ABSTRACT

The main objective of this research is to evaluate public ‘pocket’ spaces in Al Wehdat Refugee Camp, Jordan. The paper aims to identify the challenges associated with implementing pocket space upgrades and make visible some opportunities that enhances their socio-economic viability. By doing so, the research seeks to contribute to providing long-term solutions for refugee settlements, going beyond basic shelter provision, and creating community facilities and public spaces to enhance the living conditions and well-being of camp residents. The study addresses three key questions: What are the different types of pocket spaces in the camp? How do community members perceive their potential uses? What are the challenges and opportunities for implementing pocket space upgrades in Al Wehdat camp? The research utilised mapping and semi-structured interviews, which revealed various pocket space types. This exposed distinct pattern of public space appropriation within different camp zones, including informal privatisation of public space, linked to the spaces’ morphology rather than ownership. Community preferences for upgrading strategies differed based on pocket types, with small-scale greening and place-making strategies favoured in informally privatised pockets to maintain privacy, while parks or playgrounds were preferred in mixed-use areas. The research found that the main challenge facing public space upgrades lies in the conflicting dual management structure between UNRWA and the local municipality, necessitating administrative strategies for long-term improvement. Community involvement and heritage preservation proved crucial for sustaining upgrades. While specific to Al Wehdat, the findings offer insights into creating community public spaces in refugee camps and informal settings, potentially benefiting other long-term refugee camps.

1. Introduction

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by the middle of 2023, the worldwide number of forcibly displaced people reached 110 million, with refugees accounting for 32.5 million (UNHCR Citation2024). The immediate response from responsible agencies and surrounding countries is to build temporary (short-term) shelters for those fleeing from areas of civil unrest, violence, or natural disasters called refugee camps. These are spaces that tend to follow the planning guidelines as set out by the UNHCR which aim to maintain ephemerality and could also be interpreted as a political manoeuvre to ensure the camps remain as transient spaces (Alshoubaki and Zazzara Citation2020). This design is meant to fulfil only the basic needs of survival as merely transient spaces. Camp spaces where responsible authorities can control and monitor the inhabitants, and therefore, often considered as inhumane – on the long term – to the point of threatening their ‘physical, psychological and moral integrity’ (Hart, Paszkiewicz, and Albadra Citation2018, 371). This is due to the fact that the average stay for refugees in those camps usually exceeds and goes beyond the expected timeframe, an average of around 17 years (Xu, et al. Citation2019). Thus, not covering other socio-economic aspects that suit their individuality, identity and culture becomes an apparent issue. As the crisis prolongs, refugees themselves try to address this by often transform and expand their controlled built environment, using spatial violations as means of reclaiming the space, and challenging the imposed top-down camp planning (Alshoubaki and Zazzara Citation2020; Dalal et al. Citation2018; Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016). Therefore, challenging the binary concept of permanent versus temporary (Stevenson and Sutton Citation2012).

The gradual unplanned expansions enrich the identities of the residents but often lack adequate community facilities, public spaces, and buildings. These spaces are essential for socio-economic development, especially for women and children who need access to outdoor areas for social interaction and physical activities (Dalal et al. Citation2018). The 2007 UNRWA camp improvement program highlighted this need by creating a public square for women in Fawwar Refugee Camp, Palestine (Hilal, Citationn.d.). Through a participatory design process, women discussed their roles and needs in public spaces, leading to the establishment of a plaza that became a symbol of their struggle and a venue for regular activities. This initiative inspired a women’s movement and demonstrated the broader social and economic benefits for the community. The Fawwar example underscores the importance of such public spaces and the potential for replicating these projects in other camps.

Another example can be found in Campo de la Cebada, in Madrid. In 2006, a building was demolished to make way for a new sports complex in the city centre. After the demolition, the planned development had to be stopped due to the financial crisis, leaving a large, vacant and useless lot in the very heart of the city. Since then, and for many years thereafter, the neighbours autonomously reclaimed the lot through low-key, short-term interventions. They filled it with temporary furniture and plants, invited street artists to paint its walls, and, most important of all, constantly organised events that would invite people. In a few years, the neglected lot became one of Madrid’s most vibrant and lively places (Enia and Martella Citation2020). This transformation underscores the profound impact that reclaimed public spaces can have on urban life. By reclaiming and revitalizing neglected areas, communities can create vibrant social centres that enhance the quality of life for all residents.

However, major open spaces are difficult to achieve in such dense informal settings. The opportunity here is suggested within the unplanned extensions resulting with many leftover ‘pocket’ spaces that are not utilised and not functional in their current state. These pocket spaces, while small in size, can be considered a real potential to spark liveability and a sense of belonging in the respective communities if they are transformed through participatory actions. ‘[M]icro-areas in-between buildings’ that could impact the residents’ socio-economic conditions by transferring them into a garden, an outdoor library, an open public space, or a community centre (Jano, Teqja, and Hasa Citation2020, 47)

In fact, several studies refer to abandoned and neglected areas as an opportunity for regeneration projects, where they can be transformed into areas of co-working, co-housing, and public spaces (Girard, Nocca, and Gravagnuolo Citation2019; Sakay, Sanoni, and DEng Citation2011). Patrick Geddes (1915) proposed a ‘’surgical’’ approach for gradually upgrading and adaptive reusing small, abundant urban areas to consider the community’s needs while creating economic opportunities and allowing a more sustainable, circular development (Rao-Cavale Citation2017, 73). Jano et al. (Citation2020, 47) suggested reclaiming the ‘Third Landscape Through Participatory Processes and Game Theory’. This refers to suggesting a series of pocket parks by redesigning the neglected pocket spaces and analysing the third landscape as the residual green micro-areas in-between buildings. Lastra and Pojani (Citation2018, 749) used the concept of ‘Urban acupuncture’, suggesting using smaller-scale urban design interventions to alleviate the stress and social pathologies experienced in informal settlements in Mexico City. Most of those studies have explored the potential of using small-scale urban interventions to transform pocket spaces into public and green areas in informal settlements for socio-economic improvements. However, it is crucial to note that these discussions have mainly focused on informal settlements rather than long-term refugee camps.

Long-term refugee camps share some physical similarities with informal settlements, such as organic urban morphology and incremental architecture (Dovey et al. Citation2020; Kamalipour and Dovey Citation2020; Venerandi, Iovene, and Fusco Citation2021). However, both terms are distinct in their emergence under forced conditions and the political restrictions placed on refugees. Consequently, refugee camps’ perceptions and socio-economic dynamics may differ significantly from those observed in other global south informal settlements. Alnsour and Meaton (Citation2014) and Maqusi (Citation2017) studies on Palestinian refugee camps highlighted a significant concern regarding the interventions within these camps, irrespective of their duration. The sensitivity arises from apprehensions about potentially undermining the right to return for refugees. It is essential to navigate such interventions with caution, ensuring that the rights and aspirations of the refugees are respected and upheld. Balancing the need for improvements within the camps while preserving the right of return remains a complex and delicate challenge that requires careful consideration and engagement with the refugee community.

In Jordan, informal settlements take on distinct meanings based on their origins and characteristics. Firstly, there are settlements such as old towns or illegal housing, which emerged without adherence to formal planning regulations. This phenomenon is particularly prevalent in eastern Amman and is a legacy of the delayed implementation of comprehensive city planning, which only began in 1966 with the Town and Country Planning Act (Abu-Dayyeh Citation2004). Despite homeowners having legal ownership, these houses often fall outside planning regulations (Ababsa Citation2010; Alnsour Citation2016). On the other hand, there are informal settlements resulting from forced migrations, mainly refugee camps established due to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories. In these settlements, compliance with planning regulations is lacking, and property ownership is often unclear, with the refugees lacking legal documentation to assert their ownership of their long-term homes (Oesch Citation2017). The distinction between the two main forms of informal settlements in Jordan is essential because it underscores the multifaceted nature of urban informality in the country. Understanding the different historical, political, and socio-economic factors that created these different informal settlements, and the characteristics of these settlements, is crucial for devising targeted and effective policies to address their specific challenges. This research focuses only on the refugee camps in Jordan, but not on other kind of informal settlements.

In particular, this paper uses Al Wehdat Refugee Camp in Jordan as a case study to explore public ‘pocket’ spaces in refugee camps through mapping, evaluation, and envisioning scenarios for future socio-economic usages. It highlights the need for long-term solutions from the perspectives of its residents that go beyond providing basic shelter to refugees, adequate community facilities and public spaces. Therefore, exploring the potential of these underutilised ‘pocket’ spaces empowers socio-economic development. By doing so, the paper addresses the following research questions:

What are the different types of pocket spaces that can be considered within the context of the long-term refugee camp?

How do community members perceive their potential uses?

What are the specific challenges and opportunities found in small-scale pocket spaces in the Al-Wehdat Refugee camp?

2. Methodology

The methodology employed in this study aimed to comprehensively map and assess the pocket public spaces within Al Wehdat Refugee Camp, while also envisioning potential scenarios for socio-economic development. Elements of ethnographic research, such as observations, field notes, and semi-structured interviews were implemented to an appropriate level for the research questions. The field work took place between September 2022 and February 2023. The variables used to analyse the spatial characteristics of the pocket spaces in this research are inspired by and combine variables from Watson (Citation2003) and Kamalipour and Dovey (Citation2020), who studied the spatiality of informal settlements in the Global South. These variables are size, accessibility, location, land use, space zoning/ownership, existing community reappropriation, and potential for expansion. Accordingly, the methodology of this research consisted of three distinct phases:

Phase I: Identifying potential open spaces for socio-economic activities.

Physical analysis through the camp’s maps and satellite imagery: 14 potential pocket spaces were identified based on spatial characteristics variables such as size, accessibility, location, land use, space zoning/ownership, existing community reappropriation, and potential for expansion. These variables were informed by the studies of Watson (Citation2003) and Kamalipour and Dovey (Citation2020). These are spaces of path intersections, roadsides, setbacks, or leftover spaces in the dense built environment.

Site visits and observations informed by ethnographic approaches: Multiple site visits were conducted to those 14 spaces to capture the varying patterns of social use and fluctuations of activities throughout the week as well as the different times of the day. The visits also included taking photos as well as direct and indirect observations.

Phase II: Short-listing and pocket selection: A systematic and structured analysis using a decision matrix was employed to analyse and select the pockets with the highest potentials. This is done by assigning values and importance factors to each criterion (the analysed spatial characteristics in the previous step) and comparing the pockets (scale 1 to 5). This concluded with six final pocket spaces that were then the focus of semi-structured interviews. .

Phase II: Community perspective: Fifteen semi-structured interviews have been conducted with residents living around and/or using the selected six pockets. This is done to further understand their current uses, how they envision their potential development, and the challenges facing future upgrades. The fifteen-interviewee sample aimed to have equitable gender representation of both men and women and from different age groups. This is to get a more representative narrative of the spatial uses of the public spaces in the camp in general, and pockets in specific.

2.1. Sample size and interviewees selection

In a study reviewing sample sizes in quantitative research by Guetterman (Citation2015), it was found that common sizes are 10, 20, 30, and 40. Studies that employs ethnographic approaches typically involve six to 33 participants, while narrative inquiries usually range from 1–24 participants. Atallah et al. (Citation2018) interviewed six participants from each of five Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, aligning with Guetterman’s findings. In contrast, Mahamid (Citation2020) interviewed five extended families totalling 30 members in a study on intergenerational trauma in a West Bank refugee camp. Based on these precedents, the current study aimed for a sample of 10 to 20 interviewees, with 15 participants agreeing to participate and be quoted in the research. Every interview varied in duration, spanning from 20–45 min, contingent upon the participant’s engagement level and the extent of conversation depth. Employing a semi-structured interviewing method provided adaptability regarding interview length and subject matter. This strategy facilitated the exploration of specific areas of interest through follow-up inquiries, prompted by the participant’s input.

The selection process for interviewees began with an initial outreach on a Facebook group dedicated to camp residents. Where a participant residing within the camp facilitated our understanding of the camp and helped us navigate the intricacies of the camp’s dynamics, which would have otherwise been challenging due to the complex social, cultural, and logistical factors involved. With their guidance, we approached and met residents living around the identified pocket spaces, leveraging their local knowledge and connections to initiate conversations and arrange interviews. This collaborative effort enabled the researchers to access insights from both inside and outside the camp, enriching our understanding of its dynamics.

2.2. Introducing research case study: Al Wehdat refugee camp

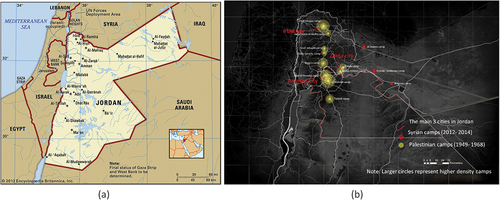

In Jordan, there are currently 10 Palestinian and 3 Syrian refugee camps, most functioning as permanent settlements, part of over 55 refugee camps in the Levant region. Responsibility for managing them in Jordan falls on both the government and UN relief agencies. Established due to the Israeli occupation in 1948, 10 Palestinian camps were created, with 500,000 refugees settling in Jordan (Khawaldah Citation2016). Among them, Al Hussein and Al Wehdat camps in Amman were established in 1952 and 1955, respectively () (UNRWA Citation2020). Al Wehdat camp, integrated into Amman, lacks clear boundaries. In its early days, it housed 5,000 people in tents, where each family was allocated 100 m^2 ‘units’ or ‘Wehda’ for their tent (Alnsour and Meaton Citation2014). It has since transitioned into permanent structures. The camp now accommodates an estimated 60,000 residents in the same 0.48 km^2 area, making it very densely populated. Notably, UNRWA secured a 100-year lease on the land, set to expire in 2055 leaving questions about the future of its residents (Oesch Citation2017).

Figure 1. (a) Jordan is situated between politically conflicted areas, making it a main refugee zone. Source (Britannica Encyclopaedia, 2012). (b) Graphical representation of camps locations and densities of camps in Jordan, 2021–2022. Larger circles indicate higher density camps. Author’s map. Generated using Open Street data in ArcGIS Pro.

Due to the incremental architecture and continued generational expansions, both horizontally and vertically, the available green areas and public recreational spaces in the camp have significantly decreased over time and are almost non-existent today ().

3. Analysing potential pocket spaces in Al-wehdat refugee camp

3.1. Phase 1: identifying potential open spaces for socio-economic activities

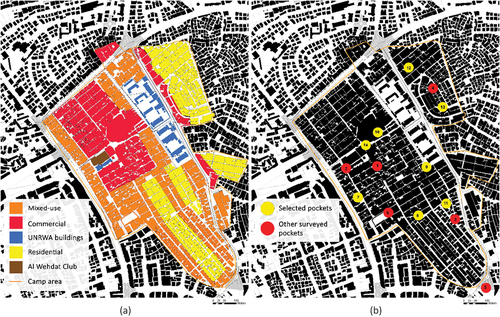

The initial maps provided by the Department of Palestinian Affairs in Amman were useful in understanding the general spatial layout and plot distribution within the camp. However, they did not include information about the built-up area of the camp, only the plots themselves. To fill this gap, satellite images and Open Street data in ArcGIS Pro were utilised to generate a map that specifically highlighted the built-up areas (solid and void map, ). By analysing this map, several small void spaces could be observed within the camp. Initially, 22 void spaces were selected. This initial selection was based on perceived size, as well as covering different zones within the camp (). Other void spaces, or ‘’pockets’’ as will be referred to them later, were disregarded due to appearing smaller, or due to being in proximity to larger ones.

To overcome these limitations and investigate the potential pocket spaces within the voids identified on the maps, on-site surveys were conducted. These surveys aimed to gather more detailed information about the void spaces and assess their suitability as potential pocket spaces. The results of the site surveys revealed that out of the 22 initially identified voids, 14 of them demonstrated the potential to be utilised as pocket space.

3.2. Phase 2: short-listing and pocket selection

The typological analysis of the selected 14 pocket spaces in Al Wehdat refugee camp went under a comprehensive evaluation of both their physical and social dimensions. This analytical approach was inspired by the research approach of Kamalipour and Dovey (Citation2020) utilised in their typological analysis of informal settlements. The criteria used for analysing the pockets are summarised in .

Table 1. Pocket space characteristics analysis.

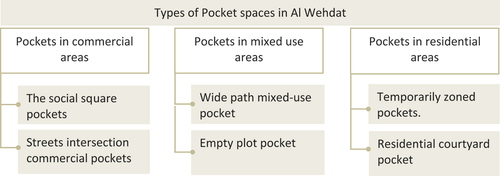

From , the pocket spaces in Al Wehdat refugee camp can be divided into three types based on their location (within the camp zones), spatial characteristics, space ownership, and observation of their current utilisation by the residents. Accordingly, the spaces were grouped into pockets in commercial areas, residential areas, and mixed-use areas ().

3.2.1. Pockets in the commercial areas

Two types of pocket spaces were observed in the commercial area of Al Wehdat refugee camp:

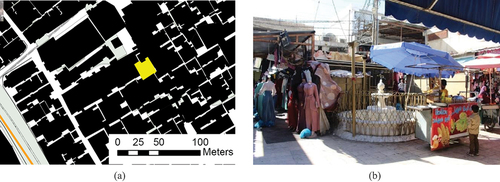

The social square pocket: Located at the intersection of 3 or more pedestrian allies. They are used as a hub for informal street stalls and as a social sitting space ().

The streets intersection pockets: Located at the intersection of main/secondary streets in the camp. They are characterised by having both vehicles and pedestrian access, and are used mainly as goods drop-off area, as well as spaces for street stalls see .

3.2.2. Pockets in residential areas

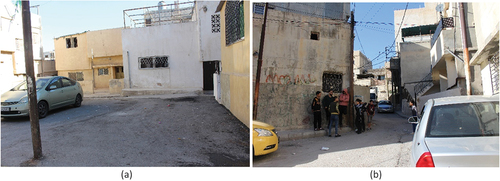

Pocket spaces in residential areas have controlled/limited car access and seems to be claimed for private use by the surrounding residents as a car park and their own social space.

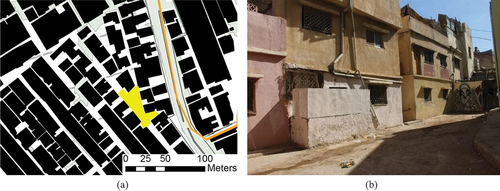

Residential courtyard pocket: Surrounded by 3 of 4 sides of residential buildings. They are used mainly as private car park and as a seating area for the residents using concrete doorsteps (also known as Atabat, as labelled by Maqusi (Citation2017)) ().

Temporarily zoned pockets: They are made from leftover spaces between the 100 m2 family plots and serves multiple functions without demarcated separation activities, such as car parking, play areas, and various temporary activities such as funeral gathering space and weddings (as was elaborated by the interviews, section 3.3) ().

3.2.3. Pockets In mixed-use areas

Mixed-use areas in Al Wehdat camp are shared public spaces for both commercial and residential purposes. They comprise three main types of pocket spaces:

Wide path mixed-use pocket: Spaces that link between the residential and commercial zones and receives more pedestrian traffic as a result. This seems to make them more welcoming for public use (not just the residents of the surrounding buildings). They are used partially as a car park to access the market, and as an informal playground. Such spaces do not seem to present an attraction for the stall sellers ().

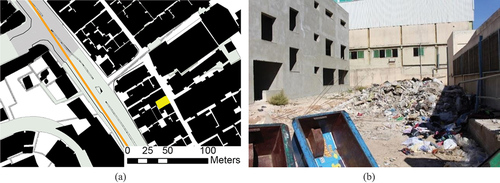

Empty plot pocket: A formally demarked plot of land owned by the government or an NGO and surrounded by NGO buildings. There seems to be a very limited number of empty plots within the camp. Until the point this research was conducted (2021–2022), there was no formal plans to develop any of these areas as public spaces for the camp (Based on discussions with a representative from the Department of Palestinian Affairs (DPA) and reviewing the existing infrastructure plan of the camp.) The spaces are currently used mainly as sites for dumpster, and some are used as parking and informal playground as well ().

The identification of these different types of pocket spaces and the understanding of the different patterns of their uses are crucial for developing effective strategies for enhancing leftover spaces in the camp and expanding their use as public spaces within the camp. Therefore, there is a need to develop a comprehensive understanding of how the camp community engages with these diverse pocket spaces, their perceptions regarding their potential uses, and what do they believe are the specific challenges facing public space upgrades such the upgrades of pocket spaces, within the context Al Wehdat refugee camp (Research questions 2 and 3).

Due to the time and resources required to do community interviews around all the surveyed pockets in this study, it was essential to select pockets that seems to have the highest potential to be enhanced into public spaces, and to cover a variety of different types of pockets to understand how the interviewees would envision their different utilisation. demonstrates two examples of the decision matrix that was employed to select the pockets for further analysis. The importance factor of each criteria reflected the influence of that criteria to the decision to be included. For example, the pocket size was given an importance factor of 5, because larger spaces allow for more flexible and diverse uses. Existing reappropriation was another significant criterion in the analysis, as it reflected the level of community engagement and the potential for community-driven projects. Pockets that had higher pedestrian activity, more use for social reasons, and more public access. Therefore, this criterion was also given an importance factor of 5 as well.

Table 2. Example of how the decision matrix was used to assess the potential of each pocket for revitalization, based on the observations in .

However, despite the significance of space ownership in determining legal and administrative constraints, particularly for future development endeavours, it appeared that the community’s informal utilization of open spaces, as observed during phase I, was not strongly correlated with ownership. As a result, this criterion was assigned a lower importance factor of 1. Lastly, the potential for expansion was recognized as a vital factor, as it enables greater community engagement and offers enhanced economic opportunities. Pockets that demonstrated potential for expansion were assigned an importance factor of 3 within the decision matrix. Overall, the decision matrix allowed for a systematic and structured analysis of the pockets in Al Wehdat camp, identifying those with the highest potential for revitalization and enhancement as public spaces ().

Accordingly, pockets 1 to 6 were selected for further analysis as they scored the highest against the selection criteria (the selected pockets were numbered in sequential order at the final stage of the research for ease of communication). showcases the location of selected pocket spaces.

3.3. Phase 3: community perspective and semi-structured interviews

This section analyzes semi-structured interviews conducted in Al Wehdat camp. The interviews were designed into three parts. First, the availability and the quality of current outdoor spaces in the camp in general. Second, the inclusivity and the accessibility of the outdoor areas in the camp. The last part was specific to the pocket space in focus. It discusses their current uses, how the interviewees envision their potential, the challenges involved their upgrades, and potential recommendations. Refer to the data sheets for the full interview questions.

The observation of pocket spaces and discussions with market sellers provide interesting insights. One notable finding is the strong commercial viability of Al Wehdat camp, as highlighted by the sellers. This has led to the camp becoming a popular destination for other lower-income groups seeking informal work opportunities. The sellers emphasized the thriving nature of the Al Wehdat market, with people from distant areas coming to shop and a constant influx of new customers. This sheds light on the remarkable transformation of the camp from a place of refuge to an informal commercial centre within the city, despite the ongoing conflict in political administration between the Amman municipality and relief agencies.

However, such strong commercial position of the camp has largely impacted the availability of open spaces in the camp. The interviewees highlighted that the main issue concerning public spaces in the camp, especially in the commercial area, is the high number of informal street stalls or ‘Al Bastat’ which obstructs the accessibility of the space and creates a crowded environment. Participants believed that lack of supervision and security in the camp also poses a challenge to the maintenance of the revitalised spaces. One participant explained

The camp market situation was great until the last 10 years. The shopkeepers are struggling these days. This is due to the Al Bastat issue which is increasing due to the lack of supervision. If they get relocated, at least people could pass.

A merchant who was concerned because of the mobility issue stated that ‘street venders closed the area almost completely. They prevent the customers from entering our shops’. The same mobility issue also impacted the loading spaces. A merchant stated, ‘there is no loading space, all loading of goods happens outside, and we must pay extra money to move it with trollies.’

A clothing shop owner in around pocket 5 proposed an interesting solution to organise the informal sellers:

I think any proposed intervention must benefit the surrounding residents. The economic dimension is crucial here. This empty land adjacent to the road [referring to pocket 5, can be used for Bastat. The area could be divided into zones where people could be assigned to these zones for specific time, etc. Exactly like what Amman Municipality did in Ras Al Ain. Some infrastructure could be improved such as paving, lighting etc which contribute to the aesthetic aspects. In return, a small fee from the Bastat sellers can be charged. I am sure that they [the Al Bastat sellers] will agree once there is a clear organisation. Because the current lack of organisation results in different challenges and problems between the owners related to space and the related tax. Also, when there is an organised market with a diversity of goods, this could result in a higher number of customers using the market.

This proposal to counter the crowdedness of informal sellers in the camp market was done in Ras Al Ein project, which is a nearby neighbourhood that is located between Al Wehdat camp and Amman historic town (about 1.5 Km from the camp). Some parts of it have been recently rehabilitated because of the rapid bus project and the bus station that was built there. Al Bastat sellers have been organised with a plot-rent system. However, there is still a need for protection from vandalism. In this regard, participants suggested that the responsibility for the maintenance of any intervention should be shared between the camp authorities and the shops’ owners. This approach can help ensure that a project is protected and maintained over time, reducing the occurrence of vandalism.

In fact, several participants referred to some existing community-led initiatives to beautify and place-make public spaces in the camp, which was described as successful. They discussed how the role of the community involvement and the young volunteers in sustaining these initiatives was instrumental. One participant explained ‘We do have many young volunteers such as the ‘pioneers’ (Al Mutamaizoon). They upgraded several neighbourhoods (residential streets) in the camp, where they planted and painted the walls. Every neighbourhood that was upgraded the neighbours have been maintained to date’’.

This initiative was also discussed by a member of Amman municipality during an interview, where she shared images of Al Mutamaizoon neighbourhood and the volunteering team working it ( and ). Notably, the presence of Palestinian landmarks art, patterns and symbols were prominent in these small-scale place making interventions. This highlights the strong presence of the Palestinian identity in the camp and reflected the nostalgic emotions toward their country of origin, despite being displaced for more than 70 years.

Figure 7. Al Mutamaizoon team small scale greening and painting dilapidated houses to improve the neighbourhood aesthetics. Images are courtesy of Rania Alkouz.

Figure 8. Al Mutamaizoon team painting Palestinian and Jordanian landmarks. (a) displays the phrase ‘’We will return’’ on a Palestinian landmark. (b) shows Palestinian traditional patterns with the ‘’Palestine’’ written on one of the residence homes. It also shows a painting of a woman wearing a Palestinian traditional dress and carrying a water jug on her head- a common task carried out by women in rural areas of Palestine in the past (c) shows the Roman columns in Jerash, a landmark in Jordan, which symbolise harmony with their host country.

The experience with Al Mutamaizoon team can indicate that the success of public space upgrade projects in refugee camps is contingent not only on meeting the community’s needs but also on preserving their cultural identity. The next sections go into more detail into understanding the current utilisations of different pocket spaces in the camp, the community envisioning of those spaces, and the challenges facing their upgrades.

3.3.1. Pocket 1: The social square in commercial zone

Pocket 1 is within the commercial centre of the camp (northern part). It is currently overtaken by informal stalls which occupies the majority of the space around the fountain ().

During the interviews, individuals residing in pocket 1 expressed their dissatisfaction with the responsible authorities’ indifference, apathy, or disregard for the limited public space within the camp. The interviewees quoted that what they consider is minimal authority supervision of the camp public spaces, which have led to stall sellers to take over the square and to obstruct foot traffic to the existing shops. Moreover, one interviewee highlighted that there is a lack of consideration from the camp authorities towards how people use the limited open spaces in the camps and these minimal open spaces importance. For example, an electric transformer room was installed in the middle of the square near the fountain. This not only raised safety concerns by some residents but also obstructed the already limited public space in the camp. Consequently, the usability of the fountain plaza, which had been in existence since the early 1970s, was severely compromised.

“The fountain used to provide people with water. The owner of the fountain has converted his allocated plot in the camp into shops and he used to paint the fountain two or three times a year to keep the area clean. We [the shop owners around the plaza] now turn it on at the beginning of spring and paint it once a year. There is a corn seller who keeps coming here and he puts chairs around it, where people buy from him and sit to eat around. It is a landmark in the camp. People used to call it the fountain plaza ‘Sahet Al Nafoora’. However, the municipality installed an electrical room in the centre of the plaza near the fountain. It really blocked the area. If it gets reallocated the space can open again like it used to be”.

3.3.2. Pocket 2: empty plot in mixed-use zone

Pocket 2 is located at the north-western part of the camp in a mixed-use area (). The pocket is an NGO (UNRWA) land and is mainly used as a dumpster site, with many informal stalls occupying the access to the site. One participant around pocket 2 discussed how the main challenge facing upgrades of the camp in general is that neither the UNRWA nor Amman Municipality is taking full responsibility for it, while maintenance of the camp is a vague between the two. The participant elaborated ‘This empty land has become a landfill. We discussed this with different officers, but no one did anything. There is a large empty space and a variety of activities around. It has the potential to be developed into a great social hub’. Another participant further explains that “the government does not want to claim any responsibility for the camp as the land is currently UNRWA’s land. Therefore, this reflected on a poor infrastructure.’’

Meanwhile, the plea of a female interviewee residing in front of pocket 2 echoes the profound impact caused by the extreme lack of social and green spaces in the camp, particularly for women, which confined the movement of women within the camp: ‘’the only place to socialise for me is at my neighbours’ houses. There are no other places, especially for women. I wish this area would get turned into a green place. To breathe some fresh air. It would be great to have some greenery and a place to sit in.’’ Moreover, the interviewee highlighted the challenge of street flooding during winter, while in summer, sewage inundates the streets and the surrounding buildings.

Despite these challenges, both interviewees emphasised the potential of pocket space 2 as a social square. The participants believed that the constant presence of community around the mixed-use pocket will create sufficient supervision to maintain any interventions or upgrades.

We [neighbourhood residents] would help each other to preserve it. We always try to make small changes such as cleaning or painting. But once it rains, we wake up to find it muddy. We wish it would be paved and tidy, that way, the residents will take care of it.

Another interviewee emphasized the importance of actively involving people in the work itself as a means to promote a sense of ownership and guarantee the long-term sustainability of these spaces. They pointed to the Mutamaizoon neighbourhood ( and ) as a noteworthy example where residents’ participation has played a significant role in successful improvements and ongoing maintenance initiatives within the camp. Such discussions with residents around pocket 2 offered valuable insights not only into the importance of community participation in maintaining public projects within refugee settlements, placing them within the broader literature of upgrades of informal settlements, but also underscore the necessity of establishing clear lines of responsibility and coordination among the relevant authorities within the camps.

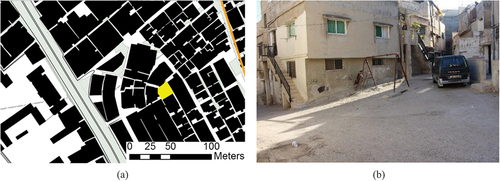

3.3.3. Pocket 3: wide path in mixed-use zone

Pocket 3 is in a residential area surrounding the kindergarten, located in the south-eastern part of the camp (). The pocket serves as a temporary playground for the kindergarten and neighbourhood. A teacher at the kindergarten and a woman living nearby recognized the opportunity to expand upon the existing function of the space as a playground, leveraging its semi-enclosed layout that provides some protection from cars. Such observation is noteworthy as it offers insights on what type of spatial characteristics of pocket spaces are viewed as suitable for playing activities. They suggested implementing regulations for car circulation around the pocket 3 or adding a fence to enhance its functionality and safety as a play area.

Another interesting insight is the suggestion by an interviewee to designate this pocket space as a social area for women. They justified this idea by pointing out the “conservative attitudes” prevailing in the camp towards women’s movement and participation in public spaces. They believed that associating and allocating designated women’s spaces near children’s activities would help counter some of the social and cultural dynamics that can limit women’s mobility and participation.

Furthermore, interviewees around pocket 4 discussed the wider issues facing public spaces in Al Wehdat camp. One interview explained: “We used to have a yard with apples, apricots, almonds, peaches, spinach. But when my brothers grew up, we had to compromise on the land and remove the garden to expand their house and build vertically as well”.

The challenge of continuous expansion of the housing units, even 68 years after the camp’s establishment, is still a threat for whatever remaining public space in the camp. “Some neighbours are still expanding and taking over the open space and leaving children with nowhere to play and socialise.’’ Such statement underscores much deeper challenges facing the camps. It suggests that while small-scale interventions aimed at creating public spaces in camps like Al Wehdat may alleviate some social pressures, they alone are insufficient. It is evident that wider scale systematic strategies on an administrative level are necessary to protect public spaces and provide long-term solutions for housing the camp’s residents. This highlights the need for strategies that address not only the immediate challenges of limited public spaces but also the broader issues of encroachment and sustainable management of the camps. By addressing these underlying factors, a more enduring and effective approach to enhancing the long-term camp’s living conditions can be achieved.

3.3.4. Pocket 4: a temporarily zoned space in a residential area

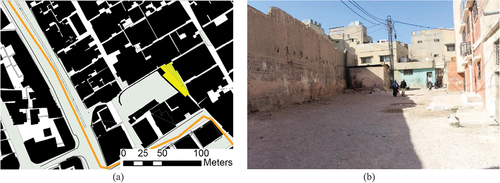

Pocket 4, situated in the north-eastern area of the camps as depicted in , exhibits a layout resembling that of pocket 3. However, unlike pocket 3, pocket 4 is entirely residential. Consequently, this configuration has led to the complete appropriation of the space for private use by the residents of the surrounding buildings. The researchers encountered inquiries from the residents when they entered some of these residential pockets, such as pocket 12 as showcased in . The surrounding residents perceived these spaces as extensions of their own homes and considered the researchers’ presence as intrusion upon private property.

Through interviewing resident women sitting at the doorsteps of their homes around pocket 4, they elaborated on how the space is used for temporary functions such as funerals and weddings. During other times, it is used as a private car park as well as a play area for the children of the surrounding building. One interviewee explained that such openness is not suitable for any kind of public function ‘’it is difficult to convince the people to develop the area as a public space. Everyone around here would say:this is my front porch.’’

A very interesting finding from such statement is the recognition of different zoning and spatial characteristics that enable specific functions within the camp. The presence of residential-only buildings has privatised the use of public space to the residents of the area, which seems to be a social convention accepted within the camp. Unlike in pocket 3, where the presence of the kindergarten invited the use of the space by surrounding neighbourhoods within the camp and permits the expansion of its role as a public space. This finding highlights the need to adapt interventions at different levels for the various types of pocket spaces. The interviewees around pocket 4 suggested that only small-scale greening strategies (without blocking the openness of the space) would be suitable in such space. They also highlighted the role of surrounding community in the preservation of such interventions.

Meanwhile, a notable finding from the discussions around pocket 4 is a suggestion by one interviewee, who brought attention to the potential of abandoned buildings as viable options for developing public (open or closed) spaces within the camp ‘’We can benefit from abandoned buildings as communal spaces and at the same time prevent such buildings [like the one next to pocket 4] from being a dumpster. I think it can reduce some of the negative behaviours that take place throughout the camp” ().

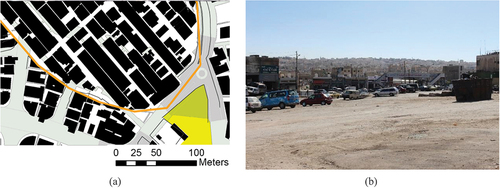

3.3.5. Pocket 5: empty plot in mixed-use zone

Pocket 5 is located at the southern edge of Al Wehdat camp and is owned by Amman municipality. It is currently used as a public car park and a dumpster site (). A member of Amman municipality council, along with several interviewees, identified pocket 5 as having the highest potential for park/public spaces development due to its relatively large size. Moreover, its ownership by the Amman Municipality also makes it free for public use.

The findings from the interviews with shop owners and residents adjacent to the site point to a pressing need for the development of the area due to health and safety concerns. One interviewee emphasized the negative impact of the current state of the space on the surrounding community:

The space is harming us [shop owners/residents]. They [Amman municipality] gather waste here and burn it, and the smell is awful. It keeps releasing smoke and bad fumes all day. Second, it attracts young gangsters who keep getting into fights … The degradation of this open area attracts all sorts of crimes.

3.3.6. Pocket 6: wide path in a mixed-use area

Pocket 6, situated in the western part of the camp, serves multiple functions within the community. Currently, it functions as a temporary playground for children, a pedestrian path connecting residential areas to the market, and a sitting area at the doorsteps (Atabat) by the residents of the surrounding buildings ().

A key insight emerged from the interview with a refugee woman, who has been living in the area near pocket 6 since her birth in the 1962. She believes it is critical to provide a park or playground exclusively designated for women and children within the camp. Her words shed light on the significant challenges faced by women who lack the means to venture outside the camp’s confines. The interviewee’s personal experience vividly highlighted the limitations she and others face in providing opportunities for their children beyond the camp’s boundaries.

‘’Women really need a place to go with their children. Most people can’t [do not have the means] to go anywhere outside the camp. Take me for example, I have young granddaughters that I cannot take anywhere. I wish there was a park I could take them to … I have not left the house in 5 months [except to the grocery shop where she works with her son, which is next to the house]’’.

Such encounter, among other voices, highlights the importance of research focusing on the experiences of long-term refugees, which can play a crucial role in giving voice to their realities and combating the marginalization and invisibility often faced by refugee communities. It can hopefully contribute to fostering a greater understanding and empathy among policymakers, practitioners, and the wider public.

The interviewees around pocket 5 shared a similar perspective to those around pocket 6 regarding its suitability as a playground or small park. The larger size of pocket 6, coupled with its location in a mixed-use zone, makes it a bustling thoroughfare linking different parts of the camp, resulting in constant foot traffic. These factors seem to have deterred private claims on the space by surrounding residents, distinguishing it from spaces like pocket 4. Despite all these pocket spaces technically being ‘public’ as they fall outside the 100 m2 plot allocated to each refugee family the camp’s social dynamics have established varying patterns of space usability. Some pockets are claimed for private use by surrounding inhabitants, while others remain designated as public property.

4. Discussion and conclusions

This research set out to explore and evaluate public pocket spaces in Al Wehdat Refugee Camp in Jordan, with a focus on mapping and envisioning scenarios for their upgrades. The study aimed to answer three key questions: 1) What are the different types of pocket spaces in the camp? 2) How does the community envision their potential uses as public spaces? 3) What are the specific challenges and opportunities when implementing pocket spaces upgrades in Al Wehdat camp, and what potential recommendations can address these challenges?

The need for such research stems from the evidence that small-scale improvements in public spaces have been highlighted by several researchers to be positively associated with socio-economic improvements within informal and degraded urban areas in general (Enia and Martella Citation2020; Girard, Nocca, and Gravagnuolo Citation2019; Jano, Teqja, and Hasa Citation2020; Sakay, Sanoni, and DEng Citation2011). Meanwhile, other researchers have discussed the need for public space provision within the limited and challenging urban conditions of refugee camps specifically, which can contribute to contribute to enhancing the overall living conditions and empowerment of the camp residents (Hilal Citationn.d.; Dalal et al. Citation2018).

This research addressed the first question through identifying various types of pocket spaces within Al Wehdat camp. These included pockets in commercial areas (squares and streets intersections), in mixed use areas (wide paths and empty plots/land), and in residential areas (temporarily zoned pockets and courtyard spaces). Each of these pockets presented unique opportunities for the creation of public and green areas in the camps, where the findings from the analysis provided valuable insights into the informal appropriation of these spaces by the long-term refugees,

Through interviews with refugees residing near various types of pocket spaces, a significant concept emerged from the exploration of the second research question: the ‘informal privatisation of public space’ within the camp. The findings revealed that despite these leftover spaces being technically public spaces (outside the 100 m^2 plots for every family), pocket spaces that are in residential-only areas seem to be informally claimed for private use by surrounding residents. The size of the pocket may also play a role, as larger pockets tend to remain open for broader community use, extending beyond the residents of surrounding buildings. The informal privatisation of public spaces highlights the complex dynamics of space utilization within the camp, where social conventions and informal agreements shape the perceived ownership and control of public spaces. Despite lacking legal ownership of their homes, the refugees in the camps have established an informal housing market within their community. They engage in informal trade, exchange, and rental activities involving their housing units. The findings of this research suggest that this informal ownership extends beyond the housing units to encompass the public spaces within the camp. Furthermore, this informal ownership appears to be socially recognized and acknowledged, as evidenced by the discussions held regarding pocket 4 during the study.

These observations highlight the nuanced dynamics of public space utilization within the camp and suggest the importance of considering location and scale when implementing interventions aimed at enhancing these spaces.

In addition, the discussions with refugees brought attention to the issue of public space accessibility for women. Interviewees stressed the significance of establishing dedicated protected and public spaces that are specifically designed to address the social restrictions faced by women. These spaces would provide opportunities for women to engage in activities, socialize, and access resources in a safe and inclusive environment, thereby countering the limitations imposed on them within the camp.

Building upon the responses obtained from the interviews conducted in the selected six pockets, presents a comprehensive overview of the primary challenges encountered in revitalizing each pocket (third research question). It also highlights the corresponding opportunities and suggested solutions identified by the interviewees. Furthermore, the table includes recommendations for maintaining any intervention provided by the interviewees.

Table 3. Summary of the community perspective on the opportunities and challenges facing the revitalization of pocket public spaces in Al Wehdat refugee camp.

One of the main findings of this study is that the interviewees, including a member of Amman municipality, emphasised that the primary challenge facing camp upgrades is not solely the limited space, although it remains a significant factor. Rather, the interviewees asserted that the main challenge facing any upgrades is the conflicting dual management structure between the UNRWA and the local municipality of Amman, where there is lack of clear lines of management and delegation of responsibility between the two authorities. This administrative divide has left the camp in a state of limbo, making it difficult to move forward with any meaningful upgrades or improvements. It is essential to address this challenge and find a way to bridge the gap between the UNRWA and Amman municipality to ensure that the camp is not left behind in any future development plans for the area.

Another main finding of this study is the economic capability and value that the camp marketplace represents, not just for the camp residents but also for the surrounding areas. Pocket spaces within commercial and mixed-use areas in the camp also seemed to be of higher significance for social and commercial activity, extending beyond being the outdoor space of residents of adjacent houses. Hence, it is recommended that strategies be devised to capitalise on these bustling pocket spaces to amplify economic opportunities and foster community cohesion. The opportunities these pockets provide for commercial viability and activating this network of pockets can promote urban vitality, as supported by literature (Enia and Martella Citation2020; Girard, Nocca, and Gravagnuolo Citation2019; Jano, Teqja, and Hasa Citation2020; Sakay, Sanoni, and DEng Citation2011). Specifically, initiatives should focus on formalizing and enhancing the infrastructure of these areas to better support local businesses and entrepreneurs. This may involve establishing designated zones for commercial activities, improving accessibility and amenities, and providing resources for business development and marketing. Additionally, fostering collaboration between the camp community, local authorities, and external stakeholders can facilitate the implementation of sustainable economic initiatives. On the other hand, the refugees participating in the discussion emphasised the importance of community involvement in maintaining public space upgrades, particularly in smaller pocket spaces within the camp. This aligns with existing literature on community involvement in urban informal settlements (Dalal et al. Citation2018; Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016; Stevenson and Sutton Citation2012), placing the research on refugee settlements within the broader context of informal settlements. Additionally, in long-term refugee camps, heritage preservation gains additional significance, which may not be as prominent in other informal settlement upgrades. Successful community-led place-making initiatives, like the Al Mutamaizoon neighbourhood, exemplify a high level of sensitivity towards the Palestinian heritage of long-term refugees. These initiatives honour their cultural identity and foster a strong sense of belonging.

However, the interviewees also pointed out that even with the strong social connectivity and its contribution to the camp maintenance and supervision, there is still a need for external authorities and the maintenance of any larger open public spaces in specific. While Jordan maintains a relatively high level of security compared to the region, the concept of security in this context refers to the perceived safety within the specific urban environment of each pocket from theft, recreational drug use/selling, and vandalism. This, according to the interviews, stems from lack of overall supervision from authorities. Such concerns were provided around pockets 1, 3 and 5, especially around nighttime.

This further emphasises the need for stronger integration of the camp within the surrounding urban area at an administrative level.

The findings of this paper indicate that while small-scale interventions focused on establishing public spaces within camps like Al Wehdat can provide some relief for the high-density environment, comprehensive, systematic strategies at the administrative level are necessary to safeguard public spaces and offer sustainable long-term housing solutions. These strategies must address both the immediate challenges of limited public spaces and the broader concerns of encroachment and sustainable management within the camps. By addressing these underlying factors, a more effective and sustainable approach to improving long-term living conditions can be achieved.

Moreover, although this study specifically pertains to Al Wehdat camp, its implications extend to other long-term refugee camps. The insights gained regarding the importance of comprehensive, systematic administrative strategies, the challenges of limited public spaces, and the need for sustainable management are applicable in similar settings. This research contributes to the broader literature on upgrading informal settlements by emphasising the significance of addressing both immediate and underlying challenges to bring about lasting improvements in the living conditions of displaced populations. By considering these factors and implementing tailored strategies, it is possible to enhance the long-term viability and quality of life within refugee camps beyond the specific context of Al Wehdat.

Access instructions

To access the appendices containing the data supporting this study, please refer to the supplementary materials provided with this article. For any inquiries or requests related to the data, please contact the corresponding author at [email protected].

Ethical considerations

This research was conducted following ethical guidelines, and all participants provided informed consent for data collection and publication. Any personally identifiable information has been anonymized to protect participants’ privacy.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.9 KB)Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2024.2372488

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within this article as supplementary appendices. These appendices provide detailed information on the following:

Appendix A – Pocket Selection (Decision Matrix): This appendix presents the detailed decision matrix used to evaluate and select pockets for analysis. It includes criteria, scoring, and comments for each pocket, providing transparency into the pocket selection process.

Appendix B – Samples of Thematic Analysis: This appendix offers a selection of thematic analysis samples, including verbatim excerpts from interviews or textual data. These samples illustrate the emergence of key themes and support the qualitative findings discussed in the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ababsa, M. 2010 July. “The Evolution of Upgrading Policies in Amman.” Sustainable Architecture and Urban Development. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00467593/

- Abu-Dayyeh, A. N. I. 2004. “Persisting vision: plans for a modern Arab capital, Amman, 1955–2002.” Planning Perspectives 19 (1): 79–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/0266543042000177922.

- Alnsour, J. A. 2016. “Managing Urban Growth in the City of Amman, Jordan.” Cities 50: 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.08.011.

- Alnsour, J., and J. Meaton. 2014. “Housing Conditions in Palestinian Refugee Camps, Jordan.” Cities 36:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.10.002.

- Alshoubaki, H., and L. Zazzara. 2020. “The Fragility in the Land of Refugees: Jordan and Irrepressible Phenomenon of Refugee Camps.” Journal of International Studies 13 (1): 123–142. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2020/13-1/8.

- Atallah, D. G., E. R. Shapiro, N. Al-Azraq, Y. Qaisi, and K. L. Suyemoto. 2018. “Decolonizing Qualitative Research Through Transformative Community Engagement: Critical Investigation of Resilience with Palestinian Refugees in the West Bank.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 15 (4): 489–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1416805.

- Dalal, A., A. Darweesh, P. Misselwitz, and A. Steigemann. 2018. “Planning the Ideal Refugee Camp? A Critical Interrogation of Recent Planning Innovations in Jordan and Germany.” Urban Planning 3 (4): 64–78. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i4.1726.

- Dovey, K., M. van Oostrum, I. Chatterjee, and T. Shafique. 2020. “Towards a Morphogenesis of Informal Settlements.” Habitat International 104: 102240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102240.

- Enia, M., and F. Martella. 2020. “Architecture Beyond Permanence: Temporariness in 21 St Century Urban Architecture.” EAAE – ARCC International Conference, Valencia.

- Flinders, M., M. Wood, and M. Cunningham. 2016. “The Politics of Co-Production: Risks, Limits and Pollution.” Evidence & Policy 12 (2): 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14412037949967.

- Girard, L. F., F. Nocca, and A. Gravagnuolo. 2019. “Matera: City of Nature, City of Culture, City of Regeneration. Towards a Landscape-Based and Culture-Based Urban Circular Economy.” Aestimum: 5–42. https://doi.org/10.13128/aestim-7007.

- Guetterman, T. 2015. “Descriptions of Sampling Practices within Five Approaches to Qualitative Research in Education and the Health Sciences.”

- Hart, J., N. Paszkiewicz, and D. Albadra. 2018. “Shelter as Home?: Syrian Homemaking in Jordanian Refugee Camps.” Human Organization 77 (4): 371–380. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259.77.4.371.

- Hilal, S. n.d. “Campus in Camps » Gender and Public Spaces.” https://www.campusincamps.ps/projects/gender-and-public-spaces/.

- Jano, S., Z. Teqja, and E. Hasa. 2020. “Urban Pockets Design: Reclaiming Third Landscape Through Participatory Processes and Game Theory.” Agricultural University of Tirana 19 (4): 47–54.

- Kamalipour, H., and K. Dovey. 2020. “Incremental Production of Urban Space: A Typology of Informal Design.” Habitat International 98: 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102133.

- Khawaldah, H. A. 2016. “A Prediction of Future Land Use/Land Cover in Amman Area Using GIS-Based Markov Model and Remote Sensing.” Journal of Geographic Information System 8 (3): 412–427. https://doi.org/10.4236/jgis.2016.83035.

- Lastra, A., and D. Pojani. 2018. “‘Urban Acupuncture ‘To Alleviate Stress in Informal Settlements in Mexico.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (5): 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1429902.

- Mahamid, F. A. 2020. “Collective Trauma, Quality of Life and Resilience in Narratives of Third Generation Palestinian Refugee Children.” Child Indicators Research 13 (6): 2181–2204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09739-3.

- Maqusi, S. 2017. “‘Space of refuge’: Negotiating Space with Refugees Inside the Palestinian Camp.” Humanities 6 (3): 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/h6030060.

- Oesch, L. 2017. “The Refugee Camp as a Space of Multiple Ambiguities and Subjectivities.” Political Geography 60: 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.05.004.

- Rao-Cavale, K. 2017. “Patrick Geddes in India: Anti-Colonial Nationalism and the Historical Time of ‘Cities in Evolution’.” Landscape and Urban Planning 166: 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.11.005.

- Sakay, C., P. Sanoni, and T. H. DEng. 2011. “Rural to Urban Squatter Settlements: The Micro Model of Generational Self-Help Housing in Lima-Peru.” Procedia Engineering 21: 473–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2040.

- Stevenson, A., and R. Sutton. 2012. “There’s No Place Like a Refugee Camp? Urban Planning and Participation in the Camp Context.” Refuge 28 (1): 137–148. https://doi.org/10.25071/1920-7336.36097.

- UNHCR. 2024. “Forcibly Displaced and Stateless Population Categories | UNHCR.” https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/insights/explainers/forcibly-displaced-pocs.html#:~:text=The%20total%20population%20that%20UNHCR%20protects%20and%2For%20assists%20(110.8,who%20are%20stateless%20(most%20of.

- UNRWA. 2020. “Where We Work | UNRWA.” https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/jordan.

- Venerandi, A., M. Iovene, and G. Fusco. 2021. “Exploring the Similarities Between Informal and Medieval Settlements: A Methodology and an Application.” Cities 115: 103211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103211.

- Watson, D., A. Plattus, R. G. Shibley, and D. Watson. 2003. Time-Saver Standards for Urban Design. New York: McGraw-Hill. https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/titel/1767554https://www.amazon.co.uk/Time-Saver-Standards-Design-Donald-Watson/dp/007068507X.

- Xu, Y., and C. Maitland. 2019. “Participatory Data Collection and Management in Low-Resource Contexts: A Field Trial with Urban Refugees.” Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287098.3287104.