Abstract

Addressing the current unsustainability of socio-ecological-technological systems is urgently required. Unsustainability has been associated with the anthropocentric cultures of human societies that focus on their own needs while ignoring and belittling the needs of other species and natural systems. Design, including collaborative and participatory design (C&PD), is one of the multiple ways through which humans build solutions to satisfy their needs and wants in an anthropocentric manner. Through an integrative literature review of C&PD and a bioinclusive ethic (one of the non-anthropocentric frameworks in environmental ethics), this paper – a revised and expanded version of a conference paper previously published in Design Journal (2019) – develops a conceptual framework for bioinclusive C&PD rooted in a non-anthropocentric values base. It outlines twelve key principles for bioinclusive C&PD and proposes six avenues for further research.

1. Introduction: Transformation Imperative and Design

Socio-technical-ecological systems need to be urgently transformed to achieve sustainability. Among the various causes of the crises, some research (e.g. Ceballos et al. Citation2015; Ripple et al. Citation2017; Zylstra et al. Citation2014) highlights the strong link between ecological degradation and anthropocentric cultures. Anthropocentric societies tend to focus on their own needs while ignoring or belittling the needs of other species and natural systems (Hajjar Leib Citation2011; Kotzé Citation2014). This significantly contributes to overuse of natural resources, destruction of natural habitats, and human-caused climate change. Therefore, sustainability transformations require a shift from the anthropocentric (particularly Western) values base towards a non-anthropocentric values base that considers and supports the needs of nonhumans.

The anthropocentric values base also strongly manifest in the dominant discourse and practice of design. Design, as its formalization as a profession during the Industrial Revolution, has focused on the satisfaction of human needs and desires, first through technology-driven and then through human-centered practices (Ceschin and Gaziulusoy Citation2020). Starting from the second half of the twentieth century, stakeholder participation in design processes further supported satisfaction of human needs and wants (Cross Citation1972; Lee Citation2008). The emerging participatory approaches strived to include and actively involve stakeholders, especially future users, as design partners or co-designers (Hyysalo et al. Citation2014; Simonsen and Robertson Citation2012). Over time, these approaches evolved and diversified, creating nuanced categories – such as co-design, participatory design, participatory innovation – each with it’s own scholarly and practice communities, aiming to address different aspects of participation. Despite this diversification, the dominant anthropocentric values base remained. Therefore, in this article, we focus on the broad spectrum of participatory approaches which actively involve stakeholders as design partners which we refer to as collaborative and participatory design (C&PD).

C&PD processes tend to focus on the needs of humans and human-made systems and, typically, leave out considerations about natural nonhumans. However, sustainability transformations would require C&PD to become inclusive of and attentive to the needs of nonhumans (Abson et al. Citation2017; Ives et al. Citation2018). Nonhuman perspectives could be included in C&PD, as C&PD encourages and supports the representation and participation of different perspectives. Early work in this direction has already emerged, and we present it in sections 3.3. and 3.4. However, as such work is new and emerging; a solid theoretical ground onto which nature-inclusive C&PD could be built has not yet been established. Such a theoretical ground would need to be based in both environmental ethics and C&PD: to grasp non-anthropocentric perspectives and re-assess and transform C&PD constructs. In our research, we make an attempt to create such theoretical ground by critically analyzing C&PD through the lens of a bioinclusive ethic, one of the non-anthropocentric environmental ethical frameworks. We presented our early considerations about the implication of the bioinclusive ethics on C&PD at the European Academy of Design Conference 2019, proceedings of which were published as a supplement of the Design Journal (Veselova and Gaziulusoy Citation2019). Since then, we have significantly deepened our perspectives. This article presents a succinct overview of C&PD, an expanded perspective on the bioinclusive ethic, and some updated and mostly new considerations on bioinclusive C&PD. The next section presents our methodology and findings. In Section 3, we present a conceptual framework for bioinclusive C&PD and identify questions for further research.

2. An Integrative Conceptual Framework for Bioinclusive C&PD

2.1. Methodology

We conducted a two-part, systematic, integrative literature review (Booth, Sutton, and Papaioannou Citation2016; Torraco Citation2016) with the following research questions: (a) What is C&PD and its key characteristics? and (b) What is a bioinclusive ethic and its key characteristics? First, we found 235 resources by expert suggestions, bibliographic and citation searches, and twenty-two search terms in the Academic Search Elite database. We selected 121 of them to review in detail based on their ability to contribute knowledge for answering the research questions and the credibility of the source. We reviewed the selected resources qualitatively via content analysis and then deepened the findings on the bioinclusive ethic with a brief review of environmental ethics, conducted through using The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Brennan and Lo Citation2016) and two introductory books (Boylan Citation2013; Sandler Citation2018). Finally, we integrated insights about C&PD and the bioinclusive ethic, elaborated the potential implications of the ethic for C&PD and developed the proposed conceptual framework for bioinclusive C&PD.

2.2. C&PD

Typically, there are two main types of participants in design processes: expert designers and stakeholders. Expert designers are professionally trained in design and accountable for the processes and approaches used (Bødker, Kensing, and Simonsen Citation2011; Manzini Citation2015). Defining with clarity who and what counts as a stakeholder is harder and, in most cases, contextual. A stakeholder, in general understanding, is “one who is involved in or affected by a course of action.” In design, the definitions and terms used to identify a stakeholder range from passive terms – such as user, informant or implicated actor (Clarke and Star Citation2008; Zhang and Dong Citation2016) – to active ones, such as partner, co-designer, user-designer, diffused designer, and non-expert designer (Lee Citation2008; Manzini Citation2015; Simonsen and Robertson Citation2012). Some research challenges the perspective that there is a strict, easily definable boundary between designers and stakeholders as actors from both of these categories can be actively involved in designing (e.g. Hyysalo, Johnson, and Juntunen Citation2017; Kohtala, Hyysalo, and Whalen Citation2020). Nevertheless, our review showcased that the strict distinction between designers and stakeholders is still part of dominant discourse and practice in C&PD. Therefore, in this paper, we adopt a similar clear-cut division and define a stakeholder as an actor without formal design training who can inform, be involved in, or be affected by the design process and its outcomes.

Stakeholders are involved in design processes to varying extents that can be arranged along a spectrum. Design researchers conceptualize and name involvement typologies and the spectrum differently. For example, Harder, Burford, and Hoover (Citation2013) conceptualized a six-level spectrum; meanwhile, Hyysalo and Johnson (Citation2015), Lee (Citation2008), and Zhang and Dong (Citation2016) proposed differing four-level models. Each of these models encompasses some common and some unique characteristics. In , we summarize the perspectives in a seven-level spectrum. Although seems to imply strict boundaries between the spectrum levels, they are blurred, and a design process can include several types of involvement. Therefore, the spectrum should be viewed as an overview of the involvement variations rather than a collection of clear-cut categories.

Table 1. The seven levels of the stakeholder involvement spectrum.

Our findings indicate that C&PD is typically viewed as an approach in which designers involve stakeholders as active participants. Designers are seen as the experts of the design process (Taffe Citation2015) while stakeholders are seen as the experts of their own lives (Simonsen and Robertson Citation2012) who can contribute perspectives and knowledge from various domains and levels of expertise (Mattelmäki, Brandt, and Vaajakallio Citation2011). C&PD literature predominantly focuses on processes in which designers lead the efforts and invite stakeholders to participate rather than on designers assisting stakeholders in projects driven by stakeholders. Therefore, C&PD is most closely linked to the involved as design partners level of the involvement spectrum. However, there is no standard approach in C&PD as projects differ according to several variables (see ). As a result, standard terminology or framework of approaches for stakeholder participation are non-existent (Taffe Citation2015). The terms participation, participatory design, co-design, co-creation and collaborative design carry multiple meanings (Harder, Burford, and Hoover Citation2013; Lenskjold, Olander, and Halse Citation2015). They are used interchangeably by some while carrying specific, clearly defined meanings for others. Moreover, C&PD researchers organize their understanding of the subfield into dissimilar frameworks (e.g. Hyysalo and Johnson Citation2015; Sanders and Stappers Citation2008; Steen Citation2011). Therefore, we devised our classification of approaches within the field (see ) according to two variables: (a) the time of stakeholder participation and (b) the main reason for stakeholder involvement (see ). In a design project, design time and use time are not always distinct and, in some cases, they overlap (Botero and Hyysalo Citation2013); similarly, the reasons for stakeholder involvement can overlap and intertwine. Nevertheless, for the sake of simplicity we retain the binary view of time and a clear-cut view of the reasons for participation.

Table 2. Key variables in C&PD and their variations.

Table 3. The key sub-approach groups in C&PD.

2.3. The bioinclusive ethic

Environmental ethics is a type of applied ethics that strives to establish the moral relationship between humans and nature (Allhoff Citation2011; Sandler Citation2018). It strives to outline how humans “ought” to treat nature (Boylan Citation2013; Brennan and Lo Citation2016) and provides “methods and resources, such as rules, principles or guidelines to help make decisions in concrete situations” (Sandler Citation2018, 2). Environmental ethics explores what, if anything, in the natural environment has moral standing and intrinsic value alongside its instrumental value (Brennan and Lo Citation2016). An element has instrumental value when it is useful for humans to reach their goals; the same element has intrinsic value if it is important in itself, regardless of its usefulness to humans (Brennan and Lo Citation2016; Sandler Citation2018). There is no consensus on which elements of nature have intrinsic value and, thus, moral standing. Anthropocentric frameworks assign intrinsic value only to humans; meanwhile, non-anthropocentric frameworks assign it also to some elements of nature (Boylan Citation2013; Sandler Citation2018). The anthropocentric frameworks underlie and directly or indirectly support extractive capitalism, pervasive colonial politics of depredation and environmental violence, severe biodiversity crisis, and climate change. Therefore, anthropocentric environmental ethical frameworks are directly in conflict with the emerging multispecies turn in sustainability science (Rupprecht et al. Citation2020) and with the calls for epistemological and methodological decolonization in design, science, and humanities (Boisselle Citation2016; Escobar Citation2018; Schultz et al. Citation2018). They also significantly hinder required urgent, transformative actions for materializing sustainable futures.

There are various non-anthropocentric ethical frameworks which are often grouped into two main categories: individualistic and holistic environmental ethics (Brennan and Lo Citation2016; Sandler Citation2018). Individualistic frameworks argue that only (some) individual organisms can have intrinsic value and moral standing (Sandler Citation2018). There seem to be three main individualist perspectives: (a) ratiocentrism, which only grants moral standing to rational beings, such as humans, any other highly rational species, and robust AI; (b) sentientism, which grants moral standing to organisms with psychological capabilities, such as humans, other mammals and birds; and (c) biocentrism, which grants moral standing to all living organisms (Brennan and Lo Citation2016; Sandler Citation2018). Meanwhile, the holistic frameworks attribute intrinsic value and moral standing with a more systemic approach. There seem to be six main holistic perspectives: (a) ecocentrism grants moral standing to living systems (Sandler Citation2018); (b) the land ethic grants moral standing to land and its aspects – waters, soil, flora and fauna – and argues for a respectful relationship with nature (Sandler Citation2018); (c) deep ecology grants intrinsic value to all living things and views nature as part of the human self (Brennan and Lo Citation2016); (d) social ecology views nature as part of humans and vice versa, grants moral standing to nature and views environmental challenges as social challenges (Brennan and Lo Citation2016); (e) ecofeminist ethics links oppression and abuse of nature to oppression of women and argue for dismantling of the oppressive patriarchal systems (Brennan and Lo Citation2016); (f) new animist ethics challenge the rational, positivist Western views of reality, in which nature is solely a material resource and has no consciousness or sentience, by proposing, similarly to indigenous perspectives, to respectfully engage with natural entities (Brennan and Lo Citation2016). Each of the abovementioned perspectives has its proponents and critics. We selected the bioinclusive ethic to integrate with C&PD. We have several reasons to have done so. However, before we present our reasoning, we need to introduce the bioinclusive ethic in more detail.

The bioinclusive ethic is a non-anthropocentric, new animist ethical framework (Brennan and Lo Citation2016) developed by environmental philosopher Freya Mathews (Citation2011). It expands moral considerations from only humans to natural nonhuman beings (Mathews Citation2011). Mathews (Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2011) uses the term nonhuman to refer to natural entities that are not human, including individual living organisms and living systems such as rivers and the biosphere. Three interrelated, interdependent pillars of this ethic make it unique: (a) a non-dualistic definition of nature; (b) a shift toward a post-materialist conception of reality rooted in new animist perspectives; and (c) a shift toward synergy between humans and nonhumans.

The first pillar advocates for and proposes a non-dualistic, inclusive definition of nature. The dualistic view, prominent in Western cultures and philosophy, defines nature as something detached and autonomous from humans (Mathews Citation2011; Brennan and Lo Citation2016). The bioinclusive ethic proposes an alternative, inclusive definition: “It is possible…to understand nature not substantially, in terms of things which exist independently of human intention, but modally, as the collective pursuit of conative ends in accordance with the principle of least resistance” (Mathews Citation2011, 374). Conativity refers to an entity striving to maintain itself and realize its inherent potential (Mathews Citation2006, Citation2011), which is also referred to as autopoiesis (Mathews Citation2010; Maturana and Varela Citation1980). Autopoiesis, according to Wilson and Foglia (Citation2015), “describes living systems as active, adaptive, self-maintaining and self-individuating, that is, as having the property of self-reproducing through self-regulating strategies”; it is a certain form of cognition within the being or system that allows it to maintain itself. The principle of least resistance refers to the inclination of conative beings to preserve energy while pursuing their own ends, and allowing and supporting other beings to pursue theirs as much as possible (Mathews Citation2011). For example, an organism, if possible, avoids obstacles, but when confrontation is inevitable and necessary for survival; “it may…seek to turn the maneuvers of its opponent against it” (Mathews Citation2010, 369). The ethic acknowledges that humans differ from other conative beings: they have reflexive awareness with which they may disregard the principle of least resistance and act in accordance with other principles stemming from, for example, culture or socio-economic-technical systems (Mathews Citation2011). Overall, the bioinclusive ethic conceptualizes nature as a collective of human and nonhuman living beings that pursue their own needs while allowing and enabling other living beings to pursue theirs. It grants moral standing and intrinsic value to both human and nonhuman members of this collective while still acknowledging that humans differ from other conative beings.

The second pillar advocates for a shift in the human conception of reality from the currently dominant materialism to post-materialism (Mathews Citation2006). Mathews (Citation2006) understands materialism as a view of physical reality that sees reality itself as “lacking any inner principle, any attribute analogous to mentality – subjectivity, spirit, sentience, agency or conativity" (Mathews Citation2006, 86). Mentality here refers to a certain type of cognition or consciousness (Brennan and Lo Citation2016; Wilson and Foglia Citation2015). The ethic argues that materialistic views have enabled humans to view nature solely as a collection of controllable mechanisms and causal relationships, and to unapologetically use nature to satisfy our own needs and desires, leading to environmental degradation (Mathews Citation2006). To overcome the crisis, humanity should shift to a post-materialistic conception of reality (Mathews Citation2006). In post-materialism, humans recognize the “mentalistic aspect of physicality” (Mathews Citation2006, 93) and the “psychophysical nature of reality” (Mathews Citation2010). These perspectives build upon indigenous views that nonhuman beings – such as animals, plants, rocks, forests and weather systems – have sacred souls that must be respected (Brennan and Lo Citation2016):

When a forest is no longer sacred, there are no spirits to be placated and no mysterious risks associated with clear-felling it. A disenchanted nature is no longer alive. It commands no respect, reverence or love. It is nothing but a giant machine, to be mastered to serve human purposes (Brennan and Lo Citation2016, para. 35)

Therefore, the ethic argues for post-materialism, in which norms, rules and values should stem from respect toward the conativity of natural entities (Mathews Citation2006). Thus, materialistic knowledge about nature rooted in anthropocentrism (White Citation1967), must be supplemented and even subsumed by more metaphysical, poetic, secular views on matter and nature (Mathews Citation2006). Overall, the bioinclusive ethic argues that natural beings and systems have a particular kind of mind, cognition or “mentality” which humans should acknowledge and account for, and humans should supplement their scientific, materialistic quest to understand nature with ways of knowing that account for nonhuman mentality.

The third pillar of the ethic advocates for a shift in human relationships with nature from domination to synergy. Currently, humans dominate nature by perceiving it as a separate entity to be tamed and used to satisfy all human desires and needs (Brennan and Lo Citation2016; Mathews Citation2006). Humans should instead be in synergy with nature: viewing themselves as part of nature, recognizing the mentality of other natural elements, and allowing nonhumans to co-shape human desires and actions (Mathews Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2011). Mathews (Citation2006) exemplified this with a case of developing a hair gel harmless for rivers. She proposes that before co-shaping the requirements for the gel, it is important to allow the needs of the river to inform whether such a gel is needed at all:

The questions we should be asking of the river is not merely, what does it want from this hair gel, but what does it want from us? …When we ask this question, we might find that the kind of people the river wants us to be and the kind of cultures it wants us to create make us forget about hair gel altogether (Mathews Citation2006, 107; original emphasis)

In this way, there would be no separation between sustainability-aligned and sustainability-unaligned desires and means (Mathews Citation2011). Synergy has developed in living systems through evolution; meanwhile, human societies have strived to separate from and dominate nature and need to intentionally realign with synergy (Mathews Citation2011). This realignment should not reverse human societies to their primitive beginnings but rather re-shift the developed culture (Mathews Citation2010); unfortunately, the ethic does not provide any clarification of what this means in practice.

The ethic also describes synergy as the “reflective participation in creative co-action” (Mathews Citation2010, 10; original emphasis). It suggests that humans can develop synergy through communicative engagements with nonhumans via, for example, experiential learning or animist-inspired rituals (Mathews Citation2010, Citation2011) rooted in post-materialist perception of reality and reflection on the metaphysical, philosophical meanings of the interactions (Mathews Citation2008, Citation2010). Such views correlate with recent calls in environmental psychology for reconnecting humans and nature through reflective encounters (Ives et al. Citation2018; Zylstra et al. Citation2014) which do not, however, require a shift to a post-materialist conception of reality. The current materialist conception makes it challenging to imagine communicative engagement, not only with non-communicative living organisms and systems, but also with communicative animals, such as birds and dogs. Thus, creative co-action with nonhumans requires a shift in our conception of reality, including scientific ontologies and epistemologies, and the acknowledgement of non-Western, indigenous, experiential knowledge and engagements with nature.

The bioinclusive ethic provides unconventional, non-anthropocentric grounds for integration with C&PD, yet it has its limitations. The ethic has been defined by a single author in one of her works (see Mathews Citation2011). It is supported and further fleshed out by her other work and contextualized as a new animist ethic by The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Brennan and Lo Citation2016). No other authors have yet discussed the ethic. This poses challenges to engaging with and building an understanding of this framework through multiple, differing perspectives. Moreover, it has been challenging to find direct critiques of the ethic while building an understanding of it. We have only been able to locate critiques of new animism overall. The critiques and our own engagement with the ethic suggest that the framework remains vague in its definitions of mentality, how it presents in entities and which entities exactly have or do not have it (Andrews Citation1998). The ethic also provides little guidance as to how its principles, views and proposed synergy with nature can be achieved in practice. Furthermore, the bioinclusive ethic is not the only area of thought that argues for post-materialism. Post-humanism and its branches, for example, new materialism (Braidotti and Hlavajova Citation2018) propose and build thought structures on similar ideas. Finally, others (e.g. Haraway Citation2016; Tsing Citation2015; Kimmerer Citation2013; Walsh, Böhme, and Wamsler Citation2020; West et al. Citation2020) have also proposed non-dualistic definitions of nature and focus on the relation between humans and nature. It seems that these authors and areas of thought arrive to very similar arguments while departing from differing starting points. Therefore, it seems that further work on developing the bioinclusive C&PD should also consider other areas of thought besides the bioinclusive ethic and other environmental ethics to acknowledge existing theoretical and potentially practical structures for non-anthropocentric C&PD.

While acknowledging the limitations of the ethic and existence of other similar and more commonly used perspectives, we still view the bioinclusive ethic as an important perspective to integrate with C&PD, mainly due to three reasons. First, it provides a starkly different view of nature, conception of reality and ways to interact with nature than most Western environmental ethical frameworks. Other non-anthropocentric frameworks originate in and encompass the dualistic human–nature divide and materialism, seemingly without sufficiently questioning them (Boylan Citation2013; Sandler Citation2018). Current C&PD is also rooted in human–nature dualism and materialism, which can be examined through the alternative bioinclusive lens. Second, the bioinclusive ethic accentuates the changes needed in human society for reaching sustainability (Mathews Citation2008, Citation2011) while most Western environmental ethics do not. Other ethical frameworks arise from concerns about the degraded, fragile state of “wild” nature, the “wilderness and focus on identifying natural elements with intrinsic value and establishing rightness or wrongness of acts towards them while lacking concrete arguments on ways to yield systemic sustainability” (Brennan and Lo Citation2016). Meanwhile, the bioinclusive ethic proposes synergy as an option for realigning humans with the rest of nature. Finally, the bioinclusive ethic has previously engaged with design when Mathews (Citation2011) sought to strengthen the philosophical bases for biomimetic design.

3. A Conceptual Framework and Research Directions for Bioinclusive C&PD

The bioinclusive ethic provides one of the alternative ways to look at the current C&PD embedded in the anthropocentric societies that dominate nature and serve the needs of (some) humans above anything else. Although a fully bioinclusive C&PD is impossible to achieve right away – or, potentially, ever – the ethic provides an opportunity to reflect upon the assumptions, unspoken agreements and practices of C&PD. We focused on five interrelated areas that seemed especially prominent: the goals and aims of processes; the distinction between needs and desires; the inclusion of nonhuman stakeholders; the development of nonhuman-inclusive processes; and definitions of C&PD, designer and design. This paper does not aim to provide comprehensive, fully developed explorations of these areas. Rather, we aim to contribute to and strengthen the discussion on how C&PD can become more inclusive of the needs of natural nonhumans.

3.1. Goals and aims

The goals and aims of C&PD processes require critical reflection. Currently C&PD is embedded in the dominant, Western worldviews – which view humans as separate from and entitled to dominate nature -- and socio-economical-technical systems. Both impact the goals and aims of the projects but are rarely made explicit. The Western worldviews likely dictate that C&PD only serves humans and ensures that the new solutions fit the Western worldview, even if designed for other contexts. More concretely, C&PD likely (predominantly) designs only for humans; disregards any relevant natural nonhuman stakeholders; takes for granted and fails to acknowledge nonhuman instrumental contributions; and disregards any damage it might cause to nonhumans. The dominant socio-economical-technical systems also impact design goals, aims and behaviors. Generally, they likely lead to the creation of solutions that fit or barely modify the current societal structures, neoliberal economy and underlying power dynamics. Unfortunately, the goals and aims of the Western worldviews and the dominant socio-economical-technical systems are not aligned with the needs of the biosphere. Thus, the inherited goals and aims in C&PD are likely contrary to those of sustainability, and most, if not all, C&PD projects contribute to the degradation, rather than sustenance or regeneration, of nature. Therefore, when striving to build a sustainable world, it is critical to (a) scrutinize which design goals and aims stem from the dominant worldviews and systems and (b) establish whether, why, how and when C&PD should strive to shift or to maintain the dominant status quo. Some research has touched upon the relevance and impact of structural elements, such as time (Pschetz and Bastian Citation2018) and political structures (Pedersen Citation2016), on C&PD, but extensive further research is still required. The discourse of decolonizing design has reflected on the worldviews underlying design by questioning which of them come from Western colonialism, anthropocentrism, modernism, white supremacy, racism, rationalism, capitalism, and neoliberalism (e.g. Schultz et al. Citation2018; Tlostanova Citation2017). The sustainability transformations discourse has also started to acknowledge and research how the Western worldviews inform the sustainability discourse and developed solutions. For example, Lam et al. (Citation2020) reviewed the role and the expansive potential of indigenous perspectives when shaping goals and solutions in sustainability. C&PD would likely benefit from these research areas in uncovering hidden aims, goals and structures. The following questions could be explored in further research: Who and what shapes the goals and aims of the project? What kind of worldview and system requirements inform the goals and aims? How do the project goals and aims represent the needs of nonhumans? Answers to these questions can articulate both the visible and covert project goals and aims and explicate who and what has the power to set them.

3.2. Needs versus desires

The bioinclusive perspectives also urge us to reflect upon the necessity to differentiate between needs and desires. The bioinclusive ethic asserts that human desires should be co-shaped by natural nonhumans. Though the ethic does not clearly define needs and desires nor ways to differentiate between them, it seems to imply that needs are aspects that humans need in order to survive as a species while desires are aspects that exceed mere survival. Interestingly, C&PD rarely uses the word desires to describe the aspiration of humans to do, have or create something. The term needs is more prominent. C&PD and bioinclusive ethic likely view needs and desires differently. For instance, the example of hair gel presented above indicates that, from the bioinclusive perspective, hair gel is likely to be a desire; meanwhile, a C&PD project would be likely to consider it a need. Therefore, C&PD most likely does not differentiate between needs and desires. Although discussion on the differences is ongoing in the sustainability discourse (e.g. Jackson, Jager, and Stagl Citation2004; Max-Neef Citation1989), our review indicates that it has not yet been embedded in C&PD. This lack of differentiation could be linked to the “confusion” between needs and desires in dominant worldviews and systems. For example, Jackson, Jager, and Stagl (Citation2004) suggested that there are two key discourses that impact on the view of the division between needs and desires. First, economics seem to mainly focus on desires because economic activity benefits from satisfying limitless human desires instead of finite human needs (Jackson, Jager, and Stagl Citation2004). This perspective likely informed C&PD as design has been developed and used within the economic paradigm. Second, varied needs theories that propose differing perspectives (Jackson, Jager, and Stagl Citation2004), such as Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchical pyramid of needs and Max-Neef (Citation1989) axiological theory of needs and their satisfiers. Currently, the dominant C&PD discourse does not seem to engage with such theories. Additionally, each human participant likely would add own perspectives on the division between needs and desires. Thus, C&PD could have a tendency to focus on designing for human desires rather than needs. If C&PD starts shifting toward bioinclusive practice, systematically integrating discussions on the difference between needs and desires into its theory and practice is critical.

3.3. Nonhuman stakeholders

The bioinclusive perspectives urged us to revisit the unwritten criteria for recognizing a party as a stakeholder of a C&PD project. The bioinclusive ethic argues that natural nonhumans have moral standing and should co-shape human desires and developments that satisfy these desires. Earlier we defined a stakeholder as an actor without formal design training who can inform and is involved in or affected by the design process and its outcomes. Thus, a relevant nonhuman can qualify as a stakeholder. However, our review indicates that currently almost no C&PD projects acknowledge nonhuman stakeholders. Not only is their moral standing and intrinsic value mostly left unrecognized, but also, sadly, their instrumental value and contribution to, for example, providing resources, “ecosystem services” and waste storing are not recognized. Thus, currently, most C&PD projects ignore and take for granted all the contributions or value of nonhumans, focusing solely on humans.

Before reflecting upon which nonhuman entities are relevant in bioinclusive C&PD processes, it is critical to outline the reasons to involve nonhumans. The bioinclusive ethic highlights that striving toward sustainability of non-dualistically defined nature is its main objective. Thus, the key reason for involving nonhuman stakeholders in bioinclusive C&PD would be the development of sustainable solutions that support life of all nature. Additionally, three of the four currently established reasons for stakeholder involvement (presented in ) seem applicable in the bioinclusive context: (a) the political/moral reason, in the bioinclusive perspective, would suggest that morally, both human and nonhuman stakeholders should be able to co-shape the solutions that will affect their lives; (b) the pragmatic reason, in the bioinclusive perspective would suggests that, by nonhumans co-shaping human desires and means, it would be possible to satisfy the co-shaped human desires while also satisfying the needs of nonhumans thus enabling the creation of ends and means that better satisfy the needs of all stakeholders; (c) the innovativeness-related reason would suggests that, together, humans and nonhumans can co-shape desires and the means to achieve them that are unimaginable if solely shaped by one or the other thus elevating the innovativeness level of ideas and solutions. Last reason correlates to research indicating that innovativeness of ideas and solution increases when designers are exposed to biological examples (Cheong and Shu Citation2013; Wilson et al. Citation2010). Meanwhile, the commercial reason for stakeholder involvement (see ) is rooted in the capitalistic economic paradigm and, predominantly, strives to promote financial gains. This position is contrary to the bioinclusive ethic which focuses on the sustainability of nature rather than on capital creation for a brand through the creation of desirable solutions. Therefore, the bioinclusive commercial reason cannot be outlined before the bioinclusive economy and commerce are outlined. This initial review showcases that there are four reasons for involving nonhuman stakeholders in design, all of which aim to design sustainable solutions.

As we have identified reason for nonhuman stakeholder involvement, we can start identifying what entities can and should be considered stakeholders. The bioinclusive perspective argues that conative beings have moral standing. Unfortunately, it does not provide a list of conative entities nor a clear, easily applicable rubric with which to identify one. Moreover, the ethic is not the sole source but only one of the sources that can provide insight into the types of entities to involve. Other environmental ethical frameworks, as introduced above, would suggest differing elements to be involved, ranging from individual beings to holistic living systems. Sustainability science -- which is a research area that strives to build systemic solutions for the sustainability crisis (Bettencourt and Kaur Citation2011) -- likely would indicate that systemic, holistic natural stakeholders are relevant when striving to build sustainable solutions because sustainability is a property of a system, not of its sub-systems and individual elements (Clayton, Clayton, and Radcliffe Citation1996). Moreover, indigenous knowledge and perspectives (Lam et al. Citation2020) would suggests entities beyond knowledge rooted in dualism and domination over nature. Importantly, each of these perspectives is likely limited and can only provide a partial insight about natural entities relevant for C&PD. Therefore, transdisciplinary efforts (Hadorn et al. Citation2008) are likely to be needed to outline which nonhuman entities to include in C&PD. We use the term transdisciplinary to indicate a research position which integrates scientific knowledge and other knowledge, such as professional knowledge and indigenous knowledge (Hadorn et al. Citation2008).

There are precedents and ongoing projects in design and its adjacent areas that do recognize or incorporate nonhuman stakeholders. Westerlaken (Citation2020) has proposed a framework for multispecies perspectives on design that acknowledge sentient animals. Akama, Light, and Kamihira (Citation2020) have argued for an ontological, theoretical and methodological shift toward considering more-than-humans in participatory design. Thomas, Remy, and Bates (Citation2017, chap. 3) have suggested expanding the concept of a stakeholder, which they refer to as a user, to include “an object, person, animal, or ecosystem.” Ongoing research projects, such as Creative Practices for Transformational Futures (CreaTures Citationn.d.), are exploring the role of nonhumans in design and other creative practices. The field of animal–computer interaction views animals as key stakeholders and users of technologies (Driessen et al. Citation2014; Piitulainen and Hirskyj-Douglas Citation2020; Webber et al. Citation2020). Some projects have developed games for nonhuman mammals with their direct participation (Jørgensen and Wirman Citation2016; Westerlaken and Gualeni Citation2014, Citation2016). Mancini et al. (Citation2015) involved dogs in redesign of a laboratory machine used by dogs to detect cancerous human tissues. Aspling, Wang, and Juhlin (Citation2016) conducted a project around plant–computer interaction aimed at supporting plant–human communication. Avila (Citation2017) conducted a design project accounting for the needs of plant–insect–human networks. These examples show the potential of recognizing nonhumans as stakeholders and even as active participants. Furthermore, the perspective that nature should shape human activity seems to align with the perspectives of regenerative design (du Plessis Citation2012; Lyle Citation1996). The regenerative design paradigm “attempts to address the dysfunctional human–nature relationship by entering into a co-creative partnership with nature” (du Plessis Citation2012, 19). It views nonhumans as partners with which humans co-evolve (Cole Citation2012). Nevertheless, these ideas have not yet gained much traction in the mainstream C&PD theory and practice. Furthermore, these ideas require further examination to conclude which, if any, of them align with the bioinclusive, non-anthropocentric principles.

3.4. Nature-inclusive processes

The inclusion of nonhumans in C&PD requires extensive reflection on and development of appropriate C&PD processes. As described in Section 2, currently, stakeholder involvement is unique in every project. Designers can choose from and create varied procedures, methods, and tools to facilitate participation that best supports the project and matches the participants’ abilities. Therefore, it is impossible to outline a single model for bioinclusive C&PD processes. Nevertheless, it is possible to outline the initial considerations and principles. Below, we formulate early considerations for bioinclusive C&PD processes in design time and use time. These considerations encompass vagueness in defining what participation is as it is defined in many ways (Arnstein Citation1969; Simonsen and Robertson Citation2012). Unfortunately, an in-depth analysis of the varied perspectives on participation in C&PD lies outside the scope of this paper. Therefore, further research is necessary to define the meaning of participation in bioinclusive C&PD clearly.

In design time, C&PD approaches (see ) heavily rely on the ability of one human to communicate with another human via one of, or the combination of, verbal, visual and bodily communication (Simonsen and Robertson Citation2012). If good communication between participants is challenging – for example, if one or several participants are children, do not speak the same language or are physically or mentally disabled – the process becomes challenging. The inability of a stakeholder to effectively, clearly communicate their perspectives to others challenges established C&PD procedures and shifts the power dynamics (Brereton et al. Citation2015; Hendriks et al. Citation2018). Currently, communicative encounters between humans and nonhumans are limited, which makes the participation of nonhumans as direct, active partners very challenging. Bioinclusive C&PD would require the development of alternatives that, hopefully, fully or (more realistically) partly enable engagement between the human and nonhuman stakeholders. We recognize two potential avenues through which to address this challenge. First, nonhuman stakeholders can be represented by a human proxy. For example, individuals with new animist and indigenous worldviews could represent the moral value and mentality of natural entities; meanwhile, scientists could represent the instrumental value and systemic roles of the same entities. Second, involvement approaches should be rethought in a collaborative, transdisciplinary manner. Experts and representatives of Western and non-Western knowledge fields and researchers of C&PD should jointly outline ways to foster human and nonhuman engagement. These two avenues, other opportunities, and their benefits and limitations must be explored in future research.

While the direct participation of nonhumans is challenging in design time, in use time, direct participation of nonhumans is already possible. For instance, nonhumans often adjust landscape architecture solutions; meanwhile, dogs can rearrange the interior of a home, readjust their beds or chew toys. In such cases, the perception of the action plays a key role: Is the entity damaging the human design or adjusting it to better satisfy its needs? It is critical to re-examine what exactly constitutes participation in use time. If only permitted and encouraged adjustments are considered participation, then co-design with natural entities in use time faces similar communication challenges as it does in design time. However, if all types of adjustments are considered participation, then recognizing such participation requires a mindset shift among humans. In this case, humans need to foster an open, accepting mindset that views nonhuman-made changes to a design as adjustments and cases of design in use. Unfortunately, the participation of nonhumans in use time alone, without their participation in design time, does not fully align with the bioinclusive principles. In use time, nonhumans are, most likely, unable to shape the human desires that have initiated the project and informed its aims, process and outcomes. Therefore, outlining nonhuman participation in design time is mandatory in order to fully enable nonhuman participation in design processes according to the bioinclusive principles.

There are existing examples of nonhuman involvement in design. In design, researchers have involved nonhumans during design time in three main ways: via human proxy; by investigating them in a natural habitat; and through direct participation. Frawley and Dyson (Citation2014) used animal personas to represent the perspectives of chickens in participatory design processes with humans. Several projects (Avila Citation2017; Bos et al. Citation2009; Isokawa et al. Citation2016; Zeagler et al. Citation2016) have studied nonhuman stakeholders in their habitat and through scientific information, but have chosen not to involve them as direct participants. Meanwhile, others (Jørgensen and Wirman Citation2016; Mankoff et al. Citation2005; Westerlaken and Gualeni Citation2016) have involved animals as the direct participants of participatory processes, predominantly through play. Robinson and Torjussen (Citation2020) used buttons as a communication tool between humans and dogs. Webber et al. (Citation2020) developed a process where orangutans were included in the design process through human proxies in design time and as direct participants in use time. Design researchers have also facilitated nonhuman participation in use time. Wirman and Jørgensen (Citation2015) tested solution prototypes with orangutans, and Galloway (Citation2017) has conducted long-term, open-ended processes to investigate the relationship between sheep and human-made solutions. Researchers involved in such projects have reflected on the potential limitations of the nonhuman involvement in the design project which seem relevant for bioinclusive design: the inability of nonhumans to impact on the aims and their unequal role in the processes. Grillaert and Camenzind (Citation2016) have questioned whether dogs are involved in the setting of goals and truly able to impact on the goals of a design project they were involved in. Meanwhile, Westerlaken and Gualeni (Citation2016) and Ritvo and Allison (Citation2014) have reflected that nonhumans are not, and may never be, equal participants in human-led design processes. Therefore, such nature-inclusive projects and processes need to be carefully examined in order to understand what is the role of the nonhuman stakeholders in them.

3.5. Definitions of C&PD, designer, and design

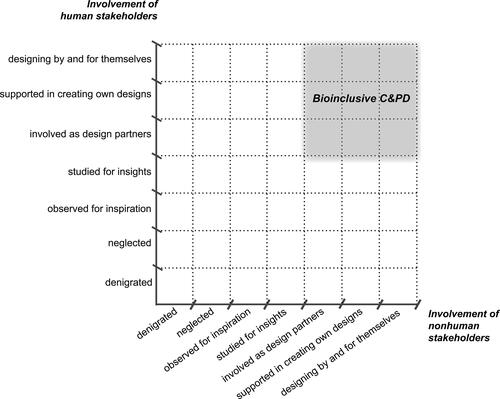

The inclusion of nonhuman stakeholders would change the spectrum of stakeholder involvement so that it would represent both types of stakeholders. The bioinclusive ethic acknowledges that humans differ from other conative beings in having reflexive awareness (Mathews Citation2011), and the current dualistic definition of nature is deeply ingrained in design theory and practice. Therefore, to accentuate the inclusion of nonhuman perspectives, we choose to represent human and nonhuman involvement on two separate spectrums and combine them in a matrix (see ) where, according to the levels presented in , the x-axis represents nonhuman involvement and the y-axis represents human involvement. This matrix served as a tool for further reflection and surfaced three key areas for exploration.

First, the matrix does not represent the structural elements of C&PD processes. As discussed above, Western worldviews and socio-economic-technical systems affect design processes; thus, they have a certain amount of power in design projects. Meanwhile, the involvement spectrum represents the power stakeholders have over the process as stakeholders have more power over the process and outcomes on the right-side of the spectrum. Unfortunately, the spectrum and, consequently, the matrix do not represent the power of structural elements. While the matrix may be a useful tool for reflection on the extent to which nonhuman and human stakeholders are involved in the process, it does not represent all the power structures surrounding a project. Therefore, further research is needed in order to understand and visually represent all the power dynamics in a bioinclusive C&PD project.

Second, as we attempted to position the bioinclusive C&PD in the matrix, potential limits of the current C&PD definition surfaced. At the moment, C&PD predominantly corresponds with the involved as design partners level of the spectrum. Thus, bioinclusive C&PD should correspond to the matrix square where both nonhuman and human stakeholders are involved as design partners. However, the bioinclusive perspectives suggest that co-creative synergy can also happen between one human and one or several nonhuman entities. Thus, in bioinclusive C&PD, a human stakeholder could co-create with a nonhuman stakeholder with or without a designer. In this case, bioinclusive C&PD correlates to a quadrant with human and nonhuman stakeholders involved as design partners and designing by and for themselves, represented in . As boundaries between spectrum levels are blurry, bioinclusive C&PD can bleed into the studied for insights level, for example, if some nonhuman stakeholders are represented by human proxies. However, such a categorization of bioinclusive C&PD seems to question the widely accepted definition of C&PD as an approach in which designers invite and involve stakeholders into design processes. This view seems designer-focused because it accentuates that a designer is crucial to designing in a collaborative manner. This notion is likely to stem from the roots of design as an expert-specific practice that was later opened up to non-expert designers. However, the designer-focused view of C&PD excludes any collective creativity and design done with minor (or no) designer involvement. Thus, the bioinclusive perspectives call for an explicit re-evaluation of the widely accepted definition of C&PD, its boundaries, and the kinds of creative co-action it excludes.

Third, the development of bioinclusive C&PD also requires a re-evaluation of the meanings of the terms designer, designing, and design. When one human and one nonhuman jointly co-shape a solution, the roles and the act can be categorized and positioned on the matrix differently. If the human is classified as a designer, then the process is positioned as denigrating human stakeholders and involving a nonhuman stakeholder as design partner. If the same person is classified as a stakeholder, the same process is positioned as a human designing with and for themselves while involving a nonhuman entity as a partner in the design process and may or may not be classified as design. Thus, the same activity can be classified differently based on the categorization of the human participant. This illuminates a challenge with categorizing someone as a designer: Is the role of a designer only assigned to those with expert training or also to other individuals who shape solutions for the world? Furthermore, is design (a) an activity exclusive to expert designers; (b) the activity of solving a problem; (c) the activity of shaping or reshaping something; (d) a combination of the previous definitions; or (e) something else? These question correlate to research striving to articulate a more complex view on the designer–stakeholder spectrum (e.g. Kohtala, Hyysalo, and Whalen Citation2020) which has a marginal role in widespread views in C&PD; further research must examine how such complex views link to the bioinclusive perspectives and further re-examine the widely accepted definitions. If design is not solely the activity of expert designers, then any human could be a designer, and it may indicate that nonhumans can also design.

4. Conclusions

Currently, C&PD focuses on human wants and needs in an anthropocentric manner which contributes to unsustainability. Having reexamined the anthropocentric base of C&PD, we propose twelve key principles for a non-anthropocentric, bioinclusive C&PD:

focuses on principles rather than unified process prescriptions.

openly strives to change the dominant worldview to become a bioinclusive one:

views nature as a living collective that consists of human and nonhuman beings and systems that pursue their needs while allowing and enabling other living beings and systems to pursue theirs.

views natural living organisms and systems as having a particular kind of mentality.

strives for synergy with nature in which nonhumans co-shape human desires and the means of achieving these desires.

acknowledges human and nonhuman stakeholders who can inform, and are involved in or affected by the design process and its outcomes:

human stakeholders are individuals or communities of people, and

nonhuman stakeholders are living organisms, communities and systems.

acknowledges the intrinsic value and instrumental value of nonhuman stakeholders.

advocates for the inclusion of nonhuman stakeholders in its projects:

primarily, to reach the sustainability of nature, which includes humans, nonhumans, human-made systems and natural systems; and

secondarily, to allow human and nonhuman stakeholders to shape solutions that will impact on their lives, to design solutions that better satisfy the needs of human and nonhuman stakeholders and to create innovative solutions that are unlikely to be imagined solely by humans.

explicates structural elements – such as Western worldviews, socio-economic-technical systems and their principles, aims and needs – that inform and impact the design process.

explicates the process aims that arise from the structural elements of the process.

openly differentiates between human needs, which are aspects that humans need to survive as a species, and desires, which are aspects in human life that go beyond mere survival.

enables nonhuman stakeholders to co-shape human desires and the means to achieve these desires in a way that is aligned with the needs of nonhuman systems.

definitely includes nonhuman stakeholder participation in design time and preferably includes it in use time:

In design time, this is done via active, direct nonhuman participation or representation by human proxies.

In use time, this is done via nonhuman stakeholder modifications to a design solution.

recognizes that a human or nonhuman stakeholder is also, at least partly, a designer as they shape the world with or without special training in how to do it.

defines designing and design as an activity or act of human and nonhuman actors, shaping or reshaping something in the world.

The conceptual framework must be further developed through transdisciplinary research across at least six research directions:

systematically uncovering and effectively visualizing structural elements and their impact

differentiating between human needs and desires

developing clear guidelines for identifying relevant nonhuman stakeholders

elaborating what constitutes nonhuman stakeholder participation

developing practice-relevant principles and guidelines for structuring, planning and conducting bioinclusive C&PD processes in design time and use time

re-examining the terms C&PD, designer, designing, and design.

Acknowledgments

The first version of this article has been presented at the European Academy of Design Conference 2019 and included in its proceedings which were published as a supplement of the Design Journal. The current version is significantly revised and expanded. We would like to acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers who reviewed this article for the conference. We also want to thank Jane Pirone and Heather Barnett who reviewed the article for publication in Design and Culture journal.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that have appeared to influence our work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emīlija Veselova

Emīlija Veselova is a doctoral researcher at the NODUS Sustainable Design Research Group in Aalto University, Espoo, Finland. Her doctoral project focuses on developing theoretical and methodological framework for designing with natural stakeholders for sustainability. She holds an MA in collaborative design with a minor in creative sustainability from Aalto University and is an alumna of UnSchool of Disruptive Design. [email protected]

İdil Gaziulusoy

Dr İdil Gaziulusoy is Assistant Professor of Sustainable Design and leader of NODUS Sustainable Design Research Group at the Department of Design, Aalto University, Finland. İdil is a sustainability scientist and a design researcher focusing on long-term, structural, systemic transformations to sustainability through the lens of design and innovation. She has lived and worked in Turkey, New Zealand, and Australia before moving to Finland to undertake her current position. [email protected]

References

- Abson, David J., Joern Fischer, Julia Leventon, Jens Newig, Thomas Schomerus, Ulli Vilsmaier, Henrik von Wehrden, et al. 2017. “Leverage Points for Sustainability Transformation.” Ambio 46 (1): 30–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y.

- Akama, Yoko, Ann Light, and Takahito Kamihira. 2020. “Expanding Participation to Design with More-than-Human Concerns.” In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020-Participation(s) Otherwise, Manizales, Colombia, June 15–19, 2020, Vol. 1, 1–11.

- Allhoff, Fritz. 2011. “What Are Applied Ethics?” Science and Engineering Ethics 17 (1): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-010-9200-z.

- Almirall, Esteve, and Jonathan Wareham. 2011. “Living Labs: Arbiters of Mid-and Ground-Level Innovation.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 23 (1): 87–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2011.537110.

- Andrews, J. 1998. “Weak Panpsychism and Environmental Ethics.” Environmental Values 7 (4): 381–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.3197/096327198129341636.

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Aspling, Fredrik, Jinyi Wang, and Oskar Juhlin. 2016. “Plant-Computer Interaction, Beauty and Dissemination.” In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction, Milton Keynes, UK, November 15–17, 2016, 5. ACM. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/2995257.2995393.

- Avila, Martin. 2017. “Ecologizing, Decolonizing: An Artefactual Perspective.” In Proceedings of the Nordes 2017: Design and Power Conference, Oslo, Norway, June 15–17, 2017, 1–8.

- Bettencourt, Luís M. A., and Jasleen Kaur. 2011. “Evolution and Structure of Sustainability Science.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (49): 19540–19545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102712108.

- Bødker, Keld, Finn Kensing, and Jesper Simonsen. 2011. “Participatory Design in Information Systems Development.” In Reframing Humans in Information Systems Development, edited by Hannakaisa Isomäki and Samuli Pekkola, 115–134. London: Springer.

- Boisselle, Laila N. 2016. “Decolonizing Science and Science Education in a Postcolonial Space (Trinidad, a Developing Caribbean Nation, Illustrates).” Sage Open 6 (1): 215824401663525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016635257.

- Booth, Andrew, Anthea Sutton, and Diana Papaioannou. 2016. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. London: Sage.

- Bos, A. P., P. W. G. Groot Koerkamp, J. M. J. Gosselink, and Sjoerd Bokma. 2009. “Reflexive Interactive Design and Its Application in a Project on Sustainable Dairy Husbandry Systems.” Outlook on Agriculture 38 (2): 137–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.5367/000000009788632386.

- Botero, Andrea, and Sampsa Hyysalo. 2013. “Ageing Together: Steps towards Evolutionary Co-Design in Everyday Practices.” CoDesign 9 (1): 37–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.760608.

- Boylan, Michael, ed. 2013. Environmental Ethics. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bradwell, Peter, and Sarah Marr. 2008. “Making the Most of Collaboration: An International Survey of Public Service Co-Design.” Demos Report 23. London: Demos/PriceWaterhouseCoopers Public Sector Research Sector.

- Braidotti, Rosi, and Maria Hlavajova. 2018. Posthuman Glossary. London: Bloomsbury.

- Brennan, Andrew, and Yeuk-Sze Lo. 2016. “Environmental Ethics.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2016. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/ethics-environmental/.

- Brereton, Margot, Laurianne Sitbon, Muhammad Haziq Lim Abdullah, Mark Vanderberg, and Stewart Koplick. 2015. “Design after Design to Bridge between People Living with Cognitive or Sensory Impairments, Their Friends and Proxies.” CoDesign 11 (1): 4–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1009471.

- Carroll, John M., and Mary Beth Rosson. 2007. “Participatory Design in Community Informatics.” Design Studies 28 (3): 243–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2007.02.007.

- Ceballos, Gerardo, Paul R. Ehrlich, Anthony D. Barnosky, Andrés García, Robert M. Pringle, and Todd M. Palmer. 2015. “Accelerated Modern Human–Induced Species Losses: Entering the Sixth Mass Extinction.” Science Advances 1 (5):e140025. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400253.

- Ceschin, Fabrizio, and A. İdil Gaziulusoy. 2020. Design for Sustainability (Open Access): A Multi-Level Framework from Products to Socio-Technical Systems. London: Routledge.

- Cheong, Hyunmin, and L. H. Shu. 2013. “Using Templates and Mapping Strategies to Support Analogical Transfer in Biomimetic Design.” Design Studies 34 (6): 706–728. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2013.02.002.

- Churchill, Joan, Eric von Hippel, and Mary Sonnack. 2009. Lead User Project Handbook: A Practical Guide for Lead User Project Teams. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Clarke, Adele E., and Susan Leigh Star. 2008. “The Social Worlds Framework: A Theory/Methods Package.” The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies 3: 113–137.

- Clayton, Tony, Anthony M. H. Clayton, and Nicholas J. Radcliffe. 1996. Sustainability: A Systems Approach. New York: Earthscan.

- Clement, Andrew, and Peter Van den Besselaar. 1993. “A Retrospective Look at PD Projects.” Communications of the ACM 36 (6): 29–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/153571.163264.

- Cole, Raymond J. 2012. “Transitioning from Green to Regenerative Design.” Building Research & Information 40 (1): 39–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2011.610608.

- CreaTures. n.d. “Creative Practices for Transformational Futures.” CreaTures. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://creatures-eu.org/.

- Cross, Nigel, ed. 1972. Design Participation: Proceedings of the Design Research Society's Conference, Manchester, September 1971. London: Academy Editions.

- Driessen, Clemens P. G., Kars Alfrink, Marinka Copier, Hein Lagerweij, and Irene van Peer. 2014. “What Could Playing with Pigs Do to Us? Game Design as Multispecies Philosophy.” Antennae: The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture 30: 79–102.

- Ehn, Pelle. 1993. “Scandinavian Design: On Participation and Skill.” In Participatory Design: Principles and Practices, edited by Douglas Schuler and Aki Namioka, 41–77. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

- Ehn, Pelle. 2008. “Participation in Design Things.” In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008, edited by Jesper Simonsen, Toni Robertson, and David Hakken, 92–101. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Fischer, Gerhard, Elisa Giaccardi, Yunwen Ye, Alistair G. Sutcliffe, and Nikolay Mehandjiev. 2004. “Meta-Design: A Manifesto for End-User Development.” Communications of the ACM 47 (9): 33–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/1015864.1015884.

- Fischer, Gerhard, Kumiyo Nakakoji, and Yunwen Ye. 2009. “Metadesign: Guidelines for Supporting Domain Experts in Software Development.” IEEE Software 26 (5): 37–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2009.134.

- Frawley, Jessica Katherine, and Laurel Evelyn Dyson. 2014. “Animal Personas: Acknowledging Non-Human Stakeholders in Designing for Sustainable Food Systems.” In Proceedings of the 26th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference on Designing Futures: The Future of Design, Sydney, Australia, December 2–5, 2014, 21–30.

- Galloway, Annw. 2017. “More-Than-Human Lab: Creative Ethnography after Human Exceptionalism.” In The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography, edited by Larissa Hjorth, Heather Horst, Anne Galloway, and Genevieve Bell, 496–503. London: Routledge.

- Garcia Robles, Ana, Tuija Hirvikoski, Dimitri Schuurman, and Lorna Stokes, eds. 2016. Introducing ENoLL and Its Living Lab Community. Brussels: European Network of Living Labs.

- Giaccardi, Elisa, and Gerhard Fischer. 2008. “Creativity and Evolution: A Metadesign Perspective.” Digital Creativity 19 (1): 19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14626260701847456.

- Grillaert, Katherine, and Samuel Camenzind. 2016. “Unleashed Enthusiasm: Ethical Reflections on Harms, Benefits, and Animal-Centered Aims of ACI.” In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Animal Computer Interaction, Milton Keynes, UK, November 15–17, 2016, 9.

- Hadorn, Gertrude Hirsch, Holger Hoffmann-Riem, Susette Biber-Klemm, Walter Grossenbacher-Mansuy, Dominique Joye, Christian Pohl, Urs Wiesmann, and Elisabeth Zemp, eds. 2008. Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hajjar Leib, Linda. 2011. Human Rights and the Environment : Philosophical, Theoretical and Legal Perspectives. Leiden: Brill.

- Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harder, Marie K., Gemma Burford, and Elona Hoover. 2013. “What Is Participation? Design Leads the Way to a Cross-Disciplinary Framework.” Design Issues 29 (4): 41–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00229.

- Hendriks, Niels, Liesbeth Huybrechts, Karin Slegers, and Andrea Wilkinson. 2018. “Valuing Implicit Decision-Making in Participatory Design: A Relational Approach in Design with People with Dementia.” Design Studies 59 (November): 58–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2018.06.001.

- Hoyer, Wayne D., Rajesh Chandy, Matilda Dorotic, Manfred Krafft, and Siddharth S. Singh. 2010. “Consumer Cocreation in New Product Development.” Journal of Service Research 13 (3): 283–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375604.

- Huybrechts, Liesbeth, Henric Benesch, and Jon Geib. 2017. “Co-Design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 145–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355042.

- Hyysalo, Sampsa, and Mikael Johnson. 2015. “Codesign Journey Planner.” INUSE Research Group. http://codesign.inuse.fi/approaches

- Hyysalo, Sampsa, Mikael Johnson, and Jouni K. Juntunen. 2017. “The Diffusion of Consumer Innovation in Sustainable Energy Technologies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 162: S70–S82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.045.

- Hyysalo, Sampsa, Cindy Kohtala, Pia Helminen, Samuli Mäkinen, Virve Miettinen, and Lotta Muurinen. 2014. “Collaborative Futuring with and by Makers.” CoDesign 10 (3-4): 209–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2014.983937.

- Isokawa, Naohiro, Yuuki Nishiyama, Tadashi Okoshi, Jin Nakazawa, Kazunori Takashio, and Hideyuki Tokuda. 2016. “TalkingNemo: Aquarium Fish Talks Its Mind for Breeding Support.” In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction.” Milton Keynes, UK, November 15–17, 2016.

- Ives, Christopher D., David J. Abson, Henrik von Wehrden, Christian Dorninger, Kathleen Klaniecki, and Joern Fischer. 2018. “Reconnecting with Nature for Sustainability.” Sustainability Science 13 (5): 1389–1397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9.

- Jackson, Tim, Wanger Jager, and Sigrid Stagl. 2004. “Beyond Insatiability – Needs Theory, Consumption and Sustainability.” In The Ecological Economics of Consumption, edited by Lucia Reisch and Inge Røpke, 79–110. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.4337/9781845423568.00013.

- Jørgensen, Ida Kathrine Hammeleff, and Hanna Wirman. 2016. “Multispecies Methods, Technologies for Play.” Digital Creativity 27 (1): 37–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2016.1144617.

- Kanstrup, Anne Marie. 2017. “Living in the Lab: An Analysis of the Work in Eight Living Laboratories Set up in Care Homes for Technology Innovation.” CoDesign 13 (1): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2016.1146304.

- Kensing, Finn, and Joan Greenbaum. 2012. “Heritage: Having a Say.” In Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design, edited by Jesper Simonsen and Toni Robertson, 21–36. New York: Routledge.

- Keshavarz, Mahmoud, and Ramia Mazé. 2013. “Design and Dissensus: Framing and Staging Participation in Design Research.” Design Philosophy Papers 11 (1): 7–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/089279313X13968799815994.

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions.

- Kohtala, Cindy, Sampsa Hyysalo, and Jack Whalen. 2020. “A Taxonomy of Users’ Active Design Engagement in the 21st Century.” Design Studies 67 (March): 27–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2019.11.008.

- Kotzé, Louis J. 2014. “Human Rights and the Environment in the Anthropocene.” The Anthropocene Review 1 (3): 252–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019614547741.

- Kristensson, Per, and Peter R. Magnusson. 2010. “Tuning Users’ Innovativeness during Ideation.” Creativity and Innovation Management 19 (2): 147–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8691.2010.00552.x.

- Kristensson, Per, Peter R. Magnusson, and Jonas Matthing. 2002. “Users as a Hidden Resource for Creativity: Findings from an Experimental Study on User Involvement.” Creativity and Innovation Management 11 (1): 55–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8691.00236.

- Kujala, Sari. 2003. “User Involvement: A Review of the Benefits and Challenges.” Behaviour & Information Technology 22 (1): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290301782.

- Lam, David P. M., Elvira Hinz, Daniel Lang, Maria Tengö, Henrik Wehrden, and Berta Martín-López. 2020. “Indigenous and Local Knowledge in Sustainability Transformations Research: A Literature Review.” Ecology and Society 25 (1): 3. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11305-250103.

- Lee, Yanki. 2008. “Design Participation Tactics: The Challenges and New Roles for Designers in the Co-Design Process.” CoDesign 4 (1): 31–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875613.

- Lenskjold, Tau Ulv, Sissel Olander, and Joachim Halse. 2015. “Minor Design Activism: Prompting Change from Within.” Design Issues 31 (4): 67–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00352.

- Lundström, Anette, Jussi Savolainen, and Emma Kostiainen. 2016. “Case Study: Developing Campus Spaces through Co-Creation.” Architectural Engineering and Design Management 12 (6): 409–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17452007.2016.1208077.

- Lyle, John Tillman. 1996. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mancini, Clara, Rob Harris, Brendan Aengenheister, and Claire Guest. 2015. “Re-Centering Multispecies Practices: A Canine Interface for Cancer Detection Dogs.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, April 18–23, 2015, 2673–2682.

- Mankoff, Demi, Anind Dey, Jennifer Mankoff, and Ken Mankoff. 2005. “Supporting Interspecies Social Awareness: Using Peripheral Displays for Distributed Pack Awareness.” In Proceedings of the 18th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Seattle, WA, October 23–26, 2005, 253–258.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.” Psychological Review 50: 370–396. Republished online: https://www.researchhistory.org/2012/06/16/maslows-hierarchy-of-needs/

- Mathews, Freya. 2006. “Beyond Modernity and Tradition: A Third Way for Development.” Ethics & the Environment 11 (2): 85–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/ETE.2006.11.2.85.

- Mathews, Freya. 2008. “Thinking from within the Calyx of Nature.” Environmental Values 17 (1): 41–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.3197/096327108X271941.

- Mathews, Freya. 2010. “On Desiring Nature.” Indian Journal of Ecocriticism 3: 1–9.

- Mathews, Freya. 2011. “Towards a Deeper Philosophy of Biomimicry.” Organization & Environment 24 (4): 364–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026611425689.

- Mattelmäki, Tuuli, Eva Brandt, and Kirsikka Vaajakallio. 2011. “On Designing Open-Ended Interpretations for Collaborative Design Exploration.” CoDesign 7 (2): 79–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2011.609891.

- Mattelmäki, Tuuli, and Froukje Sleeswijk Visser. 2011. “Lost in Co-X: Interpretations of Co-Design and Co-Creation.” In Diversity and Unity, Proceedings of IASDR2011, the 4th World Conference on Design Research, Volume 31, Delft, The Netherlands, October 31–November 4, 2011.

- Maturana, Humberto R., and Francisco J. Varela. 1980. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

- Max-Neef, Manfred A. 1989. Human Scale Development: Conception, Application and Further Reflections. New York: Apex Pr.

- Mitchell, Val, Tracy Ross, Andrew May, Ruth Sims, and Christopher Parker. 2016. “Empirical Investigation of the Impact of Using Co-Design Methods When Generating Proposals for Sustainable Travel Solutions.” CoDesign 12 (4): 205–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1091894.

- Parker, Peter, and Staffan Schmidt. 2017. “Enabling Urban Commons.” CoDesign 13 (3): 202–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355000.

- Pedersen, Jens. 2016. “War and Peace in Codesign.” CoDesign 12 (3): 171–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2015.1112813.

- Piitulainen, Roosa, and Ilyena Hirskyj-Douglas. 2020. “Music for Monkeys: Building Methods to Design with White-Faced Sakis for Animal-Driven Audio Enrichment Devices.” Animals 10 (10): 1768. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10101768.

- Plessis, Chrisna du. 2012. “Towards a Regenerative Paradigm for the Built Environment.” Building Research & Information 40 (1): 7–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2012.628548.

- Pschetz, Larissa, and Michelle Bastian. 2018. “Temporal Design: Rethinking Time in Design.” Design Studies 56: 169–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2017.10.007.

- Ripple, William J., Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Mauro Galetti, Mohammed Alamgir, Eileen Crist, Mahmoud I. Mahmoud, William F. Laurance, and 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries. 2017. “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice.” BioScience 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix125.

- Ritvo, Sarah E., and Robert S. Allison. 2014. “Challenges Related to Nonhuman Animal-Computer Interaction: Usability and ‘Liking’.” In Proceedings of the 2014 Workshops on Advances in Computer Entertainment Conference, Funchal, Portugal, November 11–14, 2014.

- Robinson, Charlotte, and Alice Torjussen. 2020. “Canine Co-Design: Investigating Buttons as an Input Modality for Dogs.” In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Eindhoven, Netherlands, July 6–10, 2020, 1673–1685. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3357236.3395462.

- Roser, Thorsten, Alain Samson, Patrick Humphreys, and Eidi Cruz-Valdivieso. 2009. New Pathways to Value: Co-Creating Products by Collaborating with Customers. London: LSE Enterprise.

- Rupprecht, Christoph D. D., Joost Vervoort, Chris Berthelsen, Astrid Mangnus, Natalie Osborne, Kyle Thompson, Andrea Y. F. Urushima, et al. 2020. “Multispecies Sustainability.” Global Sustainability 3: e34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.28.

- Sanders, Elizabeth, and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Sandler, Roland. 2018. Environmental Ethics: Theory in Practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schultz, Tristan, Danah Abdulla, Ahmed Ansari, Ece Canlı, Mahmoud Keshavarz, Matthew Kiem, Luiza Prado de O Martins, and Pedro J. S. Vieira de Oliveira. 2018. “What Is at Stake with Decolonizing Design? A Roundtable.” Design and Culture 10 (1): 81–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2018.1434368.

- Seravalli, Anna, Mette Agger Eriksen, and Per-Anders Hillgren. 2017. “Co-Design in Co-Production Processes: Jointly Articulating and Appropriating Infrastructuring and Commoning with Civil Servants.” CoDesign 13 (3): 187–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355004.

- Simonsen, Jesper, and Toni Robertson. 2012. Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design. London: Routledge.

- Steen, Marc. 2011. “Tensions in Human-Centred Design.” CoDesign 7 (1): 45–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2011.563314.

- Steen, Marc. 2013. “Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination.” Design Issues 29 (2): 16–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/DESI_a_00207.

- Steen, Marc, Menno Manschot, and Nicole De Koning. 2011. “Benefits of Co-Design in Service Design Projects.” International Journal of Design 5 (2): 53–60.

- Taffe, Simone. 2015. “The Hybrid Designer/End-User: Revealing Paradoxes in Co-Design.” Design Studies 40: 39–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2015.06.003.

- Thomas, Vanessa, Christian Remy, and Oliver Bates. 2017. “The Limits of HCD: Reimagining the Anthropocentricity of ISO 9241-210.” In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Computing within Limits, Santa Barbara, CA, June 22–24, 2017, 85–92.