Abstract

The design community has made several calls to re-imagine a design education for the future. Here I share a series of visual representations of guiding principles for design curricula that respond to these calls. These sketches were created over several years, exploring visually different objectives for design curricula. In doing the drawings, I wrestle with my own urge to break away from the Ulm-inspired design education of my youth. I created these drawings, often inspired by other images, over several years, as I reflected on design curricula inspired by different contexts: the needs of people in the Global South and of the most “vulnerable” countries (as defined by the United Nations); the pedagogical strategies of Freirean-inspired critical and empowering design education; design education methodologies that mean to promote twenty-first-century skills; design education practices inspired by Latin American decolonial scholars; and, finally, the complexities of pan-African identity. The article acknowledges other examples of decolonial design curricula. While none of the sketches is a complete curriculum, each invites other educators to challenge existing design education paradigms and create culturally relevant curricula for learners in their contexts.

Introduction

I’ve been tinkering with course outlines and curricula, often clumsily, over the last two decades of teaching in academic and non-academic settings. In tinkering, I wanted the curricula to be relevant, situated in the contexts in which I was living and teaching at the time, while still delivering fundamental design principles to students who had little connection to European or North American design histories. Early in my teaching career, I found it comforting to recognize foundational exercises in design that may have been left over from the Bauhausian and Ulmian roots in schools in different parts of the world. But, over time, I began to question the global sameness of the curriculum and acknowledge what is lost when the richness of specific and local design cultures is marginalized and ignored. The sameness erased the cultural specificity that could make learning design more meaningful for students.

I write as someone living at the border of two worlds, a phenomenon alluded to by Mignolo in the introduction of Constructing the Pluriverse (2018). I grew up in the Caribbean and was educated in Trinidad and Tobago and Brazil. I no longer live or work in the Caribbean. I now live and work in the United States, but my mind is preoccupied with all three places all the time. The work that I share in this essay was made in both Trinidad and in North America and reflects this cross-border thinking.

Here I share my visual explorations and reflections about new design curricula that do not focus on creating objects and artifacts but rather start from new places and different points of view, such as curricula grounded in socio-political and economic contexts of people of the Global South, their ethnic identities, and building mindsets. My explorations around what we teach in design are undoubtedly a reaction to my undergraduate design education, which seemed both German and Brazilian at the same time, because I studied industrial design in the 1990s in the south of Brazil at a school with a curriculum inspired by the Ulm School of Design. Former students and faculty of the Ulm School, such as Max Bill, Tomas Maldonado, Otl Aicher, Karl Heinz-Bergmiller, and Gui Bonsiepe, played a role in developing design education throughout Latin America, in particular in Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Chile, and Cuba (Fernández Citation2006). Though I studied in Curitiba in the 1990s, I could still feel that influence in my education through the curriculum, as some of these people still influenced design and design education at that time. Bonsiepe lived between Florianopolis (a nearby town) and Argentina; Maldonado was Argentinean and was referenced often during my studies; Bergmiller lived in Brazil; so these Ulmian influences were alive and present in the classroom while I was a student.

Drawing it Out

I began drawing these visual thought experiments about design curricula in around 2013, in part as a response to the visual representations of the Bauhaus and the Hochschule Ulm curricula. Walter Gropius diagrammed the original Bauhaus curriculum in a circle that shows the progression of the courses over four years. The curriculum from the HfG Ulm is a Venn diagram-like image that depicts five design disciplines – Product Design, Cinematography, Information, Visual Communication, and Product Design – while also showing social science-type courses that should inform students’ design research: economics, sociology, philosophy, politics, and psychology.

These two visually represented curricula were the starting points for my visual reflections on design curricula. Inspired by the Bauhaus and Ulm illustrations, I began creating illustrations that depicted the core principles that were important in the classes that I was teaching. These drawings supported my reflection and sometimes made it easier to share the big ideas of a class. They were not always drawn for specific courses, but the ideas from the drawings have helped me clarify my point of view and have influenced courses that I have taught.

Drawing the curriculum creates a different experience, as drawing facilitates inference and understanding and is a medium for reflective dialog with one’s ideas (Suwa and Tversky Citation1997). Drawings are one form of external representation of ideas (Goldschmidt Citation1991). Visual thinking for designers is not merely translating an idea in our heads onto an external surface. As we draw, we continue to process and modify ideas while working, rather than just rephrasing them from our heads (Goldschmidt Citation1991). The slowness of drawing creates a space for reflection. As I compose my images, I reflect on the new directions I’d like to explore in a design curriculum. Sometimes the illustration inspires the curriculum, while other times, the curriculum inspires the drawing.

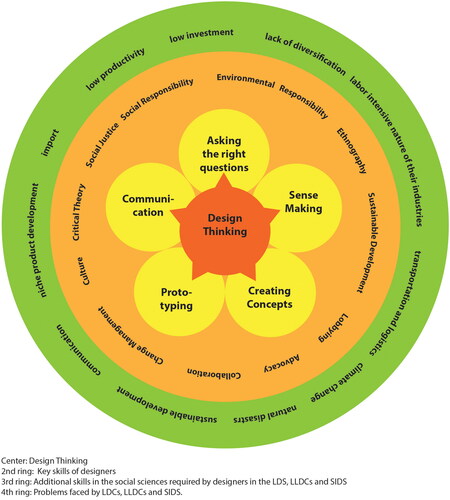

Responding to the Economic Needs of Small Countries

I did my first visual drawing () in 2013–2014 as a response to an article by the design researcher Ken Friedman, who, in describing the design professions, tied design education’s political and social contexts to large industrial economies (Friedman Citation2012). Friedman is not the only person to tie design to industrialization. Wizinsky (Citation2022, 45) also affirms that “modern design is predicated on industrial production.” In my design history classes, especially Industrial Design, the discipline that I originally studied, the link between design and industrialization was always made very explicit. But because I lived and worked in Trinidad and Tobago, I received Friedman’s argument differently. Friedman’s statement seemed to invalidate the relevance of design practice and design education in a place like Trinidad, as it was not a large industrial economy. Friedman – and others before and after who seemed to believe that design could only exist in industrialized contexts – seemed to exclude people who lived in the places that I had spent most of my life: Trinidad and Tobago, other parts of the Caribbean, South America, and East Africa. I believed there was a place for design outside of the capitalist world.

Figure 1 Design curriculum for Least Developed Countries, Small Island Developing States, and Landlocked Developing Countries. Created by the author in 2016.

In response to his paper, I wrote another paper for a conference that included a visual representation of a design curriculum for people in non-industrialized contexts, using the visual representations of the curricula of Ulm and the Bauhaus as a starting point. As I sketched, I thought about the needs of the smallest, least industrialized, and most vulnerable economies. Though we are all vulnerable, the United Nations defines the most vulnerable countries as Landlocked Developing countries (LLDCs), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), and Least Developed Countries (LDCs). The cultural and social contexts of these countries are so different from more industrialized contexts that the questions in a design curriculum for any of them would start with questions that are different to design questions in the Global North. The significant economic and social issues would drive design education in these contexts.

This image began as a hand-drawn image that no longer exists. At that time, I was not confident enough to share my hand-drawn image with others, so I re-drew it digitally to share it with other design educators at a conference in India in 2014. The image depicts a flower inside of two circles. At the center of the flower is “design thinking,” which did not refer to the more commodified design thinking that is popular today. When I drew this in 2013, I was thinking of the way that designers think and solve problems. The yellow petals depict the key abilities to get to design thinking, while the orange ring shows the social science content that would be required in vulnerable economies, such as social and environmental responsibility, sustainability, culture, change management and entrepreneurship, and skills relating to advocacy, lobbying, and the public sector.

The outer ring reflected some of the specific economic issues that designers would have to consider in vulnerable economies. Like Friedman, I also inadvertently tied design to industrial production, evidenced by my focus on economic issues and constraints such as lack of diversification, low investment, and low productivity.

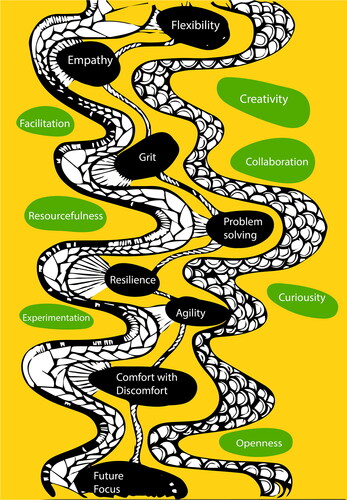

Building Skills for Life and Citizenship

In the second visual curriculum (), I reflected on what could be a function of design other than producing objects for consumption in industrialized contexts.

In doing this drawing, I wanted to move away from the more rigid format that had been inspired by the circular curricula of the Bauhaus and Ulm. For this drawing, I was inspired by a zentangle doodle called “Tangle 102” by Loes van Voorthuijsen. Zentangle art is considered a form of reflective and therapeutic meditation through drawing (Hsu et al. Citation2021). The image was created after an extensive literature review on twenty-first-century skills. In the image, I attempted to visually synthesize information from my research (Noel and Liu Citation2017) and, in this way, make the concepts more accessible to educators who might not read the paper. How can design education go beyond merely preparing designers for professional practice? This research was conducted to build a design curriculum for children in Trinidad and Tobago. The curriculum started from the premise that design activities can build cognitive and intellectual abilities and not just artifacts or services. This curriculum focused on using design education to develop learners’ psychological and social skills for success. This curriculum explored the guiding principles for a non-outcomes-based approach to design education, in which the focus is on social and psychological development and the development of twenty-first-century skills. These skills include “learning and innovation skills, critical thinking and problem solving, communications and collaboration skills and digital or ICT literacy” (Trilling and Fadel Citation2009). In the drawing, I attempted to organize in black shapes the mindsets that are needed for design, and, in the green shapes, the skills of designers. van Voorthuijsen’s zentangle reminded me of a stream, and the skills and mindsets were stepping stones to design abilities.

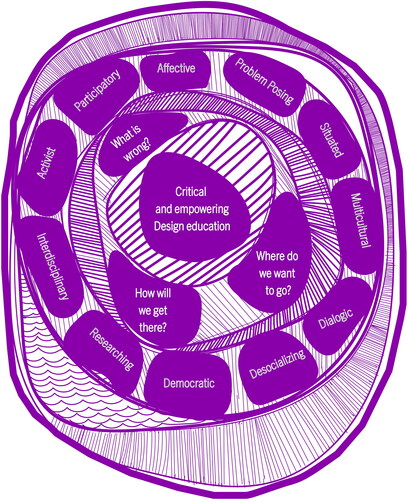

Developing Critical Awareness through Design

Building on the life skills curriculum (), I made the Critical and Empowering Design framework (). As part of my doctoral fieldwork, this was made for a specific context with fourth graders in Trinidad (Noel, Liu, and Rider Citation2020). The course that I was designing combined a rights-based approach to education (i.e. focusing on human rights) with critical pedagogy, using design thinking strategies to help Trinidadian children identify and solve problems within their community. Critical pedagogy transforms oppressive power relationships because it empowers and humanizes the learners by promoting critical questioning (Grant and Sleeter Citation2007). It helps learners recognize that they can overcome constraints, leading to their progress and development (Freire and Macedo Citation2003). In critical pedagogy, combining the teacher’s knowledge and the student’s experiential knowledge leads to a transformed reality (Van Amstel Citation2022). While colonial education prepared people to be docile plantation workers (Bristol Citation2012), education that fosters a critical awareness could encourage the interrogation of “tradition” needed to create change in a place like Trinidad and Tobago.

I wanted to create a student-centered curriculum in keeping with Freire’s approach to pedagogy that utilized students’ experience and showed respect for their knowledge, culture, and language (Shor Citation1992; Peterson Citation2003). I was combining several theories, so I drew to help me visualize how to connect and operationalize these different ideas. I wanted the children to develop their critical consciousness, and I added a focus on the future and agency through design as an active response to the critiques that the children made of the world around them by analyzing their access to human rights and by critiquing their school and village. The curriculum uses Shor’s empowering education principles and incorporates Critical Utopian Action Research (CUAR) questions. Shor’s (Citation1992) empowering education framework encouraged students to become thinking citizens, change agents, and social critics. CUAR connects critiques to utopian ideas and action with local stakeholders around critical questions and around questions that lead to utopian action. What’s wrong? Where would we like to go? How can our dreams become a reality (Husted and Tofteng Citation2015; Nutti Citation2018)?

The illustration combines the core questions of CUAR and Shor’s principles for empowering education. It was drawn by hand on a tablet, using the zentangle style. Using the guiding framework from the illustration, I could then create the content for the classes. In the classes that resulted from this curriculum, children proposed solutions to problems that they identified: the tall mango trees with fruit they could not pick because of the height of the trees; the school rules; the litter in the streets; and even the lack of tourism opportunities in their village. The sessions included discussions and then design exercises around the UN rights of the child, their school and how they wanted to improve it, and, finally, their village and what was the village in which they wanted to live.

Seeking Epistemic Freedom

On epistemic freedom, Ndlovu-Gatsheni writes:

Epistemic freedom is fundamentally about the right to think, theorize, interpret the world, develop own methodologies and write from where one is located and unencumbered by Eurocentrism. (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2018, 3)

I made the fourth and fifth curriculum sketches ( and ), focusing on creating design curricula free from the Eurocentrism that is typical of design curricula. The fourth and fifth drawings were grounded in personal history and culture, particularly Latin American decoloniality and African identity.

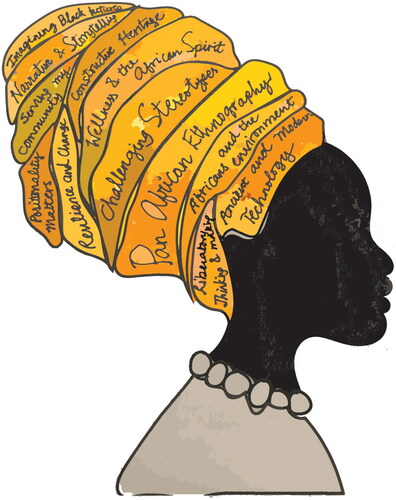

Figure 5 A pan-African design syllabus that focuses on inspiring African people. The courses might include: Imagining Black Futures; Narratives and Storytelling; Serving My Community; Constructive Heritage; Wellness and the African Spirit; Positionality Matters; Resilience and Change; Challenging Stereotypes; Pan-African Ethnography; Africans and the Environment; Liberatory Thinking and Making; and Ancient and Modern Technology.

The Eurocentricity of design education can be limiting and inhibiting for people who do not see themselves, their worldviews, and their ways of knowing and being in the curriculum. When they see people like them, they may not have agency or they may be shadowy background figures, such as aid recipients in a social design program. Moreover, design discourses center what Bhambra described as “western exceptionalism,” where Western “meta-narratives remain unquestioned” (Vázquez Citation2011) and the design culture and histories of the rest of the world are ignored.

As I drew these curricula, the reflection made me more aware of my position in a border space. I dreamed of curricula inspired by Africa and Latin America, though I do not live in either of those places. I do not even live in my home country anymore. Tlostanova – using W.E.B. Du Bois’s concept of double consciousness, which represents the internal conflict of people in underrepresented groups within a dominant culture – noted the double consciousness of those operating in border spaces at the fringes of modernity (Tlostanova Citation2017). Undoubtedly, this border epistemology has impacted my work. I, like many other people, am in between different worlds. I am in modernity yet may romanticize or yearn for a place and culture which may no longer exist.

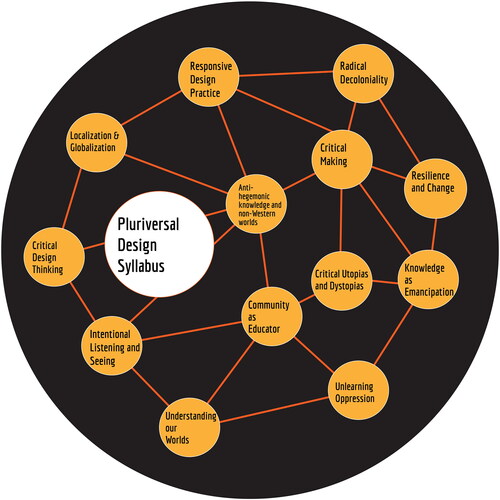

Grounding in Southern Epistemologies

Discourse about decoloniality and pluriversality led by scholars like Escobar (Citation2017), Mignolo (Citation2018), and Santos (2013) inspired the illustration in , in which I mapped out key ideas that could guide my point of view as I continued developing my classes.

The Pluriversal Design Syllabus () is a preliminary visual response to Santos’s (2013) calls for epistemologies of seeing. Some themes or course titles borrow terms directly from Santos’s text (2013, 156). The illustration depicts possible names for courses, emphasizing community, responsiveness, and listening. This image was made during the planning of Pivot 2020 and visually reflects the Pivot 2020 theme, “Designing a world of many centers.” Decolonization is multipolar (Mignolo Citation2018); thus, the image visually depicts multipolarity and pluriversality, with the black circle representing the curriculum and the smaller circles representing the many different, alternative starting points that could exist within this curriculum. The content would not follow a linear progression that is typical of curricula, but rather the educator would choose which pole is the relevant center of their curriculum. Though I called it a syllabus in the drawing, it is more of a curriculum, as a curriculum guides content, while a syllabus provides more specifics on the content. This image is not hand drawn and does not use the zentangle style. The production of the image was faster, but, by using this style, I lost the opportunity for reflection that is created in drawing repeated lines or filling in small details in a drawing.

While this drawing is conceptual, there is an ongoing and vibrant discourse about decolonizing design. Several other authors and practitioners have explored this area and created examples of decolonized design and locally grounded design curricula. In India, the Gandhian Framework for Social Design (Tewari, Nipun, and Saurabh Citation2017) combines Gandhian concepts, general principles of social design, and design principles specific to the Indian design context. Also in India, Visual Alankars is a decolonized visual design framework that borrows principles from Hindi grammars (Singh and Tewari Citation2021). Tlostanova (Citation2017) considers Indigenous decolonial tools of positive ontological design such as Sumak Kawsay, Earth Democracy, and Eurasian Indigenous social movements. These non-European design movements empower design educators from a variety of backgrounds, contexts, and worldviews to move away from replicating the curricula of schools in the Global North and to draw from their contexts to create relevant and contextually relevant design education that will be more meaningful for them and their students.

Seeking Cultural Relevance and Identity

In reflected on creating a design curriculum grounded in who I am as a member of the African diaspora. Being a part of the diaspora and not from the continent itself, I find myself in another hybrid or “in-between” space. My reflection on an African-centered design curriculum is rooted in this hybridity. As I sketched, I reflected on how the film Black Panther (2018) was able to connect people from the African diaspora all around the world. I wondered if there could be an African-centered design curriculum that could connect Black designers around the world. What would represent “Africanness” in a design curriculum? Would the focus be community-centeredness and relationality? Would an empathy map drawn through an African-centered lens differ from one used or made through a non-African lens?

“The Bauhaus is already here!” So proclaimed Serumaga-Musisi (Citation2016) in response to a US design firm promoting plans for a “Bauhaus Africa.” Scorning such self-proclaimed creative saviors, Serumaga-Musisi laments the lack of focus on what Africans do for themselves, reminding the reader that everything African does not come from Western education. Curricula that are imported can make it difficult to see and understand the importance of one’s own context. Serumaga-Musisi emphasized that the creative energy that birthed the Bauhaus is ever-present in the African context, even if the African aesthetic and context seem foreign to the Bauhaus. The way I learned about the Bauhaus was decontextualized, with memorization of facts for exams without understanding the political, environmental, and social context that created the context for the Bauhaus and, later on, the Ulm School of Design. Serumaga-Musisi reminded me that the marriage of creativity, ingenuity, and function that was the Bauhaus is also a mindset that can be found in Accra, Nairobi, and even tiny towns like Kabako in Congo. I can also see that marriage of creativity and function in creative studios in places where I have lived, like Belmont, Port of Spain, and Tunapuna in Trinidad, or Salvador and Curitiba in Brazil. Context is important, and the context for critical design education is, in fact, everywhere.

Many design educators on the African continent innovate and have innovated around localized design curricula. In Zimbabwe, Saki Mafudikwa runs the Zimbabwe Institute of Vigital Arts (ZIVA), which celebrates Africa’s creative heritage and encourages African artists to be inspired by their cultural heritage (Jacobs Citation2013). In West Africa, The African Futures Institute is a postgraduate school of architecture in Ghana founded by Ghanaian-Scottish Architect Lesley Lokko (Walker Citation2021) with the guidance of Boards of Trustees, Patrons, and Academic Advisors, that include many prolific African, African American, and European designers and thought leaders. Lokko also established the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Johannesburg in 2015. While Mafundikwa, Lokko, and other design educators on the continent are creating curricula for Africans in Africa, I reflect on creating an African-centric curriculum through a different lens as someone from the African diaspora who is not in Africa. My reflection is on the emotional significance of diasporic African identity and the impact of the legacy of slavery on Black communities throughout the Americas. This legacy manifests itself in many ways, including the lack of opportunities for Black people, poverty, unemployment, poorer public health outcomes, lack of intergenerational wealth, and negative stereotypes of Black men, women, and children. I am also part of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. I recognize that my African identity in my homeland is different to where I now live in North America, and was different when I lived in Latin America and East Africa.

I reflected on the complexity of Black African diasporic identity as I created the fifth figure, which depicts a pan-African culturally relevant (design) curriculum. The image shows an African woman, and the content of the curriculum is embedded in her headwrap. This image is hand-drawn, and the opportunity for reflection came through writing the content in the turban and creating patterns through color blocks in the headwrap. Some of the principles of this curriculum focus on reimagining Black futures, storytelling, serving my community, and resilience and wellness, among other themes. In thinking of the content for this curriculum, I sought to move beyond the hardships of African diasporic identities. The content of the curriculum examines history in a revisionist manner, includes future-focused themes, provides research skills, fosters liberatory thinking, and promotes community engagement, while also creating much-needed space for reflection on identity. It challenges the negativity that Africans face. While I have not yet used this as a curriculum in a course, I plan to use it as guiding principles in future research.

Conclusion

As I reflect on how I’ve tinkered with the guiding principles of the design classes that I have taught, I recognize that the driving question in all the explorations has always been about making design education relevant, which, in many contexts, means delinking it from its Eurocentrism and rooting it in local issues, cultures, and identities.

These drawings are not neutral. They have agendas, whether to explicitly support vulnerable economies, build life skills for citizenship, promote a critical awareness of society leading to change, or draw inspiration from Latin American decoloniality or African identity. These variations focus on histories, cultures, psychologies, identities, and localities.

The many calls to change design education are rooted in different interests and questions, such as performance, systemic, contextual, and global design challenges (Friedman Citation2019), translation, creation, and articulation (Cezzar Citation2020), or an understanding of contemporary societal issues and ethical concerns (Meyer and Norman Citation2020). As we respond to these calls and reflect on the content of new curricula, we must also see that we are not seeking one future of design education. Instead, a variety of voices, cultures, and epistemologies will lead to not one but many futures of design education. The idea of the pluriverse counters the “one world-world,” instead proposing a world where many worlds fit (de la Cadena and Blaser Citation2018). These many worlds exist at the same time. The futures of design education will be pluriversal as we will learn to co-exist with many ways of doing design that draw on personal histories, a range of identities, localities, and a diversity of motives.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lesley-Ann Noel

Lesley-Ann Noel is a Trinidadian design educator based in Raleigh, North Carolina, where she is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Art and Design at North Carolina State University. She is also co-chair of the Pluriversal Design Special Interest Group of the Design Research Society. She teaches courses on contemporary issues in art and design, design for social innovation, and design studies. Her research focuses on using design methods to support youth participation and agency, social innovation, STEM education, and patient-centered public health. She is currently creating a social-justice-centered design curriculum for youth that combines game design with Afrofuturism. [email protected] [email protected]

References

- Bristol, Laurette. 2012. Plantation Pedagogy: A Postcolonial and Global Perspective. Global Studies in Education. New York: Peter Lang.

- Cezzar, Juliette. 2020. “Teaching the Designer of Now: A New Basis for Graphic and Communication Design Education.” Design Education. Part II 6 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2020.05.002.

- de la Cadena, Marisol, and Mario Blaser. 2018. A World of Many Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Escobar, Arturo. 2017. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Fernández, Silvia. 2006. “The Origins of Design Education in Latin America: From the Hfg in Ulm to Globalization.” Design Issues 22 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1162/074793606775247790.

- Freire, Paulo, and Donaldo Macedo. 2003. “Rethinking Literacy: A Dialogue.” In The Critical Pedagogy Reader, edited by Sharon Helmer Poggenpohl, 354–364. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Friedman, Ken. 2012. “Models of Design: Envisioning a Future Design Education.” Visible Language 46 (1/2): 132–153.

- Friedman, Ken. 2019. “Design Education Today—Challenges, Opportunities, Failures.” Chatterjee Global Lecture Series. https://www.academia.edu/40519668/Friedman._2019._Design_Education_Today_-_Challenges_Opportunities_Failures

- Goldschmidt, Gabriela. 1991. “The Dialectics of Sketching.” Creativity Research Journal 4 (2): 123–143. doi:10.1080/10400419109534381.

- Grant, Carl, and Christine Sleeter. 2007. Turning on Learning: Five Approaches for Multicultural Teaching Plans for Race, Class, Gender and Disability. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Hsu, Mf, C. Wang, S. J. Tzou, T. C. Pan, and P. L. Tang. 2021. “Effects of Zentangle Art Workplace Health Promotion Activities on Rural Healthcare Workers.” Public Health 196: 217–222. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2021.05.033.

- Husted, Mia, and Ditte Maria Børglum Tofteng. 2015. “Critical Utopian Action Research and the Power of Future Creating Workshops.” In LARA 9th Action Learning Action Research and 13th Participatory Action Research World Congress 4-7 November 2015, South Africa.

- Jacobs, Liz. 2013. “5 African Artists Who Are ‘Learning from the Past’ in Their Work |” TED Blog. August 3. https://blog.ted.com/5-african-artists-returning-to-their-rootsmafundikwa-companion-piece/

- Meyer, Michael W., and Don Norman. 2020. “Changing Design Education for the 21st Century.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 6 (1): 13–49. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2019.12.002.

- Mignolo, Walter D. 2018. “Foreword: On Pluriversality and Multipolarity.” In Constructing the Pluriverse, edited by Bernd Reiter, ix–xv. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2018. Epistemic Freedom in Africa: Deprovincialization and Decolonization. Rethinking Development. Oxford: Taylor & Francis.

- Noel, Lesley-Ann, and Tsai Lu Liu. 2017. “Using Design Thinking to Create a New Education Paradigm for Elementary Level Children for Higher Student Engagement and Success.” Design and Technology Education 22 (1): 1–12. doi:https://eric.ed.gov/?id = EJ1137735.

- Noel, Lesley-Ann, Tsai Lu Liu, and Traci Rose Rider. 2020. “Design Thinking and Empowerment of Students in Trinidad And Tobago.” Cultural and Pedagogical Inquiry 11 (3): 52–66. doi:10.18733/cpi29503.

- Nutti, Yiva Jannok. 2018. “Decolonizing Indigenous Teaching: Renewing Actions through a Critical Utopian Action Research Framework.” Action Research 16 (1): 82–23. doi: 10.1177/1476750316668240.

- Peterson, R. E. 2003. “Teaching How to Read the World and Change It: Critical Pedagogy in the Intermediate Grades.” In The Critical Pedagogy Reader, edited By Antonia Darder, Marta P. Baltodano and Rodolfo D. Torres, 354–364. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Santos, Boaventura. 2013. Epistemologies of the South. Boulder, CO: Paradigm.

- Serumaga-Musisi, Namata. 2016. “Bauhaus Already Lives Here and Why the World Still Doesn’t Know It.” Transition 119: 5–8. doi:10.2979/transition.119.1.02.

- Shor, Ira. 1992. Empowering Education: Critical Teaching for Social Change. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Singh, Raina, and Saurabh Tewari. 2021. “Visual Alankars: Toward a Decolonized Visual Design Framework.” In Design for Tomorrow—Volume 1, edited by Amaresh Chakrabarti, Ravi Poovaiah, Prasad Bokil, and Vivek Kant, 543–553. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Suwa, Masaki, and Barbara Tversky. 1997. “What Do Architects and Students Perceive in Their Design Sketches? A Protocol Analysis.” Design Studies 18 (4): 385–403. doi:10.1016/S0142-694X(97)00008-2.

- Tewari, Saurabh, Prabhakar Nipun, and Popl Saurabh. 2017. “A Gandhian Framework for Social Design:The Work of Laurie Baker and Hunnarshala.” In Research into Design for Communities, Proceedings of ICoRD 2017, Vol. 2, 337–348. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Tlostanova, Madina. 2017. “On Decolonizing Design.” Design Philosophy Papers 15 (1): 51–61. doi:10.1080/14487136.2017.1301017.

- Trilling, Bernie, and Charles Fadel. 2009. 21st Century Skills: Learning for Life in Our Times. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Van Amstel, Frederick. 2022. Pluriversal Design SIG Book Club 4: Pedagogy of the Oppressed. YouTube video, 58:57, 11 May 2022. London: Pluriversal Design SIG. https://youtu.be/c7LXeHiHkOM.

- Vázquez, Rolando. 2011. “Translation as Erasure: Thoughts on Modernity’s Epistemic Violence.” Journal of Historical Sociology 24 (1): 27–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2011.01387.x.

- Walker, Ameena. 2021. “African Futures Institute Launches Website.” July 28, 2021. https://www.design233.com//articles/african-futures-institute-website-launch.

- Wizinsky, Matthew. 2022. Design after Capitalism: Transforming Design for an Equitable Tomorrow. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.