray to God to let me live, to give me the way of living, until I see the farm is back and they will pay for years of service. Then I will leave them. It is just a rope which I am tying around my neck. Everybody is looking at me, everybody. Is the chief there? Ah, he is there, ok. But if the chief is not there, they know that they are doomed.Footnote12

This article is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in three distinct moments that allow us to examine the labour of capitalist ‘anticipatory action’ in this space across a dynamic timescape. Megan Styles interviewed farm workers and managers in 2007 and 2008, when the farm (originally known as Sher Agencies) had just been sold to Karuturi Global Limited, and again in 2014, shortly after Sher Karuturi was placed in receivership. Her work provides insight into the ways that local actors understood the consequences of these major changes in the farm’s status, each of which marked a moment when the farm’s position within the global circulation of capital and financial instruments shifted. Mario Schmidt conducted fieldwork in Naivasha in 2017 and 2019, and Anna Lisa Ramella in 2019, 2020, and 2023, after the majority of workers had been laid off and the future of the farm had hung in the balance for several years.Footnote18 This more recent ethnographic material helps us understand how different actors suspend the process of ruination and attempt to profit from the farm’s ambiguous potentials. Just as this article neared publication, Anna Lisa Ramella returned to Naivasha in 2023, only to find that an increase in the lake’s water level had once again completely changed the farm’s chances of being sold. Around a third of the land was now submerged, and the hopes of workers still waiting for payments had shrunk to a minimum. However, they stayed in Naivasha and continued to fight for their right to remain on the company’s former premises.

The next section reconstructs the history of the farm from its hopeful beginnings in the 1990s to its collapse. We then offer examples of some of the ambiguous understandings of the farm’s past and future that are enabled by the practices of ‘suspending ruination.’ Our article complements ongoing research on the ruination set in motion by capitalism’s ambiguous and non-transparent agendas of future-making. We conclude with observations about ruination’s ambivalent nature and emphasise that ruins are ‘dialectical images that lay bare the historical contradictions of social life’.Footnote19

The end or a new beginning? The history of a promise

The collapse of this particular farm was a shock to employees and the wider Kenyan public. The farm was a significant producer of roses for international markets and a major employer generally regarded as successful. Before its acquisition by Karuturi Global Limited in 2007, the Dutch owners, Peter and Gerrit Barhoorn, who founded the farm as Sher Agencies in 1997, established a reputation for the farm as ‘progressive’ in regards to labour and living conditions. In response to industry-wide pressures to improve labour conditions in Kenyan floriculture, the owners hired a politically prominent Maasai lawyer, Martin Ole Kamwaro, to serve as the Human Resources manager in 2002 and recruited welfare officers from among the non-profit and union officials most critical of the farm. Based on interviews conducted by Megan Styles in 2008, the farm allowed workers to unionise and turned additional middle management positions over to black Kenyans in an explicit effort to ‘Africanise’ its operations. It also adopted policies on gender equity and sexual harassment. In 2006, an article in the LA Times praised the ‘workplace revolution’ underway at Sher, which ‘has tried to transform itself from one of the industry’s most reviled employers to one of its most progressive’.Footnote20

In 2007 and 2008, when Megan conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Naivasha, there was a sense among workers that labour and living conditions had drastically improved and would continue to do so, as long as welfare officers and union officials continued to ‘press’ farm management. In other words, this particular farm had become a space where Kenyan professionals felt uniquely empowered (relative to Naivasha’s other farms) to play a role in the continuous process of improving labour and living conditions in this high-profile Kenyan industry. There was a shared perception that the workers, the welfare officers, the union and the company were now working together. This created a shared sense of forward momentum and hopes for further development and a bright future. When the farm changed hands in 2007, farm employees worried that the new owners, in the words of one farm managerFootnote21 ‘would not have the same heart for the workers,’ but they did not seem to fear that the farm would collapse commercially. After all, how could something so successful fall into ruin?

Unfortunately, the process of ‘ruination’ reportedly began not long after Karuturi acquired the farm. In 2010, the farm owners borrowed 227 million Kenyan shillings (equivalent to more than $2 million) from CFC Stanbic Bank, and in 2013, they borrowed another $3.8 million from CFC Stanbic and ICICI Bank, India.Footnote22 It is unclear how Karuturi planned to use these funds to add value to the farm, and from the perspective of workers, this capital vanished quickly. There was no sign that these funds were invested in farm operations, and workers went on strike in 2012 and 2013 over declining labour conditions and outstanding pay and benefits, demanding that the government intervene on their behalf. To add to the farm’s woes, the Kenyan government ruled in 2013 that the farm owners were guilty of tax evasion, and Karuturi agreed to pay a $4 million settlement to the Kenya Revenue Authority.Footnote23 Karuturi made a single payment on the second loan in January 2013 and then defaulted on the remaining debt. In February 2014, the farm was placed in receivership, and since then, the farm has been caught in a chain of legal processes that prevent its total failure as a flower farm but fall short of delivering on its resurrection. This series of as-yet unresolved legal cases prevent the farm from either being liquidated or restored. The ambiguity surrounding the farm’s future creates a complex atmosphere of hope and desperation among those whose fates are tied to the outcome of these legal challenges.

When Megan returned to Kenya in July 2014, she interviewed farm managers and general labourers about their perceptions of this precarious and liminal situation.Footnote24 The farm was already in receivership, and most workers had not been paid for six months. Despite these challenges, many continued working. Some hoped that the receivers would be able to restore the farm and others were concerned that, if they separated from the farm, they would be less likely to receive the outstanding pay and benefits they were owed.

In 2014, local explanations for Karuturi’s financial woes varied, but most involved several common elements. The investors who purchased the farm, it was said, were ‘cheated’ in the deal. One manager explained,Footnote25 ‘The farm was over-priced to begin with. They sold them even what they did not own. They found out they were conned. They bought thin air.’ Some alleged that the farm titles, for instance, included greenhouses and structures illegally constructed below the riparian reserve line; land beneath this line is technically owned by the Kenyan government. Others argued that the former owners took their market relationships with them when they departed Naivasha. ‘The former owners set up a new farm in Ethiopia and flooded their usual markets with their own flowers,’ explained the owner of a successful neighbouring farm.Footnote26 ‘Karuturi had a massive operation that produced loads of flowers but they had nowhere to sell them.’ Karuturi reportedly tried to establish new markets in Dubai and other geographic areas, but this strategy faltered. Others alleged that the farm’s parent company, Karuturi Global Limited, expanded its agricultural operations in India, Kenya, and Ethiopia simultaneously, stretching its operational capacities too thin.

All of the farm managers and employees Megan interviewed also claimed that the Naivasha operation was woefully mismanaged. Top managers were allegedly replaced with less knowledgeable executives who drew large salaries. One former production manager explainedFootnote27, ‘They came with a large staff from India, and they were very inexperienced. They complained that we were wasting inputs. They tried to cut costs by switching to less expensive fertilisers and reducing fertigation rates, and production dropped. How can a flower grow when they are not feeding it? This is a huge farm, and at one point, you could ferry the flowers to the airport in a pick-up truck, they were so few.’ He sighed and continued, ‘Any returns they got were not re-invested. They spent the money on managers’ salaries and lined their own pockets.’

As the farm’s finances began to falter, the farm directors reportedly stopped enforcing policies designed to protect workers and the environment. Stanley, a former shop steward, describesFootnote28 what he saw as a gradual process of degeneration in employment conditions, ‘When the new owners first came, salaries were paid on time. PPEs [personal protective equipment] were worn and issued as required. Housing was adequate.’ This status quo did not last long. He explains, ‘With Sher, they followed proper procedures and channels for dismissal, but many people were sacked by Karuturi without that definite process. With Sher, there was a known pay scale. Now there are no definite pay scales; people get paid differently for the same job. That employment legibility was lost.’

Some important benefits supplied by Sher were also cut. Stanley explained, ‘You had an orientation at the start of employment. This was cancelled, and there were more accidents and work-related injuries. Sher also paid the salaries for the teachers in the school, and workers paid no school fees. Now the parents pay the fees and directly employ the teachers, and the teaching has become inadequate.’ When workers brought their concerns about these cuts to the new farm director, he reportedly refused to reinstate these programmes. According to Stanley, ‘He said, ‘I’m not an NGO.’ And, from there, it graduated from bad to worse.’ By February 2014, workers had not been paid for several months, the electricity in the housing complex had been shut off, and most of the on-farm hospital and medical services had been cut.

Stanley hung his head, thinking of how the company had changed over time, ‘Nobody thought of this happening. Sher set high standards. We never thought it would reach this state. When I came to the company in 2001, we were pushing, pushing, pushing. [The now departed Human Resources manager, Martin Ole Kamwaro] really empowered the workers. There were even pamphlets printed for the employees to know their rights. There were so many trainings for shop stewards on human rights and gender issues. They could argue with the management, and they were not people to joke with.’ He reflects on the changes in management approach and style. ‘Karuturi came with a new mentality. “I’m here to make a profit; this is a business.”’ In 2014, Stanley was still hopeful for the farm’s future. ‘It can revive. We really didn’t know it could get this bad. It can revive, but it will take a long time.’

Joseph, a senior managerFootnote29, described the uncertainty that gripped farm managers and workers alike in July 2014, ‘We have so many questions about what will happen after the receivership. If it goes back to Karuturi, then 90% will resign.’ In addition to the lost months of salary payments, long-term workers stood to lose accumulated retirement benefits. According to several managers, Sher provided long-term employees with a ‘continuity letter’ indicating that their benefits accounts would be transferred to the new company. ‘Those who resigned up to May 2013 were paid their final benefits. Those who remain are losing hope that they will receive these. Even if they could get another job, some are staying on because they are hoping not to lose these benefits,’ he explained. ‘Karuturi also went with the SACCO [Savings and Credit Cooperative Organization]. They continued deducting money for loan repayments from the paycheck, but they never remitted these back to the shareholders. We’re waiting to see what will happen with this as well.’ Joseph and his fellow employees and managers had extremely high expectations of receivership. At least initially, they viewed the receivers as potential saviours who could restore the farm to order and save both their jobs and (potentially) the valuable benefits and services that the successful farm once provided (e.g. the hospital and the primary and secondary schools).

In May 2016, the receivers notified the farm’s workers that they planned to cease operations as a result of a ‘winding up order’ issued by the Kenyan courts. After more than two years of patience amidst extreme uncertainty, all employees were relieved of their jobs and asked to vacate their on-farm housing units. However, as will be discussed in the following sections, many stayed on-site and were not yet ready to disconnect their own futures from the fate of the farm, continuing to struggle to make a living among the ruins of the farm and the worker housing complex.

Since 2016, Karuturi and the receivers have been in an ongoing court battle regarding the ‘winding up order.’ For our argument, it is of special importance that, in the course of this legal fight, the former owners allege that the receivers have ‘ruined’ the farm intentionally so that they can sell it quickly.Footnote30 Throughout this period, allegiances between workers, Karuturi, and the receivers have shifted several times. Based on Megan’s fieldwork in 2014, the workers initially supported receivership, hoping that this might restore the farm’s status as a successful export flower producer. By 2019, their sentiments toward the receivers had changed. They feared that the money from the sale of the farm and its assets would be used to recoup investments made by the receivers, rather than covering the costs of their own outstanding pay and benefits. As workers’ representative and former shop steward Samson Auda explained to a journalist:

In Feb 2014 Stanbic [Bank] misled us into filing an affidavit in court to support receivership, by promising to protect our jobs and benefits accrued. Today they’ve turned back, denied us employment since March 2016, claiming that under receivership, the benefits stand annulled and to add salt to the wounds, seeking to evict us from the company's accommodation. This in addition to shutting down the 100-bed company run hospital and denying all support to the company owned schools. . . We are taking over the farm and will continue tilling the land to recover our lost livelihood and benefits.Footnote31

The ‘ruin’ one now sees when passing along Naivasha’s South Lake Road remains a contested place, to which different actors lay different claims. Some continue to brand it as valuable and potentially functional as a flower farm; others describe it as destroyed and valueless. The next section will show how the approximately 40 workers still employed by the receivers in 2020, continued to uphold the structures and keep the farm in a state of ‘readiness’ for a potential sale. Former workers remaining in Naivasha in 2020 still expected to be paid out by Karuturi and engaged in practices that sustained their living on and around the farm’s premises. Their occupation of the farm’s housing block was strategic in that it prevented the houses from falling into ruin. The workers themselves were actively engaging with the material remnants of their past economic and personal visions of success, and through the upkeep and maintenance of these remnants, they stabilised and upheld their hopes for personal success.Footnote32 Actors living around the farm tied their future to one another and also to the materiality of the place itself.

Suspending ruination and navigating ambiguous potentials

As we have described earlier, the collapse of this farm has followed a complex path, with powerful actors (the bank and the former owner) pursuing different capitalist strategies. The former owner wants to keep the farm to eventually re-open it or sell it for a good price when and if he sees this as appropriate. The receiving bank aims to sell the farm as quickly as possible to recoup the investment. Former and current farm workers, who initially prioritised keeping their jobs, are now mainly hoping to receive their outstanding payments. In the context of this uncertainty, many workers now blame the receiver (rather than Karuturi) for failing to keep the farm operational. One worker told Anna in 2020 that the receiver did not keep accurate accounts of farm revenues and never subtracted the value of the cut flowers sold from the loan amounts owed by Karuturi. Rumours also held that stored technical assets were being sold illegally; again, driving down the selling price of the farm while generating revenues for the receivers. These allegations reflect on-going conflicts between the former owner and bank.

While caught in the midst of these duelling strategies, as of 2020, current staff members and former workers are both engaged in maintaining the ruin, but for different reasons. While the paid staff members are tasked with preserving the farm’s status as an export flower venture, former workers maintain the farm because it is their home and because it still remains central to their livelihoods. They maintain the worker housing units (), by actively inhabiting them and cultivating the land around them, growing greens and other vegetables for subsistence. This unwitting maintenance work supports the former owner’s intention to reopen the farm without much renovation work, while for the workers it is mainly a way to facilitate their stay in Naivasha.

The following two sections examine how these current and former employees maintain the farm – thus suspending ruination – and how their practices and agendas are interlinked.

Suspending collapse: how employees maintain the ruin

What remains of the farm is in 2020 cared for by a small set of paid employees. A few managers work in the old offices near the main gate, keeping track of equipment stored on the farm and supervising the workers still employed to maintain the ruin. Maintenance workers rid the flower beds of weeds and prevent wild animals from roaming on the property. One worker told AnnaFootnote33, that when he arrived in Naivasha in 2018, ‘the place was really bushy.’ His job is to roam the former greenhouses together with his co-workers and rid them of weeds with a panga (machete). While the roses are kept in place, all other plants that litter the rose beds are cut down. Other maintenance workers operate the water pumps at the lakeshore. Their job is to irrigate the flowers, mostly to avoid blockages in the pipes. When they encounter any leftover polythene sheets on the greenhouse skeletons, they take them down and put them in storage, where they are kept for potential future use. They are also in charge of cleaning the greenhouse structures. Security staff guard the main gates and patrol the farm each day to safeguard farm equipment, including pumps, greenhouse materials, office supplies, and computers.

As they maintain the farm in this way, these employees contribute to the farm’s ambiguous state. They act on specific instructions to maintain some things – the rose bushes, the greenhouse structures, the irrigation pumps – while other things are allowed to go to waste in order to save costs. As one of the workers explained to AnnaFootnote34, their job is to ensure that the farm appears to outsiders – potential buyers, surveyors and the receivers themselves – as if it could be ‘lifted’ (reopened) anytime. Any potential barriers to selling the farm are kept to a minimum; the ruin is maintained so that it can be leveraged for profit. By suspending ruination, they present the farm as a valuable investment opportunity, a venture fit to be re-opened that is clearly in need of renewal (but is not yet ruined).

Edensor describes ruins as a result of material ‘disordering of a previously regulated space’.Footnote35 However, our example shows that ruination and maintenance are processes that go hand-in-hand. While we agree with Edensor that ‘order is maintained through constructing networks which variously comprise objects, humans, spaces, technologies and forms of knowledge,’ which ‘are folded into regulatory systems and strategies’Footnote36, this flower farm reveals that disorder can be a crucial component of maintenance, and vice versa. In our case, this ambiguous arrangement between collapse and maintenance underscores the ways that actors with different economic agendas clash with one another, using available regulatory systems and strategies to keep this space in a dynamic of ‘suspended ruination.’ The farm’s potentials – as an export floriculture venture, a residential housing development, or something else entirely – are left ambiguous to attract as many forms of investment, speculation, and labour as possible.

As the next section shows, many of the farms’ current and former employees ‘don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin’.Footnote37 While the farm remains ‘suspended,’ they find ways to make a living from the land, infrastructure, and other materials collected within the ruin, thereby ‘mixing progressive aspirations with nostalgia for past hopes and aspirations’.Footnote38 While stuck in Naivasha, these workers engage in work practices that feed into what Ghassan HageFootnote39 might call their ‘existential mobility’Footnote40 – the ‘sense that one is “going somewhere”’.Footnote41 Their form of ‘stuckedness’Footnote42 is bridged by the expectation that by ‘waiting out the crisis’Footnote43, it will eventually pass and the farm will either reopen or meet the demands of the laid off workers.

Living with collapse: how former workers use the ruin’s potentials

When Anna Lisa and Mario visited Naivasha in between 2017 and 2023, many of Karuturi’s former employees were still living among the ruins. While some had departed over the years, giving up their hopes of ever receiving their outstanding payments, others remained in Naivasha expecting to eventually be compensated. Having lost their jobs, the workers’ plans for the future were suspended. They were not interested in migrating back to their rural homes, which they saw as offering even less productive potential futures. They continued to tie their fates to Naivasha and to this particular farm and its infrastructures. This section investigates the ways that they make a living in and through the farm’s potential .

By becoming ‘squatters’ in their former houses, these workers attempt to assert their ongoing claims to their rights and pensions. Actors with different visions of the farm’s future understood their continued occupation of the housing complex in conflicting ways. As a union representative told Anna,Footnote44 the former owner of the farm, Karuturi, is in favour of the former workers residing in the houses, because they prevent the housing structures from deteriorating; some have even renovated their houses. This will benefit the owner by lowering renovation costs when the farm is re-opened. The receivers, on the other hand, are said to be against the rights of these squatters because potential buyers may be discouraged by the fact that the workers still live there and are claiming outstanding payments. The workers themselves, encouraged by the union, see their occupation of the houses as a material marker of their waiting for outstanding claims and a proclamation of their rights .

Figure 4. Small gardens cultivated on land formerly reserved for rose cultivation after workers moved the fenceline (© Anna Lisa Ramella).

These former workers do all they can to use this land to sustain themselves in the present. They plant small gardens on the farm, expanding the boundaries of the housing complex into the area designated for rose cultivation. Unlicensed fishermen roam the lakeside next to the greenhouses, using the inside of the skeletons as a hiding spot for their gear. They use the dykes built to protect the farm from flooding as access points to enter the water for net fishing. Because it required low investment in terms of equipment, fishing has become one of the main livelihood practices adopted by former farm workers. Fishermen enter the lake in groups of up to five and swim and drag the net across the water to trap fish. This practice is mostly done by migrants from the Lake Victoria area, as the groups are often organised according to the region of origin.Footnote45 After a few rounds of fishing, they usually make a small fire to cook a lunch consisting of freshly caught fish and ugali (stiff grain porridge), which they prepare with lake water. Others access the lakeside via the abandoned villa of the farm’s former General Manager to fish with rods and wash clothes and equipment. Aside from fishing, they also make a living by selling vegetables or fish to workers from other flower farms. These ‘lateral work arrangements’Footnote46 allow them to survive while they wait for their employment in flower production to be renewed, or for their long overdue pay-outs .

Figure 6. Accessing the lake for fishing through the ruin of a former general manager’s house (© Anna Lisa Ramella).

Figure 7. Market woman preparing potatoes and fish for sale (film still © Anna Lisa Ramella and Ben Bernhard).

In many of the above mentioned lateral livelihood practices, remnant materials from the farm are used for various purposes: flower buckets serve as containers for fish; polythene sheets from the former greenhouses are used to wrap fish and to cover vegetables and market booths; Dutch bicycles and worker uniforms make their way into second-hand markets. Thus, laid-off workers make their living in the present by repurposing the left-over material infrastructure of their former workplace. As they fish and sell their goods in and around the farm, they contribute to the process of suspending ruination, developing a new system for deriving a living from the farm.

In these ways, former workers’ livelihoods depend on the simultaneously ruined and ordered system of the former flower farm. The materials they use and the ways that they sustain themselves ‘[blur] distinctions between […] ruin and renewal’.Footnote47 They are allowed to stay in the residential housing units to keep them from falling to ruin, but they are not passive agents scraping by in the shadow of the skeletal greenhouses. They actively re-appropriate the space by hiding fishing equipment, cultivating vegetables, and creatively reusing farm materials .

Figure 8. Re-using materials from the farm: flower buckets and polythene sheets used to collect and sell fish (© Anna Lisa Ramella).

Figure 9. Re-using materials from the farm: bicycles used to get to other work sites (© Anna Lisa Ramella and Ben Bernhard).

Figure 10. Former worker watering kale on the Sukuma Wiki Farm cultivated by former Sher Karuturi staff (© Anna Lisa Ramella).

Their activities within these ruins trouble dichotomous notions of modes of waiting, such as (1) Pardy’s juxtaposition of ‘chronic’ versus ‘acute waiting’Footnote48, or (2) Robins’ contrasting concepts of ‘cyclic’ versus ‘biding time’Footnote49: Former flower farm workers in Naivasha are immersed in a prolonged period of waiting, while moments of hope inspired by developments in the court case, catapult them into moments of intense anticipation (1). They are thus positioned within a cyclic temporality, relentlessly providing to sustain their daily needs, while always waiting for a specific opportunity to act (2). Furthermore, while being out of control with regard to the purpose and result of what they are waiting for, they are still able to engage in activities that sustain their livelihoods. Gasparini, situates waiting ‘at the crossroads not only of the present and future, but also of certainty and uncertainty’.Footnote50 In the case of Karuturi’s former workers, uncertainty with regard to the outstanding payments (and their eventual, but not certain payout) is contrasted with the active, daily work on and around the ruin to sustain themselves working towards, but maybe never reaching, their security of supply.

While they wait for their outstanding wages and benefits to be paid, they also assert the legal right to continue using and deriving a livelihood from this land. There is for example a patch of land between South Lake Road and the company’s primary school, which the company gave to workers as a garden space after migrant workers from Western Kenya complained that they had no possibility to perform small-scale agriculture. Workers continue to use this land for the cultivation of vegetables. They object to the sale of this land, and claim a right to this space, regardless of the farm’s fate. The water supply in the worker housing units also depends on the receivers’ payment of utility bills. Since these bills have gone unpaid, cultivators who used to fill their water buckets in the neighbouring school now have to walk all the way to the lakeshore. In arguing for the right to this space and for water to irrigate the garden, they articulate what Bize calls a ‘right to the remainder’.Footnote51

They also assert a continued right to the social services and amenities that Sher Karuturi once provided its workers – the hospital, school, social club, and company football team. Many of these critical services continue to be put on hold. As was the case already during Megan’s fieldwork in 2014, the company hospital has not been functioning for years, and the attached school, ‘Sher Academy,’ struggles to pay the teachers. While some of the teachers are now sponsored by other flower companies, others still depend on the fee payments made by parents. In response, and as a way to provide food to both the students and their own families, some teachers have started growing vegetables in the school yard. As one teacher showed AnnaFootnote52, these vegetables are taken home by the teachers to make up for the missing salaries. However, even their gardening endeavours depend on the water supply from the former company’s pumps, subject to the payment of utility bills. Even though workers engage in practices of re-appropriation of the farmland and of claiming their rights to it, many of these practices remain dependent on the (financial) services of the receiving bank.

Both, the right to remain in the housing complex and adjacent services, as well as the dependencies connected to it are passed on to the younger generation. In March 2019, a group of farm workers’ children whose parents have long left Naivasha told Anna that they stay in Naivasha because it’s the place they know best, and they are saving on rent since they ‘inherited’ from their parents the right to live in the old company housing complex. For them, the collapse of the farm means fewer possibilities for work, and some of them earn a living by operating a small pool salon amidst the workers’ settlements or driving a boda-boda (motorcycle taxi). One of their meeting spots is the Social Club, which is now in a deteriorated state. Reduced to four walls and a few benches, some former workers still organise football screenings here on a communal TV – again subject to the availability of electricity. There was also a football field, and Sher Karuturi sponsored a very successful football team. The field is still in use but it is now maintained by ‘Crayfish Camp,’ an adjacent tourist accommodation and restaurant. The youth of the town, often children of former farm workers stranded in Naivasha with few alternatives, have inherited not only the right to remain, but also the need to engage in activities that suspend ruination and preserve the possibility of the farm’s renewal.

Their occupancy and use of these spaces suspends the process of ruination for the farm, but in a sense, their own futures are also suspended – they prevent houses from deteriorating, pipes from clogging, and land from becoming overgrown, but they also lack the opportunity and incentive to move elsewhere. As long as they remain here, asserting their claims to outstanding pay and benefits, employment opportunities, and squatter’s rights, they may actually deter investors from buying the farm. They remain suspended in the uncertain space between ruin and renewal.

Dawdy writes that ‘new ruins’ deriving from modern capitalist projects, such as what remains of Sher Karuturi, show how ‘ruins represent the impermanence and bluster of capitalist culture as well as its destructive tendencies’.Footnote53 Dawdy also points out that processes of ruination suspended over a long time ‘reveal the contradiction of progress’Footnote54, wherein maintenance becomes a symbol of moving forward, upholding the image of a functioning capitalism. As described above, these actors – whose livelihoods have long depended on this farm – participate in the process of suspending ruination, alternating between hope and despair as they wait for payment (and/or the resumption of their employment).

Conclusion

Practices of maintenance and repair suspend the process of the farm’s ruination and enable ‘anticipatory actions’ of capitalist profit-making; the presence of these actors prohibits both a complete collapse and a successful reopening. On the one hand, complete abandonment of the farm by the receivers would end the workers’ hopes of being cashed out and prevent them from planning a better future. On the other hand, by staying in the company housing and performing their own material practices, workers delay the selling of the farm, as their claims pose a threat to any future buyer. At the same time, as current workers and security staff maintain the farm by guarding its assets, keeping its machines running and weeding the flower beds, the farm remains an object of hope and possibility. These forms of suspending collapse, as we have shown, are embedded in both material processes and the stalled visions of the people living in and around the farm. The process of suspending the material collapse of the farm binds together former and current workers, the receivers and the owner, as well as their different visions, hopes and expectations, which remain ‘active, in the resilient presence of built matter, which unpredictably releases its enchantment or its toxicity.’.Footnote55

In this case, it is thus not the completion of an infrastructural project that is suspended. Rather, what we observe is the suspension of the ruination of both the farm’s material infrastructure, as well as the suspension of the collapse of these actors’ visions of their successful futures. Still expecting their outstanding pay and benefits, they remain here and carve out new forms of livelihood in and around the Karuturi flower farm. By focusing on the current employees’ maintenance of the farm and the former employees’ ways of making ends meet by engaging with the materiality of the farm, our article emphasises the productive moments of suspension. While generally viewed as a decision after which an infrastructural project’s completion just comes to a halt, we understand suspension as a cluster of continuously employed and productive practices. We follow Akhil Gupta’s assertion that suspension, ‘instead of being a temporary phase between the start of a project and its (successful) conclusion, needs to be theorised as its own condition of being. The temporality of suspension is not between past and future, between beginning and end, but constitutes its own ontic condition just as surely as does completion’.Footnote56 Suspension, in other words, does not only block, but also opens up the potential for the emergence of other productive practices. Practices of suspension do not only alter or change ‘worlds but hold them in such a way as to allow them to settle into different arrangements, possibilities’.Footnote57

Yet, the suspension of the farm’s collapse extends beyond the farm, causing a chain of dependencies and triggering the emergence of self-help practices performed by the workers, their children and teachers alike. These ‘lateral work arrangements’Footnote58 are not only closely connected to the site of Naivasha, but also to the fragilities imposed by the cut flower industry, which brought migrant workers to Naivasha in the first place. Because of these ‘lateral work arrangements’ and the myriad ways in which former and current workers inhabit, maintain, and alter the ruin, the settlements along the further end of South Lake Road are bustling places full of life and activities. The ambitions of former Sher Karuturi workers, as well as their grown-up children who stayed in Naivasha, are tied to the fate of the farm. The state of suspension is maintained as long as the legal case between the owners and the bank remains unsettled. These practices are political in the sense that they prevent us from viewing the space as a blank canvas onto which new capitalist imaginaries, expectations, and hopes can be projected.

Investigating the ‘suspended ruin’ of Sher Karuturi ethnographically also helps to counter the risk of what Dawdy describes as the writing off of ‘ruins and abandoned land […] even if occupied and used’.Footnote59 The ‘lateral work arrangements’ – such as fishing on the dykes that protect the farms or selling vegetables on the market to flower farm workers – are thus more than mere pastimes and side-hustles. They are part and parcel of the future-making taking place in Naivasha and around the collapsed flower farm of Sher Karuturi. In a way, these actors’ own imagined ways of ‘ordering’ the future - their life plans and visions - counteract the apparent ‘ruination’ they are exposed to at the same time. Workers’ attempts to make ends meet are entangled with the vision of the former owner to let the farm become profitable again.

Projects like this particular flower farm intertwine large-scale capitalist speculation with the small-scale future plans of workers, tying together capitalists’ and workers’ future-making projects and thereby intertwining their fates. Creating a unique capitalist timescapeFootnote60, this specific form of a ‘suspended ruin’ is neither characterised by the fast timescapes of the stock exchange market, nor by a carefully crafted plan for the near future. Instead, former and current workers, the farm’s former owners, and the new receiving managers are united through a lack of knowledge and certainty with regard to the farm’s future. Nielsen and Pedersen consider this lack of certainty as constitutional for the ability of humans ‘to extract the free-floating images of affects that the world continuously self-emits’.Footnote61 Precisely because nobody knows what really happened, what is currently happening, and what finally will happen to the farm, actors can tap into the affectual capacities of the ruin itself through engaging in sometimes contradictory ‘anticipatory actions.’ Actors view its current state of collapse either as the cruel ending of a story of capitalist investment, or as the hopeful start of a successful collaboration. Offering ambiguous potentials, the farm becomes both an index of collapse and a blossoming future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the workers and managers living among these ‘ruins’ who agreed to speak with us; the University of Illinois Springfield for providing summer research funding for Megan Styles; the CRC Future Rural Africa at the University of Cologne for providing research funding for Mario Schmidt and Anna Lisa Ramella; our PI Martin Zillinger; our co-contributors in this issue and our co-editor Uroš Kovač for their valuable feedback; our research assistant Robinson Ogwedhi; Gerda Kuiper, Eric Kioko, and Michael Bollig for organising the workshop that brought the authors of this article together; and not least the two anonymous reviewers who provided thorough comments to improve the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Kuiper, Labour in Kenya; Styles, Roses from Kenya.

2 Milena Veselinovic, “Got roses this Valentine’s Day? They probably came from Kenya.” CNN, 16 March 2015. https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/16/africa/kenya-flower-industry/index.html

3 Shadrack Kavilu. “Kenya’s flourishing flower sector is not all roses for Maasai herdsmen.” Reuters, 30 June 2016. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-landrights/kenyas-flourishing-flower-sector-is-not-all-roses-for-maasai-herdsmen-idUSKCN0ZG0Z0

4 Dolan, “Market Affections”.

5 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity”, 770.

6 Edensor, “Waste Matter”, 313-14.

7 Nielsen, “Futures Within”, 10.

8 Ibid, 398.

9 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity”, 773.

10 Bize, “The Right to the Remainder”.

11 Business Daily Africa, “Nothing rosy for Karuturi as world marks lovers’ day.” 12 February 2019. https://www.businessdailyafrica.com/bd/markets/capital-markets/nothing-rosy-for-karuturi-as-world-marks-lovers-day-2238456

12 Interview with Stephen, Naivasha, 2 March 2020, conducted by Anna Lisa Ramella.

13 De Jong and Valente-Quinn, “Infrastructures of Utopia”, 333.

14 Doherty, “Maintenance Space”.

15 Ibid, 24.

16 Gordillo, “Ships Stranded in the Forest”, 165–66.

17 Geissler and Lachenal, “Brief instructions”, 17.

18 When referring to our research participants, we use pseudonyms throughout to protect their anonymity.

19 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity”, 777.

20 Edmund Sanders, “Progress Blooms on Kenyan Soil,” Los Angeles Times, 3 June 2006. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-jun-03-fi-flowers3-story.html

21 Interview with farm manager, Naivasha, 7 May 2008, conducted by Megan Styles.

22 Paul Wafula, “Wilting rose: How Karuturi coughed up his flower empire,” The Standard, 8 July 2018. https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/article/2001287159/wilting-rose-how-karuturi-coughed-up-his-flower-empire.

23 Middleburg, “‘Largest’ rose grower Karuturi finally brought down?”.

24 Ten interviews between 2 and 10 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

25 Interview with manager, Naivasha, 7 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

26 Interview with owner of neighbouring farm, Naivasha, 9 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

27 Interview with former production manager, Naivasha, 8 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

28 Interview with Stanley, Naivasha, 8 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

29 Interview with Joseph, Naivasha, 8 July 2014, conducted by Megan Styles.

30 Wafula, “Wilting Rose”, Op. Cit.

31 Hortibiz Daily World News, “Karuturi workers fault appeal court judges,” 30 January 2019. https://www.hortibiz.com/news/?tx_news_pi1[news]=27191&cHash=43f27860f137521113f b6e10793f4117

32 Ramella, “Material Para-Sites”.

33 Interview with a current maintenance worker, Naivasha, 2 March 2020, conducted by Anna Lisa Ramella.

34 Ibid.

35 Edensor, “Waste Matter”, 314.

36 Ibid, 313.

37 Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World, 6.

38 Geissler, “Stuck in Ruins”, 557.

39 Hage, “Waiting out the Crisis”.

40 Hage, “A not so multi-sited ethnography of a not so imagined community”.

41 Hage, “Waiting out the Crisis”, 97.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Interview with Union representative, Naivasha, 2 March 2020, conducted by Anna Lisa Ramella

45 Ramella, “Material Para-Sites”.

46 Ibid; Ramella and Zillinger, “Future-making on Hold”.

47 Smith, “Nairobi in the Making”, 12.

48 Pardy, “The Shame of Waiting”, 200ff.

49 Robins, “Waiting for Rain in the Goulburn Valley”, 77.

50 Gasparini, “On Waiting”, 31.

51 Bize, “The Right to the Remainder”.

52 Interview with school teacher, Naivasha, 25 October 2019, conducted by Anna Lisa Ramella

53 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity”, 769.

54 Ibid, 771.

55 Tousignant, “Half-Built Ruins”, 36.

56 Gupta, “Suspension”.

57 Choy and Zee, “Condition - Suspension”, 212.

58 Ramella, “Material Para-Sites”; Ramella and Zillinger, “Future-making on Hold”.

59 Dawdy, “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity”, 776.

60 Bear, “Speculation”.

61 Nielsen and Pedersen, “Infrastructural Involutions”, 258.

Bibliography

- Bear, Laura. “Speculation: A Political Economy of Technologies of Imagination.” Economy and Society 49, no. 1 (2020): 1–15.

- Bize, Amiel. “The Right to the Remainder: Gleaning in the Fuel Economies of East Africa’s Northern Corridor.” Cultural Anthropology 35, no. 3 (2020): 462–486.

- Choy, Timothy, and Jerry Zee. “Condition—Suspension.” Cultural Anthropology 30, no. 2 (2015): 210–223.

- Dawdy, Shannon Lee. “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity.” Current Anthropology 51, no. 6 (2010): 761–793.

- De Jong, Ferdinand, and Brian Valente-Quinn. “Infrastructures of Utopia: Ruination and Regeneration of the African Future.” Africa 88, no. 2 (2018): 332–351.

- Doherty, Jacon. “Maintenance Space: The Political Authority of Garbage in Kampala, Uganda.” Current Anthropology 60, no. 1 (2019): 24–46.

- Dolan, Catherine. “Market Affections: Moral Encounters with Kenyan Fairtrade Flowers.” Ethnos 72, no. 2 (2007): 239–261.

- Edensor, Tim. “Waste Matter - The Debris of Industrial Ruins and the Disordering of the Material World.” Journal of Material Culture 10, no. 3 (2005): 311–332.

- Gasparini, Giovanni. “On Waiting.” Time & Society 4, no. 1 (1995): 29–45.

- Geissler, Paul Wenzel. “Stuck in Ruins, or Up and Coming? The Shifting Geography of Urban Public Health Research in Kisumu, Kenya.” Africa 83, no. 4 (2013): 539–560.

- Geissler, Paul Wenzel, and Guillaume Lachenal. “Brief Instructions for Archaeologists of African Futures.” In Traces of the Future. An Archaeology of Medical Science in Africa, edited by P.W. Geissler, G. Lachenal, J. Manton, and N. Tousignant, 15–30. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Gordillo, Gastón. “Ships Stranded in the Forest.” Current Anthropology 52, no. 2 (2011): 141–167.

- Gupta, Akhil. “Suspension.” Theorizing the Contemporary, Fieldsights. September 24, 2015. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/suspension.

- Hage, Ghassan. “A Not So Multi-Sited Ethnography of a Not So Imagined Community.” Anthropological Theory 5, no. 4 (2005): 463–475.

- Hage, Ghassan. “Waiting out the Crisis: On Stuckedness and Governmentality.” In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 97–106. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2009.

- Kuiper, Gerda. Labour in Kenya. Cut Flower Farms and Migrant Workers’ Settlements. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

- Nielsen, Morten. “Futures Within: Reversible Time and House-Building in Maputo, Mozambique.” Anthropological Theory 11, no. 4 (2011): 397–423.

- Nielsen, Morten, and Morten Axel Pedersen. “Infrastructural Involutions. The Imaginative Efficacy of Collapsed Chinese Futures in Mozambique and Mongolia.” In The Imagination. A Universal Process of Knowledge?, edited by N. Rapport, and M. Harris, 237–262. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2015.

- Pardy, Maree. “The Shame of Waiting.” In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 195–209. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2009.

- Ramella, Anna Lisa. “Material Para-Sites: Lateral Future-Making in Times of Fragility.” Etnofoor Futures 21, no. 1 (2020): 43–60.

- Ramella, Anna Lisa, and Martin Zillinger. “Future-making on Hold. Pandemic Audio Diaries from two Rift Valley Lakes in Kenya.” boasblog Witnessing Corona, 5 June. https://boasblogs.org/witnessingcorona/future-making-on-hold/, 2020.

- Robins, Rosemary. “Waiting for Rain in the Goulburn Valley.” In Waiting, edited by Ghassan Hage, 76–85. Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 2009.

- Smith, Constance. Nairobi in the Making: Landscapes of Time and Urban Belonging. Oxford: James Currey, 2019.

- Styles, Megan A. Roses from Kenya. Labor, Environment, and the Global Trade in Cut Flowers. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019.

- Tousignant, Noémi. “Half-Built Ruins.” In Traces of the Future. An Archaeology of Medical Science in Africa, edited by P.W. Geissler, G. Lachenal, J. Manton, and N. Tousignant, 35–38. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.