ABSTRACT

President Edgar Lungu and the Patriotic Front used a range of incumbency advantages to tilt the playing field in their favour in the run-up to Zambia’s 2021 elections and, as a result, were more visible offline than the opposition United Party for National Development (UPND) and its flagbearer, Hakainde Hichilema. In this paper, we draw on an original survey of party officials and activists and semi-structured interviews to consider the role of social media in the UPND’s victory. We show how the two dominant political parties invested heavily in social media, but how the UPND’s online messaging proved more persuasive and spread offline, and how social media facilitated the UPND’s political mobilisation and vote protection efforts in the face of a highly uneven playing field. Social media thus played an important role in unseating the incumbent, but not because the election was won online, or because social media provided a uniquely “social” form of communication. Instead, social media helped to facilitate the flow of information across a heavily controlled media ecosystem in which face-to-face communication remained key. In making this argument, we highlight the significant impact of social media on users and non-users alike, even in a context of relatively low internet penetration.

Incumbent parties and presidential candidates have important electoral advantages – from the institutional powers that they enjoy and resources that they control to the security and development that they can claim, promise or withdraw.Footnote1 Social media has also become a prominent part of electoral campaigns, as political parties and candidates globally invest in online advertising and social media “armies” to mobilise support and attack opponents;Footnote2 as electoral commissions and civil society organisations educate voters;Footnote3 and as citizens increasingly access, share and discuss political news through online platforms.Footnote4 This reality has motivated a growing literature on social media and elections, which – despite divergent conclusions as to social media’s effects – tends to share two conclusions.Footnote5 First, that social media’s main power – for good or bad – is through its “social” nature and the online public discussions that it enables or public sphere that it produces. Second, that the impact of social media is likely to be relatively insignificant in countries with low social media user rates, with a clear digital divide emerging between those who are and are not online.

Zambia’s 2021 election provides an excellent case study to engage with these debates. A majority of Zambians are – unlike global averages – not online. According to the 2020 Afrobarometer survey, 56% of Zambians never access the internet. That number increases to 63% for those aged 60 + and to 74% for rural respondents, and only falls to 46% for 18–25 year olds and 35% for urban respondents.Footnote6 Even those who are online often have limited access due to their reliance on someone else’s device, poor connection, costs of power and data, and use of social media bundles that limit many to a “walled garden” experience (or to a handful of social media platforms).Footnote7 Candidates and political parties nevertheless invested much time and money in social media ahead of Zambia’s 2021 elections as they developed online content and organised communications teams to share their messages and attack their opponents. Given this context, it is tempting to assume that social media’s reach is largely limited to young and urban citizens, and that politicians’ countrywide investment was due to a fetishisation of technology. Certainly, this was an argument made by the Patriotic Front (PF), Zambia’s ruling party from 2011 to 2021, as they sought to dismiss their main opponent, the United Party for National Development (UPND), and its flagbearer, Hakainde Hichilema, as online entities. This argument gained some credence from the fact that, while President Edgar Lungu and the PF were visible across the country – through a sea of green posters, billboards and party regalia, extensive coverage by traditional media, and an ability to hold public meetings despite a COVID-19 ban on rallies – Hichilema and the UPND were largely invisible in these everyday spaces.Footnote8

The UPND’s impressive electoral victory with 59% of the popular vote in the presidential election and a parliamentary majority thus raises an important question about the role of social media, which we seek to answer. To do so, we focus on the two main parties – the PF and UPND – and draw upon 21 interviews with party officials, activists, journalists, civil society workers and academics conducted between July 2021 and March 2022 via WhatsApp; two rounds of the Afrobarometer surveys (2017 and 2020); and a Qualtrics application phone survey of 318 party officials and activists that a research team shared with participants via WhatsApp a month before the election. In this party actor survey, we posed questions about the role and use of social media. The team checked that participants were actively involved in the electoral campaigns before sending them a personalised link; with participants sent 110 Kwacha (about GBP 4) of phone credit on completion to thank them for their time. Interestingly, while ruling party members seemed more suspicious of our research during interviews, and our research team had better contacts with the UPND, significantly more PF activists (204) completed the survey than UPND (98).Footnote9 The most likely explanation is that UPND activists were more suspicious of a faceless survey than of a researcher in an interview. Respondents were mixed in terms of whether they had a formal (124) or informal (193) party position, the level at which they worked (national, constituency, ward, and polling station), how long they had been actively involved in their party, and educational status. In line with the underrepresentation of women in ‘political party leaderships and structures’Footnote10 and Zambia’s youthful population, the survey was completed by more men (220) than women (98), and more youth – 116 respondents were aged 18–24, 121 were 25–30, 51 were 31–40, 21 were 41–50, and only nine were 51 plus. Due to the networks of the research team, the survey was skewed towards respondents in Lusaka (154) with relatively few respondents in Central (22), Copperbelt (53), Eastern (15), Luapula (9), Muchinga (29), North-Western (2), Northern (19), Southern (8) and Western (7) provinces. Given these biases, all data is weighted in terms of political affiliation and inferences are drawn through a triangulation with secondary literature and interviews.

We start the paper with an overview of the 2021 elections and key factors cited as having contributed to the UPND’s success before turning to social media use by Zambians, and the UPND and PF. The paper then examines how the rise of social media facilitated the UPND’s victory. First, we outline how the UPND’s online messaging tended to resonate more with social media users and helped Hichilema to appear as an electorally viable alternative. Social media demographics no doubt proved relevant as youth and urban voters, who are disproportionately active on social media, clearly contributed to UPND gains.Footnote11

Second, we show how this messaging – and its popular discussion and reception – spilled over into offline discussions due to social media’s embeddedness in a complex media ecosystem, which also includes traditional and pavement media. The latter term is inspired by Stephen Ellis’s idea of pavement radio, or the ‘popular and unofficial discussion of current affairs’ that takes place in marketplaces, places of worship, bars and the like,Footnote12 which we have extended to include non-conversational and visual traditions of gossip, rumour, and storytelling, such as sermons, posters, and street theatre.Footnote13 Finally, we show how social media – and particularly closed WhatsApp groups – helped both parties to discuss messaging and better organise their offline activities. This again proved particularly important for the UPND in the face of a ban on campaign rallies and a highly uneven playing field.

We argue that social media played a critical role in the UPND’s electoral success, but not because social media helped even the playing field, or because it created a Habermasian public sphere in which society is engaged in critical public debate, or because the elections were won online. Lungu and the PF abused their position to try and control online content. The Zambian election thus provides further evidence of how opposition victories in competitive authoritarian regimes are, in large part, a question ‘of whether the opposition … [is] ready to defeat them’Footnote14 and, we would add, voters are ready to reject them – with large opposition victories difficult for incumbents to ignore in countries such as Zambia with a large foreign debt, vocal civil society, well-organised election observation missions, and historically non-interventionist military.Footnote15 The rise of social media in Zambia also did not create a Habermasian public sphere: online political discussions were heavily policed, featured ‘divisive rhetoric ranging from personal insults to outright tribalism and hate speech’,Footnote16 were mired by harassment and cyber-bullying of women,Footnote17 rarely involved substantive conversations about needs and policies, and often focused on, or were dominated by, elites;Footnote18 a majority of Zambians were also never online.

Instead, social media’s role in Zambia’s 2021 elections stemmed from the way that it facilitated the spread of information about the political and socio-economic context and the PF and UPND and their relative popularity to social media users and non-users alike across a heavily controlled media ecosystem in which face-to-face communication remained key. In making this argument we recognise that the PF and UPND are not homogenous entities and that there were important differences in organisational capabilities enjoyed, and strategies adopted by, presidential campaign teams and lower-level candidates across the country.Footnote19 However, given limited space we focus on broad and common trends. The implication for incumbency advantage in hybrid regimes is that social media is not inherently pro- or anti-incumbent, but that it can help with opposition communications and organisation. The contribution to social media studies more broadly is that social media is not uniquely “social”, and that its power lies in its facilitation of information flow across, and organisation within, on- and offline spaces. An important implication is that there is no inherent digital divide between social media users and non-users, with social media’s reach dependent on both user rates and the broader media ecosystem.

The rise of the UPND and fall of the PF

There are many similarities between Zambia’s 2021 elections in which Hichilema and the UPND won a landslide victory, and the 2016 elections in which Lungu and the PF won by a narrow and disputed margin. Both elections constituted a two-horse race that pitted Lungu and the PF against Hichilema and the UPND. Both elections were characterised by state control of much of the traditional media and a restricted political sphere, and by ruling party intimidation and harassment of the opposition.Footnote20 In both elections, PF campaigns focused on government achievements, targeted assistance, and Lungu’s religiosity, and demonised Hichilema as a power-hungry, elitist, tribal Satanist.Footnote21 The UPND in turn welcomed PF defectors and countered attacks on Hichilema by presenting him as peaceful, approachable and inclusive, and as a reliable pair of hands who – as an economist – could “fix” Zambia. At the same time, the UPND placed the blame for economic decline, poor governance, and violence on the PF.Footnote22 In both elections, state harassment, party cadre violence and handouts led the UPND to adopt a “watermelon” strategy whereby Zambians were encouraged to be green on the outside and wear the PF's campaign regalia and pocket PF handouts but to vote for the red party – the UPND.Footnote23

Yet, there were also important differences. By 2021, Zambia’s economic crisis had deepened significantly, the government had become even more authoritarian, and traditional media coverage had become even more biased towards the PF. The latter was facilitated by the closure of independent media outlets (including the country’s most popular newspaper, The Post, in 2016 and Prime TV in 2020), which further concentrated coverage in the hands of state-owned corporations, and by increased intimidation of media houses and journalists.Footnote24 The consequences should not be underestimated. During the last month of the campaigns, the most-watched TV channel, ZNBC TV1, ‘allocated 86% of its news coverage to the President, the PF and the government’, while ‘the UPND received only 6% of news coverage and was featured negatively’. Similar biases were evident in print and private traditional media.Footnote25

Moreover, while Lungu and Hichilema had criss-crossed Zambia to attend rallies in 2016,Footnote26 and then advertised the same on social media,Footnote27 their ability to physically mobilise a crowd diverged in 2021. Citing the COVID-19 pandemic, the electoral commission banned campaign rallies on 3 June and roadshows on 15 June. Strategies of ‘legal autocratisation’Footnote28 – such as helicopter licences – were then used to further curtail UPND movements. In contrast, the PF was able to use “inspections” of development projects and other government work to hold rally-like meetings. The UPND also placed fewer posters and billboards across the country in the knowledge that activists would be harassed, and adverts would be pulled down or defaced. Thus, while the PF had at least 208 billboards in Lusaka in May 2021, the UPND had 24.Footnote29 As a result, while both parties held mask-distribution exercises, which were then streamed live on Facebook,Footnote30 the UPND was far less visible in physical spaces than it had been in 2016 and the PF.

Ordinary Zambians were also much more cautious in who they discussed politics with, as evidenced by the much larger number of respondents who ‘declined to declare who they would vote for’ in pre-election surveys.Footnote31 The overall context was thus one in which the PF enjoyed greater benefits of incumbency. So, what explains a UPND landslide? Existing analyses point to four key factors.Footnote32

First, not only had the economy and social service delivery declined, and cost of living increased, between 2016 and 2021, but there was growing frustration with the same and a deepening sense that the government was to blame. There was also anxiety that the economy would decline even further with fears surrounding debt repayments and likely impact on social service delivery and possible foreign takeovers of state companies.Footnote33

Second, the UPND had become stronger and more strategic, while the PF had become weaker and more divided. In addition to welcoming PF defectors and forging new alliances, the UPND conducted a more concerted door-to-door campaign, sought to expand its base beyond traditional strongholds, and invested more in vote protection. These activities helped the UPND to appear as more viable and inclusive, and to weaken PF arguments that it was a party of, and for, ethnic Tonga. The UPND also improved its defence of Hichilema: distancing him from the tag of an aloof economist or ‘calculator boy’ by cultivating the idea of him as “Bally” – a friendly father figure who looks out for his family – and approachable ‘cattle boy’ made good,Footnote34 and by making greater efforts to display his Christianity.Footnote35

At the same time, PF policies and messaging, and Lungu’s choice of an unpopular and co-ethnic Bemba running mate and break with tribal balancing in government appointments,Footnote36 backfired. The PF increasingly came across as economically disastrous, authoritarian, elitist, arrogant, ethnically biased, and violent, and as facing one principal opponent, which, by implication, was the alternative. The PF’s focus on large infrastructure projects and economic empowerment programmes also did little to persuade voters focused on jobs and the cost of living, who often saw government schemes as a handout intended to buy, rather than help, them.Footnote37

This frustration with the PF and momentum around the UPND also encouraged many to volunteer their time (either for free or for a small stipend) to campaign for, and/or to protect, the UPND’s vote. It also encouraged more Zambians to come out to vote with turnout rising from 57% in 2016 to 71% in 2021. Moreover, while people had feared that a new electoral register was biased in the PF’s favour,Footnote38 it was Hichilema and the UPND who seem to have benefited most from first-time voters. Certainly, while Lungu secured 9,903 more votes, leading his overall share of valid votes to drop by 11.61%, Hichilema secured 1,092,001 more votes and increased his vote share by 11.39%.Footnote39

Third, while growing authoritarianism and reduced donor funding had weakened civil society, a vocal group of governance and religious leaders and popular musicians raised awareness of economic and governance issues and helped to guard against possible abuses – for example, by ensuring, together with UPND agents and international observers, that the vote and count were closely monitored.Footnote40

Finally, peaceful electoral transfers of power in 1991 and 2011, together with the military’s track-record of non-interference, encouraged a sense that the UPND could win, which encouraged a high turnout and ensured that the UPND’s victory was sufficiently large to be impossible for the PF to somehow ignore.Footnote41 Given these factors, the question is whether social media’s rise merely correlated with or contributed in any way to the UPND’s electoral success?

Social media use by citizens and parties

Most people who use social media do so through their mobile phones,Footnote42 and Zambians are no different. However, while 77.5% of Zambians in 2020 owned a mobile phone, and another 7.6% had someone in their household who owned one, only 36.8% had one with internet access.Footnote43 Moreover, given connection problems, the costs of buying data and charging phones, and fact that not everyone wants to spend time online, regular internet usage was lower than smart phone ownership. 21% of Zambians in 2020 used the internet every day, 12% a few times a week, 4.8 a few times a month, and 5.2 less than once a month.Footnote44 The fact that overall internet usage – at 43% – was higher than smart phone ownership (36.8%) can be explained by people borrowing a device from a family member or friendFootnote45 and computer access.

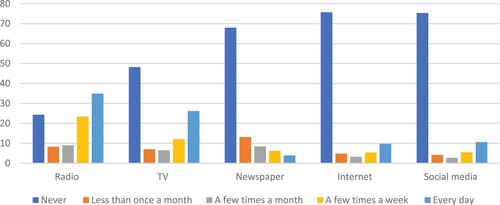

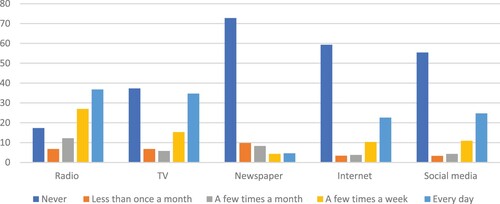

Zambia’s internet penetration and user rates are relatively low. As of January 2021, the global internet penetration rate was 59.5% and the average number of active social media users was 45%;Footnote46 the latter rising to 78% in the UK and 99% in the UAE.Footnote47 Nevertheless, they reflect a significant increase from 2.8% of Zambians enjoying access to mobile internet in 2011 and 32.3% in 2016.Footnote48 Not only were more Zambians online and using social media in 2021, but an increasing number were getting their news from these sources. Indeed, while radio and TV were still the most important news sources, social media, and the internet – the latter including both online versions of traditional media and online-only newspapers and blogs – were not far behind (see ).

The fact that more Zambians were getting news from social media and the internet did not lead to less engagement with other media. Indeed, the number of people getting news every day from the radio, TV and newspaper increased slightly between 2017 and 2020 ( and ). Traditional media houses also invested in online platforms and social media presence meaning that these spaces were complementary. An exception was newspapers – with slightly more Zambians never reading one in 2020 (72.8%) than in 2017 (68%). However, this increase might be explained by a lack of clarity as to whether reading a newspaper available in both printed and digital format online counted as getting news from “a newspaper” and/or “the internet”. It might also be due to a decline in critical commentary in legacy newspapers in the face of increased censorship and state repression,Footnote49 and a move by several prominent journalists to online-only outlets, such as the Zambian Watchdog.Footnote50

A rise in internet access and social media use encouraged increased investment in these spaces by political parties. As Wendy Willems notes, ‘While political parties did not extensively use social media in their formal campaign during the 2011 elections, they fully embraced Facebook during the 2016 elections’.Footnote51 This upward trend continued in 2021, as parties created online-only content; uploaded coverage of offline activities; employed communications officers; cultivated larger networks to produce and share content that would promote their candidate(s) and/or undermine their opponents; and used social media to strategize on, and organise, offline activities.

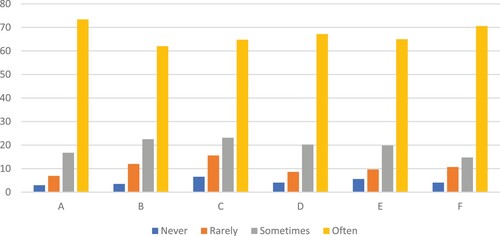

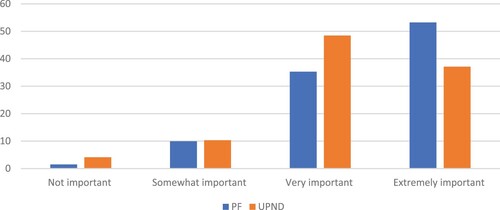

Both the PF and UPND recognised the importance of social media. Indeed, according to our party actor survey, the PF saw social media as even more critical to winning the elections than their UPND counterparts (). However, this difference might say more about perceptions of what the “other” party was doing to try and win than their own party’s activities; with UPND respondents likely concerned with the PF’s largesse and repression, and questionable independence of key state institutions.

Figure 3. How important do you think social media will be to winning the 2021 election? (Party actor survey).

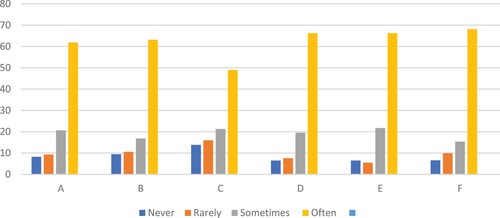

When it comes to activity type, both parties used social media in largely similar ways. This is clearly reflected in and , which show PF and UPND responses to how often they used social media to (a) communicate with party members, (b) coordinate campaign events, (c) discuss campaign strategy, (d) reach out to party’s loyal voters, (e) persuade/convince new voters, and (f) defend your party from attacks – with no significant differences found in PF and UPND responses to any of these questions.

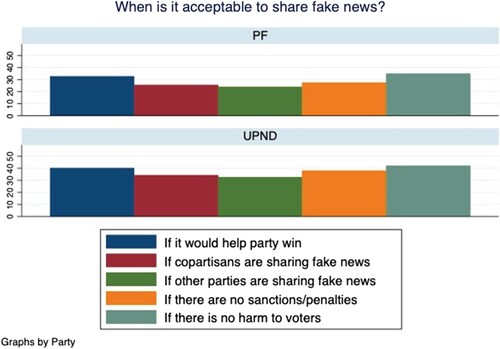

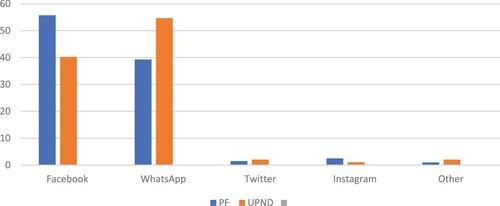

As in 2016, both parties also made much use of images of physical thingsFootnote52 – from road shows and mask distribution exercises to photos of claimed development projects and church attendance.Footnote53 Both parties tended to post things either in favour of their party or against their main opponents, and to focus more on personalities than policies, and avoided much in the way of interactive discussion with each other or the public. Citizens, as in other contexts, largely ‘campaigned at, but not with’; with online efforts tending ‘to avoid the full interactive affordances of digital media’.Footnote54 As a result, elite voices often dominated discussion.Footnote55 The consequent absence of a new Habermasian-type public sphere was further reinforced by state surveillance and repression, ethnically divisive language, and misinformation. Indeed, while the PF’s online attacks on Hichilema constituted the most blatant forms of misinformation,Footnote56 campaigners from both parties expressed similar views on the acceptability of sharing fake news (). Interviewees also admitted to sharing fake news; albeit in often very local ways, for example, to spreading rumours that a parliamentary candidate was an outsider to a constituency.Footnote57 Both parties relied largely on Facebook and WhatsApp – the most popular social media platforms in Zambia ().

Figure 7. In your work for the party, which social media platform do you use most often? (Party actor survey).

Despite these similarities, there were important differences. First, PF respondents were more reliant on Facebook, and UPND on WhatsApp (). It is clear from interviews that PF campaigners felt freer to discuss politics and to post propaganda for its candidates and against its opponents than their UPND counterparts who, in the face of a series of arrests and harassment of citizens for social media postsFootnote58 and the 2021 Cybercrimes and Cybersecurity Act, were ‘very careful of what we post’.Footnote59 In this context it is perhaps unsurprising that UPND activists relied more heavily on closed WhatsApp groups, than the ruling party.

Second, while the UPND focused more on vote protection, the PF favoured official adverts spending ‘almost five times more than the UPND on officially labelled ads on Facebook’.Footnote60 These two differences link to another: namely in the powers and resources that the parties enjoyed. The PF had the power of the state behind them and used these powers to monitor and harass people online – with at least 18 people arrested for critical Facebook posts between 2019 and 2021Footnote61 – and temporarily shut down various social media platforms on election day. The PF also used its budget to employ a larger communications team to troll and attack UPND candidates, activists, and supporters. As a result, while online spaces continued to be safer than offline spaces for UPND activists,Footnote62 both were safer for the PF.Footnote63

Other important differences can be found in the content and divergent resonance of the PF and UPND’s online messages and the ways in which social media helped to strategize on and organise offline activities. However, before moving on to these themes, it is worth noting a cross-cutting factor that played to the UPND’s advantage both on- and offline: a strong spirit of volunteerism. This spirit is reflected in the UPND’s ability to deploy agents to almost all 12,152 polling stations.Footnote64 It is also evident from interviews, in which UPND campaigners stressed the sacrifices that they had made – from the intimidation and harassment faced to their willingness to volunteer their time and resources. As interviewees explained, there was a shared desire to fight ‘for a better Zambia’Footnote65 and ‘a lot of passion, sacrifice, that a lot of us … went in [to the UPND campaign] with’.Footnote66 In contrast, PF interviewees tended to speak with less passion, while some explicitly recognised self-interest. One University student for example explained how she joined the PF campaign ‘just to earn some money for school’.Footnote67

This is not to say that all PF activists were primarily motivated by economic opportunities, or that this played no role for the UPND. Instead, it is to note that a sense of volunteering was stronger amongst UPND, than PF, activists. This is important as – together with the political and economic context – it helped to ensure that social media’s role in facilitating the discussion and spread of information and organisation of activities worked to the UPND’s advantage.

The resonance of online messaging

The PF was visible and vocal online and had a largely consistent message in the run-up to the 2021 elections: it was the ruling party and enjoyed God’s grace and was likely to win. It had overseen significant development; most notably, large infrastructure projects and economic empowerment schemes. Its leaders were generous and accessible. It was pitted against an inexperienced Hichilema who it was alleged was an elite, tribal Satanist who, among other things, supported gay rights, privatised the mines, stole land, and failed to look after his family.

However, this messaging failed to persuade a majority of voters. Discussions of development placed heavy reliance on rather dry accounts of large infrastructure projects, as exemplified by the PF’s four-hour long “virtual rallies” livestreamed on Facebook. The PF’s online image of success also sat uncomfortably with people’s lived realities of poor economic management – from inflation and underemployment to poor services – while fake news (such as claimed road projects that were in other countries) and scandals were revealed, and many citizens came to resent the arrogance displayed by PF members and to fear their future under another PF administration.Footnote68 As one academic explained:

… the content that [the] PF was posting on social media was horrendous … PF cadres would have bunches of money in their hands and bragging about [it] … but these people who are watching don’t have any money, they are struggling to put food on the table … what [the PF] … didn’t realise is that [in saying that people are ok and living well] they were not disputing UPND, they were disputing the people.Footnote69

… it was difficult to connect with these [PF] songs, even if they were brilliant songs … for the UPND, I know there is a song that had become popular, where the artist was asking civil servants … “Have you been paid?” And then the artist … would respond, “No, we've not been paid”. Footnote70

… people just wanted to get rid of the PF … [and] because the PF was comfortable with everybody else and not the UPND … that was a clear indication [to voters] to say, “If you want a difference to this, you go to the opposite of it”.Footnote71

… it also didn’t help how they were arresting [Hichilema] … Zambians are very sympathetic at such things.Footnote72

The UPND and Hichilema had also worked hard over a series of elections to establish themselves as the electorally viable alternative. The UPND’s consequent prominence helped them to draw attention to the state of the economy, poor governance, corruption, PF cadre violence and harassment, and examples of tribalism in both how the PF was ‘campaigning and … appointments … in their administration’.Footnote73 At the same time, the UPND’s acceptance of PF and Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) defectors and pre-election coalition with eight small parties, and Hichilema’s choice of a female Bemba politician as his running mate, helped to counter an image of the UPND as a Tonga party.Footnote74

The UPND also better defended themselves against the personalised attacks on Hichilema as they sought to cultivate a more accessible and likeable persona, in large part through visual imagery, which is particularly important online.Footnote75 As a member of his campaign team explained:

… we had to teach him to hold a baby … He had to demystify all this, “He’s a Satanist, he privatised your mines.” … Maybe the first … [social media post] in the morning would have bible verses … [and] whenever he’s in church, he had to close his eyes and photos had to be taken a certain way and [they then] had to be circulated.Footnote76

… over time, the fact that he … started going to church … and when he goes to church, they take pictures … and he started … writing about … some religious scriptures … that helped him lose that … anti-religion image.Footnote77

He marketed his business acumen to the middle class as evidence of his ability to get the economy back on track, while emphasizing to rural Zambians that he was just a simple “cattle boy” who had grown up poor in the countryside and worked hard for his success. With the urban poor – who had long been dependable PF voters – Hichilema traded technocratic jargon and business suits for more direct language and casual attire … To mobilize the youth, he focused on unemployment and discussed sports and popular culture on social media.Footnote78

Given the spirit of volunteerism around the UPND campaign it was not just candidates, party officials and communications teams who helped to spread these messages and counter PF propaganda. As one UPND volunteer explained, when he heard fake news about Hichilema online, he would ‘first find concrete evidence … [and then] respond and post the right information to the group’.Footnote81 Not only did the UPND use social media to discuss and strategize on messaging, but the fact that UPND activists were more reliant on WhatsApp than the PF and less reliant on official adverts, also helped to ensure that their messaging appeared as more personal in its content and delivery with messages sent to various groups, but also to individuals – with numbers collected, for example, during door-to-door canvassing.Footnote82

The UPND also benefited from the work of vocal civil society leaders and musicians, and more critical online newspapers, and their regular exposure of PF abuses and scandals.Footnote83 More generally, social media provided a space in which ordinary citizens could display their frustrations with the PF and support for the UPND in ways that helped to foster a sense that Hichilema was an electorally viable alternative. These displays were rendered particularly significant by the inability of the UPND to organise conventional performances of support through large public rallies, and helped to overcome a perennial collective action problem of whether it is rational to cast one’s individual vote.Footnote84

Such online messaging and performances seem to have had an important impact. This includes young and urban voters who are disproportionately online and whose vote contributed to the UPND’s success.Footnote85 However, what is often not considered are the ways in which online messages move across a broader media ecosystem, and how this movement can inform those without direct social media access.

The spread of information across Zambia’s media ecosystem

Literature on social media tends to focus on active users and often assumes a clear digital divide between those who are on- and offline.Footnote86 However, it is clear from interviews and comparative work that information moves between social media and other media in ways that blur such boundaries. Just as traditional media have online platforms and a strong social media presence, online discussions also influence traditional media coverage, as journalists get leads online and pick up on trending issues, or as online discussions become a story in and of themselves.Footnote87 However, while the media is often equated with traditional or legacy media that was in existence before the digital age – such as radio, television, newspapers, and magazines – and increasingly with social media platforms – such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter – and online newspapers and blogs, this is a particularly Western lens. Indeed, if we understand media as a means of mass communication then it is clear that a significant proportion of people gain their news ‘from conversations with friends and acquaintances’,Footnote88 and from other forms of popular communication, such as sermons, songs, and posters, and thus from pavement media.Footnote89

Just as the everyday discussions that constitute pavement media can move online producing a new “digital pavement radio”,Footnote90 information also moves from social to pavement media. Sometimes this movement goes via traditional media. As one civil society activist explained:

So, what happens is, just about every issue starts off on social media. So, there’ll be a comment on social media or a discussion … The very next day, all the top radio will be talking about it … and then, of course, once it’s on radio it’s offline … [it] now goes on to minibuses and people’s homes.Footnote91

This idea that campaign messages moved, often rapidly and widely, from social to pavement media was a consistent theme in interviews. As one UPND activist in Lusaka explained:

Once we put something on social media … … we are reaching people on social media and also people not on social media, because, you know, when you post something, somebody will see it … When they see it, they are going obviously to share with the people that they are with … in person, physically, yes.Footnote94

… not only those that are using these platforms or that are online [who get the information posted] but even those people that are not online because you find that people, maybe they get the information … [that “Hichilema] was saying this today”. Then they go and tell their parent, and then they’re going to tell their friends, their friends are going to tell their other relatives, just like that.Footnote95

I've seen something interesting, in sitting around, people [with a phone] start showing … [those screenshots and images] around … So, information is going informally to other people that are not even users of Facebook or Twitter.Footnote97

This reality of an interconnected media ecosystem in which information can move rapidly between on- and offline spaces, and in which face-to-face social communication remains key, is important as it meant that PF and UPND online messaging – and popular discussions and responses to the same – often moved far and wide. As, for example, Hichilema’s new nickname of Bally, the pictures of new roads supposedly built by the PF that ended up being in other countries, and potential voting patterns, were discussed in public and private spaces across the country.Footnote99

Clearly, this movement of information would not, in and of itself, have played to the UPND’s advantage. However, in a context of growing discontent with a deepening economic crisis and poor governance, offline discussions and receptions often mirrored those online as many questioned PF claims, resented PF arrogance, and came to see the UPND as an electorally viable alternative. In turn, this movement helps to explain how momentum grew around the UPND even when the party was relatively invisible in physical spaces, enjoyed far less coverage in the traditional media, and was publicly dismissed by the PF as an online entity, and when a majority of citizens were never online. This analysis highlights the ‘continued importance of physical space in political communication during elections alongside the digital’.Footnote100 This co-production also links to our final point, which is that, while campaigners often recognised the advantages of speaking with people directly and of other offline activities (such as vote protection), they also stressed how social media helped to strategize on and organise the same.

Social media and organisation offline

When discussing on- and offline campaigning many UPND interviewees were keen to emphasise the importance of the latter. As one UPND activist explained, it was ‘very difficult’ to mobilise support ‘on social media … because, you know, people will throw that back to you … and discourage others. So, it's better you have a one-on-one chat with the person … in a small group.Footnote101 Or as a UPND volunteer confirmed, ‘face-to-face is more effective … Because you sit down with somebody and convince them … But for Facebook, once you post something, there will always be somebody to criticise and mislead people’.Footnote102

The felt importance of having a captive audience – together with an inability to hold big rallies due to COVID-19 restrictions and biased traditional media coverage – fed into UPND strategy. Thus, while the PF invested heavily in billboards, posters, media adverts, t-shirts and larger meetings, the UPND chose not to invest much in posters, t-shirts and the like – lest the objects, or those distributing or wearing them, become the foci of PF attacks – and turned their attention to a more intensive door-to-door campaign and greater investment in vote protection.Footnote103 As one national-level UPND activist explained,

… if you were a party member or you’re in mobilisation or campaigning, you needed to organise meetings, meetings of 30–50 people. Or you needed to have a strategy of literally knocking on people’s doors, engaging … Your only way was to engage almost on a one-on-one or with very small groups, and, and I think that may have actually been more effective than, than we [had recognised].Footnote104

Where successfully rolled out, door-to-door campaigns were rendered possible by enthusiastic supporters and social media. Many of those involved in such efforts had regular access to social media and, if not, they were called by people who did. As one UPND coordinator in Central Province explained, 83 of the 123 people he recruited for door-to-door campaigns through a district volunteer network were on WhatsApp. He went on to explain how:

[M]ost of the messages, updates, we are getting through WhatsApp and … when you communicate you maybe find that those people that I’m communicating [with via] WhatsApp, this one is a friend to this one [who is not on WhatsApp], then they tell [them], ‘so there’s this in WhatsApp, we’re supposed to do’.Footnote105

In this way, social media – and more specifically intra-party WhatsApp groups – were used to organise local campaign efforts. These groups were also used to motivate those involved and discuss party messaging. As interviewees involved explained, people higher up in the party would share campaign materials via social media – such as the party manifesto and examples of PF’s failings and Hichilema’s promise – and local activists could also use the same groups to share local grievances and “talking points” with regional and national teams. Higher-level campaigners could also give directions to those going door-to-door on some of the do’s and don’ts of the campaigns including directives to remain peaceful and to avoid wearing party regalia. These groups were also used to source and discuss responses to common queries and misinformation. As one interviewee explained, he would ‘source information [via intra-party groups] to counter misinformation’, for example, regarding PF claims of Hichilema’s involvement in the privatisation of the mines.Footnote106

Intra-party groups were also used to organise the UPND’s vote protection – from the mobilising of volunteers to the dissemination of information on stations and duties – with a separate online application used to gather and collate final results.Footnote107 Given the level of PF repression, the UPND’s ability to place party agents in almost every polling station was a particularly impressive feat and ‘made it very difficult for the government to manipulate the vote’.Footnote108

Again, online discussions of messaging and the organisation of one-to-one or small group conversations and vote protection would not in and of itself have played to the UPND’s advantage. The PF also discussed strategy, spoke to people in smaller groups and went door-to-door and had polling station agents, and organised these activities, in large part, via social media. In addition, while many UPND activists tried to reach voters directly, it was often extremely difficult given state repression and the presence of PF party cadres who often used violence against those visibly campaigning for, or supporting, the UPND. Various strategies were adopted by the UPND to try and get around this violence – with campaigners told by the central party, for example, to say that they were a member of a well-known civil society organisation if confronted by PF supporters.Footnote109 However, the levels of violence and fear in certain areas – together with the size of the country and limited resources – ensured that door-to-door campaigns were often limited and sometimes non-existent. As one UPND activist in a PF Northern Province stronghold explained:

We’re not free, even, to wear the UPND regalia … If you wear the regalia for UPND, they can even kill you … Even the billboards, they’re just tearing them and burning them … we’re not free even door-to-door campaigning.’Footnote110

There was thus nothing inherently pro-opposition about the use of closed groups to organise offline. Instead, such organisation proved particularly useful to the UPND given the constraints on conventional campaign methods – such as rallies and posters – and extremely biased traditional media coverage. Moreover, it ultimately contributed to the UPND’s victory due to a broader context in which ordinary people were struggling and many were increasingly frustrated with the government and looking for an alternative, and because of the way that these offline campaigns were paralleled by online campaigns and less organised flows of information between on- and off-line spaces.

Conclusions

Zambia’s 2021 presidential election provides further evidence of the ambiguous and mixed impact of social media on electoral politics, as incumbents proactively tried to use and obstruct ‘social media as a tactic to maintain power and legitimacy’,Footnote112 and online platforms opened new opportunities for opposition parties. Given this ambiguity, the fact that most Zambians were never online, and the importance of face-to-face interactions and offline activities, the UPND clearly did not win the election online. Instead, their success came after years of hard work and a gradual expansion of support; was propelled by a popular sense of frustration with the ruling PF and hope that the UPND and Hichilema were an electorally viable alternative; and was helped by vocal civil society voices, extensive election monitoring, and history of electoral turnovers. The UPND’s overwhelming victory in turn rendering it near-impossible for the PF to not hand over power.

Nevertheless, the UPND’s victory was facilitated by social media in at least three important ways. First, an increasing number of Zambians are online and many check their social media feeds every day, and the UPND’s online messaging resonated with more people than the PF’s. This included many urban and young voters who were disproportionately online and who made an important contribution to the UPND’s overall tally. Social media discussions also helped to cultivate a popular perception of the PF’s diminishing, and UPND’s growing, popularity, which proved particularly important given severe constraints on the UPND’s ability to conduct conventional rally-intensive campaigns and biased traditional media coverage.

Second, this online messaging and popular debates spread offline as stories, memes and videos were discussed via traditional media, face-to-face meetings, and mobile phones. Third, social media helped with the organisation of messaging, campaigning and vote protection by party officials, lower-level candidate campaign teams, and vibrant volunteer networks in ways that helped to spread both the UPND’s message and a sense of its electoral viability, and to protect its vote.

This reality of social media being used to mobilise online and to organise offline, as well as the emergence of a complex media ecosystem that sees a constant movement of information between social, traditional and pavement media, extends to other contexts. In Ghana, for example, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and National Democratic Congress (NDC) use social media to reach out directly to voters and to strategize on and to organise their campaign efforts.Footnote113 The parties have also realised how online discussions can rapidly move offline.Footnote114 As one interviewee explained ahead of the country’s 2020 elections, ‘anytime you put something on social media … people will read, they will share, if they don’t share on social media, they share on their community gathering, they share at school, they share everywhere they go’.Footnote115 A similar picture is evident in Kenya where, as one youth leader explained, if you send a WhatsApp message, it reaches those in the groups, but it also spreads to others: ‘if I get the message, my mum and dad might not be on social media, but I spread it to them’.Footnote116

Our analysis has two broad implications for understanding incumbency advantage and the role of social media in and beyond Zambia. First, social media is neither inherently good nor bad for ruling or opposition parties. Social media’s potential rests in its informational role – including its ability to fill an informational vacuum left by constraints on physical campaigns and a biased traditional media. But social media’s impact depends on the resonance and reach of the messages shared. When an opposition party can effectively harness social media to organise and to circulate a resonant message and to minimise the impact of online controls and counter controls on physical campaigns and traditional media; ordinary people are frustrated with the incumbent government; and there are some checks on the ruling party, for example, through vocal civil society voices and non-interventionist military, elections in competitive authoritarian regimes can create an opportunity for change.

Second, despite common assumptions, social media is neither uniquely “social” nor separate from an increasingly interactive traditional media and highly social pavement media. In contexts with a vibrant traditional and/or pavement media, online discussions can move into offline discussions even in areas with relatively low internet penetration and social media user rates. This reality ensures a distinction of direct and indirect social media users, rather than of users and non-users. It also means that social media can play an important role even in contexts with relatively low internet penetration rates in which face-to-face communications remain the most effective persuader by providing informational resources and an organisational base for those interactions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Zambian research team who oversaw the “political actor survey” and helped set up interviews; namely Beverly Shicilenge (who led the team), Malumbe Shicihilenge, Kalonde Siulapwa and Edgar Miyanda. Thanks to ZERN members for insights that helped to inform the paper’s development, and to Nic Cheeseman, Justin Willis, the special issue editors, and anonymous reviewers for their excellent feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Bleck and van de Walle, Electoral Politics in Africa Since 1990.

2 Gadjanova et al., “Social Media, Cyber Batallions”.

3 Cheeseman, Lynch and Willis, The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa.

4 Nyabola, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics.

5 For example, see Christensen, “Discourses of Technology and Liberation”; Diamond, “Liberation Technologies”; Dzisah, “Social Media and Elections in Ghana”.

6 Afrobarometer, Zambia Round 8 Data.

7 Toussaint “Access granted”.

8 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”; EU EOM, Zambia 2021.

9 The remaining 15 participants were from other parties.

10 EU EOM, Zambia 2021, 37.

11 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”; Seekings, “Incumbent Disadvantage”.

12 Ellis, “Tuning in to Pavement Radio”, 321.

13 Gadjanova, Lynch and Saibu, “Misinformation Across Digital Divides”.

14 Bunce and Wolchik, “Defeating Dictators”, 47.

15 Macdonald and Molony, “Can Domestic Observers Serve as Impartial Arbiters?”; Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

16 EU EOM, Zambia 2021, 5.

17 Ibid., 37.

18 Mfula, “Thinking About a Revolution”.

19 Seekings, “Incumbent Disadvantage”.

20 Banda et al.,Democracy and Electoral Politics in Zambia; Resnick, “How Zambia’s Opposition Won”.

21 Banda et al., Democracy and Electoral Politics in Zambia; Kaunda, “Christianising Edgar Chagwa Lungu”.

22 Beardsworth, “From a ‘Regional Party’ to the Gates of State House”.

23 Goldring and Wahman, “Democracy in Reverse”, 110; Musonda, “He Who Laughs Last Laughs the Loudest”.

24 Amnesty International, Ruling by “Fear and Repression”; Sishuwa et al., “Legal Autocratisation ahead of the 2021 Zambian Elections”.

25 EU EOM, Zambia 2021, 31.

26 Beardsworth, “From a ‘Regional Party’ to the Gates of State House”.

27 Willems, “The Politics of Things”.

28 Sishuwa et al., “Legal Autocratisation Ahead of the 2021 Zambian Elections”.

29 Transparency International Zambia, Seventh 2021 Elections Project Update.

30 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”.

31 Seekings and Siachiwena, “Voting Preferences Among Zambian Voters”, 1.

32 This summary draws largely upon Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”; Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”; Resnick, “How Zambia's Opposition Won”; and other contributions to this special issue.

33 Resnick, “How Zambia's Opposition Won”.

34 Ibid.

35 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021.

36 Beardsworth and Mutuna, “Tribal Balancing”.

37 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”; Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

38 Simutanyi, “Zambia’s 2021 Elections”.

39 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”, 49.

40 Kaaba, Hinfelaar and Sawyer, “A Comparison of the Role of Domestic”; Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

41 Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

43 Afrobarometer, Zambia Round 8 Data.

44 Ibid.

45 Nyamnjoh, “Globalisation, Boundaries and Livelihoods”, 53.

47 https://www.statista.com/statistics/507405/uk-active-social-media-and-mobile-social-media-users/.

48 Willems, “The Politics of Things”, 1197.

49 Amnesty International, Ruling by “Fear and Repression”.

50 Interviews, journalists, 22 October 2021 and 26 November 2021.

51 Willems, “The Politics of Things”, 1201.

52 Willems, “The Politics of Things”.

53 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”.

54 Stromer-Galley, Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age, 2–3 (emphasis in the original).

55 Mfula, “Re-enacting Zambia’s Democracy”; Mfula, “Thinking About a Revolution”.

56 EU EOM, Zambia 2021, 34–35.

57 Interview, UPND campaigner in Central, 21 October 2021.

58 Amnesty International, Ruling by “Fear and Repression”, 17–19.

59 Interview, UPND volunteer in Lusaka, 20 July 2021.

60 EU EOM, Zambia 2021, 27.

61 Ibid., 33.

62 Willems, “Beyond Platform-Centrism and Digital Universalism”.

63 EU EOM, Zambia 2021.

64 Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

65 Interview, UPND volunteer in Lusaka, 20 July 2021

66 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021.

67 Interview, PF activist in Lusaka, 20 October 2021.

68 M'kulma, “Information Consumption Among University of Zambia Students”; Seekings, “Incumbent Disadvantage”.

69 Interview, academic, 22 October 2021.

70 Interview, musician, 17 December 2021.

71 Ibid.

72 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021.

73 Interview, UPND volunteer in Central, 21 October 2021.

74 Beardsworth, “From a ‘Regional Party’ to the Gates of State House”; Resnick, “How Zambia’s Opposition Won”.

75 Kaunda, “Christianising Edgar Chagwa Lungu”; Willems, “The Politics of Things”.

76 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021.

77 Interview, journalist, 22 October 2021.

78 Resnick, “How Zambia’s Opposition Won”, 74.

79 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021.

80 Interview, academic, 14 March 2022.

81 Interview, UPND activist, 21 July 2021.

82 Interview, UPND leader in Lusaka, 21 July 2021.

83 Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

84 Cheeseman, “How to (Not) Rig an Election”.

85 Siachiwena, “A Silent Revolution”.

86 Fuchs and Horak, “Africa and the Digital Divide”.

87 Interviews, journalists, 22 October 2021 and 26 November 2021.

88 Ellis, ‘Tuning in to Pavement Radio’, 321.

89 Gadjanova, Lynch and Saibu, “Misinformation Across Digital Divides”.

90 Mare, “Popular Communication in Africa”, 96.

91 Interview, civil society leader, 20 October 2021.

92 Ibid.

93 Afrobarometer, Zambia Round 8 Data.

94 Interview, UPND volunteer in Lusaka, 20 July 2021.

95 Interview, UPND activist in Central, 21 October 2021.

96 Ibid.

97 Interview, journalist, 22 October 2021.

98 Parks and Mukherjee, “From Platform Jumping to Self- Censorship”, 227.

99 Interview, UPND activist at the national level, 21 October 2021; Interview, academic, 14 March 2022.

100 Willems, “The Politics of Things”, 1194; emphasis in the original.

101 Interview, UPND activist in Lusaka, 21 July 2021.

102 Interview, UPND volunteer in Lusaka, 20 July 2021.

103 EU EOM, Zambia 2021.

104 Interview, 21 October 2021.

105 Interview, UPND activist in Central, 21 October 2021.

106 Interview, UPND activist in Western, 21 July 2021.

107 Interview, UPND campaigner at the national level, 21 October 2021.

108 Sishuwa and Cheeseman, “Three Lessons from Africa”.

109 Interview, UPND activist in Central, 21 October 2021.

110 Interview, constituency youth leader in Northern, 23 July 2021.

111 Interview, civil society activist, 26 November 2021.

112 Bleck and van de Walle, Electoral Politics in Africa Since 1990, 100.

113 Lynch, Gadjanova and Saibu, “WhatsApp and Political Messaging at the Periphery”.

114 Gadjanova, Lynch and Saibu, “Misinformation Across Digital Divides”.

115 Interview, NPP party activist, Nanton, Ghana, 23 July 2019.

116 Cited in Lynch, “Hybrid Rallies and a Rally-Centric Campaign”.

Bibliography

- Afrobarometer, Zambia Round 7 Data (2018) <https://www.afrobarometer.org/survey-resource/zambia-round-7-data/> .

- Afrobarometer, Zambia Round 8 Data (2022) <https://www.afrobarometer.org/survey-resource/zambia-round-8-data-2022/>.

- Amnesty International. Ruling by “Fear and Repression”: The restriction of freedom of expression, association and assembly in Zambia. (2021) <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr63/4057/2021/en/>.

- Banda, T., O. Kaaba, M. Hinfelaar & M. Ndulo, eds. Democracy and Electoral Politics in Zambia. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

- Beardsworth, N. “From a ‘Regional Party’ to the Gates of State House: The Resurgence of the UPND.” In Democracy and Electoral Politics in Zambia, edited by T. Banda, O. Kaaba, M. Hinfelaar, and M. Ndulo, 34–68. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

- Beardsworth, N., and S. K. Mutuna. “‘Tribal balancing': Exclusionary Elite Coalitions and Zambia’s 2021 Elections.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 16, no. 4 (2023): 619–642.

- Beardsworth, N., H. Siachiwena, and S. Sishuwa. “Autocratisation, Electoral Politics and the Limits of Incumbency in African Democracies.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 16, no. 4 (2023): 515–535.

- Bleck, J., and N. van de Walle. Electoral Politics in Africa Since 1990: Continuity in Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Bunce, V., and S. Wolchik. “Defeating Dictators: Electoral Change and Stability in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes.” World Politics 62, no. 1 (2010): 43–86.

- Cheeseman, N. “How to (Not) Rig an Election: Protecting Democracy through the Ballot Box”. Resistance Bureau (20 September 2022) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = _XHXer3UiTE>.

- Cheeseman, N., G. Lynch, and J. Willis. The Moral Economy of Elections in Africa: Democracy, Voting and Virtue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Christensen, C. “Discourse of Technology and Liberation: State aid to net Activists in an era of ‘Twitter Revolutions’.” The Communication Review 14, no. 3 (2011): 233–253.

- Diamond, L. “Liberation Technologies.” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 3 (2010): 69–83.

- Dzisah, W. “Social Media and Elections in Ghana: Enhancing Democratic Participation.” African Journalism Studies 39, no. 1 (2018): 27–47.

- Ellis, S. “Tuning in to Pavement Radio.” African Affairs 88, no. 352 (1989): 321–330.

- EU EOM [European Union Election Observation Mission], Zambia 2021: Final Report.

- Fuchs, C., and E. Horak. “Africa and the Digital Divide.” Telematics and Informatics 25, no. 2 (2008): 99–116.

- Gadjanova, E., G. Lynch, and G. Saibu. “Misinformation Across Digital Divides: Theory and Evidence from Northern Ghana.” African Affairs 121, no. 483 (2022): 161–195.

- Gadjanova, E., G. Lynch, J. Reifler, and G. Saibu. “Social Media, Cyber Batallions and Political Mobilization in Ghana” (2019) <https://www.elenagadjanova.com/uploads/2/1/3/8/21385412/social_media_cyber_battalions_and_political_mobilisation_in_ghana_report_final.pdf>.

- Goldring, E., and M. Wahman. “Democracy in Reverse: The 2016 General Election in Zambia.” Africa Spectrum 51, no. 3 (2016): 107–121.

- Hinfelaar, M., O. Kaaba, and M. Wahman. “Electoral Turnovers and the Disappointment of Enduring Presidential Power: Constitution Making in Zambia.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 15, no. 1 (2021): 63–84.

- Hinfelaar, M., L. Rakner, S. Sishuwa, and N. van de Walle. “Legal Autocratisation Ahead of the 2021 Zambian Elections.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 16, no. 4 (2023): 558–575.

- Kaaba, O., M. Hinfelaar, and K. Sawyer. “A Comparison of the Role of Domestic and International Election Observers in Zambia’s 2016 and 2021 General Elections.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 16, no. 4 (2023): 643–658.

- Kaunda, C. “Christianising Edgar Chagwa Lungu: The Christian Nation, Social Media Presidential Photography and 2016 Election Campaign.” Stellenbosch Theological Journal 4, no. 1 (2018): 215–245.

- Lynch, G., E. Gadjanova, and G. Saibu. “WhatsApp and Political Messaging at the Periphery: Insights from Northern Ghana.” In WhatsApp and Everyday Life in West Africa: Beyond Fake News, edited by I. Hassan, and J. Hitchen, 21–42. London: Zed Books, 2022.

- Macdonald, R., and T. Molony. “Can Domestic Observers Serve as Impartial Arbiters?: Evidence from Zambia’s 2021 Elections.” Democratization 30, no. 4 (2023): 635–653.

- Mfula, C. “Re-enacting Zambia’s Democracy Through the Practice of Journalism on Facebook.” In Democracy and Electoral Politics in Zambia, edited by T. Banda, O. Kaaba, M. Hinfelaar, and M. Ndulo, 242–282. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

- Mfula, C. “Thinking About a Revolution: Research, Social Media and Africa” (10 July 2021) <https://roape.net/2021/07/20/thinking-about-a-revolution-research-social-media-and-africa/>.

- M'kulma, A. “Information Consumption among University of Zambia Students in the Buildup to the 2021 Zambia General Elections.” Library Philosophy and Practice (2021). <https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/6294>.

- Musonda, J. “He who Laughs Last Laughs the Loudest: The 2021 Doni-Kubeba (Don’t Tell) Elections in Zambia.” Review of African Political Economy (2023. doi:10.1080/03056244.2023.2190452.

- Nothias, T. “Access Granted: Facebook’s Free Basics in Africa.” Media Culture & Society 42, no. 3 (2020): 329–348.

- Nyabola, N. Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet era is Transforming Politics in Kenya. London: Zed Books, 2018.

- Nyamnjoh, F. “Globalisation, Boundaries and Livelihoods: Perspectives on Africa.” Identity, Culture and Politics 5, no. 1&2 (2004): 37–59.

- Parks, L., and R. Mukherjee. “From Platform Jumping to Self- Censorship: Internet Freedom, Social Media, and Circumvention Practices in Zambia.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 14, no. 3 (2017): 221–237.

- Resnick, D. “How Zambia’s Opposition won.” Journal of Democracy 33, no. 1 (2022): 70–84.

- Seekings, J. “Incumbent Disadvantage in a Swing Province: Eastern Province in Zambia's 2021 General Election.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 16, no. 4 (2023): 576–599.

- Seekings, J., and H. Siachiwena. “Voting Preferences Among Zambian Voters Ahead of the August 2021 elections”. IDCPPA working paper no. 27, University of Cape Town (2021) <http://webcms.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/433/IDCPPA.WP27SeekingsSiachiwena.pdf>.

- Siachiwena, H. “A Silent Revolution: Zambia’s 2021 General Election.” Journal of African Elections 20, no. 2 (2021): 32–56.

- Simutanyi, N. “Zambia’s 2021 Elections: Unfree, Unfair, Unpredictable”. African Arguments (9 August 2021) <https://africanarguments.org/2021/08/zambia-2021-elections-unfree-unfair-unpredictable/>.

- Sishuwa, S., and N. Cheeseman. “Three Lessons from Africa from Zambia’s Landslide Opposition Victory”. African Arguments (2021) <https://africanarguments.org/2021/08/three-lessons-for-africa-from-zambia-landslide-opposition-victory/>.

- Stromer-Galley, J. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Transparency International Zambia, Seventh 2021 Elections Project Update (June 2021) <https://tizambia.org.zm/blog/2021/06/15/seventh-2021-elections-project-update/>.

- Willems, W. “’The Politics of Things’: Digital Media, Urban Space, and the Materiality of Publics.” Media, Culture & Society 41, no. 8 (2019): 1192–1209.

- Willems, W. “Beyond Platform-Centrism and Digital Universalism: The Relational Affordances of Mobile Social Media Publics.” Information, Communication & Society 24, no. 12 (2021): 1677–1693.