ABSTRACT

The publicness of publicly owned public spaces is an important concept that needs further examination, especially in countres like China where most urban public spaces are publicly owned and managed. This case study of Chongqing People’s Square reveals that the transformation of municipal squares’ publicness in reform-era China is closely linked with the country’s shifting political and sociocultural contexts. We argue that despite traditionally valued public ownership and planning-design qualities, the crucial role of governance management in shaping the publicness of publicly owned and managed public space is not yet fully understood.

Introduction

With the growth of Neoliberalism, academics have become increasingly interested in the publicness of urban public space (PUPS). Research on PUPS has offered an effective approach to investigate public spaces through the lens of planning and design, governance and management, and user and use (Akkar Citation2003; Németh Citation2009; Loukaitou-Sideris and Banerjee Citation1998; Varna and Tiesdell, Citation2010; Langstraat and Van Melik Citation2013; Ekdi and Çıracı Citation2015; Mantey Citation2017; De Magalhães and Freire Trigo Citation2017; Lopes, Cruz, and Pinho Citation2020). As China has pursued socialist market economy reform, the need for commercial and leisure spaces has grown, and urban development has been increasingly accompanied by profound changes in PUPS.

In Western contexts, research on PUPS has mainly focused on privately owned public spaces (hereafter referred to as POPSs) and explored how private ownership influences the management strategies and use of public spaces (Kohn Citation2004; Carmona Citation2010; Mantey Citation2017). In China, the official commodification of the use right of state-owned urban land that took place in 1990 brought the rapid development of pseudo-public spaces in urban areas. Several researchers have investigated the role of PUPS in the reform era. For example, Yang (Citation2009) has explored how strong consumption and developmental objectives have influenced the publicness of central pedestrian districts in five Chinese metropolises and suggested that consumerist culture has both negative and positive impacts on urban life. Similarly, Chen (Citation2010) has argued that institutional paradoxes in spatial production mechanisms have led to a ‘loss of publicness’ in Chinese urban public spaces. Wang and Chen (Citation2018) have also analysed the publicness of pseudo-public spaces and concluded that although they are generally less public than traditional public spaces in China, the rise of these areas did not necessarily lead to the ‘end of public space’.

Existing research mainly focuses on commercial space, however, and is preoccupied with the same questions posed by Western scholars; namely, how privatisation of the use right of urban land influences public spaces in the process of marketisation and globalisation. In the context of China, it is important to consider that many institutions created during the planned economy era still play a part in the production and management of urban public spaces and undergo constant reforms to increase their degree of marketisation. Therefore, this research argues that while the growth of POPSs is a significant phenomenon in reform-era China, publicly owned public spaces have also changed in profound ways. Because of the unique land-use system in China and the fact that most large-scale public spaces are owned and managed by public authorities, examining publicly owned public spaces can help shed light on the particularities of Chinese publicness. Notably, the municipal square is a type of publicly owned public space that experienced a boom in the 1990s along with the growing academic interest in ‘publicness’. Comparing these new municipal squares with the mass-rally squares that were a fixture of the earlier socialist period thus allows us to better understand PUPS in reform-era China and shed light on the role of publicness more generally.

Through a field study and semi-structured interviews, this article analyses how political-economic reforms have influenced municipal squares that were constructed during the ‘square boom’ that began in the 1990s. Specifically, it investigates the development of Chongqing People’s Square (CPS) from 1997 to 2019. Through the theoretical lens of PUPS, this article not only examines a physical environment but also analyses the management and use of public space to study how CPS has been shaped in the reform era. Additionally, this research aims to articulate the relationships between political-economic reforms and the publicness of publicly owned and managed public spaces in Chinese cities. In so doing, it contributes to ongoing critical conversations centred on PUPS.

Publicness of urban public space

Previous research has highlighted that multiple qualities, such as openness (or inclusiveness), heterogeneity, commonness, freedom, and equality, are essential for publicness (Arendt Citation1998; Habermas Citation1991; Sennett Citation1977). PUPS encompasses a wide variety of concepts and intellectual inquires, and despite the inherent ambiguity of this term, several distinctive strands in PUPS scholarship can be identified. Researchers have focused on management by analysing the agencies, interest groups, and ownership involved in the construction of public space (Akkar Citation2003; Kohn Citation2004). Over the past several decades, a growing thread of literature has also scrutinised the impacts of top-down control, physical environment, and practices of public life (Varna and Tiesdell Citation2010; Langstraat and Van Melik Citation2013; Mantey Citation2017; Wang and Chen Citation2018; Lopes, Cruz, and Pinho Citation2020). Drawing on this vast wealth of literature, the following review highlights some of the most relevant concepts connected to the present investigation. In general, this research foregrounds a PUPS study framework that is defined by three major correlated dimensions: planning and design, governance and management, and user and use.

The planning-design dimension is a perspective that architects and planners primarily consider. It centres on the influence that physical environment has on public activities with a specific focus on three sub-dimensions: physical accessibility, pragmatic function, and designed form. Physical accessibility is understood as a paramount aspect of PUPS in the sense that ideally, a public space should be easily accessible to most members of the social public with minimal physical barriers (Akkar Citation2003; Kohn Citation2004; Langstraat and Van Melik Citation2013; Mantey Citation2017; Lopes, Cruz, and Pinho Citation2020). In addition to this emphasis on physical accessibility, recent studies have taken visual connection to be a constitutive element (Ekdi and Çıracı Citation2015; Wang and Chen Citation2018). Pragmatic function is a sub-dimension oriented around existing patterns and possible ways of utilising space enabled by physical conditions. The function category helps assess the performance of programmed space types, deployed facilities, and amenities in terms of their capacity to serve planned activities and encourage spontaneous events (Varna and Tiesdell Citation2010; Wang and Chen Citation2018). The built form sub-dimension frames the design qualities embedded in processes that continually shape public space, such as the aesthetic, tectonic, compositional, and sensory details embodied in architecture and different types of built constructions. However, recent studies cast doubt on the causal link between qualities of formal innovation and publicness, and the latter is more often linked to inclusiveness and user engagement than aesthetic paradigms (Lee Citation2020).

By focusing on factors such as responsibility, financial structure, and control measures, the governance management dimension explores inherent relationships between permitted uses, users, and behaviours in certain public spaces (Németh and Schmidt Citation2011). Within the scope of governance management investigation, ownership is a common concern. Several scholars have argued that a growing proportion of private ownership has led to the decline of PUPS. Their claim is based on the belief that public ownership plays a crucial role in ensuring the democratic characteristics of public space (Madanipour Citation2003; Akkar Citation2003; Kohn Citation2004). On the other hand, more recent research tends to argue that diversified forms of ownership and management may not necessarily impair PUPS (Carmona Citation2010; De Magalhães and Freire Trigo Citation2017; Mantey Citation2017) and emphasise that it cannot be claimed that publicly owned and managed public spaces are more inclusive or ‘public’ than privately owned public spaces (Ercan and Memlük Citation2015). As Langegger (Citation2017) has suggested, the key to understanding PUPS is legitimacy. By broadening the discussion from ownership to responsibility, researchers have identified and analysed multiple forms of institutional or organisational agencies that are responsible for maintaining and controlling public space (Akkar Citation2003; Wang and Chen Citation2018). As a means of examining whether public spaces serve public interest, the sub-dimension of financial structure analyses the sources and distributions of funding as well as their impacts on negative or desired transitions of public space (Akkar Citation2003; Wang and Chen Citation2018). In addition to responsibility and financial structure, the final sub-dimension of control investigates deployed control measures to critically review and evaluate the balance between security concern, public order, and individual freedom in public space (Németh and Schmidt Citation2011; Langstraat and Van Melik Citation2013; Ekdi and Çıracı Citation2015; Mantey Citation2017).

The user-use dimension deals with daily life practices that take place in public spaces. Arguably, the user-use dimension provides the most relevant and indicative data while revealing the real status of PUPS by focusing on the demographic diversity of users and their various activities (Németh and Schmidt Citation2011; Langstraat and Van Melik Citation2013; Ekdi and Çıracı Citation2015; Varna and Tiesdell Citation2010). One controversial topic that emerged in this line of study centres on whether all behaviours that take place in public space should be categorised as ‘public activities’. Kohn (Citation2004) highlights the importance of inter-subjectivity in constituting public space and suggests that direct interaction and meaningful communication between people are the primary gauges that should be used to measure the authentic qualities of public life. Alternatively, other scholars assert that people use public space for both collective and individual purposes (Carr et al. Citation1992) and reaffirm the value of seemingly passive but constructive forms of human interaction, such as watching and listening to others without intense participation (Gehl and Svarre Citation2013). This disagreement underscores the problem of viewing the public as a pre-fixed domain and demands methodological sensitivities in analytical procedures. Both collective and seemingly individual activities should be carefully assessed to avoid epistemological exclusiveness.

Informed by existing scholarship, this research adopted and adapted three main dimensions and eight sub-dimensions to formulate a general analytical framework (). The theoretical disputes involved in the referenced framework will be revisited and addressed in the relevant parts of the presented analysis.

Table 1. Analytical framework for PUPS.

Municipal squares in reform-era China

In the context of this research, it is essential to consider China’s unprecedented urbanisation movement and the political-economic reforms of the Post-Mao era. Compared to the drastic ‘shock therapy’ adopted in former communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, China’s political-economic reforms have been carried out in a steady and incremental manner. Encouraged by the developmental successes achieved through humbler experimental reforms that were implemented in so-called ‘special economic zones’, such as Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Xiamen, after 1978, the officials of the Communist Party of China (CPC) introduced the term ‘socialist market economy’ in its 14th National Congress in 1992. This move announced the CPC’s objective to establish a national economic system defined by the dominance of public ownership and the supplementary roles of other forms of ownership. The 1992 congress marked the beginning of China’s economic transformation, which has since continued to shift from a planned-economy system to a market-economy system. During the unprecedented urbanisation movement that has accompanied this transition, the image of the city and urban life have undergone fundamental changes.

This research highlights three aspects of Chinese economic reform that sparked major structural and programmatic changes and had fundamental impacts on urban life. First, commodification of urban land caused issues related to private land-use rights and also inevitably introduced new developmental models and interests parties of urban public spaces. Second, the devolution of political-economic power has enabled and required a more open and flexible management system that allows for diversified types of participants in the managing process. Third, the ideological changes that have accompanied Chinese reforms have promoted, consciously or unconsciously, the growth of leisure and mass cultures, which, in turn, became a crucial factor in shaping urban landscapes and redefining the nature of public space.

From mass-rally squares to municipal squares

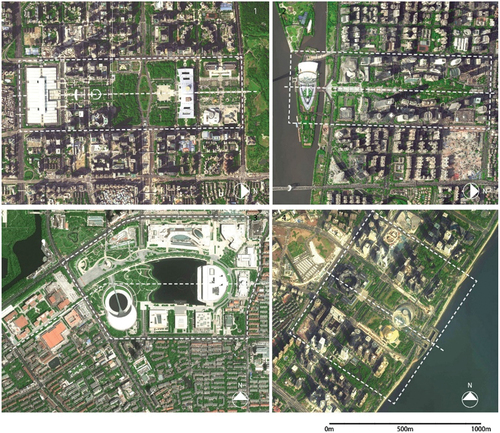

The Western civic square, which was introduced to northern Chinese cities (e.g. Qingdao, Lüshun, Dalian and Ha’erbin) during the turn of the twentieth century by European colonialists, failed to make an immediate significant impact (Cao Citation2005). In the Republic of China, squares were usually roundabouts of main roads. During the 1950s and 1960s, many squares were constructed for mass rallies, most of which were temporary, had very little green space, and were merely part of the main roads (Gaubatz Citation2008). Along with the rapid economic development and urbanisation of the 1990s, square construction became a nationwide phenomenon (Peng Citation2011), and thousands of squares were built during this period (, ). For instance, Dalia, the first city to set this trend, had already built fifty new city squares by 2000.Footnote1 Most municipal squares were reconstructed from former mass-rally squares in central urban areas and thus inherited the historical meanings of these places. Many of their names also carry political significance. For instance, People’s Square emphasises the people’s interests, May 1st Square pays respect to the working class, and August 1st Square commemorates the founding of the People’s Liberation Army. This kind of nomenclature was especially apparent before the 1980s, and these names have been popularly adopted across the country.

Figure 1. Municipal squares built after 2001. (1. Civic Square in Shenzhen; 2. Huacheng Square in Guangzhou; 3. Yinhe Square in Tianjin; 4. Civic Square in Hangzhou).

Table 2. Municipal squares reconstructed from mass-rally squares in provincial capitals and municipalities of China.

According to City Square Design published in 1999, municipal squares were usually located near municipal government office buildings in the city’s administrative centres and provided government officials and citizens with spaces to communicate and hold public gatherings. Municipal squares were also kept a distance away from commercial districts to avoid commercial advertisement, crowds, and noises as a means of maintaining a formal atmosphere (Wang, Xia, and Yang Citation2000). A fixed type of Beaux Art-inspired spatial configuration emerged during the late 1990s and became popularly adopted nationwide. Most municipal squares were organised in symmetrical forms with axes and decorative statues, flag-raising platforms, and large lawns (Liu Citation2008). As an environmental imperative became firmly rooted in the consciousness of Chinese urban planning, mass-rally squares were refashioned through policy and practice as important elements of green urbanism (Gaubatz Citation2019), and particular importance was placed on greening rates. For example, the reconstruction plan of Shanghai People’s Square in 1993 attempted to increase its greening rate from 20% to 70%.Footnote2

Since China joined the WTO in 2001, city brand marketing campaigns have intensified. The goal of building the ‘international city’ or ‘world city’ has driven a considerable number of Chinese metropolises to develop central business districts and new green spaces (Gaubatz Citation2019). Municipal squares constructed after 2000 were usually viewed as important components of large-scale developments of new urban core areas, where different commercial and cultural facilities, such as museums, theatres, concert halls, libraries, and exhibition halls, were located. Meanwhile, spatial axes and green space continued to be important design elements. Many municipal squares used spatial axes as a configurative device to control the future buildings and landscape design. This approach improved the greening rate and minimised areas of hard pavement. Consequently, new urban squares are more like parks and thus differ from the squares found in European countries ().

New financial system and management of municipal squares

In the early reform era, political restructuring focused on the devolution of political-economic power from central to local government, government to state-owned enterprises, and from the state to society (Yu Citation2008). Specifically, these reforms brought significant changes to the financial system of public institutions that were created during the planned-economy era. According to the official definition provided by the Interim Regulation on the Registration of Public Institutions, public institutions (hereafter referred to as PIs) refer to public service organisations that are established by the state and other organisations using state-owned assets as a means of promoting activities related to education, science and technology, culture, and hygiene. PIs in China are similar to non-profit organisations in the Western world. The main difference is that Chinese PIs are usually established, fully financed, and managed by the government (Wei Citation2019). When China began to introduce the Western theory of public finance in the 1980s, PIs started to face reforms under the policy of ‘devolution of political-economic power.’ Consequently, the financial system of PIs was restructured and diversified. The system of ‘Self-Controlled Finance and Expenditure’ (hereafter referred to as SCFE) was officially applied to certain types of PIs in 1985, including many management divisions of public facilities, such as municipal squares, auditoriums, theatres, and museums (Duan Citation2009). The new system requires PIs to cover their expenditures with their income, which also means that they are allowed to keep any surplus; however, PIs also have to deal with deficits. In order to increase their income, many SCFE institutions expanded their business scope and established different kinds of subsidiaries. Meanwhile, SCFE institutions still maintain several characteristics of traditional PIs. Most importantly, they remain establishments governed by local governments. As Zhu (Citation2000) has pointed out, the central government wants to use reform to legitimise rather than undermine the existing political structure; therefore, one key characteristic of this transformation is that many institutions inherited from the planned economy system are still in place and continue to drive current market economy reform that strives to unleash individual and local initiatives in order to increase productivity. In summary, SCFE institutions in the reform era possessed a mixture of planned and market economy characteristics. Financially, they were run like enterprises, but they were structured like traditional PIs and continued to adhere to the political ideology of central and local governments.

Promotion of square culture

Market economy reform reintroduced leisure culture to the city’s daily life, a culture that is largely depoliticised (Xing Citation2011). In May of 1995, a forty-hour workweek system was officially implemented nationwide and created ‘double leisure days’ (i.e. the weekend). After this policy was implemented, weekend activities became a popular topic (Wang Citation2001). For instance, the Beijing government launched the campaign ‘To be the modern and civilised Beijingese – the Double Leisure Days Plan’ in 1996, which encouraged people to visit museums, read books, attend art performances and cinema, participate in sports, go on sightseeing tours of the city, and learn English.Footnote3 A more vibrant leisure culture was thus fostered and popularised. In this atmosphere, city squares provided an appropriate stage for the government to promote weekend cultural events, such as art performances, concerts, dancing parties, and chess competitions.Footnote4–Footnote5

Along with city square development and the growth of leisure culture, ‘square culture’ thrived in the second half of the 1990s. Starting in 1989, Shenzhen was among the earliest cities to hold diverse events that ranged from art performances, concerts, and exhibitions to live painting and movie showings.Footnote6 Shanghai had its first outdoor symphony concert during Huangpu Tourism Festival in 1993, and the district government started two series of square events in the same year (the ‘Bund Concert’ in Chenyi Square and the ‘New Century Square Concert’ in Bund Park). By 2000, the Huangpu district government had hosted more than 500 art events in total.Footnote7 It is important to note that for cities with a sufficient number of city squares, entertainment activities took place in recreational squares rather than municipal squares. This situation aligns with the definition of municipal squares provided by the aforementioned book.

Methodology

As suggested above, specific cultural, economic, and political contexts can influence how people view PUPS. Building on this assumption, our study uses the Chongqing People’s Square (henceforth CPS) as an example to explore the transformation of the publicness of municipal squares in reform-era China. The rationale of our case selection is threefold. First, unlike other major Chinese cities, such as Shanghai, Tianjin, and Guangzhou, there was no square built by Western planners or designers in Chongqing, despite the fact that the city became an open treaty city in 1891. In other words, the experience of CPS is domestic and regional and thus serves as an example of the type of PUPS that grows from Chinese local sociocultural conditions. Second, the formal and programmatic characteristics of CPS’s building style, space scale, and modes of utilities are representative of the majority of Chinese municipal squares Third, CPS was designed and constructed during China’s reform era. The contemporariness of CPS makes it a valuable case to focus on while exploring the link between situated publicness and China’s political-economic reforms.

Literature review

In order to better understand the specific developmental history of CPS, this study reviewed a wide range of primary materials, including books, theses, journal articles, official documents, newspaper pieces, photographs, and technical drawings. We especially relied on two journal articles and one local record of CPS’s design that were produced in the 1990s, 20 local newspaper articles published in June of 1997 that reported on the construction and management of CPS, one book on the history of the CPS area, and two official planning documents.

Field study

The field study was conducted through site observation and random interviews that took place in 2019. It focused on how CPS is used and perceived by its users, and how the area is controlled and managed by the authorities. We conducted our field studies twice in good weather conditions that were suitable for outdoor activities. The first took place on May 25th (Saturday) and May 28th (Tuesday), and the second occurred on November 11th (Monday) and November 16th (Saturday). During our observations, we took note of the physical environment as well as the different activities that were held on the site from 7 am to 7 pm. The random interviews consisted of short and informal conversations with local users who we encountered in the square and were designed to help us get a sense of their general perceptions of CPS. Twenty-seven random interviews were conducted, the duration of which varied from 10 to 30 minutes. Given the nature of these conversations, the interviews presented in the following analysis are based on the researcher’s on-site notes.

Semi-structured interviews

The last stage of the research involved conducting face-to-face semi-structured interviews in Chongqing in November of 2019. The objective of the interviews was to better understand the design and management process of CPS and get a sense of how different people perceived the publicness of CPS. The interviewees included one local government official who oversaw the construction and management of the square, one architect who directly participated in the design of CPS and its surrounding areas, one planner who was familiar with the development of the CPS area, one former officer involved in managing the CPS area, and one specialist of Chongqing’s history (). The interviewees were asked about the vision, goals, implementation process, and results of development projects in the CPS area. All of the interviews were recorded and inductively coded by the author, and all of the materials have gone through member checking.

Table 3. Semi-structured interviews.

The publicness of Chongqing People’s Square, 1997-2019

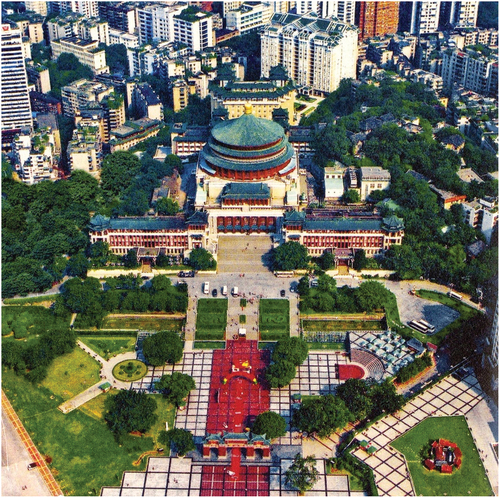

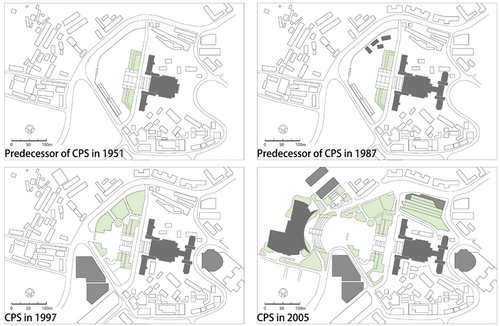

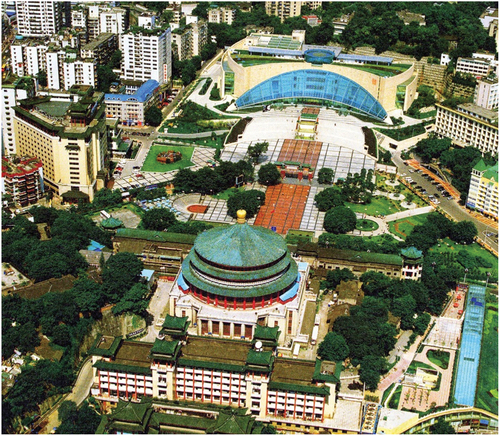

The history of CPS can be traced back to the early 1950s when it was originally built as a walled open space of Chongqing People’s Auditorium (CPA). The auditorium served as Chongqing’s political centre, and the building spaces included an auditorium, an international hostel, and government offices.Footnote8 Before the 1990s, the space was walled, guarded, and had little landscaping. The space division prohibited public access without official permission. The first-round reconstruction was carried out in 1997, which involved demolishing the wall and opening the CPS to the public. The second-round innovation was executed in 2005 and included extending the space of the square and adding a historical museum and commercial facility to the original compound. Generally, CPS has always been publicly owned and managed. However, the property itself has undergone a significant transformation both during the ‘square boom’ of the 1990s and the renovations that took place after 2001 aimed at improving the functional performance of the building.

Planning and design

Opening the square, 1997

By the beginning of the 1990s, the original auditorium and the walled open space had suffered serious physical deterioration, but the land value of the CPS area enjoyed a sharp rise due to the marketisation of urban land. In 1993, a local developer approached the former chief architect of CADI and commissioned him to make a proposal for reconstructing a part of the walled space and turning it into a commercial district:

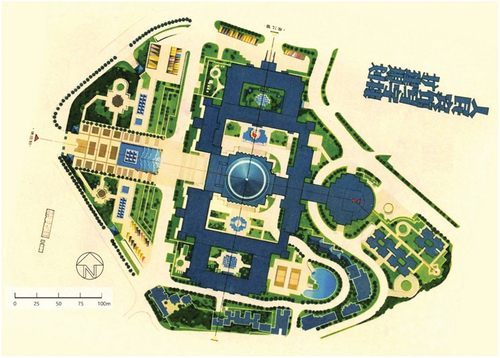

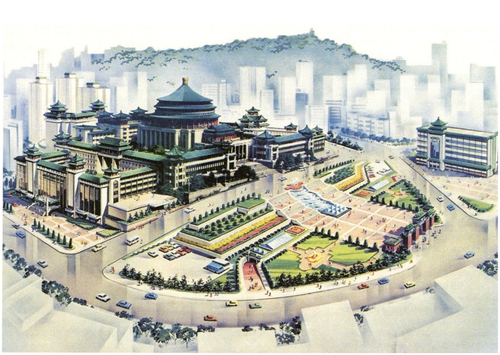

I had considered reconstructing the walled space into a city square for years. The commercial redevelopment was obviously against it; therefore, I persuaded the developer to conduct the commercial project in surrounding areas and reconstruct the space into a city square for public activities like ceremony, gathering, exhibition, recreation, and entertainment. Besides, the plan also included residential buildings and the extension of the auditorium (). Although the local government complimented the proposal, extending the historical auditorium gave rise to a heated academic debate because some experts believed it would impair the authenticity of the historical building. A panel of renowned professors in architecture was established to discuss the issue but failed to reach a consensus …; hence, officials decided to take a discreet attitude and temporarily aborted the extension project.

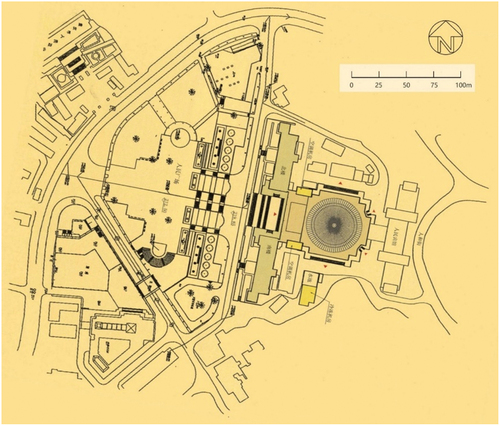

Figure 2. The master plan of the extension of the People’s Hotel, July 1993.

Figure 3. Perspectives on the extension of the People’s Hotel, July 1993.

(Interview with the former chief architect of CADI)

Coinciding with the nationwide ‘square boom’, the opportunity to revitalise the square finally came in 1997 when Chongqing was designated as the fourth municipality in China. The government viewed the reconstruction of the walled space into a city square as an endeavour that could help polish its image, and it was named the first project of the Key Projects in the Public Interest.

To demolish the wall is to dismantle the barrier between the enclosed building and the general public and suggests the people-oriented principles of the government … CPS cannot be separated from CPA. They heavily relied on each other, and together they have developed into an important spot for public gathering, civic activities, and tourism.

(Interview with the former deputy secretary-general of Chongqing municipal government)

The project launched on March 20th and was completed within two months. The new city square was 1.74 ha in total. The hard pavement covered an area of 0.7 ha, the greening zone was approximately 0.87 ha, and the pond covered 0.17 ha (). The reconstruction made no major changes to the original configuration of the square and used axes to organise space. The renovation strengthened the symmetrical layout by paving the central axis with red granite and arranging the flag-raising platform and paifang, a traditional Chinese architectural feature, on the axis. The project also improved the area’s pavement, vegetation, and amenities by adding street lamps, trash cans, benches, flower beds, and fountains and retaining the local Ficus virens trees. (; ) (Liang Citation1999).

Table 4. Design points for CPS.

Further development, 2005-2019

Following the national trend that emerged after 2001 to build cultural facilities around municipal squares after 2001, a historical museum was built on the axis of CPA in 2005. To integrate the museum and the auditorium the design of the museum was guided by the existing axis, and a road was constructed underground to pedestrianise the whole area. These strategies extended the area of CPS to 4.2 ha (). Instead of repeating the vernacular building style of the auditorium, the museum’s simplicity, utility, and technological efficiency presented a modern form and style that contrasted against the old CPA and resonated with the new ideology of the 21st century (Zheng Citation2008). The construction of the museum brought new function to CPS and was an early effort to revitalise the cultural and historical significance of this area. In 2019, the Chongqing government approved a regeneration project that aims to connect three historical public facilities built in the 1950s (including CPA) with an envisioned 1,100-metre-long public pedestrian zone. The city also intends to renovate the area adjacent to CPA and make it into a historical district. By connecting previously separated historical elements with a public pedestrian zone, the reconstruction projects aimed to situate the historical significance of CPS into wider cultural and historical contexts and recreate the cultural centre in the Yuzhong District.

Figure 6. The relationship between the auditorium, the square and the museum.

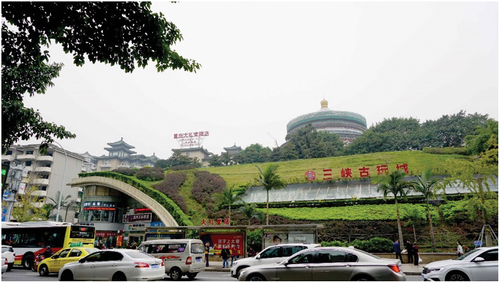

In addition to the construction of the museum, a commercial development project focused on an area adjacent to CPA called the Three Gorges Antique City was underway. The commercial project was very controversial because some believed that it might compromise the historical value of CPA. Shortly after the chief architect’s proposal was aborted, a real estate developer from Hong Kong obtained the use right of the land next to CPA. Because the extension project had already sparked public critique, the proposed development scheme maintained a low profile, and the government’s principal requirement for the project was that it should minimise its possible impact on the visibility of the auditorium. The height of the buildings was thus cautiously restrained.

Actually, the developer invited me to design the building but I rejected it, … The initial design adopted an earth-sheltered structure with a planted roof, making the northern façade of the auditorium visible from People’s Road (). Nevertheless, the final construction did not precisely follow the initial design instruction, and its northern façade appeared along the road in order to create a more visible commercial façade. Critiques soon arose after its completion. However, it is understandable that being seen from the street was so crucial for commercial activities ().

Figure 7. View of the earth sheltering proposal.

Figure 8. Three Gorges Antique City from People’s Road.

(Interview with the former chief architect of CADI)

Moreover, the commercial project was separated from CPS by a road and was not visible from the square. These design and planning operations indicate that the authorities aimed to maintain a separation between the commercial zone and the municipal square.

Governance and management

SCFE management

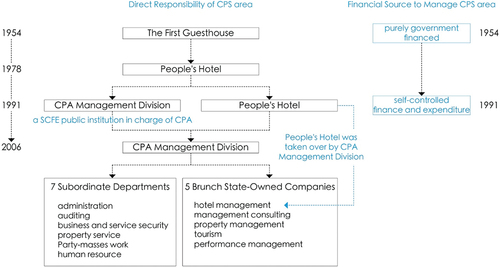

The CPS area has always been managed and maintained by public authorities. Before 1987, the auditorium, hostel, and walled open space were all managed by a state-owned work unit called the First Hostel. In 1987, the First Hostel was restructured and transformed into a state-owned enterprise and renamed the People’s Hotel. The People’s Hotel continued to manage the whole area until the local government realised the historical value of CPA in 1991 and established the CPA Management Division (henceforth CPAMD) to take charge of the security and daily maintenance of the auditorium as well as the walled open space. After the walled open space was reconstructed into CPS, the CPAMD continued to manage this area. In addition to the public funding that it received from the municipal government and Cultural Relics Bureau to support major conservation projects as a PI with SCFE management, the CPAMD oversaw multiple incoming generating activities, such as selling tickets for auditorium visits and leasing out the auditorium for commercial performances and parts of the square to privately-run tea houses businesses. These commercial activities helped create enough income to cover basic expenditures and daily maintenance. In 2006, the CPAMD took over the administration of the People’s Hotel and was restructured into a larger PI with seven branch departments and five state-owned subsidiaries ():

The unified management of the square area largely improved the efficiency of our work. It also ensured the funding and the long-term conservation plan of CPA. The restructure helped to realise self-sufficiency and improve the service and maintenance of the square.

(Interview with the former deputy director of CPAMD)

Notably, leasing out parts of the municipal square to privately-run tea houses can be controversial in terms of publicness because it transfers the use-right of the public space to the private. Two small tea houses in CPS divided the square into two zones: the free zone with benches and the charged zone with chairs, tables, and shelters. According to our on-site observations, few people frequented the tea houses. The contrast between the poorly visited tea houses and the popular sitting space near the raised flower beds was notable () and highlighted that these tea houses did not effectively serve the public’s interest:

It is quite inappropriate to have the mediocre tea house in such an important position (the place next to the paifang) of the municipal square. It not only damages the image of the square but also encroaches on the place which should be open to the public freely.

(Random interview with one user in CPS)

Public discussion on public behaviours

In addition to top-down measures, citizens also actively took part in maintaining the square. About two weeks after the square opened, a special column – People’s Square loved by the People – appeared in the official local newspaper in response to the requests of its readers. The column offered a platform for the public to debate how people should behave in the square and other public spaces.Footnote9 In general, the most frequently discussed disgraceful behaviours were littering and stepping on the lawn.Footnote10–Footnote11 Citizens appealed to social ethics in their letters to the column.Footnote12–Footnote13 Primary schools, colleges, and work units organised volunteers to pick up garbage on the square, and other participants of this social movement offered specific advice.Footnote14–21 A deputy of Chongqing Municipal People’s Congress pointed out that the number of squares indicates the degree of civilisation of a city. It follows that an insufficient number of squares and overloaded use signals the deficiency of urban infrastructure and urban planning. Furthermore, the deputy suggested that the government should create more city squares in a way that strengthens their cultural meaning through the adoption of more appropriate designs.Footnote22

Regulations and control measures

The day before the opening of CPS, the municipal government released the first by-law of the area.Footnote23 Behaviours that were deemed as harmful to public order were forbidden, including littering, spitting, stepping on the grass, and painting graffiti on the surfaces of public property. Restrictions were also applied to activities that might interrupt others, such as sports games, peddling, superstition activities (e.g. fortune-telling), fighting, and carrying restricted knives or explosives. Moreover, activities such as massive gatherings, performances, publicity, and constructions needed permission from CPAMD before taking place. Regulations were tightened in 2009 to prohibit unapproved business affairs and events that may generate noise during working hours. More control measures were taken to ensure security and public order. In addition to the CPAMD’s private guards, CCTV cameras and security staff from other law enforcement departments were deployed on site.

There are two urban management personnel taking turns to work in this area. Each of them works from 9:30 to 14:00 for one day. It usually takes three to four months to get trained before one starts to work. In my understanding, although it is crucial to bravely enforce the law [mainly referring to the dispersal of street vendors], overenforcement should be avoided.

(Random interview with one urban management personnel in CPS)

There are too many street vendors in the square. I think the phenomenon would damage the image of the municipal square.

(Random interview with one user in CPS)

I think the government could regulate rather than just expel these vendors, for example, by defining a special zone for them to use within a limited time.

(Random interview with one user in CPS)

While these regulations may seem strict, a certain degree of flexibility still existed within the process of law enforcement. For example, the urban management personnel dealt with the problem of street vendors in a tolerant fashion, as they mainly limited the numbers of street vendors and gathering sites rather than completely driving them out. According to our on-site observations, some vendors were hovering around in the square with their goods, such as fruits, small exercise equipment, and toys, to attract buyers (). Three out of 27 random interviewees complained that there were too many vendors and accused them of disrupting the order of the square. Some interviewees also suggested that the government needed to strengthen their control. The presence of CCTV cameras and securities were generally not considered to be offensive, and a great number of square visitors felt safer with their presence.

User and use

Before the construction of CPS, the auditorium was the focus of the area and the locus for public life. The walled open space was occupied by green zones, parking lots, and mediocre buildings belonging to different work units. The opening of the square significantly changed this situation, and the area became increasingly vibrant, which facilitated public life in both formal and informal ways.

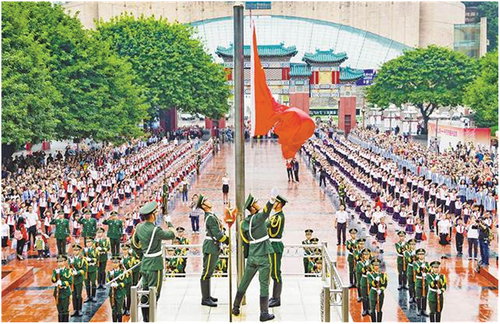

Formal activities

As an extension of the auditorium, the square immediately became an important location for diverse formal events. It hosted local, national, and international events (), such as the celebrations for the Reunifications of Hong Kong and Macao in 1997 and 1999, the Summer Olympics Torch Relay in Chongqing in 2008, and the celebration of the 90th anniversary of CPC’s Foundation (). During important festivals, more than one thousand volunteers, including hundreds of primary students, participated in national flag-raising ceremonies ().Footnote24–26 Influenced by the nationwide ‘square culture’, the district government also launched the Weekend Cultural Activities in the Square programme to enrich people’s cultural lives. The programme planned to hold large-scale events once a month and small-scale activities every week, and the content included music shows, dancing, drama, art performances, exhibitions of photos, calligraphy works, and folk arts.Footnote27 In 2004, the square won the honour of National Special Cultural Square for its various cultural activities.Footnote28

Figure 12. Summer Olympics torch relay in Chongqing, 2008.

Figure 13. Flag-raising ceremony held on 1 October 2017.

Table 5. Representative formal events held in the People’s Square between 1997–2019.

Informal activities

As a complement to the auditorium, the square was quickly adopted for a broad range of informal activities and attracted locals and tourists alike by providing them with a space for morning exercises, after work recreations, and other forms of social engagement. The field observations gathered during the course of this study construct a clear picture of a typical weekday in the square. Around 7 o’clock in the morning, nearby residents arrived to do morning exercises, such as radio callisthenics, square dancing, Tai Chi, and jogging. Their morning exercise usually lasted for about two hours, but some people lingered until 10 o’clock. At 9 o’clock, tourists started to arrive and take photos. Most tourists only stay less than half an hour. As the number of visitors grew, more people sat on benches under large trees or on the edge of the fountain. These visitors soon formed small groups to play chess or cards. After a short break at noon, the square bustled again around 2 o’clock. Tea house visitors showed up at this point, took their seats, and enjoyed teas and casual conversation. After 5 o’clock, young parents arrived to play with their children after work. These families usually stayed for about one hour. The climax of the day began at 7 o’clock when hundreds of people started the square dance in different groups and zones. The styles of dance were extremely diverse and included folk dance, Latin dance, and hip-hop. The magnificent dance show often attracted foreign tourists to join. With the backdrop of computer-controlled water fountains and a light show at dusk, people join the anonymous crowd and entered a grassroots space that was chaotic, vibrant, and informal (). Moreover, on weekends in the afternoon, people – most of whom were retired workers who lived nearby – used the square as a temporary open theatre. They sang and played musical instruments in the marginal area of the square. While these amateur performers showed off their talents, idle spectators joined them and become part of the scene ().

Discussion

This research examines the situated publicness of CPS, which is a typical species of publicly owned and managed public spaces in China’s reform era. The situated publicness of CPS is approached through a theoretical framework that focuses on three dimensions of PUPS.

In the dimension of planning and design, analytical review of historical archival material reveals that the first-round reconstruction of CPS that took place from 1997 to 2004 catalysed its transformation from the walled institution to a city square embedded in public life. Noticeably, the physical change in the first-round renovation improved accessibility and helped diversify programmatic functions. This change also altered the symbolic significance of CPS. The auditorium used to be the sole centre of the area and stood as an emblem of the political authority of the CPC regime. While still maintaining a degree of its political significance, the site started to disclose itself by offering local people a place to exercise, relax, and socialise. The second-round renovation that took place from 2005 to 2019 extended the square by adding the historical museum and commercial facilities (). The museum reconfirmed the historical significance of CPS and also helped transform the area into a popular sightseeing location, which further enriched local leisure cultures. In terms of design style , the CPS’s symmetrical form and high greening rate are representative of Chinese municipal squares in both the pre-reform and reform eras. This style is closely linked with political symbolism and embodies the top-down structure governing space productions in these periods. CPS was no exception to banal routines commonly seen in the municipal squares built during the 1990s in mainland China (Wang, Xia, and Yang Citation2000; Cao Citation2005). Despite its relatively humble scale, the square was designed in a Beaux Art-inspired spatial configuration and has a high greening rate. Commercial facilities were deployed separately from the square to maintain a certain atmosphere.

With respect to governance and management, the CPS area was owned and managed by public authorities, except for the two tea houses. Consistent with previous research (Madanipour Citation2003; Akkar Citation2003; Kohn Citation2004), this study reconfirms the crucial role of public ownership of public space. In addition to the efforts made by the design team (e.g. the former chief architect of CADI) to prevent the over-commercialisation of the site, public ownership played a crucial role in ensuring the reconstruction of CPS. Moreover, the general public helped maintain CPS, and debates over proper behaviours in public spaces took place in the local newspaper. With respect to control measures, tight regulations, CCTV cameras, and security staff are deployed on site. At least officially, the main purpose of these measures is to safeguard public security. Meanwhile, a tolerance towards street vendors on the part of law enforcement is observable, which has objectively increased the liveness of the square.

Financial support is an indispensable component of these changes. The SCFE system drove the CPAMD to enter the emerging market economy within an officially acceptable limit. This reform not only improved the management efficiency but also generated income to ensure the daily maintenance of CPA and CPS. In fact, this method of financing public space is not an isolated case and deserves further investigation. China’s market economy reform has enabled more open multi-party management systems that allow varied degrees of marketisation of PIs. A by-product of the marketisation of PIs is a blurred boundary between the public and private sectors that was sharply divided in the planned economy era. The CPS case demonstrates that the loosening of authoritative control over ownership has fostered the life of public spaces while also causing new practical problems. For instance, leasing out the use right of public spaces may spark debates about publicness. In the case of CPS, the privately-run tea houses became a source of critique and were viewed as impairing publicness. One valuable lesson of the CPS case is that the actual structure, processes, participations, and executions of governance and management may have a more significant influence on PUPS than property rights. This finding aligns with Ekdi and Çıracı’s study on publicly owned and managed space (2015), in which they reveal that the publicness level is largely dependent on urban politics and the public authority’s governance policies. It also echoes De Magalhães and Freire Trigo’s study of public space management arrangements based on the transfer and contracting-out of managerial responsibilities to organisations outside the public sector (Citation2017), which reports that contracted-out management of public space might not necessarily undermine publicness as long as it is underpinned, regulated, and sustained by clear judicious accountabilities and proper decision-making processes transparent to all key stakeholders.

In attending to shedding light on the everyday practice of users, this study illustrates how CPS has been transformed into a site for social interactions and daily recreation and become an embodiment of cultural-historical memories. Along with the CPA and the museum, CPS has become a popular sightseeing spot for visitors, and the diversity of both its users and the formal and informal activities that take place on the site are indicators of the social cohesion fostered by the square. Building on the observations of previous studies (Wang Citation2001; Xing Citation2011; Wang Citation2018), the CPS case shows how public life has been de-politicised in a way that parallels China’s shifting focus from political movement to economic development. Coinciding with the rise of leisure culture, municipal squares not only rapidly increased but also took on drastically different characteristics. In the post-reform era, the squares actively shape people’s cultural and social lives in both expected and unanticipated ways. Meanwhile, formal and informal events (e.g. flag-raising ceremonies and square dance) instil mass culture with a type of collectivist memory. For example, many aged people, who participate in the square dances, share strong emotional affiliations with the collective lives they experienced in the pre-reform era (Lin and Bao Citation2016). Despite a movement towards secularisation, political authority and collectivist culture continues to shape users’ perceptions of the public space.

Taken together, the development of municipal squares in reform-era China involves complicated political, economic, environmental, social, and cultural changes. For local governments, municipal squares are more of a planning apparatus that they can use to tackle pressing environmental and sustainability issues, re-imaging the city, and enhance its regional competency on both international and domestic stages.

Conclusion

With the rise of Neoliberalism, POPSs have developed rapidly worldwide. The exclusion and underuse of POPSs have been often criticised, and the issue of PUPS was brought on the agenda. Within this predominant POPs paradigm, the private ownership of space has been upheld as the primary factor that defines publicness. However, a growing body of literature has indicated that PUPS has multiple dimensions, including planning and design, governance and management, and user and use. This paper contributes to the existing research by comprehensively investigating the publicness of a typical example of publicly owned and managed public space in reform-era China and enriching the discussion of PUPS through an emphasis on sociocultural and political concerns.

The research findings emphasise the significant impacts of specific sociocultural and political contexts on PUPS. Through an in-depth case study of CPS, this paper offers an account of the profound changes in the PUPS of municipal squares, which were driven by political and economic restructuring as well as environmental and cultural transitions that emerged during China’s reform. Municipal squares in reform-era China usually possess better accessibility, finer comfort, and greater sustainability. They are overseen by a more flexible management system and designed to accommodate increasingly diversified functions and more vibrant urban lives. Meanwhile, as a domain of transnational practice, the localisation of municipal squares in reform-era China often involves nationalist expression of political power. This symbolism usually materialises in the unifying axes of architectural compounds and derived forms of classical building styles of imperial China.

The research findings also support the view that governance and management exert a profound impact on the publicness of publicly owned and managed public spaces. The role of governance and management, at least in the CPS case, outweighs the factors of public ownership and formal innovations in planning and design, which have been rendered in multiple cases as pivotal elements in constructing public space. Diversified ownership and flexible management systems can help promote efficiency of management and maintenance. Meanwhile, a proper judicious decision-making process, due management structure, and a more transparent management procedure are indispensable components for sustaining the healthy development of PUPS.

Finally, a number of potential limitations need to be noted. First, the study of the sub-dimensions of control, user and activity is based on on-site observations that took place in 2019, though the period of focus in this analysis extended from 1997 to 2019. Semi-structured interviews with members of the managing staff and users of CPS who were active in previous decades could help complete the story. Second, a wider survey of the general public’s perceptions of the publicness of CPS may offer an opportunity to extend the scope of the current study. Third, due to limitations of available sources, this research confines itself to the examination of one particular type of publicly owned and managed public space (i.e. the municipal square). Further research may benefit from an enlarged investigation scope to understand how governance and management could impact PUPS in distinct types of public spaces, such as urban and communal parks, pedestrianised streets, and station squares. Generally speaking, a historical account of the transformation of PUPS from the planned-economy to the market-economy era still needs to be pursued. This missing component is not only essential to understanding the contemporary Chinese praxis of public space but may also further enrichen intellectual discourses centred on the publicness of publicly owned and managed public spaces.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank all interviewees, especially architect Ronghua Chen, for providing valuable information and access to data sources. The authors also express special thanks to Dr. Xin Jin for the careful proofreading and helpful suggestions; the China Scholarship Council for its funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Local Records Office of Dalian. 2006. Dalian shi zhi lüyou zhi [Local Records of Dalian, Tourism Records]. Beijing: China Travel & Tourism Press.

2. Records Office of Shanghai and Contemporary Shanghai Research Institute. 2008. Shanghai gaige kaifang 30 nian tuzhi [Thirty years of the reform and opening-up in Shanghai]. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe [Shanghai People’s Press].

3. Zhao, X. 1996. “Yindao shimin yangcheng jiankang wenming kexue shenghuo xiguan [Guide the people to foster healthy, civilised, scientific lifestyle],” Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily]. 3 March 1996(4).

4. Wang, S. 1997. Zhoumo, dao guangchang qu [Let’s go to the square on weekends]. Zhongguo jizhe [Chinese Journalist]. (01), 65.

5. Wang, Y. 1995. Caise zhoumo gongcheng guangchang huodong longzhong kaimu [Opening of the colourful weekend project of square cultural activities]. Da wutai [Grand Theatre]. (04), 29.

6. Compiling Committee for Local Records of Shenzhen. 2004. Shenzhen shi zhi 1979–2000 [Gazetteer of Shenzhen 1979–2000]. Beijing: Fangzhi chubanshe [Local Records Publishing].

7. Compiling Committee for Huangpu District of Shanghai. 1996. Huangpu qu zhi [Local Records of Huangpu District]. Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexue chubanshe [Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press].

8. Management Committee of Chongqing Urban Construction. (1997). Chongqing jianzhu zhi [Chronicles of architecture in Chongqing]. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press.

9. Chongqing Ribao. 1997. “Bianzhe de hua [Words from the editors],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily], 5 June 1997 (5).

10. Yu, H., & Deng, X. “Renmin guangchang jianwenlu [Phenomena oberserved in CPS],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily], 5 June 1997 (5).

11. Chongqing Ribao. “Li ci cunzhao [Take these photos as evidence],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily], 6 June 1997 (6).

12. Fan, S. “Shehui huhuan gongde yishi [Society calls for consciousness of public morality],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. 17 June 1997 (6).

13. Yu, H. “Qingting tamen shuo guangchang [Please listen to their talks about CPS],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily], June 9 1997 (6).

14. Qing, J. “Weile chengshi de rongyan [For the good appearance of the city],” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily], 11 June 1997 (6).

15. Yu, H. (1997b). Weihu renmin guangchang de zhiyuanjun [Volunteers to maintain People’s Square]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 6, 1997 (6).

16. Tao, W. (1997a). Jingshen wenming jianshe cong qunzhong guanxin de shi zhuaqi [Spirit civilisation construction starts from what people care about]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 6, 1997 (6).

17. Tao, W. (1997b). Qing aihu zanmen ziji de guangchang [Please take care of our own square—interview with deputy to Chongqing Municipal People’s Congress Tingxiao Huang]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 13, 1997(6).

18. Gan, G. (1997). Fazuo qingjie ruhe [How about making cleaning as punishment]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 29, 1997 (6).

19. Gao, Z. (1997). Duowei shehui wenming jin yiwu [Contribute more to social civilisation]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 29, 1997 (6).

20. Sun, Y. (1997). Rang bu wenming xingwei baoguang [Exposing uncivilized behaviours]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 18, 1997 (6).

21. Sun, Y. “Rang bu wenming xingwei baoguang [Exposing uncivilised behaviours].” Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 18, 1997.

22. Yu, H. (1997c). Buwenming xianxiang de beihou—renda daibiao Xiaozhong Ding tan renmin guangchang [Behind the uncivilised phenomena: deputy to National People’s Congress Xiaozhong Ding talking about CPS]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. June 13, 1997 (6).

23. Chongqing Ribao. (1997a). Guanyu jiaqiang Chongqingshi renmin dalitang he renmin guangchang guanli de tonggao [Notification to reinforce management of CPA and CPS]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. May 25, 1997 (1).

24. Zhang, D. (1996). Miandui shensheng de guoqi: Chongqingshi 1996 nian chunjie guoqi shengqi yishi suji [Facing the sacred national flag: sketch of the flag-raising ceremony in Spring Festival of 1996 in Chongqing]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. February 15, 1996 (1).

25. Yan, R. (2013). Zhufu zuguo, zhufu Chongqing: woshi juxing 2013nian yuandan sheng guoqi yishi [Bless the motherland, bless Chongqing: Chongqing held the flag-raising ceremony on the first day of 2013]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. January 2, 2013 (1).

26. Chongqing Ribao. (2017). Renmin guangchang juxing sheng guoqi yishi [Flag-raising ceremony was held in CPS]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. October 2, 2017. Retrieve from http://www.cq.gov.cn/zwxx/jrcq/content_76910 [2019-8-29].

27. Zeng, X. (1997). Zhoumo guangchang wenhua huodong zuo lakai weimu [Weekend Cultural Activities in the Square started yesterday]. Chongqing Ribao [Chongqing Daily]. December 29, 1997 (1).

28. Chongqing Ribao. (2009). Yuzhong Changdu jiangchuan wenhua huimin, ningshen juli chengshi lingpao [The Yuzhong District, to spread culture and develop the city]. July 30, 2009 (8).

References

- Akkar, Z. M. 2003. The ‘Publicness’ of the 1990s Public Spaces in Britain with a Special Reference to Newcastle upon Tyne. UK: Newcastle University.

- Arendt, H. 1998. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Cao, W. 2005. “Chengshi guangchang de renwen yanjiu [Research on the Humanism of City Squares].” Ph.D’s diss., China: Graduate School of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

- Carmona, M. 2010. “Contemporary Public Space, Part Two: Classification.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (2): 157–173. doi:10.1080/13574801003638111.

- Carr, S., M. Francis, L. G. Rivlin, A. M. Stone, et al. 1992. Public Space. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, R., ed. 2016. Chongqing renmin dalitang jiazi ji [60 Years History of the Chongqing Great Hall of the People]. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press.

- Chen, Z. 2010. “The Production of Urban Public Space under Chinese Market Economic Reform.” Doctoral diss., University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR.

- De Magalhães, C., and S. Freire Trigo. 2017. “Contracting Out Publicness: The Private Management of the Urban Public Realm and Its Implications.” Progress in Planning 115: 1–28. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2016.01.001.

- Duan, G. 2009. “Zishou zizhi xianxiang yanjiu [Research on the Phenomenon of Self-funding and Self-expending Units].” Master’s diss., Nankai University.

- Ekdi, F., and H. Çıracı. 2015. “Really Public? Evaluating the Publicness of Public Spaces in Istanbul by Means of Fuzzy Logic Modelling.” Journal of Urban Design 20 (5): 658–676. doi:10.1080/13574809.2015.1106919.

- Ercan, M. A., and N. O. Memlük. 2015. “More Inclusive than Before? The Tale of a Historic Urban Park in Ankara, Turkey.” Urban Design International 20 (3): 195–221. doi:10.1057/udi.2015.5.

- Gaubatz, P. 2008. “New Public Space in Urban China. Fewer Walls, More Malls in Beijing, Shanghai and Xining.” China Perspectives 2008 (4): 72–83. doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.4743.

- Gaubatz, P. 2019. “New China Square: Chinese Public Space in Developmental, Environmental and Social Contexts.” Journal of Urban Affairs 43 (9): 1235–1262. doi:07352166.2019.1619459.

- Gehl, J., and B. Svarre. 2013. How to Study Public Life. trans K. A. Steenhard.Washington DC: Island press.

- Habermas, J. 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Trans T. Burger, and F. Lawrence.Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kohn, M. 2004. Brave New Neighborhoods: The Privatization of Public Space. New York: Routledge.

- Langegger, S. 2017. Rights to Public Space: Law, Culture, and Gentrification in the American West. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Langstraat, F., and R. Van Melik. 2013. “Challenging the ‘End of Public Space’: A Comparative Analysis of Publicness in British and Dutch Urban Spaces.” Journal of Urban Design 18 (3): 429–448. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.800451.

- Lee, D. 2020. “Whose Space Is Privately Owned Public Space? Exclusion, Underuse and the Lack of Knowledge and Awareness.” Urban Research & Practice 1–15. doi:10.1080/17535069.2020.1815828.

- Liang, X. 1999. “Chengshi gonggong kongjian xingxiang tanxi—cong Chongqingshi renmin guangchang jianshe kan kechixu fazhan de chengshi gonggong kongjian xingxiang [Exploration on the Image of Urban Public Space—discussing the Sustainable Urban Public Space Image by the Construction of Chongqing People’s Square].” Chongqing Jianzhu [Chongqing Architecture] 73 (3–4): 17–22.

- Lin, M., and J. Bao. 2016. “Chengshi guangchangwu xiuxian yanjiu: yi Guangzhou weili [Research on ‘Carnivalesque Dancing’: A Case Study of Guangzhou].” Lüyou Xuekan [Tourism Tribune] 31 (6): 60–72.

- Liu, X. 2008. “Jianzhu xingxiang, chengshi sheji, chengshi guangchang [Architectural Image, Urban Design, Urban Square].” Chinese Landscape Architecture 1: 40–42.

- Lopes, M., S. S. Cruz, and P. Pinho. 2020. “Publicness of Contemporary Urban Spaces: Comparative Study between Porto and Newcastle.” Journal of Urban Planning and Development 146 (4): 04020033. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000608.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., and T. Banerjee. 1998. Urban Design Downtown: Poetics and Politics of Form. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Madanipour, A. 2003. Public and Private Spaces of the City. London, New York: Routledge.

- Mantey, D. 2017. “The ‘Publicness’ of Suburban Gathering Places: The Example of Podkowa Leśna (Warsaw Urban Region, Poland).” Cities 60: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.07.002.

- Németh, J., and S. Schmidt. 2011. “The Privatization of Public Space: Modeling and Measuring Publicness.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 38 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1068/b36057.

- Németh, J. 2009. “Defining a Public: The Management of Privately Owned Public Space.” Urban Studies 46 (11): 2463–2490. doi:10.1177/0042098009342903.

- Peng, Y. 2011. Zhili biange xia shizheng guangcheng de kongjian biaoda [Spatial Expression of Municipal Squares under the Transition of Governance]. China: Zhejiang University.

- Sennett, R. 1977. The Fall of Public Man. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Varna, G., and S. Tiesdell. 2010. “Assessing the Publicness of Public Space: The Star Model of Publicness.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (4): 575–598. doi:10.1080/13574809.2010.502350.

- Wang, D. 2018. The Teahouse under Socialism: The Decline and Renewal of Public Life in Chengdu, 1950-2000. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Wang, J. 2001. “Culture as Leisure and Culture as Capital.” East Asia Cultures Critique 9 (1): 69–104. doi:10.1215/10679847-9-1-69.

- Wang, K., J. Xia, and X. Yang. 2000. Chengshi guangchang sheji [City Square Design]. Nanjing: Southeast University Press.

- Wang, Y., and J. Chen. 2018. “Does the Rise of Pseudo-public Spaces Lead to the ‘End of Public Space’ in Large Chinese Cities? Evidence from Shanghai and Chongqing.” Urban Design International 23 (3): 215–235. doi:10.1057/s41289-018-0064-1.

- Wei, F. 2019. “Public Institution Reform in China from the Perspective of Fiscal Logic.” International Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 7 (2): 28–32. doi:10.11648/j.ijebo.20190702.11.

- Xing, G. 2011. “Urban Workers’ Leisure Culture and the ‘Public Sphere’: A Study of the Transformation of the Workers’ Cultural Palace in Reform-Era China.” Critical Sociology 37 (6): 817–835. doi:10.1177/0896920510392078.

- Yang, Z. 2009. Evolution, Form and Public Use of Central Pedestrian Districts in Large Chinese Cities. United Kingdom: Cardiff University.

- Yu, K. 2008. “Zhongguo zhili bianqian 30 nian [Transition of the Governance of China in Thirty Years, 1978-2008].” Jilin University Journal Science Edition 3: 5–17.

- Zheng, Y. 2008. “Chongqing zhongguo sanxia bowuguan [Chongqing China Three Gorges Museum].” Jianzhu Xuebao [Architectural Journal], no. 1: 57–59.

- Zhu, J. 2000. “Urban Physical Development in Transition to Market: The Case of China as a Transitional Economy.” Urban Affairs Review 36 (2): 178–196. doi:10.1177/10780870022184822.