Abstract

This paper makes the case that a Pluriversal Social Design should be desire-based. It suggests that the creation of meaningful social change requires moving the focus of design processes from needs to agentic desires. The author understands agentic desire as the creative impulse towards human flourishing. In social design, the current emphasis on needs makes designers continually reproduce the Eurocentric model of life, hindering the creation of genuine alternatives. Moreover, centering collaborative relationships (designing with) on people’s basic needs is often disempowering. Desire-based design is a transformative practice that aims to break with normalcy and orthodoxy (i.e. the familiar way of doing things) to create and recognize alternatives. In the typical process, the designer starts with a need or problem and looks for a desirable solution. This paper suggests the opposite, engaging with desire as a starting point, in an open-ended exploration, and emphasizing people’s agency.

1. Introduction

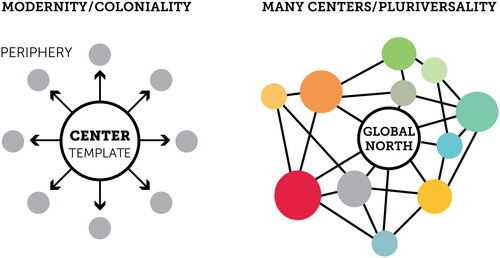

This paper makes the case that a Pluriversal Design – a form of social design that aims to contribute to the construction and blossoming of other worlds – is inherently desire-based. The Pluriverse, “a world where many worlds fit,” is a concept proposed by the Zapatista movement and popularized by Arturo Escobar (Citation2018). But what is necessary to create a world of many worlds ()? Applied to design practice and research, my suggestion is: changing the focus of the design process from needs to desire. I understand desire as the expression of the creative impulse towards human flourishing. Desire refers to being awakened, excited, energized, eager, ready to act. That is the force that can make genuine change happen.

In the field of social design, when we want to create meaningful social change and allow for communities from Other Centers to flourish, needs-based approaches are not enough. We must engage with desire as the starting point of the design process. Desire-based design is a transformative practice that aims to break with normalcy and orthodoxy (i.e. the familiar way of doing things) in order to create and recognize alternatives. In the typical process, the designer starts with a need or problem and looks for a desirable solution. I suggest the opposite: that we engage with desire as a starting point and then, subsequently, investigate what is needed for its manifestation.

Please note, I do not suggest ignoring human needs. On the contrary, a perceived need is the wake-up call that triggers the desire to create something that could change the situation. Moreover, my proposition does not apply to all fields of design; e.g. healthcare design and inclusive design appropriately emphasize needs.

My proposition is inspired by conversations with many Indigenous and Afro-descendant knowledge keepers as well as by the work of several authors from Other Centers (i.e. the Global South) – mainly Audre Lorde and Eve Tuck – who had a significant impact on my understanding of the creative force of desire. My main references from the Global North were the design theorists Harold Nelson and Erik Stolterman.

I write this paper as a social design researcher and practitioner with considerable experience in collaborative projects with Indigenous communities in Brazil and Canada. I also write it as a woman born and raised in Brazil who has lived in North America for the last fifteen years. And I write to other designers who are involved or wish to collaborate with communities at the margins of the modern world and contribute to their blossoming. This paper is aimed at designers from the Global North who are not necessarily familiar with the work of authors of color and from the Global South. For this reason, it weaves together knowledge from the South and the North, starting by framing the issues in a manner that is familiar to designers from the Global North and, subsequently, focusing on the insights of authors from the Global South.

2. A Brief Introduction to Social Design

Design, as a professional field, emerged in the context of planning industrial reproduction in the modern world. Design, therefore, is deeply linked with the capitalist way of life and consumerism. In the last four decades, however, designers have proposed ways to harness their abilities for social ends. This wish to do good gave rise to a new field of design practice: Social Design (DiSalvo et al. Citation2011).Footnote1 It can be broadly defined as the use of design to address complex social problems and contribute to social change (Janzer and Weinstein Citation2014). Can the wish to do good really do good? Social Design initiatives and methods have been criticized by scholars and practitioners from the Global South (Tunstall Citation2013), but the voice that stirred controversy in the Global North was Bruce Nussbaum’s, with his article “Is Humanitarian Design the New Imperialism?” “Are designers the new anthropologists or missionaries, come to poke into village life, ‘understand’ it and make it better–their ‘modern’ way?” (Nussbaum Citation2010, 1). Since then, the association of social design with imperialism and neo-colonialism has been discussed by many designers and scholars (e.g. Akama et al. Citation2019, Janzer and Weinstein Citation2014; Light Citation2019; Moran, Harrington, and Sheehan Citation2018; Taboada et al. Citation2020). And yet, the question of how to bring the principles of decoloniality and pluriversality to tangible reality remains.

One of the main critiques is that social designers, armed with toolkits, parachute into local communities with reduced knowledge of “the macro and micro political, economic, and cultural systems that contribute to the issues and ills that social design seeks to change” (Janzer and Weinstein Citation2014, 330). Another critique is that they address only the symptoms of deeper structural problems, often by producing “techno-fixes” (Segal Citation2017). As a result, in many cases, the communities do not adopt the “solution” proposed by the designers (Martin Citation2016; Nussbaum Citation2010).

Even though Social Design presents itself as a participatory process with communities and not for communities, there is little clarity about what it means to design with. For instance, there is a tendency to disregard the expertise and innovation of local informal “designers” (e.g. carpenters, blacksmiths).

Negating the power of “lay designers,” is arguably at the cost of the relevance of the final design to those who are intended to use it. This is nowhere more evident than in so-called developing contexts, where people have always been driven to design and innovate due to inequality, poverty, and unmet needs. Too often in such contexts, professional designers develop solutions that are inappropriate for the intended users […]. Although human-centered design is participatory, the focus is on understanding users and their context rather than exploring how people are already designing to meet their own needs. (Campbell Citation2017, 30–1)

I recognize that social designers have been addressing the critiques and maturing the methods and practices of the field; for instance, by proposing long-term involvement with the communities and giving attention to grassroots innovations. As Heller (Citation2018) argues, social design is a work in process. This paper is my contribution to reframing its practices.

3. What’s Wrong with Needs-Centered Approaches?

Sometimes my arguments against needs-centered design rub people the wrong way. “What about the basic needs (water, food, and shelter)?” A dear friend ranted: “we cannot ignore there are real baseline needs; Maslow did not make them up!” Yes, they exist. I am very aware of them as a person born and raised in the Global South. The issue here is how we can significantly improve people’s quality of life and what the field of social design can actually do. Welfare programs can be crucial to people in extreme poverty. Social design, however, is not a welfare program or charity; it is based on collaborative relationships, creating new social conditions with the communities and not for them (Heller Citation2018). I argue that it is detrimental and disempowering to center collaborative relationships (designing with) on people’s basic needs.

It is important to make a distinction between critical and chronic problems. People facing critical situations – e.g. caused by an earthquake, flood, drought, massacre, and so on – have urgent and vital basic needs in terms of food, shelter, clothes, and personal products. This paper, however, is not about responding to critical situations; it is about the means to create social change with the contribution of design, transforming conditions that keep communities in chronic distress.

Some people argue: “but these communities have many needs!!!” Indeed they have. But by focusing on their (perceived) deficits, designers may lose sight of their assets, intelligence, creativity, agency, and projects. In South America, we see again and again communities struggling with the two lowest levels of Maslow’s needs (Citation1943) creating innovative projects. Arturo Escobar (Citation2018, Citation2020) developed his framework of the Pluriverse inspired by the life projects and movements of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and peasant communities in Latin America, many of which were created amid hideous violence and poverty. Once more, I am not suggesting that those communities do not need external resources. On the contrary, even Bruno Barras (leader of the Yshiro-Ebitoso people in Paraguay, who proposed the concept of “life-projects” instead of “development projects”) affirms: “For us to carry on this life project we need the respectful support of donors and financing institutions from the North” (Barras Citation2004, 51). This “respectful support” is a support that recognizes their agency, knowledge, creativity, desires, and visions for the future (Blaser Citation2004).

When Margolin and Margolin (Citation2002) proposed a “Social Model” of Design, they stated that social design education must draw on other disciplines, such as social work, sociology, anthropology, and public policy. It would also be essential to study the past mistakes and controversies of such fields (Janzer and Weinstein Citation2014). Pertinent to this paper is the controversy between basic needs and capability approaches.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Basic Needs approach (BNA) was popular in development policy (Crosswell Citation1978; Ghosh Citation1984; Reinert Citation2018). As the name suggests, it prioritized meeting people’s basic needs. BNA was subject to many criticisms and gradually supplanted by the capability approach, founded by the Indian economist and Nobel Prize laureate Amartya Sen (Reader Citation2006).Footnote2 Sen is known for his studies on the causes of famines, having witnessed, as a child, the Great Bengal famine of 1943, which killed 3 million people (Sen Citation1981). Sen (Citation1990) criticized BNA because of its reliance on commodities and arbitrariness that disrespects local culture and ways of life. Beyond water, who decides which needs are basic and how to meet them (Alkire Citation2002)? Moreover, as BNA aimed at providing people with a basic set of commodities, it also gave the impression that poverty elimination was an easy task; i.e. once the basic needs were met, people could thrive. Unfortunately, this was not the case. Escobar (Citation2012) examines the apparently straightforward problem of hunger by asking: “when people are hungry, is not the provision of food the logical answer?” And yet he explains, paradoxically, “strategies implemented to deal with the problems of hunger and food supply, far from solving them, have led to their aggravation” (Escobar Citation2012, 104). In many contexts, providing people with standardized goods or food led to disabling dependence on the outside world to meet their most basic needs (Guindon Citation2015; Kirmayer, Tait, and Simpson Citation2009; Manzini Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2009).

The capability approach is concerned with enabling people to meet their basic needs but recognizes that poverty is complex and multidimensional (Alkire Citation2002; Sen Citation1981). Manzini explains the basic idea behind it: “instead of considering people as carriers of needs to be satisfied (by someone or something), it is better to consider them as active subjects, able to operate for their own well-being” (Manzini Citation2015, 96). Capabilities are people’s real freedoms to enjoy valuable lives; to lead the kind of life they value and have reason to value (Alkire Citation2009). Sen (Citation1999) argued that it would be wrong and have disastrous consequences to consider that poverty is merely a question of lack of material resources. For him, ultimately, what the poor are denied is their human fulfillment.

While basic-needs-centered interventions treat people as passive beneficiaries, the capability approach is agency-focused. Sen (Citation1999) defines agency as what a person is free to do and achieve in pursuit of whatever goals or values they regard as important. In other words, agency refers to the ability of an individual or a group to set their own goals and act upon them (Kabeer Citation2001). As Sen puts it:

The people have to be seen in this perspective, as being actively involved – given the opportunity – in shaping their own destiny, and not just as passive recipients of fruits of cunning development programs. The state and the society have extensive roles in strengthening and safeguarding human capabilities. This is a supporting role, rather than one of ready-made delivery. (Sen Citation1999, 53)

3.1. Needs-Centered Society and Capitalist Modernity

In his book, Towards a History of Needs (1977), Ivan Illich explained the profound interdependence between needs and capitalist modernity. For him, the manipulation of needs, by means of the disseminated belief that human needs can be satisfied by standardized goods and services, is a necessary condition and the fuel of the capitalist market-intensive system. For Illich, industrialization reorganized society around professionally defined needs, problems, and solutions. “At present, we see consumer goods and professional services at the center of our economic system, and specialists relate our needs exclusively to this center” (Illich Citation1977, 16). As Manzini explains:

Twentieth-century modernity has led us to an idea of well-being as liberation from the weight of everyday activities, where our own skills and capabilities are replaced by a growing series of products and services to be purchased on the market or received from the state […] people who are induced to seek well-being in the passive, individual satisfaction of their own needs and desires are needy in all respects, but everything they need must be purchased, and to purchase it they need more money. Thus they must work more. The end result is a vicious circle. (Manzini Citation2015, 95)

In the modern world, we have a predefined menu of goods and services that we should need. An essential part of the system is to offer numerous choices within this predefined menu as the engine for ever-growing consumption. The menu is ever-evolving and always changing with fashion and technological advancements. Most contemporary design activities involve creating new options for the menu. The ever-evolving menu gives consumers the impression they are exercising their desires by choosing among the options. Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 109) argue that “a created need is an imposed desire. It is a faux desire, which originates outside the individual’s own generative nature.” I conceptualize the externally predefined desires (related to the market’s menu) as passive desires, in contrast to the intrinsic desires, which tend to be agentic.

The emphasis on professionally defined needs is also a powerful tool of forced cultural assimilationFootnote3 and oppression of non-Western peoples. Imputed needs are not only normative and homogenizing but also create cycles of dependency on outsiders.

A couple of so-called development decades have sufficed to dismantle traditional patterns of culture from Manchuria to Montenegro. Prior to these years, such patterns permitted people to satisfy most of their needs in a subsistence mode. After these years, plastic had replaced pottery, carbonated beverages replaced water, Vallium replaced chamomile tea, and records replaced guitars. (Illich Citation1977, 9)

In my Masters and PhD research (Leitão Citation2011, Citation2017), I worked with communities that went through this process in the second half of the twentieth century. The Caiçaras of Guaraqueçaba (Brazil) were suddenly thrown into the money economy in the 1990s when environmental policies restricted their subsistence practices. Thus, they started to need money to buy plastic and other industrialized goods to replace objects they once produced from their lands’ natural resources (Leitão Citation2011). The Atikamekw Nehirowisiw (Quebec, Canada) – traditionally a semi-nomadic people whose ways of life were intimately linked with the land – saw their territory change drastically over the last century due to railways, hydroelectric dams, and intensive natural resource exploitation by non-Atikamekw entities (Jérôme Citation2010). In the 1970s, with the disintegration of the conditions for their way of life, they started to live permanently in reserves, where they could receive the government’s standardized services (Jacques Newashish, personal communication). Similar processes were widespread. Modernity/coloniality and its multiplication of imputed needs turned Indigenous peoples (who live autonomously from the land) into poor peoples (assisted by external professional services and resources) (Guindon Citation2015; Viveiros de Castro Citation2017).

As development, or modernization, reached the poor – those who until then had been able to survive in spite of being excluded from the market economy – they were systematically compelled to buy into a purchasing system which, for them always and necessarily meant getting the dregs of the market. Indians in Oaxaca who formerly had no access to schools are now drafted into school to “earn” certificates that measure precisely their inferiority relative to the urban population. Furthermore – and this is again the rub – without this piece of paper they can no longer enter even the building trades. Modernization of “needs” always adds new discrimination to poverty. (Illich Citation1977, 11–12)

In this kind of approach, people “experience as a lack that which the expert imputed to them as a need” (Illich Citation1977, 29). The consequence is not only increasing passivity and disempowerment but also reduced self-respect and well-being. “Sources that draw on poor people’s own perceptions of their situation often report that a lack of agency is central to their description of ill-being” (Ibrahim and Alkire Citation2007, 383). How could social design methods support human fulfillment and agency instead of addressing imputed needs? I argue that we should develop approaches that embrace agentic desire as a starting point.

3.2. Damage-Centered Research vs Desire-Based Research

In 2009, North American Indigenous scholar Eve Tuck asked Indigenous communities, scholars, and educators to consider the negative long-term impact of what she calls “damage-focused research” (Tuck Citation2009). Tuck is particularly concerned with research that invites oppressed peoples to speak but only speak about their pain, problems, and struggles. Damage-centered research is embedded in some social design methods under the name of empathy.Footnote4

Tuck argues that this kind of research unintentionally pathologizes local communities, operating under a flawed theory of change that reinforces a one-dimensional notion of Indigenous people as depleted and broken. For her, this “theory of change is flawed because it assumes that it is outsiders, not communities, who hold the power to make changes” (Tuck Citation2010, 638). Tuck (Citation2009) recognizes that there was a time and place for damage-centered approaches that exposed the uninhabitable, inhumane conditions in which Indigenous people lived and continued to live. However, in her conversations with Indigenous elders, “they agree that a time for shift has come, that damage-centered narratives are no longer sufficient” (Tuck Citation2009, 415–416). The shift suggested by Tuck is to craft research to capture desire instead of damageFootnote5:

I submit that a desire-based framework is an antidote to damage-centered research. An antidote stops and counteracts the effects of a poison, and the poison I am referring to here is not the supposed damage of Native communities, urban communities, or other disenfranchised communities but the frameworks that position these communities as damaged. (Tuck Citation2009, 416).

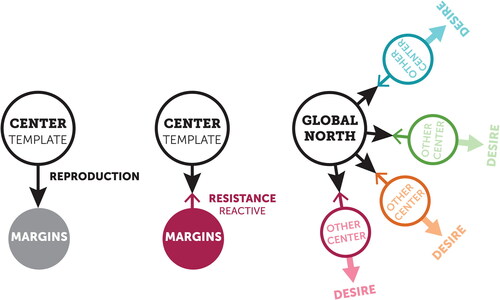

Tuck also suggests that desire may interrupt the binary of reproduction of social inequity versus resistance: “Desire is a thirding of the dichotomized categories of reproduction and resistance” (Tuck Citation2009, 419). As modernity was disseminated throughout the globe, it created an uneven relationship between center and periphery in which the Center of Modernity (the Global North) is the template for the rest of the world (). It is important to note that the Center and periphery are integral parts of the same Eurocentric model. In other words, the commodity-addicted, market-intensive modern society only exists because peoples from the periphery have been exploited and expropriated.

Figure 2 The dichotomy reproduction vs. resistance and the third force (desire). The first two arrows (reproduction and resistance) are aligned with Modernity: one says “yes” and the other says “no.” Desire creates a third force, a new alternative. The third arrow can go to multiple directions.

The periphery can resist the model of the Center and has resisted for centuries. I can only discuss the possibility of a world of many worlds because of the peoples who resisted colonization and assimilation. Resistance is established as an opposition to the Center, forming a dichotomy. Even though it can prepare the ground for creative action, resistance is a reactive force. The way out of the dichotomy is through the creation and recognition of new possibilities and multiple models of life, thus creating the future by design. Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 110) suggest that desire “is the destabilizing trigger for transformational change, which facilitates the emergence of new possibilities and realizations of human ‘being.’”

4. Needs-Centered Design and Desire-Based Design

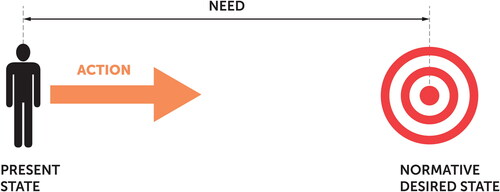

If our goal is to produce significant social change by design, we must develop desire-based approaches. By focusing on needs and problems at the start, and not on desire, we are merely reproducing the world as we know it with a few minor tweaks. Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 110) state that addressing needs involves an entirely different process than creating a world not yet seen:

A need is a baseline condition that must be mitigated in order to support and stabilize a given situation. The hungry need to be fed and the cold need to be sheltered – but people desire to be more than “needy” creatures.

The difference between the [normative] desired state and the actual state is framed as the problem. It is also assumed that there is no difficulty in determining the needs that must be satisfied in order to realize the desired state […]. Needs-based design is found on the erroneous assumption that a need or problem is easily discerned […]. A needs-based change, animated through a problem-solving approach, assumes that the right outcome is known from the start. (Nelson and Stolterman Citation2012, 110, my emphasis)

This outcome-known-from-the-start is a preformed normative desired state. In short, needs refer to the distance between the current situation and a normative desired situation (). Why do people assume that a need is easily discerned? According to Illich (Citation1977), it is because we live in an era of professionally defined and imputed needs.

Figure 3 In a needs-centered approach, need refers to the distance between the present state and the normative preformed desirable state.

A desire-based approach, on the other hand, is open-ended. “A desire-based change process leads to a desired outcome but does not start with that outcome neatly in place” (Nelson and Stolterman Citation2012, 110). This open-endedness is what facilitates the emergence of new possibilities. In a similar vein, Heller (Citation2018, 33) affirms that creating is not the same as solving problems:

Most of the time, problems are framed around the symptoms experienced: something is wrong or broken, and there is a desire to fix it or make it go away. But whenever human behavior is involved, there are invisible forces that cause the symptoms observed. Usually, focusing on making the problem go away brings only temporary relief. One symptom is eliminated only to have another appear in its place. Problem solving traps us in circles, chasing our tails, using the same level of thinking that produced the problem in the first place […] Creating requires bigger and newer thinking and vision with enough merit to become a North Star for all involved. It demands new questions and answers, fostering open-ended thinking about possibilities rather than acceptance of the way things are.

For Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 111), “desire can be understood as the ‘force’ that provides us with intrinsic guidance and energy.” It is important to stress the term “force” because desire is neither a thing nor a preformed image; desire is about built-in orientation. They suggest a close relationship between desire and intention. Intention should be understood “as the aiming and subsequent emergence of a desired outcome”:

One of the key concepts concerning intention arose in the philosophic discourse of the Middle Ages. At that time, the idea of aim, as in aiming an arrow, became central to the unfolding meaning of intention. That is, that intention is not the target, not the outcome, not the purpose, nor an end state, but is principally the process of choosing or giving direction to effort. (Nelson and Stolterman Citation2012, 113)

A desire-based approach is open-ended, as the transition towards a Pluriverse is an open-ended transition. Metaphorically, desire-based social change can be seen as trailblazing with the help of a compass ().

In terms of creating new possibilities of life, what is the final result? We do not know yet; we will be creating a world that has never been seen before. We have to learn to live with uncertainty, knowing that we follow the compass of desire but not yet seeing the final result, which is the ultimate creative (and not reproductive) mode.

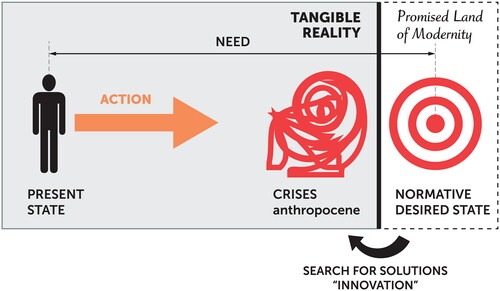

4.1. The Promised Land of Modernity

Social Design often involves collaborations across the Global North and the Global South. And here, the preconceived definitions of what-is-desirable become particularly problematic. Since the colonial expansion of the sixteenth century, Western EuropeFootnote6 (and subsequently North America) has positioned itself as the Center of the World (Dussel Citation1993). Features of the European civilizational model (known as modernity) have been considered as universal or universally desirable (Hall Citation1992).

In the hegemonic worldview, the ultimate normative desired outcome is a given: the market-intensive Eurocentric model of life (but in a hypothetical sustainable version). The utopian idea that super-efficient technology can solve all the problems (even the environmental crises) and promote an ever-increasing level of well-being is one of the founding myths of modernity (Leitão Citation2018; Walker Citation2010). Even though this utopia is unattainable and unsustainable, capitalist modernity spreads promises that the rest of the world will be better off by adopting its cultural model:

Under the spell of neo-liberalism and the magic of the media promoting it, modernity and modernization, together with democracy, are being sold as a package trip to the promised land of happiness. (Mignolo Citation2007, 450)

Escobar (Citation2012) remarks that the desirability of this model of life is never questioned. This pre-constructed desire – the idealized promised land of modernity – is disseminated throughout the planet by mass media such as images, literature, and cinema. This representation of modernity as the ultimate desirable acquired such a status of certainty that it seems almost impossible to imagine the social reality in other terms ().

Figure 5 The Promised Land of Modernity is a mirage. As humanity aligns its actions with this model, the Anthropocene and devastating crises are brought into reality. In a problem-solving and needs-based frame of mind, the problem is framed as the difference between the normative desired and the actual state, and not as our alignment with an unsustainable normative conception of what-is-desirable. Our imagination is funneled down to the creation of techno-fixes in attempts to conform reality to the idealized model.

In this frame of mind, we are not creating the future by design, as we already know the supposed point of arrival. Creativity is limited to the design of techno-fixes, mere attempts to fix the “glitches” of modernity (Huesemann and Huesemann Citation2011). Even as we recognize that modernity is unsustainable, we keep designing band-aids instead of being open to new definitions of the ultimate desirable (Ehrenfeld Citation2008).

In 1977, Illich had predicted that dependence on commodities for passive consumption would atrophy creative human action. Relying on needs means that the desired state is pre-defined and not actively created. I believe one of the causes of the reliance on needs is the vilification of desire as a creative force.

5. Defining Desire and Desire-Based Approaches

I understand desire as the expression of the creative impulse towards human flourishing. Desire, however, is a very controversial word, often receiving negative or sexual (therefore shameful) connotations. It may denote a longing, a lack, an assemblage, or a psychological structure. Several definitions of desire refer to cravings of pleasure, material goods, or recognition, associating desire with lust and greed. Tuck (Citation2010, 636) even wrote a paper disputing Gilles Deleuze’s conceptualization of desire: “I wanted him to say that desire is smart, is wise. Agentic. Though I looked and looked for some indication from him that he recognized desire as insight/ful, the recognition is not there.” In my life, I also understand and experience desire as agentic and wise.

As mentioned, Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 111) define desire as the “force” that provides us with intrinsic guidance and energy; they state that, in our culture, “desires are often treated as low-level needs—things that we wish but could live without.” Desire is seen as superfluous, and, examining capitalist society, indeed it is. As people allowed an external definition of value and need to guide them, this creative force became irrelevant.

Even negative connotations of the term desire shed light on the conditions for significant social change. Some conceptions of desire stress the suffering that the feeling of lack brings. However, the sense of lack or incompletion is part and parcel of the human experience. Paulo Freire argues that human beings feel inherently incomplete; he describes men and women as historical beings; that is, “as beings in the process of becoming – as unfinished, uncompleted beings in and with a likewise unfinished reality” (Freire 2005, 84). From this feeling of incompletion, lack, or dissatisfaction emerges the desire for change that is the trigger to design. Our yearning for completion makes humans creative beings who create things and act upon the world to transform it. For Freire, people “infusing the world with their creative presence by means of the transformation they effect upon it – unlike animals, not only live but exist; and their existence is historical” (Freire 2005, 98). Even though it can be uncomfortable, the feeling of incompletion is fundamental to any creation and change process.

Modernity is so seductive because it proposes eliminating this discomfort with the promise that a product or a service can fulfill your dreams and make you happier (Walker Citation2010). Why engage with the uneasy feeling of incompletion that propels us to create if we can buy a product or pay for a service? This promise is pure snake oil; it exists to tame our agentic creative impulses with passive wants and addictive consumerism.

5.1. Desire as a Corporeal Force: Eros and the Erotic

An agentic desire is an idea that energizes me. I understand desire as a bodily force related to motivation and enjoyment of action. We all recognize the feelings in our bodies: what makes our heart sing, what puts a smile on our lips, what turns us on. Through the action of desire, we recognize what is worth living for, what is valuable for us, instead of following external definitions of what we should value. Briefly, for me, desire is the force that turns us on; and yes, this expression can also have a sexual connotation. It seems that a veil of shame conceals human’s most creative impulse.

Desire is not only a mental construction but has a bodily dimension, as the human vital life force, Eros. Eros directs us to flourish, as flowers are an expression of Eros in the plant kingdom. And here, I refer to that which Black feminist Audre Lorde names as the Erotic. For Lorde, the Erotic is an assertion of the lifeforce of women. I use the term desire to refer to the life force’s expression in both women and men. Lorde argues that Western society has vilified, abused, and devalued the Erotic, relegating it to the bedroom or pornography. By doing so, people live outside themselves, following external directives instead of the guidance of desire. “When we live away from those erotic guides from within ourselves,” Lorde writes, “then our lives are limited by external and alien forms, and we conform to the needs of a structure that is not based on human need, let alone an individual’s” (Lorde Citation2006, 90, my emphasis).

Lorde explains that we have been raised to fear the “yes” within ourselves. Listening to the guidance of desire requires listening to our embodied wisdom. I know firsthand what Lorde is talking about since the erotic cannot be felt secondhand. With time, I learned to listen to the deep “yes” within and trust it as my wisest inner compass:

Beyond the superficial, the considered phrase, “It feels right to me,” acknowledges the strength of the erotic into a true knowledge, for what that means is the first and most powerful guiding light toward any understanding. […] The erotic is the nurturer or nursemaid of all our deepest knowledge. (Lorde Citation2006, 89)

Because it honestly indicates what has value to us, desire can act as an inner compass. The social innovation program Agencia de Redes Para Juventude (Agencia) – created by Marcos Faustini, a theater director born and raised in a favela in Rio de Janeiro – uses the metaphor of desire as a compass quite literally. Working with youth from marginalized backgrounds, one of the program’s initial activities consists in fabricating a compass that points to their desire as their North (Lisboa and Delfino Citation2015). Participants keep that compass at hand throughout the nine months of the program to guide them toward realizing their initial desire. By tapping into their desire, they use creative and drama-based methods to give shape to that desire and, subsequently, create projects that form the early stages of a social enterprise (Peterson Citation2016).

Lorde states that the erotic is connected to our capacity for joy and feeling satisfaction. We harness the physical force of desire when we conceive projects that excite us. This excitement reveals that we have the energy to rise to the challenge and strive to materialize it. Moreover, it shows that we will experience this action as fulfilling. That is why desire is the only energy that can sustain the long-term and intensive engagement necessary to create significant social change. “In order to perpetuate itself,” Lorde argues, “every oppression must corrupt or distort those various sources of power within the culture of the oppressed that can provide energy for change” (Lorde Citation2006, 88–9).

5.2. The Complexity of Desire

Desires are complex and not always good. Therefore, it is important to bring desires to the light and actively engage with them. As Tuck (Citation2009, 420) states, “desire flashes out that which has been hidden or what happens behind our backs.” For Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012), it is important to befriend our desires, to name them and reflect upon them, so we can accept their role in our lives and use them as guidance.

In Agencia’s program, participants are led to befriend their desires as the first step to develop agency (Faustini Citation2014). As already mentioned, participants craft a symbolic compass from their desire. Giving visible shape to their desires allows the participants to refine them to generate projects that might positively impact their communities (Lisboa and Delfino Citation2015). Lisboa and Delfino (Agencia’s coordinators) make a case for using specifically the term “desire” and not dreams or aspirations. They affirm that the realization of dreams can be very distant from the experience of poor youth in the favelas. Desire, on the other hand, being more immediate to their experience, is an invitation to action. For them, the term desire emphasizes agency: what someone is ready to do and create.

When I argue for a desire-based design, I do not suggest inventorying people’s desires and acting on them straight away. First, we must examine, name, and visualize our desires honestly. We can use visual methods, crafts, or drama techniques to allow participants to reflect upon them, discuss their contradictions with other people, and understand the direction towards which their desires are gesturing (Faustini Citation2014; Lisboa and Delfino Citation2015). We must identify the immediate wants involved and distinguish craves and passive (externally defined) desires from agentic desires. The distinction is not by any means clear; sometimes, craves are gesturing towards a deeper impulse. Therefore, working with desires should embrace honesty, complexity, and contradiction (Tuck Citation2009).

Tuck gives the example of this complexity by referring to a group of youth who were critical of capitalism and globalization and yet, at the same time, stood overnight in a long line, waiting for the release of a new sneaker. “We can desire to be critically conscious and desire the new Jordans, even if those desires are conflicting” (Tuck Citation2009, 420). Sometimes what might look like a consumerist crave might be a desire that elevates their imagination and gives them hope. More critical than differentiating positive (right) desires from negative (wrong) ones is paying attention to the potential actions the desire is inspiring and energizing (i.e. how the desire connects with their agency).

It is important to mention that designers sometimes use the expression “creating desirable futures” or “visualizing desirable futures.” Here we are not engaging directly with desire as a force but creating aspirational horizons. When we work with dreams and aspirations, we can keep a needs-based approach, in which the desired final state is pre-defined or defined at the start of the process. A desire-based approach embraces open-ended exploration. To create new possibilities and new futures – that which we do not know yet – we have to combine aspirations with the force of desire. What is the difference? We can have a dream and never act on it. We can create a desirable vision and not know how to take the first step, the second step. Desires, however, are agentic. Desire refers to being awakened, excited, energized, eager, ready to act. That is the force that makes genuine change happen.

6. Conclusion

Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama. (Lorde Citation2006, 91)

This paper is an invitation for social design researchers and practitioners to hone our craft to focus primarily on desire instead of needs when the goal is to create significant social change. By significant, I mean from the point of view of the community that will live with the change. Social change is about enabling communities “outside the Center” to flourish rather than only mitigating their needs. As Nelson and Stolterman (Citation2012, 111) argued, the impulse toward action that arises out of an unfulfilled human need “is completely different from the positive impulse born out of the desire to create situations, systems of organizations, or concrete artifacts that enhance our life experiences.”

One of this paper’s key ideas is the distinction between social design approaches that increase passivity (needs-centered) and approaches that enhance agency and creativity (desire-based). How can social design practice support human fulfillment instead of primarily addressing needs? It asks us to develop approaches and methods that embrace and befriend desires as a starting point of a collaborative project and, subsequently, investigate how to support their manifestation.

If we want to create a world where multiple worlds can flourish, Pluriversal Design is a form of social design that aims to nurture alternative ways of world-making. In this endeavor, I argue that Pluriversal Design is inherently desire-based.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Renata M. Leitão

Renata M. Leitão is an assistant professor in the department of Human Centered Design at Cornell University and an adjunct professor at OCAD University. She is a graphic designer and social justice-focused design researcher with several years of experience in intercultural and collaborative projects with indigenous and marginalized communities. Together with Lesley-Ann Noel, she co-founded and co-leads the DRS Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group and the Pivot Design Conferences. [email protected]

Notes

1 There are many alternative names for this field: Design for Social Innovation, Design for Social Impact, Design for Social Need, Design for Good, and so on.

2 Sen won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1998 for his contributions to welfare economics. The capability approach was further developed by Martha Nussbaum, Sabina Alkire, and many others (Alkire Citation2002; Bockstael and Watene Citation2016).

3 Forced cultural assimilation has been linked to high rates of depression, alcoholism, violence, and suicide in many Indigenous communities (Kirmayer, Tait, and Simpson Citation2009).

4 Empathy, as a human capacity, is fundamental to the work of a designer. However, in many social design methods, it refers to damage or deficit-centered research.

5 Tuck (Citation2009) adds a cautionary note that she is not arguing to install desire as an antonym to damage, as if they were opposites. Instead, her argument for desire refers to an epistemological shift.

6 The European expansion started with Portugal and Spain, followed by Holland, France, and England as the main colonial world players (Hall Citation1992).

References

- Akama, Yoko, Penny Hagen, and Desna Whaanga-Schollum. 2019. “Problematizing Replicable Design to Practice Respectful, Reciprocal, and Relational Co-designing with Indigenous People.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 59–84. doi:10.1080/17547075.2019.1571306.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2002. Valuing Freedoms: Sen’s Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2009. “Concepts and Measures of Agency.” In Arguments for a Better World: Essays in Honor of Amartya Sen. Volume I: Ethics, Welfare, and Measurement, edited by K. Basu and R. Kanbur, 455–474. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Barras, Bruno. 2004. “Life Projects: Development Our Way.” In In the Way of Development: Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects and Globalization, edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit, and Glenn McRae, 47–51. London: Zed Books.

- Blaser, Mario. 2004. “Life Projects: Indigenous Peoples' Agency and Development.” In In the Way of Development: Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects and Globalization, edited by Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit, and Glenn McRae, 26–44. London: Zed Books.

- Bockstael, Erika, and Krushil Watene. 2016. “Indigenous Peoples and the Capability Approach: Taking Stock.” Oxford Development Studies 44 (3): 265–270. doi:10.1080/13600818.2016.1204435.

- Brooks, Sarah. 2001. “Design for Social Innovation: An Interview with Ezio Manzini.” Shareable, July 26. https://www.shareable.net/givmo-a-better-way-to-give-more/

- Campbell, Angus Donald. 2017. “Lay Designers: Grassroots Innovation for Appropriate Change.” Design Issues 33 (1): 30–47. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00424.

- Crosswell, Michael. 1978. Basic Human Needs: A Development Planning Approach. Washington: Agency for International Development.

- DiSalvo, Carl, Thomas Lodato, Laura Fries, Beth Schechter, and Thomas Barnwell. 2011. “The Collective Articulation of Issues as Design Practice.” CoDesign 7 (3-4): 185–197. doi:10.1080/15710882.2011.630475.

- Dussel, Enrique. 1993. “Eurocentrism and Modernity (Introduction to the Frankfurt Lectures).” Boundary 2 20 (3): 65–76. doi:10.2307/303341.

- Ehrenfeld, John R. 2008. Sustainability by Design: A Subversive Strategy for Transforming Our Consumer Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2012. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2020. Pluriversal Politics: The Real and the Possible. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Faustini, Marcus V., ed. 2014. Agência de Redes Para Juventude. Rio de Janeiro: Petrobras.

- Freire, Paulo. 1970/2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Ghosh, Pradip K. 1984. Third World Development: A Basic Needs Approach. Westport: Greenwood Press.

- Guindon, François. 2015. “Technology, Material Culture and the Well-Being of Aboriginal Peoples of Canada.” Journal of Material Culture 20 (1): 77–97. doi:10.1177/1359183514566415.

- Hall, Stuart. 1992. “The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power.” In The Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben, 275–331. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Heller, Cheryl. 2018. The Intergalactic Design Guide: Harnessing the Creative Potential of Social Design. Washington: Island Press.

- Huesemann, Michael, and Joyce Huesemann. 2011. Techno-Fix: Why Technology Won't Save Us or the Environment. Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers.

- Ibrahim, Solava, and Sabina Alkire. 2007. “Empowerment and Agency: A Proposal for Internationally-Comparable Indicators.” Oxford Development Studies 35 (4): 379–403. doi:10.1080/13600810701701897.

- Illich, Ivan. 1977. Toward a History of Needs. Berkeley: Heyday Books.

- Janzer, Cinnamon L., and Lauren S. Weinstein. 2014. “Social Design and Neocolonialism.” Design and Culture 6 (3): 327–343. doi:10.2752/175613114X14105155617429.

- Jérôme, Laurent. 2010. “Jeunesse, musique et rituels chez les Atikamekw (Haute-Mauricie, Québec): ethnographie d'un processus d'affirmations identitaire et culturelle en milieu autochtone.” PhD diss., Université Laval.

- Kabeer, Naila 2001. “Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment.” In Discussing Women's Empowerment—Theory and Practice, edited by Anne Sisask, 17–57. Stockholm: Sida.

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., Caroline L. Tait, and Cori Simpson. 2009. “The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: Transformations of Identity and Community.” In Healing Traditions, edited by Laurence J. Kirmayer and Gail Guthrie Valaskakis, 3–29. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Leitão, Renata M. 2011. “Craftsmanship as a Means of Empowerment for the Traditional Population of Guaraqueçaba: A Case Study.” Master’s thes., Université de Montréal.

- Leitão, Renata M. 2017. “Culture as a Project: Design, Self-Determination and Identity Assertion in Indigenous Communities.” PhD diss., Université de Montréal.

- Leitão, Renata M. 2018. “Recognizing and Overcoming the Myths of Modernity.” In DRS 2018 Conference Proceedings, edited by C. Storni, K. Leahy, M. McMahon, P. Lloyd, and E. Bohemia, 955–966. London: Design Research Society.

- Light, Ann. 2019. “Design and Social Innovation at the Margins: Finding and Making Cultures of Plurality.” Design and Culture 11 (1): 13–35. doi:10.1080/17547075.2019.1567985.

- Lisboa, Ana Paula, and Veruska Delfino. 2015. Dicionário – Agência de Redes Para Juventude. Rio de Janeiro: Avenida Brasil.

- Lorde, Audre. 2006. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” In Sexualities and Communication in Everyday Life: A Reader, edited by K. Lovaas and M. M. Jenkins, 87–91. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Manzini, Ezio. 2015. Design When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Margolin, Victor, and Sylvia Margolin. 2002. “A “Social Model” of Design: Issues of Practice and Research.” Design Issues 18 (4): 24–30. doi:10.1162/074793602320827406.

- Martin, Courtney. 2016. “The Reductive Seduction of Other People’s Problems.” The Development Set (blog). Jan 11, 2016. https://thedevelopmentset.com/the-reductive-seduction-of-other-people-s-problems-3c07b307732d

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1943. “A Theory of Human Motivation.” Psychological Review 50 (4): 370–396. doi:10.1037/h0054346.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2007. “Delinking.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 449–514. doi:10.1080/09502380601162647.

- Moran, Uncle Charles, Uncle Greg Harrington, and Norm Sheehan. 2018. “On Country Learning.” Design and Culture 10 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1080/17547075.2018.1430996.

- Nelson, Harold G., and Erik Stolterman. 2012. The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World. 2nd ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Nussbaum, Bruce. 2010. “Is Humanitarian Design the New Imperialism?” Fast Company’s Co.Design (blog). http://www.fastcodesign.com/1661859/is-humanitarian-design-the-new-imperialism.

- Peterson, Meg. 2016. “From Box-Ticking to Social Impact for Arts-Based Interventions.” The Social Innovation Partnership (TSIP).

- Reader, Soran. 2006. “Does a Basic Needs Approach Need Capabilities?” Journal of Political Philosophy 14 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2006.00259.x.

- Reinert, Kenneth A. 2018. No Small Hope: Towards the Universal Provision of Basic Goods. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Segal, Howard P. 2017. “Practical Utopias: America as Techno-Fix Nation.” Utopian Studies 28 (2): 231–246. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.28.2.0231.

- Sen, Amartya. 1981. Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sen, Amartya. 1990. “Development as Capability Expansion.” In Human Development and the International Development Strategy for the 1990s, edited by K. Griffin and J. Knight, 41–58. London: MacMillan.

- Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taboada, Manuela B., Sol Rojas-Lizana, Leo X. C. Dutra, and Adi VasuLevu M. Levu. 2020. “Decolonial Design in Practice: Designing Meaningful and Transformative Science Communications for Navakavu, Fiji.” Design and Culture 12 (2): 141–164. doi:10.1080/17547075.2020.1724479.

- Tuck, Eve. 2009. “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79 (3): 409–540. doi:10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15.

- Tuck, Eve. 2010. “Breaking up with Deleuze: Desire and Valuing the Irreconcilable.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 23 (5): 635–650. doi:10.1080/09518398.2010.500633.

- Tunstall, Elizabeth. 2013. “Decolonizing Design Innovation: Design Anthropology, Critical Anthropology and Indigenous Knowledge.” In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice, edited by Wendy Gunn, Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, 232–250. London: Bloomsbury.

- UNESCO. 2009. Investing in Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue. UNESCO World Report #2. Paris: UNESCO.

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo 2017. “Os Involuntários Da Pátria: Elogio Do Subdesenvolvimento.” Chão Da Feira – Cadernos de Leitura 65: 1–9.

- Walker, S. 2010. “Sermons in Stones: Argument and Artefact for Sustainability.” Les Ateliers de L'éthique 5 (2): 101–116. doi:10.7202/1044320ar.