ABSTRACT

This study analyses a prototypical ad for countering reactive co-radicalisation, a radicalisation process that occurs in one population segment as a response to radicalisation perceived in another population segment. We employ a multi-representational approach to develop an ad-based solution for undermining dehumanisation of perceived “others”. This “re-humanisation” process is illustrated within the context of the “Mad Mullah” stereotype, a traditional target of reactive co-radicalisation used by right-wing extremists. Using a combination of Critical Visual Theory (CVT) and Dimensional Qualitative Research (DQR), we reveal the structuration of empathy embedded within the re-humanised image of the Muslim “other” in the ad. This contributes to current understanding of attitudinal inoculation by explaining the importance of cultivating empathy in the process of re-humanising the dehumanised “other”.

Introduction

In recent years, officials in several countries have identified right-wing extremism (RWE) as a growing threat to domestic safety and security. The US Department of Homeland Security recently stated that “domestic violent extremism poses one of the most significant terrorism-related threats to the United States” (US Homeland Security Citation2022, 4). Germany’s interior minister similarly claimed that RWE remains “the greatest threat” to German security (German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community Citation2020); and the UK Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee has identified RWE as a clear danger to domestic British security (ISC Citation2022). These cases are not isolated; right-wing extremist groups have increasingly emerged and grown in several parts of the world, in part due to the perceived radicalisation of outgroups to whom they attribute danger (Pratt Citation2015). The proliferation of this process – dubbed reactive co-radicalisation (RC-R) – begs the question as to how policymakers can prevent violence on the part of RWE groups who feel they must counter the radicalisation of “enemy” groups that they believe pose a threat to those they claim to protect.

One discipline that has been largely absent from debates on counter-radicalisation and its implementation, despite its undisputed import, is marketing (El-Said Citation2015; Lieber Citation2020). Compounding problems caused by marketing’s scarcity in the counter-radicalisation literature is a growing uncertainty about the efficacy of counter-narrative campaigns against extremism (Carthy et al. Citation2020), including those that draw on principles of marketing and advertising. In the context of right-wing C-RC, marketing has an additional challenge to overcome the “abject representations” of terrorists more generally in the news media post 9/11, particularly those pertaining to Arabs (Nashef Citation2011), and the concomitant use of Islamophobic tropes as a common ground for legitimising right-wing sentiment (Hafez Citation2014).

In this study, we present an interpretative case study in which we analyse a prototypical ad comprising multi-associative empathy designed to humanise a perceived outgroup (i.e. the “other”). Leveraging the principles of advertising, and peace marketing (Dean and Shabbir, Citation2019) for countering RC-R, provides a new approach to address the problem of inter-group hostility intrinsic to violent extremism. Advertising is characterised by indirect appeals that can foster positive vicarious learning (Bandura Citation1965). In the context of RC-R, advertising can promote this kind of learning by facilitating the observation of positive interactions between ingroups and outgroups. Originally proposed by Allport (Citation1954), the potential for inter-group contact to reduce inter-group prejudice, or inter-group contact theory (Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006), has become “enshrined in policymaking all over the globe” (Everett, Citation2013, 1). Communications enabling this type of observation helps mediate inter-group anxiety effects, present in direct inter-group contact (Wright et al. Citation1997), as in radicalisation contexts (Chaudhuri and Buck Citation1997). By fostering inter-group contact, or enabling its mere imagination, ads can therefore foster peace marketing (Dean and Shabbir, Citation2019) by helping to bridge inter-group hostilities, an effect more pronounced when ads foster a sense of appreciation for the “other” (Oliver and Bartsch Citation2011). Despite extant research to this effect, our current understanding of how to leverage advertising for building bridges between groups that have dehumanised one another is lacking (Edlins and Dolamore Citation2018).

Central to our study is the identification of an ad-based multi-representational approach to humanise the “other”. Through our analysis, we develop an image-formation process demonstrating how the dehumanising worldview of radicalised individuals can be reversed (Moskalenko and McCauley Citation2020). As a result of this analysis, we provide insights for optimising Public Service Advertisements (PSAs) to challenge RC-R (particularly with respect to RWEs’ reactions to what they perceive as “Islamist” radicalisation). This aligns with calls for a greater understanding of the re-humanisation formation process to counter the de-humanising logic inherent in radicalisation (Woodward, Amin and Rohmaniyah Citation2010).

Conceptualizing de/re-humanisation requires an understanding that the fundamental nature of one’s humanity can be rejected or reasserted (Bain, Vayes and Leyens2014). Several researchers have explored re-humanisation as a method for countering policies that promote radicalisation, and corresponding dehumanisation (e.g. Maiangwa and Byrne Citation2015). The notion of re-humanisation has also been investigated in ads designed to challenge RC-R, most notably of the British government’s campaign in Northern Ireland before and after the Good Friday Peace Agreement (Dedaic and Nelson Citation2012; Finlayson and Hughes Citation2000). Despite these analyses, the literature lacks a framework to understand how re-humanisation can be structured for PSAs designed to counter RC-R. Given growing concerns of RWE (Braddock Citation2020) and increased scrutiny of the efficacy of counter-extremism narrative-based campaigns (Carthy et al. Citation2020), we propose that analysing a prototypical counter RC-R ad may provide new insights into this domain.

Accordingly, we make two contributions to theory development. First, we demonstrate a prototypical multi-empathy activating ad-based approach to extend our existing knowledge on how to communicate “re-humanizing the dehumanized”. That is, we propose an ad-based process by which re-humanisation can reform audiences’ perceptions of those previously perceived as enemies. Although several studies have examined the re-humanisation within an ad-based context, no existing analysis provides a framework for optimising humanisation, and yet re-humanisation is central to counter-radicalisation. To redress this gap in our knowledge, we suggest that a comprehensive, policy-salient approach to challenging RC-R (Scrivens and Perry Citation2017) involves the consolidation of multiple proven approaches into the corpus of a multi-modal advert. More specifically, we propose that combining visual imagery with content that promotes individuation and empathy, a multi-model advertisement geared towards RC-R can enable re-humanisation. Second, and given the lack of studies analysing inoculation-based radicalisation message content (Carthy et al. Citation2020), our study represents a first effort to perform a deep-dive discursive analysis of a prototypical counter RC-R ad. An inoculative based strategy serves as a mechanism by which RC-R can be undermined.

To address these issues, we have structured the current study into multiple interrelated sections. First, we describe the need for a framework that captures the nexus between empathy, individuation and visual imagery to promote re-humanisation through the process of ad-based image-formation. We then demonstrate the utility of this nexus for challenging RC-R by discursively analysing a 2017 interfaith holiday advertisement for Amazon.Footnote1 The ad depicts the friendship between a Vicar and an Imam, vicariously representing an imagined friendship between Christians and Muslims. The ad was launched against the backdrop of rising populist sentiment in the West. Finally, we describe the implications of our analysis for informing public policy and marketing in relation to communicative efforts to challenge RC-R. Specifically, we argue that policymakers and strategic communicators should be cognisant of both verbal and non-verbal forms of communication, including the unspoken messages these forms of communication can signal (Schmid Citation2013).

Through this analysis, we address a gap in the literature related to counter-radicalisation programmes developed in the West, which Braddock (Citation2020, 19) argued “leaves much to be desired”. Similar to Braddock (Citation2020), McDonald (Citation2009) called for efforts to unlock the “silenced voices” of the marginalised and weak, who are often ignored by counter-radicalisation researchers and practitioners. The present research seeks to address these empirical concerns.

Reactionary co-radicalisation (RC-R)

Despite its ubiquity, the term radicalisation remains contentious, and has been described as a “fuzzy concept” with multiple definitions (Schmid Citation2013). As a result of ongoing contention regarding the required focus of radicalisation, a consensus definition remains elusive (Neumann Citation2013; Sedgwick Citation2010). However, one common theme in most definitions relates to the process of becoming an extremist, and adopting corresponding beliefs, attitudes and behaviours (Braddock Citation2020). As McCauley and Moskalenko (Citation2008, 416) explain, radicalisation reflects increasing “extremity of beliefs” and subsequent associative behaviours which support conflict “in defense of the in-group”, although this linear model of extremist beliefs developing into extremist action is far from conclusive (Neumann Citation2013). Although consensus on the mechanisms linking radicalisation and extremism remain unclear, radicalisation is generally considered to be an individual- or group-level process of social and psychological change towards extremism (Neumann Citation2013).

As a corollary to widely accepted understanding about radicalisation, counter-radicalisation relates to actively undermining radicalisation processes (Schmid Citation2013). In an effort to undermine radicalisation processes, formal and informal counter-radicalisation programmes have become institutionalised in countries around the world (Sedgwick Citation2010). One form of radicalisation that has garnered increased attention in the radicalisation discourse is reactionary co-radicalisation, or RC-R (Pratt Citation2015). RC-R is a form of “parallel reactionary extremism” whereby one group experiences the radicalisation of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours due to the perceived radicalisation of an out-group.

In coining RC-R, Pratt (Citation2015) drew on earlier concerns related to mutual co-radicalisation, particularly the symbiotic relationship between the growth of far-right sentiments and Islamophobia (e.g. Abbas Citation2012; Kundnani Citation2012; Jackson Citation2007, etc). For example, Kundnani (Citation2012) argued that the prioritisation of counter-radicalisation as a “Muslim problem” blinded experts to far-right radicalisation, especially given right-wing extremists’ use of Islamophobic tropes to legitimise their beliefs and actions (Hafez Citation2014). A key challenge in accepting the symbiosis of contemporary right-wing extremism and Islamophobia is recognising that the term “Islamic terrorism” is itself a co-radicalisation trope (Pratt Citation2015) and a form of dehumanisation (Jackson Citation2007). The conceptual conflation of Islam with terrorism (David and Jalbert Citation2008), creates an amplified threat from an entire faith and its adherents, humanising the West’s self-image, by dehumanising the “Muslim other” (Jackson Citation2007).

Moreover, “visual identifiers” of Islamic practice (Allen and Nielsen Citation2002), namely, the Muslim veil (Benhabib Citation2002) and the Muslim beard (Culcasi and Gokmen Citation2011), have been a particular target of Islamophobia (Allen Citation2016). Islamic visual identifiers are complicated by what Puar (Citation2007, 18) describes as “regimes of affect and tactility [that] conduct vital information beyond the visual” enabling the shift from “looks like a terrorist to feels like a terrorist” (Pugliese Citation2009, 2). In the aftermath of the September 11th attacks and culminating with the 2016 U.S. Presidential election, both the Muslim veil and beard transformed into bio-political identities, fuelled by a “commonly shared axis of media-fuelled Islamophobia” (Garland and Treadwell Citation2012, 127). Just as the image of the veiled Muslim woman became symbolic of subjugation – and the removal of it conditioned to liberalisation (Moghadam Citation1993) – the bearded Muslim male or “Mad Mullah” image (Beeman, Citation2007) became associated with notions of fear, danger and terror (Culcasi and Gokmen Citation2011). For Pratt (Citation2015, 215), this form of RC-R has public policy implications since it foments “in one case an electorate, in the other a single extremist.”

For example, during the 2016 Republican primary election campaigns, anti-Muslim politics offered a hook for electoral gains by radical right-wing politicians, thus influencing entire electorates in the U.S. and Europe (Feldman Citation2014, 1). Trump’s comments on Mexicans and Muslims, and the recurrent thread of border-control rhetoric amongst most of the 2016 Republican Presidential candidates signalled acceptance of RC-R rhetoric amongst mainstream American voting publics (Giroux Citation2017). Perhaps one of the most disturbing examples of contemporary RC-R was in Poland in 2017, when the Nationalist Party organised a march in which demonstrators called for a “Holocaust to Islam”. For Braddock (Citation2020), the rise of right-wing extremism in the West poses an emergent challenge in the form of stochastic terrorism, enabled by mass mediated public signalling, often by politicians, to vocalise an implicit support for such extremist sentiments.

In a response to the extremist sentiments expressed by elements of the far-right that promote RC-R, numerous corporate initiatives challenged Trump’s edict to ban Muslims and close the American Mexican border. This form of advertising is referred to as advocacy advertising. For instance, Amazon created a 2016 ad campaign intended to counter the dehumanised “mad mullah” stereotype. Given the novelty of this ad as one of the first to counter RC-R towards Muslims in the West, we analyse this ad as our study’s unit of analysis. Because the campaign was only aired in the US, UK and Germany (Sweney Citation2016) and launched during the run up to Christmas, we assume its target audience was the Christian population in these countries.

Inoculation theory

The notion of “attitudinal inoculation” has emerged as a form of communicative counter-extremism. Drawing from a medical analogue (McGuire Citation1964), attitudinal inoculation involves exposing audiences to weak versions of arguments the inoculator wishes to protect against. In the context of violent radicalisation, an inoculation message exposes the target to weak extremist propaganda to elicit feelings of persuasive threat. This motivates the target to defend their beliefs against organic messages that might pose a risk for radicalisation (e.g. extremist in-group sentiments; Carthy et al. Citation2020). After eliciting threat in this fashion, the inoculator provides the target with counter-arguments with which they might neutralise the persuasiveness of the propaganda to which the target is exposed.

Inoculation theory is also considered the “grandparent theory of resistance to attitude change” (Eagly and Chaiken Citation1993, 561) and the most well-developed theory of resistance to influence (Compton, Jackson and Dimmock Citation2016), as evidenced by decades of research supporting the technique (see Banas and Rains Citation2010; Carthy et al. Citation2020). Recent years have seen this efficacy extended to violent extremism (Braddock Citation2019), advocacy advertising (Burgoon, Pfau, and Birk Citation1995), and misinformation (Traberg, Roozenbeek, and Linden Citation2022). Most extant studies in this domain have relied on long-form video (e.g. Banas and Rains Citation2010) or text-based excerpts (e.g. Braddock Citation2019). Despite their contribution in highlighting the need for structuring inoculation content, in both instances, the stimuli are limited in terms of condensing message content within the corpus of a typical multi-modal PSA.

For the purposes of this study, the aforementioned Amazon ad comprises design elements consistent with traditional inoculation messages intended to immunise audience members against right-wing extremist doctrines. These elements include explicit forewarning of impending persuasive attempts (i.e. introduction of a “bearded” Muslim in the ad) and refutational pre-emption (i.e. the explicit refutation of the raised threat; Banas and Rains Citation2010).

Carthy et al.’s (Citation2020) review of the efficacy of counter-extremism narratives finds inoculation-based techniques to be most effective for preventing the assimilation of radicalised sentiments. Braddock’s (Citation2020) recent treatise related to communication and counter-radicalisation, Weaponised Words, also lauds inoculation-based approaches to countering right-wing extremism. Given the demonstrated utility of attitudinal inoculation, this study demonstrates the simplicity of designing inoculation messages in the context of short-form PSAs. Specifically, we show that inoculation messages can be constructed to counteract dehumanisation prompts and induce empathy for perceived members of outgroups.

Re-humanising the dehumanised to counter co-radicalisation

The evolution of humanity has been attributed, in part, to our capacity for empathy (Zaki and Ochsner Citation2012). Empathy refers to the imagination of another person’s perspective (Halpern and Weinstein Citation2004), and therefore requires the empathiser to recognise the humanity and cognitions of others (Fiske Citation2009). Oelofsen’s (Citation2009) study referenced empathy by claiming that the mental transportation of oneself into another’s world, “to take [his or her] perspective” (Lugones Citation1987, 328), is related to re-humanisation. Fostering empathy is therefore considered central in rehumanising others (Bain, Vaes, and Leyens Citation2014; Harris and Fiske Citation2009). Empathy and imagination are inter-twined in the re-humanisation process, since a lack of imagination is indifference, rendering others’ lives and subjectivities invisible (Oelofsen Citation2009). In addition, imaginative engagement with the “other” allows one to understand the other’s reality as a “possibility for myself” (Noddings Citation1984, 15), thus guiding imaginative enquiry into the target’s individual’s nature as a “distinct, complex person” (Halpern and Weinstein Citation2004, 574). Not surprisingly, re-humanisation processes are commonly used in RC-R programmes.

For instance, a student-organised, Vancouver-based counter-extremism programme called Voices Against Extremism (VAE) has historically sought to humanise asylum seekers and refugees to counter RC-R in reference to them (Macnair and Frank Citation2017). Specifically, VAE promoted a series entitled Stories of Resilience on their media platforms, where asylum seekers and refugees could publicly share their personal stories, humanising them to audiences as members of the wider community (Macnair and Frank Citation2017).

Empirical evidence in the literature also provides support for the efficacy of empathy-building for RC-R. For instance, some studies have shown how peace activists encouraged empathy for Iraqi civilians by encouraging American audiences to think of them as human beings with lives, families, and children (e.g. Bonds Citation2009; Decker and Paul Citation2013). Other research has demonstrated the effectiveness of stressing more abstract empathic motifs to counter RC-R, including shared values and concerns (Bahador Citation2012), shared cultural heritage, similar family commitments (Finlayson and Hughes Citation2000), and mutual civic responsibilities (David and Jalbert Citation2008).

Extant research in this domain has additionally shown that individuating, or attributing individual characteristics to others precedes the activation of empathy (Kiat and Cheadle Citation2017). As such, many aforementioned empathy-inducing stimuli are likely correlated with the individuation of members of an outgroup (Harris and Fiske Citation2009). In this way, individuation and empathy operate in concert to promote the humanisation of unknown others. This is salient when individuals have been previously dehumanised, providing a mechanism by which others can be rehumanised (Fiske Citation2009). Research on the mechanisms by which individuation (and by extension, empathy) can be stimulated are reviewed in the next section.

Re-humanization: as a multi-representational empathy space

There exist numerous narrative structural devices to foster empathy by promoting audience experiences that mimic those of narrative characters (Vaage Citation2010). Two of the most enduring are the point-of-view (POV) perspective and “reaction shots” (Smith Citation1995), which focus heavily on a character’s response to a stimulus. POV shots illustrate the narrative through the character’s experiences (often, but not exclusively in first-person perspective; Branigan Citation1984) and by projecting that experience metaphorically within the surrounding space through music, aesthetics, mise-en-scène, and camera work to signal something important is being experienced by the character. This technique stimulates empathetic engagement on the part of the audience (Vaage Citation2010). Described by Carroll (Citation2007) as “criterial pre-focusing”, or bridging the expanded empathetic space to the foreground, POV shots can activate conditioned familiar schemas, predisposing viewers to respond more empathetically. Trait-based empathy studies in advertising typically focus on the character and omit the expanded structural space the character inhabits, which may itself comprise the primary space which independently activates imaginative and embodied empathy. Close up face shots further enhance viewer predispositions to the character’s emotional state. Given our evolutionary ability to mirror facial expressions, these shots can automatically activate our embodied empathy by leveraging our non-verbal communication repository (Coplan Citation2008).

While advertising studies on audience responses to empathy provide useful insights (e.g. Shen Citation2010), they fail to capture the complexity of empathy as a potentially shifting wave within the corpus of richer narrative content (Coplan Citation2008). Where empathy-inducing message production has been investigated, individual aspects of the identification remain the focus. While film studies elucidate extensively on the structural nature of embedded empathy, they do not provide a framework which enables designers to map out the multi-representational space through which empathy might “flow”. Mapping this embedded multi-representational nature of empathy aligns well with the consensus that empathy is multi-representational in nature (Preston and Waal Citation2002).

Re-humanization: as a multi-representational individuation-empathy space

Individuation refers to a process whereby an individual considers others as fully human, typically by considering their beliefs, intentions and preferences. When the target is fully individuated in the mind of the subject, he or she becomes fully humanised (Fincher, Tetlock, and Morris Citation2017). Conversely, when people de-individuate, or lose their personal identity and values “on the altar of group approval” (Akhtar Citation1999), a slippery slope towards deindividuating “out-group” members can ensue, encouraging de-humanisation and radicalised sentiments to develop (Braddock Citation2020). Given that impression formation is the process of forming an overall and holistic understanding of the individual (Sanders Citation2010), encouraging individuation is essential in how we formulate positive social impressions and empathise with others.

For Fiske and Neuberg (Citation1990) for instance, impression formation falls along a continuum of binary schemas during initial phases of individuation (e.g. black/white, male/female), wherein the perceiver is motivated to engage in a “piecemeal” attribute-by-attribute integration to form a gestalt-based impression of the social target. Shifting viewers from the initial binary stage to developmental individuation is a key goal of humanising individuals and in reversing the self-deindividuation and other deindividuation common in radicalised individuals (Braddock Citation2020). Self-individuation can also foster “other individuation”, a view consistent with Jungian self-other individuation (Ladkin, Spiller and Craze 2018) and “mindfulness” (Salzberg Citation2002), since harnessing our interior lives can bridge inconsistencies of self-awareness between our inner and outer worlds (Todd Citation2009).

The individuation literature also suggests a range of potential stimuli, linked to self, community, and others, required to attain the type of bridge-building Jung originally perceived. No study to date has sought to capture the full myriad of individuating sources within humanised imagery. Whilst social cognitive studies focus on manipulating one individuating attribute at a time, a multitude of individuating attributes may be leveraged to humanise, and if formerly dehumanised, then to re-humanise the target character. The compressed nature of typical television commercials or PSAs challenges designers to optimise the individuation-empathy activation path. Ads are particularly well-suited to explore the representational space within which the multi-dimensionalities of empathy and individuation intersect to rehumanise the “other”, thus offering insights for public policy campaigns designed for countering RC-R (Edlins and Dolamore Citation2018).

A multi-representational re-humanization image formation process

The previous section indicated that a multi-representational approach is needed to capture the potential of individuating empathy-activating attributes inherent in the design of any intended re-humanised image. Yet a third layer of multi-representational complexity exists when analysing visual imagery. Because multi-sequential ads are predominantly visual and multi-modal (Williamson Citation1994), they entail shifting layers of multiple and simultaneous layers of latent and manifest content (Shabbir et al. Citation2014). Therefore, any analysis of imagery should review each layer in a systematic manner. Although the term “image” is polysemantic, visual imagery is formed through gestalt, or processed modularly (Barry Citation1997, 254), such that the “structure of each element contributes to a single, stable meaning”. Therefore, the greater the number of perceptual stimuli, the greater the accessibility of cues for activating empathy (Preston and Waal Citation2002).

This is a view consistent with the notion of viewer imagination and vividness as mechanisms for empathic re-humanisation (Husnu and Crisp Citation2010; Oelofsen Citation2009). Vividness elaborates and therefore heightens contact cue accessibility, or cues “that bring to mind the positive imagined counter” and is therefore an important mechanism to “humanize others” (Husnu and Crisp Citation2010, 949). The intersection between individuation, imagination and empathy may lie in the way our imagination, memory and empathy brain systems intersect. Theorists on memory and imagination support the notion that imagination is tied to the activation of memories, since when imagining events, we also tend to use our memory repository (Gaesser Citation2012). Vivid images of re-humanised individuals can therefore serve as imaginative platforms upon which to activate self-referential identity, and therefore, self-other individuation and subsequently empathy.

Previous experimental and content-analytic explorations of re-humanisation have neglected to capture the conceptual nexus between individuation, empathy and imagery. To illustrate, content analyses of re-humanisation (Bahador Citation2012; David and Jalbert Citation2008) have been limited to capturing manifest content (Ball and Smith Citation1992; Shabbir et al. Citation2014). Although there exist some examinations of re-humanisation in an ad context (e.g. Dedaic and Nelson Citation2012; Finlayson and Hughes Citation2000) that have employed discursive analysis, these studies have historically adopted a broad-brush approach, analysing an entire campaign of ads rather than individual ads themselves. This has limited the depth with which researchers have been able to explicate the multi-faceted nexus between imagery, empathy, and individuation.

Experimental studies on re-humanisation have revealed a number of processing effects due to changes in individual stimuli, but they have failed to capture the complexity of vivid dynamic or multi-sequential ads. This poses a threat to external validity, as multi-modal commercials are characterised by a complex parallelism between semiotic, or meaning making, modes (Cook Citation2001). As such, they require discursive analysis that can capture the possibilities of embedded “meaning-multiplication” (Bateman Citation2014, 252).

Indeed, the complexity of depth in such advertisements can relay “an enormous amount in a glance” (Bulmer and Buchanan-Oliver Citation2006, 51) and therefore, the study of empathy linked to the “content, stylistic and production features” (Shen Citation2010, 522) remains limited. One reason for this paucity is a lack of approaches capable of capturing the level of complexity inherent in visual imagery. To address this challenge, we adopt a multi-method approach that leverages Critical Visual Theory (CVT) and Dimensional Qualitative Research (DQR; Cohen Citation1999). While CVT enables ontologically grounded visual rhetoric analysis, DQR allows for the systematic coding of any multi-semiotic associations. We elaborate on each of these approaches in the following section.

Methodology

Critical Visual Theory (CVT) is an interdisciplinary approach combining techniques from visual studies (such as semiotics), with discourse analysis. This allows for a consideration of the salience of rhetorical devices (Ludes, Nöth, and Fahlenbrach Citation2014). Derived from visual hegemonics, or the intersection between image and power (Ludes Citation2005), CVT attempts to reveal the concealed dimensions of visual hegemony. Whereas a phenomenologically based hermeneutical approach can provide useful insights into the interpretive process, time-restricted evaluations demand rapid mental processing and thus preclude uncovering subtle or latent content in the corpus of the ad (Shabbir et al. Citation2014). As images often transmit meaning covertly, audiences can fail to scrutinise them to the extent that they understand the images’ full meaning (Cohen-Eliya and Hammer Citation2004). CVT, however, enables an ontological approach, and can therefore encapsulate multi-rhetoric analyses, providing public policy marketing practitioners with an avenue by which communications could function if marginalised actors had access to popular media (Borgerson and Schroeder Citation2002). CVT is also consistent with an emancipatory ethics approach to investigating counter-radicalisation, as it seeks to unlock “silenced voices” (McDonald Citation2009). Despite its benefits, CVT is limited in scope for the purposes of our analyses. Another approach is required that allows for the systematic analysis of each salient mode while remaining consistent with theories of humanisation.

DQR represents one such interpretive method, as it enables the categorisation of the multi-representational individuation-empathy-imagery nexus and therefore humanised perception. First proposed by Cohen (Citation1999), DQR is a novel adaptation of Lazarus’s (Citation1989) multi-modal therapy, used by ad analysts to tap into both manifest and latent ad content (Cohen Citation1999; Shabbir et al. Citation2014). DQR has been used to capture latent imagery in multiple ad contexts (e.g. Berthon, Pitt, and DesAutels Citation2011; Griessmair, Strunk, and Auer-Srnka Citation2011). Critically, the raison d’etre of DQR rests upon capturing the full spectrum of the human essence (Lazarus Citation1989), thus providing an ideal tool to capture perceptions of “humanness” and for encapsulating the full gamut of humanising individuating stimuli. Originally, multi-modal therapy relied on what was called the BASIC ID framework, where B stands for behavioural, A for affect, S for sensation, I for imagery, C for cognition, I for interpersonal relations, and D for drugs (i.e. physical/health) (Lazarus Citation1989). Cohen (Citation1999) added an eighth modality: the second S in the BASIC IDS mnemonic refers to socio-cultural aspects, precisely because “it is through sociocultural mechanisms that we learn … how to think of ourselves in relationship to others, and how to think of others in relationship to ourselves … [including] … what to reject and despise” (Cohen Citation1999, 364).

In summary, the DQR’s BASIC IDS dimensions provide an ideal mechanism for capturing the multi-representational space linked to analysing re-humanised imagery. Moreover, a CVT approach reveals how this imagery contributes to “the public determination of legitimacy, good and evil – and the [re] shaping of the preferences of one’s opponents” (Nye Citation2011, 8). Therefore, while CVT allows for silenced perspectives to unfold, the DQR enables for a systematic overview of the multi-semiotic organisation of the content being explored. An overview of the ad is subsequently introduced (primary analysis), followed by the application of the combined CVT-DQR analysis (secondary analysis).

Findings

Primary ad analysis

The Amazon ad fulfils Stern’s (Citation1994) criteria for advertising dramas, given that it has a focal action point (exchange of gifts), is chronologically linear, and comprises a change in the state of a few main characters with minimal narration. This type of structure has been associated with increased viewer enjoyment, diminished counterargument (Deighton, Romer, and McQueen Citation1989) and empathetic or sympathetic responses (Escalas and Stern Citation2003, Citation2003). Moreover, this structure aligns with Latorre and Soto-Sanfiel’s (Citation2011) concept of discovery-orientated content, as it shifts viewers from a state of initial uncertainty to epiphany and self-appreciation. The ad comprises forty-four separate shots comprising five main phases, corresponding to Freytag’s (Citation1863/2008) classic five “act” typology for the structural analysis of dramaturgy, which includes exposition (the beginning), complication (or rising action), climax (or turning point), reversal (or falling action), and denouement (or resolution). The ad’s plot reveals a lifelong friendship between a Christian vicar and a Muslim imam.

The plot’s beginning (exposition) involves the imam ringing the doorbell, the vicar appearing on screen (concurrent with the onset of the ad’s soundtrack) greeting the imam with a hug and walking him into his living room. Here, the two enjoy an act of tea-sharing conversation while realising each has knee pain. Both hug on departure and the vicar waves goodbye to the imam. Act two (complication), features third person POV shots of the vicar pondering curiously upon on closing the door, followed by a shot of the imam doing the same while walking against a background of lush trees. Following, in first-person POV shots, the vicar and the imam respectively order something from the Amazon Prime mobile app. The third act (climax) shows an Amazon worker delivering a box to the vicar, followed by a similar delivery to the imam. Both characters open the boxes in subsequent shots, revealing knee-support products that had been gifted to each by the other. Both characters are pleasantly surprised. Act four (reversal) shows both the vicar and the imam in their respective places of worship, putting on the knee supports with accompanying third-person, limited POV shots, where both signify reflective appreciation after putting on their knee supports to assist in their praying (resolution).

Secondary DQR-CVT based analysis

The ad’s exposition characterises the interpersonal context between the vicar and imam as friends, thus feeding into imagined inter-personal contact between belligerent groups (Allport Citation1954; Husnu and Crisp Citation2010). Critically, friendship’s causal effect on reducing prejudice has also been shown to be more predictive than other forms of interpersonal contact (Pettigrew Citation1997). Moreover, cross-group friendships uniquely foster deprovincialisation – learning that in-group norms are not the only way to make sense of the world – thus individuating and humanising out-groups (Pettigrew Citation1997). Numerous anti-RC-R PSAs have integrated cross-group friendship as a key theme. For instance, the Palestinian-Israeli Bereaved Families for Peace campaign used the theme of mutual loss and bereavement by showing united Palestinians and Israelis sharing stories of their grief.

For vicarious friendships, elaboration on the interaction is critical (Turner, Crisp, and Lambert Citation2007). To decouple the initial friend/foe or to deindividuate, vicarious cross-group friendships should demonstrate out-group positivity towards the in-group member, positive and tolerant inter-group norms, and a collective shared group identity (Paolini et al. Citation2004). It is worth noting here that the vicarious friendship in the Amazon ad is between religious community leaders. Mallia (Citation2009) notes, religious symbols in ads provide gestalt representations for their wider associative communities. This reinforces a popular counter-radicalisation policy strategy – the use of vicarious religious or community leadership to serve as referential agents for a majority viewpoint (Bruce and Voas Citation2010, 243).

One way the vicarious cross-group friendship in the ad individuates is through the use of sensory semiotic associations, such as vicarious touch, with four separate scenes of touch between the vicar and the imam. For Palmquist (Citation2016), friendship is conceptualised as a “theory of touch” and not surprisingly, touch theorists conceptualise touch as “spatial empathy” (e.g. Paterson Citation2005, 172), since it fuses the tactile and emotional “within each other”. Indeed, Hertenstein et al. (Citation2009) found, especially in a male-to-male touch context, that hugs and pats were linked to stimulating love, happiness and sympathy. The vicar welcoming the imam with a hug therefore reinforces these effects vicariously, especially for Western audiences where hugs are reserved usually for loved ones (Forsell and Åström Citation2012). Studies in mirror-touch synaesthesia, also hold that vicarious touch can neuro-physiologically activate inter-personal warmth (Banissy and Ward Citation2007). From a rehumanisation perspective, touch therefore serves as an important rhetorical device in individuating the “other” as worthy of empathetic orientation.

Communicating touch as acceptable in Muslim-Christian interactions also directly challenges the “magic principle of contagion” from Muslims, or the irrational fear of interacting socially with Muslims as dangerous (Pevey and McKenzie Citation2009). A touch based individuating cue for re-humanising the Muslim “other” has been validated by Choma et al.’s (Citation2016) study, in which inter-group disgust sensitivity, a construct largely based on measuring an individual’s revulsion for direct and indirect forms of touch with others, strongly predicted Islamophobic attitudes. As Braddock (Citation2020) notes, challenging disgust towards the “other” can provide a potent counter-radicalisation rhetoric. It is not surprising why touch is also celebrated as an essential symbolic diplomatic currency, with the handshake, for instance, widely recognised for its power to change the “course of conflicts” (LeBaron Citation2002). Consider, for example, Queen Elizabeth II’s handshake with Martin McGuinness, an IRA leader as central to eventually winning the peace in Northern Ireland (Moriarty Citation2022). A second obvious use of a sensory appeal in the ad is the use of relational musicology or music-based interventions for communal bridge building (Cook Citation2012).

The ad’s soundtrack, I Grioni, is a pleasantly sad tune, or “moving sadness”, wherein one simultaneously feels sad and moved (Eerola, Vuoskoski, and Kautiainen Citation2016), accounting for why audiences enjoy the act of crying at sad movies for instance. Sadness, especially if focused with “message sensation value” (i.e. strategically edited with visual, back and foreground spaces, light, etc) has also been proposed by Braddock (Citation2020) as potentially serving a motivational emotion in countering radicalised sentiments. In the case of relational musicology, listening to both unfamiliar and familiar “moving sad” music has been linked to activating emotional contagion and trait empathy respectively (Clarke, Vuoskoski, and Vuoskoski Citation2015; Eerola, Vuoskoski, and Kautiainen Citation2016). Such music can also activate nostalgia (Janata, Tomic, and Rakowski Citation2007) and associated auto-biographical memories typically of close “others”, further predisposing empathetic orientation towards others (Zhou et al. Citation2012). In either case, the negotiation of one’s own cultural self-identity, to imagine a shared collective conscious through self-reflective music becomes possible, an important goal of relational musicology (Cook Citation2012).

Moving to socio-culturally linked themes in the ad, we examine the allegorical associations behind the semiotic modes of the door, the home and the act of sharing a “cup of tea”. The opening shot of the blurry image standing behind the vicar’s glass-stained door, is one of only two shots in the ad without any soundtrack in the background. This technique of “abandoned sound” strategically leaves viewers in a focalised visual mode of frame, adding to the symbolic nature of any visual perceptual cues being presented (Horton Citation2013), or in the ad’s case, uncertainty. The allegorical connotation of the “knock at the door” may also resonate with Christian eschatology, given Revelation 3:20, one of the most popular Biblical verses used in Church sermons, or “Behold, I stand at the door, and knock” (King James Bible, 3:20), implying a voluntary invitation to internalising Christ (Pargament and DeRosa Citation1985). Here, to embrace Christ into one’s life, is being equated with humanising the Muslim “other” as friend, and in the process enacting “love thy neighbour”.

Therefore, is the entire ad a rhetorical refutational pre-emptive cognitive challenge to Christian self-identity to interpret the ad’s narrative of the Vicar as someone disseminating this sermon at the pulpit, living out its message by embracing Jesus but as the embodiment of the “other”, a Muslim “other” for that matter? If so, then to embrace Christ into one’s life is equated with humanising the Muslim “other” as friend, and for those insistent on stronger RC-R, providing a potent counterargument of “loving thy enemy” too. This reifies what Zickmund (Citation1997) refers to as the “ideological dialectic” in tackling the psycho-sociological roots of hate, and therefore activating counter-arguing by reversing the apparent “threat” from the perceived radical (Banas and Richards Citation2017).

The symbolic associations of the door, the doorbell, and indeed the entire exposition phase of the ad implies Christian “ethics of hospitality” (Bretherton Citation2017). This further invites Christian self-identifying viewers on a self-reflective journey of self-other individuation. There is yet further evidence of leveraging Christian eschatology in the ad, since the door is expressive of “crossing a boundary”, where the “aim of God is identified with the door” (Bretherton Citation2017, 149) and therefore as a fulcrum between the “divine and earthly, between sacred and … profane” (Riaubienė Citation2007, 154). Moreover, the bell is also symbolic in Christian eschatology as an acoustic “protector and intercessor” of divinity (Kovačič Citation2006, 114). It is therefore possible that the ad is leveraging another set of key emotions proposed by Braddock (Citation2020), guilt and envy, to ameliorate fear of the “other”. The use of archetypical Christian behaviour of the vicar reminds Christian-centric viewers of their own self-identity and Christ’s “message of love” but may also foster “envy” in viewers and thus potentially causing Christian-centric viewers to “desire what the other person [the vicar] has” (Braddock Citation2020, 189).

The home, as a socio-cultural space, in the ad’s exposition space provides multiple additional allegorical associations. As both a physically private and social location (Saunders and Williams Citation1988), the home provides ontological security – the trust we have in the continuity of our identity in an uncontrollable world (Dupuis and Thorns Citation1998). Ontological proof of formalised self-other individuation in our homes is evident from the myriad of objects we keep and display in our homes which “bear [the] extensive presence of others” (Dupuis and Thorns Citation1998, 239). Indeed, the home metaphor has been successfully used to encourage cultural tolerance, for instance in Australia’s immigration policy in the 1970s, linking it to notions of “hospitality, warmth, friendship, and unity” (Burke Citation2002, 62). More recently, positively leveraging the home metaphor has been demonstrated, with for instance New Zealand emphasising their “Kiwiness” to ensure an inclusive public policy towards managing Covid (Shabbir, Hyman, and Kostyk Citation2021).

For Bell (Citation2010), hospitality rests on the language of home, guest and host, all resonating in the ad’s exposition, since not unlike the Vicar, to be truly hospitable is to fall “hostage to the one who arrives” (Derrida Citation2002, 361–2). The home therefore provides a double allegorical and rhetorical structure for challenging the discourse of RWE that the “homeland” needs “protecting” (Gullestad Citation2002), since nationalistic security threats are typically fused with home metaphors (Kinnvall Citation2004). The setting of the home therefore provides a rich repertoire of ontologically secure associations for self-other individuation to ensue, serving as a source of critical pre-focusing (Carroll Citation2007) by accepting the Imam into the ontologically safest space for the self. Accordingly, the ad fosters audiences to process additional emotions imperative to countering radicalisation (Braddock Citation2020), such as overcoming perceived “fear” from the “other”, whilst also leveraging again envy and guilt of the “ideal” Christian hospitality demonstrated by the vicar.

The centrality in Christian ethics of “hospitality as holiness” (Bretherton Citation2017) is formalised further through the act of “tea sharing”, thus employing the widely recognised public policy intervention of culinary diplomacy (Chapple-Sokol Citation2013). Although it is never made evident in the ad whether the Vicar and Imam are enjoying tea, as opposed to coffee, the daytime associations with tea drinking are well known (Verma Citation2013), as are its colloquial association with Vicars (Rees Citation2014). Sharing tea is at the very core of British social-cultural practice but globally too it implies, at “best a significant move towards cementing friendships” (Fox Citation2014). Verma (Citation2013, 164) suggests that given tea’s social connotations, it is symbolic of transforming individual to collective identity, and therefore central in “consensus-building”. Here, positive emotions, important in counter-radicalisation communication psychology (Braddock Citation2020), aligned to hope, happiness and potentially pride – in celebrating a key social-cultural symbolic act of tea sharing – may all serve to strengthen Christian-centric viewers to reversing dystopic visions of Muslim-Christian relations to collaborative and relational ones.

Although the behavioural exchange of gifts between Vicar and Imam plays well to Amazon’s value offerings, it also demonstrates phillic bonding between Vicar and Imam, according both, but critically by the Imam in particular, that most fundamental of humanistic affect, love (Maslow Citation1967). Whilst both suffer from knee pain, they instead chose to purchase knee support products for each other displaying “doing well by someone for his own sake, out of concern for him” (Cooper Citation1977, 302), i.e. Aristotelian phillia, or the love between friends (Kraut Citation1989). Phillia is one of the primary constituents of human essence, since its maturation, from an early age, requires having empathy for others (Rasmussen Citation1999). Furthermore, acts of altruism are important incubators of this compassionate love as they bind the giver and receiver in a shared humanity or an “extended self” (Belk and Coon Citation1993, 402). From a public policy perspective, gift giving is symbolic of forgiveness, since “when we give to others the gift of mercy and compassion, we ourselves are healed” (Enright and North Citation1998, 54). Perhaps, here the ad challenges co-radicalised sympathisers to overcome their pre-conceived anger, and aids viewers to perform behaviours they would otherwise find difficult, or even unimaginable to do for the “other” (Braddock Citation2020). The act of giving however is not atomistic, as evident in the ad which packages the gift with pre- and post-exchange POV based phases.

In the pre-exchange phase, the vicar and then the imam are seen pondering immediately prior to ordering their gifts, connotating reflective minds, and therefore depth, agency and cognitive openness, key indicators of humanisation (Haslam Citation2006). It is not until we realise what the gift was that additional humanising individuating attributes can be allocated to both characters. Realising that both have brought knee support products for each other, the self-reflection in the pre-phase POV shots now takes on an additional implication in post-POV shots of inferring emotional responsiveness as well as moral sensibility, logic and maturity, all indicative of humanising attributes (Haslam Citation2006). Moreover, since the sequencing of the shots and the selection of product is matched for Vicar and the Imam, this implies synchronisation between the minds, i.e. they are one and the same. Here, ideological dialectic closes the counterargument on the side of humanisation or the ad’s epiphany moment. The responses on receiving the gifts are the only shots in the ad with complete escorted voice-out shots or no background sound (Horton Citation2013) and show the Vicar smiling, and the Imam laughing on receiving the gift from the Amazon worker, with a female voiceover for her delivery greeting. Moreover, the Imam’s spontaneous laugh, as well as the female Amazon worker’s speech, are the only clear human voices in the ad. Given that verbo-centricism rests on humanising characters by allowing viewers to hear their voice (Chion Citation1994), the ad emphasises the imam’s capacity for emotional expressiveness and complemented by a female voice, additionally positioning humanising rhetoric since it is more closely aligned with feminine values (Kimble Citation2004).

Smiles, muted laughter and painful “groans” were also heard in the ad’s first phase, adding to its use of embodied empathetic markers. According to Gervais and Wilson (Citation2005, 423) laughs and smiles are the “fountainhead of human uniqueness”. “Feel good” ads can evoke smiling (Teixeira and Stipp Citation2013) and the contagious effects of vicarious laughter and smiling on empathy are also documented (Provine Citation1992). Hearing or seeing someone in pain is similarly linked to higher states of empathy (Keysers and Gazzola Citation2010). Indeed, “I feel your pain” is the primary expression of empathetic concern (Goldman Citation2006). This paradox of enjoying viewing pain lies in the resolution of pain as the “realization of the endurance of humanity” or hope (Smuts Citation2009, 512). Thus, forcing a realisation that ultimately both Christian and Muslim share the same superordinate category of human first and foremost, a theme extended into the final phases of the ad.

The final phases of the ad are particularly poignant in further communicating the cognitive, or state of minds, of both Vicar and Imam, and therefore simulating the same in the audience. Both characters internalise the gifts in the privacy of their prayers, implying both appreciating the other within their most sacred of spaces – within their relationships with God himself, lies an acceptance of the “other”. Two POV shots in the final phase of the ad reinforce this appreciation of the other. After putting on the knee support products both Vicar and Imam, look up with a gaze of “peace”. Both are depicted in a brief but poignant moment of what Oliver and Bartsch (Citation2011, 31) describe as “contemplation of meaningfulness via human virtue” or appreciation. Both are seen as seeking to be near God in their own respective ways, but this nearness to God has become easier, indeed made possible, by appreciating the “other”. In these shots, refutational pre-emption reaches a climax, through appreciation of the formerly “dehumanized” other through hope, a key emotional bridge building appeal for reversing radicalised sentiments (Braddock Citation2020). We discuss the implications of our analysis of the ad, and its potential for creating counter-argumentation against RCR, in our discussion in the next section.

Discussion

What our analysis demonstrates is that constructive engagement for purposes of challenging co-radicalisation can be undertaken using dynamic ads. Although we use a corporate ad and wherein the design of the ad also appeals to its market-based offerings, the marketing of gift giving, the design of the ad demonstrates a prototypical structure for countering R-CR. We know of no anti-RC-R ad design which compares to the multi-dimensional richness presented in this ad. Therefore, anti-RC-R PSAs may serve as rich platforms for optimising the re-humanisation formation process. We demonstrate the utility of leveraging a multi-representational trajectorial nexus between imagery, individuating attributes and empathy activation to achieve this purpose. We believe this affords PSAs with a systematic message construction approach to reversing RC-R, since it taps into a combination of routes for re-humanising the “other”. These paths have also been noted in the counter-radicalisation public policy and advertising literature but in isolation, not as an organised nexus. Had the Amazon ad, for instance, only focused on tea drinking, the ad would only tap into one potential source of perceived commonality with the “other”. Similarly, had the ad explicitly used coffee, it would obfuscate the richer associations of tea sharing for consensus-building. Therefore, by strategically using a multi-representational approach to re-humanising “others”, marketers and public policy makers can optimise counterarguments, whilst immunising viewers. Since empathy activation operates as a “supra modal representational space” (Decety and Jackson Citation2004), policy makers are well advised to optimise its representational schema in counter RC-R campaign design.

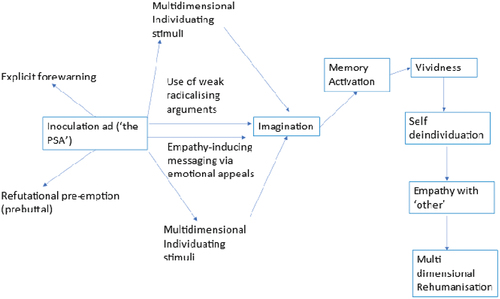

While our study focused on RC-R, there is no reason to indicate that the same pathway cannot be leveraged for other forms of counter-radicalisation PSA structures. The power of the ad as a condensed storyteller is a candid reminder that public policy makers require a similar optimisation and nexus of stimuli to reverse de-humanising radicalised rhetoric. By activating multiple but distinct dimensions which cumulatively are linked to humanisation, policy makers can cumulatively represent abstract and symbolic cues for optimising the inoculation of radical sentiments. Each dimension we explored is inter-connected in cumulatively contributing to re-humanisation. Each of the dimensions we used provides a foundation from which viewers can be moved along the self-other de-individuation pathway. Each dimensional theme presented in the ad also has, and critically, established links to empathy activation. In so doing, the ad immunises viewers by reducing the perceived threat from the “other”, and therefore strategically shifts viewer critical thinking in the direction of re-humanisation. It does this by leveraging a multitude of emotions, each however having credence in the counter-radicalisation literature as attenuating radicalised attitudes (Braddock Citation2020). It is important to note here that the dimensional themes in our analysis are variable to different contexts. Therefore, gift-giving is not the only affect-based theme which can be harnessed nor tea drinking. The main implication of our analysis is to identify dimensional themes which serve as individuating stimuli to activate empathy. We depict these dynamics in below.

The ad’s resolution also offers new insights in fostering vicarious appreciation, or contemplation with a higher purpose, within a condensed educational entertainment message schema. Activating appreciation is important in intellectual entertainment as a discovery-orientated process in the resolution of the message (Latorre and Soto-Sanfiel Citation2011). Critically, Braddock (Citation2020) recently proposes more widespread use of educational entertainment in counter RC-R. Traditionally educational entertainment extends across multiple series of informational and dramaturgical content. The challenge for counter-radicalisation PSAs is condensing self-transcending intellectual entertainment within the corpus of the ad, so that the resolution leaves an audience with a meaningful, hope infused, connection with a higher purpose (Oliver et al. Citation2011) and uses credible voices to do so. Self-transcending marketing message content incubates self-other individuation, or as Oliver et al. (2018) elaborate, fosters a recognition of the other as self, thus helping to overcome inter-group hostility.

We propose that PSAs designed for challenging RC-R inspire or challenge us to contemplate human moral virtues, or “what it means to live a ‘just’ or ‘true’ life” (Oliver and Bartsch Citation2011, 31). If anti-radicalisation PSAs become increasingly meaningful and self-transcending, they are more likely to achieve critical thinking, counter-argumentation to radicalising sentiments, and therefore immunisation through refutational pre-emption (i.e. prebuttal). Our study provides a mechanism for self-transcendence from hate that can be engineered within the re-humanisation formation process, through the strategic leveraging of a nexus between imagery, individuating stimuli and empathy.

Since our focus is on countering RCR, we believe the emergent insights into the rehumanisation process that PSAs could employ, offer important implications on how to more effectively design campaigns to reverse Islamophobic, and other forms of Xenophobic rhetoric. In summary, our study responds to calls for an inclusive approach to counter-radicalisation (Braddock Citation2020), embedded in amplifying silenced voices (McDonald Citation2009). Although, counter-radicalisation policies in the West have previously been lauded as multi-dimensional and holistic (e.g. Argomaniz Citation2011), here we demonstrate that this multi-dimensionality and holisticity can be extended into the corpus of an ad.

Further research and conclusions

A key emergent finding in our study is that we find a prototypical ad designed to rehumanise the dehumanised (i.e. to arrest RC-R). Braddock (Citation2020) recommends the use of emotional appeals to achieve this, thus demonstrating that a typical multi-modal approach can encapsulate key inoculating appeals to generate self-transcendence and counter RC-R targeted at a mainstream audience.

Our study therefore indicates the possible pathway through which a counter-radicalisation PSA might be used to rehumanise extremists towards the “other”. Further research is necessary to test how effective such ads are in practice, though we recognise the inherent difficulty in measuring their effectiveness because the co-radicalising target audience is unlikely to succumb to being interviewed. Our study does not consider the importance of the source of the message, an issue we know is critical, but which is beyond the scope of this article. We do recognise that it is not necessary for all viewing segments of the Amazon ad to follow the pathway highlighted in our analysis. However, given the political climate during the ad’s release, we contend that the message design reinforced Amazon’s stance on countering RC-R, while serving its market-based objectives.

Further research is necessary to align the rehumanisation pathways with different combinations of message to identify those that are most effective. By demonstrating how PSAs have the potential for rehumanisation, we hope to reignite government and public interest in designing and delivering PSAs which bridge the gap between self- and others in order to promote more tolerant societies. The Amazon inter-faith ad may provide a prototypical example for this purpose.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Richard Jackson and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance. We also thank Rob Kozinets for his comments on an earlier draft of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Haseeb Shabbir

Haseeb Shabbir is a Reader in Voluntary Sector Management at Bayes Business School, City, University of London. His research spans ethics in advertising, inclusive imagery and not for profit marketing. He has extensive experience in coaching managers from international peace NGOs, on marketing and communications. In 2017, he hosted one of the world’s first conference special sessions on ‘peace marketing’ and has co-authored (with D. Dean) on theorising the concept of peace marketing. His work has been published in the Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, Journal of Business Ethics, Psychology & Marketing, European Journal of Marketing, and in the Journal of Service Research.

Paul Baines

Paul Baines is Professor of Political Marketing and Deputy Dean at the University of Leicester, Visiting Professor at Cranfield and Aston Universities, and Associate Fellow at King’s College’s Centre for Strategic Communications. He is (co)author/editor of 100+ articles, chapters and books including the SAGE Handbook of Propaganda (2020). Paul’s research focuses on political marketing, military influence and (counter)propaganda. Paul has worked on strategic communication research for the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Home Office, Ministry of Defence, UK Law Enforcement and overseas government departments.

Dianne Dean

Dianne Dean is Professor of Cultural Values and Practices at Sheffield Business School. Her background in Political Marketing has focused on trust, persuasion and propaganda, particularly among minoritized groups. Her work falls in the area of Transformative Consumer Research which seeks to use marketing for good. She has worked on theorising the concept of peace marketing and is co-author (with H.A. Shabbir) of a chapter in the SAGE Handbook of Propaganda. She has published in journals such as Journal of Service Research, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Business Ethics, and the Journal of Business Research.

Kurt Braddock

Kurt Braddock is an Assistant Professor of Public Communication at American University. His research centers on the persuasive strategies employed by extremists to draw audiences to their cause. Dr Braddock has published dozens of articles on radicalization in security and communication outlets, as well as the book Weaponized Words: The Strategic Role of Persuasion in Violent Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization (Cambridge University Press, 2020). He advises a number of national and international security organizations, including the US Department of Homeland Security, the US Department of State, the UK Home Office, and the UN Office for Counter-Terrorism.

Notes

1. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKEzqGHS2hw.

References

- Abbas, T. 2012. “The Symbiotic Relationship Between Islamophobia and Radicalisation.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 5 (3): 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/17539153.2012.723448.

- Akhtar, S. 1999. “The Psychodynamic Dimension of Terrorism.” Psychiatric Annals 29 (6): 350–355. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19990601-09.

- Allen, C. 2016. Islamophobia. London: Routledge.

- Allen, C., and J. S. Nielsen. 2002. Summary Report on Islamophobia in the EU After 11 September 2001. Vienna, EUMC.

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

- Argomaniz, J. 2011. The EU and Counter-Terrorism: Politics, Polity and Policies After 9/11. Oxon, U.K: Routledge.

- Bahador, B. 2012. “Re-Humanizing Enemy Images: Media Framing from War to Peace.” In Forming a Culture of Peace, edited by K. Korostilina. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 195–211 .

- Bain, P., G. J. Vaes, and J.-P. Leyens. 2014. Advances in Understanding Humanness and Dehumanization. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Ball, M. S., and G. W. H. Smith. 1992. Analyzing Visual Data. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Banas, J. A., and S. A. Rains. 2010. “A Meta-Analysis of Research on Inoculation Theory.” Communication Monographs 77 (3): 281–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751003758193.

- Banas, J. A., and A. A. Richards. 2017. “Apprehension or Motivation to Defend Attitudes? Exploring the Underlying Threat Mechanism in Inoculation‐Induced Resistance to Persuasion.” Communication Monographs 84 (2): 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1307999.

- Bandura, A. 1965. “Vicarious Processes: A Case of No-Trial Learning.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 2:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60102-1.

- Banissy, M. J., and J. Ward. 2007. “Mirror-Touch Synaesthesia is Linked with Empathy.” Nature Neuroscience 10 (7): 815–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1926.

- Barry, A. M. 1997. Visual Intelligence: Perception, Image, and Manipulation in Visual Communication. New York: State University of New York.

- Bateman, J. 2014. Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide. London: Routledge.

- Beeman, W. O. 2007. The “Great Satan” Vs. the “Mad Mullahs”: How the United States and Iran Demonise Each Other. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Belk, R. W., and G. S. Coon. 1993. “Gift Giving as Agapic Love: An Alternative to the Exchange Paradigm Based on Dating Experiences.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (3): 393–417. https://doi.org/10.1086/209357.

- Bell, A. 2010. “Being ‘At home’ in the Nation: Hospitality and Sovereignty in Talk About Immigration.” Ethnicities 10 (2): 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796810361653.

- Benhabib, S. 2002. The Claims of Culture: Equality and Diversity in the Global Era. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Berthon, P., L. Pitt, and P. DesAutels. 2011. “Unveiling Videos: Consumer‐Generated Ads as Qualitative Inquiry.” Psychology & Marketing 28 (10): 1044–1060. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20427.

- Bonds, E. 2009. “Strategic Role Taking and Political Struggle: Bearing Witness to the Iraq War.” Symbolic Interaction 32 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2009.32.1.1.

- Borgerson, J. L., and J. W. Schroeder. 2002. “Ethical Issues of Global Marketing: Avoiding Bad Faith in Visual Representation.” European Journal of Marketing 36 (5/6): 570–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560210422399.

- Braddock, K. 2019. “Vaccinating Against Hate: Using Attitudinal Inoculation to Confer Resistance to Persuasion by Extremist Propaganda.” Terrorism and Political Violence 34 (2): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1693370.

- Braddock, K. 2020. Weaponized Words: The Strategic Role of Persuasion in Violent Radicalization and Counter-Radicalization. U.K: Cambridge University Press.

- Branigan, E. 1984. Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film. Amsterdam, New York: Morton.

- Bretherton, L. 2017. Hospitality as Holiness: Christian Witness Amid Moral Diversity. London: Routledge.

- Bruce, S., and D. Voas. 2010. “Vicarious Religion: An Examination and Critique.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 25 (2): 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537901003750936.

- Bulmer, S., and M. Buchanan-Oliver. 2006. “Visual Rhetoric and Global Advertising Imagery.” Journal of Marketing Communications 12 (1): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527260500289142.

- Burgoon, M., M. Pfau, and T. S. Birk. 1995. “An Inoculation Theory Explanation for the Effects of Corporate Issue/Advocacy Advertising Campaigns Communication Research.” 22 (4): 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365095022004006.

- Burke, R. 2002. “Invitation or Invasion? The ‘Family Home’ Metaphor in the Australian Media’s Construction of Immigration.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 23 (1): 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256860220122403.

- Carroll, N. 2007. “On the Ties That Bind: Characters, the Emotions, and Popular Fictions.” In Philosophy and the Interpretation of Popular Culture, edited by W. Irwin and J. Garcia, 89–117. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Carthy, S. L., C. M. Doody, K. Cox, D. O’Hora, and K. M. Sarma. 2020. “Counter‐Narratives for the Prevention of Violent Radicalisation: A Systematic Review of Targeted Interventions.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 16 (3): 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1106.

- Chapple-Sokol, S. 2013. “Culinary Diplomacy: Breaking Bread to Win Hearts and Minds.” The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 8 (2): 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1163/1871191X-12341244.

- Chaudhuri, A., and R. Buck. 1997. “Communication, Cognition and Involvement: A Theoretical Framework for Advertising.” Journal of Marketing Communications 3 (2): 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/135272697345998.

- Chion, M. 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, Translated by Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Choma, B. L., R. Haji, G. Hodson, and M. Hoffarth. 2016. “Avoiding Cultural Contamination: Intergroup Disgust Sensitivity and Religious Identification as Predictors of Interfaith Threat, Faith-Based Policies, and Islamophobia.” Personality & Individual Differences 95:50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.013.

- Clarke, E. D. T., J. Vuoskoski, and J. Vuoskoski. 2015. “Music, Empathy and Cultural Understanding.” Physics of Life Reviews 15:61–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plrev.2015.09.001.

- Cohen, R. J. 1999. “What Qualitative Research Can Be.” Psychology & Marketing 16 (4): 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199907)16:4<351:AID-MAR5>3.0.CO;2-S.

- Cohen-Eliya, M., and Y. Hammer. 2004. “Advertisements, Stereotypes, and Freedom of Expression.” Journal of Social Philosophy 35 (2): 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2004.00223.x.

- Compton, J., B. Jackson, and J. A. Dimmock. 2016. “Persuading Others to Avoid Persuasion: Inoculation Theory and Resistant Health Attitudes.” Frontiers in Psychology 7:122. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00122.

- Cook, G. 2001. The Discourse of Advertising. London: Routledge.

- Cook, N. 2012. “Anatomy of the Encounter: Intercultural Analysis as Relational Musicology.” In Critical Musicological Reflections: Essays in Honour of Derek B. Scott, edited by H. S. Editor, 193–208. Ashgate, Surrey: Ashgate.

- Cooper, J. M. 1977. “Friendship and the Good in Aristotle.” The Philosophical Review 86 (3): 290315. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183784.

- Coplan, A. 2008. “Empathy and Character Engagement.” In The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film, edited by P. Livingston and C. Plantinga, 117–130. London: Routledge.

- Culcasi, K., and M. Gokmen. 2011. “The Face of Danger: Beards in the U.S. Media’s Representations of Arabs, Muslims and Middle Easterners.” Aether: The Journal of Media Geography 8 (3): 82–96.

- David, G. C., and P. Jalbert. 2008. “Undoing Degradation: The Attempted “Re-humanization” of Arab and Muslim Americans.” Ethnographic Studies 10:23–47.

- Dean, D., and H. Shabbir. 2019. “Peace Marketing as Counter Propaganda? Towards a Methodology Propaganda.” In The SAGE Handbook of Propaganda, edited by P. Baines, N. Snow, and N. O’Shaughnessy, 350. U.K: SAGE.

- Decety, J., and P. L. Jackson. 2004. “The Functional Architecture of Human Empathy.” Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews 3 (2): 71–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534582304267187.

- Decker, S., and J. Paul. 2013. “The Real Terrorist Was Me: An Analysis of Narratives Told by Iraq Veterans Against the War in an Effort to Rehumanize Iraqi Civilians and Soldiers.” Societies without Borders 8 (3): 317–343.

- Dedaic, M. N., and D. N. Nelson. 2012. “At War with Words.” In Vol. 10 of Language Power and Social Process (LPSP Series, edited by M. Heller and R. J. Watts, 1–469. New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Deighton, J., D. Romer, and J. McQueen. 1989. “Using Drama to Persuade.” The Journal of Consumer Research 16 (3): 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1086/209219.

- Derrida, J. 2002. Acts of Religion, translated by G. Anidjar. London: Routledge.

- Dupuis, A., and D. C. Thorns. 1998. “Home, Home Ownership and the Search for Ontological Security.” The Sociological Review 46 (1): 24–47.

- Eagly, A. H., and S. Chaiken. 1993. The Psychology of Attitudes. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Edlins, M., and S. Dolamore. 2018. “Ready to Serve the Public? The Role of Empathy in Public Service Education Programs.” Journal of Public Affairs Education 24 (3): 300–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2018.1429824.

- Eerola, T., J. K. Vuoskoski, and H. Kautiainen. 2016. “Being Moved by Unfamiliar Sad Music is Associated with High Empathy.” Frontiers in Psychology 7:1176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01176.

- El-Said, H. 2015. New Approaches to Countering Terrorism: Designing and Evaluating Counter Radicalization and De-Radicalization Programs. U.K: Springer.

- Enright, R., and N. Joanna. 1998. Exploring Forgiveness. USA: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Escalas, J. E., and B. S. Stern. 2003. “Sympathy and Empathy: Emotional Responses to Advertising Dramas.” Journal of Consumer Research 29 (4): 566578. https://doi.org/10.1086/346251.

- Everett, J. A. C. 2013. “Intergroup Contact Theory: Past, Present, and Future.” The Inquisitive Mind 2 (17). https://in-mind.org/article/intergroup-contact-theory-past-present-and-future.

- Feldman, M. 2014. Doublespeak: The Rhetoric of the Far Right Since 1945. USA: Columbia University Press.

- Fincher, K. M., P. E. Tetlock, and M. W. Morris. 2017. “Interfacing with Faces: Perceptual Humanization and Dehumanization.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 26 (3): 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417705390.

- Finlayson, A., and E. Hughes. 2000. “Advertising for Peace: The State and Political Advertising in Northern Ireland, 1988–1998.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 20 (3): 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/713669727.

- Fiske, S. T. 2009. “From Dehumanization and Objectification to Re-Humanization: Neuroimaging Studies on the Building Blocks of Empathy.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1167 (1): 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04544.x.

- Fiske, S. T., and S. T. Neuberg. 1990. “A Continuum of Impression Formation, from Category-Based to Individuating Processes: Influences of Information and Motivation on Attention and Interpretation.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 23:1–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2.

- Forsell, L. M., and J. A. Åström. 2012. “Meanings of Hugging: From Greeting Behavior to Touching Implications.” Comprehensive Psychology 1:1–17. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.17.21.CP.1.13.

- Fox, K. 2014. Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behavior. Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Freytag, G. 1863/2008. Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art. Chicago: Griggs.

- Gaesser, B. 2012. “Constructing Memory, Imagination, and Empathy: A Cognitive Neuroscience Perspective.” Frontiers in Psychology 3:576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00576.

- Garland, J., and J. Treadwell. 2012. “The New Politics of Hate? An Assessment of the Appeal of the English Defence League Amongst Disadvantaged White Working-Class Communities in England.” Journal of Hate Studies 10 (1): 123–141. https://doi.org/10.33972/jhs.116.

- German Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. 2020. Brief Summary: 2019 Report on the Protection of the Constitution. Facts and Trends. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/kurzmeldungen/EN/2020/07/vorstellung-verfassungschutzbericht-en.html.

- Gervais, M., and D. S. Wilson. 2005. “The Evolution and Functions of Laughter and Humor: A Synthetic Approach.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 80 (4): 395–430. https://doi.org/10.1086/498281.

- Giroux, H. A. 2017. The Public in Peril: Trump and the Menace of American Authoritarianism. New York, USA: Routledge.

- Goldman, A. I. 2006. Simulating Minds: The Philosophy, Psychology, and Neuroscience of Mindreading. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press.

- Griessmair, M., G. Strunk, and K. J. Auer-Srnka. 2011. “Dimensional Mapping: Applying DQR and MDS to Explore the Perceptions of Seniors’ Role in Advertising.” Psychology & Marketing 28 (10): 1061–1086. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20428.

- Gullestad, M. 2002. “Invisible Fences: Egalitarianism, Nationalism and Racism.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8 (1): 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.00098.