ABSTRACT

This article studies an experimental pattern-cutting workshop part of a series of extension courses offered by a Brazilian University. It addresses ways in which to develop student-centred approaches to learning, highlighting the situatedness of the practitioner. In the workshop, the participants were invited to explore personal experiences as informants to their creative pattern-cutting process. The design outcomes show that experimental exercises are open to new successful encounters but also to failure, chance and disruptions. The activity is described and investigated from a participant observation viewpoint in terms of what an experimental approach to learning pattern-cutting may offer fashion design education. The results contribute to understand the roles of expectations in pattern-cutting activities, and challenges the teacher-orientation paradigm in fashion. Through these findings, the study adds to previous academic endeavours in creative pattern-cutting and fashion design education. The article concludes with a discussion on future directions for both education and practice.

Introduction

In the context of fashion design education, ‘pattern-cutting’Footnote1 implies the ways in which fabric is cut to be assembled as a garment. This particular stage is widely discussed in academic environments (e.g. Almond, Citation2010; Lindqvist, Citation2015; Rissanen, Citation2013) as it involves a number of aspects of fashion design, such as sustainability, wearability and sizing. One of the most widely used methods for introducing pattern-cutting to fashion design students is flat patterns, using scales or the direct measure system (Almond, Citation2010; Bye, Labat, & Delong, Citation2006). This broadly propagated method creates flat shapes on paper that are altered and adapted to fit the human body when transferred from paper to cloth and sewn together. For those outside – and often also within – the field of fashion, visualising the garment in its three-dimensionality in this method is difficult. Other methods offer different approaches to pattern-cutting, such as draping and tailoring. The draping method uses the body as a support for design, whereas in tailoring, the pattern’s lines are drawn in chalk directly onto the cloth (Almond, Citation2010; Almond & Power, Citation2018). Methods can be combined, increasing the complexity of the process and often yielding fruitful results (Almond, Citation2010). From the previous experience of the two authors of this paper as pattern-cutting practitioners for over ten years, learning the methods takes time and a great deal of ‘learning by doing’ (Dewey, Citation1934), which involves both failures and successes.

The work of a pattern maker thus involves managing different ‘languages’ and approaches, through an often laborious path, towards a final garment. Regardless of the method chosen, an aspiring designer must undergo multiple trials and errors in order to begin to understand the best way to achieve the desired results. Traditionally, fashion education introduces pattern-cutting to students by starting from the flat pattern construction and following strict rules, through a goal-oriented approach to teaching and learning (Bye et al., Citation2006). In this way, the process of developing a pattern becomes less relevant and the key point is achieving a precise outcome that conforms to the rules of the method, reflecting the traditional approaches in fashion design education (McRobbie, Citation2003).

The research questions this study seeks to answer are: how does a student-centred approach influence the learning process in creative pattern-cutting; and what can experimental pattern-cutting offer fashion design education? The workshop discussed here introduced alternative perspectives to fashion education by proposing a student-centred approach (Biggs, Citation1999). In the workshop, the participants were invited to explore subjective aspects from their personal experiences as informants for creating patterns in an experimental pattern-cutting process that required no previous pattern-cutting skills. This was an opportunity for each of them to develop their own creative method and try a mode of designing in which experimentation overtakes pre-conceived rules, allowing a student-centred learning experience.

Learning through experimentation

The importance of learning in education is heavily discussed in pedagogical studies (Biggs & Tang, Citation2007; Fry, Ketteridge, & Marshall, Citation2008). Educators are supposed to teach, but students may not learn the contents taught (Fry, Ketteridge and Marshall, 2009). Thus, a student-centred approach that focuses on learning is stressed, with an aim to facilitate learning outcomes. This approach advocates ways that create a good learning environment while aligning the teaching contents into varying elements of the course, including teaching methods, assessment methods, feedback methods for teacher(s), and other curriculum levels from programme to department (Biggs, Citation1999).

Within the context investigated in this study, two main factors hamper the development of such an approach to learning. The first concerns the tradition of fashion design education that often promotes hierarchical and teacher-centred approaches (McRobbie, Citation2003). The second refers more specifically to education in Brazil. Concerned with increasing the intake of students, many universities in the country approach education from a standardised perspective, leaving less room to cater to individual needs (Nosella, Citation2010). This leads to programmes that treat pattern-cutting as a rigid field of knowledge, avoiding experimentation, and rejecting a student-centred approach.

Exposure to theory and methods are important in the construction of knowledge, but this should not be understood as the only path. In supporting a pragmatist perspective (Dewey, Citation1934), Biggs and Tang (Citation2007, pp. 16–33) note that to achieve students’ deep learning, teachers need to consider a number of factors, namely the intention to engage in the task meaningfully and appropriately, appropriate background knowledge, a well-structured knowledge base, the ability to focus at a high conceptual level, and a genuine preference for working conceptually rather than with unrelated detail (pp. 26–27). They account for the fact that each person has the ability to articulate, synthesise, and act on the basis of their own logic. Galvão (Citation1999) in turn highlights learning and creativity suppression in traditional education and suggests active experimentation and self-awareness to overcome this matter. Other aspects inhibit learning throughout our lives, such as the constant expectation of success, and divergent behaviours that are seen as abnormal and drive the pursuit of conformity (Galvão, Citation1999). The workshop discussed here addresses the emergence of these issues by proposing experimentalism as a tool to regain comfort in creative learning.

Ideas can materialise and be expressed through a broad range of possibilities, but as suggested by Galvão (Citation1999), some transformation is necessary for creative potential to be developed, in terms of the behaviour of students and teachers. Judgmental and hierarchical behaviours that cause insecurity based on internalised concepts, without individual questioning, should be avoided because they harbour marginalisation and shame of exposing one's own ideas (Freire, Citation1987). The overvaluation of memory, which encourages achieving the ‘right answers’, can also impact on the detriment of discovery, as well as create punishments for non-learning and incorrect responses (Feyerabend, Citation1989). Further exploration of methods is thus needed to encourage action that brings forth experimentation and tests previously unexplored grounds, supporting the development of the field of the practice and its industry. In order to advance knowledge in professional practices, it is also necessary that students feel at ease and encouraged to face novelty in technology and design processes (Almond & Power, Citation2018). We next map out the literature on pattern-cutting, ranging from industry to academia.

From industrial practice to academic discussion

As a prominent field of research within the broad spectrum of fashion design practice, pattern-cutting has received a consistent amount of professional and, more recently, also academic contributions. Professional publications, which range from educational method books (e.g. Aldrich, Citation2008; Silva, Teixeira, & Franco, Citation[1934] 2017) to do-it-yourself magazines (e.g. Burda; La Maison Victor), have been available for about a century and are familiar to most households and independent craftistas. In the last 35 years, academic discussions and contributions have both consolidated pattern-cutting as a field of knowledge and raised discussions on the ways in which professionals make, understand and develop pattern-cutting. Foundational works, especially combining technology and pattern-cutting (e.g. Efrat, Citation1982; Lythe, Citation1981) have laid the grounds for the emergence of more recent movements that investigate the discipline, such as that of creative pattern-cutting, which is the interest of this study. Other professional efforts, such as the work of Tomoko Nakamichi in her series of books ‘Pattern Magic’ (Citation2010), have shifted the perceptions of pattern-cutting from a strictly technical field to one of creative expression.

Creative pattern-cutting can be defined as alternative modes of making patterns for clothing that hold creative expressions at their core (Almond, Citation2010). They can be achieved by a combination of different methods or by the creation of a novel/alternative method. Differing in process and outcomes from mainstream pattern-cutting methods, creative pattern-cutting envisions reaching new approaches through experimentalism. We locate experimental pattern-cutting under this umbrella of methods. A series of designer-researchers in fashion practice have actively contributed to the development of pattern-cutting as acknowledged research (Almond & Power, Citation2018; Lindqvist, Citation2015; Rissanen, Citation2013; Simões, Citation2012).

Timo Rissanen and Holly McQuillan propose the ‘zero waste’ model for pattern-making (Mcquillan & Rissanen, Citation2011; Rissanen, Citation2013), an approach that seeks to eliminate textile waste in garment production. Through his work, the model – previously practised by creatives in the industry without specific nomenclature (e.g. Teng, Citation2003) –, gained recognition and adoption throughout the world (Townsend & Mills, Citation2013). Zero waste pattern-cutting raises discussion on the often-ignored amount of fabric waste produced during the manufacturing of garments in the fashion industry.

Focusing on the fact that dressed humans move, Inês Simões (Citation2012, Citation2013) suggests the creation of block patterns that better embody this moving essence, targeting the representation of the body as a ‘mobile entity’ (Simões, Citation2013). Expanding on this, Lindqvist (Citation2015) proposes an alternative to the well-established method of measuring the human body via the tailoring matrix (or the measurement of the human body by parallel and vertical lines). His investigation drew from the work of fashion designer Geneviève Sevin-Doering, involving a draping proposal centred on the moving body. From a series of tests approaching the moving body, Lindqvist (Citation2015) created a new, kinetic matrix, in which movement plays an important role.

The works mentioned above are only a small sample of the growing field of academic research in pattern-cutting (cf. Valle-Noronha, Citation2019, pp. 41–43). Along with developing and theorising their pattern-cutting methods, many of the researchers above have shared their investigations and methods with students through courses and workshops. Sharing these initiatives aimed to test the methods and gain further understanding of their potential within education. Some examples are the works of Lindqvist (Citation2015) and Rissanen (Citation2013), who covered such explorations in their doctoral dissertations. The workshop in this study adds to these previous efforts of applying a more experimental take to pattern-cutting as a field of practice and education.

Experiment: the workshop

As part of a series of extension courses offered at Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG) the workshop was offered by the first author to a broad audience, not exclusively to those enrolled at the University. The institution posted a call for participants both digitally and via posters on academic sites. The workshop consisted of twelve contact teaching hours and about ten individual working hours. The workload was divided over three consecutive Saturdays between August and September in 2017. The table below presents a general overview of the contents of the workshop ().

Table 1. Workshop outline.

A total of nine participants took part in the workshop and agreed to participate in this study via a consent form. The majority had between little and extensive previous experience in pattern-cutting or clothing/fashion in a more general sense. Most of the participants were bachelor’s students and their average age was 28. The fact that many of the participants were students in different areas of design is a reflection of the lack of openness to other areas offered by mainstream pattern-cutting. The participants’ demographics are shown below, and names have been anonymized, as they are not relevant to the study ().

Table 2. Participants’ Demographics.

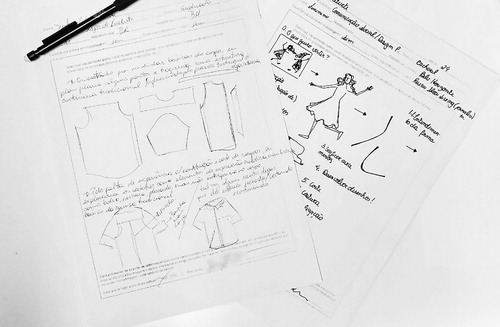

The workshop began by asking what is pattern-cutting and invited the participants to visually demonstrate how they understood or would make a pattern for cutting a shirt, including all the internal and external factors that could affect this. The aim of this activity was to acknowledge the different processes of making clothes that already existed as well as the potential of new emerging processes, supported by examples from a series of fashion designers. The participants filled in a form with this information, which was kept for reassessment at the end of the workshop. They complemented the examples by demonstrating individual interpretations of pattern-cutting (some examples below) and finished the section by discussing ‘are all pattern-cutting processes creative?’ ().

Figure 1. Participants’ representation of creating a pattern for cutting a shirt, some examples. Image: the authors.

Next, a series of examples of creative pattern-cutting was presented (Lindqvist, Citation2015; Rissanen, Citation2013; Valle-Noronha, Citation2015, Citation2016) and discussed based on the literature (Almond, Citation2010). Through this, the students became familiar with different approaches that question the mainstream processes in pattern-cutting and fashion design education. In the next stage, the students were invited to learn about how artefacts can be generated from concepts or even ‘instructables’ through the work of conceptual artists, such as Sol LeWitt (Baume, Freedman, & Flatley, Citation2011), and experimental pattern-cutting (Valle-Noronha, Citation2017).

Drawing from these examples, the participants were encouraged to create ‘instructions’ that would focus on generating patterns for producing garments and having them tested through peer review activity. In this way, the participants could exercise creativity and learning about pattern-cutting through both individual and collaborative work. After this exercise, the students continued developing their instructions and produced a final piece based on the created method.

The last encounter aimed to showcase all the processes and their outcomes together with a discussion on the possibilities these methods may open up to the designer. The participants shared their feelings and conclusions about working with pattern-cutting via this alternative approach and compared them with previous experiences, based on their first activity of visually describing the patterns for cutting a shirt.

Study methodology: collecting and interpreting data

This study worked with a mixed set of data, collected longitudinally during the period of the workshop. The dataset included diaries, notes, transcribed audio and photographs, and was interpreted through open coding and, at a second stage, through thematic coding (Flick, Citation2009, pp. 305–323). The themes applied to the second round of interpretation emerged from the data themselves and were chosen in resonance with the central interest of this study: to evaluate what an alternative approach to experimental pattern-cutting may offer fashion design education.

Findings

The findings of this study are presented in two layers. The first exposes what the students learned through the process, answering the first research question (how a student-centred approach influences the learning process). Second, and building from the learning outcomes, the study further identified two effects that illustrate the potential of employing experimental pattern-cutting in fashion design education.

What students learned: designed processes and disrupted results

The table below () exemplifies how the students developed as a result of their learning through some of the methods they created. It represents a plural approach to pattern-cutting, ranging from experiments related closely to usual pattern-cutting to deep experimental tentative attempts to create new shapes. Some of the projects focused more on the performative side of the practice, raising discussions on the roles of the body and clothes, as also noted by Ræbild (Citation2015). However, it was clear and unanimous that they all reflected the personal interests of each participant.

The final results in the images below () represent the plurality of personal interests and outcomes executed by the participants. One participant was absent in this last meeting, resulting in a total of eight displayed processes.

Topics emerging from the results

The results included swimwear, accessories, genderless garments, and surface design experimentations, making it clear that the disruptive aspect of the proposal also invited more open outcomes, which welcomed not only finalised garments.

A few topics emerged from the two-stage data interpretation and were classified as: valued personality, lack of expectations and accepted disruptions. These are described and exemplified with quotes from the data in the following paragraphs.

Valued personality

The first point of interest was that the experimental approach to pattern-cutting instigated very personal interests, not often so clear in other approaches such as metric pattern-cutting. Each of the students used very personal topics as informants for their methods. Some of these were: visual memories of a grandmother, personal bus rides and a narrative of the objects used during the morning (). This is seen as a very positive aspect, which promotes understanding and valuing individuals’ personalities. One student mentioned that this experience enabled reliving feelings similar to those when he developed his first piece:

[I]n all my [previous] experience in making accessories, the first bag I made I was very excited in the making process, I liked the result of it until today, and for all the following ones, the result was only declining [in quality]. […] And that's exactly what this workshop has brought, this excitement with pattern-cutting, this excitement of bonding with what you're doing. […] And it was quite nice in that sense, because I chose elements that I wanted to use, and I wanted to use them in the most unusual way possible. So, this whole process was quite challenging, and very enriching, in the sense of bringing me that pleasure of the first bag I made, which was a bag that I did experimentally.Footnote2 (Workshop day 3, from audio transcript).

Table 3. Description of dataset collected and used in the study.

Table 4. Description of topic and method choice.

Lack of expectations / accepted disruptions

The lack of expectations in the experimental method, suggested and promoted by the instructor throughout the workshop, led to pleasing encounters when a positive outcome or solution was achieved. It suggested ways of addressing expectations in pattern-cutting courses that lead to less frustration, enhancing students’ quality of engagement. The frequent lack of a clear visual target or the absence of sketches/croquis, an essential portion of mainstream processes in designing clothes, supported the creation of pieces outside the framings of fashion trends. In a similar way, while lacking predefined visuals or shapes, these processes encouraged non preconceived understanding of body(ies), allowing voices from a variety of bodies other than that of magazines or designers.

The participants were open overall to the disruptive method and freeing themselves from current fashion trends. Only one student mentioned the word ‘trend’ in regard to their work:

[…] that could adapt to any type of clothes and the inspiration comes from the oversized trend, the piece will be wide to give freedom of movement to the body. (Workshop, Day 2, from audio transcript).

Difficulties in approaching traditional pattern-cutting methods were also addressed by the participants. Two students clearly expressed their difficulties and expectations during their design studies:

I went through a quick introduction of one semester to traditional pattern-cutting. And I think I walked away just because I found the process hard. It scared me a little […] I felt like I didn’t have the space to explore beyond those rules, that the rules were a lot stronger than the actual process of doing and exploring … (Workshop day 1, audio transcript).

When I started studying fashion […] I realised that I did everything wrong! ‘I have to do it the right way’– I thought. But for me it was so difficult that I lost my previous learning […]. I used to work a lot with woven fabric and now I can’t anymore. I was really blocked. (Workshop day 3, audio transcript).

The stated difficulties reinforce the need for a more welcoming approach that avoids barriers, unlike traditional methods, and supports the proposal of experimental approaches as a first introduction to the pattern-cutting learning process.

Conclusion and discussion

From the discussions and the report of how the workshop developed in each participant’s learning process, two concepts emerged: frustration and disruption. While frustration acted as a negative drive behind the creative process, disruption sometimes also played the role of a positive as well as a negative input in the creative flow and openness to new learning.

What we noted, in comparison to previous experiences of teaching traditional block patterns, is that this experimental approach allowed a more facile method, and that previous experience in the field did not necessarily result in a more satisfying outcome. We observed that previous experiences could be applied or not to the new methods created, reinforcing the idea that a background in pattern-cutting was not necessary and did not affect productivity during the workshop. Instead, previous lived experiences in general became relevant in the construction of knowledge, holding the students’ needs and abilities at the core of the learning (cf. Biggs & Tang, Citation2007).

The challenging aspects found during the workshop concerned understanding the proposal. One of the students could not fully grasp the instructions and kept their sketches as the starting point of the process. This generated frustration when the expected outcome could not be achieved. This issue could be solved by emphasising that all outcomes are positive and clarifying the lack of judgement, especially in outcomes involving visual preferences. Another point of development perceived was that one additional meeting between the ‘instructions’ creation and the production of the pieces could increase the quality of the outcomes as well as help participants understand the lessons learned from their personal processes. This workshop thus helps us identify moments when frustration poses an impediment to the development of a creative process and to the creation of solutions to such problems. Moreover, the applicability of the method holds potential to expand beyond the field of fashion and reach out to other fields in design, such as product, graphic and surface design.

The limitations of this study in regard to the participants involved and its duration must be acknowledged. A limited number of nine participants, all originally from Minas Gerais, Brazil, took part in the workshop, which is a clear limitation in terms of study sampling. In addition, the short duration of the workshop must be considered. Further studies are thus necessary to validate our findings.

This experiment contributes to the academic field by presenting an alternative, student-centred approach to teaching methods for pattern-cutting. Based on this workshop experience, we can suggest the method as a first introduction to pattern-cutting for fashion design students. As a disruptive introduction, the method aims to challenge the broadly propagated paradigm in fashion studies that pattern-cutting demands arduous learning practice. Instead, it proposes pattern-cutting as a relatable and surprising practice, in which the practitioner’s mindset has plenty of room for creative and personal expression. The openness made possible by these aspects can inspire and expand the field of pattern-cutting. Some of the forms found in the experimental pieces could serve as the basis for the creation of other pieces, which allowed the participants to build their personal repertoires of processes and patterns, and create their own learning journey in the field.

The students developed their creative processes on the basis of personal experiences, which progressed from the ideation phase to sewing. These processes invited critical analysis and reflection beyond the construction of a designed piece. From the point of view of teaching, it is necessary for teachers to practice other forms of knowledge-building that encompass analysis and reflection together with students. In other words, it is valuable that students find their own means to navigate the process through constant questioning and problem-solving decisions instead of strictly following instructions with no room for experimentation. Other authors previously introduced here (Almond & Power, Citation2018; Lindqvist, Citation2015; Rissanen, Citation2013) have suggested new paths to enriching the learning of pattern-cutting in various ways. Thus we cannot indicate one of these methods as universal or comprehensive enough to serve all purposes. Education should follow its contexts in each case and increasingly incorporate the notion of collaboration and shared processes for a fruitful learning experience.

Acknowledgements

A draft version of this work has been published under the proceedings of the Colóquio de Moda 2018, named ‘Disrupted Expectations: The case of an experimental pattern cutting workshop’. The authors thank the Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais and all the participants of the workshop.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Note on terminology: In this article we use ‘pattern-cutting’ to refer to the field in a general sense, which includes traditional and alternative modes of making patterns for clothes. By creative pattern-cutting, as in Hollingworth, Citation1996 and Almond, Citation2010, we mean different methods in pattern-cutting that can, for instance, combine two traditional methods in a new approach. When we speak of experimental pattern-cutting we refer to methods that explore essentially giving form to three-dimensional wearable pieces via experimentation that does not necessarily lead to a finalised outcome.

2 Original transcripts in Portuguese. Translations can be provided upon request.

References

- Aldrich, W. (2008). Metric pattern-cutting. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing.

- Almond, K. (2010). Insufficient allure: The luxurious art and cost of creative pattern cutting. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 3(1), 15–24. doi: 10.1080/17543260903582474

- Almond, K., & Power, J. (2018). Breaking the Rules in Pattern cutting: An Interdisciplinary approach to Promote creativity in Pedagogy. Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education, 17(1), 33–50. doi: 10.1386/adch.17.1.33_1

- Baume, N., Freedman, S. K., & Flatley, J. (2011). Sol LeWitt: Structures, 1965–2006. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Biggs, J. (1999). What the student does: Teaching for enhanced learning. Higher Education Research & Development, 18(1), 57–75. doi: 10.1080/0729436990180105

- Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2007). Teaching for quality learning at university. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bye, R., Labat, K., & Delong, M. (2006). Analysis of body measurement systems for apparel in clothing and textiles. Research Journal, 24(2), 66–79.

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York, NY: Putnam.

- Efrat, S. (1982). The development of a method for generating patterns for garments that conform to the shape of the human body. Leicester: Leicester Polytechnic.

- Feyerabend, P. (1989). Contra o método. Tradução de Octanny S. Da Moda e Leonidas Hegenberg. Rio de Janeiro: Editora F. Alves.

- Flick, U. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Freire, P. (1987). Pedagogia do oprimido (17ª. ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

- Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., & Marshall, S. (2008). A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice. London: Routledge.

- Galvão, M. M. (1999). Criativamente (Vol. 2). Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark.

- Hollingworth, H. (1996). Creative pattern making (Unpublished MA dissertation). University of Central Lancashire, Lancashire, UK.

- Lima, J. G., & Italiano, I. C. (2016). O ensino do design de moda: O uso da moulage como ferramenta pedagógica. Educação e Pesquisa, 42(2), 477–490. doi: 10.1590/S1517-9702201606140330

- Lindqvist, R. (2015). Kinetic Garment Construction. Remarks on the foundations of pattern-cutting. Borås: University of Borås.

- Lythe, G. (1981, May). Computer aided design. Patterns that fit. CFI Conference.

- Mcquillan, H., & Rissanen, T. (2011). Yield: Making fashion without waste. New York, NY: The Textile Arts Center.

- McRobbie, A. (2003). British fashion design: Rag trade or image industry? London: Routledge.

- Nakamichi, T. (2010). Pattern magic. London: Laurence King.

- Nosella, P. (2010). A atual política para a educação no Brasil: A escola e a cultura do desempenho. Revista Faz Ciência, 12(16), 37.

- Ræbild, U. (2015). Uncovering fashion design method practice. The influence of body, time and Collection. Kolding: Designskolen Kolding.

- Rissanen, T. (2013). Zero-waste fashion design: A study at the intersection of cloth, fashion design and pattern-cutting. Sydney: University of Technology.

- Silva, C., Teixeira, D., & Franco, J. ([1934] 2017). Método de Corte Centesimal. Belo Horizonte: Corte Centesimal.

- Simões, I. d. S. A. (2012). Contributions for a new body representation paradigm in pattern design. Generation of basic patterns after the mobile body. I Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Faculdade de Arquitetura.

- Simões, I. d. S. A. (2013). Viewing the mobile body as the source of the design process. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 6(2), 72–81. doi: 10.1080/17543266.2013.793742

- Teng, Y. (2003). Yeohlee Teng. Victoria: AbeBooks.

- Townsend, K., & Mills, F. (2013). Mastering zero: How the pursuit of less waste leads to more creative pattern-cutting. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 6(2), 104–111. doi: 10.1080/17543266.2013.793746

- Valle-Noronha, J. (2015). Generator: Erro e Acaso como ferramentas criativas. Proceedings of the 5o ENPModa. Novo Hamburgo.

- Valle-Noronha, J. (2016). Dress (v.): Encorporeamento de movimentos através da modelagem criativa. Proceedings of the 12o Colóquio de Moda – 9a Edição Internacional. 3o Congresso Brasileiro de Iniciação Científica em Design e Moda.

- Valle-Noronha, J. (2017, March 22–24). On the agency of clothes: surprise as a tool towards stronger engagements. Proceedings of the 3rd Biennial Research Through Design Conference, Edinburgh, UK.

- Valle-Noronha, J. (2019). Becoming with Clothes: Activating wearer-worn engagements through design. Espoo: Aalto ARTS books.