ABSTRACT

Objective

To synthesise qualitative research exploring the care-giving experiences of parents of young people with profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD) and complex healthcare needs, in the transition to adulthood years.

Method

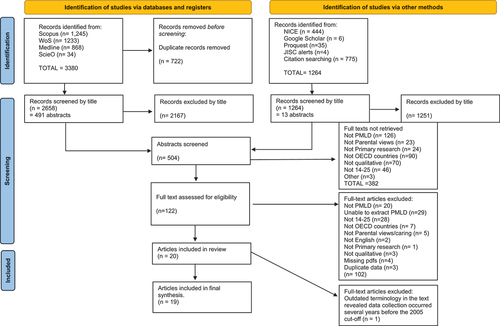

Four databases were systematically searched: Scopus, WoS Core Collection, Medline and SciELO. Included papers were assessed for quality and thematically synthesised. Findings are presented in the form of free-verse poems.

Results

Nineteen papers from eight countries were included. Analysis generated three themes: interdependency of parent and child, where parents retained responsibility for their child’s care; apprehension regarding sharing and shifting responsibility between parents and professionals; an uncertain future in terms of care provision.

Conclusions

Parents are concerned about the future care of their children. Training professionals in alternative and effective communication is fundamental to successful transition. Encouraging discussions about advanced care planning may also alleviate parental concerns and ensure good outcomes for young people with PMLD.

Introduction

Young people with profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD) have severe intellectual (and other) disabilities that significantly affect their ability to communicate and be independent (NHS, Citation2018). Many young people with PMLD are also present with complex medical needs, which, when unmet, can lead to poor health outcomes (Heslop et al., Citation2014). These young people may have epilepsy, and respiratory problems, sometimes caused by dysphasia, which may result in life-threatening chronic chest infections (Proesmans, Citation2016). They may also have profound neuromotor dysfunction, little understanding of verbal language, as well as sensory impairments (Nakken & Vlaskamp, Citation2007). As a group, young people with PMLD are largely dependent on others for everyday aspects of care.

Owing to improvements in health care and technology, life expectancy for young people with PMLD and complex healthcare needs has significantly improved, necessitating transition from paediatric to adult health and social care systems (Brown et al., Citation2019). Transition has been defined as the “purposeful, planned process that addresses the medical, psychosocial and educational/vocational needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions as they move from child-centred to adult-oriented health care systems” (Department of Health, Citation2006, p. 14). While mainstream transition models conceive the parental role as incrementally decreasing with adolescent development, young people with PMLD remain dependent on caregivers, meaning parents necessarily retain responsibility for ongoing care throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Jacobs et al., Citation2018). Healthcare transitions in general have been recognised as a time of great stress for parents (Heath et al., Citation2017). For those parenting a child with PMLD, stress is often heightened by worry about future provision (Willingham-Storr, Citation2014).

While the challenges faced by new parents when their child has a profound disability are well documented (Wong et al., Citation2017), less is known about the enduring elements of care required throughout transition to adulthood. A recent review of parents’ knowledge of their child with PMLD found that parents fulfil key roles of expert in their child’s communication, wellbeing and pain and advocate for their child’s needs (Kruithof et al., Citation2020). Despite this, previous reviews exploring adolescence and early adulthood of those with PMLD have focused on transitions from school to adult services (Jacobs et al., Citation2018) and the process of healthcare transitions, specifically implications for nursing (Brown et al., Citation2019).

In addition, there are few qualitative evidence syntheses in this area. A review of reviews exploring healthcare transitions, but not including young people with PMLD (Yassaee et al., Citation2019), found only four included solely qualitative reviews, focusing on experiences of young people with chronic somatic conditions (Fegran et al., Citation2014), adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder (DePape & Lindsay, Citation2015), parents of young people with chronic illness (Heath et al., Citation2017) and young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Price et al., Citation2018). No reviews have sought to understand the experiences of parents of young people with PMLD throughout transition to adulthood and adult services. Understanding parents’ experiences in this context is important for identifying their (as well as their child’s) support needs.

Aim

To synthesise primary qualitative research exploring the lived care-giving experiences of parents of young people (aged 14–25 years) with PMLD and complex healthcare needs.

Method

Pre-registration

A review protocol was pre-registered on the PROPSERO database (ID No: CRD42020187939) available via https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero.

Inclusion criteria

We included qualitative studies (stand alone or within mixed-designs where qualitative findings could be separated) if they reported care-giving experiences of parents of young people with PMLD and complex healthcare needs, within a transition window of 14–25 years (Care Act, Citation2014). To be comparable in terms of healthcare provision, studies had to be conducted within Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries, with a universal healthcare system (excluding USA and Mexico). Studies were included from 2005, when the influential “Improving the Life Chances of Disabled People” (UK Government, Citation2005) report was published, up to April 2023. Only studies reported in English were included.

We excluded paid carers, siblings and young carers, because they have different needs to those of parents. Also excluded were young people with intellectual disabilities without healthcare needs; young people with moderate learning disabilities and those with accidentally acquired disabilities. Studies examining diagnosis experiences and those examining parents’ experiences of the death of a child with PMLD were also excluded.

Information sources and searches

We searched Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, Medline, SciELO, NICE Evidence database and Google Scholar from January 2005 to April 2023, setting up alerts for Jisc Zetoc and Web of Science. References and citations of included papers were checked to identify further papers. We developed a search strategy using the Context, How, Issues, Population (CHIP) tool (Shaw, Citation2011) adapted for each database. Boolean operators were used to combine synonyms (OR) and key concepts (AND) including terms for the Context: transitional care for young people with PMLD and complex healthcare needs; How: qualitative methods; Issues: caregiving experiences; Population: parents of children with PLMD (supplementary file 1).

Study selection and data extraction

After removing duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts, including papers for full-text screening in cases of uncertainty. We then screened full-text articles against the inclusion criteria, paying attention to level of disability, age, and whether parent-carer roles could be separated if presented as part of a mixed sample (e.g. other family members, paid carers). We extracted data using a pre-designed form (e.g. year, country, study design, recruitment, participant demographics). Original author themes were extracted, and data split into first-order (participants’ quotations) and second-order data (author’s interpretations).

Quality appraisal

Two authors (KS, GH) assessed the quality of included studies using an adapted CASP (Citation2018) checklist. As suggested by Long et al. (Citation2020), a “maybe” category was added to allow for more nuanced answers. Value of the research was scored on a scale of 1–5 (not valuable to very valuable). Discrepancies were discussed with a third member of the team (RS). Synthesis findings were appraised using Confidence in Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) guidelines (Lewin et al., Citation2018).

Patient and public involvement

To support the review, we established a stakeholder advisory group including parents of young people with PMLD and people who had worked in education, health and social care. The Transition Research Advisory Group (TRAG) was consulted at three points: (1) early stages of preparation, guiding review parameters, (2) point of study collation, providing feedback on a selection of identified papers, (3) during data synthesis, reviewing thematic and poetic findings.

Data synthesis

We synthesised extracted data using an inductive thematic approach. KS then constructed poems from extracts of the first-order data to highlight key findings.

Thematic analysis

Included articles were allocated to three groups: parental experiences, healthcare studies and transition-specific studies. Working with these sets, we synthesised data following Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) guidelines. We coded data descriptively before combining codes to generate tentative themes. We then examined themes across the three groups, looking for similarities and differences. Themes were refined and agreed by all authors and our TRAG. As data were so diverse, we adopted a line of argument approach (Noblit & Hare, Citation1988) in the final write-up.

Poetic synthesis

Writing original poetry is well established within healthcare science as an aid to patient care (Barak & Leichtentritt, Citation2017). Furman and Dill (Citation2015) argue that the research poem “is a valuable means of condensing research data into its most elemental form” (p.44) while emphasising “understanding of living and what it is like ‘to be there’ [by bringing] the richness of experience into language” (Galvin & Todres, Citation2009, p. 309). Ward (Citation2011) argues that poetry brings participants’ experiences to the reader, inviting them “into the research space” (p.356).

To generate our poetic synthesis, we adopted a method similar to Prendergast’s Surrender and Catch process. Prendergast’s method (rooted in phenomenology) suggests suspending preconceptions – the surrender – and allowing “what happens [to] happen” – the catch (Faulkner, Citation2020, p. 162). After reviewing first-order data to identify quotations that illustrated themes, KS used original imagery and language to generate “found” poems which resonated with her own experiences and her emotional responses to participants’ words. KS then used a “free-verse” approach to maintain participants’ narratives, enhancing their voice within the analysis. Finally, poems were given titles, adding a further interpretative dimension. Fidelity to original quotations was maintained, except for standardising genders of children to add cohesion to the poems, when blending the experiences of more than one parent ().

Table 1. Stages of poetic synthesis.

Results

Searches

Following removal of duplicates, searches yielded 3922 articles. Nineteen papers were included, referenced by number (; supplementary files 2 & 3). Included studies were published between 2008 and 2021 and spanned eight countries (UK, Australia, Canada, Eire, Netherlands, Poland, South Korea and Sweden). In most cases, parents of children with PMLD and complex healthcare needs could be identified (2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 16, 18, 19). In others, data were extracted specifically relating to parents of young people with PMLD, within the appropriate age group (1, 4, 7, 12 13, 14, 15, 17). Authors were contacted for clarification where required (3, 4, 8).

Participants

Data relating to 409 parents were reported across included studies; 278 parents participated in interviews and focus groups, and 131 participated in qualitative surveys. From this pool, data from 261 participants were extracted on age of child and disabilities (supplementary file 4). The reported overall ratio was 4:1 female to male, although gender was not reported in all studies. Young person gender was not available in eight studies, making it unreliable to report. Age range of offspring was 3–44 years, but only data from parents of young people aged 14–25 years were included.

Quality

Overall, quality of included papers was high, with 11 papers assessed as very valuable for answering the research question, five as valuable and three as quite valuable (supplementary file 3). No papers were excluded based on quality.

Thematic and poetic findings

Analysis generated three key themes: Interdependency; Sharing and shifting responsibility; An uncertain future (; supplementary file 5). Findings are presented in the form of free-verse poems which formed part of the thematic synthesis.

Interdependency

Retaining parental responsibility

Included accounts revealed parents and their offspring as wholly interdependent. Parents had a dedicated commitment to, and expert knowledge of their child, and so assumed “undelimited responsibility” (14). “Undelimited” may be defined as dedicated and without boundaries, having the essence of something above and beyond that which would be considered “normal”. The driving force behind this exceptional care was a need to protect the vulnerable young adult, often perceived by others as broken. Love was therefore coupled with the need to protect.

Parents had to face their own beliefs, as well as discrimination from others, even moving to another country for greater acceptance (15). The mother in poem one, for example, described how she “used to think” of disability as something “dirty or horrible”, possibly referring to a religious context, but also rooted in her child’s double incontinence. She felt she was to blame. However, a shift in her understanding of the disability, “his brain is not functioning properly”, reflected acceptance and adjustment to living with disability. Care given to the child demonstrated the mother’s unconditional love (4), which was, at times overwhelming (17). One mother said:

As parents you come to terms with your child’s disability and accept it because if you don’t, other people around them will not accept that disability as well.

This normalisation of disability made it hard to define how much labour was involved in looking after these young people, because parents often took it for granted, and assumed undelimited parental responsibility for their child’s care:

When you’ve got a child that’s as disabled as [daughter] is, your automatic reaction is to just take over. (13)

Communication

A key factor in parents’ assumptions of responsibility was a belief that their child was unable to communicate effectively with others (17), or that others did not try to understand their child (11). It was an emotional challenge for parents “The fact that he can’t express what he’s feeling …, well, as a parent, I’m extremely sensitive about it.” (12). Parents learned how to interpret their child’s communication (16). This was often through limited language (17), the child’s behaviours (9) or through facial expressions (16).

In poem 2, the parent becomes an investigator and interpreter. They “experienced” their child’s pain, and thus became an extension of the child. Such deep understanding and interpretation are not inherent but learned from the child over time (16). Gradually, they acquired an expert understanding of their child’s needs and condition, so by the time their child reached adolescence, parents maintained a continuing role as primary advocate and decision-maker (2, 8, 10, 11, 12, 16), often acting as translator. Difficulties that professionals had in communicating with young people with disabilities highlighted parents’ skill, and their vital role, as their child’s mouthpiece. Communication was therefore, seen as key to the transition process. Some parents discussed when to include or exclude their child in decision-making, as they considered the young person lacked capacity to understand the complexities of life-choices (13).

Sharing and shifting responsibility

Sharing responsibility did not come easily. When parents recognised their child as having extraordinary needs, they were often hesitant about accepting support from others (4, 14). Some mothers were ambivalent towards paid care, feeling guilty asking for help (4) or expecting highly qualified staff (4, 17). A lack of trust often arose from previous errors (4, 8,14,17). At the same time, however, families relied on healthcare professionals because of the young person’s complex healthcare needs.

Negotiated care

Sometimes parents felt healthcare staff were unhelpful:

A volunteer doctor was there, he was somewhat disrespectful, played fast and loose, I didn’t want to go there again (12)

Parents also worried that their adult child’s difficulty in expressing themselves would make them vulnerable if left unattended in hospital (3, 10). They were afraid to leave their child’s bedside, particularly when admitted to unfamiliar adult wards.

Parents reported that they were often expected to stay by their offspring 24 hours a day in hospital, to administer feeds and personal care, although such care was not expected of paid support workers (10). This parent–child interdependence then led to a failure on behalf of healthcare staff to view young people and their parents as separate, and the child lost their identity as a person in their own right.

Poem 3 highlights continued parental responsibility in an environment where they might be expected to share care. The problem thus became compounded, with parents feeling they could not leave their offspring unattended, and staff assuming parents would undertake caring roles.

When moving from children’s services to adult health care, parents used metaphors of battles and combats, having to “fight” (3, 10, 11, 18) for their child. Sometimes they had to beg for their child to be taken into hospital (3,9,18), or were excluded from services owing to the severity of their child’s disability (10, 14, 18). When healthcare professionals failed to take responsibility, the lack of support sometimes led parents to take risks:

…the biggest horror in my life is that my daughter may go into hospital … I have to admit I sometimes don’t inform the GP because I know she might get taken away (10)

In this case, and others, there were overtones of negligence (parents not asking for help; potential negligence in hospital) and fear for what might happen in the short and long term. Similarly with dental care, parents made decisions to avoid treatment, owing to dentists not understanding their child (12).

Sharing expertise

Parents frequently assumed a role that was above and beyond “normal”, such as administering medicines (14) and maintaining vigilance in situations when others might be in charge, such as writing out prescriptions (8) or explaining how feed systems worked (3). So, although parents were seen as integral to their child’s care, they were also perceived as experts by experience:

Parental expertise developed through caring for their child and working with paediatric healthcare professionals (2, 3). At transition to adult services, parents often felt they had more knowledge than the medical staff they encountered, who had sometimes never encountered the child’s health technologies before (14). Parents often advised on things like medication, which often did not conform to standard doses (8).

In cases where parents had good relationships with healthcare professionals, they experienced a sense of shared responsibility and partnership (8), but when things did go wrong, parents felt they still carried responsibility: “it was partly our fault/we could have helped” (3). Parents were experts and were acknowledged as experts in their child’s care by paediatric staff (2, 16), but in adult services, parents found themselves excluded from decision-making which was experienced as enormously frustrating. Ultimately, parents wanted partnership with professionals as their children entered adult services:

We need guidance and advice in difficult decisions but make them ourselves (2)

An uncertain future

Future timescales for people with PMLD remain uncertain throughout their lives. The unknown element of the child’s lifespan was expressed by parents whose children had rare syndromes:

If you knew their lifespan you would know what to expect and which road you’re going to go down. It’s not fun living in the dark and that’s what I’ve lived in for 30 years, not knowing what is the next stage (11)

Parents lived with fear and knowledge that owing to their child’s physical vulnerability, they could lose them at any time (14). It affected their own hopes and aspirations (5). Planning for the future was difficult and made harder by services being uncoordinated or unsupportive during the transition years.

(In)dependence

Parents assumed an all-enveloping responsibility for their children up until the point of adulthood, the child’s 18th birthday. Often, they believed this responsibility would not alter, owing to the young person’s physical and intellectual limitations. However, parents were faced with cessation of the familiar, supportive paediatric services and a transfer to adult services, in which their own role fundamentally changed. Parents had to adjust to new ways of working (3,9,19).

Some parents wanted paediatric care, where they felt “real affection and mutual respect”, to continue (1), whereas others recognised that their child was growing up and deserved a level of independence (19). There was also tension between the young person’s right to independence, and an independence that was forced upon them because of their parents’ ageing (1). Many parents felt they would be carers for the rest of their lives (9, 19), expressing reticence to let their child go into full-time care:

I mean we even spoke about if he gets really bad, we’re going to give him up to the ‘State’…God, it’s horrible (1)

The parent’s vision of abandoning their child to institutional care was far removed from models of independent living. However, their choices were also influenced by practicalities of life, including the parent’s need to work:

I don’t want to place my daughter full-time or stop working yet (9)

Parents also wanted to be involved in meaningful activities for themselves:

It’s one’s self worth and what you want out of life … I want to be able to do something…something worthwhile” (15)

Another mother looked to regain her own future, saying “I want my life back” (11).

Fear of death

Parents knew that their child was physically vulnerable, and each hospital admission carried the overshadowing possibility of death, with terms such as “life expectancy” (2) used. Parents faced a complex reality that either their child would pre-decease them, or that they would die first, thus abandoning their responsibilities, and leaving a vulnerable adult to be looked after by someone else.

In poem 6, the mother’s wish that her daughter die before her seems shocking, not least because these parents have already gone beyond “normal” parenting to care for their children. Yet, uncertainty brings anxiety as she asks, “what will happen if the parents are not around anymore – we wish we could stop worrying about it?” (18). Tension thus existed between a mother confronting her own mortality and making plans for her child, when there was “deep-seated mistrust” in service providers (17).

This fear for the future was compounded by negative emotions associated with caring through the transition years, including bleakness (3, 10, 11); frustration (10); anxiety (3, 9, 10, 13, 14); uncertainty (6, 11); fear (3, 9, 14, 17) and feelings of abandonment (3, 6, 9, 10). For many, it was not only children who are vulnerable but also parents: “when the child suffered, so did the parent” (16). But for some, there was just resignation:

She’s going to come to a point where we’re not going to be around. She can’t rely on us to do everything all the time. (14)

Discussion

This review explored the lived care-giving experiences of parents of young people with PMLD and complex healthcare needs, during their transition to adult health and social care services. Findings suggest that the experiences of this group are present in the literature but rarely treated separately. This highlights them as a hidden group, both in research and society, meaning they may be poorly understood even by professionals. Our poetic synthesis emphasised emotional aspects of these experiences, which span healthcare settings and countries.

Parents were shown to perform an “intense parenting” role (Woodgate et al., Citation2015), often acting as the child’s voice. Poems highlighted the parental caring role as labour intensive and physically exhausting, eliciting a range of emotions, including frustration, fear and love. Nevertheless, parents continued to retain responsibility for their child throughout young adulthood. In the transition to adult services, parents faced uncertainty and apprehension about service transfer, as well as fear for the future of their child’s care. While poems highlighted several adverse aspects of caring, parents also expressed love for their child and some positive aspects to quality of life. Thus, as Green (Citation2007) suggests, caring for a severely disabled child is more nuanced than just burdensome. While parents may be tired and suffer financial constraints, the emotional impact can also be positive.

Poems emphasised parents’ experiences of their exchanges with healthcare professionals as “highly emotionally charged” (Griffith & Hastings, Citation2014, p. 416). Parental reluctance to share responsibility for their child’s care partly developed from professional limitations in effective communication with young people with PMLD. Communication with, and for, their child was thus shown by parents to be central to their role as expert and advocate, having developed alternative communication strategies with their child based on “tacit knowledge” (Kruithof et al., Citation2020, p. 1145). Understanding how such knowledge can be shared is important, as these skills may be transferrable. Parents felt reassured when professionals took time to understand their child’s method of communication. However, within hospital settings, time was not always available for such learning.

Furthermore, the role of advocate has been recognised as central to parents’ identity (Ryan & Runswick Cole, Citation2009). Yet, this review suggests parents’ identity is challenged during transition when they are excluded from decision-making. Preparing for adulthood was therefore shown to elicit anxiety both in terms of planning for the child and in understanding the parents’ own role. In our synthesis, some parents embraced the idea of their child’s independence, where others felt they would remain carers forever. Jacobs et al. (Citation2018) found the needs of parents and young people were highly interdependent, but it seems that by accepting this interdependence as the status quo, future outcomes for the child dictate the parents’ role and identity.

Parental anxiety, which was felt during service transfer, was also an anxiety which looked to the future. While parents had lived with the constant threat of their child’s sudden death, the final poem highlighted fear for a future where the child outlived their parent. Kruithof et al. (Citation2021) found parental concerns about not being there were not just related to caring and advocacy roles, but also to who would provide their child with love, enabling them to thrive. Such concerns meant parents of young people with PMLD were afraid of dying before their child, sometimes expressing a wish that their child might die before them (Kruithof et al., Citation2021). Older parents of children with disabilities stated that they could not see any future for themselves and had given up on planning for their future because of caring demands (Cairns et al., Citation2013).

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review of parents’ care-giving experiences of parenting a child with PMLD with complex healthcare needs during the transition to adulthood. Included studies were drawn from a range of countries, with data found to be predominantly “very valuable” using the CASP criteria. Themes were assessed against GRADE-CERQual guidelines (Lewin et al., Citation2018) with high confidence established (supplementary file 6). Reflexively layering participants’ voices to create poetry developed a line of argument which distils the essence of caring in a more powerful and emotive way than traditional quote-based interview reporting. Poetry’s ability to reach atypical audiences is also an important contribution (e.g. as a tool for communicating experiences to those outside of the research community).

While searches identified a range of studies, qualitative research specifically exploring young people with PMLD and complex healthcare needs remains limited, with Australia and the Netherlands leading the field. Exclusion of US research (on grounds of healthcare systems) may have eliminated insightful experiences. A difficulty arose in trying to identify the level of disability of the young people within the studies, suggesting terminology would benefit from standardisation. Given the limited research, it was difficult to highlight specific problems such as continence, as these issues are normalised by parents, and taboo in society.

Implications for practice

Implications for practice were drawn from findings and discussed with members of the TRAG (supplementary file 7). Recommendations were suggested for improved support via carers’ assessments, improved training for professionals in communication with young people with PMLD and recognition of parental expertise. Advanced care planning for young people and parents was also considered to help alleviate fear for the future.

Further research

Little is known about the life of people with PMLD as they grow into their thirties and beyond. Further research focussing on young people with PMLD, and complex healthcare needs is required. There is also a need for research into how health and social care professionals communicate with young people with PMLD and their families. There is a need to consider parental advocacy and decision-making later in life, in preparation for their own death. Additionally, how people with PMLD cope with the loss of a parent (who historically has outlived their children) is an area for exploration.

Reflexivity

KS is the mother of a young person who has autism and severe learning disabilities. As part of a reflexive approach, KS undertook a series of bracketing interviews to discuss her own experiences and examine preconceptions relating to transition and parenting a child with PMLD. This process allowed KS to reflect on her position both as researcher and parent. Throughout data analysis, it became clear that participants’ voices resonated with KS, and poems were subsequently “found” within her emotional response to their words. However, some TRAG members commented that poems did not reflect “the joy” of parenting a child with disabilities. In response, the authors returned to the first-order data and re-examined their analyses. This process confirmed emphasis on problems encountered by parents in the first-order data, perhaps reflecting the research questions, which set out to identify issues. Alternatively, first-order data may have been influenced by the parents who took part in those studies, wishing to express their concerns.

Conclusions

This synthesis collates parents’ experiences of caring, communication and future planning for their children with PMLD in the transition to adulthood years. Parents were reluctant to relinquish responsibility to professionals who may not be able to communicate effectively with their child. Parents’ own sense of identity was also affected by marginalisation at the transfer to adult services. A key source of anxiety for parents was uncertainty regarding the future. Open conversations between parents and professionals about sharing responsibilities and decision-making, uncertainties and risks would reduce parental anxiety relating to lost knowledge when the young person leaves home, or the parent dies.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (93.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Transition Research Advisory Group (TRAG) for their unique and incisive contributions to this meta synthesis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2023.2288058

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barak, A., & Leichtentritt, R. D. (2017). Creative writing after traumatic loss: Towards a generative writing approach. British Journal of Social Work, 47(3), 936–954. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw030

- Brown, M., MacArthur, J., Higgins, A., & Chouliara, Z. (2019). Transitions from child to adult health care for young people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(11), 2418–2434. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13985

- Cairns, D., Tolson, D., Darbyshire, C., & Brown, J. (2013). The need for future alternatives: An investigation of the experiences and future of older parents caring for offspring with learning disabilities over a prolonged period of time. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2012.00729.x

- Care Act. (2014) Retrieved from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted

- CASP. (2018) Critical Skills Appraisal Programme Checklists Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- DePape, A.-M., & Lindsay, S. (2015). Parents’ experiences of caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314552455

- Department of Health. (2006) Transition: Getting it right for young people. Retrieved from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130123205838/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4132145

- Faulkner, S. (2020). Poetic inquiry. Craft, method and practice (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Fegran, L., Hall, E., Uhrenreldt, L., Aagaard, H., & Ludvigsen, M. (2014). Adolescents and young adults transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: A qualitative metasynthesis. Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.001

- Furman, R., & Dill, L. (2015). Extreme data reduction: The case for the research tanka. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 28(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/08893675.2015.990755

- Galvin, K., & Todres, L. (2009). Poetic inquiry & phenomenological research: The practice of embodied interpretation. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry (pp. 307–316). Sense.

- Green, S. (2007). “We’re tired, not sad: Benefits and burdens of mothering a child with a disability. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.025

- Griffith, G., & Hastings, R. (2014). He’s hard work, but he’s worth it. The experience of caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(5), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12073

- Heath, G., Farre, A., & Shaw, K. (2017). Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.011

- Heslop, P., Blair, P. S., Fleming, P., Hoghton, M., Marriott, A., & Russ, L. (2014). The confidential inquiry into premature deaths of people with intellectual disabilities in the UK: A population -based study. Lancet, 383(9920), 889–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62026-7

- Jacobs, P. M., K, Q. E., & Quayle, E. (2018). Transition from school to adult services for young people with severe or profound intellectual disability: A systematic review utilizing framework synthesis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(6), 962–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12466

- Kruithof, K., Olsman, E., Nieuwenhuijse, A., & Willems, D. (2021). I hope I’ll outlive him: A qualitative study of parents’ concerns about being outlived by their child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2021.1920377

- Kruithof, K., Willems, D., van Etten-Jamaludin, F., & Olsman, E. (2020). Parents knowledge of their child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: An interpretative synthesis. Journal of Applied Research Intellectual Disabilities, 33, 1141–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12740

- Lewin, S., Booth, A., Glenton, C., Munthe-Kaas, H., Rashidian, A., Wainwright, M., Noyes, J., Tunçalp, Ö., Colvin, C. J., Garside, R., Carlsen, B., Langlois, E. V., & Noyes, J. (2018). Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implementation Science, 13(Suppl 1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0688-3

- Long, H. A., French, P. A., & Brooks, J. (2020). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine and Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559

- Nakken, H., & Vlaskamp, C. (2007). A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal for Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4(2), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2007.00104.x

- NHS. (2018) Learning Disabilities Retrieved from https://www.nhs. uk/conditions/learning-disabilities/

- Noblit, G., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. SAGE.

- Price, A., Janssens, A., Woodley, A., Allwood, M., & Ford, T. (2018). Review: Experiences of healthcare transitions for young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review of qualitative research. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12297

- Proesmans, M. (2016). Respiratory illness in children with disability: A serious problem? Breathe, 12(4), e97–e103. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.017416

- Ryan, S., & Runswick Cole, K. (2009). From advocate to activist? Mapping the experiences of mothers of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00438.x

- Shaw, R. L. (2011). Identifying and synthesising qualitative literature. In D. Harper & A. Thompson (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: An introduction for students and practitioners (pp. 09–22). Wiley Blackwell.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews BMC. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- UK Government. (2005) Improving the life chances of disabled people. Retrieved from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/+/http:/www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/media/cabinetoffice/strategy/assets/disability.pdf

- Ward, A. (2011). “Bringing the message forward”: Using poetic re-presentation to solve research dilemmas. Qualitative Inquiry, 17(4), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411401198

- Willingham-Storr, G. L. (2014). Parental experiences of caring for a child with intellectual disabilities: A UK perspective. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 18(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629514525132

- Wong, V., Yu, Y., Keyes, M. L., & McGrew, J. H. (2017). Pre-diagnostic and diagnostic stages of autism spectrum disorder: A parent perspective. Child Care in Practice, 23(2), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2016.1199537

- Woodgate, R., Edwards, M., Ripat, J., Borton, B., & Rempel, G. (2015). Intense parenting: A qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC Pediatrics, 15, 197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-015-0514-5

- Yassaee, A., Hale, D., Armitage, A., & Viner, R. (2019). The impact of age of transfer on outcomes in the transition from pediatric to adult health systems: A systematic review of reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(6), 709–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.023