ABSTRACT

Sustainability certification is one means to address environmental and social issues present in fashion supply chains, whilst bridging the knowledge gap between brands and consumers. However, despite increased urgency to improve social, ethical and environmental practices in this industry, little is understood about how ethical fashion brands currently utilise sustainability certification, in an increasingly saturated, and often unregulated, labelling environment. This study examines choice of sustainability certifications, certification process, and use of labelling, by a range of Australasian fashion brands who promote sustainability as a core part of their customer-facing image. The research identifies a five-stage framework for sustainability certification, as well as indicating failures of current systems relative to user needs. The study develops and offers a proposal for a standardised taxonomy of fashion sustainability labelling that could be adapted, irrespective of firm size, sales revenue of garment and textile types.

1. Introduction

The global fashion industry is energy-consuming, polluting and wasteful (McKinsey and Company, Citation2020). It is estimated that at least $400 Billion of clothing is disposed of every year (Reichart & Drew, Citation2019) and two-thirds of this waste are materials that take decades to decay (Shirvanimoghaddam, Motamed, Ramakrishna, & Naebe, Citation2020). In addition, the majority of fashion garment workers are underpaid and working in poor conditions (Sustain Your Style, Citation2020). The need for intervention in this industry is thus clear, however solutions that effectively bridge the gap between consumer knowledge of ethical choices and readily available market options are still lacking (Brewer, Citation2019; Ritch, Citation2022). While sustainability labelling is one approach seen as holding potential in this space, most labelling is optional and there are indistinct boundaries between reputable, auditable labelling options and those that are little more than a form of greenwashing (Gonçalves & Silva, Citation2021). The number of certifications and labels used in the textile and apparel industry over the past decade has risen significantly (Wang, Xu, Lee, & Li, Citation2022), prompting a view that sustainable fashion certification may indeed be at a point of saturation (Bartholomew, Citation2020). However, the introduction of a singular form of mandated sustainability certification and labelling is seen as a real solution for many of the above issues (Lee, Bae, & Kim, Citation2020).

Attempts to develop a cross-category, singular label type, however, have met a number of challenges in their implementation and use (e.g. the Higg Index), and government mandated labelling of fashion products still follows behind steps observed in other consumer categories such as food, electronics and vehicles. Despite these issues, the use of a singular, comparable label, across fashion brands and categories, may just offer a pathway to actual sustainable resilience in the fashion industry, from the perspective of both fashion producers and consumers. In response to this, this study aimed to develop a taxonomy for fashion garment sustainability certification that could be adapted to different country-specific fashion industry contexts, whilst maintaining the central integrity of the framework. Such a taxonomy may then offer a solution that meets the needs of sustainability conscious fashion brands as well as their consumers. Hence, as the primary objective of this research was to develop such a taxonomy for potentially mandated garment sustainability labelling, the current study sought to (i) identify commonly used fashion certifications amongst fashion brands in Australasia; (ii) examine the perspectives of a range of fashion producers that represent different business types, size and commitment to circularity; and (iii) to detail fashion brands’ needs and expectations in regard to sustainability certification within their business. It is anticipated that the findings of this study will contribute to future discussions of mandated sustainability certification and labelling in Australasia and other markets.

2. Literature review

A focus on sustainability in fashion has emerged as a consequence of ever-increasing consumption of clothing globally, contrasting sharply with the rapid depletion of the natural resources that fashion production consumes, including people, water, clean air, soil, plants, and oil (Knošková & Garasová, Citation2019; Lawless & Medvedev, Citation2016). It is suggested that, for fashion brands to remain relevant in the foreseeable future they must integrate sustainable practice and business models into all of their products and supply chains (McKinsey & Company, Citation2021). Sustainable first movers and sustainable fashion entrepreneurs (those that are ‘born sustainable’, designing business models with sustainability at the core) are said to be leading the charge both in the implementation of sustainable practice, but in gaining the attention of increasingly aware fashion consumers (Todeschini, Cortimiglia, Callegaro-de-Menezes, & Ghezzi, Citation2017; Zhang & Song, Citation2020).

Sustainable consumption is generally said to be driven by the intrinsic motivations of the individual, related to their desire to protect, or lessen damage to, the environment (Schwartz, Loewenstein, & Agüero-Gaete, Citation2020). There is, therefore, a growing motivation for suppliers to inform their customers of the extent of their organisational sustainability principles, driven by customer demand for transparent information regarding those same principles (Chen, Zhao, Lewis, & Squire, Citation2016). Where organisations who emphasise sustainability principles in their business strive to communicate this to their customers, there is a need for clear and easy to interpret communication tools, such as uniform sustainability labelling (Bach, Lehmann, Görmer, & Finkbeiner, Citation2018). However, the current use of sustainability cues on consumer goods often assumes that planned behaviour and (reasoned) action are applicable to the fashion context, by applying fragmented and increasingly complex cognitive decision cues to what may indeed be a form of low-involvement decision-making. This disconnect, between the current labelling state and what might be required for more impactful application of sustainability information to fashion products, therefore underscores a need for research that examines how brands might better inform their customers of the relative impact of their goods, both within and across product categories (Sailer, Wilfing, & Straus, Citation2022).

2.1. Sustainability certification in fashion

Sustainability labelling falls into the category of external cues that a brand may use to demonstrate unobservable product attributes or practices (Lee, Bae, & Kim Citation2020), aiding in alleviating consumer knowledge gaps (Kim & Kim, Citation2011), while helping to drive purchasing decisions at the point of sale or decision-making. Sustainability labelling, thus, is a form of ‘nudge’ – an element of choice architecture designed explicitly to prompt predictable consumer behaviour (Anderson, Citation2008). Nudge strategies are not new. In the food and automobile industries such ‘nudges’ have been used for decades to stimulate or reduce choices, however, the application of nudge strategies in relation to fashion sustainability has been questioned regarding its actual effectiveness on consumer choice (Roozen, Raedts, & Meijburg, Citation2021). One method to ensure the effectiveness of ‘nudges’ regarding sustainability labelling is to use recognisable certifications of sustainability information, to stimulate consumer trust, alongside environmental concern, where trust is known to significantly and positively influence purchase intention in consumer environments (Chun, Joung, Lim, & Ko, Citation2021). There is strong evidence that consumers value transparency in terms of product origins, production and environmental impacts, yet consumers lack the requisite knowledge of the apparel industry to judge these factors without clear (and trustworthy) communication by brands (Byrd & Su, Citation2021).

Certification is therefore a useful process in communicating sustainability, whereby a credible third party provides objective evidence that demonstrates the capabilities of a trading partner (Cook & Luo, Citation2003; Lee, Bae, & Kim, Citation2020). Legitimate sustainability certification and labelling can result in an abundance of benefits to companies, customers, and supply chains. However, illegitimate, or manipulative labelling, in the form of ‘greenwashing’, is at its worst described as the intentional misleading of the consumer (Lyon & Montgomery, Citation2015). The introduction of sustainability certifications to the fashion arena was proposed to increase manufacturer-consumer transparency and put a stop to false claims about the ethics of brands and products (Brydges, Henninger, & Hanlon, Citation2022). However, communication of sustainability in the fashion market has been blurred by fast fashion retailers who have used the concept as a marketing strategy, designed to promote increased purchasing by consumers – evidenced in the widespread use of brand-owned pseudo-sustainability labelling (which often has little-to-no appreciable sustainability measure) (Binet et al., Citation2019).

Certifications can be identified as a logo, symbol, or mark (Lee, Bae, & Kim, Citation2020). In the fashion industry, consumers recognise sustainability certification displayed on a garment or garment tag as a signal of the relative ethics of that product (Bennett, Citation2017). Consumers have expressed a desire for more sustainable options, however, have often exhibited limited knowledge regarding social and environmental practice within the fashion industry specifically (Byrd & Su, Citation2021). However, current sustainability communications by fashion brands utilise a plethora of different types of certifications, labels and systems of evaluation, which serves to confuse buyers as well as dilute the message delivery of all brands using such tools in market (Chun, Joung, Lim, & Ko, Citation2021). The lack of actionable information in fashion consumption is thus cited as one of the primary causes of the persistent attitude-behaviour gap in consumer apparel purchasing (Turunen & Halme, Citation2021).

2.1.1. Certification forms

Fashion is a complex consumer product. Fashion garments are often purchased for reasons that extend well beyond the practical or functional, and single garments often carry multiple (competing) informational cues (Rahman & Koszewska, Citation2020). Even when only garment sustainability cues are examined, approximately 455 individual eco-labels compete across 199 countries (2021 Ecolabel Index). Lee, Bae, and Kim (Citation2020) note that, despite this, little research has been done to examine garment sustainability cues, despite the interest and importance of sustainable labelling in fashion. Consumers are highly aware of the need to consider sustainability aspects of their consumption choices, yet actual sustainable behaviour does not match their level of expressed awareness (Turunen & Halme, Citation2021). In this sense, we are said to be operating in a critical transition period regarding sustainability and its impact on decision-making (Geiger & Keller, Citation2018), hence the urgency of calls for more empirical research that examines sustainability cue forms in the apparel industry (Rahman & Koszewska, Citation2020).

Loosely, sustainability labelling falls into seven categories: holistic, environmental, organic, animal, social, recycling, and others (Fashion United, Citation2021). Among these, the most used third-party certifications worldwide are Global Organic Textile Standards, SA8000 Social Accountability International, Worldwide Responsible Accredited Production, Fairtrade, and B Corp by B Lab (Bartholomew, Citation2020; Fashion United, Citation2021; Future Learn, Citation2019). However, brand-created pseudo certifications such as H&M’s ‘Conscious Collection’ are cited as growing in prominence in consumer knowledge of sustainability cues (Edie, Citation2021). Within the seven categories, labelling can take one of three main forms – a nominal cue, such as the H&M ‘Conscious Collection’ brand image, a binary cue, such as the Fairtrade mark (where presence or absence of the mark is a signal to the consumer) and ordinal/ratio cues, which communicate a specific score achieved by a product, in reference to pre-determined qualifiers (such as the Tearfund pie chart).

Further categorisation of sustainability labelling forms relates to the extend to which a label has high consumer reliability via a third-party assessment system, or is a free-form, brand-driven communication (Turunen & Halme, Citation2021). Within the apparel industry, certification is still optional and unregulated (Fashion United, Citation2021; The Sustainable Fashion Forum, Citation2022). While some have argued that these different forms of sustainability labelling are a must, given the complex nature of manufacturing and selling clothing (Diekel, Mikosch, Bach, & Finkbeiner, Citation2021), from a consumer perspective, there is little to distinguish between different, regulated third-party certifications and that of nominal, brand-created sustainability product cues (Urbański & Ul Haque, Citation2020). This is a significant problem for both the manufacturer and retailers of garments, as well as for the end consumer, suggesting a need for greater consideration of labelling standardisation. The lack of actionable information in consumer-facing sustainability labelling is thus cited as a primary cause of the current attitude-behaviour gap in fashion consumption (Turunen & Halme, Citation2021).

2.2. The argument for standardisation of sustainability certification

The rapid growth in volume of different certification requirements (and thus types) has been attributed to necessity, given the relative complexity of producing apparel compared with many other consumer products (Eco Cult, Citation2019). However, each certification, even within the same certification type category, has different acquisition requirements. This adds to an environment where consumers remain sceptical of all labelling, due to a lack in the skills required to process the various forms in a useable and comparable fashion (Mukendi, Davies, Glozer, & McDonagh, Citation2020). The current multitude of labels, and lack of comparability, serves little to address the central consumer problem of identification of ‘better’ or ‘worse’ options within the fashion industry (Gonçalves & Silva, Citation2021). Rather, the proliferation (and saturation) of different pathways to certification creates a proxy sustainability standard whereby the mere presence of a sustainability label acts as a prompt to purchase (and often at a higher price) (Roozen, Raedts, & Meijburg, Citation2021).

Further, the current system does not encourage producers and retailers towards better sustainability outcomes, as firms can identify a certification that is able to be quickly achieved with little to no change in firm practice – essentially instrumentalising and misappropriating sustainability cues for self-interest (Sailer, Wilfing, & Straus, Citation2022)). Despite this, there is strong evidence, in existing complex marketplaces, that a standardised, single label form could be developed to indicate a general sustainability score, which allows easier interpretation and comparison of goods, such as the ‘traffic light’ system seen on pre-packaged foods (Mukendi, Davies, Glozer, & McDonagh, Citation2020). A standardised approach has been implemented in categories such as food, health, energy use, vehicle safety, vehicle emissions, etc. (Consumer NZ, Citation2020; Ministry for Primary Industries, Citation2022; NZ Transport Agency, Citation2022). The use of single, primary labelling forms in these industries therefore suggests potential for a similar approach within fashion manufacturing and sale, giving sustainable firms a clear competitive advantage in the apparel market (Sailer, Wilfing, & Straus, Citation2022).

In designing a broad-spectrum labelling system, the importance of third-party certification is evident, as an independent system provides consumers convenience and certainty when selecting more sustainable clothing options (Ranasinghe & Jayasooriya, Citation2021) An independent certifier can assess and verify claims made by firms (Oelze, Gruchmann, & Brandenburg, Citation2020), providing a trustworthy reference point, even when a consumer is unfamiliar with a brand (Kim & Kim, Citation2011). This reference point may hold even more weight when it is a singular cue, that allows binary comparison of different garments by different producers, irrespective of their fabric, country of origin, parent brand, etc. However, one of the central issues in the implementation of a generalised fashion sustainability labelling system is that it runs counter to the argument for multiple labels, which notes the complexity of individual fashion garments and their production and sale components, thus requiring input-level certification for all components (Diekel, Mikosch, Bach, & Finkbeiner, Citation2021). These two arguments, when considered together, serve to underscore the critical gap that has impeded sustainability labelling in the fashion industry – that of the disparity in producer and consumer requirements for such labelling.

Launched in 2011 by the ‘Sustainable Apparel Coalition’ (including H&M, Nike, Levi’s, Walmart and Patagonia), the membership based Higg Index was designed to address some of the outstanding issues in fashion sustainability labelling, providing a common tool with which to measure the environmental and social impact of fashion products (Radhakrishnan, Citation2014). With uptake by more than 500 brands by 2021, the system has had a significant global impact on the sustainability labelling phenomenon in fashion, allowing shoppers to compare greenhouse gas emissions, fossil fuel and water use, pollution and other sustainability-related factors. The Higg Index thus allows shoppers a means to select garments using a measure of relative sustainability – solving the issue of a lack of a binary comparison point in fashion retail (Chun, Joung, Lim, & Ko, Citation2021). However, a recent examination of the Higg system highlighted areas of concern with the weighting of various factors used to calculate scores, with critics questioning aspects of the measure such as the ranking of synthetic materials, made from fossil fuels, as more environmentally friendly than natural fibres (The New York Times, Citation2022). While the Sustainable Apparel Coalition states that comparison of fibres (and thus garments) is not the aim of the Index (Razvi, Citation2022), others may argue that consumer misunderstanding of the Index may naturally lead to such comparison. What we can learn from the current discussion surrounding the Higg Index is that a certification system that can be applied across garment types, categories and producers is critically needed, however, one which allows binary comparison of fashion garments by consumers may be required to address the needs of both fashion producers and consumers (Roozen, Raedts, & Meijburg, Citation2021).

The review of literature has highlighted the inadequacies of the current options for sustainability labelling, both from a complexity of supply chain perspective, as well as from a consumer cue processing perspective, where the relative sustainability continuum of products is currently poorly communicated across a variety of incomparable labelling methods. This research aimed to examine the experiences of Australasian fashion firms using sustainability certification and labelling, identifying the needs of such firms in the communication of relative sustainability of end products to consumer interpretations of these cues. Literature suggests that there is demand for product sustainability cues that consumers can use to easily compare across product options in the fashion marketplace, in order to make well-informed decisions. This research aimed to propose a model to achieve this, whilst maintaining the channel sustainability integrity valued by many producers of fashion garments.

3. Methodology

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of the seven selected firms (), using an interview protocol derived from extant literature. Interviews were held using Zoom and recorded for later analysis. The interviews ranged between 45mns to an hour or more, and were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step framework for Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Further, the research process included the collation of material to perform an analysis of the sixteen sustainable fashion certifications used by participants, as listed in . Data was sourced directly from the certification provider, as collateral material provided to firms considering applying for such certification. Content analysis of the collateral material identified four key information points, those of: (i) certification type; (ii) incentives for certification; (iii) criteria for achieving certification; and (iv) the frequency of certification renewal and assessment. The research received ethical approval via the Department of Management, Category B process (approval number D22/130).

Table 1. Sample profile.

Table 2. Certifications by category.

In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of the seven selected firms (), using an interview protocol derived from extant literature. Interviews were held using Zoom and recorded for later analysis. The interviews ranged between 45 minutes to an hour or more, and were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-step framework for Reflexive Thematic Analysis. The research received ethical approval via the Department of Management, Category B process (approval number D22/130).

3.1. Research participants

Selection of a wide but representative range of participants for this study was crucial to achieving the stated research objectives. Hence, the target population at the firm level was a range of fashion manufacturers and retail brands that use sustainability labelling as a central part of their consumer-facing image but also represented diversity of size, sales region and channel, garment types and commitment to circularity. The sampling technique was thus non-probability and dictated by the criteria of the research question, with seven firms identified to represent the aforementioned range (refer ). Standard cotton T-shirts were selected as price comparison garments across the seven firms, to contextualise the sample differences.

Of the seven included firms, Firms A & B were high-street brands with high sales volume, with average T-shirt prices of $30NZD for Firm A and $40NZD for Firm B. Firm C began as a footwear brand, however, now also produces trend-based limited-edition T-shirts (average price $65NZD), socks and underwear. Firm D was a design-led brand with limited run, slow production offerings. A standard T-shirt from Firm D retails for $90NZD. Firm E produced high-quality cotton and merino knit basics for the whole family (average adult T-shirt $45NZD). Firm F began as an ethical cotton underwear producer, but now produces an expanded range including lounge, swim and activewear. A standard T-shirt retails for $99NZD. Firm G produced printed cotton garments for schools, workplaces, sports teams and similar, as well as some limited edition self-branded printed garments. They source base garments from a range of suppliers, including Firm A. An average T-shirt price (excluding bulk ordering discounts) is $40NZD. In terms of individual interview participants, those responsible for the sustainability certification process within firm were selected for interview. The sample selection process was necessarily purposive, to ensure accurate firm certification process information was collected. The range of sustainable certifications employed by participating firms are noted, by certification type, in .

Of the total pool of certifications used by the sample, only three certifications pertain to social sustainability and only two are considered holistic organisation certifications. Additionally, there is a lack of certification that monitors circularity at the design, sale, and end-of-life stages, despite three of the included firms citing this as a central value of their business.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. The certification process

shows the general process participants undertook when acquiring sustainability certification. However, participant experiences of the certification process and its stages differed greatly, depending on the certification they used and how ‘easy’ or ‘rigorous’ they perceived its standards. Further, there were differences cited in ease of certification corresponding to whether the process certified the supply chain of custody or the end product.

The first, and arguably most important step in obtaining sustainability certification, is a review of all available certifications the brand qualifies for, to decide best fit. Once a decision has been made, an agreement will be made with the certification organisation, culminating in the payment of fees, preparation and submission of firm-generated reports and independent audits (where used). Other, less common steps that accompanied some certifications included education in the form of workshops and training, as well as tracing products in the production and channel process from beginning to end (e.g. Firm A).

For most participants, the actual certification reporting process did not raise much comment or emphasis, with the exception of two firms, who noted that their experience of a particular certification stood out as significantly rigorous in comparison to other certification experiences:

the B Corp one, it was a pretty complex one, a very exhausting one. I think it took us probably about 26 h to actually do the recording and fill in the documentation that was required. For small businesses that’s a lot of time, and we didn't really think we needed it, because we didn't really do anything different, as the way we operated as a business (Firm C).

The living wage one is pretty basic, and easy to get. It’s more like a yes or no. The B Corp one is probably like the most in-depth one. Given that B Corp is a holistic certification that pride themselves on their credibility, I believe being rigorous is a must in their certification process (Firm E).

4.1.1. Choosing a certification

It was apparent in this study that some certifications are more desirable, and more commonly acquired, than others. For example, of the seven participating firms, six use the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) certification. Firms agreed that this certification was preferred due to market demand for the standard, noting ‘I think the GOTS one is becoming more and more consumer driven’ (Firm E). Firms in this study also commonly acquired multiple fibre standard certifications, as each is unique to a different textile (e.g. Firm B uses GRS for recycled fibre, GOTS and Fairtrade for cotton, RDS for down products and they are working towards 100% RWS for their wool products). Some expressed frustration at having to manage multiple certifications across their product range, others noted a lack of knowledge of how to approach fibre certification across these standards: ‘we knew we needed to do something at farm level (for sourcing fibres), but we just weren’t sure what’ (Firm A).

Textile certifications are assessed and held at the farm or factory level, rather than by the fashion brand. This is seen as positive for the brand, as

for us, there is no real work to get those certifications, because it is just a matter of us choosing them when we are sourcing the raw products. So easy for us on this side, all we need to do is cite the certifications that are linked to the production of the fabric (Firm D).

99.9% of the time the heavy audits go into traders who are working with the product. It's much easier for a brand than it is for the farmer’ (Firm B); ‘We have specifically done procurement through places that hold those certifications.’ (Firm E); ‘These are certifications from our suppliers, so all we had to do was partner with the right people (Firm F).

4.1.2. Certification ‘fit’

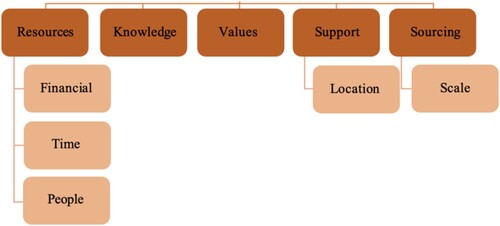

The best fit for a firm deciding which certification (if any) to use is determined by many factors specific to the firm. However, participants in this research all identified central considerations that can be conceptualised as a group of five antecedents to their certification decision-making process (), namely: resources; knowledge; values; support; and sourcing.

4.1.2.1 . Resources

Resources impacted by the certification process include finances, time and people. Participating firms all noted these three resource factors as influencing their decision to seek any form of certification (or to choose not to certify). These concerns were moderated by fee structure of the certification itself, where some certifications had a straightforward auditing fee and ongoing ‘maintenance’ payments that did not vary, whilst others required a more significant commitment in the form of revenue percentage. Where the cost of certification was a known factor, firms appeared less concerned with the financial investment required (e.g. ‘I wouldn't say that auditing cost was a deterrent’ (Firm B)). Where certification was linked to overall revenue however, firms found this a more complex decision (e.g.

That’s probably been a big deterrent of why we’re not Fairtrade certified ourselves because, basically, you have to pay an amount of your revenue to the Fairtrade certification body. And we just felt like we didn't have that available money, and we would rather invest directly as opposed to paying a third party for that (Firm E).

Of course as a small start-up business [money matters], but because we had strong values from the start it didn’t matter to us if there was a cheap nastier fabric [available], we were happy to pay more for the certified fabrics (Firm D).

Had I’d known how much time we had to put into the B Corp? I would have probably not gone ahead with it. We have now and so, we have just renewed our membership, and we had to provide updated information on that as well! (Firm C).

Certification, in most instances, puts pressure on firms to manage an extra workload of record-keeping and auditing. For smaller fashion firms, the impact on staff is significant, and decisions to undertake new or multiple certifications are often bounded by limited people resources: ‘I’m the only person that works in compliance and sustainability. How much can we sign up for if it's just me doing the work?’ (Firm A); ‘I think companies more and more are recognizing that they need an extra resource to manage reporting’ (Firm B). Even firms with greater personal resources find the certification process challenging to manage, noting the impact of staffing changes on the smooth running of the process:

I tend to give a lot of this work to my staff to work on because I don't have the time to be spent on this submission, or the reporting. If we turnover staff, we have to make sure that they're [new staff] going to be able to pick up the knowledge as they go along (Firm C).

4.1.2.2. Knowledge

As available certifications have multiplied in the fashion industry, so too has the complexity of information surrounding individual forms of certification. The attractiveness of new certifications in the market is limited by the extent to which firms firstly understand what is required for uptake, and secondly whether they have the motivation or resource (time, money and people) to learn a new process: ‘with any new certification or any new audit, it is a little bit of a catch-up game to understand exactly what is required in that standard’ (Firm B). When certification requirements are unclear or lack surface-level transparency, there is little incentive for firms to examine these processes further: ‘we have been in this field for 9 years now and I still find a lot of the certifications pretty unclear’ (Firm D); ‘quite a lot of information is over my head’ (Firm A). Secondary research confirmed this issue, as many certification body websites provided only limited, and often subjective, information regarding their rules for certification/ sustainable labelling.

4.1.2.3. Values

The need for alignment of brand and certification values was a strong theme among the comments made by participants in this study. Firms noted that their use of a sustainability certification was linked to expectations of comparable values between their own and that of the certification: ‘I guess we prioritize our values pretty highly in terms of people and planet so yeah, the certifications out there align with what we want to do, so no conflict in values there’ (Firm D). Participants of this study also signalled the importance of considering who the certifying body was, and what they genuinely represent regarding ethics and environment, with frustration shown towards some in-market options:

I feel there’s some like SEDEX that all the crappy corporates [use]. Stop pretending like this is helping. Same with Better Cotton Initiative [BCI]. I see it passed around everywhere, and literally, it is in the title, it is slightly better than your average cotton (Firm E).

4.1.2.4. Support

A clear incentive for firms in this study to undertake certification was the perceived level of support the certifying body could offer firms, both throughout the auditing process, and beyond certification:

I don’t have the resources to do my own kind of auditing, and you know, if you’re a larger corporation, they have whole teams of people who can keep an eye on their supply chains, and we don't, I mean I do visit our suppliers occasionally. But I'm not in a position to be able to make a definitive statement about our supply chain, and that's why I rely on third-party verification, especially Fairtrade certification (Firm C).

our factories are based in China and Bangladesh. We are really far away, so we do need some kind of aid in that area. It is definitely really integral for us to have some kind of transparency, of what’s going on in our factories (Firm A).

4.1.2.5. Sourcing

The firms who took part in this research have a mix of certifications, however all had certification at in-channel farm and factory levels. As noted earlier, there is a sense of ease in utilising these certifications, as while accredited raw inputs (such as textiles) may cost more, the resource efficiency of certification sitting with the external channel member often outweighs this. Some firms noted challenges associated with this, when balancing commercial realities and the demands of innovation – a common problem in fashion industries:

it does limit where we can buy from. For example, we are wanting to introduce this new product, but the factory we want to work with doesn’t have those specific certifications. So, either it means we have to be, in our [marketing] comm[unications], really clear that this isn’t GOTS certified, or we have to change all of our language to be like, ‘most of our factories, are GOTS certified’. So that’s like a big decision-making process (Firm E).

4.2. Towards an integrated system for certification

When discussing sustainability labelling and certification with fashion firms in this study, it became apparent that each firm would weigh a similar set of firm-specific benefits, or positive impacts of undertaking certification against a recognised set of industry negative impacts of the current labelling landscape. This is interesting, as firms did not perceive their own previously cited challenges of obtaining and continuing with certification as holistically negative, rather, firms’ discussions of aspects of disadvantage were related to the industry and its’ use of labelling as a whole (refer ).

Table 3. Benefits and detriments of certification.

Firms in this study felt that the benefits of being part of a certification ‘family’ jointly increased transparency and robustness of sustainability practice within the industry, whilst providing a clear network effect whereby individual efforts offered collective benefit for those using the same certifications: ‘the more people who use that standard, who buy certified product, the more the incentive grows for everybody in the supply chain to keep spending time and effort on that particular administration’ (Firm B). Further, participants noted the positive impact of certification comparison between brands, where firms were prompted to have the same or more sustainability certifications as others within their product category:

I think a lot of them (brands) wouldn't be doing it off their own bat of ‘we need to be better’. They won't get the sale if they don't have the [certification]. So, I think that's often what's driving it (Firm G).

However, the use of sustainability labelling across the industry, in its current, unregulated form, as well as the relative saturation of certifications available to fashion firms was cited as a major drawback of the current certification landscape. Participants pointed to the greenwashing techniques of fast fashion manufacturers who produce their own ‘sustainability’ labelling cues, but do not clearly communicate how or why their products should be considered as sustainable in comparison to those using third-party certification: ‘they (fast fashion) don’t care what they are making, but they do care what the customers think. I think certifications are a tool for [this] greenwashing’ (Firm D). The fashion firms in this study expressed frustration at the overall impact of this greenwashing and the increasing saturation of labels in the marketplace, with concern noted regarding consumer awareness and understanding of what labels actually indicate about a fashion product:

with B Corp [certification], we’ve had some people ask us why are we not A Corp certified? Because they think that B Corp is something lesser’ (Firm C); ‘there’s this general feeling (among consumers) that if it has any certification, that means it’s good. And so, I feel like people are either just totally confused, or they're just looking for a reason to justify their purchasing (Firm E).

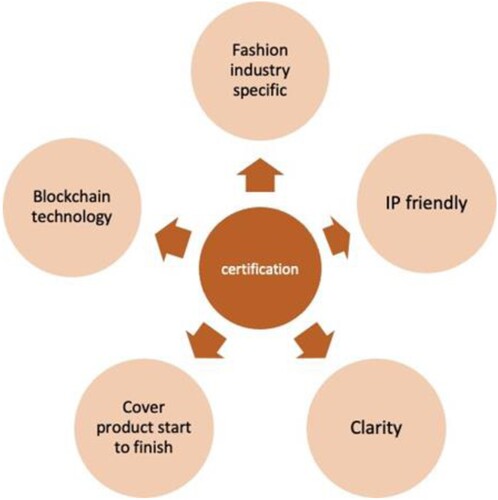

When participants were asked what an ‘ideal’ sustainability certification and labelling system would look like (refer ), there was immediate mention of the need for a system designed specifically for the fashion industry, noting that, in their view: ‘there is no one [certification], which is specifically set up for the fashion industry. I want to see one that covers only the fashion industry’ (Firm C). In addition, firms desired a certification that covered both social and environmental sustainability, whilst certifying the product the whole way through the supply chain, including end-of-life. Preference for a singular certification that covers all these aspects of fashion production and consumption was seen to combat the problem of multiple labels that cannot be compared in a relative fashion by consumers: ‘You're having to use lots of different [certifications] to get out the same information’ (Firm C).

Study participants often came back to the need for clarity in any sustainability labelling, in the way that information about products is communicated to consumers, as well as the way that a label might reliably allow between-product comparison across manufacturers and brands: ‘if we [can] give them an accreditation, which gives them confidence that we are the real deal, then it's worth doing it’ (Firm C). Achieving this clarity was noted as a benefit of a singular, industry-wide certification that was based on the full life cycle of the final product, however participants noted that this would mean ‘removing some of the unnecessary stuff’ (Firm A) and developing, within firms, a ‘clear understanding of where we’re at, and a clear understanding of where we’re going’ regarding sustainability objectives (Firm B). Avoiding the need for multiple certifications per garment was seen as a benefit in regard to making the process far more IP friendly for firms. Further, participants identified blockchain technology as a means to ensuring the system was not only reliable and trustworthy, but also as a means to reduce some of the existing auditing and monitoring burdens faced by smaller brands. However, as noted by one smaller participant: ‘[currently,] you need to be a brand of a certain scale to be able to employ that sort of technology’ (Firm B) ().

When the ‘ideal’ sustainability certification as described by participants in this study was compared to the exiting certifications used by the sample, no one single system met the demands of this group of firms. When discussing this, the issue of mandating labelling across the fashion industry in Australasia was raised, with some stating that the potential for this is ‘Excellent. We should have had that 20 years ago’ (Firm E), yet ‘If the government's going to be involved, they've got to do it properly and make it compulsory and introduce penalties’ (Firm C). However, positive views of mandating were tempered by the reality of being an often small, limited resource firm in the fashion marketplace: ‘I think you'd have to be careful to make sure that smaller brands don't get disproportionately disadvantaged from something like that. I think the big brands could easily achieve it’ (Firm B); ‘It could be a killer of small business or a killer of social enterprise if it was too difficult’ (Firm D).

5. Towards a standardised certification model taxonomy

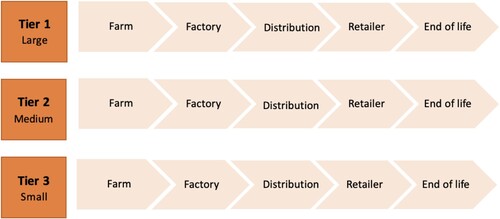

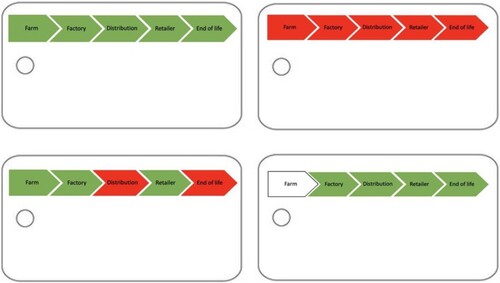

One of the primary objectives of this research has been to identify and develop a taxonomy that could be used to frame the needs of Australasian sustainable fashion brands, regarding a single, comparable sustainability certification and label. A three-tier system is envisioned (refer ), with each tier providing a measure of an appropriate standard of requirements, pro-rata to the size of the firm, its input use and output.

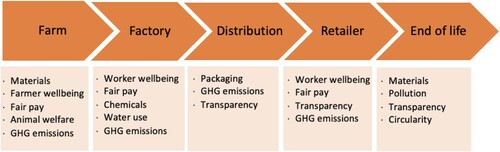

A system covering all areas, from farm (input) to end-of-life is useful in increasing relative comparability between and across fashion brands and products. Further, a comprehensive system such as this discourages the emphasis on certain areas by firms in an attempt to minimise attention on areas of neglect. Under each of the six summative sustainability categories within the model, particular measures of relative sustainability could be implemented (refer ).

A threshold per tier for each summative category would need to be determined, to apply the frame to on-product, consumer-facing labelling. Consideration of these thresholds will need take into account the extent to which it is reasonable for smaller or new firms to meet the same requirements as larger, more established firms. A simple means of communication of outcomes of the tiered system audit is recommended, whereby consumers can easily identify the relative sustainability of garments (refer ). Each summative category would be indicated in either green, red, or blank. Green meaning the garment meets the set threshold in that particular section of the supply chain, red meaning the garment is below the threshold, blank indicating the absence of that section of the supply chain in the manufacture of a garment. For example, a garment may be produced from upcycled or waste materials, hence not have a ‘farm’ level assessment, but materials assessed at the end-of-life stage. This type of categoric assessment helps deal with current problems such as garments that are sold as made of ‘recycled’ materials yet are unable to be disposed of ethically or further used at the end-of-life stage.

The benefit of a system such as this is that it could clearly and quickly alert customers of the relative sustainability of a garment. Further, consumers who have a particular ethical stance or emphasis on one aspect of sustainability, such as end-of-life, can quicky assess how a garment performs in that category. A preferential garment is easily identified with an all green ‘logo’. Vice versa, an all-red outcome serves to highlight how little the brand is doing to be sustainable. The high potential for all-red outcomes in the fashion industry highlights the growing need for mandates for such a system to really have an impact. Firms aware of their unsustainable profile would avoid using such a system, either preferring no labelling at all, or use of a self-label or third-party accreditation that spotlights singular aspects of their production. In this study, firms cited their use of what labelling was available as driven by a view that ‘it is the right thing to do. However, they understood, in regard to consumers ‘people do want it [sustainability], but don’t want to pay [extra for it]’. Government mandating of a clear and industry wide certification may address some of these issues, with support for more sustainable firms built into the certification and penalties for less sustainable fashion a further option.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this research was to examine the use of sustainability certification and labelling by Australasian fashion firms with a sustainable focus, resulting in the proposal of a taxonomy to guide the potential development of a singular, comparable sustainability certification, paired with a clear label cue for consumers. Consideration of sustainability issues across all product categories is growing and fashion is one area of focus for future change (Ritch, Citation2022). There is agreement in extant literature that the current multitude of labels, and lack of harmonisation across labelling formats is undesirable and must be addressed, for real industry change to occur (Gonçalves & Silva, Citation2021).

The results of this study identified a clear disconnect between available certifications and clarity of relative sustainability in the fashion industry. Supporting the notion that the current use of labelling in the fashion industry is confusing and potentially damaging to the message delivery of brands (Chun, Joung, Lim, & Ko, Citation2021), this study identified a consistent concern regarding certification and labelling useability. All firms that participated in this study were positive towards the concept or sustainability certification and labelling, yet all expressed frustration and dissatisfaction with currently available measures. Fashion sustainability labelling is known to consist of a complex multi-layer chain of methods (Gonçalves & Silva, Citation2021). Participants of this research felt that existing certifications were a step in the right direction, but that these systems have many flaws that impact brand interest and improved consumer understanding of what sustainability means regarding fashion.

It is accepted that, in the fashion industry, both the environment and its people suffer the impact of a damaging system (Roozen, Raedts, & Meijburg, Citation2021). A primary contribution of this research has been the framework for consolidation of fashion business requirements for sustainability labelling, into a singular form, able to be applied across varied fashion producers. This research thus adds to the existing academic literature on sustainable fashion and sustainable labelling research. There is an urgent need for uncomplicated tools in sustainability labelling, not only for the benefit of the end consumer, but for businesses to achive transparency in information about their products (Turunen & Halme, Citation2021). Solutions to the problems associated with measuring and communicating sustainability in fashion are urgent, however, for progressive action and development, firm engagement is equally as important as consumer perspectives. While this research offers a suggestion for a potential singular fashion certification approach, there is much work to be done in establishing what individual measures that make up the sustainability ‘scores’ within each category, and what makes an appropriate threshold for each, is required. Further, the question of mandating of any such label must be addressed in greater depth.

7. Limitations and future research directions

This study was limited to fashion brands that consider themselves to be sustainable, and already employ sustainability labelling and certification. It would be important, in the manner of this study, to also examine the perceptions of firms who do not currently employ certification or sustainability labelling (which may indeed represent a larger section of the industry). Understanding the reasons for non-use of sustainability certification is acritical next step in examining the feasibility of a singular, standardised labelling system. Further, this study was limited to the fashion brands that use certification and labelling, and did not include the views of third-party certification providers. Examining the certification process from this perspective would aid in the development of a process to underpin the use of a standardised label.

This study was sited in Australasia, where most fashion firms who view themselves as sustainable in their orientation are small in comparison to those seen in other countries. The addition of a large firm perspective would add depth to the research and may reveal information important to our understanding of sustainability certification in larger markets. While consumers were not included in this research, there is existing volume of evidence regarding consumer responses to different label formats, which supports the notion that current systems are not working as well as they could or should. However, there is also existing literature that considers the standardisation of labelling outside of the fashion industry (such as in electronics or food), which suggests that a singular, standardise labelling format is not only achievable, but desirable. Where this study and its taxonomy provide a starting point for discussion of the concept of a singular, potentially mandated, sustainability certification for fashion in Australasia, it is hoped that it will stimulate future exploration of this concept and related issues.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Anderson, J. 2010. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness, Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. Yale University Press, 2008. X + 293 pages [Paperback edition, penguin, 2009, 320 pages]. Economics and Philosophy, 26(3), 369–376. doi:10.1017/S0266267110000301

- Bach, V., Lehmann, A., Görmer, M., & Finkbeiner, M. (2018). Product environmental footprint (PEF) pilot phase – comparability over flexibility? Sustainability, 10(8), 2898.

- Bartholomew, G. (2020). Five sustainable fashion certifications to know about. In Supply Compass. Retrieved from https://supplycompass.com/sustainable-fashion-blog/sustainable-fashion-certifications/

- Bennett, L. (2017). Ethical fashion certifications and standards: What do the labels mean? In Good on you. Retrieved from https://goodonyou.eco/ethical-fashion-certifications-explained/

- Binet, F., Coste-Manière, I., Decombes, C., Grasselli, Y., Ouedermi, D., & Ramchandani, M. (2019). Fast fashion and sustainable consumption. In S. S. Muthu (Ed.), Fast fashion, fashion brands and sustainable consumption (pp. 19–35). Singapore: Springer.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Brewer, M. K. (2019). Slow fashion in a fast fashion world: Promoting sustainability and responsibility. Laws, 8(4), 24.

- Brydges, T., Henninger, C. E., & Hanlon, M. (2022). Selling sustainability: Investigating how Swedish fashion brands communicate sustainability to consumers. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 18(1), 357–370.

- Byrd, K., & Su, J. (2021). Investigating consumer behaviour for environmental, sustainable and social apparel. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 33(3), 336–352.

- Chen, J., Zhao, X., Lewis, M., & Squire, B. (2016). A multi-method investigation of buyer power and supplier motivation to share knowledge. Production and Operations Management, 25(3), 417–431.

- Chun, E., Joung, H., Lim, Y. J., & Ko, E. (2021). Business transparency and willingness to act environmentally conscious behavior: Applying the sustainable fashion evaluation system “higg index”. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 31(3), 437–452.

- Cook, D. P., & Luo, W. (2003). The role of third-party seals in building trust online. e-Service Journal, 2(3), 71–84.

- Diekel, F., Mikosch, N., Bach, V., & Finkbeiner, M. (2021). Life cycle based comparison of textile ecolabels. Sustainability, 13, 1751.

- Eco Cult. (2019). Is there a sustainable certification for clothing? [Your guide to eco- friendly and ethical labels]. In Eco Cult. Retrieved from https://ecocult.com/eco-friendly-ethical-sustainable-labels-certifications-clothing-fashion/

- Edie. (2021). Report: 60% of sustainability claims by fashion giants are greenwashing. In Edie Newsroom. Retrieved from https://www.edie.net/report-60-of-sustainability-claims-by-fashion-giants-are-greenwashing/

- Fashion United. (2021). Sustainability certification organizations in the fashion industry. In Fashion United. Retrieved from https://fashionunited.com/i/sustainability-certification-organizations-in-fashion/

- Future Learn. (2019). Sustainable fashion: Standards, certifications, and schemes. In Future learn. Retrieved from https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/sustainable-fashion/0/steps/13562

- Geiger, S. M., & Keller, J. (2018). Shopping for clothes and sensitivity to the suffering of others: The role of compassion and values in sustainable fashion consumption. Environment and Behavior, 50(10), 1119–1144.

- Gonçalves, A., & Silva, C. (2021). Looking for sustainability scoring in apparel: A review on environmental footprint. Social Impacts and Transparency. Energies, 14(11), 3032.

- Kim, K., & Kim, J. (2011). Third-party privacy certification as an online advertising strategy: An investigation of the factors affecting the relationship between third-party certification and initial trust. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 25(3), 145–158.

- Knošková, Ľ, & Garasová, P. (2019). The economic impact of consumer purchases in fast fashion stores. Studia Commercialia Bratislavensia, 12(41), 58–70.

- Lawless, E., & Medvedev, K. (2016). Assessment of sustainable design practices in the fashion industry: Experiences of eight small sustainable design companies in the northeastern and southeastern United States. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology & Education, 9, 41–50.

- Lee, E. J., Bae, J., & Kim, K. H. (2020). The effect of sustainable certification reputation on consumer behavior in the fashion industry: Focusing on the mechanism of congruence. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(2), 137–153.

- Lyon, T. P., & Montgomery, A. W. (2015). The means and End of greenwash. Organization & Environment, 28(2), 223–249.

- McKinsey & Company. (2020). The state of fashion. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/the%20state%20of%20fashion%202020%20navigating%20uncertainty/the-state-of-fashion-2020-final.pdf

- McKinsey & Company. (2021). The state of fashion. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2021/the-state-of-fashion-2021-vf.pdf

- Ministry for Primary Industries. (2022). Health star ratings and food labelling. Retrieved from https://www.mpi.govt.nz/food-business/labelling-composition-food-drinks/health-star-ratings-food-labelling/

- Mukendi, A., Davies, I., Glozer, S., & McDonagh, P. (2020). Sustainable fashion: Current and future research directions. European Journal of Marketing, 54(11), 2873–2909.

- NZ Consumer (2020). Energy rating labels explained. Retrieved from https://www.consumer.org.nz/articles/energy-rating-labels-explained

- NZ Transport Agency. (2022). Vehicle safety ratings. Retrieved from https://www.nzta.govt.nz/safety/vehicle-safety/vehicle-safety-ratings/

- Oelze, N., Gruchmann, T., & Brandenburg, M. (2020). Motivating factors for implementing apparel certification schemes – a sustainable supply chain management perspective. Sustainability, 12(12), 4823.

- Radhakrishnan, S. (2014). The sustainable apparel coalition and the Higg Index. In S. Muthu (Ed.), Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing. Textile Science and Clothing Technology. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-287-164-0.

- Rahman, O., & Koszewska, M. (2020). A study of consumer choice between sustainable and non-sustainable apparel cues in Poland. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(2), 213–234.

- Ranasinghe, L., & Jayasooriya, V. M. (2021). Ecolabelling in textile industry: A review. Resources, Environment and Sustainability, 6, 100037.

- Razvi, A. (2022). Retrieved from https://apparelcoalition.org/team/amina-razvi/

- Reichart, E., & Drew, D. (2019). By the numbers: The economic, social and environmental impacts of “fast fashion”. https://www.wri.org/insights/numbers-economic-social-and-environmental-impacts-fast-fashion

- Ritch, E. L. (2022). Consumer interpretations of fashion sustainability terminology communicated through labelling. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 26(5), 741–758.

- Roozen, I., Raedts, M., & Meijburg, L. (2021). Do verbal and visual nudges influence consumers’ choice for sustainable fashion? Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 12(4), 327–342.

- Sailer, A., Wilfing, H., & Straus, E. (2022). Greenwashing and bluewashing in black friday-related sustainable fashion marketing on Instagram. Sustainability, 14(3), 1494.

- Schwartz, D., Loewenstein, G., & Agüero-Gaete, L. (2020). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour through green identity labelling. Nature Sustainability, 3, 746–752.

- Shirvanimoghaddam, K., Motamed, B., Ramakrishna, S., & Naebe, M. (2020). Death by waste: Fashion and textile circular economy case. Science of The Total Environment, 718, 137317.

- Sustain your Style. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.sustainyourstyle.org/en/blog/2020/6/9/is-the-fashion-industry-going-greener

- The Sustainable Fashion Forum. (2022). With so many Industry ‘tools’ coming under fire, what is the role of third party certification and ranking systems? Retrieved from https://www.thesustainablefashionforum.com/pages/what-is-the-role-of-sustainable-fashion-certifications

- The New York Times. (2022). How fashion giants recast plastic as good for the planet. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/12/climate/vegan-leather-synthetics-fashion-industry.html?searchResultPosition=1

- Todeschini, B. V., Cortimiglia, M. N., Callegaro-de-Menezes, D., & Ghezzi, A. (2017). Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Business Horizons, 60(6), 759–770.

- Turunen, L. L. M., & Halme, M. (2021). Communicating actionable sustainability information to consumers: The shades of green instrument for fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production, 297, 126605.

- Urbański, M., & Ul Haque, A. (2020). Are you environmentally conscious enough to differentiate between greenwashed and sustainable items? A Global Consumers Perspective. Sustainability, 12(5), 1786.

- Wang, L., Xu, Y., Lee, H., & Li, A. (2022). Preferred product attributes for sustainable outdoor apparel: A conjoint analysis approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 657–671.

- Zhang, H., & Song, M. (2020). Do first-movers in marketing sustainable products enjoy sustainable advantages? A Seven-Country Comparative Study. Sustainability, 12(2), 450.

- B Corporation. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/certification

- Better Cotton Initiative. (2022). Retrieved https://bettercotton.org/

- Bluesign. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.bluesign.com/en

- Fairtrade International. (2022). How fairtrade certification works. Retrieved from https://www.fairtrade.net/about/certification

- Forest Stewardship Council. (2022). Retrieved https://fsc.org/en

- Global Organic Textile Standard. (2022). Certification and labelling. Retrieved from https://global-standard.org/certification-and-labelling/certification#approvedconsultants

- Global Slavery Index. (2018). The Global Slavery Index. Retrieved from https://www.globalslaveryindex.org/

- Oeko-Tex. (2022). Certification according to standard 100 by Oeko-Tex. Retrieved from https://www.oeko-tex.com/en/apply-here/standard-100-by-oeko-tex

- Textile Exchange. (2022). Organic content Standard 3.0. Retrieved from https://textileexchange.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/OCS-101-V3.0-Organic-Content-Standard.pdf

- Textile Exchange. (2022). Standards claims policy. Retrieved from https://textileexchange.org/documents/standards-claims-policy/

- Textile Exchange. (2022). Recycled claim standard and global recycled standard. Retrieved from https://textileexchange.org/standards/recycled-claim-standard-global-recycled-standard/

- Textile Exchange. (2022). Responsible down standard. https://textileexchange.org/standards/responsible-down/

- Textile Exchange. (2022). Responsible wool standard. Retrieved from https://textileexchange.org/standards/responsible-wool/

- ZQ Natural Fibre. (2022). Retrieved from https://www.discoverzq.com/zqrx