Abstract

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) states that all people have the right to seek, receive and impart information using any means. Ensuring that people with communication disability achieve this right is inherently challenging. For people with communication disability, who are refugee-survivors of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), additional human rights are challenged, including the right to education, protection from discrimination, a safe place to live, security of person and legal protection. Their experiences and needs, however, are poorly understood. This paper reports on a literature review of the intersectionality between SGBV, being a refugee and having a communication disability, and a preliminary investigation of the situation of refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, in Rwanda. The project involved 54 participants, including 50 humanitarian and partner organisation staff and four carers of refugees with communication disabilities, from two locations (camp-based and urban refugees). Findings from both revealed that, for people with communication disability, barriers are likely to occur at each step of preventing and responding to SGBV. Moreover, stigmatisation of people with communication disability challenges SGBV prevention/support and people with communication disability may be targeted by SGBV perpetrators. SGBV service providers acknowledge their lack of knowledge and skills about communication disability, but wish to learn. Findings highlight the need for increased knowledge and skill development, in order to improve the situation for refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability.

Background

As the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) approaches, there are in excess of 65.6 million people forcibly displaced from their homes – an all-time global record (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2016). A refugee is:

someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence… a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2017a, n.p)

Although fleeing human rights abuses in their home state, refugees may face further violations in their host state, such as liberty (Article 3), protection (Articles 7–9), freedom of movement (Article 13) and acceptable standards of living (Article 25). This may be exacerbated for refugees with communication disability, whose right to communication by any means, to express their needs (Article 19), is compromised.

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) refers to:

any act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and is based on gender norms and unequal power relationships. It encompasses threats of violence and coercion. It can be physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual in nature, and can take the form of a denial of resources or access to services. It inflicts harm on women, girls, men and boys. (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], Citation2017b)

Violation of some human rights, such as the right to education (Article 26), increases vulnerability to SGBV and SGBV itself violates the right to security of person (Article 3), freedom from torture (Article 5) and persecution (Article 14). Although Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) clearly states that all people have the right to freedom of expression and communication by any means, communication disability increases vulnerability to additional human rights violations, including articles relating to liberty, legal protection, education, standards of living and freedom from persecution. In fact, communication disability can potentially compromise the vast majority of human rights, since communication is critical to reporting human rights abuses, seeking help and receiving support. This is particularly the case for accessing legal protection and equality of fair hearing (Articles 4-8). Despite this, speech-language pathology (SLP) research with refugees, particularly in low and middle-income countries, is limited.

When refugee status, SGBV and communication disability co-occur, most Articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are at risk of violation, making refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability arguably some of the most vulnerable people in existence. The intersectionality of these three vulnerabilities was first identified by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) representation office in Rwanda, which protects over 154,000 refugees. Rwanda is a small, landlocked country of almost 12 million people, bordering Eastern and Central Africa. The 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi forced thousands of Rwandans to seek asylum across borders in Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. Now, 23 years later, Rwanda is host to refugees from Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi, due to civil unrest and violence in those countries. UNHCR Rwanda raised concerns about the challenges for refugees with a communication disability, in accessing SGBV prevention and support services, that led to a collaborative project between the two authors, UNHCR and an innovation partner (Institute for Human Centered Design, USA).

The main aims of this project were to document current knowledge about the intersectionality between SGBV, communication disability and refugees, to identify any reported good practice, and to begin to understand and describe the challenges to supporting refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, in Rwanda. This paper reports on this project, its findings and makes recommendations, which are relevant to SLPs and humanitarian actors.

Method

This small-scale project was funded by the Humanitarian Innovation Fund. Two activities were carried out: a literature review and face-to-face data collection. Ethical approval was obtained from Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom. The authors, who led the project, are SLPs, with considerable experience of working in low- and middle-income countries.

Literature review

A literature review was carried out to identify publications that would facilitate understanding of the situation of, and services for, refugee-survivors of SGBV with a communication disability. Literature covering the topics of disability and SGBV in humanitarian contexts, (such as forced displacement or emergency situations) and communication disability and SGBV (including humanitarian and nonhumanitarian contexts both globally and specifically in sub-Saharan Africa), was identified and reviewed for relevance. A systematic approach was taken, but a full systematic review was not carried out. The Manchester Metropolitan University electronic library search system, and Google/Google scholar were searched, using combinations of keywords/phrases (such as disabilit*; violen*; abus*; refugee*). Websites of disability, humanitarian and non-governmental organisations (e.g. UNHCR, UNICEF, Save the Children, Handicap International, Plan International, Women’s Refugee Commission) were also searched, as were the reference lists of documents identified (Scior, Citation2011). Language and dates of publication were not restricted.

Publication types identified included research reports/papers (peer-reviewed and non-peer reviewed), service design/delivery/evaluation reports, guidelines, procedures, policy documents, websites and newspaper articles. The abstracts/websites of identified publications were reviewed for relevance. Only those documents that referred to a minimum of two of the topics of (1) SGBV, (2) disability/communication disability, (3) forced migration/refugees/humanitarian contexts, were included. Full-text versions of all relevant publications were searched for any mentions of the above topics. Publications were not subject to formal quality appraisal, as the literature review was primarily produced as a document for humanitarian organisations, rather than an academic publication, not all publications were research studies and project resources were limited. Documents were subjected to content analysis: relevant identified sections were coded and themes generated and described. A small number of publications were unavailable in full text, but review of the abstracts suggested they did not contradict other publications. A total of 71 items were identified for potential inclusion, and reviewed for relevance. Fifty-four items were included in the final review.

Literature review results

Fifteen publications consistently documented the increased risk for refugees with disabilities to SGBV, compared to people without disabilities (UNHCR, Citation2011; Women’s Refugee Commission, Citation2014). Two papers noted the lack of reliable evidence from humanitarian contexts (Feseha, Abebe, & Gerbaba, Citation2012; Tanabe, Nagujjah, Rimal, Bukania, & Krausse, Citation2015). Risk was reported to be higher for those with additional and/or multiple vulnerabilities, for example, being female and disabled (particularly for people with hearing or intellectual challenges) (Mikton, Maguire, & Shakespeare, Citation2014; Plan International, Citation2016). Literature, mainly from non-humanitarian contexts, documented the vulnerability of people with communication disability to SGBV. Farrar (1996) reported that reduced ability to report and bear witness to abuse, coupled with discreditation and stigma, has led to people with communication disability being targeted for abuse and considered the ‘best victim’ by perpetrators. Evidence exists of repeated, long-term abuse that failed to receive legal redress, as a direct consequence of communication disability (Knutson & Sullivan, Citation1993; Sullivan & Knutson, Citation2000).

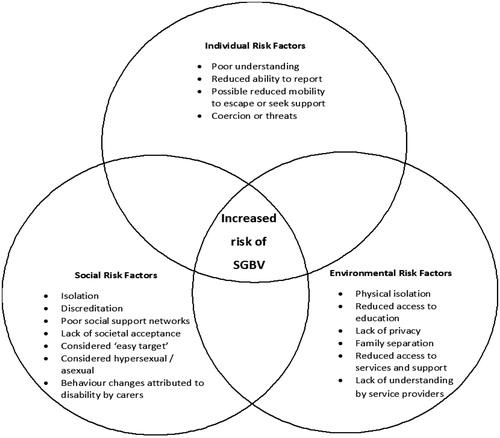

Very little evidence acknowledged the specific vulnerability of people with communication disability to SGBV in humanitarian contexts, despite the risk of exposure to SGBV being much higher for refugees than for the general population (UNHCR, Citation2011; Women’s Refugee Commission, Citation2014). The five identified pieces of literature came primarily from humanitarian organisations specialising in protection/disability, and always as part of wider discussion on disability and SGBV and/or child protection (Plan International, Citation2013; Citation2016; UNHCR, Citation2015; Women’s Refugee Commission, Citation2014; Citation2015). These publications document refugees with communication disability being routinely excluded from sexual and reproductive health education services, formal education, and SGBV response services (including disclosure, medical services, safe spaces, legal redress and ongoing psychosocial support). The risks identified in this literature review are summarised in . Humanitarian organisations recognised their own lack of capacity to involve refugees with communication disability in their consultations, or to respond adequately to their needs when providing protection services (e.g. Women’s Refugee Commission, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Risk factors associated with exposure to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), for refugees with communication disability, identified in the literature review. Figure reproduced from Barrett and Marshall (Citation2017).

The literature review did not reveal any data on the numbers of refugees with communication disability. Data on “speech disability” is coded in UNHCR’s global database, but is acknowledged to be unreliable, as communication disability is not routinely documented and, for people who have more than one disability (e.g. physical, sensory, etc.), this may be coded under the most visible challenge. The type of communication disability a person has is currently not documented by UNCHR.

In terms of good practice, a number of organisations have engaged sign-language users in consultations or used picture-based systems to discuss SGBV prevention with people with communication disability (Women’s Refugee Commission, Citation2014). There is, however, no evidence of long-term, systematic and responsive support for people with communication disability, particularly beyond the reporting stage.

Face-to-face data collection

Although not a research project, qualitative research methods were used to collect field data. Data were collected in Rwanda, using (1) semistructured interviews/focus group discussions with frontline humanitarian staff and carers of refugees with communication disability, and (2) from documents produced at a stakeholder workshop, attended by humanitarian and partner organisation staff. UNHCR staff acted as gatekeepers to recruit focus group discussion participants from frontline humanitarian staff, all of whom have direct contact with refugees with disabilities and/or SGBV service provision. Thirty staff participants took part in one of four focus group discussions. The topics included participants’ views and experiences of working with people with communication disability in the context of SGBV support, SGBV response services, challenges to accessing services for refugees with communication disability and ideas and suggestions to improve service inclusivity. Frontline humanitarian staff acted as gatekeepers to recruit four refugee-carers of people with communication disability to interviews. The topics included views and experiences and challenges of caring for/living with a person with communication disability in a refugee setting, support services and/or challenges to accessing support. SGBV was not raised directly in discussions, due to the sensitive nature of the topic, although it was raised voluntarily by one carer. All participants gave voluntary, informed consent, in the language and format of their choice. Focus group discussions/interviews were conducted by the authors or by briefed UNHCR staff, when access to participants in refugee camps was impossible. A mixture of languages was used, with assistance from a translator. Detailed and, where possible verbatim, contemporaneous notes were taken, in English, as audio recording was not always considered acceptable. Data were subjected to content analysis (Robson, Citation2002), identifying key themes, using apriori and novel codes.

A stakeholder workshop was subsequently held in Kigali, Rwanda attended by 20 people, from nine organisations, including UNHCR, partner organisations and local civil society organisations, to feedback findings from the literature review and focus group discussions/interviews and to further increase understanding of the challenges faced by refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability. “Personas” (fictional case examples) of people with communication disability were used to stimulate discussion about service access for refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability () and key challenges and suggested solutions were generated. Data provided in written form during the workshop were transcribed, subjected to content analysis and combined with interview data.

Focus group discussion/interview/workshop results

The content analysis of data from 54 people generated three themes and seven subthemes, which related primarily, either implicitly or explicitly, to sexual abuse. The main themes included (1) disclosure of SGBV to community leaders or service providers, (2) accessing support, including medical, legal, psychosocial support and protection, and (3) sexual and reproductive health education. Participants described the process of disclosure of SGBV and the possible additional challenges for people with communication disability, such as not being able to report, people with communication disability not being understood or believed due to stigma, and the inherent risks associated with “proxy reporting” (e.g. lack of privacy and autonomy in decisions regarding further reporting). Challenges in disclosure to service providers related primarily to medics and police being unable to understand people with communication disability, requirements to report and provide evidence in person, and lack of evidence if the survivor cannot report verbally. This may result in carers deciding not to report, or the case being dropped in its initial stages.

Challenges to disclosure in turn affect the person with communication disability’s ability to access support: access to medical, legal, and psychosocial support, all of which rely on verbal communication, is compromised. The data indicate the challenges that refugees with communication disability are facing in receiving appropriate support at all stages of response to SGBV. Although the original project focus had been on SGBV responses, some contributions suggested that people with communication disability would also be less likely to access sexual and reproductive health education and SGBV prevention services. Finally, humanitarian actors acknowledged their lack of knowledge and skills to support refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, and reported a desire to increase their capacity to respond to their needs effectively.

Discussion and recommendations

This literature review and small exploratory investigation have highlighted the specific vulnerabilities of refugee-survivors of SGBV who have communication disability. The content analysis of focus group discussion/interview and workshop data confirmed a number of the findings from the literature review, including increased risk of SGBV for people with communication disability, due to factors including reduced access to sexual and reproductive health education, discreditation, stigma, being considered an easy target, lack of understanding by service providers and reduced ability to report. These findings together confirm the assertion that refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability may have several of their human rights compromised or denied, that they may lack sexual and reproductive health education, and that they may be at increased risk of SGBV and to receiving inappropriate responses to it.

Recommendations

The data highlight how, despite limited literature on the specific needs of refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, the literature on the intersection of the three topics complemented the views and experiences of humanitarian actors working on the ground in Rwanda, thereby validating a call to action for this vulnerable group. Based on this project, recommendations on improving the situation of refugees with communication disability (particularly in low and middle-income countries), in relation to prevention of, and appropriate responses to, SGBV, include:

Identification and registration of people with communication disability in refugee settings. This will require amendment of current documentation systems and staff training/sensitisation.

Sexual and reproductive health education appropriate to people with a wide range of communication needs, and relevant particularly to adolescent girls.

Inclusive education and employment for people with communication disability, to increase independence and reduce stigma.

Awareness raising and training about communication disability for SGBV staff and all actors within the criminal justice system.

Involving refugees with communication disability and their carers in SGBV and sexual and reproductive health education, service-planning, implementation and evaluation.

Developing a range of appropriate communication methods in order to facilitate wider access to both sexual and reproductive health education and SGBV services.

Inclusive, non-discriminatory practice integral to all programming, using a rights-based approach.

Multi-agency collaboration to ensure services are appropriate to people with communication disability.

High-quality funded research on SGBV, communication disability and refugees.

The project recommendations were shared with all stakeholders involved in the project in Rwanda, and with UNHCR Geneva. The project website (Humanitarian Innovation Fund, Citation2016) contains an open-access description on the project and a project blog. The full literature review (Barrett & Marshall, Citation2017) is open access and has been disseminated widely. It is hoped that this will sensitise relevant stakeholders to the situation of refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, the challenges to their human rights and how their situation may begin to be improved. A second-stage project is under development, to further investigate the specific challenges to providing SGBV services for refugees with communication disability faced by service providers, and the challenges refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability face in accessing support. These findings aim to facilitate the improvement of appropriate and tailored services for refugee-survivors of SGBV with communication disability, thereby reducing the human rights violations experienced by those who cannot communicate their needs and experiences effectively.

Declaration of interest

There are no real or potential conflicts of interest related to the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors acknowledge the help from UNHCR Rwanda and Institute for Human-Centered Design, USA.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barrett, H., & Marshall, J. (2017). Understanding sexual and gender-based violence against refugees with communication disability and challenges to accessing appropriate support: A literature review. Retrieved from http://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/sgbv-literature-review.pdf

- Conte, J.R., Wolf, S., & Smith, T. (1989). What sexual offenders tell us about prevention strategies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 13, 293–301. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(89)90016-1

- Feseha, G., Abebe, M.G., & Gerbaba, M. (2012). Intimate partner physical violence among women in Shimelba refugee camp, northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health, 12, 125–134. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-125

- Humanitarian Innovation Fund. (2016). Supporting refugee-survivors of GBV with communication disability. Retrieved from http://www.elrha.org/map-location/supporting-refugee-survivors-gbv-communication-disability/

- Knutson, J.F., & Sullivan, P.M. (1993). Communicative disorders as a risk factor in abuse. Topics in Language Disorders, 134, 1–14. doi:10.1097/00011363-199308000-00005

- Mikton, C., Maguire, H., & Shakespeare, T. (2014). A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to prevent and respond to violence against persons with disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 3207–3226. doi:10.1177/0886260514534530

- Plan International (2013). Outside the circle: A research initiative by Plan International into the rights of children with disabilities to education and protection in West Africa. Retrieved from https://planinternational.org/outside-circle

- Plan International (2016). Protect us! Inclusion of children with disabilities in child protection. Executive summary. Retrieved from https://plan-international.org/protect-us

- Robson, C. (2002). Real world research (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley.

- Scior, K. (2011). Public awareness, attitudes and beliefs regarding intellectual disability: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2164–2182. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.005

- Sullivan, P.M., & Knutson, J.F. (2000). Maltreatment and disabilities: A population-based epidemiological study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 1257–1273. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00190-3

- Tanabe, M., Nagujjah, Y., Rimal, N., Bukania, F., & Krausse, S. (2015). Intersecting sexual and reproductive health and disability in humanitarian settings: Risks, needs and capacities of refugees with disabilities in Kenya, Nepal and Uganda. Sexuality and Disability, 33, 411–427. doi:10.1007/s11195-015-9419-3

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2011). Action against sexual and gender-based violence: An updated strategy. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/4e1d5aba9.pdf

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2015). Strengthening protection of persons with disabilities in forced displacement: Rwanda mission report. Geneva: UNHCR (Unpublished).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2016). Global trends: Forced displacement in 2016. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/5943e8a34

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2017a). What is a refugee? Retrieved from http://www.unrefugees.org/what-is-a-refugee/

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (2017b). Sexual and gender-based violence. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/sexual-and-gender-based-violence.html

- Women’s Refugee Commission. (2014). Disability inclusion: Translating policy into practice in humanitarian action. Retrieved from https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/disabilities/disability-inclusion

- Women’s Refugee Commission. (2015). “I see that it is possible”: Building capacity for disability inclusion in gender-based violence programming. Retrieved from https://www.womensrefugeecommission.org/disabilities/resources/document/945-buildingcapacity-for-disability-inclusion-in-gender-based-violence-gbv-programming-in-humanitariansettings-overview?catid =232