ABSTRACT

In the course of Kenya’s Vision 2030 development plan, the Kenyan Northern Rift Valley recently became the playground for new stakeholders, interests and speculations. Large-scale development projects, such as the geothermal exploration in Tiaty East sub-county, is one of them and is described as game-changer in a formerly marginalized area. This article explores the case of Mt. Paka, a dormant volcano, where the Kenyan Geothermal Development Company (GDC) recently finished their exploratory drillings and established a road and water infrastructure for the geothermal project and the adjacent communities. Drawing on ethnographic research, this contribution examines the dynamic processes of ruination, reappropriation and negotiation along the newly built water infrastructure. While GDC is constantly trying to counter the ruination of pipelines with maintenance and retrofitting, local communities utilize leakages along the infrastructure, maintaining it in its ruined state to satisfy their own needs. This study highlights how the water infrastructure at Mt. Paka materializes in unexpected ways and shows its transformative potential in two directions: the ruination and the reappropriation of it.

When following new murram roads in Tiaty East (Baringo, Kenya), the first thing that catches the visitor's eye, apart from the beautiful and rough semi-arid landscape, is the water pipeline that snakes up the mountain, accompanying the road all the way from Lake Baringo up to the remote mountain sites of Paka, Silali and Korossi. Originally built to enable the drilling activities of the Kenyan Geothermal Development Company (GDC), the pipeline created a multitude of expectations and opportunities, but also risks and uncertainties for the communities living in the area. First and foremost, the pipelines carried the promise of a constant source of water in an area that lacks permanent water bodies and has been affected by droughts in the past.

Next to the drilling site, a GDC watchman recruited from the area told me:

GDC told us ‘You will drink water at the top of Mt. Paka’. And now, this water is coming, it is here already. That was a surprise. I never believed the water to come all the way from the lake to here. But now, the water is here.Footnote1

In addition, the pipeline network was in constant need of maintenance. Especially as construction continued around Mt. Silali and Mt. Korossi, maintenance in the Paka area often came to a halt and the demand for water often outstripped the patience to wait for a maintenance crew. This in turn, led to a heavy dependence on ‘reliable’ leakages along the pipeline, which often occurred during episodes of increased pumping pressure. There were also several instances of individuals destroying the pipeline connections to create such leakages. While the GDC promoted the exclusive usage of water from designated water points, reappropriation of leakages became the norm in many places. However, as this reappropriation also involved increased maintenance effort, the GDC tried to reduce unintended utilization of infrastructure and engaged in constant (re-)negotiation with communities, which eventually led to the establishment of local water point committees to give communities more agency over the new resource and to reduce maintenance burden of the GDC.

In this contribution, based on ethnographic data collected from 2018 to 2020 (9 months in total) in Tiaty East sub-county, I argue that infrastructure materializes in unexpected ways and rarely exactly as planned. This in turn, leaves room for various (unintended) processes, such as the reappropriation and destruction of pipelines or the protest against the infrastructure, shaping the future of the infrastructure and influencing further accompanying processes (e.g. maintenance, retrofitting, further ruination, (re-)negotiations, etc.). Here, residents play a major role as they maintain or utilize these processes, mainly by reappropriating the infrastructure to shape it to their own needs. During my fieldwork, I was able to follow the introduction of the water infrastructure from its construction to its eventual implementation, as well as to observe shifts in perceptions within the community over a crucial time in the GDCs project. The case of Tiaty East provided an interesting entry point for ethnographic research for several reasons. First, the construction of infrastructure in the area is relatively new and, in some places, not yet completed. Therefore, it represents a setting in which the infrastructure is subject to different temporalities: some parts are not yet finished, some are already implemented and in operation, while others are already subject to different (de-)generative processes. Second, the new infrastructure represents such a far-reaching social, economic, and ecological change in the area that its presence and use is constantly (re-)negotiated or (re-)defined by the GDC and the community. In order to better understand how infrastructures materialize, we have to take a deeper look at these processes that often arise from the various temporalities of the different phases of the infrastructure’s “life cycle”.

The promise, construction, implementation, maintenance and usage of infrastructure are all subject to processes of ruination (e.g. wear and tear, technical failure, human error) and regeneration (e.g. through maintenance, retrofitting or reappropriation). Ruination and reappropriation emphasize both constructive and destructive processes at play around infrastructure. It is important to note that many of these processes are often unintended (or unpredictable) by planners, but are nonetheless constitutive for the infrastructure’s functionality and usability. Such processes can for example include increased accessibility (roads) or improved health (access to water) which in turn might lead to further socioeconomic transformation. On the other hand, more degenerative processes such as contestation, destruction or ruination might lead to the infrastructure’s failure (of its intended function), but can as well enable a variety of new generative processes. Ruination as a concept reveals these underlying, accompanying and subsequent processes of the system in which the infrastructure is constructed.

Ruination can be an action, a state and a cause, which may have overlapping effects, but is characterized by its own temporality.Footnote2 It links past promises to physical infrastructure in the present and its future materiality, as well as to future emergent activities related to infrastructure.Footnote3 Thus, ruins or instances of ruination can be seen as ‘epicenters of renewed collective claims […], as sites that animate both despair and new possibilities […] and unexpected collaborative political projects’.Footnote4 Reappropriation, on the other hand, creates different temporalities of ruination: the unintended utilization of leakages along the pipeline might have increased maintenance efforts for the GDC, but at the same time it made an otherwise often dysfunctional infrastructure usable for many parts of the community in the first place. Therefore, reappropriation may be responsible for further processes of ruination,Footnote5 but at the same time it can help to make the infrastructure work, depending on the point of view.Footnote6 Through processes of ruination and reappropriation that affect its functionality and usability, infrastructure becomes visible and acted upon.Footnote7 While the ruination of infrastructure is the norm rather than its constant planned functionality,Footnote8 this does not necessarily lead to the inevitable end (or complete breakdown) of infrastructure: ruination can be stalled through repair and maintenance, while further enabling new transformative processes, such as reappropriation.Footnote9 Therefore, one should focus less on the materiality of infrastructures or ruins themselves, but on their ‘reappropriation, neglect, and strategic and active positioning within the politics of the present’.Footnote10 Such politics include the constant (re-)negotiation of the “life” of the infrastructure.Footnote11

Looking at the newly constructed water points and pipelines in Tiaty East, I will explore how the promise of infrastructure shapes communities’ expectations for this specific infrastructure, and ultimately the utilization of it. As this promise is realized differently in the prospect areas of the GDC, the usage of the infrastructure, as well as the expectations for it, evolve differently and need to be constantly (re-)negotiated and (re-)defined. The ruination and reappropriation of water points and pipelines offers insight into how infrastructure is shaped by these negotiations, and at the same time, how infrastructure shapes the lives of communities and the activities of the GDC.Footnote12 By focussing on unintended or unplanned processes I aim to illustrate the different ways in which people occupy infrastructure, regardless of its current state. In terms of the new dynamics that emerge with such large-scale infrastructures, I focus on ruination as an inherent process of infrastructure that often necessitates maintenance and processes of reappropriation in the first place. Moreover, the ongoing negotiations around infrastructure highlight the fact that its transformative potential, both in its ruination and its regeneration, varies widely in scale, quality and beneficiaries.Footnote13

Water scarcity in Tiaty East

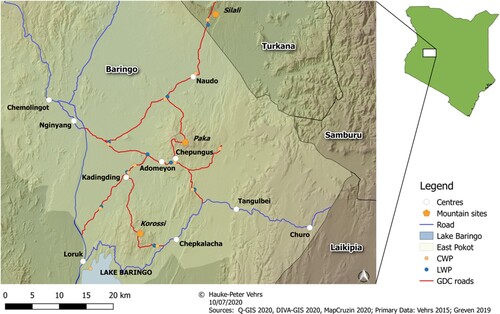

Tiaty East is a sub-county of Baringo County, Kenya, and is located in the Northern Rift Valley. The semi-arid landscape is characterized by lowlands to the west and highlands along the escarpments to the east. Several dormant volcanoes are scattered in the lowlands: Mt. Paka, Mt. SilaliFootnote14 and Mt. Korossi. In my research throughout Tiaty East I concentrated on the areas around these mountain sites (see ). Tiaty East is a remote part of Baringo County and is mainly inhabited by the Pokot. There are only few rural economic centres (e.g. Nginyang, Tangulbei, Churo, Amaya), but most homesteads are separated from each other, scattered in the landscape and often built far away from centres and roads. However, this depends to a large extent on a household’s livelihood.Footnote15 While the Pokot are active in a variety of livelihoods, livestock husbandry remains dominant. Especially in the lowlands, people identify themselves as pastoralists, although some venture into agriculture, casual labour and businesses.

Figure 1. Map of Tiaty East and Tiaty West with new and upgraded roads, as well as LWPs and CWPs constructed by the GDC.

The dependence on animals is accompanied by a constant need for water and pasture, which requires high mobility of households (or parts of them). While Tiaty East is considered to have good grazing areas even though it is declining due to bush encroachment,Footnote16 water is a scarce resource. The annual average rainfall is estimated at 600 mm/m², but is subject to high interannual fluctuations. Normally, Tiaty East has a rainy season from April to July and short rains in October/November.Footnote17 Temperatures can reach up to 40 degree Celsius in the dry season and are consistently high throughout the year (26 degrees Celsius annual average temperature). There are no perennial rivers in Tiaty East, and most rivers only carry water for short periods. Only the larger rivers Nginyang and Amaya can carry water for several months and the nearest permanent water source is Lake Baringo in the south (about 30 km from Mt. Paka). Therefore, most people have to rely on pan dams and the lake as water supply. The limited choice of water sources and the fact that they are often shared with livestock leads to a variety of potential dangers in the form of diseases or conflicts between humans, livestock and wildlife. Since the area has long been plagued by cattle rustling among pastoral communities, conflicts with neighbouring communities remain an issue, especially in the grazing areas along the Turkana border and on the shores of Lake Baringo. While the water supply via solar pumps, boreholes and wells is sporadically distributed, only 10% of the populationFootnote18 (can) rely on it due to a general lack of functionality and maintenance.

Tiaty East and the neighbouring Tiaty West sub-county (see )Footnote19 have been historically and politically marginalized by colonial administration and the Kenyan state, especially regarding infrastructure. External interventions or interaction with the outside have been rare. In pre-colonial times, contact with Europeans and traders was rather sporadic. The Kolloa massacre in the early 1950s, a brief resistance to the British rule that was violently suppressed, was one of few intense interactions between the Pokot and the colonial power that were usually limited to tax collections.Footnote20 In the post-colonial period, church interventions along roads began with the construction of churches, schools and dispensaries.Footnote21 The Kenyan State's commitment was limited to a few health centres and a handful of boreholes, so that the development of infrastructure in East Pokot remained in the hands of the churches or other non-state actors.Footnote22 From a government’s perspective, the area was treated as economically uninteresting, described merely as rangeland with no further potential.Footnote23 It was not until the late 1990s that a government office was established,Footnote24 which shows how little interest there was in developing the area. Generally, the infrastructure in Tiaty East has remained sparse or in poor shape. The only tarmacked road is the highway from Nakuru to Elgeyo-Marakwet County (B4) and its section passing Tiaty East in the west was completed only a few years ago. The health care facilities are few or understaffed, and often located close to centres and roads, making them hardly accessible for those parts of the population living in more remote areas.Footnote25 Access to a (safe) water supply is lacking in the entire sub-county and annual reports of Baringo District showed little to no commitment to water projects from 1970 to 2001.

Geothermal exploration: the need for infrastructure

As part of Vision 2030, the Kenyan government has set itself the goal to improve ‘the energy infrastructure network and [to] promote development and use of renewable energy sources’Footnote26 in order to support the country's economic growth. Geothermal resources play a prominent role in this vision. The areas along the Northern Rift Valley have a high potential for geothermal resources, as the current geothermal exploitation in Menengai (Nakuru) and Olkaria (Naivasha) have shown.Footnote27 For this reason, Tiaty East has become the playing field of new stakeholders, interests and speculations.Footnote28 In 2009, Kenya’s GDC took over the mandate of the so-called Baringo-Silali block, surveying the area for potential prospecting sites. Tasked with developing steam fieldsFootnote29 and selling geothermal steam for electricity generation to Kenya Electricity Generating Company PLC (KenGen) and private investors, the GDC identified potential sites for exploratory drilling around the three volcanoes (Mt. Paka, Mt. Korossi and Mt. Silali) with a capacity of 100 MW from each volcano.Footnote30 However, to develop this “new” resource, the GDC first had to build the necessary ancillary infrastructure. After obtaining an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) license from the Natural Environment Management Authority in 2013, establishing a framework for community engagement and obtaining land access rights from the community,Footnote31 the GDC began building a new road network connecting all potential prospect sites to the highway (B4) and other roads. In total, more than 120 km of roads have been built or upgraded, connecting several locations throughout Tiaty East. The construction of roads was followed by the construction of water infrastructure. From 2017 to mid-2019, the GDC focused on completing its water supply system, as drilling requires a constant flow of water. Therefore, tank sites were levelled to build large water tanks to provide drilling water to the rig (see ). Pump station I on the shore of Lake Baringo pumps water through a 70 km pipeline system via a booster station close to Chepungus to two water tanks at the top of Mt. Paka. In addition, pipelines from Mt. Paka to Mt. Korossi and Mt. Silali were constructed in preparation of future exploration drilling.

The promise of water: between hope and scepticism

Originally, the GDC planned to supply water to the communities living in proximity (or on the way) to prospect sites via water trucks as part of an early agreement between both parties, but the communities became increasingly dissatisfied with the fact that huge amounts of water were to be pumped from Lake Baringo for drilling, without reaching them. Furthermore, water supply via trucks appeared to be rather sporadic and not able to reach all areas. After many complaints, negotiations and road blocks, the GDC reconsidered and decided to build water points to secure the future of the project. Declared as a corporate social responsibility measure and financed by the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau,Footnote32 the GDC decided to build 20 community and livestock water points along the pipelines and in larger settlement areas. It is important to note that many of these water points remained unfinished or empty: water only flows during drilling operations, so water points around Mt. Silali where drilling had not yet started have been neglected. At the time of writing of this article, only the water points around drilling activities at Mt. Paka and Mt. Korossi have been integrated in the water system cycle.

I visited Mt. Paka for the first time in August 2018 for preliminary exploration. It was a crucial phase for the GDCs activities as it had just completed the water infrastructure in the area and was preparing the first drilling rig. While the construction of water pipelines and water tanks was completed, CWPs and LWPs still had to be built and connected. After almost ten years of preparation, the start of drilling was seen as a new starting point for the project, but also for new developments in the area. The GDC staff was optimistic about the success of the project and its impact not only on the national energy supply but also on the communities in the area. The staff were hopeful to start drilling as soon as possible, and eagerly awaited confirmation from the headquarter in Nairobi. One GDC supplier emphasized the transformative nature of the GDCs activities, noting this after drilling had commenced in December: ‘Drilling and the whole GDC operation are like a metamorphosis. Every layer we drill through is a step to the end result. Every step is changing everything for everyone.’Footnote33 Among national officials I interviewed, many expressed hopes about the impact of the GDC in the area, stating the positive effect of the project on security issues due to the new accessibility, and emphasizing that the government would now be able to reach people with additional services such as education and health. In addition, many officials expected a shift towards more sedentary life in areas with access to water.Footnote34

Geothermal resources promise to bring many benefits to different stakeholders. At the national level, hopes are high that intensifying the use of geothermal energy will improve Kenya’s base load power, achieve the goals formulated in Vision 2030, lower energy tariffs, and thus increase energy consumption. In addition, improved accessibility through the new road network could improve security management and peace-building efforts.Footnote35 In general, there was a widespread perception that the GDC project would open up a formerly ‘untouched’ (by the state) region and eventually integrate it into the rest of Kenya resulting in more revenues and follow-up projects. Although future energy production will be fed into the national grid, it will not directly benefit the communities in the area. According to the new Energy Act,Footnote36 royalties from sales will be shared between the national government (75%), the county government (20%) and the affected communities (5%). As royalty payments will not be made until the distant future due to long duration of exploration before the construction of a powerplant is even considered, the lack of direct benefits from the drilling for communities has created constant friction between the GDC and the communities.

The inclusion of CWPs and LWPs was an important step in (re-)gaining the trust of the communities. The announcement of the new water points raised hopes among many, but was also met with scepticism. Not everyone was as convinced and optimistic as the GDC watchman quoted above. While some welcomed the project and were looking forward to the promised water points, others remained sceptical, claiming that they had not benefited from the GDC since they arrived in the area almost ten years ago, and therefore did not expect anything more. The women were vocal in their support for the GDC as they would benefit the most from a constant water source. My host's wife told me: ‘The area was good, but I remember it was all about thirst. It was all about water. We had to get it from long distances.’Footnote37 This sentiment was shared by most women I spoke to, as they could relate to the issues and dangers connected to water fetching. In most households in the area, women are responsible for daily household chores, including fetching water, an arduous task that entails long days of walking to distant places (such as Nginyang or Tangulbei). The significant reduction in these walking distances would lead to a substantial increase in time for other tasks or activities. The ability to fetch water close to the homesteads is also related to the insecurity in the area, as close and secure water sources reduce the danger for women and children being robbed or attacked. Several young herders shared this view, especially regarding flocks of shoats (a common term for sheep and goats) and calves that would benefit from the water source, shortening grazing routes or even eliminating the need for migrating. Herding activities, grazing routes and intervals are highly dependent on water availability and reliable water sources would have far reaching impacts on mobility patterns. The prominent introduction of the water points by GDC and the promise they hold, made them a focal point of hope and interest for the community, especially as the dry season approached.

However, not everyone shared the view that permanent water sources in form of waterpoints would be beneficial. The majority of elders supported the idea of CWPs, but remained critical of LWPs. A major concern relates to the role of Mt. Paka as a reservoir for grazing in the dry season. Herders would avoid grazing in this area during the rainy season to allow pasture to regrow. Cattle would only graze on the mountain during the dry season and then return to the lake or rivers for water. Permanent availability of water at Mt. Paka would effectively eliminate the need to return to distant water sources, thus increasing pressure on pasture.

As he watched herders moving up the mountain, one elder mused:

It [water] has changed the grazing. Before, there was no water. That was good because animals leave to find water. Herders will move out and some grass will be left. […] But with the water now, people are up in the hill. They graze there all the time and don’t leave. With water comes a lot of change. The area is getting dry.Footnote38

The heterogenous perception towards the new infrastructure shows that the promised potential of transformation (in whatever direction) is not unanimously shared or desired. Moreover, the benefit of one may be perceived as disadvantage by others. The sheer lack of water in the area prompted the GDC to promote the new water infrastructure extensively (to investors, media and communities). And while benefits of varying degree are already visible (e.g. potentially closer water source with implications for general well-being, security, hygiene, etc.), other, longer-term impacts were often neglected, especially with regard to the potential effects on grazing areas. The promise of water laid the foundation for high expectations and hopes for some kind of (positive) change, but also a basis for uncertainty and contestation. It also spurred possibilities of ruination and reappropriation; processes I turn to in the following sections.

Leakages: the condition of ruination

When I returned to Mt. Paka in the dry season of 2019, the first drilling rig was operational, but despite promises, many water points were still not functional. Water points, especially in the area of Mt. Korossi and Mt. Silali, were not yet completed or connected due to delays and long construction periods. Additionally, water points that had already been built seemed to lack water more often than they carried water. This seemed counter-intuitive to me, because the water ran through the main 11-inch pipeline to ensure the ongoing drilling work, but despite full tanks at the top of the mountains, most of the small 5-inch pipelines leading to the water points remained empty. While walking along, eventually I noticed that larger groups of people were occupying certain points along the main pipeline. Since many water points were not yet functioning, people began to occupy leakages along the pipeline. These leakages usually occurred at the pipeline joints, or around the pressure release valves (PRVs) that were installed every few hundred metres (see ). This was a result expected by the GDC as a consequence of normal wear and tear. High pressure, rough terrain and material abrasion contribute to the ‘predicted’ ruination of the water infrastructure which should be counteracted by regular maintenance. However, considering the large project area, limited staff, and insecurity, maintenance could often take weeks depending on the location, the importance for the overall infrastructure and ad-hoc solutions. This condition of ruination, while predictable, also led to the emergence of unintended processes and usages (see below for more). Reliable leakagesFootnote39 had become a point of attraction for many in the communities, especially in areas without functioning water points. Many were regularly visited, especially by women and children, as this water source offered a nearby, safe and time-saving alternative. Herders with small livestock or young cattle also regularly visited these leakage points.

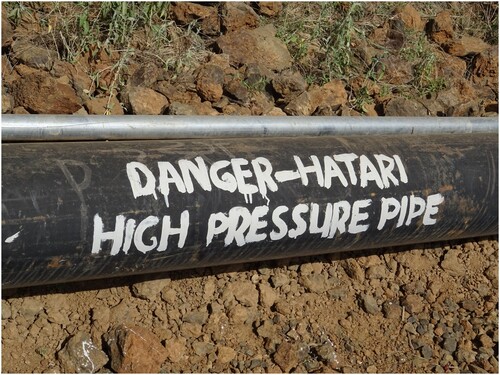

The GDC launched a campaign to sensitize people about the risk associated with this unintended use of leakages. First, the GDC emphasized that the pipeline contained unfiltered lake water, which is associated with high concentration of fluoride and should not be consumed. Given that most people in this area rely primarily on pan dams (shared with livestock) and lake water, it is not surprising that these attempts to stop consumption of leakage water have largely failed to date. The second concern for GDC was the condition of its infrastructure and the potential danger the main pipeline could pose in the event of a high-pressure burst. Downhill, the pressure in the main pipeline could reach up to 45 bar. While warnings along the pipelines (see ) had only a marginal effect due to the high illiteracy rate in the area, witnessing several high-pressure bursts made people more cautious in dealing with leakages, especially when the outflow significantly increased. ‘These pipes have a lot of pressure, like a bomb when it bursts. It can kill someone’Footnote40 described one shop owner the danger. On the other hand, many people would rather take the risk than walk long distances to fetch water. ‘When you see us around here, it is because we rely on these pipes for water. But when it bursts, it is really dangerous’Footnote41 argued another shopkeeper. Some would even knowingly ignore the risk, resting, stepping on or balancing over pipelines, only to flee when the sound of water pumping through the pipeline exceeds a certain threshold. Although there have been no casualties so far, the risk of outbursts has often been raised by community members in negotiations with the GDC to convince (or pressure) the company to properly maintain the pipeline, and subsequently install more CWPs.

Figure 4. 11-inch main pipeline and 5-inch community pipeline with warnings in English and Kiswahili. Photo courtesy David Greven.

Within a few months, the water infrastructure became central not just in the daily lives of the communities, but also in negotiations with the GDC. Discussions about the benefits, the drawbacks, the distribution and especially the state of the infrastructure took up a considerable amount of time during barazas and kokwö (public and elders’ meetings). Interestingly, pipeline maintenance was not necessarily accompanied by the disappearance of unintended occupation of the infrastructure. Rather, maintenance teams often intentionally focused on larger and riskier leakages, skipping those that were irrelevant to overall functionality. Additionally, the periodic adjustment and regular draining of PRVs often resulted in large leakages that became the main source of water for some areas. Therefore, in some cases, the condition of ruination was deliberately maintained and tolerated by the GDC in order to preserve this unintended source of water and subsequently maintain good relations between the communities and the company.

Destruction: the act of ruination

Not all of these leakage points were caused by pressure or technical failure: some were rather a product of (un-)intentional destruction. Several individuals began to tamper with the PRVs or the connections between the pipes to create leakages. Successfully creating a leakage along the 11-inch main pipeline requires a considerable amount of force and some kind of tool (e.g. stones, metal rods, knives, or wrenches). Eventually, the GDC started to build metal casings around the PRVs and strengthened the connections to prevent further interference, but these were also targeted to reach water or use the metal for further purposes (see ). Subsequently, the GDC started to communicate via barazas and the elders that the pipelines were indeed the property of the government and that abuse would be sanctioned accordingly, with limited success. It should be noted that, despite the new accessibility, Paka, like many areas in pastoralist Northern Kenya, remains neglected or avoided by regular police supervision. Therefore, enforcement of such sanctions remains in the hands of elders or the community at large, or would require the GDC to actively involve police officers. As communities in the area share a common distrust of the police and the local GDC management is interested in maintaining good relations, the police have only been involved in very serious cases, e.g. involving staff safety. Promises by elders such as: ‘In case someone breaks the pipe, we will take care of it and hunt him to the authorities’Footnote42 were made in the barazas, but I rarely heard of cases where culprits were actually identified or brought to the authorities.

Figure 5. PRV with missing bolt (l.); protective casings for PRVs (m.); destroyed casing (r.). Photo courtesy David Greven.

While actively ruining the main pipeline did not necessarily affect the drilling activities, it greatly increased the already strenuous maintenance work and the risk of bursts. Even more problematic was the practice of destroying 5-inch pipelines leading to the water points. These small pipelines often branch out several metres from the main one and can easily break at their joints under too much pressure or force. ‘It [pipeline] is so delicate, even a child can hit it with a stone and it breaks.’Footnote43 a teacher told me, adding that many of his pupils rely on the leakages for their daily water supply. Moreover, the breakage of fully functional 5-inch pipelines inevitably leads to water shortages at designated water points. These shortages, in turn, often led to recriminations between different communities in the area. Some elders blamed improper maintenance or the construction work by the contractor ‘who did not connect the pipelines properly.’Footnote44 But, the GDC and elders generally tended to blame or suspect herders and children for most cases. The reasons for destruction (given by the GDC and the elders) often ranged from the urgent need for water, to convenience, to boredom. I witnessed cases of attempted destruction by children and herders, but anyone including livestock and wildlife is able to easily break the pipelines. Nonetheless, all parts of the community would immediately occupy these breakage points as soon as they occurred. Broken community pipelines in areas with functioning water points would still have a substantial outflow of water as long as water was running at all. In preparation, women often stored jerry cans near breakage points to wait for the water to be pumped. In addition, herders with livestock would fill home-made throughs (made of jerry cans or wood) with water where pipelines were broken, to facilitate the access for livestock and to avoid wasting water (see ).

Figure 6. Cattle drinking water from wooden trough at a broken community pipeline. Photo courtesy David Greven.

But the destruction of pipelines occurred not just out of the need for water or convenience. In the Mt. Korossi area, a slightly drunk man boasted to me that he had recently vandalized the pipeline. When asked why, in view of the fact that the pipeline was not carrying water at that time, he accused the GDC of not fulfilling its promises:

They [the GDC] promised water with water boosters but they never came […] Some of us had to move our homesteads because of the GDC, but were still not compensated […] They promised us water but it doesn’t reach here. That is why we hit the pipeline. We feel cheated.Footnote45

In general, theft of materials or breakages along empty pipelines were not uncommon, especially towards Mt. Korossi and Mt. Silali, where many water points remained unfinished and unconnected. Another example of interference with infrastructure was evident during routine maintenance activities. There were several reports of herders threatening engineers and maintenance workers, forcing them to open certain PRVs, or welding small holes in the pipelines. Again, the GDC mostly called on the elders to reach an agreement instead of calling the police and such actions were unanimously condemned (at least verbally). Thus, both the GDC and the community often relied on ad-hoc solutions and interactions around the water infrastructure to ensure its usability and good relationships. The GDC sees the destruction of pipelines as clear case of vandalism that affects the functionality of the entire water infrastructure. Deliberate ruination of pipelines is a risk that could accelerate their ‘predicted’ ruination, increasing maintenance efforts and safety risks for both the communities and the geothermal development. In the communities, the perception of the issue is different. There is some common understanding of ownership regarding the water infrastructure, which certainly derives from the fact that the GDC operates on communal landFootnote46 and the provision of water is part of the agreement. As a result, many people feel entitled to receive water all the time, and this was regularly made clear during meetings. While the condition of ruination was in some ways mutually beneficial for the GDC and the communities, the constant acts of ruination forced the GDC to respond to the problem by improving maintenance and retrofitting efforts, but also by raising awareness and actively (re-) negotiating the usage of the infrastructures. At the same time, the communities that did not have functioning water points or were affected by the partially destroyed pipelines also came under pressure to solve the issue with their neighbours and the GDC.

Interaction with infrastructure: ruination, reappropriation and negotiation

In 2020, the GDC had connected most of the water points in the three prospect areas to the main pipeline, but leakages and breakages still limited their functionality. Pipeline maintenance remained a problem in some places,Footnote47 and maintenance crews were often the target of community discontent and frustration, particularly in areas facing water scarcity due to the ongoing dry season. Only in a few places, such as Chepungus and Kadingding, the CWPs and LWPs functioned very reliably and were places of lively activities. The water points had become meeting points for all community members. The kokwö was regularly held nearby, women fetched water and washed clothes, while herders watered their animals or took showers. Other empty or non-functioning water points however led to overcrowding at the functioning LWPs. ‘There is a breakdown […] down there in Riongo [and] Tuwo. They all are coming here. Even Korossi now. The whole of Korossi is here. This is the only place where people can get some water, day and night.’Footnote48 reported an elder in Kadingding. Kadingding was able to cope with the rush to its water points because the main pipeline to Mt. Paka and Mt. Korossi converges here, so there are several PRVs. In coordination with the GDC, the main gate valve was opened, creating outflows that supplied the large numbers of livestock in addition to the other LWP. Whereas other places without a regulated way for increased water discharge sometimes struggled to cope with the amounts of animals. This in turn led many to believe that the capacity of the water infrastructure was inadequate for the amounts of livestock held in the area.

On the other hand, many people with high expectations towards the water supply, had already adapted to the new (but still unreliable) water infrastructure: some people, primarily women, preferred to wait for hours at water points or reliable leakages for the water to be pumped instead of relying on “past” water sources. Others, who were engaged in agriculture, diverted water from the working water points (or leakages) to irrigate their shambas (fields) or prepared them next to them. Several people ventured into businesses and began constructing dukas (shops) near water points as they would attract customers. Within one year, three dukas were finished in Chepungus alone. Before the implementation of the water infrastructure, the closest dukas could only be found in Adomeyon. Following the same pattern, shopkeepers from Kadingding have in the past abandoned their shops to benefit from a new borehole in Adomeyon, constructed by US missionaries around 2014. Therefore, Adomeyon was not included in the planning of water points. The borehole broke down in 2018 and has not been repaired since, so that some store owners had to close again and consider moving towards Chepungus following the water. However, the majority of stores continued to rely on large leakages in Adomeyon to ensure customers. In addition, the possibility to get water within the area led to the establishment of several so-called drinking places along the pipeline. Here, women brew and sell busaa and changaa, illicit brews made from maize. Brewing is a common activity to diversify household income and one of the few ways to earn money besides working in a duka or taking advantage of the sparse employment opportunities. While brewing is a thorn in the side of many (formally) educated or church affiliated people as well as state officials, it occurs area-wide and is becoming more visible, i.e. drinking places are less hidden, and closer to roads and water infrastructure.

The ongoing problems with maintenance along the pipeline, the conditions and acts of ruination, the different ways people use and occupy the water infrastructure, and the resulting tensions between the GDC and some communities led the GDC to promote the election of so-called Water Point Committees within the communities. These newly elected committees, consisting of two elders, one woman, and one youth in each location, were tasked with monitoring the pipelines, raising awareness and organizing the opening and closing of water points. Problems or violations related to the water infrastructure were to be reported to the GDC. This should effectively reduce the need for maintenance, as the identification of problems would now be the responsibility of the committees. It could be argued that the community would have more agency and responsibility for this ‘new’ resource, but up to today the committees remain very informal, without a proper framework, and their success depends heavily on the influence and motivation of their members, and the current state of the water infrastructure. In areas with functioning water points, the committees worked well in that there were no reported cases of broken pipelines and the functionality of the water points was guaranteed, e.g. in Chepungus where the members of the committee were well respected and their actions were coordinated. On the other hand, there were few water supply problems in Chepungus before the committees and several elders in the area had links with or were employed by the GDC. Therefore, the actual effectiveness of the water point committees themselves remains questionable. In other drier areas, the committees almost eroded shortly after their establishment due to lack of maintenance of the pipelines and persistent water shortages. When the CWPs remain empty, there is not much work for the committee except reporting breakages, if any, and waiting for maintenance. In these areas, the long maintenance times, the lack of incentives and the erosion of community-company relation, left many committee members demotivated and disillusioned. This, in turn, led to committees becoming dysfunctional, if they had not already been disbanded. The success of a committee seemed to be dependent on the state of the water infrastructure, not only currently, but also over the course of the last years. If relations between the GDC and a community had eroded due to past problems, the committees were unlikely to succeed, so that neither side would benefit.

The establishment of the committees did not considerably change the way people used the infrastructure, except for the increased attention to deliberate destruction of pipelines. Committee members were in most cases opinion leaders, i.e. vocal members of the community who were well respected, and often responsible for oversight as casual workers in the construction of water points before the committees were established. Therefore, the distribution of roles along the infrastructure in terms of their supervision did not necessarily change, but diversified with the inclusion of women and youth. While previous employment as supervisors was associated with payments, committee membership is not rewarded with an allowance. Many members took up their mandate out of a sense of responsibility and in hope of ensuring the continued functioning of the water source. Even though the incentives for the committees and the communities are rather low, the committees offer a direct opportunity to participate in the infrastructures, even if only for a few (s)elected. In addition to oversight, the committees monitor the flow of water into the purification tanks and raise awareness on water infrastructure issues but also mediate between the communities and the GDC on other issues that arise. For now, the committees remain informal, and are shaped by people who already enjoy respect in the communities, e.g. established elders. But in a way, the committees are taking on a role that was normally reserved to the elders. And while elders retain much influence in and outside of the committees, it remains to be seen whether the participation of women and youth will challenge this status quo.

Conclusion

The ruination of the GDCs water infrastructure is taking place at different levels with overlapping and interdependent effects. First, it can be observed that project delays, long construction periods, and difficult maintenance work have already resulted in parts of the new infrastructure lying fallow, as was the case with pipelines and water points (especially in Mt. Silali area). While the GDC had no plans to commission these parts of the pipeline network before the drilling at Mt. Silali, the construction site in its materiality became the focus of attention. It was even more prominent, because of its central role in the hopes and expectations of the communities. This was reinforced by the fact that the infrastructure was prominently promoted by the GDC and intensively negotiated with the communities over long periods of time. The fallow pipelines and water points were constant reminders of the promise of water that had yet to be delivered. But even where water was already pumped through the pipelines and reached the water points, there was an inevitable, but predictable ruination of the infrastructure. Long construction times, high pressure, destruction, material failure, inconvenient placement of the pipelines, and protracted and sometimes neglected maintenance all led to a condition of ruination.

This condition did not hinder the main drilling activity of the GDC, but certainly played a role in the reduced functionality of some water points. In an attempt to counteract this ruination, the GDC and the communities repeatedly negotiated for the proper use and maintenance of this infrastructure, with limited success, as the GDCs unfulfilled promises were held against it. Water infrastructure was a prominent issue in the initial negotiations between the GDC and the communities, and it remains a focus of attention due to its importance and varying state and functionality. Water as one of the most important resources for the communities became and remained the constant topic of public meetings and negotiations, and in many cases with it the non-functionality of the infrastructure itself. Repeated promises regarding the provision of water and the accompanying frustration led to several acts of ruination, i.e. the condition of ruination led to further acts of ruination. The main reason for the deliberate destruction was certainly a convenient way to get water, but in some cases, it was clearly a protest against the state of the infrastructure and the GDC.

Water infrastructure, functioning or not, had quickly become a new central point not only in negotiations, but also in the daily life of communities. At times when the water points were not working, the leakages created new meeting places for all parts of the communities. Instead of walking to fetch water from the lake during the day, women could now spend more time at water points close to homesteads. While the herders usually moved away from the area to water their livestock, many of them now stayed and shared the new water source with the women and the children. And although the Pokot around Mt. Paka remain highly mobile and far away from a sole sedentary future imagined by officials, the leakages and the functioning water points compressed social activities around them.

But due to the state of water infrastructure, reappropriation of an infrastructure that in many cases did not meet expectations led to several emerging processes. Not only engineers, but also people who live with the infrastructure are able to create new practices based on the (non-)functionality of the infrastructure. Reappropriating leakages has become a way for many to make the infrastructure work for them and benefit from it. On the other hand, destruction as a protest shows that the condition of ruination does not only allow for generative processes, but also can very well lead to destructive processes, i.e. further ruination. Here, the act of ruination has become a political instrument to address certain deficits and also to force the GDC to the negotiation table.

The abandonment of stores showed how closely infrastructure and the socio-economic sphere are intertwined. The ruination of water infrastructure without the possibility of repair or reappropriation (as in the case of Adomeyon), could lead to the ruination of shops. On the other hand, leakages triggered various generative and transformative processes. Not all of these are caused by ruination, but ruination plays a major role in making these processes possible or necessary. The fact that these processes were necessary to ensure the (future) functionality of the infrastructure shows exactly how infrastructure is shaped by social relations (and vice versa). Although ruination processes are inherent to infrastructure, they do not necessarily inhibit the transformative quality of infrastructure. They can lead to further ruination, but they can also be the basis for emerging generative processes.

In many cases, ruination has been an important transformative driver. The negotiation dynamics in Tiaty East was mainly shaped by one or another engagement with the promised infrastructure and its ruination. What amounted to ruination of water infrastructure for the GDC has led to several generative and transformative processes for the communities. At the same time, the ruination allowed communities to (re-)negotiate the functionality and use of the water infrastructure. The ruination of the pipelines directly linked promises, expectations, and hopes of the past to this physical infrastructure and to its future materiality. Local expectations are therefore strongly intertwined with the state of the infrastructure, its functionality and accessibility, and the lack of maintenance can lead to further unintended changes, consequences, and opportunities. Infrastructuring is an interplay of various processes of ruination, reappropriation, and maintenance, the framework of which is negotiated between the GDC and the communities. Whether an infrastructure can deliver what it promises therefore depends on how and whether such processes of ruination are managed (e.g. through successful maintenance, retrofitting, or reconfiguration) and whether generative and transformative processes can be sustained in a long-term perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Interview, GDC watchman, Paka, 3 January 2019.

2 Stoler, Imperial Debris, 11.

3 Howe et al., “Paradoxical Infrastructures”; Stoler, Imperial Debris.

4 Stoler, Imperial Debris, 14.

5 De Jong and Valente-Quinn, “Infrastructures of Utopia”, 333f.

6 Ruined or incomplete infrastructure does not have to reflect its functionality. For an account of different spectres of “incomplete” infrastructure, see: Guma, “Incompleteness of Urban Infrastructures.”

7 Howe et al., “Paradoxical Infrastructures”, 6.; Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure”, 382.

8 Howe et al., “Paradoxical Infrastructures”, 4.

9 de Jong and Valente-Quinn, “Infrastructures of Utopia.”, 333f.

10 Stoler, Imperial Debris, 11.

11 Appel, Anand and Gupta, “Promise of Infrastructure.”

12 For another account of how infrastructure in Kenya can disrupt everyday life, see: Lesutis, “Disquieting Ambivalence.”

13 See: Harvey, “Cementing Relations”; Anand, “Municipal Disconnect.”; Harvey, “Containment and Disruption.”; Harvey, Jensen and Morita, “Infrastructural Complications”; Jensen, “Infrastructural Fractals.”

14 Officially, most parts of Mt. Silali are in Turkana County and only the southern slopes extend into Tiaty East, but the use of land and the legitimacy of this boundary are highly contested.

15 Greiner, Greven and Klagge, “Roads to Change,” 1065.

16 Basakula et al., “Spatial-temporal Analysis of Land-use”; Vehrs and Heller, “Fauna, Fire and Farming.”

17 Greiner, Alvarez and Becker, “From Cattle to Corn,” 1480–83.

18 Republic of Kenya, “Kenya Census.”

19 The two sub-counties Tiaty East and Tiaty West cover the area formerly known as East Pokot District. After the 2010 Constitution of Kenya devolved power from the National Government to newly formed County Governments, East Pokot District became part of Baringo County and was divided into Tiaty East Sub-County and East Pokot Sub-County. In July 2020, East Pokot Sub-County was renamed Tiaty West Sub-County to avoid confusion. Nevertheless, literature published on this area before the constitutional change (and afterwards) often refers to it as East Pokot District. The highlighted area in shows the boundaries of East Pokot District, with the North-South highway essentially forming the western border of Tiaty East.

20 Bollig, Risk Management., 20f.; Oesterle, “Innovation und Transformation,” 44.

21 Oesterle, “Innovation und Transformation.”

22 Bollig, Risk Management; Republic of Kenya, “Baringo Development Plan 1974–1978.”

23 UNESCO, “Rural Press Extension Project.”

24 Republic of Kenya, “Baringo Development Plan 1997–2001.”

25 Greiner, Greven and Klagge., “Roads to Change.”

26 Government of Kenya, “Kenya Vision 2030.”

27 GDC, “Menengai Project”; Klagge et al., “Cross-Scale Linkages”; Schade, “Kenya Olkaria IV Study.”

28 Greiner, “Negotiating Access”; Lind et al., “Land, Investments and Politics”; Mosley and Watson, “Frontier Transformations.”

29 The process of geothermal development has different phases: (1) exploration, (2) appraisal, (3) steam field development, (4) power plant production, and (5) resource utilization (see: Bw’Obuya, “Impact of Geothermal Energy,” 15).

30 The overall potential of the Baringo-Silali block is estimated at 3000 MW.

31 GDC, “Baringo-Silali Project”; Klagge et al., “Cross-Scale Linkages,” 216.

32 The KfW is a German state-owned investment and development bank.

33 Interview, GDC supplier, Kambi ya Samaki, 05 January 2019.

34 Interviews, DCC for Tiaty East, 20 December 2018; Assistant Chief of Paka, 11 January 2019; Chief of Paka, 18 January 2019; County Commissioner of Baringo, 12 March 2019.

35 Ibid.

36 Republic of Kenya, “Kenya Gazette No. 29”.

37 Interview, women, Chepungus, 12 February 2020.

38 Interview, elder, Chepungus, 8 January 2019.

39 Several leakages had proven to be reliable in daily utilization, often depending on their location and pressure load.

40 Interview, shop owner, Adomeyon, 11 January 2019.

41 Interview, shop owner, Adomeyon, 14 January 2019.

42 Elder at baraza, Adomeyon, 22 February 2019.

43 Interview, teacher, Adomeyon, 11 January 2019.

44 Elder at baraza, Adomeyon, 22 February 2019.

45 Interview, Mt. Korossi, 06 March 2019.

46 The land issue remains complicated as the area is generally considered as communal land by most actors, but under the new Community Land Act (2016) (see: Alden Wily, “The Community Land Act.”), which has yet to be fully implemented, the land remains under County trust until it is officially registered as communal land with the National Land Commission. The process of registration is progressing slowly and remains unfinished by the end of 2020, although the issue is crucial for dealing with compensation claims.

47 The construction and maintenance were carried out by contractors, who handed over all responsibilities to the GDC after the end of their contract, which increased the maintenance burden.

48 Interview, Water Point Committee, Kadingding, 21 March 2019.

Bibliography

- Alden Wily, Liz. “The Community Land Act in Kenya Opportunities and Challenges for Communities.” Land 7, no. 1 (2018): 12. doi:10.3390/land7010012.

- Anand, Nikhil. “Municipal Disconnect: On Abject Water and Its Urban Infrastructures.” Ethnography 13, no. 4 (2012): 487–509. doi:10.1177/1466138111435743.

- Appel, Hannah, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta. “Introduction: Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure.” In The Promise of Infrastructure, edited by Nikhil Anand, Akhil Gupta, and Hannah Appel, 1–38. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

- Basakula, Amit K., Hauke P. Vehrs, Michael Bollig, Clemens Greiner and Frank Thonfeld. “Spatial-temporal Analysis of Land-Use and Land-cover Change in East Pokot, Kenya.” Documentation, Bonn: ZFL, 2019. doi:10.5880/TRR228DB.2

- Bollig, Michael. Risk Management in a Hazardous Environment: A Comparative Study of Two Pastoral Societies. Boston: Springer, 2006.

- Bw’Obuya, Nicholas M. The Socio-Economic and Environmental Impact of Geothermal Energy on the Rural Poor in Kenya. The Impact of a Geothermal Power Plant on a Poor Rural Community in Kenya. Nairobi: AFREPREN, 2020.

- de Jong, Ferdinand, and Brian Valente-Quinn. “Infrastructures of Utopia: Ruination and Regeneration of the African Future.” Africa 88, no. 2 (2018): 332–351. doi:10.1017/s0001972017000948.

- DIVA-GIS. “Free Spatial Data.” Accessed October 7, 2020. http://www.diva-gis.org/gdata.

- Geothermal Development Company. “Baringo-Silali Project.” 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.gdc.co.ke/baringo.php.

- Geothermal Development Company. “Menengai Project.” 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.gdc.co.ke/menengai.php.

- Government of Kenya. “Increasing Electricity Availability Through Power Generation.” Accessed February 12, 2021. http://vision2030.go.ke/project/development-of-geothermal-in-olkaria-menengai-and-silali-bogoria/.

- Greiner, Clemens. “Negotiating Access to Land & Resources at the Geothermal Frontier in Baringo, Kenya.” In Land, Investment & Politics: Reconfiguring Eastern Africa’s Pastoral Drylands, edited by Jeremy Lind, Doris Okenwa, and Ian Scoones, 101–109. Woodbrigde: James Currey, 2020.

- Greiner, Clemens, Miguel Alvarez, and Mathias Becker. “From Cattle to Corn: Attributes of Emerging Farming Systems of Former Pastoral Nomads in East Pokot, Kenya.” Society & Natural Resources 26, no. 12 (2013): 1478–1490. doi:10.1080/08941920.2013.791901.

- Greiner, Clemens, David Greven, and Britta Klagge. “Roads to Change: Livelihoods, Land Disputes, and Anticipation of Future Developments in Rural Kenya.” The European Journal of Development Research (2021. doi:10.1057/s41287-021-00396-y.

- Guma, P. K. “Incompleteness of Urban Infrastructures in Transition: Scenarios from the Mobile age in Nairobi.” Social Studies of Science 50, no. 5 (2020): 728–750. doi:10.1177/0306312720927088.

- Harvey, Penelope. “Cementing Relations: The Materiality of Roads and Public Spaces in Provincial Peru.” Social Analysis 54, no. 2 (2010): 28–46. doi:10.3167/sa.2010.540203.

- Harvey, Penelope. “Containment and Disruption: The Illicit Economies of Infrastructural Investment.” In Infrastructures and Social Complexity: A Companion, edited by Penelope Harvey, Casper Jensen, and Atsuro Morita, 51–63. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Harvey, Penelope, Casper Jensen, and Atsuro Morita. “Introduction. Infrastructural Complications.” In Infrastructures and Social Complexity. A Companion, edited by Penelope Harvey, Casper Jensen, and Atsuro Morita, 1–22. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Howe, Cymene, et al. “Paradoxical Infrastructures: Ruins, Retrofit, and Risk.” Science, Technology, & Human Values (2015): 1–19. doi:10.1177/0162243915620017.

- Jensen, Casper. “Infrastructural Fractals: Revisiting the Micro-Macro Distinction in Social Theory.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 25, no. 5 (2007): 832–850. doi:10.1068/d420t.

- Klagge, Britta, Clemens Greiner, David Greven, and Chigozie Nweke-Eze. “Cross-Scale Linkages of Centralized Electricity Generation: Geothermal Development and Investor- Community Relations in Kenya.” Politics and Governance 8, no. 3 (2020): 211–222. doi:10.17645/pag.v8i3.2981.

- Lesutis, Gediminas. “Disquieting Ambivalence of Mega-Infrastructures: Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway as Spectacle and Ruination.” Society and Space 40, no. 5 (2022): 941–960. doi:10.1177/02637758221125475.

- Lind, Jeremy, Doris Okenwa, and Ian Scoones. Land, Investments & Politics: Reconfiguring Africa’s Pastoral Drylands. Woodbridge: James Currey, 2020.

- MapCruzin. “Free GIS Shapefiles, Software, Resources and Geography Maps.” Accessed October 21, 2020. https://mapcruzin.com/.

- Mosley, Jason, and Elizabeth E. Watson. “Frontier Transformations: Development Visions, Spaces and Processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 10, no. 3 (2016): 452–475. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1266199.

- Oesterle, Matthias. Innovation und Transformation bei den Pastoralnomadischen Pokot (East Pokot, Kenia).” PhD diss., University of Cologne, 2007.

- QGIS Geographic Information System. “Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project.” 2020.

- Republic of Kenya. “Baringo District Development Plan 1974–1978.” 1975.

- Republic of Kenya. “Baringo District Development Plan 1997–2001.” 1998.

- Republic of Kenya. “2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census, Vol. 4: Distribution of Population by Socio-Economic Characteristics.” 2019. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://www.knbs.or.ke/?wpdmpro = 2019-kenya-population-and-housing-census-volume-iv-distribution-of-population-by-socio-economic-characteristics.

- Republic of Kenya. “Kenya Gazette Supplement No. 29 (Acts No. 1).” Nairobi, 2019. Accessed March 24, 2021. https://kplc.co.ke/img/full/o8wccHsFPaZ3_ENERGY%20ACT%202019.pdf.

- Schade, Jeanette. “Kenya, Olkaria IV’ Case Study Report: Human Rights Analysis of the Resettlement Process.” COMCAD Working Papers, no. 151, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2021. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/51409.

- Star, Susan L. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999): 377–391. doi:10.1177/00027649921955326.

- Stoler, Ann L. Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

- UNESCO. “Kenya Rural Press Extension Project. District Cultural and Socio-Economic Profiles: Baringo District.” 1987.

- Vehrs, Hauke P., and Gereon R. Heller. “Fauna, Fire, and Farming: Landscape Formation Over the Past 200 Years in Pastoral East Pokot, Kenya.” Human Ecology 45, no. 5 (2017): 613–625.