ABSTRACT

Placemaking is a fluid term with various conceptualisations, but individuals’ understanding of the term may shape the impact of placemaking projects. This paper aimed to identify conceptualisations of placemaking from two perspectives, theory and practice in the Australian context, and develop an analytical framework for categorising placemaking understandings. Through a systematic literature review (SLR) of 77 articles, a set of four placemaking themes was developed. These themes were expanded through the coding of placemaking definitions from 26 Australian placemaking practitioners gathered through a survey, thus creating a Placemaking Understanding Framework (PUF). The PUF highlighted gaps and overlaps amongst academics and Australian practitioners, showcasing how academia tends to frame placemaking as a process producing relational outcomes (like place attachment, sense of belonging, and connection to nature), whereas Australian practitioners focused on both the relational and physical outcomes of placemaking. By illustrating the breadth of perspectives in placemaking, this study builds on the academia-industry nexus for future placemaking strategies.

Introduction

Placemaking has been theorised in multiple ways across academic disciplines (Convery, Corsane, and Davis Citation2012; Strydom, Puren, and Drewes Citation2018). For instance, the humanist tradition, which opposes the positivist geographical perspectives (Entrikin and Tepple Citation2006), defines placemaking as concerned with people’s emotional attachments to place (Relph Citation1976; Tuan Citation1974). In psychology, the term is grounded in place, narrative, and community empowerment (Toolis Citation2017), while in justice and peace studies, placemaking can be considered a post-conflict peacebuilding tool (McEvoy-Levy Citation2012). In built environment disciplines, placemaking is conceived as a methodology centring the end-users’ perspectives to encourage increased liveability though the exploration of how people perceive, contribute to, and experience a place (Thomas Citation2016; Hu & Chen Citation2018). This interpretation highlights the importance of the physicality and materiality of place (Gosling and Maitland Citation1984).

Designers can employ placemaking as a participatory process to support the delivery of more inclusive and liveable places by shaping spaces into meaningful places (Mateo-Babiano and Lee Citation2019; Project for Public Spaces 2007). Residents in communities like the Sunnyside neighbourhood in Oregon, USA, for instance, re-created a public gathering place using art installations, supporting community revitalisation (Semenza Citation2003). By renewing and revitalising places, placemaking presents an alternative way of supporting urbanisation processes in communities worldwide (Duconseille and Saner Citation2020; Arefi Citation2014; Fincher, Pardy, and Shaw Citation2016).

Placemaking’s role in this process of urbanisation is a multidimensional 2020 involving both the physical and experiential dimensions of place (Sadeghi et al. Citation2022). One aspect of placemaking is concerned with the physical and material characteristics of a space, like the provision of amenities and the focus on encouraging walkability (Sadeghi et al. Citation2022; Lak and Jalalian Citation2017). A second aspect of placemaking focuses on the process of turning a “space” into a “place,” centring around users’ emotional connection to a place (Sadeghi et al. Citation2022; Lak and Jalalian Citation2017). In other words, placemaking can create high-quality spaces but also enable communities to imbue meaning into said spaces (Mateo-Babiano and Lee Citation2019).

However, placemaking practice is multidisciplinary, with disciplines varying in their definitions and prioritisation of physical and relational outcomes (Strydom, Puren, and Drewes Citation2018). When conducting a placemaking project, conscious effort is needed to integrate these diverse perspectives. In doing so, formulating a shared definition of placemaking may be a daunting process (Lew Citation2017). Given the multiplicity of placemaking conceptualisations and objectives that practitioners use, this paper aims to present a framework that can help shed light on these diverse perspectives.

By examining academic and built environment practitioners’ understandings of placemaking, this paper presents placemaking conceptualisations from two key perspectives, theory and practice, in the Australian context. First, through a systematic literature review, it identifies major themes in scholarly placemaking literature. The identified themes inform the development of an analytical framework to categorise different understandings of placemaking, the Placemaking Understanding Framework (PUF). Second, it tests the framework by categorising different understandings of placemaking as expressed through a survey by 26 placemaking practitioners in Australia. This test was used to inform and improve the PUF.

This study worked at the nexus between industry and academia by comparing Australian practitioners’ and global scholars’ understandings of placemaking. We contribute to the growing literature in the placemaking field by illustrating opportunities for bridging the gap between knowledge and action. Informed by this comparison, we propose a common definition that allows for the co-existence of nuanced interpretations of placemaking, and present the Placemaking Understanding Framework (PUF) as a framework that can help practitioners identify the placemaking priorities present on a project-by-project basis. This paper suggests that those involved in placemaking projects create opportunities for an open conversation on the nuanced interpretations of placemaking. This is helpful when integrating both the physical and relational aspects of placemaking, as well as for clarifying project expectations. This dialogue can arguably be a vital starting point in placemaking education and practice.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to explore the extent to which peer-reviewed academic literature examined the characteristics of placemaking processes within urban areas. To narrow the scope, we limited our search to English language peer-reviewed papers published between the 2000–2020 in the Scopus database and create a framework representative of the latest discourse on placemaking. Search terms considered were: “Place, placemaking, place-making, place making; Urban, cities, public space; Attributes, characteristics, quality, built form; Attachment, sense of place, stewardship, sense of belonging, community, meaning, value.” The search query initially resulted in 152 peer-reviewed papers that were screened for content relevance. After eliminating duplicates and irrelevant papers, 77 journal articles, books, and book chapters were identified that specifically addressed the desired topic (see ).

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating the literature search process, starting with identification of articles, assessment of article eligibility, and the final selection of articles for thematic analysis.

The Framework Method for qualitative research developed at the National Centre for Social Research in the UK (Gale et al. Citation2013) provides an appropriate analytical structure to examine different ways of understanding placemaking. It allowed the combination of deductive analysis, where themes and codes were pre-selected based on literature, and inductive analysis, where themes were generated from the data through open coding (Gale et al. Citation2013), and these themes were subsequently refined.

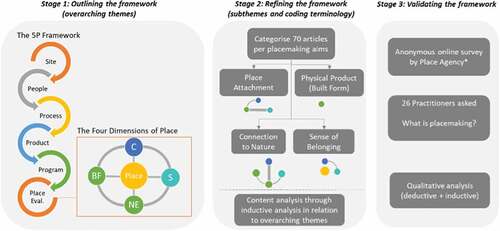

The Placemaking Understanding Framework (PUF) was developed in three stages, namely: 1) developing the overarching themes, 2) refining the themes through the systematic literature review, and 3) testing the framework by exploring Australian practitioners’ understanding of placemaking (see ).

Figure 2. Three stages to developing the PUF. Stage 1: the arrows represent the circles represents the four dimensions of place by Hes et al. Citation2019 including built form (BF), the self (S), the community (C), and natural environment (NE).

In Stage 1, we integrated two placemaking frameworks: the “5P Framework” and the “Four Dimensions of Place Framework,” which explored the processes and outcomes involved in placemaking. The 5P Framework presents an overarching analytical lens in which People, Process, Product, Program and Place Evaluation are presented as five key elements, or building blocks, of placemaking (Mateo-Babiano and Lee Citation2019). The Four Dimensions of Place Framework is specifically linked with a Place Evaluation component, providing an understanding of the relational outcomes sought after by placemaking (Hes et al. Citation2019). Combining the two enabled an initial iteration of an analytical framework which allowed for the identification of codes under five thematic categories, or “dimensions.”

In Stage 2, we deductively analysed academic literature to expand the framework by identifying themes, subthemes, and specific terminology linked to each of the 5P dimensions. The 77 articles selected for review were categorised into at least one of four topics representing the desired placemaking outputs and outcomes identified, namely: place attachment, sense of belonging, connection to nature, and physical product.

In Stage 3, we compared our categorisation with placemaking definitions provided by Australian practitioners. A total of 26 Australian placemaking practitioners participated in an anonymous survey conducted by Place Agency in 2017.Footnote1 These 26 professionals are working in place-related roles, mostly including regional or metropolitan councils. For the purposes of this paper, each respondent was assigned a reference code and number from E01-E26, with the letter “E” referring to the word “expert..”

Using the NVivo analytical software, we coded and analysed survey responses to the question “What is placemaking?” A single response could be coded under multiple dimensions and show various emerging themes. Dimensions, themes, sub-themes and codes were brought together into a table of codes that were independently coded by the three authors, who then came together to discuss, refine and finalise the analytical framework for placemaking understanding.

Results and discussion

Our analysis of 77 academic papers revealed four main outcomes of placemaking. The 12 key themes are response to, place leadership, engagement process, governance, built outcomes, types of space, temporality, quality of the space, economic benefits, place attachment, sense of belonging, and the environment. The outcomes recognised included the physical characteristics of a space as well as three relational outcomes: place attachment, sense of belonging, and connection to nature.

We present our results and discussion simultaneously in five key sections: the value of placemaking, the development of our proposed PUF, and three key debates. For each section we compare the theoretical perspectives with practical perspectives from Australian practitioners. We also detail the analytical framework used to code the survey responses as well as the proportions of practitioners discussing each dimension, theme, and sub-theme of placemaking. We then finalise a placemaking definition that allows for the co-existence of nuanced interpretations of placemaking,

What is the value of placemaking?

Theoretical perspectives

Our initial experience of public space is often visual (i.e. when viewing paintings, photos and pictures of the place), when we visit a place, it becomes physical (Carmona & Tiesdell Citation2007). Not surprisingly, nearly one quarter of the articles analysed placemaking through the lens of the physical products resulting from a placemaking process. The emphasis on the importance of urban form outcomes for placemaking reinforces how historical understandings of the term have focused on the construction and creation of built environments (Newman Citation2016). Yet, as Lefebvre (Citation1991) argue, physical dimensions are but one element of public space, which cannot be extricated from how place is perceived and lived in – placing human experience above urban form.

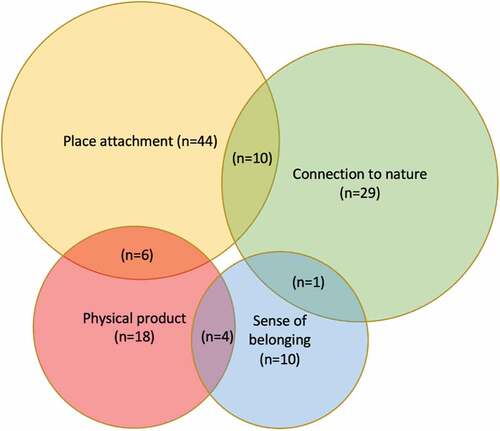

Although the physical aspects of built environments are important, Relph (1976) and Tuan (Citation1974) suggest that the social and relational outcomes resulting from placemaking as a meaning-making process are key to placemaking success. This sentiment is greatly supported amongst academic literature between 2000–2020 as nearly all of the papers support the idea that placemaking can result in relational outcomes such as place attachment (57%), sense of belonging (13%), and connection to nature (38%). The findings of this literature review support the concept of relational outcomes as the glue that binds the social fabric of local communities. The following paragraphs discuss the lenses through which authors discuss these outcomes. While these outcomes are presented separately, they are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, more than a quarter of the papers addressed more than one theme, suggesting that placemaking can simultaneously address multiple, interrelated relational outcomes, whilst influencing one another ().

Figure 3. Overlaps in thematic categories. The size of each of the four circles corresponds to the sample size (n=x) of each thematic category, and the overlapping areas between circles represent the papers that discussed the two overlapping themes. Notably, there was no overlap between all four themes.

Over half of the papers discussed “place attachment,” making it the most researched theme). Place attachment refers to placemaking’s potential to strengthen the emotional relationship between people and place. Researchers incorporated a socio-behavioural component in their discussion by, for example, evaluating how much time residents spent in local areas and interacting with one another (see Khosravi, Bahrainy, and Tehrani Citation2020; Kohlbacher, Reeger, and Schnell Citation2015; Aiello, Ardone, and Scopelliti Citation2010; Tournois and Rollero Citation2020). Another relational outcome with important social impact was sense of belonging), referring to the emotional relationship or connectedness between an individual and their socio-cultural context. Some researchers examined the relationship between urban form and the creation of social networks within the community, showcasing how the street characteristics can support or hinder social connection (Pendola and Gen Citation2008; Whalen et al. Citation2012; Cheshire, Wickes, and White Citation2013). Others instead posited that, as a community intervention tool, placemaking can support community bonding, with beneficial mental health impacts for the elderly (Young, Russell, and Powers Citation2004; Oswald and Konopik Citation2015) and the general community (Nogueira Citation2009).

The second most discussed theme, “connection to nature,” discussed people’s relationships with their natural surroundings. Over one-third of the papers focused on connection to nature, and these authors collectively recognised the importance of urban green spaces to the community and reported multiple benefits of urban greenery such as aesthetic values of greenery (Rostami et al. Citation2015), eco-literacy and intercultural interaction (Malone Citation2004; Peters, Elands, and Buijs Citation2010), and the restorative effect of greenery on people’s mental health and wellbeing (Bang et al. Citation2018; Rostami et al. Citation2014, Citation2015; Aliyas and Masoudi Nezhad Citation2019).

While many papers focused on the recreational service provided by nature and its ability to facilitate social interactions (Aliyas and Masoudi Nezhad Citation2019; Peters, Elands, and Buijs Citation2010; Ostoić et al. Citation2020; Hårsman Wahlström, Kourtit, and Nijkamp Citation2020) only three papers explicitly discussed placemaking’s potential to elicit stewardship (Jones et al. Citation2021; Ghavampour and Vale Citation2019; Ryan Citation2005). These authors brought to light how users’ experiences can influence their perspectives on environmental management (Ryan Citation2005) or result in increased social interaction (Jones et al. Citation2021). Lastly, Ghavampour and Vale (Citation2019) adopted a broader scope and critiqued modern placemaking processes, urging practitioners to shift away from a physical design-oriented approach to more a balanced placemaking model. This gap may indicate that placemaking studies exploring the relationship between nature and people have not gone beyond the utilitarian lens. A utilitarian view focuses on what nature can provide to people, rather than viewing people-nature as a bilateral, symbiotic relationship.

Practical perspectives by Australian practitioners

Amongst the reviewed literature, there were no papers that explored placemaking from the point of view of the professional community. Thus, we used the definition of “placemaking” provided by 26 placemaking practitioners in Australia to infer how this term is understood by practitioners and the attributed value to placemaking process.

Like academics, most placemaking practitioners discussed the importance of placemaking from a relational perspective. However, compared to academia, practitioners tended to prioritise the physical outcomes provided by placemaking over social and relational outcomes. For example, the vast majority of practitioners emphasised to the ability of placemaking to deliver temporal or permanent spaces that revitalise the community (see ). Half of the practitioners described placemaking as a Process, and about one-quarter said that placemaking is about Program, or place-keeping. People was the least frequently discussed of the five dimensions, with five practitioners discussing it. People were, however, alluded to in other dimensions, for instance, in Process (i.e. through mentions of place leadership, engagement and governance).

Table 1. Dimensions, themes and sub-themes derived from placemaking practitioners’ survey responses, including the percentages (%) of practitioners discussing each dimension, theme, and sub-theme.

Lastly, the language used by practitioners highlighted a view that placemaking can build relational outcomes. Nearly half of the 26 practitioners mentioned sense of belonging, and nine mentioned place attachment. Meanwhile, placemaking’s potential to support the environmental dimensions of place was only acknowledged by one practitioner, which arguably indicates the limited consideration of nature’s (potential) role in placemaking practice. Concepts of communities’ emotional connection to nature and stewardship were not brought forth at all in practitioners’ definitions of placemaking. These understandings are further explored and discussed in the following section.

Developing and testing the PUF: emerging themes amongst placemaking practitioners

This article created a Placemaking Understanding Framework (PUF) informed by three layers of perspectives. The first layer, informed by previous work by the authors used the 5P Framework suggested by Mateo-Babiano et al. (Hårsman Wahlström, Kourtit, and Nijkamp Citation2020) to identify five key dimensions of placemaking: people, process, product, program and place outcomes. The second layer infused the language and terminology used by the articles identified in the in the literature review. It added a series of themes, subthemes and codes that reflect the components of placemaking that have been researched and discussed over the past 20 years. Lastly, the third layer coded and incorporated into the framework the language used by a small set of practitioners when discussing placemaking. illustrates the differences in the PUF framework and terminology used to discuss placemaking from an academic or practitioner perspective.

Table 2. Analytical framework used to code survey responses.

It is important to note, however, that the framework has its limitations. One major limitation is that some themes had significant overlap – the “engagement process” theme and the “place leadership” themes under Process being notable examples, as these themes were interrelated. A respondent that understood placemaking as a bottom-up, grassroots process would also understand placemaking as having a deep level of citizen engagement, whereas a respondent that saw placemaking as a top-down process may have tended towards a lower level of citizen engagement.

Throughout the following sections, we present key differences in placemaking understandings amongst these two different professional communities. Particularly, we discuss the differences in language or “codes” used by each professional community as a reference for the key values attributed to placemaking. We present our discussion across three key debates emerging from both academia and professional understandings of placemaking: placemaking as a design process or a relational making process, the product vs program debate, and placemaking as a liveability response. This discussion reveals how placemaking practitioners emphasise relational outcomes of placemaking, echoing the academic literature, but also place a strong emphasis on physical products of placemaking. This may be because practitioners will be evaluated on the tangible, measurable products of the placemaking and design process, whereas academics have greater capacity to theorise on the intangible elements of placemaking.

Placemaking as a design process or a relational process

Theoretical perspectives

All selected papers framed placemaking as a process, highlighting its ongoing and iterative nature. As Newman (Citation2016) aptly asserts, placemaking is best understood as a dynamic process where places are always in movement – arguing that place “is a verb (action), not a noun (a stable thing)” (p. 399). He further describes place as a means of conceptualising the relationship between people and their spatial settings, and states that the development of place is a human-centred process.

The literature agreed that the ability of placemaking to result in long-term relational outcomes is inherently dependent on the process. However, whilst some articles framed placemaking as a design process, others considered it a relational process. For instance, Moulay et al. (Citation2018), Sancar and Severcan (Citation2010), Thwaites and Simkins (Citation2005), Pancholi, Yigitcanlar, and Guaralda (Citation2015), Newman (Citation2016), Sun et al. (Citation2020), and Khosravi, Bahrainy, and Tehrani (Citation2020) framed placemaking as an urban design process where the built environment can ultimately create relational outcomes, where the physical product integrates the social context of a given place and reinforces place identity.

Meanwhile, other authors argued that the main objective of placemaking is that of establishing emotional connections to place. In this way, physical interventions (if present) are simply a means of creating attachment to place (i.Ghavampour and Vale Citation2019). These attachments in turn can be understood as a process of creating or enhancing meaning of a place (Langemeyer et al. Citation2018), connecting to other people (Pendola and Gen Citation2008; Whalen et al. Citation2012; Cheshire, Wickes, and White Citation2013) or even connecting to the natural environment (Malone Citation2004; Peters, Elands, and Buijs Citation2010; Bang et al. Citation2018; Aliyas and Masoudi Nezhad Citation2019). Other authors underscored the economic dimensions of placemaking (Zhao, Huang, and Sui Citation2019; Tournois Citation2018; Rostami et al. Citation2015; Ujang Citation2014). This reinforced the position of this SLR to understand placemaking as an outcome-focused process.

Practical perspectives by Australian practitioners

The four main types of relational outcomes that emerged through the placemaking definitions provided by survey respondents were economic benefits, environmental stewardship, place attachment (or sense of place), and sense of belonging. These findings reinforce the emphasis on relational outcomes in the literature (Chamlee-Wright and Storr Citation2009; Rostami et al. Citation2015; Nogueira Citation2009). Nearly half of the 26 practitioners discussed sense of belonging, emphasising the importance of “connectedness and [places] for social exchange” (respondent E12). Whereas the practitioners strongly emphasised sense of belonging, the literature did not share this same emphasis, with only 10 of the 77 papers discussing belonging.

The literature placed a greater emphasis on place attachment, with over half of the 77 articles discussing attachment compared to about one-third of the 26 practitioners, who referred to placemaking as a means of developing places that encourage a “strong sense of ‘my/our space’” (respondent E15).

Few practitioners and academics discussed economic benefits as an outcome of placemaking. Only seven of the 77 articles and two of the 26 practitioners discussed the economic benefits of placemaking, with these practitioners discussing placemaking as a “process that delivers sustainable economic benefits to communities” (respondent E03) and “bringing people together for positive social and economic outcomes” (respondent E07).

Only one practitioner discussed environmental stewardship – with this one practitioner only briefly mentioning placemaking’s role in shaping a place’s “environmental performance” (respondent E11). This finding confirms an industry bias towards placemaking benefitting people, and not necessarily towards people’s role in environmental stewardship. Whilst there is an evolving worldview in pedagogy that sees humans as part of larger ecosystems (Bush et al. Citation2019; Hes & Coenen Citation2018), this is a relatively new trend in higher education. The lack of emphasis on the role of humans as part of nature within placemaking literature is reflected in the lack of practitioners discussing stewardship. In contrast, over one-third of the 77 articles discussed stewardship as a key relational outcome.

Moreover, three themes related to Process were identified from responses that framed placemaking as a process: place leadership (who leads?), engagement process (how do people work together?), and governance (how are project decisions made?). Amongst the place leadership responses, these process typologies denote a perceived role of the different stakeholders involved in placemaking. For example, one practitioner defined placemaking as a “citizen-led, collaborative and participatory process” (respondent E17), framing it as a bottom-up process, whereas another defined it as “[capitalising] on a community’s assets” (respondent E13), where institutions lead a top-down placemaking process.

Five of the 13 practitioners that discussed Process defined it as a top-down process where the responsibility, ideation and decision-making lie with the authority figures designing, planning and financing the project. For example, one practitioner defined placemaking as “the ability to ensure community are accessing places and spaces in a way that encourages people to use and interact with the space” (respondent E10), implying that designers or planners are responsible for leading the process of placemaking. Three practitioners defined placemaking as a flexible, organic process rather than a rigid, step by step procedure, placing emphasis on placemaking as a collaboration between the community, planners, and designers. One possible explanation of understanding placemaking as a top-down process may be the practitioners’ disciplinary backgrounds – for instance, in urban planning or architecture, practitioners tend to be more actively leading (rather than facilitating) the placemaking process (Liu et al. Citation2020; Aliyas & Masoudi Nezhad Citation2019).

The ‘product vs program’ debate

Theoretical perspectives

The physical products of placemaking also emerged as a common theme in this literature. Newman (Citation2016), for example, departed from trends in place attachment literature (i.e. a focus on people-place relationships), instead drawing attention to how built environments contribute to place. Cai and He (Citation2016) also discussed the place-space relationship, examining how urban high-star hotels allow consumers to experience place (or lack thereof).

Whereas the aforementioned authors focused on how space shapes place, two authors extended this discussion by linking space and place with sense of place. Pancholi, Yigitcanlar, and Guaralda (Citation2015) observations on an urban village in Australia, for example, framed placemaking as a means of designing physical spaces that mirror the local identity of a place, thus creating a “spatio-temporal entity” (p. 4). Rajendran (Citation2016)’s discussion of space-place and sense of place was more overt, however, asserting that the dynamic nature of the contemporary urban form can obstruct the development of sense of place. Although this paper focuses on the potential for unconventional urban spaces for fostering sense of place – whereas focuses on residential development – both authors concurred that the design of urban spaces can either further or hinder relational outcomes like sense of place.

It should be noted, however, that the literature mainly links Product to its potential impacts on humans through discussion of sense of place and place attachment. It does not, however, discuss the links between Product and the natural environment. There remains a question of whether placemaking academics sufficiently consider the impact of the built environment on nature, specifically how animals move and exist with humans in urban areas.

Extending beyond this emphasis on the physical design of a place, some authors argue that programming is more critical to placemaking than the physical product. Programming is concerned with how people engage with space in multiple ways across spatial and temporal dimensions, and maintains that social contacts are more important to creating place attachment than the physical environment of a given space (Mateo-Babiano & Lee Citation2019). Kohlbacher, Reeger, and Schnell (Citation2015)’s study on migrant residents in an area of Rome further reinforces the importance of programming to realise relational outcomes, arguing that how a place was perceived and experienced by its residents was more relevant to creating place attachment than the physical attributes of that area. Similarly, Khosravi et al. (2019) asserted that the socio-behavioural dimensions of a neighbourhood determined residents’ place attachment.

Aiello et al. (Citation2010) study did not focus on the migrant context, instead focusing on two neighbourhoods in Rome, its findings also suggested that social perceptions of place shaped residents’ neighbourhood attachment. Moreover, Panek et al.’s (Citation2020) study on gentrification in Pittsburgh found that changes in the physical attributes of a place do not necessarily have to change in order to impact residents’ place attachment. This study examined residents’ sense of place in a gentrifying neighbourhood, and the long-term residents of the neighbourhood had significantly different attitudes compared to newcomers. In other words, “the long-term residents of this neighbourhood are being displaced by newcomers, even though they are remaining in place” (Panek et al. Citation2020; 10).

Practical perspectives by Australian practitioners

From the survey responses discussing Product, three main themes emerged: 1) built outcomes, 2) types of space, and 3) temporality. All six of the 26 practitioners that discussed type of space framed placemaking as taking place in public spaces – one respondent defined placemaking as “a multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and management of public space” (respondent E09).

As for the temporality of physical products, practitioners either discussed physical products as being permanent built, like “major transformational projects” (respondent E11) and “permanent and space activation improvement” (respondent E04), or temporary built like “small-scale events and festivals” (respondent E11) and “neighbourhood activities and/or amenity development” (respondent E08).

This emphasis on public space aligns with the findings of the literature review, where public and residential spaces were emphasised as physical outcomes of placemaking (Kohlbacher, Reeger, and Schnell Citation2015; Khosravi et al. Citation2019; Pancholi, Yigitcanlar, and Guaralda Citation2015). Interestingly, no practitioners made reference to scale (e.g. small scale, large scale) when discussing the physical dimensions of placemaking. This underscores a need for those involved in the placemaking industry to further consider how placemaking can go beyond activation, where physical outcomes can fall on a spectrum of scale. Moreover, the emphasis on permanent and temporary built outcomes indicates that respondents tend to refer to placemaking as tactical urbanism, which often involves using small-scale and low-cost interventions to work towards place activation (YassinCitation2019).

Moreover, only one theme emerged related to Program, or place-keeping: quality of the space, with “management and maintenance” as its sub-theme. The six practitioners discussing Program referred to management and maintenance using phrases like “management of public spaces” (respondent E09) and “the coming together of diverse disciplines and knowledges to build and maintain spaces” (respondent E01). The emphasis on management and maintenance may be due to a focus on design and planning of a space, aligning with the placemaking literature that emphasises the design and planning elements of programming (Raymond, Kyttä, and Stedman Citation2017; Bosco, Gravina, and Muzzillo Citation2005; Ryan Citation2005; Spartz and Shaw Citation2011). The low proportion of practitioners discussing Program may be due to practitioners’ mindsets around placemaking being strongly linked to the project cycle itself. Whilst practitioners may conceptually consider programming, they may prioritise other aspects of placemaking over the implementation of long-term programming decisions.

Placemaking as a liveability response

Theoretical perspectives

Finally, another major theme that emerged from this literature review is the framing of placemaking as a response to crises like displacement or disasters. The literature illustrates ways in which placemaking can generate place attachment, a key factor in determining whether communities can adapt to social upheaval. Fried (Citation2000), for example, emphasised the importance of place attachment and identity for poor, ethnic migrant communities undergoing displacement. For these migrant communities, placemaking can be used to mitigate the grief associated with residential relocation, and fostering place attachment amongst people settling in new communities (Fried Citation2000).

Tournois & Rollero’s (Citation2020) study employed a similar scope, exploring the relationship between place attachment and place commitment in Serbia, which underwent a series of disruptive changes over the several decades. This study found that people with high levels of place attachment were more willing to become socially engaged in their communities and become drivers of urban renewal. Tournois and Rollero (Citation2020) highlighted that the findings of this study were particularly relevant in countries, cities, and towns experiencing dramatic changes like war.

Likewise, Chamlee-Wright & Storr’s (2009) study on disaster recovery in New Orleans echoed this sentiment, underscoring the importance of place attachment in rebuilding disaster-affected places in low- and middle-income neighbourhoods. Despite a lack of material resources, New Orleans residents returned to their communities to rebuild post-Hurricane Katrina, and the success of these recovery efforts could in part be attributed to a high degree of place attachment (Chamlee-Wright and Storr Citation2009). Whereas Fried (Citation2000) asserted that rebuilding efforts can become dysfunctional when communities “cling to the fragments of a home” that cannot be rebuilt (p. 202), Chamlee-Wright and Storr (Citation2009) argued in favour of individual agency. After a disaster, individuals decide whether to relocate or to rebuild a community that is well-suited to their needs. When individuals are highly dependent on a specific place, Chamlee-Wright and Storr (Citation2009) described the decision to rebuild – rather than relocate – is understandable.

Practical perspectives by Australian practitioners

Whereas the literature highlights placemaking’s role in responding to crises, practitioners emphasised how placemaking can foster liveability in communities. All five of the practitioners discussing People discussed community needs, defining placemaking as “creating avenues for people to interact with place and to utilise public spaces in ways that reflect the communities needs and aspirations” (respondent E20).

This emphasis on community needs suggests that practitioners view community needs and values as one of placemaking’s central objectives. The focus on community needs also open up possibilities in terms of where the decision-making power lies across the placemaking. However, whereas the literature on placemaking as a crisis response acknowledged the role of gentrification in the displacement of communities, the practitioners did not make reference to displacement or other disruptive phenomena.

If viewed through the lens of Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation, a response alluding to place partnership would likely fall between the “delegated power” and “partnership” level, where citizens are able to negotiate and engage in decision-making regarding placemaking (Arnstein 2019). Alluding to a place leadership model where communities lead and have ownership over the placemaking process, one practitioner contends that placemaking was about “creating a community of inclusive activity, co-creation and ownership” (respondent E12). This places emphasis on the role of the community as co-creators of place, which arguably represents the highest level of engagement in Arnstein’s ladder (Arnstein 2019).

Defining placemaking

Given the plurality of definitions, we assert that it is important to refocus on what the placemaking process seeks to achieve. In our view, there is a need to emphasise the relational outcomes of placemaking as a means of supporting longer term stewardship over place. We thus define placemaking as follows:

Placemaking is a relationship-building process seeking to identify, re-ignite and/or foster an emotional connection between individuals, communities, and their setting (place), including nature; the process recognises a diversity of methodologies to respond appropriately and in a timely manner, supporting longer term place sustainability, resilience and stewardship. The process, applied by a professional is intentional, integrates situated knowledge and respect for the local context of place.

Our definition has three important components. The first component emphasises that the driving-force for projects remains on those sought-after relational outcomes, highlighting the integral relationship of humans and non-humans. Second, we state that there are many potential pathways for placemaking typologies that can be drawn from to achieve the objectives of the project. Third, our definition calls for intentional and carefully considered actions by the placemaker to support longer term outcomes. The design process responds to the specific purpose (i.e. the relational outcome(s) sought) and context of the project: that is the “when,” “how” and “what” placemaking should look like directly responds to the “why” and the “where.” As such, the rationale behind the design process should be clearly articulated and evaluated.

With this definition, we wish to celebrate the plurality of views and interpretations of what placemaking is and looks like. We also place value on a placemaker’s ability to articulate the rationale behind their proposed process and draw a parallel between the purpose, place and context of the project.

We are not seeking for all placemakers to begin quoting this definition. Instead, our contribution to the body of placemaking knowledge lies in providing a framework for placemakers to consolidate the outcomes they are looking to achieve, and the processes to achieve these. Our definition can serve as a starting point for placemakers to use when planning placemaking interventions that are designed to achieve clearly defined physical and relational outcomes.

A team starting a placemaking project should clarify their individual definitions of placemaking. By exploring how each team member defines placemaking, individual expectations and values around placemaking outcomes and processes can be clarified. To do so, teams can use the codes and language presented in our analytical framework (). For example, should placemaking address community needs, or respond to a crisis? Should the process be top-down, bottom-up, or flexible? Once a common understanding is reached among the team, the remainder of the placemaking process can begin.

Furthermore, by highlighting the importance of people’s emotional connections to place, our definition can allow placemakers to prioritise environmental stewardship as a key relational outcome of the placemaking process – filling an existing gap in current placemaking practices. In using this definition, those involved in placemaking can consider environmental stewardship as a key relational outcome to be sought (Hes et al. Citation2019), and thus begin to embed “nature-in-place” strategies, regenerative placemaking, and nature-based solutions in placemaking practice (Bush and Doyon Citation2019).

Conclusion

Place exists with or without the placemaking process, contrary to what the term “making” implies. Because “place” itself is a multidimensional and intangible concept, so then is “placemaking,” presenting a challenge to the understanding, planning and realisation of placemaking activities. By examining the differences in theoretical and practitioner perspectives on placemaking, this paper has shed light on critical gaps but also afforded the opportunity to re-define how placemaking is conceptualised and practiced in Australia.

Through a systematic literature review and anonymous practitioner survey, this study found that placemaking scholars highlighted the importance of relational outcomes of placemaking, like place attachment and sense of belonging. On the other hand, Australian practitioners see placemaking as a process producing physical outcomes. Practitioners’ emphasis on material outcomes may stem from the fact that practitioners are engaged to produce physical, design-based outcomes. Consolidating these relational and physical outcomes of the term can influence both the process and project of placemaking.

Adding to this complexity is the existence of a large variety of reasons for shaping places, as well as the multiple publics that can benefit from better public places. For example, Wyckoff (Citation2014) defines at least four commonly accepted types of placemaking typologies in academic literature: placemaking, strategic placemaking, tactical placemaking and creative placemaking. Other authors highlight emerging processes such as digital placemaking (Griffiths & Barbour Citation2016) and regenerative placemaking (Hernandez-Santin et al. Citation2020). The definition of each of these terms is directly linked to the specific approach applied to pursue the sought-after emotional attachment to place. With new strategies emerging constantly, the discourse on placemaking remains “fuzzy,” this paper highlights the challenges brought about by the lack of a common language and understanding of the concept of placemaking itself, particularly between theory and action, and proposed a shared definition.

The analysis of theoretical and practitioner perspectives in this paper revealed that nature-focused placemaking strategies (i.e. regenerative placemaking, environmental placemaking), particularly ones prioritising environmental stewardship, are still emerging concepts in placemaking practice. This paper calls for a stronger link between theory and practice in placemaking by underscoring the human-nature nexus. A shared understanding of the intrinsic relationship between settlements and nature, and the motivations to harness interconnection can advance placemaking practice.

A shared definition of placemaking allows for placemakers to clearly articulate their objectives in strengthening relationships between people, places, and the environment. The definition of placemaking offered in this paper provides a way to privilege relational outcomes, particularly with nature, in placemaking processes. Doing so will allow for placemakers to adopt socially centred approaches to placemaking that develop relationships between people and places, and between people and the environment. By providing a conceptualisation of placemaking that encapsulates both theoretical and practitioner perspectives, this paper works at the nexus between industry and academia.

There are, however, several further directions that future research could take. Our literature review on placemaking called attention to the lack of literature on nature in relation to placemaking. Placemaking research could then focus on the ways in which design-based placemaking strategies can contribute to either the degradation or regeneration of a place’s surrounding environment.

Our research also highlights relationship-building as a sought-after outcome of the placemaking process. Placemaking has a critical role to play in shaping people’s relationships to place (Convery, Corsane, and Davis Citation2012). Leveraging on placemaking as a relationship-based co-creation process, the placemaking movement in the past 40 years has continued to evolve as a process that enables people to invest (public) places with meaning (Mateo-Babiano & Lee 2020). This paper illustrates the breadth of Australian perspectives in placemaking while also calling for a stronger academia-industry nexus in placemaking for resilient urban strategies.

Acknowledgments

We, the authors, would like to thank the support of The Myer Foundation for funding the Place Agency Placemaking Sandbox project. We thank the 26 placemaking practitioners, who agreed to be interviewed for this study, providing the basis for this paper. The authors would like to extend their utmost gratitude to all individuals, groups and associations who contributed their time and resources to this study; this includes the reviewers who have provided careful and considered comments that elevated this paper. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not reflect any organisations. The authors take full responsibility for all errors and omissions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Place Agency is a multi-university placemaking education program developed by seven Australian Universities and practitioner partners. In March 2018- December (2018), Place Agency conducted a small survey exploring industry perspectives of placemaking and incorporated this database into their research activities on placemaking pedagogy. Survey responses were de-identified, and each response was assigned a number. Research participants included professionals working in place-related roles who showed support for, or interest in, the outcomes of the Place Agency project, but were not committed to the creation of educational resources as other practitioner partners. Place Agency sent 21 emails inviting practitioners to participate in the anonymous survey. In this email, Place Agency encouraged practitioners to complete the surveys themselves and to distribute the survey among their networks. After sending out these 21 emails, Place Agency received 26 survey responses. To ensure anonymity, participants were de-identified. While no incentive was provided, participation was voluntary and had no effect practitioners’ relationship with the universities.

References

- Aiello, A., R. G. Ardone, and M. Scopelliti. 2010. “Neighbourhood Planning Improvement: Physical Attributes, Cognitive and Affective Evaluation and Activities in Two Neighbourhoods in Rome.” Evaluation and Program Planning 33 (3): 264–275. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.10.004.

- Aliyas, Z., and S. Masoudi Nezhad. 2019. “The Role of Historical Persian Gardens as Urban Green Spaces: Psychological, Physical, and Social Aspects.” Environmental Justice 12 (3): 132–139. doi:10.1089/env.2018.0034.

- Arefi, M. 2014. “Deconstructing Placemaking: Needs, Opportunities, and Assets.” Deconstructing Placemaking: Needs, Opportunities, and Assets 1–140. doi:10.4324/9781315777924.

- Bang, K. -., S, S. Kim, M. K. Song, K. I. Kang, and Y. Jeong. 2018. “The Effects of a Health Promotion Program Using Urban Forests and Nursing Student Mentors on the Perceived and Psychological Health of Elementary School Children in Vulnerable Populations.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (9): 1977. doi:10.3390/ijerph15091977.

- Bosco, A., E. Gravina, and F. Muzzillo. 2005. “Vegetation as Relevant Element of Dwelling for Inside-Outside Space.” International Journal for Housing Science and Its Applications 29 (1): 45–56.

- Bush, J., and A. Doyon. 2019. “Building Urban Resilience with Nature-Based Solutions: How Can Urban Planning Contribute?” Cities 95: 102483. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102483.

- Bush, J., D. Hes, and C. Hernandez-Santin. 2019. “Nature in Place: Placemaking in the Biosphere.“ In Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment. ISBN: 9789813296244. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cai, X., and H. He. 2016. “Place and Placelessness of Modern Urban High-Star Level Hotels: Case Studies in Guangzhou.” Dili Xuebao/Acta Geographica Sinica 71 (2): 322–337. doi:10.11821/dlxb201602011.

- Carmona, M., and S. Tiesdell, eds. 2007. Urban Design Reader. Elsevier/Architectural Press.

- Chamlee-Wright, E., and V. H. Storr. 2009. ““There’s No Place Like New Orleans”: Sense of Place and Community Recovery in the Ninth Ward After Hurricane Katrina.” Journal of Urban Affairs 31 (5): 615–634. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2009.00479.x.

- Cheshire, L., R. Wickes, and G. White. 2013. “New Suburbs in the Making? Locating Master Planned Estates in a Comparative Analysis of Suburbs in South-East Queensland.” Urban Policy and Research 31 (3): 281–299. doi:10.1080/08111146.2013.787357.

- Clemente, M., and L. Salvati. 2017. “‘Interrupted’ Landscapes: Post-Earthquake Reconstruction in Between Urban Renewal and Social Identity of Local Communities.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 9 (11): 2015. doi:10.3390/su9112015.

- Cole, I. 2013. “Whose Place? Whose History? Contrasting Narratives and Experiences of Neighbourhood Change and Housing Renewal.” Housing, Theory and Society 30 (1): 65–83. doi:10.1080/14036096.2012.683295.

- Convery, I., G. Corsane, and P. Davis. 2012. Making Sense of Place: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Woodbridge, Suffolk; Rochester, NY: Boydell & Brewer. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt820r9.

- Corcoran, M. P. 2010. “Goda’s Golden Acre for Children’: Pastoralism and Sense of Place in New Suburban Communities.” Urban Studies 47 (12): 2537–2554. doi:10.1177/0042098009359031.

- Cross, J. E., C. M. Keske, M. G. Lacy, D. L. K. Hoag, and C. T. Bastian. 2011. “Adoption of Conservation Easements Among Agricultural Landowners in Colorado and Wyoming: The Role of Economic Dependence and Sense of Place.” Landscape and Urban Planning 101 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.01.005.

- Duconseille, F., and R. Saner. 2020. “Creative Placemaking for Inclusive Urban Landscapes.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 50 (3): 137–154. doi:10.1080/10632921.2020.1754985.

- Entrikin, J. N., and J. H. Tepple. 2006. “Humanism and Democratic Place-Making.” Approaches to Human Geography 1.

- Fincher, R., M. Pardy, and K. Shaw. 2016. “Place-Making or Place-Masking? The Everyday Political Economy of “Making Place.” Planning Theory & Practice 17 (4): 516–536. doi:10.1080/14649357.2016.1217344.

- Fried, M. 2000. “Continuities and Discontinuities of Place.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (3): 193–205. doi:10.1006/jevp.1999.0154.

- Gale N K, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S and Redwood S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol, 13(1), 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Ghavampour, E., and B. Vale. 2019. “Revisiting the “Model of Place”: A Comparative Study of Placemaking and Sustainability.” Urban Planning 4 (2): 196–206. doi:10.17645/up.v4i2.2015.

- Goldhaber, R., and R. Donaldson. 2012. “Alternative Reflections on the Elderly’s Sense of Place in a South African Gated Retirement Village.” South African Review of Sociology 43 (3): 64–80. doi:10.1080/21528586.2012.727548.

- Gosling, D., and B. Maitland. 1984. Concepts of Urban Design. London & New York: Academy Editions & St Martin’s Press.

- Griffiths, M., & Barbour, K. (2016). Making publics, making places. In M. Griffiths & K. Barbour (Eds.), Making Publics, Making Places (pp. 1–8): University of Adelaide Press.

- Hakim, B. S. 2007. “Generative Processes for Revitalizing Historic Towns or Heritage Districts.” Urban Design International 12 (2–3): 87–99. doi:10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000194.

- Hårsman Wahlström, M., K. Kourtit, and P. Nijkamp. 2020. “Planning Cities4people–A Body and Soul Analysis of Urban Neighbourhoods.” Public Management Review 22 (5): 687–700. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1718190.

- Hernandez-Santin, C., D. Hes, T. Beer, and L. Lewis. 2020. “Regenerative Placemaking: Creating a New Model for Place Development by Bringing Together Regenerative and Placemaking Processes.“ In Designing Sustainable Cities, edited by R. Roggema, 53–68. Cham: Springer.

- Hes, D., Coenen, L. (2018). Regenerative Development and Transitions Thinking. In: Bush, J., Hes, D., Bush, J., Hes, D. (eds) Enabling Eco-Cities. Palgrave Pivot, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7320-5_2

- Hes, D., C. Hernandez-Santin, T. Beer, and S. W. Huang. 2019. “Place Evaluation: Measuring What Matters by Prioritising Relationships.” Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment 275–303. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9624-4_13.

- Hu M and Chen R. (2018). A Framework for Understanding Sense of Place in an Urban Design Context. Urban Science, 2(2), 34 10.3390/urbansci2020034

- Jones, M. S., T. L. Teel, J. Solomon, and J. Weiss. 2021. “Evolving Systems of Pro-Environmental Behavior Among Wildscape Gardeners.” Landscape and Urban Planning 207: 207. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.104018.

- Khosravi, H., H. Bahrainy, and S. O. Tehrani. 2020. “Neighbourhood Morphology, Genuine Self-Expression and Place Attachment, the Case of Tehran Neighbourhoods.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 24 (3): 397–418. doi:10.1080/12265934.2019.1698311.

- Kimpton, A., R. Wickes, and J. Corcoran. 2014. “Greenspace and Place Attachment: Do Greener Suburbs Lead to Greater Residential Place Attachment?” Urban Policy and Research 32 (4): 477–497. doi:10.1080/08111146.2014.908769.

- Kohlbacher, J., U. Reeger, and P. Schnell. 2015. “Place Attachment and Social Ties - Migrants and Natives in Three Urban Settings in Vienna.” Population, Space and Place 21 (5): 446–462. doi:10.1002/psp.1923.

- Lak, A., and S. Jalalian. 2017. “Experience of the Meaning of Urban Space: Application of Qualitative Content Analysis in Discovering the Meaning of ‘Ferdow Gardens.” Iran Journal of Architectural Studies 7 (13): 71–80.

- Langemeyer, J., M. Camps-Calvet, L. Calvet-Mir, S. Barthel, and E. Gómez-Baggethun. 2018. “Stewardship of Urban Ecosystem Services: Understanding the Value(s) of Urban Gardens in Barcelona.” Landscape and Urban Planning 170: 79–89. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.09.013.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford, UK.

- Lew, A.A. 2017. “Tourism Planning and Place Making: Place-Making or Placemaking?” Tourism Geographiess 19 (3): 448–466. doi:10.1080/14616688.2017.1282007.

- Liu, Q., W. Fu, C. C. K. van den Bosch, Y. Xiao, Z. Zhu, D. You, N. Zhu, Q. Huang, and S. Lan. 2018. “Do Local Landscape Elements Enhance Individuals’ Place Attachment to New Environments? A Cross-Regional Comparative Study in China.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 10 (9): 3100. doi:10.3390/su10093100.

- Liu, Q., Y. Wu, Y. Xiao, W. Fu, Z. Zhuo, C. C. K. van den Bosch, Q. Huang, and S. Lan. 2020. “More Meaningful, More Restorative? Linking Local Landscape Characteristics and Place Attachment to Restorative Perceptions of Urban Park Visitors.” Landscape and Urban Planning 197: 103763. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103763.

- Malone, K. 2004. ““Holding Environments”: Creating Spaces to Support Children’s Environmental Learning in the 21st Century.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 20 (2): 53–66. doi:10.1017/S0814062600002202.

- Mateo-Babiano, I., and G. Lee. 2019. “People in Place: Placemaking Fundamentals.” Placemaking Fundamentals for the Built Environment 15–38. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9624-4_2.

- McEvoy-Levy, S. 2012. “Youth Spaces in Haunted Places: Placemaking for Peacebuilding in Theory and Practice.” International Journal of Peace Studies 17 (2): 1–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41853033.

- Moulay, A., N. Ujang, S. Maulan, and S. Ismail. 2018. “Understanding the Process of Parks’ Attachment: Interrelation Between Place Attachment, Behavioural Tendencies, and the Use of Public Place.” City, Culture and Society 14: 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2017.12.002.

- Natapov, A., D. Czamanski, and D. Fisher-Gewirtzman. 2013. “Can Visibility Predict Location? Visibility Graph of Food and Drink Facilities in the City.” Survey Review 45 (333): 462–471. doi:10.1179/1752270613Y.0000000057.

- Newman, G. D. 2016. “The Eidos of Urban Form: A Framework for Heritage-Based Place Making.” Journal of Urbanism International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 9 (4): 388–407. doi:10.1080/17549175.2015.1070367.

- Nogueira, H. 2009. “Healthy Communities: The Challenge of Social Capital in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area.” Health & Place 15 (1): 133–139. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.03.005.

- Ostoić, S. K., A. M. Marin, M. Kičić, and D. Vuletić. 2020. “Qualitative Exploration of Perception and Use of Cultural Ecosystem Services from Tree-Based Urban Green Space in the City of Zagreb (Croatia).” Forests 11 (8): 876. doi:10.3390/f11080876.

- Oswald, F., and N. Konopik. 2015. “Impact of Out-Of-Home Activities, Neighborhood and Urban-Related Identity on Well-Being in Old Age.” Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie 48 (5): 401–407. doi:10.1007/s00391-015-0912-1.

- Özkan, D. G., and S. Yilmaz. 2019. “The Effects of Physical and Social Attributes of Place on Place Attachment a Case Study on Trabzon Urban Squares.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 13 (1): 133–150. doi:10.1108/ARCH-11-2018-0010.

- Pancholi, S., T. Yigitcanlar, and M. Guaralda. 2015. “Public Space Design of Knowledge and Innovation Spaces: Learnings from Kelvin Grove Urban Village, Brisbane.” Journal of Open Innovation, Technology, Market, and Complexity 1 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40852-015-0015-7.

- Pánek, J., M. R. Glass, and L. Marek. 2020. “Evaluating a Gentrifying Neighborhood’s Changing Sense of Place Using Participatory Mapping.” Cities 102: 102. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102723.

- Pendola, R., and S. Gen. 2008. “Does “Main Street” Promote Sense of Community?: A Comparison of San Francisco Neighborhoods.” Environment and Behavior 40 (4): 545–574. doi:10.1177/0013916507301399.

- Peters, K., B. Elands, and A. Buijs. 2010. “Social Interactions in Urban Parks: Stimulating Social Cohesion?” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 9 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2009.11.003.

- Petrovic, N., T. Simpson, B. Orlove, and B. Dowd-Uribe. 2019. “Environmental and Social Dimensions of Community Gardens in East Harlem.” Landscape and Urban Planning 183: 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.10.009.

- Rajendran, L. P. 2016. “Understanding Identity and Belonging Through Incidental Spaces.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Urban Design and Planning 169 (4): 165–174. doi:10.1680/jurdp.15.00028.

- Raymond, C. M., M. Kyttä, and R. Stedman. 2017. “Sense of Place, Fast and Slow: The Potential Contributions of Affordance Theory to Sense of Place.” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (SEP). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01674.

- Relph, E. 1976. Place and Placelessness. London: Pion.

- Rostami, R., H. Lamit, S. M. Khoshnava, and R. Rostami. 2014. “The Role of Historical Persian Gardens on the Health Status of Contemporary Urban Residents: Gardens and Health Status of Contemporary Urban Residents.” EcoHealth 11 (3): 308–321. doi:10.1007/s10393-014-0939-6.

- Rostami, R., H. Lamit, S. M. Khoshnava, R. Rostami, and M. S. F. Rosley. 2015. “Sustainable Cities and the Contribution of Historical Urban Green Spaces: A Case Study of Historical Persian Gardens.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 7 (10): 13290–13316. doi:10.3390/su71013290.

- Ryan, R. L. 2005. “Exploring the Effects of Environmental Experience on Attachment to Urban Natural Areas.” Environment and Behavior 37 (1): 3–42. doi:10.1177/0013916504264147.

- Ryan, R. L., and E. Hamin. 2008. “Wildfires, Communities, and Agencies: Stakeholders’ Perceptions of Postfire Forest Restoration and Rehabilitation.” Journal of Forestry 106 (7): 370–379.

- Sabyrbekov, R., M. Dallimer, and S. Navrud. 2020. “Nature Affinity and Willingness to Pay for Urban Green Spaces in a Developing Country.” Landscape and Urban Planning 194: 194. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103700.

- Sadeghi, A. R., F. Shahvaran, A. R. Gholami, and T. Feyzabi. 2022. “Toward Behavior-Based Placemaking: The Evolution of Place Concept in Urban Design Knowledge.” International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management 7 (3): 357–372. doi:10.22034/IJHCUM.2022.03.05.

- Sancar, F. H., and Y. C. Severcan. 2010. “Children’s Places: Rural–Urban Comparisons Using Participatory Photography in the Bodrum Peninsula, Turkey.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (3): 293–324. doi:10.1080/13574809.2010.487808.

- Saymanlier, A. M., S. Kurt, and N. Ayiran. 2018. “The Place Attachment Experience Regarding the Disabled People: The Typology of Coffee Shops.” Quality & Quantity 52 (6): 2577–2596. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0678-1.

- Semenza, J. C. 2003. “The Intersection of Urban Planning, Art, and Public Health: The Sunnyside Piazza.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (9): 1439–1441. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.9.1439.

- Spartz, J. T., and B. R. Shaw. 2011. “Place Meanings Surrounding an Urban Natural Area: A Qualitative Inquiry.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (4): 344–352. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.04.002.

- Strydom, W., K. Puren, and E. Drewes 2018. “Exploring Theoretical Trends in Placemaking: Towards New Perspectives in Spatial Planning.” Journal of Place Management and Development 11 (2): 165–180

- Sun, Y., Y. Fang, E. H. K. Yung, T. Y S. Chao, and E. H. W. Chan. 2020. “Investigating the Links Between Environment and Older People’s Place Attachment in Densely Populated Urban Areas.” Landscape and Urban Planning 203. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103897.

- Tartaglia, S. 2013. “Different Predictors of Quality of Life in Urban Environment.” Social Indicators Research 113 (3): 1045–1053. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0126-5.

- Thomas, D. 2016. Placemaking: An Urban Design Methodology. Routledge.

- Thwaites, K., and I. Simkins. 2005. “Experiential Landscape Place: Exploring Experiential Potential in Neighbourhood Settings.” Urban Design International 10 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000134.

- Toolis, E. E. 2017. “Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space.” American Journal of Community Psychology 59 (1–2): 184–199. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12118.

- Tournois, L. 2018. “Liveability, Sense of Place and Behavioural Intentions: An Exploratory Investigation of the Dubai Urban Area.” Journal of Place Management and Development 11 (1): 97–114. doi:10.1108/JPMD-10-2016-0071.

- Tournois, L., and C. Rollero. 2020. ““Should I Stay or Should I Go?” Exploring the Influence of Individual Factors on Attachment, Identity and Commitment in a Post-Socialist City.” Cities 102. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102740.

- Tuan, Y.F. 1974. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Ujang, N. 2014. “Place Meaning and Significance of the Traditional Shopping District in the City Centre of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.” International Journal of Architectural Research: ArchNet-IJAR 8 (1): 66–77. doi:10.26687/archnet-ijar.v8i1.338.

- Ujang, N., and S. Shamsudin. 2012. “The Influence of Legibility on Attachment Towards the Shopping Streets of Kuala Lumpur.” Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities 20 (1): 81–92.

- Vierikko, K., P. Gonçalves, D. Haase, B. Elands, C. Ioja, M. Jaatsi, M. Pieniniemi, et al. 2020. “Biocultural Diversity (BCD) in European Cities – Interactions Between Motivations, Experiences and Environment in Public Parks.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 48: 48. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126501.

- Whalen, K. E., A. Páez, C. Bhat, M. Moniruzzaman, and R. Paleti. 2012. “T-Communities and Sense of Community in a University Town: Evidence from a Student Sample Using a Spatial Ordered-Response Model.” Urban Studies 49 (6): 1357–1376. doi:10.1177/0042098011411942.

- Wyckoff, M. 2014. Definition of Placemaking: Four Different Types. MSU Land Policy Institute. http://pznews.net/media/13f25a9fff4cf18ffff8419ffaf2815.pdf

- Yassin, H. H. 2019. “Livable city: An approach to pedestrianization through tactical urbanism.“ Alexandria Engineering Journal 58 (1): 251–259. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2019.02.005.

- Young, A. F., A. Russell, and J. R. Powers. 2004. “The Sense of Belonging to a Neighbourhood: Can It Be Measured and is It Related to Health and Well Being in Older Women?” Social Science & Medicine 59 (12): 2627–2637. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.001.

- Zadeh, F. A., and A. B. Sulaiman. 2010. “Dynamic Street Environment.” Local Environment 15 (5): 433–452. doi:10.1080/13549831003735403.

- Zhao, B., X. Huang, and D. Z. Sui. 2019. “Place Spoofing: A Case Study of the Xenophilic Copycat Community in Beijing, China.” The Professional Geographer 71 (2): 265–277. doi:10.1080/00330124.2018.1501711.