ABSTRACT

While historians of East Africa have examined the region’s rich print cultures in the era of decolonisation, they have viewed newspapers primarily in intellectual terms, rather than as businesses embedded in capital networks. Through the Asian-owned Tanzanian tabloid Ngurumo, this article examines the political economy of newspapers and printing during the time of decolonisation in Tanzania. It argues that Randhir Thaker’s printing firm played an essential yet overlooked role in sustaining nationalist expansion in the late 1950s, before then entering the newspaper market in a period marked by racial tensions. However, the same undercapitalised business model which allowed Ngurumo to become Tanzania’s most popular newspaper then constrained its ability to expand its operations. Ngurumo’s demise in the mid-1970s was not caused by direct government intervention, but by its lack of the infrastructural and financial support which sustained the state- and party-owned press through a time of economic hardship.

On the evening of 2 November 1965, Randhir Thaker locked up his offices in Dar es Salaam. Thaker was the owner of Ngurumo, Tanzania’s best-selling daily newspaper. Minutes later, he collapsed and died of a heart attack. At his funeral, which attracted several thousand mourners, President Julius Nyerere himself was deeply moved by the passing of a friend.Footnote1 Other Tanzanian leaders echoed his thoughts. ‘We have few men of his type and his passing leaves a large hole,’ the minister of home affairs wrote to Ngurumo.Footnote2 At a memorial gathering at the T. B. Sheth Library, another government minister urged Tanzania’s Asians to follow Thaker’s example in committing themselves to the post-colonial nation. At a time when African politicians frequently depicted Tanzania’s Asian minority as a class of parasitical exploiters, such tributes were striking. It reflected the atypical and instrumental role played by Thaker in the success of African nationalism in Tanzania, plus the widespread popularity of Ngurumo.Footnote3

This article explores the rise and fall of Ngurumo, meaning ‘Thunder’ or ‘Roar’ in Swahili. It is driven by several interconnected questions. How, in an urban society marked by racial tensions, did an Asian-owned newspaper become the ordinary African’s daily read of choice? How, in a socialist state in which the ruling Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) dominated the country’s print sphere, did an independent newspaper become so popular? Why was Ngurumo’s continued existence tolerated – even encouraged – by the party-state? And why, given its success, did it vanish in the mid-1970s?

This history of Ngurumo builds upon a growing historiography on “African print cultures,” which explores newspapers as a source of political thought during the era of decolonisation. This literature emphasises the roles of editors, journalists, and readers in print conversations which reshaped identities and public discourse. It rejects notions of the African press as being driven by a modular, anticolonial nationalism by drawing attention to the cosmopolitan voices within newspapers.Footnote4 This article pushes beyond the printed word itself, to address the circumstances which encouraged the emergence of newspapers, the conditions which sustained them, and the reasons for their demise. Following examples set by more infrastructure-minded histories of the Latin American press,Footnote5 the focus here is on relationships of patronage and political support, on the technological and financial aspects of a printing operation, and on the vulnerability of small-scale businesses in a socialist state.Footnote6

Ngurumo has attracted little attention in the literature on the Tanzanian press. At the height of its success, a researcher described Ngurumo as a ‘blotchy, bold-typeface tabloid of four pages, with a distinctive (if not distinguished) character all its own.’ He argued that Ngurumo owed its popularity to its coverage of ‘domestic quarrels, swindles, “street news”, and humour’ rather than serious news.Footnote7 Verdicts from Tanzanian media experts have been divided. One simply dismissed Ngurumo as ‘a peripheral newsreporting medium.’Footnote8 Conversely, a prominent Tanzanian journalist remembered Ngurumo as ‘the thunder that roared effectively to terrorise the colonialists in the struggle for independence.’Footnote9 An early historical sketch of the African press in colonial Tanganyika does not mention Ngurumo at all, possibly because of its Asian ownership.Footnote10 Another survey misrepresents it as the ‘journalistic voice’ of Tanzania’s Asian community.Footnote11 More helpfully, historians have used Ngurumo’s columns, cartoons, and letters pages as a window into moral debates about life in post-colonial Dar es Salaam. Moving away from the official rhetoric emanating from government or party newspapers, they use Ngurumo as part of what Emily Callaci dubs a ‘street archive’ to recover grassroots experiences of socialism.Footnote12

Breaking with the accounts of communications scholars, who alternatively dismiss or lionise Ngurumo, this article also moves beyond the recent work of cultural historians to excavate what might be called the political economy in which the newspaper functioned. As James Brennan observes with regard to colonial Tanganyika’s newspapers, the contents of the press did not simply reflect political opinion, but were ‘the product of a shifting business and patronage terrain.’Footnote13 Ngurumo’s success was due to its ability to weave attractive content with a frugal business model that made it both appealing and affordable to a growing urban readership. However, this same undercapitalised setup also proved its downfall. Ngurumo’s experience demonstrates the difficulties of private media houses – like other cultural institutions – to operate in a socialist economy, without preferential treatment or government subsidies.Footnote14

This article begins by situating the emergence of Ngurumo’s publisher, Thakers Limited, in a constellation of political and business interests in late colonial Tanganyika. Tracing lines of credit in the 1950s, it examines the formation of an unusual, informal alliance between an Asian printer and an African nationalist party. The article then analyses Ngurumo’s operation at the height of socialist state-building in Tanzania. It argues that in spite of the predominance of “street journalism” in its pages, the newspaper was engaged in the international debates at the time, while receiving vital cash transfers from carrying Cold War propaganda. The final section explains the decline and disappearance of Ngurumo in the mid-1970s. It demonstrates how the structural conditions of state socialism and Thakers’ inability to adapt to new economies of scale in a period of material deprivation, rather than political intervention per se, led to Ngurumo’s collapse.Footnote15

Origins

Printing was a common occupation among Dar es Salaam’s Asian community in the late colonial era. Under the colonnades of the old town’s streets, dozens of printers, typesetters, and stationers plied a small-scale trade in paper goods. These Indian entrepreneurs, whose modest amounts of capital enabled the purchase of rudimentary presses, were essential for the emergence of a Tanganyikan print sphere. Much of their output was in English or Indian languages such as Gujarati. But they also provided services to a small number of African clients as associational life and newssheets grew in popularity during the interwar period.Footnote16

In comparison to neighbouring Kenya, an African press emerged only slowly in Tanganyika.Footnote17 Restrictive colonial registration policies added to the high start-up costs of entering a market which had uncertain returns. The problem of undercapitalisation and reliance on expensive printworks were as great a barrier to the emergence of a robust African press as colonial censorship. Erica Fiah, editor of Tanganyika’s first African-owned newspaper, Kwetu, bought a second-hand, manually-operated Japanese press to avoid paying high charges to Asian printers. Yet this proved a slow operation and Fiah’s appeals for African contributions towards buying a modern press were unsuccessful.Footnote18 Nonetheless, by the mid-1950s, Dar es Salaam was gradually developing a vibrant newspaper culture, as an expanding reading public sought more interesting printed matter than the dry government-owned titles. Rising levels of basic literacy encouraged the growth of a more outspoken Swahili press attuned to local interests.Footnote19

Among Tanganyika’s Asian print entrepreneurs was Bhanushanker Thaker, who migrated from Gujarat to Dar es Salaam in 1930, where he set up a printing press. Bhanushanker went into business with Vrajlal Ramji Boal, who two years earlier had launched an Anglo-Gujarati newspaper, the Tanganyika Herald.Footnote20 Bhanushanker’s son, Randhir, was born in Dar es Salaam in 1921. After finishing school in Tanganyika, Randhir was sent to India in 1939. He graduated from Gujarat College in Ahmedabad in 1949 and then trained as a policeman. In 1952 or 1953, Randhir took leave to visit his family and then settled in Dar es Salaam. He declined a position in the Tanganyikan Police and instead followed his father into the printing trade. In 1953, he founded Thakers Limited, a printing and stationery firm, based on Selous Street (later Zanaki Street) in the city’s central business quarter.Footnote21

The establishment of Thakers Limited preceded by a year the transformation of the Tanganyika African Association into the more explicitly anticolonial TANU. As Brennan notes, in ‘an inversion of Benedict Anderson’s well-known argument, it was nationalism that created conditions for a new print capitalism in East Africa.’Footnote22 This meant not just newspapers, but other forms of printed matter. TANU quickly became a major client of Thakers, which printed flyers to advertise public rallies, copies of the party’s constitution, and party membership cards.Footnote23 The latter were a particularly important tool in TANU’s expansion: eager to attract new members, it concentrated on selling cards and did not press for subsequent payments.Footnote24 This meant that the rising expense of administering and promoting the party’s activities, including in terms of printing, was not matched by increased revenue from subscriptions.

The result was that TANU’s rapid growth came at considerable monetary cost. By May 1957, the party’s finances were in a parlous condition. ‘Printing expenses are a great load on the Union,’ stated a TANU report. ‘The present situation is frightening.’ TANU’s headquarters diagnosed that the problem lay in the failure of branches to pay for the printed materials distributed to them.Footnote25 Some of TANU’s creditors began legal proceedings against the party.Footnote26 But while other printers pursued their debts in court, Thaker remained flexible.Footnote27 By June 1958, TANU owed 48,000 shillings to Thakers, out of a total party debt of 77,000 shillings.Footnote28 At the party’s Tabora Conference that year, delegates agreed that ‘all TANU publications should be printed on their own press.’ Yet the indebted party lacked the capital to do so.Footnote29 In these circumstances, Thaker’s credit and his tolerant attitude towards its slow or non-repayment proved a financial lifeline for TANU.

Despite these arrears, Thaker continued to cooperate with TANU. He allowed the party to use his office as a meeting place, collected donations on its behalf, and appeared on the platform with Nyerere at a party meeting. According to colonial intelligence, he also acted as an intermediary between TANU and the Indian high commissioner in Nairobi, who tracked the emergence of the region’s nationalist movements with interest.Footnote30 In fact, Thaker deepened his financial commitments to Tanganyikan nationalism. In September 1957, Thakers printed the first issue of Mwafrika (‘The African’), a weekly newspaper published by the Tanganyika African Newspaper Company, which was closely linked to TANU.Footnote31 Mwafrika’s initial circulation of 4,000 copies per week rose to a remarkable 17,000 after eight months – but did so while the Company developed a large debt to its printers. Thaker was less sympathetic to Mwafrika than to the party. In May 1958, Thaker alleged that he was owed more than 30,000 shillings for printing the newspaper, a figure which the Company disputed.Footnote32 The Company tried to make itself independent from Thakers by obtaining its own press. But one machine donated to TANU by the Asian Socialist Conference was never put to work, while another purchased from the Kanti Printing Works proved to be worn out.Footnote33

Thaker’s engagement with Tanganyikan nationalism came at a time when the country’s Asian community was increasingly uncertain about its future and divided over political strategy. In 1951, a group of professionals established the Asian Association, which Thaker joined. The Asian Association declared itself in favour of a non-racial Tanganyika and channelled financial assistance to TANU. Other Asians supported the idea of ‘multi-racialism’ proposed by the colonial government, which was designed to protect European and Asian interests.Footnote34 TANU’s sweeping victories in Legislative Council elections in September 1958 and February 1959 brought these tensions to the boil. The Asian Association’s leadership worked with TANU in supporting a raft of candidates across three electoral lists, separated along racial lines. Thaker himself unsuccessfully tried to gain a place on the Asian Association’s slate as a pro-TANU candidate. However, as some African leaders advanced a more exclusive, racially-defined nationalism – including via the pages of Mwafrika – this formal electoral support for TANU generated apprehensions among Tanganyikan Asians. Thaker was uneasy at the behaviour of the organisation’s leadership. At a post-election meeting, he urged the Association to ensure that the Asian community ‘did not stagger behind’ as the ‘caravan’ of the independence struggle rolled on.Footnote35

Ngurumo emerged out a confluence of interests in Tanganyika’s fraught racial politics. Influential TANU figures worried about the risks of the sort of racial invective in which Mwafrika dealt. Having been overlooked in the elections by the Asian Association’s powerbrokers, with whom he had then fallen out, Thaker spotted an opportunity. His firm ceased to print Mwafrika in March 1959, probably due to its unpaid bills, leaving the press machinery unused.Footnote36 Thaker, with unofficial support from TANU’s leadership, entered the newspaper market himself.Footnote37 The first issue of Ngurumo appeared on 15 April.Footnote38 Ngurumo allowed Thaker to commit himself towards the nationalist struggle, while also providing an alternative pro-TANU voice to Mwafrika. The newspaper sought to generate support for TANU by informing and mobilising the masses. Ngurumo argued that newspapers represented ‘one of those things that are essential for the life of man, from the illiterate to the educated.’Footnote39 Ngurumo balanced support for TANU with a commitment to multiparty democracy rather than a single-party state – a hot topic of debate in Tanganyika’s late colonial public sphere.Footnote40 It stressed the necessity for a rival party to TANU. ‘Where is tomorrow’s opposition,’ Ngurumo asked, ‘and if it does not exist where is democracy?’Footnote41

Ngurumo was an immediate success. Three months after its launch, the colonial government estimated its circulation at 6,000 copies per day.Footnote42 Ngurumo’s cover price, at 10 cents to Mwafrika’s 30 cents, was surely a key factor in its rise, even if it was a shorter newspaper. In June, Mwafrika acquired its own, more modern press from West Germany, which enabled it to publish as a daily title like Ngurumo. In a clear barb towards his rival, Mwafrika’s editor proudly announced that his was the first African company to own a printing press in Dar es Salaam.Footnote43 But even then, Mwafrika’s estimated circulation was just 3,000 – half of that of Ngurumo.Footnote44 Mwafrika did not take kindly to the emergence of an Asian-owned rival. Three days after Ngurumo appeared, Mwafrika responded to a reader who wanted to know whether Ngurumo was ‘the newspaper of the African.’ No, answered Mwafrika, ‘Ngurumo is not the newspaper of the African, it is a newspaper which is published by an Indian-owned company.’Footnote45 Another reader’s letter, inquiring why there were minor discrepancies in reporting between the two newspapers, received a terse reply. ‘Don’t stir a hornets’ nest [usikoroge nyuki],’ the editor warned, ‘since when has MWAFRIKA been NGURUMO?’Footnote46 Doubtless angered by these taunts – and keen to recover unpaid bills – Thaker brought a legal claim for £2,500 against Mwafrika’s owners in February 1960.Footnote47

Meanwhile, Thaker continued to carve out a public position distinct from the majority of other pro-independence Asians in Tanganyika. Ahead of municipal elections in early 1960, Ngurumo’s African executive editor, Stephen Mhando, wrote to the Tanganyika Standard to complain about the gerrymandering of electoral wards designed to return European and Asian councillors. ‘This is a grand opportunity for those Europeans and Asians who have joined the local cry of “Uhuru” to show their mettle […] that they are genuine democrats, by confounding the tricks of those who thrive on [racial] parity’, even ‘at the risk of being considered braying jackasses.’Footnote48 Thaker echoed his employee. ‘Mr. Stephen Mhando has thrown down a challenge to those champions of democracy,’ he wrote in the same newspaper. ‘Will those concerned show the courage of their convictions and pick up the gauntlet?’Footnote49 Thaker charged the Asian Association’s leaders with simply talking of freedom to gain access to public office, but otherwise caring little about race relations, African welfare, or the ‘Asian common man.’Footnote50 The Association in return accused Thaker of making ‘malicious and baseless accusations.’Footnote51

Ngurumo’s origins lay in the paper-based opportunities which nationalist activity created in Tanganyika. Thakers not only produced TANU’s stationery, but became its major creditor. In not pursuing his client’s debts, Randhir Thaker played an instrumental role in TANU’s remarkable expansion. As the constitutional steps towards independence advanced, political differences inside TANU and the Asian Association created a juncture in which Thaker launched a newspaper of his own, which was welcomed by Dar es Salaam’s growing Swahili-language reading public. Randhir Thaker’s political stance isolated him from the majority of Dar es Salaam’s Asian community: his brother, Surendra, later estimated that ‘eighty to ninety percent of Asians hated us.’Footnote52 But Randhir still had to make the most of these conditions. In a series of bold decisions – first to extend credit to TANU and to not call in its debts, and later to break with the Asian Association and found Ngurumo – Randhir demonstrated significant acumen in assembling a print infrastructure that linked his small business to nationalist politics in order to secure his own future in uncertain times. As the response of the country’s leadership to his death showed, Thaker’s gambits were an indisputable success.

Zenith

As Tanganyika attained independence in 1961 and then united with Zanzibar to become Tanzania three years later, Ngurumo cemented its position as the country’s best-selling newspaper. Mwafrika lost the fight over the Swahili-language news market and ran into financial difficulties. It published its final issue in 1965. Meanwhile, TANU established an official weekly newspaper in 1961. Uhuru (‘Freedom’ or ‘Independence’) became Ngurumo’s main competitor, especially after the former became a daily in 1964. Two surveys from around 1967 found that Ngurumo claimed a circulation of 14,000 copies – a figure officially matched by Uhuru, though its circulation was more realistically around 9,000–10,000. If sales figures are difficult to accept with confidence, then assessments of readership – with multiple readers per copy – represent little more than guesswork. In the mid-1960s, Surendra Thaker estimated that Ngurumo was read by around 50,000 people.Footnote53 Even if these numbers are treated as indicative rather than definitive, it seems safe to state that Ngurumo was Dar es Salaam’s most popular newspaper in the 1960s.

There were few trained African journalists in Tanganyika at independence. Ngurumo’s staff learnt on the job. Randhir and later Surendra Thaker, who took over as editor after his brother’s death, headed a small team. The newspaper’s first executive editor, Stephen Mhando, had been TANU’s secretary-general before being charged with embezzling party funds in 1957.Footnote54 Joseph Mzuri replaced Mhando in 1960 and held the post until Ngurumo’s closure. Several of Ngurumo’s fledgling journalists became senior figures in the local media as the state expanded its control of Tanzania’s information apparatus. Mhando later edited TANU’s newspapers. Others worked at Radio Tanzania, the Ministry of Information, and Shihata, the national news agency established in 1976.Footnote55 Surendra Thaker’s claim that Ngurumo trained 80% of Tanzania’s journalists and printers may have been an overstatement, but it certainly played a key role in developing a post-colonial generation of media professionals.Footnote56

Independence posed new questions of the media. Tanzanian politicians, newspapermen, and public intellectuals debated the purpose of the press after empire. Despite Ngurumo’s earlier misgivings, TANU instituted a one-party state in 1965. This was in part predicated on the belief that Tanzania could not afford to waste time and energy on divisive multiparty politics. Similar attitudes informed the stance of party leaders towards the media. Newspapers and radio were to facilitate national development, rather than engage in counterproductive gossip. Some journalists and politicians rejected the concept of the “freedom of the press” as a Western construct, which camouflaged the capitalist and imperialist interests involved in the privately-owned media.Footnote57

Ngurumo bucked the trend. As a small business, Thakers could hardly be accused of acting as a tool for imperialism, especially given its track record of support for TANU. Ngurumo continued to back the party, but also emphasised its editorial freedom. Mzuri described Ngurumo as being ‘completely independent’ of the government. ‘We will criticise wrong and praise right,’ he told an interviewer. ‘We do this regardless of who is involved. There is no limit to anything except the law.’Footnote58 When the government legally empowered itself to ban newspapers which carried subversive material in 1968, Ngurumo insisted that there was nothing to fear in the new legislation, since it was a vocal supporter of the TANU government.Footnote59

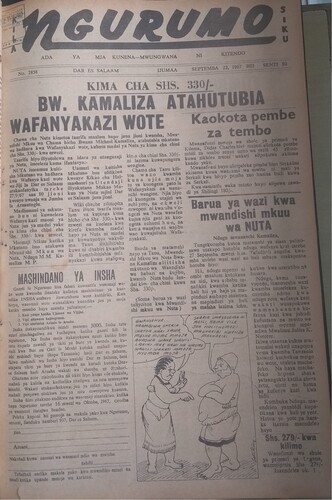

Ngurumo’s success had less to do with any political stance and more with its lively Swahili-language content and affordable cover price. Each issue consisted of a single sheet folded into four pages. The front page carried world and national news (). Page two carried the day’s editorial, alongside a popular forum of readers’ letters. More in-depth reporting and readers’ poetry featured on page three. The back page contained reports on local football and other news snippets. The recipe was simple and unfussy. There were rarely photographs, but Ngurumo compensated for this absence through its popular cartoons, which caricatured urban stereotypes and poked fun at the city’s elites.Footnote60 Ngurumo presented itself as the defender of the interests of the ordinary urban Tanzanian. In particular, it acted as a price watchdog for basic consumer goods and foodstuffs in the Dar es Salaam’s markets. It also reported unusual or gossip-worthy occurrences from the city’s streets, with a certain amount of mystique. When one reader asked Ngurumo to how it obtained information about incidents occurring at night while most people were asleep, the editor simply replied ‘Ngurumo alikuwapo’ – ‘Ngurumo was there’.Footnote61 Another reader responded by describing the newspaper as ‘the eyes of the world’.Footnote62

Figure 1. Front page of Ngurumo, 22 September 1967. East Africana Collection, University of Dar es Salaam Library. Photograph by George Roberts.

Ngurumo’s embrace of a slangy form of Swahili made it accessible to a wider public than the drier prose of Uhuru or the English-language broadsheets. This also resonated with the government’s desire to divest Tanzania of the colonial imposition of English and develop Swahili as a national language.Footnote63 As Derek Peterson and Emma Hunter observe, Ngurumo was an ‘engine for the development of Swahili orthography and grammar.’ The letters page became a forum in which readers debated spellings and argued about whether Arabic-derived words in Swahili belonged in the lexicon of an African nation.Footnote64 This commitment to Swahili drew public praise from government ministers.Footnote65 Indeed, Ngurumo’s advocacy for Swahili at times outpaced the authorities’ own. When the government announced in 1967 that official business would henceforth be conducted in Swahili, Ngurumo held it to its word. A journalist who visited TANU’s headquarters reported a long list of signs on office doors which were still in English and declared that Ngurumo would continue its investigation because ‘we want action.’Footnote66 The following month, an editorial expressed displeasure that ‘nothing at all has changed.’ It noted that workers could still be observed painting ‘stop’ signs on the road. Even TANU was still known by an English name.Footnote67

Ngurumo responded to new market opportunities and the political imperatives of nation-building across mainland Tanzania. At its launch, Randhir Thaker had declared that Ngurumo would give ‘territorial wide coverage’ of affairs.Footnote68 Yet a survey conducted in the mid-1960s found Ngurumo’s readers were overwhelmingly located in Dar es Salaam. To remedy this, Ngurumo advertised for ad hoc regional correspondents and established sales agents in towns such as Arusha and Mtwara.Footnote69 However, Ngurumo remained most successful in coastal areas: a survey in 1968 found that 57% of total sales were in Dar es Salaam, with a further 32% in Tanga.Footnote70 The newspaper reached further north, across the Kenyan border. A reader celebrated Ngurumo’s arrival in Mombasa with a poem venerating the newspaper – a testament to its resonance with a regional Swahili reading public.Footnote71

Given the target readership of Ngurumo, it might be expected to have been a parochial newspaper. Historians who have utilised Ngurumo as part of Dar es Salaam’s ‘street archive’ have emphasised its concern with urban gossip and scandal.Footnote72 Certainly, Ngurumo’s stories were less preoccupied with the affairs of state which dominated Tanzania’s English-language broadsheets. However, even if international news took up fewer column inches, Ngurumo was strikingly engaged in world affairs. This reflected Tanzania’s prominent role in Third World liberation liberation struggles, which turned Dar es Salaam into an oasis for exiled anticolonial movements.Footnote73 Global news made Ngurumo’s front-page headlines; inside, it carried the liberation movements’ press releases. This engagement was shaped by limited capital. Ngurumo could not afford expensive international agency wire services. Instead, it recycled material from foreign radio broadcasts, a technique which had been used by earlier Asian-owned newspapers.Footnote74

Dar es Salaam’s emergence as a “mecca of liberation” in East Africa led to its newspapers becoming drawn into Cold War rivalries. Foreign diplomats recognised that despite its less well-educated readership, Ngurumo was potentially useful. An East German diplomat compared Ngurumo to the ‘tabloids which appear in capitalist countries,’ yet noted that given the newspaper’s wide circulation, its influence should not be underestimated.Footnote75 Foreign powers curried influence by sponsoring visits by Tanzanian journalists abroad. Ngurumo’s journalists took advantage of opportunities to travel abroad for training, including to Israel, East Germany, and an American Press Institute seminar in New York.Footnote76 Moreover, for Ngurumo, these Cold War clients were essential sources of paid content. In the late-1960s, it regularly carried supplements provided by the North Korean embassy, usually on the themes of American neoimperialism in Korea or Vietnam. These jargon-filled and densely-packed columns sometimes ran for ten or more additional pages – more than twice the length of the actual newspaper. Surendra Thaker regarded North Korea as Ngurumo’s best “advertisers,” especially as they paid cash up front.Footnote77

Following the lead of the Tanzanian government, Ngurumo was committed to a non-aligned position in the Cold War.Footnote78 Yet this did not mean it avoided the international issues of the day. Animated by the same credo as the government, Ngurumo attacked imperialism and neocolonialism in all its forms. This criticism was mostly reserved for the United States and its allies. But Ngurumo’s anti-imperial invective was also occasionally turned against the Eastern Bloc. Like the Tanzanian government, Ngurumo condemned the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. It declared that ‘Russia will be mocked even by children without teeth’ for claiming that it had entered Czechoslovakia by invitation from the regime in Prague.Footnote79 A month later, Ngurumo – presumably in return for payment – gave the Soviet embassy space to present its own account of the intervention.Footnote80 However, this transaction did not buy a shift in Ngurumo’s stance. The following day it accused the Soviet Union of telling stories of ‘chickens which lay seven eggs per day […] We want the truth.’Footnote81 Ngurumo presented itself to Tanzanians as a credible source of information in a world awash with Cold War propaganda – material which the newspaper often published itself for financial reasons.

Demise

The Arusha Declaration of 1967 signalled the beginning of Tanzania’s socialist revolution. In the following years, the number of nationalised firms and parastatals mushroomed, while the opportunities for private business diminished. These trends also affected Tanzania’s newspapers. By 1972, there were just three dailies in circulation: the Daily News, owned by the government; Uhuru, owned by TANU; and Ngurumo, owned by Thakers. Yet in many ways, this was a propitious time for the newspaper business, as its potential market continued to grow rapidly. Swahili literacy rates climbed, in part thanks to a pioneering adult education programme. But the simultaneous growth of the state’s reach into all areas of the national economy, including into the publishing industry, foreclosed pathways in an inclement political environment for independent newspapers. In 1976, the last issue of Ngurumo rolled – or, perhaps better, creaked – off the press. Uhuru could draw on the state’s financial support and the infrastructural resources of parastatal printers to meet popular demand. By contrast, Ngurumo’s prospects were restricted by an inability to accumulate or access fresh capital in an era of state socialism.

The Arusha Declaration listed the ‘news media’ as among the sectors of the economy that should be under the control of the workers and peasants, through the government and co-operatives.Footnote82 There was growing opposition to the Standard, once the colonial newspaper of record, which was bought by the multinational conglomerate Lonrho in 1967 and considered a tool of neoimperialism in Tanzania. In 1970, the government bowed to popular demand and nationalised the Standard. This left Ngurumo as the only independently-owned daily newspaper in Tanzania. In response, Ngurumo sounded a word of caution. An editorial which did not directly mention the takeover rendered more abstract questions about the press into an everyday example to which readers could relate by drawing an analogy with the problem of the availability of staple foodstuffs at the market. Just as citizens required reliable information to know where foodstuffs were for sale in times of scarcity, so they needed free access to information about the government in order to make considered choices about their leaders.Footnote83

While Ngurumo was at the height of its popularity, its healthy circulation masked deeper financial problems. From the outset, Thakers had made Ngurumo as affordable as possible. The newspaper marked its ninth “birthday” in 1968 by celebrating the fact that despite increases in printing costs, the cover price remained 10 cents. It was for this reason that the owner had resisted appeals from readers for the newspaper to carry additional pages.Footnote84 Yet cover sales had to account for most of Ngurumo’s revenue. The Thaker brothers rarely carried advertising for cigarettes and never for alcohol on ethical grounds.Footnote85 Most of the paid notices were for small local businesses, whereas the English-language newspapers were able to attract large advertisements for luxury goods and international airlines – products far too expensive for Ngurumo’s typical reader. In any case, advertising was kept to a bare minimum, since space was already at a premium in the newspaper’s four tabloid-sized pages. ‘I want to give my readers a real ten cents worth, not a lot of adverts,’ explained Surendra Thaker.Footnote86 In 1969, he reluctantly increased the cover price for the first time, to 15 cents.Footnote87 By this time, Ngurumo was in serious financial difficulty and dependent on North Korean advertorials.

The challenge for Ngurumo of remaining commercially viable on a day-to-day basis precluded any attempt to resolve the fundamental problems of its business model. Although production moved from Zanaki Street to the industrial suburb of Chang’ombe in 1968, Thakers continued to use the same press on which Randhir Thaker had first produced Mwafrika.Footnote88 This meant a slow process: it took six hours to print 15,000 copies; often printing started a whole day before the newspaper went on sale, meaning that stories had been overtaken by events by the time it reached vendors. Readers complained about news being a day or two late, such as reports on sports matches.Footnote89 Ngurumo had reached its maximum capacity and could not satisfy demand. Surendra Thaker hoped to move the newspaper to a new printing plant, in order to double sales.Footnote90 Yet he lacked the necessary capital to make this kind of investment. The cost of a new press – as much as $75,000 – was well beyond Thakers’ means.Footnote91 Meanwhile, the hand-driven letterpress fell into disrepair, slowing down production and reducing the newspaper’s quality.

As Ngurumo struggled on, the political environment made Surendra Thaker’s position more and more precarious. In the post-Arusha years, Asian-owned businesses came under increasing pressure in Tanzania. Stories about Asians engaging in illegal economic activities abounded. Four Asian brothers who owned the Kanti Printing Works were accused of fraud, placed in detention, and forced to sell the firm in order to pay income tax.Footnote92 Thaker bemoaned that Tanzania’s depleted Asian community had ‘lost our patience too early’ and maintained a sense of racial superiority. ‘Wherever I go my eyes and my heart are for Tanzania,’ he told a researcher.Footnote93 Yet his public comments hinted at the problematic implications of racial inequalities in the workplace. Interviewed by the New York Times in 1973, he said that ‘it will be another 10 or 15 years before there are enough trained Africans to run the economy.’ He added that ‘Asians, I believe, have a greater affection for Dar than do Africans.’Footnote94

Friction between Asian-run businesses and African workers reached its height after TANU’s Mwongozo (‘Guidelines’) in 1971, a revolutionary statement which imbued the economic blueprint of the Arusha Declaration with a sense of political militancy. Workers seized on the document to demand greater say in the running of their firms and to put an end to abusive bosses. A wave of strike action and lock-outs followed. TANU’s long-time motto of ‘uhuru na kazi’ (‘freedom and work’) and the tropes of ‘parasites’ feeding off hard labour gave expression to tensions over workplace hierarchies. These often carried a racial dimension, since the companies’ owners were frequently Asians.Footnote95 Such conflicts were not confined to the factory floor. At the Standard, African employees criticised the leadership of their Asian editor, the South African-born Frene Ginwala.Footnote96

Amid these strikes, Ngurumo’s African employees challenged the authority of Surendra Thaker. In mid-1972, the executive editor, Joseph Mzuri, wrote on behalf of Ngurumo’s staff to several senior figures in the party-state with a scathing denunciation of Thaker. Mzuri stated that Thaker had announced that he wanted Ngurumo to become a weekly rather than a daily title, due to newsprint shortages. The workers interpreted this as a move to wind down Ngurumo altogether. Mzuri recalled that Thaker had tried to close Ngurumo before, during the financial troubles of 1969. The workers had rejected that decision and the matter had reached President Nyerere, who had told Thaker that every effort must be taken to keep Ngurumo running. The workers claimed that this burden had fallen on themselves; they had taken wage cuts and worked overtime, while the printing press had not been repaired. Ngurumo’s employees demanded that the newspaper be brought under their control. Thaker might have been the editor, they stated, but he was ‘unable to write even a single paragraph.’Footnote97

This dispute concluded in 1974, when Thaker and his workers agreed to form the Habari Printers Co-Operative Society, which took control of both the newspaper and the printworks. Mzuri became Ngurumo’s new editor. Thaker subsequently put a positive gloss on this process. ‘We proved that Ngurumo really belonged to the workers and it set an example of practising what we preached – support for the co-operative movement,’ he recalled.Footnote98 Yet the original complaints made by his workers indicate a more acrimonious development. Furthermore, their statement suggests that Nyerere was committed towards the continued existence of Ngurumo in 1969. Ngurumo remained a popular source of entertainment, a vehicle for the Swahili language, and an example to which the government could point in response to accusations that it was intolerant of independent media.

While Ngurumo struggled on, the government acquired rival newspapers as well as – crucially – the infrastructure involved in their production. This provided greater security for the state-owned press, which could ride out economic upheavals and tap into an expanding market of readers. When the government nationalised the Standard in 1970, it did not also immediately acquire Printpak, the firm which produced the newspaper.Footnote99 This meant that the printing operations of a government newspaper, which was supported by public funds, were benefitting a privately-owned firm. Almost a year later, the government still had not completed its planned takeover of Printpak. Ngurumo questioned this delay. It observed that ‘there is no such thing as something called the Standard or Sunday News until the point when customers encounter these newspapers at the street vendors.’ The production of a newspaper involved ink, paper, journalists, other staff, and news from foreign countries. In particular, Ngurumo drew attention to the value of the printer. ‘Right now, citizens do not know how much the government is paying for having its newspaper printed,’ it concluded. ‘If only they knew, they would immediately want the government to nationalise Printpak.’Footnote100

Days after Ngurumo’s editorial, the government announced the acquisition of Printpak.Footnote101 Whether Ngurumo’s intervention catalysed the takeover or whether it got wind of an imminent government decision is unclear. Regardless, the government placed the Printpak under the umbrella of the National Development Corporation (NDC). In 1972, the Standard merged with TANU’s English daily, the Nationalist, to create the Daily News. Ngurumo aside, Tanzania’s daily newspapers were now owned by the party or government and printed by parastatals. The Daily News and Sunday News were produced by Printpak. Uhuru and Mzalendo, a Sunday edition which launched in 1972, were owned by the party’s Mwananchi Publishing Company and printed by the National Printing Company (NPC), another NDC parastatal. These arrangements gave these newspapers privileged access to the material and financial resources of the socialist state. By the mid-1970s, 76% of printing presses in Tanzania were owned by the government. In contrast, the figure for Kenya was just 10%.Footnote102

In these circumstances, Ngurumo struggled to cope with the repercussions of global upheavals which placed its independent, shoestring business under severe strain. First, Ngurumo had to ride out a global shortage of paper, which began in 1973. In October 1974, Ngurumo temporarily reduced its page run because of a lack of newsprint.Footnote103 These problems were compounded by the oil crisis. Third World states like Tanzania, which imported all of its newsprint and faced serious foreign exchange shortages, were hit hardest by these developments. The cost of newsprint imported to Tanzania rose almost threefold, from around 1,600 shillings per ton in 1974 to 4,480 shillings in 1976.Footnote104 Obtaining newsprint was not just expensive, but a time-consuming bureaucratic process involving importer, exporter, and the government.Footnote105 The parastatal printers were not immune to these challenges, but in their case the process was streamlined by government arrangements. During the paper shortage, the NPC was able to use an import grant arranged by the Treasury with the Swedish government, which eliminated the need for direct payment to suppliers.Footnote106 Ngurumo was also hamstrung by the cost of transportation. In 1975, it responded to an increase in the price for rail freight by pointing out that these prohibitive costs would mean that news would not be able to reach the villages. In contrast, it complained, some newspapers – i.e. the party- and government-owned titles – received preferential rates for air transportation.Footnote107

While Ngurumo struggled, Uhuru drew upon state-backed credit to expand its operations. As a parastatal, the NPC was able to make major investments in modern presses. In 1971, using a loan from the Tanzania Investment Bank, the NPC purchased a new web offset press for 800,000 shillings. This gave Uhuru a fresh new look and allowed it to grow from 6 to 8 pages (soon increasing to 12), with only a slight rise in cover cost.Footnote108 Sales for Uhuru grew rapidly. By 1974, they had reached 70,000 per issue. The NPC estimated that this would double again by 1977.Footnote109 To meet this readership, the NPC secured a second loan to finance another new press, to be bought from a Chicago-based firm for 2.5 million shillings. This was made possible by the guarantee of future business for the next seven years from Mwananchi Publishing.Footnote110 All the while, Mwananchi Publishing struggled to keep up its payments to the printers. By March 1976, it owed the NPC 1.7 million shillings. However, the tight web which bound together party, state, and parastatals meant that the NPC could tolerate such deficits.Footnote111 Propped up by these credit facilities and privileged access to scarce materials, Uhuru took advantage of a booming market for Swahili news.

The slick new presses used by Uhuru at least gave its diet of party announcements a contemporary feel, with eye-catching graphic design, modern typefaces, and numerous photographs. By contrast, the rough-and-ready appearance of Ngurumo felt out of date. As Hadji Konde noted, ‘the last copy of “Ngurumo” issued on November 30, 1976 looked almost the same as the first issue of “Ngurumo” of April 15, 1959.’ By this point, circulation was just 2,000 copies, some editions failed to materialise, and the newspaper was running at a deficit of 6,000 shillings per month. According to Konde, there were plans to revive the newspaper in 1977, using facilities at Printpak. Nothing seems to have come of these initiatives.Footnote112

We can only speculate about the reasons for the Tanzanian state’s reluctance to save Ngurumo. Economically, resources were tight: subsidising the flagship newspaper of a dominant party was one thing, propping up a small co-operative was another altogether. The 1970s witnessed the rising influence of a more ideologically dogmatic wing inside TANU, with overspill into the sphere of the media through the ideas of “developmental journalism” that characterised the official newspapers. Just days before the final issue of Ngurumo appeared, the government newspaper declared that it was a ‘necessity’ that the ‘press belongs to the Party and forms an important part of its organisational machinery.’Footnote113 In an era of economic and political austerity, there was little space for the sort of street gossip or suggestive editorials at which Ngurumo had excelled. More prosaically, Ngurumo’s dwindling circulation meant that by 1976 there was little worth saving: people would not suddenly miss something they had ceased to read. Thakers continued to function as a stationer and small-scale printer in Dar es Salaam into the mid-1990s.

Even at the height of Tanzania’s economic crisis, private print media continued to play an important part in cultural life. As Uta Reuster-Jahn has explained, popular entertainment magazines offered alternative, more lively reading matter to the offerings of the party-state. Into the 1980s, several African-edited magazines were funded by Tanzania’s few remaining Asian entrepreneurs.Footnote114 In Dar es Salaam, as Emily Callaci has shown, a cohort of ‘briefcase publishers’ navigated an increasingly precarious publishing landscape to offer pulp fiction commentaries on urban life in a time of economic collapse.Footnote115 In both situations, editors and authors battled the same material scarcities, inability to access capital, and bureaucratic blockages that had led to the demise of Ngurumo. If the successes of this improvised publishing scene attest to the creativity of Tanzania’s print entrepreneurs, their ephemeral nature also highlight the difficulties they faced to get their work to press.

Conclusion

Ngurumo and Randhir Thaker played an underappreciated role in financing and publicising the astonishing rise of TANU. From the mid-1950s, the credit which Thaker extended to TANU provided the party with a print infrastructure which permitted its rapid expansion across the territory. After falling with out his political allies in the Asian Association at a contententious moment, he identified a niche for an affordable newspaper which espoused a more racially inclusive form of nationalism and chimed with the popular interests of a growing urban Swahili readership. After independence, Ngurumo flourished as a forum in which Tanzanians thrashed out the moral economies of ujamaa and embraced Swahili as a language of nation-building and cultural decolonisation. While the ownership of the media came under close scrutiny in post-colonial Tanzania, Ngurumo’s success demonstrated that there was no straightforward opposition between privately-owned and state- or party-owned media. Indeed, the official expressions of grief at Randhir’s death, plus Nyerere’s apparent insistence on Ngurumo’s continued existence when it first encountered financial problems, reflect the high esteem in which it was held by the top strata of government.

Yet Ngurumo’s integral role in Tanzania’s print culture masked problems behind the scenes. Despite the Thaker brothers’ support for TANU, Ngurumo’s Asian ownership became a bone of contention at the height of Tanzania’s socialist revolution. More serious for Ngurumo were the barriers to accessing capital and procuring material supplies under a socialist regime faced with an escalating financial crisis. Paid content from Cold War powers covered cash flow problems, but little more. Ngurumo’s commitment to maintaining an affordable cover price meant that it struggled to stay afloat, let alone invest in new technology which would allow it to meet rising demand. By contrast, the state-owned media benefited from the parastatal printers’ credit facilities and ability to access imported materials which permitted Uhuru to expand even during severe economic hardship.

The story of Ngurumo helps us to move beyond simplistic contemporary debates about press freedom. Since the economic and political reforms of the neoliberal era, Tanzania has re-developed a vibrant newspaper culture. Newsstands teem with titles, even in an age where digital content is the preferred medium of younger generations.Footnote116 Yet comment is not free: bans on newspapers deemed to infringe the government’s sensibilities have proliferated in recent years. However, while formal bans, repressive legislation, and violence against journalists attract local and international outcry, we must understand issues of “press freedom” in broader terms. Pressure on the press comes in less eye-catching forms – for example, in the denial of revenue from government advertising.Footnote117 As Seithy Chachage observed during the 1990s, ‘[f]orums on press and press freedom which concentrate on threats to the press from the state, leaving untouched the question of coercion from within the media (due to patterns of ownership, mechanisms of information control, pressures for profit and money making in general) are misguided.’Footnote118 The rise and fall of Ngurumo sheds historical light on these hidden limitations and financial bottlenecks which continue to shape East African public spheres today.

Acknowledgements

My greatest thanks are due to librarians at the National Library in Dar es Salaam, the East Africana Collection at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM), and particularly to Cosma Nchimbi at UDSM’s School of Journalism and Mass Communications. In the UK, librarians at King’s College London and the University Library in Cambridge helped to loan microfilm copies from the Library of Congress. The seeds of this article lie in comments by Ismay Milford on a section of my book manuscript, which encouraged me to turn a short paragraph into a longer piece of research. James Brennan helped out by generously sharing archival materials at the height of the pandemic. I presented an earlier version of this article at a workshop on ‘Press, Print, and Publishing in Tanzania since Independence’ in November 2021, which was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh. I would like to thank participants for their comments on my paper, especially Emma Hunter and Musa Sadock. Finally, thanks to the Journal’s two reviewers for their constructive and clarifying engagement with the text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Ngurumo, “Rais amesimama akitazama kwa masikitiki,” 6 November 1965, 4; Daily Nation, “President at funeral of Dar editor,” 5 November 1965, 19.

2 Sijaona, handwritten letter, 4 November 1965, reproduced in Ngurumo, 6 November 1965, 4.

3 Ngurumo, “Waasia igeni mfano wa Randhir Thaker,” 8 November 1965, 1.

4 Peterson, Hunter, and Newell, eds, African Print Cultures. For Tanganyikan and Zanzibari examples, see Glassman, “‘Sorting Out the Tribes”; Hunter, “‘Our Common Humanity’”; Hunter, Political Thought.

5 Cane, Fourth Enemy; Smith, Mexican Press; Freije, Citizens of Scandal.

6 On the media and publishing industry in Tanzania, see Suriano, “Dreams”; Sturmer, Media History.

7 Condon, “Nation Building,” 335.

8 Ng’wanakilala, Mass Communication, 18n13.

9 Konde, Press Freedom, 43.

10 Scotton, “Tanganyika’s African Press.”

11 Ochs, African Press, 57–8, who erroneously writes that “[f]rom 1958 [sic] to 1964 [sic], the Swahili daily Ngrumo [sic] was owned and published by an Asian, R.B. Thacker [sic].”

12 Ivaska, Cultured States; Callaci, Street Archives.

13 Brennan, “Politics and Business,” 44. See also Brennan, “Print Culture.”

14 For another study of the connections between business, politics, and media in Tanzania, see Fair, Reel Pleasures.

15 Through the collections at the Tanzania National Library, the University of Dar es Salaam, and the Library of Congress, I have consulted around ninety percent of issues of Ngurumo from 1964 to 1976. I located some earlier copies from 1959–63 which are enclosed in various archival records or available at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

16 Brennan, “Politics and Business.”

17 On the political economy of newspapers in colonial Kenya, see Gadsden, “African Press”; Frederiksen, “Print”; Musandu, Pressing Interests.

18 Scotton, “Tanganyika’s African Press,” 5; Westcott, “East African Radical”; Brennan, “Constructing Arguments”, 216.

19 Leslie, Survey, 195–200.

20 Gregory, Quest for Equality, 181; Brennan, “Print, Reading, and Patronage,” 373.

21 Gregory, Quest for Equality, 181; United Kingdom National Archives, Kew (UKNA), FCO 141/17862, Tanganyika Special Branch, Asian “Who’s Who,” entry for “Randhirkumar Bhanushanker Thaker,” September 1958.

22 Brennan, “Print Culture,” 114.

23 UKNA, FCO 141/17809/180, advertisement for TANU meeting, enclosed in Commissioner of Police to Chief Secretary, 8 August 1955; UKNA, FCO 141/17801/60, copy of TANU constitution, 1955.

24 UKNA, FCO 141/17809/126, Commissioner of Police to Chief Secretary, 9 June 1955.

25 UKNA, FCO 141/17804/6, TANU Headquarters, “Financial Report for the Period Commencing October 1956 to April 1957,” translated and enclosed in Commissioner of Police to Chief Secretary, 8 May 1957.

26 UKNA, FCO 141/17804/165, TANU Headquarters to Provincial Secretaries, translated and enclosed in Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 28 August 1957.

27 UKNA, FCO 141/17805/23, Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 27 October 1957.

28 UKNA, FCO 141/17806/194, Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 4 June 1958.

29 UKNA, FCO 141/17806/101, Minutes of Annual General Meeting of TANU, Tabora, 20–5 January 1958, enclosed in Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 31 January 1958.

30 UKNA, FCO 141/17862, Tanganyika Special Branch, Asian “Who’s Who,” entry for “Randhirkumar Bhanushanker Thaker,” September 1958; UKNA, FCO 141/17804/15, Commissioner of Police to Chief Secretary, 15 May 1957. Thakers’ ability to sustain such large debts raises the possibility that it was receiving subsidies from a third-party source, potentially the Indian high commission – but this can be no more than speculation.

31 Tanganyika Standard, “Printer claims £2,500 from Mwafrika,” 2 February 1960, 3.

32 UKNA, FCO 141/17806/162, Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 12 May 1958.

33 UKNA, FCO 141/17805/23, Commissioner of Police to Ministerial Secretary, 27 October 1957; UKNA, FCO 141/17807/188, Commissioner of Police to Chief Secretary, 19 May 1958.

34 Brennan, “South Asian Nationalism,” 32–3. More generally, see Brennan, Taifa.

35 Jhaveri, Marching with Nyerere, 65–6, 114–6.

36 Tanganyika Standard, “Printer claims £2,500 from Mwafrika,” 2 February 1960, 3.

37 Stephens, Political Transformation, 110.

38 Tanganyika Standard, “New paper”, 16 April 1959, 1.

39 UKNA, FCO 141/17950, Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 11 April 1960, 2.

40 Hunter, Political Thought, ch.7.

41 UKNA, CO 822/1363/270, extract from Tanganyika Intelligence Report, August 1959.

42 UKNA, FCO 141/17959, min. 212, Acting Permanent Secretary, Office of the Chief Secretary, to Director of Public Relations, 21 July 1959.

43 UKNA, FCO 141/17959, min. 167, Senior Public Relations Officer, 8 June 1959.

44 UKNA, FCO 141/17959, min. 188, Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Security and Immigration, to Minister of Security and Immigration, 17 July 1959.

45 Mwafrika, 18 April 1959, 1.

46 UKNA, FCO 141/17959/212, R. H. K. Mbilinyi, letter to the editor, Mwafrika, 7 August 1959, 2.

47 Tanganyika Standard, “Printer claims £2,500 from Mwafrika,” 2 February 1960, 3. The outcome of the case is unclear.

48 Stephen Mhando, letter to the editor, Tanganyika Standard, 7 October 1959, 2.

49 R. B. Thaker, letter to the editor, Tanganyika Standard, 13 October 1959, 2.

50 Ramdhir [sic] B. Thaker, letter to the editor, Tanganyika Standard, 25 January 1960, 2.

51 S. Sarda and H. P. Shangvi, letter to the editor, Tanganyika Standard, 9 February 1960, 2.

52 Gregory, Quest for Equality, 108.

53 Condon, “Nation Building,” 336; Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 250. Konde (Press Freedom, 43) put Ngurumo’s peak circulation at 40,000. This figure is cited by both Ivaska (Cultured States, 30) and Callaci (Street Archives, 32), but is impossibly high given the limitations on production explained here.

54 On Mhando, see Roberts, “TANU’s Bombay Delegates.”

55 Konde, Press Freedom, 42.

56 Gregory, Quest for Equality, 181.

57 See Roberts, Revolutionary State-Making, 218–9.

58 Quoted in Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 245–6.

59 Ibid., 217.

60 See examples in Ivaska, Cultured States.

61 Juma Pole, letter to the editor, Ngurumo, 28 March 1961, 2.

62 S. N. Mkwawa, letter to the editor, Ngurumo, 6 April 1961, 2.

63 Abdulaziz, “Ecology.”

64 Peterson and Hunter, “Print Culture,” 31.

65 Ngurumo, “Babu asifu Ngurumo wajua uandishi,” 1 September 1969, 1.

66 Ngurumo, “Lugha ya kiswahili:– ‘tunataka vitendo,’” 26 January 1967, 4.

67 Ngurumo, “Kiswahili,” editorial, 28 February 1967, 2.

68 Tanganyika Standard, “New paper,” 16 April 1959, 1.

69 Ngurumo, “Nafasi za uandishi,” 16 October 1964, 2; Ngurumo, “Ngurumo Mtwara,” 21 April 1967, 4; Ngurumo, “Ngurumo Arusha,” 16 May 1967, 4.

70 Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 250.

71 M. O. Riko Ngare, “Ngurumo Mombasa,” Ngurumo, 12 December 1967, 4.

72 Ivaska, Cultured States; Callaci, Street Archives.

73 Roberts, Revolutionary State-Making.

74 Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 245.

75 Bundesarchiv, Berlin (BArch), SAPMO, DY30/IV A 2/20/964, Junghanns, 1 November 1968.

76 Ngurumo, “Mkurungenzi wa Ngurumo safarini,” 21 October 1961, 2; Ngurumo, “Aenda Ujerumani,” 6 October 1965, 1; New York Times, “Africa newsmen to attend seminar,” 4 September 1966, 42.

77 National Archives and Records Administration, College Park (NARA), Record Group (RG) 59, Central Foreign Policy Files (CFPF) 1967–1969, Box 2513, POL2, Burns to State Dept, 9 May 1969. On North Korea’s use of foreign newspapers for propaganda, see Young, Guns, 53–9.

78 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 9 May 1969, 2.

79 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 23 August 1968, 2. On Tanzania’s response to events in Czechoslovakia, see Roberts, Revolutionary State-Making, 183–7.

80 Ngurumo, “Mkataba wa kirafiki usioweza kuvunjika,” 23 September 1968, 3–4.

81 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 24 September 1968, 2.

82 “The Arusha Declaration,” in Nyerere, Freedom and Socialism, 233–4.

83 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 11 February 1970, 2.

84 Ngurumo, “Kuzaliwa,” 15 April 1968, 1, 4.

85 Syracuse University Archives, Robert Gregory Papers, Martha Honey interview with Surendra Thaker, 8 March 1973. I am grateful to James Brennan for sharing his notes on this document.

86 Quoted in Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 242–3.

87 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 28 January 1969, 1.

88 Ngurumo, 30 August 1968, 2. Thakers appears to have maintained a shop on Zanaki Street.

89 G. S. Bujiku, “Nataka Ngurumo iwe … ,” letter to the editor, Ngurumo, 28 February 1975, 2.

90 Mytton, “Role of the Mass Media,” 241–2.

91 NARA, RG 59, CFPF 1967–69, Box 2513, POL2, Burns to State Dept, 28 March 1969.

92 Uhuru, “Wahindi 4 wafukuzwa nchini!,” 13 August 1969, 1; Aminzade, Race, 230–1.

93 Honey interview with Surendra Thaker, 8 March 1973.

94 New York Times, “‘Abode of peace’ has sluggish economy,” 4 February 1973, 35, 45.

95 Shivji, Yahya-Othman, and Kamata, Development as Rebellion, vol. 3, 212–20.

96 Roberts, Revolutionary State-Making, 229–30.

97 National Records Centre, Dodoma, Prime Minister’s Office Papers, Box 364, PM/N40/1/40, Mzuri to General Secretary, TANU, “Azimio la wafanyakazi kuendesha Ngurumo kijamaa,” n.d..

98 Konde, Press Freedom, 43.

99 According to the Standard Group’s chairman, the government was unaware that the Standard did not own its printing works when it nationalised the newspaper. Chande, Knight in Africa, 139.

100 Ngurumo, “‘Jagabule,’”, editorial, 14 January 1971, 2.

101 Daily News, “20 years anniversary of Printpak (T),” 28 April 1986, 6.

102 Wilcox, Mass Media, 51–2. On printers, see Bgoya, Books and Reading, 20–5.

103 Ngurumo, “Tatizo … ,” 4 October 1974, 1. Ngurumo had expanded from four to six pages in June 1974. Given the ceiling on daily print runs caused by is outdated press, this would appear to indicate falling circulation, rather than an increase in the total number of pages printed daily.

104 Konde, Press Freedom, 84.

105 Wilcox, Mass Media, 51–2.

106 Tanzania National Archives, Dar es Salaam (TzNA), 596/21/IA/NPC/5, NPC, Annual Plan for 1975.

107 Ngurumo, “Vita baridi,” editorial, 7 July 1975, 2.

108 Uhuru, “Uhuru jipya kwa umma,” 5 August 1971, 1.

109 TzNA, 596/21/IA/NPC/5, NPC, Annual Plan for 1975.

110 TzNA, 596/21/IA/NPC/5, NPC, Board Paper No. 5/75 – Capital Expenditure.

111 TzNA, 596/21/IA/NPC/5, NPC, Minutes of the 2nd Quarterly Board Meeting of Directors, 2 January 1976.

112 Konde, Press Freedom, 43; Musalali, “Case Study,” 9.

113 Ferdinand Ruhinda, “Transnational power and mass media,” Sunday News, 21 November 1976, 4.

114 Reuster-Jahn, “Private Entertainment Magazines.”

115 Callaci, “Street Textuality.”

116 Srinivasan, Diepeveen, and Karekwaivanane, “Rethinking Publics.”

117 Conversation with a newspaper editor, Dar es Salaam, April 2019.

118 Chachage, “Democracy,” 74.

Bibliography

- Abdulaziz, Mohamed Hassan. “The Ecology of Tanzanian National Language Policy.” In Language in Tanzania, edited by Edgar C. Polomé, and C. P. Hill, 139–175. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Aminzade, Ronald. Race, Nation, and Citizenship in Post-Colonial Africa: The Case of Tanzania. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Bgoya, Walter. Books and Reading in Tanzania. Paris: UNESCO, 1988.

- Brennan, James R. “Constructing Arguments and Institutions of Belonging: M. O. Abbasi, Colonial Tanzania, and the Western Indian Ocean World.” Journal of African History 55, no. 2 (2014): 211–228.

- Brennan, James R. “Print Culture, Islam and the Politics of Urban Caution in Late Colonial Dar es Salaam: A History of Ramadhan Machado Plantan’s Zuhra, 1947–1960.” Islamic Africa 12, no. 1 (2022): 92–124.

- Brennan, James R. “Print, Reading, and Patronage in the Colonial-Born Presses of the Indian Diaspora in Africa.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 35, no. 2 (2015): 369–375.

- Brennan, James R. “Politics and Business in the Indian Newspapers of Colonial Tanganyika.” Africa 81, no. 1 (2011): 42–67.

- Brennan, James R. “South Asian Nationalism in an East African Context: The Case of Tanganyika, 1914–1956.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 19, no. 1 (1999): 24–39.

- Brennan, James R. Taifa: Making Nation and Race in Urban Tanzania. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2012.

- Callaci, Emily. Street Archives and City Lives: Popular Intellectuals in Postcolonial Tanzania. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

- Callaci, Emily. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975–1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 59, no. 1 (2017): 183–210.

- Cane, James. The Fourth Enemy: Journalism and Power in the Making of Peronist Argentina, 1930–1955. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

- Chachage, C. S. L. “Democracy and the Fourth Estate in Tanzania.” In Political Culture and Popular Participation in Tanzania, 73–86. Dar es Salaam: REDET Project, 1997.

- Chande, J. K. A Knight in Africa: Journey from Bukene. Manitoba, ON: Penumbra, 2005.

- Condon, John C. “Nation Building and Image Building in the Tanzanian Press.” Journal of Modern African Studies 5, no. 3 (1967): 335–354.

- Fair, Laura. Reel Pleasures: Cinema Audiences and Entrepreneurs in Twentieth-Century Urban Tanzania. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2018.

- Frederiksen, Bodil Folke. “Print, Newspapers and Audiences in Colonial Kenya: African and Indian Improvement, Protest and Connections.” Africa 81, no. 1 (2011): 155–172.

- Freije, Vanessa. Citizens of Scandal: Journalism, Secrecy, and the Politics of Reckoning in Mexico. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

- Gadsden, Fay. “The African Press in Kenya, 1945–1952.” Journal of African History 21, no. 4 (1980): 515–535.

- Glassman, Jonathon. “Sorting Out the Tribes: The Creation of Racial Identities in Colonial Zanzibar’s Newspaper Wars.” Journal of African History 41, no. 3 (2000): 395–428.

- Gregory, Robert G. Quest for Equality: Asian Politics in East Africa, 1900–1967. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 1993.

- Hunter, Emma. “‘Our Common Humanity’: Print, Power, and the Colonial Press in Interwar Tanganyika and French Cameroun.” Journal of Global History 7, no. 2 (2012): 279–301.

- Hunter, Emma. Political Thought and the Public Sphere in Tanzania: Freedom, Democracy and Citizenship in the Era of Decolonization. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Ivaska, Andrew. Cultured States: Youth, Gender, and Modern Style in 1960s Dar es Salaam. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

- Jhaveri, K. L. Marching with Nyerere: Africanisation of Asians. Delhi: BR Publishing Corporation, 1999.

- Konde, Hadji S. Press Freedom in Tanzania. Arusha: Eastern Africa Publications, 1984.

- Leslie, J. A. K. A Survey of Dar es Salaam. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Musalali, M. A. A Case Study – Ngurumo Newspaper. Unpublished final year mass communications project, Tanzania School of Journalism, 1980.

- Musandu, Phoebe. Pressing Interests: The Agenda and Influence of a Colonial East African Newspaper Sector. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018.

- Mytton, Graham. The Role of the Mass Media in Nation-Building in Tanzania. PhD diss., University of Manchester, 1976.

- Ng’wanakilala, Nkwabi. Mass Communication and Development of Socialism in Tanzania. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House, 1981.

- Nyerere, Julius K. Freedom and Socialism: A Selection from Writings and Speeches, 1965–1967. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Ochs, Martin. The African Press. Cairo: American University of Cairo Press, 1986.

- Peterson, Derek R., and Emma Hunter. “Print Culture in Colonial Africa.” In African Print Cultures: Newspapers and their Publics in the Twentieth Century, edited by Derek R. Peterson, Emma Hunter, and Stephanie Newell, 1–45. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

- Peterson, Derek R., Emma Hunter, and Stephanie Newell, eds. African Print Cultures: Newspapers and their Publics in the Twentieth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

- Reuster-Jahn, Uta. “Private Entertainment Magazines and Popular Literature Production in Socialist Tanzania.” In African Print Cultures: Newspapers and their Publics in the Twentieth Century, edited by Derek R. Peterson, Emma Hunter, and Stephanie Newell, 224–250. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

- Roberts, George. Revolutionary State-Making in Dar es Salaam: African Liberation and the Global Cold War, 1961–1974. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Roberts, George. “TANU’s Bombay Delegates: Stephen Mhando, Ali Mwinyi Tambwe, and the Global Itineraries of Tanganyikan Decolonisation.” Tanzania Zamani 14, no. 1 (2022): 1–44.

- Scotton, James F. “Tanganyika’s African Press, 1937–1960: A Nearly Forgotten Pre-Independence Forum.” African Studies Review 21, no. 1 (1978): 1–18.

- Shivji, Issa G., Saida Yahya-Othman, and Ng’wanza Kamata. Development as Rebellion: A Biography of Julius Nyerere. 3 vols. Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2012.

- Smith, Benjamin T. The Mexican Press and Civil Society, 1940–1976: Stories from the Newsroom, Stories from the Street. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

- Srinivasan, Sharath, Stephanie Diepeveen, and George Karekwaivanane. “Rethinking Publics in Africa in a Digital Age.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 13, no. 1 (2019): 2–17.

- Stephens, Hugh W. The Political Transformation of Tanganyika, 1920–67. New York: Praeger, 1968.

- Sturmer, Martin. The Media History of Tanzania. Mtwara: Ndanda Mission Press, 1998.

- Suriano, Maria. “Dreams and Constraints of an African Publisher: Walter Bgoya, Tanzania Publishing House and Mkuki na Nyota, 1972–2020.” Africa 91, no. 4 (2021): 575–601.

- Westcott, N. J. “An East African Radical: The Life of Erica Fiah.” Journal of African History 22, no. 1 (1981): 85–101.

- Wilcox, Dennis L. Mass Media in Black Africa: Philosophy and Control. New York: Praeger, 1975.

- Young, Benjamin R. Guns, Guerillas, and the Great Leader: North Korea and the Third World. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2021.