ABSTRACT

Walking should be one of the primary modes of transportation in sustainable cities, being more environmentally friendly, sociable, and health conscious. The principles of New Urbanism (NU) promote walkability, creating urban patterns that support the needs of pedestrians. With that in mind, this study aims to define the relationship between walkability and NU in the context of urban regeneration, establishing the urban attributes that influence walkability in the revival of post-industrial areas. The research comes from a statistical analysis of the flow of people in Księży Młyn (Poland) and a field study from Carré de Soie (France) where urban attributes potentially determining walkability were evaluated. The study confirms that pedestrian traffic and urban form can be optimised through a holistic approach. It sets out the relationship between walkability and various phenomena, including i) social – how users behave in public spaces (the role of pedestrians and cars), and to whom the space is dedicated; ii) economic – how the attractiveness of the service and commercial offer are improving, and how real estate prices are changing; and iii) environmental – how the visual attractiveness of the place and the convenience of the space for pedestrians has improved (shop frontage and accessibility).

The background of new Urbanism

New Urbanism (NU) is an approach to urban planning and design that has come to be closely associated with the process of improving and shaping the development of American suburbs (Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Speck Citation2010). Its principles have now come to be used in Europe again, in various urban regeneration projects, for example, in the renewal of the Roubaix city centre, the Clichy Batignolles area of Paris, Zielone Polesie and the New Centre in Łódź (Cysek-Pawlak Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019). While the movement prioritises the appropriate location of civil buildings, the highest importance is given to the quality of public spaces (Katz Citation1994; Talen Citation2019) and building a “sense of community” (Audirac and Shermyen Citation1994; Markley Citation2018; Cabrera Citation2019).

The goal of a walkable neighbourhood is therefore connected with affordability: well-serviced surroundings lead to lower transportation costs for the inhabitants (Talen Citation2010; Clark and Wright Citation2018; Talen Citation2018; Bhattacharya, Dasgupta, and Sen Citation2020). As one NU slogan says, the movement “promotes the end of segregation between rich and poor” (Day Citation2003, p. 84; Trudeau and Kaplan Citation2016). The NU’s vibrant urban places are intended to support healthier lifestyles with more socially cohesive urban environments (Podobnik Citation2011; Roulier Citation2018; Higgins and Swartz Citation2018; Iravani and Rao Citation2020).

The urban regeneration context for NU

Today’s challenge for the NU is making an asset out of a place’s individual identity, which is why the use of regional vernacular style is stressed (Calthorpe Citation1993). This approach becomes a gateway to implementing NU in urban regeneration (Larsen Citation2005; Talen Citation2006). Clearly, each specific place has its particular conditions, but in the urban regeneration process, a number of general principles and good practices can be adjusted to resolve urban problems (Agirbas Citation2020; Falanga Citation2019; Pontrandolfi and Manganelli Citation2018; Dusza-Zwolińska and Kiepas-Kokot Citation2018; Ricciardelli Citation2017; Roberts Citation2008). This article accepts the definition of revitalisation as an integrated process for social and economic recovery, including the improvement of physical and environmental conditions (Lichfield Citation1992; Hemphill, McGreal, and Berry Citation2002; Lorens Citation2010; Parysek Citation2015; Bottero and Mondini Citation2017).

It is this aspect of multidimensionality, via place-specific strategies (Güzey Citation2009; Gullino Citation2009; Ye Citation2019; Mecca and Lami Citation2020), that can lead to sustainable urban transformation (Newman and Jennings Citation2008; Vojnovic Citation2014; La Rosa et al. Citation2017; Toli and Murtagh Citation2017; Wolfram Citation2019). Revitalisation should be read as an element of reurbanisation (Noworól Citation2010). The result is a compromise, worked out jointly by its participants with the assumption of cooperation, equality, and involvement of all the communities concerned (Kaczmarek Citation2015).

The international debate is concentrated on the internal and external factors of tackling urban decline, such as a citizen-led neighbourhood (Coletti and Rabiossi Citation2020), a heritage-led concept (Lak, Gheitasi, and Timothy Citation2020; Fouseki and Nicolau Citation2018) and the European regulative mechanism (Gregorio Hurtado Citation2019), as well as those related National Programmes based on NU values (Vale Citation2018). The issue of urban regeneration is still a valid challenge, especially for places with a rich industrial heritage (Lehmann Citation2019a; Kostešić, Vukić, and Vukić Citation2019), where public spaces play an important role (Mussinelli et al. Citation2020; Lehmann Citation2019b). This approach has also been followed in Polish writing on the subject (Szafrańska, Coudroy de Lille, and Kazimierczak Citation2019; Kazimierczak and Szafrańska Citation2019; Stryjakiewicz et al. Citation2018; Skalski Citation2007; Jarczewski and Dej Citation2015; Stryjakiewicz Citation2014) and in French (Darchen Citation2019; Kazimierczak Citation2014) where the urban regeneration context has been applied.

The principle of walkability in NU

A basic imperative of NU is supporting an urban design that is able to satisfy the residents’ needs in a manner that is quick and easily accessible for a pedestrian – namely within a five-minute walking distance (Duany and Plater‐Zyberk Citation1991; Gratz and Norman Citation1998; Girling et al. Citation2019; Dutton Citation2000). This means that walkability must be viewed as a key principle of this movement. It is so crucial also because it relates to one of the primary active transport modes for sustainable cities (Antonini, Bierlaire, and Weber Citation2006; Reisi, Nadoushan, and Aye Citation2019; Bereitschaft Citation2018; Arellana et al. Citation2020).

In order to verify the existence of a correlation between NU and walkability, it would be useful to look at the phenomenon of walkability itself as, despite its popularity in post-modernist planning, the term “walkability” is not clearly and universally defined. E. Talen states that walkability “is the extent to which the built environment supports pedestrian activity – shopping, visiting, strolling, etc.” (Citation2013). It takes a multidisciplinary approach where the basic elements that might impact the examined phenomenon are block-level design quality, including greenery and the convenience of the pavements, the existence of parking lots, shopfronts, blank walls, as well as traffic volume, street connectivity, density, and mixed-use. Those diverse factors embedded in the socio-ecological framework affect physical activity behaviours (Alfonzo Citation2005; Ruggeri, Harvey, and Bosselmann Citation2018; Rundle et al. Citation2019; Wang and Yang Citation2019). When talking about walkability, it is also worth mentioning the CWD urban neighbourhoods (Compact, Diverse, Walkable). These have an overall impact on the security, health and social relations of the urban environment (Talen and Koschinsky Citation2014; Lynch and Mosbah Citation2017; Zuniga-Terana et al. Citation2019; McCormack et al. Citation2020).

New Urbanists are also working on verifying the relationship between walkability and a sense of space, which is visible in the design work of A. Duany, P. Calthorpe, E. Plater-Zyberk, S. Polyzoides and E. Moule. However, to date, there has not been any research examining the condition of walkability as an effect in the quality of the revitalisation process. This is, therefore, the unique contribution of this paper. In addition, the research uses a unique methodology to analyse the flow of people, based on the Android system, within the transformed area, which is an underexplored area of research.

Methodology

Taking into account the correlation between NU and urban regeneration, as well as NU and walkability, the questions posed for the purpose of this research are threefold: how can walkability be improved in post-industrial areas? (1), what is the relationship between urban form and the transformation of a post-industrial area into a pedestrian-friendly environment? (2) and how can the principles of NU play an important role in the process of urban regeneration, including improvements in walkability? (3).

The main purpose of this research is therefore to define the relationship between walkability and NU in the urban regeneration context, as well as to establish which urban attributes influence walkability in the regeneration of post-industrial areas. It sets out the relationship between walkability and various phenomena, including i) social – how users behave in public spaces (the role of pedestrians and cars), and to whom the space is dedicated, ii) economic – how the attractiveness of the service and commercial offer are improving, and how real estate prices are changing, and iii) environmental – how the visual attractiveness of the place and the convenience of the space for pedestrians has improved (shop frontage and accessibility). Moreover, the objective is to provide insights into the practice of urban regeneration projects, especially the threats to and opportunities for walkability. In addition, existing regulatory frameworks and operational urbanist tools potentially impacting the researched phenomenon are evaluated. The research concentrates on public spaces and their role in the urban regeneration of post-industrial areas.

To carry out the goals of the research, multiple aspects have been taken into account during a two-level study. The first is theoretical – a literature review enriched by expert interviews: active actors of the projects, such as Camille Daudet, the project manager from Mission Carré de Soie – Métropole de Lyon, as well as academics and non-governmental organisations including Professor L. Coudroy de Lille (University of Lyon) and the Forum of Urban Redevelopment. Those interviews allow the literature research to be updated with the newest and as yet unpublished aspects.

The second covers an empirical analysis of walkability in the urban regeneration environment marked by industrial history, and a practical element – concentrated on an area of Łódź (Poland) and comparing the examined processes to a similar project in Grand Lyon (France). The French example is referenced not only because of the similarities of the problems being tackled in both areas but also due to the diversity of the proposed solutions and their effectiveness. Because of the lack of dates, the same statistics of pedestrian movement could not be analysed in Grand Lyon, meaning that the work there concentrated on the qualitative study and serves in the research as a base for establishing urban attributes. In Łódź, the researched area is Księży Młyn, while in the Lyon agglomeration it is the area of Carré de Soie, located in the communes of Vaulx-en-Velin and Villeurbanne.

For Księży Młyn, the research includes a broad analysis of the flow of people. Thanks to cooperation with the company Cluify, it was possible to obtain data related to the pedestrian flow in various time brackets: 6 a.m.-10 a.m., 10 a.m.-4 p.m., 4 p.m.-7 p.m. and 7 p.m.-11 p.m., as well as aggregated data for working days and weekends. Heat maps worked out in the research illustrate the intensity of traffic at any given point of the public space in the researched area. The data were collected in the period between 23 March and 23 June 2019. The research used the API Location from the Android system and was delivered thanks to SDK code placed in mobile applications.

The study uses the locations determined directly by the Android system on mobile devices through the Fused Location functionality. The data were sent directly from users’ devices from at least one of the 88 cooperating applications on the Android system. The exact list of partners is confidential, though these are various categories, such as car navigation, games, social networking sites, or applications with coupons/discounts or relating to public transport. In the chosen methodology, the frequency and duration of location scans depend on the frequency of use of individual cooperating applications and system versions; scans are performed every 3 to 15 minutes. From the total data, records not related to pedestrians were excluded based on speed (Chandraa and Bharti Citation2013).

The statistical analysis included a probability calculus, containing conditional probability. Scaling is a two-stage process, in the first stage the probability of tracing a person in a given area is determined, provided that there was a person there, which is extended to a list of people passing through the area within the range of available devices. The second stage uses the estimated place of residence and the surrounding demographic structure as a basis from which to extend the values to the entire population. These calculations were necessary in order to assign scans to a graph representing roads and paths in the studied area, and then to scale them to the values of the actual number of passers-by. Afterwards, the functional and spatial solutions were evaluated, both in places with the highest pedestrian traffic, as well as the most avoided places. The examined elements of the urban pattern were checked with the solutions existing in the French example of Carré de Soie from the start.

Research area

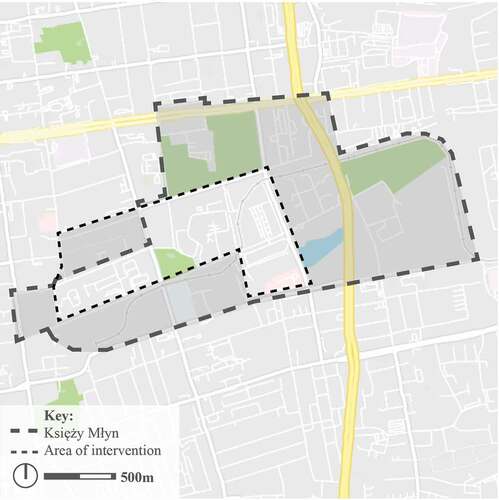

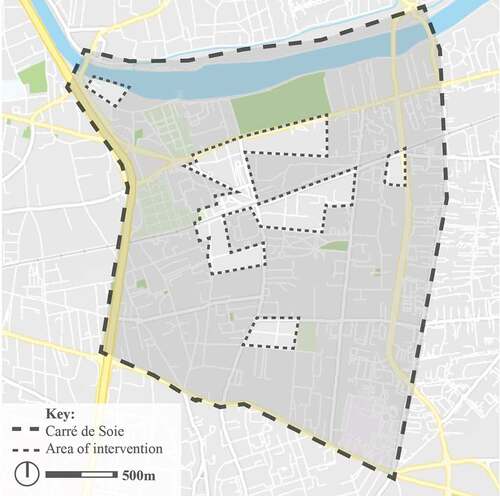

Księży Młyn and Carré de Soie were chosen as they are both historically significant textile industry production sites that are now being transformed into modern residential neighbourhoods (). In the researched areas, new residential buildings were constructed and existing post-industrial buildings were repurposed.

Księży Młyn was developed in the 19th century as a textile enterprise of Karol Wilhelm Scheibler, the founder of the largest cotton enterprise in Poland at that time (Tomczak Citation2008; Kobojek Citation1998; Małagowski Citation1998). A distinctive characteristic of this neighbourhood was its holistic approach, including a school, a hospital, and housing apart from the factory buildings. The now old and dated residential buildings are labelled as a “poverty ghetto”, and contemporary efforts are attempting to create a more attractive image (Majer Citation2006; Hanz Citation2015; Hanzl Citation2011; Boryczka Citation2011). Apart from private housing investments and similar offerings for business, such as the Textorial Park business centre and a revitalised fire station, the area is subject to municipal development plans presented in both the Integrated Programme for the Rehabilitation of Księży Młyn (Resolution of the City Council of Lodz No XLV/843/12) and in the local zoning plan (Resolution of the City Council of Lodz No III/58/18, XXVIII/483/11, LXV/1219/06, LXVI/1684/18, and XL/776/2000).

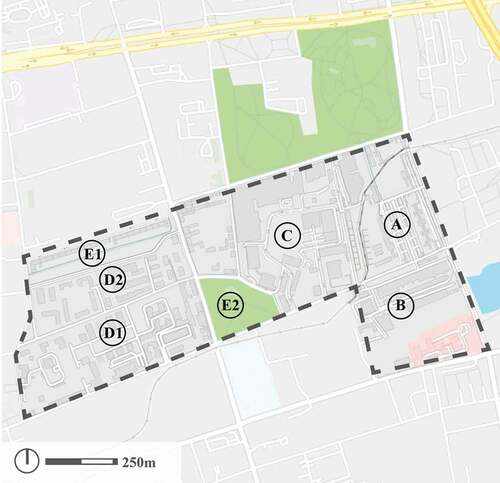

The researched area is composed of the following, spatially distinctive parts (): historical residential buildings, currently still used for housing (A); historical former factory buildings, mostly transformed into lofts with new buildings constructed consistently following the original bare brick aesthetics (B); a Special Economic Zone utilising several post-industrial buildings with contemporarily constructed warehouse space (C); an area dominated by contemporary residential buildings with closed gate communities (D1) and parts open to passers-by (D2); green areas for walking through (E1) and parks (E2).

The design of Carré de Soie is also closely related to its post-industrial structure, with well-developed housing and services. In this case, the industrial empire was owned by the Gillet family, which specialised in the production of silk and nylon in the TASE factory. It is worth noting that the French example is located further away from the contemporary centre of the main city – Lyon. Therefore, in this project, reliable public transport connections are crucial. The project plays a part not only in the development of the city, but in the development of the entire agglomeration. This is reflected in the planning documentation on many different levels of the Agglomeration of Lyon: Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale, Grand Lyon, Plan Local d’Urbanisme et de l’Habitat along with the Zone d’Aménagement Concerté and Projet Urbain Partenarial, as well as its predecessor Programme d’Aménagement d’Ensemble. An important characteristic of Carré de Soie is its location on the perimeter of a shopping centre, which is a distinct structure and does not have a lot in common with the historical tissue.

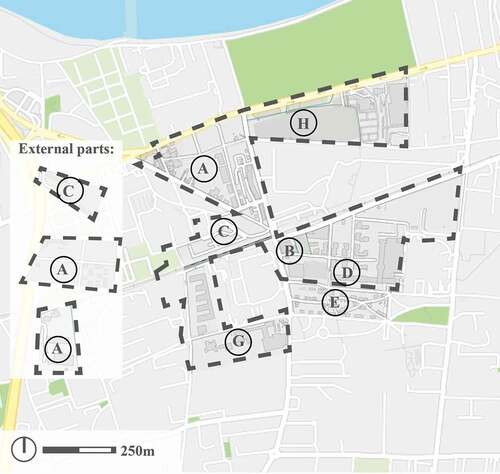

The Carré de Soie project, similarly to the urban regeneration of Księży Młyn, was started in the first decade of the 21st century (2009 and 2005, respectively) and also has clear and distinctive urban parts (): new residential buildings in the form of closed gate communities (A); a new mixed use building dominated by offices (B); new office buildings with significant public spaces (C); the former TASE factory buildings, now transformed into office and service spaces (D); historical residential buildings (E); individual historical buildings currently being adapted to new service functions (G); and the shopping centre (H).

The urban pattern and walkability

Urban attributes were used while examining walkability. These were, derived from the literature on urban regeneration and the New Urbanism theoretical framework related to the pedestrian traffic measurements. The list of urban attributes set out below was composed to include elements that are key to the quality of a space, and therefore also for its performance. The table includes elements connected to the urban dimensions defined by leaders of the movement such as K. Lynch (Citation1984), J. Ghel (Citation1971) or J. Jacobs (Citation1961), enriched with, or rather updated by observations of modern researchers (e.g. Furuseth Citation1999; Addy Citation2004; Cerin Citation2007; Badland, Schofield, and Garrett Citation2008; Kashef Citation2011; Talen Citation2013) as well as the specific features of the examined places.

The defined urban attributes also have strong references to indicators and measurements of quality of the urban regeneration process. The frameworks we have taken into account are as follows: Hemphill, Berry, and McGreal (Citation2004), B. Ferri (Citation2017), Chiua, Leeb, and Wanga (Citation2019), Korkmaz and Balaban (Citation2020). Assessment can be used as an effective tool for working towards sustainable urban development (Wong Citation2000). A multi-criteria analysis, therefore, enables the urban regeneration process to be better managed and serves as an effective communication tool among a diverse range of public users (Crescenzo et al. Citation2018; Qu, Leng, and Ma Citation2019).

Therefore, when defining urban attributes, which in this article work as a sort of indicator, we draw on phenomenon proven in the literature, adapting them to the specific context of our chosen place of study (Wei Zheng, Qiping Shen, and Wang Citation2014; Franceschini, Galetto, and Maisano Citation2019). Of course, personal attributes are also important factors affecting walkability, but this work concentrates on space and its walking-friendly attributes. The urban attributes below help verify the hypothesis that walkability can be designed and that spatial solutions can guarantee it.

The context of the transformation of project Carré de Soie

The connectivity of pedestrian paths in Carré de Soie, unlike in Księży Młyn, is more ensured by employing a holistic plan of connections. The large industrial quarters have adapted to contemporary needs: historically large quarters are divided into smaller units and streamline the connections from East to West and from North to South. The transit communication artery is located outside of the perimeter of the project, and the only road accessible to cars is also integrated with a tram line in a way that, while crossing it, pedestrians stop on designated islets that also serve the function of public transport stops (both tram and metro). Even if not all of the plans were fully executed, for example, the green path “promenade jardinée”, the actions taken have prevented any fundamental mistakes, such as dead ends or busy roads disrupting the connectivity of pedestrian paths.

In the Carré de Soie project, there was an attempt to execute the concept of an “îlot ouvert” – an open quarter, although in reality adapting this concept to residential buildings often involves at least small or transparent fences. Buildings closer to the local centre remain accessible from public spaces so that access and control in Carré de Soie results rather from the layout of the buildings than the use of physical barriers.

With regards to the visual interest, there are visible fundamental differences between Carré de Soie and Księży Młyn. The ground floors of target architecture are designed in a way that they are active and inviting for pedestrians. This concept relates not only to services, where shopfronts should resonate with pedestrians, but also to residential buildings. The following procedures were used: reserving ground floors on the sides of public spaces for services, elevating the ground floor of flats, and having small front yards in the inner parts of the quarters.

Comparing Carré de Soie to Księży Młyn, there are evident differences in terms of how the streets are equipped. Street furniture is more fitting to the needs of the user, not simply added in quantity. In Carré de Soie, the factors attracting users are certainly the modern design of the street furniture and their layout, grouping them into kinds of urban interiors. Convenience of use, however, is driven down due to construction work being carried out in Carré de Soie. There are no clearly marked pedestrian passages, since part of the route is a construction site. It is important to note that this is just a temporary state, but it remains a significant factor.

As in Księży Młyn, there are a significant number of new buildings in Carré de Soie, though the historical identity is still ever-present. The purpose of this is to connect the past of the researched place with its modern use. Such an approach is reflected in the buildings of the former TASE factory, which, after its revitalisation, currently houses the engineering company TECHNIP.

When evaluating the mixed use in Carré de Soie, it is perhaps significant that, when looking at the whole area, the variety of functionalities is very wide, but the diversity of use is lower in separate building clusters. Office buildings are located alongside communication axes, residential buildings are further away, and the shopping centre is a separate space. In the newly designed parts of the space, there are also adequate civil facilities, such as schools and concert halls.

It is worth noting that in France, mixed-housing is guaranteed by the national law (Solidarité Renouvellement Urban) and also by local zoning plans. Public investment in the tramway and metro line (T3, Leslys, Métroligne A) was a driving force behind the revitalisation of Carré de Soie. Public spaces related to this investment became especially well maintained. Moreover, new investments were complemented with civil facilities, such as schools and a concert hall, based on the assumption that the public realm is an additional incentive for real estate developers to invest in this post-industrial area. The shopping centre is another important traffic generator, though its closed layout has questionable implications for walkability. The shopping centre exists in the space as a barrier, rather than a transit area.

The assumptions of the Carré de Soie urban regeneration project are directly linked with the development of public transport. The fact that this area is located in two communes (Vaulx-en-Velin and Villeurbanne) was taken as a challenge, with the project becoming an extension of the centre of the Lyon agglomeration. There is a joint effort by Grand Lyon and the communes to try to improve the accessibility of Carré de Soie from the centre of Lyon, using a new tram, metro line, and upgraded bus network. In addition, the Rhônexpress/Les lys has improved transport links with Lyon–Saint Exupéry Airport. Those investments are very costly but strategic for the revitalisation of a distressed area. It is also worth noting that the location of the basic public transport axis in the centre of the Carré de Soie project ensures it has good access.

Most of the area of Carré de Soie is not a special pedestrian zone. The only exception is an inner passage in the commercial centre and the square in front of the office centre by the main communication route. The presence of cars in designated parking spaces is visible in the area, though they do not dominate the space, like in certain parts of Księży Młyn. Together with the introduction of a new local plan (PLU-H; Plan Local d’Urbanisme et de l’Habitat), effective from mid-2019, changes to the parking policy were introduced. These rules regulate the number of parking spaces available, depending on the distance from public transport stops (metro, tramway, high-level bus). Those changes are in line with the principles of the revitalisation project of Carré de Soie, limiting the space designated for parking, especially around residential areas.

Carré de Soie can be evaluated as well-maintained. The area is tidy and the level of wear and tear related to everyday, normal use differs between locations – with newer investments obviously being more attractive in this aspect.

Observations about accessibility to users with mobility challenges are very similar to those from the case in Łódź. The majority of pavements are adapted to the needs of persons in wheelchairs; there are no high obstacles. However, there is an absence of markings for persons with sight deficiencies. In addition, there are construction works that force pedestrians to cross the street, i.e. posing an obstacle.

The French case study confirms the importance and validity of the urban attributes applied in the analysis. With reference to those, it must be mentioned that the Carré de Soie project is being carried out by Grand Lyon. The coherence of the urban quality is, therefore, ensured by the presence of a single unit dealing with project management, architecture, urbanism and “sustainable development”, obviously diversified from one investment to the next.

Walkability and its conditioning in Księży Młyn

From the presented diagrams (), it can be seen that walkability in the researched area (about 75 ha) varies greatly. Based on diagrams of pedestrian traffic, the area can be divided into several parts, varying in terms of intensity of use. What is a little surprising, however, is that the pedestrian traffic in separate time brackets does not vary significantly, even though the area includes housing parts that logically should be less active during working hours, i.e. between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. Pedestrian traffic at weekends is much less intensive than on working days, while the office and warehouse parts of the area were not excluded from the study of the weekend traffic intensity.

Figure 5. The intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn between 6 a.m. and 10 a.m. (number of transits/day/m2)

Figure 6. The intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. (number of transits/day/m2)

Figure 7. The intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn between 4 p.m. and 7 p.m. (number of transits/day/m2)

Figure 8. The intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn between 7 p.m. and 11 p.m. (number of transits/day/m2)

Figure 9. Average intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn on working days (number of transits/day/m2)

Figure 10. Average intensity of pedestrian traffic in Księży Młyn on weekends (number of transits/day/m2)

Of course, the hottest points of pedestrian traffic intensity are located around easy to predict places near to street intersections (e.g. Abramowskiego and Kilinskiego Streets, or Tymienieckiego and Przędczalniana Streets). Apart from those, a higher intensity of traffic is visible around the square in the open housing zone (A), the greenery zone in the closed gate community (B), the road between both housing zones and the local commercial centre (C), the street crossing (D), the park exit (E), and the entrance to the housing zone (F). It is also worth looking at places commonly avoided by pedestrians: the area of the Special Economic Zone (a), the border of the housing zone (b), the park (c), the pedestrian passage (d), the closed gate of the Science Institute (e), the generally accessible housing zone (f).

Evaluating the urban attributes in the Księzy Młyn area in the order of , the analysis makes it clear that there is no global vision for the connectivity of pedestrian paths. Though connectivity works at the level of a single investment, there is insufficient connectivity in terms of the wider urban system.

Table 1. Urban attributes and its determinants

Evaluating access and control, it seems that the majority of researched areas are public spaces with no access restrictions. However, almost all the remaining housing investments and research zone are completely closed areas with strict access restrictions.

Visual interest remains a significant concern in Księży Młyn. Most contemporary housing complexes are designed leaving the ground level of the building as a blind wall. Historical residential buildings present themselves slightly better in terms of visual interest, since there are interesting windows located just above the pedestrian level and coherently linking the ground floor to the surroundings. The visual interest of green areas is low, since the zones are mostly limited by walls and fences instead of open air cafes or flat interiors corresponding with nature. Monofunctional zones such as the Special Economic Zone and Science Institute are not designed to be attractive for pedestrians, with ground floors consisting mostly of technical entrances and the wall of the technical buildings.

When evaluating comfort of use in Księży Młyn, the low quality of spatial elements such as street furniture, greenery, and pavements becomes notable. In most of the researched cases, at least one element significantly differs from standards of comfort. For example, if the area has convenient pedestrian crossings and sufficient greenery, then the location of the street furniture is questionable. Cars parked along the streets and blocking the way, even on relatively wide pavements, is a common problem. On public roads there are no benches or other street furniture. The park and pedestrian passages are balanced in terms of the amount of pavements, greenery, and street furniture, though these elements can hardly be called attractive or comfortable.

In terms of historical identity, the spirit of the past is present through the original urban system, materials corresponding to those used in the past, or simply the presence of original buildings, or preserved fragments of those buildings. The adaptation of some historical elements remains controversial, e.g. loss of continuity of original buildings or pedestrian routes, or use of poor quality contemporary materials intended to correspond to more durable ones used in the past.

The analysed area in Księży Młyn performs various functions, but in reality, it forms a complex of monofunctional systems located near to each other: residential buildings, scientific centre, or production centre. In order to achieve a real mixed-use area, there needs to be a network of relatively evenly spread accompanying functions. Currently, they are present only in scarce local services centres containing only commerce and not serving any civic purpose. Beside the research centre and conference centre located in the Special Economic Zone, there are no other civic facilities.

Communication in the researched area is very important and is partially provided by available public transport. The average distance of any given spot from the nearest public transport stop is approx. 250 m, and the key locations in the city are accessible. This is undermined by the fact that there are only buses available and they are too infrequent, meaning that the efficiency and frequency of public transport in the area is much worse than its accessibility. The lack of efficient public transport is even more inconvenient, since most of the researched area is, in theory, a low traffic zone with priority for pedestrians. It should not be surprising, therefore, that those pedestrian zones are experiencing problems with cars overflowing the designated parking spots and taking over open spaces. Parking rules enforced in the area allow for free of charge parking, e.g. around the public square, or roadsides. In places where parking is not prohibited, cars are parked along only one side of the street.

In terms of maintenance, the area is varied. In most public places the pedestrian areas are in need of some renovation, e.g. pavements are tidy, but their surface is uneven.

The last aspect evaluated in Księży Młyn is accessibility for users with mobility challenges. The entire area lacks any aids for the visually impaired. Most of the area is free from high obstacles, but the pavements are not adapted to be convenient for wheelchair users, with the exception of public green areas and new private investments.

The extremely positive (A-F) and extremely negative examples (a-f) of the places mentioned above were evaluated based on the characteristics of the urban attributes(1–10) defined in . illustrates the score obtained by the individual sites against the selected urban attributes ( where a given place is fully in line with its desired urban attribute;

where a given place is fully in line with its desired urban attribute; means 75% compliance;

means 75% compliance; means 50% compliance;

means 50% compliance; means 25% compliance). Moreover, the chart below presents the cumulated score of all urban attributes for each place (A-F and a-f), assuming that the maximum total score is 40 points (10 urban attributes, each with up to 4 points determining the use of that urban attribute).

means 25% compliance). Moreover, the chart below presents the cumulated score of all urban attributes for each place (A-F and a-f), assuming that the maximum total score is 40 points (10 urban attributes, each with up to 4 points determining the use of that urban attribute).

Table 2. The qualitative score of the places (letters A-F and a-f) against urban attributes (1–10)

Conclusion

The results from the presented research show that coherence, in terms of the way of conducting investments and the kinds of actions undertaken, is key. Based on the arguments presented above, the Carré de Soie project is considered by researchers as being a success in most of the urban attributes categories. Therefore, benefiting from experience gained from the French case, it is worth introducing certain improvements in this scope to the project in Łódź. This is because Łódź not only lacks a dedicated body managing the revitalisation of Księży Młyn but is also missing a development plan integrated with the city as a whole, creating a pedestrian-friendly urban pattern.

Solid arguments in favour of achieving analysing walkability from a holistic approach (social, economic, and environmental) could be fulfilled thanks to a reference guide by Speck (Citation2018), as well as the work of Duany, Plater-Zyberk, and Lydon (Citation2010). Taking a holistic approach to the division of large industrial quarters would allow dead ends to be eradicated, while also implementing coherent pedestrian pathways. According to a study conducted by Ewing and Cervero (Citation2001, Citation2010), the measure of block size is among the most predictive elements of walkability. The connectivity of pedestrian paths should be improved also in terms of increasing the attractiveness of windowless walls and reducing the feel of overwhelming fences. Such actions would also influence the access and control of the area. This would lead to limiting closed gate communities as much as possible. Where separating inner areas is necessary, it should ideally be done using the layout of buildings rather than using physical barriers.

Considerable improvements in terms of visual interest are needed in Księży Młyn. The crucial rules of the New Urbanist movement confirm this argumentation (Sucher Citation2003), as well as the classic arguments raised by J. Ghel (Citation2010). It is necessary to increase the number of shopfronts and to introduce attractive ground floor levels of residential buildings. The latter could be achieved, for example, using the sort of interventions employed in Carré de Soie: elevated ground floors, dedicating street-facing ground floor spaces to commerce, and small front yards on the inner side of the quarters.

It is also important to improve the quality of street furniture, both in terms of the design of the elements and their placement. Clearing pavements from cars blocking the pathway would drastically improve the convenience of use. Improving pavements and never allowing front parking creates useful space between the street and the buildings, thereby ensuring helpful walkability rather than harmful (Speck Citation2018, p.185, 200). Relating to the historical elements creating the historical identity, it must be noted that both the analysed areas fully utilise their potential. The definition of urban regeneration that takes account of historical heritage is fulfilled (Couch, Sykes, and Börstinghaus Citation2011). It could only be reflected upon how to derive more value from the post-industrial heritage and how to avoid questionable actions towards the historical elements, such as partially burying old storage units in the ground.

There could certainly be improvements in the mixed-use aspect, especially in the smaller clusters of buildings that are currently homogeneous. It is also worth considering ways of utilising tools that will stimulate functional diversification and mixed housing, which was proven to work in the French case. Developing urban regeneration through mixed-use schemes has also been confirmed through the research conducted by Chiua, Leeb, and Wanga (Citation2019). Those tools may be in the form of stipulations of local law or attractive real estate prices serving as an incentive for potential buyers.

It is also important for the city authorities to understand that investment in the public realm is a real incentive for private investors. There is a strong need for civil facilities in Księży Młyn, especially as they are scarce at the moment, and they can measurably increase the standard of the area. In addition, the services are in need of improvements, especially those providing the essentials. In both examined cases, not only are the services not evenly distributed across the area but also the places where those services are provided are often not attractive (both the offering and the place itself).

The approach to public transport is also incredibly important. The existing studies provide solid arguments that urban regeneration projects improving public transportation systems lead to an increase in walking and cycling (Balaban Citation2013; Edwards and Tsouros Citation2006). In Carré de Soie, public transport links form a cornerstone of the revitalisation project, while a dramatically different approach is visible in Łódź. Without an attractive public transport offering in place to efficiently connect Księży Młyn with the city centre, there will be no viable alternative for cars. As can be seen in the French case, the positioning of the basic communication axis in a way that it is equally accessible for the entire area is very important. In both the examined cases, pedestrian zones need improvements. They are scarce and isolated from one another, which is an impediment to continuous pedestrian communication in basic directions.

With regards to the parking policy, Łódź needs to implement certain changes. The method implemented in France would be advisable, where the number of designated parking spaces directly depends on the distance from the public transport stops. It significantly decreases the numbers of cars parked in public spaces. Such a policy could have considerable benefits, since parking a car is a process that is the largest factor contributing to wearing of the street and pavement surface in Księży Młyn. Considering the parking strategy, arguments have already been established by Donald Shoup (Citation2011). This would impact the maintenance of pedestrian pathways in the area.

To close off the list of recommendations resulting from the conducted analysis, the areas should better relate to the needs of users with mobility challenges. As underlined by Edwards and Tsouros (Citation2006), those needs have to be spatially taken into account in neighbourhood renewal schemes. There are changes that ought to be made in order to adapt the whole area to the needs of persons in wheelchairs, and it seems clear that markings for persons with sight deficiencies need to be installed.

The results of the presented study support the view that restoring buildings leads to improvements in the urban attributes discussed in this paper, such as mixed use and enhanced walkability in the area. Moreover, even relatively simple things, such as the pavement design, can help meet the needs of all pedestrians, which directly influences the equitable use concept (Aghaabbasi et al. Citation2019; Sua et al. Citation2019), which is not yet present in the case study areas. On the other hand, the results also support the hypothesis of Wells and Yang (Citation2008), whereby “neighbourhood features alone, such as pavements […], may not be enough to affect walking” (M. Kashef, pp.43).

Comparing Księży Młyn to the Carré de Soie project, it is possible to form the thesis that, in order to improve walkability in a revitalised area, synergy between all the presented urban attributes is key. The research confirms that optimising the relationship between pedestrian movement and urban form is possible, but requires that a holistic approach be maintained. Satisfying one or two aspects of urban attributes does not guarantee that an area will have good walkability. When improving walkability in post-industrial areas, a range of closely connected and harmoniously managed actions need to be implemented, rather than remedies for a single urban attribute at a time. Only this approach can transform the area into a pedestrian-friendly environment.

This approach is even more important, since in other parts of Europe, the conditions for urban regeneration are often similar, with or without a repeat of the success story in the revitalisation process. It is therefore worth considering the benefits of creating, as was done in the US (for example, the Hope VI programme), a system of structural support based on the principles of NU for the renewal process. In addition, given the current dynamic migration into large agglomerations, which are meaning that a country’s cities and towns are constantly changing, there is ample opportunity to return to the benefits from the walkable values of European urban tradition, to which NU precisely refers. The urban attributes examined in this paper are a firm part of the principles of NU. Improving those attributes gives revitalised areas a chance for development, though a fragmented approach can become a realistic threat, suggesting a false notion that the revitalisation is completed, while it has really only just started.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Young Scientists Fund, Lodz University of Technology, ID: WBAS/MN/7/2018. The author is grateful to Prof. Lydia Coudroy de Lille from UFR Temps et Territoires, Département de Géographie, Université Lumière Lyon 2 for valuable scientific disscussions. The author thanks Izabela Olejnik and Izabela Szmidt from Lodz University of Technology for their assistance in accessing bibliographical resources. Moreover, the gratitude must be expressed to my husband for his support in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Monika Maria Cysek-Pawlak

PhD. Eng. Arch. Monika Maria Cysek-Pawlak is an assistant professor at the Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Lodz. She is also a practicing architect and urban planner. She has been working for a renowned French company in Warsaw. Her work focuses on urban regeneration in strategic locations in Poland and France. She studied French and Polish urban issues during a double PhD program in École Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture et de Paysage, Université Lille 1 and Technical University of Lodz.

Marek Pabich

Prof. D.Sc. Ph.D. Arch. Marek Pabich is director of the Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Lodz Author of publications on the architecture of art museums, revitalization and the history of architecture. Author of university buildings, including a new facility for Lodz Film School and buildings of four faculties for Technical University of Lodz , museum facilities - Museum of Photograpy (under construction). Member of the Architecture and Town Planning Committee of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

References

- Addy, C. L. 2004. “Association of Perceived Social and Physical Environmental Supports with Physical Activity and Walking Behavior.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (3): 440–443. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.3.440.

- Aghaabbasi, M., M. Moeinaddini, Z. Asadi-Shekari, and M. ZalyShah. 2019. “The Equitable Use Concept in Sidewalk Design.” Cities 88: 181–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.10.010.

- Agirbas, A. 2020. “Characteristics of Social Formations and Space Syntax Application to Quantify Spatial Configurations of Urban Regeneration in Levent, Istanbul.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 35 (1): 171–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09671-1.

- Alfonzo, M. A. 2005. “To Walk or Not to Walk? The Hierarchy of Walking Needs.” Environment and Behavior 37 (6): 808–836. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916504274016.

- Antonini, G., M. Bierlaire, and M. Weber. 2006. “Discrete Choice Models of Pedestrian Walking Behavior.” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 40 (8): 667–687. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trb.2005.09.006.

- Arellana, J., M. Saltarín, A. M. Larranaga, A. Alvarez, and C. A. Henao. 2020. “Urban Walkability considering Pedestrians’ Perceptions of the Built Environment: A 10-year Review and a Case Study in a Medium-sized City in Latin America.” Transport Reviews 40 (2): 183–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2019.1703842.

- Audirac, I., and A. H. Shermyen. 1994. “An Evaluation of Neotraditional Design’s Social Prescription: Postmodern Placebo or Remedy for Social Malaise?” Journal of Planning Education and Research 13 (3): 161–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X9401300301.

- Badland, H. M., G. M. Schofield, and N. Garrett. 2008. “Travel Behavior and Objectively Measured Urban Design Variables: Associations for Adults Traveling to Work.” Health & Place 14 (1): 85–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.05.002.

- Balaban, O. 2013. “The Use of Indicators to Assess Urban Regeneration Performance for Climate-Friendly Urban Development: The Case of Yokohama Minato Mirai 21.” In Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development. Strategies for Sustainability, edited by M. Kawakami, Z. Shen, J. Pai, X. Gao, and M. Zhang, 91–115. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bereitschaft, B. 2018. “Walk Score® versus Residents’ Perceptions of Walkability in Omaha, NE.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 11 (4): 412–435.

- Bhattacharya, T., S. Dasgupta, and J. Sen. 2020. “An Attempt to Assess the Need and Potential of Aesthetic Regeneration to Improve Walkability and Ergonomic Experience of Urban Space.” In Advances in Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure. AHFE 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, edited by J. Charytonowicz and C. Falcão. Vol. 966, 358–370. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20151-7_34

- Boryczka, E. 2011. “Warsztaty Z Mieszkańcami Księżego Młyna.” In Projekt ‘Nasz Księży Młyn’ Raport, edited by E. M. Boryczka, 132–149. Łódź: Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami.

- Bottero, M., and G. Mondini. 2017. “Assessing Socio-Economic Sustainability of Urban Regeneration Programs: An Integrated Approach.” In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions. SSPCR 2015. Green Energy and Technology, edited by A. Bisello, D. Vettorato, R. Stephens, and P. Elisei, 165–184. Cham: Springer.

- Cabrera, S. A. 2019. “When Bourgeois Utopias Meet Gentrification: Community and Diversity in a New Urbanist Neighborhood.” Sociological Spectrum 39 (3): 194–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2019.1645065.

- Calthorpe, P. 1993. The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Cerin, E. 2007. “Destinations that Matter: Associations with Walking for Transport.” Health & Place 13 (3): 713–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.11.002.

- Chandraa, S., and A. K. Bharti. 2013. “Speed Distribution Curves for Pedestrians during Walking and Crossing.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 104 (2): 660–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.160.

- Chiua, Y.-H., M.-S. Leeb, and J.-W. Wanga. 2019. “Culture-led Urban Regeneration Strategy: An Evaluation of the Management Strategies and Performance of Urban Regeneration Stations in Taipei City.” Habitat International 86: 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.01.003.

- Clark, J., and V. Wright. 2018. “Urban Regeneration in Glasgow: Looking to the past to Build the Future? The Case of the ‘New Gorbals’.” In Urban Renewal, Community and Participation, edited by J. Clark and N. Wise, 45–70. Cham: Urban Book Series, Springer.

- Coletti, R., and C. Rabiossi. 2020. “Neighbourhood Branding and Urban Regeneration: Performing the ‘Right to the Brand’ in Casilino, Rome.” Urban Research & Practice 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2020.1730946.

- Couch, C., O. Sykes, and W. Börstinghaus. 2011. “Thirty Years of Urban Regeneration in Britain, Germany and France: The Importance of Context and Path Dependency.” Progress in Planning 75 (1): 1–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2010.12.001.

- Crescenzo, M., M. Bottero, M. Berta, and V. Ferretti. 2018. “Governance and Urban Development Processes: Evaluating the Influence of Stakeholders through a Multi-criteria Approach-The Case Study of Trieste.” In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions. SSPCR 2017. Green Energy and Technology, edited by A. Bisello, D. Vettorato, P. Laconte, and S. Costa, 503–522. Cham: Springer.

- Cysek-Pawlak, M. M. 2018a. “Mixed Use and Diversity as a New Urbanism Principle Guiding the Renewal of Post-industrial Districts. Case Studies of the Paris Rive Gauche and the New Centre of Lodz.” Urban Development Issues 57 (1): 53–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/udi-2018-0017.

- Cysek-Pawlak, M. M. 2018b. “The New Urbanist Principle of Quality of Life for Urban Regeneration.” Architecture Civil Engineering Environment 11 (4): 21–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.21307/ACEE-2018-051.

- Cysek-Pawlak, M. M. 2019. “Testing the New Urbanism Principle of Sustainable Transport in the Contemporary Redevelopment Projects. Lessons from Clichy-Batignolles in Paris and the Station Area in Lodz.” Journal of Urban and Regional Analysis XI (1): 35–52.

- Darchen, S. 2019. “Contextual and External Factors Enabling Planning Innovations in a Regeneration Context: The Lyon Confluence Project (France).” International Planning Studies 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1626220.

- Day, K. 2003. “New Urbanism and the Challenges of Designing for Diversity.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 23 (1): 83–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X03255424.

- Duany, A., and E. Plater‐Zyberk. 1991. Towns and Town‐making Principles. New York: Rizzoli.

- Duany, A., E. Plater-Zyberk, and J. Speck. 2010. Suburban Nation : The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream. New York: North Point Press.

- Duany, A., E. Plater-Zyberk, and M. Lydon. 2010. The Smart Growth Manual. NY: Mc Graw Hill.

- Dusza-Zwolińska, E., and A. Kiepas-Kokot. 2018. “Inner-city Brownfields-genesis, Specifics of Contamination, Possibility of Renewal.” Folia Pomeranae Universtitatis Technologiae Stetinensis Agricultura Alimentaria Piscaria et Zootechnica 343 (3): 11–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.21005/AAPZ2018.47.3.02.

- Dutton, J. A. 2000. New American Urbanism: Re‐forming the Suburban Metropolis. Milano: Skira Architecture Library.

- Edwards, P., and A. Tsouros. 2006. Promoting Physical Activity and Active Living in Urban Environments. The Role of Local Governments. Turkey: WHO Europe.

- Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2001. “Travel and the Built Environment: A Synthesis.” Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1780 (1): 87–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.3141/1780-10.

- Ewing, R., and R. Cervero. 2010. “Travel and the Built Environment.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (3): 265–294. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944361003766766.

- Falanga, R. 2019. “Formulating the Success of Citizen Participation in Urban Regeneration: Insights and Perplexities from Lisbon.” Urban Research & Practice 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2019.1607895.

- Ferri, B. 2017. “Social Sustainability in Urban Regeneration: Indicators and Evaluation Methods in the EU 2020 Programming.” In Recent Trends in Social Systems: Quantitative Theories and Quantitative Models. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, edited by A. Maturo, Š. Hošková-Mayerová, D. T. Soitu, and J. Kacprzyk, 75–88. Vol. 66. Cham: Springer.

- Fouseki, K., and M. Nicolau. 2018. “Urban Heritage Dynamics in ‘Heritage-led Regeneration’: Towards a Sustainable Lifestyles Approach.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 9 (3-4): 229–248.

- Franceschini, F., M. Galetto, and D. Maisano. 2019. Designing Performance Measurement Systems. Turin: Springer International Publishing.

- Furuseth, O. 1999. “New Urbanism, Pedestrianism, and Inner-city Charlotte Neighbourhoods.” South-eastern Geographer 39 (2): 145–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sgo.1999.0005.

- Ghel, J. 1971. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. New York: Island Press.

- Ghel, J. 2010. Cities for People. New York: Island Press.

- Girling, C., K. Zheng, A. Monti, and M. Ebneshahidi. 2019. “Walkability Vs. Walking: Assessing Outcomes of Walkability at Southeast False Creek, Vancouver, Canada.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 12 (4): 456–475.

- Gratz, R. B., and M. Norman. 1998. Cities Back from the Edge: New Life for Downtown. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gregorio Hurtado, S. 2019. “Understanding the Influence of EU Urban Policy in Spanish Cities: The Case of Málaga.” Urban Research & Practice 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2019.1690672.

- Gullino, S. 2009. “Urban Regeneration and Democratization of Information Access: CitiStat Experience in Baltimore.” Journal of Environmental Management 90 (6): 2012–2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2007.08.027.

- Güzey, Ö. 2009. “Urban Regeneration and Increased Competitive Power: Ankara in an Era of Globalization.” Cities 26 (1): 27–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2008.11.006.

- Hanz, M. 2015. “Poland - an Example of a Successful Rehabilitation Thanks to the Social Engagement.” In: Proceedings ISOCARP 2015, Cities Save the World. Let’s Reivent Planning, Amsterdam - Rotterdam, 116–125.

- Hanzl, M. 2011. “KsiężyMłyn - Uwarunkowaniaurbanistyczneispołeczne.” In The Fifth International Conference on Advanced Geographic Information Systems, Applications, and Services, France, 108–113.

- Hemphill, L., J. Berry, and S. McGreal. 2004. “An Indicator-based Approach to Measuring Sustainable Urban Regeneration Performance: Part 1, Conceptual Foundations and Methodological Framework.” Urban Studies 41 (4): 725–755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000194089.

- Hemphill, L., S. McGreal, and J. Berry. 2002. “An Aggregated Weighting System for Evaluating Sustainable Urban Regeneration.” Journal of Property Research 19 (4): 353–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09599910210155491.

- Higgins, E. M., and K. Swartz. 2018. “Edgeways as a Theoretical Extension: Connecting Crime Pattern Theory and New Urbanism.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 20 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0021-8.

- Iravani, H., and V. Rao. 2020. “The Effects of New Urbanism on Public Health.” Journal of Urban Design 25 (2): 218–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1554997.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House.

- Jarczewski, W., and M. Dej. 2015. “Rewitalizacja 2.0. Działania Rewitalizacyjne…w Regionalnych Programach Operacyjnych 2007–2013 – Ocena W Kontekście Nowego Okresu Programowania.” Studia Regionalne I Lokalne 1 (59): 104–122.

- Kaczmarek, S. 2015. “Skuteczność Procesu Rewitalizacji. Uwarunkowania, Mierniki, Perspektywy.” Studia Miejskie 17: 27–35.

- Kashef, M. 2011. “Walkability and Residential Suburbs: A Multidisciplinary Perspective.” Journal of Urbanism International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4 (1): 39–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2011.559955.

- Katz, R. 1994. The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Kazimierczak, J. 2014. Wpływ Rewitalizacji Terenów Poprzemysłowych Na Organizację Przestrzeni Centralnej W Manchesterze, Lyonie I Łodzi. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

- Kazimierczak, J., and E. Szafrańska. 2019. “Demographic and Morphological Shrinkage of Urban Neighbourhoods in a Post-socialist City: The Case of Łódź, Poland, Geografiska Annaler: Series B.” Human Geography 101 (2): 138–163.

- Kobojek, G. 1998. KsiężyMłyn -królestwoscheiblerów. Łódź: TONZ.

- Korkmaz, C., and O. Balaban. 2020. “Sustainability of Urban Regeneration in Turkey: Assessing the Performance of the North Ankara Urban Regeneration Project.” Habitat International 95: 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102081.

- Kostešić, I., J. Vukić, and F. Vukić. 2019. “A Comprehensive Approach to Urban Heritage Regeneration.” In Cultural Urban Heritage, Edited by M. Obad Šćitaroci, B. Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, A. Mrđa. Cham: Springer.

- La Rosa, D., R. Privitera, L. Barbarossa, and P. La Greca. 2017. “Assessing Spatial Benefits of Urban Regeneration Programs in A Highly Vulnerable Urban Context: A Case Study in Catania, Italy.” Landscape and Urban Planning 157: 180–192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.031.

- Lak, A., M. Gheitasi, and D. L. Timothy. 2020. “Urban Regeneration through Heritage Tourism: Cultural Policies and Strategic Management.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 18 (4):386–403.

- Larsen, K. 2005. “New Urbanism’s Role in Inner-city Neighborhood Revitalization.” Housing Study 20 (5): 795–813. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030500214068.

- Lehmann, S. 2019a. “Examples of the Ten Urban Regeneration Strategies in Practice.” In Urban Regeneration, edited by Lehmann, S., 157–215. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lehmann, S. 2019b. “Introduction: The Complex Process of City Regeneration.” In Urban Regeneration, edited by S. Lehmann, 1–54. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lichfield, D. 1992. Urban Regeneration for the 1990s. London: London Planning Advisory Committee.

- Lorens, P. 2010. Rewitalizacja Miast - Planowanie I Realizacja. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej.

- Lynch, A. J., and S. M. Mosbah. 2017. “Improving Local Measures of Sustainability: A Study of Built-environment Indicators in the United States.” Cities 60: 301–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.09.011.

- Lynch, K. 1984. Good City Form. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Majer, A. 2006. “Księży Młyn W Łodzi: Sentymentalizm Vs. Pragmatyzm.” In Rewitalizacja Kompleksu Księżego Młyna, Biuletyn KPZK PAN, Zeszyt 229, edited by T. Markowski, 49–57. Warszawa.

- Małagowski, A. 1998. “Śladami ‘Scheiblerowskie jlegendy’.” In Łódź Księży Młyn Historia Ludzi, Miescaikultury. Andrzej Małagowski, Magdalena Michalska, Cezary Pawlak; Edited by Elżbieta Fuchs. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi Rezydencja Księży Młyn.

- Markley, S. M. 2018. “New Urbanism and Race: An Analysis of Neighborhood Racial Change in Suburban Atlanta.” Journal of Urban Affairs 40 (8): 1115–1131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1454818.

- McCormack, G. R., L. Frehlich, A. Blackstaffe, T. C. Turin, and P. K. Doyle-Bake. 2020. “Active and Fit Communities. Associations between Neighborhood Walkability and Health-Related Fitness in Adult.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (4): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041131.

- Mecca, B., and I. M. Lami. 2020. “The Appraisal Challenge in Cultural Urban Regeneration: An Evaluation Proposal.” In Abandoned Buildings in Contemporary Cities: Smart Conditions for Actions. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, edited by I. Lami, 49–70. Vol. 168. Cham: Springer.

- Mussinelli, E., A. Tartaglia, D. Fanzini, R. Riva, D. Cerati, and G. Castaldo. 2020. “New Paradigms for the Urban Regeneration Project between Green Economy and Resilience.” In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective. Research for Development, edited by S. Della Torre, S. Cattaneo, C. Lenzi, and A. Zanelli, 59–67. Cham: Springer.

- Newman, P., and I. Jennings. 2008. Cities as Sustainable Ecosystems: Principles and Practices. Bibliovault OAI Repository, The University of Chicago Press, Island Press.

- Noworól, A. 2010. “Rewitalizacja Jako Wyzwanie Polityki Rozwoju.” In O Budowie Metod Rewitalizacji W Polsce - Aspekty Wybrane, edited by K. Skalski, 29–46. Kraków: Instytut Spraw Publicznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego w Krakowie.

- Parysek, J. 2015. “Rewitalizacja Miast W Polsce: Wczoraj, Dziś I Być Może Jutro.” Studia Miejskie 17: 9–25.

- Podobnik, B. 2011. “Assessing the Social and Environmental Achievements of New Urbanism: Evidence from Portland, Oregon.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4 (2): 105–126.

- Pontrandolfi, P., and B. Manganelli. 2018. “Urban Regeneration for a Sustainable and Resilient City: An Experimentation in Matera.” In Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2018. ICCSA 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, edited by O. Gervasi, B. Murgante, S. Misra, E. Stankova, C. M. Torre, Ana Maria A.C. Rocha, D. Taniar, B. O. Apduhan, E. Tarantino, and Y. Ryu, 10964. Cham: Springer.

- Qu, B., J. Leng, and J. Ma. 2019. “Investigating the Intensive Redevelopment of Urban Central Blocks Using Data Envelopment Analysis and Deep Learning: A Case Study of Nanjing, China.” IEEE Access, Special Section on Urban Computing & Well-being in Smart Cities: Services, Applications, Policymaking Considerations 7: 109884–109898.

- Reisi, M., M. A. Nadoushan, and L. Aye. 2019. “Local Walkability Index: Assessing Built Environment Influence on Walking. Bulletin of Geography.” Socio-economic Series 46 (46): 7–21.

- Ricciardelli, A. 2017. “Governance and Urban Regeneration.” In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, edited by A. Farazmand, 1–8. Cham: Springer. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20928-9_3220

- Roberts, P. 2008. “The Evolution, Definition and Purpose of Urban Regeneration.” In Urban Regeneration. A Handbook, edited by P. Robert and H. Sykes, 9–36. London: SAGE Publications.

- Roulier, S. M. 2018. “Democracy and Civic Ecology: New Urbanism.” In Shaping American Democracy, 157–178. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruggeri, D., C. Harvey, and P. Bosselmann. 2018. “Perceiving the Livable City.” Journal of the American Planning Association 84 (3–4): 250–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2018.1524717.

- Rundle, A. G., Y. Chen, J. W. Quinn, N. Rahai, K. Bartley, S. J. Mooney, M. D. Bader, et al. 2019. “Development of a Neighborhood Walkability Index for Studying Neighborhood Physical Activity Contexts in Communities across the U.S. Over the past Three Decades.” Journal of Urban Health 96 (4): 583–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-019-00370-4.

- Shoup, D. 2011. The High Cost of Free Parking. NY: Routledge.

- Skalski, K. 2007. “Programy Rewitalizacji W Polsce – Bilans, Perspektywy, Zarządzanie [Regeneration Programmes in Poland – Effects, Prospects, Management].” In Rewitalizacja Miast W Polsce. Pierwsze Doświadczenia [Urban Regeneration in Poland. First Experiences], edited by P. Lorens, 66–91. Warszawa: Biblioteka Urbanisty.

- Speck, J. 2018. Walkable City Rules: 101 Steps to Making Better Places. DC: Island Press.

- Stryjakiewicz, T. 2014. Kurczenie Się Miast W Europie Środkowo-wschodniej. Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Stryjakiewicz, T., R. Kudłak, P. Ciesiółka, B. Kołsut, and P. Motek. 2018. “Urban Regeneration in Poland’s Non-core Regions.” European Planning Studies 26 (2): 316–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1361603.

- Sua, S., H. Zhoua, M. Xua, H. Ru, W. Wang, and M. Wenga. 2019. “Auditing Street Walkability and Associated Social Inequalities for Planning Implications.” Journal of Transport Geography 74: 62–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.11.003.

- Sucher, D. 2003. City Comforts: How to Build an Urban Village. Seattle: City Comforts Press.

- Szafrańska, E., L. Coudroy de Lille, and J. Kazimierczak. 2019. “Urban Shrinkage and Housing in a Post-socialist City: Relationship between the Demographic Evolution and Housing Development in Łódź, Poland.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 34 (2): 441–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-018-9633-2.

- Talen, E. 2006. “Design for Diversity: Evaluating the Context of Socially Mixed Neighbourhoods.” Journal of Urban Design 11 (1): 1–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800500490588.

- Talen, E. 2010. “Affordability in New Urbanist Development: Principle, Practice, and Strategy.” Journal of Urban Affairs 32 (4): 489–510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00518.x.

- Talen, E. 2013. “Prospects for Walkable, Mixed-income Neighborhoods: Insights from U.S. Developers.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 28 (1): 79–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9290-9.

- Talen, E. 2018. Neighbourhood. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Talen, E. 2019. A Research Agenda for New Urbanism. Heltenham, Nothampton: Elgar.

- Talen, E., and J. Koschinsky. 2014. “Compact, Walkable, Diverse Neighborhoods: Assessing Effects on Residents.” Housing Policy Debate 24 (4): 717–750.

- Toli, M. A., and N. Murtagh. 2017. “Environmental Sustainability Indicators in Decision-making Analysis on Urban Regeneration Projects: The Use of Sustainability Assessment Tools.” ARCOM Conference, Cambridge, 165–175.

- Tomczak, A. 2008. Łódź Posiadławodno-fabryczne, Tom Drugi, Zalecenia Dla Ochrony I Kształtowania Struktury Przestrzennej. Łódź: Pracownia Planowania Przestrzennego Architekci T. Brzozowska, A. Tomczak Spółka Parnerska.

- Trudeau, D., and J. Kaplan. 2016. “Is There Diversity in the New Urbanism? Analyzing the Demographic Characteristics of New Urbanist Neighborhoods in the United States.” Urban Geography 37 (3): 458–482. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1069029.

- Vale, L. J. 2018. “Cities of Stars: Urban Renewal, Public Housing Regeneration, and the Community Empowerment Possibility of Governance Constellations.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 22 (4): 431–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2018.1455530.

- Vojnovic, I. 2014. “Urban Sustainability: Research, Politics, Policy and Practice.” Cities 41: S30-S44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.06.002.

- Wang, H., and Y. Yang. 2019. “Neighbourhood Walkability: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis.” Cities 93: 43–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.015.

- Wei Zheng, H., G. Qiping Shen, and H. Wang. 2014. “A Review of Recent Studies on Sustainable Urban Renewal.” Habitat International 41: 272–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2013.08.006.

- Wells, N. M., and Y. Yang. 2008. “Neighborhood Design and Walking: A Quasi‐experimental Longitudinal Study.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34 (4): 313–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.019.

- Wolfram, M. 2019. “Assessing Transformative Capacity for Sustainable Urban Regeneration: A Comparative Study of Three South Korean Cities.” Ambio 48 (5): 478–493. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1111-2.

- Wong, C. 2000. “Indicators in Use: Challenges to Urban and Environmental Planning in Britain.” Town Planning Review 71 (2): 213–239.

- Ye, Z. 2019. “Review of the Basic Theory and Evaluation Methods of Sustainable Urban Renewal.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 281 (12017): 1–8.

- Zuniga-Terana, A. A., P. Stokerb, R. H. Gimblettc, B. J. Orrc, S. E. Marshc, D. P. Guertinc, and N. V. Chalfound. 2019. “Exploring the Influence of Neighborhood Walkability on the Frequency of Use of Greenspace.” Landscape and Urban Planning 190: 1–12.