ABSTRACT

Background

Successful comprehensive population-based approaches to chronic disease prevention leverage mass media to amplify messages and support a culture of health. We report on a community-engaged formative evaluation to segment audiences and identify major themes to guide campaign message development for a transformative health communication campaign.

Methods

Four key phases of campaign development: (I) Formative evaluation to identify priorities, guiding themes, and audience segments (interviews/focus groups with residents, N = 85; representatives of community-based partner organizations, N = 10); (II) Brand development (focus groups and closed-ended surveys; N = 56); (III) Message testing approaches to verbal and visual appeals (N = 50 resident intercept interviews); (IV) Workshop (N = 26 participants representing 15 organizations).

Results

Residents were engaged throughout campaign development and the resulting campaign materials, including the campaign name and visual aesthetic (logo, color schemes, overall look and feel) reflect the diversity of the community and were accepted and valued by diverse groups in the community. Campaign materials featuring photos of county residents were created in English, Spanish, and Hmong. Plain language messages on social determinants of health resonate with residents. The county was described as a sort of idyllic environment burdened by inequality and structural challenges. Residents demonstrated enthusiasm for the campaign and provided specific suggestions for content (education about disease risks, prevention, management; information about accessing resources; testimonials from similar people) and tone.

Conclusions

Communication to support a policy, systems, and environmental change approach to chronic disease prevention must carefully match messages with appropriate audiences. We discuss challenges in such messaging and effectiveness across multiple, diverse audiences.

Introduction

Preventable chronic disease remains a leading cause of death and disability in the United States, accounting for 7 of 10 deaths [Citation1]. Although these outcomes are largely the result of individual behaviors, individuals’ health choices are influenced and constrained by context – the policies, systems, and environments (PSE) in which people live, work, learn, and play. Modern public health approaches include efforts to influence these contexts [Citation2,Citation3]. Communication plays an essential role by changing the way the public perceives health and wellness, and by influencing policy and decision-makers by shifting norms from individual behavior change to systemic and structural change for healthier communities [Citation4]. However, although the field of public health generally recognizes PSE, public health practitioners face challenges in communicating about the social determinants of health with community members [Citation5]. To begin, the PSE approach stands in direct contrast to prevailing beliefs about the causes of poor health: Individuals in western societies tend to perceive health as being the (predictable) result of poor individual behavioral choices, or of immutable biological factors (i.e. genetic predetermination), despite ample evidence of the role of societal, political, and environmental factors beyond any individual's control [Citation6–9]. Even people from groups that collectively and individually experience disparities in health outcomes and who can clearly articulate the role of social, environmental, and political factors in health outcomes default to individual-level causal explanations for their own poor health [Citation10–12]. The current historical moment of extreme political partisanship and polarization makes communicating about supra-individual causes of poor health and about health disparities even more difficult, as data from COVID-19 news coverage [Citation13] and messaging about to vaccination and prevention measures have shown [Citation14,Citation15]. Moreover, messaging about policies directly related to the social determinants of health (e.g. education, employment, gender) is rarely linked to health [Citation16,Citation17]. These communication challenges are compounded in rural communities, where the limited access to health care makes public, preventive health communication even more potentially impactful [Citation18,Citation19].

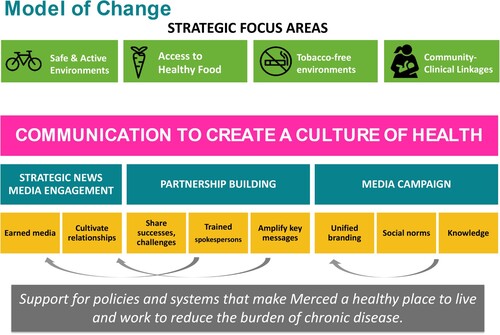

This project thus aimed to advance understanding of strategies for communicating about the social determinants of health with residents of a diverse community. Specifically, we describe the process of developing a ‘healthy community’ brand and identity as part of the County Department of Public Health's funding from CDC's Partnerships in Community Health (PICH) program. The overall aim of that project was to establish a broad-based collaborative to reduce the burden of chronic disease through a focus on four pillars of chronic disease prevention: tobacco (reducing exposure to secondhand smoke and reducing exposure to marketing and sales of tobacco products to minors), physical activity (increasing safe and affordable access to engage in physical activity), food (increasing access to healthy foods through farmer's markets and facilitating farmer-to-corner market sales), and improving community-clinical linkages for preventive service (including a variety of strategies, from providing certification for lactation consultants to creating a county prevention hub to which clinicians could refer patients). Providing a complete explanation of the PICH interventions is beyond the scope of this manuscript; however, we have provided a graphic () to illustrate the overall conceptual model. Underlying the PSE model of change were three distinct communication approaches: strategic engagement with local news [Citation17], organizational communication for partnership and capacity building [Citation20], and a community media campaign that aimed to change social norms and increase knowledge about the social determinants of health. We report on the latter in the present manuscript.

Figure 1. Model of change for a CDC-funded approach to chronic disease prevention underscored by a multilevel communication approach.

Our specific mandate was a communication campaign that would help to create and support a culture of health in a rural community by informing, educating, and empowering residents and decision-makers for individual behavior change and civic engagement. The communication campaign underscored the coalition-led PSE approach to improve access to healthy foods, physical activity, and smoke-free environments that formed the CDC-funded Partnerships to Improve Community Health program. However, the campaign was from the beginning intended to transcend any specific funding source, providing an overarching culturally and linguistically appropriate brand that could be used for prevention efforts for the foreseeable future. In what follows, we describe the audience testing and message development processes we undertook to determine key messages and approaches to accommodate three distinct languages and cultural perspectives about multiple prevention topics within one overarching brand.

Methods

To develop a campaign that would be culturally and linguistically appropriate and tailored to the county's residents, we conducted multiple rounds of mixed methods research with multiple, distinct intended audiences. Broadly, the intended audience includes all County residents; in particular, the campaign sought to reach residents in underserved communities of the county, including Spanish-speaking Latino and ethnic Hmong populations. We employed an iterative, mixed methods approach to develop and test campaign names, logos, and messaging for the campaign. Our approach had five distinct phases:

Formative evaluation: First, we conducted a series of focus groups with residents (N = 89 participants) to explore perceptions of health and safety in the community. Second, we conducted interviews in-depth interviews with representatives from organizations that serve distinct geo-ethnic communities across the County (N = 10) to identify priorities and guiding themes for the overall brand and campaign. Together, this information informed initial campaign concepts and helped to determine audiences.

Message testing Round 1 (focus groups): After developing and narrowing a list of potential campaign names, we conducted four (4) focus groups in three languages (English, Spanish, and Hmong) to obtain intended audiences’ feedback on five (5) campaign names and creative assets (fonts, color schemes). In addition, participants filled out a close-ended survey (N = 56). Based on this initial round of testing, we worked with members of the Collaborative, representing distinct geo-ethnic communities in the County, to select two final campaign names and develop prototype logos for each.

Message testing Round 2 (focus groups): We conducted three (3) focus groups to assess the effectiveness of different approaches to verbal and visual appeals. Participants (N = 50) in three groups were asked for feedback on six prototype campaign logos.

Message testing Round 3 (intercept surveys): During this round of testing, we conducted intercept surveys with residents (N = 50) to assess responses to two different campaign messages and visual concepts.

Public workshop: Lastly, we conducted a workshop with representatives of key community organizations and community members (N = 26 participants) to finalize the campaign name/brand and obtain feedback on campaign messages.

Focus groups were conducted by trained student facilitators with native language abilities (English, Spanish, or Hmong) using a Facilitator Guide. All materials were provided in the language preferred by the participants. Focus groups lasted approximately 60–90 min and were attended by the facilitator and at least one notetaker. Participants completed a short demographic survey and received a $25 gift card upon completion. The protocols for human subjects research were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of California, Merced and John Snow, Inc., and data were collected March 2016 through March 2017.

Setting

A growing, rural county located in California's geographic heart within the San Joaquin Valley, home to much of the state's agricultural production. The county is ethnically and linguistically diverse: the majority (58.2%) of residents are Hispanic or Latino, 28.9% are White, 8.1% are Asian, and 4.1% are Black; more than half of county residents report speaking a language other than English at home.

Results

Phase I: formative evaluation

The initial step in campaign development was to understand perceptions of health, safety, and community connectedness and challenges related to these. We conducted focus groups with community members (N = 89 participants; ), asking first the extent to which they perceive their community as safe and healthy, barriers to safety and health, and the major issues they experience. In addition, we sought to understand the strengths that residents perceive about their communities, including the ideas, images, and words that evoke positive emotions and that may be used in branding materials. The goal of this activity was to identify major themes to guide the development of the essential elements of the campaign brand, including the campaign name and logo ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Community members had strong opinions about life in the county and articulated simultaneously strong positive and strong negative descriptions of their communities. Participants from across social classes, ethnic groups, language spoken, and geographic communities described the county as a sort of idyllic environment that was nevertheless burdened by inequality and structural challenges. However, members also described the negative aspects, including specific issues of infrastructure, joblessness, the environment, and violence. All these descriptors were qualified with a disclaimer that one's experiences of life depend on the specific neighborhood in which one lives: Participants were acutely aware of the vast differences that exist between the more affluent and well-resourced North Merced (city) and other areas of the county. The most common health concerns were consistent with those driving the burden of chronic disease: obesity, diabetes, allergies, asthma, and air quality. Participants also identified structural barriers to healthy living, including inequality, poverty and lack of economic opportunity, violence (including gang violence and drug use), and environmental issues such as pollution and drought.

In general, participants reacted positively to the idea of creating a community-wide campaign and provided specific guidance. We also conducted interviews with community partners and Public Health Department staff to determine their vision and priorities for the community-wide campaign and any initial ideas for campaign names, logos, and imagery. Combined, this formative research guided the development of initial campaign names and logo concepts.

Phase II: Message Testing Round 1

The first round of audience testing included four focus groups with members of the intended audiences, conducted in English, Spanish, and Hmong. The goal of the first round of audience testing was to obtain audience evaluations of five (5) proposed campaign names and visual elements including sample fonts and color scheme. Participants first discussed each campaign name, before reviewing a series of five handouts that included the campaign names in different color palettes and fonts. The campaign names tested were:

Inspire Health

Merced County: Where Health Grows

Viva Health

Heart of Health, Merced County

All In for Health

Of the five campaign names that were tested, two stood out as most favorable and elicited minimal or no negative responses: ‘All In for Health’ and ‘Inspire Health’. ‘All In for Health’ was the top choice and also seemed to evoke the campaign goals of engaging individual and social change. It also evoked for many participants a sense of inclusiveness of diverse constituencies and of a range of conditions that contribute to health. In contrast, while ‘Inspire Health’ was the second-ranked choice, participants linked the name with individual behavior change rather than with structural determinants.

Phase III: Message Testing Round 2

Based on the first round of audience testing, we worked with partners from the collaborative, representing diverse geo-ethnic communities, to select two campaign names to move forward – ‘All In for Health’ and ‘Where Health Grows’. Though there was a lack of consensus in Round 1 of testing on the campaign name ‘Where Health Grows’, partners chose to move forward with this option, eliminating the second-ranked ‘Inspire Health’ due to its association with individual behavior change. Six prototype logos were developed based on audience preferences for color schemes and font choices and tested with participants in three language-based focus groups (English, Spanish, and Hmong bilingual). Participants received a series of color handouts, each with one logo/campaign name combination. They were asked for their emotional reactions as well as whether they thought the logo and/or campaign name represented Merced; after all logos had been discussed, participants were asked what they thought about each campaign name and to select a favorite logo/name combination.

Overall, ‘All In for Health’ received the most positive feedback, with participants from the Spanish-language group enthusiastically feeling that it represented the county and that the spirit of inclusivity was aspirational and motivational. As in the first round of testing, both groups described that this name implied a sense of unity, strength, inclusiveness, and community members coming together. This campaign name was also described as aspirational. Participants also suggested that it was inviting, meaning that the community was being invited to take part in the initiative: ‘it can be the hands of different children or different people that are representing that in one way or another, they’re taking care to have better health’. Participants in the English- and Spanish-language groups generally reacted positively to the use of the hands in the logo image and indicated that it seemed clearly connected to the campaign name. However, ‘Where Health Grows’ was also positively received by many and was the preferred choice among participants in the Hmong focus group.

Color preferences differed between audience segments. While the yellow and pink combination was well-ranked across all groups, participants in multiple groups associated the yellow with drought and dryness, especially in the instance of the yellow leaves. Negative feedback about the yellow color particularly contrasted with feedback from participants in the English-language group reflecting that the green signified that the flower looked alive. The Hmong group also felt strongly that green should be incorporated in the branding.

Reactions to the logo images also differed by audience segment in culturally consonant ways. For example, Hmong participants expressed concerns about the original version of the logo: Intended to illustrate hands working together, the initial version of the logo had significant white space that was interpreted by Hmong speakers first – they saw fishbones in the white space rather than the pink or yellow hands.

Phase IV: Message Testing Round 3

Based on the second round of audience testing, we created sample campaign messages and visual concepts for ‘All In for Health’ to test through intercept surveys. The goal of this round of testing was determine which types of imagery and messaging most resonated with the distinct intended audiences. Surveys given to 50 community residents presented two different styles of campaign messages and two visual concepts, described below.

Concept A featured a first-person testimonial (e.g. ‘I’m all in for health. Eating more fruits and vegetables helps me stay healthy’) and portrait-style photos of diverse people in various settings (e.g. at a park, gardening) stating why and how they are ‘all in for health’.

Concept B featured a third-person statement (e.g. ‘Everyone in Merced County should have the opportunity to make healthy choices’) paired with a close-up image of hands (mimicking the campaign logo) holding items such as fruit, exercise equipment, etc. that reflect different content areas.

The results of the intercept survey demonstrated a slight preference for messaging including third-person statements about opportunities for health in Merced County. This was also reflected in respondents’ feedback on visual concepts: most respondents preferred Concept A featuring portraits of people in a range of different settings, noting that these images were family-oriented, relevant, and reflected healthy choices or lifestyles. Some respondents preferred Concept B given the specific items (e.g. fruit or playing sports) shown in the images.

Phase V: public workshop

Lastly, we engaged a group of community partners to provide feedback on draft messages for the campaign. Messaging focused on healthy communities and social determinants of health and included specific messages about healthy eating, physical activity/safe and active environments, and breastfeeding in addition to general messages. Participants were asked to review messages pertaining to their specific expertise and asked to identify their preferred messages and any needed adjustments.

Putting it all together: 'The All In for Health' Campaign

The final campaign, All In for Health, reflects the diversity of the County with the intention of raising awareness of the social determinants of health to foster a culture of health. The campaign features photos of community members in various settings (community garden, local parks, etc.) to reflect the diversity of the county, as well as plain language messages regarding opportunities for health and social determinants of health in the third person. Print and digital materials – including postcards, posters, and social media content – were developed in English, Spanish and Hmong.

Given different preferences between intended audience groups, the final campaign logo and branding was implemented in two color schemes. English and Spanish-speaking participants preferred the yellow/pink color scheme for the logo while Hmong speakers preferred a green/teal color scheme. In addition, creative materials underwent multiple rounds of adjustments to incorporate community feedback in terms of color selection and adjusting the logo to address negative space concerns.

Formative research with community members and representatives from partnering geo-ethnic community organizations was essential to develop a tailored campaign that resonates with multiple, distinct intended audiences. The ‘All in for Health’ brand and messaging have been adopted by the County's Health Equity Coalition, which will carry out the County's Community Health Improvement Plan.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we have reported on a mixed-methods approach to designing and testing messages to communicate the social determinants of health in an ethnically and linguistically diverse community that is troubled by significant disparities in health outcomes, income, educational attainment, and access to health care. We successfully created a single campaign and overarching brand that is flexible enough to cover a range of health topics and activities happening under the grant-funded initiative and that appeals to diverse communities as well as to the many community partners that were part of the coalition and county leadership. Yet despite our ultimate success with this project, we identified several significant challenges to inform future research, and which can serve as lessons learned for future public health practitioners interested in developing similar campaigns.

To begin, a key challenge in developing the campaign materials was a core component of health communication – matching the right audience with the right message about social determinants of health. We began with an explicitly inclusive mandate: Our campaign should be developed with and for the members of the community who are at greatest structural disadvantage. Yet this goal turned out – perhaps unsurprisingly in retrospect – to be inappropriate for the kinds of messages that we originally sought to develop. That is, we found that residents of structurally disadvantaged communities were quite capable of articulating how structural barriers affected their health; thus, they did not ‘need’ the persuasive or educational messages about the social determinants of health that we had been tasked with developing. This finding is somewhat consistent with research in diverse settings, from the rural southern U.S. to urban communities around the globe, which has found that residents of underserved communities who experience inequality are able to articulate the ways in which health is affected by supra-individual factors, based on their lived experiences [Citation21–26]. However, our findings go beyond prior research in that our participants generally perceived the PSE approach as quite logical. That is, they not only articulated the role that their built environment and the policies and social structures governing their lives negatively affected their health, but they also articulated strong support for the coalition's PSE approach. Nonetheless, our participants – residents of structurally disadvantaged communities – felt powerless to address these challenges. Moreover, participants attributed responsibility for addressing the social determinants of health to actors outside of their communities, including elected policymakers, regional authorities, and others with greater privilege than themselves. Those external actors represent important audiences needed to advance a PSE approach; however, identifying them and developing messages that would be persuasive to those groups fell outside of the scope of our project. A key takeaway, then, is that messages for under-resourced populations must have different intended outcomes than for more powerful groups that need to be made aware of the social determinants of health and persuaded to act. To put it bluntly, efforts to achieve health equity need to carefully consider the match between the goal or campaign objective and the intended audience – PSE approaches likely require the substantive engagement of majority populations (e.g. to support specific policies) that do not experience disparities, even as they aim to address health disparities.

In addition, our study demonstrates that with campaigns that encompass multiple languages and cultural perspectives, branding efforts may need to be flexible. For example, for this campaign, we needed two distinct color schemes to adequately represent the perspectives of the three major ethnic groups. An important implication is that adequate funding for such efforts needs to consider that there may be multiple campaigns.

Moreover, the people and settings chosen to portray communities matter. In this campaign, and in others where communities are underrepresented in stock images, original photography with actual residents was the only way to really capture the right ‘look and feel’. To ensure that the campaign creative reflected the communities, we prioritized available resources to hire a professional photographer for a photoshoot in the County using actual community members as models in recognizable community settings (e.g. a local park, a community garden, etc.). The resultant campaign photo library captures the ethnic diversity of the community as well as spaces and activities that are sources of pride for residents.

We also highlight the use of multiple methods [Citation27] to obtain feedback from intended audiences on visual appeal. Focus groups focused on testing sample color schemes, font choices, logo prototypes in a group discussion setting. For the final round of testing, we used intercept surveys to test two different message styles and two visual concepts with individuals. This mixed-methods approach allowed us to leverage limited resources for message testing to maximize the diversity of participants and the quantity and quality of responses for different components of the campaign development process.

Conclusion

Culturally and linguistically appropriate communication is an essential component of a comprehensive approach to changing the policies, systems, and environments that help people live healthier lives. Creating communication campaigns that effectively convey the social determinants of chronic disease prevention relies on thorough formative evaluation such as the process that we describe, and, crucially, a clear understanding of the intended outcome along with a match to the intended audience.

Disclaimer statements

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of California Institutional Review Board ON March 9, 2016 (decision n. UCM15-0037).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

- Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(3):364–72. doi:10.1177/1090198111418634

- Brown AF, Ma GX, Miranda J, Eng E, Castille D, Brockie T, et al. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S72–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304844

- Dorfman L, Wallack L. Moving nutrition upstream: the case for reframing obesity. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(2 Suppl.):S45–50. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.018

- Hull S, Stevens R, Cobb J. Masks are the new condoms: health communication, intersectionality and racial equity in COVID-times. Health Commun. 2020;35(14):1740–2. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1838095

- Kriznik NM, Kinmonth AL, Ling T, Kelly MP. Moving beyond individual choice in policies to reduce health inequalities: the integration of dynamic with individual explanations. J Public Health. 2018;40(4):764–75. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdy045

- Blue S, Shove E, Kelly MP. Obese societies: reconceptualising the challenge for public health. Sociol Health Illn. 2021;43(4):1051–67. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.13275

- Kelly MP, Russo F. Causal narratives in public health: the difference between mechanisms of aetiology and mechanisms of prevention in non-communicable diseases. Sociol Health Illn. 2018;40(1):82–99. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12621

- Greener J, Douglas F, van Teijlingen E. More of the same? Conflicting perspectives of obesity causation and intervention amongst overweight people, health professionals and policy makers. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1042–9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.017

- Lundell H, Niederdeppe J, Clarke C. Public views about health causation, attributions of responsibility, and inequality. J Health Commun. 2013;18(9):1116–30. doi:10.1080/10810730.2013.768724

- Putland C, Baum FE, Ziersch AM. From causes to solutions - insights from lay knowledge about health inequalities. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):67. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-67

- Cannon JS, Farkouh EK, Winett LB, Dorfman L, Ramírez AS, Lazar S, et al. Perceptions of arguments in support of policies to reduce sugary drink consumption among low-income White, Black and Latinx parents of young children. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36(1):84–93. doi:10.1177/08901171211030849

- Gollust SE, Fowler EF, Vogel RI, Rothman AJ, Yzer M, Nagler RH. Americans’ perceptions of health disparities over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from three nationally-representative surveys. Prev Med. 2022;162:107135. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107135

- Nan X, Iles IA, Yang B, Ma Z. Public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: lessons from communication science. Health Commun. 2022;37(1):1–19. doi:10.1080/10410236.2021.1994910

- Golos AM, Hopkins DJ, Bhanot SP, Buttenheim AM. Partisanship, messaging, and the COVID-19 vaccine: evidence from survey experiments. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36(4):602–11. doi:10.1177/08901171211049241

- Fowler EF, Baum LM, Jesch E, Haddad D, Reyes C, Gollust SE, et al. Issues relevant to population health in political advertising in the United States, 2011-2012 and 2015-2016. Milbank Q. 2019;97(4):1062–107. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12427

- Ramírez AS, Estrada E, Ruiz A. Mapping the health information landscape in a rural, culturally diverse region: implications for interventions to reduce information inequality. J Prim Prev. 2017;38(4):345–62. doi:10.1007/s10935-017-0466-7

- Matsaganis MD, Wilkin HA. Communicative social capital and collective efficacy as determinants of access to health-enhancing resources in residential communities. J Health Commun. 2015;20(4):377–86. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.927037

- Carnahan LR, Zimmermann K, Peacock NR. What rural women want the public health community to know about access to healthful food: a qualitative study, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:150583. doi:10.5888/pcd13.150583

- Estrada E, Ramirez AS, Gamboa S, Amezola de herrera P. Development of a participatory health communication intervention: an ecological approach to reducing rural information inequality and health disparities. J Health Commun. 2018;23(8):773–82. doi:10.1080/10810730.2018.1527874

- Popay J, Bennett S, Thomas C, Williams G, Gatrell A, Bostock L. Beyond 'beer, fags, egg and chips'? Exploring lay understandings of social inequalities in health. Sociol Health Illn. 2003;25(1):1–23. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00322

- Davidson R, Mitchell R, Hunt K. Location, location, location: the role of experience of disadvantage in lay perceptions of area inequalities in health. Health Place. 2008;14(2):167–81. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.05.008

- Garthwaite K, Bambra C. “How the other half live”: lay perspectives on health inequalities in an age of austerity. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187:268–75. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.021

- Smith KE, Anderson R. Understanding lay perspectives on socioeconomic health inequalities in Britain: a meta-ethnography. Sociol Health Illn. 2018;40(1):146–70. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12629

- Halliday E, Brennan L, Bambra C, Popay J. ‘It is surprising how much nonsense you hear’: how residents experience and react to living in a stigmatised place. A narrative synthesis of the qualitative evidence. Health Place. 2021;68:102525. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102525

- Davidson R, Kitzinger J, Hunt K. The wealthy get healthy, the poor get poorly? Lay perceptions of health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(9):2171–82. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.010

- Weathers B, Barg FK, Bowman M, Briggs V, Delmoor E, Kumanyika S, et al. Using a mixed-methods approach to identify health concerns in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2087–92. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.191775