ABSTRACT

There has been much written about the “privatisation of public space”. This paper explores and challenges these narratives by questioning whether we have seen a privatisation at all. Through an analysis of historic and contemporary data, it concludes that, in London at least, we have actually witnessed the reverse, a “public-isation of private space”. The paper goes on to ask what are the management implications of the trend? It finds that the negative associations around privatisation are often misplaced and that public-isation processes have the potential to deliver a substantial net gain to society. At the same time, the public interest management implications are just as real for public-isation as for privatisation processes. Through action research the idea of public authorities adopting a charter of public space rights and responsibilities is tested in order that the potential benefits of public space projects are captured and negative impacts avoided.

1. Introduction

This paper is in four parts. First, the international literature and debates on the privatisation of public space are reviewed and used to contextualise the evidence that follows. This is not a simple picture and some of the complexities and contradictions in the literature are highlighted. Second, the London case is introduced, a location where issues regarding the privatisation of public spaces have been hotly debated over many years. Recent evidence on the phenomenon gathered by The Guardian newspaper is investigated and interrogated and the notion of the public-isation or private space is revealed. How this relates to the broader concern for publicness is discussed next before, third, action research focussed on generating a charter of public space rights and responsibilities is introduced and discussed, including how these ideas are being taken up in London. In a final part the paper concludes with a call for a more nuanced view of privatisation narratives and a recognition that, if properly regulated, public-isation processes have the potential to offer real benefits to society. They should not be rejected solely for narrow dogmatic or political reasons.

1.1. The privatisation of public space

At the heart of many of the critiques of contemporary public space is what has come to be known as the “privatisation of public space”. Over 40 years ago Sennett (Citation1977) documented the social, political and economic factors leading to a privatisation of people’s lives and the “end of public culture”. Later, Ellin (Citation1996, 149) observed how many of the social and civic functions that traditionally occurred in public spaces were being abandoned or usurped by private realms. Today, activities such as leisure, entertainment, information gathering, consumption and (for many) work, can increasingly be conducted at home through the television or internet – all activities exacerbated even further by the recent coronavirus pandemic. Activities once only available in collective and public forms have become available in individualised and private forms and a range of influential writers have argued that public space and other areas of public assembly are therefore less significant as a focus of people’s lives (Sorkin Citation1992; Mitchell Citation1995; Zukin Citation1991; Low and Smith Citation2006; Kohn Citation2004; Madden Citation2010).

Whilst such arguments can easily be overblown, Ellin (Citation1999, 167) observes how, when the public realm becomes impoverished, there is “a corresponding decline in meaningful space and a desire to control one’s space, or to privatise”. Epitomising this “privatisation impulse”, she calls out “the inward-turning shopping mall which has abandoned the central city for the suburbs and which turns its back entirely on its surroundings with its fortress-like exterior surrounded by a moat-like car park” (Ellin Citation1999, 168). Loukaitou-Sideris (1991 in Loukaitou-Sideris and Banerjee Citation1998, 87) notes how the desire of office workers, tourists and conventioneers to be separated from “threatening” groups, provides the market opportunity for spaces produced, maintained, and controlled by the private sector. Graham (Citation2001, 365) extends the association to the domain of everyday public streets, noting that “The municipally-controlled street systems that once acted as effective monopolies of the public realm in many cities, are being paralleled by the growth of a set of shadow, privatised street spaces”. Dovey (Citation2016, 158) sees these quasi-public spaces as providing “an alternate and somewhat sanitized version of public space” and “a replication and replacement of open-public space”. For him, “Privatization is a subtle and incremental process through which the private market appropriates everyday urban life”.

1.2. The forms privatisation takes

Noting the different forms that privatisation takes, Carmona (Citation2010a, 134–7) draws a basic distinction between i) corporate privatisation – the development, retention and management of spaces that might traditionally have been viewed as public by the private sector e.g. streets, green spaces, etc. – and ii) state privatisation – or the increasing role of private interests in the ongoing management of public assets, from whole neighbourhoods to individual spaces. Whilst the former stems from property rights linked to ownership and is permanent and outside the day to day control of the public sector, the latter is largely a partnership (De Magalhaes Citation2014) or contractual (De Magalhaes and Freire Trigo Citation2017) arrangement and is open to challenge and change by the public sector and is temporary (in the sense that it is limited by the length of the agreement).

Tracing the diverse forms of privatisation in New York, Zukin (Citation2018) notes three processes:

The introduction of Business Improvement Districts (BIDS) in key shopping areas and public parks with local businesses paying towards additional cleaning, policing, landscaping and promotional activities

The real estate development processes that flow from upgraded public realm projects which act to push out low-value, low-income and counter-cultural elements in favour of private property investments, for example around the High Line park

Construction of what Kayden (Citation2000) has christened Privately owned public spaces (POPS) in exchange for zoning bonuses.

The first is of the state privatisation variety. The second is more a gentrification than a privatisation given that the spaces concerned are likely to already be in private ownership, albeit in lower value uses. The resulting redevelopment processes may of course introduce new pseudo-public spaces into an area, e.g. for retail and leisure functions. The final category represents corporate privatisation and has been the subject of considerable scholarship, particularly in cities where the phenomenon is widespread such as New York, Hong Kong and London.

Although bonus spaces have been encouraged since 1961 in New York in an attempt to create more public space, Kayden’s (Citation2000) influential report identifying the poor quality of many of these spaces revealed that rather than encouraging use, many POPS seemed deliberately designed to discourage use; or at least – as their owners saw them – the ‘wrong sort of users”: the homeless, unruly or dishevelled. The City Planning Commission has since issued new rules to secure more useable, attractive and welcoming POPS, although Schmidt, Nemeth, and Botsford (Citation2011) report that this has not always been followed by day to day management practices that make them more open. Based on their empirical analysis of the operation of POPS in the city, Nemeth and Schmidt (Citation2011), for example, note that “privately owned spaces in New York, both encourage use and control behaviour” (more than their publicly owned counterparts). They support Kayden (Citation2005, 134) who has argued for better oversight of spaces as they come forward for redesign to ensure that they more successfully meet public aspirations for accessibility and inclusion ().

Figure 1. New York “bonus” plaza: The status of this space is clearly denoted by the small wall-mounted plaque in the middle of the picture which reads “Plaza rules of conduct: No smoking, No pigeon feeding, No rollerblading, No skateboarding, No loitering”. To address some of the criticisms of New York’s POPS, in 2017 a new law was passed requiring an annual report to the Mayor about the state of the city’s POPS, a programme of three yearly inspections, and the availability of clear information about all POPS both online and on site.

While New York features over 500 POPS (APOPS & MASNYC Citation2012), this concentration of privately owned and managed public spaces is dwarfed by Hong Kong where large parts of the city feature an almost continuous network of privately owned and managed internal shopping malls. Al (Citation2016, 7) writes that “Shopping is seamless in Hong Kong. Metro exits lead directly into malls and footbridges connect different malls so that pedestrians remain in a shopping continuum, not contaminated by the public ream”. At worst, he argues, “Hong Kong’s mall cities represent a dystopian future of a city after the ‘shopapocalypse’”. At best, they can be vibrant, diverse and interconnected developments that contribute a new form of public realm, and in which new public spaces are provided for the citizens, both on the roofs of the malls and in their generous atria. Elsewhere new publicly owned spaces around and adjacent to the malls have been designed solely to get people into the shopping and to encourage lingering. Al (Citation2016, 9) notes “the trick is to place the POP to get people to shop”.

Widely criticised in the academic literature, the different forms that privatisation takes, and the implications locally for everything from the cultural life of cities, to the freedoms of individuals, including the young, minorities and the homeless, to the right to protest or simply exist in public space without consuming or being surveilled vary hugely (Madden Citation2010). To take one example, occupation of public space as a form of demonstration became a feature of global protest following the Arab Spring of 2010, what Hristova and Czepczyński (Citation2018, 7) refer to as “an attempt to re-order (even though temporarily) the world and to reclaim the basic social contract between citizens and governing elites”.

In New York, the Occupy movement first set up camp in 2011 at Zuccotti Park, a POPS. There they were protected by the strong rights of access (day and night) that zoning regulations imbue on such spaces. Moreover, because the authorities did not have control over the space, the protestors could not be evicted for some time. The equivalent demonstrations in London occurred adjacent to St Paul’s Cathedral in a pseudo-public space; owned by the Church of England () (the protestors had previously been physically denied access to an adjacent privately owned public space – Paternoster Square). St Paul’s Churchyard gave protestors some protection because the space was outside the control of The City of London, and the Church was reluctant to evict them, instead preferring dialogue, despite having to effectively shut down the cathedral for much of the protest. In Hong Kong, the democracy protests of 2014 deliberately occupied publicly owned spaces, what Al (Citation2016, 13) refers to as “the little of what is left of Hong Kong’s public space on the ground”. There “They placed their tents smack in front of malls, on top of highways”, expressing something of the democratic importance of this space. Sheer weight of numbers allowed them to hold on for several months despite the use of the courts and police (and intimidation by triads) aimed at evicting them.

Figure 2. The Occupy protests in London, like New York, took place on privately owned and managed public space.

The right to protest often features in discussions on the privatisation of public space, but the different Occupy protests demonstrated that the role that ownership plays in supporting or denying these rights is not straightforward, with degrees of privatisation perversely helping in some circumstances to sustain protests, whilst elsewhere the reverse was true. A single one-size-fits-all understanding of privately owned and managed public spaces is clearly not appropriate.

1.3. A complex picture

Beyond the differences between cities, because space is often not entirely public or entirely private, and because publics are also diverse, a more nuanced set of analyses have also emerged that do not paint processes of privatisation as necessarily always good or always bad. Some commentators (Brill Citation1989; Krieger Citation1995) argue that perceptions of the public realm’s apparent decline are based on a false notion and that, in reality, the public realm has never been “as diverse, dense, classless, or democratic as is now imagined” (Loukaitou-Sideris and Banerjee Citation1998, 182). Other commentators note a resurgence in the use of public space – including private forms – seeing it as a process of socio-cultural transformation. Carmona (Citation2010b) suggests that whilst privatisation and commercialisation are often considered irreconcilable with the concept of public domain, that discrepancy is less absolute than it might seem. The fact that something is private rather than public, suburban rather than urban, or commercial rather than civic does not ipso facto determine either its quality as a place, or its potential role as part of the public realm.

Testing a range of public space critiques – including that of privatisation – Carmona (Citation2015, 26) has called for a new public spaces narrative. He argues “If the dominant narrative of public space over the neoliberal era has been one of loss, wrapped up in notions of ‘decline’ and reduced ‘publicness’ … this is certainly not the whole story, or even the dominant one”. Instead, we have also seen private-sector innovation in urban design-led (or at least urban design-aware) development and renewed political and public-sector interest in public space, with policy and investment focused once again on the public spaces of the city. Rather than loss, there is “a narrative of renewal, one that celebrates the return of a public spaces paradigm” and an acceptance that users are diverse and will seek different things from their spaces. Instead of pursuing an illusive ideal, the aim should be diversity in provision.

Studies exploring the production of privately owned and managed public spaces in the Netherlands, Germany, Turkey, South Africa, Hong Kong, New York and Santiago, for example, reveal a diversity of actors involved, types of spaces produced, production processes employed, and users and activities engendered (van Melik and van der Krabben Citation2016; Kutay Karac Citation2016; Landman Citation2019; Rossini and Hoi-lam Yiu Citation2020; Klemme, Pegeles, and Schlack Fuhrmann Citation2013; Huang and Franck Citation2018). They confirm the contention that “public space today is no longer (if it ever was) straightforwardly either open and public or closed and private” (Carmona Citation2015, 22). Instead, the subject is full of complexity and contradictions that defy any overly restrictive view of what public space should be. Public spaces are often shaped through complex partnerships between a wide range of players – public, pseudo-private (universities, churches and the like) and private – with motivations that are equally complex.

Based on her analysis of Liverpool One (a new shopping centre and associated public spaces in the centre of Liverpool) Leclercq (Citation2018) concludes that the privatisation of public space does not necessarily lead to private space, nor does a publicly led process automatically result in public space. Instead, compromises are involved and it may be that by working together that public and private interests can create a greater degree of publicness than either could create by themselves (Leclercq, Pojani, and Bueren Citation2020). At the same time, whilst most people perceive many privately owned and managed public spaces to be truly public and do not consciously discriminate in their minds as they move between ownerships, subconscious moderations to behaviour can be detected.

Similar studies in China (Shanghai and Chongqing) reveal “important differences in the design, manipulation and use of pseudo-public spaces”, but also that they have a critical role as part of a line between public and private that is blurring quickly in Chinese cities (Wang and Chen Citation2018, 231). In this regard, Leclercq (Citation2018) argues that “the commons, public spaces and pseudo-public spaces should not be seen as antinomies”, but are different, and that privately owned and managed spaces can never be as fully public as traditional ones, but instead have different and complimentary roles to play.

1.4. Research aims and methodology

Drawing this section of the paper to a close it is possible to conclude that there remains a widespread and ever-growing concern about what many see as the malevolent societal impacts of the so-called privatisation of public spaces. But these narratives, which remain dominant in the literature, are often over-simplified, and a growing body of evidence is suggesting that a more nuanced analysis should be taken. Privately owned and managed public spaces are not the same everywhere and instead exist on a continuum where, at one extreme, their presence may considerably curtail local freedoms, whilst, at the other, spaces actively invite and celebrate diversity, freedom and the essential publicness of cities.

To explore this further, the case of London is now taken up. The remainder of the paper aims:

First, to explore a debate that has been particularly vehement in London for over a decade with influential campaigners arguing against the private ownership and management of public spaces

Second, to examine the extent and validity of those objections, both as regards the spread of privatised public spaces and their publicness

Third, to advance options for reconciling concerns through the construction of a Charter of public space rights and responsibilities.

Three primary methodologies are used to explore the case. In the second part of the paper, secondary academic, popular and policy sources are used to establish the recent history of debates in London before primary data gathered by The Guardian newspaper on the extent of privatised public spaces in the city is subjected to re-analysis in order to better understand the efficacy of the case against privatisation. In the third part, action research is reported on that brought together public and private players to explore whether new policy approaches can be devised with a focus on addressing the long-term debates and guaranteeing the future publicness of London’s public spaces. To assist the flow of the narrative, the methodologies are discussed more fully at appropriate points in the text.

2. The London case

Despite empirical studies, such as those already referenced, being less charged with condemnation of the impact of privately owned and managed public spaces than political and polemical ones, these spaces have become the posterchild of opposition against wider forces of privatisation and the neo-liberal city. Koch and Latham (Citation2013, 19) point to “a tendency in urban scholarship to exaggerate the ubiquity and coherence of these forces” combined with “a tendency to overlook much of what actually goes on in public spaces”. This is certainly the case in London where campaigning journalists have succeeded in raising the issue up the policy agenda and keeping alive an important local debate. Unfortunately, it is a debate more often characterised by hyperbole and dogma than by clarity and pragmatism.

Crudely the debate can be represented as a tussle between two contrasting positions. On one side the debate has been spearheaded by The Guardian in a series of pieces which set out to map (Shenker Citation2017) and denounce (Garrett Citation2017) the privately owned and managed spaces that since the 1980s have featured at the heart of many regeneration projects across the city. This strand of opinion argues that privatisation of public space is always bad because:

London (like other large cities) is increasingly reliant on large powerful developers to create its public realm

These developers build the city in their own interests and are effectively privatising large parts of the city by retaining ownership and management responsibilities for streets and public spaces in perpetuity

They do so at the expense of citizens’ rights, some of whom are effectively excluded from freely using these spaces whilst other activities are restricted.

Rarely voiced publicly, but articulated privately by certain development interests, a counter-argument claims that the privatisation of public space is often desirable and should be welcomed. Its most vocal advocate has been Patrik Schumacher of London-based Zaha Hadid Architects who has gone so far as to argue that all streets, squares, public spaces and parks should be privatised (Frearson Citation2016). This, he suggests, will bring a new wave of entrepreneurial energy to their management (Renn Citation2018). The argument goes:

In a climate where the public sector increasingly struggles to devote adequate resources to the creation, let alone the management of public spaces, developers and investors have a legitimate interest themselves in helping to fill the gap

In so doing they are protecting their own investments by prioritising the needs of their clients (the occupiers) and will bring entrepreneurial spirit and innovation to the task

Privatisation also helps to save money for tax payers by taking on the cost of managing public spaces.

In London this debate came increasingly to the fore between 2000 and 2010 as the first and second Mayors of London (despite very different political leanings) adopted pro-growth policies and embraced the role of the market to deliver a wide range of regeneration and development projects. Citing concerns about the extent of London being privatised, Minton (Citation2009, 35), for example, wrote a persuasive polemic about what she saw as the spread of the Canary Wharf model across London and other British cities, culminating in what, for her, are places which are no longer inspired by the culture of where they are, but instead simply by their locational advantages and economic potential. Examples included Paddington Waterside, about which she writes “this private enclave the size of Soho, is all about office blocks and waterside apartments, with few shops and fewer people to be seen, although there is a very similar feel of sameness and sterility” to other corporate enclaves ().

Reflecting such concerns, the then Mayor – Boris Johnson – published London’s Great Outdoors which, amongst other things, argued that public space should remain “as unrestricted and unambiguous as possible” and that undue “corporatisation” of the city’s spaces should be avoided (Mayor of London Citation2009, 8). This was followed by the launch of the Public Life in Private Hands inquiry in 2010 by the London Assembly’sFootnote1 Planning and Housing Committee in order to explore issues surrounding the privatisation of public space.

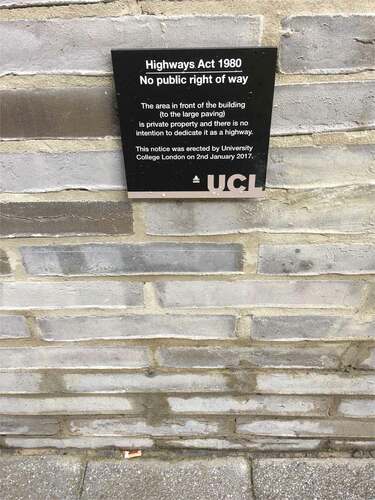

The inquiry coincided with a major academic study – Capital Spaces – examining public spaces in London (Carmona and Wunderlich Citation2012) which furnished the deliberations with empirical evidence that ultimately suggested a third position based on the pragmatic view that the situation is more complex than either of the polemical positions suggest. The research confirmed that, like other cities, London is full of privately owned but publicly accessible space, and always has been. Much of the city was built by private interests and whilst most streets are now in public ownership and management, public spaces are owned by a huge diversity of public authorities, public institutions, charitable trusts, private institutions, resident groups, private corporations and individuals. The upshot is that users move between ownerships and management responsibilities, often without realising it (), suggesting that arguments either to ban the private ownership and management of public space or to require it would equally depart from historical practices and evidence about the everyday experience of users. This is typical in other European cities as well, as recent research comparing London with Copenhagen, Malmö and Oslo has shown (Carmona et al. Citation2019).

Figure 4. This sign on the side of a university building in London denotes that part of the pavement – about half of it – is in fact private property, although few passers-by notice either the sign or the distinction.

The Inquiry backed the evidence, concluding “Londoners expect high quality, accessible, safe, well-maintained public spaces regardless of who owns or manages them. … While private ownership or management of public space is not, in itself, a cause for concern, a number of … problems can arise with spaces in which commercial interests prevail over public access”. They recommended that the Mayor issued guidance to the 33 London BoroughsFootnote2 and that they in turn should adopt local planning policy that gave more systematic consideration to long-term management issues as part and parcel of the development management of new projects (London Assembly Citation2011, 11–13).

The election of a new Mayor – Sadiq Khan – in 2016 and the launch shortly afterwards of The Guardian’s campaign brought the issue back onto the public agenda.

2.1. Be angry

In July 2017 The Guardian ran the headline “These Squares are Our Squares, Be Angry about the Privatisation of Public Space”. In a series of pieces the authors made an impassioned plea: “The public spaces of London, the collective assets of the city’s citizens, are being sold to corporations – privatised – without explanation or apology. The process has been strategically engineered to seem necessary, benign and even inconsequential, but behind the veil, the simple fact is this: the United Kingdom is in the midst of the largest sell-off of common space since the enclosures of the 17th and 18th century, and London is the epicentre of the fire sale” (Garrett Citation2017). They argued that public space should be a right, not a privilege, which should encompass free and open access, reflecting the democratic values guaranteed by collective ownership. Instead, almost every major redevelopment in London from the spaces around the Olympic Stadium, to King’s Cross to Nine Elms, has resulted in the privatisation of public space. They concluded “It is too easy to convince ourselves that when we lose one space we can just use another”. But “If this process continues as it has, there will be a day when all open-air space in London is privately owned, meaning corporations could effectively render protest illegal, a scenario which should send a shudder through even the most conservative observers” (Garrett Citation2017).

Supporting their arguments, what was referred to as the “first-ever comprehensive map of pseudo-public spaces in London” was published. In collaboration with Greenspace Information for Greater London, 57 spaces were identified that met a relatively narrow criteria for pseudo-public space: namely outdoor, open and publicly accessible locations that are owned and maintained by private developers or other private companies. The variety of spaces identified included public spaces around Paddington Station, nearly 3 ha of open space owned by Arsenal Football Club in Islington, shopping and dining plazas in Covent Garden and Victoria, and space around the London Eye (Shenker Citation2017). Little explanation was given regarding how spaces meeting the project’s definition were identified, and therefore about how systematic the search was.

2.2. Interrogating the dataset – underestimating the phenomenon

The Guardian dataset was made publicly available at the London Datastore (https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/privately-owned-public-spaces) allowing other researchers to interrogate it. Subjecting the data to further analysis reveals that the 57 spaces are – if anything – a significant underestimate of the phenomenon of privately owned and managed public spaces in London.

First, the list of spaces was compared against the dataset gathered in the Capital Spaces research a decade before (Carmona and Wunderlich Citation2012). The earlier dataset was generated following a request for data to the 33 Borough planning departments across London. These requests helped to identify over 230 spaces around the city that between 1980 and 2007 had either been newly created or had been substantially re-designed (with, at the time, a further 100 projects identified in the pipeline). On-site visual analysis of 131 of these (all of the spaces in 10 Boroughs chosen to reflect a distribution of Central, Inner and Outer London contexts) revealed 35 publicly owned and managed spaces, 3 entirely private (with no public access beyond visual access) and 93 in some form of intermediate status. The last of these categories were further divided between 33 owned by a public or pseudo-public body and managed in such a manner that some level of private restriction was imposed (e.g. closed for events) and 60 publicly accessible but owned and managed by private interests (the equivalent of those in The Guardian dataset), only 12 of which replicated those identified by the newspaper.

The comparison revealed just how partial the data interrogated by The Guardian was, in large part focussing on only well known corporate developments (e.g. Canary Wharf or Broadgate) and recent projects (e.g. the two new Westfield shopping malls) and omitting large parts of London known to have significant numbers of privately owned and managed spaces (e.g. Greenwich and Croydon). Although a full account of such spaces will have to await a comprehensive rigorously conducted survey, extrapolating across London from both surveys, it is likely that the city accommodates closer to 200 than to The Guardian’s 57 privately owned and managed public spaces built in the neo-liberal era (since 1980), plus many more in other pseudo-public categories.

Whilst these sorts of numbers seem to support the case that there has been a widespread “privatisation” of the city, seen in an historic light they are not surprising. To these need to be added all those privately owned and managed spaces built prior to 1980 that predominate in Georgian and Victorian London and in around many 20th and 21st century housing estates. They include the revitalised spaces of numerous estate regeneration projects across London (Urban Design London Citation2015), whilst Wikipedia lists just over 200 historic garden squares in London (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_garden_squares_in_London). Almost all of these were built as private amenities for the residents surrounding them, and most retain that private status, albeit many are now open to the public (https://londongardenstrust.org/conservation/inventory/) ().

Figure 5. St James’s Square, one of the earliest garden squares is managed by the St James’s Square Trust, set up by an act of Parliament in 1726 and funded by a special rate on the freeholders of surrounding properties paid in order to “clean, adorn and beautify” the square. The square is open to the public during set hours.

2.3. Interrogating the dataset – a conceptual distinction

More interesting than the numbers is the nature of the spaces identified by The Guardian, the interrogation of which reveals an important conceptual and practical distinction that suggests a different narrative, one more associated with an opening up of key parts of London to its citizens than its closing down. For a deeper dive the Digimap Edina database of historic maps was consulted which holds records of maps at scales including 1:500 and 1:1250 going back to 1848. For each of the 57 spaces and its surroundings, the new morphological pattern was graphically overlaid on its respective historic urban tissue (). Successive historic layers were traced back in order to understand the history of each site and whether they were formally i) publicly accessible ii) contained public spaces in public ownership. Because the historical maps contain details of land uses, built and unbuilt space, roads and routes networks, public and civic buildings and named public spaces, comparing former with current uses was a simple and robust means of gauging patterns of ownership and use. The historic mapping data was also compared, wherever possible, with planning records from the online planning portals of the relevant London Boroughs and with other online sources to ensure that the historic records were being correctly interpreted and to clarify ownerships when there was a doubt.

Figure 6. New and historic urban tissues overlaid for analysis, here at the More London development (Southwark).

Of the 57 spaces, only nine had been publicly accessible previously, in each case as part of a former privately owned and managed space on the site that had been redeveloped. In these cases the status of the spaces had not changed at all and in six of them the spaces were historic spaces from the 1930s and earlier that had not changed their physical form either. In the remaining 48 cases (spread evenly from the mid 1980s to 2010s, with four still in development), the identified public spaces now sit on sites that had been previously inaccessible for public use, either because the sites were fully developed with buildings (e.g. in commercial or wholesale uses), were being used as private open space (e.g. private gardens or allotments), or, most frequently, were in industrial uses whether built (e.g. warehouses and factories) or open (e.g. docks and railyards). All of these locations had been inaccessible to the public. shows the range of uses that existed prior to their redevelopment and whether they were publicly accessible or not. To summarise, those spaces that had been accessible to the public remained so with the same or similar ownership and management arrangements, and the remainder which had not previously been accessible (84% of The Guardian schemes) now were.

Table 1. Pre-existing uses and public accessibility

The new analysis revealed that – in London at least – the term “privatisation of public space” is both confusing and somewhat a misnomer because it implies that once publicly owned and managed space is becoming private – a “sell-off’ in The Guardian’s terms. None of the 57 Guardian cases exhibited such a transfer of responsibility from public into private hands. In fact, in London (like the rest of the UK) this happens only very rarely (). Instead, what has been seen over the past four decades was the opening up to public use of large parts of the city through redevelopment of formally private, walled and gated off areas of the city, notably former industrial areas and bits of redundant infrastructure. Rather than the new wave of enclosures portended (echoing the enclosure of agricultural land in England from the 16th century onwards), what has been witnessed is the bringing of new spaces into public use, even if it remains in private ownership.

Figure 7. The New Town, Milton Keynes has, since 1979, been dominated by its “Miesian-styled” enclosed shopping centre which is, in effect, the town centre. Built and initially owned by the New Town Corporation it was later transferred into private ownership. Since 2000 the centre was extended over and now encloses and takes control of a former public street – Midsummer Boulevard (the space shown here). This represents a rare example of the actual privitisation of formally publicly owned and managed land.

2.4. Public-isation, but what about publicness?

Arguably what has been witnessed is the reverse of that presaged in the headlines. Instead we have seen a widespread “public-isation of private space”, with the potential for very significant public gain when handled correctly. The huge King’s Cross development represents a case-in-point where the spaces being created from the former railway lands behind King’s Cross and St Pancras Stations have very quickly become well used and highly valued as a new and distinctive quarter of London. Whilst they vary in character (some being more corporate and high-end than others and criticised by some for this – Wainwright Citation2018) a deliberately relaxed approach to management and attempt to garner an inclusive and vibrant environment that gives back to society, including a rich programme of public events (e.g. 163 in 2016) has been a critical part of the successful economic model used by Argent, the developer/investor (Regeneris Citation2017) ().

Bishop and Williams (Citation2016) record how the key to the approach was a strategy that passed over ownership and management responsibilities for the streets that pass through the development to the London Borough of Camden whilst retaining ownership of the public spaces in order to help “make the place”. This gave rise to a much higher standard of specification and programming than would have been possible if the equivalent spaces had been adopted by the London Borough of Camden with its limited budget and complex set of social priorities.

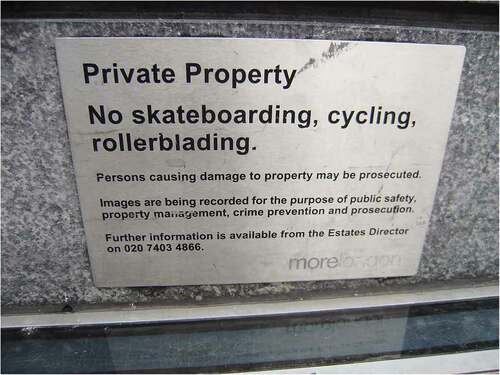

Equally, there have been many cases were this public-isation has not been so wholehearted and explicit. City Hall (home to the Mayor), for example, is part of the private More London estate (see ) owned by St Martins Property Investments (the UK investment arm of the Kuwaiti state) which over the years had repeatedly denied permission for bike racks to be located on-site and whose permission had to be sought before the Mayor and politicians of the London Assembly could conduct interviews outside the building (Walker Citation2007) (). Many stories exist of seemingly petty restrictions being enforced in this and other privately owned and managed developments, often for little apparent reason ().

Figure 10. Needless restrictions apply in this privately owned space outside the Town Hall of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, here the security guard is saying “no photos allowed” to the author.

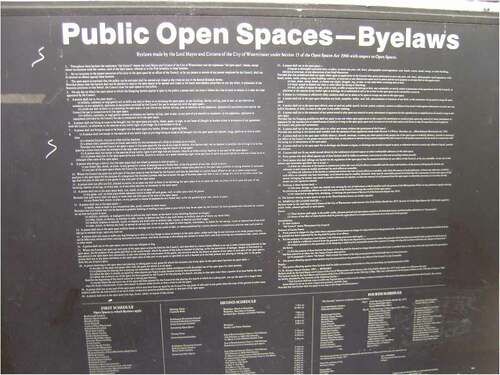

Garrett (Citation2017) argues, “In most of these pseudo-public spaces, the property owners refuse to post what ‘rules’ are enforced on the property, meaning that often you only know you breach them when you are told you have done so, and that they may in fact be making them up on the spot. Considering that these rules have been used to preclude protest, journalism and to curtail freedom of speech, as well as to generally exclude fellow citizens including cyclists, skateboarders, buskers and the homeless, how can we perceive of the creation of these spaces as anything but an attack on our fundamental rights as citizens?” Looking at the issue from an alternative viewpoint, many publicly owned and managed spaces in London are subject to the same sorts of extensive restrictions in how they can be used, often enacted through historic local byelaws limiting behaviours ().

Figure 11. Spaces in the City of Westminster are covered by wide-ranging byelaws established in 1906. As well as everyday measures designed to prevent damage to planting and the fabric of the spaces, control dog mess and allow for the specification of opening times where required, a wide range of other measures are included to restrict the racing or training of dogs, the hanging out of linen to dry, the selling letting or hiring of anything or otherwise soliciting or collecting money, distribution of literature of any kind, delivery of public speeches or sermons, playing music, shooting firearms, flying model aircraft driven by combustible substances, and even restricting people in a “verminous or offensively dirty condition” from lying on or occupying seats.

Managed directly by the Mayor of London, iconic Trafalgar Square has a particularly extensive list of byelaws including on the prohibition of the use of canoes or boats in the fountains, having barbeques in the square, feeding birds (aka the pigeons), use of any sleeping equipment, and, the taking of any photograph without prior written permission “for the purpose of or in connection with a business, trade, profession or employment” (GLA Citation2012) (). Such restrictions have the potential – if enforced (which often they are not) – to profoundly impact on perceptions of what has been called the “publicness” of public space, or how “public” public spaces feel and are. Other spaces have no such restrictions and, as long as you are within the law of the land and not causing a nuisance (which is the key test), you are free to do as you will.

Figure 12. Taken in connection with an academic study, this picture in Trafalgar Square is technically illegal as no prior written permission was applied for or received.

Conceptually, most definitions of the “publicness” of space have an explicit “ownership” dimension (Dovey Citation2016, 155; Varna Citation2014, 53; Leclercq Citation2018) often as a surrogate for control, interleaving with key dimensions of “access” and “use”. Whilst publicness can certainly be impacted by ownership as it can by other contextual factors – regulatory, physical, cultural, etc. – the examples already discussed suggest that degrees of publicness do not ipso facto follow from the ownership status of spaces in the same way that they would from degrees of access and patterns of use.

Recent research with a focus on ten public spaces in a combination of public and private ownerships came to a similar conclusion (Wilson and Moore Citation2020). Conducted by the Greater London Authority (GLA) and utilising a combination of in-depth interviews with public space users, mobile ethnography and a large scale survey of 1,134 Londoners, the work revealed that because of their free access and absence of physical barriers, privately owned and managed spaces are typically viewed by users as open to all and owned and managed by the public sector. Respondents nevertheless reported that some spaces felt more private than others, perceptions associated with the over-use of signage and security guards and sometimes with a particularly corporate feel. 51% of those interviewed either did not mind who owned and managed spaces or felt that there should be a mix of public and private ownerships in the city, 39% felt the public sector should have total responsibility and just 2% that the private sector should take control. Of course the experience of some groups may be very different from the general experience of Londoners, with the young, minority groups and the homeless often cited in the international literature as particularly disadvantaged in their ability to access and use public spaces (Johns Citation2001; Malone Citation2002; Lownsbrough and Beunderman Citation2007; Glyman and Rankin Citation2016; Doherty et al. Citation2008). These groups – if they are not present – may not have been captured in this and other similar research, revealing a key conceptual problem with such surveys.

Given existing patterns of ownership and use, the pragmatic response would be to safeguard publicness, regardless of ownership and to work to avoid the sorts of spaces that should be open, unrestricted and free to use but for various reasons are not. When such spaces are publicly owned and managed it may be possible to blame the over-zealous instincts of regulators for whom restriction may sometimes be the first instinct over freedom (). When they are private, developers and managers of spaces can be blamed, but that culpability must also be shared with the public sector for failing to sufficiently ensure that long-term rights and responsibilities are properly agreed and enshrined in perpetuity at that point when consent for development is given (in London, that is the point at which planning permission is granted). If long-term management arrangements are not agreed at that point, it becomes very difficult (although not impossible) to change such matters retrospectively without unduly impacting on private property rights (Layard Citation2010). In the third part of this paper, an initiative designed to put in place the policy infrastructure to address concerns around the involvement of private interests in the management of public spaces whilst still encouraging the potentially positive impacts that they can have, is now discussed.

Figure 13. The introduction and use of Controlled Drinking Zones in London (as elsewhere) have proven to be controversial and their anticipated benefits largely unconfirmed in the evidence (Pennay and Room Citation2012).

3. Towards a charter

Returning to the international public spaces literature, concerns about restrictions placed on the rights of potential users and on the consequential inclusiveness of spaces are long-standing and widespread, hailing from a broad range of disciplinary perspectives: political science, urban geography, anthropology, sociology and from legal scholars (Biffault Citation1999; Low and Smith Citation2006; Massey and Snyder Citation2012; Mensch Citation2007; Mitchell Citation1995; Sorkin Citation1992; Zukin Citation1991). To overcome such concerns and maximise publicness (access and use), regardless of ownership, it seems reasonable to oppose all needless and petty restrictions on the use of public spaces unless there are very good reasons for their imposition such as the safety of users. This was the conclusion of the London-wide academic study Capital Spaces which argued for the adoption of a “Charter of public space rights and responsibilities” in order to guarantee fundamental rights (Carmona and Wunderlich Citation2012, 285). The research proposed text by way of a “straw man” to encourage debate ().

Box 1. “Straw man” Charter of Public Space Rights and Responsibilities (here showing text as revised in Carmona Citation2019)

More important than the exact wording were the series of principles underpinning the proposal, namely that:

With rights come with responsibilities

Principles should apply regardless of ownership

It is about safeguarding freedoms, not restricting behaviours

A charter should be simple and should not attempt to control more than necessary

Keep it clear.

The idea echoes calls in the USA for more explicit rules concerning the management of public spaces and how they are interpreted. Whilst New York’s, Zoning Resolution, for example, includes a number of provisions specifying types of amenities that POPS must provide, as well as stipulations on the provision of signage and what that can and cannot specify (e.g. it “shall not prohibit behaviors that are consistent with the normal public use of the public plaza such as lingering, eating, drinking of non-alcoholic beverages or gathering in small groups – New York City Planning Department Citation2007), Huang and Franck (Citation2018, 515) call for the provision of “more specific and consistent interpretation of rules of conduct for the private corporations and institutions that own and manage bonus spaces”. They argue, it is not simply about posting rules, but also about being more explicit about how they will be enforced and with what consistency.

Whilst all stakeholders bear responsibility for creating truly public space – open, accessible and inclusive – only public authorities can ultimately enforce publicness as part of the place-shaping process. This can be divided between the meta-phases of “shaping for use” (through design and development) and “shaping through use” (how space is used and managed), and each impacts decisively on how spaces are experienced (Carmona Citation2014). If the potential benefits from the public-isation of space are to be fully captured and shared equitably, then they need to be considered fully during the design/development processes prior to their use and management. As has already been argued, for the public sector there is typically a regulatory gateway (planning, zoning, construction permit, or otherwise) at which point the power of the public sector is maximised. Once this point passes, power typically wanes sharply and the authority to intervene over use and management issues becomes increasingly more difficult to exercise requiring powers of persuasion or otherwise through police powers.

A charter aims to establish expectations early, clearly and publicly before such regulatory consents are given. In London this means incorporation into planning policy. Carmona and Wunderlich (Citation2012, 286) argued it could then apply to all new public spaces “that a reasonable person would regard as public, whether privately or publicly owned. This would cover all spaces that during daylight hours are (usually) open and free to enter”.

3.1. The public London charter

In 2017, reflecting the renewed debate in London stimulated by The Guardian’s analysis, the then new Mayor of London instructed that provisions should be incorporated into the London Plan to address the concerns that had been raised. Following presentation of the “straw man” charter (see ) to the London Plan team, the idea was taken up in the Draft London Plan published in December 2017. In the plan a commitment was given to the creation of a Public London Charter in order to ensure that appropriate management arrangements are adopted for London’s public realm in a manner which can maximise public access and minimise rules governing space (Mayor of London Citation2017: Policy D7).

In the run up to the production of the Charter, analysis on behalf of the GLA of ten public spaces in London (seven privately and three publicly owned) noted the different types of rules that were currently in operation, some explicitly posted online or on-site and others only observed in operation (Bosetti et al. Citation2019, 18). These focused on i) safe management (e.g. restrictions on glass bottles, BBQs and alcohol consumption, although drinking was usually allowed in moderation), ii) restricting activities that might impinge on others’ rights (e.g. rough sleeping, commercial photography, smoking, picnicking for more than 20 people, removing tops, busking, conducting surveys), iii) protecting assets (notably by controlling skateboarding).

In October 2020 a Draft Public London Charter was published for consultation (). It advocated for a “public realm that is open and offers the highest level of public access irrespective of land ownership, with landowners promoting and encouraging public use of public space for all communities” (Mayor of London Citation2020, 3).

Box 2. Draft Public London Charter

The draft charter incorporated the key principles advocated through the straw man charter, notably application regardless of ownership, a welcoming rather than restricting attitude (avoiding petty rules and limiting restrictions “to those essential to the safe management of the space” – Mayor of London Citation2020, 3), and an emphasis on treating all users to the same high standards. It explicitly promoted Sidiq Khan’s wider diversity and inclusion aspirations, and picked up on key issues identified by (Bosetti et al. Citation2019), notably that rules should be clearly visible to users alongside responsibilities for ownership and management; that managers should in some way be trained to ensure they ascribe to the standards in the charter (the researchers suggested a community safety accreditation scheme); and landowners should not harvest data on personal issues without consent (e.g. through face recognition technologies). Less apparent was the notion that with rights come responsibilities and that public spaces users – alongside managers – have responsibilities to ensure the true publicness of public space. Also, rather than an enforceable document, the charter was proposed to have the status of guidance, offering eight generic principles () for public space as – “a benchmark for good practice” (Mayor of London Citation2020, 4) – whilst encouraging London’s 33 Boroughs to incorporate the principles of the charter into their decision-making. This implied being written into legal agreements (in England known as Section 106 agreements) linked to the granting of planning permission for developments.

3.2. Trailing a voluntary charter

Whether adoption of the principles in the Public London Charter will prove effective is likely to depend on whether it is actively promoted by the Mayor, and whether its content gets incorporated into the local plans of London’s 33 Boroughs, and from there into the development management decision-making associated with new or regenerated public spaces. Beyond new projects, there is also the question of whether such a charter could be made to apply retrospectively to existing spaces already in use, perhaps through encouraging or otherwise incentivising public space owners and managers to voluntarily adopt the Charter’s principles. Some clues can be garnered from action research funded by the London Borough of Wandsworth that ran concurrently with the preparation of the Mayor’s charter.

The project sought to test out the feasibility of adopting a voluntary local charter relating to the proposed linear park at London’s Nine Elms. Whilst action research is sometimes criticised for its lack or rigour and replicability – given the closeness of researchers to the subjects of their study and because of the specificity of each case – as a means to get close to decision-makers and understand the complex dynamics involved in policy or practice decision-making, such approaches can be very insightful.

Nine Elms is undergoing a massive regeneration of some 227 hectares (561 acres), including the last remaining industrial zone along the south bank of the Thames in central London and incorporating the massive Battersea Power Station development (https://nineelmslondon.com) (). Threading through the area is to be a new park that passes through five separate private ownerships – R&F Properties; Royal Mail Group; New Covent Garden Market; Battersea Power Station; Ballymore – and links to public space around the new American Embassy. The research involved a workshop to discuss the principles of a charter of Public Space Rights and Responsibilities, followed by an ongoing engagement process to devise and then refine the wording for a tailored charter and to examine possibilities for its adoption.

Figure 14. Public spaces beginning to emerge around Battersea Power Station will eventually link into the linear park.

At the workshop, the starting point for discussion was the text of the straw man charter (see ) which formed the basis for debate around which stakeholders representing each of the private parties and the London Borough of Wandsworth (and separately and later the American Embassy) were engaged in discussion. Each point of the straw man charter was introduced and justified and then subjected to an open discussion. Quickly it became apparent that not only could a charter safeguard public interests, it could also safeguard the interests of the different private parties (and their successors in law) against each other given that the shaping of a successful place was not solely within any one party’s hands, but was dependent on the actions of all in the room working together. Remarkable consensus was therefore quickly built around both the need for a charter and its key principles, with the discussion and agreements recorded and used, by the author, to prepare a new draft of the proposed charter, this time focussed on the specific needs of the Nine Elms Linear Park. Subsequently, through a series of iterations and refinements via email consultation with all parties, a final text was agreed ().

Box 3. Nine Elms linear park charter

Ultimately, all parties have agreed to the approach advocated by the straw man charter based on promoting a culture of openness, equitable access, permissiveness, and shared rights and responsibilities, although the private landowners were also concerned that any activities sanctioned in the park should not impact negatively on local residents (their clients). Whilst – in order to balance these two perspectives – the new charter is more detailed than the original, the result contained very few prohibited activities and many more that were actively encouraged, with some (e.g. trading, busking, events, etc.) coordinated through a mechanism of permissions granted by the proposed park management company on which the Borough will be represented. The presence of the American Embassy on the park and as one of the signatories necessitated a greater awareness of security issues than would normally be the case, but balanced against the permissive ethos of the charter and a recognised need, written into the charter, for ongoing community involvement in the park’s management.

Once agreed, the Borough was particularly concerned with how to give the charter enforceable status whilst avoiding taking on ownership and management responsibilities itself. An accompanying review of options revealed that English councils wishing to exert influence on the long-term management of privately owned and managed spaces can do so in a number of ways: by enacting a local law (option 1 below) by agreement (options 2 and 3) or through changing the status of the land (options 4 to 6):

Creation of local byelaws (as discussed above) – a long and laborious process ultimately requiring parliamentary approval

Landowners goodwill – through a “Gentlemen’s agreement”, but with a non-binding result with no potential for enforcement by the state and that can be withdrawn at any time

By agreement under Section 106 of Town & Country Planning Act 1990 – a planning obligation negotiated as part of the planning consent has the potential to give legal force to the charter if included as part of the agreement

Adoption of the land under Section 38 of Highways Act 1980 – a process that would transfer ownership and management responsibilities to the state, which the Borough (in this case) wished to avoid

Creation of a walkway by agreement under Section 35 of Highway Act 1980 – a process limited to provisions related to identified walkways and so lacking the necessary scope to create an ambitious charter

Establish a rights through a real covenant – which would require separate legal agreements for each ownership and could only be enforced by a landowner of the “benefitting” land.

It was agreed that the charter should be made enforceable in two ways. First, by agreement, between the private interests, each of whom will sign up to implement an agreed Management Plan care of a single jointly owned management company for the whole park (option 2), and second, as part of a Section 106 legal agreement (option 3) between the landowners and the London Borough of Wandsworth. The charter will be posted at entrances to the new park and the Metropolitan Police have agreed to sign up to the principles, thus ensuring that all parties with a management interest are on board.

The agreed approach bears strong resemblance to that now advocated in the Mayor’s proposed Public London Charter and has the potential – if fully applied – to ensure the publicness of the park and the rights of users in perpetuity over this privately owned and managed public space. Although the final impact of the Nine Elms charter will remain unknown until the park is constructed and the charter is operational, the experience of its preparation shows the potential of a voluntary approach as long as i) a proactive local authority is in place to require that a charter is adopted, and ii) the private landowners themselves see the benefits and are willing to engage with the process. Where these conditions are not in place a greater degree of compulsion may very well be necessary. This will of course be difficult if spaces are already built and in operation.

4. Conclusion

Cities are diverse places, diversity is in their nature and is their essence. This paper has shown that, contrary to dogmatic positions that public spaces should always be either publicly or privately owned and managed, morally and pragmatically it matters little who owns and manages them. Instead, what matters is how “public” they are and how freely access and permissive use are guaranteed over time. In other words what are our rights as citizens within spaces, and what are the responsibilities to us of those who own and manage them.

In these debates, use of the term “privatisation of public space” is itself often unhelpful because it assumes that once public spaces are becoming private. This may sometimes be the case, but is often not. In London, for example, analysis of the secondary data discussed in this paper revealed that what is more typical is the opening up through redevelopment of formally private areas of the city to public use as part of large scale redevelopment projects e.g. of former docks, industrial areas, bits of redundant infrastructure and even post-war housing estates. Most of this space never was public in the sense that it was never publicly accessible, so bringing it properly into public use, even if it remains in private ownership, is potentially a very significant public gain. What we have witnessed, at least in London, is the “public-isation” of private space.

At the same time, whilst privately owned and managed spaces remain a legitimate and often valued part of the diverse mix in many cities, it will be important to ensure that urban areas do not become over-dominated by them and that ultimate control of the public realm of our cities is not ceded to private interests (e.g. ). Just as the mix and types of public spaces in our cities needs careful planning (Carmona Citation2019, 47–59), so should the balance of ownerships and responsibilities.

In the post coronavirus world, property investors will have to work even harder to attract clients to their developments and key amongst the amenities on offer will be privately owned and managed public spaces. If these are high quality, accessible and inclusive – as the literature suggests they should be – then cities will be mistaken to pass them up simply for narrowly political reasons. The public-isation of private spaces has much to offer, and with appropriate safeguards in place, perhaps care of a local charter of public space rights and responsibilities, such spaces should be embraced and added to the diverse mix. Ensuring that the right balance is struck is ultimately a critical task of the public sector. It is one that it is often not taken nearly seriously enough.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the London Borough of Wandsworth for funding the preparation of the Nine Elms Park Charter and to Terpsithea Laopoulou for her assistance with the The Guardian data analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Carmona

Matthew Carmona is Professor of Planning and Urban Design at The Bartlett, UCL. He is an architect/planner and researches urban design governance, the design and management of public space, and the value of urban design. He Chairs the Place Alliance and edits www.place-value-wiki.net. His research can be found at https://matthew-carmona.com. @ProfMCarmona.

Notes

1. Strategic level government in London consists of the elected Mayor of London, who has executive powers, and the London Assembly which is elected to hold the Mayor to account and which regularly conducts Inquiries into issues of London-wide policy relevance. Together they constitute the Greater London Authority (GLA).

2. The lower tier of London government is conducted by 33 London Borough. The boroughs determine most applications for planning permission in the city although The Mayor sets strategic planning policy in the London Plan and has the right to determine applications of strategic importance.

References

- Advocates for Privately Owned Public Space (APOPS) & The Municipal Art Society of New York (MASNYC). 2012. “Privately Owned Public Spaces in New York, History.” https://apops.mas.org/about/history/

- Al, S. 2016. Mall City, Hong Kong’s Dreamworlds of Consumption. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Biffault, R. 1999. “A Government for Our Time? Business Improvement Districts and Urban Governance.” Columbia Law Review XCIX (2): 365–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1123583.

- Bishop, P., and L. Williams. 2016. Planning, Politics and City-making, A Case Study of King’s Cross. London: RIBA Press.

- Bosetti, N., R. Brown, E. Belcher, and M. Washington-Ihieme. 2019. Public London: The Regulation, Management and Use of Public Spaces. London: Centre for Cities.

- Brill, M. 1989. “Transformation, Nostalgia, and Illusion in Public Life and Public Space.” In Public Places and Spaces, edited by I. Altman and E. Zube, 7–29. New York: Plenum.

- Carmona, M. 2010a. “Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (1): 123–148. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800903435651.

- Carmona, M. 2010b. “Contemporary Public Space, Part Two: Classification.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (2): 157–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574801003638111.

- Carmona, M. 2014. “The Place-shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process.” Journal of Urban Design 19 (1): 2–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2013.854695.

- Carmona, M. 2015. “Re-theorising Contemporary Public Space: A New Narrative and A New Normative.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 8 (4): 373–405.

- Carmona, M. 2019. “Principles for Public Space Design, Planning to Do Better.” Urban Design International 24 (1): 47–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-018-0070-3.

- Carmona, M., G. Sandkjær Hanssen, B. Lamm, K. Nylund, I.-L. Saglie, and A. Tietjen. 2019. “Public Space in an Age of Austerity.” Urban Design International 24 (4): 271–259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-019-00082-w.

- Carmona, M., and F. Wunderlich. 2012. Capital Spaces, the Multiple Complex Spaces of a Global City. London: Routledge.

- De Magalhaes, C. 2014. “Business Improvement Districts in England and the (Private?) Governance of Urban Spaces.” Environment and Planning. C, Government & Policy 32 (5): 916–993. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/c12263b.

- De Magalhaes, C., and S. Freire Trigo. 2017. “Contracting Out Publicness: The Private Management of the Urban Public Realm and Its Implications.” Progress in Planning 115: 1–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2016.01.001.

- Doherty, J., V. Busch-Geertsema, V. Karpuskiene, J. Korhonen, E. O’Sullivan, I. Sahlin, A. Tosi, A. Petrillo, and J. Wygnańska. 2008. “Homelessness and Exclusion: Regulating Public Space in European Cities.” Surveillance & Society 5 (3): 290–314.

- Dovey, K. 2016. Urban Design Thinking, A Conceptual Toolkit. Bloomsbury: London.

- Ellin, N. 1996. Postmodern Urbanism. Oxford: Blackwells.

- Ellin, N. 1999. Postmodern Urbanism. revised ed. Oxford: Blackwells.

- Frearson, A. 2016. ”Patrick Schumacher Calls for Social Housing and Public Space to Be Scrapped, Dezeen.” November 18. https://www.dezeen.com/2016/11/18/patrik-schumacher-social-housing-public-space-scrapped-london-world-architecture-festival-2016/

- Garrett, B. 2017. “These Squares are Our Squares, Be Angry about the Privatisation of Public Space.” The Guardian, July 25. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jul/25/squares-angry-privatisation-public-space?mc_cid=8237a7a204&mc_eid=aa61c2d78d

- Glyman, A., and S. Rankin. 2016. Blurred Lines: Homelessless and the Increasing Privatization of Public Space. Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=hrap

- Graham, S. 2001. “The Spectre of the Splintering Metropolis.” Cities 18 (6): 365–368. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00028-2.

- Greater London Authority (GLA). 2012. “Trafalgar Square Byelaws 2012.” https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/trafalgar_square_byelaws.pdf

- Hristova, S., and M. Czepczyński. 2018. “Introduction.” In Public Space, between Reimagination and Occupation, edited by S. Hristova and M. Czepczyński. London: Routledge.

- Huang, T. S., and K. Franck. 2018. “Let’s Meet at Citicorp: Can Privately Owned Public Spaces Be Inclusive?” Journal of Urban Design 23 (4): 499–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1429214.

- Johns, R. 2001. “Skateboard City.” Landscape Design 303: 42–44.

- Kayden, J. 2000. Privately Owned Public Space: The New York Experience. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Kayden, J. 2005. “Using and Misusing Law to Design the Public Realm.” In Regulating Place: Standards and the Shaping of Urban America, edited by E. Ben-Joseph and T. Szold. New York: Routledge.

- Klemme, M., J. Pegeles, and E. Schlack Fuhrmann. 2013. “Co-production: Review of Analogous Co-Production of Urban Space in German Cities.” New York and Santiago De Chile, PND Online 8 (1): 1–11.

- Koch, R., and A. Latham. 2013. “On the Hard Work of Domesticating a Public Space.” Urban Studies 50 (1): 6–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012447001.

- Kohn. 2004. Brave New Neighbourhoods, the Privatization of Public Space. New York: Routledge.

- Krieger, A. 1995. “Reinventing Public Space.” Architectural Record 183 (6): 76–77.

- Kutay Karac, E. 2016. “Public Vs. Private: The Evaluation of Different Space Types in Terms of Publicness Dimension.” European Journal of Sustainable Development 5 (3): 51–58.

- Landman, K. 2019. Evolving Public Space in South Africa, Towards Regenerative Space in the Post-Apartheid City. London: Routledge.

- Layard, A. 2010. “Shopping in the Public Realm, A Law of Place.” Journal of Law and Society 37 (3): 412–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2010.00513.x.

- Leclercq, E. 2018. “Privatisation of the Production of Public Space.” PhD Dissertation, Delft, Delft University of Technology.

- Leclercq, E., D. Pojani, and E. Bueren. 2020. “Is Public Space privatization Always Bad for the Public? Mixed Evidence from the United Kingdom.” Cities 100 (May): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102649.

- London Assembly. 2011. Public Life in Private Hands, Managing London’s Public Space. London: Greater London Authority.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., and T. Banerjee. 1998. Urban Design Downtown: Poetics and Politics of Form. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

- Low, S., and N. Smith. 2006. “Introduction: The Imperative of Public Space.” In The Politics of Public Space, edited by S. Low and N. Smith. London: Routledge.

- Lownsbrough, H., and J. Beunderman. 2007. Equally Spaced? Public Space and Interaction between Diverse Communities. London: DEMOS.

- Madden, D. 2010. “Revisiting the End of Public Space, Assembling the Public in an Urban Park.” City & Community 9 (2): 187–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01321.x.

- Malone, K. 2002. “Street Life: Youth, Culture and Competing Uses of Public Space.” Environment and Urbanization 14 (2): 157–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/095624780201400213.

- Massey, J., and B. Snyder. 2012. “Occupying Wall Street: Places and Spaces of Political Action.” Places Journal. September. doi:https://doi.org/10.22269/120917.

- Mayor of London. 2009. London’s Great Outdoors, A Manifesto for Public Space. London: London Development Agency.

- Mayor of London. 2017. The London Plan, the Spatial Strategy for Greater London, Draft for Public Consultation. London: Greater London Authority.

- Mayor of London. 2020. “Public London Charter, Draft London Plan Guidance, London, Greater London Authority.” https://consult.london.gov.uk/public-london-charter

- Mensch, J. 2007. “Public Space.” Continental Philosophy Review 40: 31–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11007-006-9038-x.

- Minton, A. 2009. Ground Control, Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-first Century City. London: Penguin Books.

- Mitchell, D. 1995. “The End of Public Space? People’s Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85: 108–133.

- Nemeth, J., and S. Schmidt. 2011. “The Privatization of Public Space: Modelling and Measuring Publicness.” Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 38: 5–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/b36057.

- New York City Planning Department. 2007. “Zoning Resolution, Article III Commercial District Regulations.” 37-752 Prohibition Signs. Accessed 17 October 2007. https://zr.planning.nyc.gov/article-iii/chapter-7

- Pennay, A., and R. Room. 2012. “Prohibiting Public Drinking in Urban Public Spaces: A Review of the Evidence.” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 19 (2): 91–101.

- Regeneris. 2017. “The Economic and Social Story of King’s Cross, London, Argent LLP.” https://www.argentllp.co.uk/content/The-Economic-and-Social-Story-of-Kings-Cross.pdf

- Renn, A. 2018. “Interview: Architect Patrik Schumacher: ‘I’ve Been Depicted as a Fascist’.” The Guardian, January 17, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/jan/17/architect-patrik-schumacher-depicted-fascist-zaha-hadid

- Rossini, F., and M. Hoi-lam Yiu. 2020. “Public Open Spaces in Private Developments in Hong Kong: New Spaces for Social Activities?” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2020.1793803.

- Schmidt, S., J. Nemeth, and E. Botsford. 2011. “The Evolution of Privately Owned Public Spaces in New York City.” Urban Design International 16 (4): 270–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2011.12.

- Sennett, R. 1977. The Fall of Public Man. London: Faber & Faber.

- Shenker, J. 2017. “Revealed: The Insidious Creep of Pseudo-public Space in London.” The Guardian, July 24. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/jul/24/revealed-pseudo-public-space-pops-london-investigation-map

- Sorkin, M., Ed. 1992. Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. New York: Hill & Wang.

- Urban Design London. 2015. Estate Regeneration Sourcebook. London: UDL.

- van Melik, R., and E. van der Krabben. 2016. “Co-production of Public Space: Policy Translations from New York City to the Netherlands.” Town Planning Review 87 (2): 139–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.12.

- Varna, G. 2014. Measuring Public Space: The Star Model. London: Ashgate.

- Wainwright, O. 2018. “The £3bn Rebirth of King’s Cross: Dictactor Chic and Pie-in-the-sky Penthouses.” The Guardian, February 9, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/feb/09/gasholders-london-kings-cross-rebirth-google-hq

- Walker, B. 2007. “Rows Likely When Public Space Meets Private.” Regeneration and Renewal, 21, June, 22.

- Wang, Y., and J. Chen. 2018. “Does the Rise of Pseudo-Public Spaces Lead to the ‘End of Public Space’ in Large Chinese Cities? Evidence from Shanghai and Chongqing.” Urban Design International 23: 215–235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-018-0064-1.

- Wilson, M., and H. Moore. 2020. Exploring London’s Public Realm. London: Greater London Authority City Intelligence Unit.

- Zukin, S. 1991. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Zukin, S. 2018. “Reimagining Civil Society.” In Public Space, between Reimagination and Occupation, edited by S. Hristova and M. Czepczyński. London: Routledge.

- Websites

- https://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/privately-owned-public-spaces

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_garden_squares_in_London

- https://londongardenstrust.org/conservation/inventory/

- https://nineelmslondon.com