ABSTRACT

Social isolation and loneliness are associated with negative health outcomes, physical as well as cognitive. Information and communication technology (ICT) can be effective tools for preventing and tackling social isolation and loneliness among older people. Our objective was to evaluate the feasibility of the Fik@ room, a web platform for social interaction designed for older people. A mixed methods design was applied, where both quantitative and qualitative data were collected during a 12-week period (n = 28, Md age 74). Experiences of loneliness were reduced using the Fik@ room. The results highlight the feasibility issues surrounding the recruitment process, adoption, pattern of use, usability, support service, and technical infrastructure. In particular, the importance of offering ICT solutions with few technical issues, and to provide easily accessible and appropriate support. The Fik@ room is a feasible tool for older people to develop new friendships, reduce loneliness, and grow their social networks. However, it is not a communication option that fits all. The results offer a compilation of feasibility issues that can serve as an inspirational guide in the design and implementation of similar technologies.

Introduction

Social isolation and loneliness are growing public health concerns in our aging society. The reasons are multifactorial, relating to for example, age-related physical and cognitive changes and losses,Citation1,Citation2 reduced intergenerational living, and greater social and geographical mobility.Citation3 Moreover, the number of older people affected by social isolation and loneliness is increasing because of the worldwide aging population.Citation4 At the same time, the rapid advancements in information and communication technologies (ICTs) offer increased opportunities for social connectedness, which has led to a growing interest in investigating how ICTs might be supportive in reducing the negative impacts of social isolation and loneliness among older people.Citation5

Although the experiences of social isolation and loneliness occur across the life span, previous research proposes that people become lonelier over time in old age.Citation6 Half of individuals aged over 60 are assessed as being at risk of social isolation, and a third of them will experience some degree of loneliness later in life.Citation7 Social isolation is often defined as the objective lack or paucity of social contacts with family, friends, or the wider community, while loneliness is a subjective negative feeling associated with one’s perceived lack of social network or specific desired companion.Citation3 A growing body of evidence shows that older people are particularly vulnerable to social isolation and loneliness, and the consequences are extensive. Socially isolated and lonely older people are more likely to experience physical decline, morbidity, and early mortality. They are also more prone to suffer from cognitive health problems like depression and dementia and tend to have a higher risk of suicide.Citation1,Citation4,Citation8 Subsequently, targeting social isolation has become a focus area for policy and practice.Citation9

The use of ICTs can help maintain social contacts with family members and the surrounding society.Citation10–12 Several studies have reported that ICT tools can effectively tackle social isolation and loneliness among older people.Citation5,Citation8,Citation9,Citation13 However, more studies are needed to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of ICT interventions for older people in reducing social isolation and loneliness.Citation9,Citation14,Citation15

When using technology-enabled products and services, older people tend to struggle more because of low digital literacy or impairments.Citation16 Individuals’ digital skills vary considerably; with increasing age, both literacy and access to ICT decrease.Citation17 However, older people are a heterogeneous group, and many have a wide knowledge of ICTs and an interest in gaining more skills in this area.Citation18 Among older people between 66 and 75 years in Sweden, the internet use is 91%, compared with 58% among those 76 years and older.Citation19 The same age group – 76 years and older – accounted for the highest increase in internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.Citation20 Nevertheless, when addressing digital literacy and the use of ICTs, age-related changes need to be considered. Physical and cognitive losses, with impaired motor skills, might make it difficult to click on small virtual bottoms in an interface. Visual impairment can make viewing details difficult, the ability to perceive colors and contrasts changes with age, and hearing ability will decline over time.Citation21 This must be addressed in the design of ICTs. The design and research process call for the inclusion of the users, in this case older people, which is essential if digital technology is to fulfill the promise of improving well-being.Citation22 In addition, the design must be grounded in an understanding of how older people manage their social relationships and deal with loneliness.Citation23

In response to the extensive consequences of social isolation and loneliness, we developed a web platform for social connectedness. The web platform – called the Fik@ room – is a research-based digital solution for social interaction among older people experiencing social isolation and/or loneliness. To the best of our knowledge, in most existing ICTs for social interaction, it is assumed that the user has an existing social network and can use and handle the complexity of such sites (e.g., Facebook and Instagram). The Fik@ room is designed to be a secure, easy-to-use web platform where older people can meet and connect in a safe digital environment. A user-centered approach guided the development of the web platform, which was based on a codesign process between older people, stakeholders in health and social care, researchers in health and welfare and information design, and IT experts (manuscript in progress).

Table 1. Data collection at baseline, halfway (6-week), and at the end of the study period (12-week).

Table 2. Characteristics of the participants

Table 3. Evaluation of outcomes: Experienced loneliness and social network at baseline, at 6-week follow-up, and at 12-week follow-up.

Table 4. Adoption, pattern of use, and usability at the 6-week and 12-week follow-up.

Table 5. Identified feasibility issues to be addressed prior to the planned pilot study and future solutions.

Hence, the objective of the current study was to evaluate the feasibility of the Fik@ room regarding the outcomes of experienced loneliness and social networks, acceptability (adoption, pattern of use, usability), resources (support service, technical infrastructure), and recruitment of participants.

Materials and methods

Design

A feasibility study with a concurrent mixed methods design, including both quantitative and qualitative data.Citation24

Participants and recruitment

The study was conducted in a mid-east region of Sweden. The participants were recruited by purposive sampling. Information about the study, including contact details, was announced in municipal meeting places, through contacts with local retirement organizations, advertisements in local newspapers, and on Facebook. The inclusion criteria were (a) age 65+, (b) experience of social isolation and/or loneliness, and (c) living within the geographical area (to receive the tablet and for personal support on site, if necessary). Prior to the start of the study, 37 older people had registered interest in participating in the study. All of them were invited, and 30 accepted. Four dropped out during the first two weeks, whereupon two new participants were recruited through recommendations from the study participants. Twenty-eight participants completed the study.

The web platform

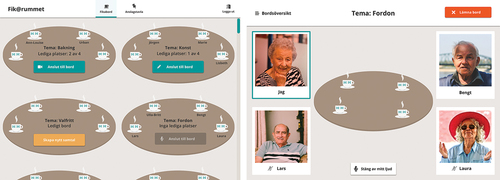

The name of the web platform, the Fik@ room, was suggested by the older people who participated in previously conducted workshops (manuscript in progress); they associated the web platform with the coffee breaks at their former workplace, where they sat down at a coffee table and were socially active in conversations. The features of the Fik@ room are grounded in the articulated needs and desires of the older people in the aforementioned workshops. The esthetical qualities and functionalities include aspects of easy self-explanatory navigation properties, choice of contrasts, and other information design specifics essential according to the target group. The Fik@ room consists of digital coffee tables for up to four persons at each table and opportunities to start conversations in video, voice, or chat on topics of their own choice. There was also a bulletin board (launched halfway into the study) where the participants could post messages and schedule meetings either within the Fik@ room or at a physical location (see ).

The intervention

During the 12-week study period, the participants borrowed a tablet (android) where the Fik@ room was preinstalled. The participants received a three-page manual, including screenshots and descriptions of the features of the web platform. Information was also given verbally when the tablets were delivered. Most participants already had access to the internet (n = 26), and those who did not (n = 4) received a tablet with a 4 G connection. The use of the web platform was restricted to the participants who received unique usernames and passwords.

The participants were advised to attend the Fik@ room at three specified times every week: Mondays and Fridays at 3 p.m. and Wednesdays at 10 a.m. The predetermined times intended to increase the possibility that as many participants as possible would be logged in simultaneously. In addition to these occasions, they were encouraged to use the Fik@ room whenever they wanted. During the 12-week study period, the participants had access to a support service provided by the researchers, both by telephone and e-mail, in case of difficulties with the interface or other issues.

Data collection

The study was performed between September and December 2020. Data were collected at baseline, halfway through the intervention (at 6 weeks), and after the intervention (at 12 weeks). The outcomes of the possible effect were loneliness and social networks. The other considered objectives were acceptability, resources, and recruitment.Citation25 Acceptability refers to the adoption, pattern of use, and usability; resources refer to the support service during the study and the technical infrastructure requirements; and recruitment refers to the recruitment of study participants (see ).

Quantitative 6-week and 12-week evaluation

The UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3)Citation26,Citation27 was used to evaluate the participants’ self-reported loneliness. The UCLA Loneliness Scale includes 20 items, with scores ranging from 1 to 4 corresponding to never, rarely, sometimes, and often, respectively. Eleven of the questions are negatively worded, and nine of the questions are positively worded, which is why the scores of the latter questions were reversed. A higher total score indicates a higher degree of loneliness.

The social network questionnaire was used to evaluate the number of social activities and contacts and satisfaction with these. The questionnaire was constructed by the research team, inspired by Larsson et al.Citation28 and Rudman et al.Citation29 The 16-item questionnaire includes questions regarding the frequency of activities on and outside the internet (scores ranging from 1 corresponding to every day and 4 to not at all); the satisfaction with the social activities (scores ranging from 1 corresponding to very satisfied and 4 to very dissatisfied); the number of acquaintances, friends, or relatives the individual can interact with in various situations (scores ranging from 1 corresponding to no one and 5 to more than 10; the satisfaction with the number of acquaintances, friends, or relatives (scores ranging from 1 corresponding to very satisfied and 4 to very dissatisfied); and, finally, the satisfaction with existing social networks on and outside the internet (scores ranging from 0 corresponding to not at all and 10 to a very high degree). A higher total score indicates larger and more satisfaction with one’s social networks.

The feasibility questionnaire was used to evaluate the adoption (frequency) of the web platform, the pattern of use, the usability, the technical infrastructure, and the support service provided during the study. The feasibility questionnaire comprised a quantitative and qualitative part. The quantitative part of the questionnaire included 12 questions at the 6-week follow-up and 14 items at the 12-week follow-up with numerical rating (NRS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (0 corresponding to not at all and 10 to a very high degree).

Qualitative narratives

The feasibility questionnaire was also used to evaluate qualitative aspects of using the web platform, and suggestions for improvement in the 6-week and 12-week evaluation. The questionnaire included 3 open-ended questions about the participants’ experiences of using the web platform.

Diaries displayed the participants’ experiences of using the web platform.

A logbook showed the researchers’ documentation on recruitment and issues submitted by the participants to the support service, either via telephone or e-mail, and how these were solved.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Descriptive and inferential statistics of the quantitative data were calculated. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyze the differences between two subgroups, and Friedman test was used to analyze the differences between three or more subgroups. Missing values were 9% and at random, suggesting no bias, and multiple imputations of the missing values were performed.

The overall significance level was set at p≤ .05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 for Windows.

Qualitative data

A thematic analysis was applied based on a mixed approach (inductive and deductive), inspired by Neves et al.Citation8 All responses and documentation from the participants’ diaries (8 diaries), the logbook (12 pages document), and the open answers in the feasibility questionnaire (5 questions) were collated and regarded as the unit of analysis. The categories emerged from the collated data but also from a priori themes related to feasibility objectives (evaluation of outcomes, acceptability, and resources).

Ethical guidelines

The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could end their participation whenever they wished. The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dno 2019–06269) and conforms to the principles outlined in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki.Citation30 Written informed consent was obtained prior to the start of the study.

Results

The results include the recruitment of the participants, experienced loneliness and social networks and the considered objectives: adoption, pattern of use, usability, and support service and technical infrastructure. Quotations from the qualitative analysis are provided to elucidate the outcomes.

Recruitment

Of the 30 participants who were initially recruited to the study, four dropped out during the first two weeks. The reasons for dropping out were not explicitly stated, but two participants stated that they had realized that this type of forum was not for them. Two new participants were recruited to the study, resulting in a total of 28, all of whom were living in ordinary housing. Their characteristics are presented in .

Experienced loneliness and social networks

The results in the UCLA Loneliness Scale showed that experienced loneliness decreased at the 6-week follow-up and increased at the 12-week follow-up but to a lesser extent compared with the loneliness experienced at baseline (see ). The results in the social network questionnaire showed that the overall frequency and satisfaction with social networks increased at the 6-week follow-up but decreased at the 12-week follow-up to an even lower level than at baseline. The questions in the feasibility questionnaire that addressed loneliness and social networks in relation to the use of the Fik@ room displayed an increasing satisfaction with the impact on experienced loneliness and one’s social network. There was a significant improvement between the 6-week and 12-week follow-up in all questions. The highest median values were obtained for the questions on whether using the Fik@ room is a good way to reduce the experience of loneliness, which increased from 5.3 to 8 on the NRS scale between the 6-week and 12-week follow-up, and whether the Fik@ room is a good way to increase one’s social network, which increased from 5 to 7 (see ).

According to the qualitative narratives, the participants’ experiences of loneliness and social networks were grouped into three categories: From acquaintances to deepening friendships, Difficulties in finding a sense of companionship and topic of conversation, and Various needs and expectations.

From acquaintances to deepening friendships. During the first weeks, many participants expressed that they had met several interesting and nice people, as exemplified in the following three quotations: “This way of getting in touch with other people is really great” (P23). “It’s fun when the participants live in different places” (P7). “I have participated in my first ‘fika’ and it was very nice.” (P20). Eventually, a transformation of the participants’ relationships seemed to occur. The conversations seemed to deepen; many expressed that they enjoyed speaking to those who they had gotten to know more, as in the following quotations: “It’s nice to chat with those you have got to know a little bit more. It becomes like the break room at your former working place” (P7). “Everyone had met at previous Fik@ tables, a sense of belonging emerged. Everyone contributed and it felt good with human interaction” (P2). “The Fik@ room meetings becomes more meaningful the more we meet. It’s more fun when we start to get to know each other” (P11).

Difficulties in finding a sense of companionship and topic of conversation. Not all participants were comfortable interacting with unknown people: “It is difficult to find a sense of companionship and find topics of conversation with strangers” (P27). “The Fik@ room is a mixture of participants with extremely different interests and needs” (P31). One difficulty was when a single participant talked continually and did not let others into the conversation. However, a more common perception was that it occasionally could be difficult to find a topic of conversation at specific Fik@ tables or that the conversation simply did not interest the person: “It was hard sometimes, when the conversation was about politics, then I left the table” (P5). “We did not find any topic that got the conversation going, it was not so fun” (P11).

Various needs and expectations. Most of the participants expressed satisfaction and positive views of their participation in the Fik@ room. They appreciated the initiative and believed that the Fik@ room could be a useful tool for enhancing social networks. Other positive views are exemplified in the following quotations: “I feel that my expectations have been exceeded. I have met many people that I would like to talk to more and meet physically, although COVID-19 has kept us from physical meetings … I’m feeling hope for the day when I no longer will be able to go outside” (P23). “It’s exciting to talk to different people. I would like to continue. I will miss the table talks” (P7). However, a few participants expressed that this type of forum was probably not for them. One reason was that they had other social contacts and were not lonely at the moment. One participant’s main reason for joining the study was to alleviate the loneliness of other isolated people.

Adoption

The adoption of the intervention was assessed based on the frequency of use. Most of the participants stated that they attended the Fik@ room 2–3 times/week, both at the 6-week and 12-week follow-up (see ). Reasons for not attending were illness, doctor visits, or other activities.

The participants had different preferences regarding suitable days and hours during the week. Several participants requested additional Fik@ room meetings, as stated in the following quote: “ … maybe some time Saturday or Sunday when I feel lonely, I have no other activities then” (P21). The fixed Fik@ room meetings were perceived as limiting but also an advantage because they gave some structure to the weeks and something to look forward to, as stated by two participants: “ … what I find limiting … is to be controlled by specific times, but it’s also an advantage” (P23). “Good initiative! Since I am very isolated in the current pandemic, it was nice to have some fixed points in the weeks” (P15).

Pattern of use

Video conversations were the most used form of communication (see ). At the 12-week follow-up, only one participant preferred voice conversations and declared that “I was the only one who wanted to have voice conversations. I had to use video to be able to participate” (P13). Examples of comments related to video conversations are: “The conversations become more alive with gestures and faces” (P28). “Since we don’t know each other, it is better to see who you are talking to” (P22). Another aspect was that when using video conversations, it was easier to avoid interrupting each other.

Most of the participants reported that they attended the Fik@ room for about one hour each time (see ). The topics of conversation varied greatly, from cooking, hobbies, motorcycles, and movies to discussions about politics, crime, and computer technology.

Usability

The usability of the intervention, here referring to navigation, connecting/creating conversations (video, voice, or chat), and writing messages on the bulletin board are summarized in . The median values for most items were between 7 and 9.8 (10-graded scale, where 0 corresponds to not at all and 10 to a very high degree). The exception was the question on creating a chat conversation, a rarely used function, which generated the lowest score (Md = 6). In the item regarding the ease of creating new video calls, the median increased between the 6-week and 12-week follow-up (8.1–8.8). The median value decreased in the other four items, with a significant difference regarding the ease of connecting to calls (p = .032) (see ).

Support services and technical infrastructure

The support service received 70 questions/errands (64 calls and 6 e-mails) during the 12-week study. In addition, there were other matters that were not directly linked to usability issues. The questions/errands posed to the support were mainly related to the following: 1. Wi-Fi/internet connections, surf access, and login issues; 2. the tablets’ audio/sound and image quality; 3. issues regarding connecting to or leaving a Fik@ table; and 4. reinstalling an update of the Fik@ room.

Various problems with Wi-Fi were the most common reason for contacting the support service. These problems were particularly common at the start but also occurred now and then during the study period. One problem was that those who had received a tablet with 4 G soon ran out of surf because the video calls required a high resolution. Various problems with logging in to the Fik@ room also occurred. Many of these were related to internet access, but sometimes, the reasons were unclear. In total, the support received 32 questions/errands about Wi-Fi, 4 G connection, and log in (the same person could call in several times).

The second most common reason for support was related to the quality of audio/sound or image during the conversations. These issues might be associated with the tablets, the features of the Fik@ room, or the internet connection. Some participants had a hard time hearing what was said, while others commented on voice delays, which increased the risk of interrupting each other during the conversations. Also, the image/picture was sometimes blurry. A few participants stated that it was easier to have two or three people in the conversations instead of four, as one participant described: “It’s difficult to be four people in the conversations, it requires respect from each participant to listen and let everyone speak” (P23). The support received 15 questions/errands on the quality of audio/sound or image.

Difficulties with connecting to or leaving a Fik@ table was the third most common reason for contacting support. The reported problem was that the participants were unable to leave a Fik@ table because the image “froze.” In all, the support service received 12 questions/errands on connecting to or leaving the Fik@ table.

The fourth most common reason for contacting support concerned the reinstallation of an update of the Fik@ room. In all, the support service received seven questions/errands on the reinstallation of an update.

A few additional views were expressed by the participants concerning the tablet itself, for example, difficulties reaching the on/off button, that the tablet shut down too fast, or difficulties with the keyboard. In all the above cases except for two, the problems could be solved by telephone, for example, by restarting the tablet. In two cases, the support service had to be provided at the participants’ homes.

Discussion

The results suggest that the Fik@ room intervention – a web platform for social interaction – is a feasible tool for older people to develop new friendships, to reduce the experience of loneliness, and to increase one’s social network. The questions about whether the Fik@ room is a good way of increasing social networks and reducing the experience of loneliness scored 7 and 8 (0–10 scale), respectively. Also, the participants’ relationships seemed to undergo a transformation over time during the Fik@ room meetings, from being gatherings with nice people around a Fik@ table to becoming deepening conversations with new friends. Previous studies have suggested that older people use ICTs primarily to strengthen existing close tiesCitation10 and that they prefer to maintain current networks rather than building new ones.Citation8,Citation13 The current study suggests that the Fik@ room is also a feasible tool for developing new relationships, which is an encouraging outcome, when considering those who may lack family and friends. One previously described risk of only relying on communication with relatives is that it is based on the relatives’ involvement. If relatives are not involved or reply, the experience of social isolation and loneliness might even increase in older people.Citation31

The results are more contradictory when evaluating social networks and loneliness in general. Whereas the frequency and satisfaction with social networks increased halfway into the study and experienced loneliness decreased, the positive trend reversed at the 12-week follow-up, and for social networks, this dropped to an even lower level than at baseline. However, the prevailing COVID-19 pandemic makes it difficult to interpret the results. Stricter restrictions were launched halfway into the study, which may have affected the outcomes. Or perhaps the participants’ answers were affected by the fact that the study had come to an end, which would mean their social network would be reduced. However, because this is a feasibility study and not a randomized controlled trial, it is not intended to measure effects. Nor can conclusions about possible effects be drawn given the small sample size. Still, the results indicate a slight positive trend when it comes to loneliness, displaying an overall reduction in experienced loneliness between the baseline and 12-week follow-up. In contrast to our findings, previous studies have found positive effects regarding social isolation, while the effects on loneliness have been more inconclusive.Citation9,Citation32

Despite a belief that the Fik@ room could be a feasible tool to increase older people’s social network and reduce the experience of loneliness, it is important to be aware of that the technology is not suitable for everyone, as shown in the present findings. Some of the participants expressed that this type of forum probably was not really for them and gave different reasons for this. Some previously identified barriers influencing the usability of tablets and similar devices are motivation and physical ability and cognition.Citation21 In addition, the results also point to the fact that not everyone feels comfortable interacting with unknown people. Therefore, as suggested by Chen and Schulz,Citation9 strategies are needed to identify those older people who can most benefit from ICT use in reducing social isolation and loneliness. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Older people experience social isolation and loneliness for different reasons and in different ways.Citation33 The individuality of the experiences is important because this may cause difficulty in the delivery of standardized interventions.Citation7

The results show several feasibility issues that need to be addressed. One issue is the challenge of recruiting participants who had experiences of social isolation and/or loneliness. Similar challenges have been described in previous studies, for example, in a systematic review conducted by Dickens et al.,Citation15 who found that only 12 out of 32 (38%) studies explicitly targeted people identified as being socially isolated or lonely. More recently, Casanova et al.Citation34 refer to recruitment strategies as one of the main limitations in studies on the effect of ICTs and social networking on older people. One possible explanation could be the prevailing stigma attached to social isolation and loneliness.

Another feasibility issue concerns adoption, which was evaluated in the current study by the frequency of attendance in the Fik@ room. There was a tendency of reduced attendance in the Fik@ room meetings, from 23 attending at least once a week (6-week follow-up) to 19 (12-week follow-up). There are several possible explanations for this. Some participants may, as previously pointed out, have discovered that this way of communicating did not suit them. Technical problems could be another reason. Reported problems were found to be related to, for example, Wi-Fi/internet connections, surf access, login issues, and the tablets’ audio/sound and image quality. The participants received support throughout the study by telephone and e-mail. Despite this, some of the participants seem to have experienced technical difficulties. This occurred even though their digital skills could be considered as high because 96% of them were using smartphones and 93% used computers/laptops. The findings correspond to what Neves et al.Citation31 found in a similar feasibility study conducted among older people in residential care; even those with higher levels of digital literacy needed support in using an iPad-based communication app. The findings emphasize the importance of providing adequate support. Support is especially important when starting the use of a tablet.Citation35 However, our findings suggest that the experienced difficulties were not related to the specific features of the Fik@ room. The participants found it easy to navigate in the Fik@ room (score 9 after 12 weeks on a 0–10 scale) and easy to connect to calls (score 8.8 after 12 weeks on a 0–10 scale). Nevertheless, there was a decrease in the experienced ease in creating new voice or chat conversations. A likely explanation for this would be that voice and chat conversations were hardly used at all. Video conversations were the far most frequently used means of conversation, which may be explained by the fact that the conversations, at least initially, took place with unknown people. Moreover, seeing each other makes it easier to follow the conversation and avoid interrupting each other.

A compilation of the feasibility issues is presented in

Strengths and limitations

A strength in the current web platform is that the Fik@ room is a safe and secure place, protected from computer intrusion, advertisement, and unwanted user groups. Also, the users do not have to build their own contact network. Furthermore, in contrast to existing web platforms for social interaction, the older people have themselves been involved in the development of the Fik@ room’s user interface. Their articulated needs were then applied by designers and programmers in collaboration with the researchers in the project. This led to a unique interface design, which is more user friendly and adapted to the older people’s age-related impairments, than the products available on the market, in terms of contrast effects, color choices and orientation structures.

However, there are also several limitations. This was a small-scale study and thus the results cannot be generalized to older people in general, or to the feasibility of other similar web platforms. Moreover, one of the questionnaires was constructed by the authors because no scale was found that matched our purpose of evaluating social networks. The UCLA,Citation36 on the other hand, is a valid and reliable scale for evaluating loneliness among older people in intervention studies. Overall, our mixed data allowed us to explore patterns of use, usability, and resources, as well as outcomes, before a pilot study and, eventually, an RCT and implementation. However, the level of adoption could only be roughly assessed because the participants were recommended to participate in the Fik@ room at least on the three specified days per week. We cannot be sure that the frequency of participation otherwise would have been the same.

The participants’ characteristics may have affected the results. A majority (57%) had an academic education. Previous research shows that older people with a higher education level are more likely to adopt technological devices than those with a lower education level.Citation37 Most of the participants were women (86%), which is consistent with the demographic distribution of older people. We also found that the participants had joined the study for different reasons, not always because they experienced social isolation/loneliness. However, the prevailing COVID-19 situation exacerbated the challenges of worsening social isolation and loneliness for all, including our participants. Hence, it can be assumed that most of the participants experienced social isolation and/or loneliness, at least in some sense.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings suggest that the Fik@ room is a feasible ICT tool for older people to develop new friendships, increase one’s social network, and reduce the experience of loneliness. However, it is not a communication option that fits everyone. The involvement of care professionals in the introduction and support service would increase the chances of reaching potential users who would benefit from using the web platform.

The most prominent feasibility issues to consider are related to the technical infrastructure and support services, findings that emphasize the importance of offering self-instructing ICT solutions with few technical hitches. It is also essential to provide easily accessible and appropriate support services. These measures are justified to allow as many older people as possible to benefit from using the Fik@ room, also regarding different age-related changes and losses. Recruitment was another prominent feasibility issue, that is, the challenge in recruiting the intended target group.

The findings offer a compilation of feasibility issues that can serve as an inspirational guide in the design and implementation of similar technologies.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to the participants in the study and who shared their experiences and perceptions with us. We also want to thank members of the Prolonged Independent Living (PrILiv) research group at Mälardalen University and especially research assistant Karin Jonasson.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, Caan W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157–71. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035.

- Savikko N, Routasalo P, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE, Pitkälä KH. Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41(3):223–33. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2005.03.002.

- Valtorta N, Hanratty B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. 2012;105(12):518–22. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.120128.

- Alpert PT. Self-perception of social isolation and loneliness in older adults. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2017;29(4):249–52. doi:10.1177/1084822317728265.

- Baker S, Warburton J, Waycott J, Batchelor F, Hoang T, Dow B, Ozanne E, Vetere F. Combatting social isolation and increasing social participation of older adults through the use of technology: a systematic review of existing evidence. Aust J Ageing. 2018;37(3):184–93. doi:10.1111/ajag.12572.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Goldberg S. Loneliness in old age: longitudinal changes and their determinants in an Israeli sample. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(6):1160–70. doi:10.1017/S1041610209990974.

- Landeiro F, Barrows P, Nuttall Musson E, Gray AM, Leal J. Reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e013778. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013778.

- Neves BB, Franz RL, Munteanu C, Baecker R. Adoption and feasibility of a communication app to enhance social connectedness amongst frail institutionalized oldest old: an embedded case study. Inf Commun Soc. 2018;21(11):1681–99. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348534.

- Chen YRR, Schulz PJ. The effect of information communication technology interventions on reducing social isolation in the elderly: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(1):e18. doi:10.2196/jmir.4596.

- Cotton SR, Anderson WA, McCullough BM. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e39. doi:10.2196/jmir.2306.

- Delello JA, McWhorter RR. Reducing the digital divide: connecting older adults to iPad technology. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;36(1):3–28. doi:10.1177/0733464815589985.

- Joe J, Hall A, Chi NC, Thompson H, Demiris G. IT-based wellness tools for older adults: design concepts and feedback. Inform Health Soc Care. 2018;43(2):142–58. doi:10.1080/17538157.2017.1290637.

- Khosravi P, Rezvani A, Wiewiora A. The impact of technology on older adults’ social isolation. Comput Human Behav. 2016;63:594–603. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.092.

- Chipps J, Jarvis MA, Ramlall S. The effectiveness of e-interventions on reducing social isolation in older persons: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(10):817–27. doi:10.1177/1357633x17733773.

- Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–22. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-647.

- Lee C, Coughlin JF. PERSPECTIVE: older Adults’ adoption of technology: an integrated approach to identifying determinants and barriers. J Prod Innov Manage. 2015;32(5):747–59. doi:10.1111/jpim.12176.

- Olsson T, Samuelsson U, Viscovi D. At risk of exclusion? Degrees of ICT access and literacy among senior citizens. Inf Commun Soc. 2019;22(1):55–72. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1355007.

- Betts L, Hill R, Gardner SE. “There’s not enough knowledge out there”: examining older Adults’ perceptions of digital technology use and digital inclusion classes. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;38(8):1147–66. doi:10.1177/0733464817737621.

- The Swedish Internet Foundation (2018). Svenskarna och internet 2018. [ accessed 2021 07 20] https://internetstiftelsen.se/docs/Svenskarna_och_internet_2018.pdf

- The Swedish Internet Foundation (2020). Svenskarna och internet 2020. [ accessed 2021 07 20] https://svenskarnaochinternet.se/app/uploads/2020/12/internetstiftelsen-svenskarna-och-internet-2020.pdf

- Wildenbos GA, Peute L, Jaspers M. Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: a literature based framework (MOLD-US). Int J Med Inform. 2018;114:66–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.012.

- Mannheim I, Schwartz E, Xi W, Buttigieg SC, McDonnell-Naughton M, Wouters EJ, Van Zaalen Y. Inclusion of older adults in the research and design of digital technology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3718. doi:10.3390/ijerph16193718.

- Wherton J, Sugarhood P, Procter R, Greenhalgh P, editors. 2015. Designing Technologies for social connection with older people Prendergast D, Chiara G (Eds.). Aging and the digital life course. 107–24. Berghan books.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. CA: Sage.25: Thousand Oaks; 2007.

- Orsmond GI, Cohn ES. The distinctive features of a feasibility study: objectives and guiding questions. OTJR: Occupation Participation Health. 2015;35(3):169–77. doi:10.1177/1539449215578649.

- Russell DW. UCLA loneliness scale (Version 3): reliability, Validity, and Factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2.

- Steen I. Frågor om ensamhet [Questions about loneliness]. Svensk översättning av UCLA Loneliness Scale. Av Kammarkollegiet auktoriserad translator från engelska till svenska [Swedish translation of the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Authorized Trans Eng Swedish Author Swedish Chamber Com. 2020.

- Larsson E, Nilsson I, Larsson Lund M. Participation in social internet-based activities: five seniors’ intervention processes. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(6):471–80. doi:10.3109/11038128.2013.839001.

- Rudman A, Hutell D, Gustavsson P. Sjuksköterskors karriärvägar och hälsoutveckling de första åren efter utbildning. Enkät använd vid LUST-projektets datainsamling för X2004-kohorten fem år efter examen [Nurses’ career paths and health development in the first years after education. In: Questionnaire used in the LUST project’s data collection for the X2004 cohort five years after graduation]. Karolinska Institutet; 2010.

- World Medical Association. WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. 2018. [ accessed 2021 07 20] https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Neves BB, Franz R, Judges R, Beermann C, Baecker R. Can digital technology enhance social connectedness among older adults? A feasibility study. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;38(1):49–72. doi:10.1177/0733464817741369.

- Shah SGS, Nogueras D, van Woerden HC, Kiparoglou V. The COVID-19 Pandemic: a pandemic of lockdown loneliness and the role of digital technology. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e22287. doi:10.2196/22287.

- Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):129. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6.

- Casanova G, Zaccaria D, Rolani E, Guaita A. The effect of information and communication technology and social networking site use on older People’s well-being in relation to loneliness: review of experimental studies. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e23588. doi:10.2196/23588.

- Tsai HYS, Shillair R, Cotten SR. Social support and playing around: an examination of how older adults acquire digital literacy with tablet computers. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36(1):29–55. doi:10.1177/0733464815609440.

- Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Aging Soc. 2005;25(1):41–67. doi:10.1017/S0144686X04002594.

- Vroman KG, Arthanat S, Lysack C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults’ dispositions toward information communication technology. Comput Human Behav. 2015;43:156–66. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.10.018.