ABSTRACT

Background

There is an increased interest in the role artists can play in care for older people. This momentum comes with the need to closer investigate the nature of boundary work of creative professionals in arts and health projects.

Methods

We conducted a responsive evaluation to provide a thick description of the boundary work involved in ENCOUNTER#9, an intergenerational arts project taking place within an older person care setting.

Results

Boundary work proved to be rewarding, yet messy and unruly. Although the lead artist had carefully planned and prepared the project and gained a broad commitment, not everything went according to plan. This led to friction and all involved put effort into adjusting goals and expectations.

Conclusion

We add to the conceptualisation of boundary work in arts and health by showing that it takes place on different levels: personal, relational, organisational and public.

Background

Many artists are using their skills in older person care settings. A growing body of research shows the benefits of arts practice on the health and well-being of older people (Bradfield, Citation2021; Curtis et al., Citation2018; Cutler, Citation2019; Fancourt & Finn, Citation2019; Fraser et al., Citation2014, Citation2015; Groot et al., Citation2021; Liu et al., Citation2022). This has created momentum for the role of arts in ensuring good care for older people. Besides the positive effects on older people, the idea that artists can contribute to policy making, such as global health policy, has also risen in the past years (Armstrong et al., Citation2014; Fafard, Citation2020). This momentum comes with the need to closely investigate the necessary conditions for the cooperation between arts and health to be successful.

Some researchers in the field of arts and health have looked into issues considering the development and delivery of arts-based practices in older person care (i.e. Broome et al., Citation2019; Fancourt, Citation2017; Huhtinen-Hildén, Citation2014), however, few have specifically used boundary work as a framework for investigating these practices. This study examines boundary work in arts and health: the often invisible work needed to realise the cooperation between health- and social care and artists (Daykin, Citation2019, Citation2020). The study looks at boundary work taking place during ENCOUNTER#9, which we approach as an arts-based practice in the setting of long-term older person care. We refer to this project as a social design project, as the lead artist on the project, Joost van Wijmen (JvW), calls himself a social designer. The term “social design” is used to describe a range of social activities taking place across many different fields, such as health care and international development (Armstrong et al., Citation2014). It encompasses using participatory approaches to “make change happen towards collective and social ends, rather than predominantly commercial objectives” (Armstrong et al., Citation2014, p. 15). The activities taking place during ENCOUNTER#9 were designed by JvW through a participatory process. These comprise of meetings between students of social work and older residents of a care organisation, during which they jointly work on creative assignments. JvW is the lead artist in this case study. When we refer to artists in this study, we refer to experts who have acquired professional training or significant working experience in a creative profession, such as (social) design or any other form of art. Throughout this article, we use the terms designer, artist, or creative professional intermittently because these terms were used by participants and the artist himself throughout the organising of the project, depending on the context.

Boundary work, coined by Star and Griesemer (Citation1989), has been deployed as a sensitizing concept within many academic studies to examine how collaboration between actors from different domains is established and maintained (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011; Daykin, Citation2019; Duijn van, Citation2022; Hsiao et al., Citation2012). Boundaries as phenomena can be symbolic or physical. Symbolically, they are a conceptual way to categorize objects, people, practices, professions, traditions or beliefs. Boundaries also entail potential tensions, difficulties or obstacles for interaction across pertained differences (Duijn van, Citation2022; Hsiao et al., Citation2012). Simultaneously, they represent potential valuable points of collaboration where learning, innovation, transformation and meaning-making takes place (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011).

In the field of arts and health, researchers have indicated the importance of crossing boundaries in knowledge building and research methodology (Daykin, Citation2020; Koivisto, Citation2022; Laukkanen et al., Citation2022; Yoeli et al., Citation2020). Due to the increased specialisation in health care and the risk of fragmentation, boundary work is needed within this field to “highlight shared concerns, encourage collaboration and help to bring about change and innovation in policy and practice” (Daykin, Citation2020, p. 63). Furthermore, Koivisto (Citation2022) indicates boundary work in arts and health has potential value, as professionals may gain access to previously unknown resources. Boundary work is an inherent feature of the job of many artists working in other than cultural or artistic settings. However, very little is currently known about the nature of the type of work it takes to work at and across these boundaries. Research that empirically explores the experiences of artists as boundary spanners is scarce (Daykin, Citation2019; Koivisto, Citation2022). In this article, we contribute to the conceptualisation and embodied knowledge of the messiness of boundary work in arts and health by using a combination of qualitative and arts-based research methods. Messiness emerges at the crossroads of arts and health, because old ways of working are under pressure and new understandings are not yet in place. Cook (Citation2009) explains that such mess has a purpose, namely to reframe one’s practice and develop new understandings of one’s practice.

Research approach

The goal of the research project was initially twofold: on the one hand, gaining insight in experiences of participants during a case study of arts-based practice within the setting of older person care, ENCOUNTER#9 (see Appendix A for an elaborate project description) and on the other hand, to investigate the nature of boundary work of creative professionals in arts and health projects. This article reports on the second goal of the study.

During the research project we carried out responsive evaluation in combination with arts-based research. In responsive evaluation, the perspectives of all those involved are engaged in a dialogue to reach a mutual understanding of their experiences of the project. This approach’s strength lies in its ability to incorporate diverse perspectives, providing a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter (Abma, Citation2018; Abma & Stake, Citation2001; Abma et al., Citation2017). We chose responsive evaluation as the approach for this study because it offers valuable insights into participants’ varying experiences and their engagement in boundary work throughout the project. In this research project, we combined responsive evaluation with arts-based research as this enables deeper insight and allows to acquire a “felt” sense of what boundary work looks and feels like in practice. Arts-based research is grounded in an epistemological foundation for human inquiry that applies artistic forms for understanding and representing the worlds in which the research takes place (Knowles & Cole, Citation2008). The underlying epistemological stance is that art can create and convey meaning and has meaning in and of itself. It is considered a rich way to access experiential knowing (Knowles & Cole, Citation2008; Leavy, Citation2020).

Below we describe the different methods used to collect data. The research design was emergent, and the data collection and analysis were done iteratively to gain an in-depth understanding of the boundary work performed in the case study. The data from various sources, perspectives and different modes of knowledge (verbal, written, observed, visual) allowed for data and methodological triangulation (Abma & Stake, Citation2014).

Participants

The social design project was already scheduled to take place, when the research team joined the lead artist and they jointly decided the project would be an interesting case study for gaining insight in boundary work in arts and health. Older participants agreed to take part in the social design project after explanation about the project by either the lead artist or one of the care staff involved in the project. Students voluntarily enrolled to be a part of the project, either as part of their standard learning activities, or as extra-curricular project. All participants in the project were also asked to take part in the study. Therefore, the participants of the study involved older people who were residents or visitors of two different care organisations in The Netherlands (n = 13), first-, second- and third year students social work from two different education institutes (n = 20), teachers from the two institutions (n = 4), a member of care staff, a manager and a wellbeing co-ordinator from the two care organisations (n = 3).

Ethics and consent

During the first meeting with both older people and students, the first author (LK) was present explaining that research would take place during the social design project. The medical ethical research committees of the care organisations Topaz and Vitalis approved the research protocol. Written consent for participation in the research project was obtained from the students as well as the older people. Throughout the project, the researchers and the lead artist were careful to obtain consent for every new step, such as recording and transcribing interviews and focus groups. The participants were informed that they might be recognisable in the data, as in these types of research projects with partially artistic outputs, it is difficult and not desirable to completely anonymize the data, as participants want to be recognised for their contribution (Boydell et al., Citation2011).The data mentioned in was anonymized. As the research design emerged and arts-based methods were increasingly applied, separate consent was obtained for taking photographs and the use of the photographs for academic publication.

Table 1. Overview of gathered data.

Data collection

A combination of methods for data collection was used as part of the responsive evaluation. These are described in .

As part of the arts-based research considering boundary work during the project, artist JvW conducted auto-ethnographic journaling (Bochner & Ellis, Citation2016). He produced a personal journal in which he reflected on his internal considerations and ethical dilemmas during and after ENCOUNTER#9. This journal was kept from January 2021 until September 2022 (n = 40 entries). From analysing these journal entries, the idea emerged for JvW to start using arts-based methods to develop and further deepen knowledge about his experiences as a boundary worker. His background in costume design offered a method to create a costume and object representing his experience as a boundary worker. He let himself and his designs be photographed in the older person’s care setting where ENCOUNTER#9 took place. This material was used in dialogue with the other authors of this article and experts at the Dutch Design Week. The Dutch Design Week is a yearly 9-day event in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, surrounding all aspects of design. It is the biggest event of its kind in Northern Europe, showing the work of more than 2600 designers. The photos provide artistic knowledge or “felt knowing” (Haberl, Citation2021). These photographic reflections assist in gaining in-depth, sensible knowledge and understanding of the invisible, unspeakable qualities of boundary work.

Data analysis

LK and BG conducted ongoing thematic analyses of all research material through open coding using MaxQda (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2019). Throughout the study, careful attention was paid to quality criteria for qualitative research (Frambach et al., Citation2013), such as using multiple data sources, prolonged engagement in the case study, carrying out regular member checks with stakeholders and the lead artist in the project. Besides, the lead artist and two representatives of the stakeholders involved in the project are co-authors of this article, which ensured the described findings and interpretations thereof were continuously checked by them. Triangulation of different collected data was a continuous process of putting the data together, reading, observing, listening to each other’s findings and discussing the research process within the team of authors.

Results

The results uncover, describe and provide an artistic reflection on the nature of the boundary work of an artist in the field of arts and health. We start from the artist’s perspective, incorporating the voices of the people and organisations he was working with. For readability, we talk about JvW in the third person, even though he is an author, the same goes for AN. She was involved in the project as a teacher and researcher.

The designs

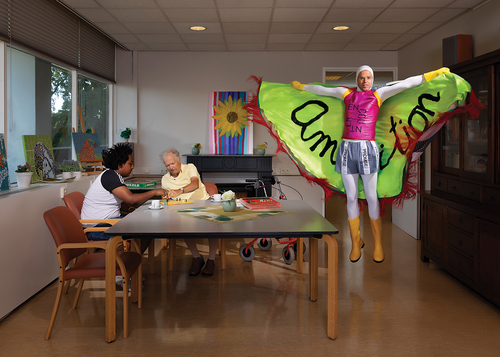

Design 1: the superhero

For this costume (see ), Joost was inspired by the superhero’s character. In conversation with Joost about his reflections on himself as a boundary worker and the artistic choices evolving from this reflection, we can identify many aspects of the boundary worker as described in the literature. Joost describes himself as a “fremdkörper”, which resonates with the idea of the boundary worker as having an in-between position: Not fitting in the field of older person care he is trying to work in, but also not being at home in his field; he is crossing boundaries and combining fields (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011). Joost also describes a humorous, almost ridiculous way in which an artist is wanting to work in a healthcare setting might be viewed there. Therefore, he states he used artificial materials and loud colours, which are “anti-boring, slightly provocative and opposing to the warm, soft feeling which the care world evokes in me”. The costume represents a low status, a character that was trying, but failing, a hero, and at the same time, a (possible) zero. Furthermore, part of the costume was made of donated materials from participants and other project stakeholders, meaning Joost could not do this alone. This is boundary work at the personal and relational level.

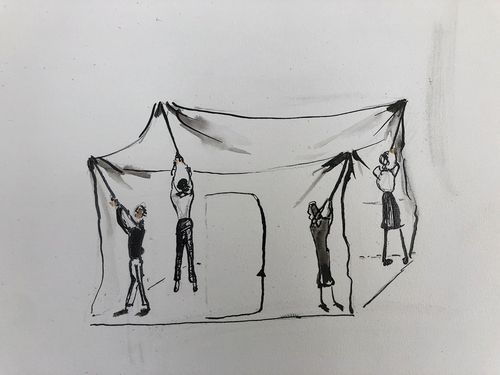

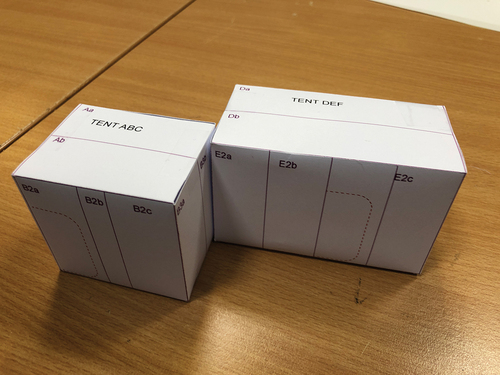

Design 2: the structure

The second design Joost made (see ) consists of two white, semi detached tents. For Joost, they represent the organisational, systemic level of boundary work. It shows that you need to relate to a care system as an artist. Joost measured the offices of a manager and a member of staff of the daycare centre where ENCOUNTER#9 took place. These offices were copied in their real size in Tyvek, a paper-like textile fabric of which normally surgery clothes or single-use safety clothes are made. Joost deliberately chose to work with this fabric as it is light, connected to care supplies and not very durable. To him, this stands for the ephemeral and constantly changing nature of organisations and systems. Ideally, four people must hold the structure up (see ). However, in the case of older person care, there are always shortages in staff and time, so there is rarely the number of people available to perform the work as it is meant. The design makes visible the situational nature of boundary work and how all actors involved have to relate to boundaries shaped by wider structures surrounding them (Duijn van, Citation2022, p. 5).

The photos

The promise at the start

In the first photo of the series, Impeccable Ambition (see ), we see Joost jumping in the air, happy and full of ambition, as written on his cape. It looks like Joost is landing in the care organisation: the superhero who will save the day. At the same time, we see two participants, a student and an older person. They are ignoring Joost and playing Ludo together.

In the second photo of the series, The Art of Caring (see ), we see the structure Joost designed on the patio of the care organisation. It looks strange, out of place. You need enough people with the right skills and knowledge to keep it upright. The structure is not held up right here; it is wonky and almost falling apart.

These first pictures represent the hopes and dreams of the designer and all the partners projected onto the project, ENCOUNTER#9. The photos show promise, excitement and a sense of mystery, abstraction, something yet unknown. At the same time, it represents that the starting point of ENCOUNTER#9 did not lie with the people whom all these partners are working for: The older people and the students.

At the beginning of the project, Joost had conversations and meetings with all of the partners; starting with the funding bodies, head of board and management levels of the education- and care organisations, and then filtering to the specific managers of departments where the project would take place, teachers he would be working with and eventually, the older people and students who were going to participate. During this process, relational boundary work had to be carried out by all of those involved. Important for Joost was to address the theme of the body and how people experience it, how it shapes their identity. He wanted to design encounters between young and old, which were reciprocal and would generate unexpected, profound, human moments of interaction. Besides Joost, many different partners influenced the goals for ENCOUNTER#9. Funding bodies, for instance, demanded the project to be scaled up. Educational and older person care institutions had their own goals, which became partly evident in conversations with the teachers and care staff prior to the start of the project. However, some of these goals were only made explicit in evaluation sessions at the end of the project.

Boundary work proved to be messy, unruly and yet at times rewarding and inspiring. Although the artist had nicely planned and prepared the project, not everything could be controlled. An example of where boundary work got messy is where the project eventually took place in the care organisation. Joost had designed and tested the project in a pilot for independently living older people. Yet, it was decided by the management of the new care organisation taking part in ENCOUNTER#9 that it should take place in a day centre for older people with somatic as well as cognitive impairments, despite Joost’s multiple requests for his original target group. The coordinating member of staff of the day centre in hindsight, stated in an interview: “I knew from the beginning that this project was going to be too difficult for my visitors, but nobody asked me anything, and Joost was such a great guy, I felt sorry for him, so I tried to make the best of it.” So, she seemed to have no idea why “they” (management) had picked her department, but she also did not feel like she had anything to say in the matter. She was stuck with the project and had to make the best of it.

The day centre coordinator was clear about the project’s impact on her visitors: “They did not really benefit from it. There was too little continuity, people and students being ill or not showing up, so they could not really form a relationship.” She still made a great effort, though, to make the project work. In her field notes, LK noticed the coordinator was constantly trying to “rescue” the project as it were, by trying to convince her visitors to take part or making sure the students had at least some older people there to meet. She also regularly stated she was trying to make the project work “mainly for Joost”. The importance of relational boundary work becomes clear here: To make the project work, Joost had to make sure his working relationship with the daycare centre coordinator was smooth and productive. This seemed to be the case, as she was trying to make the project work for him and she said she enjoyed the collaboration with him. However, she did not do this for the benefit of her visitors. Therefore, Joost and the coordinator were struggling and trying to work around decisions on an organisational level.

Boundary work thus involved jointly setting goals and intentions for a project. What becomes clear from our findings are the frictions between personal, relational, and organisational goals and expectations. The people at the top layers of organisations had different expectations than those in the day-to-day running of the project. In one of his journal entries, Joost describes himself as a sailboat, trying to navigate the constantly changing winds from different directions to keep moving forward. Sometimes this can cause him to lose sight of what would be the good thing to do, for the people he is organising the project for in the end. He also felt uneasy that the project sometimes seemed to become about him and his expectations instead of all those he was working with. He wrote in his journal: “Am I just giving the day centre coordinator more work, and for what, because she wants to take care of me?!”

Things don’t go to plan

In the third photo of the series, Failing (see ), Joost sits at the table, sulking. Next to him, two participants are enjoying a game together, paying no attention to him.

In the third photo of the series, Trying in vain (see ), Joost is standing outside the tent structure. He is holding it up from outside. There are two women visibly standing inside the tent. Their faces are invisible. They are the coordinator of the daycare centre and a teacher who guided the students during ENCOUNTER#9.

These photos show Joost’s feeling that the project has failed. The game Ludo is called “Mens Erger je Niet” in Dutch (“Human, don’t be annoyed” in English). This title seems a perfect fit for Joost’s feelings. As he reflected: “Playing a game of Ludo together, do you really need a design project for that?!” This did not live up to Joost’s expectations of creating profound, meaningful encounters. The women inside the structure are trying to keep the partly collapsing structure up. They cannot see anything. Despite their inability to see each other, the three people in the picture are trying to hold up the structure together, which implies a common goal. Unfortunately, there are not enough people to hold the tent completely upright. Joost invited all people directly involved in setting up ENCOUNTER#9. Most of them were busy or had other reasons for not being there. A representation of how these types of projects sometimes go in real life; a few people feel ownership, who are actually physically holding the structure up and others are absent due to illness or more urgent activities.

These last two pictures show that things are not going to plan. There was an ambition for ENCOUNTER#9. There were two new target groups compared to previous projects. The booklets with instructions, offered in a gift box as part of the method from previous projects, did not translate well to these new target groups. From day one it became clear that the booklets would be put away during the meetings. A student states: “I used that box once, it’s now lying somewhere on top of the closet. Because it was, so to speak, too complicated for the people who were there.” The students preferred playing games or listening to music with older people. This meant that the layer of uncomfortable subjects, existential questions and Joost’s aesthetic ideas behind the project surrounding the body and identity, more or less disappeared, as the students, teachers, older people and care managers may have needed more guidance for this. During participant observations, one of the teachers noted that the curriculum she had to work with lacked time to teach basic knowledge and skills on approaching the day centre’s older people. Students had no knowledge about dementia for instance, which many of the older participants had a beginning form of. After a session, one of the older participants stated: “These girls don’t really seem to know what they are doing here. For a real conversation, we would need more guidance.” The students seemed to have no clear idea of what was expected of them, as one of them stated: “ … what is the thing we need to accomplish? Because we kept on hearing we were doing a good job, we did not know the goal and what we were supposed to get out of it.”

In a halfway evaluation between Joost and the two teachers guiding the project, Joost tried to explain why, as a designer, he found it interesting to investigate the changing body and to think of exercises that put the students and older people out of their comfort zone. This had been possible during previous projects because Joost had used his personal skills as an artist and teacher to guide the students and older people through these topics. However, in ENCOUNTER#9, he was meant to scale up and take a step back. In that same conversation, the teachers stated the focus on the changing body was new to them, and they had been mainly focused on the encounters between generations. The teachers had just experienced some sessions in which the students were struggling, trying to find a way to connect with a target group they hardly knew. For the teachers, this uncovered the basic knowledge and skills their students were lacking. They saw the expectations of ENCOUNTER#9 were ten steps too far. So they adjusted their goals and found it more important that the students would be able to engage in activities which would enable them to learn something during their time in the project, for instance how to engage with older people with beginning cognitive impairments. At the same time, these types of practical projects were important for the teachers, so they said, because it enabled them to connect with their students outside of the classroom. They stated it was easier for the students to learn something, if the project fit in with their skills, knowledge and their experiences. The teachers were also working within an organisational context: There was a set curriculum, which required them to work on set assignments with the students during the project, such as developing their professional attitude or passing practical exams concerning quality of care. These assignments had nothing to do with the changing body. When Joost gave in and said “Ok, maybe we need to let go of this idea of the changing body,” one of the teachers sighed with relief and in a reflex shouted “Yay!” So, boundary work was a continuous, situational process of finding joint goals, checking whether these goals remained the same, and adjusting where necessary. These types of ongoing evaluations were key for navigating emerging frictions, while at the same time being able to keep an eye on unexpected rewards of the collaboration between for instance Joost and the teachers.

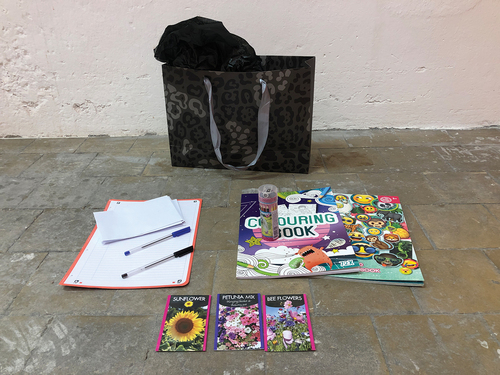

Eventually, the teachers and students designed their encounters, with gift bags containing customised activities for each day centre visitor. The students assembled their giftbags with prefab, purchased items (see ). For Joost, this required him to engage in internal boundary work: as an artist, he did not regard this type of material as in line with his ideas about aesthetics or suitable products. However, he was also an artist working in a participatory project, so he needed to carry out boundary work, reflect on himself and gain insight in where he might be judging or biased and take into account the aesthetic values of the students and their view on what they thought would be suitable for them and the older people. The students and the teachers were very proud of what they had achieved together and felt that they could “help Joost”, because his original design, in their view, simply did not work for them nor the older people of the day centre. As the teachers reflected, this was an unexpected positive outcome: The students were empowered to use their practical wisdom to design their own encounters.

From personal to public

In the fifth photo of the series, My Problem with Design (see ), we see Joost in the back of the room wearing his superhero costume and a mask, which narrows his sight. Two participants are reading a book, another resident is sitting in a chair, looking ahead, not noticing Joost. The superhero is out of place in this setting. He is standing powerful and ready to help, but whom is he helping?

The final photograph in the series is Tropical Surrender (see ). Joost, in his journal: “We give up, we let it happen, the hood is off, I’m (almost) walking away. A teacher is looking at me from a fallen-down structure. The magic has been broken.” The structure has collapsed, leaving only one person standing inside, holding a tiny part, the others have left. This person is one of the teachers who worked hard on the project and saw many positive outcomes, in fact she called it “the highlight of my week”, as she was so inspired by the way Joost approached working with the students and older persons. She is still looking expectantly at Joost.

The findings show that an important aspect of boundary work in arts and health projects is public boundary work. This entails how the work that is being done on a micro level, during the actual project, in the meetings with the students, older people, care staff and teachers, finds its way into the world and the public debate. Joost is especially passionate about this, often presenting his projects at big public events like the Dutch Design Week. This is part of how he views his social responsibility as an artist:

Through ENCOUNTER projects, I gather stories and information about the participants. For this I use a sensory experience and translate the stories into material (such as photos, drawings or texts). This information is relevant to those directly involved, including “the care sector”. Additionally, the stories are a mirror for the social debate. This is valuable for the participants as well as for our society because of the awareness that is raised.

Joost had to decide, together with the people involved in the project, how to get the word out about ENCOUNTER#9. Here we see friction between Joost’s feelings about the project and its impact on, for instance, the teachers and students. During an evaluation session, Joost said he was planning on framing the project as a “failed” project, as we see in some of the photos in this article. This caused a great sense of unease and annoyance among the teachers. Their goals for the project had been different, they avowed. They had to ensure their students remained involved throughout the project; showing up, for some of the students, was already a big challenge, but they did show up and were incredibly involved, motivated and felt ownership of the project. As one of the students put it: “Joost has learned a lot from us too!” Besides, the teachers stated they had been inspired by the project, learning about new, creative ways of working that they could incorporate in their lessons and forming a connection with their students. Framing the project as a failure, would disregard all of these positive experiences. These outcomes were collateral and unexpected. Joost reflected in his journal:

The project failed when I looked at it in the narrow terms of my professional identity and my previously formed ideas of artistic standards. I felt like when I walked away or took a step back, the “art” in the project went away. However, I see too that what was left can be regarded as meaningful in its own way. There were beautiful experiences; students worked together, the teachers formed great relationships with the students, one of them was even very touched when she saw the photos for this essay, her student playing the game with the older man. Those are no doubt moments which have an aesthetic quality, a sense of the profound, in them.

The narrow mask Joost made himself wear in the picture, stands for the narrow view he had on what he might regard as impact of the project.

Eventually, in agreement with all involved, the project was presented at the Dutch Design week. The presentation here showed Joost’s superhero costume design and some of the photographs (see ). At this event, a discussion session was held about failing as a professional in arts and health. The session was visited by a broad range of experts from health care, arts, research and education (n = 30). The photos were used as a conversation starter. Personal, as well as organisational questions, were discussed here, such as: “Have you ever felt like you failed in your professional life? How do care, arts and educational organisations facilitate failure, and what do they do to support processes around failure and learning from failure?”

Arts in health projects are inherently suitable for addressing the public. Besides boundary work taking place on a personal, relational and organisational level, this public aspect of boundary work is therefore important to address, and requires work from all involved. This work entails finding common ground in the stories, questions or images being put out into the world as a result of everyone’s efforts, or navigating frictions in different experiences, which of these will be put out there, with which intentions and in what way. This arts in health project was very elaborately documented, and therefore provided boundary objects (the costume design, photographs and this article), which can contribute to debates and reflections on boundary work in arts and health, but, so it turned out, also broader debates such as the facilitation of failing within the different fields and discussing the potential rewards and joys of boundary work.

Discussion

Prior studies have noted that, as there is momentum and increasing recognition of the benefits of cooperation between arts and health, there is a need for empirical studies on boundary work in this field to examine the nature of this type of work and how actors establish and maintain collaboration across domains (Akkerman & Bakker, Citation2011; Daykin, Citation2019, Citation2020). Such findings can be useful for actors representing the health- as well as artistic sector, and could for instance contribute to the development of policy and education considering the co-operation between the arts and the health care sector.

The present study provides further conceptualisation and embodied knowledge of boundary work in arts and health projects, from the perspective of an artist and those he was working with. The findings show that goals set in projects where boundary work takes place, often need to be re-evaluated, and expectations and desired outcomes can change throughout the process. In this study we saw that the requirement to scale up the activity and including more settings, changing the network of boundary relations surrounding the project, caused many frictions but also unexpected rewards. This is an important insight regarding policy direction in arts and health. Previous studies mostly overlook this changing nature of goals and expectations, the challenges that arise when scaling up projects, and the need to navigate these as a boundary spanner constantly. Working with these changes requires attentiveness, flexibility, empathy and time for critical (self-)reflection. Therefore, stakeholders must reserve time for these processes and keep finding moments to check in with the beneficiaries and stakeholders throughout the process. This is in line with Daykin’s (Citation2020, p. 65) indication that boundary work in arts and health is a slow process which requires time and perseverance.

The main finding emerging from the analyses presented in this study and the contribution this study makes to the current conceptualisation of boundary work in arts in health, is that the work has different layers, namely work on a personal, relational, organisational and public level. Firstly, by personal boundary work, we mean the work around internally experienced frictions. Different socialisation- and professionalization processes a person goes through in their life may cause them to want to set specific goals or perform their work according to certain values, which may be opposing and require constant internal debate and self-reflection. This is in line with Daykin (Citation2020, p. 65), who posits that boundary work often involves emotional labour (Hochschild, Citation2002). We see this emotional labour because boundary work has such a deeply personal, felt dimension. This requires relational boundary work. This work entails processes of verbal as well as non-verbal ways of attuning to the people you are working with. It requires navigating the (unspoken) expectations, values, interests or beliefs of all those involved, to create a new joint field of practice (Hsiao et al., Citation2012, p. 466). Thirdly, organisational boundary work comes in; as a creative professional you must relate to all the different ways in which people organise themselves, organisations and systems, which all have their customs, practices, epistemic traditions, power structures and historically grounded values (Duijn van, Citation2022; Koivisto, Citation2022). Finally, this study adds a fourth dimension to boundary work: being aware of how boundary work relates to the public world. The fact that the outcome of the work is presented to a (specific) audience, often in a specific public context, is an inherent part of this work that needs to be negotiated. We call this public boundary work. Overall, although the different levels of boundary work overlap or are intertwined, this deeper insight into boundary work is useful for examining this work and developing the skills and knowledge necessary in the practice of arts in health projects.

The multiple research approaches used in this study, especially the arts-based methods, photography and journaling, contribute to the conceptualisation of boundary work in arts and health by empirically showing a complex, embodied practice which takes place on an individual as well as different contextual levels. It shows that processes surrounding boundary work take place within each person, every organisation and every system involved, and have the potential to reach a broader public and thus contribute to public debates about for instance quality of care, or in this case, the facilitation of failure within different professions. The research methods we applied and the findings they produced provided a way of coming close to the essence of this practice: The muddiness and personal, emotional complexity of boundary work. This is in line with research on the working mechanisms of arts-based research methods, which states that researchers using this approach create knowledge based on resonance and understanding (Leavy, Citation2020, p. 3). This means the findings provide other (future) creative professionals with the ambition to work in arts and health with a realistic sense of what boundary work might require of them and a felt sense of the sort of tensions, frustrations and challenges they might encounter in their field. At the same time, the photographs and stories in this study reveil the sometimes humorous, joyful and rewarding sides of boundary work.

The designs and photos produced can be viewed as boundary objects. So can this article, containing the voices, visions and stories of all those involved. With these objects, we endorse that boundary objects “both inhabit several intersecting worlds and satisfy the informational requirements of each of them” (Star & Griesemer, Citation1989, p. 393). Boundary objects can be used for joint reflections and contribute to debates in the arts and the healthcare sector (Groot & Abma, Citation2021). The findings show that these boundary objects can help highlight shared concerns and bring about change and innovation (Daykin, Citation2020).

Limitations and strengths

This study offers a thick description of one case study of an arts and health project, focusing on the perspective of the artist. The study took place within the context of the Dutch health care and cultural systems. These aspects may be perceived as a limitation. However, focussing on this one case study and understanding it from multiple perspectives provided in-depth knowledge we might not have gotten if we had included more projects in this particular study. The study design, method and the presented results reflect how complex and particular the boundary work is in arts in health projects. The same complexity applies to ensuring triangulation and systematic analysis of different data sets which are both traditional, qualitative data sets combined with arts-based outputs. Using such different methods was suitable for this type of research and the authors regard this as a strength of the study. Future studies could investigate the work of different artists and follow the perspective of actors from the health care sector in varying contexts and countries.

Conclusion and implications

In this article, we closely examined boundary work in arts and health by carrying out responsive evaluation and arts-based research. Through its detailed, embodied data collection and analyses, this article makes the messy and muddy reality of boundary work visible and sensible. It shows how collaboration can be tense, difficult and contradictory yet also allow for reflective, transformative experiences in which common ground is found. Analysing boundary work in this way is helpful for professionals carrying out arts in health projects, as the empirical data provides pointers towards the skills needed in these processes, such as reflection and empathy. We detailed how this work changed practices of both the creative professionals and the stakeholders involved. Boundary work takes place on different levels: personal, relational, organisational and public work. Distinguishing these levels sensitizes us to the complex nature of boundary work in arts and health.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants and stakeholders of ENCOUNTER#9, including the students and teachers of mboRijnland, Leiden and Avans Hogeschool, ‘s Hertogenbosch, the care staff, managers and older people of care organisations Topaz, Leiden and Vitalis, Eindhoven.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abma, T. (2018). Responsive evaluation. In B. Frey (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (pp. 1427–1430). Sage.

- Abma, T. A., Leyerzapf, H., & Landeweer, E. (2017). Responsive evaluation in the interference zone between system and lifeworld. American Journal of Evaluation, 38(4), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214016667211

- Abma, T. A., & Stake, R. E. (2001). Stake’s responsive evaluation: Core ideas and evolution. New Directions for Evaluation, 2001(92), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.31

- Abma, T. A., & Stake, R. E. (2014). Science of the particular: An advocacy of naturalistic case study in health research. Qualitative Health Research, 24(8), 1150–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314543196

- Akkerman, S. F., & Bakker, A. (2011). Learning at the boundary: An introduction. International Journal of Educational Research, 50(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.002

- Armstrong, L., Bailey, J., Julier, G., & Kimbell, L. (2014). Social design futures: HEI research and the AHRC. https://cris.brighton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/341933/Social-Design-Report.pdf

- Bochner, A., & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative autoethnography: Writing lives and telling stories. Routledge.

- Boydell, K. M., Volpe, T., Cox, S., Katz, A., Dow, R., Brunger, F., Parsons, J., Belliveau, G., Gladstone, B., Zlotnik-Shaul, R., Cook, S., Kamensek, O., Lafrenière, D., & Wong, L. (2011). Ethical challenges in arts-based health research. The International Journal of the Creative Arts in Interdisciplinary Practice, 11(1), 1–17. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/45773991/Ethical_Challenges_in_Arts-based_Health_20160519-11080-wapm0r-libre.pdf?1463664672=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DEthical_challenges_in_arts_based_health.pdf&Expires=1695909652&Signature=gp1ISpmXN~iqbEt~tVbNfmO1ByLiiEWKuGrraTWQxBUt8tL7~e9BLpn6cdbp5FmAXdflEZA~W3zDmF6CBsRRr5gms87zQ6PTOavF8bgRvmlBautwKMA6g78ONHa6ytAfWcMIo7UEFchOsW0V-7TXrIa-BPmBg96msILOJokQnefo2OuoBE2ZOP53Q9kr3Y25EAw1jdekYz-~52-ZCaTDtuQoB7QIMjEgzBquWV-XSZoRUcNnBlmI4bIM19dnvcV319Q1IcxLoyG5uD63Izh90C3ArNP59tsgVsWVoG4JteockooMlzTnjq8XEVNr8PhwK8IjATT5lzuWmo8v4EO8vA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA

- Bradfield, E. (2021). Creative ageing: Participation, connection & flourishing a mixed-methods research study exploring experiences of participatory arts engagement in later life through a systematic review of literature and focus groups with older people. University of Derby [ United Kingdom]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18233.39520

- Broome, E., Dening, T., & Schneider, J. (2019). Facilitating imagine arts in residential care homes: The artists’ perspectives. Arts & Health, 11(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2017.1413399

- Cook, T. (2009). The purpose of mess in action research: Building rigour through a messy turn. Educational Action Research, 17(2), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790902914241

- Curtis, A., Gibson, L., O’Brien, M., & Roe, B. (2018). Systematic review of the impact of arts for health activities on health, wellbeing and quality of life of older people living in care homes. Dementia (London, England), 17(6), 645–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217740960

- Cutler, D. (2019). Around the world in 80 creative ageing projects. Baring Foundation. https://baringfoundation.org.uk/resource/around-the-world-in-80-creative-ageing-projects/

- Daykin, N. (2019). Social movements and boundary work in arts, health and wellbeing: A research agenda. Nordic Journal of Arts, Culture and Health, 1(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-7913-2019-01-02

- Daykin, N. (2020). Arts, health and well-being: A critical perspective on research, policy and practice. Routledge.

- Duijn van, S. (2022). Tinkering with tensions: Boundary work and collaborative governance. [Vrije Universiteit]. https://research.vu.nl/en/publications/tinkering-with-tensions-boundary-work-and-collaborative-governanc

- Fafard, P. (2020). Can art influence global health policy? Imaginations: Journal of Cross-Cultural Image Studies/Revue D’études Interculturelle de l’image, 11(2), 193–216. https://doi.org/10.17742/IMAGE.IN.11.2.11

- Fancourt, D. (2017). Arts in health: Designing and researching interventions. Oxford University Press.

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). Health evidence network synthesis report 67. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/329834/9789289054553-eng.pdf

- Frambach, J. M., van der Vleuten, C. P., Durning, S. J., Carbonell, K. B., Beckers, J., Frambach, J. M., & de Bruin, A. B. H. (2013). AM last page: Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Academic Medicine, 88(10), 552. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828abf7f

- Fraser, A., Bungay, H., & Munn-Giddings, C. (2014). The value of the use of participatory arts activities in residential care settings to enhance the well-being and quality of life of older people: A rapid review of the literature. Arts & Health, 6(3), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2014.923008

- Fraser, K. D., O’Rourke, H. M., Wiens, H., Lai, J., Howell, C., & Brett MacLean, P. (2015). A scoping review of research on the arts, aging, and quality of life. The Gerontologist, 55(4), 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv027

- Groot, B., & Abma, T. (2021). Boundary objects: Engaging and bridging needs of people in participatory research by arts-based methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 7903. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157903

- Groot, B., de Kock, L., Liu, Y., Dedding, C., Schrijver, J., Teunissen, T., van Hartingsveldt, M., Menderink, J., Lengams, Y., Lindenberg, J., & Abma, T. (2021). The value of active arts engagement on health and well-being of older adults: A nation-wide participatory study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8222. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158222

- Haberl, E. (2021). Lower case truth: Bridging affect theory and arts-based education research to explore color as affect. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406921998917

- Hochschild, A. (2002). Emotional labour. In S. Jackson & S. Scott (Eds.), Gender: A sociological reader (pp. 192–196). Psychology Press.

- Hsiao, R. L., Tsai, D. H., & Lee, C. F. (2012). Collaborative knowing: The adaptive nature of cross-boundary spanning. Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), 463–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01024.x

- Huhtinen-Hildén, L. (2014). Perspectives on professional use of arts and arts-based methods in elderly care. Arts & Health, 6(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2014.880726

- Knowles, J. G., & Cole, A. (2008). Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues. Sage.

- Koivisto, T. A. (2022). The (Un) Settled Space of Healthcare Musicians: Hybrid Music Professionalism in the Finnish Healthcare System. [ Taideyliopiston Sibelius-Akatemia]. https://taju.uniarts.fi/handle/10024/7582

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2019). Analyzing qualitative data with MAXQDA. Springer International Publishing.

- Laukkanen, A., Jaakonaho, L., Fast, H., & Koivisto, T. A. (2022). Negotiating boundaries: Reflections on the ethics of arts-based and artistic research in care contexts. Arts & Health, 14(3), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2021.1999279

- Leavy, P. (2020). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. Guilford Publications.

- Liu, Y., Groot, B., de Kock, L., Abma, T., & Dedding, C. (2022). How participatory arts can contribute to Dutch older adult’s wellbeing – revisiting a taxonomy of arts interventions for people with demenia. Arts & Health, 15(2), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2022.2035417

- Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, `Translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

- Yoeli, H., Macnaughton, J., McLusky, S., & Robson, M. (2020). Arts as treatment? Innovation and resistance within an emerging movement. Nordic Journal of Arts, Culture and Health, 2(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-7913-2020-02-02

Appendix A

Project description of ENCOUNTER#9

The case study in this article follows the boundary work surrounding the project ENCOUNTER#9, led by social designer Joost van Wijmen, who has a background in costume design for theatre.

ENCOUNTER is a foundation set up by social designer Joost van Wijmen. Within this foundation, Joost uses design to explore the impact of the changing body on the identity and relationships between people. In ENCOUNTER#8, Joost organised encounters between students of social work and elderly residents of a care organisation. The research on boundary work described in this essay took place during the transition of moving from this small pilot project, ENCOUNTER#8, to scaling up the project in ENCOUNTER#9.

For ENCOUNTER#8 Joost designed encounters between people. A small group of five students and five independently living older people took part. They were paired up and met in the same couple every week for 14 weeks. Both students and older people volunteered to take part in the project. During every encounter, they received assignments designed by Joost. The assignments asked participants to carry out different tasks such as documenting and comparing the number of metres they covered in a day, photographing their different views for a week or wearing each other’s clothes in order to transform in each other. They also required participants to jointly reflect on these tasks and answer questions such as “What significant changes has your body gone through over the years, and how do you experience time?”

The participants were interviewed by researchers from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and were mostly positive about their experiences, they felt connected and like they had gotten to know the other person (Hoens, et al., 2020). As a designer, Joost was also pleased with the outcomes of the project; students and older people seemed to have engaged in reciprocal contact and discussed topics that went beyond daily chit-chat, but touched on a deeper, existential layer of being human, which was an important goal for him. Besides this, the outcomes of the meetings, such as the different photos and journal records the participants kept, were “interesting”, according to Joost’s aesthetic vision: He was able to produce a publication of the result which he regarded meaningful, which, as an artist, was important to him, so he stated in initial conversations with the research team.

The goal for ENCOUNTER#9 was to scale up the success of ENCOUNTER#8. This meant that the project would continue in the same location with more students and more older residents. At the same time, a new care location and two new partners were found who would take part in the project. This time, instead of students from a higher professional education institute (Avans Hogeschool), students of social work from a vocational training institute (mboRijnland), took part. In the new care organisation it was decided the project would take place in a day centre for older people with somatic as well as cognitive impairments. In short, the project was initially designed for a specific group of partnering organisations and participants, and those organisations and participants changed in ENCOUNTER#9. This meant the project required boundary work from all those involved in order to get the project up and running, let alone live up to all of their different goals and expectations.