ABSTRACT

Background

The patient experience is associated with patient satisfaction and health outcomes, presenting a key challenge in healthcare. The objective of the study was to explore the principles of care in and beyond healthcare, namely in a three Michelin-starred restaurant, and consider what, if any, principles of care from the diners’ experience could be transferrable to healthcare.

Method

The principles of care were first explored as part of observational fieldwork in a healthcare day surgery unit and the restaurant respectively, focusing on communication between the professionals and the patients or the diners. Care was subsequently explored in a series of public engagement events across the UK. The events used immersive simulation to recreate the healthcare and the dining experiences for the general public, and to stimulate discussion.

Results

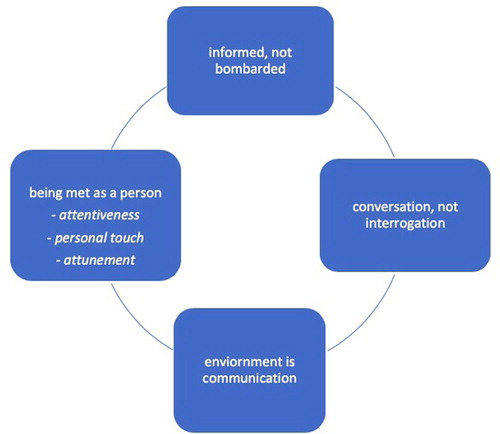

A thematic analysis of the engagement discussions identified overarching themes in how care was experienced in and through communication; ‘informed, not bombarded’, ‘conversation, not interrogation’, ‘environment is communication’, and ‘being met as a person’. The themes suggested how the participants in simulation felt about the care they received in real time and provided recommendations for improved clinical practice.

Conclusions

While practice improvements in healthcare are challenging, the patient experience could be enhanced by learning relational aspects of care from other sectors, including the high-end restaurant industry that focuses on meeting persons’ needs. Simulation provides a new kind of opportunity to bring professionals and patients together for focused discussions, prompted by immersive experiences of care and communication.

Introduction

Improving the patient experience presents a challenge for healthcare providers worldwide [Citation1]. In the United Kingdom, numerous reports place the patient experience at the centre of its National Health Service (NHS), calling on healthcare professionals to treat patients with compassion, dignity and respect [Citation2,Citation3]. The patient experience framework [Citation4] outlines improvement needs in leadership, organizational culture, and compassionate care. To date, research reports have chiefly drawn on surveys and feedback tools (e.g. The Friends and Family Test) to assess the patient experience [Citation1,Citation5]. However, a fuller understanding of the real time experience requires attention to what care means to patients, and how care feels when it happens. Victor Montori [Citation6] writes about the ‘accidents of care’ (p. 16), those seemingly insignificant gestures of human to human connection that can have a major impact on a patient’s experience, such as a healthcare professional stopping and giving time to a waiting patient out of kindness and compassion. When we better understand such gestures from the frontline professionals and how they match with what patients need, further improvements could be designed and implemented.

In the report What Matters to Patients [Citation7], patients have emphasized the importance of relational aspects of care: that healthcare professionals listen, provide emotional support, and approach their patients as ‘persons, not numbers’. The moments of waiting to be seen are an important part of patient experience yet their significance can be easily overlooked. A recent study in an elective surgery unit showed how those patients who had their operations later in the day (thereby experiencing longer waiting and prolonged fasting) rated their experience negatively, including poorer communication with healthcare professionals, compared to those who had their operation by midday [Citation8]. This begs the question what could be done to make the waiting experience more pleasant, and what kinds of communication practices matter to patients.

Research suggests that improving humane communication is paramount for the patient experience. Person-centred practices of high quality care embody dignity and respect for patients [Citation9]. Nonverbal communication, such as smiling and eye contact, helps patients feel acknowledged as persons rather than as case numbers, and verbal practices, such as providing reassurance, updating on progress and delays, and explaining results and outcomes in ‘plain language’ can alleviate the anxieties of patients [Citation10]. For example, patients waiting for a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan often experience fear, claustrophobia, and anxiety when anticipating such a lengthy and spatially constrictive examination. However, when radiologists, nurses, and technologists communicate in a patient-centred manner, the patients become more relaxed and co-operative with the process [Citation11]. Because the patient experience is linked with how satisfied patients are with their care and how patients feel their needs have been met, it can have wider consequences, including how motivated patients are to take personal responsibility for their health. Evidence shows that whether or not patients adhere to medication or blood pressure control is related to their communication with healthcare professionals, namely how doctors have responded to patients’ personal beliefs and concerns [Citation12]. When communication meets patients’ needs on an emotional level, it can help patients to work on staying healthy, pointing to safer healthcare.

Despite the efforts of healthcare services to capture patient feedback, many patients feel inhibited to speak up when their experiences have been negative [Citation13]. A better understanding of real time communication could indicate where the standards fail. It might not be clear to the frontline healthcare providers what it means for patients to ‘be treated as a person’ or ‘be listened to’ in fleeting moments where clinical effectiveness is paramount [Citation6]. In examining how compassion, dignity, and respect are communicated in the midst of clinical realities, it can be helpful to pay closer attention to care delivered in other sectors, including the high-end restaurant industry. Our prior collaboration with Heston Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck restaurant has disclosed unexpected parallels between the work in the operating theatre and the kitchen of this three Michelin-starred restaurant [Citation14]. It became evident that excellent food from the kitchen is not enough to ensure an outstanding dining experience. Rather, each diner’s experience at the table must be designed and managed by the front-of-house staff to ensure success, inviting comparison with patients’ experiences in pre-surgical settings. If the customer experience in restaurants involves much more than the food served, and the patient experience extends beyond medical procedures, we must explore those aspects of care beyond the food or medical care, turning the lens on the nuances of communication.

However, healthcare and hospitality sectors might not be directly comparable. Firstly, there are a number of differences in terms of the organizational complexities of a hospital and a restaurant, the number of people interacting with a patient in the care process compared to a diner in a restaurant, the heightened awareness of safety issues in healthcare, and the fact that patients are in a charged emotional state. Put simply, going to a restaurant is usually perceived as a pleasurable experience whereas going to hospital is not. Secondly, the customer experience in the restaurant industry is linked with business and revenue: when people get great service, they are likely to return. But as one London trauma surgeon put it, ‘I’m not really motivated to keep having my patients coming back’. What she means is that the ultimate goal for doctors is for their patients to go home rather than return to hospital. Yet at the heart of both experiences is care, and there is an important link between the patient experience and the cost of care in terms of health outcomes [Citation15]. How patients experience direct contact with healthcare professionals can have broad economic implications when additional costs to healthcare institutions from treating poor outcomes are taken into account.

Thirdly, implementing lessons from other industries to healthcare can be easier said than done. There is extensive literature on staff engagement, satisfaction and improvement that suggests healthcare professionals often feel they are not able to deliver high quality care, and that the barriers to improving care are multiple (e.g. [Citation16–19]). There is also a high prevalence of occupational stress and burnout in the nursing profession [Citation20–22], and as Dawson [Citation23] notes, when staff are under pressure and feel unsupported by their organization, ‘patients clearly notice and have a less satisfactory experience’ (p. 18). Patients receiving care in deprived neighbourhoods report the worst quality of care, including longer waits and less satisfactory interactions with staff [Citation24]. Health inequalities arising from the regions lived in, ethnicity, and socio-economic status have further implications to the needs and the experiences of service users [Citation25,Citation26].

The patient experience literature also suggests difficulties in translating knowledge of what needs to be improved into improvements in practice. Quality improvements are often met with resistance when healthcare staff are reluctant to admit that problems exist and feel that new solutions take time and resources from their clinical work [Citation27]. For instance, the frequent comparison of healthcare with the aviation industry has caused new concerns for patient safety initiatives. While the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist is a prime example of a quality improvement strategy drawn from aviation, the checklist is used inconsistently in operating rooms around the world [Citation28–30]. In aviation, improvements are never an issue contested when a single problem can lead to a catastrophe on a grand scale, yet there is scope to learn from other industries [Citation31]. When staff’s wellbeing and a cultural focus are prioritized, ‘service excellence training’ with hospitality companies such as Ritz-Carlton, Four Seasons, and Disney have seen healthcare systems improve and achieve their goals [Citation32].

While learning from other sectors can be less than straightforward in healthcare, we aim to show that there can be scope for transferability from the restaurant industry in the relational aspects of compassionate care (e.g. [Citation4]). After all, the nuances of communication or the ‘accidents of care’ [Citation6] are not inherently sector-specific but part of human to human interaction. When we better understand their importance in the patient experience, we can begin to consider their transferability with training. In this study, we examined what relational aspects of care could be transferred from the customer-focused dining experience to healthcare. To address the question, we used a novel approach combining field observations, immersive simulation, and public engagement discussions to focus on two sites where care is experienced directly: restaurants and hospitals. The emerging field of engagement and simulation science encourages deeper and focused discussions that are prompted by realistic and immersive real-time experiences [Citation33]. Using engagement and simulation, this article zoomed in on the relational moments of care as people arrived at the simulated sites and waited for their food or operation. Unpacking the differences and similarities between dining and clinical care, and asking what participants liked or disliked in the simulated environments, the article generated recommendations for improving the patient experience.

Methods and procedure

Ethics

The project, ‘Let Me Take Care of You’: How Dining and Surgery Can Improve Care and Illuminate Each Other’s Practices, received approval from the Ethics Board of the University of Greenwich on 3rd November 2017 (Project ref: UREC/17.1.5.12) and from the UK Health Research Authority on 14th February 2018 (IRAS project ID: 240865), the site-specific NHS Foundation Trust, and the restaurant management. Each staff member in the hospital or the restaurant who were observed gave consent individually on the day of the fieldwork. Engagement participants provided consent on the day of the engagement activity.

Two sites of field observation

The lead researcher, a social interaction specialist, spent time immersed in the worlds of the restaurant’s and hospital’s front-of-house, to build an ‘insider’ understanding and to document practices of care. The two sites selected were a high-end restaurant and an NHS day surgery unit as described in .

Table 1. Two sites of field observation.

Engagement through simulation

The ‘Let Me Take Care of You’ – project centred on engagement through simulation. The aim was to enable the general public to experience a recreation of care in the dining and healthcare sectors, then discuss these experiences. Whether as diners or patients, the general public seldom have opportunities to engage with other people about their experiences. Even less often do they have opportunities to engage in a ‘detached’ way that combines recollections of past encounters with personal experience in the present. A challenge is to separate a lived experience (e.g. eating an actual meal or experiencing care when a person is unwell) from thoughts and reflections upon the processes involved. Engagement through simulation offers a novel means of sharing experience through enactment with patients, publics and professionals within healthcare, building on an extensive body of work by the Imperial College Centre for Engagement and Simulation Science (ICCESS) [Citation34–39].

Four engagement events took place across the UK, aiming to gain a broad spread of geographical perspectives and immerse the general public in the lived experience of care through simulation. A total of 75 participants, aged 18 or over, took part in these free events followed by a group discussion. Because of space and design constraints, each scenario (see below) could host 16 participants at a time. An open invitation was issued and advertised through social media and the participating venues: Infirmary Medical Museum (Worcester), Glasgow Science Centre (Glasgow), Chelsea & Westminster Hospital (London), Royal College of Nursing (London).

Simulation scenarios

Bespoke simulations were designed on the basis of the field observations at the day surgery unit and the restaurant ( and ). While physically simple (recreating four restaurant tables, a hospital waiting area and a DSU), the simulations were conceptually sophisticated. Once identified and abstracted, the key instances of care were represented to members of the general public through simulation, inviting participants to immerse themselves and feel the care, to monitor their reactions and emotions, and to discuss these experiences as a group. Restaurant staff and clinicians ‘played’ their own unscripted roles to ensure authenticity, while members of the public (‘participants’ below) immersed themselves first as ‘patients’ and then as ‘diners’. Each participant was allocated an identity invented by the researchers so that the participants did not disclose personal information. The invented identity was handed out on a piece of paper stating a name, a date of birth, and possible allergies (e.g. penicillin, latex, dairy, gluten). No food (water only) was served in the restaurant scenario, and no surgical operations or procedures were performed in the clinical scenario. Both scenarios (see ) played until the point where a food order had been taken or a patient had been consented to an operation (each simulation lasted around 10–15 mins depending on participant numbers).

Table 2. Two simulation scenarios (clinical and restaurant scenarios).

Engagement discussion

After the two scenarios, participants were invited to discuss their experiences (). The dialogue took place at multiple levels: (1) professional to professional (nurses and surgeons with front-of-house staff and chefs); (2) recipient to recipient (patients with diners); (3) professional to recipient (patients with clinicians, diners with restaurant staff, patients with restaurant staff and diners with clinicians). While the dialogue was allowed to emerge organically, the following prompts were used to guide the discussions: (1) How did you feel about the simulation experience? (exploring the initial reactions to the simulation); (2) What did you like or dislike in the care you experienced?; (3) What aspects could be transferred to healthcare to improve the patient experience? (developing recommendations). The discussions lasted around 30 min. The researchers transcribed the discussions for thematic analysis.

Data analysis

The discussions and reflection notes were used for thematic analysis, a qualitative approach that uncovers commonalities within a data set. Thematic analysis seeks to identify, sort, and develop insight into patterns of meaning or themes – according to Braun and Clarke [Citation40] to ‘see and make sense of collective or shared meanings and experiences’ (p. 57). These questions sought to illuminate the concept of the patient experience in terms of what the general public wants and needs in their care, and what care means for them. As Braun and Clarke suggest, thematic analysis can be used flexibly to report ‘the obvious or semantic meanings’ or ‘the latent meanings, the assumptions and ideas that lie behind what is explicitly stated (p. 58)’. Our analysis includes elements of both. The analysis proceeded through the initial familiarization with the data set, followed by an inductive coding of the transcripts. The development and refinement of themes related to the practices and nuances of communication continued as the broader understanding of the principles of care evolved. The themes identified were emergent from the data as well as influenced by the research observations in the two sites. Data saturation was reached when participants’ responses no longer yielded new information within the parameters of the three discussion prompts and the private reflection notes. A thematic map [Citation41] was produced to illustrate an understanding between the themes and the subthemes in what constitutes an experience of care.

Results

The analysis centred on the experience of care, exploring what the emerging themes imply for improving patient experience. The core themes were: ‘informed, not bombarded’, ‘conversation, not interrogation’, ‘environment is communication’, and ‘being met as a person’ (see ). Each theme considered how communication made patients or diners feel while being cared for by the frontline staff. We also considered the assumptions underpinning these themes and what, if anything, could be transferable between the restaurant and healthcare to improve the patient experience.

Informed, not bombarded

We start our description with the clinical experience. An important theme emerged about how information was conveyed to patients in the day surgery unit (see Appendix). Participants overwhelmingly felt that the welcome speech bombarded patients with information that was too much to take in prior to surgery.

Too much information to take in and makes you feel nervous as if you didn’t hear everything. You couldn’t ask again as you had already been told. (Participant in Glasgow)

There was a list of information that I couldn’t remember. There was a lot of terminology and job titles that I didn’t understand. (Participant in London)

Their mention of the helicopter, it’s just making us aware that there could be a delay and that we should expect to be cared for. (Participant in London)

We are culturally conditioned to know the rules of the restaurant but clinically we don’t know how to behave and what would happen next. Am I sat in the right place? Am I doing this right? (Participant in London)

Nurses are not checking people’s first language and would they be able to understand the welcome speech. (Participant in Worcester)

The waiter stepped back slightly to give you time to relax. (Participant in Worcester)

You had time to think in the restaurant and time to make decisions. (Participant in Worcester)

In the restaurant, a waiter was immediately assigned to me. Individual care will be better than group care for the human touch (Participant in London)

The waiter knew a lot about the menu which made me feel incredibly safe. (Participant in London)

The welcome speech would be less confusing if it was provided before you turned up and then announced so that you know what to expect and can tune in. (Participant in London)

A booklet of charts and pictures would be helpful, a menu of what was happening. (Participant in Worcester)

Conversation, not interrogation

Many participants felt that their communication with the healthcare professionals was asymmetrical. Clinicians asked most of the questions, leaving little room for patients to express their concerns. Some questioning lacked emotional understanding of patients’ anxieties about the forthcoming surgery, resembling an interrogation rather than a two-way conversation.

I was fired with questions and had not much time to ask and to think about things. For example, why would I have to take my contact lenses out? (Participant in Worcester)

The nurse changed my answer and kept asking questions like a machine. (Participant in Worcester)

Repetitive questions! I was asked about asthma twice. Could clinicians communicate better to save repetition? (Participant in Worcester)

If you have a gluten intolerance they remember it in the restaurant. Whereas in the hospital you got asked by different people all the time. I would prefer one person to know. (Participant in London)

If you ask my date of birth all the time I feel you are not taking in my information. (Participant in Worcester)

I want to feel that the professional knows this information already and not rely so much on the individual who may feel overwhelmed. They should have a system in place for this. (Participant in Glasgow)

There is often rotation between professionals. A nurse will undertake pre-operative checks, followed by an anaesthetist and a surgeon. Patients sit waiting in their bays and healthcare professionals follow a list when they see each patient. During this rotation clinicians frequently repeated one question: ‘Have you been seen by X (a nurse/a doctor/an anaesthetist)?’ Many participants felt this seemingly simple question was difficult to answer because they could not distinguish the professional roles or grasp who is who, especially if professionals have not introduced themselves clearly. This made some patients feel confused and uncomfortable.

‘Have you been seen’ was asked all the time. If they knew that it would save some time, if they had a system in place. (Participant in Glasgow)

It’s difficult to know who is who and what you can ask. There are many different colours and types of uniforms, which is confusing. A lanyard that says ‘surgeon’ or ‘anaesthetist’ would help, because in a restaurant you know who the matriarch is or who the waiter is. (Participant in Worcester)

Difficult, because a waiter is assigned to you whereas in the clinical setting you don’t have your own nurse. (Participant in Glasgow)

You are responsible for the care as you have to know if you’ve been seen by a doctor or a nurse or someone else. (Participant in Glasgow)

Good waiters and nurses were attentive, but in clinical care you are waiting for them rather than them waiting for you. (Participant in London)

I got answers when I asked specific questions, but it didn’t feel like a conversation. (Participant in Worcester)

The conversation was more about giving the healthcare professionals what they needed rather than what I needed and the question regarding the next of kin made me feel like I was going to die. (Participant in London)

If I have an allergy and go to a restaurant, the only person I tell about my allergy is the waiter. Can I be sure that they relay the information to the kitchen? Repetition can be reassuring. (Participant in Glasgow)

The anaesthetist said, ‘Sounds like we are asking a million questions … ’ which showed empathy with all the questioning. (Participant in Worcester)

Environment is communication

Though communication is integral to an experience of care, this is not only about information transfer. The environment and ambience convey either calmness or tension to participants.

You get an immediate sense of the environment, is it calm or is it electric. (Participant in Worcester)

In the dining area there was this ambience of the music. But in the clinic it was tense due to the scary details, so could we have music to calm the environment? (Participant in London)

Healthcare could learn to create a sense of ambience that the restaurant has. As the environment can impact on the patient. (Participant in London)

I found the waiting room quite oppressive in a sense of personal space which is very much like an NHS waiting room. (Participant in London)

If a waiter is stressed, I don’t want to know about their stress. (Participant in London)

Clinical setting feels rushed, you feel you don’t have time to ask questions. You know they are so busy already and don’t want to ask them. (Participant in Glasgow)

Restaurants can be super busy but they can manage it in a calm way so that it all works smoothly. (Participant in Worcester)

Being met as a person

Being treated as a human being, not simply as a table or a medical file, is at the core of the final theme, being met as a person. This involves intertwined dimensions of attentiveness, personal touch, and attunement.

Attentiveness

Attentiveness, and how it was conveyed verbally and nonverbally, was critical. This involved eye contact and smiling, as well as acknowledging people as they arrived.

In a restaurant they come to you, they are warm and welcoming. (Participant in Worcester)

I do like it when people smile in a positive way and there is eye contact, and I think people should be alert to the person they are receiving in their care. (Participant in London)

In the clinical setting, communication was lacking in eye contact, especially from the nurse who didn’t look at me. In the hospital you were reassured and it was nice, but in the restaurant simulation the staff were very welcoming and smiling and their body language was very welcoming. (Participant in London)

The essence for me is for people to be fully present and giving me eye contact. It is like mindfulness and this is what is transferrable to me. (Participant in London)

Personal touch

It is important that people feel welcomed whether in a restaurant or a hospital. Attentiveness combined with a personal touch can make people feel that they matter and have come to the right place. A simple step, such as front-of-house staff greeting diners by name, makes a big difference. Some participants highlighted reception as the important first impression of a public establishment that colours the entire experience.

That staff knowing your name can make people feel they are being treated as a person. (Participant in London)

From receptionists down to the nurses I am already drawing conclusions about the whole place. (Participant in London)

So I was allergic to fish. In the day surgery centre they asked if I was allergic to anything, whereas in the restaurant they knew I was allergic to fish. I didn’t feel as cared for in the clinic. (Participant in London)

What made a real difference in the clinical setting for me was a little comment put on my notes – a fact about me which gave a discussion point with all staff. So a fact on my notes made it very personalised. Simple and cheap! (Participant in London)

Handshake by the anaesthesia doctor was good. It gave you confidence. (Participant in Glasgow)

Coming down to my level to make me feel like a person. (Participant in London)

Healthcare professionals came down to patients’ level but in the restaurant they stay standing. (Participant in London)

Restaurant had a more personal touch. You were asked about your day and how it was going. This could be transferred to a hospital setting to put people at ease. (A Participant at Worcester)

In the restaurant it was much more personal. If a nurse could do it like a waiter it would be better. (Participant in Worcester)

In the restaurant scenario there was a bit too much small talk. I didn’t want to give an account of my day. (Participant in London)

I was asked ‘how was your day’ but it wasn’t said authentically. It was the body language and that it was said too soon. (Participant in London)

The waiter asked a question about my day but did not seem to be interested in my answer. (Participant in London).

I think small talk is interesting here. There was no small talk at all in the hospital, she just went straight in, whereas there was too much in the restaurant. (Participant in London)

In the restaurant, I was instantly attended to and the attentiveness carried on throughout. For example, I was immediately offered a table, seat, and water. The waiter asked about my day, stayed available and took in consideration my food allergies. (Participant in Worcester)

When you’re having a meal you don’t always want the people who see you. In a clinical setting it’s more reassuring, but there is a fine balance between being attentive and knowing when to give space. (Participant in London)

It shouldn’t matter if it is a hospital or a restaurant as you should make people feel good and important. (Participant in London)

I was in first but was last to be seen which always happens to me. Then I felt worried if my name had been taken off the list. (Participant in Worcester)

Waiter checking if you were okay and asking if something can be done. (Participant in Glasgow)

People are in pain and anxious, and you also see these people in restaurants. Try and get a sense of what they need or what you can do to make them happy. (Participant in London)

You can’t remember what people say but you remember how they make you feel. (Participant in London)

In clinical, focus on efficiency in getting everyone through the system. I felt as if I was on a conveyor belt. (Participant in London)

If I had to say one thing … If I had to make a trip to the doctor’s and the person could see me as a human being rather than as a patient. (Participant in London)

Recommendations

On the basis of these findings we have compiled a list of recommendations () from our scenario participants about what clinicians and restaurateurs can learn from one another’s practices.

Table 3. Recommendations for clinical practice.

Discussion

The patient or customer experience is central to high quality care [Citation1–3]. This simulation-based study identified the key components and the finer nuances of such experience. In both hospital and restaurant sectors, a good or bad experience created a sense of polarity: whether you were treated as a person with feelings and concerns, or as an object ‘on a conveyor belt’. Our data suggested that a good experience entails being informed in advance in an accessible way; having a conversation with a professional with an opportunity to ask questions and to address concerns; being in a relaxing environment where professionals can manage being busy; being treated as a person by an attuned professional.

The clinical world is usually characterized by brief encounters where there seems to be little time to appreciate a patient’s individual situation as cases are sped through the system [Citation6]. Tuning in with the emotional state of patients could help to ensure that people feel cared for. On arrival people want to feel they are welcome and have a sense of belonging to the place they have come to, whether a hospital or a restaurant. The participants felt simple gestures were sufficient: showing attentiveness with eye contact, smiling, and light conversation. However, this must be perceived as authentic, as coming from the heart. While the restaurant and the front-of-house hospitality professionals in our simulations engaged in small talk, such conversation could be sometimes perceived by guests as ‘out of tune’: formulaic and meaningless, inadvertently creating a feeling that the guest is an object of a protocol (‘must talk to customers’). Genuine sensitivity gauges whether such conversation is wanted or not. What seems important is to establish a feeling of being treated as a person with needs, fears, and feelings.

Healthcare professionals can implement the recommendations in the study for daily clinical practice. These actionable steps are behaviours that can have immense payoffs in improving patient experience. If we know that smiling and eye contact can go a long way in helping patients to feel seen and acknowledged, it costs nothing to implement. Likewise, remembering that patients entering hospitals are dealing with different levels of fear and anxiety, it costs nothing to attune to these emotional states in the interactions that follow. Myths and misconceptions prevail that professionals in each sector ought to be perfect service providers; our study suggests that human to human interaction makes the difference, not perfection. As one participant in Worcester put it, ‘I’m not bothered by service faux pas, it gives you a story’. We have learned from the restaurant sector that front-of-house staff must remain alert, improvise, and use their senses to gauge what guests might need [Citation14]. Instances of effective interaction thus focus on the individual patient or diner; this attuned communication encapsulates elements from each of the themes identified. Though additional resources might be needed to develop staff training programmes to disseminate such learning and to better adopt these practices in healthcare, long-term benefits are likely to outweigh costs since patient experience is related to health outcomes and the long-term wellbeing of patients [Citation12,Citation15].

However, we must think critically about the feasibility of implementing some of the recommendations within healthcare. There are at least two broad reasons why some of the recommendations might struggle to gain traction. First, staff wellbeing is crucial for patient experience. Clinical realities are marked by occupational stress, lack of support from the top down, and sometimes mistreatment of the frontline staff, which contribute to unhappiness and exhaustion, impacting the patient experience (e.g. [Citation16–19,Citation21–23]). Seriously ill and vulnerable patients are likely to cause additional concerns for staff not comparable to fine-dining or other hospitality settings. For example, the emergency departments in the US that are located in low-income areas provide care for large urban populations that have no access to primary care [Citation42]. The emergency care settings would almost certainly need to adapt the recommendations to suit the tensions of these work environments. The acute needs of their patients are unlike the needs of patients waiting for an appointment at a general practitioner’s office, or indeed of the clientele using fine-dining services. Some of the recommendations in this article, such as the provision of written information (a ‘menu’ of the events) or small talk can be difficult to achieve in all care environments. We should not forget the high level of employee burnout generally experienced in the service industry sector [Citation43], but not necessarily in restaurants, such as The Fat Duck, that invest in staff satisfaction and wellbeing.

Second, improvement resistance is known to pose challenges in healthcare. Staff might need serious convincing there is a real problem to be addressed, and it can be difficult to sustain enthusiasm to novel practices when work priorities change [Citation27]. The best approach requires working with the healthcare professionals, listening and learning from them how the recommendations might be implemented [Citation32]. Healthcare staff need support in improving patient experience from within rather than be directed from the outside. This article proposes simulation as useful way to invite healthcare professionals and patient groups to design recommendations together in a non-personalized environment.

Simulation offers great potential in the patient experience research, as it can elicit feelings and responses in the moment. Traditional measures of the patient experience, such as surveys [Citation1,Citation5] are often limited due to reductionist and pre-determined approaches that build on questions about past events and hence do not get to the details of real-time interactions and emotional responses. While surveys provide a consistent approach to gathering data, they often use numerical ratings (Likert scales) or yes/no answers to quantify results, building on pre-determined questions reflecting the survey designer’s priorities. Open-ended text options enable respondents to elaborate but can also be overly specific, relating to a certain event rather than to the general feel of the experience of care. Simulation thus provides a realistic yet safe proxy for personal experience [Citation33]. In this study we have used it to place dining and clinical care alongside one another to generate an understanding of the experience of care directly, in a way that might not be possible with the traditional self-report methodology.

Limitations

The generalisability of our results is limited. Firstly, the engagement events were open to the public, hence the participant demographics, such as age, gender, or overall health status, could not be controlled. Similarly, it was not possible to control socioeconomic indicators, such as participants’ level of education or postcode data. Future research with purposive sampling could control these factors to examine the possible influences of the health status, social class, and poverty to how care is perceived.

Secondly, it was not possible delineate how the perceptions and the needs of patients with life-threatening or severe conditions might differ from relatively healthy people. Not only do people’s expectations differ when entering a hospital or a restaurant, but also patients’ needs are likely to differ if they are waiting for, say, an MRI scan or a regular health check-up. Certain patient groups, such as cancer patients, are physically and psychologically more vulnerable and specific procedures can magnify the anticipatory anxieties during the waiting periods. Designing future research for specific patient or treatment groups could help to tailor the principles of care to their needs.

Thirdly, our study was limited to the moments of waiting. Communication practices might need modification when a treatment procedure versus eating at the table are in progress. The need for interaction with the service staff might be reduced while diners are eating, whereas patients might require more verbal or nonverbal support while certain procedures are underway. It would be important that future research expands on the different moments of the care path to explore how the care needs change.

Finally, the methodological limitations related to the technicalities of simulation. Our settings and props provided considerable contextual realism, though space was constrained in some of the venues. This meant that restaurant tables had to be positioned abnormally close to one another, limiting space for the waiters to move around. This may have affected some of the responses about the use of space and the proximity of the professionals. Since the rows of chairs in the simulated clinical area meant that patients did not have enough privacy, some participants (mainly healthcare professionals) commented upon this as a simulation-specific limitation, while other participants (mainly members of the public) felt it was very realistic and true to their experience of real hospitals.

Another issue was the perceived openness during the post-simulation discussions. Some participants may have felt reluctant to voice their concerns about the professionals they had encountered during the simulation so as to not cause offence. To address such limitations, we used private reflection notes, inviting participants to write down additional comments they had not voiced during the discussion. Our impression was that most participants appeared comfortable talking about their experiences, especially as the simulation allowed that experience to be removed from the personal.

Conclusions

The patient experience is a complex healthcare priority which can be approached in real-time using immersive simulation. We have explored the concept of care in two worlds – dining and clinical practice – that are usually kept separate (one framed as pleasurable, the other as necessary but often unpleasant). By combining simulation and engagement we have disclosed real-time perceptions of care and communication that might otherwise have remained hidden. This approach could be applied to better understand the patient experience in other areas of healthcare, comparing to sectors that share similarities of process and care, tailoring it to different patient groups and their care journey.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for supporting this research. We also thank the staff at The Fat Duck restaurant for sharing their practices and participating in the simulated engagement events. A special thanks to Dimitri Bellos (restaurant manager) who has been instrumental in this collaboration. We are grateful to the staff at the NHS major trauma DSU who shared their practices in a busy working environment. Our sincere thanks also to the clinical and hospitality staff who volunteered their time in the simulated events, to the venues which hosted these events, and in particular to SimComm Academy, Laura Coates, and Ambreen Imran.

Ethical approval statement

The project received approval from the Ethics Board of the University of Greenwich and from the UK Health Research Authority.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Terhi Korkiakangas

Terhi Korkiakangas PhD, MSc, BSc is a social interaction researcher with background in Psychology and has methodological expertise in multimodal interaction and conversation analysis. Her research focuses on the use of talk, gaze, gesture, and object-related interactions in everyday and institutional contexts.

Sharon Marie Weldon

Sharon-Marie Weldon PhD, MSc, BSc, RGN is a Reader in Nursing Research and Education at University of Greenwich, and her position is to provide strategic and clinical academic leadership to the development of research capacity amongst nurses, midwives and allied health professionals (NMAHP) at Bart’s Health NHS Trust aligned with the University of Greenwich's research strategy. Her research focuses on novel forms of simulation pedagogy in healthcare.

Roger Kneebone

Roger Kneebone PhD, FRCS, FRCEEd, FRCGP is a Professor of Surgical Education and Engagement Science at Imperial College London. He directs the Imperial College Centre for Engagement and Simulation Science (ICCESS), based within the Division Surgery on the Chelsea & Westminster campus.

References

- Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient-Patient-Centered Outcome Res. 2014;7(3):235–41.

- Darzi A. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report; 2008. www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228836/7432.pdf.

- Francis R. Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry – Chaired by Robert Francis QC. Final Report; 2013. www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/report.

- NHS Improvement. Patient experience improvement framework; 2018. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2885/Patient_experience_improvement_framework_full_publication.pdf.

- Anhang Price R, Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Hays RD, Lehrman WG, Rybowski L, et al. Examining the role of patient experience surveys in measuring health care quality. Med Care Res Rev. 2014;71(5):522–54.

- Montori V. Why we revolt: a patient revolution for careful and kind care. Rochester (Minnesota): The Patient Revolution; 2017.

- Robert G, Cornwall J, Brearley S, Foot C, Goodrich J, Joule N, et al. What matters to patients? Developing the evidence base for measuring and improving patient experience; 2011. Available from: https://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/documents/420/Final%20Project%20Report%20pdf%20doc%20january%202012%20(2).pdf.

- Fregene T, Wintle S, Raman VV, Edmond H, Rizvi S. Making the experience of elective surgery better. BMJ Open Qual. 2017;6(2):e000079.

- Larson E, Sharma J, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö. When the patient is the expert: measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull W H O. 2019;97(8):563.

- Hermann RM, Long E, Trotta RL. Improving patients’ experiences communicating with nurses and providers in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(5):523–30.

- Ajam AA, Tahir S, Makary MS, Longworth S, Lang EV, Krishna NG, et al. Communication and team interactions to improve patient experiences, quality of care, and throughput in MRI. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;29(3):131–4.

- Burt J, Campbell J, Abel G, Aboulghate A, Ahmed F, Asprey A, et al. Improving patient experience in primary care: a multimethod programme of research on the measurement and improvement of patient experience. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2017 Apr. (Programme Grants for Applied Research, No. 5.9.); 2017. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436537/.

- Fisher KA, Smith KM, Gallagher TH, Huang JC, Borton JC, Mazor KM. We want to know: patient comfort speaking up about breakdowns in care and patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):190–7.

- Kneebone RL. The individual and the system. The Lancet. 2017;389:360–1.

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570.

- Dixon-Woods M, Baker R, Charles K, Dawson JF, Jerzembek G, Martin G, et al. Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multi-method study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:106–15.

- Maben J, Adams M, Peccei R, Murrells T, Robert G. ‘Poppets and parcels’: the links between staff experience of work and acutely ill older peoples’ experience of hospital care. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(2):83–94.

- Powell M, Dawson JF, Topakas A, Durose J, Fewtrell C. Staff satisfaction and organisational performance: evidence from a longitudinal secondary analysis of the NHS staff survey and outcome data. Health Ser Deliv Res. 2014;2:1–336.

- West MA, Dawson JF. Employee engagement and NHS performance. Paper commissioned for The King’s Fund review Leadership and engagement for improvement in the NHS; 2012. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/document.rm?id=9545.

- Monsalve-Reyes CS, San Luis-Costas C, Gómez-Urquiza JL, Albendín-García L, Aguayo R, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA. Burnout syndrome and its prevalence in primary care nursing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):59.

- Lu H, Zhao Y, While A. Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:21–31.

- Woodhead EL, Northrop L, Edelstein B. Stress, social support, and burnout among long-term care nursing staff. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35(1):84–105.

- Dawson J. Links between NHS staff experience and patient satisfaction: Analysis of surveys from 2014 and 2015; 2018. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/links-between-nhs-staff-experience-and-patient-satisfaction-1.pdf.

- O'Dowd A. Poverty status is linked to worse quality of care. BMJ. 2020;368:m303.

- Arcaya MC, Arcaya AL, Subramanian SV. Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):27106.

- McCartney G, Collins C, Mackenzie M. What (or who) causes health inequalities: theories, evidence and implications? Health Policy. 2013;113(3):221–7.

- Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Health Foundation's programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(10):876–84.

- Korkiakangas T. Mobilising a team for the WHO surgical safety checklist: a qualitative video study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):177–88.

- Sendlhofer G, Lumenta DB, Pregartner G, Leitgeb K, Tiefenbacher P, Gombotz V, et al. Reality check of using the surgical safety checklist: A qualitative study to observe application errors during snapshot audits. PloS One. 2018;13(9):e0203544.

- Singh N. On a wing and a prayer: surgeons learning from the aviation industry. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(9):360–4.

- Shaw J, Calder K. Aviation is not the only industry: healthcare could look wider for lessons on patient safety. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:314.

- Hollis B, Verma R. The intersection of hospitality and healthcare: exploring common areas of service quality, human resources, and marketing [Electronic article]. Cornell Hospital Roundtable Proc. 2015;4(2):6–15. Available from: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1013&context=chrconf.

- Kneebone R, Weldon SM, Bello F. Engaging patients and clinicians through simulation: rebalancing the dynamics of care. Advances in Simulation. 2016;1(1):19.

- Weldon SM, Kelay T, Ako E, Cox B., Bello F, Kneebone R. Sequential simulation used as a novel educational tool aimed at healthcare managers: a patient-centred approach. BMJ Stel. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000216.

- Weldon S-M, Kneebone R, Bello F. Collaborative healthcare remodelling through Sequential Simulation (SqS): a patient and front-line staff perspective. BMJ Stel. 2016:1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjstel-2016-000113.

- Huddy J, Weldon S-M, Ralhan S, Hanna G, Kneebone R, Bello F. Sequential simulation (SqS) of clinical pathways: a tool for public and patient engagement in point-of care diagnostics. BMJ Open 2016:6.

- Weldon S-M, Ralhan S, Paice E, Kneebone R, Bello F. Sequential simulation of a Patient Pathway. The Clinical Teacher; 2016.

- Weldon S-M, Ralhan S, Paice E, Kneebone R, Bello F. Sequential simulation (SqS): an innovative approach to educating GP receptionists about integrated care via a patient journey – A mixed methods approach. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:108.

- Paice L, Weldon S-M, Ralhan S, Bello F, Kneebone R. Sequential simulation (SqS) of a patient journey: an intervention to engage GP receptionists in integrated care. IJIC. 2015;15. .http://www.ijic.org/articles/abstract/10.5334/ijic.2135/.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: H Cooper, PM Camic, DL Long, AT Panter, DE Rindskopf, KJ Sher, editor. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. p. 57–71.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

- Gindi RM, Cohen RA, Kirzinger WK. Emergency room use among adults aged 18–64: early release of estimates from the National Health Interview survey, January–June 2011. National Center for Health Statistics. May 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases.htm.

- Kim H, Qu H. Employees’ burnout and emotional intelligence as mediator and moderator in the negative spiral of incivility. Int J Contemp Hospital Manage. 2019;31(3):1412–31.

Appendix: DAY SURGERY UNIT WELCOME SPEECH

A verbatim transcript of the speech undertaken by a nurse

– Your first point of call is the reception desk, please register yourself so that the surgeons know you are here.

– FASTING: No eating and drinking at the waiting area because most patients are fasting. If escorts and relatives want to eat, they must do so outside of the waiting area so that patients are not tempted to break the fast. Everyone is hungry.

– If you leave for a walk, please report to the reception so that we are not looking for you or think you have went home.

– We need your escort or next of kin contact number, we need to call them when you have finished surgery. This is that they don’t come here and wait around for you. Also WE will call when you are ready, they don’t need to call here.

– Valuables: We will take your belongings and name label them, but you can also give your valuables to your escort.

– We are a major trauma hospital, we have a helicopter. If emergency comes in and we need the theatre, your case might be delayed. Rarely, but sometimes we can have 8-9 hour delays, very rarely we will have to cancel altogether. But please know that because we are a major trauma hospital this can have an impact on the timing of your operation.

– The first people you’ll talk to are nurses. But you will ask most of your own questions from the surgeons and anaesthetists.

– Note your own questions down now, so that when they come round you will remember them.

– Please be ready to repeat yourself over and over again so that nurses and doctors have the same information about you. We need to ensure that we know your identity and that you have the right medication.

– There will be many people in the room sharing confidential information, please let us know if you have communication problems.

– If you have any questions while you wait, please ask at reception. They can call me in, and if I can’t come straight away because I am busy with patients, another nurse will come if you just wait.