Abstract

Discerning what populists mean by the people is crucial for understanding populism. However, the appeals populists make to the people differ across political systems, with distinctions particularly evident between democratic contexts and one-party states such as China. Articulations of the people in Chinese populist communication remain underexplored, which is a gap this paper addresses by clarifying how the people is constructed in the discourses that underpin Chinese populism. A total of 61 populism cases were examined through discourse and meta-analyses, from which three manifestations of the people emerged. First, the Chinese nation serves as an ideological glue to mobilize people to protest against those seen as betraying their Chinese identity or violating the sovereignty and dignity of China. Second, the mass is associated with an affective aversion to scientists and experts, but also with mass support for a satirical subculture that challenges the hegemony of elite-dominated cultural production and cultural institutions. Finally, socially vulnerable groups assemble powerless people in situations of economic impoverishment, political marginalization, and social vulnerability. The analysis reveals how these three conceptualizations of the people drive online Chinese bottom-up populism, allowing netizens to serve as mediators and pitting the people against corrupt elites and the establishment.

Introduction

Populism is “an essentially contested concept” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 2) and has been defined as an ideology (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017), a political strategy (Weyland, Citation2017), a sociocultural phenomenon (Ostiguy, Citation2017), a discourse (Laclau, Citation2005), a political style (Moffitt, Citation2016), and a social movement (Aslanidis, Citation2017). Despite the high degree of variability in how scholars conceptualize populism, there has been consensus that its essence lies in (1) the centrality of “the people” and (2) an antagonism between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” that populists advocate for. Given its centrality in defining populism, an explicit connotation of the peopleFootnote1 is crucial (Canovan, Citation2005). However, in populists’ discourses, different conceptions of the people are often used in combination with—or even interchangeably with—one another. Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2017) argue that the people are often used in a flexible interweaving of three meanings: as sovereign, as the common people, and as the nation. Canovan (Citation1999) identifies three different senses of the people: the united people, our people, and ordinary people, while Mény and Surel (Citation2002) distinguish the people as political (people-sovereign), economic (people-class), and cultural (people-nation). However, Laclau (Citation2005) considers the people an “empty signifier” used strategically by different political actors. This conceptual malleability and flexibility of the idea of the people have allowed populists to frame it to suit their interests, which is part of what “makes populism such a powerful political ideology and phenomenon” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 9).

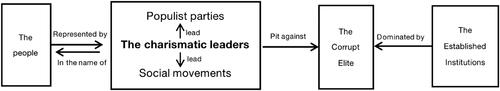

Conceptions of the people have primarily been rooted in Western or Latin American contexts, where electable charismatic leaders function as the mediators of populism, appealing in the name of “the pure people” against “the corrupt elite.” This understanding is regarded as a top-down approach (see ).

However, few studies have addressed the populist constructions and properties of the people in China, where neither charismatic leaders nor viable populist parties exist. Although there is a significant body of work on populism in China (He et al., Citation2021), this research has mainly been published in Chinese and in Chinese journals, hence remaining largely unknown to international scholars. In these studies, when conceptualizations of the people are addressed, the connotations and characteristics of the people are not fully and systematically revealed. For instance, Yu (Citation1997) considers populism as a social trend, highlighting the value and idea of “pingmin qunzhong” (ordinary mass), and Chen (Citation2011) regards online populism as a trend of extreme plebeian democratization (pingminhua). Tao argues that “the internet is inherently populist” (2009, p. 46) and that tech companies will adapt to the wishes of the “wangmin” (netizens), equating “the people” to netizens. Conceptualizations of the people become even more complicated when they are interwoven with other concepts, such as minzhong (the public) (Liu, Citation2017), baixing (common people), qunzhong (the mass), wangmin (netizens) (Tao, Citation2009), ruoshi qunti (vulnerable groups) (Li & Xu, Citation2012), and caogen (grassroots) (Tai, Citation2015). These disparate conceptualizations point to a pressing need to systematically disentangle the meanings attached to people. The present paper addresses this gap by investigating how the concept of the people is constructed in relation to Chinese populism.

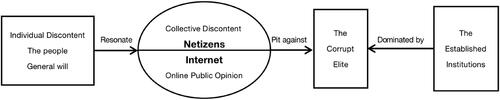

Following a discourse approach (De Cleen, Citation2019; Laclau, Citation2005), populism is regarded as a discourse revolving around the antagonism between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite.” Although the people is discursively constructed as a large powerless group, the elite is conceived as a small and illegitimately powerful group. Populist politics claims to represent “the people” against “the elite,” who are portrayed as no longer representing the general will of “the people” (De Cleen, Citation2019; Laclau, Citation2005). Following this discursive approach, the discursive power of the people is analyzed. Discursive power refers to “the degree to which the categories of thought, symbolizations, and linguistic conventions, and meaningful models of “the people” determine the ability of some actors to control the actions of others, or to obtain new capacities” (Reed, Citation2013, p. 203). Considering the distinct structural, ideological, and historical features of Chinese populism (He et al., Citation2021), we argue that studying how the people is conceptualized in Chinese populism has theoretical implications for understanding populism globally. First, it enhances our understanding of the core nodal point of populism—the people—and applies this beyond democratic contexts. Second, disentangling the various meanings attached to the people in China allows for a more comprehensive understanding of populism as a bottom-up phenomenon, which contrasts with the dominant, largely top-down understanding of populism (see ). Third, the categories that emerged not only reflect, but also provide a prism to further explore the dynamic interactions in how “the people/elite” or “self/other” relationships are imagined in Chinese populist discourses.

Tensions around the people

Conceptual tensions around the people primarily manifest along two axes: the vertical axis of power and horizontal axis of boundaries (Canovan, Citation2005; Espejo, Citation2017). Using these axes, this section reviews debates around the volatile concept of the people and from where its discursive power stems.

The power of the people: the titular holders and actual wielders

Populist appeals in the name of “the people” or as representing “the people” sit within the triangular relationship of “people-power-populism,” which has not been thoroughly explored in populism research (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017). According to Macpherson (Citation1973), power is the “ability [of the individual] to use and develop his essential humane capacities” (p. 50). However, the crucial problem is “the one between titular holders and actual wielders” of power (Sartori, Citation1987, p. 29). The discursive power of the people stems from the contradiction between those who are said to be in power in society and those who really are. According to modern democratic theories, legitimacy and political power rest on the sovereign people, who are at least the titular holders of societal power. This understanding also underpins populists’ argument that “politics should be an expression of the general will of the people” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 6) as “the fundamental rule of government” and “a form of deliberative reason that each citizen shares with all other citizens in virtue of their sharing a conception of their common good” (Rawls, Citation2007, p. 224). This not only implies following the principal of majority rule, but it also suggests that the general will is always right and tends toward the public good (Rawls, Citation2007). Thus, by claiming to present the general will of “the people,” populists associate themselves with this moral priority and feel empowered by majority support. Those who oppose populists (e.g. during a political campaign) are then described as going against the general will of “the people” (Espejo, Citation2017).

In practice, whether seen as individuals or as a collective body, people are not the actual wielders of power. To ensure the effectiveness of democratic processes and maintain a measure of freedom for elected politicians, individual and private wills are made subservient to the collective will in the elective procedures of modern democracies, leading to the formation of a collective people (Rousseau, Citation2016). However, for populists, the elective procedures and representational transmission of power cannot ensure that the people are the actual wielders of power because those who delegate their power cannot be sure their individual interests will be advocated for. In practice, the actual holders of power are those “corrupt elites” who “are defined on the basis of power,” including those who “hold leading positions within politics, the economy, the media, and the arts” (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017, p. 12). Within populist rhetoric, the elites are framed as corrupt and accused of betraying and not representing the general will of “the people.”

The demarcation of the people: inclusiveness and exclusiveness

The demarcations surrounding the people have allowed it to be conceptualized as both inclusive and exclusive. Agamben (Citation2000) uses the People (capital) and the people (lowercase) to address these distinctions. Although as an inclusive concept the People refers to a whole and integral political body, the people (lowercase) as an exclusive concept represents the “subset and fragmentary multiplicity of needy and excluded bodies” (Agamben, Citation2000, p. 30). This fundamental split reveals the conceptual fuzziness of the people. It is within this tension and uncertainty, the people is used “to formulate potentially any demand, defend, or contest any political project, ideology, or regime” (De Cleen, Citation2019, p. 20), and to defend any political system who claims to be acting on behalf of the people (Sartori, Citation1987).

When the people is framed as a relatively inclusive concept, it is unifying, capturing as many people as possible. This reflects the expanding boundaries of the people that have developed in Western political thought. MacClelland (Citation2005) sees this as an “expansion of the idea of the people eventually to include every man and woman” (p. 146). However, the inclusive conception of the people also contributes to cognitive ambiguity and practical tensions. On the one hand, the larger the scale, the more we need to treat the people as a united abstract construction, “which grounds the legitimacy of the democratic state through a constitution” (Espejo, Citation2017, p. 612). On the other hand, abiding by the mechanism of representative democracy, individuals are compelled to submit their sovereign rights to the collective body and will. As a result, the impact and rights of individuals are neglected.

Because populism operates in national contexts, being part of a nation and sharing its characteristics (Sun, Citation2019) are the primary criteria for belonging to the people. The nation provides “a sense of where to look for the prepolitical basis of political community” (Yack, Citation2001, p. 524). The national characteristics of the people exclude “others” from it. This exclusive conception of the people derives from a politically subjective identity and distinctive personality characteristics rooted in the idea of the nation. In addition, the exclusive understanding of the people also refers to the common people in general, including “the poor, underprivileged and the excluded” (Agamben, Citation2000, p. 29). Privileged rulers, political elites, and the upper classes are typically excluded from this conception of the people. These understandings of populism and the people have been developed and studied in Western contexts, where democratic legitimacy rests on electable sovereign people. However, in a party state such as China, further considerations of what is meant by the people complicate the understanding of populism even more.

The discursive power of the people in the Chinese context

In Chinese, the people has many synonyms, making the concept difficult to disentangle. Defining the people as qunzhong (mass) and dazhong (populace) indicates that the people are the majority in society. Similarly, shumin (plebeian), pingmin (civilian), and baixing (common people) refer to people as objects of governance from a “ruler and ruled” perspective. In this sense, the concept of min (the people) excludes rulers and the privileged. In ancient China, governmental power was not legitimized by the people (the emperors claimed a divine mandate), but the people did legitimize “noble politics.” The idea that “noble politics” should represent the will of the people is deeply ingrained in China’s ancient political thought of “yimin weiben, or the primacy of the people.” This notion can be traced back two millennia to Shangshu (Book of History), which proclaims that “the people are the sole foundation of the state; when the foundation is firm, the state is peaceful” (as cited by Perry, Citation2015, p. 905).

This idea of “noble politics” is reflected in the discourse of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which understands the people as an inclusive notion. For example, qunzhong (mass) in the Mass Line discourse (1920s–1970s), zui guangda renmin (overwhelming majority of the people) in the Three Represents discourse (1990s–2000s), and the zhonghua minzu (Chinese nation) in the Rejuvenation discourse (2010s–now) all attempt to include as many people as possible. Historically, the authority of the CCP has been further legitimated by liberating the people from colonial oppression. This inclusive discursive construction of the people (Wu, Citation2017) and a savior image of the CCP legitimates its governance as “noble politics.” This limits the possibility and weakens the discursive power when populists make appeals in the name of “the people.”

With wide access to the internet in contemporary China (since the 1990s), the people in China are afforded channels to express their voices, appeals, and even discontent online and directly. This has given rise to a form of online populism (Chen, Citation2011; Li & Xu, Citation2012; Tao, Citation2009; Xia, Citation2014). Netizens, here referring to the people who use the internet as “citizens of the net” (Hauben & Hauben, Citation1997), are key to understanding Chinese online populism. According to the 49th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, the number of netizens reached 1.032 billion in December 2021, accounting for 73.13% of China’s population. The high overlap between the people and netizens means that the appeals and voices of netizens may partly represent the will of the people (Chen, Citation2011; Tao, Citation2009). This is why the government regards netizens’ online discussions as a “parameter” for policy making (Luo, Citation2014). Importantly, although the rich, privileged, and upper classes are considered distinct from the people, they are not explicitly excluded from the notion of netizens. This hybrid nature of netizens raises key questions: To what extent do netizens function as populist mediators in China, similar to charismatic leaders in top-down approaches (see )? Who exactly are “the people,” when netizens also appeal in the name of “the people?” Are netizens populists? The answers to these questions can shed light on the interactive dynamics between “the people” and netizens, “the elite” and “the other,” and netizens and the establishment in China.

Methodology

The research design consisted of three steps. First, prominent cases of populism between 1990 (the start of the third wave of populism) and 2020 were identified from the literature. Relevant articles were identified by searching for the term “mincui” (which translates into “populism” in English and is the root word for other derivations of this term; cf. He et al., Citation2021) in the titles of articles in journals indexed by the Chinese Social Science Citation Index and included in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (the largest database of full-text articles in China). This search resulted in 357 articles. After narrowing this sample to academic articles that explicitly addressed contemporary populism cases in mainland China (128 articles) and cases studied by at least two scholars (a case mentioned by the same author in different papers counts as one case), 61 cases were included. We then identified a keyword to label each case. The most frequently used label by scholars was selected as the keyword for each case. These selection procedures have ensured, at least to some extent, that the cases selected related to populism and were academically accepted by scholars, separating them from other online collective actions.

To disentangle the different meanings attached to the people, we look to two sources for data collection. For more recent cases, we searched on Baidu Tieba, Sina Weibo, and Zhihu for the popular discourse about the selected cases. The three platforms were selected because they provide “a social realm for citizens to detect issues of public concern from citizen’s lifeworld and engage in relevant public discourse” (Sun et al., Citation2021). To identify these discourses, we first searched these platforms using the keywords from each of the populism cases, particularly focusing on data, such as posts, comments, memes packs, and so forth, not only from popular discourse, but also from official media accounts (e.g. People’s Daily). For the data from Zhihu and Baidu Tieba, the 10 most-commented posts and the corresponding comments of each case were gathered. As for Sina Weibo data, because of its censorship features, only posts of related cases from official media were gathered. For earlier cases, we relied on how scholars discussed popular discourse in scholarly publications and how contemporary online discourse refers back to earlier cases of populism as a context. For example, the Sun Zhigang case in 2003Footnote2 is often referred to when netizens discuss the Lei Yang case in 2016Footnote3 since both Sun and Lei died because of physical abuse and misconduct while detained.

In the second step, the sample was narrowed down by clustering cases. First, a textual analysis was conducted to identify the two antagonistic sides of each case. Then, following a discourse analysis framework proposed by De Cleen (Citation2019), the investigation focused on how populist antagonism between “the people” as a large powerless group and “the elite” as a small and illegitimately powerful group has been discursively constructed (De Cleen, Citation2019). This allowed for the classification of the 61 cases into three supra-categories (see ): exclusion (6 cases), anti-intellectualism (9 cases), and antiestablishment (46 cases). In the third step, from this categorization, specific cases were selected to empirically explore how the people is conceptualized in Chinese populism. For each category, one case was selected using discourse analysis to further unpack the different concepts of the people based on their political and cultural influence.

Table 1. The result of clustering of 61 populism cases.

Findings

Exclusion: the Chinese nation as an ideological glue

Exclusion is reflected in the cases of revolting against foreign others (or “ultranationalism”) (Schroeder, Citation2021) and in those elites who are seen as betraying their Chinese identity. The dominant meaning attached to populist conceptions of the people in this category is the Chinese nation (zhonghua minzu).

The Diba Expedition case, where active netizens mobilized against Chou Tzu-yu, a 16-year-old Taiwanese singer, reflects how the people of the Chinese nation function as an ideological glue to mobilize followers. Diba is an online community based on Baidu Post-bar (Tieba), which has more than 30 million followers. On January 15, 2016, Chou posted an apology video after she was criticized in mainland China for waving the flag of the Republic of China (the formal name for Taiwan) on a South Korean TV show. In the video, Chou bowed in front of the camera and apologized for her inappropriate behavior, stating that “the two sides across the Strait are the same and one. I always feel proud of being Chinese.” Chou’s apology sparked a furor among the Taiwanese public on election day, with Tsai Ing-wen, the proindependence Taiwanese presidential candidate, expressing her support for Chou. In response, Diba collectively mobilized its followers to bypass firewall restrictions and occupy the Facebook page of Tsai Ing-wen at exactly 7 p.m. on January 20, 2016. Users posted, “When Diba goes to battle, no grass will survive,” more than 26,000 comments were posted on Tsai’s Facebook pages within four hours.

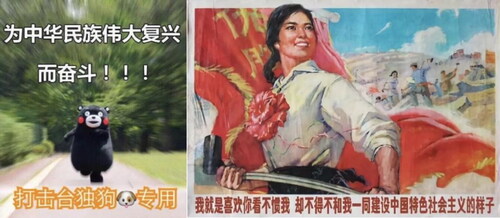

The online comments posted by Diba netizens reflected the netizens’ sense of belonging to the Chinese nation. They criticized Tsai for betraying her Chinese identity, bombarding her Facebook page with texts and “weaponized” internet memes (see ), including the Chinese national flag, political iconography, exaggerated embarrassing facial expressions of political and cultural elites, national anthem, patriotic poems, songs, and more. Political slogans, such as “fight for the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (see ) and “the Chinese nation faces its greatest peril” further demonstrated the netizens’ articulation of a Chinese national identity and their belonging to it. By using “weaponized” internet memes, Diba netizens not only critiqued these perceived enemies, but also successfully defended the Chinese nation. As a result, netizens’ patriotic campaign won praise from the official media, the People’s Daily (Citation2016), who described them as “good sons and daughters of the Chinese nation” contributing to “the ‘great rejuvenation’ of the Chinese nation.”

Figure 2. Memes used by mainland netizens in the Diba Facebook Expedition. Source: http://www.shwilling.com/portal/index/detail/58235

Table 2. Forms and content of “expedition weapons.”

This case further underlines how the conceptualization of the Chinese nation draws on a historical sense of solidarity to mobilize and protest against external others and perceived enemies. For national populism, this resonates with the historical self-image of “China as victor” and “China as victim” (Gries, Citation2004). As a victim, the Chinese nation is seen as a historically oppressed victim of imperialist aggressors dating back to the First Opium War (1839–1842). This framing is used to offer “the psychological strength to mobilize the Chinese people” (Gries, Citation2004, p. 80) in an expansive way. Within the concept of the Chinese nation, its people includes the people in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, here based on a shared historical experience because all were the victims of Western colonialism. Consequently, populist activities against external others are encouraged. On the other hand, portraying “China as victor” promotes the CCP as the savior of the Chinese nation. This framing allows the Chinese nation to be conceived of in terms of its historical strengths, reinforcing how the CCP succeeded in fighting for the whole nation against imperialist aggressors in the War of Resistance that ended the Century of Humiliation (1840–1949). This particular framing follows Maoist top-down narratives, which state that there would be no new China without the leadership of, first, Mao and then the CCP (Gries, Citation2004). As a result, the heroic narrative of “China as victor” redirects the populist discursive power away from established institutions led by the CCP.

These attempts to unite the people as the Chinese nation function as an ideological glue uniting those who agree with Chinese nationalism. In line with this inclusive conceptualization, Fei (Citation1988) identifies the Chinese nation as the people who reside in the territory of China and “have the unified consciousness of a nationality.” He argues that the Chinese nation conveys plurality and unity at the same time: “pluralistic because fifty-odd ethnic units are included, unified because together they make up the Chinese peopleFootnote4” (p. 167). In contrast to Fei’s conception of the Chinese nation, which is restricted to China’s territory, Perry (Citation2015) expands the concept to “not only to domestic constituency, but also to overseas Chinese who are expected to identify culturally and sympathize emotionally with the rise of the motherland” (p. 910). As we have seen in this case, the Chinese nation functions as an “ideological glue” that refers to more than a nation-state and its formal territories.

Anti-intellectualism: the mass resist through parody and satire

The second meaning attached to the people is the mass (dazhong). This concept is characterized not only by an anti-intellectualism associated with the affective aversion to scientists and experts (Hofstadter, Citation1963), but also through support for a satirical subculture advocated for by the masses that challenges the hegemony of elite-dominated cultural production and cultural institutions (Sun, Citation2006). The people as the mass reveal the tension and dynamic between the masses and experts and mundane culture and elite culture, particularly highlighting the wisdom, identity, and value of ordinary people in cultural production while challenging the cultural and intellectual authority of the elite.

As a collective body in these populist cases, the masses unite in satirizing and challenging the taste, value, and identity of the elite (Chen, Citation2014). Thus, “in the name of the mass” became the most appealing subtext in Chinese cultural populism (Sun, Citation2006). We selected CCSTV Spring Festival Gala (China Countryside Television, Shanzhai Chunwan) as an illustrative case study because of its impact on the rise of Shanzhai culture (De Kloet & Chow, Citation2017. Shanzhai culture has a rebellious nature (De Kloet & Chow, Citation2017), intending to delegitimize the authority of elite-dominant cultural institutions through comedic imitation (Chen, Citation2014). The CCSTV Spring Festival Gala was initiated by Mengqi Shi, a Beijing-based cameraman. After attending the official CCTV Spring Festival Gala, he criticized it for being “not designed for the ordinary audience…, the audience was nothing but high officials and rich people” (Lee, Citation2012). Hence, he organized a program produced by and for ordinary people: the CCSTV Gala. More than 700 groups and individuals from a grassroots context applied to appear. At first, the national satellite station Guizhou TV offered a channel to broadcast the CCSTV Gala on TV; however, Shi decided to broadcast online to maintain its grassroots nature.

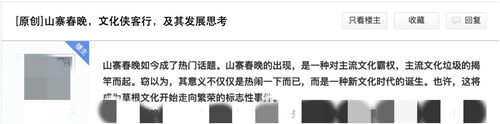

With its grassroots origin and rebellious characteristics, Shanzhai Chunwan delegitimized the authorities of elite-dominated cultural productions and institutions by highlighting the taste, identity, and value of the mass. Its theme song had lines such as “The bad New Year’s Gala from ‘Angshi’ is rotten everywhere” (jesting the pronunciation of CCTV “Yangshi”), and “the good directors of Shanzhai Chunwan, forever move forward, the good Chunwan for the people.” Online, this is underscored when discussed by netizens: “the emergence of Shanzhai Chunwan, is a rebellion against the hegemony of mainstream culture. This will be a landmark event in which grassroots culture begins to prosper” (translated from netizen’s online discussion. See ).

The people as the mass adopt parody in a way that “puts social conventions on display for collective reflection” (Hariman, Citation2008, p. 251) as the central strategy to demonstrate discontent toward intellectuals (Chen, Citation2011). As a deconstructing and delegitimizing strategy, parody manifests itself in two ways. First, from the political-cultural perspective, it uses targeted language to revolt against established norms and values (Gong & Yang, Citation2010). The legitimacy of “Yangshi” (pronunciation of CCTV) is delegitimized through the use of a different word, “Angshi” (similar pronunciation, means “look up from below”), which parodies the pronunciation. Further, the titles of elites are satirized, replacing them with words with the same pronunciation but different meanings. For example, 教授 (jiaoshou) meaning “professor,” is satirized as 叫兽 (also jiaoshou), meaning “the roaring beast.” The satirical revision of titles not only shows the mass’ distrust and anti-intellectual sentiment (Liu, Citation2017), but it is also subversive, pitting carnivalesque (Bakhtin, Citation1984) and iconoclastic messages against elite authorities. Through this linguistic carnival, the discursive power of the intellectual elite is suspended (Bakhtin, Citation1984). Second, from a political-economical perspective, the mass challenges the hegemonic, orthodox status quo of elite-dominated cultural institutions. Again, using parody, the mass can engage in a grassroots and mass-participant form of cultural criticism. For example, netizens expressed disinterest in the CCTV New Year’s Gala, challenging the authority by describing the CCSTV Spring Festival Gala as reflecting their tastes and values.

Although established institutions can still maintain elite culture by making use of the censorship regime and removing alternative voices (Li, Citation2011), parody from a technologically attuned mass nevertheless offers a populist antielite form of rebellion. These cultural populism phenomena demonstrate the combination of “the traditional Chinese metaphor of grassroots antiestablishment heroism” and the “modern rhetoric of technology-empowered bottom-up democracy” (Zhang & Fung, Citation2013, p. 402).

Antiestablishment: socially vulnerable groups and internet-enabled collective protest

In the 46 cases of antiestablishment populist dynamics, the people was defined as socially vulnerable groups (shehui ruoshi qunti, SVG). Within online populist rhetoric, antiestablishment refers to an opposition to those wielding power, a form of populist discontent stemming from the disparity between those who hold no power (e.g. workers and peasants, ordinary people, local people, students, the “good,” doctors, and prostitutes) and those who do (e.g. police officers, urban management officers, rich second generation, powerful state apparatus). Online populist antiestablishment politics are distinct from previous anti-intellectual attitudes because of their emphasis on power. In these cases, netizens function as mediators, appealing in the name of the powerless and vulnerable parts of the Chinese public (Li & Xu, Citation2012) who experience economic impoverishment, political marginalization, or social vulnerability.

The conceptualization of SVG is a dynamic grouping because vulnerability arising out of political marginalization can change over time. This dynamic feature resonates with Agamben’s (Citation2000) conception of the people (lowercase), and Laclau’s (Citation2005) description of the people as an “empty signifier” because the nature of vulnerability at the core for the SVG categorization is both relative and highly dynamic. This conception of the people can be seen as both inclusive and exclusive; members of the SVG might become powerful, and vice versa, political actors can become vulnerable if they fall out of favor or power with the government. This can occur when a government official is found to be corrupt, but also when social or business elites disrupt the stability of the CCP’s governance. Although this allows us to imagine the SVG as a rather broad and dynamic notion, the nature of this category takes on even more significance when applied to Chinese populists’ articulation of the people in terms of the “people-elite-government” relationship.

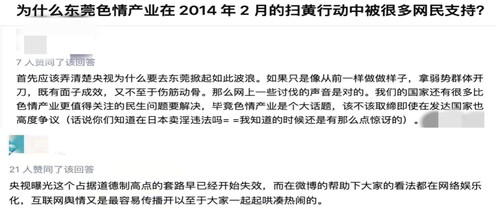

Forming an SVG identity and mobilizing netizens to protest against the establishment are strategies applied within online populist movements. One example is the Dongguan antipornography movement in 2014. Although prostitution is illegal in China, Dongguan prostitutes gained sympathy from netizens who regarded them as members of the collective “us” of socially vulnerable groups (Xia, Citation2014) when CCTV journalists uncovered pornographic KTV (karaoke) using hidden cameras in 2014. After this was reported, more than six thousand police agents wiped out local KTVs (Tai, Citation2015). Southern Metropolis Daily, an influential local newspaper in south China, posted the following on their Weibo accounts:

Hold on to Dongguan!—It is not that the media cannot report on the porn industry. Whether this primitive industry still has violence, blood, and tears, the living conditions of prostitutes, and the protection of power behind repeated prohibitions, it needs media attention. Only by the truth can Dongguan prostitutes truly not cry.

Figure 4. Zhihu discussion on Dongguan Antipornography Movement. Source: Zhihu post, February 13, 2013.

This analysis shows how netizens function as mediators between the people and the elite, that is, between the powerless and the powerful. For understanding online populism in China, this considers the self-empowering affordances of the internet (Shi & Yang, Citation2016), which allows SVG to become netizens, including how the people as SVG align with netizens to directly express their voices online. Furthermore, like the SVG, netizens are also regarded as at the bottom of Chinese society,Footnote6 which might explain why netizens are often portrayed sympathetically and why they often align with the SVG to respond aggressively toward corrupt, rich, and powerful elites (Chen, Citation2011). However, the hybrid and semianonymous features of netizens pose new challenges for understanding online populism in China. First, the overall number of Chinese netizens means the elite, the establishment, and the powerful may also use the internet to sway online public opinion to meet their interests. As a result, the appeals, voices, and concerns turn out to be what these powerful groups want people to see, rather than the real will of the people. Second, the semianonymous state of the internet may promote the generation of fake news, hate speech, and disinformation, which can further polarize society and work against the interests of the people.

Discussion and conclusion

The present study has explored the meanings attached to the people in an effort to disentangle the multifarious populism phenomenon in China. The three conceptualizations of the people as Chinese nation, the mass and socially vulnerable groups refer to three subtypes of populism: national populism, cultural populism, and online bottom-up populism. These categories have emerged by disentangling the meanings attached to the people, both in research and popular discourse, reflecting the dynamic relationship of “people/elite” or “self/other” that are imagined in Chinese populist discourse. This provides a prism to further explore the populist dynamic relationship between the people (netizens), the elite (other), and the government.

Disentangling these meanings of the people helps explain different orientations between the “people/elite” and “netizens/other” that are core to understanding populism. The Chinese nation emerges as an ethnocultural construction, functioning as an ideological glue to capture all Chinese people under one nation. This is an inclusive term, encompassing all those who have a sense of belonging, whether at home in China or abroad. The Chinese nation became “a conscious national entity only during the past century, as a result of China’s confrontation with the Western powers” (Fei, Citation1988, p. 167). This calls on the historical and leading role of the CCP in wars against colonial “others,” rescuing the Chinese nation from 100 years of suffering. In channeling the Chinese nation, memories of war provide “a patriotic nationalist narrative of heroic resistance” (Coble, Citation2007, p. 394).

Seeing the people as the mass emerges in instances when people are identified through an anti-intellectual attitude and support for a satirical subculture. This challenges hegemonic, elite-dominated cultural institutions, including through carnivalesque parody and imitation. Through such protests, the masses can challenge the cultural hegemony of state-owned media such as CCTV. The masses deconstruct the authority of elites and express anti-intellectual attitudes; this is, to some extent, tolerated in China (Chen, Citation2011). These populist cultural practices advocate for the taste, identity, and values of the mass, while also demonstrating that the mass has gradually lost trust in intellectuals and the elite. In traditional Chinese culture, intellectuals should “pray for the people” (Chen, Citation2016). However, in current China, the elite culture has converged with mainstream culture, as guided by the CCP. Therefore, intellectuals are criticized for being an elite mouthpiece, reflecting and promoting government narratives (Chen, Citation2016, p. 130).

Socially vulnerable groups, as the third category, refers to those who occupy a subaltern position in terms of status and financial stability and who are powerless in policy formation. The affordances of networked platforms provide relatively autonomous and anonymous spaces for SVG members to express grievances and discontent toward those in power, opening previously unavailable channels for rights-preserving (weiquan) online. These online rights-preserving activities can sway public opinion and trigger emotional outbursts, and in doing so, they can also increase ideological segregation between SVG and elite groups. Thus, online rights-preserving activities are subject to stability maintenance (weiwen) from the government. This results in further populist antagonism between “the people” and elite, reinforcing a triangular relationship between the SVG, the elite, and the government. These dynamics can lead to change. Because populist antiestablishment rhetoric is perceived as threatening the authority of the CCP, corrupt elites are often removed from the party when it becomes untenable for the authorities to keep them in power in the face of populist accusations of corruption. In these instances, we see a response prompted by populist appeals on behalf of vulnerable people that also maintains the government’s authority: corrupt elites become the enemy of both “the people” and the CCP. As a relative and dynamic concept, these cases also show that the elites can fall within the SVG when facing a powerful state apparatus.

By disentangling the meaning attached to the people, a distinctive feature can be identified in contemporary Chinese online populism, where netizens serve as mediators, pitting “the people” against “corrupt elites” and the establishment. This distinctive feature further reinforces how we can understand populism in China when compared with European or American contexts. If populism in the latter contexts is understood as a top-down approach, where populist leaders and parties function as the mediators between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” (see ), online populism in China can be understood through its bottom-up nature (see ). In this more bottom-up approach, the people, which can be covered by the semianonymous features of digital media, can raise public concern and discontent collectively (see also He et al., Citation2021). This online and bottom-up understanding of populism in China reflects the interaction of multiple dynamics between the people and netizens and the people and others, demonstrating “people’s power in the Internet age” (Yang, Citation2009, p. 1). When the netizens appeal in the name of the Chinese nation against foreign others or those who are perceived as betraying a Chinese identity, there seems to be a high degree of uniformity between the people, the netizens, and the government, as evidenced in the case of the Diba expeditions. When netizens make appeals on behalf of socially vulnerable groups, they construct “the people” as underdogs, excluding corrupt elites and the establishment. In this dynamic, netizens adopt populist “people versus elite” discourses to raise public concerns, defending their civil rights online. The voices of the netizens partly reflect the will of the people. However, once the netizens’ people versus elite discourses are seen as threats to the stability of the state or governing party, they are likely to trigger censorship. Thus, although the people are afforded some power to protest in the internet age, internet technologies also provide a means of control and manipulation for the government, and the affordances contribute to a nuanced form of online censorship.

The “people and netizens” relationship is complicated but is key to understanding online bottom-up populism in China. First, there is a huge overlap between people and netizens, so netizens may partly represent “the people.” However, netizens should not be quickly equated with the people because the country’s population is larger than the number of netizens, and as a group, netizens might also include some elites. Second, because of the semianonymous nature of the internet, the people covered by the internet can be seen as netizens when they express their discontent toward the elite and establishment. In this capacity, netizens function as mediators between “the people” and “the elite.” Hence, netizens can be regarded as populists when they utilize people versus elite discourses to raise public concerns. By further analyzing online bottom-up populism in China with these understandings of the people in mind, we can reveal new forms, dynamics, and consequences of populist contention. This will also widen the lens for understanding populism, expanding the typologies and dynamics of populism worldwide. However, while providing a distinct understanding of Chinese populism, this online bottom-up populism also raises new concerns. For example, to what extent do active netizens genuinely represent “the people,” and to what extent does public opinion represent the general will of “the people” or rather show a narrower opinion of the active online public? These issues need further exploration, not only in China, but across national contexts.

The current study has some limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, the selection of the criteria of academic articles may have influenced the findings because this study has been restricted to articles with “mincui” (populism) in their titles. Second, those populism cases addressed by at least two scholars were selected, which may exclude cases that would be interesting illustrations of populism addressed by only one scholar. Based on this paper, future research can adopt broader criteria to deepen the understanding of the people. Third, future research should explore the gaming of the CCP’s discourse of the people and online bottom-up populist discourse in the name of “the people,” particularly in terms of their interactive dynamics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referees for their constructive comments on improving the quality of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflicts of interest are reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kun He

Kun He is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Media and Journalism Studies, University of Groningen, studying online populism in China. He aims to broaden the understanding of populism by moving from Western democracies to communist settings and from offline to online. He will continue this research as a postdoc, exploring the interactions among human AI, digital technologies, and politics.

Scott A. Eldridge

Scott A. Eldridge II is an Assistant Professor in the Centre for Media and Journalism Studies at the University of Groningen. He researches changing conceptions of journalism, focusing on peripheral actors and journalistic boundaries. He is the author and editor of numerous studies and books on digital journalism, including Online Journalism from the Periphery: Interloper Media and the Journalistic Field (Eldridge, 2018).

Marcel Broersma

Marcel Broersma is Professor and Director of the Centre for Media and Journalism Studies at the University of Groningen. His research focuses on current and historical transformations in and of journalism. He has published widely, with his recent research focusing on shifting patterns of news use, the use of social media, and digital literacy and inclusion.

Notes

1 Where the people and the elite are placed in italics, this indicates the larger concepts being explored; when placed within quotation marks, it refers to a specific usage within the research and within specific populist discourses being studied.

2 Sun Zhigang was a migrant worker in Guangzhou who died in 2003 while being detained under China’s custody and repatriation (C&R) system. This case attracted massive attention on the Chinese internet, leading to the abolition of the C&R system.

3 The Lei Yang case relates to the 2016 death of an environmentalist Lei Yang in Beijing, who was detained on suspicion of soliciting prostitution at a foot parlor. He died because of police brutality, as proven by an independent autopsy.

4 Fei Xiaotong (Citation1988) uses the term “Chinese people” as Zhonghua minzu. This paper adopts the term “Chinese nation” because it highlights the unified feature, which is also in line with President Xi Jinping’s articulation of the Chinese dream “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (Zhonghua minzu weida fuxing).

5 “Causing no harm to their nerves and bones” adopts an ancient phrase used in China to refer to something that causes no physical harm: “shangjing donggu.”

6 According to Guo and Lei (Citation2015), those with a monthly income of less than 3,000 Yuan (around 400 euros) have been ascribed to “the bottom” of society. By this standard, 51.1% of netizens are considered from “the bottom” (The 47th China Statistical Report on Internet Development, 2021). When this income standard is expanded to those who earn less than 8,000 Yuan (about 1,100 euros), 85.2% of netizens fall into this group.

References

- Agamben, G. (2000). Means without end: Notes on politics. University of Minnesota Press.

- Aslanidis, P. (2017). Populism and social movements. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 306–325). Oxford University Press.

- Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and his world. Indiana University Press.

- Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.00184

- Canovan, M. (2005). The people. Polity.

- Chen, L. (2011). Huayu qiangzhan: wangluo mincui zhuyi de chuanboshijian [Taking the vantage place of discourse: The communication practice of online populism]. GuoJi XinWen Jie, 10, 16–21.

- Chen, W. Q. (2014). Chuanmei mincuihua beijing xia de fanzhi yawenhua yanjiu [Anti-intellectual subculture of mass media in the popularized background]. XinWen Yu ChuanBo, 4, 104–113.

- Chen, W. Q. (2016). Dangdai meijie wenhua mincuihua qingxiang yanjiu [A study on the populist tendency of current Chinese media culture]. China Book Publication House.

- Coble, P. M. (2007). China’s “new remembering” of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937–1945. The China Quarterly, 190, 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741007001257s

- De Cleen, B. (2019). The populist political logic and the analysis of the discursive construction of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. In J. Zienkowski & R. Breeze (Eds.), Imagining the peoples of Europe: Populist discourses across the political spectrum (pp. 19–42). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- De Kloet, J., & Chow, Y. F. (2017). Shanzhai culture, dafen art, and copyrights. In K. Iwabuchi, E. Tsai, & C. Berry (Eds.), Routledge handbook of East Asian popular culture (pp. 229–241). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Espejo, P. O. (2017). Populism and the idea of the people. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 607–628). Oxford University Press.

- Fei, X. T. (1988). Plurality and Unity in the configuration of the Chinese People. The Tanner Lectures on Human Values. Lectures delivered at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 15 and 17 November, 1988. Available at https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_resources/documents/a-to-z/f/fei90.pdf (accessed September 29, 2020)

- Gries, P. H. (2004). China’s new nationalism: Pride, politics, and diplomacy. University of California Press.

- Gong, H., & Yang, X. (2010). Digitized parody: The politics of egao in contemporary China. China Information, 24(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X09350249

- Guo, X. A., & Lei, S. (2015). Wangluo mincui zhuyi de sanzhong xushi fangshi jiqi fansi [Three narrative ways of online populism and its reflections]. Theoretical Exploration, 5, 65–69.

- Hariman, R. (2008). Political parody and public culture. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 94(3), 247–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630802210369

- Hauben, M., & Hauben, R. (1997). Netizens: On the history and impact of Usenet and the Internet. IEEE Computer Society Press.

- He, K., Eldridge, S. A., II, & Broersma, M. (2021). Conceptualizing populism: A comparative study between China and liberal democratic countries. International Journal of Communication, 15, 3006–3024. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/16563/3484

- Hofstadter, R. (1963). Anti-intellectualism in American life. Vintage.

- Laclau, E. (2005). On populist reason. Verso.

- Lee, V. (2012, December 8). Robin-hood Chinese New Year’s Gala challenges CCTV. Beijing Today. https://web.archive.org/web/20110718140609/http://bjtoday.ynet.com/article.jsp?oid=46991666

- Li, H. M. (2011). Parody and resistance on the Chinese internet. In D. K. Herold & P. Marolt (Eds.), Online society in China: Creating, celebrating, and instrumentalising the online carnival (pp. 83–100). Routledge.

- Li, L., & Xu, X. (2012). Hulianwang yu mincui zhuyi liuxing [Internet and the popularity of populism]. XianDai ChuanBo, 5, 26–29.

- Liu, X. L. (2017). Mincui zhuyi sichao zai daxuesheng zhong de shentou jiqi zhili celue [The penetration of populist thoughts in college students and its governance strategies]. LiLun YueKan, 10, 103–109.

- Luo, Y. (2014). The Internet and agenda setting in China: The influence of online public opinion on media coverage and government policy. International Journal of Communication, 8(2014), 1289–1312. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/viewFile/2257/1133

- Macpherson, C. B. (1973). Democratic theory: Essays in retrieval. Clarendon Press.

- MacClelland, J. S. (2005). A history of Western political thought. Routledge.

- Mény, Y., & Surel, Y. (2002). The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Y. Mény & Y. Surel (Eds.), Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 1–21). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781403920072_1

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford University Press.

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Ostiguy, P. (2017). A socio-cultural approach. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 74–96). Oxford University Press.

- Perry, E. J. (2015). The populist dream of Chinese democracy. The Journal of Asian Studies, 74(4), 903–915. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002191181500114X

- People’s Daily. (2016). Diba chuzheng Facebook, youbang youhua yaoshuo [The Diba is marching on Facebook, friendly nation has something to say]. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MjM5MjAxNDM4MA==&mid=414189337&idx=1&sn=9bd322d52ca520d47899cda357df1ec4&scene=4#wechat_redirect

- Rawls, J. (2007). Lectures on the history of political philosophy. Harvard University Press.

- Reed, I. A. (2013). Power: Relational, discursive, and performative dimensions. Sociological Theory, 31(3), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275113501792

- Rousseau, J. (2016). A discourse on inequality. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Sartori, G. (1987). The theory of democracy revisited. Chatham House Pub.

- Schroeder, R. (2021). The populist revolt against the West. Comparative Sociology, 20(4), 419–440. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-bja10041

- Shi, Z., & Yang, G. B. (2016). New media empowerment and state-society relations in China. In J. DeLisle, A. Goldstein, & G. Yang (Eds.), The internet, social media, and a changing China (pp. 71–85). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Sun, J. W. (2019). Xiandai renmin gainian de neizai maodun jiqi mincui zhuyi jiangou [The inherent contradiction of the modern concept of “the people” and its populist construction]. Hainan DaXue XueBao, 6, 93–100.

- Sun, W. (2006). Yi dazhong de mingyi: dangqian dazhong chuanmei de wenhua mincui zhuyi qingxiang fenxi [In name of the masses, the analyze cultural populist trendy in contemporary mass media]. XinWen DaXue, 3, 94–101.

- Sun, Y., Graham, T., & Broersma, M. (2021). Informing the government or fostering public debate? How Chinese discussion forums open up spaces for deliberation. Journal of Language and Politics, 20(4), 539–562. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.19104.sun

- Tai, Z. (2015). Networked resistance: Digital populism, online activism, and mass dissent in China. Popular Communication, 13(2), 120–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2015.1021469

- Tao, W. Z. (2009). Hulianwang shang de mincui zhuyi sichao [Populism trend on the internet]. TanSuo Yu ZhengMing, 5, 46–49.

- Weyland, K. (2017). A political-strategic approach. In C. R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, & P. Ostiguy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of populism (pp. 48–72). Oxford University Press.

- Wu, X. T. (2017). Zhongguo gongchandang huayu tixi de lishi kaocha [A historical analysis of the Chinese Communist Party’s discourse system]. Hong GuangJiao, 9, 75–85.

- Xia, Z. M. (2014). “Dongguan saohuang fengbao” zhong de wangluo mincui zhuyi chuanbo shijian [The communicative practice of online populism in the ‘Dongguan anti-pornography storm”]. Contemporary Communication, 4, 51–52.

- Yack, B. (2001). Popular sovereignty and nationalism. Political Theory, 29(4), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591701029004003

- Yang, G. (2009). The power of the Internet in China: Citizen activism online. Columbia University Press.

- Yu, K. P. (1997). Xiandaihua jincheng zhong de mincui zhuyi [Populism in the process of modernization]. ZhanLue Yu GuanLi, 1, 88–96.

- Zhang, L., & Fung, A. (2013). The myth of “shanzhai” culture and the paradox of digital democracy in China. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 14(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2013.801608