Abstract

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights enshrines the right to freedom of opinion and expression. UN Resolution A/RES/61/266 called upon Member States “to promote the preservation and protection of all languages used by peoples of the world”. This resolution has particular relevance for minority language groups where mother tongue – so vital to self-expression – is primarily a spoken medium, often ascribed low status. With few fluent readers and writers, and a consequent dearth of written resources, a vicious circle develops and linguistic and cultural heritage erodes. Not all governments are vigilant with appropriate policies and funding. Even in a community like Shetland, where there is no class connotation associated with speaking Shetlandic, the proportion of fluent dialect speakers is now relatively small. It therefore falls to the writer to create resources for children, to help stem the tide. Engaging in translation can also help raise the status of dialect and pinpoint the somewhat arbitrary distinction between dialect and language. There are many problems in publishing in minority tongues; for example, uneconomic print runs, language authenticity versus contemporaneity, standardisation of orthography and the trend to “exotic-ise” dialect in mainstream literature.

Mother tongue as a universal human right

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) enshrines the right to freedom of opinion and expression. UN Resolution A/RES/61/266 called upon Member States “to promote the preservation and protection of all languages used by peoples of the world” (United Nations, Citation2007, p. 4). This resolution has particular relevance for minority language groups where mother tongue is primarily a spoken medium, often ascribed low status. UNESCO (Citation2017) states “Local languages, especially minority and indigenous, transmit cultures, values and traditional knowledge, thus playing an important role in promoting sustainable futures.” (n.p.)

Not only does the recognition of the value of one’s mother tongue help develop a sense of pride in it, it can help promote an attitude of mind towards other cultures and tongues, as being due a reciprocal respect. The United Nations also states

All moves to promote the dissemination of mother tongues will serve not only to encourage linguistic diversity and multilingual education but also to develop fuller awareness of linguistic and cultural traditions throughout the world and to inspire solidarity based on understanding, tolerance and dialogue. (United Nations, Citation2017, n.p.)

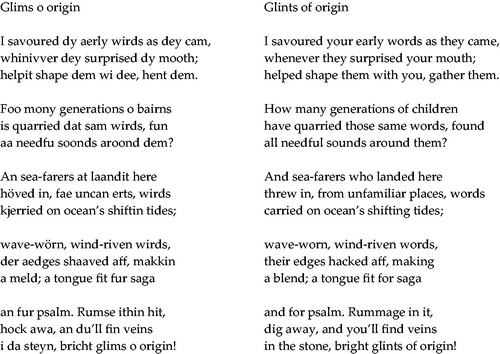

Early exposure to mother tongue as well as the official language can be part of this development of empathy before formal educations begins. I was brought up in one such minority tongue area – Shetland, the most northerly island group in the United Kingdom. I write as a poet, and in this commentary, I will use poetry “through any media and regardless of frontiers” (Article 19, United Nations, Citation1948), to argue for mother tongue as a universal human right. This short poem in Shetlandic (or Shetland dialect), Glims o origin (De Luca, Citation2005a), revels in mother tongue and the delight in teaching it to one’s child. It also touches on the evolution and attrition of language. An English version is added ().

Figure 1. Glims o origin (De Luca, Citation2005a). Reprinted with permission.

If, when a child starts formal education, that initial language resource (this human right) is ignored or – more damaging – treated as an inferior dialect, children quickly sense these value judgements. This is particularly problematic in areas with small language groups and/or where there is a sudden or relatively large influx of people speaking the dominant tongue.

Discussions of what constitutes “language” and “dialect” may be convoluted but, while they go on, those classified as languages generally get increased official support while those treated as dialects can tend to wither, lacking the status and funding associated with “language”.

I consider myself lucky to have been brought up in a bilingual environment, with Shetlandic a vibrant dialect and English as our official language. We moved effortlessly between the two, depending on the situation. In rural Shetland at that time (mid-twentieth century), the local linguistic resource was rich and it was necessary to ensure children were secure in their English so that they would not be at a disadvantage later in life, especially as many left the islands for higher education or employment. Generally, English was taught as a necessary communication skill, with a valuable associated literary tradition; it was not taught in a way that encouraged emulation of a linguistic élite, or a feeling of inferiority of our dialect expression. We were not, for example, encouraged to have elocution lessons; and indeed, had we started speaking formal English in informal situations, we would have been accused of knappin – a dialect verb with a real pejorative feel (i.e. to speak with affectation).

We were lucky that, generally speaking, our mother tongue was not considered to be inferior and, as part of our education – though reading and writing were not taught formally – we had occasional opportunities to learn to recite poems in Shetlandic. No local concert was complete without some Shetland poetry and perhaps a sketch in dialect. This was particularly the case in rural areas. And there were good models we could emulate: teachers who were fluent and comfortable in both Shetlandic and English.

I was therefore surprised when I moved to the Scottish mainland to find that not all communities had that attitude to their mother tongue. Many seemed trapped in a single way of speaking, either in English or in Scots (which varies somewhat from one area to another, particularly in accent). To me, for the first time, language appeared to be used as a strong indicator of class; and the concomitant sense of betraying one’s class by being willing and able to shift with ease between the two. I had not experienced this in Shetland.

Shetlandic was, for most people, an oral culture. We rarely had an opportunity to learn to read and write in our mother tongue. The islands were therefore not well prepared for the economic shock that the discovery of North Sea Oil brought in the 1970s, and the sudden relatively large numbers of incomers. Even when teachers were keen to do something to support dialect, there were few suitable resources and no mother tongue storybooks. School playgrounds, and even the school gate, suddenly became places where, noticeably, the language became English. Parents who were fluent dialect speakers started speaking English to their children presumably to boost the self-confidence of their children when surrounded by non-Shetlandic-speaking classmates and sometimes teachers too. Dialect-speaking – particularly with young people – became less common and less valued. The human right we had taken for granted was endangered as, in a policy vacuum, many parents failed to appreciate just how important is that inter-generational mother tongue conversation.

Through the work of a voluntary body, Shetland ForWirds, established in 2009, much work has since been undertaken to support schools to stem the tide, to raise confidence and to create resources. Policy-makers eventually followed suit. Teachers are now encouraged to make opportunities for children to read and write in Shetlandic. However, time in the curriculum is tight and many teachers, though willing, lack the necessary fluency and literacy.

One important support for raising or maintaining the status of dialect in such situations is the existence of an expanding contemporary literature for children and adults. This seems to be crucial in ensuring that speakers of the dialect can feel a real sense of identity and pride when using it for their various communications, whether in a literary context or informally. In relation to adults, Shetland has a relatively small literature on which to build, starting from the early nineteenth century. Since 1947 this has been nurtured by the quarterly journal The New Shetlander, (Voluntary Action Shetland, Citation2017) a valuable organ for publishing stories and poems in Shetlandic, as well as cultural articles. It has recently made a real effort to publish dialect writing by young people.

Many bemoan the current state of dialect speaking and writing but Brian Smith, co-editor of The New Shetlander and the local archivist, remarked in an article about Shetland dialect (Smith, Citation2000)

The key evidence that Shetland dialect is in good, challenging form is its literature. That growing body of work reflects and portrays modern Shetland. And it doesn’t just reflect it; it alters the way Shetlanders speak to each other about the world and its travails.

These are encouraging words. Looking to the future, what will help sustain Shetland dialect? It is still spoken fairly widely, particularly by the older generation. But as long as schools teach only in the medium of English and have dialect merely as an extra – when time allows – it will be difficult to raise levels of literacy and consequently hard to encourage a new generation of writers. However, it’s not all bleak: the emergent use of dialect on social media is perhaps helping younger people gain confidence in literacy. And the good work of Shetland ForWirds continues with competitions for young writers.

However, for writers, finding a publisher outwith Shetland for such a minority tongue is never easy. Yet this is an important signifier of the status of the dialect within the country, and worth pursuing. Writers in minority tongues often have to make compromises if they want to be published: for example reducing the proportion of Shetlandic to English poems in a collection; or the commercially more viable “Shetlandic-light” route (i.e. poems in English with just a soupçon of Shetland words).

In terms of an expanding literature there are several issues:

The cost of producing children’s storybooks – designed to look as exciting and colourful as those written in English – is very high. Publishing small print runs is generally not financially viable. It requires subsidy.

Natural language attrition (words becoming obsolete) over the years as a by-product of economic change can result in what is an authentic tongue to older readers feeling somewhat archaic to younger readers.

Variation (not untypical) across the islands in pronunciation. While this demonstrates linguistic vitality it is apt to make it more difficult to settle on orthography. Vowel sounds in particular can vary considerably from one community to another. However, readers impose their own pronunciation, irrespective of the writer’s spelling. The question is therefore, given the need to increase literacy levels for the future, can we trade a bit of authentic sound for consistency and ease of reading? There are several dictionaries, for example Graham (Citation1979), and a grammar (Robertson & Graham, Citation1952), which support in this area.

There is a modern trend, possibly as writers in the western world travel ever more widely to more inaccessible places, to treat minority tongues as exotica; vocabulary as cultural artefacts which can add a certain piquancy to their own creative writing. I would argue that when the dialect borrowed is spoken by a very small language group and is endangered for whatever reason (and there are many), and then, there is a responsibility to examine one’s motives for so doing. If it is necessary to the meaning of the poem (e.g. there is no direct equivalent word, or the poem is about the concept embodied in the word), or it is included to bring attention to the riches of the minority tongue, then the use seems to have integrity. In such cases the word can usefully be italicised or at least glossed as a mark of respect for the minority tongue. If however it is merely used, un-italicised or un-glossed, to make the poem stand out in the general market place of contemporary literature or as part of playful game of words – while that may be fun for poet and non-native reader – such language appropriation can feel patronising and somewhat neo-colonial to those whose language it is and whose heritage it embodies. To them it is not exotic at all. Others no doubt would challenge this view; perhaps see it as “precious”.

I would contend that everything we do should be to enhance our mother tongue, retain its authenticity and build it up so that access to a rich linguistic heritage remains a worthwhile right to hand on to succeeding generations.

This brings me back to the importance of ensuring young people never succumb to the notion that their mother tongue is a debased language; indeed, to the whole issue of the categorisation of language versus dialect.

I have been privileged over the years to have been given opportunities to undertake translation projects, most typically with Nordic poets. Working with these poets, I could see that the distinction between “language” and “dialect” was somewhat arbitrary: Norwegians who speak the majority language (Bokmål) are understood by Danes and Swedes. Yet there is no doubt that these are considered to be languages. And poets from these language groups could understand my poems written in Shetlandic using both their familiarity with their own languages and with English. They described it as a “cousin” language. They also noted that, given their fluency in English, they were surprised just how different was the grammar and vocabulary of Shetlandic from English. These encounters encouraged me, not just in translation per se, but more broadly in my writing. I became more aware of the political and linguistic importance of mother tongue and also less anxious about the distinction between “dialect” and “language”. I tend to use the terms “Shetland dialect” and “Shetlandic” interchangeably to represent this fluidity. It is incumbent on us to build up that literature. Professor Alan Riach, recently writing for The National newspaper (23/9/2016), offered an alternative to the usual belief “A language is a dialect with an army and navy” – he stated “A language is a dialect with a literature.” (p. 27).

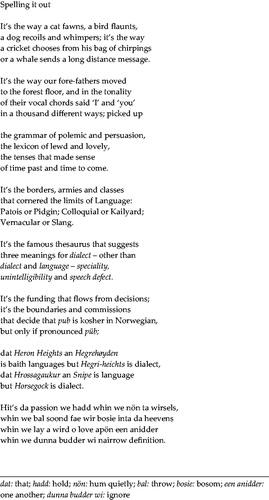

Every effort must be made to ensure that our mother tongue has a future; that children have opportunities not only to hear stories in Shetlandic but to handle books and learn to read and write in it as well and to feel proud of it. The poem Spelling it out (De Luca, Citation2014a, Citation2014b), , starts off in English but while writing it I just could not keep hold of it. But we have to be inventive. Writers can revitalise decaying vocabulary through figurative use and in the context of abstract ideas. Poets perhaps have a particular responsibility in this area.

Figure 2. Spelling it out (De Luca, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Reprinted with permission.

We could say we do not need these words and expressions any more, and that is true; but sometimes we are careless. One story comes to mind. When I was perhaps seven or eight years old, I remember an old lady asking me “His du a calaphine?” I was perplexed by the request “Do you have a …?” Later, when I asked my mother what a calaphine was she was surprised I did not know that it was a pencil. One generation used the word, the next generation knew it but did not use it and the third generation (me) did not know it. Yet there was a word with a long pedigree, linked to calligraphy. And the pencil is still a useful tool!

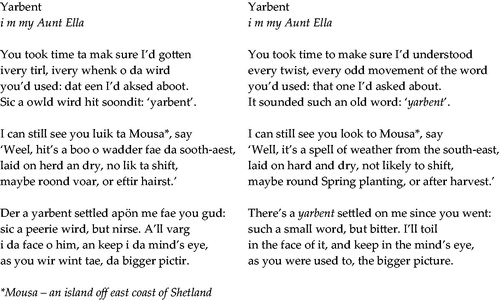

The loss of older relatives often means the loss of a repository of rich language. With aunts and uncles spread across Shetland, as a child I heard many words and idioms, many of which would be unfamiliar today. The poem in , Yarbent (De Luca, Citation2005b), is about one such word, still relevant though perhaps in different contexts.

Figure 3. Yarbent (De Luca, Citation2005b). Reprinted with permission.

So our linguistic human right needs wise and dedicated stewardship if its richness and cultural distinctiveness is to survive and be worth passing on. It so perfectly fits the landscape, the seascape, the stories, the fabric of society, the moods, emotions and attitudes of its people. We need to continue to find practical ways of ensuring it is considered an important asset for succeeding generations.

Declaration of interest

There are no real or potential conflicts of interest related to the manuscript.

References

- De Luca, C. (2005a). Glims o origin. In C. De Luca. Parallel worlds (p. 107). Edinburgh, UK: Luath Press.

- De Luca, C. (2005b). Yarbent. In C. De Luca. Parallel worlds (p. 23). Edinburgh, UK: Luath Press.

- De Luca, C. (2014a). Spelling it out. In C. De Luca. Dat trickster sun (pp. 34–35). Edinburgh, UK: Mariscat Press.

- De Luca, C. (2014b). Wikitongues: Christine speaking Shetlandic. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/m0EwquC6wBU

- Graham, J.J. (1979). The Shetland dictionary. Lerwick, Shetland, UK: The Thule Press.

- Riach, A. (2016, September 23). Putting our identity into our own words. The National, pp. 27.

- Robertson, T.A., & Graham, J.J. (1952). Grammar and usage of the Shetland dialect. Lerwick, Shetland, UK: The Shetland Times.

- Shetland ForWirds. Manuscript in preparation. Retrieved from: https://www.shetlanddialect.org.uk/

- Smith, B. (2000). Wir ain auld language: Attitudes to the Shetland dialect since the nineteenth century. Unpublished paper, p. 15. Lerwick, Shetland, UK: Shetland Arts Trust.

- UNESCO. (2017). International mother language day: Towards sustainable futures through multilingual education. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/international-mother-language-day/

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- United Nations. (2007). A/RES/61/266. Multilingualism. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/ga/search/viewm_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/61/266

- United Nations. (2017). International Mother Tongue Day. 2017 Theme: Towards sustainable futures through multilingual education. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/events/motherlanguageday/

- Voluntary Action Shetland. (2017). The New Shetlander. Retrieved from: http://www.shetland-communities.org.uk/subsites/vas/the-new-shetlander.htm