Abstract

Mass-produced consumer packages are everyday objects that almost go unnoticed. However, by claiming things such as the essence of femininity or masculinity, they affect us and are co-creators of our reality. Based on visual ethnography, this article traces the representation of gender on mass-produced packaging during a time when male privilege is being challenged and female visual objectification is being questioned. The chosen products all have an intimate relationship with body care and the body’s functions. On some of the packaging, the biological differences between women and men are presented as scientific facts. On other examples, such as perfume packaging, gender is represented as decoupled from the body and part of an enjoyable choice of identity, as multiple, fragmented, and fluid. Such representations conceal power differences by making gender into a matter of consumer choice, while also illustrating the constantly changing nature of gender. Gender and package design are entangled processes that affect and change with each other.

Introduction

From clothing and cars to couches and razors, low-fat products and chocolates to barbecue sauces and spirits, marketers anticipate their buyers’ gender. It is inscribed into packaging and marketing as forms of scripts that guide consumer choices and reproduce gender norms and structures (Oudshoorn, Saetnan, and Lie Citation2002; Akrich Citation1992). Furthermore, divisions between designers and users, production and consumption rely on gender ideologies that generally place men on one side and women on the other (Wajcman Citation2004). In this way, the conventions of design “do” gender.

In this article, I relate the representation of gender on consumer packages in contemporary Sweden to Stuart Hall’s strategies for handling stereotypes (Hall Citation1997). In doing this, I examine how a commercial field can work as a site for questioning stereotypes, as well as reproducing them (Landreth Grau and Zotos Citation2016; McRobbie Citation1997, Citation2002; Friedan Citation1974; O’Connor Citation2005; Catterall et al. Citation2001). Drawing on a combination of actor network theory (Latour Citation1996; Callon Citation1998) and Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity (Butler Citation1990), I treat packages as objects that play an active part in gender performativity. By exploring the ways in which product packages “do” gender, I examine mass-produced consumer packages that in one way or another make unconventional claims, packages that do not in a simple and straightforward way use gender stereotypes. In doing so, I study the agency of materiality for constructing gender. Focusing on how marketing discourse is increasingly enacting gender as fluid, the purpose is to examine how such enactments relate to gender ideology: do they reflect a change in cultural norms, or are they merely a matter of commodifying gender fluidity?

Gender and Design: From Reflecting to Constructing

Many scholars working in the fields of design and gender have taken an interest in the ways in which cultural gender norms are not only reflected but also constructed by objects. Consumer goods are not only the result of cultural beliefs about gender; they also create notions of what is masculine, feminine, and even gender-neutral. Design may be understood as a language, but objects communicate differently than text. Their influence is direct (Kirkham and Attfield Citation1996, 1; Attfield and Kirkham Citation1989). Deploying established conventions for form, shape, colors, words, font, texture, décor, symbolism, signs, size, and layout, products communicate the gender of the intended buyer and/or user (Sanders Citation1996; Lees-Maffei Citation2011; Cockburn and Ormrod 1993). Design gives material form to cultural and gendered norms of desires, activities, spaces, movement, and the body (especially in the form of clothing; see Brandes Citation2008, 190; Lees-Maffei Citation2002; Entwistle and Wilson Citation2001; de Grazia Citation1996; Kirkham 1996; Martinez and Ames Citation1996; Sparke Citation1995; Colomina Citation1992). Gender segmentation is a process that is often added by marketing departments, but objects too are designed to appeal to either men or women (Brunnström Citation2006; Sparke Citation2004; Schwartz Citation1996). Design discourse, however, tends to think of objects as neutral and following fundamental ideas of form and function, rather than as enactments of gender or heteronormativity (Sanders Citation1996). What is more, design that is clearly marketed to boys or girls, men or women not only enacts gender difference – it also reinforces gender as binary (Loxley Citation2007). Recognizing the arbitrariness or changeability in the gendering of design language has worked as resistance to gender ideologies (cf. Garber Citation1992). By showing that the links between, for instance, femininity and the color pink have no basis in nature but are the result of complex representational systems and signifying practices (cf. Hall Citation1997, 26f), it is possible to expose the flawed notion that cultural valuations of femininity have any basis in nature.

As many scholars have argued, there is no such thing as gender-neutral design (Brandes Citation2008, 190). On the contrary, gender neutrality is dependent upon gender conventions, and often involves the subordination of the supposedly feminine as, for instance, in unisex fashion (Arnold Citation2001; Wilson Citation1985). Penny Sparke’s (Citation1995) classic study of the hidden masculine ideals of modernism and its consequent subordination of feminine taste is a powerful dismissal of gender neutrality. Sparke reads modernism’s taste ideals as akin to masculine dominance over femininity. However, from a gender perspective, Sparke has been criticized for reversing modernist dichotomies without undermining them; thus, rather than dispelling the stereotypical associations between the feminine and feelings, the superficial and the irrational, Sparke’s argument reinforces them (Negrin Citation2006).

Actor Network Theory and Packaging as a Market Device

Actor network theory posits the role of objects in enabling social action and the role of material things in the constitution of subjectivities, thus arguing that agency is not only a human capacity (Latour Citation1996). Packages can be understood as “actants,” entities that modify the behavior of other entities, therefore making things happen. Building on this framework, Cochoy and Grandclément-Chaffy (Citation2005) describe how packages are a mediator that change the relationship between the product and the consumer by cutting the consumers’ senses off from the product and making them rely instead on indirect written and visual information about the packages’ contents (cf. Hawkins Citation2013). In some instances, packages make aspects of their contents visible to us that we cannot perceive by looking, touching, tasting, or smelling (for example, food’s nutritional information). Packages help us to make decisions as consumers (Cochoy Citation2004, 224, Citation2007).

Studies of packaging that use actor network theory approach packages as “market devices” (Cochoy Citation2004, Citation2007; Hawkins Citation2013). Market devices are those actors that play a substantial part in the performative making of markets (Callon Citation1998; Callon, Millo, and Muniesa Citation2007). The work done by market devices is referred to as “qualification,” which involves connecting commercial objects with cultural and social categories, including “qualifying” products as well as consumers (Fuentes and Fuentes Citation2017). Packages actively qualify their contents, for instance by indicating how they differ from other similar products. Their different faces make room for branding strategies that performatively co-create a market for their products, along with the simultaneous qualification and co-creation of consumer identities for this market. Thus, as market devices, packages have the capacity to make others act and contribute to shaping consumer practices, identities, roles, abilities, and dispositions. The term “market device” refers to the material and discursive assemblages that intervene in the construction of markets (Callon, Millo, and Muniesa Citation2007; Hawkins Citation2013; Cochoy et al. Citation2017; Fuentes and Fuentes Citation2017). This means that consumer choice is not made by a choosing individual but instead is shaped by market devices. Devices shape consumer practices and product markets.

Packaging is actively involved in producing its contents, consumption, and consumers. Applying this framework to the study of gender illuminates how the gendering of objects is part of qualifying them as products designed for a specific market. That qualification is a dual process. The gendering of goods is the result of active production that involves the identification and valuation of goods and consumers’ qualities, and a process that is subject to continual qualification and requalification (Hawkins Citation2013). In shaping a market for fragrances “for her,” packages become qualification devices but simultaneously help to form the subjectivities of the people who use them (cf. Nixon Citation2013; DuGay 2004). Goods qualify consumers, create market segments, and inform the identity of the consumer who is interested in gender fluidity. My interest lies in the simultaneous making of markets and gender, and the part that is played by commercial goods in this process. I am concerned with the way in which products “do” gender and the active part played by goods in gender performativity (Butler Citation1990).

The Role of Packaging in Gender Performativity

To understand how market devices and qualification relate not just to a consumer segment but also to the cultural understanding of gender, I turn to gender performativity. Masculinity and femininity can be understood as cultural conventions or, as per Butler (Citation1990, Citation1993, Citation1997), as performative enactments of gender that have effects. For Butler, gender is not the expression of an inner identity – rather, it is performative. The notion of “woman,” for instance, cannot be understood as separate from the way in which it is staged and performed. Gender is not an attribute or an essential property of a subject, but “a kind of becoming or activity … an incessant and repeated action of some sort” (Butler Citation1990, 112). Gender identity is the result not of physical differences but of complex discursive practices in which gender, sexuality, and desire are coproduced. Building on speech act theory, Butler conceives gender as a set of performative citational practices. They reproduce discourse but can also work subversively. In this sense, gender both enables and disciplines subjects and their performances – it is essentially a citation of all previous performances of gender, an imitation of itself, an idealized norm. Every citation of gender, even on a package, allows for a change, or a slip, in the way gender is enacted.

Packages do not only ask us to choose between different products in terms of contents. By telling us whether the contents are “for her,” “for him,” perhaps unisex, or have no gender at all, packages perform gender. By extension, they not only provide scripts for practices of consumption but also take an active part in the performativity of gender. By saying “for her,” packages claim to express or explain the contents – but this is not so. By saying “for her,” the contents of a fragrance bottle become feminine, and construct women as a consumer group that like and are best represented by certain scents and all that they stand for. Along similar lines, packaging targeted at women is not pink because women by nature like pink, but because the color pink creates an effect that links pink with femininity. Designed goods are necessary props in an ongoing iteration of an unstable gender norm.

Visual Ethnography in Stores

To address the wider context through which specific consumer products and packages become understandable, it is not enough to look only at the objects. Combining visual analysis with visual ethnography (Wagner Citation2015; Sturken and Cartwright Citation2001) makes it possible not only to read packages as texts but also to consider them in relation to wider social and cultural experiences (CitationPink 2007). Designed objects do not have definite meanings in and of themselves, but represent the power relations, methods, and processes through which people make sense of them (Partington Citation1996).

Packages are everyday objects that greet consumers on the shelves of stores, which are themselves sites of cultural production and social interaction and can be read as “cultural texts” (Pink Citation2007, 2). The social rules of commerce are far from equal, and stores may be seen as interfaces that organize the interactions between producer and consumer in unequal and asymmetrical ways (Lury Citation2004). The terms of the interactions are dictated by the producers, but store spaces might also be seen as contested, wherein meanings are negotiated (Hall Citation1997).

The fieldwork for this article was conducted between 2009 and 2013, during which time the Swedish mass market was scanned for “new” or significant expressions of gender. I observed everyday groceries, pharmaceutical products, and perfumes in mainstream, mass-market stores. I also conducted in-depth interviews with shop assistants and conducted walk-along interviews with consumers (Petersson McIntyre Citation2013b). This article focuses on packages for pharmaceutical products and perfumes because these product categories are two of the earliest forms of packaging and have influenced many others – including each other (Hine Citation1997, 4, 34–6). They are different because pharmaceutical packages follow strict regulations for package design that prohibit marketing messages (Brunnström & Wagner Citation2015). Non-prescription products sold in pharmacies are, however, free to include marketing on their packaging. Perfume packaging is unregulated and often takes inspiration from medical bottles, but depends on imagery related to glamour, sexuality, and seduction (Classen et al. Citation1994; cf. Kjellmer Citation2009).

Strategies for Handling Stereotypes

This article adopts Hall’s (Citation1997) post-structuralist methods of visual analysis and representational critique in order to analyze the visual content of packages. Hall presents three possible ways to respond to stereotypes. The first strategy involves reversing or transforming the stereotype into something good and/or powerful. The second strategy involves replacing negative stereotypes with positive ones (for example, “black is beautiful”). The third strategy questions a stereotype from the inside by using its own symbolism to destabilize it.

In the sections that follow, I discuss and analyze the packaging of four different product categories: feminine hygiene articles, incontinence protection, sex toys, and perfume. The products in these categories all have an intimate relationship with body care and function, and work at the intersection of consumption and cultural understandings of gender via the body’s needs and its pleasures. They suggest appropriate ways of protecting and presenting the body in social situations, discretion with bodily function, and bodily empowerment. As I will show, gender processes and the handling of stereotypes are constantly at stake in drawing and crossing these boundaries.

Tampons, Incontinence Protection, and Sex Toys

When walking around stores, I found that many packages for makeup and feminine hygiene articles were decorated with illustrations and images of women with long eyelashes and enlarged lips. The packages for Libresse pads had decorative, colorful graphics resembling fashion illustrations (). Their tampons were packaged in sleeves reminiscent of lipstick tubes, a far cry from the brown paper signaling discretion for such products during the first half of the twentieth century (). Enlisting the visual language of fashion to express feminine pride, these packages can be interpreted as an attempt to turn the culture of shame surrounding menstruation into a visual language of female empowerment (cf. de Waal Malefyt and McCabe Citation2016). In terms of Hall’s (Citation1997) strategies, this can be seen as an attempt to reverse stereotypes by celebrating femininity and filling the feminine décor with empowering messages of womanhood.

Difference and Sameness

TENA’s products for incontinence, which are offered in a gender-binary model that communicates “different but equal,” suggest Hall’s (Citation1997) second strategy – that is, of replacing negative stereotypes with positive ones – in how TENA offers products adapted to the special needs of different groups (). The strategy is risky since replacing a negative stereotype with a positive one often retains the stereotype. For example, even though absorbency was in the foreground of both the men’s and women’s packaging, masculinity was related to performance and femininity to discretion. During the period in which the fieldwork was conducted, the men’s packages were dark blue and adorned with the text “Maxx Protection Technology.” Graphics illustrated the product’s technology and its ability to perform. On the women’s package, the text “New feminine shape” appeared, punctuated by a butterfly and decorated with organic loops. An association was established between the product’s “shape” and the stripped, well-formed female body that covered the pack. The women’s packaging played not upon product performance, but upon enjoyment, beauty, and discretion. In 2018 the packages were updated, and the men’s packaging has now been given a human figure illustration in which the product’s padding amplifies the appearance of the penis, thus hinting at its ability to increase the wearer’s masculinity. The message is that incontinence protection helps men to maintain control – and thus to retain their masculinity – in social situations. For women, incontinence products help to maintain an attractive, pleasing femininity in spite of the product (cf. Schwartz Citation1996).

Pleasure and Functionality

My third example is the Belladot sex toys sold in Swedish pharmacies (). Launched in 2011, Belladot’s retro-inspired products were instantly noticed and awarded for their creative forms. The pastel-colored products have names that play on 1950s nostalgia. These designs are intended to normalize the use of sex toys, a strategy that builds a market for the products at the same time as it shapes the public’s view of such products (cf. Comella Citation2017; Wilner and Dinnin Huff Citation2016).

Figure 3 Belladot sex toys. (a) Belladot Ingemar, penis pump; (b) Belladot Sofia, vibrating dildo. Courtesy of Belladot.

In an example of packaging functioning as an educator, graphic symbols indicate whether the content is intended for women, men, or both (Cochoy Citation2008). The emphasis of TENA’s packaging on male potency and female pleasure is repeated here through text, color, and font. In the sales blurbs on Belladot’s website, the Sofia dildo and Ingmar erection pump are described as follows:

Belladot Sofia is a soft and flexible dildo with a silky-smooth matte texture. Sofia’s speciality is the raised, wavy pattern that circles all the way down the shaft. The wavy texture makes the feeling more intense and pleasurable. The powerful vibrator at the top is easily operated with a multispeed control. This vibrating dildo is great for shower-time play. (www.belladot.se)

Belladot Ingemar is a high-capacity, powerful penis pump. May be used for pleasure and to help achieve firmer erections. Comfortable grip and easy to pump. The cylinder’s soft rubber ring fits securely around the penis and creates a suction vacuum. It includes a built-in ruler so you can easily measure growth. A quick-release function allows you to easily adjust the pressure. (www.belladot.se)

Like TENA, Belladot presents the idea of different but equal products and communicates this with cultural stereotypes of femininity and masculinity, in this case concerning performance and pleasure. While the description of Ingemar enlists the language of a professional care expert, that used to describe Sofia suggests a sexual partner. Sofia is described as pleasing in itself, with a “silky surface” and a shape intended to create enjoyment. Agency is given to the human user and Sofia is described in passive terms. By contrast, the description of Ingemar is masculine. It does something; it is active and powerful, a high-capacity aid. Thus, the products reiterate the conventions by which consumption by women is made meaningful in relation to pleasure and by men is made meaningful in relation to function (e.g., sexual performance). In fact, pleasure and self-pleasure are commonly used imaginaries to describe the relationship between women and consumer goods (Felski Citation1995). Belladot reproduce this convention, but it is also possible to interpret the description of Sofia in more open terms of women’s non-heterosexual pleasure; given the passive description of Sofia, its female users become the active sexual party.

Representing Fragrance in Gender Terms

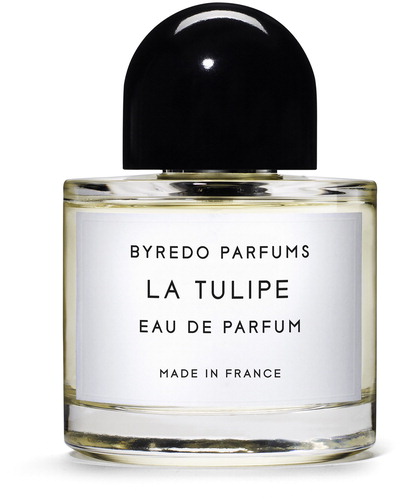

Many fragrance brands that emphasize the artisanal property of perfumery resist gender distinction. Instead of creating meaning around gendered stereotypes of attraction and sexuality, they build messages around memories, fleeting sensations, moods, and locations. To accommodate the diversity of these possibilities, the packaging is often simple, with labels related to craft aesthetics (cf. Hemme Citation2010). For instance, the Swedish brand Byredo packages its scent in stylish bottles with no visible markings of gender (). In interviews, brand founder Ben Gorham argues that scents have no gender, but marketers have invented them to facilitate the sale of fragrances by segment Dagens nyheter, October 3rd 2010.

The lack of gender segmentation is used as a way to express authenticity – but avoiding gendered expressions on labels and packages does not mean that consumers will stop, or are intended to stop, interpreting the goods in gendered terms. Knowledgeable, experienced perfume consumers, for example, can easily determine from the list of ingredients on a perfume bottle whether the scent is meant for women or men (Petersson McIntyre Citation2013a). Just as Sparke (Citation1995) argues, what seems like gender neutrality often involves the subordination of femininity. Thus, it is important to pay attention to underlying messages which may serve to increase the status of a product by associating it with masculinity.

Universalizing Femininity

Agonist, another Swedish fragrance brand, has taken craft perfumery a step further. The scent Kallocain was launched in the late 2000s and packaged in hand-blown bottles designed by artist Åsa Jungnelius (). The bottle references surrealism and Dali’s The Persistence of Memory in its conflict between the hard, black base and the soft, moving bottle. The bottle melts, turns, and changes, as though demonstrating a frozen movement. The mouth of the bottle resembles a nipple and the tassel is like that of a striptease dancer. Agonist’s scent was not launched as a women’s or men’s fragrance, which makes it particularly interesting; in Agonist’s version, the feminine becomes universal, thus challenging conventional stereotypes.

Playing with Ambivalence

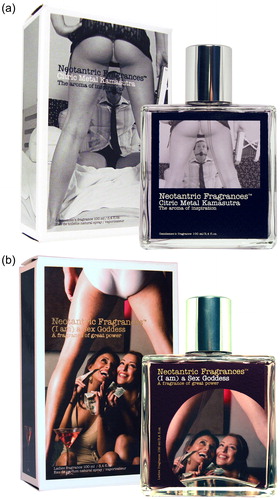

Neotantric’s fragrances, also from Sweden, introduced a third way of playing with sexuality and gender conventions. Unlike Byredo and Agonist, Neotantric has retained the division of gender segments, only to play with them in a way that often exhibits the strategy of reversing stereotypes (Hall Citation1997). Neotantric’s packaging and advertisements for men’s and women’s fragrances show women taking sexual, sometimes sadistic control over men (). The packaging for the men’s fragrance shows a man tied and gagged. In front of him stands a woman with a camera in her hand. The image forges a connection between daring to live out secret sexual fantasies and daring to consume the product. Meanwhile, the camera in the hand of the woman can be perceived as playing with the male gaze (Mulvey [Citation1975] 1992), a term coined to conceptualize the objectification of women’s bodies and how women who internalize the gaze make it their own and thereby objectify themselves. By standing in front of the camera instead of behind it, the image might be interpreted as portraying a feminist avenger who achieves redress by treating men as they have treated women. As such, the image reverses a familiar power relationship and overthrows it. At the same time, there are also elements in the image that repeat conventions of the visual representation of men and women. The woman’s naked buttocks, accentuated with a thong, are arranged to be gazed upon, and the man’s head can be seen as a penis about to penetrate her. His gaze is directed upward, both to her face in sexual subservience and into her vagina. The images are thus ambiguous and without any definite meaning.

Figure 6 Neotantric fragrances. (a) Citric Metal Kamasutra; (b) (I am) a Sex Goddess. Courtesy of Neotantric.

The packaging for a Neotantric women’s fragrance is less ambiguous – at least initially. It shows two women admiring a male stripper and trying to tip him. This theme can also be interpreted as daring in the matters of gender and sexuality, as well as consumption, for it is a clear example of turning stereotypes and using irony. Why is the packaging for the men’s fragrance more complicated than that of the women’s? In the case of the women’s packaging, stereotypes holding that men admire female strippers can easily be interpreted as reversed, thus addressing female consumers with a comical, feminist, and pop culture approach about taking power over sexual representations and questioning who is looking at whom. But a second look reveals that the stripper is, perhaps, a woman (cf. Schroeder and Borgerson Citation2003). This ambiguity suggests that a radical image of a woman who completely takes control perhaps produces the man in an overly subordinate position, thereby making the marketed product less desirable among consumers (Cheong and Kaur Citation2015). Such ambiguity and difficulty in establishing a definite interpretation may serve as both a way of producing a new role for men with sexy, active women while positioning them as the sexual subjects. We can no longer be sure of who is looking at whom, and in the end, perhaps gender segments – in this case, of women’s and men’s fragrances – become obsolete.

Gender as Multiplicity and Choice

The approach to gender and sexuality in the perfume market is perhaps best characterized as a choice in terms of both femininity and masculinity. People are presented as individual consumers who select from a range of perfumes and packaging on the basis of mood, feeling, or identity (Petersson McIntyre Citation2013b). Such a discourse bears similarities to what Kniazeva and Belk (Citation2007) refer to as the grand postmodern marketplace myth of an empowered and ennobled consumer (cf. Cody and Lawlor Citation2011). The abundance of femininity available on the market (Partington Citation1996) suggests not only that gender identities are diverse and can be understood in different ways, but also that consumers are free from normative gender identities.

The packaging for the scent series Fragrance Library from Make Up Store clearly illustrates the idea of gender as choice. The series contains 11 fragrances, each of which is described in the form of personal ads. In “Your Valentine,” the text speaks to the romantic, passive woman who takes care of herself while waiting to be seduced. The angular bottle made of thick black glass has squiggly pink text that reads:

I am sensitive and feminine. I spend my days in the tub, reading books or taking long walks in the woods. Looking for someone who likes genuine conversations in front of the fireplace and likes to take me out to dinner. I love chocolate and red roses.

This romantic woman is just one of many possible female identities. One of the other scents in the series, “Champion Deluxe,” is described as lively and sporty. The text on its bottle is printed in capitalized, Roman letters. Although completely different, it still makes a feminine address. The variety of perfumes, bottles, and packaging portrays feminine, masculine, and unisex as constantly shifting; it is a vision of identity as optional and of the consumer as someone who chooses goods to express his or her identity. By extension, that vision can itself be understood as performative (Partington Citation1996; Cronin Citation2000).

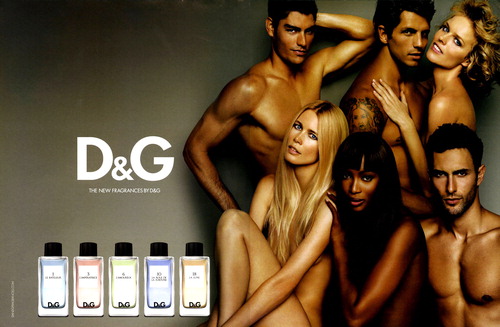

Decoupling and Recoupling Gender and Bodies

A final example comes from Dolce & Gabbana’s fragrance series Anthology (). When it was launched in 2009, it consisted of five identical angular bottles, all with labels bearing a home-printed look. The scents were not obviously for women, men, or even unisex, and can thus be seen as an attempt to launch a product that transgresses gender segments. Yet they nevertheless used a visual language relying on sexual desire. Each different scent was named after a tarot card and was represented in the accompanying ads by six supermodels – three men and three women – each paired with a different bottle. In some of the ads, a bottle was paired with two models to indicate that the scent had a dual personality and a dual gender – and of course that both men and women could use the fragrance. The marketing was built on dissociating gender from the body and portraying gender identity as a characteristic that consumers may choose according to their personality. However, in 2013 the series was expanded to eight bottles and, on the company’s website, four were listed as “pour femme” and four “pour homme.” What happened to subverting gender roles?

Conclusion

Packaging enacts, or does, gender in many different ways. It helps to produce a market for gendered goods by enacting gender in particular ways. It qualifies products in gendered terms, and simultaneously creates a consumer group for its contents. This article has identified eight different ways of representing gender. The first, building on Libresse’s tampon and pad packages, reverses stereotypes by upvaluing the feminine yet also by clearly connecting femininity and pleasure, a convention that often appears in marketing for women. The second, as exemplified by TENA, represents gender-segmented incontinence protection as a response to the cultural norms of the masculine as universal, but a closer look reveals a visual imagery strongly rooted in conventional ways of representing gender. The third, represented by Belladot’s sex toys, also makes a clear connection between femininity and pleasure, and between masculinity and (sexual) performance – yet also between feminine sexuality and activity (as opposed to passivity), thus also challenging conventional associations between femininity and pleasure. The remaining five examples all come from perfume. In the fourth example, Byredo, the craft of perfumery is stressed and set in opposition to gendered marketing. Nevertheless, the masculine is reasserted as neutral, even though the brand superficially appears to stand above gender conventions: a cultural connection is made between masculinity and neutrality, thereby upvaluing masculinity at the expense of femininity. The fifth example, Agonist, associates femininity with the universal, thereby challenging these conventions. The sixth example, Neotantric fragrances, plays with representations and creates uncertainty, ambivalence, and ambiguity, yet nonetheless makes connections to conventional ways of representing gender. The seventh example, from Make Up Store, presents gender as choice, thereby hiding gender identities as something normative or structural. Lastly, Dolce & Gabbana’s Anthology at first appeared to be gender-neutral, yet later reverted to affirming gendered connections between consumers and products via its packaging and marketing.

These different ways of representing gender identities on consumer packaging are neither an expression of dissolution of gender categories through which individuals choose identities via creative play (Firat and Venkatesh Citation1995; Patterson and Elliott Citation2002) nor an example of Baudrillardian illusive choices (Baudrillard Citation1983; Bauman Citation1988, Citation1992; Giddens Citation1991). Although I follow up on the critique of applications of postmodernism that points to the normative dimensions of consumer choice (Kniazeva and Belk Citation2007; Schroeder and Zwick Citation2004), I also leave room for a more open interpretation that allows for an understanding of gendered packaging as neither a simple repetition of conventional gender roles nor an opportunity for their dissolution. By drawing on the work of Butler (Citation1990, Citation1993, Citation1997) I have interpreted the flow of gender representations as expressing the absence of any putative, inner, stable identities, while simultaneously noting the normative dimension inherent in consumer culture. Packaging, like gender, is performative and relates to wider cultural processes.

Consumer choice is at the heart of branding strategies. Representing gender identity on consumer packaging in ways that question or challenge stereotypes must also be related to market making and attempts to catch the eye of the consumer on a shelf packed with many similar products. The qualification of products does not only address consumer types – it increasingly incorporates contemporary understandings of gender identity as fluid in its call for consumers’ attention. When marketing says that our personalities can be represented by many different genders, it also asks us to include the daily choice of gender in our consumption. Marketing devices make a convincing and seductive attempt at persuading us that gender is nothing but a matter of consumer choice – and not at all a serious matter.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to the two anonymous reviewers whose comments helped to develop the article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Magdalena Petersson McIntyre

Magdalena Petersson McIntyre holds a Ph.D. in Ethnology and is Associate Professor at the Centre for Consumer Research, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. She has previously published in English on perfume packaging in Culture Unbound (2013), on aesthetic labor and passion in the Journal of Cultural Economy (2014), on challenging the masculine norm in a Swedish leisure boat concept in International Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship (2015), and on gender and work clothes in Fashion Practice (2016). Her research interests lies within consumption, fashion, design, and gender. She co-edited the book Digitalizing Consumption (Routledge, 2017) and is currently researching the commercialization of gender equality.[email protected]

References

- Akrich, Madeleine. 1992. “The Description of Technical Objects.” In Wiebe Bijker & John Law (eds.) Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Arnold, Rebecca 2001. Fashion, Desire and Anxiety. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press.

- Attfield, Judy, and Pat Kirkham. 1989. A View from the Interior: Feminism, Women and Design. London: The Women’s Press.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1983. Simulation. New York: Semiotext(e).

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1988. Freedom. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 1992. Intimations of Post-Modernity. London: Routledge.

- Brandes, Uta. 2008. “Gender Design.” In Design Dictionary: Perspectives on Design Terminology, edited by Michael Erlhoff and Tim Marshall, 189–190. Basel: Birkhäuser.

- Brunnström, Lasse. 2006. Telefonen en designhistoria. Stockholm: Atlantis.

- Brunnström, Lasse, and Karin Wagner (eds.). 2015. Den ohållbara förpackningen. Stockholm: Balkong Förlag.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 1997. Excitable Speech. New York: Routledge.

- Callon, Michel (ed.). 1998. The Laws of the Market. London: Blackwell.

- Callon, Michel, Yuval Millo, and Fabian Muniesa. 2007. “An Introduction to Market Devices.” Sociological Review 55 (2): 1–12.

- Catterall, Miriam, Pauline McLaran, and Lorna Stevens (eds.). 2001. Marketing and Feminism. London: Routledge.

- Cheong, Huey Fen, and Surinderpal Kaur. 2015. “Legitimizing Male Grooming through Packaging Discourse: A Linguistic Analysis.” Social Semiotics 25 (3): 364–385.

- Classen, Constance, David Howes, and Anthony Synnott. 1994. Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell. London: Routledge.

- Cochoy, Franck. 2004. “Is the Modern Consumer a Buridan’s Donkey?” In Elusive Consumption, edited by Karin M. Ekström, and Helene Brembeck, 205–227. Oxford: Berg.

- Cochoy, Franck. 2007. “A Sociology of Market-Things: On Tending the Garden of Choices in Mass Retailing.” The Sociological Review 55 (2_suppl) 109–129.

- Cochoy, Franck. 2008. “From Tasting to Testing, Teasing, Teaching: Packaging, or How to Taste Products with One’s Heart and Mind.” Paper presented at the Annual International Working Conference on Sustainable Consumption and Alternative AgriFood Systems, Arlon, May 28–30.

- Cochoy, Franck, and Catherine Grandclément-Chaffy. 2005. “Publicizing Goldilocks’ Choice at the Supermarket: The Political Work of Shopping Packs, Carts and Talk.” In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, 109–129. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cochoy, Franck, Johan Hagberg, Magdalena Petersson McIntyre, and Niklas Sörum (eds.). 2017. Digitalizing Consumption: How Devices Shapes Consumer Culture. London: Routledge.

- Cockburn, Cynthia, and S. Ormrod. 1993. Gender and Technology in the Making. London: Sage.

- Cody, Kevina, and Katrina Lawlor. 2011. “On the Borderline: Exploring Liminal Consumption and the Negotiation of Threshold Selves.” Marketing Theory 11 (2): 207–228.

- Colomina, Beatriz (ed.). 1992. Sexuality and Space. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Comella, Lynn. 2017. Vibrator Nation. London: Duke University Press.

- Cronin, Anne M. 2000. Advertising and Consumer Citizenship. London: Routledge.

- de Grazia, Victoria. (ed.). 1996. The Sex of Things. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- de Waal Malefyt, Timothy, and Maryann McCabe. 2016. “Women’s Bodies, Menstruation and Parketing ‘Protection’: Interpreting a Paradox of Gendered Discourses in Consumer Practices and Advertising Campaigns.” Consumption, Markets and Culture 19 (6): 555–575.

- Entwistle, Joanne, and Elizabeth Wilson. 2001. Body Dressing. Oxford: Berg.

- Felski, Rita. 1995. The Gender of Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Firat, Fuat, and Alladi Venkatesh. 1995. “Liberatory Postmodernism and the Reenchantment of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Research 22:239–267.

- Friedan, Betty. 1974. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Dell.

- Fuentes, Christian, and Maria Fuentes. 2017. “Making a Market for Alternatives.” Journal of Marketing Management. 33 (7–8): 529–555.

- Garber, Marjorie. 1992. Vested Interests. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hall, Stuart, (ed.). 1997. Representation. London: Sage.

- Hawkins, Gay. 2013. “The Performativity of Food Packaging: Market Devices, Waste Crises and Recycling.” The Sociological Review 69 (S2): 66–83.

- Hemme, Dorothee. 2010. “Harnessing Daydreams: A Library of Fragrant Phantasies.” Ethnologia Europea 40 (1):5–18.

- Hine, Thomas. 1997. The Total Package. London: Little, Brown.

- Kirkham, Pat (ed.). 1996. The Gendered Object. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kjellmer, Viveka. 2009. Doft i bild: Om bilden som kommunikatör i parfymannonsens värld. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

- Kniazeva, Maria, and Russell W. Belk. 2007. “Packaging as Vehicle for Mythologizing the Brand.” Consumption Markets & Culture 10 (1): 51–69.

- Landreth Grau, Stacy, and Yorgos C. Zotos. 2016. “Gender Stereotypes in Advertising: A Review of Current Research.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (5): 761–770.

- Latour, Bruno. 1996. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt 47 (4): 369–381.

- Lees-Maffei, Grace. 2002. “Men, Motors, Markets and Women.” In Autopia: Cars and Culture, edited by Stephen Wollen, 363–370. London: Reaktion Books.

- Lees-Maffei, Grace (ed.). 2011. Writing Design: Words and Objects. Oxford: Berg.

- Loxley, James. 2007. Performativity. London: Routledge.

- Lury, Celia. 2004. Brands. New York: Routledge.

- Martinez, Katherine A., and Kenneth L. Ames. 1996. The Material Culture of Gender: The Gender of Material Culture. Hanover and London: University Press of New England.

- McRobbie, Angela. 1997. “Bridging the Gap: Feminism, Fashion, and Consumption.” Feminist Review 55: 73–89.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2002. “Fashion Culture: Creative work, Female Individualization.” Feminist Review 71: 52–62.

- Mort, Frank. 1996. Cultures of Consumption: Masculinities and Social Spaces in Late Twentieth-Century Britain. London: Routledge.

- Mulvey, Laura. (1975) 1992. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In The Sexual Subject: A Screen Reader in Sexuality, edited by Mandy Merck, 22–34. London and New York: Routledge.

- Negrin, Llwellyn. 2006. “Ornament and the Feminine.” Feminist Theory 7 (2):209–235.

- Nixon, Sean. 2013. Hard Sell. Manchester: Palgrave MacMillan.

- O’Connor, Kaori. 2005. “The Other Half: The Material Culture of New Fibres.” In Clothing as Material Culture, edited by Susanne Küchler and Daniel Miller, 41–60. Oxford: Berg.

- Oudshoorn, Nelly, Ann Rudinow Saetnan, and Merete Lie. 2002. “On Gender and Things: Reflections on an Exhibition on Gendered Artifacts.” Women’s Studies International Forum 25(4): 471–483.

- Partington, Angela. 1996. “Perfume, Pleasure and Post-Modernity.” In The Gendered Object, edited by Pat Kirkham, 204–218. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Patterson, Maurice, and Richard Elliott. 2002. “Negotiating Masculinities: Advertising and the Inversion of the Male Gaze.” Consumption, Markets and Culture 5 (3): 231–246.

- Petersson McIntyre, Magdalena. 2013a. “Feminine Choice and Masculine Needs: Gender and Perfume Packaging.” In Making Sense of Consumption, edited by Lena Hansson, Ulrika Holmberg, and Helene Brembeck, 153–166. Göteborg: University of Gothenburg.

- Petersson McIntyre, Magdalena. 2013b. “Perfume Packaging, Seduction, and Gender.” Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research 5: 291–311.

- Pink, Sarah (2007). Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research (2., [rev. and updated] ed.). London: SAGE.

- Sanders, Joel. (ed.). 1996. Stud: Architectures of Masculinity. Princeton: Princeton University.

- Schroeder, Jonathan, and Janet Borgerson. 2003. “Dark Desires: Fetishism, Ontology and Representation in Contemporary Advertising.” In Sex in Advertising: Perspectives on the Erotic Appeal, edited by Tom Reichert and Jacqueline Lambiase, 65–87. Lambiase, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Schroeder, Jonathan, and Detlev Zwick. 2004. “Mirrors of Masculinity: Representation and Identity in Advertising Images.” Consumption Markets & Culture 7 (1): 21–52.

- Schwartz, Hillel. 1996. “Hearing Aids: Sweet Nothings, or an Ear for an Ear.” In The Gendered Object, edited by Pat Kirkham, 43–59. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Sparke, Penny. 1995. As Long as It Is Pink: The Sexual Politics of Taste. London: Rivers Oram Press.

- Sparke, Penny. 2004. An Introduction to Design and Culture: 1900 to the Present. London: Routledge.

- Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. 2001. Practices of Looking. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wagner, Karin. 2015. “Reading Packages: Social Semiotics on the Shelf.” Visual Communication 14 (2): 193–220.

- Wajcman, Judy. 2004. TechnoFeminism. Cambridge: Polity Press

- Wilner, Sarah, and Aimee Dinnin Huff. 2016. “Objects of Desire: The Role of Product Design in Revising Contested Cultural Meanings.” Journal of Marketing Management. 33 (3–4): 244–271.

- Wilson, Elizabeth. 1985. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. London: Virago.