Abstract

The passage of the 1986 Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act over the veto of President Ronald Reagan was a stunning victory for US campaigners opposed to apartheid in South Africa. Sanctions against the apartheid regime were first proposed in Congress in 1972 but struggled to build sufficient support beyond veterans of the US civil rights movement. This article argues that the discursive framing around the sanctions issue was important to its construction of a wider coalition of supporters in Congress. Both grassroots organizations and supporters in Congress moved away from a civil rights framing to an anti-communist framing, having briefly experimented with a human rights discourse championed by Jimmy Carter. This article is the first to use a word-scoring method to trace discourse systematically during the fourteen-year period when Congress debated the sanctions issue.

1. Introduction

So the first reason why I offer these powerful sanctions against South Africa [is]… we must assert our role in the international community as a nation committed to the dignity of people, to freedom of human beings, to the concept of human rights; not as an abstract idea but as a reality.Footnote1

These words, spoken by Congressman Ron Dellums of California in the House of Representatives on 18 June 1986, constitute the most familiar framing of debate over the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act (CAAA). Dellums had introduced the first sanctions bill against South Africa in 1972, and was a key voice on this issue, as well as a leading figure within the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) throughout his career. Figures like Dellums wanted to sanction South Africa over its regime of “apartheid,” a system which guaranteed white minority political rule, in turn subjugating its black majority. Those opposed to apartheid acted on calls by organizations rooted in South Africa, prominently the African National Congress (ANC), to pressure the government into systemic change through global economic isolation, via sanctions.Footnote2 Dellums was by no means the first prominent African-American figure to call for sanctions. In 1962 Martin Luther King issued a joint statement with then-ANC President Albert Luthuli, calling for international sanctions against South Africa. Additionally, Congressman Charles Diggs had a keen interest in southern African affairs following the decolonization of the African continent, which carried over when he was selected to chair the House Subcommittee on Africa, in 1969.Footnote3 What made the CAAA different to these efforts, however, is that Dellums garnered bipartisan support for the bill despite being a self-proclaimed socialist, at a time when such a label was particularly taboo given the on going Cold War. The CAAA even had enough support to override a veto by President Ronald Reagan, who feared instability in South Africa following sanctions. Reagan preferred a policy of “constructive engagement,” involving creating strong socio-economic ties between South Africa and the United States to slowly liberalize the country and end apartheid. Constructive engagement allowed the Reagan administration to appear to be opposed to apartheid, but without upsetting its relationship with South Africa’s white leadership, whom the United States depended on to provide access to the country’s vast mineral deposits.Footnote4 So what brought about these levels of support despite Reagan’s opposition? The most popular answer comes from scholars such as Francis Nesbitt and Robert Massie, who point to the legacy of the American civil rights movement. Many of its activists felt a moral connection between the fight for racial justice at home and similar struggles in Africa.Footnote5

This argument has merit but is incomplete. A body of scholarly literature has formed which emphasizes “human rights” discourse as a motivator for such acts of moral interventionism since the 1970s. This literature stipulates that human rights “emerged” as a notable concept with the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) after the Second World War. Perceptions that the Soviet Union had captured the concept of “human rights” for propagandistic purposes meant that the language of human rights soon faded from mainstream US political discourse. Human rights discourse seemingly “reemerged” in the 1970s, having been revived by leading political figures such as President Jimmy Carter. The most notable proponent of this argument is historian Samuel Moyn, who points to the sudden take-off of human rights groups such as Amnesty International in the 1970s. Carter placed human rights as the cornerstone of his foreign policy, owing to its “utopian” characteristics which brought the country much needed self-esteem following its failings in Vietnam.Footnote6 Therefore, it is possible that this uptake in interest in human rights continued into the 1980s, and in turn contributed to convincing Americans inside and outside of Congress to endorse sanctions against South Africa, given that its apartheid system was responsible for numerous human rights violations. White-ruled South Africa had a long history of perpetrating human rights abuses to maintain the apartheid system, most notably the Sharpeville massacre in March 1960 that killed in excess of 69 people, including 10 children.Footnote7 These abuses continued into the 1970s, with Amnesty International reporting in 1976 that South Africa suppressed protests against its occupation of Mozambique, raided anti-apartheid activists, arrested members of the ANC under the guise of “suppressing communism,” and tortured individuals in police custody, killing many in the process including black consciousness activist Joseph Mdluli.Footnote8

In the backdrop to Carter’s shift to human rights was the ongoing Cold War struggle between American capitalism and Soviet communism. Scholars in other contexts have shown convincingly that perceptions of the US supporting (or, at least, tolerating) racism at home or abroad hampered the country’s reputation, especially in post-colonial states. Policymakers were worried that the Soviet Union used claims about American racism for propaganda purposes. It is, therefore, equally important to explore the extent to which anti-communist considerations might have factored into congress members’ calculus when voting for the CAAA. This way of framing the arguments in favor of sanctions is important to consider, as it was utilized by figures close to President Reagan who later rescinded their support for constructive engagement, including Republican Senator Richard Lugar.Footnote9

This article sets out to answer the principal question, why did Congress finally pass sanctions against South Africa in 1986, after fourteen years of failing to do so? Can passage be explained by a shift in movement discourse from “civil rights” to “human rights?” To what extent did anti-communist sentiments feature in advocates’ rhetoric? While we acknowledge that there were other discourses surrounding the sanctions campaign, such as Christian or other religious and ethical arguments, the three discourses we have identified here are widely viewed as the most dominant among pro-sanctions advocates in both Congress and the grassroots movement in the 1970s and 1980s.

To answer these questions, this article analyses the language used by the sanctions movement (defined as supporters of sanctions at both elite and grassroots levels) between 1972 and 1986, to see the type of discourse being used to frame arguments for sanctions. This time period has been selected to reflect the full lifespan of sanctions bills in Congress, from the first South Africa sanctions bill being submitted in 1972, to the eventual passage of the CAAA in 1986. It uses content analysis and word scoring methods to identify the frequencies of key words and phrases associated with different discourses, among statements given in Congress by pro-sanctions congressmen and senators, materials published by grassroots advocacy groups, and articles written by favorable national newspapers. We assess the frequencies of human rights, civil rights, and anti-communist discourses.

The results of the analysis show that civil rights language was the most prevalent type of discourse among grassroots and media sources between 1972 and 1986. The story is different in Congress. From 1972 to 1984, pro-sanctions congresspeople framed the issue largely using civil rights framing, but after 1984 anti-communist framings prevailed. Although never dominant, a distinctive human rights language peaked after the election of Carter. It was most salient among members of Congress, and was eventually overtaken by anti-communism. Our data indicate that the motivations of the sanctions movement were more complex than is often suggested. Civil rights discourse was central to the grassroots-led early sanction movement, but a need for greater Republican support led the movement to frame its arguments more using anti-communism. Additionally, human rights could not contend with the bipartisan appeal of anti-communism or the grassroots salience of civil rights, largely due to Carter’s inability to promote the concept successfully beyond Washington. Despite these limitations, human rights discourse did help to build the coalition in Congress needed to pass the CAAA.

2. The anti-apartheid sanctions movement in the United States

According to Robert Fatton, President Ronald Reagan used fear of regime change in South Africa leading to a communist takeover to gather support for his policy of constructive engagement from both conservatives and moderates in Congress.Footnote10 Their transition from supporting constructive engagement to rejecting it outright is not yet fully understood. The role of grassroots organizations may contribute to this understanding, particularly through the work of scholars such as Meg Vorhees, who documents campaigns to force businesses and universities to divest their assets in South Africa as early as 1965, but which reached significant heights through state-level divestment policies being passed in the late 1970s.Footnote11 Additionally, sources detailing the role that sanctions have played in US foreign policy are worth considering, including the work of Hufbauer and Schott who characterize the sanctions against South Africa as part of a trend in American politics of using sanctions to destabilize oppressive regimes during the 1980s.Footnote12

Itibari Zulu has identified human rights elements within the work of TransAfrica, an NGO formed during the sanctions campaign to promote African issues in US foreign policy. Zulu highlights the ideological and denominational diversity of its participants, echoing literature emphasizing the bipartisan nature of “human rights” campaigns at this time.Footnote13 Historic parallels between the United States and South Africa have been well-documented by scholars such as Minter and Hill, who identify solidarity between both black populations in each country with their histories of struggle for racial equality.Footnote14 Francis Nesbitt notes that the CBC proposed legislation to prevent the United States supporting IMF loans to countries which violated human rights, specifically to block a proposed loan to South Africa.Footnote15

Another major argument is that the sanctions movement acted as a continuation of the American civil rights movement and its active role in crafting foreign policy. This argument is furthered by scholars such as Frank and Muriithi who identify commonalities between the protest methods used during both the civil rights and sanctions movements, particularly their uses of nonviolent mass non-cooperation.Footnote16 Alternatively, scholars such as Thomas Borstelmann posit that concerns over the United States’ global image within the wider Cold War context explains the growth of anti-apartheid sentiments. As early as the Truman administration, it was feared that the United States’ poor record on racial equality would be used by the Soviet Union to gain allies among developing countries.Footnote17 Therefore, the idea that civil rights and anti-communism were also relevant factors in this discussion has been considered before but has never been fully explored.

3. Rights discourse in the Cold War United States

Were these alternative influences on the sanctions movement shown to be more important than the role of human rights discourse, it would cast doubts on wider arguments about the salience of human rights in this period. One such argument, proposed by Stefan-Ludwig Hoffmann, rejects the scholarly consensus of the human rights breakthrough in the 1970s precisely because the ideological field was so crowded during the Cold War. Hoffman argues that “human rights” discourse in mainstream US politics did not truly emerge until after the Soviet Union’s collapse.Footnote18 While these alternative sources are important to consider, they fail to appreciate how human rights can have more subtle, discreet influences on politics detectable through language.

Many scholars situate the beginnings of American human rights discourse with the administration of Franklin Roosevelt. Lawrence Haas argues that following the Allied victory in the Second World War, American policymakers believed that the United States could act as an international guarantor of Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” (speech, worship, want and fear), albeit in a modest form which could be easily molded to fit its foreign policy priorities.Footnote19 Indeed, this argument is elaborated by Donnelly and Whelan, who identify the United States’ optimism in the role human rights would play after the Second World War, highlighting the active participation of the United States in drafting the UDHR. In this document, US officials advocated for civil and political rights such as freedom of speech, as well as economic and social rights such as access to welfare, in line with the “four freedoms.”Footnote20

However, US policymakers soon lost their enthusiasm for “human rights,” as the Soviet Union increasingly laid claim to the concept, emphasizing economic and social rights to a far greater extent than US policymakers felt comfortable. Helle Porsdam points to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which was created after the UDHR, as emblematic of this shift. The covenant was heavily influenced by the Soviet bloc and was seen by American politicians as a first step toward communism were it to be adopted. The United States refused to adopt the covenant, despite ratifying its sister Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.Footnote21

In the 1970s, the discourse of human rights experienced a “second wind” in US politics. Scholars such as Barbara Keys are important to contextualizing this shift. She explains that Carter’s election in 1976 represented a rejection of the politics responsible for the Vietnam War.Footnote22 Carter offered frequent acclaim for a human rights-oriented foreign policy strategy. Kenneth Cmiel adds that the concept gained bipartisan traction around this time, with both key House liberals such as Don Fraser and deeply conservative members such as John Ashbrook endorsing bills tying foreign assistance to human rights records, demonstrating its bipartisan salience.Footnote23 Additionally, human rights groups who had previously worked in obscurity began to take advantage of these new opportunities. Keys again details how Carter’s elevation of human rights structures gave new-found power to groups such as Amnesty International USA, allowing it to grow from its tiny offices in 1970 to becoming one of the most well-known NGOs in the United States by the decade’s end.Footnote24 The growth in the use of human rights discourse after Carter’s election has generated scholarly interest. Some have argued that they had a lasting legacy beyond Carter’s one-term presidency. Tamar Jacoby argues that President Reagan could not ignore this human rights shift. He, instead, re-purposed human rights to promote democracy in totalitarian regimes, which came to define much of his foreign policy, particularly through the creation of state-sponsored NGOs such as the National Endowment for Democracy.Footnote25

4. Research design: word-scoring pro-sanctions discourse

This article analyses the prevalence of the human rights, civil rights, and Cold War-driven anti-communist discourses through a word-scoring methodology which has hitherto been lacking within the scholarly literature. Jonathan Barry examines the motivations for supporters of the 1986 Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, but does not do so systematically, relying on interviews with key players and interpreting public statements.Footnote26 We analyze language associated with these concepts deployed by advocates of sanctions: grassroots campaign groups and Congress, as well as language reported about the campaign in the national press. We use a word scoring methodology, using primary sources found in the Congressional Record, campaign materials published by anti-apartheid groups, and articles written for national news outlets.

This project draws from three types of primary sources for its research: documented statements made by congressmen and senators during Congressional debates, published material circulated by pro-sanctions grassroots groups, and newspaper articles written by American broadsheets related to apartheid and the sanctions campaign.Footnote27 These have been chosen to offer a wide perspective on the motivations of a range of individuals involved in the campaign. The congressional sources reveal the salience of each discourse among the federal policymakers who proposed and later passed the CAAA. The grassroots sources represent the motivations and strategic language of those who led acts of education and protest, which ultimately led to apartheid becoming a nationally recognized issue. Materials are derived from both local chapters and nation-wide groups. The media has also been included, to act as a surrogate for how receptive the American public was to these different concepts. It should be noted that we are not considering the media as part of the sanctions movement itself. The media has been included in our research design to act as an additional measuring tool for how these different discourses permeated the general public’s observation of the sanctions movement, and our findings related to the media will therefore be discussed separately to the movement itself. Articles from news outlets associated with liberal politics, namely The New York Times and The Washington Post, and those with conservative leanings, namely The Wall Street Journal and The Economist have been chosen. Congressional statements were found within the Congressional Record,Footnote28 grassroots sources within the African Activist Archive (hosted by Michigan State University),Footnote29 and media sources through their online databases. Although we cannot say that the African Activist Archive is an entirely representative sample of the grassroots pro-sanctions literature (with stronger representation of the ACOA’s subsidiary organizations than those of TransAfrica), the attempt to gather thousands of primary sources in an effort to be as comprehensive as possible gives us reasonable confidence that we are capturing the dominant discourses of pro-sanctions campaign literature from the period.

Using these archives, a comprehensive index of sources was compiled based on matched search terms “South Africa,” “apartheid,” and “United States.” To allow for an even number of sources from different time periods and to help narrow the search results further, searches were made three times, once across the early part of the sanctions movement (1972–1976), once in the middle of the movement (1977–1983), and once in the late part of the movement (1984–1986), consistent with how scholars such as Meg Vorhees divide up the movement’s history.Footnote30 While dividing up the movement like this creates the issue of having some time periods being longer than others, doing so is necessary, as scholars such as Alvin Tillery have found a substantial lack of activity within the movement from 1977–1983, followed by a sharp increase in activity after 1984.Footnote31

From this population of results, a random sample of documents for each period was compiled, consisting of a quota of ten documents per type (media, Congress, grassroots groups) per period. To do this, sources were ordered from oldest to newest, and the total number of results divided by the number of sources needed from this search, with the result of this leading to the selection and analysis of every nth result, to maintain random selection. For example, if a search were to produce 62 results, where only ten sources were needed, every 6th result would be selected for analysis, always rounding down. However, it is important to note that some discretion was required, as the narrowed results field brought up sources which were either not relevant due to how sources are categorized (for example, a research paper circulated, but not written, by an anti-apartheid group), or a source was simply too short to be fairly compared against much longer sources (defined as <200 words). In these instances, the next source along was chosen instead, assuming that it was suitable and relevant. A source was deemed relevant if its primary focus was on the anti-apartheid movement, with the most common sources being speeches made to Congress on the topic, as well as campaign materials advocating sanctions, for example a pamphlet calling for a boycott of flights by South Africa Airways.Footnote32 However, given how this movement at times turned its attention to other minority-ruled African states such as Rhodesia, sources with this focus were still chosen if they discussed South Africa implicitly, for example a 1978 article titled “Aroused by Rhodesia” published in The Economist.Footnote33 Such sources still involved the same kind of actors on which this study focuses, and therefore the language involved will be consistent with language used to overtly discuss South Africa.

Once a primary source was selected, it was then matched against several pre-determined key words or phrases, to see the frequency of their use within the source, with each use being associated with the language of either human rights, civil rights, or anti-communism. These words have been chosen through preliminary research on sources which can be easily attributed to one of these three discourses and assessing the kind of language that they use to justify their opposition to issues including and related to apartheid. This method can be used to compile the most common words and phrases for each discourse, and their prevalence can then be assessed within the selected sources, with the frequency of their appearance being recorded accordingly. It is important to note that context and discretion is again important here, as a word or phrase may not appear exactly but should still be recorded (for example, “American interest” can appear instead as “the interest of Americans”). Conversely, words may appear exactly but in the wrong context and should therefore not be recorded (for example, the word “democratic” may refer to the Democratic Party). A full list of these words and phrases, as well as their relevant inclusions and exemptions, can be found in the Supplementary Appendix. Once all selected sources were analyzed, the results were compiled based on how often words from each discourse appeared across the different time periods, consistent with content analysis approaches from other scholars such as Amy Catalinac.Footnote34

Once the necessary sources were gathered and analyzed, the frequency of key words (specified in the codebook in the Supplementary Appendix) in each document was calculated and normalized to establish the prevalence of certain types of language irrespective of source length. The frequency of a term within a source was calculated by dividing its word count by 100, and then dividing the number of uses of a particular discourse by the changed word count, to give the frequency of discourse language per 100 words of the source, allowing for easier comparison of source data. For example, if a source contains ten uses of human rights language, and the source was 1,200 words long, then we divided ten by twelve, resulting in 0.83 occurrences of human rights language per 100 words of the source, with this process then being repeated for both civil rights and anti-communist languages. Therefore, the higher the frequency, the more often a certain type of language occurs and the stronger that hypothesis of that discourse dominance becomes. Once these calculations were done for each source, an average frequency was calculated to see the strength of different discourses across time periods and institutions. As mentioned previously, it was important to see not only whether different discourses fell in and out of favor in the sanctions movement between 1972 and 1986, but also how different perceptions of politics affected the salience of certain discourses. Data coming from congressional and grassroots sources were indicative of those actively part of the sanctions movement both at the elite and grassroots levels. Data coming from media sources were representative of how the sanctions movement was perceived by external actors and the public. Therefore, salience of a discourse in the media dataset measures not the motivations of the campaign itself but what kind of language resonated with the wider public at the time. In other words, the congressional and grassroots sources tell us what pro-sanctions advocates said. The media sources tell us what was heard.

5. Results

The data primarily demonstrated an early preference for civil rights language by all three groups. While in the media this continued into the late period as well, Congressional and grassroots activists diminished their use of civil rights language while increasing their use of anti-communist language by 1986. Additionally, the results demonstrate a lack of salience of anti-communism within the grassroots despite substantial use of this discourse by pro-sanctions members of Congress, demonstrating divisions within the movement itself. Finally, these results reveal that while human rights language increased in use around Carter’s election, it was soon replaced by anti-communism, and was therefore a short-lived phenomenon within the movement.

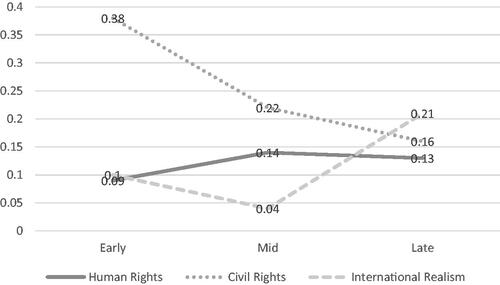

The results of the Congressional and grassroots sources (collectively referred to as “advocates”), presented in , found that from 1972 to 1976, the sanctions campaign had a clear preference for using civil rights language within the content of their activism, with an average frequency of 0.38 uses of civil rights terms per 100 words across this period. In contrast, anti-communist language had a frequency of 0.10, and human rights a frequency of 0.09, again showing this generally strong adherence to civil rights language in the movement. Significant changes occurred in the mid-period however, with civil rights remaining the dominant discourse but declining by nearly half to 0.22 and anti-communism declining to 0.04. Human rights is the only discourse to receive an increase in frequency in this period, rising to 0.14, but crucially the early period had a difference of 0.29 between its highest and lowest frequencies, whereas in the mid-period this decreased to 0.18, showing an overall more diverse range of languages being used by the sanctions movement (). By the late period, the frequency of civil rights language continued its decline, decreasing to 0.16; however, the frequency of human rights language was almost unchanged at 0.13, with anti-communism overtaking civil rights as the prevailing discourse, rising to 0.21. Additionally, the diversity of the movement’s language at this time became much more defined, with a difference of only 0.08 between the highest and lowest discourse frequencies, or less than a third of the difference from 1972–1976. The overall picture therefore shows an early dominance of the civil rights discourse in the movement, but this political space began to lose ground first to human rights and later to anti-communism. However, by the time of the CAAA’s passage in 1986 each discourse still had a core following within the movement, and so from this data none can be completely disregarded as not being at least somewhat relevant to its activism.

Figure 1. Change in average frequency for each discourse (advocate sources).

Table 1. Average discourse frequencies per 100 words from advocate sources.

It is important to see how salient each of these discourses were among the different advocates taken separately (). The sources from the Congressional Record show that while members of Congress favored anti-communist language overall, at a frequency of 0.19, the results from the other discourses were not substantially lower, with civil rights at 0.15 and human rights at 0.16. Therefore, these results do not show a clear preference for language in Congress when advocating for sanctions, which is consistent with the previous results, particularly with respect to the late period. Additionally, the data suggest that human rights were considered equally valid to the other, more established discourses among members of Congress, despite human rights not being considered “re-popularized” in mainstream American politics until Carter’s election.Footnote35

Table 2. Average frequency of each discourse from 1972 to 1986, per source.

Conversely, data generated by the grassroots sources displayed a preference for civil rights language at a frequency of 0.38, with human rights and anti-communism only slightly represented with frequencies of 0.08 and 0.03, respectively. This preference stems from these groups engaging frequently with many African liberation groups and advocating for greater American support of them, with just the terms “liberation” and “liberators” accounting for 45% of all civil rights language used in these sources. Such evidence suggests a strong presence of actors influenced by the civil rights movement within the grassroots of the sanctions movement, explaining the consistency of grassroots groups’ preference for civil rights language, neither of the other discourses reaching above a frequency of 0.12.

The data suggest that anti-communism was the most consistent of the three discourses. Its change in use by the sanctions movement occurred as expected: in the early period anti-communist language was rarely used but gained traction as the movement became more mainstream among right-wing members of Congress.Footnote36 Its position as the most favored type of language by the movement in the late period was also largely affected by an increase in its use by Congress. This also suggests that the role members of Congress played in the direction of the movement increased over time. In contrast, human rights was the least consistent discourse overall, as human rights language only received a relatively small increase in use between the early and mid-periods and stayed almost the same by the late period, despite Carter’s advocacy for human rights. It appears that while Carter’s election did correlate with an increase in human rights language among advocates, it was short-lived and soon overshadowed by anti-communist and civil rights language. The data on civil rights discourse among the activists themselves do not conform to how the sanctions movement is remembered. Civil rights was clearly the most dominant discourse within the early period of the movement, but gradually declined in use until it was replaced by anti-communism, yet never fell out of use by the movement completely.Footnote37 This suggests that civil rights lost ground over time, first to human rights and then to anti-communism, because the sanctions movement’s original advocates changed their language, and because newer members brought these other concepts into the movement as it grew over time, diluting the influence of those inspired by the civil rights movement directly.

Two general trends can be established. First, anti-communism was favored overall by members of Congress, and civil rights by grassroots groups. Human rights language was used by both of these sets of advocates while not being the cornerstone of either. This pushes against our proposition that a move to human rights discourse explains the CAAA’s passage. Secondly, anti-communism was the most favored type of language in the late period but not by a considerable margin, and so the diversity of the movement at this period may be responsible for why it saw so much success at this time, rather than a “triumph of realism” explanation ().

Figure 2. Average discourse frequency from 1972 to 1986, per source type.

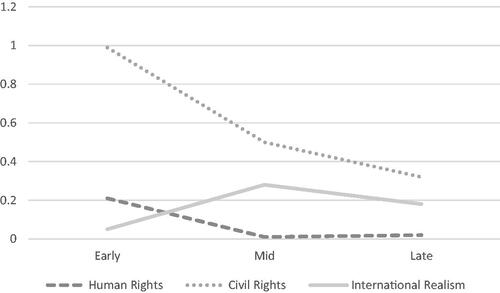

The data presented previously relate to the role that the different discourses played within the sanctions movement itself, but the following data is representative of sources from the mainstream media. Here, we are interested in how the media interpreted the movement’s activities between 1972 and 1986, and by extension how many in the American public would have learned about the movement. The data show that in the early period, civil rights language had a very high frequency in media reporting on the movement, at 0.99 per 100 words, with human rights by comparison at 0.21 and anti-communism at 0.05, showing a very clear preference by the media at this time for a civil rights framing (). However, in the mid-period there was a shift, with human rights declining to a frequency of 0.01 and civil rights almost halving to 0.50 but remaining the leading discourse, but in this same period anti-communism increased to 0.28. While in the early period the data from advocates taken together is similar to the data from media sources in this regard, in the mid-period the media diverged from how it portrayed the sanctions movement over how the movement actually spoke. The media increasingly framed the issue using anti-communist language despite the movement becoming more human rights-centered. In the late period, the media again diverged from the advocates, with civil rights and anti-communism decreasing to 0.32 and 0.18, respectively, and the frequency of human rights remaining low at 0.02. In all three periods, the media preferred to frame the movement’s activities with civil rights language. While these data show some diversity in how the media framed the movement, it still over-represented the influence of civil rights on the movement and almost ignores the influence of human rights language in this period, implying that the media saw the sanctions movement as an extension of the civil rights movement even as the CAAA was passed. Additionally, these data back up the assertion that Carter’s human rights advocacy only influenced members of Congress, and not only failed to resonate with grassroots groups but was also not salient with the media or the public.

Figure 3. Change in discourse frequency over time from media sources.

Therefore, the media either had clear preferences for which hypotheses they wanted to portray in terms of their influence on the sanctions movement, or the pro-sanctions actors interpreted and responded to political events differently to the media. This is evident from how civil rights was the prevailing discourse within the media sources in all three time periods, with anti-communism being represented in the late period but not shown to be as substantial an influence as the other sources, and human rights being largely ignored despite its salience within Congress. Additionally, it is interesting to note that the media’s overall preference for civil rights was higher than the preference that grassroots groups had, with the media having an average frequency of 0.6, compared to the average frequency of grassroots groups of 0.38. This is surprising given how many grassroots groups consisted of actors formerly involved with the civil rights movement, which suggests that the American media and public perceived the legacy of civil rights as being a more significant part of the sanctions movement than it was in reality.Footnote38 Additionally, the media data represented human rights in the same frequency as the grassroots sources did, with both holding a frequency of 0.08; however, when looking at anti-communism the media was much closer aligned with the congressional sources, with the media at 0.17 and Congress at 0.19. How these different representations of the different discourses came about will be key to further discussion.

6. Analysis: rights to realism

While human rights language did increase in use by sanctions advocates after Carter’s election, it was short-lived and was concentrated among political elites. We argue that this was due to the powerful legacy of the civil rights movement within the grassroots, and how human rights was soon overtaken by anti-communism among elites, to reflect the shift of Congressional Republicans to supporting sanctions.

6.1. The early period, 1972–1976

The most likely reason for civil rights’ dominance among activists in the early period is because of how involved figures from the civil rights movement were in the formation of pro-sanctions groups. For example, Congressman Walter Fauntroy had previously served as director of the Washington, D.C. branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, becoming a close friend of Martin Luther King and joining King’s 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. Fauntroy later staged a sit-in at the South African Embassy in Washington in protest of apartheid in 1984, and in turn helped create the Free South Africa Movement.Footnote39 This creates a direct link between the civil rights movement and the grassroots sanctions movement, as well as between Washington elites and grassroots activist organizations, lending to the idea of these separate entities working together as a semi-cohesive movement at this time.

Figures like Fauntroy are likely responsible for the salience of civil rights discourse among the movement’s grassroots; however, they do not necessarily explain why the media was more avid in its own use of civil rights language than activists themselves. The most likely explanation stems from the important role that the media played in the civil rights movement. Hersch and Shinall highlight how media reporting of police violence against civil rights protesters, for instance in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, was instrumental in convincing white Americans to support the civil rights movement, and even in motivating the Kennedy administration to send a draft civil rights bill to Congress.Footnote40 Therefore, by the 1970s, the media were aware of their ability to present civil rights to the American people in an accessible and sympathetic way. Involvement in early sanctions groups by civil rights figures would have been noticed by the media, who would have been keen to use this link to create a distinctly civil rights-focused narrative around the movement. However, the ideological language of activists at this time, as opposed to more tactical language that was seen in later periods, may also explain why sanctions were initially rejected when proposed by black politicians like Ron Dellums. A civil rights frame alone was inadequate to constructing a wide enough policy coalition to pass sanctions.

Therefore, both human rights and anti-communist language was overshadowed by civil rights in the early period, in terms of their salience among advocates. Human rights needed a proponent such as Carter to re-package the discourse in a manner which made it relevant to 1970s America. After World War II, human rights became perceived as a tool for international instead of domestic politics. Samuel Moyn attributes this to human rights’ association with the United Nations, which at the time was seen as lacking relevance to American politics.Footnote41 However, it is worth noting that this assertion may over-internationalize the concept of human rights. The distinction between human rights and civil rights is subtle and will be further addressed below. The Supplementary Appendix shows how words were sorted between the “civil rights” and “human rights” categories, while ultimately accepting that these distinctions are somewhat artificial.

Most members of Congress between 1972 and 1976 did not engage with the discourse of human rights, but notable exceptions include Senator Hubert Humphrey. Humphrey gave a speech to Congress in 1973, criticizing American policy toward South Africa, and this speech was steeped in human rights language. Humphrey first made his name at the 1948 Democratic Party Convention when he called Democrats to “get out of the shadows of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.”Footnote42 Upon closer inspection, Humphrey was an exception who helps to prove the rule. Few other congressional actors used similar human rights language in this early period.

6.2. The mid-period, 1977–1983

The results of the mid-period offer a notable contrast. This period sees civil rights remain the leading discourse, but the frequency of both it and anti-communism sees a sizeable decline. Human rights is the only discourse that sees a rise in use within the sanctions movement. Carter’s election did correlate with a rise in human rights language among sanctions advocates and particularly among members of Congress, largely at the expense of anti-communism which saw little use in Congress in this period, a legacy of Vietnam. Douglas Brinkley argues that Carter represented a successful resurgence of morally driven politics which was needed after the many human rights violations perpetrated during the Vietnam War, placing Moscow “…on the domestic defensive, in the process exposing the Soviet Union…as ‘evil’.” Human rights became an appealing alternative narrative to anti-communism for members of Congress to criticize oppressive regimes.Footnote43 It was during this period that some of the most egregious abuses of the white South African government occurred, including the brutal response to the 1976 Soweto uprising and the 1977 killing of Steve Biko by state security officers. These state-sanctioned crimes against humanity gave even Republican members of Congress reason to adopt human rights language. Yet, human rights discourse failed to extend to the grassroots anti-apartheid publications which largely continued to use civil rights language instead. This demonstrates a weakness in human rights discourse: that it was mostly salient among the upper levels of American politics at this time. Massie found that moderate Republicans in Congress held anti-apartheid views but failed to translate them into policy prior to 1984. Kansas Senator Nancy Kassenbaum, for example, argued in 1981 that apartheid violated fundamental rights, but then did little to address apartheid once she became chair of the Senate subcommittee on Africa. Massie argues that this is because there was little pressure from constituents for members of Congress to act on addressing apartheid on human rights grounds.Footnote44

Carter’s inconsistent approach to human rights may explain this. While his administration provided resources to members of Congress to promote human rights, they did not do the same for average Americans, abandoning plans for a dedicated government-funded human rights foundation to create a bridge between the administration and the grassroots.Footnote45 Such an overly top-down approach to human rights promotion, therefore, gave the grassroots few opportunities to engage with human rights. Our media analysis shows how little human rights was mentioned by the national press in this period, reinforcing the idea that human rights failed to extend its salience beyond the “Washington community.”Footnote46

6.3. The late period, 1984–1986

In the late period, civil rights language declined to no longer be the lead discourse among advocates, being overtaken by anti-communism. The media reports are considerably unrepresentative of the framings used by congressional and grassroots advocates. The increase in anti-communist language among advocates is the most notable change between the mid-period and this period and correlates with Congressional Republicans abandoning constructive engagement and supporting sanctions in enough numbers to pass the CAAA. While these Republican senators and congressmen were likely influenced by the movement’s gathering strength, they continued using their own anti-communist framing. Some were also convinced that the United States’ continued support of South Africa would impact American world leadership. Some Republicans only decided to support sanctions in response to South African President Botha attempting to intimidate Congress into voting down the CAAA, seeing this as unacceptable interference into American affairs.Footnote47 Other Republicans, including a young Newt Gingrich, saw the sanctions movement as an opportunity to convert “freedom fighters” in South Africa to anti-Marxism, and in turn convince other freedom movements around the world to move away from any links they had to communism, and instead align themselves with the United States.Footnote48 These Republicans brought new arguments and greater credibility to the movement, broadening its appeal, but did so in a way that did not overshadow the other discourses which existed within the movement or take away much of their “discourse space” (the idea that only a finite amount of ideological discussion can occur in a single political context, meaning that the success of one discourse can negatively impact the prevalence of another).Footnote49 This can be seen in how the frequencies of the three language types in this period are relatively similar.

The late period was overall characterized by anti-communism as the most used discourse, but this raises the question of what led to the decline of the previous lead discourse, civil rights, particularly given its dominance in the early period. Part of the answer to this has already been established: civil rights lost ideological ground among Congressional advocates to human rights in the mid-period, and to anti-communism in the late period. As has been highlighted, civil rights were always revered among the grassroots, and while this remained so in the late period, sanctions’ increased popularity invariably led to more white activists joining these groups, which created tensions with their predominantly black members.

In addition, liberation groups in South Africa sometimes raised concerns about the cynicism of US politicians trying to use the apartheid question as a civil rights issue for political gain at home. Massie details Edward Kennedy’s 1985 visit to South Africa. Black consciousness groups in the country (namely the Azanian People’s Organization, or AZAPO) protested and disrupted his visit. Kennedy was criticized for only visiting the country to improve his standings among black Americans, and the disruptions he faced meant that the trip was largely unsuccessful. It is likely that these arguments would have resonated back in the United States among black anti-apartheid activists, and in turn impacted how white activists were seen in the “late period.”

Sekou Franklin explains that many black activists in the 1980s criticized white activists for using civil rights language to criticize South Africa, but not to criticize America’s own issues with racism, prompting some white activists to form separate grassroots groups.Footnote50 These new groups used alternative narratives such as human rights to avoid this type of criticism, thereby decreasing the frequency of civil rights language among the grassroots in this period. This lends credence to the idea of there being a correlation between race and preferred discourse, but only when discussing purely the grassroots of the sanctions movement, and not necessarily in reference to elites.

Despite this change, the media did not abandon civil rights language to frame the movement, with it continuing to favor civil rights discourse, consistent with the two previous time periods. This again suggests that the media were unwilling to change how they framed the sanctions movement due to its links to the civil rights movement. The media reporting became increasingly inaccurate and understated the important role that anti-communism played in the passage of the CAAA, likely affecting public perceptions of the history of the sanctions movement.

7. Discussion and findings

Our research reveals that current understandings of the sanctions movement’s history are too focused on civil rights and neglect the diversity of discourses which were needed in Congress to pass the CAAA. Therefore, civil rights and human rights in an American context may have a more symbiotic relationship than scholars realize. Additionally, our research extends arguments made by Mary Dudziak, regarding the Cold War’s effect on the salience of civil rights in American politics.Footnote51 The scholarly impact of this research can be broken down into three key findings in how it relates to scholarly literature regarding the sanctions movement’s history, American civil rights, and understandings of human rights.

7.1. Finding one: current understandings of the history of the American sanctions movement have been shaped by the media and its preference for civil rights discourse

Reliance on media reports not only distorted understandings of the movement’s motivations, but also later historical research on the sanctions campaign. Footnote52 Many historians have used media reports as evidence instead of primary sources, including works by Klotz, by Barry, and by Fatton, which now require revision.Footnote53 Our research uncovers a neglected area of this history related to the motivations of members of Congress for passing the CAAA. In Congress, civil rights were one part of a larger coalition of discourses alongside human rights and anti-communism, which were needed to get the support in both chambers necessary to pass the CAAA against Reagan’s veto. This is particularly important to understanding why so many Congressional Republicans favored sanctions, as the previous history of the movement assumed that they opposed constructive engagement in civil rights terms, but this ignores how civil rights fitted into wider American politics at the time. National newspapers were largely written by media elites, yet their preferred discourse was aligned closely with the grassroots and not with fellow elites in Congress. This disconnect is a testament to the lasting legacy of civil rights on all levels of American politics, which scholars should be encouraged to engage with more robustly in this area of literature.

7.2. Finding two: American civil rights discourse stunted the growth of human rights discourse within the sanctions movement

The scholarly implications of this research extend to how we see the relationship between civil rights and human rights discourse, particularly within an American context. It was established that political figures such as Hubert Humphrey created a link between these two concepts, using them interchangeably to connect global inequalities with those seen in the United States. If Humphrey was able to do this in 1948, then Carter may have been able to accomplish the same thing after the 1976 election, and while he never made an explicit link within a famous speech like Humphrey did, his policies while president demonstrated an attempt to make an implicit connection. For example, Carter’s choice for UN Ambassador was Andrew Young, a civil rights veteran, who in turn spearheaded a careful strategy of nonviolent mediation to negotiate the transition of white-ruled Rhodesia to black-ruled Zimbabwe. Young used civil rights discourse to achieve Carter’s goal of a human rights-focused foreign policy.Footnote54 Young carried on using both human rights and civil rights discourses after he left his role as UN ambassador and took up his role as mayor of Atlanta in 1982. For example, in Young’s inaugural speech as mayor he criticized the Reagan administration’s approach to the civil war in El Salvador, claiming that Reagan was using a military approach when a human rights approach was needed.Footnote55

While Zimbabwe later developed its own human rights issues, the administration’s attempt at pursuing the moral foreign policy set out in Carter’s inaugural address using methods from the civil rights movement impacts how we see the relationship between these discourses within American politics. This is especially interesting with reference to Young himself, as he used an effective blend of human rights and civil rights discourses to achieve his goals. Young demonstrates how black elites may have been less averse to using rights discourses outside of civil rights than black grassroots activists were at this time, but this idea requires further research.

Carter’s foreign policy may have been more successful had he embraced civil rights explicitly, as he had access to an abundance of civil rights resources, something which he lacked when focusing solely on human rights. Their relationship is symbiotic, but regardless we have seen that civil rights was a more dominant discourse than human rights was at this time. Natsu Taylor Saito explains that this link comes from the United States’ political structure, which derives individual rights from a citizen’s group affiliations due to the country’s history with marginalized groups, but paradoxically, American political thinking demonizes collective rights over fears of their international nature leading to the “Balkanisation” of American society.Footnote56 Therefore, despite human rights’ salience elsewhere, the nature of American politics overly domesticates issues of rights, leading to human rights issues being framed as civil rights issues, which has stunted the growth of human rights discourse within the sanctions movement and wider American politics since the 1970s. In turn, civil rights are used as an alternative discourse in American politics due to its entrenched history, even when discussing foreign policy in which human rights usually dominate in other countries. Additionally, when rights were used in an international context at this time, it was often restricted to discussions surrounding communism and the Cold War, as we have discussed throughout this article. This strengthened said fear of Balkanization, and further restricted the development of human rights discourse.

This article also extends arguments made by Mary Dudziak in her book Cold War Civil Rights, namely that the civil rights movement must be placed in an international context to fully understand its history. Like Dudziak, we show that anti-communist imperatives continued to influence US racial policy, and demonstrate this influence in the construction of US foreign policy. As Republicans realized that constructive engagement was failing in South Africa, anti-communism emerged to frame their shifting strategic view of the apartheid regime.

7.3. Finding three: the lack of human rights’ salience within the grassroots of the sanctions movement demonstrates the difficulties of using the concept practically, and offers evidence against the idea of a human rights resurgence in the 1970s

Our findings are pertinent to contemporary human rights debates. One of these debates relates to Marie-Bénédicte Dembour’s “four schools” of human rights. The most relevant school to this article is the protest school, whose advocates believe human rights work best when utilized by grassroots movements as part of a constant struggle against injustices, and see human rights law as over-routinizing the concept, making it less effective.Footnote57 It is true that Carter’s poor attempts at re-introducing human rights to wider American politics, combined with his inability to use the discourse to engage with the grassroots, meant that human rights had less of an effect on the sanctions movement than it could have. Other human rights scholars contest that the concept has evolved to try be relevant to all global injustices, becoming too complicated in the process compared to other, more focused discourses like civil rights, stifling active engagement with the discourse and turning the politically active away from it.Footnote58 The relationship between grassroots advocacy groups and human rights, therefore, may require reevaluation.

Another area of human rights debate worth addressing relates to whether human rights truly reemerged as a major discourse in 1970s American politics, with Samuel Moyn contesting that it did. He claims that grassroots groups around the world and politicians of all stripes, including American politicians, were in full embrace of the UDHR at this time as issues that previously took discourse space away from human rights, such as decolonization, were beginning to be resolved, and a global community in need of a common language like human rights was forming.Footnote59 However, this article has found that while the human rights discourse was used by the sanctions movement in this period, it was overshadowed by domesticated civil rights language and anti-communism. Given that apartheid was a clear human rights issue, this casts doubt on whether a resurgence really occurred in the 1970s.

It must be said that these findings do not suggest that human rights were insignificant. We acknowledge that human rights were revered as a concept among other countries in the 1970s and the 1980s, including in South Africa itself amongst opponents of apartheid.Footnote60 Even inside the United States, the discourse helped to form the coalition in Congress needed to pass the CAAA, but its relative lack of salience among the American grassroots acts as a major challenge to Moyn’s ideas and the idea of human rights “breaking through” in 1970s global politics, given the United States’ crucial global political presence in this period. These findings therefore support arguments made by Hoffmann, who claims that the militant nature of the ANC in South Africa and wars in its neighboring countries at this time meant that discourse around apartheid was dominated by civil rights and anti-communism respectively, preventing human rights discourse emerging.Footnote61 The human rights framework present instead acted as the groundwork for a later human rights resurgence after the Cold War, and proved that human rights could exist in American foreign policy thinking. Human rights in turn became central to 1990s American foreign policy, and it was able to impart the moralistic nature of human rights to ordinary people in a way that Carter could not. For example, Kosovo’s Albanian population began to tie human rights to their ethnic identity following the US-led intervention there in 1999 to avert genocide, adding to the legitimacy of Hoffmann’s argument.Footnote62 This does beg the question of why the United States and South Africa had such different appreciations for human rights in the late Cold War period, and while this is outside the scope of this article, we encourage further research to answer this question.

8. Conclusion

This article reveals that the history of the sanctions movement and the motivations of its proponents were more complicated than commonly understood. It supports the idea of the civil rights movement being crucial to the sanctions movement’s growth in support from the 1970s, particularly through key figures involved in organizing both movements. However, our work diverges from common understandings by noting a shift away from civil rights language toward anti-communist language in the late period, as Congressional Republicans used this discourse to justify supporting sanctions despite the Reagan administration’s fears that sanctions would precede a communist takeover of South Africa. Conversely, human rights proved to have less of an impact on the movement than expected. Such findings impact how we see the overall history of the sanctions movement, as they show how much it has been shaped by the media’s preference for civil rights discourse, stemming from its frequent involvement with the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Portraying the sanctions movement in this way, however, ignores the variety of different motivations that advocates of sanctions had.

Overall, the findings tell us a great deal about both contemporary American politics and the practical applications of human rights, and how these two areas of political research interact. One particularly interesting consequence of this interaction is that despite the American sanctions movement not adopting human rights as boldly as we expected, its work nevertheless led to the end of apartheid and in turn a net global gain in respect for human rights. The divestment which came from the CAAA created momentum for anti-apartheid groups across the world to advocate for the same thing in their countries, leading to sanctions snowballing.Footnote63 United States foreign policy can, therefore, contribute to human rights improving in a country even if alternative narratives are being used as well.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (162.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (85.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samuel Mallinson

Samuel Mallinson was a graduate student in International Relations at Lancaster University.

Richard Johnson

Richard Johnson is a Senior Lecturer in US Politics and Policy at Queen Mary, University of London.

Notes

1 Dellums, Congressional Record.

2 Maloka, “Sanctions Hurt but Apartheid Kills,” 178–179.

3 Klotz, “Norms Reconstituting Interests,” 463–64.

4 Fatton, “The Reagan Foreign Policy Toward South Africa,” 57. It should be noted that scholars have attributed additional factors, including the importance of the Cape sea route, trade and investment, and racial (racist) solidarity with white South Africans.

5 Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions, 2–4; Massie, Loosing the Bonds, 601.

6 Moyn, The Last Utopia, 2–4.

7 The documentary “Have You Heard from Johannesburg” underlines the role Sharpeville played in internationalising the anti-apartheid movement. See also Frankel, An Ordinary Atrocity, 150–6.

8 Amnesty International, The Amnesty International Report, 74–6.

9 Lugar, Congressional Record, 107–8.

10 Fatton, “The Reagan Foreign Policy Towards South Africa,” 60–61. See also Coker, South Africa’s Security Dilemmas; Thomson, US Foreign Policy.

11 Vorhees, “The US Divestment Movement,” 130–3.

12 Hufbauer and Schott, “Economic Sanctions,” 728–9.

13 Zulu, “TransAfrica as a Collective Enterprise,” 38–9.

14 Minter and Hill, “Anti-Apartheid Solidarity, 747; See also Jolaosho, “Cross-Circulations and Transnational Solidarity,” 317–37; Bethlehem, Dalamba, and Phalafala, “Cultural Solidarities,” 143–52.

15 Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions.

16 Frank and Muriithi, “Theorising Social Transformation in Occupational Science,” 15.

17 Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line, 47–8.

18 Hoffmann, “Human Rights and History,” 281–2.

19 Haas, Sound the trumpet, 34.

20 Donnelly and Whelan, “The West, Economic and Social Rights,” 919–20.

21 Porsdam, “From ‘rights talk’ to ‘human rights talk’,” 168–9.

22 Barbara Keys, Reclaiming American virtue, 1–2.

23 Kenneth Cmiel, “The Emergence of Human Rights Politics,” 1235.

24 Keys, Reclaiming American virtue, 181.

25 Jacoby, “The Reagan Turnaround on Human Rights,” 1075–6: Guilhot, The Democracy Makers.

26 Barry, “Deconstructing Constructive Engagement,” 327–49.

27 For a full list of these sources, see the Online Supplementary Appendix.

29 https://africanactivist.msu.edu/. See also Knight, “The African Activist Project,” 4–6.

30 Vorhees, “The US Divestment Movement,” 130–7.

31 Tillery Jr., Between Homeland and Motherland, 135.

32 “Come to South Africa Where You Can Expect the Unexpected…” (March 1985), Campaign to shut down South Africa Airways.

33 “Aroused by Rhodesia,” The Economist, August 5th, 1978.

34 Catalinac, “From Pork to Policy,” 7–8.

35 Keys, Reclaiming American Virtue, 1–2.

36 Klotz, “Norms Reconstituting Interests,” 466.

37 Zulu, “TransAfrica as a Collective Enterprise,” 38–9.

38 Nesbitt, Race for Sanctions, 42.

39 https://history.house.gov/People/detail/13023 (Accessed 27th July 2020).

40 Hersch and Shinall, “Fifty Years Later,” 428.

41 Moyn, The Last Utopia, 150.

42 Murphy, “The Sunshine of Human Rights,” 93.

43 Brinkley, “The Rising Stock of Jimmy Carter,” 522.

44 See Massie, 497–8.

45 Hartmann, “US Human Rights Policy,” 413–5.

46 Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents.

47 Nesbitt, Race for sanctions, 142.

48 Clough, “Southern Africa,” 1071.

49 Cap, ‘Studying Ideological Worldviews in Political Discourse Space,” 18.

50 Franklin, After the Rebellion, 88–9.

51 Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights, 14–5.

52 Klotz, “Norms and Sanctions,” 180.

53 Fatton, “The Reagan Foreign Policy Toward South Africa,” 64–5.

54 Deroche, “Standing Firm for Principles,” 658–9, 684–5.

55 Deroche, Andrew Young, 124–5. Deroche, “Andrew Young and Africa,” 197, details that in 1985 Young testified to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee regarding possible sanctions on South Africa, who argued that sanctions would allow moderate white South Africans to push for an end to apartheid. Deroche argues that this was an extension of Young’s civil rights background, and an extension of “King’s philosophy on to the world stage.” Therefore, both discourses were used by Young even in his post-ambassador career.

56 Saito, “Beyond Civil Rights,” 409–11.

57 Dembour, “What are Human Rights?,” 3.

58 O’Neill, “The Dark Side of Human Rights.” 436–7.

59 Moyn, “The Return of the Prodigal,” 5–6.

60 On the complexities of this history, see Dubow’s South Africa’s Struggle.

61 Hoffmann, “Human rights and history,” 288.

62 Mertus, “The Impact of Intervention on Local Human Rights Culture,” 24.

63 Bueckert, “Boycotts and Revolution,” 107.

References

- Amnesty International. The Amnesty International Report, 1975–1976. London: Amnesty International, 1976.

- Barry, Jonathan. “Deconstructing Constructive Engagement: Why Did a Republican Senate Undermine a Republican President?” Safundi 8, no. 3 (2007): 327–49.

- Bethlehem, Louise, Lindelwa Dalamba, and Uhuru Phalafala. “Cultural Solidarities.” Safundi 20, no. 2 (2019): 143–52.

- Brinkley, Douglas. “The Rising Stock of Jimmy Carter: The “Hands on” Legacy of Our Thirty-Ninth President.” Diplomatic History 20, no. 4 (1996): 505–30.

- Borstelmann, Thomas. The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Bueckert, Michael. “Boycotts and Revolution: Debating the Legitimacy of the African National Congress in the Canadian anti-Apartheid Movement, 1969–94.” Radical History Review 2019, no. 134 (2019): 96–115.

- Cap, Piotr. “Studying Ideological Worldviews in Political Discourse Space: Critical-Cognitive Advances in the Analysis of Conflict and Coercion.” Journal of Pragmatics 108 (2017): 17–27.

- Catalinac, Amy. “From Pork to Policy: The Rise of Programmatic Campaigning in Japanese Elections.” The Journal of Politics 78, no. 1 (2016): 1–18.

- Clough, Michael. “Southern Africa: Challenges and Choices.” Foreign Affairs 66, no. 5 (1988): 1067.

- Cmiel, Kenneth. “The Emergence of Human Rights Politics in the United States.” The Journal of American History 86, no. 3 (1999): 1231.

- Coker, Christopher. South Africa’s Security Dilemmas. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 1987.

- Dellums, Ronald. “Congressional Record (Bound) 118.” June 18, 1986, 57.

- Dembour, Marie-Bénédicte. “What Are Human Rights? Four Schools of Thought.” Human Rights Quarterly 32, no. 1 (2010): 1–20.

- Deroche, Andrew. “Standing Firm for Principles: Jimmy Carter and Zimbabwe.” Diplomatic History 23, no. 4 (1999): 657–85.

- Deroche, Andrew. Andrew Young: Civil Rights Ambassador, 124–5. New York: Roman & Littlefield, 2003.

- Deroche, Andrew. “Young and Africa.” In Globalization and the American South, ed. J. Cobb and W Stueck, 197. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005.

- Donnelly, Jack, and Daniel Whelan. “The West, Economic and Social Rights, and the Global Human Rights Regime: Setting the Record Straight.” Human Rights Quarterly 29, no. 4 (2007): 908–49.

- Dubow, Saul. South Africa’s Struggle for Human Rights. Columbus: Ohio University Press, 2012.

- Dudziak, Mary. Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy, 14–5. Princeton: Princeton University, 2011.

- Fatton, Robert. “The Reagan Foreign Policy toward South Africa: The Ideology of the New Cold War.” African Studies Review 27, no. 1 (1984): 57.

- Frank, Gelya, and Bernard Muriithi. “Theorising Social Transformation in Occupational Science: The American Civil Rights Movement and South African Struggle against Apartheid as ‘Occupational Reconstructions.” South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 45, no. 1 (2015): 11–9.

- Frankel, Philip. An Ordinary Atrocity: Sharpeville and Its Massacre. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Franklin, Sekou. After the Rebellion: Black Youth, Social Movement Activism, and the Post-Civil Rights Generation, 88–9. New York: New York University, 2014.

- Guilhot, Nicolas. The Democracy Makers: Human Rights and the Politics of Global Order. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Hartmann, Hauke. “US Human Rights Policy under Carter and Reagan, 1977–1981.” Human Rights Quarterly 23, no. 2 (2001): 402–30.

- Haas, Lawrence. Sound the Trumpet: The United States and Human Rights Promotion. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012.

- Hersch, Joni, and Jennifer Shinall. “Fifty Years Later: The Legacy of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 34, no. 2 (2015): 424–56.

- Hoffmann, Stefan-Ludwig. “Human Rights and History.” Past & Present 232, no. 1 (2016): 279–310.

- Hufbauer, Gary, and Jeffrey Schott. “Economic Sanctions and U.S. Foreign Policy.” Political Science & Politics 18, no. 4 (1985): 727–35.

- Jacoby, Tamar. “The Reagan Turnaround on Human Rights.” Foreign Affairs 64, no. 5 (1986): 1066.

- Jolaosho, Omotayo. “Cross-Circulations and Transnational Solidarity.” Safundi 13, no. 3–4 (2012): 317–337.

- Keys, Barbara. Reclaiming American Virtue: The Human Rights Revolution of the 1970s, 1–2. Cambridge: Harvard University, 2014.

- Klotz, Audie. “Norms Reconstituting Interests: Global Racial Equality and U.S. Sanctions against South Africa.” International Organization 49, no. 3 (1995): 451–478.

- Klotz, Audie. “Norms and Sanctions: Lessons from the Socialization of South Africa.” Review of International Studies 22, no. 2 (1996): 173–190.

- Knight, Richard. “The African Activist Project: Preserving the History of the Solidarity Movement.” Peacework 35, no. 382 (2008): 4–6.

- Lugar, Richard. “Congressional Record (Bound) 118.” October 2, 1986, 107–8.

- Maloka, Tshidiso. “Sanctions Hurt but Apartheid Kills: The Sanctions Campaign and Black Workers.” In How Sanctions Work, eds. Crawford and Klotz , 178–9. London: Macmillan, 1999.

- Massie, Robert. Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years. New York: Doubleday, 1997.

- Mertus, Julie. “The Impact of Intervention on Local Human Rights Culture: A Kosovo Case Study.” The Global Review on Ethnopolitics 1, no. 2 (2001): 24.

- Minter, William, and Sylvia Hill. “Anti-Apartheid Solidarity in United States-South Africa Relations.” In The Road to Democracy in South Africa, eds. L Stewart and B Theron, vol. 3, 747. Pretoria: Unisa, 2008.

- Moyn, Samuel. The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Moyn, Samuel. “The Return of the Prodigal: The 1970s as a Turning Point in Human Rights History.” In The Breakthrough: Human Rights in the 1970s, eds. Jan Eckel and Samuel Moyn, 5–6. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

- Murphy, John. “The Sunshine of Human Rights: Hubert Humphrey at the 1948 Democratic Convention.” Rhetoric & Public Affairs 23, no. 1 (2020): 93.

- Nesbitt, Francis. Race for Sanctions: African Americans against Apartheid, 1946–1994. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Neustadt, Richard. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. New York: The Free Press, 1990.

- O’Neill, Onora. “The Dark Side of Human Rights.” International Affairs 81, no. 2 (2005): 436–7.

- Porsdam, Helle. “From ‘Rights Talk’ to ‘Human Rights Talk’: Transatlantic Dialogues on Human Rights.” In Europe and the Americas: Transatlantic Approaches to Human Rights, eds. Erik Andersen and Eva Lassen, 168–9. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2015.

- Saito, Natsu. “Beyond Civil Rights: Considering “Third Generation” International Human Rights Law in the United States.” The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 28, no. 2 (1997): 409–11.

- Thomson, Alex. US Foreign Policy towards Apartheid South Africa, 1948–1994. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

- Tillery, Alvin. Jr., Between Homeland and Motherland: Africa, U.S. Foreign Policy, and Black Leadership in America.” Ithaca: Cornell University, 2011.

- Vorhees, Meg. “The US Divestment Movement.” In How Sanctions Work: Lessons from South Africa, eds. Crawford and Klotz , 130–3. London: Macmillan, 1999.

- Zulu, Itibari. “TransAfrica as a Collective Enterprise: Exploring Leadership and Social Justice Attentiveness.” The Journal of Pan-African Studies 8, no. 9 (2015): 38–9.