Abstract

This article examines how digital photographic legacies affect and shape mourning and remembrance. The research sample comprises 32 interviews with bereaved persons, two expert interviews, 500 photographs, 200 screenshots, and social media contents. The qualitative, empirical research utilises constructivist grounded theory. Research data were gathered through intensive media-elicitation interviews, researcher-generated photography, and extant data collection. The findings demonstrate the profound impact of digital photographic legacies on mourning and remembrance, and that creatively working with inherited photographs is an essential task in bereavement. Digital photographs left behind empower mourners to recall everyday life in rich detail, to recognise the personality of the deceased, to feel close, and to reconnect with them. Further, inherited photographs may alleviate grief by allowing mourners to experience missed periods of the deceased’s life, to learn about their hidden facets, to be reassured about their good life, to answer questions of why, guilt, and time in cases of suicide, and thus to reconstruct the deceased’s biography. The article advocates a refocusing of photography research on photography’s commemorative function. It suggests that bereavement researchers and counsellors could benefit from further exploration of digital photographic legacies for grief and through a consideration of advancing therapeutic grief techniques which utilise digital photographs.

This article examines how digital photographic legacies affect and shape grieving, mourning, and remembrance of the bereaved. Walter showed how novel communication technologies have always reshaped ‘the social presence of the dead’ and how they were mourned and remembered.Footnote1 The advent of digital technology impacting the presence of the dead is reflected in the term ‘thanatechnology,’ coined by Sofka in 1997.Footnote2 Digital technology has been utilised for mourning and remembrance, which was recognised early in the academic discourse. In the 1990s, handcrafted memorial websites, virtual cemeteries, and memorial platforms emerged.Footnote3 In the early 2000s, social networks such as Myspace or Facebook were designed to celebrate life, but quickly also became places to mourn and remember the dead.Footnote4 In social networks the living and dead coexist unlike in dedicated memorial portals.Footnote5 The literature described both that mourning in social networks can cause distress, but also that comfort for the bereaved can be provided. Distress may result from the visibility of grief on social networks,Footnote6 when the dead intrude unexpectedly into the bereaved’s daily life through birthday reminders,Footnote7 or when fellow mourners stop posting.Footnote8 The comfort afforded by social networks is often discussed under the heading of ‘continuing bonds,’Footnote9 and the majority of literature demonstrated how posthumous relationships with the deceased can be sustained on social networks.Footnote10 Further, sharing grief both with friends and strangers in social networks is often reported as comforting.Footnote11 Finally, various disciplines discussed visions of digital immortality.Footnote12 The new visibility of grief through thanatechnology marks a major social transformation.

Digital legacies — the data we leave behind after our death — have become increasingly germane for survivors and academics through the proliferation of social networks.Footnote13 The studies that registered continuing bonds in social networks often addressed the texts, pictures, and videos that the deceased leave behind.Footnote14 Messenger applications like WhatsApp are increasingly being addressed.Footnote15 Various visions of digital immortality imagined the resurrection of the deceased through their digital legacies revived by algorithms,Footnote16 for example as chatbot.Footnote17 Further, there have been intense discussions about a ‘thanatosensitive design,’Footnote18 the planning or management of a digital legacy,Footnote19 the question of posthumous privacy,Footnote20 and the legal aspects of bequeathing and inheriting digital data.Footnote21 Digital legacies left behind on social networks have been analysed more frequently than unshared or secret digital legacies, but participants’ deceased often shared only the smallest portion of what became their later digital legacy during their lifetime. This article focuses on photographs; a subset of digital legacies. Conducting interviews at the homes of participants allowed me to browse through the deceased’s profiles and timelines on social networks, as well as their previously unshared and secret photographs. I learned not only the stories behind the photographs, but also realised their meaning for mourning and remembrance.

Since in the future most photographs will be inherited digitally, a need exists to explore the role of digital photography in relation to mourning and remembrance. This article contributes to a more holistic view about how digital photographic legacies impact the grieving, mourning, and remembrance of the bereaved. The empirically grounded findings may be useful for photography researchers, bereavement researchers, as well as those who deal with grief in their professional realms.

Methods and research sample

The empirical research utilised constructivist grounded theory.Footnote22 Research data were gathered through intensive media-elicitation interviews, researcher-generated photography, and extant data collection. The data were gathered between 2019 and 2022.

Constructivist grounded theory for thanatology

Research in thanatology commonly uses qualitative methods.Footnote23 Grounded theory’s research style and methods were chosen because they have a thanatological origin and they consider the complexity of everyday life.Footnote24

Grounded Theory was first presented in 1967 by Glaser and Strauss.Footnote25 On the one hand, the term ground theory stands for a methodology, a ‘style of doing qualitative analysis,’Footnote26 which urges the discovery of new theory not ‘by logical deduction from a priori assumptions,’Footnote27 but inductively throughout the analysis of research data. On the other hand, the term stands for the outcome of this methodology, i.e. for a theory that is grounded in data, and therefore is a grounded theory.

Researcher subjectivity is inevitable and indispensable when conducting interviews on death. Reichertz argued that by allowing some researcher subjectivity, interviews are no longer mere data collection, but vis-à-vis conversations, which foster the emergence of diverse and biographically meaningful perspectives.Footnote28 There were also a few situations in which I provided technical support to participants; for example, in accessing a hard drive of a participant holding her son’s digital legacy. Hearing about her problem of not having access, and being present while she viewed the data for the first time, led to valuable insights. Consequently, this research adopted Charmaz’s constructivist approach to grounded theory methodology,Footnote29 which allows for reflection on such situations and acknowledges the subjective role of the researcher.

Research sample and sampling strategy

The research sample comprises 32 interviews with bereaved persons and two expert interviews, one with a funeral director and one with a bereavement counsellor, resulting in 89 hours of audio recordings. A further 500 researcher-generated photographs, 200 screenshots, three blogs, six complete social media timelines, and 16 memorial videos comprise the extent of the research materials. One interview was conducted in Cyprus, the others in Germany.

Twenty-five bereaved interview participants are assumed female, 8 assumed male (participants were not asked). Sample age lies between 22 and 70; average age of 51. The age of the deceased lies between 13 and 82; average age of 41. Other demographic information, such as nationality, religion, education, or occupation, was not collected because it was not relevant for this research. The periods between the date of death and the interview range from a few months to 16 years, with an average of about 3.5 years. The causes of death are illness, organ failure, drugs, accidents, murder, and suicide. The deceased are the participant’s grandparents, parents, siblings, children, and partners.

The first participants were found via ‘“snowball” sampling’Footnote30 or initial sampling in grounded theory terminology, by contacting numerous, predominantly unknown people in person, by phone, by email, and via social media, about my search for interview participants. For instance, family and friends arranged six interviews with people with whom I had no previous contact; bereavement counsellors; mourning group leaders; priests; hospice employees; funeral directors; mourners who made their grief public on social media; or visitors of the Museum for Sepulchral Culture in Kassel, Germany. The search for participants was also published in magazines, in newsletters, in bereavement groups, or was tweeted by popular Twitter accounts dealing with death and mourning. Later, intentional theoretical samplingFootnote31 guided the search for specific bereavement cases. For example, after having started with interviews with participants who lost older persons, I looked for cases of child loss to compare whether children left behind different data; and I searched for cases of suicide, as I suspected a different role of digital legacies for such losses. The many contacts gained made theoretical sampling feasible; particularly helpful were bereavement counsellors who connected me to specific cases, and bereavement group facilitators who run offline or online groups and spread my request to the group.

Data collection

Twenty-six interviews lasting between 1 hour and 20 minutes to 5 hours, with an average of 2 hours and 40 minutes, were conducted face-to-face at the participants’ homes, 4 face-to-face but not at home, one by telephone, and one by email. In two interviews, a bereavement counsellor was involved whose questions and remarks became part of the analysis. All interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants and transcribed in their entirety by the researcher.

The intensive interviews were semi-structured. Deviations from the flexible interview guide were explicitly welcome, as they benefit explorative research and bring valuable insights.Footnote32 Following Charmaz’s recommendation to ‘devise a few broad, open-ended questions’Footnote33 allowed the participants to set topics themselves, lead to rich answers, and provided essential biographical context. The interview guide was constantly refined during the analysis; sufficiently answered questions were removed and new questions added. Reviewing digital legacies with participants was a crucial component of the interviews. Through media-elicitation, which is based on photo-elicitation,Footnote34 I reviewed with the participants not only photographs, but also messenger chats, social media timelines, or videos. This process elicited participant’s stories, meaning, and led to intimate, emotional, and dynamic conversations.

With researcher-generated photography, digital legacies and memory practices of participants were captured. Photographing was an integral part of the interviews and not a separate sequence. Taking photographs allowed for short pauses for reflection or emotional regrouping. My choice of motifs was predominantly informed by the general interview guide and by what the participants longed to show me. Typical photographs show the smartphones of the deceased, Facebook mourning posts on the computer of the bereaved, or memorial altars at home. The photographs enriched the study with visual data for analysis and facilitated an additional visual narration.

The research material was further developed by the collection of extant data including screenshots of messenger conversations, smartphone galleries, blogs, social media timelines, or memorial videos related to the interviews.

Constant comparative analysis and credibility

The analysis followed the comparative principle of grounded theoryFootnote35 and used initial and focused coding,Footnote36 categorising, memo-writing, diagramming, and theoretical sampling. After a series of maximum four interviews, transcripts and visual data were coded for actions.Footnote37 Visual data were not translated into text, but codes were applied directly to segments of photographs, screenshots, or videos. The same code system was used for transcripts and visual data. Focused coding and constant comparisons generated first hypotheses and informed theoretical sampling. The analysis was conducted with qualitative data analysis software (MAXQDA).

The constant comparative method ensures credibility.Footnote38 For the categories developed, ‘theoretical sufficiency’Footnote39 was achieved, acknowledging the limitations mentioned below. As needed, participants were recontacted to verify findings. Thick description and visual data retain participant voice in the findings and allow the reader to scrutinise the credibility of the grounded theory.

Transferability and limitations

This article focuses primarily on the opportunities of a digital photographic legacy for mourning and remembrance, and is thus limited in transferability in that it cannot say whether the findings are bound to gender, age, education, occupation, nationality, or religion of the participants because no comparisons were made with these properties. There is no potential bias to disclose.

Informed consent and anonymisation

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and no information about the research was purposefully withheld. All names of participants mentioned in this article are pseudonyms. The persons shown in the photographs and screenshots are not anonymised. Participants were informed about the context in which the images are published and have all consented to this unanonymised publication. Although ‘anonymity is often taken-for-granted as an ethical necessity,’Footnote40 the essence of an image can be lost through anonymisation and deprive the participants of their voice.Footnote41 Further, anonymisation itself can be unethical. For example, the loss of a child can be painfully highlighted by placing a black bar over the child’s eyes. Anonymisation could also contribute to the feeling that grief is something not to be talked about, not to be shown, but something of which to be ashamed.

Additionally, the consent of the deceased must be ethically considered and a decision made as to what extent their privacy can or should be ensured. The author was guided by the perspective of the bereaved, who knew the deceased well and often reflected on posthumous privacy in the interviews.

Ethics approval

This research is being conducted at the Cyprus University of Technology and part of the European training network H2020 POEM, with Universität Hamburg as the lead university. The ethical procedures of the research were submitted to and approved by the Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Humanities (EKGW), Universität Hamburg on 2 July 2019.

Findings

Participants inherited photographs which their deceased shared publicly or semi-publicly on social networks such as Facebook, Snapchat, or Instagram. They found photographs contained in private dialogues in messengers like WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger. Posthumous photo sharing on social networks and in messengers was an important source of new photographs for survivors. But participants also inherited numerous previously unshared photographs, which the deceased perhaps intended to remain secret. Such photographs were saved in clouds like Google Photos or iCloud Photos, or in local folders on the deceased’s devices. The following insights show how participants mourned and remembered their deceased with these digital photographic legacies.

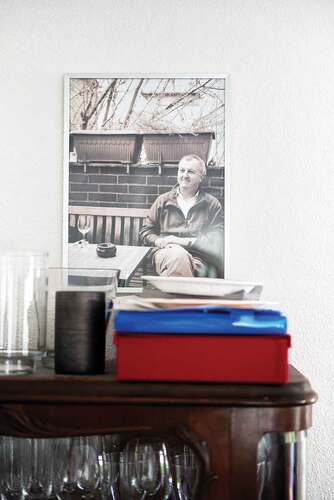

Snapshots — remembering everyday life

Participants often interrupted scrolling through photo galleries when everyday snapshots appeared — they were their favourite kind of photographs. Annette affirmed: ‘Snapshots … and these are now beautiful memories; they hang in my living room.’ Everyday snapshots captured the partner barbecuing, gardening, drinking coffee, or having breakfast under a parasol. They captured the child painting the new flat, baking, or partying with friends. They captured the parents at their workplace or the grandparents on Christmas Eve. I spoke with Ulrike about a photograph of her partner sitting on the terrace (). On the table is an empty glass of wine, an ashtray, a packet of cigarettes, and a lighter. This mundane photo taken at home was her favourite, because it shows how he usually sat on this terrace, usually drank a glass of wine there, and usually smoked cigarettes there. She told me he was a homebody, rarely wanted to go out, and preferred to sit on that terrace. For her, this photograph represents her partner because ‘he looks the way he looks, normal, the way he looked, and doing what he always did.’

Fig. 1. An everyday snapshot of Ulrike’s partner sitting on the terrace.Photograph taken by the author (2020).

Such photographs allowed participants to recall the everyday life once shared. Oliver treasured ‘especially the little things,’ was interested in ‘the very normal life story,’ and less in photographs his son took at festivals or on holidays. Oliver set up a Facebook memorial profile for his son and posted an everyday photograph showing him on the terrace at home ().

Fig. 2. A screenshot of a post on the Facebook memorial profile for Oliver’s son.Screenshot taken by the author (2021).

Other participants, too, recognised their deceased particularly in everyday portraits and selfies. Mareike described a snapshot characteristic of her partner (): ‘He was a coffee fan, and I thought that was a perfect snapshot, him with such a nice latte macchiato, and yes, it matches him … . So this is such a typical photo.’

Fig. 3. An everyday snapshot of Mareike’s partner drinking coffee.Photograph taken by the author (2020).

Mareike told me that she has fond memories of this beautiful day and that precisely such memories help her to get through tough days. Recalling the stories of everyday life also evoked deep emotions in Gabriele, who said while scrolling through WhatsApp: ‘So you just have intense experiences when you look at something like that. I find it much, much more intense than when I go to the grave and look at the flowers.’ She told me that these photographs were ‘really taken from everyday life.’ Especially when the end of life was dominated by illness, it was healing for participants to affirm everyday life in the photographs. Ulrike said about a photo showing her partner smoking in front of the hospital: ‘I really, really have to laugh … I find the photos great, because it also shows that normality has somehow not been lost even through this whole ordeal.’

Remembering normality can also be significant when the loss occurred under particularly tragic circumstances. Jelena shared everyday photographs of her daughter, who was murdered, on a Facebook memorial group ().

Fig. 4. A screenshot of a post in the Facebook memorial groupfor Jelena’s daughter. Screenshot taken by the author (2022).

The comment in says:

Dear {name of mother}, Your wish was that your daughter would not be remembered as the ‘murdered girl’! Because of your courage to put such pictures in this group, she is firmly anchored in our minds and hearts as a smiling, living sunshine. I admire you and wish you with all my heart that you will find a way for life to bring smiles and happiness back into your soul.

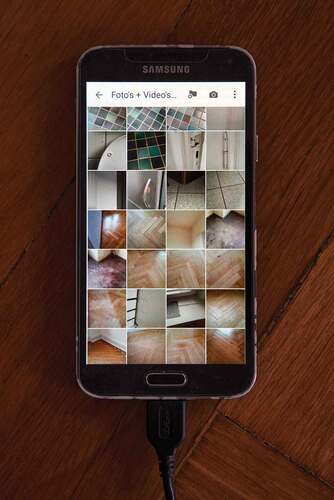

The comment shows that everyday snapshots can be crucial to direct mourning and remembrance. Isabella also learned to cherish her partners’ snapshots of construction sites () which she previously found boring and distant; later they appeared comforting because they symbolise her partner, an architect.

Fig. 5. A photograph of the smartphone of Isabella’s partnershowing the gallery app. Photograph taken by the author (2021).

However, when participants had no connection to the photographs, they had no stories to tell and therefore found them less interesting. Leonie said about photographs she inherited from her brother and his partner: ‘I don’t have to keep them, because for me, I don’t connect any memories with them.’

A Feeling of closeness — reconnecting to the deceased

Susanne told me about the extensive Facebook timeline her son left behind: ‘Yes, that is one of the few things where I can still see him somehow alive.’ Also Helena feels close to her son when looking at his Facebook timeline: ‘There I can feel close to him, I look for example, at his photos and I know, sometimes he told me stories about certain things, and I can look at the photos and think: oh yes, you told me about that.’ The photographs allow her to step back in time: ‘Then I am not in the here and now of the third of March two thousand and twenty, but there. I am a silent observer and there he lives on a bit.’ Jelena could also feel a connection to her daughter through photographs: ‘These personal images were simply something where I had the feeling that she is still there. She is here now, she is helping me now. So, yes, that was important for me.’ Alexandra feels close to her deceased grandfather and the family through his photographs: ‘By looking at these pictures … . You can feel them closer to you. Because you revive like all the moments and everything.’ She also feels closeness because his photographic legacy is ‘very representative of who he was’ (). She saw his view of the world through his photographs and could recollect what was important to him: ‘I mean he was not taking pictures of landscapes or anything, it’s just family things, and himself, he was even taking selfies sometimes. So, yeah, it’s emotional because it’s just him and the family.’

Fig. 6. A screenshot taken on Alexandra’s grandfather’s tablet showing family photographs. Screenshot taken by the author (2019).

For Alexandra, the family pictures convey closeness and bonding. Despite the often large number of inherited photographs, other participants nevertheless missed images that show the family as a whole. Susanne told me that she deeply misses a photograph showing her son together with his sister, father, and herself:

Where all four of us are together. Not posed, but in situations that we just spent together or so. I think a lot is missing. Because we spent time together, but no one took a photo because we were just among ourselves and no one thought about taking a photo.

Photographs also empower participants who have lost their partner to recall the closeness and intimacy they once shared. Through the inherited photographs, Annette could understand how her partner saw the world and how they complemented each other:

And these everyday pictures often showed me or showed me how {name of the deceased} saw the world; what was important to her. You know, for example, if we had gone for a walk and there had been, I don’t know, a sunset, a sunflower, and a cemetery. Then I would probably have photographed the sunset and {name of the deceased} photographed the cemetery.

Partner selfies convey closeness. Ulrike’s favourite selfie is one ‘where it also looks like really intimate love somehow.’ A digital photographic legacy may also hold photographs of once shared sexual experiences, which are likely more prevalent due to smartphone proliferation. Jasmine is grateful for the close-ups and the sexual records:

I mean, you’re always so afraid that you’ll forget … . That you can no longer remember details, for example … . How his eyebrows were actually shaped or something like that, and that’s what photos are really good for, and I think that also concerns the whole rest of the body, of course.

She looked at the photographs and watched the short videos immediately after her partner passed away. Since then, she has kept them at a distance, because they painfully remind her that she can no longer have sex with him, yet she is ‘crazy happy’ that they exist.

Unknown photos — reconstructing life

Some participants already knew the photographs of their loved ones before they died, but for others the photographic legacies were partially or entirely unknown. Unknown photographs enabled some participants to reconstruct missed periods of the deceased’s life. Konstantin had little contact with his father in the last years before he passed away, but his father’s smartphone held many photographs of everyday life. Konstantin wanted to learn about his father’s daily life and said about the inherited photographs: ‘Somehow they were so real for me, really as if, yes, I can’t describe it, but, yes, as if I were actually somehow there and seeing everything in real time and witnessing it.’ This experience taught him for his own photographic practice that ‘banal pictures from everyday life, moments … are the most important ones.’ Previously unknown photographs were also valued by bereaved parents, because they allowed parents to learn something new about their child. Also Louis learned about the times of his daughter’s life that he missed through the photographs she left on her smartphone and on social media, which was an essential aspect of his coping with her death:

I hadn’t heard anything from my daughter for a very long time. I’d say, I’m missing a lot of periods in her life that I don’t know about. And I try, or tried, to imagine step by step, through the pictures and what was there, what her life was like at that time. Where it was difficult, where it was good.

Louis is interested in photographs that are characteristic of his daughter and her life (): ‘They indicate a bit what she liked … lovingly wrapping things or writing, also just the great handwriting she had, together with her friends, or such details here, baking and so on she liked to do.’

Fig. 7. A photograph of a memorial book Louis made for his deceased daughter with photographs from her digital legacy. Photograph taken by the author (2020).

Another parent, Susanne, cherishes her son’s selfies and described the unique character of smartphone photography:

He loved taking selfies, in all kinds of variations … . And there were really a lot of them on it [the smartphone] that I didn’t know at all. And each one was like such a, like such a treasure. Yes, something new from my child, which will never be possible for me again.

Silke also appreciated having her son’s life being revealed to her through his various photographic records and those she received from his friends. But she also described how painful the point was when she realised there were no more new pictures to discover: ‘Now it’s just like that, there’s always pain involved, now there’s really nothing more to come.’ Whether it brought positive or challenging insights, discovering previously unknown photographs enriched participant’s ability to sense the lives of the deceased more completely.

Happy and sad photos — balancing emotions

Some participants were relieved to view the good life of the deceased. Maike had a distanced relationship with her father before he passed away, and explained:

It helped me to see that he … that he was happy. That, that would have hurt me more if I had somehow found out, okay, he was totally suffering last month … . There was no big drama in his life, but he just lived his life and so, it was just normal days before.

Even when the end of life was marked by depression and caused by suicide, discovering the positivity in the lives of the deceased within their photographic legacies provided relief for participants. For Sandra, who lost her daughter to suicide, it was important to see that her child had a normal life beyond depression:

Just nice, when she parties with them, laughs, and it makes me feel good to see that she was a completely normal young person who lived her life. That you don’t see her with this depression, as you often saw her at home. Somehow. That is worth its weight in gold for me.

Identifying happy photographs and moments also provided relief for participants who lost a person whose end of life was marked by serious illness. The photographic legacies participants inherited, as well as their own photographic collections, included, however, not only happy photographs, but also photographs depicting depression and illness or post-mortem photographs of the deceased. Both happy and sad photographs can be important for grief, mourning, and remembering, and participants tried to balance their emotions through curating their digital photographic collections. Mareike always carries a collection of her favourite photographs of her deceased partner on her smartphone, which includes mostly happy pictures, but also some depicting his illness:

Mostly I think I chose the pictures according to what event I associated it with, that I know, oh, he was super happy in that moment … . I have a few photos in this collection where he was no longer feeling so well, I must admit, but they still belong to it, that’s also part of him, there are not only good days and good moments. Of course … I want that, for me too, that the beautiful memories prevail.

Doan last saw his mother on her deathbed and is thankful for the happy pictures he inherited on her smartphone:

I still remember when I saw her for the last time and it wasn’t really good, and I know that it won’t be helpful for me if I only remember that part … . You don’t have to remember that part because you have this version of your mum. Happy, smiling, having some good time with her friends and all that stuff.

In contrast to some participants, Doan had no photographs depicting his mother’s illness. He was not aware that she was seriously ill, and would have liked to have had such photographic evidence to better comprehend that it was indeed her illness that led to her death:

I mean, like it will help me to release this pain because I still have this kind of belief that she wasn’t sick. But I guess if I had this photo when let’s say she was suffering, or she was hospitalised, she was going to the doctor and got this assessment, or something like that. It would help me, I guess, to know that, to accept the fact that she was sick.

As Mareike said, the illness may also be part of the deceased’s life story, and Doan pointed out why it can be difficult if this part has not been documented. Anna treasures a photograph () that expresses her daughter’s illness as well as her zest for life: ‘And this is a very special picture, because despite her illness, she radiates so much joy of life and was so happy. And that picture is my favourite.’

Fig. 8. A photograph of Anna’s tablet showing photographs of her daughter. Photograph taken by the author (2020).

At the time of the interview, Anna could look at this photograph (), however, she found it difficult to look at ‘photos from her happy time.’ She could reassure herself about the good life of her daughter, but, unlike other participants, she could not enjoy such photographs, because they emphasise the loss of such a happy soul: ‘These thoughts always come up, why were you just torn away from here, from the midst of the life that you still had in front of you.’ Balancing happy and sad photographs helped participants to direct their emotions of grief for their loved ones.

Records of intimate feelings — understanding suicide

Digital photographic legacies allow survivors to reassure themselves about the good life of the deceased, but also to understand hard times in life. Seven participants lost loved ones to suicide. For most of them, the suicide was completely unexpected — ‘out of the blue,’ as two participants recounted — and they had pressing questions related to why, to feelings of guilt, and to timing. They wondered whether there was an explicit reason for the suicide and wanted to understand what had happened in the immediate past. However, participants did not consider a single incident as causal and then wanted to comprehend was going on in the person’s mind, as well as their thoughts and feelings. Often it was a question of being able to recognise and understand a depression posthumously. Concerning guilt, participants asked whether they themselves or another person might have been responsible, what they may have done wrong, or whether the deceased blamed them. Questions of time included whether it was a spur-of-the-moment decision and when the suicidal thoughts started. Study participants were able to answer many of these questions through reviewing the intimate digital legacies of their deceased.

Sandra gained understanding of the reasons for her daughter’s suicide through photographs left on her smartphone. She encountered ‘completely different lives’ of her daughter there and could recognise her invisible depression retrospectively, especially in selfies:

These are all selfies she took of herself … . But for me, of course, it was important to see that again in relation to her illness. To just see and to realise that what she is doing there is sick, that she was simply very ill; and that was not clear to me.

The photographs are both painful, because they show her daughter suffering and helpful because they make her illness visible. Through the photos the mother acknowledged her child’s depression as illness. While wondering about questions of time, her mother reflected (): ‘There she photographed herself already in depression, there she was already not well.’ Later Sandra realised that her daughter already knew at the time of taking the photograph that she would die by suicide. Susanne also wished to understand her son’s death by suicide and was filled with questions:

You’re starting this search for the causes, why. The big question of why, the big question of guilt. You want to understand, you want to be able to comprehend what was going on inside him. It is different when you accompany someone in an illness, there is always this exchange. But when someone has the illness [named] depression, this exchange is often missing, because then the person often withdraws or says, no, everything is okay. And as a mother, it was incredibly important for me to be able to understand that. What was going on.

Fig. 9. A selfie of Sandra’s daughter on the daughter’s smartphone.Photograph taken by the author (2020).

She could grasp her son’s depression through selfies he left behind. He took proud selfies in front of his car, but also photographed himself crying. The sad selfies hurt her, but at the same time she was grateful to see them because ‘in this way you were allowed to see the tears that he so often hid.’ Like for other participants, it was important for her to understand that there was no explicit cause for the suicide. Through the photographic legacy she was able to determine the duration of the depression and to realise that the suicide was not related to recent events, such as the break-up with his girlfriend, but that his death wish had been present much earlier.

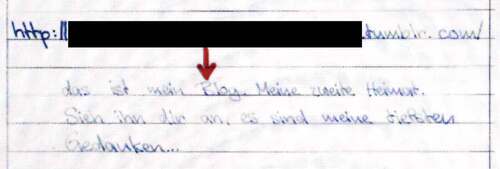

Similarly, Verona was able to experience the depression of her daughter via a Tumblr blog, to which her daughter left a link in her farewell letter ().

Fig. 10. A photograph showing a part of Verona’s daughter’s farewell letter, which was scanned and displayed on Verona’s laptop. Photograph taken by the author (2020).

Underneath the link provided in the farewell letter, her daughter wrote: ‘This is my blog. My second home. Have a look at it, these are my deepest thoughts …’ After reading the letter, Verona accessed the blog. She reflected on the impact of the details she encountered there:

It was also a need to understand what was going on … . I didn’t know that she had her own blog on this Tumblr, on this platform. Yes, and she wrote me these access data and wrote, here are my true feelings, and, yes. And then I logged in there and basically really got to know a whole new child again. Yes. And there was her very sad and depressed side in it. Yes, and we didn’t see that here at all … . And it was very, very depressing. There are really, yes, you see pictures of people falling off roofs, well, and instructions on how to tie the right knot and everything very, very depressing, really, yes, very bleak.

The blog included images from the web, such as depressing memes or pictures of self-harm, but also Verona’s daughter’s own photographs, which showed her weight loss and sadness. Nevertheless, delving into the blog was crucial to her ability to cope with the suicide:

For me, it was indeed important to have this blog, which is indeed something that was also important for my path of mourning, you know, if she hadn’t written this to me, I would never have understood her, I would never have known why, how come, what for, well, I would never have got to know her other side.

She also inherited photographs on her daughter’s computer and commented about one (): ‘There she already looks different, you know … she has become really transparent somehow, yes. So I think there’s already a sadness present, you know, and that’s really shortly before.’

Fig. 11. A photograph of Verona’s laptop showing a photograph from her daughter’s digital legacy. Photograph taken by the author (2020).

Recapitulating on her daughter’s digital photographic legacy, Verona said:

It was as if I could look through her eyes, you know, and also feel her sadness, this infinite hopelessness, without suffering from depression myself, you know, but I could feel it all. And that was totally valuable for me, yes, because that was totally important for my path, because then there weren’t so many unanswered questions.

Verona’s experience shows that understanding depression may involve learning about the deceased posthumously and that reconstructing their identity can help to integrate both the known and the unknown sides of the deceased.

Discussion

Digital photographic legacies allow the reliving of everyday life with an unprecedented level of fidelity. Banks said that diaries include intimate details, and also record daily routines and a particular way of life, which might be of great interest to descendants.Footnote42 The findings suggest that today digital photography leads to diary-like records that, at least in part, replace written diaries and provide bereaved people with a resource for mourning and remembrance. Bassett also found that the everydayness in messenger communications comforted mournersFootnote43 — my findings highlight that photographs play an important role in this regard. Remembering the ordinary was usually more intense for survivors than recollecting the extraordinary. Breckner argued that people try to recognise a person and their character through their face,Footnote44 for which selfies are a novel and powerful resource. My findings about digital photographs support Bassett’s argument that a digital legacy holds the ‘essence’ of the deceased.Footnote45 Especially when the last time before death was dominated by illness, it was healing for participants to realise through photographs that everyday life prevailed. For participants who have lost a loved one under particularly tragic circumstances, everyday snapshots of normal life were crucial to direct remembrance and to overlay the tragic shadows of loss. The ordinary must not be mistaken with the banal, the light, the boring, because it is precisely in everyday life in which joys and dramas unfold — birth, love, illness, and finally death.

Mourning is a constant balancing of closeness and distance in which digital photographic legacies play a pivotal role as they hold a unique potential for reconnecting with the deceased. Photographs allowed participants to step back in time, but also to feel the deceased present and to reconnect with them by witnessing their view on the world — all of which brought them relief. Research on continuing bonds in social media also addressed photographs. Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy analysed suicide bereavement in social networks and found that the data left behind on Facebook can bring the deceased back, make them feel close to survivors.Footnote46 My findings add that photographs left behind, even when not embedded in social networks, can facilitate continuing bonds. On the other hand, the closeness that digital photographs convey sometimes highlighted the loss too vividly and were too painful to view — participants kept these photographs at a distance for some time. While the need for closeness in continuing bonds has often been described, the need for distance is less frequently discussed. Ways to balance closeness and distance in continuing bonds could be a worthy objective for future research.

Reviewing previously unknown digital photographic legacies enabled participants to experience and reconstruct missed periods of the deceased’s daily life in rich detail. Reconnecting with the deceased through at times a lengthy review of these photographs was comforting for many participants. Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy made a similar conclusion for photographs left on Facebook, describing the feeling of the bereaved as ‘still getting to know their loved one.’Footnote47 Bereaved parents in particular felt uplifted to discover fresh and unknown photographs, because they allowed them to once again experience something new about their child. Inherited smartphones, social media timelines, or photo sharing were significant sources for novel and moving stories about their children. However, the point at which survivors realise that there are no new photographs can be painful. Some unknown photographs can also be difficult to cope with, for example, those showing drug use or self-harming behaviour. Nevertheless, looking at the entirety of the photographic material was crucial for the bereaved to better understand the deceased. Reconstructing the deceased’s life and identity can be a prerequisite for a lasting posthumous relationship. Walter showed that a durable biography can be constructed through conversation with others;Footnote48 later studies highlighted the role of the internet for such conversations,Footnote49 and my research demonstrated that even a private dialogue with digital photographs left behind can be crucial in this process of identity construction.

Balancing happy and sad photographs of the deceased was especially important to participants when the past relationship was distant or when the end of life was marked by serious illness, depression, or suicide. My research found, consistent with other studies,Footnote50 that discovering and viewing happy moments can be uplifting in times of grief. But happy photographs can also be painful when they emphasise the loss, and, conversely, painful photographs can also provide relief when there is a need to accept illness and death. Both happy and painful photographs can be important for mourning, and remembering, and participants utilised them to balance the spectrum of emotions of grief.

Regarding identity, Jordan showed that in the case of a suicide the world of the survivor, including the image of the person who committed suicide, can become shattered.Footnote51 Making matters worse, as Jordan notes, most survivors initially know little about the causes of suicide.Footnote52 In his article on postvention, photography is only mentioned briefly. My findings show that digital photographic legacies can significantly aid postvention. Participants who lost a person to suicide were often haunted by feelings of guilt and questions about reasons and timing. Photographs the deceased left behind were of tremendous help in finding answers to these questions. Through photographic records of intimate feelings participants were not only able to recognise a once invisible depression retrospectively, to acknowledge depression as an illness, and to determine when the depression began, but also to reconstruct the identity of their deceased. The new identity then integrated both the familiar and the unknown depressive sides of the deceased; only afterwards could mourning and remembrance commence.

Conclusion

This article examined the benefits and challenges contemporary photographic practices hold for mourning and remembrance. In 2005, McIlwain noted that ‘it becomes increasingly necessary to understand the relationship between “death culture” and “visual culture.”’Footnote53 Since then, much has been written about how we photograph today, but much less about how we mourn and remember with these photographs tomorrow. Researchers often described today’s photography as a phatic act, in the service of ephemeral communication and identity formation,Footnote54 but whether these photographs, such as selfies or snapshots on Instagram, are valuable for mourning and remembrance has been less explored.Footnote55 The photographs left behind today are characterised by an everydayness and intimacy like never before, and the article shows empirically that this new quality of photography can have a profound impact on how the deceased are mourned and remembered.

The findings demonstrate how a digital photographic legacy can empower mourners to recall everyday life in rich detail. Particularly when the time before death was dominated by illness, it can be healing to affirm everyday life in photographs. Engaging with the photographic legacy allows survivors to reconnect with the deceased and thus facilitates continuing bonds. Further, inherited photographs may alleviate grief by providing a resource to experience and reconstruct missed periods of the deceased’s life or to reassure oneself about their good life. Both can be particularly important when the end of life was marked by serious illness, depression, or suicide. For bereaved parents it can be uplifting to discover new photographs of their children. In cases of suicide, photographs left behind can be key to answering questions of why, of guilt, and of time, and thus significantly aid postvention.

Van Dijck noticed that ‘taking photographs seems no longer primarily an act of memory intended to safeguard a family’s pictorial heritage,’Footnote56 but she also said that the new role of photography ‘does not annihilate photography’s traditional commemorative function.’Footnote57 This article showed that the new role of photography does not counteract mourning and remembrance, but on the contrary, almost automatically leads to digital photographic legacies that are invaluable for the bereaved. Research on photography could refocus on the commemorative function of photography and its impact on how people mourn and remember loved ones in the future.

The findings of this article may provide valuable insights for bereavement researchers, bereavement counsellors, and for mourners themselves. The article shows that for many bereaved people, examining, engaging with, and creatively working with inherited photographs is an essential task in bereavement. Inherited digital photographs that are as everyday as they are intimate, enable mourners to retrace the life of the deceased, to either reaffirm their perspective on that life, or to question and change their understanding of the deceased’s identity, which in turn might lead to a changed coping with grief. Creative work with photographs can further provide a place for grief, continue the dialogue with the deceased, and keep them in the present, for example, in a digitally created collage on the home screen of the smartphone or in a remembrance video published on YouTube. These findings offer stimuli for grief therapy, and researchers and professionals in the field may develop therapeutic techniques that utilise inherited photographs. In particular, existing therapeutic techniques based on photography could benefit from including digital photographic legacies as a new and extensive resource. For example, ‘PhotoTherapy’Footnote58 already uses snapshots and ‘photobiographical collections’Footnote59 to stimulate conversations in therapeutic counselling and to bring healing by offering a reality but at the same time encouraging to perceive this reality as one among multiple possible others. This power of photography is further enhanced by the wealth of photographic legacies left on smartphones and social media, and therapeutic techniques could benefit not only from the vast amount of photographs left behind but notably from their everydayness and intimacy.

For hospice workers and for those who see death coming, the findings may be instructive and enable them to turn their lens toward the details of everyday life and to intimate moments.Footnote60 Some participants especially treasured partner selfies and portraits showing the whole family with all family members — and it was precisely these photographs that were often sorely missed by others who were deprived of the chance to take such a photograph by the death of their loved one. Finally, the article is an invitation to all to reflect upon our own photographic practice and to determine how we want to remember our loved ones and we ourselves want to be remembered.

Acknowledgements

This article uses data gathered for my dissertation conducted at the Cyprus University of Technology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lorenz Widmaier

Lorenz Widmaier is a PhD student in the Department of Multimedia and Graphic Arts at the Cyprus University of Technology. He holds a research fellowship from the European Training Network H2020 POEM, which researches participatory memory practices. He attained an MA in Photography and Urban Cultures from Goldsmiths College, UK and a BA in Communication & Cultural Management from Zeppelin University, Germany. His research interests include thanatology, visual sociology, digital media, and photography.

Notes

1. Walter, “Communication Media,” 216.

2. Sofka, “Social Support Internetworks,” 553.

3. Banks, Future of Looking Back; Gebert, Carina Unvergessen; Lynn and Rath, “GriefNet”; Roberts, “Living and Dead”; Sofka, “Social Support Internetworks”; and Vries and Rutherford, “Memorializing Loved Ones.”

4. Writings that illustrate opportunities and functions of grieving in social networks are: Bouc, Han, and Pennington, “Why are They Commenting”; Brubaker, Hayes, and Mazmanian, “Orienting to Networked Grief”; Moore et al., “Social Media Mourning”; Willis and Ferrucci, “Mourning and Grief”; and Walter et al., “Does the Internet Change.”

5. Kasket, “Continuing Bonds.”

6. Brubaker, Hayes, and Dourish, “Beyond the Grave.”

7. Moyer and Enck, “Grief Too Public.”

8. Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy, “Continuing Social Presence,” 80–81.

9. Klass, Silverman, and Nickman, Continuing Bonds.

10. Balk and Varga, “Continuing Bonds”; Irwin, “Mourning 2.0”; Kasket, “Continuing Bonds”; and Kasket, “Facilitation and Disruption.”

11. Carroll and Landry, “Logging on Letting Out”; Gibson, “YouTube and Bereavement Vlogging”; and Walter et al., “Does the Internet Change.”

12. The amount of literature is too extensive to cover in this article. A basic overview is provided in: Savin-Baden and Mason-Robbie, Digital Afterlife.

13. Three major works on digital legacies deserve special mention. First, Banks’s The Future of Looking Back, published in 2011, one of the first monographs approaching the potential of a digital legacy for remembrance. Second, Kasket’s All the Ghosts in the Machine, which comprehensively illuminates the significance of digital legacies for the bereaved. Third, Bassett’s The Creation and Inheritance of Digital Afterlives, which examines the role of tech companies, digital creators, and the bereaved.

14. Banks, Future of Looking Back; Bassett, Digital Afterlives; Jacobsen and Beer, Automatic Production of Memory; and Kasket, All the Ghosts.

15. Bassett, Digital Afterlives; and Kasket, All the Ghosts.

16. Fordyce et al., “Automating Digital Afterlives”; Leaver, “Posthumous Performance”; Meese et al., “Posthumous Personhood”; Savin-Baden and Burden, “Digital Immortality”; and Sofka, Gibson, and Silberman, “Digital Immortality.”

17. Riesewieck and Block, Die digitale Seele, DADBOT.

18. Hemphill, “Dying, Death, and Mortality,” 2467. For example: Bassett, Digital Afterlives; and Brubaker, “Death, Identity, Social Network.”

19. For example, Carroll and Romano, “Your Digital Afterlive”. But also many non-academic resources should be acknowledged like Sieberg and Steiber, Digital Legacy.

20. Harbinja, “Post-Mortem Privacy 2.0”; and Morse and Birnhack, “The Posthumous Privacy Paradox.”

21. Funk, Das Erbe im Netz; and Rycroft, “Legal Issues.”

22. Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory.

23. Cupit, “Research in Thanatechnology,” 207.

24. Glaser and Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid., 21.

27. Ibid., 3.

28. Reichertz, Qualitative und interpretative Sozialforschung, 82.

29. Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory.

30. Mason, Qualitative Researching, 142.

31. Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory, 189.

32. Benkel, Meitzler, and Preuß, Autonomie der Trauer, 103.

33. Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory, 26.

34. Harper, “Talking about Pictures,” 13.

35. Glaser and Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory, 104.

36. Charmaz, Constructing Grounded Theory, 42.

37. Ibid., 136.

38. Glaser and Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory, 230.

39. Dey, Grounding Grounded Theory, 257.

40. Moore, “The Politics and Ethics,” 331.

41. Allen, “Losing Face?”

42. Banks, Future of Looking Back, 13.

43. Bassett, Digital Afterlives, 112.

44. Breckner, “Zwischen Leben und Bild,” 232-3.

45. Bassett, Digital Afterlives, 111–2.

46. Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy, “Continuing Social Presence,” 79.

47. Ibid.

48. Walter, “Bereavement and Biography,” 7.

49. For example: Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy, “Continuing Social Presence,” 81; and Finlay and Krueger, “A Space for Mothers,” 21.

50. Bailey, Bell, and Kennedy, “Continuing Social Presence,” 76; and Stein et al., “Community Psychology,” 10.

51. Jordan, “Grief After Suicide,” 350.

52. Ibid., 356.

53. McIlwain, When Death Goes Pop, 220.

54. Champion, “Instagram”; van Dijck, “Digital Photography”; and Villi, “Visual Chitchat.”

55. An exception, e.g.: Hjorth and Cumiskey, “Selfie Eulogies.”

56. van Dijck, “Digital Photography,” 57.

57. Ibid., 68.

58. Weiser, Phototherapy Techniques.

59. Weiser, “PhotoTherapy Techniques in Counselling,” 23.

60. Shuber and Kok, “Hospice Photography’s Effects.” See also the resources provided by the Digital Legacy Association: https://digitallegacyassociation.org.

References

- Allen, Louisa. “Losing Face? Photo-Anonymisation and Visual Research Integrity.” Visual Studies 30, no. 3 (2015): 295–308. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2015.1016741.

- Bailey, Louis, Jo Bell, and David Kennedy. “Continuing Social Presence of the Dead: Exploring Suicide Bereavement Through Online Memorialisation.” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 21, no. 1–2 (2015): 72–86. doi:10.1080/13614568.2014.983554.

- Balk, David E., and Mary A. Varga. “Continuing Bonds and Social Media in the Lives of Bereaved College Students.” In Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice, edited by Dennis Klass and Edith M. Steffen, 303–316. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Banks, Richard. The Future of Looking Back. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 2011.

- Bassett, Debra J. The Creation and Inheritance of Digital Afterlives: You Only Live Twice. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

- Benkel, Thorsten, Matthias Meitzler, and Dirk Preuß. Autonomie der Trauer: Zur Ambivalenz des sozialen Wandels. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2019.

- Bouc, Amanda, Soo-Hye Han, and Natalie Pennington. “‘Why are They Commenting on His Page?’: Using Facebook Profile Pages to Continue Connections with the Deceased.” Computers in Human Behavior 62 (2016): 635–643. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.04.027.

- Breckner, Roswitha. “Zwischen Leben und Bild: Zum biografischen Umgang mit Fotografien.” In Fotografie und Gesellschaft: Phänomenologische und wissenssoziologische Perspektiven, edited by Thomas S. Eberle, 229–239. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2017.

- Brubaker, Jed R. “Death, Identity, and the Social Network.” PhD diss., University of California, 2015.

- Brubaker, Jed R., Gillian R. Hayes, and Paul Dourish. “Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning.” The Information Society 29, no. 3 (2013): 152–163. doi:10.1080/01972243.2013.777300.

- Brubaker, Jed R., Gillian R. Hayes, and Melissa Mazmanian. “Orienting to Networked Grief.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3, no. CSCW (2019): 1–19. doi:10.1145/3359129.

- Carroll, Brian, and Katie Landry. “Logging on and Letting Out: Using Online Social Networks to Grieve and to Mourn.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30, no. 5 (2010): 341–349. doi:10.1177/0270467610380006.

- Carroll, Evan, and John Romano. Your Digital Afterlife: When Facebook, Flickr and Twitter are Your Estate, What’s Your Legacy? Berkeley, CA: New Riders, 2011.

- Champion, Charlotte. “Instagram: je-suis-là?” Philosophy of Photography 3, no. 1 (2012): 83–88. doi:10.1386/pop.3.1.83_7.

- Charmaz, Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory: Methods for the 21st Century. London: SAGE, 2006.

- Cupit, Illene N. “Research in Thanatechnology.” In Dying, Death, and Grief in an Online Universe: For Counselors and Educators, edited by Carla Sofka, Illene N. Cupit, and Kathleen R. Gilbert, 198–214. New York: Springer, 2012.

- Dey, Ian. Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry. Bingley: Emerald, 1999.

- Eberle, Thomas S., ed. Fotografie und Gesellschaft: Phänomenologische und wissenssoziologische Perspektiven. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2017.

- Finlay, Christopher J., and Guenther Krueger. “A Space for Mothers: Grief as Identity Construction on Memorial Websites Created by SIDS Parents.” Omega 63, no. 1 (2011): 21–44. doi:10.2190/OM.63.1.b.

- Fordyce, Robbie, Bjorn Nansen, Michael Arnold, Tamara Kohn, and Martin Gibbs. “Automating Digital Afterlives.” In Disentangling: The Geographies of Digital Disconnection, edited by Andrâe Jansson and Paul C. Adams, 115–136. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Funk, Stephanie. Das Erbe im Netz: Rechtslage und Praxis des digitalen Nachlasses. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017.

- Gebert, Katrin. Carina unvergessen: Erinnerungskultur im Internetzeitalter. Marburg: Tectum, 2009.

- Gibson, Margaret. “YouTube and Bereavement Vlogging: Emotional Exchange Between Strangers.” Journal of Sociology 52, no. 4 (2016): 631–645. doi:10.1177/1440783315573613.

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York: Aldine, 1967.

- Harbinja, Edina. “Post-Mortem Privacy 2.0: Theory, Law, and Technology.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 31, no. 1 (2017): 26–42. doi:10.1080/13600869.2017.1275116.

- Harper, Douglas. “Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation.” Visual Studies 17, no. 1 (2002): 13–26. doi:10.1080/14725860220137345.

- Hemphill, Libby. “Dying, Death, and Mortality: Towards Thanatosensitivity in HCI.” In CHI EA ‘09: CHI ‘09 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, edited by Dan R. Olsen, 2459–2468. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 2009. doi:10.1145/1520340.1520349

- Hjorth, Larissa, and Kathleen M. Cumskey. “Selfie Eulogies: The Posthumous Affect of the Camera Phone.” In Residues of Death: Disposal Refigured, edited by Tamara Kohn, Martin Gibbs, Bjorn Nansen, and Luke van Ryn, 184–194. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

- Irwin, Melissa D. “Mourning 2.0: Continuing Bonds Between the Living and the Dead on Facebook—Continuing Bonds in Cyberspace.” In Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice, edited by Dennis Klass and Edith M. Steffen, 317–329. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Jacobsen, Michael H., ed. Postmortal Society: Towards a Sociology of Immortality. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Jacobsen, Ben, and David Beer. Social Media and the Automatic Production of Memory: Classification, Ranking and the Sorting of the Past. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2021.

- Jansson, Andrâe, and Paul C. Adams, eds. Disentangling: The Geographies of Digital Disconnection. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Jordan, John R., “Grief After Suicide: The Evolution of Suicide Postvention.” In Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices, edited by Judith M. Stillion and Thomas Attig, 349-356. New York, NY: Springer, 2015.

- Kasket, Elaine. “Continuing Bonds in the Age of Social Networking: Facebook as a Modern-Day Medium.” Bereavement Care 31, no. 2 (2012): 62–69. doi:10.1080/02682621.2012.710493.

- Kasket, Elaine. “Facilitation and Disruption of Continuing Bonds in a Digital Society.” In Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice, edited by Dennis Klass and Edith M. Steffen, 330–340. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Kasket, Elaine. All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age. London: Robinson, 2019.

- Klass, Dennis, Phyllis R. Silverman, and Steven L. Nickman. Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis, 1996.

- Klass, Dennis, and Edith M. Steffen, eds. Continuing Bonds in Bereavement: New Directions for Research and Practice. New York: Routledge, 2018.

- Kohn, Tamara, Martin Gibbs, Bjorn Nansen, and Luke van Ryn, eds. Residues of Death: Disposal Refigured. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

- Leaver, Tama. “Posthumous Performance and Digital Resurrection: From Science Fiction to Start- Ups.” In Residues of Death: Disposal Refigured, edited by Tamara Kohn, Martin Gibbs, Bjorn Nansen, and Luke van Ryn. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2019.

- Lynn, Cendra, and Antje Rath. “GriefNet: Creating and Maintaining an Internet Bereavement Community.” In Dying, Death, and Grief in an Online Universe: For Counselors and Educators, edited by Carla Sofka, Illene N. Cupit, and Kathleen R. Gilbert, 87–102. New York: Springer, 2012.

- Mason, Jennifer. Qualitative Researching. London: SAGE, 2009.

- McIlwain, Charlton D. When Death Goes Pop: Death, Media & The Remaking of Community. New York: Lang, 2005.

- Meese, James, Bjorn Nansen, Tamara Kohn, Michael Arnold, and Martin Gibbs. “Posthumous Personhood and the Affordances of Digital Media.” Mortality 20, no. 4 (2015): 408–420. doi:10.1080/13576275.2015.1083724.

- Moore, Niamh. “The Politics and Ethics of Naming: Questioning Anonymisation in (Archival) Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 15, no. 4 (2012): 331–340. doi:10.1080/13645579.2012.688330.

- Moore, Jensen, Sara Magee, Ellada Gamreklidze, and Jennifer Kowalewski. “Social Media Mourning: Using Grounded Theory to Explore How People Grieve on Social Networking Sites.” Omega 79, no. 3 (2019): 231–259. doi:10.1177/0030222817709691.

- Morse, Tal, and Michael Birnhack. “The Posthumous Privacy Paradox: Privacy Preferences and Behavior Regarding Digital Remains.” New Media & Society 24, no. 6 (2022): 1343–1362. doi:10.1177/1461444820974955.

- Moyer, Lisa M., and Suzanne Enck. “Is My Grief Too Public for You? The Digitalization of Grief on Facebook™.” Death Studies 44, no. 2 (2020): 89–97. doi:10.1080/07481187.2018.1522388.

- Reichertz, Jo. Qualitative und interpretative Sozialforschung: Eine Einladung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2016.

- Riesewieck, Moritz, and Hans Block. Die digitale Seele: Unsterblich werden im Zeitalter Künstlicher Intelligenz. München: Goldmann, 2020.

- Roberts, Pamela. “The Living and the Dead: Community in the Virtual Cemetery.” OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 49, no. 1 (2004): 57–76. doi:10.2190/D41T-YFNN-109K-WR4C.

- Rycroft, Gary F. “Legal Issues in Digital Afterlife.” In Digital Afterlife: Death Matters in a Digital Age, edited by Maggi Savin-Baden and Victoria Mason-Robbie, 127–142. Boca Raton: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

- Savin-Baden, Maggi. AI for Death and Dying. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and David Burden. “Digital Immortality and Virtual Humans.” Postdigital Science and Education 1, no. 1 (2019): 87–103. doi:10.1007/s42438-018-0007-6.

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and Victoria Mason-Robbie, eds. Digital Afterlife: Death Matters in a Digital Age. Boca Raton: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

- Shuber, Charlotte, and Adrian Kok. “Hospice Photography’s Effects on Patients, Families, and Social Work Practice.” Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care 16, no. 1 (2020): 19–41. doi:10.1080/15524256.2019.1703876.

- Sieberg, Daniel, and Rikard Steiber. Digital Legacy: Taking Control of Your Online Afterlife. New York: Stonesong Digital, LLC, 2020.

- Sofka, Carla J. “Social Support ‘Internetworks,’ Caskets for Sale, and More: Thanatology and the Information Superhighway.” Death Studies 21, no. 6 (1997): 553–574. doi:10.1080/074811897201778.

- Sofka, Carla, Illene N. Cupit, and Kathleen R. Gilbert, eds. Dying, Death, and Grief in an Online Universe: For Counselors and Educators. New York: Springer, 2012.

- Sofka, Carla J., Allison Gibson, and Danielle R. Silberman. “Digital Immortality or Digital Death? Contemplating Digital End-of-Life Planning.” In Postmortal Society: Towards a Sociology of Immortality, edited by Michael H. Jacobsen, 173–196. London: Routledge, 2017.

- Stein, Catherine H., Jessica Hartl Majcher, Maren W. Froemming, Sarah C. Greenberg, Matthew F. Benoit, Sabrina M. Gonzales, Catherine E. Petrowski, Gina M. Mattei, and Erin B. Dulek. “Community Psychology, Digital Technology, and Loss: Remembrance Activities of Young Adults Who Have Experienced the Death of a Close Friend.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 20, no. 1–2 (2019): 1–16.

- Stillion, Judith M., and Thomas Attig, eds. Death, Dying, and Bereavement: Contemporary Perspectives, Institutions, and Practices. New York, NY: Springer, 2015.

- van Dijck, José. “Digital Photography: Communication, Identity, Memory: Communication, Identity, Memory.” Visual Communication 7, no. 1 (2008): 57–76. doi:10.1177/1470357207084865.

- Villi, Mikko. “Visual Chitchat: The Use of Camera Phones in Visual Interpersonal Communication.” Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture 3, no. 1 (2012): 39–54. doi:10.1386/iscc.3.1.39_1.

- Vries, Brian D., and Judy Rutherford. “Memorializing Loved Ones on the World Wide Web.” Omega 49, no. 1 (2004): 5–26. doi:10.2190/DR46-RU57-UY6P-NEWM.

- Walter, Tony. “A New Model of Grief: Bereavement and Biography.” Mortality 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–25. doi:10.1080/713685822.

- Walter, Tony. “Communication Media and the Dead: From the Stone Age to Facebook.” Mortality 20, no. 3 (2015): 215–232. doi:10.1080/13576275.2014.993598.

- Walter, Tony, Rachid Hourizi, Wendy Moncur, and Stacey Pitsillides. “Does the Internet Change How We Die and Mourn? Overview and Analysis.” Omega 64, no. 4 (2011–2012): 275–302. doi:10.2190/OM.64.4.a.

- Weiser, Judy. Phototherapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

- Weiser, Judy. “PhotoTherapy Techniques in Counselling and Therapy—Using Ordinary Snapshots and Photo-Interactions to Help Clients Heal Their Lives.” Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal 17, no. 2 (2004): 23–53. doi:10.1080/08322473.2004.11432263.

- Willis, Erin, and Patrick Ferrucci. “Mourning and Grief on Facebook: An Examination of Motivations for Interacting with the Deceased.” Omega 76, no. 2 (2017): 122–140. doi:10.1177/0030222816688284.