Abstract

From its creation in 1999 to its demise as a government-funded organisation 11 years later, the Commission for Architecture & the Built Environment (CABE) fronted a national drive in England for better design in the built environment. Whilst not universally supported at home, its scope and ambition were certainly impressive, and as an organisation it was unique on a global scale. As such the study of this exceptional initiative offers an unparalleled opportunity to shine a light on the often unfathomable processes of governing the design of development. This paper reflects on the organisation in two key ways. First, from the narrow perspective of CABE’s impact: what worked and what did not; and what can we learn from CABE. Second, what does the experience tell us about the nature and purpose of design governance and about the role and legitimacy of government within this most “wicked” of policy arenas.

Keywords:

Introduction

Governmental controls over aspects of design in the built environment, for example, for devotional purposes (of monarch and/or deity), have a very long history indeed. In modern times such activities have been given new meaning and purpose for a wide range of health, safety, social, economic, aesthetic and latterly environmental objectives. We can roll all such activities together under the banner of design governance, or “The process of state-sanctioned intervention in the means and processes of designing the built environment in order to shape both processes and outcomes in a defined public interest” (Carmona Citation2013).

The British New Labour government of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown from 1997 to 2010 was tracked for most of its period in power by a second smaller scale experiment in the design governance field; one with potentially longer lasting impacts as enshrined in the fabric of England’s towns and cities. This was the attempt to address questions of design in the built environment through systematic government action. The most significant expression of this was the work of the Commission for Architecture & the Built Environment (CABEFootnote1) which sought to understand, campaign for and prescribe solutions to the delivery of better architectural, urban and public space design to the nation at large. Yet, while CABE was a publicly funded arm of government, the nature of its work was largely informal and non-statutory.

Typically, the evolution of design governance practices have been slow and incremental, although from time to time dramatic innovations come along including the instigation of zoning practices in Europe and then the US in the early twentieth century, the designation of conservation areas/historic districts in the 1960s, the sudden spread of design review practices across the US in the 1980s and the development of design coding practices on both sides of the Atlantic in the 1990s. The work of CABE in England in the 2000s should certainly fall into this category. A detailed exploration of the organisation’s evolution over its 11 years, the tools it developed and harnessed for its work, and its position within the wider sweep of national design governance approaches in England is provided elsewhere, as is discussion of the exhaustive literature on design governance and its methods (see Carmona, de Magalhães, and Natarajan Citation2017). Here, the focus is more specifically on CABE’s impact and what that reveals about the legitimacy of design governance at large.

Interrogating CABE

The history of CABE has an uneven arc where from the turn of the century CABE quickly rose to become an influential and trusted arm of government, and despite ups and downs continued to play an important role until its funding and status were abruptly cut around a decade later. CABE inherited its core function, the delivery of a nationwide design review service, from its predecessor the Royal Fine Art Commission (RFAC) which had been doing just that since 1924 (Carmona and Renninger Citation2017a). The RFAC had been set up as a quasi-autonomous non-governmental body (or quango), funded by government but answerable to its own commission made up of the great and the good from the design/built environment world. Early in its life, CABE demonstrated a strong desire to use its position as the new kid on the block in order to rapidly spread its horizonsFootnote2 from the single design review service that it had inherited from the RFAC into the all-important areas of: local authority enabling (or providing direct targeted assistance within local government on projects, policy frameworks, commissioning and capacity building, amongst other things); producing research and guidance (the RFAC had done a little of this – Carmona and Renninger Citation2017b); engaging in a wide range of advocacy and campaigning activities within government and beyond; and into the skills arena (eg developing tools for school children to engage with design in the built environment, and promoting urban design to the established built environment professions).

Over time government found ever more reasons to invest in CABE. This both supported design quality for its own sake (eg providing core funding to conduct more design review, including to support regional providers of a design review service) and a range of more specific policy objectives and programmes that greatly expanded (and to some degree politicised) the organisation’s role (Arnold Citation2009). Most notably, this included a major new role supporting enhancement of the nation’s green spaces from 2003, and a range of work supporting the government’s attempts to tackle the various housing crises throughout the 2000s. As a result CABE grew rapidly, from just a few staff to around 120 at its height and with an annual budget that multiplied over 21 times from the half a million or so pounds that it began with.

Throughout, CABE was steered by a strong commission and executive that were powerful flag-bearers, bolstered by a committed pool of staff and a much wider “CABE family” of contractors, volunteers and sympathetic organisations. Indeed this engagement of a large diaspora across the country in the pursuit of better design, often with little or no remuneration, represented remarkable value for money for the state and one of the critical successes of CABE.

When, in its first few years, the commission had the ear of government and decision-making was less formalised, CABE was able to be very dynamic. When government funding increased, it empowered the commission to grow its staff and thus engage more deeply nationwide. This, however, required a far greater formalisation of its processes and under the terms of the Clean Neighbourhood and Environment Act 2005, from January 2006 CABE became a statutory body, although without statutory powers (other than to exist and conduct its services). Its organisational goals also evolved from a focus on challenging the notion that architecture was a “stuck on veneer,” in the words of is first Chairman, to a far more comprehensive set of built environment goals. Throughout it retained a mission to improve the quality of design in the built environment at its heart.

The prominence and status of design quality was clearly strengthened via CABE’s advocacy work across government, and its exhaustive work engaging directly with local government and industry, but its total reliance on government for funding meant that its ability to provide critique of government programmes or to define and pursue its own priorities was sometimes compromised (Parnaby and Short Citation2008). This tension was built into the DNA of the organisation from the start and latterly, as one insider commented, it struggled with “how to challenge and collaborate in equal measure.” Its position as the design advisor to government, despite its lack of statutory powers to enforce its will, also gave rise to what some regarded as an unduly imperious and detached manner in its dealings with industry (particularly through design review). Over time this won the organisation an increasing number of enemies in influential circles (eg Lock Citation2009). Not helped by this, or by a less favourable attitude to quangos generally within the David Cameron-led coalition government from 2010 onwards, CABE ultimately fell victim to the fallout from the economic crisis of 2008 and the desire to make rapid savings in the public finances.

In the words of one high profile commissioner, “It wasn’t there to make money, it was there as education, policing, cajoling … it was amazing, but it took public funds and bravery to do that – a very brave government.” Political support for CABE was absolutely vital throughout its history and ultimately it was a failure to adequately and irredeemably make the case for design amongst its political paymasters that cost the organisation its future leading to closure in April 2011 (Waite Citation2010). Exploring this rich and complex history was the work of a major research project funded by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

A pump-priming phase

Following announcement of CABE’s closure, the importance of seizing the moment before the resources, evidence and collective memory of those involved in the organisation was lost was recognised by CABE itself. In the last months of its existence the commission funded a quick-fire pump-priming project to explore the possibility of a larger study and, if feasible, to assist in making a research application to one of the UK research councils. This initiative funded the location of a researcher within CABE for a period of 25 days with unprecedented access to CABE’s remaining personnel and archives. The intention of this phase was to:

| • | Work with a team from the UK’s National Archives in order to identify and safeguard key resources as part of an evidence base for subsequent research | ||||

| • | Begin the process of mapping key programmes, outputs, people and responsibilities before the organisation closed and the collective memory was lost | ||||

| • | Start conversations with key stakeholders that have shaped the CABE experiment and whose experience needed to be captured as part of the evidence base. | ||||

A five-stage, multidimensional, inductive investigation

The substantive research phase ran from January 2013 to August 2014. It employed an inductive research methodology that sought to learn from the specifics of practice and apply that to an integrated theory of design governance. Five research stages were followed.

Stage 1. Analytical framework building

This work aimed to establish a comprehensive understanding of the international design governance literature and relate it to the context of CABE, by:

| • | Exploring the theoretical treatment of design within public policy, development, property market and political contexts and its position within wider urban policy | ||||

| • | Tracing the CABE story (and that of the RFAC) in the professional/academic literature and in the news media (for example, reviewing over 10 years worth of press clippings), and evidence of the methods and impact of any comparator organisations. | ||||

| • | Developing and deepening the analytical framework of “tools of governance” (as will be discussed) providing structure and coherence to the empirical data on CABE and a means of coordination to the overall research with its multiple interlocking lines of enquiry. | ||||

Stage 2. Organisational interrogation

On the basis of documentary analysis (of 2868 source documents) using NVivo software, a second stage involved the in-depth review of all key policy, programme, project and performance management documents produced by CABE (and its sponsor government departments), as well as those produced by periodic external reviews of the organisation. The aim was to understand the drivers and barriers to the CABE experience and to trace CABE’s history against the wider political and urban policy context. Key outputs included:

| • | A series of working organisational maps of how CABE developed over its history and of how its work responded to external political priorities and pressures | ||||

| • | The first full account of the range of CABE tools, programmes, projects, people and relationships | ||||

| • | A comprehensive review of the key outputs from CABE’s various programmes, with a comparison, as far as possible, against the resources dedicated to different steams of work | ||||

| • | An understanding of how the organisation itself operated, established priorities, allocated resources, measured success, etc. | ||||

Stage 3. Gathering first-hand views and accounts

Utilising the findings from Stage 2, a range of in-depth semi-structured interviews (39 in total) were conducted with two key audiences. First, those both from within and outside of CABE (including in government) centrally involved in establishing and developing the organisation and its approaches, and/or eventually in shutting it down. This included both professional and political players. Second, interviews with key opinion formers on record as being either supportive and/or critical of CABE at various stages in its history. Both sets of interviewees were chosen because of their prominence during the organisational interrogation. The intention was to:

| • | Test the accuracy of the Stage 2 outputs | ||||

| • | Understand the political, organisational, resourcing, professional and practical drivers and barriers for CABE; to get under the skin of the organisation with the benefit that distance gives to those once intimately, but now no longer, involved | ||||

| • | Understand the support given to and critique of the organisation and its work, and the roots of such opinions | ||||

| • | Identify critical episodes in CABE’s work for potential further analysis during Stage 4. | ||||

Stage 4. Conducting episode-focused reunions

Key episodes within each tool were chosen for closer inspection, with individual activities such as design reviews relating to master planning, research projects focusing on value arguments and enabling in the parks sector. This provided deeper understanding of process, problematics and impact, rather than trying to somehow deduce lessons from across multiple disparate episodes. A sample of 24 significant episodes covered the broad sweep of modes of intervention and those critical moments for the design agenda that were identified by key stakeholders at Stage 3.

“Reunion” events brought together key protagonists from each episode of CABE’s work, its partner organisations, and the recipients of the work; followed by more focused individual interviews as and when required. The intention of these was to understand both the bigger picture and what had worked and what had not, and to gather detailed evidence about the effectiveness of key programmes and tools. Each of the 24 reunions was structured around the aspirations, processes and outcomes from each episode, and conducted using focus group methods of moderation. The free and open discussion between parties was recorded and later transcribed before coding, analysis and reflection on how findings might or might not be re-interpreted in the post-CABE world.

Stage 5. Synthesis

With multiple analytical techniques, it was important to carefully and individually document each stage of the research before attempting a full synthesis and evaluation against the fundamental research questions. Each form of data was subjected to qualitative analytic reduction, display, analysis and deduction, and the analytical framework (refined during the course of the research) provided a series of related proformas through which to coherently summarise and display the data such that it could then be coordinated for synthetic work.

The diverse methodological approaches were written up separately before triangulating the evidence as a means to draw out common findings in an inductive manner ultimately brought together in this paper. The diversity of approaches helped to and overcome known potential weaknesses with each one in order that a more rounded and coherent view of the CABE experiment could be revealed. In the discussion that follows, space does not always permit a full exposition of the evidence sources underpinning every point made. Each substantive finding is nevertheless grounded in evidence gathered across the five stages of the research collected over two and a half years of detailed investigation.

The impact of state-led design governance

CABE was a product of its time and reflected trends inherent in the larger political economy. Underlying the new politics was a “governmentalist” belief in the power of government to address key areas of public policy, reflecting in England an historic tendency to take power to the centre (House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee Citation2009). New (or greatly extended) areas of policy were developed across government, providing a bespoke governance infrastructure to pursue the newly defined public policy goals. The treatment of design under the New Labour governments of 1997–2010 is arguably the prime example of this, bringing together economic, social and environmental policy components. The CABE experience demonstrated a significant extension of public policy in an area that British Governments previously had made strenuous efforts to avoid becoming embroiled with, preferring instead that design be dealt with behind the closed doors of the RFAC (Richards Citation1980), or as a local matter, or not at all.

Approaches to governance in the period borrowed heavily from the “managerial” methods that were then increasingly dominant in the state’s administrative practices (Pierre Citation1999); not just in the development of targets to drive performance (to which CABE was subject) but also reflecting a wider move from the 1980s onwards of using dedicated arms length agencies that were focused on private sector style missions as part of the neoliberal state. Thus, CABE was charged with the role of becoming the government’s advocate on matters of built environment design, a role that required it to make value judgements about what good design entailed and to “take ownership” of this policy arena. This it did with great energy, and quickly came to dominate (some interviewees argued, even over-dominate) the field.

Whilst CABE was itself a product of these approaches, the documentary analysis revealed that it also applied them in its work programmes, both in managing the CABE family and in its belief that influence begins with developing a shared understanding of the problem at hand. It, for example, sought to promote an understanding of the processes of design and development which would spread an appreciation of generic principles that could be leveraged in optimising the performance of players in the sector, be that developers, regulators, investors (public and private) or designers. This was central to the CABE method as, without formal regulatory powers of its own to require others to take particular approaches to design, it had to rely on a range of informal tools of influence to do its work (see Carmona Citation2017a). These encompassed:

| • | Evidence: Gathering evidence about design and design process to support arguments about the importance of design, underpin advice about what works and what does not and monitor progress towards particular policy objectives or gauge the state of the built environment (eg through research or audits of design practices) | ||||

| • | Knowledge: Articulating and disseminating knowledge about the nature of good design, good and poor design practice, and why it matters (eg through the production of practice guides, case studies of best practice and through education and training) | ||||

| • | Promotion: Making the case for design quality in a more proactive manner by taking knowledge to key audiences and seeking to package messages in a manner that engages attention, wins over hearts and minds and exhorts particular behaviours (eg through the use of design awards, campaigning, advocacy work and the building of partnerships) | ||||

| • | Evaluation: Tools through which systematic and objective judgements can be made about the quality of design by a party external to, and therefore detached from, the design process or product being evaluated (eg through the use of indicators, informal design review, certification of schemes and running design competitions) | ||||

| • | Assistance: Proactive means to engage the public sector directly in projects or in otherwise shaping the decision-making environment within which design occurs (eg through direct financial assistance, and enabling). | ||||

Finally, as reflected in the third-way politics of the period, CABE might be seen as one attempt to marry “popularism” with “pragmatism” (Hall Citation2003). In other words constructing policy solutions that did not alienate key interests and emphasised what works rather than what was dogmatically prescribed in one form of politics or another. Arguably, the new focus on design did not become a priority for government in the 2000s simply because the achievement of better design was intrinsically seen as a good thing. Instead, good place-based design was viewed as politically expedient. Firstly, it was a means to popularise (or at least sweeten the pill of) the construction of large quantities of new housing that the nation needed, but which faced community opposition fortified by a reaction to the generally poor quality of development that had predominated in the 1980s and 1990s. Second, good design was a necessary pre-condition for a re-investment in cities, and signalled that the historic tendency towards sprawl was to be reversed in favour of a renaissance in urban areas whilst protecting the countryside. These were in essence the core arguments of the Urban Task Force (Citation1999) which the government had commissioned to look into the urban challenges of the time. Government signed up to the urban renaissance agenda and with it also to CABE.

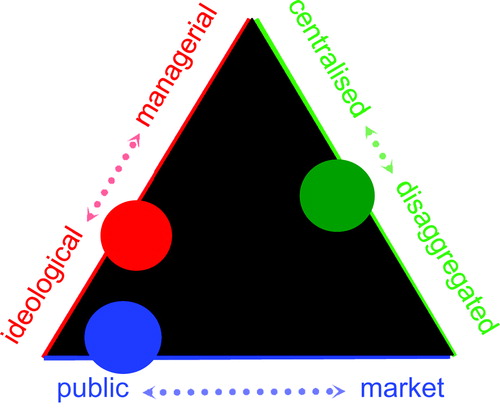

Taking a broader look at the extensive urban governance literature revealed a triad of fundamental characteristics within whose parameters urban governance of all types sits. Whilst space does not permit a full exploration here (see Carmona Citation2017a), in sum they are: the mode of operation, whether ideological (directed at particular political objectives) or managerial in style; the relative concentration of public authority, whether centralised or disaggregated, including to arms length agencies; and the power to deliver, whether public- or market-oriented. Relating the framework to the work of CABE (Figure ), the organisation can be represented as:

| • | Ideological but pragmatic – focused on a single core objective, the national improvement of design quality (broadly defined), but pragmatically extending and developing that agenda in line with the policy and political priorities around it | ||||

| • | Centralised decentralisation – delegation from government direct to a single arms-length organisation (CABE), but through them to a network of approved regional organisations and a wider CABE family across the country | ||||

| • | Publically oriented/active – 100% state funded and controlled with only indirect non-directive powers, but through its considerable authority, energy and initiative, able to set and drive a national agenda for design that public and private players alike could not ignore. | ||||

Perceptions of CABE

Whilst some of the governance trends discussed above pre-dated New Labour, notably the growing interest in the importance of design in government, they strongly set the context for the work of CABE and (evidence from the reunions suggested) were reflected in how the organisation saw itself and its role, and how others perceived it and whether it was being effective or not. In this regard an important point to make is the seemingly obvious one that CABE was by no means universally popular. Indeed, as was obvious in press reports, from the very start the organisation was often under fire from different players that it rubbed up against: sometimes architects (who hadn’t fared well in design reviews), sometimes national politicians (whose policies seemed to be called into question on design grounds), sometimes professional institutes (who felt CABE was encroaching on their turf) and sometimes developers (who no longer had quite such a free hand). Indeed, as one interviewee suggested, only partly in jest, “by the end CABE had pretty much alienated everyone which perhaps explained its demise.”

That of course hugely overstates the case, as underpinning these tensions was a clear and seemingly popular agenda – the pursuit of design quality – that the organisation pursued with great energy, initiative, leadership and (usually) focus for over a decade. Therefore, whilst many criticised aspects of its activities and governance style (as will be seen) the evidence gathered during the research pointed to overwhelming support for much of what CABE did and a ready acceptance that the organisation played a very significant role in changing the perceived importance and actual delivery of design quality in England and beyond. Yet as an organisation, CABE was never well understood in terms of its size and scope and its relationship to government, and many of the harshest critiques of its work seem to stem from this simple fact, as the following sections reveal.

Whilst external perceptions (notably in the professional media) were often of a monolith swallowing up huge dollops of tax payer’s money to conduct design review, in fact the organisation was tiny by government quango standards, and only around a fifth of its staff were dedicated to design review where most of the headlines (and periodic controversy) had their roots (eg Blackler Citation2004; Clover Citation2004). The rest of the staff worked on lower profile but typically (if evidence from across the research stages is to be believed) highly regarded and effective activities such as: enabling in local authorities; a range of research projects, the work of its public spaces and parks arm (CABE Space); the Building for Life initiativeFootnote3; and various educational enterprises. Moreover, whilst at its height CABE boasted an annual budget of around £11.6 million, increasingly large proportions of this represented annualised project funding to deliver particular ring-fenced programmes of government rather than CABE’s core services. Most of this in turn focussed on injecting a quality dimension into the sizable capital expenditure programmes of New Labour, such as the Building Schools for the Future initiative.Footnote4

CABE, before and after

Notwithstanding the clear antecedence of many of the governance trends in which it was embedded, CABE will always be associated with New Labour. To some degree, however, CABE found itself stuck between a rock and a hard place courtesy of its relationship with the Labour government. Thus, whilst central government saw CABE as a highly competent delivery organisation and increasingly loaded it up with “programmes” to roll out, this left the organisation vulnerable to the whims of ministers, to the annualised public spending round, and to perceptions that CABE was getting flabby. Some interviewees argued that such programmes also diverted its attention and energies away from its own design leadership role. Moreover, whilst gaining considerable authority as the government’s de facto design arm, the reliance on public money for survival left CABE at least partially gagged and increasingly unable to claim true independence. Indeed the documentary record shows that on several occasions the organisation had its wrists firmly slapped when the more control-minded ministers of New Labour’s later years detected that government policy was not always being fully supported by CABE’s programmes.

In the UK, the renewed effort to positively address questions of design in the built environment through public policy (which CABE later fronted) began under the final Conservative administration of the 1990s. Acting partly on the basis of personal interest, but also in the face of the same issues around housing growth and where it should go that later confronted New Labour, the then Secretary of State, John Gummer, transformed the policy environment in relation to design (Carmona Citation2001, 72). Under him, design moved from the proscribed list (for public intervention) to the prescribed one and urban design became the new focus for policy instead of aesthetic control. This move provided a firm basis for the rise of design further up the political agenda in the New Labour years. In the UK it gives the lie to arguments that CABE was exclusively a project of the left, whilst internationally it undermines arguments that design quality is anything other than an apolitical matter. Thus, whilst some have argued that the pursuit of better design is an elitist concern and associate its regulation with the political right (Cuthbert Citation2011, 224), others conflate attempts to correct market failure through government action with the left and see attempts to control design as the needless imposition of barriers to change and innovation within the free-market (Van Doren Citation2005, 45; 64). In both cases design tends to be equated with a narrow concern for “aesthetics” rather than with the more fundamental issues around functionality, liveability, sustainability, economic viability and social equity that became CABE’s design agenda.

Comparing, the different models of state-led design governance that have been deployed in England since 1924 (Table ), in many respects the CABE experience can be viewed as a middle way. Thus, whereas the RFAC was ideological in its outlook and often uncompromising in its advice, albeit easily sidelined behind its seemingly exclusive St James’s Square door in London’s Mayfair (Carmona and Renninger Citation2017a), the design governance landscape of the post-CABE austerity years provides only uncoordinated provision of design governance services and views about design out of which little commonality prevails (Carmona Citation2016). By contrast, the CABE years provide a clear point of national leadership, but one reasonably responsive to the diversity of contexts (political and geographical) within which it operated, care of coordination through a coherent regional network of design governance providers that reached out across the country.

Table 1. National design governance models compared.

Moreover, whilst both the RFAC and CABE had in common that they were public functions of the state with a clear orientation towards the public sector – contrasting with the market-led approaches (most notably to providing design review) and voluntarism (eg the Place AllianceFootnote5) that now dominate in the post-CABE (austerity) years – they also enjoyed central funding and experienced vulnerability to the winds of political change because of it. CABE nevertheless had in common with the post-CABE era that it was highly active in its advocacy for design and fully exploited the range of tools available to it. Likewise, in the absence of CABE, the market is highly active in selling the services that it now provides, flexibly adapting CABE’s protocols to meet business opportunities wherever they can be found, and this is complemented by voluntary action that, with little or no resources, seeks to fill the gaps (Carmona Citation2016).

CABE’s impact

Turning from its modus operandi to its achievements, many of those interviewed for the research reported that impact was a particularly difficult issue to get a handle on and even more difficult to measure. In part this may be because many of CABE’s impacts were so diffuse in nature, and focused on influencing the decision-making environment for design (the processes of quality), rather than in making specific and tangible interventions in projects or places. Consequently, when compared with more focused organisations, some of those interviewed could readily see the costs, but not always the benefits; helping to explain the widespread negative perceptions about the size and cost of CABE amongst built environment professionals.

Despite this, the detailed examination of CABE’s work and legacy that formed the core of this research revealed a number of profound and tangible impacts as reported in the literature, through the interviews and reunions, or documented in the press or CABE’s archives. Whilst CABE’s mission was cut short in 2010, many of these impacts, categorised in Table on the basis of the evidence gathered during the research, are still apparent five years after CABE’s demise, including its impact on national policy, on the projects it reviewed and on key development stakeholders such as some, although not all, of the nation’s volume housebuilders.

Table 2. CABE’s impacts.

As a small organisation (by governmental standards) CABE undoubtedly punched above its weight, demonstrating in the process how, despite its diminutive size, such an organisation might operate within and across government. But CABE also had to regularly make the case for its existence and the “value it added,” and, as an unpublished Handover Note on the subject revealed (CABE Citation2011), CABE was evaluated around 20 times during its existence,Footnote6 most notably as a feed into the then government’s Comprehensive Spending Reviews of 2004, 2007 and 2010.

In its final and most comprehensive self-examination – Making the Case – CABE submitted a 50,000 word case to government that, in its own words, made “a compelling case for CABE’s impact” (CABE Citation2010). The evidence was indeed extensive and varied, and ranged from the quantifiable, such as an assessment that CABE’s design review services resulted in users benefiting from expertise with a market value of £684,450 per annum that cost the public purse only £163,800, to the unquantifiable, such as the impact of CABE’s work on the life choices of the thousands of school children that came into contact with CABE’s educational materials. Benefits ranged from the highly tangible, for example, that satisfaction surveys revealed 88% of users found CABE’s enabling advice useful and 84% found that enabling advice changed what they did, to the intangible, such as the ultimate impact of the green space strategies prepared by the 180 councils using tools that CABE had provided. In this and other documents CABE made regular and extensive use of its own research, as well as that conducted by others (internationally), to make the case that better design could have a positive impact on health, education, well-being, the economy, safety, levels of crime and environmental sustainability, amongst other factors.

Such evidence remained convincing as long as politicians were committed to CABE and were open to accepting the case CABE regularly made for its own existence. History shows, however, that when resources ran short, political expediency simply dictated that this sort of evidence was ignored and CABE was shut down.

The use of multiple overlapping informal tools and commitment to the cause

The collective efforts of the CABE family enabled a proliferation of activities with regional outreach, and involved a wide range of informal design governance tools, although never with regulatory force. Indeed CABE decisively supported and/or pioneered a range of new tools, including its enabling service, Building for Life, housing audits,Footnote7 and urban design summer schools. All of these had a strong impact, if judged by the numbers they reached, and alongside their research, extensive output of guidance and high-profile advocacy and campaigning work (which CABE took to new heights), helped to build a strong reputation for CABE across the country. At the same time there was always a significant body of professionals and others who actively opposed CABE, many of whom, as revealed in extensive press coverage, tended to view the organisation largely in terms of its design review function. As CABE expanded its reach and prominence, this criticism grew and the organisation was more frequently seen as overstepping its remit or acting in a domineering or overly aggressive manner. So while CABE had confidence in its public interest role, some were concerned that it increasingly appeared to colonise rather than engage other bodies and professionals that were acting in the same field (Ibrahim Citation2009).

Where CABE differed most decisively from what came before and after is in the sheer scale of activities that its significant public funding allowed, and, over time, the ability that gave the organisation to proactively reshape the landscape for design governance in England. In this regard CABE undoubtedly had a big impact, and the majority of those interviewed or who attended the reunions saw that impact as a broadly positive one if measured against its core objective of improving the standard of design in the built environment. As one insider commented, “CABE didn’t lead the profligate life, it was relatively tightly funded, but it had a meaningful sum and it had a sum where it could have an impact beyond the individual schemes that it saw,” both cumulatively (project by project and on larger places) as well as on the larger national demand for better design as encapsulated in political priorities.

In its early years, CABE was sometimes referred to as an unconventional organisation; within and funded by government, but not in a governmental mould. Instead it was able to agitate, innovate and shake things up, and exploit tactics not usually associated with the public sector to influence those not previously receptive to or interested in its messages about the significance of design. Whilst, as the organisation grew and matured this “guerrilla” phase of its evolution came to an end (indeed had to end when it ran into trouble – Brown Citation2004), CABE remained a very determined unit and one unusually effective at responding to the changing political context within which it found itself.

In part, this seems to be because of the persistence of a culture that emphasised continued learning and innovation and the flexible application of its knowledge and practices to the range of challenges that the organisation addressed. For example, and unusually for such a quango, from the very beginning it had its own research section. It also reflects the fact that the sorts of “informal” tools at its disposal were particularly adaptable and not subject to the rigidity of being defined in statute or circumscribed by government policy. Its tools also lent themselves to use in combination so that particular challenging problems, such as the design of volume built housing, could be confronted from different angles and with different combinations of evidence, knowledge, promotion, evaluation and assistance, depending on the need and the possibility of influence in any particular context.

A key lesson from CABE is therefore that despite the limitations of its individual powers, its ability to spread its messages on multiple fronts and through a diverse and continually changing toolkit, made it a very effective organisation. As the period prior to CABE’s existence (and perhaps the period after) revealed (Carmona and Renninger Citation2017b), the over-reliance on a single tool (namely, design review) will only ever have a limited impact and eventually, as happened with the RFAC, those limitations will come to define (and undermine) the whole process of governing design (Fisher Citation1998). Instead, the CABE experiment powerfully demonstrated that the use of multiple overlapping informal design governance tools not only cover the design governance field of action (from shaping the design decision-making environment, to influencing particular project outcomes) more comprehensively than formal regulatory tools, but can also decisively influence the manner in which those formal tools operate, in turn enabling them to operate more effectively.

The legitimacy of design governance

New Labour was a pragmatic experiment immersed in the “third way” philosophy of “if it works, back it” rather than on basis of any dogmatic belief systems (perhaps explaining why it was, and still is, despised by so many). Considered in its own terms as the pragmatic application of flexible tools to different circumstances, as opposed to the dogmatic application of systematic rules everywhere (see Figure ), the CABE experiment must be judged a success. It amounted to an investment by the state of the equivalent of 0.02% of the size of the construction industry in England (Carmona Citation2011) that had very significant impacts on the cultures and practices of development nationally and on design governance processes locally, leading to a new sensitivity towards an interest in design (as the reunion discussions repeatedly reinforced).

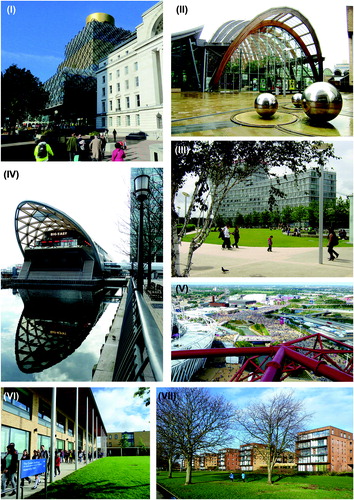

But the CABE experiment represents just one approach to state-led design governance and its successes should not be taken to imply either that such an approach would be suitable everywhere or at any time, or that all (other) forms of intervention in design by government and its agencies are necessarily also effective. A considerable literature suggests that this is far from the case and that poor design governance is often as bad, or perhaps worse, than none at all (eg Ben-Joseph Citation2005; Talen Citation2012). Moreover, not everything CABE touched was a success. Some tools, such as the use of design competitions, never got any momentum, whilst others, notably design review, were often mired in controversy, although ultimately had a significant positive impact on a diverse range of projects (Figure ).

Figure 2. CABE’s influence was profoundly positive on a wide range of successful projects as diverse as the Birmingham library (i), Sheffield Peace Gardens (ii), Liverpool One retail quarter (iii), the Crossrail stations in London (iv) and the 2012 Olympic projects both in London (v) and elsewhere, numerous school projects across the country (vi), and many residential-led master plans, such as Kidbrooke Village (vii).

Multifarious critiques

A range of theoretical problematics of design and its governance have been set out elsewhere (Carmona Citation2017b) and CABE was accused of all of those (and more) during the course of its existence. During the research these multifarious critiques (many contradictory) were frequently, and often compellingly, re-stated by interviewees, in the reunions and in the press clippings analysed as part of the work. Summarising them, CABE was accused of being:

| • | A neoliberal pro-development tool: simply sweetening the pill of otherwise unpalatable and inequitable projects that offered little to society at large – “they were just very focused on the message that any kind of work with the built environment and green space should add profits” | ||||

| • | A poodle of the state: too nervous of upsetting its sponsors and therefore lacking the ability to confront government when it needed to be done – “it was the government’s little toy to help it do some things that it was easier to do at arm’s length” | ||||

| • | London-centric: because that was where the money, politics and biggest projects were – “it became evident that they were a London based coterie of chums, all the way down, the agenda, the menu, the interest is London luvvies, they were not interested in the rest of England” | ||||

| • | Preoccupied with “shiny urbanism”: reflecting the recipes of the “urban renaissance” and the metropolitan fascination with “starchitects,” rather than the challenges of suburban England where most wanted to live – “the town cramming, high density, mixed use, ban cars, café culture and all that vision that Lord Rogers foisted upon people, that was their agenda” | ||||

| • | Too unfocused: expanding too readily into different agendas and getting distracted from its core mission – “CABE was so bound up delivering these Service Level Agreements for government; we couldn’t see the wood for the trees, we were doing too much” | ||||

| • | Elitist in multiple ways: organisationally elitist (assuming that CABE should lead and others would follow); professionally elitist (because architectural design is inevitably so); exclusionary (only engaging positively with those already in the clique, aka the “CABE family”); elitist in its processes (particularly the “closed shop” of design review) – “elitism, dear God, yes. They were going to produce standards and guidance, which the rest of us would just have to be obliged to follow” | ||||

| • | Not elitist enough: failing to bring the powerful architectural establishment on board as key supporters of the organisation – “they should have had somebody who was much more embedded in the central London chattering classes of architects, who knew those people, who could talk to them” | ||||

| • | Scared of aesthetics: and determined to see design in purely objective terms, whereas, in reality, it was not – “sometimes something would come into design review and nobody would say “that is incredibly ugly” because everything was based on facts and figures to avoid design being seen to be a matter of taste” | ||||

| • | Style biased: with an in built bias towards contemporary design and against traditional architecture – “It was certainly pro-modernist, … they thought that anything that might be a classical design was basically pastiche and therefore couldn’t be dealt with and was rubbish” | ||||

| • | Inconsistent in its advice: because much was intangible and not everything or everyone could be boiled down to a simple set of objective criteria – “you had some completely opposing views from some of the CABE commissioners. If you got the wrong one on your committee, then you knew you were in for trouble” | ||||

| • | Too powerful and undermining freedom: by imposing a state-sanctioned view on design that often ventured into matters of detail (aesthetic and functional) that should rightfully be a matter for the scheme promoter – “you might find that CABE stifled as many good buildings as it encouraged, and who are they, or who are we, to judge whether those are good or bad buildings ultimately” | ||||

| • | Too weak: because they worked through influence rather than compulsion and therefore influenced those who wished to hear the message and not those who didn’t – “if they’d ever found a way in which they could actually get the housebuilders in a headlock, that would be fine, but they didn’t” | ||||

| • | Insensitive to professional responsibility: by failing to take account of the professional standing and perspective of those it sought to advise – “you spend seven years in training, then a lot time gaining experience and, actually, that should be enough, then an outside organisation such as CABE takes the responsibility away from the architect. … there’s a kind of emasculation if you like.” | ||||

| • | Insensitive to the market: lacking market nous by being often divorced from the commercial concerns of the different markets in which they were offering advice – “when you’re considering a scheme in an affluent area of west London, and you’re doing one in a regeneration area, you have to look at things differently … so cutting your cloth accordingly is very important and CABE didn’t quite understand that” | ||||

| • | Overbearing and arrogant: by stealing the work and initiatives of others without giving sufficient credit and by being insufficiently supportive and too condescending to those it dealt with – “it was almost like you were at school … You know, the sort of school ‘teachery’ thing ‘I know best, stop talking, shut up and listen to what I’m saying and don’t question it’.” | ||||

| • | Too verbose: pronouncing too much and producing too much guidance – “ultimately, there’s only so much guidance you can read – it just gets put on shelves” | ||||

| • | Obsessed with communication: believing that being heard was more important than what was said – “they brought in lots of people that had nothing to do with the built environment, they became increasingly interested in media output, as opposed to actually serious, proper information and guidance” | ||||

| • | Too flabby and over-managed: growing too large with too many managers and not enough workers – “CABE had got bigger and bigger and bigger and more and more bureaucratic” | ||||

| • | Subject to conflicts of interest: conflicts that were more perceived than real but nevertheless at key times damaging to CABE’s credibility and its standing within the sector – “we were told by the then permanent secretary that … ‘CABE’s in the pocket of the developers isn’t it?’.” | ||||

Most of the latter types were sanguine that such criticisms were par for the course, and that largely the same critiques would have been made about any other organisation in a similar field.Footnote8 As one commissioner concluded: “It would be hugely naive to imagine that the kind of glory years, if I can put it like that, when you’re brand shiny and new, will last. There’s nothing unexpected, or unusual about that. You wouldn’t find a public body, or public agency in the world where people aren’t saying it’s too this, or too that, or too big, or too small, or too powerful, or too weak. That just goes with the territory.”

A simple case for intervention

So given the inevitability of the critiques, and their at least partial legitimacy, what is the moral/societal case for continued intervention in this area? Ultimately, as CABE’s life and demise demonstrated, that is a political judgement. Pragmatically the CABE experiment has shown widespread, tangible and positive results leading to a long-term legacy of better projects, places and processes than would otherwise have been the case, and with positive impacts across England on local populations, the environment and society at large (see Table ). This is in exchange for, what by any standard, was a very small national investment in the field, almost an “accounting error” in governmental terms as one interviewee described it.

Yet, this will need to be set against other costs, beginning with the unknown but certainly much larger investment by the private and/or public actors by dint of simply engaging with services of design governance, such as those CABE provided: for example, through getting involved in a processes of enabling; attending a training event; or turning up to a design review and afterwards amending a scheme. Also, beyond the financials, there are other costs, notably accruing to those whose freedoms have been curtailed to design (well or badly) by such processes, or to professional egos that have been damaged as a result. Finally, there will be costs in the mistakes that from time to time even the most sophisticated and carefully run processes of design governance will inevitably make (Figure ).

Figure 3. One of CABE’s mistakes as widely recognised by those who were involved, as one influential insider commented: “The Walkie Talkie is more elegant, believe it or not, as a consequence of CABE’s reviews of it, but obviously, there will always be projects like that where we could and should have done more.”

Morally, politicians will need to decide where their priorities lie. The CABE experiment shows that, despite the cost, the case is weighted very heavily on the side of intelligent light touch intervention through the full range of design governance tools. Politicians will have to explain, when we know what good urban design means and the benefits it brings, and when we know how to design good places and how to facilitate those processes, why we still fail to do so and why (too often) they don’t care enough to learn the lessons and start to turn the situation around.

Conclusion

Following the passage through the Houses of Parliament of the statutory instrument that formally dissolved CABE, John Penrose, the Tourism and Heritage Minister at the time who signed the order, commented in the House of Commons:

CABE did a lot of good work and much of it will continue in different places. The organisation may be coming to an end under the order, but its work and the principles that it embodied will continue. I hope and expect that the public sector’s commitment to good design in our built environment will continue, too.Footnote9

Equally, it could be argued that CABE failed to sufficiently make the case for design and so, faced with choices about where to make the spending cuts, the coalition government of 2010–2015 decided that the axe would fall on CABE. For others, the seeds of CABE’s demise were sown when CABE became a statutory organisation and “came into the mainstream.” As one commissioner argued, “if you take the terrorist out of the organisation, you remove the agitation and when you remove the agitation, it’s very easy to remove the organisation.” Another commented “the criticisms were either that CABE wasn’t doing enough, or it was doing too much, which is probably a sign that it was doing about right.”

Drawing from the experiences of CABE to address the question, ‘how should design governance be conducted?’, the answer can only be, rather inconclusively, that ‘it depends’. It depends on the context within which it is being conducted, over what scale, by whom, with what intentions, and with what resources. Recognising this diversity and shaping their tools to each challenge, nationally, or locally, was the great strength of CABE. So wherever the environment within which it is being conducted, it is possible to conclude that those responsible should fully embrace the informal as well as formal modes of design governance, and should consider such processes to be part of a long-term and necessary societal investment in place.

The situation in England post-CABE has revealed that all too quickly it is possible to forget the difference that such a coherent and sustained investment in state (and local) design governance infrastructure can make, and to focus instead on making cuts in the areas that are politically easiest (where opposition is least vociferous) and that are least tied up in statutory obligations. These include the sorts of discretionary services that relate to design. Again, this was arguably a failure of CABE (despite its stated intentions), to adequately reach out to a larger constituency beyond the built environment professionals that were already convinced and to create a demand for good design within the population at large; or to take advantage of the opportunities that came CABE’s way to make the case for underpinning its activities (notably design review) with a formal and statutory status that would have tied them into the non-discretionary machinery of the state. So, whilst during its existence CABE undoubtedly changed the culture for design and played a critical role in driving design up the political agenda, both nationally and locally, this was a culture change built on sand. When CABE was no longer around to remind us of the importance of good design, we quickly forgot.

The situation post 2011 has shown that, unlike, for example, health, defence or education, the quality of the built environment is simply one of those areas that we need to keep on reminding ourselves has value and should be a prime concern of the state. As, in England, the cost of poor design mounts, sooner or later we will need to remember.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Matthew Carmona is a professor of Planning & Urban Design at UCL’s Bartlett School of Planning. His research has focused on urban design, processes of design governance and on the design and management of public space. Matthew was educated at the University of Nottingham and is a chartered architect and a planner. He chairs the Place Alliance which brings together organisations and individuals who share a belief that the quality of the built environment has a profound influence on people’s lives.

Claudio de Magalhães is a reader in Urban Regeneration and Management at UCL’s Bartlett School of Planning. He worked for 12 years as a planner in Brazil, acquiring considerable experience in urban governance and in the management of urban investment. He has worked as an academic in the UK since the mid-1990s, first at Newcastle University and since 1999 at UCL. His interests have been in planning and the governance of the built environment, the provision and governance of public space, property development processes and urban regeneration policy.

Lucy Natarajan is a senior research associate at UCL’s Bartlett School of Planning, where she is researching the strategic planning of renewable energy infrastructure. Previously, she worked as the principal researcher in the International Department of the Royal Town Planning Institute. Her research centres on excellence in policy-making, and she works in both quantitative and qualitative modes. Since 2002, she has conducted a range of studies across collaborative governance, community participation, local planning, spatial planning, public health and urban design governance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council [grant number AH/J013706/1].

Notes

1. Throughout this paper references to “CABE” relate only to the government-funded body that existed from August 1999 to April 2011 and not to “Design Council CABE” that initially inherited some of CABE’s functions but which no longer receives core government funding and is now one of many market players providing design review services in England.

2. The archive website for CABE still demonstrates the diversity of its interests and initiatives, see: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/.

3. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/building-for-life.

5. See: http://placealliance.org.uk.

6. Sometimes externally and sometimes internally, but excluding its own annual reports.

8. For example, about The Arts Council or English Heritage.

References

- Arnold, D. 2009. “CABE at Ten: Is it Doing Too Much.” Architects’ Journal, September 11. http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/-cabe-at-10-is-it-doing-too-much/5207922.article.

- Ben-Joseph, E. 2005. The Code of the City: Standards and the Hidden Language of Place Making. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Blackler, Z. 2004. “Bias Allegation Hits CABE.” Architects’ Journal, March 18. http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/home/bias-allegation-hits-cabe/656648.article.

- Brown, P. 2004. “Architecture Body Chief Quits Ahead of Report.” The Guardian, June 17. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2004/jun/17/urbandesign.arts.

- CABE. 2010. Making the Case, unpublished evidence submitted by CABE to the 2010 DCMS ‘value for money’ assessment of its NDPBs. London: CABE.

- CABE. 2011. Handover Note 10: CABE Evaluation. London: CABE.

- Carmona, M. 2001. Housing Design Quality, Through Policy, Guidance and Review. London: Spon Press.

- Carmona, M. 2011. “CABE R.I.P. … Long live CABE.” Town & Country Planning 80 (5): 236–239.

- Carmona. 2013. The Design Dimension of Planning (20 Years On). https://www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/planning/centenary-news-events-repository/urban-design-matthew-carmona.

- Carmona, M. 2016. “Design Review: Past, Present and Future.” Urban Design Matters. https://matthew-carmona.com/2016/08/04/design-review-past-present-and-future/.

- Carmona, M. 2017a. “The Formal and Informal Tools of Design Governance.” Journal of Urban Design 22 (1): 1–36.10.1080/13574809.2016.1234338

- Carmona, M. 2017b. “Design Governance: Theorising an Urban Design Sub-field.” Journal of Urban Design 21 (6): 705–730.

- Carmona, M., and Andrew Renninger. 2017 “The Royal Fine Art Commission and Seventy-five Years of English Design Review: The First Sixty Years, 1924–1984.” Planning Perspectives: 1–21. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02665433.2016.1278398.

- Carmona, M., and Andrew Renninger. 2017. “The Royal Fine Art Commission and Seventy-five Years of English Design Review: The Last Fifteen Years, 1985–1999.” Planning Perspectives:. doi:10.1080/02665433.2017.1286609.

- Carmona, M., C. de Magalhães, and L. Natarajan. 2017. Design Governance, The CABE Experiment. New York: Routledge.

- Clover, C. 2004. “Quango ‘Wanted to Destroy Listed Buildings’.” The Telegraph, June 21. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1465035/Quango-wanted-to-destroy-listed-buildings.html.

- Cuthbert, A. 2011. Understanding Cities, Methods in Urban Design. London: Routledge.

- Fisher, J. 1998. “Architecture: The Country’s Architectural Enforcer.” The Independent, August 21. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/architecture-the-countrys-architectural-enforcer-1173032.html.

- Hall, S. 2003. “New Labour’s Double-shuffle.” Soundings 24 (24): 10–24.

- House of Commons Communities and Local Government Committee. 2009. The Balance of Power: Central and Local Government, Sixth Report of Session 2008–2009. London: The Stationary Office.

- Ibrahim, M. 2009. “Civic Trust Loss of Green Flag Contributed to Collapse.” Horticulture Week, April 24. http://www.hortweek.com/civic-trust-says-loss-green-flag-contributed-collapse/article/900322.

- Lock, D. 2009. “Rules for the Design Police.” Town & Country Planning, July/August: 308–309.

- Parnaby, R., and Short, M. 2008. CABE, Light Touch Review. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.culture.gov.uk/reference_library/publications/5787.aspx/.

- Pierre, J. 1999. “Models of Urban Governance: The Institutional Dimension of Urban Politics.” Urban Affairs Review 34 (3): 372–396.10.1177/10780879922183988

- Richards, J. M. 1980. Memoirs of an Unjust Fella. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Talen, E. 2012. City Rules, How Regulations Affect Urban Form. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Tiesdell, S., and P. Allmendinger. 2005. “Planning Tools and Markets: Towards an Extended Conceptualisation.” In Planning, Public Policy and Property Markets, edited by D. Adams, C. Watkins and M. White, 56–76. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Urban Task Force. 1999. Towards an Urban Renaissance. London: Spon Press.

- Van Doren, P. 2005. “The Political Economy of Urban Design Standards.” In Regulating Place, Standards and the Shaping of Urban America, edited by E. Ben-Joseph and T. Szold, 45–66. London: Routledge.

- Waite, R. 2010. “Spending Review, CABE Closed Down.” Architects’ Journal, October 20. http://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/daily-news/spending-review-cabe-closed-down/8607174.article.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Building_Schools_for_the_Future

- http://placealliance.org.uk

- http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/

- http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/building-for-life

- http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/www.cabe.org.uk/housing/audit

- https://www.gov.uk/government/news/commission-for-architecture-and-the-built-environment