ABSTRACT

The Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2017) and the New Urban Agenda (United Nations Citation2017) emphasise the role of cities for achieving progressive, grounded, and holistic socio-environmental change. Food sharing activities, such as participation in community gardens, organic cooperatives, and urban farms and orchards, are recognised as positive urbanism transition pathways that can harbour many social, environmental, and economic co-benefits. To realise sustainable urbanism goals, the international project, EdiCitNet, applied “edible” Nature-based Solutions to facilitate societal challenges in ten participating cities. The project assumed that participatory processes across sectors within diverse cities would foster resilient project outcomes. However, while social engagement proved crucial, its implementation across diverse contexts also raised several questions regarding participants’ initial engagement and the ongoing social sustainability of the project. Analysing outcomes from the project’s first 18 months, we recognise how the type and scope of engagement can impact project implementation, highlighting how “soft” aspects such as trust, emotions, and values are crucial for the success of large-scale multi-sector projects and how aspects of power and empowerment are embedded in the process. These findings can inform the design and implementation of other sustainable urbanism projects, in addition to contributing to literature on social participation, engagement, and translocal governance.

Introduction

Cities are now at the forefront of sustainability efforts related to food to combat climate change, social inequality, and environmental degradation. Both increasing and shrinking population density impacts on space used for food within cities and at their peri-urban edges (Parham Citation2016). Cities typically produce substantial pollution and waste, affecting human life and other natural resources while also relying on massive energy, water, and food resources (Beatley Citation2012). These challenging urbanism circumstances frame work on engaging on food-centred place making.

Within this context, Nature-based Solutions (NbS) have gained attention as ways to mitigate impacts of climate change (Eggermont et al. Citation2015; Dorst et al. Citation2019; O’Sullivan, Mell, and Clement Citation2020). They are being used in a wide range of ways including to combat heat island effects (Lafortezza and Escobedo et al. Citation2018); to restore natural water flows (Albert et al. Citation2019; Frantzeskaki Citation2019) and to shape international policy, evaluation, circularity, and transition agendas (Bauduceau et al. Citation2015; Frantzeskaki et al. Citation2017; Dumitru, Frantzeskaki, and Collier Citation2020).

The urban food system is an increasingly prominent NbS focus (Lafortezza et al. Citation2018; Mino et al. Citation2021; Sartison and Artmann Citation2020; Canet-Martí et al. Citation2021). Food acts as a connector between people, place, and produce in ways that continue to be explored, such as green freeways and foodways that are used to foster social cohesion among communities, reduce air pollution, and for consumption (Houston and Zuñiga Citation2019). Such local food economies are often innovative, community-based, and context specific (Edwards and Davies Citation2018). The potential of NbS in food-related activities and services is visible in many sectors including health, diet, education, and human-nature relations (Escobedo et al. Citation2019). Mino et al. (Citation2021, 2) suggest such “edible NbS” refer “to NBS that have the purpose of food production”. We broaden this definition to account for food-related NbS along the food chain from production to waste (Bauduceau et al. Citation2015; European Commission Citation2014). ‘Edible’ NbS also have the capacity to underpin and to be enriched by engagement processes, which emphasise stakeholder participation and may include collaborative, partnership, and co-design elements (Raymond et al. Citation2017; van Ham and Klimmek Citation2017; Giordano et al. Citation2020; Butt and Dimitrijević Citation2022) as part of food systems focused participatory action research (Van Dyck et al. Citation2018).

Yet sustainable urban food and greening practices are being increasingly sidelined by global economic trade and local pressures (Davies Citation2019). Gentrification shows the need for more just distribution of green spaces to contribute to the wellbeing of all citizens (Black and Richards Citation2020; Cole et al. Citation2019). In times of crisis – as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic – the need for equitable access to both green and edible spaces is emphasised (Pulighe and Lupia Citation2020).

These requirements are explored in a developing sustainable urbanism research agenda in the context of the Anthropocene (Derickson Citation2018; Hardy Citation2019; Thomson and Newman Citation2020). Urbanism inflected approaches to food and place through NbS are being given practical expression from the hyperlocal to the supranational through food research and policy projects (Kingsley et al. Citation2021). In the Global South, basic requirements for resilience have remained foregrounded while more consumer-led, financially richer cultures of the Global North have allowed an apparent distancing to occur between food, nature, and cities (Beatley Citation2012; Freeman Citation2011). At the same time, food’s rise as a conscious focus of urban policy in the Global North since the 1990s has occurred, increasingly recognising the connections between food, urban sustainability, and planning (Morgan and Sonnino Citation2010; Pothukuchi and Kaufman Citation1999; Sonnino Citation2009).

Work linking urbanism and the food system highlights both serious problems and significant potentials for remaking urban food space in an engaged and holistic way in diverse settings and scales in the Global North and South (Knight and Riggs Citation2010; Parham Citation1990, Citation2015; Resler and Hagolani-Albov Citation2020). In edible NbS, social motivations serve as a key driver for many people, who despite different backgrounds are often engaged through gifting, growing, and sharing of food in cities (Edwards and Davies Citation2018). Engagement processes within this space are the concern of this paper. The project, EdiCitNet, is an example of an increasingly integrated understanding of food, planning, and place-making across disciplines reflected in supranational and city-based policy scales.

Introducing EdiCitNet

The five-year, European Union funded “Edible Cities Network: Integrating Edible City Solutions for Social Resilient and Sustainably Productive Cities” (EdiCitNet) project aims to solve existing and upcoming societal challenges by employing food-related NbS in cities, referred to as Edible City Solutions (ECS) (European Commission Citation2018). EdiCitNet’s structure and purpose was initially designed by a core group of researchers and practitioners into a series of Work Packages. A Consortium developed to bid for and then deliver EdiCitNet represents more than 60 stakeholders from 12 countries – ten of which are participating cities that seek to implement ECS. Participating cities are divided into two groups; Front Runner cities that aim to implement major interventions through Living Labs and Follower cities that focus on the co-creation of stakeholder developed master plans for edible NbS (Castellar et al. Citation2021). In this paper, we focus on social engagement among the Follower cities (column two in ).

Table 1. Participating cities in EdiCitNet (authors).

Participating cities are widely diverse, varying from small-scale or alternative governance structures (for example, Šempeter pri Gorici or Letchworth Garden City), to being intensively structured (some with double administrations such as Montevideo or Berlin), or completely new to urban governance (Lomé). Some cities (such as Letchworth and Berlin) have long-term involvement with ECS-related activities while others are new to the topic.

EdiCitNet governance and engagement processes

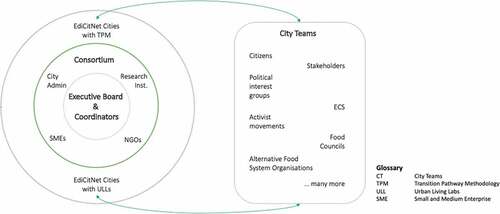

To address EdiCitNet’s governance and engagement within cities, participatory methods are embedded within the project’s core documents (the Grant Agreement), processes (termed Transition Pathway Methodology) and structures (such as the City Teams). shows the relationship between projects’ contributors: the Consortium partners, an interdisciplinary group of experts, and the City Teams, often voluntary stakeholders across government, community, business, and academic sectors who are invited to brainstorm, experiment, and reflect on possible applications of ECS (Manderscheid, Freyer, and Fiala Citation2019).

Figure 1. The structure of EdiCitNet (Maximilian Manderscheid adapted from Edwards et al. (Citation2018)).

The two most relevant work packages for this paper are Work Package One and Four (see ). Work Package One is largely responsible for setting up representative City Teams in each city, while Work Package Four led the Transition Pathway Methodology in the Follower cities. This methodology aims to integrate ECS within cities’ master plans as part of an iterative community engagement process moving from stages of system development to scenario and transfer whilst adapting the design and implementation of ECS to local contexts (Manderscheid, Freyer, and Fiala Citation2019).

Table 2. Description of purpose and key tasks of Work Packages One and Four (authors).

This paper seeks to explore the interplay between the formal structure of EdiCitNet and its informal engagement in practice. As engagement is highly localised and dependent upon voluntary commitment, several questions arise regarding the motivations, enablers, capacities, and barriers experienced by community stakeholders to be part of such a sustainable urbanism and master plan development process. In this paper, we reflect on the first 18 months of the project to identify some challenges for engaging citizens and stakeholders towards contributing to sustainable urbanism.

Methodologies

Exploring epistemologies and theories of engagement, participation, transdisciplinarity, participatory action research, and empowerment

Theories of knowledge – their epistemologies – in relation to engagement are complex. Within this theme context, engagement, participation, transdisciplinarity, and empowerment are overlapping theoretical themes that apply to ECS. These concepts emerge from a broad body of Participatory Action Research PAR literature including civil rights, community development, public health, education, sustainability studies, and transitions theory (Cornwall Citation2008; Kotus and Sowada Citation2017). These terms, often used interchangeably, can create ontological confusion: differences in both the way they are described and how they are understood. For example, engagement is often substituted for community development, participation, empowerment, involvement, mobilisation, competence, capacity, cohesiveness, and social capital (O’Mara-Eves et al. Citation2013). Participation has also been used across disciplines, often with respect to strengthening communities’ perspectives and diversifying represented expertise in decision-making processes (Mompati and Prinsen Citation2000). The World Health Organization (Citation2002, 12) defines community participation as follows:

A process by which people are enabled to become actively and genuinely involved in defining the issues of concern to them, in making decisions about factors that affect their lives, in formulating and implementing policies, in planning, developing and delivering services and in taking action to achieve change.

From the concept of participation, PAR developed the concept of participation to suggest an action oriented definition of engagement between the research and the communities as in engagement theory or transdisciplinarity. Additionally, in PAR, a moral commitment by the researchers to create action-based change engages the communities while anchoring the research at local level (Petras and Porpora Citation1993). Storey (Citation1999) notes that there has been a shift from top-down strategies in the development sector to more localised and sensitive approaches. Such approaches introduce and refine associated aspects within engagement and participatory studies that include shared values and desireability, recognition of power relations, processes of engagement, and possibilities for transformational change. PAR approaches have been used specifically in relation to food-related research, with work in participatory food systems and agroecology (Guzmán et al. Citation2013). Throughout the history of engagement, some of these terms have gained questionable conotations as the example of empowerment in the development sector shows. As Cornwall (Citation2016, 342) and others point out empowerment became a buzzword of international development, losing the transformative capacity to “confront and transform unjust unequal power relations”. Following these lines, empowerment in this research is about the recognition of existing unequal power relations and the right to fight for structural change aiming at equality (Cornwall Citation2016; Rowlands Citation1997; Cruikshank Citation1999). There is an increasing number of examples of such empowerment approaches used in relation to food systems, policy, and place-based projects (Wezel et al. Citation2018; Bornemann and Weiland Citation2019).

Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation and some of its critiques serve as an important reference for steps towards empowerment (Arnstein Citation1969; Bacqué and Gauthier Citation2017; Willness, Boakye-Danquah, and Nichols Citation2019). Post Arnstein, the participative ladder has been developed to climb from a minimal non-participative level where participants are manipulated, through to citizen control, where power is ceded by authorities to be delegated to citizens (Arnstein Citation1969; Cornwall Citation2008), to now include aspects of disorder, awakening, radicalisation, civil disobedience, and rebel action (Kotus and Sowada Citation2017).

PAR builds on critiques of Arnstein’s ladder by grounding PAR at the community level. It thus increases the potential to combine and reinforce the interests and needs of the local stakeholders and, through this, create momentum for change (Strydom and Puren Citation2014). PAR aims at community-based development including and through collaborative and applied research. As well as engagement or transdisciplinarity, PAR merges the lived experiences, the creation of knowledge, and society’s reality. Thus, communities are taken to be an active part of co-developing research and knowledge on real-world problems and meaningfully contributing to their solution. PAR offers an approach based on engaged communities, taking their perceptions into account from the outset, and enabling concrete actions (Chevalier and Buckles Citation2019).

Participation through PAR led to the topic of transdisciplinarity that has developed alongside concepts of engagement and empowerment to widen its focus on the potential participants for inclusion. Transdisciplinarity, that is, the approach to bring together scientific and practical knowledge integrating various stakeholders in the process (Klein et al. Citation2001), emerged from academia in the 1970s and was based on the recognition of the research institution’s societal responsibility for doing research with and for society. In urban studies, its epistemology has shifted from a focus on community development to centering on the increased engagement of citizens (Swaroop and Morenoff Citation2006). Transdisciplinary research aims to tackle wicked real-world problems by integrating knowledge from multiple stakeholders across different institutional levels and sectors (Jahn Citation2008). Furthermore, purely theoretical forms of transdisciplinarity have expanded to consider aspects in relation to practical implementation (Hadorn et al. Citation2008). For EdiCitNet, transdisciplinarity describes how researchers across disciplines work closely with stakeholders from diverse sectors to solve societal challenges (Klein et al. Citation2001). We perceive transdisciplinarity and participation as strengthening rather than conflictual in a participatory process approach (Jahn Citation2008). Underpinning transdisciplinarity therefore are principles of subsidiarity which may shift the power balance towards more local autonomy, where “decisions are to be taken as closely as possible to, and with the involvement of, the citizens affected by them” (Wahl Citation2017, npr). Echoing calls for multi-level governance (Edwards, Pedro, and Rocha Citation2021), subsidiarity allows for the co-creation of “locally grounded transformative innovation and widespread citizen participation” (Wahl Citation2017, npr) that can serve as a means to “transition to regenerative cultures in ways that foster health, diversity and local adaptation” (Wahl Citation2017, npr).

In this specific food engagement context, Pedro (Citation2020) argues that by adapting Ostrom’s (Citation2015) principles of the commons to food systems, that include the need for clearly defined boundaries, local contextualisation, the right to organise and more, the food system can become a forum for decision-making between all participants. As such, local decision-making in nested tiers would give preference to co-governance, scaling to broader levels only, when necessary in subsidiarity terms. Decision-making and engagement could then take the form of “guiding beside”: listening, supporting, and suggesting rather than commanding (Hocking Citation2007, 11). For a project like EdiCitNet, it is posited that in a post-Arnstein way, the goal should be to reach the level where stakeholders share resources, ideas, and energy, and have the power to contribute, criticise, and increase control over the urban planning process, so they can apply socio-spatial learning to their food-related circumstances (Natarajan Citation2017).

Methods discussion

Qualitative methods were applied to understand the dynamics of social engagement. These methods, focused on case study research (Yin Citation2009) mainly based on conducting and analysing semi structured interviews and a self-reflexive focus group style component, were chosen because of their ability to help unravel the complex social dynamics that are present in a project with overarching structures and labour arrangements, such as paid staff working with volunteers (Harcourt and Escobar Citation2002). This approach explores the interplay and relations between project participants who embody many positionalities within the project – both in formal positions and personally, as inhabitants, as individuals and as members of groups, who are from different backgrounds within widely varying socio-cultural settings. These personal experiences influence participants’ desires, expectations, and requirements of this project, which can be widely varied, where causation can be differently interpreted. The findings are divided into rough chronological order: from initial engagement in EdiCitNet, to recruiting cities, stakeholders, and City Team members, closing with the engagement processes as experienced in the Transition Pathway Methodology. Throughout this discussion, we draw out themes for further analysis.

In this research, the methods are valued for their ability to generate nuanced, in depth understanding of complex (social) situations (Alkon and Agyeman Citation2011), to uncover the subjective and lived experiences of research participants and to generate knowledge that is co-produced by research participants and researchers (Harcourt and Escobar Citation2002). By choosing a qualitative and reflexive approach where we acknowledge our relationship as members within this community that has developed over time, we have aspired to overcome potential risks of conflation of identities that can lead to misunderstandings (Beacham and Jackson Citation2022). This research used an in-depth qualitative approach, captured by the experience of the authors as project partners, further triangulated by qualitative interviews and the personal reflection of the authors in the focus groups. In this way, the paper seeks to provide a nuanced interpretation of events for numerous voices.

The primary data was drawn from six semi-structured interviews lasting 30 to 60 minutes held with City Team Coordinators and project partners supporting the City Teams from Follower cities. In addition, two structured reflection discussions – a form of focus group – were undertaken by the three authors, who represent Work Packages One and Four and a City Team Coordinator. This allowed the authors to reflect on their own observations of the project’s processes and structures. Together interviews and focus group style processes followed methodological norms for qualitative research in terms of allowing discursive, co-developed, and in-depth exploration of relevant research themes (Harcourt and Escobar Citation2002).

The interviews cover perspectives from employees of city administrations from the six Follower cities, in addition to research institutions and experts – all of whom have engaged in the Transition Pathway Methodology process. Interviews undertaken online due to the COVID-19 pandemic explored issues of motivation, drivers, and obstacles aiming to reveal how these aspects are perceived by participants and the groups they represent. As shown in recent studies from PAR, virtual interviewing was judged to be an effective strategy in terms of both rapport building and content coverage for exploring these issues in depth (Walker et al. Citation2022; Sattler et al. Citation2022). As one of the paper’s authors conducted and transcribed all the interviews, the positionality of the interviewer and the interviewees must be reflected upon for understanding the findings presented. The interviewees were (former) project partners of the EdiCitNet project and, therefore, had a professional background regarding the interview topics. The interviewer’s double role as a researcher positioned in the interview setting as outside the project activities, while also being a Work Package lead within the project, might create a field of tension that affects the interviewee’s answers. Reflecting on this positionality it is possible to argue that the interviewer and interviewee had already gained a rapport through joint project activities and this rapport could serve to create a safe space in which interviewees are more open and honest; on the other hand, the interviewee may be inhibited from reflecting critically about issues relevant to the project.

The interviewer perceived the rapport in this case as enabling open discussions and critical reflections. All three authors coded the data using the NVIVO qualitative coding program. Furthermore, all authors – representing leaders of Work Packages and a City Team – interviewed each other in a focus group setting to further distil and analyse their experiences. In the focus group discussions, the outcomes of the participatory observation and the interviews were discussed based on the personal reflections of the authors. This way insights from the Consortium Work Package level are brought together with experiences from the realities in the diverse cities (see ) and allow for triangulated reflections on project structures and labour arrangements with focus on the human aspects of such relations between volunteers, project partners, and their positionalities. Reflexively, the authors are aware that this offers only a partial view and that other stakeholders within EdiCitNet may offer different perspectives.

The next section discusses findings on themes of initial engagement; recruitment of cities, stakeholders, and City Team members; and participation in the Transition Pathway Methodology. These prefigure our analysis in terms of how these play out in practice and relate to our theoretical frame.

Findings

Initial engagement in EdiCitNet

Conceptually, the NbS and more specifically edible NbS focus of EdiCitNet were appealing to all who were involved in the bid writing process insofar as enthusiasm to take part in the Consortium can be taken as a proxy measure. The project provides a holistic approach for drawing useful connections from principle to action, along the food chain, and from an arguably utopian set of proposals to an experimental reality. Participants expressed interest in: “how far you could make use of those principles and connect them to more contemporary thinking about nature, about solutions and where that might work” (reflection discussion one). Others appreciated EdiCitNet’s holistic consideration of the food system, “looking across the food chain and connecting those loops” (reflection discussion one) in both a material and social sense.

Other interviewees expressed a desire to network across stakeholders, including and beyond food-related activities. Cities represented particularly keen sites of interest “because this is kind of the core cause of society where development or also movements are happening in such frequency or diversity” (reflection discussion one). Interviewees expressed how the project could meet their city’s criteria by sharing and receiving knowledge with other cities. For example, one stakeholder expressed how EdiCitNet could bring together: “the capacity of [the] Garden City to explore and to reflect … and to take action on nature solutions” (reflection discussion one), while others sought to extend their cities’ capacity for sustainability through food: “I really wanted to bring a city that is south of the Sahara in[to] the Consortium” (interview four). This latter interviewee expressed the desire to raise environmental standards of basic water and sewage services at home:

So here in West Africa the environment is not really taken seriously… we have no sewage system. All the people here … have no drinking water … and that’s why I thought, why not? So, first of all, to bring in [the city] and then the citizens will start to learn that hygiene, environment … are important, in order to then really develop a country or a city.

Furthermore, participants noted a connection between action research and innovation and its potential to inform both current and future city projects, expressing how: “EdiCitNet offered a platform to actually experiment and say: can we do this now? And how can we move this forward?” (reflection discussion one). In this way, EdiCitNet went beyond food movements that were often “utopian in its vision” (reflection discussion one) to “have an opportunity to see how that works on the ground” (reflection discussion one).

However, despite this potential, many participants also noted that details for achieving these goals were unclear from the project’s initiation. For example, some basic terms such as “Edible City Solution” were left undefined. The use of specialist administrative language in the core project documents, such as the Grant Agreement, had the potential to create significant obstacles when such language needed to be interpreted by many diverse stakeholders – whose native language was rarely English. This was expressed by an interviewee as: “working across the understanding of what was already written in the Grant Agreement to what was then interpreted by the Consortium to then place that within the context of the cities itself” (reflection discussion one). This use of language became frustrating when, “you’ve got people who are wanting to engage … yet they’re not even able to engage because there’s no clarity of how you are meant to engage” (reflection discussion one). Difficulties in communication and faltering engagement could further escalate when technological issues and physical distance were experienced (Manderscheid et al. Citation2022).

Other participants noted possible top-down versus bottom-up concerns where they struggled to adjust written statements from the core documents “to make sense for the different cities” (reflection discussion one), expressing: “It was a very fuzzy start in terms of knowing what was expected in the project, and then trying to meet those expectations” (reflection discussion one). Acknowledging that “there was really quite a lot of bottom-up activity going on” (reflection discussion one), they expressed how “we couldn’t just assume that we could kind of swarm in and find for the people how they were going to do things” (reflection discussion one). Hence, miscommunication represented an initial barrier to engagement and motivation.

Recruiting cities, stakeholders, and City Team members

The recruitment process for cities and staff varied across the project. For example, while formal on-boarding processes were followed for some, for others invitations were based on personal, ad hoc and informal connections. A participant described: “I still had some free capacity. And then I grew up on a farm. And it was like, “Oh, you have a little bit of a plan. You do that now” (interview two). This ad hoc approach extended at times to the project selection for ECS where, rather than create something new, some City Teams decided to strengthen pre-existing projects, seeking: “just to make it work better or to make it more visible” (interview one).

Recognising the hurdles of initiating a large-scale project, Work Packages One and Four deployed additional strategies to help recruit and establish the City Teams. This included Work Package One organising a City Team meeting to share expectations. This event was deemed a success, representing “one of the first steps for people to sort, to get their head around who else was involved and where they might go” (reflection discussion one).

While some City Teams had a positive experience of setting up their City Team as a way of pooling local expertise and developing the “topic of green, sustainable urban development and so on” (interview two); for others, a variety of factors – namely time, trust, and differing expectations – impacted their uptake. Time was a key impact on the project both with respect to a late start, significant ongoing delays throughout the project (further exacerbated by COVID-19), and unrealistic timelines to do what was required in the best way for all stakeholders.

For example, the expectation that City Teams would be established within the first six months of project was particularly demanding (EdiCitNet Citation2018). In reality, the cities experienced significantly varied levels of engagement and awareness of ECS, in addition to external pressures. As a result, time was needed to understand, select, and refine the intent and motivation of the City Teams. For many City Teams, this expectation (written into the core project documents): “Was very forced… The City Teams were meant to be very representative across different groups of society, but that didn’t actually make sense when you went to those cities in certain places” (reflection discussion one). Such dislocation between written and actual implementation raised feelings of uncertainty. A City Team Coordinator described: “We’ve got to get this team and put some names down on paper. We don’t know if they’re going to work. We haven’t had the process yet to really [know] or the grounded experience of doing it” (reflection discussion one). These examples highlight an important link between time, building relationships, and trust (Boschetti et al. Citation2016; Jagosh et al. Citation2015). As expressed by a City Team member: “You can’t make a lot of external stakeholders if you’re building relationships” (reflection discussion one) – where this is an especially difficult and unbalanced task if you are the “outsider” expecting people within a city to form a network under your leadership.

Diverging expectations of the project also became apparent through the interviews. This gap between stakeholders’ needs and expectations further impacted their willingness and ability to engage in the project. An example of conflicting perspectives included activist versus mainstream approaches. A Work Package lead noted how many food movements “are born out from a perception that something is not wrong, not right, or we want an alternative” (reflection discussion one). Alternatively, if the goal of EdiCitNet is “to mainstream these activists, and this is kind of contradicting with the … ideology of activism as such” (reflection discussion one). Such misunderstandings underlying project goals can have massive implications in transdisciplinary, cross-cultural, and multi-sectorial projects – like EdiCitNet – that can range in participation from grassroots activists to policymakers and corporate interests in cities around the world.

The generic arrangements scripted within the core project documents further emphasised this gap. On reflection, it became apparent that tensions between visions for realising desirable futures should be continuously reviewed across the project’s duration to maintain important shared understandings that underpin motivations for action. A possible alternative would be to incorporate a more bespoke approach that could recognise multiple approaches and contexts to best fit the needs of the participating cities.

Engaging in the Transition Pathway Methodology

While multiple, additional and complementing strategies were employed by Work Package One and Four to create a communication infrastructure across the project, these efforts were not always sufficient in scope, resulting in some confusion. However, the Transition Pathway Methodology was able to make some headway by inviting participants to first understand the project stages and the role of facilitation as a base for collaboration.

The Transition Pathway Methodology required a high level of participant engagement in order to transfer a sense of project ownership through the participatory process (Lang et al. Citation2012; Mittelstraß Citation2005). Effective engagement requires that project goals adapt to suit participants’ specific interests and needs. However, flexibility is limited within a project that has predefined outcomes which are conditions of its funding. Therefore, transparency of project goals and their limitations need to be openly communicated so participants are made aware of the project framework’s scope and limitations.

Furthermore, the Transition Pathway Methodology process may be perceived as cumbersome to some stakeholders who are new to such approaches. For example, the first step for applying the Transition Pathway Methodology is a facilitated conversation with each City Team to identify societal challenges in their cities. The final selection represented a negotiated outcome, in principle resulting in all participants’ equally owning the outcome. However, following such a complex process, one City Team member commented: “Okay, you present us the project, the methodology, the Transition Pathway Methodology, etcetera. But concretely, how can you help us?” (interview six) This question emphasised the need for clarity about the purpose of the process, information required for each step, its applicability, and how a sense of ownership could be conveyed.

Flexibility was highlighted as an essential characteristic for realising practical outcomes. Examples included noting seasonal events in the Global North and South, and financial considerations for the Global South where the reimbursement of project travel expenses and daily allowances were critical to ensure project participation, enabling people from all incomes to participate in project meetings and events.

With the Transition Pathway Methodology being largely a strategic planning exercise, interviews two, three, and six noted a lack in the process for providing tangible, hands-on “doing” work. Food projects in particular offer numerous layers of engagement through experiential practice and consumption (Hayes-Conroy Citation2010), which can serve as a key driver and prerequisite for engagement. One City Team lead commented: “we can invite them [members of the City Team] when we want and we can gather them when you want, but we have “to do”, to give them or to bring to them something concrete” (interview six). Indeed, one expert participant expressed early on in the project the need to engage with both “the head and the hands”. The Work Package Four lead reflected on this point:

Basically, in the beginning, there was Work Package One very nicely trying to engage people. But at that point, we at Work Package Four were not ready to guide them in this master plan process. So, they were missing a goal, … a shared task. … This was also feedback that we got … throughout the process – that there is nothing tangible, nothing that they [the participants] can touch.

The notion of “being tangible” related to practical achievements was also seen as being about progress; a sense of achievement from literally being able to sense the greening of the city. The experiential aspect of food practices can also embed many cultural, nostalgic, and societal dimensions. Such engagement can be both powerful and political: encompassing intellect, senses, emotions, and place (Edwards, Gerritsen, and Wesser Citation2021).

This lack of material, tangible output aligned with the need for clearer specific project outcomes. A Work Package lead expressed how: “One of the areas that lacked clarity was how far we were able to use EdiCitNet money to actually do things like buy infrastructure, things we might need for setting up a garden or process-related materials for working with other groups” (reflection discussion two). Such applications could have had expansive outcomes, such as “snowballing out to other groups” (reflection discussion one). Indeed, the Follower cities conveyed that, rather than write a master plan, “They wanted to actually do some things and reflect on those” (reflection discussion one).

In response to these expectations, the master plans have since been developed for some cities to implement “mini” Living Labs (experimental garden sites) to produce physical outputs alongside the Transition Pathway Methodology. While this shows flexibility in responding to expressed needs and expectations, it also raises wider governance considerations where changes in the project necessitates corresponding revisions of the project description, funding allocations, transparency, and timing of communicating opportunities to ensure that they are equitable for all.

Discussion

The start of this paper revealed participants’ desire for connection across multiple realms. Indeed, this potential to close gaps from principles to actions, along the food chain, and from a utopian to an experimental reality is one of the project’s most outstanding features. However, as the data demonstrates, limitations arose in the actual engagement of the project. This section reflects on themes that emerged from this initial 18 months of EdiCitNet, noting how greater attention would be well placed on power relations, reciprocal collaboration, volunteer engagement, and an adaptable methodology to ensure success in multi-stakeholder sustainable urbanism projects.

Exploring power relations

All engagement processes embed and express relationships of power. Power was implied or explicitly referenced in the interviews and discussion groups. This included defining the terms of the core project documents, communicating requirements, and defining and managing the input of participating cities. These reflections suggest a need to actively listen and integrate participants’ perspectives at both an early stage of the decision-making process and within core project documents. Such inclusion is in line with the presented concepts from engagement to PAR and could foster trust and an appreciation of cities’ knowledge and efforts towards securing more meaningful context-specific outcomes. This transfer of power to communities to define processes, contents, and actions finds itself in line with the notions of true empowerment defined by Cornwall (Citation2016). The need for greater horizontal exchange is expressed by a City Team member: “You’ve already made all the kind of key decisions [in the Grant Agreement and proposal writing process] and then you just want us to kind of go along with what’s supposed to be the output for master planning” (reflection discussion one).

Developing reciprocal collaboration

Successful collaboration is about dialogue, mutual learning, and reciprocity tackling wicked real-world problems as defined in the concept of transdisciplinarity (Jahn Citation2008). Challenges emerging from the data included a sense of distance between international experts from the locally supporting project partners and Work Package leads and local knowledge from the City Team members. One City Team member commented on feeling “a little bit like a cow being milked” (interview two), due to the volume of administrative requirements, including taking part in surveys, writing reports, posting online, attending meetings, that could be experienced as predominantly one-way. These patterns of unequal participation have been unravelled by Arnstein and the post-Arnstein critiques, instead offering more partnership or stakeholder-controlled approaches, in this case within a food research setting (Arnstein Citation1969; Willness, Boakye-Danquah, and Nichols Citation2019). Rather than being equal participants who felt supported by the Consortium, City Team members expressed how: “Actually we thought we’d be cities do[ing] something and they should help us with it … not the other way round” (interview two). The need to recognise specific Follower cities’ stakeholders’ needs and desires also related to scale where participants from smaller cities were expected to contribute more than larger cities as they were: “asking a lot of things to the same people all the time” (interview five).

Engaging through volunteerism

There are unique challenges in structuring projects around volunteerism. Both City Teams and the Transition Pathway Methodology relied on continued engagement through volunteer action. Due to the funding structure of the project, only one person (typically from the municipality) was paid for their work, while the members of the City Teams and community participants of ECS were expected to volunteer their time to attend meetings and to contribute to activities and outputs. Respondents recognise how “EdiCitNet is based on the shoulders of volunteer engagement of people” (reflection discussion one). Indeed, the structure and delivery of the project relied on this invisible work, where – as this discussion shows – this “level of commitment was beyond what we could expect from volunteers” (interview one). A Work Package lead recognised how in this context, enthusiasm for the project was essential for participation: “If you’re going to have unpaid volunteers doing stuff and rely and put so much pressure on them to do stuff, they’re not going to want to do it unless there’s an enthusiasm that carries them through” (reflection discussion one). Volunteers are enthusiastic about the potential for local action and development of communities and this reflects the aspects of empowerment in the concepts of engagement, participation and PAR that in turn support research and action directly benefitting local communities (Petras and Porpora Citation1993; Strydom and Puren Citation2014).

Furthermore, volunteer efforts often encompass emotional labour by both paid staff and volunteers. For both, there is the responsibility of bringing something into action: “If you can’t get these people to engage, your whole city project is going to fall over” (reflection discussion one). As Gajpari (Citation2017) points out, capitalising rapport in research risks an exploitative approach to emotional labour. This pattern can often be found in projects with volunteerism aspects. Indeed, the extent of such unpaid efforts must be recognised and supported, both for ethical reasons and more instrumentally because volunteer disenchantment can threaten the survival of the project overall: “I think, again, that needs to be sort of recognised … that we had this huge superstructure on a very fragile basis, which depended on the goodwill and the good work of people who are in the City Team” (reflection discussion one). These concerns suggest that framing a PAR project predominantly on volunteerism requires additional engagement effort and strategies, as well as practicalities. For example, among participating African cities interviewees noted that it is unusual for people to volunteer without covering their cost for attendance: “nobody would show up if you don’t pay their transport” (reflection discussion one).

Fitting an open methodology within a closed project structure

The interview results provoke the questions: how can an open and dynamic engagement process be anchored within a PAR project with largely pre-planned structure and goals? How does this align with engaging participants from diverse real world circumstances? How can rigid, large-scale projects be adapted to change? These questions further compound when expectations of outcomes hinge upon voluntary participation – especially when those in managerial roles will receive funding for their work. It also suggests that sensitivity in terms of trust, timing, representation, an alignment of expectations, management, and communication needs to adapt to local circumstances while meeting the project goals and structure. This sentiment was well-expressed by a City Team Coordinator as a “cognitive dissonance”:

On the one hand you’re telling them how much you want to engage and how, you know, they’ve got a controlling aspect to this. … but the reality that they can see in front of them is that structurally it’s organised instrumentally. They do what they’re told. It’s within … decisions already been made about what they’re doing, about outputs, about everything. So, they can see there’s a gap between rich truth and reality. At the same time, they’re aware that [they are] unpaid, they are expected to carry the whole project. You know, you really, in a sense, [are] setting them up to feel annoyed by that and potentially to fail.

Such reflections highlight the importance of respect, reciprocity, and inclusion in engaging on large-scale, multi-sector PAR food projects over time.

Final thoughts

This paper based on participants’ insights into an international NbS project demonstrates the challenges and complexities of developing effective engagement in terms of both structure and process. Complexity is something that should be acknowledged and explored to learn from experience – from concept to implementation – to foster new ways of living in just and sustainable cities. Due to the project’s origin and structure, while many positive connections were made, participants particularly focused on the desire for more clarity and interconnections between different parts of the project. During the initial project phase, participants demonstrated different interpretations of the project goals and engagement processes both on a conceptual and an applied. This emphasises the need for clarity and reflexivity about project goals and definitions, time and trust to build capacity to work together on a local basis and align expectations on working methods and outcomes. The trick then is to recognise key junctures where it is useful to reflect and learn from these engagement challenges and to make project adjustments as needed. Key conclusions on structure and process are summarised in .

Table 3. Key learnings for engagement from the first phase of EdiCitNet (authors).

By identifying learning areas, strategies can be deployed to effectively manage engagement on the one side and experience it as an active participant on the other. Some such solutions can be both simple and immediate. For example, one City Team lead expressed the importance of making people feel valued throughout the project: “Valuing individuals and individual initiatives and demonstrating that these individual initiatives can be important in local planning … every time an individual has a project, we go to visit … and every visit adds a bit of value” (interview six).

The discussion of findings suggests that it is within the field of power relations where most risk coalesces in engagement processes, so it is in this arena where lessons may be most critical. The data explored here demonstrate that equal representation and inclusion can open doors for new voices and support for innovative ECS actions in diverse locations. The data reveals that power relations can emerge and be dealt with at a number of junctures within a project’s development and delivery. This includes the writing and structure of the project proposal, the work between any core working group and city-level coordinators, and the establishment of clarity about and reasonable level of expectations and reliance on volunteers. Such initiatives clearly need to be aware of potential implications emerging from framing an open engagement process within a closed project structure. Approaches such as subsidiarity and the food commons offer potential pathways to return power to the local level whilst promoting greater horizontal consensus between stakeholders to reach shared goals.

Other themes raised during this research that could not be included within the scope of this paper included the importance of sharing positive ECS experiences from other projects and the role of municipal actors as lynch pins between grassroots perspectives and Consortium directives. Practical discussions also need to be held regarding how to engage new cities in such projects and networks without funding support, while the differences in cultural interpretation to the process and the scope ECS warrant further research.

Conclusion

Large-scale and complex engagement projects on food such as EdiCitNet stand to offer many pathways forward for achieving Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations Citation2017) and goals in the New Urban Agenda (United Nations Citation2017). However, this paper demonstrates that the “soft” matter of people, trust, emotions, and values play a crucial role in their initial and ongoing engagement towards achieving these aims. This paper describes the project’s participatory processes, City Teams and the Transition Pathway Methodology, to learn from their experience. Drawing on insights from a range of participants in diverse geographic locations, this paper reveals the rich fabric of social engagement which is crucial for the EdiCitNet project’s success. Acknowledging the EdiCitNet project’s embedded structural and process implications that are particularly framed around power relations has demonstrated how issues of trust, emotions, and values are crucial to success. Effective engagement clearly poses serious challenges, but the aim must be to maximise stakeholder trust and motivations for engagement in future schemes. This should facilitate a diversity of voices to be heard within PAR and ensure opportunities for innovative action can be shared with others. By unpicking power relations within participatory processes, this paper learns from and extends understandings of social participation, engagement, and urban governance within sustainable urbanism and transition literatures.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the finalisation of the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge that this work was supported by the Horizon 2020 EdiCitNet project [EU grant agreement No. 77666]. The authors would like to thank all the interviewees for their insights in this paper.

Disclosure statement

A co-author is an editor of the Journal of Urbanism.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albert, C., B. Schröter, D. Haase, M. Brillinger, J. Henze, S. Herrmann, S. Gottwald, P. Guerrero, C. Nicolas, and B. Matzdorf. 2019. “Addressing Societal Challenges Through Nature-Based Solutions: How Can Landscape Planning and Governance Research Contribute?” Landscape and Urban Planning 182: 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.10.003.

- Alkon, A. H., and J. Agyeman, Eds. 2011. Cultivating Food Justice: Race, Class, and Sustainability. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/8922.001.0001.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bacqué, M. H., and M. Gauthier. 2017. “Participation, Urban Planning, and Urban Studies.” In Chapter 3 in Dialogues in Urban and Regional Planning 6, edited by C. Silver, R. Freestone, and C. Demaziere, 49–80. New York and London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315628127-4.

- Bauduceau, N., P. Berry, C. Cecchi, T. Elmqvist, M. Fernandez, T. Hartig, W. Krull, et al. 2015. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities: Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

- Beacham, J., and P. Jackson. 2022. “An Appetite for Change? Engaging the Public in Food Policy and Politics.” Consumption and Society 1 (2): 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1332/KENJ3889.

- Beatley, T. 2012. “Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities.” Island Press, no. 2011. https://doi.org/10.22269/110418.

- Black, K. J., and M. Richards. 2020. “Eco-Gentrification and Who Benefits from Urban Green Amenities: Nyc’s High Line.” Landscape and Urban Planning 204: 103900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103900.

- Bornemann, B., and S. Weiland. 2019. “Empowering People—Democratising the Food System? Exploring the Democratic Potential of Food-Related Empowerment Forms.” Politics & Governance 7 (4): 105–118. doi:10.1764/5pag/v7i4.2190.

- Boschetti, F., C. Cvitanovic, A. Fleming, and E. Fulton. 2016. “A Call for Empirically Based Guidelines for Building Trust Among Stakeholders in Environmental Sustainability Projects.” Sustainability Science 11 (5): 855–859. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0382-4.

- Butt, A. N., and B. Dimitrijević. 2022. “Multidisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Collaboration in Nature-Based Design of Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism.” Sustainability 14 (16): 10339. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610339.

- Canet-Martí, A., R. Pineda-Martos, R. Junge, K. Bohn, T. A. Paço, C. Delgado, G. Alenčikienė, S. L. Gangenes Skar, and G. F. M. Baganz. 2021. “Nature-Based Solutions for Agriculture in Circular Cities: Challenges, Gaps, and Opportunities.” Water 13 (18): 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13182565.

- Castellar, J. A., L. A. Popartan, J. Pueyo-Ros, N. Atanasova, G. Langergraber, L. Corominas Säumel, J. Comas, and V. Acuna. 2021. “Nature-Based Solutions in the Urban Context: Terminology, Classification and Scoring for Urban Challenges and Ecosystem Services.” The Science of the Total Environment 779: 146237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146237.

- Chevalier, J. M., and D. J. Buckles. 2019. “Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry.” 1–434. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351033268

- Cole, H. V. S., M. Triguero-Mas, J. T. Connolly, and I. Anguelovski. 2019. “Determining the Health Benefits of Green Space: Does Gentrification Matter?” Health & Place 57: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.02.001.

- Cornwall, A. 2008. “Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, Meanings and Practices.” Community Development Journal 43 (3): 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn010.

- Cornwall, A. 2016. “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?” Journal of International Development 28 (3): 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/JID.3210.

- Cruikshank, B. 1999. The Will to Empower: Democratic Citizens and Other Subjects. Cornell University Press. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501733918.

- Davies, A. R. 2019. Urban Food Sharing Rules, tools and networks Bristol and Chicago: Policy Press. 124. http://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25248.

- Derickson, K. D. 2018. “Urban Geography III: Anthropocene Urbanism.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (3): 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516686012.

- Dorst, H., A. van der Jagt, R. Raven, and H. Runhaar. 2019. “Urban Greening Through Nature-Based Solutions – Key Characteristics of an Emerging Concept.” Sustainable Cities and Society 49: 101620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101620.

- Dumitru, A., N. Frantzeskaki, and M. Collier. 2020. “Identifying Principles for the Design of Robust Impact Evaluation Frameworks for Nature-Based Solutions in Cities.” Environmental Science & Policy 112: 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.05.024.

- EdiCitNet. 2018. “Grant Agreement ID: 776665.” EdiCitNet, EU H2020 IA Project. Available at:https://doi.org/10.3030/776665.

- Edwards, F., and A. R. Davies. 2018. “Connective Consumptions: Mapping Melbourne’s Food Sharing Ecosystem.” Urban Policy & Research 36 (4): 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2018.1476231.

- Edwards, F., R. Gerritsen, and G. Wesser. 2021. “The ‘Food, Senses and the city’ Nexus.”Food, Senses and the City,In F. Edwards, R. Gerritsen, and G. Wesser, 1–26. Routledge:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003025580-1

- Edwards, F., N. Pachova, S. Reddy, T. Wachtel, I. Säumel, and L. Kosack 2018. EdiCitnet Governance Approach and Guidelines Report EdiCitNet, EU H2020 IA Project. https://zenodo.org/record/3675145

- Edwards, F., S. Pedro, and S. Rocha. 2021. “Institutionalising Degrowth? Exploring Multi-Level Food Governance.” In Food for Degrowth: Perspectives and Practices, edited by A. Nelson and F. Edwards. 141–155. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003004820-14.

- Eggermont, H., E. Balian, J. M. N. Azevedo, V. Beumer, T. Brodin, J. Claudet, B. Fady, et al. 2015. “Nature-Based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe.” GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 24 (4): 243–248. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.24.4.9.

- Escobedo, F. J., V. Giannico, C. Y. Jim, G. Sanesi, and R. Lafortezza. 2019. “Urban Forests, Ecosystem Services, Green Infrastructure and Nature-Based Solutions: Nexus or Evolving Metaphors?” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 37: 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.02.011.

- European Commission. 2014. Nature-Based Solutions. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/research-area/environment/nature-based-solutions_en.

- European Commission. 2018. “Edible Cities Network Integrating Edible City Solutions for Social Resilient and Sustainably Productive Cities.” Available at:https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/776665.

- Frantzeskaki, N. 2019. “Seven Lessons for Planning Nature-Based Solutions in Cities.” Environmental Science & Policy 93: 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.033.

- Frantzeskaki, N., S. Borgström, L. Gorissen, M. Egermann, and F. Ehnert. 2017. “Nature-Based Solutions Accelerating Urban Sustainability Transitions in Cities: Lessons from Dresden, Genk and Stockholm Cities.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by N. Kabisch, H. Korn, J. Stadler, and A. Bonn, 65–88. Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_5.

- Freeman, C. 2011. “Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 13 (3): 322–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2011.603198.

- Gajparia, J. 2017. “Capitalising on Rapport, Emotional Labour and Colluding with the Neoliberal Academy.” Women’s Studies International Forum 61: 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2016.10.015.

- Giordano, R., I. Pluchinotta, A. Pagano, A. Scrieciu, and F. Nanu. 2020. “Enhancing Nature-Based Solutions Acceptance Through Stakeholders’ Engagement in Co-Benefits Identification and Trade-Offs Analysis.” The Science of the Total Environment 713: 136552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136552.

- Guzmán, G. I., D. López, L. Román, and A. M. Alonso. 2013. “Participatory Action Research in Agroecology: Building Local Organic Food Networks in Spain.” Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 37 (1): 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.718997.

- Hadorn, G. H., S. Biber-Klemm, W. Grossenbacher-Mansuy, H. Hoffmann-Riem, D. Joye, C. Pohl, U. Wiesmann, and E. Zemp. 2008. “The Emergence of Transdisciplinarity as a Form of Research.” In Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research, edited by G. H. Hadorn, H. Hoffmann-Riem, S. Biber-Klemm, W. Grossenbacher-Mansuy, D. Joye, C. Pohl, U. Wiesmann, and E. Zemp, 19–39. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6699-3_2.

- Harcourt, W., and A. Escobar. 2002. “Women and the Politics of Place.” Development (Basingstoke) 45 (1): 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1110308.

- Hardy, M. 2019. “Urban Growth.” In A Research Agenda for New Urbanism, edited by E. Talen, 124–138. Cheltenham, UK, and Northamptom, USA: Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788118637.00013.

- Hayes-Conroy, A. 2010. “Feeling Slow Food: Visceral Fieldwork and Empathetic Research Relations in the Alternative Food Movement.” Geoforum 41 (5): 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.04.005.

- Hocking, C. 2007. “The Guide Beside Project: Comprehensive and Effective Professional Development for Facilitators of Sustainability.” Eingana 30 (3): 11–15.

- Houston, D., and M. E. Zuñiga. 2019. “Put a Park on It: How Freeway Caps are Reconnecting and Greening Divided Cities.” Cities 85: 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.08.007.

- Jagosh, J., P. L. Bush, J. Salsberg, A. C. Macaulay, T. Greenhalgh, G. Wong, M. Cargo, L. W. Green, C. P. Herbert, and P. Pluye. 2015. “A Realist Evaluation of Community-Based Participatory Research: Partnership Synergy, Trust Building and Related Ripple Effects.” BMC Public Health 15 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1.

- Jahn, T. 2008. “Transdisciplinarity in the Practice of Research.” In Transdisziplinäre Forschung: Integrative Forschungsprozesse Verstehen und Bewerten, edited by M. Bergmann and E. Schramm, 21–37. Frankfurt and New York: Campus Verlag.

- Kingsley, J., M. Egerer, S. Nuttman, L. Keniger, P. Pettitt, N. Frantzeskaki, T. Gray, et al. 2021. “Urban Agriculture as a Nature-Based Solution to Address Socio-Ecological Challenges in Australian Cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 60: 127059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127059.

- Klein, J. T., W. Grossenbacher-Mansuy, R. Haberli, A. Bill, R. W. Scholz, and M. Welti. 2001. “Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving Among Science, Technology, and Society. An Effective Way for Managing Complexity.” In Transdisciplinarity: Joint Problem Solving among Science, Technology, and Society. Proceedings of the International Transdisciplinarity 2000 Conference; Zurich: Haffmans Sachbuch Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-8419-8.

- Knight, L., and W. Riggs. 2010. “Nourishing Urbanism: A Case for a New Urban Paradigm.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 8 (1–2): 116–126. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2009.0478.

- Kotus, J., and T. Sowada. 2017. “Behavioural Model of Collaborative Urban Management: Extending the Concept of Arnstein’s Ladder.” Cities 65: 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.02.009.

- Lafortezza, R., J. Chen, C. K. Van Den Bosch, and T. B. Randrup. 2018. “Nature-Based Solutions for Resilient Landscapes and Cities.” Environmental Research 165: 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.038.

- Lang, D. J., A. Wiek, M. Bergmann, M. Stauffacher, P. Martens, P. Moll, M. Swilling, and C. J. Thomas. 2012. “Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice, Principles, and Challenges.” Sustainability Science 7 (1): 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x.

- Manderscheid, M., V. Fiala, F. Edwards, B. Freyer, and I. Säumel. 2022. “Let’s Do It Online?! Challenges and Lessons for Inclusive Virtual Participation.” Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, Participatory Action Research in a Time of Covid and Beyond 6 (May): 188. https://doi.org/10.3389/FSUFS.2022.732943.

- Manderscheid, M., B. Freyer, and V. Fiala. 2019. D4.1 - Adapted Transition Pathway Methodology. EdiCitNet. https://zenodo.org/record/3607932.

- Mino, E., J. Pueyo-Ros, M. Škerjanec, J. A. C. Castellar, A. Viljoen, D. Istenič, N. Atanasova, K. Bohn, and J. Comas. 2021. “Tools for Edible Cities: A Review of Tools for Planning and Assessing Edible Nature-Based Solutions.” Water 13 (17): 2366. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13172366.

- Mittelstraß, J. 2005. “Methodische Transdisziplinarität. TATuP-Zeitschrift für Technikfolgenabschätzung.” Theorie und Praxis 14 (2): 18–23. https://doi.org/10.14512/tatup.14.2.18.

- Mompati, T., and G. Prinsen. 2000. “Ethnicity and Participatory Development Methods in Botswana: Some Participants are to Be Seen and Not Heard.” Development in Practice 10 (5): 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520020008805.

- Morgan, K., and R. Sonnino. 2010. “The Urban Foodscape: World Cities and the New Food Equation.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy & Society 3 (2): 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq007.

- Natarajan, L. 2017. “Socio-Spatial Learning: A Case Study of Community Knowledge in Participatory Spatial Planning.” Progress in Planning 111: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2015.06.002.

- O’Mara-Eves, A., G. Brunton, G. McDaid, S. Oliver, J. Kavanagh, F. Jamal, T. Matosevic, A. Harden, and J. Thomas. 2013. “Community Engagement to Reduce Inequalities in Health: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Economic Analysis.” Public Health Research, No. 1.4. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library. November. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr01040.

- Ostrom, E. 2015. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316423936.

- O’Sullivan, F., I. Mell, and S. Clement. 2020. “Novel Solutions or Rebranded Approaches: Evaluating the Use of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) in Europe.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 2: 27, November: 572527. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2020.572527.

- Parham, S. 1990. “The Table in Space: A Planning Perspective.” Meanjin 49: 2 (2): 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.1990.9657461.

- Parham, S. 2015. Food and Urbanism: The Convivial City and a Sustainable Future. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Parham, S. 2016. “Shrinking Cities and Food: Place-Making for Renewal, Reuse and Retrofit.” In Future Directions for the European Shrinking City, edited by W. J. V. Neill and H. Schlappa, RTPI Library Series, 95–113 18. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pedro, S. 2020. “Food Governance: Multistakeholder and Multilevel Food Councils.” In Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, edited by W. Leal, 1–9. Volume 2. Zero Hunger. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-2599-9.ch004.

- Petras, E. M. L., and D.v. Porpora. 1993. “Participatory Research: Three Models and an Analysis.” The American Sociologist 24 (1): 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02691948.

- Pothukuchi, K., and J. L. Kaufman. 1999. “Placing the Food System on the Urban Agenda: The Role of Municipal Institutions in Food Systems Planning.” Agriculture and Human Values 16 (2): 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007558805953.

- Pulighe, G., and F. Lupia. 2020. “Food First: COVID-19 Outbreak and Cities Lockdown a Booster for a Wider Vision on Urban Agriculture.” Sustainability 12 (12): 5012. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125012.

- Raymond, C. M., N. Frantzeskaki, N. Kabisch, P. Berry, M. Breil, M. R. Nita, D. Geneletti, and C. Calfapietra. 2017. “A Framework for Assessing and Implementing the Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas.” Environmental Science & Policy 77: 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.008.

- Resler, M. L., and S. E. Hagolani-Albov. 2020. “Augmenting Agroecological Urbanism: The Intersection of Food Sovereignty and Food Democracy.” Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (3): 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2020.1811829.

- Rowlands, J. 1997. Questioning Empowerment: Working with Women in Honduras. Oxfam Publishing: Oxford. https://doi.org/10.3362/9780855988364.

- Sartison, K., and M. Artmann. 2020. “Edible Cities – an Innovative Nature-Based Solution for Urban Sustainability Transformation? An Explorative Study of Urban Food Production in German Cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 49: 126604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126604.

- Sattler, C., J. Rommel, C. Chen, M. García-Llorente, I. Gutiérrez-Briceño, K. Prager, M. F. Reyes, et al. 2022. “Participatory Research in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: Adjusting Your Methodological Toolkits.” One Earth 5 (1): 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ONEEAR.2021.12.006.

- Sonnino, R. 2009. “Feeding the City: Towards a New Research and Planning Agenda.” International Planning Studies 14 (4): 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563471003642795.

- Storey, D. 1999. “Issues of Integration, Participation and Empowerment in Rural Development: The Case of LEADER in the Republic of Ireland.” Journal of Rural Studies 15 (3): 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(98)00073-4.

- Strydom, W. J., and K. Puren. 2014. “From Space to Place in Urban Planning: Facilitating Change Through Participatory Action Research.” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 191. https://doi.org/10.2495/SC140391.

- Swaroop, S., and J. D. Morenoff. 2006. “Building Community: The Neighborhood Context of Social Organization.” Social Forces 84 (3): 1665–1695. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0058.

- Thomson, G., and P. Newman. 2020. “Cities and the Anthropocene: Urban Governance for the New Era of Regenerative Cities.” Urban Studies 57 (7): 1502–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018779769.

- United Nations. (2017). The 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. United Nations. Quito, Ecuador. Retrieved May 30, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Van Dyck, B., A. Vankeerberghen, E. Massart, N. Maughan, and M. Visser. 2018. “Institutionalization of Participatory Food System Research: Encouraging Reflexivity and Collective Relational Learning.” Agroecología 13 (1): 21–32.

- van Ham, C., and H. Klimmek. 2017. “Partnerships for Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas –Showcasing Successful Examples.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by N. Kabisch, H. Korn, J. Stadler, and A. Bonn, 275–289. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_16.

- Wahl, D. C. 2017. “Redesigning Agriculture for Food Sovereignty and Subsidiarity.” Medium Available at: https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/redesigning-agriculture-for-food-sovereignty-and-subsidiarity-ebf7e5f03662.

- Walker, A. P. P., N. Sanga, O. G. Benson, M. Yoshihama, and I. Routté. 2022. “Participatory Action Research in Times of Coronavirus Disease 2019: Adapting Approaches with Refugee-Led Community-Based Organizations.” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, & Action 16 (2): 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1353/CPR.2022.0040.

- Wezel, A., J. Goette, E. Lagneaux, G. Passuello, E. Reisman, C. Rodier, and G. Turpin. 2018. “Agroecology in Europe: Research, Education, Collective Action Networks, and Alternative Food Systems.” Sustainability 10 (4): 1214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041214.

- Willness, C., J. Boakye-Danquah, and D. Nichols. 2019. “How Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation Can Enhance Community Engaged Teaching and Learning.” Academy of Management Proceedings 1: 18618. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2020.0284.

- World Health Organization. 2002. Community Participation in Local Health and Sustainable Development: Approaches and Techniques. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/publications/2002/community-participation-in-local-health-and-sustainable-development.-approaches-and-techniques.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th edn ed. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage Publications.