ABSTRACT

Developer-led gentrification, assisted by local governments, is the antithesis of spatial justice. This is particularly true in London where land values are at a premium and both programmes and policies aimed at mitigating the negative impact are superficial and non-effective. In this context, I argue that asserting a form of Latin urbanism in struggles over place becomes a strategic tool for reshaping, claiming, and resisting gentrification in inner city neighbourhoods of London. The paper draws on the conceptual underpinnings of Latino urbanism within the global north to argue that building networks of solidarity and collaboration amongst like-minded groups is crucial to resist gentrification and advocate for spatial justice and inclusive urban policies. By focusing on Latin urbanisms, this paper contributes to our understanding of unequal forms of urbanisms in London, particularly as it is framed around race and ethnicity, and thus addresses the ethnic gap in urban planning policy and development in the UK. The paper provides insightful material from long-term ethnographic research in two of London’s largest Latin American business clusters at Elephant and Castle in the borough of Southwark and Seven Sisters in the borough of Haringey.

Introduction

Developer-led gentrification, assisted by local governments, is the antithesis of spatial justice. This is particularly true in London where land values are at a premium and both programmes and policies aimed at mitigating the negative impact of gentrification are superficial and non-effective. The current paper explores how asserting a form of Latino Urbanism (Rojas Citation1991), becomes a strategic tool for reshaping, claiming, and resisting gentrification in inner city neighbourhoods of London. I argue that protest and participation are embedded in current manifestations of Latin urbanism which emerge as a response to gentrification processes that are impacting on these distinctive Latin neighbourhoods. In London, Latin urbanisms are an act, expression, and manifestation against gentrification.

The production of urban spaces under neoliberal times has seen the role of the state in managing public spaces diminished. The loss of public land to developers and private capital results in a form of private, corporate, and replicable urbanism that erases difference and uniqueness of a place. A place making initiative that is replicated across the globe and promotes, in its path, exclusionary practices through urban design. The shift in urban infrastructure development, including the transfer of public land and assets, from local government authorities to private investment, has provoked further marginalisation of the urban poor and migrant urbanism in core inner city areas.

Developer-led gentrification privilege land as a profitable resource at the expense of migrant and ethnic groups and economies. It disproportionately impacts upon London’s Black Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) and other minoritised groups eradicating or displacing the economic underpinnings that sustain communities, high streets, and local economies. In this context, the overall aim of this paper is to highlight the role of migrant urbanisms for reshaping unequal urban development. As I demonstrate below research acknowledging Latino urbanisms and unequal urban policies are more common in the United States, whereas the debate in the UK, with few exceptions (Hall Citation2015; Almeida Citation2021), steers towards class-based unequal urbanisms. Thus, by focusing on Latin urbanisms, this paper contributes to our understanding of unequal forms of urbanisms in London, particularly as it is framed around race and ethnicity. The paper also contributes to understanding how Latin urbanism in London is structured around anti-gentrification struggles. As I argued elsewhere, this is particularly relevant in global cities like London where current forms of developer-led gentrificationFootnote1 has resulted in the displacement of the urban poor, migrant groups, minority ethnic groups, and migrant and ethnic economies (Román-Velázquez, and Hill Citation2016). Developer-led gentrification is a form of gentrification that leaves “a void in a neighbourhood, in a city, in a culture. In that way gentrification is a trauma, one caused by the influx of massive amounts of capital into a city and the consequent destruction following in its wake” (Moskowitz Citation2017, 5). Gentrification in this context refers to “a system that places the needs of capital (both in terms of city budget and in terms of real estate profits) above the needs of the people” (Moskowitz Citation2017, 9). This process of neo-liberal gentrification is being resisted and grass roots coalitions are emerging to challenge proposed local government plans. In the case of London, these coalitions are broad and include businesses in addition to members of the community and social housing activists. The cases discussed in this paper demonstrate the alliances formed by local groups opposed to housing and retail gentrification.

I argue that developer-led gentrification is supported by local governments who justify dealing with the housing crisis by long-leasing public land to corporate capital and facilitated by local and regional planning policies. It is also sustained by social enterprises who are complicit in the process by landing in local areas with no knowledge of the communities that are negatively impacted by the proposed developments. Policies and programmes of investment to ameliorate and mitigate negative impact of regeneration on local groups act as a public relations veneer that hides the root causes of economic, social and racial inequality in our cities.

A report by the UK’s Town and Country Planning Association (Citation2019) acknowledges that the planning system is not inclusive and “it fails to promote equality between different groups” (4) … and cites lack of trust between communities, planners and the development sector as one of the leading reasons for the lack of participation of local groups in the planning system. Thus, possibilities of participation from local groups are thwarted by a system that does not value the ingrained knowledge and lived experiences of communities who are left behind from this process. As I demonstrate in this paper, having been excluded, these communities resort to protest (a form of protest that asserts cultural symbols and identities) to mobilise claims over their rights to place and mobilise around social and spatial justice.

It is in this context that Latin urbanisms in London become significant for anti-gentrification struggles. Rather than invoking a form of Latin urbanism through the marketization of culture and ethnicity, the current form of migrant urbanism that we witness in London, is a way of asserting culture in the face of past and current struggles over space. I argue that manifestations of Latin urbanisms in London become a tool to resist gentrification. This is already the case in the United States, where some lower income Latino urban areas undergoing regeneration resort to creative forms of local opposition (González Citation2017).

This paper focuses on Latin American business clusters at Elephant and Castle (EC) and Seven Sisters (SS), two deprived areas of London that are undergoing intense programmes of urban redevelopment. These business clusters, key to London’s Latin American and other migrant and ethnic groups, are under threat of displacement due to regeneration projects that enable a process of gentrification. By introducing the two case studies my aim is to trace trajectories of Latin Urbanisms to inform such discussions in the context of developer-led gentrification in global cities.

Methodology: ethnography, reflective practice and lived-experience

The information that follows derives from long term multi-method research practice and knowledge gained from living and researching the communities I am part of and work with. The findings presented here derive, firstly, from my experience as an activist-scholar who is part of the communities affected directly by these developments and a commitment to just development, and, secondly, from formal ethnographic research conducted with these communities – including in depth interviews; informal conversations; a survey and mapping.

What follows contains both, formal research whilst in academia, but also a form of autoethnography while working at and with Latin Elephant.Footnote2 Autoethnography “is both process and product”, it “seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno) … ” and while autoethnography takes different forms, I adopt a certain form that “treats research as a political, socially-just and socially-conscious act … ” (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011, 273). This approach is one that provides me with the opportunity to reflect on my lived experience and work from the perspective of being part of the community I work with and research for.

I have been an active member of the anti-gentrification struggles at Elephant and Castle and Seven Sisters and unavoidably some of the material presented here derives from my direct involvement in these struggles. While the material presented here includes work with Latin Elephant, however, all material used here is publicly available, or draws from my lived experienced in protests. I have not exploited the privilege access of the networks I was part of during my work with Latin Elephant, and do not use material that I gathered from closed knit networks or quotes from meetings where I was not there as an academic researcher. The mixed use of ethnographic research and autoethnography acknowledges that as both an academic and active member of the community I speak, write, and value research for different purposes and as such accommodate subjectivity and emotionality as integral parts of the research process (Ellis, Adams, and Bochner Citation2011). Most of the material presented in this article derives from ethnographic research with Latin Americans in London. This work started in the early 1990s, with another period of participant observation in the summer of 2006 and a yearlong ethnographic research in 2011–12, which included in-depth interviewing, conversations, surveys, mappings, and planning policy analysis. Throughout this period, I conducted over 50 in-depth interviews and many informal conversations with Latin American business owners in Elephant and Castle and Seven Sisters. The research also included a self-produced manual survey and mapping of both business clusters in 2012, with subsequent updates in 2014 and 2016, this material was used to build the business cluster profile for Elephant and Castle and Seven Sisters. During this period and throughout the planning application processes for both sites, I conducted policy analysis of London wide and borough specific planning documents. This involved identifying gaps by cross-referencing with interviews and participation at grassroots groups involved in anti-gentrification struggles in London. The aim was to address the race and ethnic gap in planning policies, particularly so as it was through their implementation that racial undertones were evident. This analysis led to an intervention at the Further Amendments to the London Plan (FALP) in 2015and a subsequent policy change in favour of migrant and ethnic economies in urban developments.Footnote3 I have been following up both case studies and accumulated a wealth of information from government sites, newspapers, developers, and community groups for a long time and more consistently so since 2006. Some of this material informs the trajectory and was used to build the chronology of events leading up to the demolition Elephant and Castle shopping centre and the closure of Seven Sister’s indoor market.

Latin urbanisms under review

This section draws on conceptual underpinnings of Latino urbanismFootnote4 developed in the USA to highlight that building networks of solidarity and collaboration amongst like-minded groups is crucial to resist gentrification and advocate for spatial justice and inclusive urban policies. In London, Latin urbanisms manifest through protest and participation in the planning system and as such an act, expression, and manifestation against gentrification.

In the United States, Latino urbanism refers to the process whereby the appropriation and revitalisation of urban spaces by Latinas/os is rooted in the history of migration, marginalisation and responds to their needs and cultural preferences. Subsequently, Latino urbanism developed as both a practical planning design tool for community-led development that addressed Latina/o lifestyles and a theoretical approach to explain transformations in the nature and function of cities with large Latina/o populations (Diaz and Torres Citation2012; Lara Citation2015; Rojas Citation1991). An overview of the literature about Latino urbanism in the USA suggests that the concept of Latino urbanism captures community practice, urban design techniques and theoretical approaches. However, it is important to acknowledge that in this context Latino urbanisms emerged “as rational, context-specific, culturally informed, creative responses to a wide range of structural conditions that have and continue to challenge, oppress, and marginalize Latino communities in the United States” (Garfinkel-Castro Citation2021, 2). I argue that in the UK Latin urbanisms is rooted in struggles against gentrification and to resist displacement. It is characterised by networks of solidarity with like-minded groups in anti-gentrification struggles, whereby Latin urbanisms is invoked to assert their right to the city and culture, rather than as a theoretical approach or an urban design opportunity. Although urban design opportunities have emerged in the two cases discussed here,Footnote5 as in the USA (Londoño Citation2010), these emerged and developed as a response to the threat posed by gentrification.

Revitalisation plans for an area can re-create places in ways in which it alienates local communities. These communities, often from a lower income and of migrant and ethnic backgrounds, are often excluded by the planning process that supports investment and development in deprived inner-city areas. Alternative community-led initiatives emerge in this context to address the aspirations and needs of local populations. The community-led initiatives develop as a response to, and are often in sharp contrast to, private-public sector led consultations that tend to address the aspirations and needs of a professional and highly skilled population. This process subsequently leads to gentrification whereby distinctive forms of cultural and migrant urbanisms are erased, celebrated, or neutralized for marketing purposes (Londoño Citation2010). This context leads to different manifestations of urban culture, one that purposefully relies on visual narratives and practices of spatial resistance, and another which act as an affirmative and gentrified representation of urban culture (Londoño Citation2010).

The development of urban areas into distinct Latin neighbourhoods and the enactment of particular identities in public and private spaces as described by Rojas (Citation1991) in the residential and commercial streets of downtown Los Angeles became a tool to contest plans devised by municipal authorities. The city vision developed by municipal authorities in conjunction with private developers excluded the aspirations and expressions of distinct cultural urban environments deployed by the existing Latino community.

Local residents and grassroots organisations in Los Angeles have for years contested local authorities and private developers in their quest to save distinct Latino neighbourhoods (for example, Save Boyle Heights campaign; and Downtown Santa Ana Development). It is in this context that Latino urbanisms emerged as both a tool to contest plans devised by local authorities and developers and as a form of resistance to gentrification of poor Latino neighbourhoods in Los Angeles, USA (Rojas Citation1991; González Citation2017; González et al. Citation2012). In the United States, lower income Latino urban areas undergoing regeneration are met with fierce and creative forms of local opposition (González Citation2017). Resistance to the gentrification of these neighbourhoods have manifested in different expressions of Latino urbanism.

Latino urbanism emerged as a design tool to resist regeneration and the subsequent gentrification of distinct Latino neighbourhoods. As González (Citation2017) research demonstrates urban planning (as in the case of Santa Ana, California) shifted from a perspective that completely erased and minimised the distinctive cultural working-class character of Mexican neighbourhoods in the 1960s, to one which embraced Mexican culture as an urban design concept. This approach, however, erased the local Mexican community from its vision in the 1980s, to one that recognised an economically differentiated Latina/o population with diverse consumer needs and redevelopment aspirations to those of the poor working-class immigrant Latinas/os. The shift to a differentiated approach to Latina/o population in urban planning in Los Angeles is triggered by a process whereby reduction in public funding has resulted in the partnering of local governments and private developers, subsequently leading to community consultations led by the private sector and therefore neglecting the needs and aspirations of the urban poor and working-class migrant communities.

As a theoretical approach, Latino urbanism tries to explain the existing economic and ethnic gap in urban planning studies in the United States. It brought to the forefront those excluded from urban planning policy and development – the urban working class and the immigrant (Irazábal and Farhat Citation2008). Most recently, the concept tries to capture past and current economic and demographic changes in Latino neighbourhoods. Discussions around Latino urbanisms address economic and demographic shifts amongst the Latina/o populations in the United States.

Latino urbanism as a theoretical approach tries to understand the underlying racial, ethnic, generational, and economic dimensions to urban redevelopment in inner city areas that have been for long home to Latina/o populations. In this sense, it aligns with calls for a diverse approach to architecture and urban design (Day Citation2003). In practice, however, it involves attracting middle-income professionals to stigmatized, marginalised poor communities (Day Citation2003; Lara Citation2015).

Invoking a form of Latino urbanism is fraught with tension and conflict due to the underlying differences emerging from changing demographics and aspirations of the Latina/o population, and because it runs the risk of promoting a particular type of Latino urbanism when such a definition is difficult to pose. Understanding the connection between Latin culture and urban form as proposed by Latino urbanism bares the question as to what constitutes Latina/o preferences when there is no pan-ethnic Latin identity (Talen Citation2012). Whilst asserting a form of Latino urbanism help Latino communities gain legitimacy and political voice, Talen (Citation2012) argues that designing for a particular group might also weaken wider collective goals (Talen Citation2012).

Latin American migration to the UK, and London in particular, is relatively new and not as established as other migrant groups as in the USA where Latin American migration has a long history. In the specific case of London, Latin urbanism does not yet captures urban design techniques. What we witness in London is a type of responsive urbanism rooted in community practices that invoke the right to the city and cultureFootnote6 – a form of urbanism that responds to localised struggles against gentrification.

I argue that current practices of Latin urbanisms in London are reshaping unequal urban development through protest and participation, whilst also acknowledging the risks associated with invoking a racialized and cultural urban form and practice in struggles against gentrification and displacement. Current manifestations of Latin urbanism emerge as a response to gentrification processes that are impacting on these distinctive Latin neighbourhoods. As such, Latin urbanisms are an act, expression, and manifestation against gentrification. Under the context of gentrification migrant and ethnic urbanisms, and in this instance manifestations of Latin urbanisms, are a tool to resist gentrification and claim spatial justice.

The following section provides a profile of both business clusters and focuses on how Latin Americans and other migrant and ethnic groups form alliances and invoke a form or Latin urbanism in anti-gentrification struggles to assert their right to the city and culture.

London’s Latin barrios: resisting gentrification

Early manifestations of Latin urbanism in London could be seen as material practices for reshaping London’s urban landscape, whilst current manifestations act as a form of resistance and a tool for opposing gentrification. Román-Velázquez (Citation1996, Citation1999, Citation2009) identified two key moments in the trajectory of Latin Urbanisms in London. The first instance, which can be traced back to the early 1990s and registered as the making of Latin London (Román-Velázquez Citation1999), captured the early stages of a particular form of Latin urbanism that relied on practices, visual representations, and narratives based on national symbols, colours, sounds, and smells. By the late 1990s, a second wave of Latin urbanisms became evident, one that asserted a British Latinx identity (Román-Velázquez Citation2009, Citation2014; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020). This second moment captured a transition and an attempt to assert fluid, yet rooted, identity practices and narratives – ones that fluctuated between the desire to connect with country of origin and addressing the needs of a growing local population. The third and current moment, and focus of this article, emerges as a response to intense regeneration processes that are affecting distinctive Latin neighbourhoods in London and whereby identity markers such as music, food, and colours are used as a form of resistance. The current moment sees a community that has made London its home and claims its right to the city by asserting ethnic cultural forms and practices embedded in manifestations of Latin urbanisms.

The Latin American population in London is estimated at 145,000, representing 58% of the total Latin American population in the United Kingdom, which has been registered as 250,000. Latin Americans are the eighth largest non-UK born population in London and are the second fastest growing migrant population from outside the EU (McIlwaine and Bunge Citation2016). These migration patterns are linked to the development of particular manifestations of Latin urbanisms in London particularly in the form of clustered commercial spaces in shopping centres, markets, and shopping parades.

Elephant and Castle in the borough of Southwark is home to the largest Latin American business cluster in London, followed by Seven Sisters and Brent. These three areas are at the centre of ambitious programmes of urban regeneration (Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016). The predominantly Latin American business clusters share the space with other migrant and ethnic businesses. London’s Latin locations contribute to the diversity of multicultural neighbourhoods in the capital and are very much engrained in London’s urban fabric. The largest Latin American business clusters in London are now under threat due to a process of retail gentrification that sees traditional markets such as that of Seven Sisters’ Pueblito Paisa and the Elephant and Castle shopping centre traders fighting for their right to remain in place and become sustainable business clusters on the long term (Gonzalez and Dawson Citation2015; Román-Velázquez Citation2014; Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016; King et.al. Citation2018; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020).

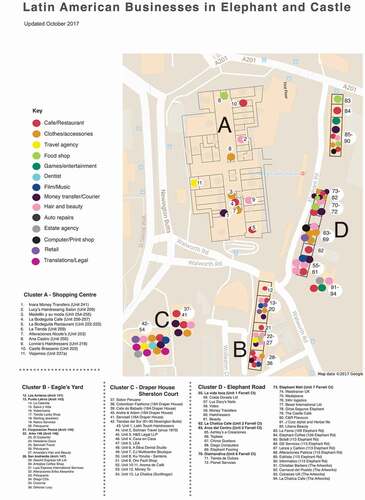

Southwark is the second borough with the highest number of Latin Americans in the capital, representing 8.9% of the total population, surpassed by the borough of Lambeth (McIlwaine and Bunge Citation2016). Latin American retailers started setting up businesses in the EC at the beginning of the 1990s and over the years have transformed the area and in the process contributed to a distinctive Latin Quarter (Román-Velázquez Citation1999; Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016). The Latin American presence in EC core area consisted of four zones: EC shopping centre (demolished in 2021),Footnote7 the Arches in Elephant Road, the Arches in Maldonado Walk (inaugurated on 10th Feb 2018, previously known as Eagle’s Yard) and Tiendas del Sur in Newington Butts. By 2016, there were 96 shops in the immediate area around the underground station and shopping centre, and if taking into account the shops in Old Kent Road (extending from the southern roundabout) the number increased to 110 shops (Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016, Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020). Latin American retailers in EC are mainly from Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia.

The redevelopment plans for EC, which can be traced back to 1999, has been received with scepticism by Latin American local retailers who despite welcoming some of the changes, fear for their sustainability and future presence in the area.

The presence of Latin American shops in Seven Sisters Market, also known as Pueblito Paisa, dates to the beginning of 2000s and have also contributed to the development of a distinctive Latin place in London. The battle to save Pueblito Paisa against private developers and the council dates to 2003 and despite lengthy legal challenges their future is also at risk, particularly so given that the market has not re-opened since it closed in March 2020 due to the current pandemic. Seven Sisters, with Pueblito Paisa and Tiendas del Norte, holds the second largest concentration of Latin American businesses. As its name suggests the traders are mostly Colombian, but there are also traders from Peru and Cuba. Wards Corner – the building that houses Pueblito Paisa – is also home to retailers of African, Afro-Caribbean and Indian descent. The Wards Corner building in Seven Sisters accounts for 39 shops of which 23 are owned or leased by Latin American traders. The majority of the floor space was occupied by Latin American shops. Along the high street another set of shops or small commercial centres contribute to the make-up of the area as a distinctively migrant and ethnic business cluster (Román-Velázquez Citation2014; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020).

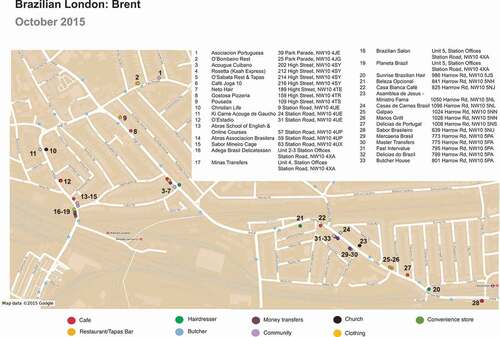

The majority of Brazilian owned businesses are to be found in North West London, Central London and recently more are setting up in South London. It is also in these areas where the largest population of Brazilians can be found (Evans et al. Citation2007; Sheringham Citation2010). Despite the difficulty of establishing the precise numbers of Brazilians in London, the latest estimates reveal that in 2008 there were around 56,000 Brazilian born people in the UK (Kubal, Bakewell, and De Haas Citation2011). A survey conducted by the Brazilian Migration to the UK Research Group (GEB) suggests that the population is dispersed across London, though the largest concentration can be found in the borough of Brent; in Bayswater in central London and in Stockwell in south London (Evans et al. Citation2007). A business survey of Brazilian owned shops in London conducted by the author in 2015 using a variety of online business directories and local Brazilian magazines displayed similar trends to the population survey, confirming that Brazilian shops are dispersed across London, though the largest concentration of Brazilian owned shops and businesses appear to be in and around Willesden and Harlesden in the Borough of Brent, also in Bayswater and Stockwell. The manual survey of Willesden and Harlesden found a total of 34 Brazilian owned shops in an area densely shared with other migrant and ethnic businesses. This area is undergoing an intense regeneration programme under the Old Oak and Park Royal development, which is similar in size and scale to that to the Olympic Park in East London. This is another area of London where migrant and ethnic economies are under threat of displacement.

The growth of Latin American retailers in these locations has led to the development of distinctive Latin areas in London. However, regeneration and ways of re-positioning against the imperatives of global capitalism could lead to a new form of Latin urbanism that exploits culture and difference to fulfil market demands. Thus, we could end up with a Latin Quarter, Latin Village or Brazilian Quarter without any Latin Americans in sight.

Trajectories of Latin Urbanisms and how these are embedded in struggles against gentrification are best exemplified at London’s Latin Quarter in EC and Pueblito Paisa (indoor market) in Seven Sisters.

“We are here to stay” – resisting gentrification at Elephant and Castle and Seven Sisters

Latin American retailers in EC and Pueblito Paisa in Seven Sisters are no longer dependent upon Latin American clientele for their existence and claims to identity. These Latin business clusters are supported by wider community networks that place a value on the multicultural character of these neighbourhoods and draw upon the strength of local retailers to make a point about the impact of regeneration for small local migrant business communities.

The battle to save London’s Latin Quarter at Elephant and Castle can be traced back to the late 1990s when the first attempts at drafting regeneration plans for the Elephant and Castle shopping centre were drawn by Southwark Council. St Modwen was the private developer initially in charge of fulfilling the redevelopment of the shopping centre, though in 2014 the centre was sold to Delancey who is leading the plans to redevelop the shopping centre area into a new town centreFootnote8 (Román-Velázquez Citation2014; Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016; Citation2018; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020).

Elephant and Castle Timeline:

1999 – Southwark Council call to developers for regeneration proposals for EC

2004 – EC Dev Framework & SPG – First announcement of demolition

2010 – Due date for demolition

2014 – Due date for demolition

2013 – EC shopping centre sold to developers Delancey & APG (29th Nov)

2014 – Consultation for EC Town Centre begins

2016 – Planning Application submitted – December (ref: 16/AP/4458)

2018 – EC application rejected (18th January)

2018 – EC application deferred (30th January)

2018 – EC application approved by Southwark Council (3rd July)

2018 – EC application approved by Mayor of London (10th Dec)

2018 – Temporary relocation site deferred to clarify rent levels (12th Dec)

2019 - Temporary relocation site is approved (7th Jan)

2018 – Set up of Traders Panel (November)

2019 – S106 agreement signed and application fully approved (Jan)

2019 – Judicial Review (JR) to overturn planning decision (22nd-23rd October)

2019 – JR decision made. Campaigners lost the JR (20th December)

2020 – Decision to appeal JR outcome by Up the Elephant (7th January)

2020 – Notification of Shopping Centre closure for July 2020 (January)

2020 – CPO powers approved by Southwark Council (7th April)

2020 – 24 September EC shopping centre closed, relocation of majority of traders

2021 – JR appeal not up-held

2021 - Demolition of EC shopping centre begins

The legal battle to save Seven Sisters’ Latin Village (or Pueblito Paisa as it is commonly known) can be traced back to 2003, when Haringey Council announced their plans to redeveloped Wards Corner and chose private developer Grainger to fulfil such plans (Román-Velázquez Citation2014; Román-Velázquez and Retis Citation2020). The timeline of events included here captures stages, gains, losses and length of resistance and activism in both sites.

Pueblito Paisa and Wards Corner Building Timeline

2003 – Haringey Council announced plans to redevelop Wards Corner Bldg. 2003 – Haringey Council chose private developer, Grainger

2007 – Plans for the area presented to the public for the first time

2007 – Wards Corner Coalition (WCC) formed

2008 – Support from Boris Johnson

2008 – West Green Rd/Seven Sisters Dev Trust

2010 – WCC wins legal battle – Equalities Statement

2014 – Community Plan is granted planning application

2016 – Latin Corner UK – Campaign

2016 – CPO issued to traders

2017 – Public Inquiry (11th-17th July)

2019 – CPO result against traders (23rd January)

2019 – Culmination of Haringey Council’s Scrutiny Review (March)

2020 – The indoor market closed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and was not allowed to re-open on health and safety grounds.

Elephant and Castle’s planning application was submitted by developers Delancey in December 2016. The visions emerging from the consultation with traders were ignored and the application was not policy-compliant. Opposition to the plans were soon made. Leading the opposition were 35% campaign on housing matters, and Latin Elephant on migrant and ethnic businesses and equality issues.Footnote9 The objection was led by the Charity Latin Elephant and the 35% campaign group as early as January 2017. Community groups and those opposing to the development demanded for the planning application to be policy-compliant since it did not fulfil the basic 35% social housing policy and the 10% affordable retail space. These were requirements incorporated in the local planning policy for all new developments. Latin Elephant also opposed on equality grounds and in particular for the cumulative negative impact that the development would have for Latin Americans and other BAME people who were business owners, users and customers of the shopping centre. The Equalities Impact Assessment report stated that the development would have a negative impact upon Latin Americans and other BAME groups. At the time I argued that the measures to mitigate negative impact were not sufficient to ameliorate loss of cultural and economic spaces that supported BAME communities in EC and from across London. These demands were adopted by a concerted campaign, under the name Up the Elephant, led by a coalition of local groups, organisations, councilors and individuals whose objectives are to strive for a development that brings benefits to local residents, consumers and users of the Elephant and Castle shopping centre, most of which are of BAME background and older population.

BAME, other minoritized and economically disadvantaged groups who felt alienated by the consultation process and the proposal of a development that did not take into account their needs and aspirations to remain in Elephant and Castle participated in many of the protests and activities organised by Up the Elephant campaign. Up the Elephant is a coalition of grassroots groups and organisations working towards a better deal for the communities of Elephant and Castle. The campaign brought together the demands of local residents and traders in a concerted effort to resist gentrification. Members of the Up the Elephant campaign recognized and valued the contribution that Latin Americans made to Elephant and Castle and acknowledge that traders were crucial for the campaign. Identity markers were used strategically as part of a wider campaign that recognised the diversity of interests embraced within a multi-cultural context.

On the day when the Elephant and Castle planning application was heard, protesters marched along the one and a half mile walk from Elephant and Castle up to Southwark Council’s offices chanting “Delancey to the bin” and holding placards with messages such as “we are here to stay” “We love the Elephant”, “homes for people not for profit”, “protect our barrios”, “stop the displacement of migrant and ethnic traders”. Protesters of Elephant and Castle’s redevelopment joined the symbolic salsa dance lesson and the anti-gentrification bingo game. The protestors used markers of Elephant and Castle’s identity as a tool to resist gentrification. Sadly and as I write this paper the Elephant and Castle shopping centre finally closed its doors for the last time on 24 September 2020 and demolition was completed in 2021. Around half the BAME traders have relocated within the vicinity, but approximately 40 traders according to charity Latin Elephant were left without a relocation site at the time of writing this article.

In September 2016, traders of the indoor market at Seven Sisters were issued with compulsory purchase orders (CPO). This was the last resort to remove traders from the site and give way to the redevelopment. Traders from the indoor market, local activist groups and sympathisers, joined forces and soon after launched the Save Latin Village campaign. The battle to save Pueblito Paisa, or, in English, Latin Village, poured onto the streets of Seven Sisters in a concerted campaign to raise funds to support the legal challenge against the CPO. Various local groups united for the first (8 April 2017) of many salsa/samba shutdowns which saw different generations dance to the tunes of salsa and drumbeats of samba, whilst savouring empanadas and asados, and chanting “Gentrification, no gracias”. Under the colourful banner “protect our barrios” a group of young Latinx claimed to “use empanadas and music as a form of resistance to fight gentrification”.Footnote10 A colourful anti-gentrification piñata for children to bash in return for some sweets was a strong symbolic gesture that captured the sentiment around anti-gentrification struggles in London. The campaign continued with a series of events throughout 2017 and a joined-up approach with local groups and supporters, including a public presence at the CPO hearings and a statement from the United Nations declaring the negative impact that closure of the market will have for the Latin American community.Footnote11 The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated the conditions of Latin American and other BAME traders at Wards Corner Building as the premises were not opened by the managers. The demands for social, cultural and spatial justice continue at this site with further protests organised during July 2020. This campaign is a clear example of how local Latin groups embraced cultural forms as a way of resisting gentrification, asserting identity, and claiming their sense of belonging and their rightful place in the city. Another way of saying “we are here to stay”. This was another strategy in the long struggle to save London’s Pueblito Paisa, or, Latin Village as it was reclaimed by the new campaign group in their aspiration to connect with wider audiences.

The cultural markers of Elephant and Castle – home to London’s largest Latin American business cluster and a bingo hall and bowling alley that catered for disadvantaged, older and young BAME groups in the area – were taken out onto the streets of Southwark to claim for a development that brings benefits to the diverse population of Elephant and Castle. This is a clear example of how cultural practices not only shape a neighbourhood’s identity, but how they are used as a tool to resist gentrification. However, it is important to highlight here that this was a multi-faceted campaign strategy in which all local groups shared knowledge, skills and strengths. Campaigners, supported by the planning officer’s report, argued that the development will have a disproportionately negative impact for migrant and ethnic groups and for Latin Americans in particular. This campaign is a clear example of how equalities matters were taken onto the streets in a symbolic performance that translated into a statement for equality, fairness and anti-gentrification.

The manifestations of Latin Urbanisms in Pueblito Paisa are very much defined by a lengthy legal battle to remain in the space. The campaign to save Pueblito Paisa is significant because despite the internal conflicts that might arise amongst retailers it reinforced a strong sense of self definition and heightened their determination to claim their rights to stay in place. The sense of belongingness and the rights to set roots in place have been challenged by the threats to vacate the building at various stages throughout the planning process.

These circumstances and the lengthy process are important for understanding expressions of Latin urbanism beyond its representational value. Attempts of self-definition in the case of Pueblito Paisa transcend the symbolic, the identity of the place is defined through its activism, wider community networks and self determination to remain in place. This is not just a battle to save Pueblito Paisa, but a local heritage cultural site in Seven Sisters that is supported by wider community networks.

Small local retailers play a greater social role amongst different communities in London and are engrained on the everyday lives of many in the city. The attempts to save both business communities and their incorporation to wider local community groups (Up the Elephant in the case of EC and Wards Corner Coalition in the case of Seven Sisters) attest to the importance placed on businesses as community assets and emotional investments by local groups.

Throughout this section I demonstrated how Latin urbanisms become another layer in the making of Latin London, one which is rooted in activism and resistance. The current instance of Latin urbanism is very much present, visible, and audible in London’s urban fabric through imaginative protests in which cultural symbols (such as music, food, and dance) are celebrated and invoked as a form of resistance. In this sense, cultural symbols are “a significant statement of assertion, validation and pride in cultural production that is. actively present and not ready to go” (Dávila Citation2004, 95).

The link between urban form and cultural practice is activated in urban protest in some of London’s poorer inner-city streets. The combination of elements contributes to practices and manifestations of migrant urbanisms. In this instance Latin urbanism manifests as an urban proposal that is very different to the normative developer-led gentrification that is putting at risk the livelihoods of many residents, traders, families and workers. Urban development and the imperatives of the global city are putting small migrant and ethnic retail as well as public housing communities at risk, it is under this backdrop that Latin Americans are feeling the brunt of gentrification more than ever.

Conclusion: Latin urbanisms in the global city

Throughout this paper I argued that current discourses and practices of Latin urbanism are embedded in anti-gentrification struggles and underpin any sense of belongingness and rights to the city. At a theoretical level this paper addresses the ethnic gap in urban planning policy in the UK and makes an important contribution to understanding the role of migrant urbanisms for reshaping unequal urban development.

This paper questioned neo-liberal attempts to erase race, ethnicity and the urban poor from social inequalities embedded in developer-led gentrification processes that are supported by planning policies (Dávila Citation2004). Thus, “in failing to consider the urban poor in visions of a prosperous urban future, regeneration by dispossetion ultimately advances limited prospects for cosmopolitan belonging” (Hall Citation2014, 1). The two case studies introduced here contribute to our understanding of unequal urban development through the lens of migrant urbanisms (Hall Citation2015) and its subsequent significance for urban studies, urban planning and more generally for understanding the politics of gentrification. In the context of developer and state-led regeneration ethnic based claims over place, as argued by Dávila (Citation2004), are politically important particularly so in a context where contemporary urban policies respond to the marketisation of culture.

I argued that in the case of London, Latin urbanism is a response to localised struggles against gentrification. London as other global cities is in the grip of intense regeneration programmes which erase difference and uniqueness of a place leaving a form of private, corporate, and replicable urbanism. This corporate urbanism washes away all traces of Latin urbanism and privileges efficiency of resources. It is this corporate urbanism and its marketization of culture and ethnicity that is being resisted in EC and SS. The campaign against redevelopment in these locations has brought together coalition of actors and utilised a range of protest styles. The redevelopment plans for both areas have made other community networks value the distinctively Latin places in their doorstep. This has resulted in the formation of wider alliances as a strategy to win greater power for the groups directly affected by regeneration. The claims to spatial justice and to remain in place is embraced not just by Latin American retailers, but by local community organisation alike. It has also made these business communities more visible to the local authorities who would otherwise remain unaware of the role of businesses in the social cement of local groups.

Two Latin American and migrant and ethnic business clusters and community assets, EC shopping centre and Seven Sisters market have been lost to developer-led regeneration. The Seven Sisters indoor market closed in March 2020 because of the pandemic and the landlords have to this date (May 2022) not re-opened the site, leaving many micro-traders all of migrant and ethnic background destitute. Whilst the Elephant and Castle shopping centre closed on 24 September 2020, leaving approximately 40 traders without a relocation site.Footnote12

The current form of Latin urbanisms is being asserted at a time of intense urban regeneration across London, but also in a context of greater economic uncertainty triggered by Brexit, an increasingly hostile environment towards migrants and Covid-19. The pandemic has exacerbated existing conditions of inequality for migrant and ethnic traders. Prior to the current crisis, traders at Elephant and Castle were already in distress and under pressure due to the imminent demolition of the shopping centre in July 2020 (the date was postponed to 24 September 2020 due to Covid-19 pandemic and demolition was completed in 2021); whilst traders at Seven Sisters Market were facing eviction due to Compulsory Purchase Orders (CPO). This is also compounded by the complex negotiations and iterations that occur with other groups who are equally placed in the production of migrant urbanisms. It is in this context that the current forms and manifestations of Latin urbanisms are invoked by different groups to resist gentrification and claim spatial justice.

This is a highly complex environment in which to be asserting such an identity politics, as one must take into account not just the economic and political context under which such claims to the global city are occurring, but also, the mechanisms by which different communities embrace, negotiate or reject such claims of belongingness and right to the city, or such forms of migrant urbanisms. The challenge is how can we best achieve the aspirations of migrant and ethnic traders without the danger of promoting a place-based identity that relies on stereotypes and the commodification of culture, and without neglecting the existing diversity of these areas as distinctive multi-ethnic centres?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. This form of gentrification differs from that introduced by Ruth Glass in 1964 which refers to the process whereby middle classes move to previously working class quarters of London where desirable properties are upgraded and the working class occupiers are displaced. The current form of gentrification alluded to in this paper refers to the forced appropriation of valuable land aided by neo-liberal urban planning policies.

2. Latin Elephant is a charity (founded by the author) working with migrant and ethnic groups and in particular BAME traders, to increase participation, engagement and inclusion in process of urban change in London.

3. The work with Latin Elephant and Just Space was crucial for this change. Just Space is a network of grassroots groups working to increase participation in the planning process, particularly in relation to the London Plan.

4. In the United States most authors use the concept of Latino urbanism, rather than Latin urbanism. In the UK context, the term ‘Latino’ is highly contested by community groups and organisations who prefer to use Latin, Latin American and or Latinx as it is perceived to be more inclusive than that of Latino. In this article the concept of Latino urbanism is used when referring to the USA context, and Latin in the UK context.

5. For Elephant and Castle see London’s Latin Quarter (Román-Velázquez and Hill Citation2016) and Latin Elephant; For Seven Sisters see Wards Corner Community Plan .

6. Lefebvre (Citation1996) conceives the ‘right to the city’ as an emerging right to urban life that is oriented towards social needs and rights to inhabit based on social practices like the right to work, to training and education, health, housing, and leisure. It is the right to a renewed urban society where places are moments in the intersection of social relations, and as such disengaged from exchange value.

7. Traders displaced by the demolition of the shopping centre in 2021 have been relocated to Elephant Arcade, Castle Square, Ash Avenue and Sayer Street.

8. Elephant and Castle Town Centre and LCC Campus Planning Application to Southwark Council (ref: 16/AP/4458) in December 2016.

9. First objection submitted by Latin Elephant on February 2017 available at: https://latinelephant.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/LE-Objection-to-Planning-Application-16_AP_4458.pdf

10. London Latinx, Facebook page post 2017.

11. OHCHR, 27 July 2017. London market closure plan threatens “dynamic cultural centre”https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2017/07/london-market-closure-plan-threatens-dynamic-cultural-centre-un-rights Accessed 14 January 2020.

12. The charity Latin Elephant secured new relocation sites and nearly 60% of traders have to date been relocated.

References

- Almeida, A. 2021. Pushed to the Margins. A Quantitative Analysis of Gentrification in London in the 2010s. London: Runnymede and Centre for Labour and Social Studies. http://classonline.org.uk/docs/Pushed_to_the_Margins_Gentrification_report_v5.pdf.

- Dávila, A. 2004. Barrio Dreams. Puerto Ricans, Latinos and the Neo-Liberal City. Berkeley: U of California Press.

- Day, K. 2003. “New Urbanism and the Challenges of Designing for Diversity.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 23 (1): 83–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X03255424.

- D. R. Diaz and R. D. Torres, eds. 2012. Latino Urbanism. the Politics of Planning, Policy and Redevelopment. New York: NYU Press.

- Ellis, C., T. E. Adams, and A. P. Bochner. 2011. “Autoethnography: An Overview.” Historical Social Research 36 (4): 273–290.

- Evans, Y., J. Wills, K. Datta, J. Herbert, C. McIlwaine, J. May, and P. França. 2007. Brazilians in London: A Report for the Strangers into Citizens Campaign Brazilians in London. London: Department of Geography, Queen Mary, United Kingdom of London.

- Garfinkel-Castro, A. 2021. “Unpacking Latino Urbanisms: A Four-Part Thematic Framework Around Culturally Relevant Responses to Structural Forces.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2021.1953111.

- Gonzalez, S., and G. Dawson. 2015. Traditional Markets Under Threat: Why It’s Happening and What Can Traders and Customers Do. doi:https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2614.0888.

- González, E. R., C. S. Sarmiento, A. S. Urzua, and S. C. Luévano. 2012. “The Grassroots and New Urbanism: A Case from a Southern California Latino Community.” Journal of Urbanism 5 (2–3): 219–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2012.693125.

- González, E. R. 2017. Latino City. Urban Planning, Politics, and the Grassroots. 1st ed. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743806.

- Hall, S. M. 2014. “Emotion, Location and Urban Regeneration: The Resonance of Marginalised Cosmopolitanisms.” In Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location, edited by H. James and E. Jackson, 31–43. London: Routledge.

- Hall, S. M. 2015. “Migrant Urbanisms: Ordinary Cities and Everyday Resistance.” Sociology 49 (5): 853–869. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515586680.

- Irazábal, C., and R. Farhat. 2008. “Latino Communities in the United States: Place-Making in the Pre-World War II, Post-War, and Contemporary City.” Journal of Planning Literature 22 (3): 207–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412207310146.

- King, J., S. Hall,P. Román-Velázquez,A. Fernandez,J. Mallings,S. Peluffo-Soneyra, andN. Perez. 2018. Socio-economic value at the Elephant & Castle. London: London School of Economic and Latin Elephant. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/165924531/2018_Socio_economic_value_at_the_Elephant.pdf.

- Kubal, A., O. Bakewell, and H. De Haas. 2011. The Evolution of Brazilian Migration to the UK Scoping Study Report. Oxford: International Migration Institute, University of Oxford.

- Lara, J. L. 2015. “Latino Urbanism.” In Oxford Bibliographies Online. Oxford: Oxford UP. Accessed May 9, 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780199913701-0099.

- Lefebvre, H. (1996). Writings on Cities (E. Kofman & E. Lebas, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Londoño, J. 2010. “Latino Design in an Age of Neoliberal Multiculturalism: Contemporary Changes in Latin/o American Urban Cultural Representation.” Identities 17 (5): 487–509. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2010.526884.

- McIlwaine, C, and D Bunge. 2016. Towards Visibility: The Latin American Community in London. London: Queen Mary University and Trust for London. https://trustforlondon.fra1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/media/documents/Towards-Visibility-full-report_QqkSbgl.pdf.

- Moskowitz, P. 2017. How to Kill a City. NY: Nation Books.

- Rojas, J. 1991. “The Enacted Environment. The Creation of Place by Mexicans and Mexican Americans in East Los Angeles.” MA Thesis, University of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Román-Velázquez, P. 1996. The construction and communication of Latin identities and salsa music clubs in London: An ethnographic study. University of Leicester, Leicester, UK.

- Román-Velázquez, P. 1999. The making of Latin London: Salsa music, place and identity, 176. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315238487.

- Román-Velázquez, P. 2009. “Latin Americans in London and the Dynamics of Diasporic Identities. “ In Comparing Postcolonial Diasporas, edited by Procter James, Keown Michelle and Murphey David, 104–124. London and New York: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230232785.

- Román-Velázquez, P. 2014. “Claiming a Place in the Global City: Urban Regeneration and Latin American Spaces in London.” Political Economy of Technology, Information & Culture Journal (Eptic) 16 (1): 68–83. https://seer.ufs.br/index.php/eptic/article/view/1863.

- Román-Velázquez, P., and N. Hill. 2016. The case for London’s Latin Quarter: Retention, growth and sustainability. London: Latin Elephant. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/files/165924588/The_Case_for_Londons_Latin_Quarter_WEB_FINAL.pdf.

- Román-Velázquez, P.,Retis, J. 2020. Narratives of migration, relocation and belonging: Latin Americans in London, 206. London and New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN: 978-3-030-53444-8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53444-8.

- Sheringham, O. 2010. “Everyday Transnationalism: Religion in the Lives of Brazilian Migrants in London and Brazil.” Geographies of Religion Working Paper Series (No. 2). Newcastle University.

- Talen, E. 2012. “Latino Urbanism: Defining a Cultural Urban Form.” Journal of Urbanism 5 (2–3): 101–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2012.693253.

- Town and Country Planning Association. 2019. London Planning for a Just Society? Exploring How Local Planning Authorities are Embedding Equality and Inclusion in Planning Policy. London: Trust for London and TCPA. https://trustforlondon.fra1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/media/documents/London_-_Planning_for_a_Just_City_FINAL.pdf