Abstract

Photographic records of early 1900s polar expeditions encapsulated a paradox: the spectacle of “monotonous” “numbing whiteness” in images of “nothing” that were intended for public exhibition. This article examines expedition photography as an ecosystem of materials and meanings to reconsider the status of the “failed” photographic experiments that have remained sublimate to the iconic images of polar exploration. Light sensitive materials — photographic emulsion layered onto glass plates and strips of flexible transparent celluloid nitrate film — are integral to the registration of the image. However, these materials are also susceptible to the effects of humidity, touch and variations in temperature. Anomalies, such as details that were effaced by overexposure to light and watermarks registered the effects of labour in a polar climate These “failed photographic plates were occluded from exhibition, yet remain integral to the ideation of the incomprehensible in polar expedition narratives. In this context, experimental and “failed” images can be read as part of an ecosystem of interactions and begins to decipher the popularity of Ponting’s 1911 photograph “Ice-Blink”, the image of a seemingly featureless ocean horizon, as the commodification of “nothing” in discursive spaces of exhibition.

Photographic records of early 1900s polar exploration encapsulated a paradox: sparse vistas of ice, the “monotonous” “numbing whiteness” of Antarctic landscapes that were described as “without human interest”, yet presented as a source of spectacle in public exhibition.Footnote1 Antarctica had remained unmapped, “atemporal”, “extreme, acultural, ahistorical, and elemental”, without horological or cartographic measure beyond fragments of its shifting coastline.Footnote2 Expeditions led by Carsten Borchgrevink, Robert Falcon Scott, Roald Amundsen, and Douglas Mawson experimented with combinations of cameras and photosensitive materials as technologies that offered an unprecedented means of capturing and studying time and movement in an environment that appeared to typify stasis, encapsulated in ice, yet was endlessly susceptible to change. In these images, the histories of photography, science and polar exploration intersect. Expedition records include amateur photography, images that document the work of the explorers (zoology, meteorology, geography) and those that record the use of camera technologies in scientific experiments (microphotography, panoramic views, flashlight photography). “Failed” photographs, which were characterised by overexposure, cracked glass plate negatives and the effects of condensation, remain among these records, offering another perspective on the study of time and movement in the history of labour and technology. Light sensitive materials — photochemical emulsion layered onto glass plates and thin, flexible, transparent strips of celluloid nitrate film — were integral to the registration of the image, yet also record the effects of humidity, touch and variations in temperature. In this analysis of scientific and photographic experiments, I suggest that the indexicality of light sensitive emulsion registers the effects of an inhospitable climate on camera technologies and explorers at the level of the image and its material substrate as an ecosystem of materials and meanings to reconsider the status of the “failed” photographic experiments that have remained sublimate to the iconic images of polar exploration. The glass plate negatives, in which overexposure to light diminished the legibility of details and watermarks obfuscated the image, are retained in museum collections. Faulty photographic plates, marked and scratched through the effects of work in an extreme climate (exhaustion, frozen hands and instruments, snow blindness) and occluded from exhibition, remain integral to the ideation of the incomprehensible in narratives of polar exploration. The seemingly endless photographs of sea and ice, considered indecipherable to non-specialist viewers, were refigured using commercial studio practices (composite images; tints, tones; carbon tissue prints) to tailor the depiction of space to the shifting discourses of spectatorship in urban modernity. Photographic galleries and magic lantern slide lectures offered an educational form that was able to entice and entertain public interest, linking spectacle, geography, and science in exhibitions such as the national tour of The British Antarctic Expedition Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting F.R.G.S.Footnote3 Photographs that recorded the performance of science for camera aligned the figure of the explorer/cameraman/scientist, as narrator of the expedition, with an act of visual enquiry through the use of an optical instrument (microscope, telescope, camera). In this context, I read Herbert G. Ponting’s 1911 photograph “Ice-Blink”, the image of a seemingly featureless horizon at sea, as the commodification of “nothing”, a spectacle, laced with illegibility, that demanded explanation in the discursive spaces of exhibition.Footnote4

The indexicality of the photographic image, inscribed by the configuration of light, camera, time and location specific to its making, typified a central paradox of modernity as the permanent imprint of the ephemeral. However, the susceptibility of photosensitive materials to the effects of water, touch, and variations in temperature, registered the wave-like marks and lesions deictic of work in polar climates.Footnote5 The characteristics defining of “failed” images are specific to the time, place, and practices of photographic and scientific experimentation undertaken on polar expeditions. These contingent effects remain vital to deciphering the structure of time and labour, registering both the images and effects of the polar climate. Chance is interleaved with the discourse of scientific integrity and labour as the trace of technical difficulties remains inscribed in the photographic materials. Strips of film became brittle and broke, camera oil froze, condensation leached photosensitive emulsion from the glass plates: these materials were retained and documented in expedition journals as the negative results of experiments, forming a vital record of the ways in which photography did and did not work. The iconic, faulty, failed experiments and faded prints retain the “privileged relation to the real, to referentiality, and to materiality” of the photographic image and medium, that was woven throughout narratives of Antarctic exploration as they entered public consciousness, the ideation of “nothing” in a permanent record of a fleeting moment.Footnote6

Early 1900s polar expeditions examined photographic materials and camera technologies, from photomicrography, stereoscopic views, telephoto lenses, aerial views, to colour processes for still photography (Paget Plates, Autochromes), for their potential as modes of scientific enquiry. The use of photography invested in the concept of mechanical objectivity to supplement established modes of documentation (sketches, notebooks, and specimens of flora and fauna). Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison discern the historic moral aspect of mechanical objectivity in the registration of an image that is unmediated by the wiles of subjective perception, yet note that the need for institutional structures that support the status and objectivity of photographic evidence as deictic of public scepticism.Footnote7 Daston and Galison remark on a shift in the concepts of objectivity and subjectivity in the late 1800s. The photographic document, connected to ideas of restraint and a purpose beyond individual interests, “least vulnerable to subjective intrusions”, linked the moral aspect of scientific photography to the ideation of heroism, sacrifice and fortitude in expedition narratives.Footnote8 Journals written by the explorers embedded the “failed” experiments — scientific and photographic — in this discourse of integrity. The spectacle of science and geography, further constructed through the dramatization of experiments for camera, reiterated the monolithic imperialist gaze of exploration in photographic illustrations intended to align the spectator with the singular entity of the scientist as hero and narrator of the voyage ().Footnote9

Fig. 1. Lieut. Evans observing an occultation of Jupiter. 8 June 1911. Ref. P2005/5/442. Photographer: Herbert G Ponting. Flashlight photograph. Print from orthochromatic glass plate negative. Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, with permission

Photographic experiments, deemed to have “failed” for the details rendered illegible by overexposure to light and the featureless skies registered by orthochromatic plates, remain in museum collections, yet these images are often occluded from display.Footnote10 In rereading the “monotonous” and “featureless” in photographic records, I suggest that faults, detritus and duplicate images register a combination of scientific and social practices that forms a material record of an ecosystem of exploration in Antarctica. Further, my analysis of the registration and darkroom practices that constructed photographic images for exhibition, begins to unpick the ways in which the incomprehensible became a commodity that continues to be linked to the ideation of vulnerability, science and integrity in public narratives of the heroic age of polar exploration.

Experimentation and Innovation in Expedition photography

If photography is integral to the historiography of early 1900s expeditions, then the images, material substrate and history of their making matters. The archives of Antarctic expeditions led by Carsten Borchgrevink and Robert F. Scott indicate commonalities in their crew and photographic practice.Footnote11 William Colbeck, who kept magnetic observations on Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition 1898–1900 was subsequently Captain of the Morning 1902–03 and 1903–04 as relief ship for Scott’s Discovery expedition 1901–04. The photographic work undertaken by Colbeck and J. D. Morrison offers an additional perspective to the scientific studies attributed to Charles Royds, Reginald Koettlitz, Reginald Skelton, and Ernest Shackleton as crew of the Discovery. The British expeditions coincided with Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld’s Swedish South Polar Expedition 1901–03 and Erich von Drygalski’s German National Antarctic Expedition 1901–03 in examining the potential of telephoto lenses, panoramic and aerial photography as modes of scientific enquiry. For example, Emil Philipi’s 1902 photograph, taken from a hydrogen balloon, depicts Drygalski’s expedition ship, the Gauss trapped in the ice 420 meters below. The use of technology — the meteorological balloon and camera — in registering a topographical view, recurs in Shackleton’s aerial photograph, which was taken 750 ft above the Discovery locked in ice. The rope tether and shadow of the balloon, which is specific to the fall of light at that time and place, makes sense of Shackleton’s viewpoint as cameraman in an otherwise disorientating feint image. The photograph was printed in the Illustrated London News Saturday 4 July 1903 signalling the public interest in Antarctic exploration, science and spectacle; it was also included in a photograph album gifted to Miss Dawson Lambton as a benefactor of the Expedition.Footnote12

The commercial viability of public fascination with expedition photography was underscored within a decade by the employment of Herbert G. Ponting as professional photographer and self-named “camera artist” on Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13, and travel photographer Frank Hurley on Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–14 and Shackleton’s Imperial Trans Antarctic Expedition 1914 − 17. Ponting and Hurley advised on scientific photography, documented the expeditions, and produced images intended for public display. The laboratory techniques used to edit expedition photographs included composites that superimposed two or more negatives, cropping, the addition of colour dyes by hand. These practices were familiar to commercial studios and indicate the multiple purposes of the images.

The history of photographic experiments is interspersed with negative results that remain vital to the epistemology of exploration. The circumstances in which unsuccessful photographs were made was often recalled by explorers in published journals, cinema lectures, and newspapers that set the image in a narrative of mechanical and aesthetic drama. The British Journal of Photography related Ponting’s lament of “endless troubles caused by the freezing on lenses of the vapour from the hand, and the cracking of cementing balsam in lenses and filters”.Footnote13 The inclusion of a flashlight photograph titled “Castle Berg”, in the Illustrated London News further invokes the pragmatics of photography in the months of darkness that denote the polar winter. The use of non-freezing oils that froze and the film of ice that breath left on photographic plates is recalled alongside Ponting’s remark, that “it was not ‘You Press the button: we do the rest!’”.Footnote14 Ponting’s description of his work as a “camera artist” differentiates his craft from the automation implied by the slogan from the Kodak advertising campaign contemporary to the expedition. The invocation of the Kodak advertisement is further contrived to elicit interest of a spectatorship contemporary to the publication of The Great White South as Ponting’s written account of the 1910–13 expedition. The presentation of the photograph, “Castle Berg”, in the Illustrated London News text constructs an ideologically complicit image of Nature as spectacle in which the artifice of flash light is underscored by references to labour and technology: an ethereal image and photographic imprint of the physical effects of a polar climate.

Ecosystems: environment, evidence and exhibition

Marks, scratches and the indistinguishable forms traced in overexposed negatives do not offer a systematic study of the environment, yet these photographic materials register of effects of extreme temperatures on the motoric abilities of explorers (frost-bite, malnourishment). The resultant “failed” photographs, such as those described by Jennifer Tucker in Nature Exposed, “can enlarge our understanding of photographic evidence”.Footnote15 Experiments with scientific and photographic technologies were connected to the recuperation of the costs of geographical exploration. My analysis of the ways in which scientific photographs were edited for the discursive spaces of exhibition (galleries, museums) begins to decipher the “monotonous” aspects of topographical views of the Antarctic in expedition narratives. The social frameworks of scientific lectures that developed to support the presentation of photography as empirical proof, as a “neutral mirror of reality”, indicate a counter current of scepticism in the reception of scientific studies.Footnote16 Thus the paradigm of the topographical view as unmediated observation, the instrument of the scientific analysis of nature and dependent on the indexicality of photographic, displaces the contingent effects of the environment into the lectures and texts that accompany the images in exhibition attesting to the veracity of the image. Ponting’s observations of ice bergs, rocks, waves and skies were registered using orthochromatic photography, which was “highly sensitive to the blue-end of the visible spectrum and […] often led to totally overexposed skies if used without filters”, appearing featureless, cloudless.Footnote17 For exhibitions, the images were reconfigured to emphasise a sense of place legible to the spectator contemporary to the expedition. For example, news reports on the exhibition of Ponting’s Antarctic photographs at the Fine Art Society’s gallery in London, described a resource offering:

information about ice and icebergs, their growth and their ways; about clouds and sunshine; about birds, including those droll and fascinating little people, the penguins; about seals and their habits; and about the labours and heroism of man. The beauty of some of these scenes is enthralling, so strange and impressive are the shapes assumed by the ice, so pictorially effective the fall of the light and shade.Footnote18

Notes on the scientific and aesthetic persist in replica exhibitions in Cheltenham and at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, where a report on the “Scott Expedition in Photography” detailed:

Huge bastions of mediaeval type rise skyward, and the play of light on their flanks is well suggested while again No.117, an iceberg off Cape Evans, is admirable, and a weathered iceberg (No.121) is interesting. Rare and curious and, withal beautiful, is the picture of the Terra Nova in McMurdo Sound, taken on a calm day, and showing an iceberg in the last throes of dissolution, just as one off Cape Royds shows one in its early stages. Eighty miles away, the high peaks of the Western Mountains of Victoria Land are clearly visible, a fine demonstration of the purity of the atmosphere.Footnote19

The newspaper article invokes the grandeur of known architectural forms, tempered by a note on decay, to configure a spectacle of scale and “purity” that differs from the fall of snow for which “pollution soon follows its arrival” in the city. The article offered an interpretation of the Antarctic that was directed toward an urban public contemporary to the expedition.Footnote20

In Inhospitable Worlds, Jennifer Fay finds the peripheral areas of expedition photographs to be revelatory of patterns of retreating ice that trace shifting polar seasons in an ecosystem of Antarctica. Expedition photographs recorded geographical observations, evidence of ships instructions met, and scientific experiments in the study of time and movement. The indistinct forms and anonymous areas of photographic images, as an imprint the physical effect of labour and technologies in the Antarctic, offer a supplementary register of the ecosystem of the interactions of the expeditions and environment, which Fay reads as deictic of other pasts and futures beyond human-centric records of the Anthropocene. As topographical views of Antarctica entered the discursive spaces of gallery exhibitions, the amorphous and indistinct forms recorded by the explorers became a site of epistemological anxiety in photographs, narratives and archives. Thus, I examine the ideation of the “numbing whiteness” and “radical negativity” of the polar climate through three primary lines of enquiry.Footnote21

anomalies — watermarks, spots, and blurring trace the interaction of technologies, the explorers and an extreme climate — as a material trace of resistance in the automation of labour (pencil sketches, repetitive tasks such as recording magnetic observations) and photographic image production.

the dramatization of science as spectacle in expedition photographs.

the featurelessness of topographical views — tempered and refigured by the institutional framework of narratives and iconic images of Nature, mediated by the explorer, and intended for public circulation — became a commodity aligning the connoisseur with the scientist/ cameraman/ explorer as narrator of the photograph and its making.

Gunnar Iversen finds such “seemingly endless white dullness” of arctic views as problematic to the public presentation of polar expedition films.Footnote22 Iversen refers to Tom Gunning’s concept of a “view aesthetic”, which describes the “effect of a space apart from the camera, as if the image is a window”, offering a privileged sight of uninterrupted whiteness, devoid of geographical features that might otherwise designate a specific location.Footnote23 Iversen examines these monotonous views as constructions of space and place. However, the negotiation of a social and material history of photographic and scientific experimentation, in which featureless “failed” photographic plates are a mark of innovation, remains to be deciphered and forms the focus of my analysis of the construction of a cultural aesthetics of “nothing” for public exhibition.

Spaces of discourse: views and spectatorships of Antarctica

In her analysis of nineteenth century photography, Rosalind Krauss writes about images that have been displaced from the collections of topographical views for which they were made. Krauss states the topographical “view rather than landscape as their descriptive category” as a form that presents the feature of the photograph as an unmediated object: an “image of geographic order” with clearly delineated earthen shapes, liquids and textured surfaces visible. Topographical views differ from the landscape photographs that are formatted and edited to represent “the space of autonomous Art and its idealized, specialized History, which is constituted by aesthetic discourse”.Footnote24 The photographic records of polar expeditions include scientific studies that appear unremarkable, without narrative or illustrative content, offering little of immediate interest to a non-specialist viewer. Read through the framework offered by Krauss, such images can be sifted from the hierarchy of values — of ownership, authorship, spectacle and commodity — that otherwise sublimate them into the aesthetic interests of public exhibition. Writing in 1982, Krauss noted that:

Everywhere at present there is an attempt to dismantle the photographic archive – the set of social practices, institutions, and relationships to which nineteenth-century photography originally belonged - and to reassemble it within the categories previously constituted by art and its history. It is not hard to conceive of what the inducements for doing so are, but it is more difficult to understand the tolerance for the kind of incoherence it produces.Footnote25

The displacement of topographical views, that had been produced as geographical and meteorological studies of wave-like furrows and ridges carved in ice by variations in temperature and wind, into museums and galleries, internalised both the politics and aesthetics of exhibition. The occlusion photographic plates that were deemed unremarkable or damaged according the cultural aesthetics of display, persists in the digital circulation of the archive. Immaterial simulacra of fragile objects — glass negatives, magic lantern slides, rolled-strips of film — often form the first point of public access to museum collections. Watermarks, lens flare, and fractures form an indexical trace of the production, circulation and storage specific to that glass plate or strip of film. Such marks register a direct relationship between the image and the filmed space that André Bazin describes as an “ontology of the photographic image” that is relevant “no matter how fuzzy, distorted or discoloured” the image may be.Footnote26 The deselection of photographic materials by archivists and researchers, aware of the social value of its making and history and politics of display, but working within economic restraints of funding for digitisation projects that are accountable to public interest, nevertheless tend toward images that are illustrative of the narrative of the expedition.Footnote27 Elizabeth Edwards notes that the “non-collections” of working documents generated through curation, which appear to be supplementary to the value invested in an exhibition, remain vital to deciphering the historical epistemology of each museum and archive.Footnote28 Unremarkable photographs, letters, notebooks and their copies gathered in unstated groupings are indicative of an intellectual working project within the scale of values held by institution, whether it be a museum or expedition. The historical contexts of production and display intersect in contingent records -failed experiments, working copies, decayed images in which the differentiation of figure and ground has diminished over time — as part of an ecosystem of technology, labour and environment. An analysis of anomalous photographs is revelatory of the “complexity and density” of the discursive formations of polar expeditions and their archives.Footnote29 The negotiation of monotonous views in exhibition contexts of spectatorial critique, that Krauss notes was internalised by the editing of the image for presentation, tracks a hierarchy of values in which the incomprehensible of an inhospitable environment is aligned with it featurelessness. The “nothing” of the indexicality of scientific and photographic experimentation in an extreme climate, becomes a spectacle through the nexus of ownership and authorship in the image of Antarctica as commodity.

Colbeck’s “observations on the Antarctic Sea-ice”

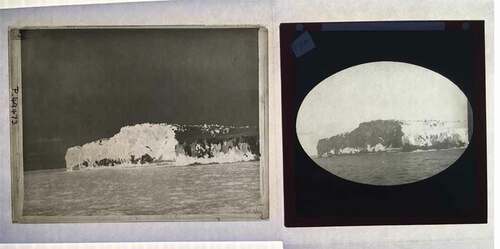

The tension between scientific photography and the aesthetics of display persists in polar expedition archives. William Colbeck’s photographic negatives, which document the voyages of the Morning as relief ship to R. F. Scott’s Discovery expedition 1901–04, recur as copies in different media forms and texts (prints, magic lantern slides, illustrations) alongside those attributed to Shackleton, Royds and Morrison. The selection of photographs that were published in a scientific study titled “Observations on the Antarctic Sea-Ice” include “Haggitt’s Pillar”, which Colbeck named after his brother, and “Scott Island” which was listed after the Captain of the Discovery.Footnote30 The illustrations were produced from the photographic negatives (), yet have been cropped to reduce the expanse of the ocean that surrounds the rock formation (). Colbeck’s article was published in The Geographical Journal, an imprint of the Royal Geographical Society as institutional sponsor of the expedition and relief ship.Footnote31 The technologies and nomenclature of scientific photography operate in discourse of economic imperialism, familial connections, and geographical knowledge () as mountains, islands, seas and ice barriers were named after benefactors of the expeditions. The rationale for the British polar expeditions can be tracked through the reports of the Antarctic Committee, which included representation from the Royal Society and Royal Geographical Society.Footnote32 The reports link territory with “commercial and private enterprise”, seeking justification for the cost of the expedition in the potential of research on magnetic observations used for navigation, marine fauna and flora, oceanography, hydrographical research into the distribution of the open sea, its temperatures and currents, meteorology, and “the delineation of the actual land, now only certainly known at one or two points […] a great blank on the maps”.Footnote33 Photographic records contributed to the cartography of the Antarctic, the reconnaissance of unknown terrain, and registering an image as evidence of national claim over a geographical formation or area.Footnote34 The indexicality of the photographic negative, inscribed by light, is aligned with the concept of mechanical objectivity as a scientific observation such as that which is read by Krauss as an instrument of institutional claim. The photograph of Haggitt’s Pillar and Scott Island is inferred as objective, concealing the subjective interests of Colbeck as its author and that infers a legal right to territory claimed through the image.Footnote35 The topographical views recorded on the voyages of the Morning appear to offer an objective record that internalises the politics and discursive context of a scientific report. However, the collection of photographs recorded by Colbeck and J. D. Morrison also retain an objective imprint of labour, technology, and the environment. The photograph captioned “Loose Pack, Northern Edge Showing Line of Open Water”, records an observation that was useful to navigation and the feint distortion of the blurred movement of sea-ice.Footnote36 An analysis of the peripheral areas of the image — its oceanic expanse, “numbing whiteness” and “radical negativity” — reveals contingent details that persist within the permanent record of the expedition. The spots, fading, blurring, fogs, specks, and haloes evidence the history of camera technologies and photographic practices, that is of the social dynamics of solitude and collaboration that underlie scientific and photographic experimentation.Footnote37 The erroneous and indecipherable in photographs registers an indexical trace of labour in an extreme climate and of nature that resists the institutional possession implied by the concept of an unmediated topographical view.

Fig. 2. (a).(left) The photograph is of Scott Island. Ref. P49473. Photographer: William Colbeck/J. D. Morrison. Orthochromatic glass plate negative. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (b). (right) The same photograph of Scott Island was formatted and framed to the smaller dimensions of a magic lantern slide, Ref. HP1980/170. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Fig. 3. Scott Island and Haggitt’s Pillar, printed in William Colbeck, “Observations on the Antarctic Sea-Ice”, The Geographical Journal, vol.25, no.4 (1905), pp. 401–405. Copyright Clearance Centre and RGS-IBG, with permission

The specificity of the photographic medium, as Mary Ann Doane writes, remains “far from an insistence upon mimesis or verisimilitude, this demand for blankness, illegibility, and absence as the support of illusion. It also suggests that the experience of a medium is necessarily determined by a dialectical relation between materiality and immateriality.”Footnote38 Further, I suggest that faults, such as indeterminate images of ice and mirage, mottled with condensation or obscured by the movement of the camera in topographical views of the Antarctic, can be read in reference to Doane’s notes on “material resistances”, as instances in which the indexicality of the photographic disrupts the iconicity of the image, yet remains significant to the interpretation of meaning.

Material records of photography and labour

The journals written by Charles Royds on the Discovery expedition recall the use of photography for reconnaissance to ascertain the viability of the terrain for sledging. Scott’s instructions to Royds indicate the precarity of this work: “from your observations + from photographs taken at sea it would appear that the ascent of Mount Terror might be made on firm ground; such an ascent might yield valuable topographical results, but should only be undertaken with the greatest caution.”Footnote39 Photography informed the cartographic studies of the region. The time and location (longitude and latitude) of each photograph is recorded alongside the weight of equipment on a sledging journey (camera 6 ½ lbs, photographic glass plates 4 ½ lbs, camera legs 2 ¾ lbs). Royds’ journals detail a combination of fatigue, uncertainty, and the freezing environment that affected his work: his finger in front of the lens obscured a view of Mount Erebus, a photograph of the ice barrier ridge was blurred from forgetting to “adjust for distance”, these errors were compounded by the delay between the exposure of plate and the processing of results in a laboratory onboard the Discovery.Footnote40 Scott’s Report to the Presidents of the Royal Society and the Royal Geographical Society as the organising committee and sponsors of the expedition, relates Royds’ journey over “bare rock, windswept: then roped together, using crampons and ice axes” as he “succeeded in descending to the sea ice […] As a result of his enterprise he was able to get several specimens of young Emperor Penguins in down, and an excellent series of photographs and notes.”Footnote41

The use of photography on Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition 1898–1900, attributed to Louis Bernacchi, had negotiated similar environmental conditions to record “specimens, and, whenever opportunity offered, photographs were taken of the various peaks on the coast within sight, and cinematograph photos whenever active incidents of interest occurred.”Footnote42 Bernacchi notes the importance of cinematography in the study of movement, whether the habits and interactions of animal life or the formation of pack ice, as subjects that appeared blurred in still photographs. Further, Bernacchi’s 1902 report on the “self-recording” Eschenhagen machine, which used photosensitive materials to record magnetic observations on the Discovery expedition, notes a shift in the repetitive work of maintaining a geomagnetic record.Footnote43 The Eschenhagen machine offered a level of automation in place of repetitive act of recording magnetic observations used for navigation. Similarly, experiments with photographic materials — macrophotography of flora and fauna, panoramas, topographical views — in place of pencil sketches and watercolour studies, gradually altered the temporality of labour and the image. The taxonomy of signs examined by Charles S. Peirce denotes a specific object here and now, which in my analysis of polar expedition records, includes the materiality of the photograph as image and indexical trace specific to that camera, time, and place. In this context, Peirce’s theorisation of indexicality can be read of the flurries snow that reveal the directional force of wind, and the singular fleeting instance of a mirage as the manifestation of particular meteorological conditions. Each registers a transient effect that adheres to reality.Footnote44 Instances of lens flare and watermarks registered in photosensitive materials, singularities that obfuscate the image, are not systematic like the Eschenhagen machine, but offer transtemporal data of the environment. As Peirce writes, “resemblance is due to the photographs having been produced under such circumstances that they were physically forced to correspond point by point to nature” denoting a physical connection that refers both the legibility of an image and marks that are disruptive of iconicity.Footnote45 The referentiality of the image is specific to the moment of exposure, a likeness and material record that is displaced from a photographed subject that continues to alter (age, decay, ice forming), a process that Bazin describes as “change mummified”.Footnote46

Parenthetical photographs

In an analysis of two photographs, taken by Ponting, of the departure and return of Edward A Wilson, Henry Bowers, and Apsley Cherry Garrard on the Northern Journey to Cape Crozier in search of Emperor Penguin eggs in 1911, Kathryn Yusoff writes that “Photography freezes and re-animates events in these two ways. It arrests images that can stand as historic testimony; and it organizes a notion of historic time as linear narrative” that is suggested by the before and after image.Footnote47 The photographs mark the journey in parenthesis. Records of this aspect of the expedition are sparse and pragmatic, their intermittent occurrence indicating the uncertainty of survival in an inhospitable climate. The depredation of the body is apparent in the photograph that marked the return of the explorers viewed in relation to the image of their departure. The forces of an environment that at times confounds photographic representation through darkness, lens flare, exhaustion, are inscribed on the bodies of the explorers. The parenthetical photographs, elide the time and movement of the journey, whilst its effects remain laced with uncertainty and inscribed in the deterioration of the explorers. The ontology of the photographic, as Bazin writes, “embalms time, rescuing it simply from its proper corruption”. The polar expedition records, like Doane’s assertion that early 1900s photography offered a “fixed representation […] poses a threat, produces aesthetic and epistemological anxiety” that is typified in the unseen and incomprehensible aspects of the journey that institutional contexts and commercial imperatives of display negotiated as the spectacle of “nothing”.Footnote48 The parenthetical photographs are deictic of an elision in the expedition records, their juxtaposition a rudimentary form of a narrative, a representation of time, that marked the threshold of bodily disintegration. In polar expedition records, material and temporal ‘faults are equally witness to […] authenticity. The missing documents are the negative imprints of the expedition — its inscription chiselled deep’.Footnote49

Scientific observations and experiments that invested in the rationalisation and mapping of the polar environment continued to circulate throughout the first world war. The sparse views recorded by expedition photographers intricated the “failed” experiments and visceral inscriptions of an inhospitable environment into public discourse of irresolute loss. Douglas Mawson, writing in 1914 about Frank Hurley’s photographs on the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911–14, notes that “the glamour connected with the self-sacrifice” was integral to the story of polar exploration.Footnote50 The photographic records of polar expeditions, as experiments in the standardisation of time and the formation and display of images as a process of memorialisation, internalised the discursive spaces of art history and exhibition. It is useful to recall Apsley Cherry Garrard’s obituary for Ponting as he writes that “Here in these pictures is beauty linked to tragedy — one of the greatest tragedies — and the beauty is inconceivable for it is endless and runs to eternity.”Footnote51 Polar expedition archives and the ontology of the photographic coalesce in the paradox of a permanent record of a fleeting moment as a central concept of modernity and echoes Doane’s note that if “memory is representation itself” then time — the here and now of the journey- is its inconceivability.Footnote52

The Ice Blink

The work of Herbert G. Ponting as professional photographer and “camera artist” on Scott’s Terra Nova expedition focussed on recording the diurnal activities of the expedition and advising on the use of photographic technologies in scientific experiments. Ponting recorded a series of flashlight photographs that depict the technologies of scientific enquiry. Each composition foregrounds a diegetic source of light and optical instrument — Atkinson with a microscope in his laboratory; a lamp set on the ice as a fish trap is raised; Lieut. Evans observing and occultation of Jupiter (); and a self-portrait of Ponting at work in the darkroom of the winter base hut. Flashlight photography, was pragmatic in the winter months of darkness and constructed a dramatic image of science and labour. As Ponting observed, “It’s only the pictorial prints that pay.”Footnote53

Ponting and Scott describe an experiment with synchronous photographic exposures along a baseline that was intended to calculate the height of the Aurora Australis against a constellation of stars, yet which failed register their light or location.Footnote54 Other experiments included an approach similar to Royds’ cartographic photography. The use of a telephoto lens to capture an image of Victoria Land seen from Ross Island was considered by Ponting to be of “lasting importance to geography”, yet proved to be problematic. In “the first sunny summer days the radiation from the sea had been so great that the quivering air rendered telephotography of distant objects impossible”.Footnote55 Visual distortion, as an effect of the climate, obfuscated the registration of a clearly delineated image. A photograph described in reviews of the Fine Art Society exhibition of Ponting’s work — “Eighty miles away, the high peaks of the Western Mountains of Victoria Land are clearly visible, a fine demonstration of the purity of the atmosphere” — emphasises the singularity of the image aligning the spectator with photographer/explorer in aesthetic discourse of Art and its “idealized, specialized History”.Footnote56

The illustrated catalogue for “The British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13. Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting F.R.G.S.” notes the inclusion of “The Ice Blink”. The view across the sea toward a horizon where clouds dissipate into a formless grey sky, as the catalogue notes, records a particular instance of a mirage which could be used to inform navigation ().

Fig. 4. Ice Blink over the Barrier 3 January 1911. Ref. P2005/5/1540. Photographer: Herbert G Ponting. Photographic print from orthochromatic glass plate photographic negative. Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, with permission

The glow in the sky is known as “Ice Blink,” the name given to the reflection from ice on the clouds. Whenever this glow is seen, ice is known to lie ahead. In this case the “blink” is that of the Great Ice Barrier […] the thin line of white in the distance is the Barrier and it is plainly seen that where the ice ends, there is no “blink” in the sky.Footnote57

The Ice Blink — a mirage and configuration of light, at that time and location — specific to the moment of photographic exposure is an indexical trace of the interaction of technology, explorer and environment and that is recorded in a blank area in the photograph. In his letters to Frank Debenham, Ponting notes that the print is the most popular among members of the expedition as the image demands an explanation for both its meteorological and photographic topic.

I am not a scientist, but I love it, and think it one of the very best things I ever did. And, as you know, it was a “not so easy” bit of work. There is no faking whatever about it. It is from an absolutely untouched enlarged negative . It was taken on an “ISO” plate with a four times screen, and the effect is exactly as it developed out.Footnote58

The photograph is described as “untouched” and so can be differentiated from Ponting’s composites and the artifice of flashlight in the production of dramatic illustrations of scientific research. The photograph, Ponting writes, is unaltered, “no faking”, recalling the undercurrent of scepticism that necessitates the association of scientific photography and the concept of mechanical objectivity. However, as Ponting describes “the finest print of ‘Ice Blink’ that has ever been taken from the negative […] a perfect beauty” he also recounts the selection of a green and blue tissue:

which seems to suit the subject exactly. The coloured prints are not tinted bromides, but are printed in carbon, the finest and most permanent photographic process known. They should last until the paper support rots.Footnote59

The material alterations that occur in printing the photograph for display infuse “The Ice Blink” with colour. The photograph was prepared by the Autotype Company, a commercial laboratory specializing in Carbon Tissues prints, in reference to a colour chart that was published in a catalogue of photographic equipment. The sample images of maritime subjects are depicted in Sea Green, Bottle Green, and Royal Blue, which inflect a Eurocentric concept of colour and meaning across a view of the Polar seas. If the use of green tissue, for example, signifies “nature” it is the nature and hue of a landscape other than the Antarctic. The use of colour is part of an ideological construct of Nature, infusing the unfamiliar and familiar, mediating an otherwise sparse composition. The transient mirage, “The Ice Blink”, is made permanent, “until the paper support rots”, its featurelessness demanding an explanation and finding its economic value in a social context as topic of conversation. The tension between the incompleteness of photographic records and expedition narratives aligns the scientist/cameraman/ explorer as narrator of the unseen with the connoisseur as conduit of insights into a fragmented and indecipherable horizon at sea. The “Ice Blink” invests in the spectacle of nothing as commodity in the discursive spaces of exhibition. The uncertainty of a mirage as point of navigation, visible as elision on the horizon that deictic of an ice berg that remains out of sight, is a material resistance of “nature” within the cultural codification of the Nature of Antarctica. The “Ice Blink” as an optical illusion in a topographical view has the potential to incite curiosity in unremarkable and “failed” photographs, which might bequeath insight into the unseen workings of the expedition that are not immediately apparent at the level of the image. The contingent effects of meteorological conditions and photographic practice form a material trace of the social history of the expedition.

Imperfect images?

Monotonous views of Antarctica are a nexus of contingent and collaborative photographic practices through which a social history of exploration can be traced. Imperfect photographic materials, the faded, overexposed, and the results of failed experiments that tend to be occluded from digitisation projects and exhibition, reside in the non-collections noted by Edwards. The photographic plates of unsuccessful experiments, if they remain, are likely to offer unexciting images: starless skies, vast vistas without the feintest trace of the Aurora Australis, mountains obstructed by the amorphous shapes of frostbitten fingers and thumbs too close to the lens. However, such images are an inscription of the interactions of technology, explorer and the environment, indicative of social practices, labour and the image. The ways in which technologies did not work in extreme climates, the elisions in journals and photographic records that are deictic of hardship, matter. The tension between the dramatic portrayal of scientific experiments as a form of visual enquiry, vague images, and failed photographic plates marks a level of resistance to “a false doctrine that hides the truth about contingency and alternative possibilities for the past and future.”Footnote60 The transtemporal inscriptions of the environment that remain imprinted into photosensitive materials and images that “fail” to depict heroic adventures and the human experiences of expeditions offer alternative histories of exploration. The photographic records of expeditions form an ecosystem of material and social values — of labour and resistance, of the histories that unfolded without observation — that is integral to unpicking the imperialist politics contemporary to the expeditions that might otherwise be reiterated in the digital circulation and exhibition of the familiar and iconic images of early 1900s polar exploration.

Acknowledgements

This article was informed by my work as a Research Fellow at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Liz Watkins

Liz Watkins, University of Leeds. Watkins’ research interests include theories, technologies, and materiality of colour in cinema; sexuality and the image; contingency; and the history and ethics of colourisation and the archive. She has published essays on feminist theory, desire, excess, film materials and texts in Journal for Cultural Research and Parallax and has co-edited collections on Color and the Moving Image (New York: Routledge 2013), and Gesture and Film (London: Routledge 2017). Her book project, with Routledge, is on the materiality, immateriality of colour in cinema.

Notes

1. Stephen J. Pyne, The Ice: A Journey to Antarctica (University of Washington Press, 1986), 10; and Jennifer Fay, “Antarctica and Siegfried Kracauer’s Extraterrestrial Film Theory,” In Inhospitable Worlds. Cinema in the time of the Anthropocene (New York: OUP, 2018), 162–200, 163.

2. Fay, “Antarctica and Siegfried Kracauer’s Extraterrestrial Film Theory,” 193. Royal Society Antarctic Committee, Report to the Council 1887, p. 3. Royal Society Antarctic Committee Report to the Council 1887, A. H. Markham Papers MRK/46 (97), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

3. Robert Dixon, “What was Travel Writing? Frank Hurley and the Media Contexts of Early Twentieth-Century Australian Travel Writing,” Studies in Travel Writing 11 (2007): 59–60. Fine Art Society’s exhibition catalogue: The British Antarctic Expedition Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting F.R.G.S., December 1913. DF211/91 Natural History Museum. The catalogue describes an exhibition that toured cities including London, Cheltenham and Manchester.

4. Herbert George Ponting was hired as a professional photographer and self-named “camera artist” on Captain R.F. Scott’s British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13. The scientific expedition included the British journey to the South Pole in 1911–12. News of the fate of Scott, Wilson, Oates, Bowers and Evans on their return journey reached Britain in 1913.

5. Herbert George Ponting, The Great White South ([London: Duckworth, 1921]. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001), 170.

6. Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time, Modernity, Contingency and the Archive (Harvard University Press, 2003); and Mary Ann Doane, “The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity,” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18, no. 1 (2007): 128–151, 130.

7. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, “The Image of Objectivity,” Representations no. 40 Special Issue: Seeing Science (1992): 81–128.

8. Daston and Galison, “The Image of Objectivity,” 83.

9. Felix Driver, Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 10.

10. The Scott Polar Research Institute holds numerous magic lantern slides and photographs that were taken by H. G. Ponting and later used in lectures on meteorology and geography at the University of Cambridge given by members of Captain R.F. Scott’s fated South Pole expedition 1910–13. The status of these magic lantern slides, as copies in personal collections and the cost of digitisation projects, leaves these sub-histories of the social use of photography in education and as entertainment as sublimate to the iconic images associated with the expedition. Similarly, the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich holds a collection of over 200 glass plate negatives and 220 magic lantern slides from William Colbeck’s voyages as Captain of the relief ship “Morning” for Scott’s 1901–04 “Discovery” expedition, yet only a few have been digitised. The broader collection of photographic negatives (Paget plates, black-and-white glass negatives, rolls of film) and simulacra in different media (newsprint, in photo albums, framed prints, lantern slides) reveals a history of diverse practices and interests beyond the iconic images that typify the Heroic age of polar exploration. Iconic images include Frank Hurley’s iconic flashlight photographs of Shackleton’s ship, the Endurance, trapped in ice during the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1914–17. Further, photographs of the performance of science for camera in the work of Herbert G. Ponting were recorded as illustrations for the lecture tours that were intended to follow the return of Scott’s fated South Pole expedition 1910–13 and to recuperate the costs of exploration.

11. The archives that I refer to include the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge; South Australasian Museum, Adelaide; National Maritime Museum, Greenwich; British Film Institute; and Canterbury Museum in Christchurch New Zealand.

12. Miss Dawson-Lambton. “Album of Discovery Expedition photographs.” ALB0346.13. Greenwich: National Maritime Museum.

13. “To the South Pole with the Cinematograph”, British Journal of Photography LIX, no. 2729 (1912): 645–646, 646.

14. H. G. Ponting, “‘Gathering it in’: The Camera in the Far South” (Illustrated London News, August 26 Saturday, 1922), 318. The 1922 article is contemporary to the publication of Ponting’s written account of the 1910–13 Terra Nova expedition, titled The Great White South ([first published 1921] New York: Cooper Square, 2000).

15. Jennifer Tucker, Nature Exposed, Photography as Eye Witness in Victorian Science (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2005), 3.

16. Tucker, Nature Exposed, 232.

17. H.J.P. Arnold, “Antarctic Pioneer,” In With Scott to the South Pole, The Terra Nova Expedition 1910–1913, The Herbert Ponting Photographs (Bloomsbury, 2004), 203−223. 217. Arnold, as editor of the British Journal of Photography, is writing about the work of “camera artist” H.G. Ponting for the British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13. Orthochromatic photographs and film rendered blue in a lighter grey tone whilst the colour red tended to appear black.

18. “Captain Scott’s Expedition, Photographs at the Fine Art Society” (The Times, December 23 Tuesday, 1913), no. 40402, 11.

19. J.O, “The Scott Expedition in Photography,” In Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (Manchester, England), no. 17815 (December Wednesday10, 1913): 6. The numbers and descriptions of photographs in the MCLGA coincide with those in the Fine Art Society’s exhibition catalogue: The British Antarctic Expedition Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting F.R.G.S., December 1913, DF211/91 Natural History Museum, “Ponting Photographs, Public View Opened by Mayor of Cheltenham” (Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, February 14 Saturday, 1914), 1. Messrs W. H. Smith and Son on Cheltenham Promenade attended by 2000 people including 700 students from Cheltenham College and the Ladies’ college emphasising the educational potential of Ponting’s photographs.

20. J.O, “The Scott Expedition in Photography,” Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (Manchester, England) no. 17815 (December Wednesday10, 1913): 6.

21. Fay, “Antarctica and Siegfried Kracauer’s Extraterrestrial Film Theory,” 166.

22. Gunnar Iversen, “A View Aesthetic without a View? Space and Place in Early Norwegian Polar Expedition Films,” In The Image in Early Cinema, Form and Material, eds. Scott Curtis, Philippe Gauthier, Tom Gunning, Joshua Yumibe (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018), 102–108, 106. The images that Iversen reads as devoid of features, might, I suggest, also be studies of ice formations, ridges eroded by the wind, the remnants of unsuccessful experiments of interest to meteorologists and geographers, or the effects of deterioration, such as the fading of lantern slides and film prints under the heat of the projector lamp.

23. Iversen, “A View Aesthetic without a View?”, 106.

24. Rosalind Krauss, “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/View”, Art Journal 42, no.4 (Winter 1982): 311–319. 314 and 315.

25. Krauss, “Photography’s Discursive Spaces,” 317–318.

26. André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” What is Cinema?, Translated by Hugh Gray, 1 vols. (Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2005), 9–16. The complexity and connectedness of digital and analogue film and photography is discussed in texts by scholars and archivists including Giovanna Fossati, From Grain to Pixel: The Archival Life of Film in Transition (Amsterdam University Press, [2009] 2021).

27. Julia Martin and David Coleman, “Change the Metaphor: The Archive as Ecosystem,” JEP: The Journal of Electronic Publishing 7, no. 3 (2002). Models. Accessed 25 February 2021. https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0007.301. Martin and Coleman refer to the use of electronic databases and publications as an ecosystem in which writers, readers, speakers are actants.

28. Elizabeth Edwards, “Thoughts on the ‘Non-Collections’ of the Archival Ecosystem”, In Photo-Objects, On the Materiality of photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences, eds. Julia Bärnighausen, Constanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, Petra Wodtke (Firenze: Max Planck Research Library, 2021), pp.67–82.

29. Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith (New York: Harper & Row, 1976), 208-209.

30. William Colbeck, “Observations on the Antarctic Sea-Ice,” The Geographical Journal 25, no. 4 (April 1905): pp.401–405.

31. Clement Markham, National Antarctic Expedition Relief Ship. Pamphlet. Thomas Henry Tizard Papers, Royal Museums Greenwich. TI/48(5) An appeal for sponsorship authored by Sir Clement Markham as President of the Royal Geographical Society to fund relief ship for the Discovery, which overwintered in Antarctica, trapped in the ice.

32. Royal Society Antarctic Committee Report to the Council 1887 (minutes of meeting written by M Foster January 19, 1888), Admiral A. H. Markham Papers. MRK/46 (97). National Maritime Museum Greenwich.

33. Royal Society Antarctic Committee Report to the Council 1887 (minutes of meeting written by M Foster January 19, 1888), 3. Admiral A. H. Markham Papers. MRK/46 (97). Royal Museums Greenwich.

34. Colbeck’s naming of Haggitt’s Pillar and Scott Island is recorded in his journals, although the official status of this territorial act is unclear.

35. Krauss, “Photography’s Discursive Spaces,” 315.

36. Colbeck, “Observations on the Antarctic Sea-Ice,” 404–405.

37. Anon, “Practical Methods in Photographic View Publishing,” British Journal of Photography [BJP], (April 12, 1912): 284–285.

38. Doane 2007, 131.

39. Instructions from R. F. Scott to Charles Royds. 9 September 1902. MSS/88/003, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

40. Charles Royds, Journals of the “Discovery” Expedition. Thursday 9 October 1902. MSS/88/003. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. Edward, A. Wilson, Lecture Notes 1910–13, MS1225/3. Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge. Wilson was member of scientific staff on the Discovery 1901–04 and Terra Nova 1910–13 expeditions to Antarctica.

41. Robert Falcon Scott, “National Antarctic Expedition. Report from the Commander,” January 1902–February 1903. Report to the Presidents of the Royal Society and Royal Geographical Societies of England. P.18. T. H. Tizard Papers TIZ/49/11 (1). National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

42. Carsten E. Borchgrevink, “The “Southern Cross” Expedition to the Antarctic, 1899–1900,” The Geographical Journal XVI, no.4 (1900): 381–411, 385. Louis Bernacchi worked as the magnetic and meteorological observer alongside Colbeck on Borchgrevink’s British Antarctic Expedition 1898–1900 on the Southern Cross.

43. Louis Bernacchi, “The Eschenhagen Magnetic Instruments,” The South Polar Times (1902): 31. The SPT, written and printed in Antarctica, was orientated around the morale and sponsorship of the expedition.

44. For example, a superior mirage produced is produced by the different refractive index of warm air over cold water, where cold air close to the sea is denser with a higher refractive index.

45. Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Pierce, 2 Vols. Elements of Logic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1932), 159.

46. Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” 15.

47. Yusoff, “Antarctic Exposure: Archives of the Feeling Body,” Cultural Geographies 14/2 (2007): 211–33, 218 and 221. The damaged body is rarely visible in expedition narratives. A still photograph of Atkinson’s frost bitten hand, which is included in the EYE Filmmuseum print of Expeditie naar de Zuidpool as Ponting’s film of Scott’s fated South Pole expedition, is unusual and did not appear in copies held at the British national Film Archives or the BFI 2010 digital and photochemical restoration of the photographer’s 1924 edit The Great White Silence.

48. Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” 14; and Doane 2003, 3.

49. André Bazin, “Cinema and Exploration,” In What is Cinema? Volume 1, Translated by Hugh Gray (Berkeley and London: University of California: Berkeley and London, 2005), 154−163, 162.

50. Mawson Collection. Letter. 6 July 1914. AAE170. South Australasian Museum, Adelaide.

51. Cherry-Garrard, Apsley, “Mr H. G. Ponting (Obituary),” The Geographic Journal 85 (1935): 391.

52. Doane, 2003, 45.

53. Ponting. Letter to Apsley Cherry Garrard, 17 December 1913. MS559/102/2, SPRI, Cambridge.

54. Ponting [1921] 2000, 200. Ponting refers to Simpson’s notes on Professor Störmer’s method of photographing constellations, but cites the rapidity of lenses, photographic plates, and duration of exposure as problematic. Simpson was meteorologist on the expedition; his doctoral research was on the Aurora Borealis.

55. Herbert George Ponting. The Great White South, first published London: Duckworth, 1921 (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000), p.198.

56. J.O, “The Scott Expedition in Photography,” Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (Manchester, England) no. 17815 (December 10 Wednesday, 1913): 6; and Krauss, “Photography’s Discursive Spaces,” 31.

57. Exhibition Catalogue, The British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13. Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting FRGS (London: Fine Art Society, 1913), 10.

58. H.G. Ponting, Letter to Frank Debenham, 15 June 1926. British Antarctic Expedition 1910–13. MS280/28/7. Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge.

59. Ibid.

60. Fay, “Antarctica and Siegfried Kracauer’s Extraterrestrial Film Theory,” 173.

References

- Royal Society Antarctic Committee, Report to the Council 1887. A. H. Markham Papers MRK/46 (97), Royal Museums Greenwich.

- Discovery Expedition 1901-04, photograph album of albumen prints gifted to Miss Dawson-Lambton as benefactor of the expedition. Bernard Collection, ALB0346.13 National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

- “To the South Pole with the Cinematograph.” British Journal of Photography. LIX, 2729 (1912): 645–646.

- Anon. “Practical Methods in Photographic View Publishing.” British Journal of Photography (12 April 1912): 284–285.

- “Captain Scott’s Expedition, Photographs at the Fine Art Society.” The Times, issue 40402 (Tuesday 23 December 1913): 11.

- J.O, “The Scott Expedition in Photography.” Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (Manchester, England) Issue 17815 (Wednesday 10 December 1913): 6.

- The British Antarctic Expedition Exhibition of the Photographic Pictures of Mr Herbert G Ponting F.R.G.S., Fine Art Society exhibition catalogue. December 1913, DF211/91 Natural History Museum.

- “Ponting Photographs, Public View Opened by Mayor of Cheltenham.” Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic (Saturday 14th February 1914): 1.

- Arnold, H.J.P. “Antarctic Pioneer.” in With Scott to the South Pole, The Terra Nova Expedition 1910-1913, The Herbert Ponting Photographs. Edited by Beau Riffenburgh. 203–223. London: Bloomsbury, 2004.

- Bazin, A. What is Cinema? vol.1. Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 2005.

- Bernacchi, L. “The Eschenhagen Magnetic Instruments.” The South Polar Times (May 1902): 31.

- Borchgrevink, C. E. “The ‘Southern Cross’ Expedition to the Antarctic, 1899-1900.” The Geographical Journal. XVI, no.4 (1900): 381– 411.

- Colbeck, W. “Observations on the Antarctic Sea-Ice.” The Geographical Journal. Vol.25, no.4 (April 1905): 401–405.

- Daston, L. and Galison, P. “The Image of Objectivity.” Representations. no.40 Special Issue: Seeing Science ( Autumn 1992): 81–128.

- Doane, M. A. The Emergence of Cinematic Time, Modernity, Contingency and the Archive Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Doane, M.A. “The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity.” differences: a Journal of feminist Cultural Studies vol.18, no.1 (2007): 128–151.

- Driver, F. Geography Militant: Cultures of Exploration and Empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 2001.

- Edwards, E. “Thoughts on the ‘Non-Collections’ of the Archival Ecosystem.” in Photo-Objects, On the Materiality of photographs and Photo Archives in the Humanities and Sciences. edited by Julia Bärnighausen, Constanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, Petra Wodtke, 67–82. Firenze: Max Planck Research Library, 2021.

- Fay, J. Inhospitable Worlds. Cinema in the time of the Anthropocene. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Fossati, G. From Grain To Pixel: the Archival Life of Film in Transition. Amsterdam University Press, [2009] 2021.

- Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

- Iversen, G. “A View Aesthetic without a View? Space and Place in Early Norwegian Polar Expedition Films.” in The Image in Early Cinema, Form and Material, edited by Scott Curtis, Philippe Gauthier, Tom Gunning, Joshua Yumibe, 102–108. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2018.

- Krauss, R. “Photography’s Discursive Spaces: Landscape/View”, Art Journal vol.42, No.4 ( Winter 1982): 311–319.

- Markham, C. National Antarctic Expedition Relief Ship. Pamphlet (1901-04). Thomas Henry Tizard Papers TI/48(5), Royal Museums Greenwich.

- Martin, J. and Coleman, D. “Change the Metaphor: The Archive as Ecosystem”, JEP: the journal of electronic publishing voll.7, issue 32002 Models https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0007.301 - accessed 25 February 2021.

- Mawson, D. Letter. 6th July 1914. Douglas Mawson Collection AAE170. South Australasian Museum, Adelaide.

- Peirce, C. S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Pierce, Vol.2 Elements of Logic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1932.

- Ponting, H. G. “‘Gathering it in’: The Camera in the Far South.” Illustrated London News (Saturday 26th August 1922): 318.

- Ponting, H. G. Letter to Apsley Cherry Garrard, 17 December 1913. MS559/102/2, Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.

- Ponting, H. G. The Great White South, [first published London: Duckworth, 1921] New York: Cooper Square Press, 2000.

- Ponting, H. G. Letter to Frank Debenham, 15th June 1926. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13. MS280/28/7. Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge.

- Pyne, S. J. The Ice: A Journey to Antarctic. [first published University of Iowa 1986] University of Washington Press, 1998.

- Royds, C. Journals of the “Discovery” Expedition. Thursday 9th October 1902. MSS/88/003, Royal Museums Greenwich.

- Scott, R. F. ‘National Antarctic Expedition. Report from the Commander’. January 1902-February 1903. Report to the Presidents of the Royal Society and Royal Geographical Societies of England. T. H. Tizard Papers TIZ/49/11 (1). Royal Museums Greenwich.

- Tucker, J. Nature Exposed, Photography as Eye Witness in Victorian Science. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2005.

- Yusoff, K. “Antarctic Exposure: Archives of the Feeling Body.” Cultural Geographies 14/2 (2007): 211–33.

- Wilson, E. A. Lecture Notes 1910-13, MS1225/3. Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge.