Abstract

The right to communicate includes the right to “freedom of opinion and expression” and rights and freedoms “without distinction of … language”. The 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a time to celebrate and reflect on communication as a human right, particularly with respect to Article 19 and its relationship to national and international conventions, declarations, policies and practices. This review profiles articles from the special issue of International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology (volume 20, issue 1) addressing communication rights from four perspectives: (1) communication rights of all people; (2) communication rights of people with communication disabilities; (3) communication rights of children and (4) communication rights relating to language. Divergent perspectives from across the globe are considered. First-hand accounts of people whose right to communicate is compromised/upheld are included and perspectives are provided from people with expertise and advocacy roles in speech-language pathology, audiology, linguistics, education, media, literature and law, including members of the International Communication Project. Three steps are outlined to support communication rights: acknowledge people – adjust the communication style – take time to listen. Future advocacy for communication rights could be informed by replicating processes used to generate the Yogyakarta Principles.

Introduction

Communication is a fundamental feature of humanity. The ability to communicate – to receive, process, store and produce messages – is central to human interaction and participation. To understand and to be understood not only enables expression of basic needs and wants; but also enables interaction and participation at a family, community, national and global level. All humans, regardless of their age or capacity, send and receive communicative messages. Human communication can be expressed through law, poetry, mathematics, history, conversation, music, art and social media, linking humans across time, generations and continents. The primary modes of communication privileged in many societies are speaking, listening, reading and writing, but can include other modes such as sign languages, online audio/video communication or non-verbal modes such as crying and touch. Effective communication may be compromised for those who have reduced capacity to use these four privileged modes of communication, and for those who rely on modes of communication and languages that are not mainstream in their communities (e.g. sign language, braille, augmentative and alternative communication [AAC], and minority languages and dialects). Barriers to effective communication can occur at an individual or societal level (e.g. attitudinal barriers), and particularly impact people with communication disabilities, children, and those who do not speak the dominant language(s) of their communities.

Communication rights in international conventions and declarations

Communication is a fundamental human right (McEwin & Santow, Citation2018). The first time this right was enunciated at an international level was in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. (United Nations, Citation1948)

This powerful statement underscores that all people have the right to communicate. Article 19 is not just a right for people who can communicate effectively within their dominant culture. All people, regardless of their age, status, ability or communicative capacity have the right to receive and convey messages, to hold opinions, and express themselves. Everyone should uphold others’ right to communicate as they interact with people in daily life in order to enhance equality, justice and human dignity. Communication rights address both “freedom of opinion and expression” and rights and freedoms “without distinction of … language” (United Nations, Citation1948) and have been enshrined in multiple international conventions and declarations (see Supplemental Appendix). For example, the “right to freedom of opinion and expression” and similar phrases also are specifically mentioned in:

Articles 19 and 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, Citation1966a)

Articles 5 and 15 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (United Nations, Citation1965)

Articles 12 and 13 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989)

Article 21 of Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006)

Respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms “without distinction of … language” is specifically articulated in the following articles:

Article 2 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948)

Articles 2, 4, 14, 24 and 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, Citation1966a)

Article 2 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (United Nations, Citation1966b)

Article 6 of the Declaration on the Right to Development (United Nations, Citation1986)

Articles 2, 29, 30 and 40 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989)

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (UNESCO, Citation2001)

Article 10 of the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (United Nations, 2015)

and the Preambles and Annexes of a number of other declarations, such as:

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (United Nations, Citation1965)

Millennium Declaration (United Nations, Citation2000)

Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (UNESCO, Citation2005)

Declaration on the Right to Peace (United Nations, 2015)

Communication rights also are articulated in Article 5 of the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity that states “All persons have therefore the right to express themselves and to create and disseminate their work in the language of their choice, and particularly in their mother tongue” (UNESCO, Citation2001). Articles 13, 14 and 16 of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples support the revitalisation, use, development and transmission of “language, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures” (United Nations, Citation2007a).

The importance of communication rights is obvious, since they are included in almost every convention, declaration and covenant of the United Nations with few exceptions. Communication rights are also included in the UNESCO conventions and declarations. However, the importance of communication rights goes beyond just enabling freedom of opinion, expression and language. Once these rights are realised, people are more readily able to realise other human rights.

Communication rights to freedom of opinion, expression and language enables people to realise other human rights including the right to work, education, marry and found a family, own property, self-determination, freedom of religion and social security (United Nations, Citation1948). People whose communication and language skills are different from those within mainstream society may not be able to completely participate in the activities of society without targeted support (Carroll et al., Citation2017). For example, many people have aphasia following a stroke, which can “rob people of their ‘freedom of expression’ at a fundamental level, threatening their identity, and disrupting their ability to demonstrate competence, share experience, and participate in life as before”. Aphasia “depletes social networks…, impedes return to work … and results in ‘third party disability’ for families” (Hersh, Citation2017, p. 40).

Communication rights are increasingly important in the twenty-first century where the survival of the fittest relies on communicative capacity rather than manual labour skills (Ruben, Citation2000). For example, in a population study, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2017a) indicated 73.0% of people with communication disability reported employment restrictions and 25.3% reported no participation in activities away from home in the last 12 months. People who have difficulty in communicating may also be vulnerable to human rights abuses (World Health Organization & the World Bank, Citation2011), including sexual and gender-based violence since “communication is critical to reporting human rights abuses, seeking help, and receiving support” (Marshall & Barrett, Citation2017, p. 45).

International efforts to promote communication rights

There have been a number of international efforts to promote communication rights. For example, in 1974, the UNESCO received the Report on the Means of Enabling Active Participation in the Communication Process and Analysis of the Right to Communicate and there have been subsequent resolutions, charters and declarations (The Right to Communicate, n.d.). In 2014, communication as a human right was articulated in the Universal Declaration of Communication Rights and has been signed by over 10 000 people (Mulcair, Pietranton, & Williams, Citation2018). The pledge that is within the Universal Declaration of Communication Rights states:

We recognise that the ability to communicate is a basic human right.

We recognise that everyone has the potential to communicate.

By putting our names to this declaration, we give our support to the millions of people around the world who have communication disorders that prevent them from experiencing fulfilling lives and participating equally and fully in their communities.

We believe that people with communication disabilities should have access to the support they need to realise their full potential (International Communication Project, Citation2014).

This Declaration was created through collaboration between the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Speech-Language & Audiology Canada | Orthophonie et Audiologie Canada, Irish Association of Speech and Language Therapists, New Zealand Speech-language Therapists’ Association, Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists, and Speech Pathology Australia.

Communication rights through language diversity are upheld throughout international organisations including the United Nations and the World Health Organization. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has been translated into over 500 languages, more than any other document in the world. The United Nations (Citation2007b) adopted Resolution 61/266 Multilingualism and acknowledged that multilingualism “promotes unity in diversity and international understanding”. International Mother Language Day was proclaimed in 1999 and is celebrated each year on 21 February (United Nations, Citation2017a). The International Year of Languages was celebrated in 2008 and 2019 will be the International Year of Indigenous Languages (United Nations, Citation2017b).

This special issue of the International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology celebrates the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The authors expand the discussion of international conceptualisation of communication as a human right as it relates not only to Article 19, but also to subsequent national and international conventions, declarations, legislations and policies (see Supplemental Appendix). This special issue of the International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology addresses communication as a human right from four perspectives: (1) communication rights of all people; (2) communication rights of people with communication disabilities; (3) communication rights of children and (4) communication rights relating to language. In many cases, these four perspectives overlap, with some papers drawing on each aspect, such as the paper by Wofford and Tibi (Citation2017) that addresses the human rights of children in the US who are Syrian refugees experiencing difficulties with communication and literacy. In order to examine a broad range of interpretations of communication as a human right, this special issue draws on divergent perspectives from across the world (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Fiji, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Shetland, South Africa, Sweden, Syria, UK and USA). Three papers focus on the first-hand accounts of people whose right to communicate was either compromised or upheld (De Luca, Citation2017; McCormack, Baker, & Crowe, Citation2018; Murphy, Lyons, Carroll, Caulfield, & De Paor, 2017). Other papers are written by people with expertise and advocacy roles in speech-language pathology, audiology, linguistics, education, psychology, media, literature and law. Additionally, this special issue has embraced the notion of imparting “information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers” by not only including research articles and reviews, but by including short commentaries, invited papers and poetry. For example, De Luca (Citation2017) was invited to include her poetry addressing the importance of supporting and maintaining Shetlandic, the mother tongue in Shetland. The focus of the rest of this paper is to expand the understanding of communication rights from these four perspectives: (1) all people, (2) people with communication disabilities, (3) children and (4) language.

Communication rights of all people

Communication rights of all people include the right to both “freedom of opinion and expression” and rights and freedoms “without distinction of … language”. The right to “freedom of opinion and expression” from Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948) was re-asserted and reframed Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, Citation1966a) and states:

Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

For respect of the rights or reputations of others.

For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals (United Nations, 1966, Article 19).

These communication rights apply to all people: citizens and non-citizens alike. The prevailing interpretation of the right to freedom of opinion and expression relates to civil and political rights (Howie, Citation2017). For example, free speech addresses “the right to vote, free assembly and freedom of association, and is essential to ensure press freedom” (Howie, Citation2017, p. 12). Freedom of the press is being challenged in the current climate of terrorism and anti-terrorism laws (Anyanwu, Citation2018; Howie, Citation2017). Further, the right to freedom of opinion and expression has been tested due to significant changes in the ability to communicate through the Internet and social media (Kaye, Citation2016). International media, social media and public debate frequently focus on freedom of opinion and expression in these domains.

Typically, current interpretations of the right to freedom of opinion and expression within a civil society do not take into account of those people whose ability to communicate is restricted in some way. Within this special issue of the International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, examples are provided whereby people with communication restrictions are supported to communicate and participate in a civil society. For example, Murphy provides a first-hand account of his passion for politics and public speaking and instructs others about how to communicate with people with Down syndrome (Murphy et al., Citation2017). Martin describes Just Sentences, a prison-based literacy program facilitating participation of offenders in democratic society (Martin, Citation2018). These examples extend our understanding of support required to enact communication rights in a civil society.

Communication rights of people with communication disabilities

For people with communication disabilities, their “voice (i.e. what they want to communicate)” may not be heard due to their “lack of voice (i.e. mode of communication)” (McCormack et al., Citation2018, p. 142). People with communication disabilities have difficulties receiving and producing communicative messages in their home language(s). That is, they have difficulty with speech, language, voice, fluency (stuttering), hearing and/or social interaction in the language(s) that they have learned from birth and subsequently. The term speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) has been used as an umbrella term to describe “difficulties with fluency, forming sounds and words, formulating sentences, understanding what others say, and using language socially” (Bercow, Citation2008, p. 13). Most communication disabilities have no known cause; however, some known causes include hearing loss, cleft lip and palate, intellectual disability, neurological disorders (e.g. cerebral palsy, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease), and illness (e.g. cancer). The prevalence of communication disability is high, with higher prevalence in children and older adults, and in males than females (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017a; McLeod & McKinnon, Citation2007). Over a quarter (27.4%) of people with a disability experience a communication disability (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017a). The World Report on Disability documented that approximately 15% of the world’s population have a disability; however, they indicated, “people with…communication difficulties, and other impairments may not be included in these estimates [of disability], despite encountering difficulties in daily life” (World Health Organization and the World Bank, 2011, p. 22).

Communication support for people with communication disabilities

Article 21 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, Citation2006) particularly focuses on the communication rights of people with disabilities:

Freedom of expression and opinion, and access to information. States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that persons with disabilities can exercise the right to freedom of expression and opinion, including the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas on an equal basis with others and through all forms of communication of their choice, as defined in article 2 of the present Convention, including by:

Providing information intended for the general public to persons with disabilities in accessible formats and technologies appropriate to different kinds of disabilities in a timely manner and without additional cost.

Accepting and facilitating the use of sign languages, Braille, augmentative and alternative communication, and all other accessible means, modes and formats of communication of their choice by persons with disabilities in official interactions.

Urging private entities that provide services to the general public, including through the Internet, to provide information and services in accessible and usable formats for persons with disabilities.

Encouraging the mass media, including providers of information through the Internet, to make their services accessible to persons with disabilities.

Recognizing and promoting the use of sign languages (United Nations, Citation2006, Article 21).

Article 21 provides important guidance for supporting people with communication disability. Many of the examples relate to provision of information, technologies and language choice for people with associated sensory or physical disabilities and include initiatives such as the Communication Bill of Rights (Brady et al., Citation2016) and the use of the communication access symbol (Scope, Citation2017). This special issue provides further examples of individual and societal support to enhance the communication rights for people with communication disability.

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) provide targeted assessment and intervention to support the realisation of communication rights and social participation for people with communication disabilities. While the majority of people who receive intervention from SLPs are children and older adults, this special issue also highlights successful intervention for adolescents and young adults including intervention for increasing intelligibility in adolescents with Down syndrome (Rvachew & Folden, Citation2017), and intervention to increase clarity and political advocacy for a young adult with Down syndrome (Murphy et al., Citation2017). People with communication disabilities also receive support from friends, families, community members, other health and education professionals, and online. Madill, Warhurst, and McCabe (Citation2017) describe the Stakeholder Model as a method for acknowledging the role of the speaker, listener and communication context for people with voice disorders, including in occupational contexts. Carroll et al. (Citation2017) describe a partnership between people with communication disability, SLPs, and the local community to enhance social participation in coffee shops and restaurants. Hersh (Citation2017) portrays national and global support for people with aphasia via initiatives such as Aphasia United (www.aphasiaunited.org) providing the best practice guidelines and networking opportunities. Hemsley, Palmer, Dann, and Balandin, (Citation2018) describe methods to support people who communicate through alternative and augmentative communication to use Twitter as a means of social participation.

Inequities in access to communication specialists (including SLPs) and appropriate assessment and intervention resources are a major issue for people with communication disabilities across the world. For example, in Saudi Arabia only 29 of 196 (14.7%) major hospitals employ SLPs (Khoja & Shesha, Citation2018). In rural Australia, Jones, McAllister, and Lyle (Citation2017) describe limited access to services for children with communication disabilities. They propose that civically engaged healthcare, where health and educational professionals collaborate with local residents using a strengths-based approach may provide a solution. They describe how speech-language pathology students from metropolitan universities undertake fieldwork placements in remote Australian locations, working collaboratively with communities to support children’s speech and language competence.

In Majority World countries, creative solutions for supporting and equipping local communication specialists are important (Hopf, Citation2017; Marshall & Barrett, Citation2017; Sprunt & Marella, Citation2018). The Communication Capacity Research program (Hopf, Citation2017) was developed for Majority World countries to respectfully support the development of services in low resource settings. Hopf (Citation2017) applied the four-stage program to the people of Fiji by: “(1) gathering knowledge from policy and literature; (2) gathering knowledge from the community; (3) understanding speech, language and literacy use and proficiency; and (4) developing culturally and linguistically appropriate resources and assessments.” (p. 86). Sprunt and Marella (Citation2018) describe international efforts by the UNICEF/Washington Group to develop a culturally and linguistically appropriate assessment for Fiji. They validated the Child Functioning Module to assist Fijian parents and teachers to identify children with speech and language difficulties.

For people with communication disability, “communication is not merely the tool needed to address a problem, it is the area that we wish to address” (Pascoe, Klop, Mdlalo, & Ndhambi, Citation2017, p. 68). The intersection between communication rights and language rights is a major challenge for the speech-language pathology profession in South Africa (Pascoe et al., Citation2017). South Africa has 11 official languages, with isiZulu and isiXhosa being the most widely spoken. However, most SLPs in South Africa speak either Afrikaans or English. For people with communication disability in South Africa, there are few assessments, interventions, resources, and guidelines that are culturally or linguistically appropriate, so when children or adults experience communication disability, they are limited in both their ability to communicate and to use their home language to seek and receive assistance. Pascoe et al. (Citation2017) describe work to develop rights-driven guidelines for the speech-language pathology profession by the Language and Culture Task Team, sponsored by the Health Professions Council of South Africa.

Technology can also be a solution to supporting the rights of people with communication disabilities. For example, van den Heuij, Neijenhuis, and Coene (Citation2017) describe the importance of the acoustic environment for enabling access to higher education for all people, including those with hearing loss. Their research highlights that something as simple as using a microphone in a lecture hall can significantly increase students’ participation and accessibility to information. Another technological solution to supporting the rights of people with communication disorders is via large databases of audio, video and transcript files, such as those found within the TalkBank system (https://talkbank.org). MacWhinney, Fromm, Rose, and Bernstein Ratner (Citation2017) describe how they curate speech and language data from people across four of 12 spoken language TalkBanks: AphasiaBank, AphasiaBank Extensions (e.g. DementiaBank), PhonBank and FluencyBank. These TalkBanks comprise speakers’ data from numerous languages, including indigenous languages, and have been used by SLPs, phoneticians, psychologists and educators, for research that can enhance communication rights of people with and without communication disability. Innovative solutions to inequities in access have been created; however, further advocacy and resourcing is required to support people with communication disabilities to fully participate in the society (Mulcair et al., Citation2018).

Communication rights of children

Children are not just citizens of the future, but are people of today. Children comprised 26% of the world’s population in 2016, with a higher proportion in low-income countries (43%) than in high-income countries (17%) (World Bank Group, Citation2017). This special issue considers communication rights of children from diverse settings in Australia, Canada, Fiji, Ireland, Shetland, New Zealand, South Africa and the US.

Children’s communication rights specifically are explained within the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, Citation1989), particularly in Articles 2, 12, 13, 29, 30 and 40. Articles 12 and 13 relate to freedom of opinion and expression:

Article 12. 1. States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child…

Article 13. 1. The child shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child's choice… (United Nations, 1989)

Articles 2, 29, 30 and 40 relate to children’s language; for example, Article 40 includes “To have the free assistance of an interpreter if the child cannot understand or speak the language used” (United Nations, 1989).

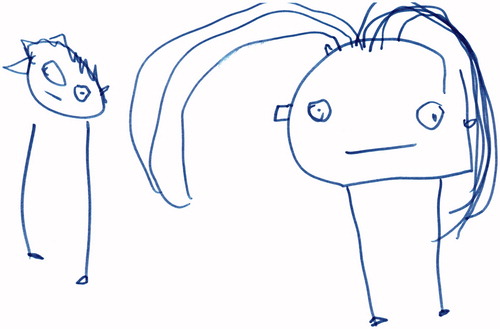

Children communicate in multiple ways. Consequently, limited notions of appropriate or accepted forms of communication may limit children’s rights (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant, Citation2017). Creativity in listening to children is important (Roulstone & McLeod, Citation2011). Pre-school children with speech sound disorders have been invited to draw themselves talking to someone and often highlighted mouths and ears potentially indicating the importance of speaking and listening in the communicative exchange (McCormack, McLeod, McAllister, & Harrison, Citation2010). For example, depicts a young boy with speech sound disorder, Tim (on the left), talking with his sister (on the right). Tim featured his sister's listening ears in his drawing. In this special issue, McCormack et al. (Citation2017) provide an opportunity to listen to the voices of people with a history of childhood communication disorder by analysing submissions to an Australian Government Senate Committee Inquiry. Some of the words and phrases used by these people to describe the impact of their communication disorder included “fear”, “embarrassment”, “withdrawing”, and “holding back from showing the real you” (p. 146). One person wrote “When I was at school, I can remember spending every lunch time sitting by myself because no one will even try to talk to me” (p. 147).

Figure 1. Communication includes producing (e.g. speaking) and receiving (e.g. listening) messages as exemplified in this drawing by a pre-school boy of himself (left) talking with his sister (right). Reprinted with permission from McLeod, Harrison, McAllister and McCormack (2012).

Children’s engagement with education is a key place where communication rights need to be enacted. As outlined by Gillett-Swan and Sargeant (Citation2017) “Educational instruction maintains a heavy reliance on linguistic competence as a precondition to free expression” (p. 122). Gallagher, Tancredi, and Graham (Citation2017) challenge the role of SLPs in the school context, advocating they move beyond the “dilemma of difference” (p. 129) when providing assessment and intervention to embracing a human rights focus encompassing listening to children, collaboration with teachers, and a capabilities approach to building communication skills.

Adults’ awareness of children’s rights is an important beginning to the realisation of communication rights. As adults become more aware and change their attitudes, children’s rights to communication and participation will develop (Gillett-Swan & Sargeant, Citation2017). Doell and Clendon (Citation2017) document how a rights-based approach was being used to develop the New Zealand Ministry of Education’s proposal for supporting children with communication disabilities. Issues that were incorporated into the design included accessing children’s voice, and the importance of information, coordination, holistic practice, and partnership with parents and families. Wang, Harrison, McLeod, and Spilt (Citation2017) highlighted the importance of the relationship between teachers and children within education settings by examining longitudinal data from over 3000 children. They documented that close and less conflicted teacher-child relationships were associated with a supportive context for development of language, literacy and social-emotional skills.

Communication rights relating to language

There are 7099 languages spoken throughout the world (Simons & Fennig, Citation2017). The most commonly spoken first languages include Chinese, Spanish, English, Hindi and Arabic (Simons & Fennig, Citation2017). The majority of the world speaks more than one language with English being one of the most common second languages. In the US, 20.8% of the population speaks a language other than English at home, over 300 languages are spoken, and 12.9% of the US population speaks Spanish at home (Ryan, Citation2013). In Australia, 22.2% speaks a language other than English at home with the most commonly spoken languages after English being: Mandarin, Arabic, Cantonese, Italian and Vietnamese (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2017b). Competence in the dominant language of the country/community is a strong predictor of self-sufficiency for humanitarian migrants (Blake, Bennetts Kneebone, & McLeod, Citation2017) and multilingual competence in both the home language and the dominant language is associated with higher employment, education and income (Blake, McLeod, Fuller & Verdon, Citation2016). Multilingualism has many individual, social, economic, political and cognitive benefits (Pietiläinen, Citation2011).

Governments play a major role in supporting or denying communication rights relating to language and culture. For example, Simon-Cereijido (Citation2017) outlines the impact of eliminating bilingual public education in California in 1998 (Proposition 227), then the reversal of this by supporting multilingual programs in 2016 (Proposition 58). Freeman and Staley (Citation2017) outline the longitudinal impact of language policies on Aboriginal students within Australia’s education system. They advocate for equivalent educational policies for all Australians who are learning English as an additional language (regardless of whether they speak Spanish, Vietnamese, or an Indigenous language such as Pitjantjatjara), recognising that the majority of remote Aboriginal students do not speak English as their first language.

SLPs also play an important role in supporting home languages and dialects, beyond the exclusive use of the national language (Simon-Cereijido, Citation2017). For example, Farrugia-Bernard (Citation2017) describes how in the United States, students of colour are overrepresented in special education. She indicates “School-based SLPs in the United States may be unwittingly contributing to this phenomenon, obstructing the human right to communication because of biased assessment procedures” (p. 170) that do not take into account dialect diversity. Similarly Cruz-Ferreira (Citation2017) argues that SLPs’ academic and clinical assessment practices must “account for full linguistic repertoires”, acknowledging multilingual speakers’ multifaceted and differential use of languages extend beyond “multi-monolingualism” (Cruz-Ferreira, Citation2017, p. 168; Hopf, Citation2017).

Language maintenance is supported via the intersection between spoken and written language. In her invited commentary, De Luca (Citation2017) creatively charts language maintenance and loss of the Shetlandic dialect/language through three poems and her personal narrative. Wofford and Tibi (Citation2017) advocate that to support Syrian refugee children’s literacy, the high levels of Arabic literacy of their parents should be used as a resource. Respect for the language and culture of the community is important for individuals and society, but is particularly important for supporting people with communication disabilities.

The future

Interpretation of communication rights requires consideration of how human rights relate to (1) all people, (2) people with communication disabilities, (3) children and (4) language. To foster and develop people's right to communicate: acknowledge people, adjust the communication style, and take time to listen. A formal set of principles to guide application of international human rights law in relation to communication and language could build on the processes undertaken to create the Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org). The Yogyakarta Principles were defined in 2006 by a group of experts in conjunction with the United Nations and specify 29 principles covering rights to universal enjoyment of human rights (principle 1), equality and non-discrimination (principle 1), fair trial (principle 8), work (principle 12), social security (principle 13), and highest attainable standard of health (principle 17). The Yogyakarta Principles are not legally binding, or part of human rights law, but are intended to provide an interpretive aid to human rights treaties. These principles are relevant to areas of discrimination and disadvantage experienced by people who are denied communication and language rights so could provide guidance for future analysis and interpretation of communication rights. The ability to communicate freely and successfully, underpins the realisation not only of Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but most other human rights as well. We hope this special issue of the International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology contributes to the celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, provides a broader understanding of communication rights, and supports our world’s focus on human rights into the future.

Declaration of interest

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2018.1428687.

References

- Anyanwu, C. (2018). The fear of communicating fear versus the fear of terrorised legislation: A human rights violation or sign of our time? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20 26–33. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1419281.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017a). 4430.0 - Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings, 2015: Australians living with communication disability. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4430.0Main+Features872015?OpenDocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017b). Quickstats. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/2016%20QuickStats

- Bercow, J. (2008). The Bercow report: A review of services for children and young people (0-19) with speech, language and communication needs. London, UK: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

- Blake, H.L., Bennetts Kneebone, L., & McLeod, S. (2017). The impact of oral English proficiency on humanitarian migrants’ experiences of settling in Australia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1294557.

- Blake, H.L., McLeod, S., Verdon, S., & Fuller, G. (2016). The relationship between spoken English proficiency and participation in higher education, employment and income from two Australian censuses. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/17549507.2016.1229031.

- Brady, N.C., Bruce, S., Goldman, A., Erickson, K., Mineo, B., Ogletree, B.T., … Wilkinson, K. (2016). Communication services and supports for individuals with severe disabilities: Guidance for assessment and intervention. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121, 121–138. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121

- Carroll, C., Guinan, N., Kinneen, L., Mulheir, D., Loughnane, H., Joyce, O., … Lyons, R. (2017). Social participation for people with communication disability in coffee shops and restaurants is a human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 59–62. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1397748.

- Cruz-Ferreira, M. (2017). Assessment of communication abilities in multilingual children: Language rights or human rights? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 166–169. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392607.

- De Luca, C. (2017). Mother tongue as a universal human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 161–165. doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1392606.

- Doell, E. & Clendon, S. (2017). Upholding the human right of children in New Zealand experiencing communication difficulties to voice their needs and dreams. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 152–156. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392611

- Farrugia-Bernard, A.M. (2017). Speech-language pathologists as determiners of the human right to diversity in communication for school children in the US. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 170–173. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1406002.

- Freeman, L.A., & Staley, B. (2017). The positioning of Aboriginal students and their languages within Australia’s education system: A human rights perspective. International Journal off Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 174–181. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1406003.

- Gallagher, A.L., Tancredi, H., & Graham, L.J. (2017). Advancing the human rights of children with communication needs in school. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 128–132. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1395478.

- Gillett-Swan, J., & Sargeant, J. (2017). Assuring children’s human right to freedom of opinion and expression in education. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 120–127. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1385852.

- Hemsley, B., Palmer, S., Dann, S., & Balandin, S. (2018). Using Twitter to access the human right of communication for people who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 50–58, doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1413137.

- Hersh, D. (2017). From individual to global: Human rights and aphasia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 39–43, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1397749.

- Hopf, S.C. (2018). Communication Capacity Research in the Majority World: Supporting the human right to communication specialist services. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 84–88, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1400101.

- Howie, E. (2017). Protecting the human right to freedom of expression in international law. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 12–15, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392612.

- International Communication Project. (2014). Universal declaration of communication rights. Retrieved from https://internationalcommunicationproject.com/get-involved/sign-the-pledge/

- Jones, D.M., McAllister, L., & Lyle, D.M. (2017). Rural and remote speech-language pathology service inequities: An Australian human rights dilemma. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 98–102. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1400103.

- Kaye, D. (2016). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression (A/HRC/32/38). Geneva, Switzerland: Human Rights Council. Retrieved from http://ap.ohchr.org/documents/dpage_e.aspx?si=A/HRC/32/38

- Khoja, M., & Shesha, H. (2018). The human right to communicate: A survey of available services in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 103–107. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1428686.

- MacWhinney, B., Fromm, D., Rose, Y., & Bernstein Ratner, N. (2017). Fostering human rights through TalkBank. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 115–119. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392609.

- Madill, C., Warhurst, S., & McCabe, P. (2017). The Stakeholder Model of voice research: Acknowledging barriers to human rights of all stakeholders in a communicative exchange. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 63–66, doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1400102.

- Marshall, J., & Barrett, H. (2017). Human rights of refugee-survivors of sexual and gender-based violence with communication disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 44–49, doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1392608.

- Martin, R. (2018). Just Sentences: Human rights to enable participation and equity for prisoners and all. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 21–25, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1422024.

- McCormack, J., Baker, E., & Crowe, K. (2017). The human right to communicate and our need to listen: Learning from people with a history of childhood communication disorder. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 142–151. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1397747.

- McCormack, J., McLeod, S., McAllister, L., & Harrison, L.J. (2010). My speech problem, your listening problem, and my frustration: The experience of living with childhood speech impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41, 379–392. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0129)

- McEwin, A., & Santow, E. (2018). The importance of the human right to communication. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 1–2. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1415548.

- McLeod, S., & McKinnon, D.H. (2007). The prevalence of communication disorders compared with other learning needs in 14,500 primary and secondary school students. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 37–59. doi:10.1080/13682820601173262

- Mulcair, G., Pietranton, A.A., & Williams, C. (2018). The International Communication Project: Raising global awareness of communication as a human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 34–38, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1422023.

- Murphy, D., Lyons, R., Carroll, C., Caulfield, M., & Paor, D.G. (2017). Communication as a human right: Citizenship, politics and the role of the speech-language pathologist. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 16–20, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1404129.

- Pascoe, M., Klop, D., Mdlalo, T., & Ndhambi, M. (2017). Beyond lip service: Towards human rights-driven guidelines for South African speech-language pathologists. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 67–74, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1397745.

- Pietiläinen, J. (2011). Public opinion on useful languages in Europe. European Journal of Language Policy, 3, 1–14. doi:10.3828/ejlp.2011.2

- Roulstone, S., & McLeod, S. (Eds.). (2011). Listening to children and young people with speech, language and communication needs. London, UK: J&R Press.

- Ruben, R.J. (2000). Redefining the survival of the fittest: Communication disorders in the 21st century. Laryngoscope, 110(1), 241–245. doi:10.1097/00005537-200002010-00010.

- Rvachew, S., & Folden, M. (2017). Speech therapy in adolescents with Down syndrome: In pursuit of communication as a fundamental human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 75–83, doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392605.

- Ryan, C. (2013). Language use in the United States: 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Scope. (2017). Communication access. Retrieved from http://www.scopeaust.org.au/service/communication-access/

- Simon-Cereijido, G. (2017). Bilingualism, a human right in times of anxiety: Lessons from California. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 157–160. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1392610.

- Simons, G.F., & Fennig, C.D. (Eds.). (2017). Ethnologue: Languages of the world (20th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International. Retrieved from http://www.ethnologue.com

- Sprunt, B., & Marella, M. (2018). Measurement accuracy: Enabling human rights for Fijian students with speech difficulties. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 89–97. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1428685.

- The Right to Communicate. (n.d.). Human rights. Retrieved from http://righttocommunicate.com/?q=human_rights

- UNESCO. (2001). Universal declaration on cultural diversity. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001271/127160m.pdf

- UNESCO. (2005). Convention on the protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions. Retrieved from http://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/passeport-convention-2005-web2.pdf

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved from: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- United Nations. (1965). International convention on the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CERD.aspx

- United Nations. (1966a). International covenant on civil and political rights. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CCPR.aspx

- United Nations. (1966b). International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx

- United Nations. (1986). Declaration on the right to development. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/events/righttodevelopment/declaration.shtml

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/crc/

- United Nations. (2000). Millennium declaration. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- United Nations. (2007a). Declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. Retrieved from http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/IPeoples/Pages/Declaration.aspx

- United Nations. (2007b). Resolution 61/266 Multilingualism (A/RES/61/266). Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/61/266

- United Nations. (2015). Declaration on the rights of peasants and other people working in rural areas. Retrieved from https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G15/234/15/PDF/G1523415.pdf

- United Nations. (2016). Declaration on the right to peace. Retrieved from http://aedidh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/resolution-32-28.pdf

- United Nations. (2017a). International mother language day 21 February. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/events/motherlanguageday/index.shtml

- United Nations (2017b). International years. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/sections/observances/international-years/index.html

- van den Heuij, K.M.L., Neijenhuis, K., & Coene, M. (2017). Acoustic environments that support equally accessible oral higher education as a human right. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 108–114. doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1413136.

- Wang, C., Harrison, L.J., McLeod, S., Walker, S., & Spilt, J.L. (2017). Can teacher-child relationships support human rights to freedom of opinion and expression, education, and participation? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 133–141. doi:10.1080/17549507.2018.1408855.

- Wofford, M.C., & Tibi, S. (2017). A human right to literacy education: Implications for serving Syrian refugee children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 182–190. doi:10.1080/17549507.2017.1397746.

- World Bank Group. (2017). Population ages 0-14 (% of total). Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.0014.TO.ZS?end =2016&start =2016&view=map

- World Health Organization & The World Bank. (2011). World report on disability. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Yogyakarta Principles. (2016). The Yogyakarta principles. Retrieved from http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org