ABSTRACT

Background

Dental anxiety in children is a major health concern. Process drama adopts distancing techniques that allow children to examine the possible causes of dental anxiety safely and with authority. Using this method to inform paediatric dentistry is novel and could be adopted in other fields where children experience health-related anxiety.

Methods

A 90-minute process drama workshop was conducted in three primary schools in Batley,West Yorkshire. Sixty-three children participated in the study. Sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed and thematic analysis conducted.

Results

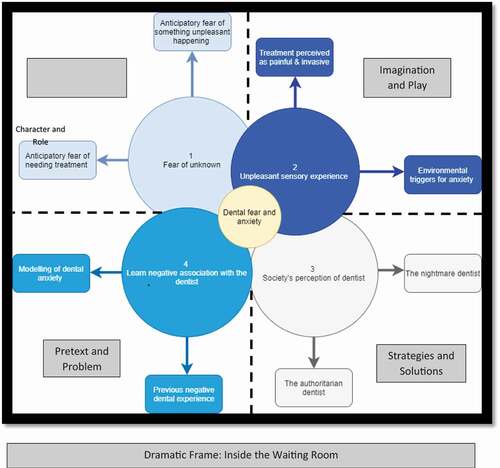

Four key concepts emerged: 1) Fear of the unknown; 2) Unpleasant sensory experience; 3) Society’s perception and portrayal of the dentist and 4) Learnt negative associations with the dentist.

Conclusion

Process drama offers a novel approach to develop an understanding of dental anxiety in children. It elicits critical insights from a child’s perspective and offers a participatory model for engaging children in health research on sensitive issues.

Introduction

Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) are common problems that can affect people of all ages but appear to develop mostly in childhood and adolescence (Locker et al., Citation1999; Tickle et al., Citation2009). Patients with DFA are more likely to avoid dental care (Morgan et al., Citation2017), which may result in significant deterioration of oral health in later life. Untreated dental caries increase the likelihood of pain and can lead to a spiral of increasing dental anxiety (Armfield et al., Citation2007). The extent to which this is a causal relationship is unknown. Finding new ways to understand the complex psychology of dental fear and anxiety in children is critical to the development of interventions designed to improve the lives of patients. Conventional qualitative methods do not always enable children to express that which is difficult to put into words. Using a combination of cognition, emotion and embodiment (De Coursey, Citation2018), drama offers a way to investigate complex and difficult topics through a process of dramatic distancing (Eriksson, Citation2011).

The RAPID projectFootnote1 is a cross-disciplinary collaboration between specialists and researchers of applied theatre and paediatric dentistry at the University of Leeds. It was designed to apply well-established methods from the field of drama education to the exploration of the causes of dental anxiety in children. The long-term aim of the project is to inform policy and practice in paediatric dentistry and to reconsider the application of process drama as a methodology for researching complex or sensitive issues with children.

This article provides an overview of the practice-based element of the project which was conducted in May 2019 and outlines the methods adopted within a 90-minute drama workshop carried out in three primary schools in Batley, West Yorkshire. It reports on the initial findings that emerged from the thematic analysis of the data and presents these as a layered, multi-perspectival “map” that demonstrates not only the complexity of the topic under investigation but also the wealth of nuanced data gathered in a short space of time. Finally, it evaluates the methodological advantages and challenges of adopting process drama as a novel approach to oral health research with children, focussing specifically on dramatic framing and critical distancing.

The terms “dental fear” and “dental anxiety” are frequently used interchangeably. The umbrella term “dental fear and anxiety” (DFA) will be used in this paper.

Understanding dental anxiety: priorities, methods and challenges

Dental anxiety in children is widespread and yet little is known about how it develops and what might be done to prevent it in its early stages. It is considered by some researchers as a type of trait anxiety correlated with factors related to personality (Fuentes et al., Citation2009), socioeconomic factors (Carrillo‐Diaz et al., Citation2012), genetic factors (Chaki & Okuyama, Citation2005) and by others as specific and distinct but not necessarily associated with trait anxiety (Chapman & Kirby-Turner, Citation1999). There are several systematic reviews estimating the prevalence of dental anxiety in children and adolescents. The systematic review by Klingberg and Broberg (Citation2007) measured the prevalence and means a score of DFA across a range of measures in children/adolescents. In their review, 17 studies were included. They showed the prevalence for DFA range from 5.7% to 19.5% (12 populations) with a mean over all applicable studies of 11.1%. Cianetti et al. (Citation2017) corroborated the prevalence incidence indicating that at least one child out of ten had a level of DFA that hindered their ability to tolerate dental treatment and that the prevalence was higher in females than males and decreased with increasing age. A recent systematic review with meta‐analyses of observational studies published between 1985 and 2020 by Grisolia (Citation2020) revealed overall pooled dental anxiety (DA) prevalence was 23.9%. Pooled prevalence in preschoolers, schoolchildren, and adolescents was as follows: 36.5%, 25.8% and 13.3% respectively. They concluded that DA is a frequent problem in 3‐ to 18‐year‐olds worldwide and is more prevalent in school children and preschool children than in adolescents.

The assessment of DFA is complex. Researchers rely on three key methods to measure dental anxiety in children. The first method is “behaviour assessment” in which the dental team or researchers are asked to rate both the emotional and behavioural reactions shown by the children during treatment. The second approach is “psychometric assessment” in which the children or one of their parents have to complete a questionnaire, such as the Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS), Modified Child Dental Anxiety Scale (MCDAS) or Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale (CFSS-DS) questionnaire (Porritt et al., Citation2013). This assessment is usually carried out before a child receives treatment in order to determine the level of anxiety associated with different common dental situations. The third technique is “physiological response analysis” in which various factors linked to anxiety are measured, such as heart rate or salivary cortisol level (Porritt et al., Citation2013).

Each of these DFA assessments is typically conducted within a dental surgery where the child may be exhibiting increased levels of anxiety and fear. The aim of these assessments is to measure fear rather than explore the cause. Ascertaining the root causes of DFA or other childhood anxieties with absolute precision or certainty is challenging. How children develop dental anxiety in the first instance is poorly understood and the views of the child are rarely sought outside of the dental setting. Most studies rely on the completion of questionnaires by parents (Tickle et al., Citation2009) or use conventional qualitative methods that are not always effective channels for children to express complex ideas and emotions. The RAPID project aimed to adopt an approach that a) situated children at the centre of the inquiry as “experts” b) conducted the work beyond the dental setting with children who may or may not have DFA c) adopted distancing techniques common to drama education practices in order to find new ways of understanding the causes of dental anxiety in children.

Process drama as methodology: child-centred inquiry, distance and meaning-making

Process drama is a method of teaching and learning where both pupils and teacher work in and out of role to explore a problem, situation, theme or issue. Developed in the 1980s, the pedagogy of Dorothy Heathcote (Heathcote & Bolton, Citation1995) underpins the practice that was coined as “process drama” in the early 1990s by O’Neill (Citation1991). It is an established method for engaging children in critical thinking by working through the given circumstances of a fictional context (see Heathcote et al., Citation1991). The work is unscripted but follows a framework set out by the teacher or facilitator. With its roots in dramatic play, this framework allows pupils to create an imaginary scenario in which they work together to find solutions to ethical, moral or social questions. In this model, the drama classroom becomes a space to generate and test hypotheses and the art form is harnessed as a “valuable and legitimate research methodology” (Norris, Citation2000, p. 41) rather than as an adjunct to the research (common to many arts/health collaborations) or as a dissemination tool deployed in the closing stages of the inquiry.

Dramatic distancing is rooted in the work of Bertolt Brecht and his concept of Verfremdungseffeckt (estrangement) (Willet, Citation1964). Distancing, or the effect of “making strange”, creates a protective distance between the self and the fictive role (Bolton, Citation2006, p. 58) and is also used as a rhetorical device for defamiliarisation. Distance is achieved through “disrupted narrative techniques” (Eriksson, Citation2011, p. 118) such as non-chronological storytelling, role reversal, direct address, time distortion, stylisation, demonstration, observation, reflection and so on. These techniques serve to interrupt the narrative so that participants can pay close, critical attention to particular elements and intervene in the drama as it unfolds. A key element of process drama is to alter the viewing frame for participants thereby shifting their perspective and activating criticality. Adopting a role different from their own allows children to view problems from a new perspective. The fictional frame keeps the children “one step removed” (Baim et al., Citation2002) from the issue itself, thus providing greater emotional distance from which to view material or content that might be challenging or upsetting. In creating a structure that allows participants to move between observing, reflecting and hypothesising, process drama becomes an “investigatory tool” (Bolton, Citation1996, p. 187) in which children are positioned as active makers of meaning within the drama and, in turn, the research process.

The project: aims, methods and materials

Using process drama as the primary methodology, pupils involved in the RAPID project were encouraged to a) identify some of the causes of dental anxiety in children and b) develop strategies for minimising it. Working through a fictional scenario the children were not delivered any direct oral health messages but were invited to articulate their views, ideas and opinions through well-established conventions from the process drama tradition, in particular that of the “mantle of the expert” (Heathcote & Bolton, Citation1995). The workshop plan followed a structure and adopted techniques that will be familiar to those working within the field of applied theatre practice. However, to our knowledge, this is the first time such an approach has been applied within the field of oral health research. As such, it represents a significant departure from conventional methodology in dentistry and offers a model that could be adopted in other health-related fields.

Five primary schools in the Batley area of West Yorkshire were identified through the RAISED in Yorkshire collaborationFootnote2. After contacting the head teachers of these primary schools, three schools agreed to take part. Information sheets regarding the study with the consent and assent forms were distributed through the schools to the parents/carers of children aged 7–10 years old. Each school was offered a 90-minute workshop for a single class of pupils. The workshop was planned by the research team and delivered as consistently as possible in each school setting. Each workshop was facilitated by two applied theatre specialists and assisted by one dental student and one paediatric dental specialist. At each session, one class teacher was present and accompanied by one teaching assistant. Everyone in the room participated in all activities and there was no external “audience”.

In total 63 children aged 7–10 years old participated in this study and 3 workshops were audio recorded and transcribed. These transcripts were read and re-read repeatedly to ensure familiarisation with the data and to generate ideas for initial codes following a descriptive qualitative approach using thematic analysis at a semantic level to explore the explicit and surface-level meanings of the data. The entire data set including transcripts of the process drama and notes made by the children in related activities were triangulated and coded using Nvivo. These codes were then collated to identify significant patterns in the data to form initial themes and sub-themes, which were continually refined to ensure clarity and consistency in meaning.

Workshop overview

The overarching aim of the workshop was to encourage children to identify the causes of dental anxiety, investigating the topic using key conventions of process drama, in particular: teacher in role, the mantle of the expert, still images and hot seating, all of which are discussed in more depth below.Footnote3 The children were invited into what drama educationalist John Somers calls an “incomplete narrative” containing a “life tension” from which the exploration flows (Somers, Citation2002, p. 105). The fiction was left open intentionally. Very few clues were given about the central character and no resolution was offered. Instead, the children were presented with a situation, a character and a challenge. This openness allowed the children to project their own narratives onto the fiction, enabling them to steer the drama according to their own interest, experience and understanding of the issue of DFA from the perspective of an “expert”.

Establishing the “rules of the game”

After informal introductions, the facilitator framed the workshop as an opportunity to help the research team out with a “problem”. The facilitator told the children they would be working through a story to find out possible solutions to the problem and asked if they would be happy to play different characters along the way. The facilitator explained that she and other members of the research team would also be playing different characters and that they would give clear signals when this was going to happen. Once an agreement had been reached, the workshop began with a simple ice breaker activity that introduced the broad topic of “going to the dentist” in a fun and informal way. Sharing findings with the whole group provided the bridge into the next section where the fictional scenario was explained.

Setting up the scenario

Inside the waiting room: the facilitator introduced the fiction by explaining that the children would be adopting the role of child psychologists. This technique is known as the “mantle of the expert” and sees the children taking on a high status, professional role in order to solve a problem. Adopting the position of expert affords the children authority over the topic and thus a degree of protection from self-disclosure of their own anxieties. Having reorganised the chairs into a more formal setting and in role as a worried social worker, the facilitator then welcomed the pupils to a meeting and explained that their help was needed with a particular child, “Katie”, who had developed severe dental anxiety. Katie was in urgent need of dental treatment so it was imperative that the psychologists helped resolve her anxiety.

Staying in role as the social worker, the facilitator explained that the “experts” would be able to see the child sitting in a dental waiting room via a two-way mirror.Footnote4 Katie would not be able to see the psychologists but they should observe her quietly. The theatrical convention of placing an imaginary barrier between the observers and the observed allows the facilitator to act as a bridging character, guiding the children’s viewing, eliciting responses and enabling discussion to flow whilst the action continues. During this section an actor-teacher played the role of the child waiting to be called for her appointment. The action was mimed and restricted to a limited set of movements that were repeatable in each school setting. Katie was observed waiting nervously, biting her nails, listening to music on headphones and shrugging off unwanted attention from a parent. Staying in role throughout, the facilitator asked the children what they had observed and asked them to make initial assessments as to the possible causes of the behaviour being displayed.

The fiction focussed entirely on the moments leading up to a visit to the dentist and the anxieties this might provoke. The research team was mindful of not reinforcing negative associations of visiting the dentist but, at the same time, wanted to provide the children with an opportunity to examine forensically the behaviours as observed and what they might signal. The dramatic frame provided an opportunity to pay close and deliberate attention to the space, movement, gesture, and language of someone experiencing DFA. This was particularly useful in helping the children articulate their views on the relationship between thought, feeling and action as embodied in the character of Katie.

Creating the internal world

Working through still image: the next section of the workshop shifted the focus away from working in role to creating the internal world of the character. In small groups, the pupils were asked to create a still image of what they felt Katie was feeling. They were then asked to share these images with the whole class and explain the pictures they had made. Working in a more abstract way allowed the children to operate on a level “beyond the boundaries of [their] own experience” (Neelands, Citation1984, p. 65). It provided them with the opportunity to access alternative registers of experience and feeling that might not easily be expressed in words. This part of the workshop produced creative, inventive and arguably the most insightful responses to the root cause of Katie’s anxiety which are discussed in the thematic analysis later.

Probing the problem

Working through hot seating: in the next section the children returned to their roles as child psychologists and had the opportunity to decide which other characters might be able to assist them in their investigation. The children suggested it would be useful to talk to Katie’s parent, her school friends, teachers and the dentist to see if they could shed light on the situation. The whole research team was involved in playing the various roles suggested by the children and a very rich period of open questioning was enacted by each class. Very few concrete answers or clear reasons for Katie’s anxiety were provided by members of the research team working in role, meaning that the class had to work hard with limited clues. Concluding this section without providing a closed and pre-determined ending is challenging but necessary for the “experts” to be allowed to have their own hypotheses intact at the close of the session. This approach resists fixed endings and gives children the chance to “write” themselves into the action (Neelands, Citation1984, p. 49). To conclude this section, the social worker extended her thanks to the child psychologists for generously giving up their time and closed the meeting by promising to give them all an update on Katie in due course.

Developing strategies for dealing with dental anxiety

Creating the guidelines: to address the second aim of the research, in small groups the children were asked to come up with a set of suggestions that Katie might like to try to help her deal with her anxieties around having dental treatment. This discussion was facilitated by members of the research team but the children were encouraged to develop their own ideas in response to the brief of helping dentists create a set of “best practice” guidelines for treating children with dental anxiety. Each group’s responses were collated on large pieces of paper so that results could be shared, recorded and analysed.

Closing the circle

As with all participatory drama activities, ending the session with attention to the care and well-being of participants is critical (Thompson, Citation2015) and provides an important moment of reflection and appreciation of what has been contributed. With a sensitive topic such as dental anxiety, offering clear information, support and advice was an important factor. All the children were provided with a “goody bag” of toothbrushes, toothpaste and stickers before leaving the drama space and an offer extended to the classroom teacher for additional support or resources as appropriate.

Methodological and ethical challenges

Due to the nature of participatory work which has child-driven, creative exploration as its core principle, replicating the work in different settings is not achievable, nor desirable. Each school operates in its own context and presents a different set of particularities (for example, space, accessibility, resources, consent issues, familiarity with the topic and so on) that can impact on how the research is conducted. Each class has its own learning culture and each individual pupil has their own perspective and way of engaging with the work. This presents a challenge to researchers in terms of generalisability but can, with intention, be framed as an opportunity. For the RAPID project, adopting a multi-perspectival, inductive approach produced a wealth of rich data and nuanced insights into the problem under investigation that could not have been predicted.

There are logistical and operational challenges that accompanied the project that are important to acknowledge. First, when working with children the process of consent is always predominantly adult driven. For the team, this meant that not all children were able to participate in the research because parental consent had not been provided. The reasons for this were not always clear but this does raise questions about equity and inclusion that need further consideration. Secondly, standard research processes can be at odds with creative approaches. For example, the information sheet that accompanies the consent form outlined the central focus of the research but effectively took away any element of surprise when introducing the pretext for the drama. Children (and some adults) are keen to please and can be well versed in providing the “correct answers” for adults, leading to a degree of positive bias. The extent to which their responses were shaped by their compliance to a topic such as oral health is difficult to ascertain. Thirdly, working as a multi-disciplinary team was crucial to the design of the project but proved to be resource intensive, not least because of the initial lack of shared language and understanding of the pedagogies of process drama. Building trust within the team was time consuming but critical and helped create an environment where dental researchers felt sufficiently confident to work in role with the children. Similarly, although schools were enthusiastic to be involved, finding the time and staff to resource the project proved to be a barrier in some instances. Finally, the question of how to analyse the type of data produced through process drama requires further attention. The results outlined below were gleaned from transcripts of children’s discussions and verbal contributions to the workshop. How to analyse more creative responses, as expressed through the still image for example, is yet to be resolved.

Results

Following thematic analysis of the data, four key themes were identified: 1) Fear of the unknown; 2) Unpleasant sensory experience; 3) Society’s perception and portrayal of the dentist and 4) Learnt negative associations with the dentist. Within each theme, two sub-themes were identified as outlined below.

Fear of the unknown

Anticipatory fear of something unpleasant happening

Throughout the process drama, both the children and “Katie” expressed the view that attending a dentist appointment evoked a “fear of the unknown”, relaying that the main character of the drama was scared because “she doesn’t know what’s happening”. Much of this fear was anticipatory in nature with the waiting room environment acting as a prominent setting for such thoughts and feeling to emerge. Although there was a general fear of not knowing what was going to happen, the consensus was that potentially an unpleasant event was going to occur, though what specifically this unpleasant experience was going to be was not always vocalised, and thus appeared to reflect a more generalised loss of control and negative thought process.

Anticipatory fear of needing treatment

One possible perceived unpleasant event that might occur was the potential need for dental treatment. As one participant said, “Katie is afraid of the dentist because the dentist might take her tooth out”. Treatment was seen as potentially causing pain to the individual.

Unpleasant sensory experience

Environmental triggers for anxiety

The dental setting itself was deemed to be anxiety-inducing. It was seen as possessing a range of negative sensory attributes that acted as triggers for anxiety and fear. These triggers were based around all five senses. The sound, feel and taste of the dental environment were particularly prominent in creating this unpleasant experience. The sounds made by the operation of dental equipment, most notably the dentist’s drill, as well as the negative reactions of other dental patients vocalised through screaming (“may be that Katie could here [hear] people screaming”) were causes of anxiety. Whether these screams were elicited through dental treatment or fear, and whether the participants had personally experienced hearing patients scream, or this was merely an assumption or perception they had of visiting the dentist was not clear. With regards to taste and touch, this was focused on the actual dental examination of the mouth and teeth, with treatment being perceived as both painful and invasive. Overall, participants expressed a dislike for having the dentist’s fingers and instruments/materials in their mouth, particularly as this can be sometimes an unpleasant taste. This was also seen as an invasion of personal space and privacy.

Treatment perceived as painful and invasive

Participants expressed a fear of the dental instruments (“ … scared of the tools”) and certain dental treatments (“injections/fillings/teeth pulled out”) with these perceived as potential sources of pain and discomfort. “People get anxiety about it because they see them doing it and they don’t like needles because they think it like it could hurt you and stuff.”

Society’s perception and portrayal of the dentist

The authoritarian dentist

The dentist as an individual was consistently referred to as a key source of dislike (“Maybe it’s not her, like her thoughts about going to the dentist, maybe it’s this specific dentist that she goes to, and she doesn’t like him”) and fear (“So like if she’s like really scared of him she could call the NSPCC”) with a prevailing view that the dentist may be mistreating the patient. As one participant said: “Basically I think that she’s sort of, she’s getting like really like upset because probably it’s like that doctor is like doing something like bad behaviour to her, on purpose, and without her mum knowing.” In this respect, there were two dominant perceived dentist personas: the strict authoritarian and the nightmare villain. On one level the dentist was seen as a “rude” and “obnoxious” authoritarian whose role was to chastise and belittle the patients (“Katie might be afraid of the dentist because the dentist might make fun of her” and “ … they lecture you”).

The nightmare dentist

On another level, the dentist was seen as a nightmarish figure associated with a range of horror-inducing entities and actions. This latter fear-inducing representation of the dentist appeared to be commonly linked with the media’s horror-based portrayal of the dentist in both film and literature as a protagonist of evil who relishes inflicting pain on their patients.

Learnt negative associations with dentist

Previous negative dental experience

Similar to the anxiety and fear that can be produced through exposure to society’s negative media portrayal of the dentist, participants described how negative associations with the dentist could also be learnt through personal experiences and vicariously through significant others. The participants conjectured how the main character in the drama may have had a previous “bad experience” when visiting the dentist when she was younger, possibly involving an especially traumatic and/or painful treatment procedure that has left a lasting fear of the dentist that now presents as dental anxiety.

Modelling of dental anxiety

In contrast, the participants also conjectured that Katie’s dental anxiety could have been learnt through knowledge and exposure to her mother’s own dental phobia. Observing the negative thoughts, emotions and behaviours experienced by her mother in relation to the dentist and dental treatment both directly and indirectly could have modelled a pattern of behaviour perceived as an appropriate reaction to the dentist.

Results from the thematic analysis have been collated and expressed here as a layered, multi-perspectival “map” which includes not only the themes emerging from the analysis but the dramatic processes that prompted them (). The dramatic frame, that of being inside the waiting room, wraps around the findings and provides the given circumstances of the scenario under investigation. The four key elements of pretext and problem, character and role, strategies and solutions, imagination and play, sit underneath the results and should be considered as inter-connected aspects of the methodology adopted. While there are four distinct themes emerging from the data, there is significant overlap between them and more work is needed to determine how one theme or sub-theme might relate, contribute or lead to the experience of another.

Discussion

The results of the thematic analysis resonate with existing findings of children’s experiences of DFA (for example, Morgan et al., Citation2017). They support the view that one of the main reasons for dental anxiety is a fear of the unknown. Fear is often considered to be an essential and inevitable emotion, thus providing children with a means of adapting to the stresses of life (Chapman & Kirby-Turner, Citation1999). It is therefore normal for children to be afraid of new and potentially unpleasant experiences. However, dramatic distancing techniques employed in the workshop allowed the children to explore the experience of fear in different ways. Using the dramatic frame to observe, analyse and conjecture about the fear felt by a fictional other, provided a degree of “protection”. Using stylised movement, mime and gesture, the actor playing Katie conveyed the emotions of dental anxiety through demonstration and signification rather than giving any attempt at naturalistic representation. Fear was not underplayed, avoided or ameliorated but rather represented in a way that could be observed, analysed and discussed from an objective standpoint. In their role as experts the children were able to act as advisors, mentors and consultants in the drama, drawing on their own understanding of Katie’s experience, positioning themselves not as children in a similar plight but as adults with professional knowledge.

The convention of the two-way mirror acted as both a physical and psychological distancing tool for close yet safe examination of the topic. The imaginary division meant action could continue in the fictional space of the dentist’s waiting room, the facilitator could speak in the role as a social worker without Katie “hearing” and participants could comment on her behaviour simultaneously. Close consideration of the dental setting gave rise to multiple perspectives as to what could be done to improve environmental factors.

An important part of the child dental experience is the interaction with the dental staff, yet this is a relatively under researched topic in terms of dental anxiety. In the current study, one of the main themes that arose was society’s perception and portrayal of the dentist. The children described the dentist as authoritarian or as a nightmarish figure and they linked the dentist’s behavior with the media’s horror-based portrayal in films and literature. These findings are similar to the systematic review by Zhou et al. (Citation2011) examining the impact of dental care professionals’ clinical behaviours on childhood DFA. Using abstract representation, in this case, still image, allowed the children to give room and shape to these horror-like aspects but in a controlled form. Working in an abstract register and in ensemble provided children with the means to express their fears together in a way that was not reliant on words but rather distilled thought and feeling into symbols, gesture and image.

At the heart of most drama lies a preoccupation with relationships. How the central character interacted with her mother became an important factor for the children in each workshop session and revealed the final sub-theme, the modelling of dental anxiety. A study by Locker et al. (Citation1999) showed that over half the participants who reported child onset dental anxiety had a parent or sibling who also suffered anxiety about dental treatment. This suggests that children can indirectly learn their anxious response to dental treatment by observing the behaviour of those around them. A further study exploring dental anxiety in children aged 5 to 9 by Tickle et al. (Citation2009) highlighted that dental fear and anxiety can be acquired through adverse conditioning, both directly through an early negative experience and vicariously through popular culture, family and friends. In the RAPID project the intersecting influences of culture (expressed through still image), familial bonds (explored through role play) and peers (enacted through ensemble) are examined in parallel. The dramatic mode provides space for all of these aspects to emerge and to be explored in a way that acknowledges the particularities of individual lived experiences.

Adjusting the set: new perspectives on oral health research and drama as a legitimate way of knowing

Dental anxiety is a major issue affecting children’s oral health and clinical management (Wu & Gao, Citation2018). Strategies to overcome dental anxiety are of paramount importance to improve children’s oral health and their experience of dental treatment as well as reducing the need for dental general anaesthesia. To develop appropriate strategies there needs to be a better understanding of the principal causes of anxiety from a child’s perspective. Finding ways for these perspectives to emerge is critical. In order to overcome DFA and other health-related anxieties experienced by children, we need to adopt research methodologies and practices that allow children to participate actively and safely in the inquiry that affects them directly. Process drama provides a framework for investigating a complex psychological issue through critical distancing techniques. The potency of the drama lies in our collective agreement that people, places and objects can transform for the duration of the play. By adopting a role that is different from our own we can become other. The children are no longer research subjects but experts situated at the heart of the investigation and emotionally invested in it. Through a collective act of imagination, we can transport ourselves to the dentist’s waiting room without physically being there. Drama allows us to take the research out of the physical dental setting and into a fictional world that can be experienced and navigated safely.

Employing drama practices to inform health research is always going to be contentious in some quarters. The type of knowledge it produces, and the methods it adopts to arrive at a point of knowing, is different from scientific research. It provides a different form of knowing that is not always generalisable. It is knowledge that is embodied and felt and therefore often difficult to put into words. Despite these tensions the landscape is changing. Arts education is now incorporated into some medical programmes, for example, at Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry and at King’s College, LondonFootnote5 and the National Centre for Cultural Value has identified health and well-being as one of its core research themes for 2020 (Centre for Cultural Value, Citation2020). While there is increased interest in collaborative working between the arts and health sciences, there is still some way to go in terms of establishing rigorous, qualitative, longitudinal methodologies that serve both disciplines. Using participatory action research with children presents further challenges due to questions around competence and capacity (Singh, Citation2007, p. 35). The status of children’s contributions is often compromised if they are deemed not to have the skills or the tools to function within a research context. Nonetheless, if we are to better understand a particular aspect of children’s lives, then it is imperative we find appropriate ways to enable them to communicate their views, share their experiences and participate in finding solutions to the problems that affect them directly. Process drama offers a unique response as it reframes children as “experts” within the investigation and reconfigures their status as co-researchers.

The RAPID project was designed as a pilot study and much more collaborative work is needed to make lasting methodological advances to the field. While the study involved only a small number of participating schools and is therefore relatively limited in scope, the approach has provided rich data that reveals new insights about the causes of dental anxiety in children. The dramatic framework allowed children to express complex ideas and feelings in ways that other methods such as focus groups, questionnaires and interviews could not achieve. Unlike these other approaches, however, participatory drama processes can never be precisely replicated, which will invariably produce some variance in results across participating groups. The collaborative nature of process drama means that responses may be shaped by the peer group or other people present. Some children may be unwilling to contribute ideas in a public setting or feel unduly influenced or led by other members of their peer group. However, this study has demonstrated that these limitations can be overcome with skillful facilitation and that some tolerance of variance is to be embraced when working in this way. What Zahra calls the “pluralism and subjectivity” (Zahra, Citation2017, p. 147) of the arts and humanities provides a more nuanced understanding of patient experience. Drama deals with the complexities, paradoxes and conundrums of human existence and is therefore capable of revealing new insights that can be put to use in clinical settings.

The implications of this research for paediatric dentists are clear. The causes of dental anxiety in children are complex and therefore a better understanding of the causes of DFA is essential in order to improve dental care and management of children. This is a novel, interdisciplinary and socially engaged approach that involves children actively in an exploration of the causes of DFA. Furthermore, adopting process drama techniques in health research is particularly helpful in developing answers to public health issues as it is inclusive and transcends health literacy barriers. Process drama has been a staple component of the drama teacher’s toolkit for decades. Educators and practitioners have long recognised its qualities for promoting and prompting embodied critical thought and ethical inquiry through the dramatic frame within the classroom. However, its application as a participatory research methodology appropriate for addressing health problems related to anxiety in children has not yet been fully developed. This cross-disciplinary collaboration provides a challenge to the usual paradigms of knowledge construction in health research and makes a case for placing children at the centre of a research process where they are able to act as experts in their own lives.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Natasha Berg (MA Applied Theatre and Intervention) and Mohammed Malik (MChD/BChD, BSc) who were employed as interns for the duration of the RAPID project. We would like to thank alumni and friends of the University of Leeds for supporting this research via the Footsteps Fund. We thank the staff and pupils from Schools in RAISED in Yorkshire [Research Activity In Schools Evaluating Dental health] that took part in our study [Healey Primary School, Field Lane School and Batley Grammar School]. The research was supported by NIHR Leeds Clinical Research Facility. We would also like to thank the SMILE AIDERS Patient Public Involvement Forum for contributing to the research design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The acronym RAPID stands for Rehearsals And Performance In Dentistry. The project was supported by the Footsteps Fund at the University of Leeds and was developed as a cross-Faculty student enhancement and schools’ engagement programme. Staff and students at the School of Dentistry and the School of Performance and Cultural Industries have been collaborating since 2015. The RAPID project is one of the projects aimed at developing participatory drama methodologies for the purposes of oral health research and dissemination.The study was conducted following ethical approval by the Dental Research Ethics Committee of the University of Leeds, reference (090119/JT/268).

2. RAISED in Yorkshire (Research Activity In Schools Evaluating Dental health) is a community collaboration between the School of Dentistry at the University of Leeds and Batley Girls‘ High School. It aims to enhance public engagement to reach and involve under-represented, at-risk young people to provide exposure to oral health research they value and which is important to their community.

3. See Neelands and Goode (Citation1992) for a detailed description of each conventions and how they might be applied.

4. This technique is suggested by Cecily O’Neill in Mystery Pictures scheme of work that features in Drama Structures (O’Neill & Lambert, Citation1990: 161).

5. “Performing Medicine” is a creative training programme for healthcare professional and students run by Clod Ensemble. This programme has been delivered at Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry as well as at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. At Kings College London, interdisciplinary approaches to clinical education are being developed with the arts and humanities embedded in dentistry education within the Faculty of Dentistry, Oral and Craniofacial Sciences (see Zahra, Citation2017).

References

- Armfield, J. M., Stewart, J. F., & Spencer, A. J. (2007). The vicious cycle of dental fear: Exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health, 7(1), 1–1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-7-1

- Baim, C., Brookes, S., & Mountford, A. (2002). The Geese Theatre handbook: Drama with offenders and people at risk. Waterside Press.

- Bolton, G. (1996). Drama as research. In P. Taylor (Ed.), Researching drama and arts education (pp. 187–194). Falmer Press.

- Bolton, G. (2006). A history of drama education: A search for substance. In L. Bresler (Ed.), International handbook of research in arts education (pp. 45–61). Springer.

- Chaki, S., & Okuyama, S. (2005). Involvement of melanocortin - 4 receptor in anxiety and depression. Peptides, 26(10), 1952–1964. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2004.11.029

- Chapman, H. R., & Kirby-Turner, N. C. (1999). Dental fear in children – A proposed model. British Dental Journal, 187(8), 408–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800293

- Cianetti, S., Lobardo, G., Lupatelli, E., Pagano, S., Abraha, I., Montedori, A., Caruso, S., Gatto, R., De Giorgio, S., & Salvato, R. (2017). Dental fear/anxiety among children and adolescents. A systematic review. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 18(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23804/ejpd.2017.18.02.07

- De Coursey, M. (2018). Embodied aesthetics in drama education. Bloomsbury.

- Eriksson, S. A. (2011). Distancing at close range: Making strange devices in Dorothy Heathcote’s process drama teaching political awareness through drama. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 16(1), 101–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2011.541613

- Fuentes, D., Gorenstein, C., & Hu, L. W. (2009). Dental anxiety and trait anxiety: An investigation of their relationship. British Dental Journal, 206(8), E17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10/1038/sj.bdj.2009.253

- Heathcote, D., & Bolton, G. (1995). Drama for learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s mantle of the expert approach to education. Heinemann.

- Heathcote, D., Johnson, L., & O’Neill, C. (1991). Dorothy Heathcote: Collected writings on education and drama. Northwestern University Press.

- Klingberg, G., & Broberg, A. G. (2007). Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in children and adolescents: A review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 17(6), 391–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00872.x

- Locker, D., Liddell, A., Dempster, L., & Shapiro, D. (1999). Age of onset of dental anxiety. Journal of Dental Research, 78(3), 790–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345990780031201

- Morgan, A. G., Rodd, H. D., Porritt, J. M., Baker, S. R., Creswell, C., Newton, T., Williams, C., & Marshman, Z. (2017). Children’s experiences of dental anxiety. International Journal of Paediatr Dent, 27(2), 87–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12238

- Neelands, J. (1984). Making sense of drama: A guide to classroom practice. Heinemann Educational Books.

- Neelands, J., & Goode, T. (1990). Structuring drama work: a handbook of available forms in theatre and drama. Cambridge University Press.<img src=“„ alt=“„ class=“iCommentClass icp_sprite icp_add_comment chk-comment iCommentExist„ data-username=“Alice O'grady„ grady'=“„ data-userid=“96757„ data-content=“The Neelands and Goode Reference should be 1990. This needs amending in the text. I clicked 'resolved' by mistake and can't undo it. „ data-time=“1614594066575„ data-rejcontent=“„ data-cid=“76„ id=“Mon Mar 01 2021 10:21:06 GMT+0000 (Greenwich Mean Time)„ id0=“76„ data-username0=“Alice O„ data-userid0=“96757„ data-content0=“Check Tagging“ title=„The Neelands and Goode Reference should be 1990. This needs amending in the text. I clicked 'resolved' by mistake and can't undo it. “ data-radio=„xmlradioYTS“ data-userid-id2=„96757“ data-username-user2=„Alice O'grady“ corr_ord_id=“97„>

- Norris, J. (2000). Drama as research. Realizing the potential of drama in education as a research methodology. Youth Theatre Journal, 30(2), 122–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08929092.2016.1227189

- O’Neill, C. (1991). Structure and spontaneity: Improvisation in theatre and education [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Exeter.

- O’Neill, C., & Lambert, A. (1990). Drama structures: A practical handbook for teachers. Stanley Thornes.

- Porritt, J., Buchanan, H., Hall, M., Gilchrist, F., & Marshman, Z. (2013). Assessing children’s dental anxiety: A systematic review of current measures. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 41(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00740.x

- Singh, I. (2007). Capacity and competence in children as research participants - Researchers have been reluctant to include children in health research on the basis of potentially naive assumptions. Embo Reports, 8(S1), S35–S39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401018

- Somers, J. (2002). Drama making as a research process. Contemporary Theatre Review, 12(4), 97–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10486800208568698

- Thompson, J. (2015). Towards an aesthetics of care. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 20(4), 430–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2015.1068109

- Tickle, M., Jones, C., Buchanan, K., MILSOM, K. M., BLINKHORN, A. S., & HUMPHRIS, G. M. (2009). A prospective study of dental anxiety in a cohort of children followed from 5 to 9 years of age. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 19(4), 225–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.00976.x

- Willet, J. (Ed. & Trans.). (1964). Brecht on theatre: The development of an aesthetic. Methuen. (Original work published 1964).

- Wu, L., & Gao, X. (2018). Children’s dental fear and anxiety: Exploring family related factors. BMC Oral Health, 18(1), 100–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0553-z

- Zahra, F. (2017). Learning to look from different perspectives - what can dental undergraduates learn from an arts and humanities-based teaching approach? British Dental Journal, 222(3), 147–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.109

- Zhou, Y., Cameron, E., Forbes, G., & Humphris, G. (2011). Systematic review of the effect of dental staff behaviour on child dental patient anxiety and behaviour. Patient Education Counseling, 85(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.002