ABSTRACT

Graffiti is an important theme for our understanding of subcultural urban space and the ‘shadows’ of the city. This paper examines their spatial concentration in Holešovice district of the Czech capital Prague. Four theories have been used to explain the spatiality of graffiti: territorial markers, broken window, spot theory, and political symbolic space. While the first three theories all explain the spatial distribution of graffiti, they are each limited when applied to political graffiti. Conversely, the theory of political symbolic space, based on David Harvey’s relative space and Henri Lefebvre’s representational space, helps explain the concentration of political graffiti.

Introduction

Graffiti is still a controversial topic for many people, including social scientists (Ross et al. Citation2017). Street art (an artistic form of graffiti) has become well-known and respected by the broad masses, and is today an increasingly popular sight in many cities (Wacławek Citation2011), sometimes ordered by local governments themselves. Yet traditional and simpler forms of graffiti are still perceived largely as criminal vandalism (Gomez Citation1993; Halsey and Young Citation2002; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011; Ross et al. Citation2017). Many people assume the creators are or will become criminals, however on the contrary, they quite often become respected artists or designers (Snyder Citation2009).

Graffiti in the form of inscriptions has been known to mankind since the ancient times (Megler, Banis, and Chang Citation2014). The modern graffiti scene appeared in the 1970s in New York, Philadelphia, and other American cities as part of a wider subcultural movement. At this time the first social-scientific articles on the topic also appeared, which highlighted the importance of graffiti for human geography (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974). Its importance lies in its contribution to an understanding of urban space and the processes that take place in the ‘shadows’ of the city that may not at a first glance be apparent. However, although the topic of graffiti itself has already become legitimate, increasingly studied, and conceptualized (Ross et al. Citation2017), only a few authors approach the research of graffiti placement spatially (e.g. Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson Citation2013; Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974; Megler, Banis, and Chang Citation2014). Actually, the interaction between the graffiti and its environment is significant because graffiti often reacts on the urban place where it is written (Wacławek Citation2011). Paradoxically, while there is a spatial effort to make the message visible to the widest circle of target people, there is a simultaneous effort to hide the illegal creation of graffiti (Alonso Citation1998).

Urban space is a traditional and still current topic of urban geography, which combines a wide range of diverse social-scientific approaches exploring the factors of its urbanistic, economic, and social development. However, there are further dimensions on which the understanding of city complexity, correct identification of problems and formulation of appropriate political solutions depend (Harvey Citation2009). One of these dimensions is the political one (Abraháo Citation2016), which also includes political expressions like graffiti. Despite its consistent and dominant focus on lifestyle and attitude towards society, it is well known that graffiti may also contain a strong and easily comprehensible political component (Iveson Citation2009; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011). Graffiti is a subcultural expression by which people otherwise not involved in democratic dialogue can express themselves (Iveson Citation2009) and point out their own problems in a pure form (Ross et al. Citation2017). As such, political graffiti is a specific type of graffiti (Alonso Citation1998; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011; Zaimakis Citation2015), that can reveal the functioning of democracy and the city itself.

Urban space is both a base and a tool for political expression, which can speak to the decision-making of politicians from the local to the international level. In this context, it is essential to perceive spatial differences in expressing political ideas, but it is also important to know how the city space itself affects these political expressions (see Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011). Graffiti exhibits a clear spatiality in its realisation (e.g. Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson Citation2013). Academics (e.g. Ferrell and Weide Citation2010; Kelling and Wilson Citation1982; Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974) have attempted to explain this with several theoretical concepts. Political graffiti are likely to be influenced by the political symbolic space of the city, which is one of many symbolic spaces (cf. Daněk Citation2013). Political symbolic space, at the social-scientific level, is based on the concept of relative space by David Harvey (Citation2009) and representational space by Henri Lefebvre (Citation1991), who saw space as actively created and variable, overlapping physical space and symbolically using its objects. Anchoring political expressions like political graffiti in political symbolic space seems to be crucial to understanding their spatial pattern (see Parkinson Citation2012).

The aim of this article is to study the spatial distribution of different types of graffiti in a selected district of the Czech capital city Prague. The main research question is how and with which theories can we explain the spatial distribution of political graffiti. To do so we apply pre-existing spatially oriented theories used to explain graffiti as well as the theory of political symbolic space. Political graffiti is associated with critical social events in democratic societies, not with everyday life (Alonso Citation1998). The much discussed current issue of a divided/polarised Czech society (Pehe Citation2018; Rupnik Citation2018), which reflects for example the emphasis on the promotion of national interests and opposition to EU policy, is not so strong a social background for political graffiti creation as for example, the Greek economic crisis (Alexandrakis Citation2016; Zaimakis Citation2015), Argentinian economic crisis (Kane Citation2009), religious conflict in Northern Ireland (Goalwin Citation2013), or Israeli-Palestinian relations (Hanauer Citation2011). Nevertheless, it could still lead to a large amount of political graffiti in Czech cities, mainly in the capital city of Prague as the Czech political centre. In Czechia, not much scientific attention has been paid to graffiti at all. Research on alternative spaces (Pixová Citation2007, Citation2013) is closest to this theme but it examines political expressions as part of a broader struggle against the current socio-economic system.

This article attempts to contribute to both current research on graffiti with a new, interesting and still unexplored locality, and to the conceptualization and understanding of the form and functioning of political symbolic space, which has a wider application for research on other political activities in the city.

Spatial conditionality of (political) graffiti and political symbolic space

Graffiti in its modern day form emerged in the 1970s, especially in New York City and Philadelphia, where new types of graffiti were created by inner-city youths to express new socio-cultural trends (Kelling and Wilson Citation1982; Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974; Wacławek Citation2011). On the opposite coast of the United States, like in Los Angeles, the graffiti scene in the 1970s was quite different (Ross et al. Citation2017), with street art creations largely responding to actual political issues (Romotsky and Romotsky Citation1976). Before the rise of this new phenomenon, academics had written papers about traditional or historical types of graffiti writings, like political, intellectual, or sexual (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974). However the 1970s witnessed a qualitative change in graffiti making, as it became a cultural phenomenon. The first academic papers about new spray-paint graffiti took into account different cultural backgrounds and messages which it described as ‘folk symbols or slogans’ (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974). Nowadays, graffiti is a theme of many social scientific fields of study including 1) the graffiti writers from a sociological (Andersen and Krogstad Citation2019; Keizer, Lindenberg, and Steg Citation2008), psychological (Aneshensel and Sucoff Citation1996; Baker Citation2015) or ethnographic point of view (Bloch Citation2018; Fransberg Citation2019; Kindynis Citation2018; Zaimakis Citation2015), 2) reactions of the public (in sociological or criminological way), including the creation of fear in citizens (Doran and Lees Citation2005; Lagrange, Ferraro, and Supanic Citation1992) or citizens’ view on graffiti across a spectrum that ranges from art to vandalism (Cresswell Citation1992; Gomez Citation1993; Halsey and Young Citation2002; Ten Eyck Citation2016; Vanderveen and Van Eijk Citation2016); and, 3) the graffiti creations themselves by linguistic, discourse, or semiotic analysis of graffiti messages (Blommaert Citation2016; Debras Citation2019; Goalwin Citation2013; Hanauer Citation2011; Kane Citation2009; Serafis, Kitis, and Archakis Citation2018; Zaimakis Citation2015) or analyses of their visual aspects (Christensen and Thor Citation2017; Gartus, Klemer, and Leder Citation2015; Wacławek Citation2011).

Urban graffiti used as territorial markers by gangs was first conceptualised as a spatial marker in the 1970s, when it was shown that graffiti is used by individuals or groups to mark territory according to the neighbourhood or ethnicity (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974; Walker and Schuurman Citation2015). At the borders of such territories, the graffiti of two different groups intertwine often in a high concentration, indicating a very aggressive tactic of claiming territory and warning that someone is already ‘in control’ here (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974). However, this concept is widely applicable only in cities with strong criminal gangs or ethnicity-based conflicts. The broken window theory deals generally with the concentration of degrading activities in urban spaces. Accordingly, just one broken windowpane (or disorderly behaviour like graffiti on a wall) can give the impression that no one cares about the urban place and can activate further degradation activities (Keizer, Lindenberg, and Steg Citation2008; Kelling and Wilson Citation1982).

However, if we apply both of these theories to the issue of graffiti, it leads to a misinterpretation of graffiti as only an indicator or even a direct factor in the social deprivation of the urban space. This limits the perception of other aspects of this phenomenon, and reflects a lack of understanding of graffiti culture (Walker and Schuurman Citation2015). The practical political implication is that this can then lead to an unreasonable, general struggle against graffiti, which often results in spending unnecessary amounts of money, in removing graffiti irrespective of its artistic value, and in moving the problem to other locations (Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson Citation2013). It can also lend indirect support to the production of fast and low-quality works (Ferrell and Weide Citation2010). We can then assume that the result of the continual removal of graffiti in urban districts could be the concentration of simpler forms of graffiti.

Conversely, spot theory holds that the site selection for graffiti is dependent on its visibility in the urban environment, which indicates that increased graffiti concentration does not necessarily mean social deprivation (Ferrell and Weide Citation2010). Above all the creator wants to be seen, so some spots are more appreciated in the graffiti community than others, such as billboards, overpasses, railway bridges, and other busy communication routes (Ferrell and Weide Citation2010). Spot theory thus creates a simplified view of graffiti as a disorderly form of vandalism and, on the contrary, highlights the perception and importance of the space in which it is created (Walker and Schuurman Citation2015).

Graffiti conveys a message or contributes to public space with a clear content (e.g. Debras Citation2019; Snyder Citation2009; Zaimakis Citation2015). Political graffiti, which highlights a political understanding, social commentary, criticism, protest, rejection, or agreement with social changes (Zaimakis Citation2015), is a great example of how people excluded from traditional political dialogue can express their political ideas (Iveson Citation2009). In graffiti concentration research using spot theory, it is important to understand the writers’ perception of space. However, only a few researchers have attempted to explain the spatial concentration of political graffiti. For example, Walker and Schuurman (Citation2015) show that graffiti writers often mark property that represents the political system against which they define themselves. Megler, Banis, and Chang (Citation2014) claim that graffiti expressing a strong view against the current structure of power can be expected to be created near a police station or in areas where high-income residents live. However, research is yet to explore how creators of political graffiti can use the notion of the political importance of certain places (as presented in the case of demonstrations, see Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010), which is related to political symbolic space (based on Harvey Citation2009; Lefebvre Citation1991). In the literature, we find several works that mention or allude to the symbolism of the place in the creation of political graffiti (e. g. Gagliardi Citation2020; Pugh Citation2015; Waldner and Dobratz Citation2013; Zaimakis Citation2015); however these works do not primarily examine spatial differences in political symbolism and their influence on the concentration of political graffiti.

Anchoring political expressions (including graffiti) in the political symbolic space of the city seems to be crucial to understanding their spatial pattern (see Harvey Citation2012; Parkinson Citation2012; Pixová Citation2007). Without this symbolic level of reality, space is otherwise researched as something absolute and fixed, which is quite a technocratic point of view (representation of space as mentioned by Lefebvre Citation1991). It can become a completely independent basis for research of spatial relations and phenomena (absolute concept of space by Harvey Citation2009), as we see in some theories explaining spatial patterns of graffiti (Walker and Schuurman Citation2015). There is thus a risk that an important dimension of reality is excluded from the interpretation.

All space has its symbolism which simultaneously affects and is created by the everyday life of its inhabitants and changes over time. According to David Harvey’s concept of relative space, it is important to perceive space as a result of the relations between objects ‘which exists only because objects exist and relate to each other’ (Harvey Citation2009, 13). Therefore, every relational process in the space defines its own spatial frame which is actively created by its objects and is variable in time (Harvey Citation2006, pp. 272–273). However, the content of this basic framework must be filled by the production of space, given the relations between the inhabitants and their city. In the view of Henri Lefebvre’s representational space, which is directly lived by inhabitants and users through associated images and symbols, it is a space that the imagination seeks to change and appropriate. It overlays physical space and symbolically uses its objects. As a result, this notion of space makes a spatial system of non-verbal symbols and signs (Lefebvre Citation1991, 39). If we want to understand the spatial context of any social phenomena, we must observe this space as a social product (Kindynis Citation2018) in which graffiti is located and with which it interacts.

We can thus understand political symbolic space (as one of many symbolic spaces, see Daněk Citation2013) as a relative space created by the relations between political objects in the widest sense which, like representational space, is composed and influenced by the political ideas and experiences of its users and by specific political symbols. Some of the objects which could influence this relative space and produce symbols for users of representational space include: 1) political buildings and urbanism (Parkinson Citation2012; Taha Citation2016), 2) political memorials (Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010), 3) politically important public spaces created by political experience or significant political moments of history, which is thus very closely related to the public identity (Liu and Hilton Citation2005; Paasi Citation2003), and, 4) experienced space (Daněk Citation2013), made up by live political activity or political expressions like demonstrations (Císař, Navrátil, and Vráblíková Citation2011; Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010), political activism as ‘the right to the city’ concept shows (Harvey Citation2012; Iveson Citation2013; Lefebvre Citation1996; Swyngedouw and Heynen Citation2003), and graffiti creation (Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson Citation2013; Iveson Citation2009; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011). All of these contribute in some way to the form of political symbolic space and likewise, this political symbolic space can influence the distribution of political symbols in the real space of the city, as mentioned in the example of demonstrations (Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010). The creators of political expressions use a certain symbolism of the place to attract the attention of the majority society (Alonso Citation1998), but also to give their expressions greater weight (Lee, Kim, and Wainwright Citation2010). This may explain why political expressions are concentrated in certain parts of the city (Abraháo Citation2016), which thereafter could become known as the place(s) where certain expressions are traditionally performed.

Research area and survey methods

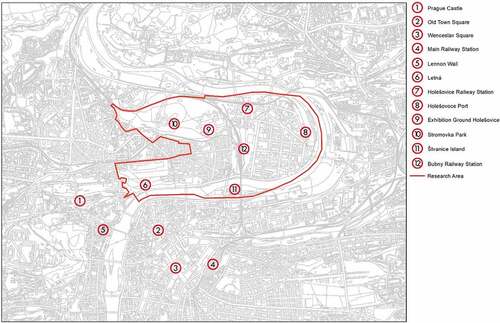

Field research was carried out in a selected area of the Prague district of Holešovice (see location near the city centre in ),Footnote1 based on the methodological approach of local scale analysis by Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson (Citation2013) who looked for graffiti hotspots and tried to find their conditionalities. In Czechia, graffiti became prominent after the fall of communism in 1989 (Overstreet Citation2006). To begin with, municipalities followed a zero-tolerance policy, but gradually they allocated legal walls (places where artists can freely display their talent, without sanctioning) or even contracted street art performances in some neglected areas (Kolláriková Citation2019). These are common, alternative fighting approaches against unsightly forms of graffiti (Shobe and Conklin Citation2018). Examples can be found in the research area, like at Bubny Railway Station (Kolláriková Citation2019; Radical East Side Citation2018).

In the context of Prague, Holešovice is a district in which, due to the relative heterogeneity of its urban structure, an interesting differentiation in the occurrence of graffiti can be observed. In its western part, the Letná Plain is important in respect to political symbolic space (in , blank space around number 6). After the establishment of Czechoslovakia in 1918, the Letná Plain was chosen as the location of the new government and Parliament buildings, partly because it was in sight of Prague Castle, the residence of the Czechoslovak (now Czech) president. The buildings however, were never built because of many internal reasons (Brůhová Citation2017). Later during the Communist regime, the May Day and military parades, which were held to consolidate the totalitarian regime, took place at Letná Plain. In 1989 during the Velvet Revolution these parades were replaced by mass protest against the Communist regime. The plain is also the place where massive, contemporary political protests have been held against the controversial government of the business firm party ANO 2011 of Andrej Babiš (Kopeček Citation2018; for definition, see Hopkin and Paolucci Citation1999) and populist president Miloš Zeman (Naxera and Krčál Citation2020). The selected research district also includes the offices of municipal and state level authorities (most notably the Ministry of Interior at Letná), a few foreign embassies, and the seat of the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems Agency (GSA).

Letná also has an important subcultural centre with its famous DIY skatepark (see Surfergalaxy Citation2020), located at the site of the former Stalin monument which was built in 1955 and destroyed by the Communist regime in 1962. On the pedestal of the former monument, the Metronome was erected in 1991 as a reminder of the place’s history and the Velvet Revolution (right under number 6 in ). We could expect a concentration of graffiti as a form of subcultural expression here (see Iveson Citation2009; Taylor and Marais Citation2011). Across a wide belt of its central part, Holešovice also includes extensive brownfield and other neglected sites (Bubny Railway Station, Holešovice Railway Station, Štvanice Island), where graffiti is likely to occur in accordance with broken window theory. A large area of this former industrial district (mainly the eastern part) is now gentrified, especially in the area of the former Holešovice Port, where new office and housing buildings have been built and old industrial and housing buildings reconstructed for new purposes.

The area of Stromovka Park and Exhibition Ground Holešovice has been added to the research area because, though belonging to the neighbouring Bubeneč district, it is publicly perceived as a part of Holešovice district (as evidenced by the name of the Exhibition Ground). The addition of this area allows for an interesting comparison of the occurrence of graffiti in Stromovka Park and Letná Plain. Both are popular parks though they are of different character. Whereas Letná has a strong symbolic place in politics, hosts an important subcultural centre and serves a recreational function, Stromovka is a classic recreational city park.

Contemporary academic literature on graffiti includes many definitions and typologies, which often fundamentally differ because of their inclusion or neglect of different aspects of graffiti creation (see Ross Citation2016, 1–3). Therefore, it is difficult to adopt one established definition of graffiti and one typology that would be suitable for research in the context of Prague. First, we clarify how we understand graffiti. To capture the entire subcultural graffiti and related scenes, we have included all forms of graffiti creation mentioned by McAuliffe (Citation2012), such as traditional spray or marker, but also new forms of reverse graffiti (created by use of cleaning fluids on dirty surfaces), glued 3D objects, cup-rocking (coloured plastic cups in fences), scratchiti (etched and scratched on glass and plastic surfaces), stickers, illegal posters, and paste-ups (paper objects glued on walls). From a methodological point of view the method of creation is not essential, because we are mainly interested to observe the relationship between the concentration of political graffiti as a general type of subcultural political message and the political symbolic space.

For the needs of our field survey and in accordance with the context of Prague’s graffiti scene, we adapted two existing typologies of the content and overall appearance of graffiti which include political graffiti (Alonso Citation1998; McAuliffe and Iveson Citation2011). We consolidate them into a typology which is wide and structured enough to both include all graffiti types occurring in Prague and to properly illustrate their spatial differentiations. The typology includes: 1) existential graffiti (with some existential message), 2) tagging (sprayer signature), 3) piecing and gang graffiti (more graphically complicated text; both types are in one category because they are both difficult to create and because gang graffiti is not relevant in the context of Prague, cf. Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974), 4) political graffiti, 5) hip hop graffiti (expressively colourful, complex, often with a black background), and 6) street art (artwork made as graffiti). Political graffiti is listed as a separate type in the above typology even though graffiti of other types can include a political message (like tagging or street art that refers to a political figure or event, see Zaimakis Citation2015). In these exceptional cases, graffiti have been attributed both to the basic type in the general typology and also as a type of political graffiti. Therefore, we distinguish between political graffiti and non-political street art through the visual and content aspects rather than through the material of creation aspect as explained above (cf. Ross Citation2016).

The main concern of this paper is political graffiti, so we also created a more detailed typology that reflects different types of political messages divided by their generality or specificity and hierarchical levels (rather than by the degree of ideological motivations of the creators which could be unsuitable in the Prague context, cf. Zaimakis Citation2015). This includes: 1) expression of general political attitude and ideology (e.g. anarchism, nationalism, communism, anti-communism, environmental movement), which includes memorial expressions as well (e.g. fall of communism, historical personalities who became national symbols like Jan Palach, Milada Horáková or deceased politicians like Václav Havel); 2) expression of resistance (or support) to specific political and state institutions or to persons in politically important positions (e.g. police, parliament, government, president, still politically active persons like former president Václav Klaus); 3) expression of opposition to a specific political decision and process, which can be divided into: a) local (e.g. construction in a park, planned demolition of a relic); b) national (e.g. reduction of social benefits, construction of a specific highway, construction of a nuclear power plant); c) international and global (e.g. TTIP agreement about free trade between the USA and the EU, activities of own state in international organisations like the EU or NATO, activities of a global political player like the USA or their president).

The field survey was carried out in March-July 2019. Only graffiti that was visible from accessible public spaces was recorded. Those observed in publicly inaccessible places (e.g. tunnels, railway corridors, inner private lands) was omitted to ensure safety and compliance with the law. This is not a methodological problem because the primary focus of the survey was political graffiti, which according to the literature (Alonso Citation1998), is found predominantly in publicly accessible and busy places to be seen by as many people as possible. For methodological reasons, the research omitted graffiti on objects that were brought from elsewhere or intended to be moved (e.g. means of transport, temporary fencing).

Spatial patterns of (political) graffiti in Holešovice district

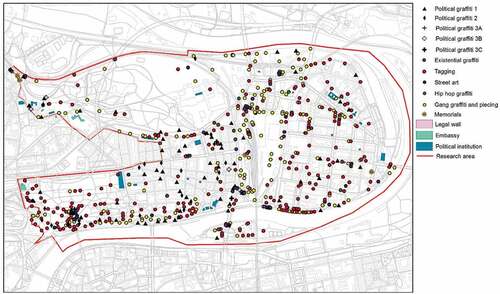

The findings of our spatial research on graffiti in Holešovice district are summarised in and shown the map in . The first and second most numerous categories are simple tags and more complex piecing (and gang graffiti), respectively, which share similar content, marking sites with the nickname of the writer or group of writers. The third most numerous category is political graffiti.

Table 1. Frequency of various types of graffiti in Holešovice (2019).

Figure 2. Localization of various types of graffiti and spatial context in Holešovice (2019).

It can be observed in that graffiti is spread across the entire research area, though there are further spatial patterns to be discussed. In accordance with broken window theory (Keizer, Lindenberg, and Steg Citation2008; Kelling and Wilson Citation1982), some places have a high concentration of more complex graffiti (gang graffiti and piecing), such as the unmaintained areas of Bubny and Holešovice railway stations. Such complex graffiti requires time to create, so the writers look for neglected localities which are not well guarded by the police or citizens. Similarly, we found a concentration of graffiti in some neglected streets. A good example is the former Holešovice brewery in the north-eastern part of the district. Currently a disused and neglected locality, its walls attract many graffiti writers (see ). As broken window theory states, the desecrated wall gives the impression that the site is not maintained and thus attracts further subversive activities.

Figure 3. Concentration of graffiti in the neglected locality of the former Holešovice brewery and at the subcultural centre at Letná Plain near the Metronome (2019)..Photos: Klára Baštářová Jan Šel.

Graffiti was also found to be concentrated along busy streets frequented by individual car transport or along tram lines (especially in the south by the Vltava embankment next to Štvanice Island; or at the previous example of the brewery’s walls, which run along a street with a tram line). These examples are well explained by spot theory, and we can safely say that the graffiti concentration at these sites is based on their popularity by the graffiti community due to their good visibility (Ferrell and Weide Citation2010). In addition, the locations are relatively neglected and, in some parts, degraded by heavy car traffic. Therefore, these concentrations correspond to both mentioned theories.

Rather simpler tags were found in the mostly gentrified area of the eastern part of the district near Holešovice Port. This can be attributed to the greater control of public space in the high-standard neighbourhood. According to Ferrell and Weide (Citation2010) and Haworth, Bruce, and Iveson (Citation2013), frequent removal of inscriptions leads to a concentration of simpler and faster forms of graffiti. Interestingly, we have not seen any protests against gentrification development (cf. Papen Citation2012); neither here, nor in the rest of Holešovice district despite its rising level of gentrification.

We can also see considerable difference between Letná and Stromovka Parks. Stromovka, as a classic recreational city park, is something like a blind spot on the graffiti map, which can be attributed to several factors. The park is used mostly by conformist middle-class citizens, who are probably not the source group of graffiti writers or their frequent admirers (see Bloch Citation2018; Fransberg Citation2019; Kindynis Citation2018). The park has also been extensively reconstructed, and such a well-maintained place may not be attractive to graffiti writers. Besides, there are few suitable areas for graffiti in the tree park itself. Finally, the eastern part of the park with the Exhibition Ground is under strong police control, and therefore does not provide the conditions for creating graffiti.

By contrast, Letná Park hosts an important subcultural centre with its famous DIY skatepark, in addition to its more broad recreational function which includes some cruise restaurants and sports grounds for a wide range of customers. The site’s context attracts writers of more complex graffiti on all the walls in the locality (). Therefore, the concentration of graffiti in this location can be seen as a specific kind of nonviolent territorial marking (Ley and Cybriwsky Citation1974; Walker and Schuurman Citation2015), which says to the community and other people something like: ‘This land is ours, we spend our free time here’. Although the northern part of the park and the plain is being reconstructed, most of this area is relatively neglected with many concrete surfaces. These ideal conditions indirectly support the concentration of graffiti, as stated in broken window theory. The pedestal of the former monument to Stalin, which now underlies the statue of Metronome, is also very visible from the city centre, mainly from the luxurious Pařížská Street (between numbers 2 and 6 in ), making it a very desirable location in terms of spot theory. The spatial pattern of graffiti localisation thus corresponds to the interesting fact that, according to all the theories discussed so far, Letná is an ideal place for creating graffiti. However, Letná Plain also has strong political symbolism (as mentioned earlier), which can also affect the placement of graffiti.

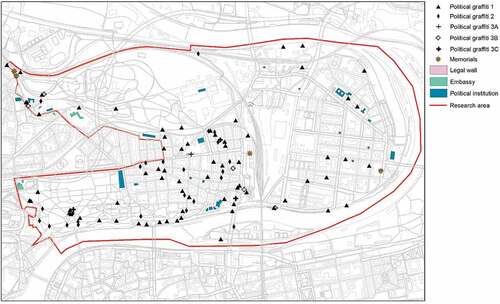

shows a less significant but clearly existing concentration of political graffiti in the western part of the research area. According to the presented theories, we can partially explain some of these spots of concentration. The most substantial one is at the locality of the Metronome. As mentioned above, this concentration may correspond to spot theory, territorial markers theory, and broken window theory for several reasons. As with other types of graffiti, we can also see a greater occurrence of political graffiti to the south of the research area (near Štvanice Island and between Štvanice Island and the Metronome), both of which can be explained by spot theory. However, none of the theories can explain the intense concentration of political graffiti at the single spot of the Metronome in the otherwise relatively homogenous area of Letná Park. Furthermore, it is clear that the overall spatial pattern of political graffiti in Holešovice district must be shaped by something not conceptualised in the three common theories.

Figure 4. Localization of political graffiti and spatial context in Holešovice (2019).

clearly shows that political graffiti is concentrated in the wider area of the politically important locality of Letná Plain, including the adjacent eastern buildings to the Bubny Railway Station. The significance of the political symbolic space of Letná Plain may be based on 1) its role as an historically important public space (through the 1920s to the present-day), 2) the presence of the buildings of national and European political institutions (including the planned but unrealized seat of the most important national political institution – the Parliament), and 3) the location of the statue of Metronome with its political connotations and the physical remains of the monument to Stalin connected to the negative historical memory of Czech society. Note that the unofficial name of the DIY skatepark is Stalin Square (see Surfergalaxy Citation2020). The diffusion of political graffiti to adjacent buildings to the east of Letná Plain is not surprising, because its eastern edges are the only localities to which political graffiti can easily spread from this politically important space. The plain is bordered to its west by another park, a villa residential area, and the forecourt of the Prague Castle, to its south by the Vltava River, and to its north by a railway barrier and another villa residential area with a lot of guarded embassies, all of which are not suitable places to create graffiti (Šel Citation2020).

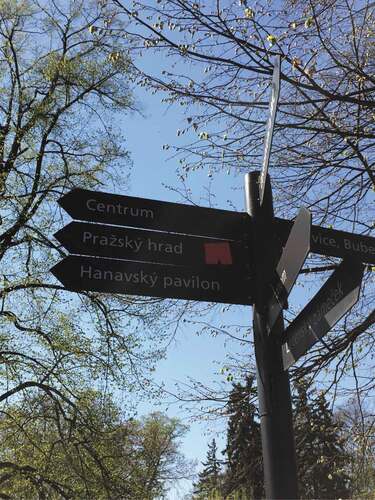

Political graffiti is hardly found close to the political buildings on the eastern edges of Letná Plain (see ). The same holds for other political buildings, embassies, and memorials in other parts of the research area. The obvious explanation for this is that these are well guarded localities with a dense coverage of camera systems. However this contradicts the findings of Megler, Banis, and Chang (Citation2014), who suggest that the concentration of graffiti can be correlated with buffers around political buildings. However, some writers are really creative and use signposts to the buildings for their political graffiti messages about the institution or person holding a particular post. For example, all around Letná Plain, signposts to Prague Castle, the seat of the Czech president, are decorated with ‘red shorts’ stickers as a symbol of political opposition to the populist nature of Czech president Miloš Zeman (signpost to ‘Pražský hrad’ in ; see BBC Citation2015). In this case the graffiti is created on something that represents the political system against which it itself protests (see Walker and Schuurman Citation2015). The form of creation is not exceptional in this case, because even in other localities it is observed that most political graffiti is made by the use of stickers in visible places on the main communication routes. This process of creation is faster and safer, and it also respects the need for visibility and readability of the message as opposed to some other types of graffiti, which are usually not readable for those outside the graffiti scene (Wacławek Citation2011). Therefore, the possibility that political graffiti is the work of the general public, which may not be the case with other graffiti types, is offered for discussion. The difference in the surface on which different types of graffiti are created is also relevant to this discussion, because political graffiti more often appears on public property (like lampposts, signposts, or public buildings) in contrast to other types of graffiti which are mainly found on private property. The question that then arises is whether the graffiti writers are people not otherwise involved in the political debate expressing their opinion (Iveson Citation2009), or general citizens attempting to emphasize commonly articulated political ideas. Either way, the manner of the expression can lead the recipients of the message to subconsciously push the writers to the margins in their imagination (see Baker Citation2015).

Among the more detailed types of political graffiti, expressions of general political attitude and ideology are the most represented (see ). Most often it is anarchist or antifa graffiti, but we can also see far right, nationalist, and anti-European messages, and protests against ethnic segregation or the meat industry. An interesting example of memorial graffiti, ‘Let Mišík sing’, was observed at the southern edge of Bubny Railway Station. The original graffiti from the communist period was a protest against the persecution of the famous Czech rock musician. The second most represented category are expressions of resistance (or support) to specific political and state institutions or persons in prominent political positions (see ). These include the above-mentioned ‘red shorts’ stickers, but also support or protest against the Czech far right parliamentary party SPD (Freedom and Direct Democracy). A few criticisms of the Czech governing party ANO 2011 and the police are also observed. Only a few examples of expressions of opposition to a specific political decision and process are found (see ). The division of this last category by its hierarchical level shows no clear spatial pattern due to the very small number of identified samples. We see several criticisms of controversial foreign politicians (e.g. Putin, Erdogan) and of foreign political policies or processes (e.g. the imprisonment of Catalan politicians), but we also see criticism of some national or local decisions.

Graffiti at the construction site of a new shopping centre and offices at a small undeveloped green place (near the street from Bubny Railway Station to the west) is shown in . This place has a tragic history, because during Nazi occupation in World War II it was used as a gathering place for Jews before they were deported. A wave of civic resistance arose against the proposed construction, with a demand that the site includes a memorial.Footnote2 The first photo, taken in 2018 before the field survey, shows the reactions of locals expressed in the form of political graffiti, who wrote ‘We want a park here!’ on the developer’s advertising poster near the construction site. This was visible from the busy main street passing through this location (which corresponds to the need to be seen, mentioned by Alonso Citation1998). However, the developer resolved the situation in an original way; the entire fence with posters became a legal wall and the newly created graffiti was laid over the original critical material preventing the creation of any new graffiti (an alternative fighting approach against graffiti, mentioned by Shobe and Conklin Citation2018). The second photo, taken during the field survey, shows the new ‘legal’ graffiti with the developer’s instructions at the top: ‘write, draw, spray, but stay decent … and please do not destroy me’. An additional satirical inscription that connects to the earlier political graffiti, and which could well have been made by the developer itself, reads: ‘We want a supermarket, parking, and graffiti here!’

The findings show that political symbolic space really has an influence on the spatial pattern of political graffiti. It is not so much the influence of political buildings and monuments however, but rather the presence of a politically important public space. More broadly, we can say that politically important public spaces influence the distribution of political graffiti in the district, but that political buildings and memorials may have some influence on the distribution of political graffiti within its area of concentration. In addition, we must not forget controversial constructions which are symbols of unpopular political decisions and therefore the target of some graffiti writers.

Conclusion

Our research on graffiti in Holešovice district led to several interesting findings and some future research questions. Despite the distribution of graffiti over almost the entire research area, we found a significant concentration in the historic and politically important location of Letná, at both a neglected public park overlooking the centre of Prague and a subcultural centre with a DIY skate park. This concentration can be somewhat explained by territorial markers theory, broken window theory and spot theory but in some aspects is perhaps better explained by the theory of political symbolic space.

The spatial patterns of political graffiti do not correspond to previous theories at a detailed level (concentration near the statue of Metronome) or at a higher level across Holešovice district (concentration in Letná). Both these concentrations may be explained by the places’ unrivalled importance as political symbolic spaces (of Holešovice district and of Prague as a whole). We may therefore say, that we demonstrate the importance of the integration of political symbolic space into graffiti research. According to our reflection on the spatial symbolism in the concentration of political graffiti, we can see the political dimension of urban space as a relative space based on its objects’ relationships, in which local people perceive a certain symbolism and probably project it into their ideas of importance in choosing sites for political activities. Therefore, this assumption should be reflected in any further research of urban political activities and at a more general level, in research on political, urban, and cultural geographies of the city.

Political graffiti was generally created through stickers in visible places on major communication routes. The reasons for this form of graffiti may include the need for readability of the message and speed of creation in such exposed places. Interestingly, stickers are more commonly used on public property, while other forms of graffiti are mostly found on private property. This may be a consequence of the philosophy of protest political graffiti: according to the literature, the creators often mark property that represents the political system against which they protest. But it is also possible that the creators of political graffiti are a different group of citizens with different values than those of other forms of graffiti. Additionally, we can also ask, along with the question of the creators of different types of graffiti, what position their opinions have in society: Are these opinions similar to common voices or expressions from the margins of political debates? And how does the general population react to them when it is presented in the form of graffiti? Graffiti is mostly perceived as something which comes from the margins of society, but the political views presented by them can be quite commonly held ones. This, however, will need to be verified by further research among graffiti writers and the general public.

A large concentration of graffiti was recorded in other neglected places, where a combination of the conditions given in broken window theory and spot theory were present. Graffiti writers have clearly chosen localities which are in a neglected state but are simultaneously well visible. In the high-standard gentrified locality of Holešovice Port to the east of the research area, there are rather simple tags, which corresponds to previously published findings that in well-guarded localities where rapid graffiti removal is likely, rather fast and artistically uninteresting types of graffiti appear. In this research, we did not record any protests (in the form of graffiti) against the gentrification development, although it is currently a burning issue across the whole of Prague in connection with ever-increasing flat prices. Therefore, it would be appropriate to focus more deeply on this relationship in future studies.

This paper aimed to contribute to the understanding of the subcultural phenomenon of graffiti, which as yet has not been fully grasped by social science. It is important in several ways, providing a good picture of what is hidden behind the solid structure of the city and of how our democracy works. A better understanding of the spatial patterns of graffiti could provide a useful input or feedback to the institutions of local government involved in public space planning. Moreover, it could also contribute to a better understanding of political symbolic space and its use in making democratic political expression more visible. In the case of radical undemocratic expressions, such an understanding can help to limit the possible misuse of political symbolic space. The topic of graffiti as a subcultural and political expression is therefore very significant not only for social science, but for society as well.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on comprehensive research, in which students from the Department of Social Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, Charles University participated. The authors would especially like to thank Klára Baštářová, Petr Janoš, Marek Neuman, Martin Schlichter, Jan Svoboda, and Alexandr Torgalo for their assistance with the field survey. Sincere thanks also belong to Lenka Hellebrandová for her assistance and discussions about graffiti research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The most famous graffiti site in Prague is probably the Lennon Wall (in Malá Strana district near Holešovice, see ). For many years it served as a famous tourist attraction, as a spot where tourists themselves could create graffiti. In November 2019, the massive creation of locally and historically unrooted and sometimes offensive graffiti led the Lennon Wall owners (Order of the Knights of Malta) to forbid the public from creating graffiti on the wall. It now contains street art, which refers to its dissident past during the communist regime (graffiti still appears to a lesser extent, but mainly from some tourists who do not know about the ban). The Lennon Wall is not included in this paper, because an analysis of such inscriptions would have to be based on longer observations and cannot be compared with the graffiti in the selected area of the city, where we assume the authors of graffiti are mainly locals.

2. It must be said that the Prague Jewish community did not oppose the construction, because there is already a memorial plate on another building at the site (see Židovské listy Citation2012). Moreover, Bubny Railway Station, which was the main departure point for the deportations, is located nearby with the new modern Shoah memorial in the former station building (see Figure 4). After the civic protests, the developer agreed with the local government to include a memorial (see update note in Židovské listy Citation2012).

References

- Abraháo, S. L. 2016. “Appropriation and Political Expression in Urban Public Spaces.” Revista Brasileira De Estudos Urbanos E Regionais 18 (2): 291–303. doi:10.22296/2317-1529.2016v18n2p291.

- Alexandrakis, O. 2016. “INDIRECT ACTIVISM: Graffiti and Political Possibility in Athens, Greece.” Cultural Anthropology 31 (2): 272–296. doi:10.14506/ca31.2.06.

- Alonso, A. (14 February 1998). “Urban Graffiti on the City Landscape [Paper Presentation].” Western Geography Graduate Conference, San Diego State University, CA, USA.

- Andersen, M. L., and A. Krogstad. 2019. “Euphoria and “Angst”. Grafitti Veterans’ Illegal Pleasures.” Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 60 (4): 348–370. doi:10.18261/.1504-291X-2019-04-02.

- Aneshensel, C. S., and C. A. Sucoff. 1996. “The Neighborhood Context of Adolescent Mental Health.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 37 (4): 293–310. doi:10.2307/2137258.

- Baker, A. M. 2015. “Constructing Citizenship at the Margins: The Case of Young Graffiti Writers in Melbourne.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (8): 997–1014. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1020936.

- BBC (21 September 2015). “Czech Protesters Replace Flag with Underpants.” BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34311078

- Bloch, S. 2018. “Place-Based Elicitation: Interviewing Graffiti Writers at the Scene of the Crime.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 47 (2): 171–198. doi:10.1177/0891241616639640.

- Blommaert, J. 2016. ““Meeting of Styles” and the Online Infrastructures of Graffiti.” Applied Linguistics Review 7 (2): 99–115. doi:10.1515/applirev-2016-0005.

- Brůhová, K. 2017. Praha nepostavená [Prague Unbuilt]. Praha: Czech Technical University.

- Christensen, M., and T. Thor. 2017. “The Reciprocal City: Performing solidarity—Mediating Space through Street Art and Graffiti.” International Communication Gazette 79 (6–7): 584–612. doi:10.1177/1748048517727183.

- Císař, O., J. Navrátil, and K. Vráblíková. 2011. “Staří, noví, radikální: Politický aktivismus v České republice očima teorie sociálních hnutí [Old, New, Radical: Political Activism in the Czech Republic through the Prism of Social Movement Theory].” Sociologický casopis/Czech Sociological Review 47 (1): 137–167.

- Cresswell, T. 1992. “The Crucial ‘Where’ of Graffiti: A Geographical Analysis of Reactions to Graffiti in New York.” Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 10 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1068/d100329.

- Daněk, P. 2013. Geografické myšlení: Úvod do teoretických přístupů [Geographic Thought: Introduction to Theoretical Approaches]. Brno: Masaryk University.

- Debras, C. 2019. “Political Graffiti in May 2018 at Nanterre University: A Linguistic Ethnographic Analysis.” Discourse & Society 30 (5): 441–464. doi:10.1177/0957926519855788.

- Doran, B. J., and B. G. Lees. 2005. “Investigating the Spatiotemporal Links between Disorder, Crime, and the Fear of Crime.” Professional Geographer 57 (1): 1–12.

- Ferrell, J., and R. D. Weide. 2010. “Spot Theory.” City 14 (1–2): 48–62. doi:10.1080/13604810903525157.

- Fransberg, M. 2019. “Performing Gendered Distinctions: Young Women Painting Illicit Street Art and Graffiti in Helsinki.” Journal of Youth Studies 22 (4): 489–504. doi:10.1080/13676261.2018.1514105.

- Gagliardi, C. 2020. “Palestine Is Not a Drawing Board: Defacing the Street Art on the Israeli Separation Wall.” Visual Anthropology 33 (5): 426–451. doi:10.1080/08949468.2020.1824975.

- Gartus, A., N. Klemer, and H. Leder. 2015. “The Effects of Visual Context and Individual Differences on Perception and Evaluation of Modern Art and Graffiti Art.” Acta Psychologica 156 (X): 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.actpsy.2015.01.005.

- Goalwin, G. 2013. “The Art of War: Instability, Insecurity, and Ideological Imagery in Northern Ireland Political Murals, 1979–1998.” International Journal of Politics Culture and Society 26 (3): 189–215. doi:10.1007/s10767-013-9142-y.

- Gomez, M. A. 1993. “The Writing on Our Walls: Finding Solutions through Distinguishing Graffiti Art from Graffiti Vandalism.” University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform 26 (3): 633–707.

- Halsey, M., and A. Young. 2002. “The Meanings of Graffiti and Municipal Administration.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 35 (2): 165–186. doi:10.1375/acri.35.2.165.

- Hanauer, D. 2011. “The Discursive Construction of the Separation Wall at Abu Dis: Graffiti as Political Discourse.” Journal of Language and Politics 10 (3): 301–321. doi:10.1075/jlp.10.3.01han.

- Harvey, D. 2006. “Space as a Keyword.” In David Harvey. A Critical Reader, edited by N. Castree and D. Gregory, 270–293. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Harvey, D. 2009. Social Justice and the City. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

- Haworth, B., E. Bruce, and K. Iveson. 2013. “Spatio-temporal Analysis of Graffiti Occurrence in an Inner-city Urban Environment.” Applied Geography 38 (X): 53–63. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.10.002.

- Hopkin, J., and C. Paolucci. 1999. “The Business Firm Party Model of Party Organisation. Cases from Spain and Italy.” European Journal of Political Research 35 (3): 307–339. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00451.

- Iveson, K. 2009. “War Is over (If You Want It): Rethinking the Graffiti Problem.” Australian Planner 46 (4): 24–34. doi:10.1080/07293682.2009.10753419.

- Iveson, K. 2013. “Cities within the City: Do-It-Yourself Urbanism and the Right to the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (3): 941–956. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12053.

- Kane, S. 2009. “Stencil Graffiti in Urban Waterscapes of Buenos Aires and Rosario, Argentina.” Crime, Media, Culture 5 (1): 9–28. doi:10.1177/1741659008102060.

- Keizer, K., S. Lindenberg, and L. Steg. 2008. “The Spreading of Disorder.” Science 322 (5908): 1681–1685. doi:10.1126/science.1161405.

- Kelling, G., and J. Wilson (1982, March). “Broken Windows. The Police and Neighborhood Safety.” Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/304465/

- Kindynis, T. 2018. “Bomb Alert: Graffiti Writing and Urban Space in London.” British Journal of Criminology 58 (3): 511–528. doi:10.1093/bjc/azx040.

- Kolláriková, N. (26 February 2019). “Malůvky, kam se podíváš [Pictures Anywhere You Look].” Praha 7. https://www.praha7.cz/maluvky-kam-se-podivas/

- Kopeček, L. 2018. ““I’m Paying, so I Decide”: Czech ANO as an Extreme Form of a Business-Firm Party.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 30 (4): 725–749. doi:10.1177/0888325416650254.

- Lagrange, R., K. Ferraro, and M. Supanic. 1992. “Perceived Risk and Fear of Crime: Role of Social and Physical Incivilities.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 29 (3): 311–334. doi:10.1177/0022427892029003004.

- Lee, S.-O., S.-J. Kim, and J. Wainwright. 2010. “Mad Cow Militancy: Neoliberal Hegemony and Social Resistance in South Korea.” Political Geography 29 (7): 359–369. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.07.005.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. 1996. Writings on Cities. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Ley, D., and R. Cybriwsky. 1974. “Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64 (4): 491–505. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1974.tb00998.x.

- Liu, J. H., and D. J. Hilton. 2005. “How the past Weighs on the Present: Social Representations of History and Their Role in Identity Politics.” British Journal of Social Psychology 44 (4): 537–556. doi:10.1348/014466605X27162.

- McAuliffe, C. 2012. “Graffiti Or Street Art? Negotiating The Moral Geographies Of The Creative City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 34 (2): 189–206. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00610.x.

- McAuliffe, C., and K. Iveson. 2011. “Art and Crime (And Other Things Besides): Conceptualising Graffiti in the City.” Geography Compass 5 (3): 128–143. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00414.x.

- Megler, V., D. Banis, and H. Chang. 2014. “Spatial Analysis of Graffiti in San Francisco.” Applied Geography 54 (X): 63–73. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.06.031.

- Naxera, V., and P. Krčál. 2020. ““Ostrovy deviace” v populistické rétorice Miloše Zemana [“The Isles of Deviation” in Populist Rhetoric of Miloš Zeman].” Sociologia 52 (1): 82–99. doi:10.31577/sociologia.2020.52.1.4.

- Overstreet, M. 2006. InGraffiti We Trust. Praha: Mladá Fronta.

- Paasi, A. 2003. “Region and Place: Regional Identity in Question.” Progress in Human Geography 27 (4): 475–485. doi:10.1191/0309132503ph439pr.

- Papen, U. 2012. “Commercial Discourses, Gentrification and Citizens’ Protest: The Linguistic Landscape of Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 16 (1): 56–80. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2011.00518.x.

- Parkinson, J. R. 2012. Democracy and Public Space. The Physical Sites of Democratic Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pehe, J. 2018. “Explaining Eastern Europe: Czech Democracy Under Pressure.” Journal of Democracy 29 (3): 65–77. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0045.

- Pixová, M. 2007. “Geography of Subcultures: Punks and Non-racist Skinheads in Prague.” Acta Universitatis Carolinae 42 (1–2): 109–125.

- Pixová, M. 2013. “Spaces of Alternative Culture in Prague in a Time of Political-economic Changes of the City.” Geografie 118 (3): 221–242. doi:10.37040/geografie2013118030221.

- Pugh, E. 2015. “Graffiti and the Critical Power of Urban Space: Gordon Matta-Clark’s Made in America and Keith Haring’s Berlin Wall Mural.” Space and Culture 18 (4): 421–435. doi:10.1177/1206331215616094.

- Radical East Side. 2018. “Legály Praha” [Legals Prague]. http://www.ustaf.cz/radical/?page_id=200

- Romotsky, J., and S. R. Romotsky. 1976. “L. A. Human Scale: Street Art of Los Angeles.” The Journal of Popular Culture X (3): 653–666. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1976.1003_653.x.

- Ross, J. I. 2016. “Introduction. Sorting It All Out.” In Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by J. I. Ross, 1–10, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ross, J. I., P. Bengtsen, J. F. Lennon, S. Phillips, and J. Z. Wilson. 2017. “In Search of Academic Legitimacy: The Current State of Scholarship on Graffiti and Street Art.” The Social Science Journal 54 (4): 411–419. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2017.08.004.

- Rupnik, J. 2018. Střední Evropa je jako pták s očima vzadu. O české minulosti a přítomnosti [Central Europe Is like a Bird with Eyes Behind. About the Czech Past and Present]. Praha: Novela bohemica.

- Šel, J. 2020. “Prostorová diferenciace graffiti v pražské čtvrti Bubeneč [Spatial Differentiation of Graffiti in the Bubeneč District of Prague]” [Bachelor’s thesis]. Faculty of Science, Charles University.

- Serafis, D., E. D. Kitis, and A. Archakis. 2018. “Graffiti Slogans and the Construction of Collective Identity: Evidence from the Anti-austerity Protests in Greece.” Text & Talk 38 (6): 775–797. doi:10.1515/text-2018-0023.

- Shobe, H., and T. Conklin. 2018. “Geographies of Graffiti Abatement: Zero Tolerance in Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle.” The Professional Geographer 70 (4): 624–632. doi:10.1080/00330124.2018.1443476.

- Snyder, G. J. 2009. Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Surfergalaxy. 2020. “Stalin Square. Prague, Czech Republic. Skateboarding.” http://surfergalaxy.com/en/spot/czech-republic/stalinsquare

- Swyngedouw, E., and N. C. Heynen. 2003. “Urban Political Ecology, Justice and the Politics of Scale.” Antipode 35 (5): 898–918. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2003.00364.x.

- Taha, D. A. 2016. “Political Role of Urban Space Reflections on the Current and Future Scene in Cairo-Egypt.” Architecture Research 6 (2): 38–44.

- Taylor, M., and I. Marais. 2011. “Not in My Back Schoolyard: Schools and Skate-park Builds in Western Australia.” Australian Planner 48 (2): 84–95. doi:10.1080/07293682.2011.561825.

- Ten Eyck, T. A. 2016. “Justifying Graffiti: (Re)defining Societal Codes through Orders of Worth.” The Social Science Journal 53 (2): 218–225. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2014.11.007.

- Vanderveen, G., and G. Van Eijk. 2016. “Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder.” European Journal On Criminal Policy And Research 22 (1): 107–125. doi:10.1007/s10610-015-9288-4.

- Wacławek, A. 2011. Graffiti and Street Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Waldner, L. K., and B. A. Dobratz. 2013. “Graffiti as a Form of Contentious Political Participation.” Sociology Compass 7 (5): 377–389. doi:10.1111/soc4.12036.

- Walker, B. B., and N. Schuurman. 2015. “The Pen or the Sword: A Situated Spatial Analysis of Graffiti and Violent Injury in Vancouver, British Columbia.” The Professional Geographer 67 (4): 608–619. doi:10.1080/00330124.2014.970843.

- Zaimakis, Y. 2015. “‘Welcome to the Civilization of Fear’: On Political Graffiti Heterotopias in Greece in Times of Crisis.” Visual Communication 14 (4): 373–396. doi:10.1177/1470357215593845.

- Židovské listy (27 February 2012). “Bude v Holešovicích nový památník obětem holokaustu? [Will There Be a New Memorial to the Victims of the Holocaust in Holešovice?].” Židovské listy. http://zidovskelisty.blog.cz/1202/bude-v-holesovicich-novy-pamatnik-obetem-holokaustu