ABSTRACT

Objective: The electronic patient record (EPR) has been introduced into nursing homes with the aim of reducing time spent on documentation, improving documentation quality and increasing transferability of information, all of which should facilitate care provision. However, previous research has shown that EPR may be creating new burdens for staff. The purpose of this literature review is to explore how EPR is facilitating or hindering care provision in nursing homes.

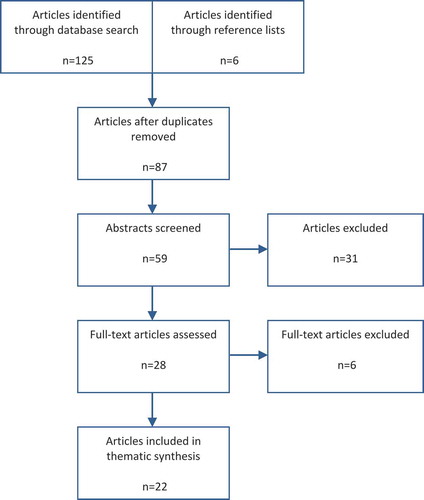

Methods: An integrative literature review was carried out using four electronic databases to search for relevant articles. After screening, 22 articles were included for thematic synthesis.

Results: Thematic synthesis resulted in six analytical themes linked to care provision: time for direct care; accountability; assessment and care planning; exchange of information; risk awareness; and person-centered care.

Conclusion: For EPR to facilitate care provision in nursing homes, consideration should be given to the type of device used for documentation, as well as the types of applications, the functionality, content, and structure of EPR. Further research exploring the experiences of end users is required to identify the optimal characteristics of an EPR system specifically for use in nursing homes.

Introduction

In recent decades, a change in demographic trends in Europe has led to an increasingly aging population.Citation1 Consequently, there has been a rise in the number of people being diagnosed with non-communicable diseases, such as dementia, which has placed new demands on the long-term care sector.Citation2 An effective response to the challenge of delivering healthcare to an aging population may incorporate the introduction and utilization of appropriate technology,Citation3–Citation5 and the electronic patient record (EPR) is one technological solution that has been identified as potentially beneficial for facilitating the provision of care in a nursing home environment.Citation6–Citation8

Healthcare today has been described as “information-intensive.”Citation9 Consequently, completing documentation has become one of the most time-consuming activities for staff, meaning that they spend less time on delivering direct care.Citation10 Furthermore, traditional, paper-based documentation is often inconsistent, incomplete, and illegible,Citation11 as well as out-of-date and difficult to update.Citation12 As a result, there is an increase in the possibility for errors and a reduction in the quality of care.Citation13

In nursing homes, EPR systems may be used to record various nursing processes, such as assessment and care planning, and to write daily progress notes and handover forms.Citation14 Potential benefits associated with using EPR include the effective management of chronic conditions,Citation15 the collection of longitudinal information,Citation8 and the ability to rapidly access information securely.Citation8 Consequently, EPR may assist staff to deliver a more person-centered approach to care.Citation16 Furthermore, the increased legibility and accuracy associated with electronic documentation should result in a reduction in data errors and improve standards of care.Citation17 EPR also has the potential to lead to greater transferability of information across multiple stakeholders,Citation17 allowing for a more integrated approach to care provision.Citation18 Finally, EPR has also been associated with raising the “social standing of care work.”Citation16

Despite the potential benefits, the uptake of EPR in nursing homes has varied considerably across countries, with much of the literature referring to a “technology lag.”Citation16,Citation19,Citation20 Furthermore, a previous systematic review of six studies exploring staff experiences with IT implementation in nursing homes found that the introduction of IT for documentation purposes may bring both benefits and burdens.Citation21 Consequently, there have been calls to expand research to further examine the impact that electronic documentation systems have on working practices in nursing homes.Citation9,Citation15,Citation22 Therefore, this literature review aims to add to existing knowledge in the field by exploring the impact of electronic documentation systems on the provision of care in nursing homes.

Method

Study design

The following literature review takes an integrative approach, synthesizing evidence from both quantitative and qualitative studies. Although integrative reviews allow for the “inclusion of diverse methodologies,” they have been criticized for their lack of methodological rigor and bias.Citation23 Therefore, Whittemore and Knafl suggest a specific framework for carrying out integrative reviews, influenced by the model developed by CooperCitation24 for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This framework is used below to describe the process of data collection, analysis, and synthesis.

Search strategy

Various terms can be found in the literature to refer to technology used to record patient data digitally, which are often used interchangeably.Citation25 For example, in their systematic review, Häyrinen et al.Citation26 found the following common terms: electronic health records (EHR), EPR, and electronic medical records (EMR). The terms EPR and EMR have the same meaning, with EPR more commonly seen in the United Kingdom, and EMR used in the United States. An EPR or EMR is defined as an application that is “composed of the clinical data repository, clinical decision support, controlled medical vocabulary, order entry, computerized provider order entry, pharmacy, and clinical documentation applications” and refers to information collected from one organization.Citation25 Whereas an EHR refers to a broader application, which brings together longitudinal data from an individual’s various EPRs from different healthcare organizations.Citation25

Likewise, the terms nursing home and long-term care are often considered synonymous. In the United Kingdom, introduced in response to “public policy designed to minimise the use of acute hospitals,”Citation27 nursing homes address the more complex medical needs of individuals, including personal care needs.Citation2 The World Health Organization defines long-term care as “the system of activities undertaken by informal caregivers and/or professionals to ensure that a person who is not fully capable of self-care can maintain the highest possible quality of life.”Citation28 One “apparatus” of long-term care is “care in an institutional setting,” such as a nursing home.Citation2

In order to obtain as many relevant results as possible, the terms “electronic medical records,” “electronic patient records,” “electronic health records,” as well as the more general term “electronic documentation,” have been combined with the terms “nursing home” and “long-term care.” Four databases were used to search for articles. shows the exact search string used for each database, along with the number of articles that resulted from the searches.

Table 1. Search strings employed to identify articles.

The following criteria were subsequently used to select appropriate articles:

Inclusion criteria

Published between 2000 and 2017.

Published in English or French.

Original qualitative or quantitative research.

Conducted in a nursing home or long-term care setting.

Research into any type of electronic documentation system used for the purposes of care planning, assessment, records or reports and forms.

Exclusion criteria

Articles published before 2000.

Articles not in English or French.

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or integrative reviews.

Studies carried out in residential homes, hospitals, or in the community. (Some studies compared the use of electronic documentation across a range of nursing environments, such as hospitals and nursing homes. If data from nursing homes could not be extracted, these studies were also rejected.)

Studies that looked only at electronic documentation for medication administration.

Duplicated articles.

The primary search was conducted manually by the first author. A second author conducted a subsequent search of the databases and found no new additional articles. Full texts were then screened using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelinesCitation29 as shown in .

Data analysis

Thematic synthesis was used as a method of data analysis.Citation30 Both the results and discussion sections of the 22 articles were coded inductively by hand line by line, which presented emerging themes across the literature. This process was carried out until saturation of themes was reached. Similarities across themes were then searched for and several were merged and renamed leaving 10. The final stage of thematic synthesis, “generating analytical themes,”Citation30 involved synthesizing these 10 existing themes in order to address the research question directly, leaving the following 6 analytical themes: time for direct care, accountability, assessment and care planning, exchange of information, risk awareness, and person-centered care. summarizes the articles used for thematic synthesis.

Table 2. Summary of articles used for thematic synthesis.

Results

Time for direct care

A number of studies reported that the introduction of an electronic documentation system allowed staff to spend less time on documentation, meaning that they had more time for direct care.Citation5,Citation19,Citation31–Citation33 Staff find using a computer for documentation faster than filling out forms by hand. Furthermore, staff can quickly move from one resident’s record to another, and multiple staff members are able to access records at the same time.Citation32 The processes of data distribution, storage, and retrieval were also described as more efficient,Citation5,Citation19,Citation31,Citation32,Citation34–Citation36 and the presence of a spellcheck saves time on proofreading.Citation37 Moreover, increased legibility has meant that staff are no longer forced to call doctors to clarify information that was previously handwritten, often causing time delays.Citation35

Florczak et al.Citation33 found that portable, handheld devices increased efficiency as they enabled staff to access and record data at the point of care. However, in a separate study, some staff felt that bedside technology was time-consuming, and as a result, they were found to be documenting at the end of their shift, and some documenting before care had been provided.Citation38 In several other studies, it was also suggested that electronic documentation systems do not necessarily save staff timeCitation19,Citation22,Citation36,Citation38 for reasons such as slow log-in processes,Citation9,Citation14 difficulties with updating passwords,Citation35 and having to access each resident’s record individually to chart information as opposed to using one paper chart for all residents.Citation37 In one home, the reporting of incidents required staff to document information into the electronic record and into a separate software system, increasing overall time spent on incident reporting.Citation35

Accountability

Documented evidence of care is essential for managers to “assess whether care […] was professional, safe and competent.”Citation13 In four studies, senior staff highlighted that they are more able to monitor the quality of care provision with an electronic documentation system.Citation5,Citation19,Citation31,Citation34 Electronic documentation also enables managers to identify “patterns and trends in care needs and evaluate outcomes of care,”Citation13 increasing their knowledge about the current health status of residents in their homes.Citation5,Citation19 However, in a study by Yu et al.,Citation37 participants stated that they were not able to easily generate trends from data and require an application that could automatically produce graphs and generate reports. As regards to external audits, staff found that they were able to record the minimum data set (MDS) more accurately with EHR.Citation38 Furthermore, electronic records make it easier to extract relevant information from documentation, allowing inspectors to carry out the audit process with “greater consistency and regularity.”Citation19

One study described the use of iButtons, a device designed to increase accountability, which the staff found “inconvenient and bothersome.”Citation38 iButtons should be worn by residents and staff, and allow for the “verification of caregiver activities” at the point of care.Citation38 However, in the home in this study, residents were often found not to be wearing iButtons and staff had to search for them, causing delays in the documentation, and showing the incorrect time for care delivery. Furthermore, when residents were wearing the iButtons, staff felt that touching the buttons disturbed them. Participants from this study also expressed concern that the increased monitoring of care delivery was making them feel “watched.” Although others believed that monitoring would lead to their work being “recognized.”Citation38

Assessment and care planning

Across several studies, caregivers’ perceptions of using electronic documentation for assessment and care planning were positive.Citation5,Citation19,Citation33 Staff believe that some electronic assessment templates are more thorough as they provide prompts to identify potential problems,Citation19 whilst also guiding nurses “through body systems.”Citation19 Participants in the study by Zhang et al.Citation5 noted that the interface for assessments popped up as soon as a staff member logged in, which enabled them to start with the task as quickly as possible. As regards to advance directives, an electronic intervention implemented into an EHR, designed to encourage documentation of patient wishes regarding life-sustaining care, increased the rate of advance directive discussion notes significantly.Citation39 This was linked with improved accessibility to this section of the care plan as the link was “uniformly placed” within notes, appearing at the top of the patient order list and labeled “code status.”Citation39

Staff from one study also felt that electronic documentation facilitated the writing of care plans because they are more able to access assessment forms and other relevant information and “think more critically” when developing a care plan.Citation5 In particular, staff appreciate being able to switch between documents and copy and paste information.Citation5 Using laptop computers that contain resident information during care planning meetings is also beneficial.Citation32 Furthermore, participants widely reported that electronic systems generate more accurate, complete, consistent, and legible information than paper recordsCitation5,Citation13,Citation14,Citation19,Citation31,Citation33–Citation36,Citation38 and highlighted that their quality does not deteriorate over time like paper records.Citation5

However, several studies indicated that electronic documentation systems may not necessarily facilitate care planning and assessment.Citation13,Citation37,Citation38,Citation40–Citation42 For example, Wang et al.Citation42 carried out an audit study with results suggesting that electronic care plans provided less information about resident diagnosis and outcomes than paper-based records. However, this lack of information was linked with a possible issue with the wording of the data fields, which did not encourage nurses to “formulate diagnosis statements.”Citation42

Other sources of frustration included having to enter unnecessary information, but not having space in data fields for free text.Citation35,Citation37,Citation38 Furthermore, staff found that necessary forms were missing from the system.Citation37,Citation38 In one study, frustrations with unsuitable electronic forms led staff to using shortcuts; in this case, documenting data in free text as opposed to using the forms. However, this meant that information was not standardized and prevented the automatic population of data into reports for trending purposes.Citation38 Suggestions for improvements to systems included a function where staff could enter a keyword and jump to the right section in a resident’s notes, and care plans that could be automatically generated from assessment data.Citation5,Citation36,Citation37

Exchange of information

There were mixed results as to whether electronic documentation facilitated an exchange of information. Issues with external communication were described in one home where staff were restricted from accessing the electronic hospital records of patients who were about to be discharged from the hospital to their nursing home. This meant that hospital staff would fax or send printed hardcopies of electronic records, which were often incomplete, causing time to be lost in contacting the hospital to clarify information.Citation35

Munyisia et al.Citation13 also found that staff did not believe that the introduction of an electronic documentation system had improved communication within the home. This could be linked to slow log-in processes, which in a separate study led staff to avoid recording information electronically.Citation9 However, staff may also be reluctant to change their established means of communication. In two studies, participants reported that they preferred to communicate information about residents verbally within the home.Citation5,Citation37 Moreover, in one study where there had been a reduction in face-to-face communication, staff were concerned about losing “a sense of belonging.”Citation37

Positive ways in which electronic documentation facilitates an exchange of information within the nursing home include the instant availability of records,Citation5,Citation36 which is particularly helpful for staff who have been on leave and need to catch up on notes quickly.Citation5 Furthermore, it allows for immediate access to initial resident assessments so that “correct care” can start straight away.Citation5 Electronic documentation systems may also facilitate an exchange of information outside of the home. In one study, it was described how a camera built into the electronic device allowed staff to take photos of wounds.Citation33 These photos could be uploaded to residents’ records and accessed by external healthcare providers who could then make a remote diagnosis or clinical decision. Staff also found that they could communicate better with physiciansCitation38 and provide more detailed information to families due to the immediate accessibility of records through an electronic system.Citation19,Citation32

Risk awareness

The comprehensive and standardized nature of electronic records are reported to increase the “visibility” of changes in health,Citation35,Citation38 allowing senior staff to “more quickly identify resident care needs.”Citation31 Particularly valuable are applications that can trend clinical problems and produce alerts about new resident events, which direct staff to provide appropriate care.Citation19 For example, in one study, improvements were seen in both the decline of range of motion and in high-risk pressure sores following the implementation of a bedside EMR, which prompted required care.Citation43

An electronic wound documentation system as investigated by Florczak et al.Citation33 was also found to more effectively manage treatment of wounds, promote healing, and enable staff to better recognize changes in wounds. However, nurses did not feel that the system had a significant influence on preventing avoidable wounds from initially occurring, although the authors note that this may be linked to staff not fully implementing the “risk functionality” element.Citation33 Likewise, in another study, alerts were not always utilized, and furthermore, the importance of updating alerts with “best practice information” was highlighted.Citation38

Two studies specifically described the effect of a computer decision support system (CDSS) embedded in an electronic system. Fossum et al.Citation44 found that documentation completed by staff in the intervention group using a CDSS was significantly more complete and comprehensive in recording “the risk and prevalence of [pressure ulcers] and malnutrition.” However, it should be noted that this group were exposed to two simultaneous interventions. In a separate study, AlexanderCitation15 found that alerts produced by a CDSS to warn staff about “potential skin breakdown” did not lead to a significant increase in the recording of clinical responses in most types of documentation, except for turning and repositioning charts for residents.

Data from electronic records may also increase the prediction of fall risk in comparison to data from the MDS alone, linked with the “increased frequency with which EMR data are updated” in comparison to MDS data.Citation45 Another possible benefit of an electronic documentation system is the ability to manage behavior more effectively.Citation5 In one study, staff described how due to the improved accessibility of information they were more able to “analyse common occurrences of certain undesirable behaviours” and understand why they may have occurred.Citation5 This allowed staff to avoid potential triggers when interacting with residents, reducing incidents of undesirable behaviour.Citation5

Person-centered care

In the study by Zhang et al., staff reported that electronic documentation facilitated person-centered care as they were more able to access information about an individual’s past, as well as their current needs, which gives a “broader and more holistic view” of an individual.Citation5 The electronic record system also allowed for the storage of photos of residents, which new staff found to be a helpful tool for learning residents’ names, and access to additional information provided new staff with a topic of conversation for when they met with residents for the first time.Citation5

MeehanCitation35 reported that staff in one home found it difficult to share discharge plans and care instructions with those patients and their families who were only in the home for rehabilitation purposes. They suggested that the introduction of a portable device would act as a tool to take into resident’s rooms and visually show the patient their care plan, as well as web tutorials relating to relevant aspects of care provision.Citation35 Participants from the same study also believed that mobile devices would allow them to have improved access to vital information about a resident’s needs, for example allergies, which is particularly important for those individuals who are only staying in the home for a short time, or for staff who work infrequently in the home.

Discussion

This integrative review has explored the ways in which EPR is facilitating or hindering care provision in nursing homes. The results of this review suggest that EPR may have the potential to assist staff in the provision of care in nursing homes. However, results have also highlighted that in order for this to occur there are certain requirements that should be considered as regards to the type of device and applications used for electronic documentation, as well as the functionality, structure, and content of EPR. These are summarized in and subsequently described.

Table 3. EPR facilitators for care provision.

Device and applications

A number of studies in this review highlighted the importance of technology that can be accessed at the point of care.Citation22,Citation33,Citation36,Citation37 This echoes results from a study by Chau and Turner,Citation46 who explored nursing home staff’s experiences with using mobile, handheld technology. They found that the quantity and quality of documentation improved with the use of a mobile device, and that documenting information at the point of care was less time-consuming. Furthermore, in this review, portable devices were described as particularly useful for providing person-centered care.Citation5,Citation35 However, as found by Rantz et al.,Citation38 introducing devices for bedside documentation has the potential to create burdensome expectations for staff, and as a result, they may be reluctant to record documentation. Another device considered burdensome by staff was iButtons.Citation38 Although this device promoted accountability, developers should also take into account that devices do not disturb or invade residents’ privacy, or make staff feel watched.

Florczak et al.Citation33 highlighted the benefits of portable devices with cameras that enable staff to take photos of wounds, which can easily be shared with relevant external healthcare providers, who can then suggest appropriate care. As regards to applications for EPR systems, a spell check, a copy and paste function, as well as a function to enter a keyword to search for specified information within records were all identified as saving staff time.Citation5,Citation36,Citation37 Secure log-in processes should also allow for quick access to records so that staff are not prevented from accessing information prior to care delivery.Citation9

Functionality

Munyisia et al.Citation22 argue that electronic documentation systems should act as more than “a repository of information” and prompt staff about changes in residents’ condition. A CDSS embedded into a system may be useful in alerting staff to potential risk factors and enable them to provide the correct care accordingly. However, the two studies used in this review that explored CDSS did not conclusively support such an application for increased documentation of clinical responsesCitation15 or improved documentation of ulcer and malnutrition-related assessments and interventions.Citation44 Furthermore, it is important that alerts are consistently updated in line with good clinical practice in order to support evidence-based practice in nursing homes,Citation44 and that the CDSS is user-friendly.Citation47 Participants also thought that alerts that prompt staff to create or update a document would be useful and highlighted the need for the EPR to generate care plans from assessment data, as well as to create graphs from data to produce trending reports.Citation37

Another common requirement identified across the studies was the need to be able to share and access information externally.Citation33,Citation35,Citation38 The transferability of information is particularly important in the long-term care sector as patients are frequently transferred from hospitals to nursing homes and effective transitions of care are required.Citation48 The lack of ability to share information across care providers has been described as “the largest limitation factor” of electronic records.Citation49 Widely introduced in Canada, interoperable EHRs are “a secure consolidated record of an individual’s health history and care, designed to facilitate authorised information across the care continuum.”Citation50 Ensuring interoperability of future EPR systems is particularly important as information gaps in long-term care have been shown to have consequences for patients, clinicians, and the healthcare system.Citation48

Structure and content

One of the principal reasons for the introduction of electronic records was to improve the quality of documentation, specifically assessments and care plans.Citation13,Citation42 However, Wang et al.Citation42 found that staff were documenting less information relating to the nursing problem and resident outcomes. This was linked to possible flaws in the language used to prompt staff to record information. Furthermore, a lack of appropriate forms meant that staff in one study were found to be adding notes in free text, preventing the automatic population of data into reports.Citation38 Therefore, as well as including the appropriate forms for the environment, developers should ensure systems allow for a structured form of data entry with “formalised nursing language,”Citation42 which will also mean that decision-making tools can be successfully integrated into EPRs.Citation26

Nurses also identified the importance of structured templates for assessment purposesCitation19 and links to important documents that should be accessible and “uniformly placed.”Citation39 In addition, the EPR should allow for the detailed collection of information about a resident’s background. Such information was highlighted as being particularly important for new staff whilst they are becoming acquainted with residents,Citation5 but may also act as a useful source of information for staff who work infrequently in the home. Furthermore, person-centered care is an integral part of dementia care,Citation51 and access to a detailed history may improve staff’s understanding of a resident’s behavior and how to respond appropriately.Citation5

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the nature of integrative reviews, which are complex due to the way in which they combine studies with diverse methodologies, potentially leading to bias.Citation23 This study has used the PRISMA guidelinesCitation29 in order to increase transparency and reduce bias. However, the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research is a developing area and currently lacks explicit guidance.Citation52 Restrictions to articles in either English or French may have meant some studies were not included, and as Google Scholar was not used in the search, additional gray literature may have been missed, which could have provided a wider insight into the topic. Finally, a number of issues relating to implementation of EPR were raised in many of the articles used in this research. However, this review has not focused on these issues as they have been described in detail in numerous other studies.Citation21,Citation53,Citation54

Conclusion

One of the principal reasons for the introduction of EPR into nursing homes was to assist staff to provide care.Citation6,Citation7,Citation41 However, findings of this review have shown that several aspects relating to the EPR system are hindering care provision in nursing homes, and that consideration should be given to numerous factors linked to the device, applications, structure, content, and functionality. Within the literature used for this review, there were some references to the technology that staff are currently using to document information electronically, as well as suggestions for modifications to existing technology that would increase usability. However, more research is required to identify the optimal characteristics of an EPR system for use in a nursing home environment, and in particular, research that focuses on the end user’s experience of EPR.

Author contributions

K.S., I.H., and O.S. devised the topic for this review. K.S. and M.S designed the search strategy and carried out data collection, and K.S undertook data synthesis, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- European Commission. The demographic future of Europe- from challenge to opportunity. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2006 [accessed 2017 Aug 3]. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=URISERV%3Ac10160

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World alzheimer report 2013: journey of caring- an analysis of long-term care for dementia. London, United Kingdom: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2013 [accessed 2017 Aug 3]. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2013.pdf

- Koch S, Hägglund M. Health informatics and the delivery of care to older people. Maturitas. 2009;63:195–99. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.03.023.

- World Dementia Council. The world dementia council’s year-on report 2014/15. World Dementia Council; 2015 [accessed 2017 Aug 4]. https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/media.dh.gov.uk/network/353/files/2015/03/WDC-Annual-Report.pdf

- Zhang Y, Yu P, Shen J. The benefits of introducing electronic health records in residential aged care facilities: a multiple case study. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81:690–704. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.013.

- Cherry B, Ford EW, Peterson LT Long-term care facilities adoption of electronic health record technology: a qualitative assessment of early adopters’ experiences. Final report submitted to the Texas department of aging and disability services. Texas, United States: Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center; 2009 Oct 1 [accessed 2017 Aug 8]. http://www.nursinghome.org/pro/HIT/Content/HIT%20early%20adopters%20lessons%20learned_%20guide.2009.pdf.

- Hitt LM, Tambe P. Health care information technology, work organization, and nursing home performance. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 2016;69:834–59. doi:10.1177/0019793916640493.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety. Key capabilities of an electronic health record system. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003 [accessed 2017 Aug 8]. https://www.nap.edu/download/10781#

- Faxvaag A, Johansen TS, Heimly V, Melby L, Grimsmo A. Healthcare professionals’ experiences with EHR-system access control mechanisms.In: Moen A, Andersen SK, Aarts J, Hurlen P., editors. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 2011. http://ebooks.iospress.nl/publication/14239.

- Martin A, Hinds C, Felix M. Documentation practices of nurses in long-term care. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:345–52.

- Cheevakasemsook A, Chapman Y, Francis K, Davies C. The study of nursing documentation complexities. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12:366–74. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00596.x.

- O’connell B, Myers H, Twigg D, Entriken F. Documenting and communicating patient care: are nursing care plans redundant? Int J Nurs Pract. 2000;6:276–80. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172x.2000.00249.x.

- Munyisia EN, Yu P, Hailey D. The changes in caregivers’ perceptions about the quality of information and benefits of nursing documentation associated with the introduction of an electronic documentation system in a nursing home. Int J Med Inform. 2011;80:116–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.10.011.

- Yu P, Hailey D, Li H. Caregivers’ acceptance of electronic documentation in nursing homes. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:261–65. doi:10.1258/jtt.2008.080310.

- Alexander GL. An analysis of skin integrity alerts used to monitor nursing home residents. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2007;11–15.

- Maiden N, D’Souza S, Jones S, Muller L, Panesse L, Pitts K, Prilla M, Pudney K, Rose M, Turner I, Zachos K. Computing technologies for reflective, creative care of people with dementia. Commun ACM. 2013;56:60–67. doi:10.1145/2500495.

- Hanson A, Lubotsky Levin B. Mental health informatics. New York, United States: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Kohli R, Swee-Lin Tan S. Electronic health records: how can IS researchers contribute to transforming healthcare. Manag Inf Syst Q. 2016;40:553–73. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.3.02.

- Cherry BJ, Ford EW, Peterson LT. Experiences with electronic health records: early adopters in long-term care facilities. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36:265–74. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e31820e110f.

- European Commission. Communication from the commission to the European parliament, the council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. e-health action plan 2012-2020- innovative healthcare for the 21st century. Brussels, Belgium: European Commission; 2012 [accessed 2017 Aug 12]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/ehealth/docs/com_2012_736_en.pdf

- Meißner A, Schnepp W. Staff experiences within the implementation of computer-based nursing records in residential aged care facilities: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-14-54.

- Munyisia EN, Yu P, Hailey D. The effect of an electronic health record system on nursing staff time in a nursing home: a longitudinal cohort study. Med J Aust. 2014;7:285–93. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2014.2072.

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–53. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

- Cooper H. Synthesizing research: a guide for literature reviews. Thousand Oaks, United States: Sage Publications; 1998.

- Garets D, Davis M. Electronic medical records vs. electronic health records. Yes, there is a difference. A HIMSS analyticsTM white paper. Chiacgo, United States: HIMSS Analytics; 2006[accessed 2017 Oct 10]. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d36a/b22c2c9ecd0018fa1dff03394721e7b13423.pdf

- Häyrinen K, Saranto K, Nykänen P. Definition, structure, content, use and impacts of electronic health records: A review of the research literature. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:291–304. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.09.001.

- Fahey MJC. Culture change in long-term care facilities: changing the facility or changing the system?. J Soc Work Long Term Care. 2003;2:35–51. doi:10.1300/J181v02n01_03

- World Health Organization. Towards an international consensus on policy for long-term care of the ageing. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2000 [accessed 2017 Oct 10]. http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/long_term_care/en/

- Liberati A, Altma D G, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLOS Med. 2009;6. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;10:45–54. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Cherry B, Carter M, Owen D, Lockhart C. Factors affecting electronic health records adoption in long-term care facilities. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30:37–47.

- Cherry B, Carpenter K. Evaluating the effectiveness of electronic medical records in a long-term care facility using process analysis. J Healthc Eng. 2011;2:75–86. doi:10.1260/2040-2295.2.1.75.

- Florczak B, Scheurich A, Croghan J, Sheridan P, Kurtz D, McGill W, McClain B. An observational study to assess an electronic point-of-care wound documentation and reporting system regarding user satisfaction and potential for improved care. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58:46–51.

- Filipova A. Electronic health records use and barriers and benefits to use in skilled nursing facilities. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31:305–18. doi:10.1097/NXN.0b013e318295e40e.

- Meehan R. Electronic health records in long-term care: staff perspectives. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;36:1175–96. doi:10.1177/0733464815608493.

- Michel-Verkerke MB, Hoogeboom M. Evaluation of an electronic patient record in a nursing home: one size fits all? 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2012; Hawaii. Washington (DC): IEEE Computer Society; 2012.

- Yu P, Zhang Y, Gong Y, Zhang J. Unintended adverse consequences of introducing electronic health records in residential aged care homes. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:772–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.05.008.

- Rantz Mj, Alexander G, Galambos C, Flesner MK, Vogelsmeier A, Hicks L, Scott-Cawiezell J, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Greenwald L. The use of bedside medical record to improve quality of care in nursing facilities. Comput Inform Nurs. 2011;29:149–56. doi:10.1097/NCN.0b013e3181f9db79.

- Lindner Sa, Ben Davoren J, Vollmer A, Williams B, Landefeld CS. An electronic medical record intervention increased nursing home advance directive orders and documentation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1001–06. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01214.x.

- Jiang T, Yu P, Hailey D, Ma J, Yang J. The impact of electronic health records on risk management of information systems in Australian residential aged care homes. J Med Syst. 2016;40. doi:10.1007/s10916-016-0553-y

- Wang N, Yu P, Hailey D. Description and comparison of documentation of nursing assessment between paper-based and electronic systems in Australian aged care homes. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:789–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.05.002.

- Wang N, Yu P, Hailey D. The quality of paper-based versus electronic nursing care plan in Australian aged care homes: A documentation audit study. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84:561–69. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.04.004.

- Rantz Mj, Hicks L, Petroski GF, Madsen RW, Alexander G, Galambos C, Conn V, Scott-Cawiezell J, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Greenwald L. Cost, staffing and quality impact of bedside Electronic Medical Records (EMR) in nursing homes. J AM Med Dir Assoc. 2010;11:485–93. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2009.11.010.

- Fossum M, Ehnfors M, Svensson E, Hansen LM, Ehrenberg A. Effects of a computerized decision support system on care planning for pressure ulcers and malnutrition in nursing homes: an intervention study. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:911–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.05.009.

- Marier A, Olsho LE, Rhodes W, Spector WD. Improving prediction of fall risk among nursing home residents using electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform. 2016;23:276–82. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocv061.

- Chau S, Turner P. Utilisation of mobile handheld devices for care management at an Australian aged care facility. Electron Commer Res Appl. 2006;5:305–12. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2006.04.005.

- Greenes RA. Clinical decision support: the road ahead. Boston, United States: Elsevier; 2007.

- Tharmalingam S, Hagens S, English S. The need for electronic health records in long-term care. Building capacity for health informatics in the future. In: Lau F, Bartle-Clar J, Bliss G, Borycki E, Courtney K, Kuo A., editors. Building capacity for health informatics in the future. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IOS Press; 2017. http://ebooks.iospress.com/volumearticle/46185

- Phillips K, Wheeler C, Campbell J, Coustasse A. Electronic medical records in long-term care. J Hosp Mark Public Relations. 2010;20:131–42. doi:10.1080/15390942.2010.493377.

- Gheorghiu B, Hagens S. Measuring interoperable EHR adoption and maturity: a Canadian example. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16.

- Jeon Y-H, Govett, J, Low L-F, Chenoweth L, McNeill G, Hoolahan A, Brodaty H, O’Connor D. Care planning practices for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential aged care: A pilot of an education toolkit informed by the Aged Care Funding Instrument. Contemp Nurse. 2013;44:156–69. doi:10.5172/conu.2013.44.2.156.

- Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice. J Dev Effect. 2012;4:409–29. doi:10.1080/19439342.2012.710641.

- Brandeis GH, Hogan M, Murphy M, Murray S. Electronic health record implementation in community nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8:31–34. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2006.09.013.

- Wang T, Biedermann S. Utilization of electronic health records systems by long-term care facilities in Texas. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2012;9:1g.